DOI: 10.31038/PSYJ.2024613

Abstract

Mental state understanding, or ‘ToM’ (ToM), appears essential for social-emotional wellbeing. Yet, most research on this relationship has relied on measures that tap only one aspect of ToM (e.g., false beliefs) using a method that has well-documented limitations. This research expands on earlier work by including a multi-faceted measure (the Children’s Social Understanding Scale; CSUS) to (a) test whether ToM as a whole predicts social-emotional functioning, and (b) examine which facets of social emotional functioning are best predicted by ToM. Across 2 studies (n=768 children aged 3 to 12) ToM as a global construct predicted multiple facets of children’s social-emotional functioning (measured by the Strengths and Difficulties Questionnaire in both studies and the Social Skills Improvement System in Study 2). These results provide a more comprehensive understanding of the relationships between children’s ToM and various aspects of social-emotional functioning and suggest that interventions aimed at fostering children’s ToM as a whole is a fruitful avenue for improving children’s social skills and minimizing their social-emotional difficulties.

Introduction

Overview and Rationale

Social perspective-taking or ‘Theory of Mind’ (hereafter referred to as ToM) refers to the ability, or abilities, involved in inferring and reasoning about the mental states of others, such as their knowledge, beliefs, intentions, desires, perceptions and emotions. ToM is argued to be critical for effective communication and social-emotional functioning (i.e., the processes through which children develop the capacity to understand, convey and manage their thoughts and emotions and develop meaningful relationships, more broadly referred to as social emotional health [1]. The importance of this ToM capacity has captivated researchers’ interest for decades. Yet, there are still major discrepancies in the literature on how to define and measure ToM. The majority of the research on ToM to date has continued to rely heavily on laboratory-based measures that tap only one aspect of ToM [2]. The most studied aspect of children’s ToM is their false belief understanding using a laboratory-based measure called the ‘classic false belief task’ [3] (also known as the Maxi task, change of location task, or Sally-Anne task). This task measures a child’s ability to understand that others can have beliefs that are different from reality. As of January 2024, the classic false belief task had been cited in the literature over 9,681 times and is still considered by many to be the litmus test or ‘gold standard’ for ToM understanding in children, for example [4,5]. Indeed, according to a recent review of the literature on children’s ToM from ages 0 to 5, the false belief task was used in the vast majority (approximately 75%) of the research [2]. Importantly, ToM is a comprehensive capacity that is much broader than simply reasoning about false beliefs. Mental state understanding encompasses a variety of mental states, including reasoning about knowledge states, desires, perceptions, emotions and intentions [6,7].

Laboratory-based research has examined the developmental trajectory of different facets of ToM through a variety of different measures. Indeed, Beaudoin and colleagues [2] identified 220 different measures to assess one or more aspects of a child’s ToM. Although these measures are useful in illustrating the developmental progression of ToM understanding, most are not wellsuited for capturing individual differences [6,8]. Early work suggested that individual differences in ToM are associated with a host of positive outcomes for children’s social and emotional functioning such as better interpersonal relationships and increased social competence [9-12]. Yet, given the reliance on measures that tap only one facet of ToM, it is an open question whether ToM, as a whole, is associated with children’s social-emotional functioning or whether those findings are specific to the particular aspect of ToM measured in any given study (most frequently the false belief task). Similarly, the previous work, which has largely focused on a single measure of ToM, tells us little about which aspect of ToM is most important for children’s social-emotional functioning. Like ToM, social-emotional functioning also encompasses many aspects. In the vast majority of earlier work different researchers have tended to focus on one particular facet of social-emotional functioning (e.g., prosocial behaviour or peer relationships) in relation to some measure of ToM. While this piecemeal approach has tremendous value in its own right, it does not identify which aspects of children’s social-emotional functioning are best predicted by their ToM. The overarching aim of the current research was to provide a more unified account of the relations between children’s ToM and their social-emotional functioning by using multifaceted measures. Specifically, to assess ToM globally we employ a comprehensive and ecologically valid measure of ToM – the Children’s Social Understanding Scale (CSUS [8]) that includes 6 different facets of mental states and encompasses both basic and complex mental state reasoning. We also employ two comprehensive and well-established measures of social-emotional functioning-the Strength and Difficulties Questionnaire (SDQ [13]) and the Social Skills Improvement System (SSIS [14]), which will give us a global measure of children’s social emotional functioning as well as a measure of 5 specific facets including Prosocial Behavior, Peer Relations, Emotional Functioning, Conduct Problems, and Hyperactivity/Impulsivity.

Background: Defining and Measuring ‘ToM’

Despite the fact that ToM had been intensely studied for over 40 years, see for example, [15] there are still many inconsistencies in the literature regarding what constitutes a ToM. Some researchers describe ToM as a single process or achievement-the recognition that the mind can misrepresent reality, which is often examined using a single paradigm assessing false belief understanding. Wimmer and Perner [3] developed what is now commonly referred to as the classic false belief task (also known as the Maxi task, change of location task or Sally-Anne task) to provide the first test of whether children had a ToM. This task measures a child’s ability to understand that others can have beliefs that are different from reality. In this task, children observe a scenario where a protagonist (e.g., Sally) hides an object in one location (e.g., basket) and then leaves the scene. Once Sally is gone, another character (e.g., Anne) hides the object in a different location (e.g., box). Children are then asked where Sally will look for the object when she returns. To pass, a child must indicate that Sally will look in the basket where she originally left it; this response would reveal a child’s understanding that the mind can misrepresent reality. Other variations of this task exist (e.g., the unexpected contents task, [16-18]). Across hundreds of experimental replications, 3-year-olds consistently fail, and it is not until around 4 or 5 years of age that children pass this task [3,16,19,20; see 21 for a meta-analysis]. However, several researchers have challenged the validity of the standard false belief tasks [22], proposed alternative explanations for the age-related changes observed between 3 and 5 years of age [23], and demonstrated that much younger children, perhaps even infants, can reason about false beliefs if the tasks are made easier by removing extraneous task demands [24].

Although the false belief test has been argued to be the best test of whether children have a concept that the mind represents the world, many researchers highlight that there is much more to ToM than reasoning about false beliefs. The mind is comprised of various mental states (e.g. goals, perceptions, knowledge, beliefs, intentions, and emotions). Throughout this manuscript when we use the term ToM, we are not referring to a singular capacity to reason about false beliefs, instead we are referring to a global construct comprised of a set of processes that involve inferring and reasoning about the mental states of others, including their desires, perceptions, knowledge, beliefs, intentions and emotions. Considerable developmental research has focused on assessing different aspects of ToM by designing a range of laboratory-based measures revealing that some aspects of ToM appear to develop quite early, while others develop quite late. For example, by 14-to 18-months of age infants show some early evidence of ToM in their ability to imitate others’ goals and intentions [25-28] and recognition of how desires are related to emotions [29]. By the age of 2 children can talk systematically about a small set of emotional states (e.g., happiness, sadness, anger, fear, surprise, disgust; [30]) and label emotional expressions [31,32]. By at least age 3, children understand that others differ in their knowledge states (e.g., [7,33-35]). And, as noted above, by age 4 or 5 children appear to understand that a person can hold a belief that is false or inconsistent with reality (e.g., [3,7,21]). Although false belief understanding is sometimes argued to be the last ‘major’ developmental milestone in a young child’s mental state understanding (i.e., at this point the child appears to have at least a basic understanding of intentions, preferences, desires, knowledge, beliefs, and emotions), ToM development does not stop at the age of 4 or 5 [9]. Rather, individuals continue to gain insight into the complexities of the mind throughout much of their life. Here, the foundational or conceptual basics of ToM are established fairly early in development but continue to grow in complexity [9,36,37]. For instance, despite the fact that children possess an understanding of emotion words by age 2, the ability to effectively infer, integrate and reason about the emotional states of others gets more complex with age (e.g., understanding mixed emotions, nostalgia). Complex ToM understanding is further exemplified by concepts such as sarcasm, humor, bluffing, double bluffing, misunderstanding and irony [36,37]. These types of non-literal situations are later developing skills that require a child to understand the unseen or hidden meaning of the message [38]. For instance, it is not until around 9 or 10 years of age that children begin to demonstrate an understanding of sarcasm and irony [39]; for additional examples of complex ToM tasks see [40-44].

Despite the wealth of evidence that ToM is a multi-faceted and complex concept that consists of much more than false belief understanding, the majority of the research on ToM and its relationship to social-emotional functioning, has continued to rely on false belief reasoning (for a review [2]). Furthermore, these measures were never intended to be used to measure individual differences, despite their widespread use as such, and are not well-suited for capturing individual differences (e.g. they are pass/fail). Another major limitation with the bulk of the previous literature relying on standard false belief tasks is that these measures unnecessarily involve overcoming a fundamental cognitive bias known as the ‘curse of knowledge’ bias, the tendency to be biased by one’s own knowledge when reasoning about a more naive perspective [33,45]. As such, the individual differences in children’s performance on this task may reflect more general cognitive abilities rather than, or in addition to, differences in ToM (for recent evidence [23,46], see also [6,47]).

Do Individual Differences in ToM Predict Social-Emotional Functioning?

Notwithstanding the aforementioned limitations in measuring ToM, a large body of research suggests that individual differences in ToM (or at least one or more aspects of it) predicts a range of outcomes for children’s social and emotional functioning with the bulk of the research focused on 5 key aspects of social emotional functioning, each reviewed below: Prosocial Behavior, Peer Relationships, Hyperactivity and Impulsivity, Conduct Problems, and Emotional Symptoms.

ToM and Prosocial Behavior

Individual differences in ToM have long been argued to predict both empathy and prosocial behaviour (e.g., [48,49]). The development of empathy is believed to be essential for social-emotional functioning because it enables one to understand others’ mental states, which helps to foster the development of prosocial (e.g., helping, sharing) behaviour. An abundance of the work on empathy and prosocial behaviour has relied heavily on standard false belief tasks. For example, researchers assessed 4-to 6-year-old children on measures of language ability, false belief understanding, emotion comprehension and prosocial orientation [50]. The results revealed that children’s language ability and false belief understanding significantly correlated with their emotion comprehension and prosocial orientation. These findings suggest that children’s ability to understand other people’s beliefs (specifically false beliefs) is related to their emotion comprehension skills (e.g., understanding the expression and cause of emotions) and inclination to act prosocially [50].

In another study, researchers assessed 4-year-olds’ ToM (using aggregated scores across seven tasks, including change in location false belief tasks, false beliefs tasks involving a nasty surprise or nice surprise and a deception game task) and found that more accurate ToM was associated with increased frequencies of cooperative planning, less conflict and increased communication with friends [51]. Performance across the ToM and deception game tasks was aggregated, making it unclear whether it is primarily false belief understanding that contributes to these social-emotional benefits or whether these findings apply to ToM more generally. Consistent with this, in another study researchers assessed the relationship between children’s prosocial behavior (based on teacher report and peer nominations) and children’s ToM (using an unexpected contents false belief task, change in location false belief task, second-order false belief task, belief-desire reasoning task and a mixed emotion understanding task). The results revealed that children with higher aggregate ToM scores tended to have greater prosocial behavior [52]. Although a mixed emotion understanding task was included as one of the 5 aggregated items it is again unclear whether it is false belief understanding specifically that predicts prosocial behaviour (or some third variable such as the curse of knowledge bias) or whether these findings indicate a relationship between one’s general ToM abilities and one’s tendency to engage in prosocial behavior.

Importantly, not all of the research on empathy and prosocial behaviour has relied so heavily on false belief understanding. As a notable exception, a meta-analysis of 76 studies [53] examining prosocial behavior in relation to affective ToM (using a hidden emotions task) and cognitive ToM (using deception, diverse desires, intention understanding and knowledge access tasks) found that children (ages 2-12) with higher composite ToM scores also had higher scores on measures of prosocial behaviour. As such, this meta-analysis provides compelling evidence that children with better ToM skills more generally are more likely to act prosocially. The current research aims to replicate this finding using alternative methods and extend this work by addressing whether ToM is a better predictor of prosocial behavior or other aspects of social-emotional functioning.

ToM and Peer Relationships

Not surprisingly given the links between ToM and prosocial behaviour, and prosocial behaviour and peer relationships, individual differences in ToM understanding has also been shown to predict individual differences in peer relationships. Again, a significant amount of this work has relied heavily on classic false beliefs tasks, in large part due to historical limitations in measurement options, nascent knowledge of the ToM construct, and ‘bandwagoning’, rather than due to researcher negligence. For example, a metaanalysis of 20 studies on children 2 to 10 years of age using standard first-and second-order false belief tasks and measures of peer popularity found that children with increased false belief understanding tend to be more well-liked [54]. Similarly, De Rosnay and colleagues [55] found that children’s false belief understanding was significantly related to their everyday use of mindful conversational skills in real-world social interactions with peers.

Although an overabundance of the research on ToM and peer relationships has utilized false belief tasks, some researchers have importantly used measures in addition to false belief understanding. For instance, Slomkowski and Dunn [56] looked at affective ToM in addition to false belief understanding at 40 months of age. Then, at 47 months of age these same children were examined on their connected communication with a friend. The results revealed that false belief understanding was significantly associated with more connected communication with peers, while affective ToM, although still significant, was less strongly related to connected communication [56]. Newer research has included tasks other than false belief tasks but created aggregated ToM scores (e.g., [57]), making it unclear how much of the relationship is driven by false belief reasoning versus ToM more generally.

ToM and Hyperactivity/Impulsivity

In a smaller body of literature, ToM understanding has also been shown to predict hyperactivity and impulsivity. Again, much of the work on hyperactivity and impulsivity has relied on false belief understanding. For example, research has shown that children with Attention Deficit Hyperactivity Disorder (i.e., ADHD) display impairments on first-and second-order false belief tasks (e.g., [58,59]. In other work with a nonclinical sample of 5-year-olds, researchers analyzed the relations among cognitive flexibility (using the dimension change card sort task), ToM (using aggregated scores across six tasks, including diverse desire, diverse belief, knowledge access, contents false belief, low verbal false belief and second-order false belief) and hyperactivity and inattention (using the SDQ). Those with higher aggregate ToM scores and scores of cognitive flexibility had lower levels of hyperactivity and inattention. The researchers suggested that children’s ToM understanding may mediate the adverse relationship between cognitive flexibility and hyperactivity and inattention early in development [60].

It is important to acknowledge that some research on hyperactivity and impulsivity has observed a connection between ToM and ADHD without including false belief tasks. For example, Maoz and colleagues [61] examined ToM in 10-year-old children with ADHD and healthy controls, using the social faux pas task and the self-reported Interpersonal Reactivity Index, revealing that children with ADHD demonstrated significantly lower levels of ToM compared with healthy controls. Consistently, research examining 7-to 11-year-old children with ADHD had difficulty in identifying others’ intentions and emotions (e.g., [62]). Similarly, research on ToM using emotion recognition tasks found that children with ADHD display deficits in recognizing certain facial expressions, such as anger and fear (e.g., [63-65]). It appears that at least some aspects of ToM are important predictors of hyperactivity and impulsivity. However, it remains unclear whether ToM as a whole predicts hyperactivity and impulsivity or only certain aspects of ToM.

ToM and Conduct Problems

Not surprisingly given the relationship between ToM and hyperactivity and impulsivity, ToM has also been shown to predict conduct problems (e.g., lying, cheating, aggression). Again, some work linking ToM with conduct problems has relied on false belief understanding. For example, one study revealed that 6-12-year-olds with conduct problems (but not their typically developing peers) tended to display deficits in false belief reasoning [66]. However, other work linking ToM to conduct problems suggests this link is not limited to false belief understanding. For instance, ToM was impaired in a sample of 9-11-year old children with conduct problems using the Reading the Mind in the Eyes Test, in which participants must identify cognitive and affective mental states from photos of the eye region of faces [67]. Similarly, in another study assessing executive function (i.e., inhibition, working memory, set shifting), affective ToM (using the ‘facial scale’ of the Cambridge Mindreading Face-Voice Battery), cognitive ToM (by assessing children’s reasoning about others’ beliefs and desires) and parent-reported conduct problems (using the Child Behaviour Checklist) in 9-to 13-year-olds found a small negative correlation between ToM, specifically in affective aspects, and conduct problems [68]. In contrast, researchers examining the longitudinal relation between executive function (i.e., flexibility, working memory, inhibition), ToM (using a cartoon task with both cognitive and affective stories) and parent-reported conduct problems (using the SDQ) in children ages 6 to 11 found that higher executive function and both cognitive and affective ToM abilities predicted less conduct problems 1 year later [69]. Again, it appears that at least some aspects of ToM are important predictors of conduct problems; however, it remains unclear whether ToM as a whole predicts conduct problems or whether specific aspects are better predictors.

ToM and Emotional Symptoms

Finally, ToM understanding also predicts emotional symptoms such as sadness and depression, at least in adults. A meta-analysis of 18 studies examining the relationship between ToM and Major Depressive Disorder (i.e., MDD) in adults revealed that deficits in ToM can be a risk factor for depression and accompanying psychosocial impairment, with the level of ToM impairment predicting the severity of the depressive symptoms [70,71]. Whether deficits in ToM as a global construct are the risk factor for depression or whether some aspects of ToM play a greater role remains unclear as the metaanalyses collapsed across various ToM measures, including various false belief tasks. Intriguingly, other research linking ToM to emotional symptoms, using novel variants of the standard false belief task, have found that adults with chronic depression showed difficulties with false belief tasks concerning emotion states but not ones involving visual-spatial representations [72]. Whereas research assessing ToM in adolescents with MDD and healthy controls found that those with MDD were able to solve a basic false belief task (e.g., unexpected contents false belief task), but had difficulty with more complex ToM (e.g., second-order false belief, the reading the mind in the eyes test, or the hinting or sarcasm tasks) compared to healthy controls [73]. This research highlights that in addition to investigating a global deficit in ToM versus a specific deficit in one type of ToM (e.g., false belief reasoning) it may be fruitful to assess individual differences in complex vs basic ToM. Unfortunately, literature examining ToM in young children with emotional symptoms is quite scarce but provides impetus for further research in this area. For instance, research following a natural disaster (i.e., the 2012 earthquake in Italy) suggests that better false belief understanding can act as a protective factor against Post-Traumatic Stress Disorder (i.e., PTSD; [74]). Finally, a promising inaugural study on the relationship between emotional symptoms and ToM (using the Strange Stories task assessing various complex mental states), revealed that children with higher ToM scores experienced fewer depressive symptoms and fewer symptoms of panic disorder and separation anxiety [75].

Motivation for the Current Research

Overall, the research reviewed above illustrates that there is little consistency in how ToM is measured in any given study (with the exception of the use of false belief tasks that historically dominated the field). As a result, it is unclear whether ToM, as a whole, is associated with children’s social-emotional functioning, or whether one or more aspect of ToM might be better predictors of social-emotional functioning. In juxtaposition, the literature showing ToM predicting social-emotional functioning is predominately piecemeal (i.e., examining only one social-emotional outcome such as peer relations or emotional symptoms or hyperactivity in a given study), making it impossible to compare the strength of the social-emotional correlates of ToM with one another. In other words, which aspects of children’s social-emotional functioning are best predicted by their ToM? A critical focus of the current research is to fill these aforementioned gaps: To better understand the nature and strength of the relationships between children’s ToM using multi-faceted global measure of ToM, and social-emotional functioning including measures of 5 key domains: emotional symptoms, conduct problems, hyperactivity and impulsivity, peer relationship problems and prosocial behaviours. This research approach also aims to provide the critical groundwork needed to establish whether it is false belief reasoning, or theory of mind as a whole, that should be targeted in prevention and intervention approaches to improve children’s social emotional. To measure ToM we chose the Children’s Social Understanding Scale (CSUS; [8], which provides: (a) a parent-report measure of individual differences in ToM, that is (b) ecologically valid because it captures everyday behaviour over long periods of time, (c) allows for greater variability (versus pass/fail measures), (d) provides excellent test-retest reliability and internal consistency (Cronbach’s alpha=0.89; [76]), and (e) importantly encompasses the multi-faceted nature of ToM (i.e., including items assessing 6 different facets of belief, knowledge, perception, desire, intention and emotion understanding and encompassing both basic and complex ToM understanding). Parent-report measures are incredibly informative as most young children spend the majority of their time with their parents who are able to observe their behaviour across different contexts over an extended period of time. As a result, parents are uniquely situated to assess their child’s ToM, and may do so better than laboratory-based measures of ToM alone [8].

We also chose a comprehensive, and well-established parent-report measure of socialemotional functioning: the Strengths and Difficulties Questionnaire (SDQ; [13]). The SDQ displays good test-retest reliability (Cronbach’s alpha=0.62) and internal consistency (Cronbach’s alpha=0.73; [77]) and, in addition to providing a composite score of children’s social-emotional difficulties, importantly distinguishes between five different aspects of socialemotional functioning: emotional symptoms, conduct problems, hyperactivity and impulsivity, peer relationship problems and prosocial behaviours. Study 1 examined whether ToM, as a global construct, predicts different aspects of children’s social-emotional functioning, and if so, which of the five facets of social-emotional functioning are best predicted by ToM. We hypothesized that global ToM abilities would reliably predict children’s overall social-emotional functioning as well as each individual facet. Specifically, we predicted that children’s global ToM would positively predict prosocial behaviour, and negatively predict the peer relationship problems, hyperactivity and impulsivity, conduct problems and emotional symptoms. Given the piecemeal nature of the extant literature, we did not make specific predictions about the magnitude of the relationships between ToM and the five facets of social-emotional functioning. Study 2 replicated and extended this work in a younger sample.

Method: Study 1

Participants

Our sample consisted of 376 parents of children ranging in age between 3 and 12 years (M=6;3, SD=2;0, range: 3;0-12;7) with 49.5% males (n=186). Eighty-eight percent (n=309) of the children in our sample were born in Canada. Of the 41.8% of parents who provided information on their child’s ethnicity, 67.5% indicated Caucasian, 20.4% indicated Asian, and 12.1% indicated another option or mixed. Participants were recruited through preschool programs, schools and childcare facilities, and a large database of families who expressed interest in participating in research. The majority of participants completed paper and pencil versions of the survey in person while their child participated in another research project. Parents of children recruited through preschools and schools had the option to complete the survey online. The majority of participants were the mothers who were the primary caregivers. Sample size was not predetermined but rather parent data was collected until the research projects their children were participating in were complete. To be included in the sample, parents needed to complete a minimum of 80% of the items for each measure. For included participants, missing data were handled according to the procedures outlined by Tahiroglu and colleagues [8] and Goodman [13].

Materials and Procedure

Parents were administered the Strength and Difficulties Questionnaire (SDQ; [13]) and the Children’s Social Understanding Scale (CSUS; [8]), as well as some demographic questions (e.g. ethnicity, sex). The SDQ consists of 25-items focused on five different components of social-emotional health: emotional symptoms (e.g., often unhappy, depressed, or tearful), conduct problems (e.g., generally well behaved, usually does what adults request; reverse coded), hyperactivity and impulsivity (e.g., constantly fidgeting or squirming), peer relationship problems (e.g., rather solitary, prefers to play alone), and prosocial behavior (e.g., considerate of other people’s feelings). Parents rated their child’s behavior over the previous 6 months on each item with answers ‘Not True’ (0), ‘Somewhat True’ (1) and ‘Certainly True’ (2). The prosocial behaviors comprise the Strengths subscale, whereas the other four components—emotional symptoms, conduct problems, hyperactivity and impulsivity and peer relationship problems—comprise the Difficulties subscale.

The CSUS is a parent-report measure of children’s ToM, their understanding of mental states, including beliefs, desires, emotions, intentions, perceptions and knowledge. The CSUS consists of 18-items rated on a 4-point scale, including ‘Definitely Untrue’ (1), ‘Somewhat Untrue’ (2), ‘Somewhat True’ (3) and ‘Definitely True’ (4). Items include: “My child talks about differences in what people like or want (e.g., “you like coffee but I like juice”)”, “My child has trouble figuring out whether you are being serious or just joking” (reverse coded), and “My child talks about the difference between the way things look and how they really are (e.g., “It looks like a snake but it’s really a lizard”). See Appendix A for a full list of items. In the initial CSUS work, Tahiroglu and colleagues [8] sought to broaden the repertoire of measures available for assessing developmental differences in ToM. In Study 1, the authors demonstrated that they were able to create a psychometrically sound measure of ToM based on parent-reports. The CSUS scale displayed excellent internal consistency (i.e., Cronbach’s alpha=0.89), test-retest reliability (r=0.88, p<0.001), and convergent validity with children’s performance on laboratory-based ToM tasks (e.g., contents false-belief tasks, knowledge-access tasks, level two perspective-taking tasks). In Study 2, Tahiroglu and colleagues [8] further validated the CSUS by collecting data from a new sample of children and parents with a different set of ToM tasks. Again, the results revealed high internal consistency and revealed that parents’ ratings significantly correlated with children’s ToM performance even after controlling for age. In Study 3, Tahiroglu and colleagues [8] collected data with a slightly older sample of children using a more sophisticated ToM measure (i.e., restricted view task), while controlling for several other cognitive abilities (i.e., prospective memory, working memory, planning). The results of Study 3 provide evidence for construct validity by demonstrating a relation between parent-reported ToM via the CSUS and children’s ToM performance even when other cognitive abilities were held constant.

Results and Discussion

Analysis of the SDQ

Parents’ responses on the SDQ were coded using the scoring system outlined by the measure’s creators [13]. Scores were summed to determine the Strengths (M=8.31, SD=1.73, max score=10) and Difficulties scores (M=8.67, SD=5.06, max score=40). The internal consistency of the Strengths (Cronbach’s alpha=0.73) and Difficulties (Cronbach’s alpha=0.76) subscales were good. The reliability of the Difficulties subscales in our sample was also acceptable given that each subscale is comprised of only 5-items: emotional symptoms (Cronbach’s alpha=0.61), conduct problems (Cronbach’s alpha=0.56), hyperactivity and impulsivity (Cronbach’s alpha=0.78) and peer relationship problems (Cronbach’s alpha=0.57). See Table 1 for Subscale Means and SDs.

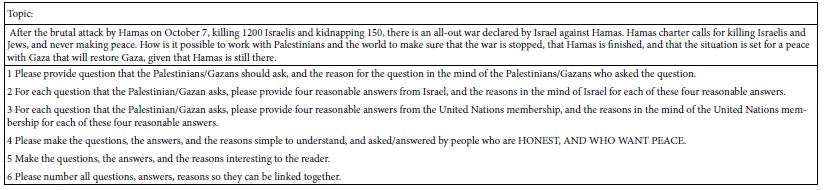

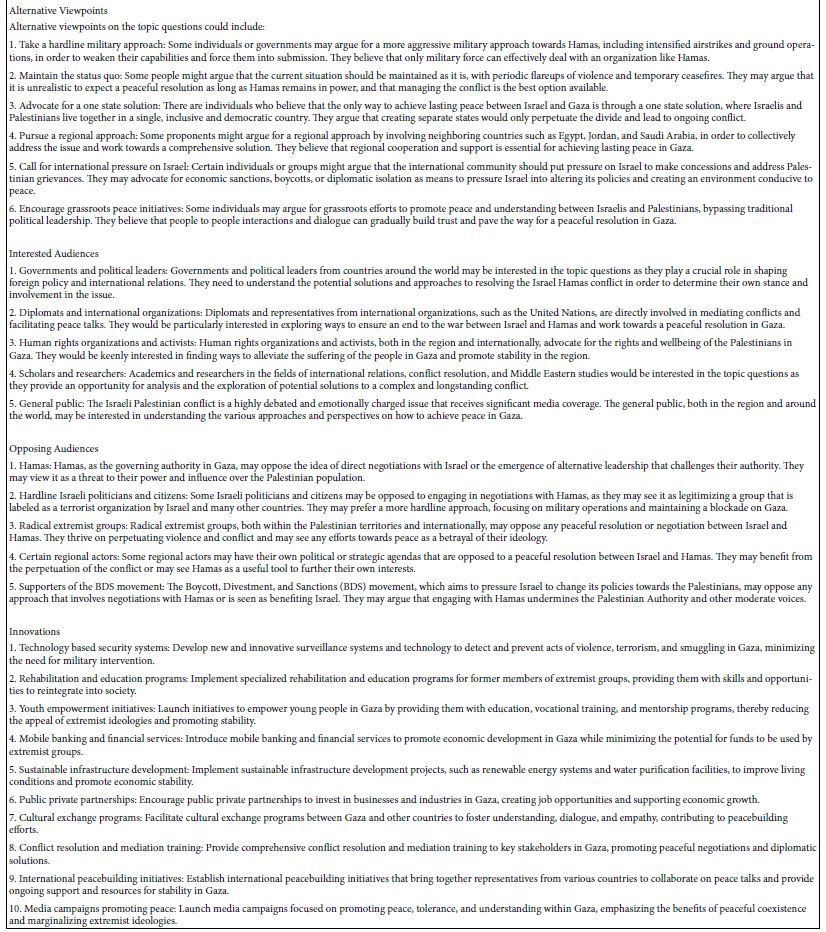

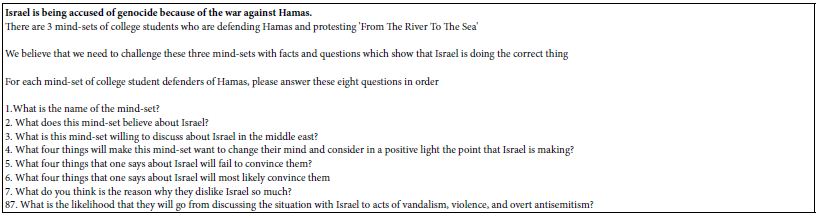

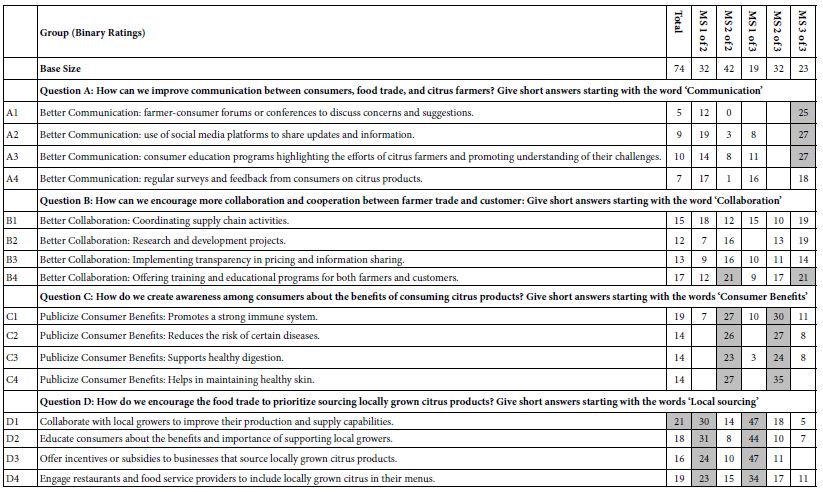

Table 1: Study 1: Means and Standard Deviations of the SDQ subscales

|

Mean(Max=10)

|

SD

|

| Emotional Symptoms |

1.78

|

1.76 |

|

Conduct Problems

|

1.54 |

1.49

|

| Hyperactivity and Impulsivity |

3.72

|

2.52 |

|

Peer Relationship Problems

|

1.47 |

1.77

|

| Prosocial Behaviour |

8.31

|

1.73

|

A 2 (sex: female, male) x 2 (subscale: Difficulties, Strengths) ANOVA indicated a significant effect of child’s sex on SDQ scores, F(2, 373)=8.11, p<0.001. That is, significant differences emerged between females and males on both the Difficulties, F(1, 374)=5.95, p=0.015, and Strengths subscales, F(1, 374)=14.65, p<0.001. Specifically, females scored lower than males on the Difficulties subscale (females: M=8.09, SD=4.80; males: M=9.32, SD=5.01) and higher than males on the Strengths subscale (females: M=8.57, SD=1.66; males: M=7.88, SD=1.81). There were no differences in SDQ scores based on nationality (i.e., born in Canada or not) or by ethnicity, thus these variables were excluded from subsequent analyses. Next, we tested whether age predicted SDQ scores. After accounting for the significant effects of sex, age did not significantly predict scores on the Difficulties portion of the SDQ, t=-.018, p=0.99; however, age significantly predicted scores on the Strengths portion of the SDQ, ΔR2=0.015, β=0.133, t=2.65, p=0.008. That is, children’s prosocial behaviour increased with age, whereas their social-emotional difficulties remained stable across age.

Analysis of the CSUS

Parents’ responses on the CSUS were coded using the scoring system outlined by the measure’s creators [8]. Scores were averaged to determine the CSUS score (M=3.32, SD=0.37, max score=4). The internal consistency of the scale in the current sample was excellent (Cronbach’s alpha=0.83) and consistent with the validation of the CSUS. There were no differences in CSUS scores based on sex, nationality (i.e., born in Canada) orethnicity. Next, we tested whether age predicted CSUS scores and found that age positively predicted CSUS scores, ΔR2=0.097, β=0.31, t=6.41, p<0.001, consistent with earlier findings [8].

Predictive effects of CSUS on SDQ

Of particular interest in this study was whether children’s ToM relates to their social-emotional functioning. The CSUS positively predicted the Strengths subscale of the SDQ, r(376)=0.30, p<0.001 and negatively predicted the Difficulties subscale of the SDQ, r(376)=-.21, p<0.001. Even after controlling for the effects of sex and age, the CSUS positively predicted the Strengths subscale of the SDQ, ΔR2=0.07, β=0.28, t=5.48, p<0.001 and negatively predicted the Difficulties subscale of the SDQ, ΔR2=0.05, β=0.-23, t=-4.30, p<0.001. In other words, an increased understanding of mental states predicts a twofold pattern in social-emotional functioning; children with a greater understanding of mental states demonstrate increased social-emotional strengths, in terms of more prosocial behaviors, and fewer social-emotional difficulties.

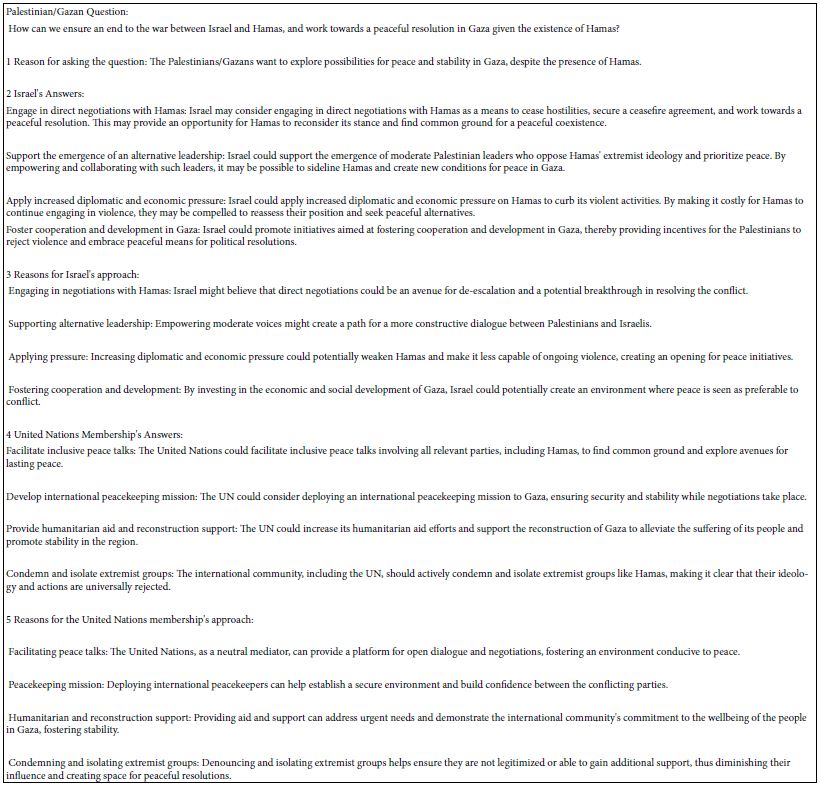

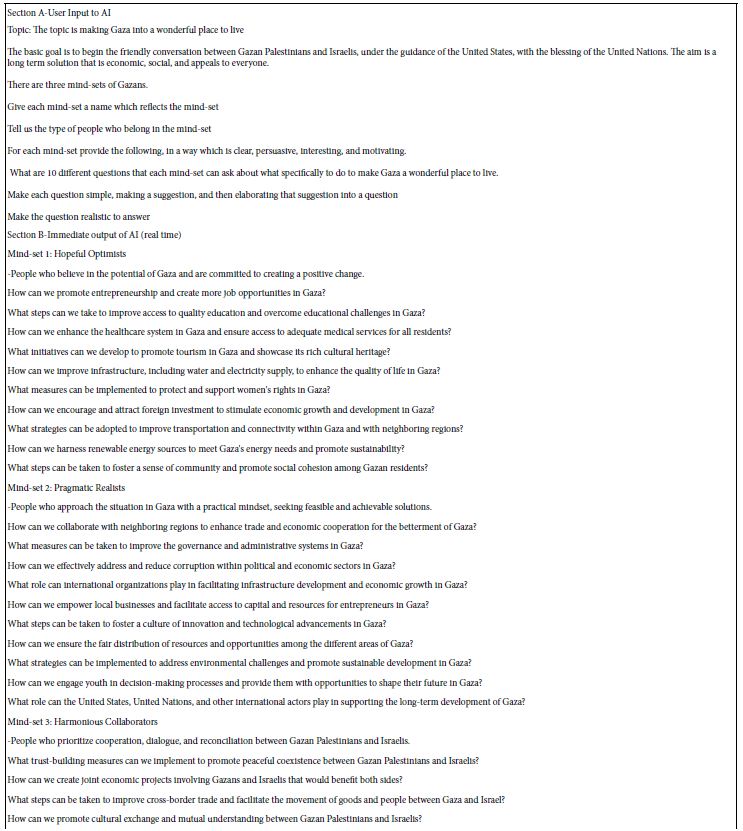

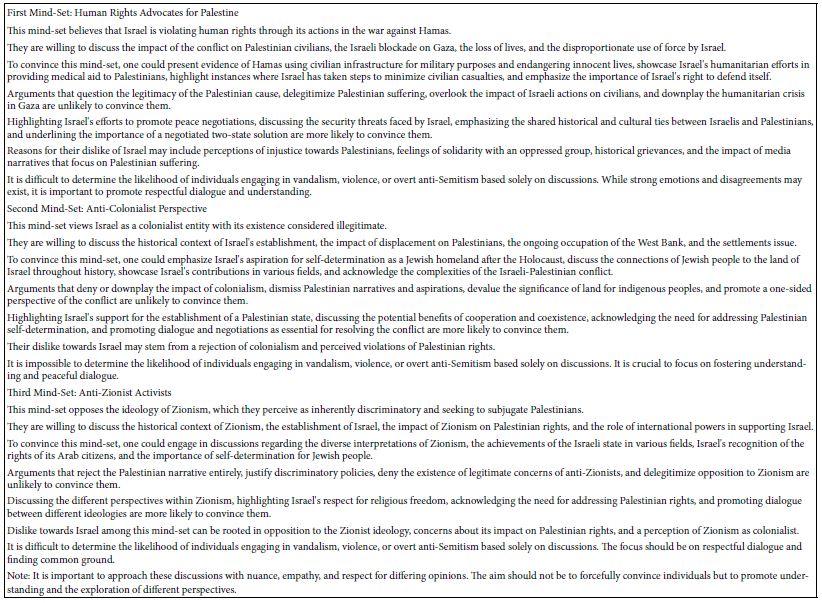

To determine precisely which social-emotional difficulties decrease with increased mental state understanding, we examined the predictive effects of the CSUS on the four Difficulties subscales of the SDQ. As seen in Table 2, even after controlling for the effects of sex and age, both the conduct problems subscale and the hyperactivity and impulsivity subscale were negatively correlated with children’s mental state understanding. A small negative correlation (r=-.09, p=0.056, one-tailed) was also observed between peer relationship problems and ToM.

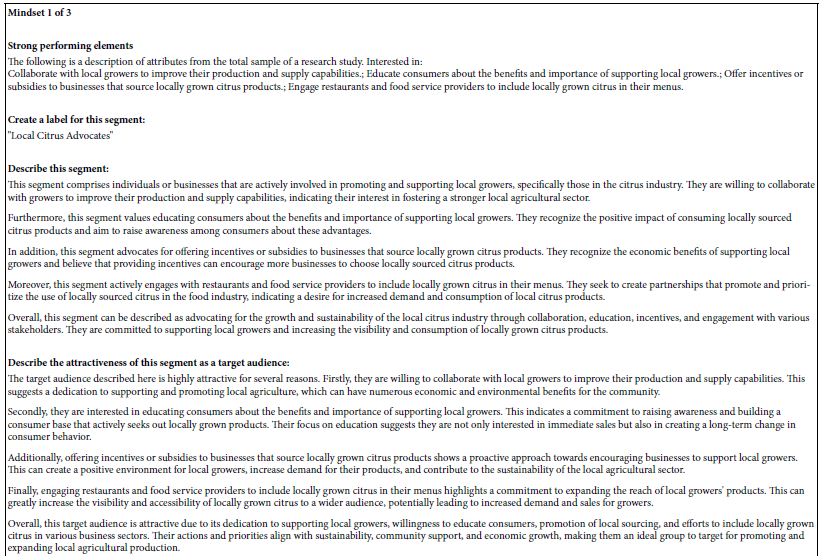

Table 2: Study 1: Partial Correlations controlling for the child’s sex and age: CSUS scores independently predict conduct problems and hyperactivity and impulsivity of the SDQ Difficulties subscales.

|

Emotional Symptoms

|

Conduct Problems |

Hyperactivity and Impulsivity |

Peer Relationship Problems |

|

Emotional Symptoms

|

– |

– |

– |

–

|

| Conduct Problems |

r=0.19

p<0.001

|

– |

– |

–

|

| Hyperactivity and Impulsivity |

r=0.18

p<0.001

|

r=0.43

p<0.001 |

– |

– |

|

Peer Relationship Problems

|

r=0.27

p<0.001 |

r=0.20

p<0.001 |

r=0.08

p=0.142 |

–

|

| CSUS |

r=0.02

p=0.755

|

r=-.19

p<0.001 |

r=-.24

p<0.001 |

r=-.09

p=0.102

|

The critical questions of Study 1 were: (1) whether ToM as a global construct predicts children’s social-emotional functioning, and (2) which of the five facets of social-emotional functioning are best predicted by ToM. As hypothesized, we found that even when controlling for the effects of sex and age, the CSUS was positively predictive of children’s social-emotional strengths (i.e., prosocial behaviour) and negatively predictive of social-emotional difficulties. In terms of the five facets of children’s social-emotional functioning the largest relationship was observed between children’s prosocial behaviour and ToM. In terms of children’s socialemotional difficulties, the largest effects were observed in hyperactivity and impulsivity, followed by conduct problems. A small negative relationship was also observed with peer relationship problems. The current research importantly expands upon our understanding of the critical relationship between children’s ToM and their social-emotional functioning by utilizing multifaceted measures that provide a more comprehensive and ecologically valid picture of children’s functioning. Importantly, this research expands upon earlier work by revealing that children’s ToM as a whole (i.e., their understanding of desire, perception, knowledge, belief, intention and emotion), not just performance on false belief tasks, predicts their social-emotional functioning.

One goal of Study 2 was to determine whether the results of Study 1 would replicate in another community sample with children of a narrower age-range (e.g., Study 1=3-to 12-yearolds; mean age=6;3 versus Study 2=3-to 7-year-olds; mean age=4;6). The CSUS was originally designed to tap social understanding in younger age ranges (i.e., 3-6 years), at a time where the most developmental change occurs in ToM [8]. Out of convenience, Study 1 included participants through age 12. We observed individual differences in performance on the CSUS, even in these older ages; however, we wanted to ensure these results would replicate in a similarly-sized sample with a younger mean age. A second objective of Study 2 was to examine the relation between children’s ToM and an even broader range of children’s social-emotional skills. To that end, we added the Social Skills Improvement System (SSIS; [14]), which has seven different subscales that capture additional aspects of children’s social-emotional skills (i.e., communication, cooperation, assertion, responsibility, engagement, empathy, and self-control). Again, our primary research question was whether ToM as a whole predicts children’s social-emotional functioning and if so, which aspects of their social emotional functioning are most strongly predicted by ToM. We hypothesized that, consistent with the results of Study 1, ToM would reliably predict young children’s overall social-emotional functioning as measured by the SDQ, as well as the broader range of social-emotional skills measured by the addition of the SSIS.

Method: Study 2

Participants

Our sample consisted of 392 parents of children ranging in age from 3 to 7 years (M=4;6, SD=1;2, range: 3;0-7;9) with 47.7% female (n=187). Of the 92.3% of parents who provided information on where their child was born, 89.8% (n=352) indicated Canada. Of the 89.5% of parents who provided information on their child’s ethnicity, 44.6% indicated Caucasian, 13.0% indicated Asian, and 31.9% indicated another option or mixed. Participants were recruited through the same means as Study 1. Missing data were handled the same way as in Study 1. A subset of parents of children (n=88; 56% female) ranging in age from 3 to 7 years (M=4;4, SD=1.1; range: 3;0-7;4) completed the SSIS at the end of the survey. To be included in the analyses on the SSIS, a parent needed to complete a minimum of 80% of the items. For included participants, missing data were handled according to the procedures outlined by the measures’ authors (i.e., [14]).

Materials and Procedure

The procedure and measures for the SDQ and CSUS were identical to Study 1. Parents were also administered the Social Skills Improvement System (SSIS; [14]). The SSIS consists of 46-items focused on seven different subscales to better capture different aspects of children’s social-emotional skills, beyond the simple 5-item prosocial subscale of the SDQ used in Study 1, including: communication (e.g., speaks in appropriate tone of voice), cooperation (e.g., follows classroom rules), assertion (e.g., asks for help from adults), responsibility (e.g., takes responsibility for part of a group activity), engagement (e.g., participates in games or group activities), empathy (e.g., shows concern for others), and self-control (e.g., uses appropriate language when upset). Parents rated their child’s behaviour using a 4-point scale on each item with answers ‘Never’ (0), ‘Seldom’ (1), ‘Often’ (2) and ‘Almost Always’ (3).

Results and Discussion

Analysis of the SDQ

Responses on the SDQ were coded using the scoring system outlined by the measure’s creators [13]. Scores were summed to determine the Strengths (M=7.95, SD=1.85, max score=10) and Difficulties scores (M=8.12, SD=4.65, max score=40). The internal consistency of the Strengths (Cronbach’s alpha=0.73) and Difficulties (Cronbach’s alpha=0.76) subscales were good and consistent with Study 1. The internal consistencies of the Difficulties subscales were also acceptable for the 5-item subscales: emotional symptoms (Cronbach’s alpha=0.63), conduct problems (Cronbach’s alpha=0.64), hyperactivity and impulsivity (Cronbach’s alpha=0.79) and peer relationship problems (Cronbach’s alpha=0.56). See Table 3 for subscale Means and SDs.

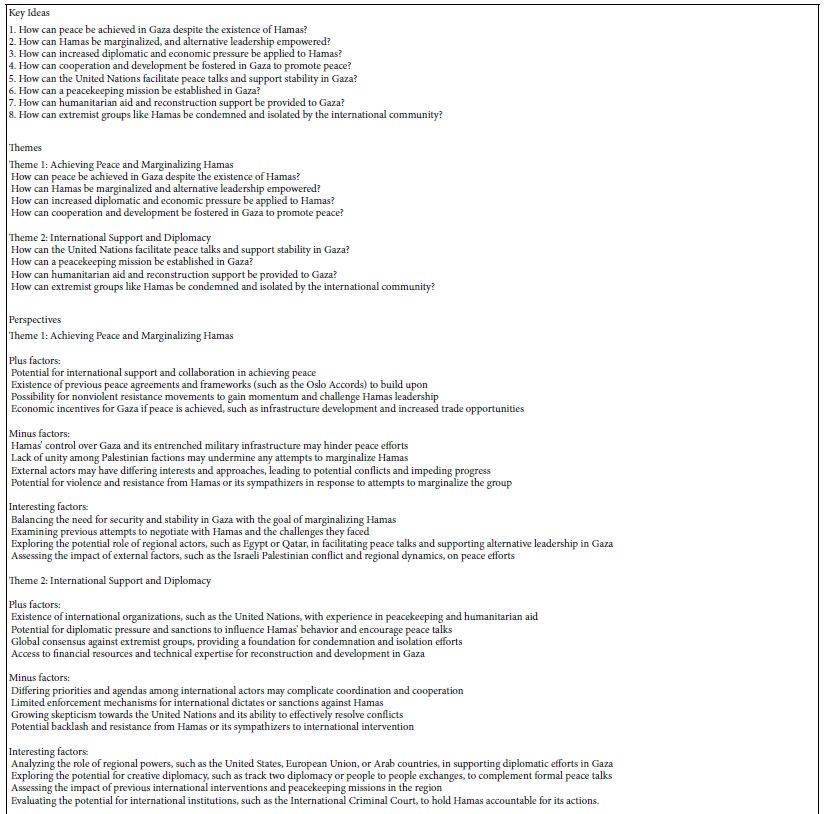

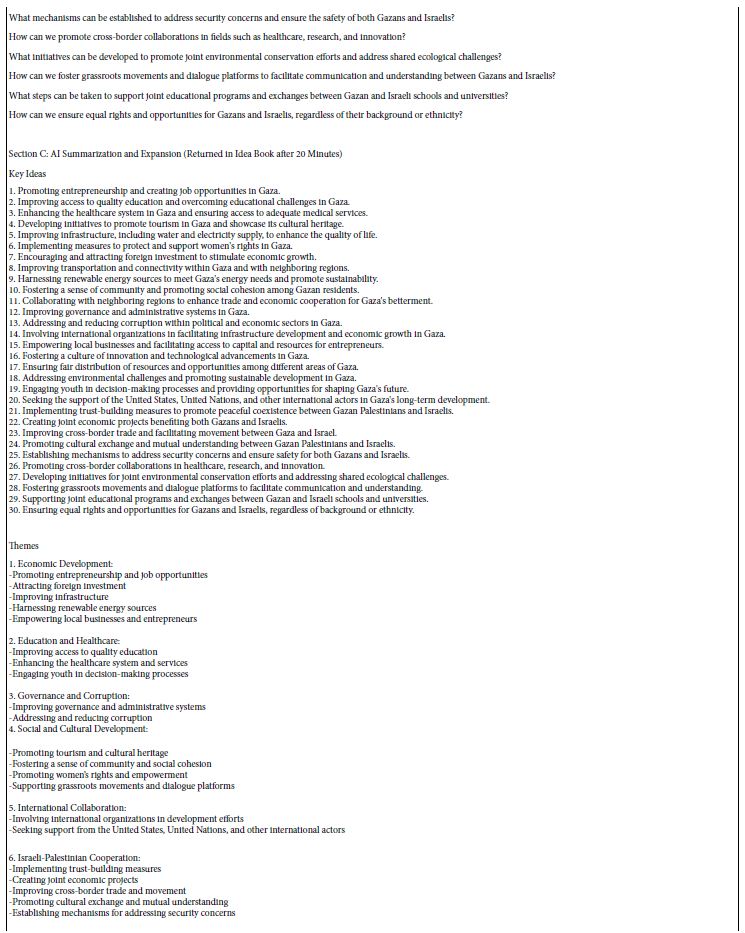

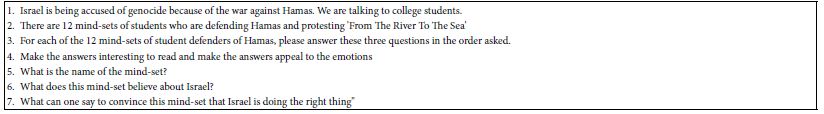

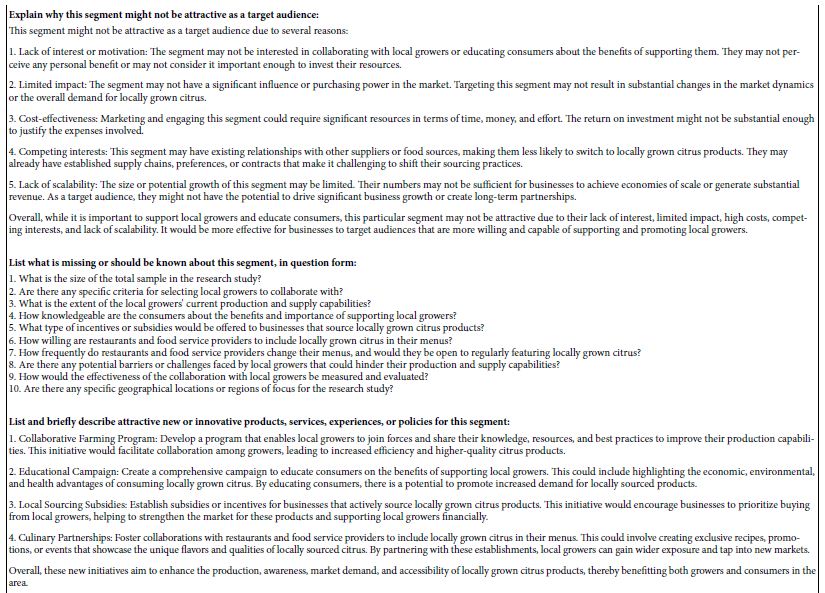

Table 3: Study 2: Means and Standard Deviations of the SDQ subscales

|

Mean(Max=10)

|

SD |

|

Emotional Symptoms

|

1.62 |

1.73

|

| Conduct Problems |

1.41

|

1.47 |

|

Hyperactivity and Impulsivity

|

3.62 |

2.41

|

| Peer Relationship Problems |

1.47

|

1.58 |

|

Prosocial Behaviour

|

7.95 |

1.85

|

A 2 (sex: female, male) x 2 (subscale: Difficulties, Strengths) ANOVA indicated a marginally significant effect of the child’s sex on SDQ scores, F(2, 289)=2.86, p=0.058. That is, marginally significant differences emerged between females and males on the Strengths subscale, F(1, 390)=5.62, p=0.018, but not on the Difficulties subscale, F(1, 390)=1.34, p=0.249. Specifically, females scored higher than males on the Strengths subscale (females: M=8.18, SD=1.86; males: M=7.74, SD=1.81) and similar to males on the Difficulties subscale (females: M=7.84, SD=4.45; males: M=8.38, SD=4.82). Consistent with Study 1, there were no differences in SDQ scores based on nationality or by ethnicity (all ps > .10), thus these variables were excluded from subsequent analyses. As in Study 1, age did not significantly predict the Difficulties portion of the SDQ, t=-.41, p=0.682, but predicted scores on the Strengths portion of the SDQ, ΔR2=0.03, β=0.13, t=2.55, p=0.011. That is, children’s prosocial behaviour tended to increase with age, whereas their social-emotional difficulties remained relatively stable across age.

Analysis of the CSUS

Responses on the CSUS were coded using the scoring system outlined by the measure’s creators [8]. Scores were averaged to determine the CSUS score (M=3.25, SD=0.41, max=4). The internal consistency of the scale was excellent (Cronbach’s alpha=0.84) consistent with the validation of the CSUS. Consistent with Study 1, there were no differences in CSUS scores based on sex, nationality, or ethnicity, all ps > .10. Age positively predicted CSUS scores, ΔR2=0.18, β=0.42, t=9.28, p<0.001, consistent with Study 1 and earlier work [8].

Predictive effects of CSUS on SDQ

A central hypothesis of this research was that children’s ToM as a broad multi-faceted construct would predict their social-emotional functioning. Indeed, even after controlling for the effects of sex and age, the CSUS positively predicted the Strengths subscale of the SDQ, ΔR2=0.17, β=0.41, t=7.97, p<0.001 and negatively predicted the Difficulties subscale of the SDQ, ΔR2=0.16, β=-.44, t=-8.44, p<0.001. In other words, as in Study 1, an increased understanding of mental states predicted a two-fold pattern in social-emotional functioning: Children with a greater understanding of mental states exhibit significantly greater social-emotional strengths, in the form of prosocial behaviours such as helping and sharing, and simultaneously significantly fewer social-emotional difficulties.

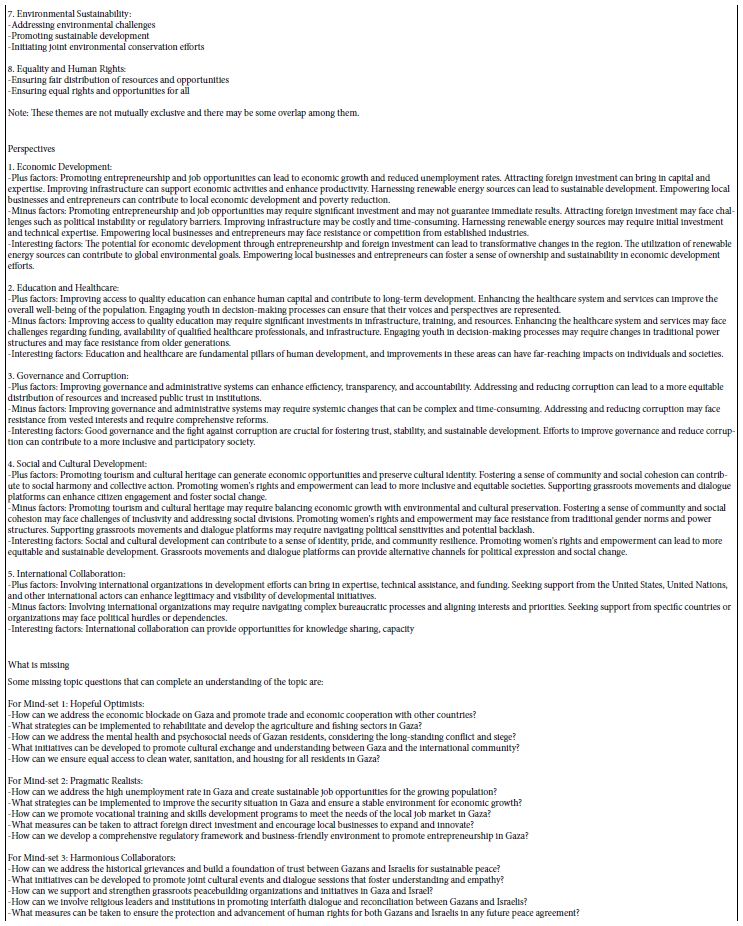

Predictive effects of CSUS on SDQ Difficulties subscales

To determine which social emotional difficulties decrease with increased ToM, we examined the predictive effects of the CSUS on the four Difficulties subscales of the SDQ. As seen in Table 4, even after controlling for the effects of sex and age, all aspects of social emotional difficulties negatively correlated with children’s ToM (all ps<0.001). That is, poorer mental state understanding as measured by the CSUS uniquely, individually, predicted children’s conduct problems, peer relationship problems, hyperactivity and impulsivity, and emotional symptoms.

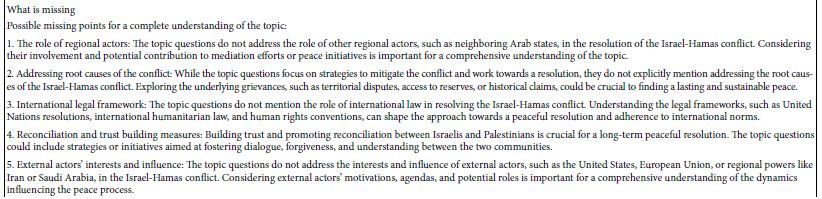

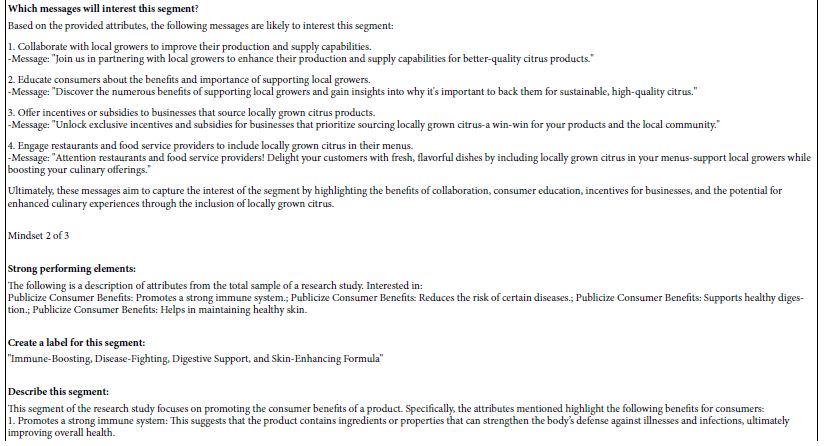

Table 4: Study 2: Partial Correlations controlling for the child’s sex and age: CSUS scores independently predict each of the SDQ Difficulties subscales.

|

Emotional Symptoms

|

Conduct Problems |

Hyperactivity and Impulsivity |

Peer Relationship

Problems |

|

Emotional Symptoms

|

– |

– |

– |

–

|

| Conduct Problems |

r=0.21

p<0.001

|

– |

– |

– |

|

Hyperactivity and Impulsivity

|

r=0.10

p=0.049 |

r=0.44

p<0.001 |

– |

–

|

| Peer Relationship Problems |

r=0.32

p<0.001

|

r=0.22

p<0.001 |

r=0.05

p=0.303 |

– |

|

CSUS

|

r=-.16

p=0.001 |

r=-.36

p<0.001 |

r=-.30

p<0.001 |

r=-.20

p<0.001

|

The results of the analyses examining which facets of children’s social-emotional difficulties are uniquely predicted by mental state understanding were similar but notably not identical across the two studies. In Study 1, the relationship between the CSUS and peer relationships was very small and only trended toward significance, and the CSUS and emotional symptoms were not significantly correlated. In contrast, in Study 2 all aspects of children’s difficulties were negatively correlated with ToM, although the smallest relationship was observed in emotional symptoms, suggesting it is the least related to ToM of the facets of socialemotional health included here. An examination of the means and standard deviations of the SDQ subscales (refer to Tables 1 and 3) reveals remarkable similarities, except the subscale means are somewhat greater in Study 1; reflecting greater difficulties in the older sample. One possible explanation of the mixed results for emotional symptoms is that the variability in the emotional symptoms for the older children may be more heavily influenced by factors other than ToM (e.g., stress at school, biological changes). Overall, the results of these two large sample studies reveal highly consistent results demonstrating that children’s mental state understanding positively predicts children’s social-emotional strengths and negatively predicts their socialemotional difficulties. The largest effects were observed in conduct problems and hyperactivity and impulsivity, suggesting that interventions aimed at fostering ToM may prove especially beneficial for these types of social emotional challenges.

Analysis of the SSIS

Responses on the SSIS were coded using the scoring system outlined by the measure’s creators [14]. Scores were summed to determine the SSIS score (M=94.72, SD=15.34, max=138). The internal consistency of the scale was excellent (Cronbach’s alpha=0.94). The internal consistencies of the SSIS subscales were also generally adequate: Cooperation (Cronbach’s alpha=0.84), Self-Control (Cronbach’s alpha=0.80), Empathy (Cronbach’s alpha=0.79), Engagement (Cronbach’s alpha=0.71), Responsibility (Cronbach’s alpha=0.70), Assertion (Cronbach’s alpha=0.67) and Communication (Cronbach’s alpha=0.40). There were no significant differences in SSIS scores based on nationality or ethnicity, all ps > .10. Significant differences were revealed between females and males on the SSIS, F(1,86)=9.11, p=0.003, with females scoring higher than males (M=98.94, SD=14.48; M=89.44, SD=14.91, respectively). Age did not significantly predict scores on the SSIS, t=1.27, p=0.208.

Predictive effects of the CSUS on SSIS

After controlling for sex and age, the CSUS positively predicted scores on the SSIS, ΔR2=0.36, β=0.59, t=5.62, p<0.001 (see Table 5 for the partial correlations for the CSUS scores and the SSIS subscales).

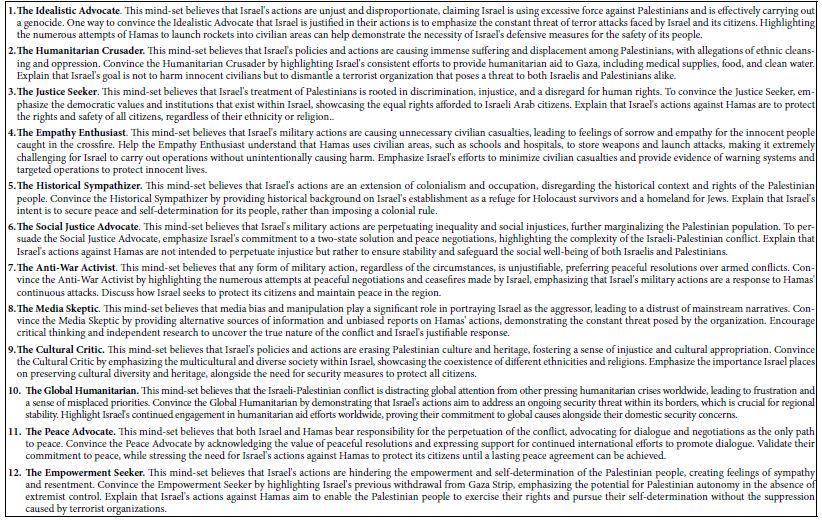

Table 5: Study 2: Partial Correlations controlling for the child’s sex and age: CSUS scores independently predict each of the SSIS subscales.

|

SISS Subscale

|

(1) |

(2) |

(3) |

(4) |

(5) |

(6) |

(7)

|

| (1) Communication |

–

|

– |

– |

– |

– |

– |

– |

|

(2) Cooperation

|

r=0.59

p<0.001 |

– |

– |

– |

– |

– |

–

|

| (3) Assertion |

r=0.60

p<0.001

|

r=0.62

p<0.001 |

– |

– |

– |

– |

– |

|

(4) Responsibility

|

r=0.40

p<0.001 |

r=0.56

p<0.001 |

r=0.56

p<0.001 |

– |

– |

– |

–

|

| (5) Engagement |

r=0.49

p<0.001

|

r=0.56

p<0.001 |

r=0.78

p<0.001 |

r=0.59

p<0.001 |

– |

– |

– |

|

(6) Empathy

|

r=0.39

p<0.001 |

r=0.62

p<0.001 |

r=0.55

p<0.001 |

r=0.67

p<0.001 |

r=0.67

p<0.001 |

– |

–

|

| (7) Self-Control |

r=0.19

p<0.001

|

r=0.54

p<0.001 |

r=0.74

p<0.001 |

r=0.51

p<0.001 |

r=0.66

p<0.001 |

r=0.50

p<0.001 |

– |

|

(8) CSUS

|

r=0.49

p<0.001 |

r=0.47

p<0.001 |

r=0.43

p<0.001 |

r=0.44

p<0.001 |

r=0.42

p<0.001 |

r=0.31

p=0.004 |

r=0.39

p<0.001

|

Discussion

The focus of Study 2 was to determine whether the results of Study 1 would replicate in a second, younger, sample and whether the findings linking ToM with social emotional functioning would extend to a broader range of facets of social emotional functioning. Similar to Study 1, ToM as a global construct measured by the CSUS was positively predictive of children’s social-emotional strengths (i.e., prosocial behaviour) and negatively predictive of social-emotional difficulties on the SDQ. In terms of social-emotional difficulties, the largest effects were observed for conduct problems, followed by hyperactivity and impulsivity, and smaller effects were observed for peer relationship problems and emotional symptoms. Moreover, individual differences in this global measure of ToM predicted all 7 facets of social skills with the largest relationships observed in communication and cooperation. That is, children with a greater understanding of mental states, even after controlling for age-related improvements, exhibit greater social-emotional skills in terms of communication, cooperation, assertion, responsibility, engagement, empathy and self-control.

Across two studies we provide evidence that ToM, as a whole, predicts several critical aspects of children’s social-emotional functioning. Importantly then, the results from the earlier body of literature do not appear to be specific to children’s false belief understanding (i.e., the most commonly used measure) since false belief understanding only represents a single item in the 18-item CSUS.

General Discussion

A primary objective of this research was to corroborate and expand on earlier work suggesting an important link between children’s mental state understanding, or ToM, and children’s social-emotional functioning, especially given the limitations with one of the most commonly used methods. Specifically, we aimed to determine whether theory of mind as a whole, rather than some specific aspect or correlate of theory of mind predicted social-emotional functioning. By including multi-dimensional measures of these constructs, we were able to capture the multi-faceted nature of both ToM and social-emotioning functioning. The majority of earlier work on ToM, and its relationship to social-emotional functioning had relied on laboratory-based measures that tapped one or more specific aspects of ToM, most often the false belief task. As a result, previous research was limited in its ability to capture the full scope of individual differences in children’s ToM. In addition, this work helps elucidate the specific facets of children’s social-emotional functioning that are predicted by individual differences in their mental state understanding. By including multiple facets of social-emotional functioning within the same studies (12 facets in total) we can compare the magnitude of each of their respective relationships to children’s mental state understanding. Finally, this work provides a novel contribution to the literature by extending the research on the validity of the still relatively new CSUS measure as a measure of individual differences.

Children’s ToM as a Global Construct Predicts Social-Emotional Functioning

“In Study 1 children’s mental state”… rather than “Based on our findings from…” Based on our findings from Study 1, children’s mental state understanding, as measured by the CSUS, was positively predictive of children’s social-emotional strengths on the SDQ, namely prosocial behaviour, and negatively predictive of children’s social-emotional difficulties on the SDQ. Specifically, modest negative correlations were observed between children’s mental state understanding and their hyperactivity and impulsivity and conduct problems. Study 2 replicated these findings showing again that children’s ToM, was positively predictive of prosocial behaviour, and negatively predictive of children’s social-emotional difficulties, as measured by the SDQ. This time, in a sample with a younger mean age, we observed a larger relationship between children’s ToM and their level of social-emotional difficulties. Here, we again observed moderate negative correlations between children’s ToM and their hyperactivity and impulsivity and conduct problems, and also observed smaller, but significant, correlations with peer relationship problems and emotional symptoms, with the weakest relationship in the emotional symptoms. Importantly, Study 2 also revealed that ToM was positively predictive of a broader range of social skills, including seven additional facets measured by the SSIS. Here, children with better ToM demonstrated increased social-emotional skills in terms of communication, cooperation, assertion, responsibility, engagement, empathy and self-control.

ToM and Prosocial Behavior

The findings of Study 1 and Study 2 between ToM and different facets of social emotional functioning lend support to earlier claims that ToM predicts these different facets and help to rule out concerns that these findings are limited to false belief understanding or correlates of false belief understanding such as cognitive abilities like working memory or executive functioning. For instance, the relationship between ToM and prosocial behaviour found in both Study 1 and Study 2 is consistent with the aforementioned meta-analysis of 76 studies, which found that children with more sophisticated ToM understanding are more likely to act prosocial [53]. Importantly, the current work expands on these findings by using a global measure to show that ToM as a whole, not just certain aspects of ToM, such as false belief reasoning, predict children’s prosocial behaviour.

ToM and Hyperactivity and Impulsivity

In terms of social-emotional difficulties, recall that a smaller body of literature examining the relationship between ToM and hyperactivity and impulsivity similarly relied on laboratory-based measures focused on the use of false belief tasks and/or emotion understanding. The relationship between ToM and hyperactivity and impulsivity found in both Study 1 and Study 2 is consistent with previous research suggesting that children with more developed ToM have lower levels of hyperactivity and inattention [61,78,79]. The current findings support and expand upon this earlier research to show that ToM as a whole predicts children’s hyperactivity and impulsivity.

ToM and Conduct Problems

Recall that for conduct problems and ToM the relationship was less clear in previous research (e.g., [66-69]). Again, the work that has been conducted relied heavily on the use of false belief tasks or another laboratory-based ToM measure (i.e., emotion understanding) making it unclear whether ToM, as a global construct, was an important predictor of conduct problems. The relationship observed between ToM and conduct problems in both Study 1 and Study 2 is consistent with research suggesting that children with Conduct Disorder tend to display deficits in mental state understanding (e.g., [66]). Again, the current findings expand upon this research to show that ToM as a whole predicts children’s conduct problems and may shed light on theories viewing deficits in ToM as a precursor for the difficulties children with conduct disorder can have in responding to others’ distress cues [67,80]; see also [81].

ToM and Peer Relationship Problems

As previously mentioned, the majority of previous research examining peer relationship problems and ToM also relied heavily on the use of false belief tasks, although some work has also examined other ToM measures (i.e., emotion understanding). Although we found somewhat mixed evidence of ToM as a predictor of the 5-item peer relationship problems subscale of the SDQ (i.e., a significant moderate relationship in the younger sample in Study 2 but a weak relationship in Study 1), we consistently observed strong positive relationships between ToM and the seven facets of children’s social skills measured in the SSIS. Arguably, communication, cooperation, assertion, responsibility, engagement, empathy and self-control are all important social skills that contribute to peer relationships. As such, the current findings are largely consistent with previous research showing that better ToM abilities predict better peer relationships. For instance, these findings support research showing that ToM predicts more peer cooperation in independent play [82], higher peer acceptance and lower peer rejection [83,84], and a lower likelihood of being a victim or perpetrator of bullying [85]. The current work expands on this earlier research by using a global measure of mental state understanding to show that ToM as a whole, not just one or two tasks or aspects, predicts peer relationships. As such general approaches to fostering theory of mind rather than targeting false belief understanding specifically would likely have the most potential for prevention and intervention techniques aimed at improving children’s interpersonal relations.

ToM and Emotional Symptoms

Finally, recall that previous research examining emotional symptoms and ToM is very limited, especially in children. Given the weak relationship between ToM and emotional symptoms observed in Study 2 and the null relationship observed in Study 1, we refrain from drawing any conclusions about the link between ToM and children’s emotional symptoms. It is possible that the scarcity of published research in this area stems from ‘the file drawer problem’ (i.e., null results tend to be reported less), but it is also possible this remains an understudied area. Either way, this seems like an important direction for future research given the meta-analytic evidence of a link between depression and ToM deficits in adults [63], also see [71]. Do the ToM deficits associated with emotional symptoms only manifest later in development, or is the research with children using the wrong research tools?

Is the Relationship between ToM and Children’s Social Emotional Functioning Causational?

Although we observe an association between ToM and children’s overall social emotional functioning, we acknowledge that the correlational design of our studies prevents us from establishing causality. It is possible that children’s social-emotional functioning predicts greater ToM understanding, rather than the other way around. Alternatively, or in addition, ‘third’ variables, including executive function (i.e., working memory and inhibitory control), IQ and language (e.g., verbal ability), or still other variables may account for the current results, in whole or in part. Importantly, the critical focus of this work was not to determine if a causal relationship existed between children’s ToM and social-emotional functioning, rather it was to test whether, and to what degree, ToM as a whole is associated with children’s social-emotional functioning or whether earlier findings were limited to specific ToM measures. Even without establishing causality, this work identifies key areas where deficits in ToM can serve as early warning signs or risk factors and help lead to earlier diagnosis or support. For example, children with deficits in ToM appear to be at risk for experiencing conduct problems even if their ToM is not playing a causal role. Moreover, establishing the relationship between theory of mind and various aspects of social emotional functioning lays the critical groundwork for future research aimed at testing prevention or intervention approaches to foster ToM to see if there are corresponding changes in children’s subsequent social-emotional functioning. Although this work is correlational in nature, we wish to highlight just a few of the many reasons, supported by previous research, to suspect that better ToM does play a causal role, or roles (both proximate and distal), in one’s social-emotional health and wellbeing. One contribution of mental state understanding in children’s social-emotional functioning is demonstrated by its role in fostering empathy and prosocial behaviour [48,49]. The capacity to think and reason about another person’s perspective is argued to be a requirement for the development of empathy [86]. The development of empathy is essential for social-emotional functioning because it enables one to understand and share the feelings of others, and promotes the development of prosocial (i.e., helping) behaviours. For example, research has found that actively imagining and inferring how another person would feel induces empathetic responses and prosociality in participants [48]. As a second example, experimental data from children reveal that they are selective in their prosocial behaviour towards specific others. That is, they fail to share with people who intentionally fail to cooperate, but not people who are unintentionally uncooperative or unable to help [26], demonstrating how their sensitivity to others’ mental states plays a causal role in how they interact with other individuals. A third example of the contribution of ToM in children’s social-emotional functioning is the vital role it plays in language development and communication, which are critical in virtually all social interactions. ToM is an important contributor to the acquisition of language (e.g., [22]), and deficits in ToM in children with autism have been implicated as causal contributors to the language deficits in children with autism [87]. For example, children with autism have deficits in ToM and experience difficulty when making inferences about a speaker’s intentions when learning a new word, leading to word learning errors when compared with typically developing children [88]; also see [89-91]. Likewise, the pragmatic aspects of language (e.g., sarcasm) can also be more challenging for individuals with autism, as it involves utilizing the social context to infer the speaker’s intentions [92,93]. As a final example, ToM also contributes to children’s social-emotional functioning via its role in selective social learning. Social learning is universal and plays a critical role in children’s cognitive and social development (e.g., [5,94,95]), as much of the information children acquire comes from other people. Importantly, children use their ToM to avoid falling prey to misinformation from people who have a history of being overconfident [96], or people who try to intentionally deceive (e.g., [97]). Taken together these separate lines of research are consistent with the claim that ToM plays a causal role, or several causal roles, in fostering better social-emotional functioning. Note that this is by no means an exhaustive review of the myriad of ways enhanced ToM promotes better social-emotional functioning, nor are we suggesting that it accounts for all of the relationships between ToM and facets of social-emotional health. For instance, there is reason to suspect that the deficits in ToM associated with hyperactivity and impulsivity (e.g., in those with ADHD) are a consequence of the hyperactivity or co-morbid neurological dysfunction [63,98]. Furthermore, there is most likely a bi-directional interplay between children’s ToM and their social-emotional functioning. For example, children with more developed ToM may have better social-emotional functioning and more friends, and through their greater number of social interactions those individuals can learn even more about others’ mental states. Conversely, children with deficits in ToM may have poorer social-emotional functioning, which may lead to fewer social interactions and correspondingly fewer opportunities to improve their ToM.

Limitations, Future Directions, and Concluding Remarks

Taken together, the current research advances our understanding of the nature of the relationship between children’s ToM and social-emotional functioning by utilizing multi-faceted measures to provide a more comprehensive account of children’s functioning. The current research also adds support for the validity and utility of using the relatively new CSUS parentreport measure to capture individual differences in ToM. This work shows that the CSUS was differentially predictive of children’s prosocial behaviour and social skills (i.e., positively correlated) and negatively predictive of problem behaviours such as conduct problems and hyperactivity and impulsivity. These findings extend the convergent validity of the CSUS by demonstrating its relationship to children’s social-emotional functioning (i.e., SDQ and SSIS) expanding the initial validation CSUS work examining its relation with laboratory-based ToM tasks (e.g., contents false-belief tasks, knowledge-access tasks, level two perspective-taking tasks [8]).

We recognize, however, that there are limits to the validity and utility of parent-report based questionnaires like the CSUS and urge some caution in interpreting the validity and utility of the results given that the current work relies solely on the use of parent-report measures. On the downside, parents may provide systematic error based on preconceived biases they have about their children (e.g., overly optimistic or positivity bias). Moreover, only one parent completed the parent reports, the vast majority were mothers, offering a singular parent perspective of their child. On the upside, parent-reports are hugely informative as children spend the majority of their time with their parents and parents observe their behaviour across many different contexts over an extended period of time. As a result, parents are uniquely situated to assess their child’s abilities, and as some work suggests may do so better than laboratory-based measures [99-101].

It is also important to note that as a first step we limited our sample to typically developing children. Future research that includes clinical samples of children (e.g. ADHD, conduct disorder, ASD, childhood depression and anxiety) may provide an even more comprehensive understanding of the relationship between ToM constructs and social-emotional functioning. Finally, future research should consider adding the CSUS as an additional measure of ToM, alongside other laboratory-based ToM measures. Our work is consistent with much of the earlier research using false beliefs tasks; however, our research suggests that there is a lot more variability in ToM and although ToM as a whole predicts social-emotional functioning it is important to also examine the role of each subcomponent of ToM. In a recent systematic review of ToM measures in children, Beaudoin and colleagues [2] concluded that there are over 39 different types of ToM sub-abilities.

In summary, the current research importantly expands upon our understanding of the critical relationships between children’s ToM and their social-emotional functioning by utilizing multi-faceted measures that provide a more comprehensive and ecologically valid picture of children’s functioning. The bulk of previous research has been limited to one or two facets of ToM or taken a piecemeal approach to social-emotional functioning. This research documents the important relationships between children’s ToM and several facets of social-emotional functioning, including several strengths (i.e., prosocial behaviour, communication, cooperation, assertion, responsibility, engagement, empathy and self-control) and difficulties (i.e., conduct problems, peer relationship problems, hyperactivity and impulsivity, and to a lesser extent emotional symptoms). Developing further techniques to improve mental state understanding in children will be an especially fruitful avenue given that early childhood is a sensitive time for the development of key cognitive skills, and a time when cognitive malleability is high. There are two potential avenues for fostering children’s social-emotional skills and minimizing difficulties: (a) interventions for children to promote their ToM, and (b) interventions for parents to foster their ToM. We anticipate that the earlier intervention techniques are employed the more likely they are to be successful at fostering the many positive social-emotional life outcomes associated with more accurate mental state understanding. Research in this area is vital as early interventions aimed at fostering mental state understanding show tremendous promise to enhance children’s social-emotional health and wellbeing.

References

- Cohen J, Onunaku N, Clothier S, Poppe J (2005) Helping young children succeed: Strategies to promote early childhood social and emotional development. Research and Policy Report, 1-20.

- Beaudoin C, Leblanc E, Gagner C, Beauchamp MH (2020) Systematic review and inventory of theory of mind measures for young children. Frontiers in Psychology 10: 1-23. [crossref]

- Wimmer H, Perner J (1983) Beliefs about beliefs: Representation and constraining function of wrong beliefs in young children’s understanding of deception. Cognition 13: 103-128.

- Newen A, Wolf J (2020) The situational mental file account of the false belief tasks: A new solution of the paradox of false belief understanding. Review of Philosophy and Psychology 1-28.

- Poulin-Dubois D, Brosseau-Liard P (2016) The developmental origins of selective social learning. Current Directions in Psychological Science 25: 60-64. [crossref]

- Birch SAJ, Li V, Haddock T, Ghrear SE, Brosseau-Liard P, et al. (2017) Perspectives on perspective taking: How children think about the minds of others. Advances in Child Development and Behavior .52: 185-226. [crossref]

- Wellman HM, Liu D (2004) Scaling of theory-of-mind tasks. Child Development 75: 523-541. [crossref]

- Tahiroglu D, Moses LJ, Carlson SM, Mahy CEV, Olofson EL, et al. (2014) The children’s social understanding scale: Construction and validation of a parent-report measure for assessing individual differences in children’s theories of mind.Developmental Psychology 5: 2485-2497. [crossref]

- Chandler MJ, Birch SAJ (2010) The Development of Knowing. In The Handbook of Life-Span Development.

- Flavell J H (1999) Cognitive development: Children’s knowledge about the mind. Annual Review of Psychology 50: 21-45. [crossref]

- Hughes C, Leekam, S (2004) What are the Links Between Theory of Mind and Social Relations? Review, Reflections and New Directions for Studies of Typical and Atypical Development. Social Development 13: 590-619.

- Wellman HM, Lagattuta KH (2000) Developing understandings of mind. In: Understanding other minds: Perspectives from developmental cognitive neuroscience, 21-49.

- Goodman R (1997) The strengths and difficulties questionnaire: A research note. Journal of Child Psychology & Psychiatry 38: 581-586. [crossref]

- Gresham FM, Elliott SN (2008) Social skills improvement system: Rating scales. Pearson Assessments.

- Flavell JH, Miller PH (1998) Social cognition. Cognition, perception, and language.2: 851-898.

- Gopnik A, Astington JW (1988) Children’s understanding of representational change and its relation to the understanding of false belief and the appearance-reality distinction.Child Development 59: 26-37. [crossref]

- Flavell JH, Flavell ER, Green FL (1983) Development of the appearance-reality distinction. Cognitive Psychology 15: 95-120. [crossref]

- Flavell JH (1986) The development of children’s knowledge about the appearance-reality distinction. American Psychologist 41: 418-425.

- Baron-Cohen S, Leslie AM, Frith U (1985) Does the autistic child have a “theory of mind”? Cognition 21: 37-46. [crossref]

- Perner J, Leekam SR, Wimmer, H (1987) Three‐year‐olds’ difficulty with false belief: The case for a conceptual deficit. British Journal of Developmental Psychology 5: 125-137.

- Wellman HM, Cross D, Watson J (2001) Meta-analysis of theory-of-mind development: The truth about false belief. Child Development 72: 655-684. [crossref]

- Bloom P, German TP (2000) Two reasons to abandon the false belief task as a test of theory of mind. Cognition 77: 25-31. [crossref]

- Ghrear S, Baimel A, Haddock T, Birch SA (2021) Are the classic false belief tasks cursed? Young children are just as likely as older children to pass a false belief task when they are not required to overcome the curse of knowledge. PloS One 16: e0244141. [crossref]

- Onishi KH, Baillargeon R (2005) Do 15-month-old infants understand false beliefs? Science 308: 255-258. [crossref]

- Meltzoff AN (1995) Understanding the intentions of others: Re-enactment of intended acts by 18-month-old children. Developmental Psychology 31: 838-850.

- Dunfield KA, Kuhlmeier VA (2010) Intention-mediated selective helping in infancy. Psychological Science 21: 523-527. [crossref]

- Hamlin JK (2013) Failed attempts to help and harm: Intention versus outcome in preverbal infants’ social evaluations. Cognition 128: 451-474. [crossref]

- Woodward AL, Sommerville JA, Gerson S, Henderson AM, Buresh J (2009) The emergence of intention attribution in infancy. Psychology of Learning and Motivation 51: 187-222. [crossref]

- Repacholi BM, Gopnik A (1997) Early reasoning about desires: Evidence from 14-and 18-month-olds. Developmental Psychology 33: 12-21. [crossref]

- Wellman HM, Harris PL, Banerjee M, Sinclair A (1995) Early understanding of emotion: Evidence from natural language. Cognition & Emotion 9: 117-149.

- Izard CE, Harris P (1995) Emotional development and developmental psychopathology. Developmental psychopathology 1: 467-503.

- Denham SA (1998) Emotional development in young children. Guilford Press.

- Birch, S. A (2005) When knowledge is a curse: Children’s and adults’ reasoning about mental states. Current Directions in Psychological Science 14: 25-29.

- Birch SAJ, Bloom P (2003) Children are cursed: An asymmetric bias in mental state attribution. Psychological Science 14: 283-286.

- Birch SAJ, Bloom P (2002) Preschoolers are sensitive to the speaker’s knowledge when learning proper names. Child Development 73: 434-444. [crossref]

- Happe FGE (1994) An advanced test of theory of mind: Understanding of story characters’ thoughts and feelings by able autistic, mentally handicapped, and normal children and adults. Journal of Autism and Developmental Disorders 24: 129-154. [crossref]

- Peterson CC, Wellman HM, Slaughter V (2012) The mind behind the message: Advancing theory-of-mind scales for typically developing children, and those with deafness, autism, or Asperger Syndrome. Child Development 83: 469-485. [crossref]