Abstract

The paper uses the emerging science of Mind Genomics to understand emotional responses (frustration) and prevention of decisions experienced when the respondent reads test vignettes describing websites which provide medical information (health) and/or medical insurance information (health-related finances). Respondents read and evaluated combinations of 2–4 messages (answers to questions), with the messages combined according to an experimental design. The ratings on a five- point scale provided an assessment of both estimated ‘frustration’ and estimated ‘difficulty to make a decision.’ The analysis related the presence/absence of the messages to both frustration and to inability to make a decision. Three mind-sets emerged, suggesting that the estimated frustration encountered in difficult web searches for healthcare information is not unidimensional. The three emergent mind-sets are: MS1 (moderate latent frustration), MS2 (little latent frustration but easily & strongly frustrated) and MS3 (a great deal of latent frustration, doing best with a very simple, direct search process). The paper concludes with the presentation of the PVI, personal viewpoint identifier, which allows the healthcare provider to understand the sensitivities of the prospect, in terms of what problems increase frustration for that prospect. The objective of the PVI is to improve the user experience by understanding the mind of the user.

Introduction

The use of the Internet for searching and finding health information is rising and is accompanied by the realization that the ‘experience’ itself must be made easier. We are no longer in the birthing years of the 1970’s – 1990’s, when simply having access to a large world of information sufficed, astonishing those who had grown up in a world where information was to be sought after, no matter what the difficulty [1]. Experts have been replaced by websites, by chat advisors, by guided searches, so much so that often there is no expert but rather guidance embedded in the software and the instructions emerging from the software. People often first search the internet for information about diseases, then talk to their friends, and then encounter the doctors [2]. For diseases such as cancer, in earlier days a death sentence for many has spawned an entire network of communications and information [3–5]. The same goes for diabetes [6] and for heart disease [7]. As a consequence, medical information, may be getting increasingly dense over time as medicine advances and the literature and alternative options become overwhelming, for example the “BELONG” community of cancer patients [8]. Much of this this transition and new world is contained within the words ‘user experience,’ a phrase which encompasses the range from one’s impression of the website to one’s experience with the website to achieve certain goals. In the previous generations of science this area would have been subsumed under the rubric ‘man-machine interaction’ in the world of ‘human factors.’

This paper focuses specifically on one aspect of the user experience, the source for diagnosis and treatment information, both in terms of medical information and in terms of medical coverage information. The objective is to quantify the important of different aspects of the search as they drive expected frustration and expected inability to make a decision [9]. A traditional strategy to obtain the information is by a guided interview. The research instructs respondents to answer questions about needs, asks about sources of frustration, and experienced challenges in choosing an answer. The study would also measure responses when participants are exposed to the actual information and instructed to make a decision. Our approach complements this typical study just described. Our experiment presents respondents with vignettes defining the situation and instructs the respondents to select the likely outcome based upon the description of the experience. The analysis deconstructs the response to these vignettes into the contribution of the different elements of the vignette as drivers of expected frustration.

Mind Genomics as an emerging science traces its history to a combination of statistics (experimental design [10] conjoint measurement as ways to study decision-making [11, 12]. Mind Genomics expands topics from the laboratory out to everyday life. Furthermore, Mind Genomics expands the capabilities of design of experiments, using individual permutations of a basic, fundamental design. The consequence is that one need not overthink the selection of combinations of elements to go into the design. The permutation covers a wider amount of the space, analogous to the way the MRi in medicine takes many pictures of underlying tissue, not just the ‘correct one’, which may not even be known [13,14] The result has been the creation of a new science with applications from policy to products, from law to health and everyday life [15,16].

Mind Genomics method

Mind Genomics approaches the problem by an easy to construct, easy to analyze experiment. The experiment comprises a topic (sources of frustration and choice prevention during the search for medical information on the Internet), a set of four questions which ‘tell a story’ (the Socratic approach), and then requires four simple answers to each question, or a total of 16 answers. The Mind Genomics paradigm is designed to be fast, iterative, provide optimal results, and powerful results terms of a measure of the ability of each answer to ‘drive’ the response, a measure of conscious judgment, as well as measuring response time, a metric which reflects deeper cognitive processing or emotions.

The set of four questions and the 16 answers, four answers to each question, appears in Table 1. The objective is to work with untrained respondents, over the Internet, requiring that the answers be simple, direct, and easy to comprehend. The questions in Table 1 never appear in the test stimuli. Rather, the test stimuli comprise simple vignettes, combinations of the answers, 2–4 answers for any vignette. Each vignette has at most one answer from a question, but for many of the vignettes one or two questions do not contribute an answer. This design structure is deliberate, for statistical reasons, specifically to increase the strength of the analytic tool, OLS (ordinary least-squares) regression.

Table 1. The four questions and the four answers to each question

|

Question 1 – Stage of Life |

|

|

A1 |

Current disease |

|

A2 |

Time since diagnosis |

|

A3 |

Stage of disease |

|

A4 |

Transition in life |

|

Question 2 – Reason for search |

|

|

B1 |

Make best decision |

|

B2 |

Make best decision considering health |

|

B3 |

Make best decision considering my situation |

|

B4 |

Make best decision for my future |

|

Question 3 – Reactions to information presented |

|

|

C1 |

Information is relevant but hard to understand |

|

C2 |

Have to do multiple searches before making a decision |

|

C3 |

Information is scattered – frustrates me |

|

C4 |

Information doesn’t seem trustworthy |

|

Question 4 – Information Wanted |

|

|

D1 |

Looking for: specific rates |

|

D2 |

Looking for simple way to contact and get answers |

|

D3 |

Looking for specific services |

|

D4 |

Looking for process |

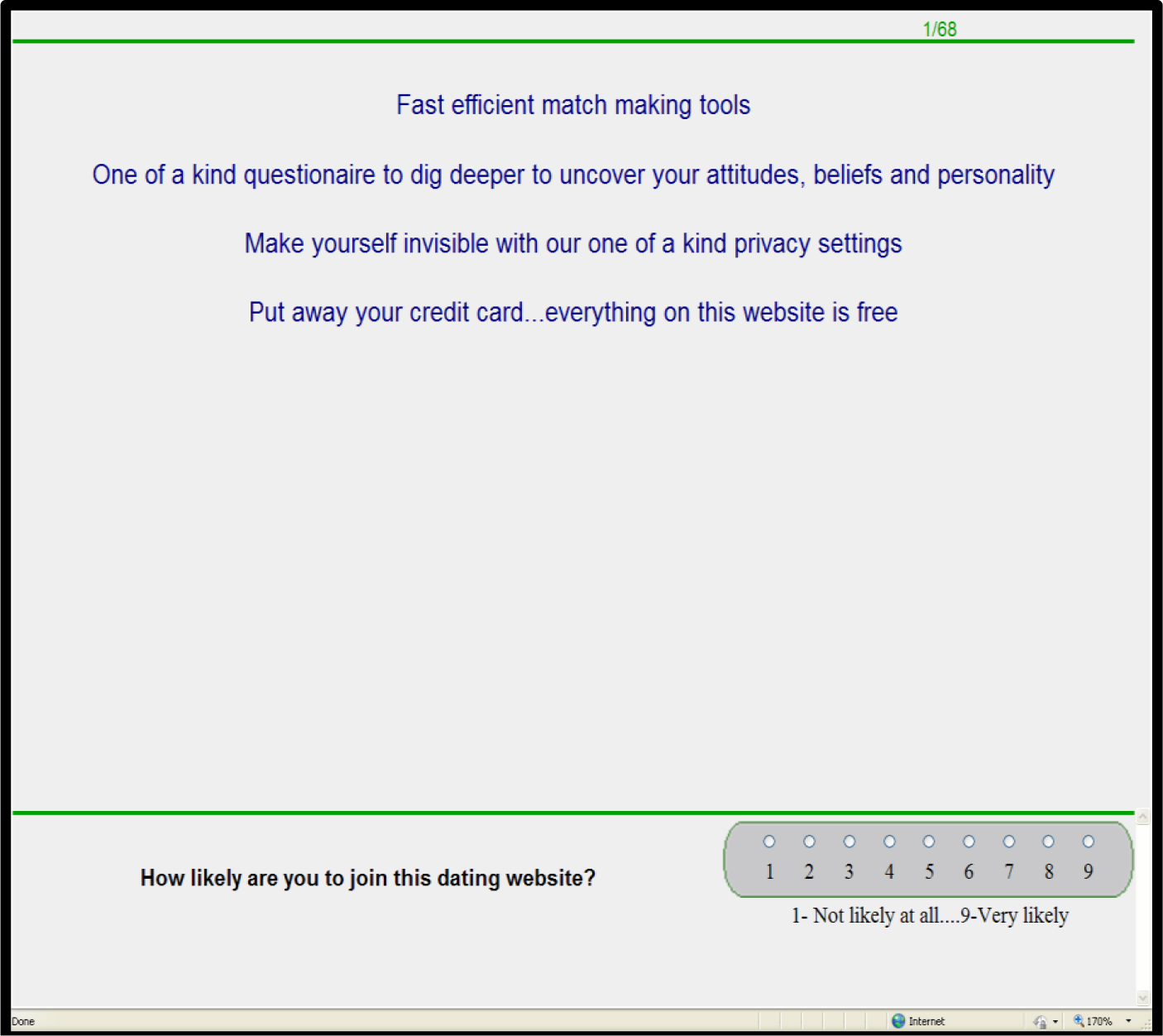

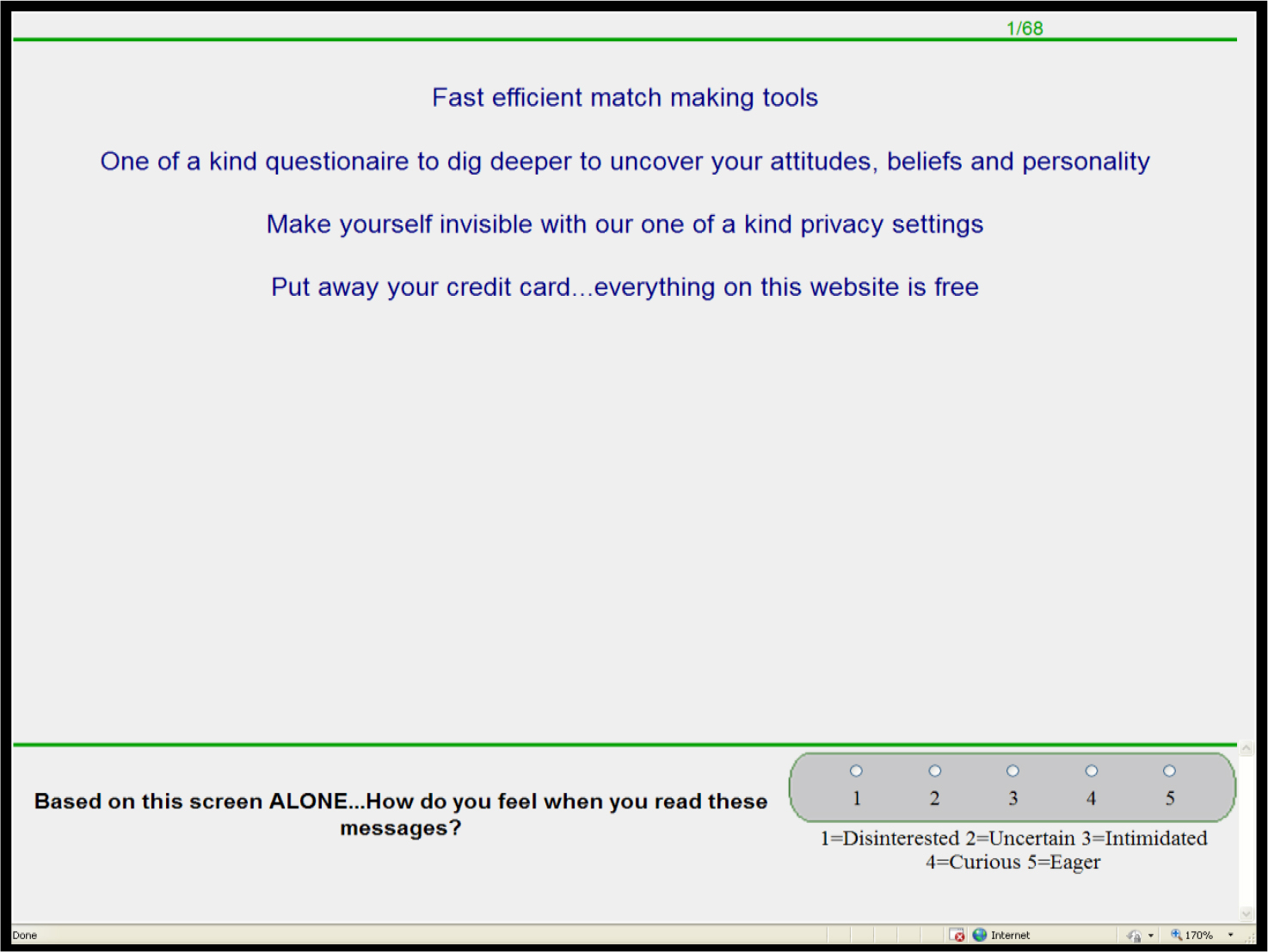

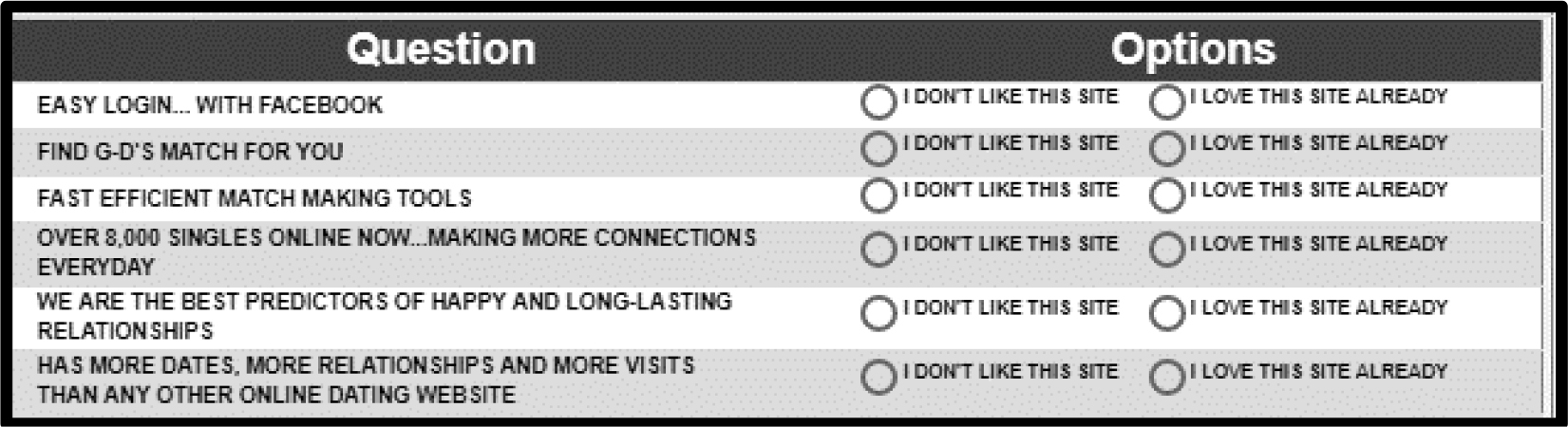

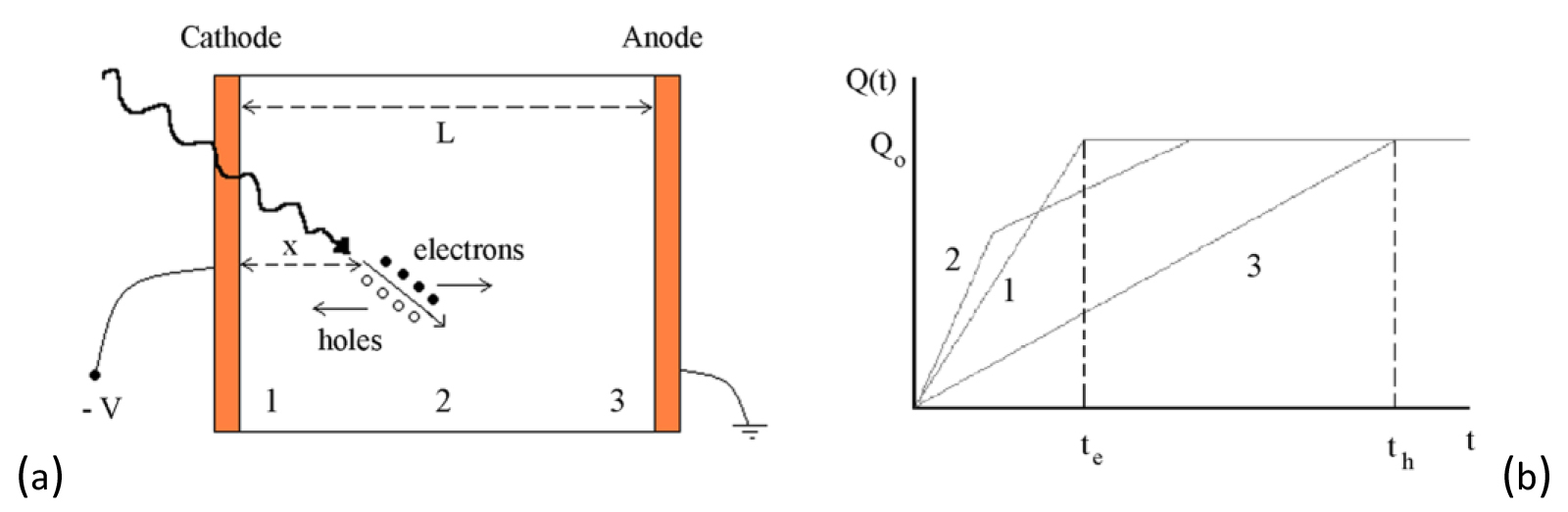

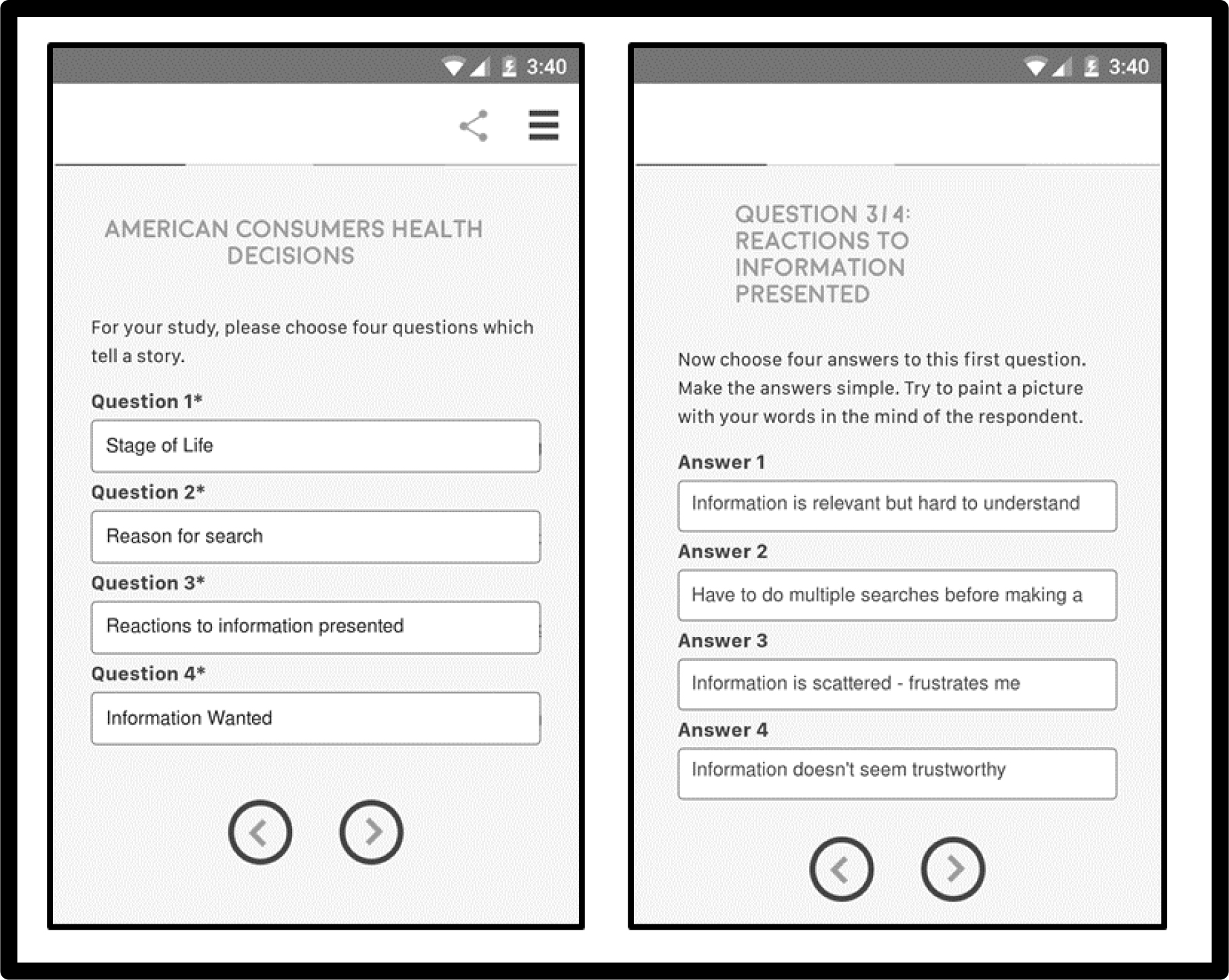

Figure 1 (left panel) shows the screen shot requiring the researcher to ask four questions. Figure 1 (right panel) shows one question, and the four answers to that question. The answers should be stand-alone phrases that can be understood, in and of themselves. The set-up system for Mind Genomics thus encourages critical thinking, and in the end, a deeper understanding of the topic by combining this thinking with affordable, rapid experimentation among prospective customers.

Figure 1. Screen shots from the set-up of the study. The left panel shows the four questions. The right panel shows the four answers provided by the research to question 3

Experimental design

Each respondent evaluated a unique set of 24 combinations or vignettes. Each vignette comprised 2–4 elements or answers, no more than one answer from any question. The answers were stacked atop each other. The experimental design ensures that for each individual the 16 answers appear several times, and an equal number of times. The incompleteness of the design, with some vignettes absent one or two answers, ensures that the OLS (ordinary least-squares) regression will run without any problem. When the researcher requires each vignette to contain exactly one answer or element from each question, a very common practice, the sad, actually destructive outcome is that the OLS regression can return only with relative values for the coefficients, not absolute values, the cause being the multi-collinearity among the elements due to the requirement that each vignette be ‘complete’ with exactly one answer from each question.

Statistical analysis

The rating scale comprises five points, covering two dimensions, frustration and inability to make a decision. The actual rating scale appears below

Please read the experience below about a person searching for medical information about medical insurance plans. Select which of the following phrases describe the feeling

1=no problem

2 =not frustrated … Easy to make decision

3=not frustrated … Hard to make decision

4=frustrated … Easy to make decision

5=frustrated … Hard to make decision

We create four variables from this single scale, as follows:

The two ‘negative outcomes’

Frustrate YES (abbreviated as Frust YES) – when the rating is 4 or 5, we code this new variable, Frustrate YES, as 100. Otherwise we code Frust YES as 0.

Decide NO (abbreviated as Dec NO) – when the rating is 3 or 5, we code this new variable, Decide NO, as 100. Otherwise we code DEC NO as 0.

The two ‘positive outcomes’

Frustrate NO (abbreviated as Frust NO) – when the rating is 1,2 or 3, we code this new variable, Frust NO, as 100. It should be obvious that Frust NO is the inverse of Frust YES

Decide YES (abbreviated as Dec YES) – when the rating is 1, 2, or 4, we code this new variable, Dec YES, as 100. Otherwise we code it as 0. Again, Dec YES is the inverse of Decide NO.

The experimental design enables us to run models, at the level of the individual, relating the presence/absence of the 16 elements or answers to either the two negative outcomes, or to the two positive outcomes, respectively. The analysis pools all the data from the relevant subgroup, and runs one entire or ‘grand’ models. The analysis will, however, run individual-levels models for the mind-set segmentation, discussed below in the section on mind-sets.

The equation relating the presence/absence of the 16 elements to the ratings (positive or negative outcome) is expressed by the simple equation: Specific Outcome = k0 + k1(A1) + k2(A2) … k16(D4)

The additive constant, k0, shows the estimated value of the variable (e.g., Frust YES), in the absence of elements. Of course, all vignettes comprised 2–4 elements by design, so that the additive constant is an estimated value. It can be considered the baseline, the estimated percent of the time one is expected to hear that there a negative or positive experience, even without information about what exactly was presented.

The response time is defined as the time in seconds (to the nearest tenth of second) between the time that the vignette appears on the screen and the time that the respondent assigns a rating. The computer program measures that time. The response time model is written almost in the same way, but without the additive constant. We interpret the model as telling us the estimated number of seconds that the respondent spent ‘processing’ the specific element. The response time is a so-called objective measure, not under the control of the respondent. The respondent may not even be aware of the processing.

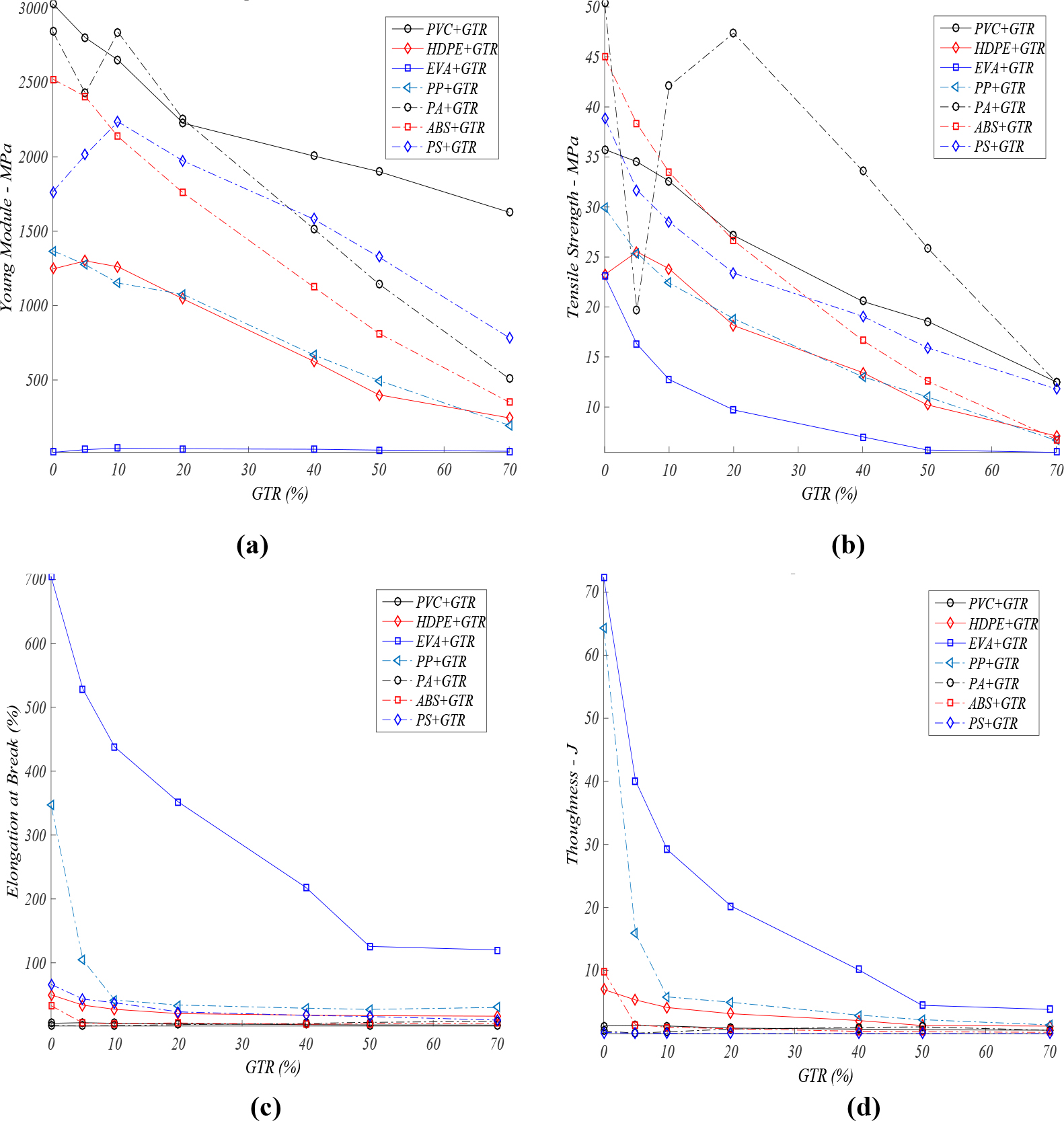

Total panel

Table 2 shows the parameters of five models relating the presence/absence of the 16 elements/answers from the four questions to response time (fifth data column) and to four “NET” ratings, those ratings talking about frustration (Frust YES, Frust NO), and those talking about the ability to make a decision (Dec YES, Dec NO). The table is arranged to show the elements which drive the negative outcomes (Frust YES, Dec NO), then the response time, and then the elements which drive the positive outcomes (Frust NO, Dec YES).

Table 2. Parameters of the models relating the presence/absence of the 16 elements to the NET negative and the net positive outcomes respectively, as well as to response time

|

NET Negative |

NET Positive |

|||||

|

Total |

Frust Yes |

Dec No |

Response Time |

Frust No |

Dec Yes |

|

|

Additive constant |

20 |

52 |

NA |

80 |

48 |

|

|

C3 |

Information is scattered – frustrates me |

38 |

10 |

1.2 |

-38 |

-10 |

|

C4 |

Information doesn’t seem trustworthy |

19 |

15 |

1.3 |

-19 |

-15 |

|

C1 |

Information is relevant but hard to understand |

16 |

16 |

1.5 |

-16 |

-16 |

|

D3 |

Looking for specifics |

10 |

-4 |

1.8 |

-10 |

4 |

|

C2 |

Have to do multiple searches before making a decision |

9 |

1 |

1.7 |

-9 |

-1 |

|

A1 |

Disease |

4 |

-10 |

1.1 |

-4 |

10 |

|

A4 |

Time since diagnosis |

0 |

-9 |

1.3 |

0 |

9 |

|

A2 |

Stage of disease |

4 |

-9 |

1.1 |

-4 |

9 |

|

A3 |

Current Life stage: Transition |

1 |

-7 |

1.0 |

-1 |

7 |

|

D2 |

Looking for simple way to contact and get answers |

1 |

-2 |

1.7 |

-1 |

2 |

|

B2 |

Make best decision considering health |

4 |

-1 |

1.7 |

-4 |

1 |

|

D1 |

Looking for prices and rates |

5 |

-1 |

1.7 |

-5 |

1 |

|

B4 |

Make best decision for my future |

-2 |

0 |

1.8 |

2 |

0 |

|

D4 |

Looking for process …how to …. |

6 |

0 |

2.0 |

-6 |

0 |

|

B1 |

Make best decision |

-2 |

1 |

1.7 |

2 |

-1 |

|

B3 |

Make best decision considering my situation |

1 |

2 |

1.9 |

-1 |

-2 |

We begin with the additive constant, which gives us a sense of the percent of responses that will be assigned the NET rating in the absence of elements. Of course, all of the vignettes were created according to an experimental design which prescribed 2–4 elements per vignette, making the additive constant a purely calculated parameter. Nonetheless, the additive constant gives us a sense of a baseline response.

The additive constants for the two negative and the two positive outcomes are the following:

Negative: Frust Yes = 20

Negative: Dec No = 52

Positive: Frust No = 80

Positive: Dec Yes = 48

We conclude that there in general, people don’t feel that they are frustrated with the websites giving information (additive constant = 20 for Frus YES versus additive constant = 80 for Frust NO). In contrast, people feel that they cannot make a decision based upon the website (additive constant = 52 for Dec NO versus additive constant = 48 for DEC Yes).

Five specific answers or elements strongly frustrate the five frustrating elements are:

Information is scattered – frustrates me

Information doesn’t seem trustworthy

Information is relevant but hard to understand

Looking for specific answers

Have to do multiple searches before making a decision

Of these, three lead to aborting the decision

Information is scattered – frustrates me

Information doesn’t seem trustworthy

Information is relevant but hard to understand

Response time tells us additional information, namely the degree to which respondent think about the answer

Looking for process … how to…

Make best decision considering my situation

Looking for specifics

Make best decision for my future

Have to do multiple searches before making a decision

Looking for simple way to contact and get services

Make best decision considering health

Looking for: specific rates

Make best decision

Information is relevant but hard to understand

How problems interact with solutions

A key benefit of the permuted experimental design is the ability to assess the nature of the interaction between pairs of elements [13]. The approach is called scenario analysis. The scenario analysis holds a single element constant from one question, and estimates the coefficients of all elements or answers from the other questions.

The method of scenario analysis was applied to determine how the elements or answers to Question D, information wanted, interacted with the remaining elements. As will be seen in this analysis, the interactions can be dramatic. Depending upon the specific type of information wanted, some elements may be seen to frustrate not at all, or turn around and frustrate a great deal.

The process followed these steps for the first dependent variable, the negative outcome Frustrate YES

- Sort the 1200 records into five strata, based upon the specific element or answer from Question D. Question D contribute either no answer to a vignette, or one of four answers. We sort the database into the five strata.

- For each stratum, we estimate the additive constant and the 12 coefficients, A1-C4. We do not use the elements or answers from Question D because they are either absolute, or held constant.

- The results appear in Table 3 for the dependent variable being Frustrate YES, i.e., the combination of answers where the respondent said she or he would be frustrated, whether or not the respondent would make a decision.

- We begin with the additive constant, which is very low when there is no information wanted (additive constant = 18). The basic frustration is highest (additive constant = 35) when the respondent is presented with the task of ‘looking for process how to file the claim.’

- An element can be alternately not frustrating or very frustrating, depending upon what one is searching for. Consider element C2 (Have to do multiple searches before making a decision.) When the respondent is looking for information (specific rates or simple way to get services), there is no frustration. Multiple searches do not lead to much frustration. When the issue specific and concrete (e.g., specific coverage or process to make a claim), the multiple searches becomes frustrating.

- The scenario analysis provides the researcher with a new tool to understand how pairs of elements interact with each other. The researcher need not incorporate specific interactions ahead of time. Rather, the permutation of the underlying experimental design leads naturally to the emergence of interactions, and an easy way to discover them.

Table 3. Scenario analysis showing how the combination of specific elements with elements from the fourth question (information-wanted) drives Frustrate YES

|

Question 4: Information Wanted |

||||||

|

|

Frustrate YES |

none |

Looking for: specific rates |

Looking for simple way to contact and get services |

Looking for specific coverage |

Looking for process how to file claim |

|

D0 |

D1 |

D2 |

D3 |

D4 |

||

|

Additive constant |

18 |

27 |

23 |

26 |

35 |

|

|

C3 |

Information is scattered – frustrates me |

69 |

26 |

30 |

41 |

35 |

|

C4 |

Information doesn’t seem trustworthy |

45 |

8 |

19 |

20 |

14 |

|

C1 |

Information is relevant but hard to understand |

44 |

1 |

11 |

18 |

18 |

|

C2 |

Have to do multiple searches before making a decision |

19 |

1 |

-3 |

25 |

9 |

|

B2 |

Make best decision considering health |

7 |

10 |

-2 |

7 |

-6 |

|

B1 |

Make best decision |

4 |

-1 |

3 |

7 |

-23 |

|

B3 |

Make best decision considering my situation |

-5 |

3 |

9 |

-1 |

-9 |

|

A2 |

Current disease |

-9 |

11 |

6 |

3 |

-5 |

|

A1 |

Current disease stage |

-14 |

9 |

6 |

-2 |

8 |

|

A3 |

Time since diagnosis |

-16 |

4 |

4 |

-1 |

2 |

|

B4 |

Make best decision for my future |

-17 |

3 |

0 |

-5 |

9 |

|

A4 |

Current Life stage: Transitioning |

-25 |

14 |

0 |

2 |

-3 |

We now turn to the second dependent variable, the negative outcome of No Decision Made. The results appear in Table 4. The pattern is radically different.

Table 4. Scenario analysis showing how the combination of specific elements with elements from the fourth question (information-wanted) drives Decision NO

|

Question 4: Information Wanted |

||||||

|

|

Decision NO |

none |

Looking for: specific rates |

Looking for simple way to contact and get services |

Looking for specific coverage |

Looking for process how to file claim |

|

D0 |

D1 |

D2 |

D3 |

D4 |

||

|

Additive constant |

22 |

40 |

40 |

72 |

59 |

|

|

C4 |

Information doesn’t seem trustworthy |

34 |

20 |

10 |

-2 |

17 |

|

C3 |

Information is scattered – frustrates me |

26 |

17 |

7 |

-6 |

5 |

|

B1 |

Make best decision |

24 |

7 |

-7 |

-13 |

7 |

|

B3 |

Make best decision considering my situation |

21 |

6 |

-8 |

-14 |

12 |

|

C1 |

Information is relevant but hard to understand |

19 |

40 |

17 |

-2 |

8 |

|

B4 |

Make best decision for my future |

15 |

4 |

-6 |

-2 |

2 |

|

B2 |

Make best decision considering health |

14 |

5 |

-8 |

-5 |

-3 |

|

A3 |

Current disease |

5 |

-3 |

18 |

-16 |

-28 |

|

C2 |

Have to do multiple searches before making a decision |

3 |

2 |

9 |

-15 |

12 |

|

A2 |

Current disease stage |

-3 |

-13 |

13 |

-17 |

-12 |

|

A4 |

Time since diagnosis |

-3 |

-13 |

9 |

-9 |

-28 |

|

A1 |

Current life stage: Transitioning |

-12 |

-4 |

1 |

-8 |

-16 |

- The greatest basic likelihood of no decision is ‘Looking for specific coverage’ (additive constant = 72.) The next highest likelihood of no decision is ‘Looking for process how to file a claim’ (additive constant = 59). The remaining two elements (Looking for specific rates and Looking for simple way to contact and get answers) show lower additive constants, 40 each. The take-away from this initial finding is that the likelihood of no decision is a function of what people are looking for, with the most problematic being specifics. The website should concentrate on example of specific services, or a way to provide a rate.

- When there is no task, the additive constant is low (22) but many of the elements drive the decision. The most severe is ‘information doesn’t seem trustworthy’ but there are many other elements which strongly drive ‘No Decision.’

- There are specific interactions which make intuitive sense, such as Looking for simple way to contact and get answers (D2) coupled with Current disease stage (A3). We might not immediately think of that, but the data reveals the interaction, and suggests that we pay attention to that possible problem combination.

We now turn to the third and final dependent variable, response time. As noted above, response time does not measure a cognitively meaningful response to the vignette such as Frustrate YES, Decide NO, but rather the length of time required for the respondent to process the information in the vignette, and assign a rating. The equation does not have an additive constant, because without any elements there is no predisposition to respond. Furthermore, our focus is on the effect of one of the four searches, D1-D4. We consider only four strata, each stratum fixing one of the four search goals.

Table 5 shows the parameters of the models. The response times are quite long for the individual elements, often longer than 2.3 seconds, the cut-off level beyond which the cell is shaded, and the numbers in bold text. The interactions are different across the four answer for Question D, ‘Information Wanted.’

Table 5. Scenario analysis showing how the combination of specific elements with elements from the fourth question, information-wanted, drives Response Time

|

Information Wanted (Question 4) |

|||||

|

|

Response Time

|

Looking for: specific rates |

Looking for simple way to contact and get services |

Looking for specific coverage |

Looking for process how to file claim |

|

B2 |

Make best decision considering health |

2.9 |

1.7 |

1.7 |

1.8 |

|

B1 |

Make best decision |

2.5 |

2.7 |

1.8 |

1.8 |

|

A1 |

Current disease stage |

2.3 |

1.1 |

2.0 |

2.0 |

|

B3 |

Make best decision considering my situation |

2.2 |

2.9 |

2.1 |

2.3 |

|

B4 |

Make best decision for my future |

2.0 |

2.7 |

1.4 |

2.8 |

|

C1 |

Information is relevant but hard to understand |

2.0 |

2.3 |

2.7 |

2.4 |

|

C2 |

Have to do multiple searches before making a decision |

1.9 |

2.1 |

2.9 |

2.2 |

|

C3 |

Information is scattered – frustrates me |

1.6 |

1.6 |

2.8 |

1.8 |

|

C4 |

Information doesn’t seem trustworthy |

1.6 |

1.9 |

2.2 |

2.6 |

|

A4 |

Time since diagnosis |

1.8 |

1.5 |

1.9 |

2.8 |

|

A3 |

Current disease |

1.8 |

1.5 |

1.4 |

1.7 |

|

A2 |

Current disease stage |

1.6 |

1.4 |

1.4 |

1.7 |

Looking for: specific rates

Make best decision considering health

Make best decision

Current disease stage

Looking for simple way to contact and get answers

Make best decision considering my situation

Make best decision

Make best decision for my future

Information is relevant but hard to understand

Looking for specifics

Have to do multiple searches before making a decision

Information is scattered – frustrates me

Information is relevant but hard to understand

Looking for process …. how to….

Current disease stage

Make best decision for my future

Information doesn’t seem trustworthy

Information is relevant but hard to understand

Make best decision considering my situation

Key subgroups

The ability to have each respondent evaluate the precise array of vignettes makes it easy to the researcher to look at different groups of respondents, and at the same time be assured that the pooled data will both maintain the statistical independence need for OLS regression, and cover a large proportion of the design space.

We begin again with the net attribute, Frustrate YES. The additive constant shows dramatic group to group differences in the basic likelihood to say ‘frustrated’ when presented with the vignette ‘without elements’ (see Table 6). When we compare the additive constant with the net attribute, Decide NO, we find radical differences. There is a very wide range of basic levels of frustration, as shown by the additive constant, whereas a much narrower range in the basic inability to make a decision.

Table 6. Additive constants for group-based models relating the presence/absence of the 16 elements/answers to both the Net Attribute ‘Frustrate YES’ and the Net Attribute ‘Decide NO’

|

Frustrate YES |

Decide NO |

|

|

Frustrates |

|

|

|

Age: 60 Plus |

26 |

50 |

|

Age: 30–49 |

24 |

60 |

|

Life stage: Family |

23 |

58 |

|

Gender: Female |

23 |

52 |

|

Age: 23–20 |

21 |

40 |

|

Retards Decision |

|

|

|

Life stage; Retire |

18 |

66 |

|

Age: 30–49 |

24 |

60 |

|

Life stage: Just graduated college |

1 |

60 |

|

Neither |

|

|

|

Gender: Male |

18 |

54 |

|

Age 50–59 |

5 |

54 |

Table 7 shows the parameters of the models by each subgroup for Frustrate YES

Table 7. Group models relating the presence/absence of NET Variable Frustrate YES to the 16 elements

|

Net Frustrate YES

|

Male |

Female |

Age 23–29 |

Age 30–49 |

Age 50–59 |

Age 60+ |

Just graduated |

Family |

Retire |

|

|

CONSTANT |

18 |

23 |

21 |

24 |

5 |

26 |

1 |

23 |

18 |

|

|

C3 |

Information is scattered – frustrates me |

28 |

48 |

28 |

45 |

37 |

36 |

17 |

51 |

23 |

|

C4 |

Information doesn’t seem trustworthy |

14 |

24 |

15 |

25 |

9 |

24 |

15 |

29 |

17 |

|

D3 |

Looking for specifics |

14 |

7 |

-2 |

13 |

13 |

16 |

17 |

12 |

12 |

|

D1 |

Looking for rates |

13 |

-2 |

-12 |

8 |

8 |

14 |

30 |

1 |

22 |

|

C1 |

Information is relevant but hard to understand |

10 |

22 |

7 |

13 |

19 |

29 |

19 |

17 |

9 |

|

A1 |

Current life stage: transitioning |

8 |

0 |

10 |

7 |

7 |

-14 |

17 |

2 |

5 |

|

A3 |

Current disease |

8 |

-6 |

3 |

6 |

-2 |

-11 |

18 |

2 |

-3 |

|

D2 |

Looking for simple way to contact and get services |

7 |

-6 |

-8 |

3 |

10 |

-5 |

16 |

-6 |

-4 |

|

D4 |

Looking for process how to file claim |

7 |

5 |

-13 |

6 |

15 |

12 |

13 |

3 |

14 |

|

C2 |

Have to do multiple searches before making a decision |

5 |

13 |

3 |

14 |

7 |

7 |

10 |

12 |

3 |

|

A4 |

Time since diagnosis |

4 |

-5 |

-5 |

1 |

9 |

-11 |

18 |

-5 |

-1 |

|

B2 |

Make best decision considering health |

2 |

7 |

5 |

3 |

5 |

5 |

-1 |

7 |

7 |

|

A2 |

Current disease stage |

1 |

8 |

1 |

1 |

16 |

-2 |

12 |

11 |

10 |

|

B1 |

Make best decision |

1 |

-4 |

0 |

-5 |

-4 |

11 |

11 |

-8 |

14 |

|

B3 |

Make best decision considering my situation |

-4 |

4 |

6 |

-7 |

4 |

9 |

2 |

-6 |

8 |

|

B4 |

Make best decision for my future |

-4 |

0 |

6 |

-6 |

1 |

0 |

1 |

0 |

4 |

Among the most frustrating elements are

Information is scattered – frustrates me

Information doesn’t seem trustworthy

Table 8 shows the parameters of the model by each subgroup for Decide NO

Table 8. Group models relating the presence/absence of NET Variable Decide NO to the 16 elements

|

Net Decision NO |

Male |

Female |

Age 23–29 |

Age 30–49 |

Age 50–59 |

Age 60+ |

Just graduated |

Family |

Retire |

|

|

Additive constant |

54 |

52 |

40 |

60 |

54 |

50 |

60 |

58 |

66 |

|

|

C4 |

Information doesn’t seem trustworthy |

12 |

18 |

15 |

9 |

18 |

27 |

0 |

16 |

19 |

|

C1 |

Information is relevant but hard to understand |

13 |

19 |

9 |

13 |

15 |

25 |

-2 |

16 |

25 |

|

C3 |

Information is scattered – frustrates me |

7 |

13 |

11 |

-3 |

21 |

22 |

-9 |

11 |

8 |

|

C2 |

Have to do multiple searches before making a decision |

-1 |

3 |

6 |

-7 |

-2 |

20 |

-9 |

-5 |

14 |

|

B1 |

Make best decision |

-6 |

8 |

2 |

-6 |

5 |

12 |

-9 |

-3 |

8 |

|

B3 |

Make best decision considering my situation |

-4 |

6 |

-8 |

2 |

-3 |

9 |

-3 |

-2 |

-5 |

|

B4 |

Make best decision for my future |

-2 |

1 |

5 |

-5 |

2 |

3 |

5 |

-4 |

-7 |

|

B2 |

Make best decision considering health |

-4 |

2 |

5 |

-12 |

12 |

0 |

4 |

-5 |

-7 |

|

A2 |

Current disease stage |

-9 |

-9 |

-8 |

-11 |

-8 |

-7 |

-15 |

-6 |

7 |

|

A4 |

Time since diagnosis |

-3 |

-15 |

-13 |

-5 |

-16 |

-7 |

-7 |

-15 |

6 |

|

A1 |

Current life stage: Transitioning |

-4 |

-15 |

-8 |

-11 |

-13 |

-8 |

-8 |

-15 |

0 |

|

D1 |

Looking for specifics |

-3 |

0 |

-4 |

3 |

-5 |

-11 |

9 |

2 |

-12 |

|

D2 |

Looking for simple way to contact and get answers |

-3 |

-2 |

8 |

-3 |

-2 |

-11 |

-5 |

5 |

-9 |

|

A3 |

Current disease |

-2 |

-12 |

-3 |

-11 |

4 |

-15 |

-12 |

-11 |

4 |

|

D4 |

Looking for process… how to… |

0 |

-1 |

7 |

2 |

4 |

-15 |

6 |

5 |

-19 |

|

D3 |

Looking for specifics |

-7 |

-3 |

-7 |

1 |

-4 |

-19 |

8 |

-1 |

-17 |

Among the elements which hinder decisions are

Information doesn’t seem trustworthy

Information is relevant but hard to understand

Information is scattered – frustrates me

The older respondents (age 50–59 and age 60+) are the most likely to report frustration or inability to make a decision.

The youngest respondents, report that they are frustrated, but they say that they can make a decision. This is an important fact. It appears that frustration may be an emotional reaction whereas decision may be a simple action.

Mind-Sets in the population based upon how easily a person is frustrated in the search

A key feature of Mind Genomics is the extraction of new-to-the-world mind-sets, based upon how the person thinks with regard to the specific topic. During the past sixty years, consumer researchers have recognized the value of dividing people by patterns, either of WHO they age (geo-demographics), what they DO (behavior), or how they THINK about general topics [17].

The notion that people differ from each other is obvious but it is not clear that one can know exactly WHAT TO SAY to a person when one knows WHO they are, what they DO, or what they BELIEVE. One could make the case, of course, that one knows certain things that one should say, but what are the precise words, the precise communication messages for a person, say in the world of health information? How does one know what to say to a person on the web, or the next person who walks in the door?

It is tempting to believe that the general segmentations based upon previous behavior will indicate what to say. The answer is not clear. Behavioral targeting is all the rage today, as of this writing (August, 2019), but it is not clear that a person who asks for rates about a health service will answer every message. The words must be correct. The sensitivity to the mind of the patient must be tuned. And, most of all, one must ‘know’ what words to do, what actions to take, not so much in the grand world at so-called 20,000 feet, where the detail is lost, but rather ‘on the ground’ in granular detail.

Mind Genomics works in the world of the concrete, the world of daily experience, the world of specific words and phrases. The studies in Mind Genomics are not posed as questions to be answers, but as vignettes to which one reacts. This structure eventuates in the above-demonstrated set of coefficients. Segmentation, in turn, becomes the identification of different and meaningful patterns of coefficients, and therefore ‘mind-sets.’ The ‘mind-set’ is a coherent pattern of coefficients, with each respondent in the study assigned to one of the mind-sets, based upon the pattern of that individual’s coefficients.

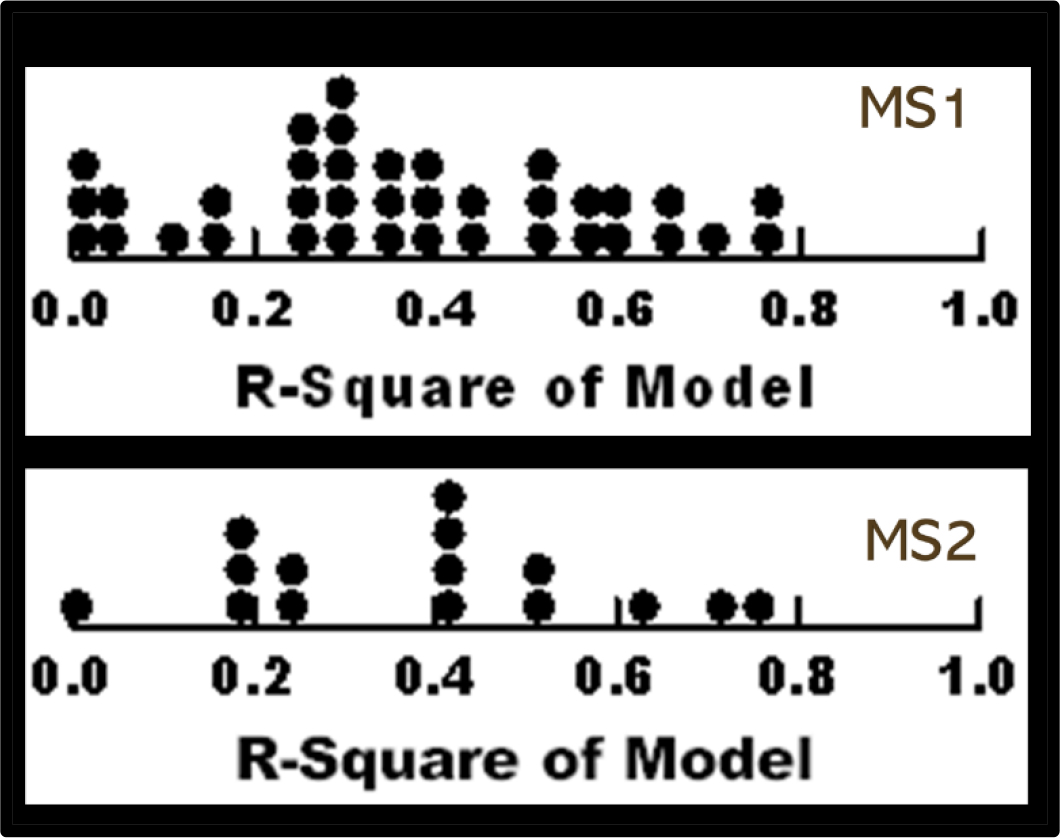

For this study, the discovery of the mind-sets was based upon clustering of individuals using the coefficients from Frustrate YES, i.e., individual patterns of getting frustrated. Frustration is a basic emotion among people, especially those who search for necessary information. The process follows these steps:

- Array the coefficients for Frustrate ME so that each row is a respondent, and each respondent has 16 numbers, one for each coefficient. The additive constant is not used for the cluster analysis.

- Cluster the respondents using K-means clustering [18]. so that individuals close together are clustered together. The measure of distance is (1-Pearson R), with Pearson R taking on the value of +1 when two patterns are identical (distance = 0) and with Pearson R taking on the value of -1 when two patterns are diametrically opposite (distance = 2).

- The objective of clustering and segmentation is to find a meaningful division of respondents, based upon specific criteria. Clustering is a heuristic in exploratory data analysis, not a hard-and-fast system, although the mathematics are stringent and reproducible.

- Compare the two-cluster and three-cluster solution. Choose the solution with the lower size only when it is easy to interpret. For these data, the three-cluster solution was easier to interpret, but interpretation is a subjective matter.

- Three mind-sets emerged from the clustering. The clustering program does not label these, but rather the naming of the mind-is left to the researcher. The typical naming considers the strongest performing elements, and in this study, the additive constant. Table 9 presents the strongest performing elements for each of the three mind-sets.

Table 9. How three emergent mind-sets based on what drives ‘Frustrate YES) respond to the elements in terms of the segmenting criterion, Net Frustrate YES

|

|

Net Frustration (Frustrate YES – basis of the clustering) |

MS1 |

MS2 |

MS3 |

|

Additive constant |

24 |

3 |

35 |

|

|

Mind-Set 1 – Has some latent frustration, but gets really frustrated when search is difficult |

||||

|

C3 |

Information is scattered – frustrates me |

46 |

63 |

3 |

|

C4 |

Information doesn’t seem trustworthy |

25 |

35 |

-3 |

|

Mind-Set 2 – Has very little latent frustration, but easily and strongly frustrated |

||||

|

C3 |

Information is scattered – frustrates me |

46 |

63 |

3 |

|

C4 |

Information doesn’t seem trustworthy |

25 |

35 |

-3 |

|

C1 |

Information is relevant but hard to understand |

13 |

34 |

0 |

|

Mind-Set 3 –A lot of latent frustration, wants search to be simple, direct, give the information, gets frustrated when process is not simple, direct (KISS) |

||||

|

D2 |

Looking for simple way to contact and get answers |

-9 |

-5 |

21 |

|

D3 |

Looking for specific service |

11 |

4 |

20 |

|

D1 |

Looking for rates |

17 |

-11 |

17 |

|

D4 |

Looking for process …how to… |

6 |

1 |

10 |

|

B2 |

Make best decision considering health |

-3 |

8 |

9 |

|

B4 |

Make best decision for my future |

-17 |

-1 |

8 |

|

Elements which do not strongly drive frustrations among the mind-sets |

||||

|

B3 |

Make best decision considering my situation |

-7 |

7 |

1 |

|

A1 |

Current life stage: Transitioning |

8 |

3 |

1 |

|

B1 |

Make best decision |

-12 |

2 |

1 |

|

C2 |

Have to do multiple searches before making a decision |

15 |

17 |

-4 |

|

A3 |

Current disease |

13 |

-3 |

-7 |

|

A2 |

Current disease stage |

-2 |

19 |

-9 |

|

A4 |

Time since diagnosis |

12 |

-1 |

-11 |

Mind-Set 1 – Has some latent frustration, as shown by the modest additive constant, 24. Mind-Set 1 gets really frustrated when the search is difficult. The latent frustration emerges from the relatively high additive constant of 24. The two strongest elements drive a high degree of frustration

Information is scattered – frustrates me

Information doesn’t seem trustworthy

Mind-Set 2 has almost no latent frustration (additive constant = 3), but also easily frustrated, and strongly so. The same two elements drive Mind-Set 2 compared to Mind-Set 1, only far more.

Mind-Sets 1 and 2 may be combined to generate a general mind-set which simply wants easy answers, in general.

Mind-Set 3 is altogether different. Mind-Set 3 exhibits quite strong latent frustration (additive constant = 35, wants search to be simple, direct, give the information, gets frustrated when process is not straightforward. Here are the strongest frustrating elements for Mind-Set 3:

Looking for simple way to contact and get answers

Looking for specific service

Looking for rates

When we apply the mind-sets just discovered for frustration to blockers of decision (Net Decide NO), we find that Mind-Sets 1 and 2 are similar in terms of their propensity not to decide (additive constant 58 and 60) whereas Mind-Set 3 is less hindered (additive constant 42.). Mind-Set 3 is more of a perfectionist, with B1 (make best decision) a source of failure to make a decision. Table 10 shows these results.

Table 10. How three emergent mind-sets based on what drives ‘Frustrate ME) respond to the elements hindering a decision (Net Decide NO)

|

|

NET Decide NO |

MS1 |

MS2 |

MS3 |

|

Additive constant |

58 |

60 |

42 |

|

|

C4 |

Information doesn’t seem trustworthy |

20 |

12 |

16 |

|

C1 |

Information is relevant but hard to understand |

17 |

12 |

22 |

|

C3 |

Information is scattered – frustrates me |

-5 |

14 |

19 |

|

B1 |

Make best decision |

-9 |

1 |

9 |

|

C2 |

Have to do multiple searches before making a decision |

-8 |

3 |

7 |

|

B3 |

Make best decision considering my situation |

-1 |

-3 |

4 |

|

D1 |

Looking for rates |

-5 |

-3 |

2 |

|

A3 |

Current disease |

-9 |

-14 |

2 |

|

D2 |

Looking for simple way to contact and get services |

-4 |

-6 |

1 |

|

D3 |

Looking for a specific service |

-7 |

-10 |

1 |

|

B2 |

Make best decision considering health |

-10 |

3 |

0 |

|

A4 |

Time since diagnosis |

1 |

-25 |

0 |

|

D4 |

Looking for process … how to… |

6 |

-3 |

-2 |

|

B4 |

Make best decision for my future |

6 |

-4 |

-2 |

|

A1 |

Current life stage: transitioning |

-4 |

-22 |

-3 |

|

A2 |

Current disease stage |

-6 |

-14 |

-6 |

When we move to response time, we find dramatic differences.

Mind-Set 2, which showed the least latent frustration (additive constant = 3), also shows the longest response times. That is, Mind-Set 2 reads everything closely.

Mind-Sets 1 and 3 both show a high level of latent frustration (additive constant = 24 for Mind-Set 1 and additive constant = 35 for Mind-Set 3.). These two mind-sets show shorter response times, consistent with their latent frustration. Mond-Set 3 appears to consider the information in a slightly deeper way than does Mind-Set 1, because its response times are slightly longer.

Finding these mind-sets in the population (The Personal Viewpoint Identifier)

A continuing result from Mind Genomics studies is mind-sets distribute in the population in ways that are unexpected. Everyday experience with the different services suggests that there are different mind-sets or preference patterns for various services. The value of a conversation with a health provider (boot, chat or live) is obtained through the personalization using tailored messaging.

Table 12 suggests that who a person IS does not correspond to the mind set to which the person belongs.

Table 11. How three emergent mind-sets based on what drives ‘Frustrate YES) respond to the elements in terms of Response Time

|

|

Response Time – To process information |

MS1 |

MS2 |

MS3 |

|

D3 |

Looking for specific services |

2.0 |

2.0 |

1.3 |

|

B3 |

Make best decision considering my situation |

1.9 |

2.5 |

1.3 |

|

B4 |

Make best decision for my future |

1.7 |

2.3 |

1.3 |

|

D2 |

Looking for simple way to contact and get answers |

1.3 |

2.2 |

1.3 |

|

B2 |

Make best decision considering health |

1.2 |

2.2 |

1.4 |

|

D4 |

Looking for process… how to … |

1.9 |

2.1 |

1.8 |

|

D1 |

Looking for: specific rates |

1.4 |

2.0 |

1.5 |

|

B1 |

Make best decision |

1.2 |

2.0 |

1.8 |

|

C2 |

Have to do multiple searches before making a decision |

1.7 |

1.7 |

1.6 |

|

A4 |

Time since diagnosis |

0.4 |

1.7 |

1.8 |

|

C4 |

Information doesn’t seem trustworthy |

1.2 |

1.6 |

1.1 |

|

A3 |

Current disease |

0.4 |

1.6 |

0.8 |

|

C1 |

Information is relevant but hard to understand |

1.1 |

1.5 |

1.9 |

|

C3 |

Information is scattered – frustrates me |

1.1 |

1.5 |

1.2 |

|

A2 |

Current life stage: transitioning |

0.6 |

1.3 |

1.2 |

|

A1 |

Current disease stage |

0.8 |

1.2 |

1.2 |

Table 12. Distribution of mind-sets across geo-demographics and disease stage

|

Mind-Set 1 – Has some latent frustration, but gets really frustrated when search is difficult |

Mind-Set 2 – Has very little latent frustration, but easily and strongly frustrated |

Mind-Set 3 –A lot of latent frustration, wants search to be simple, direct, give the information, gets frustrated when process is not simple, direct |

Total |

|

|

Total |

14 |

19 |

17 |

50 |

|

Gender |

||||

|

Male |

10 |

6 |

10 |

26 |

|

Female |

4 |

13 |

7 |

24 |

|

Age |

||||

|

Age 23–29 |

1 |

3 |

3 |

7 |

|

Age 30–49 |

10 |

6 |

6 |

22 |

|

Age 50–59 |

2 |

6 |

4 |

12 |

|

Age 60 Plus |

1 |

4 |

4 |

9 |

|

Life Stage |

||||

|

Graduate College |

3 |

0 |

3 |

6 |

|

Family |

8 |

10 |

4 |

22 |

|

Retired |

1 |

2 |

4 |

7 |

|

No Answer |

2 |

7 |

6 |

15 |

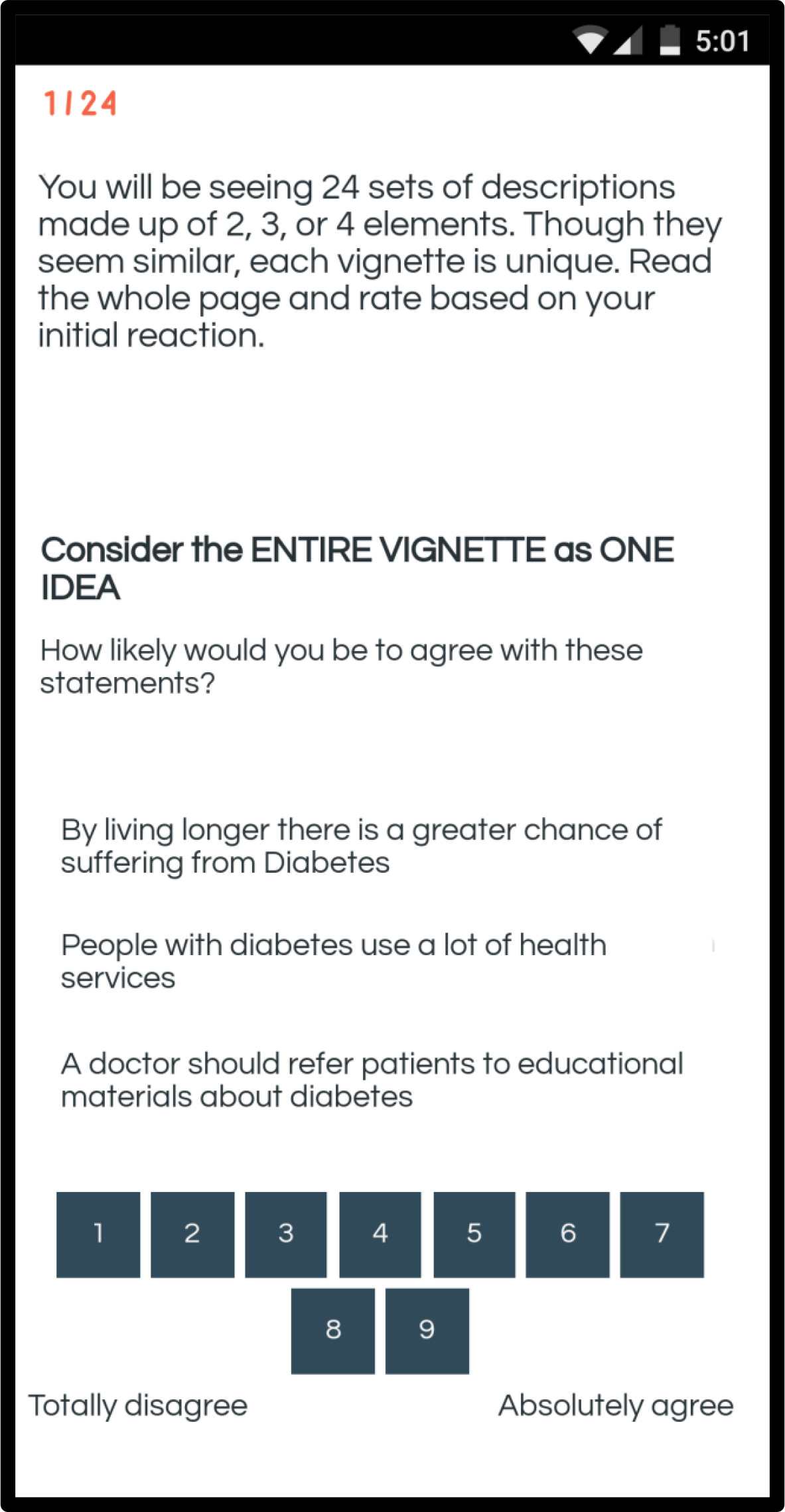

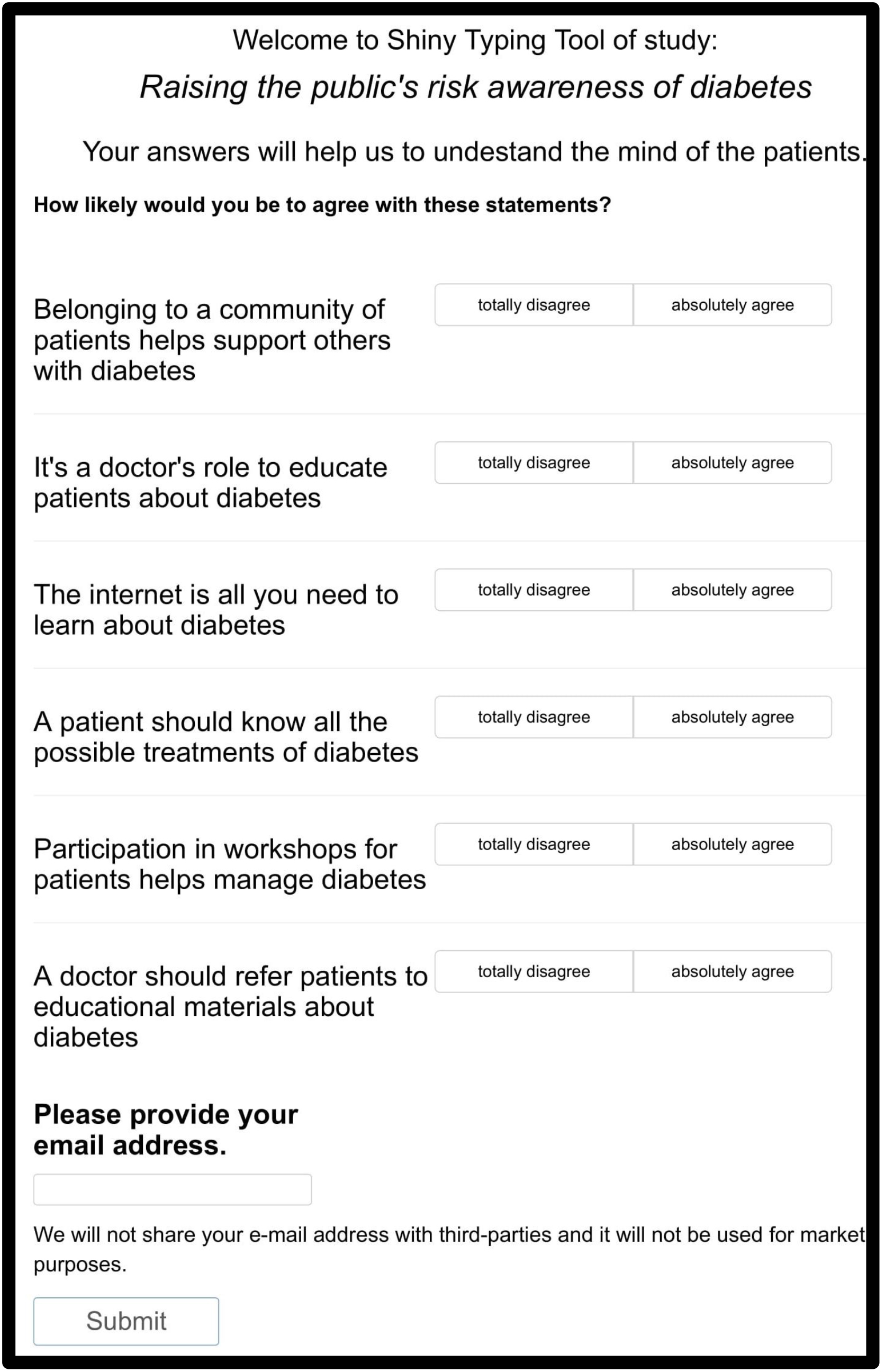

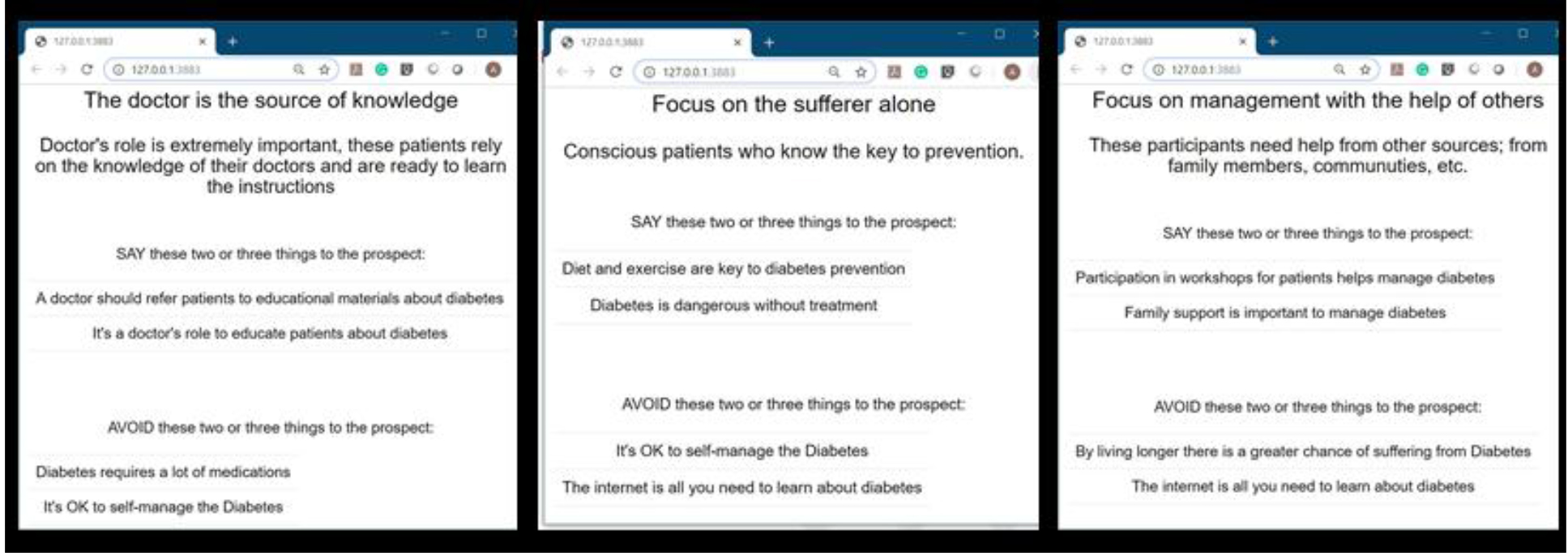

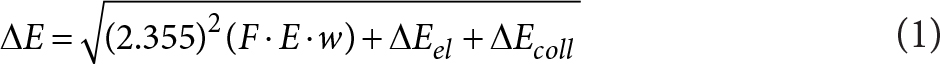

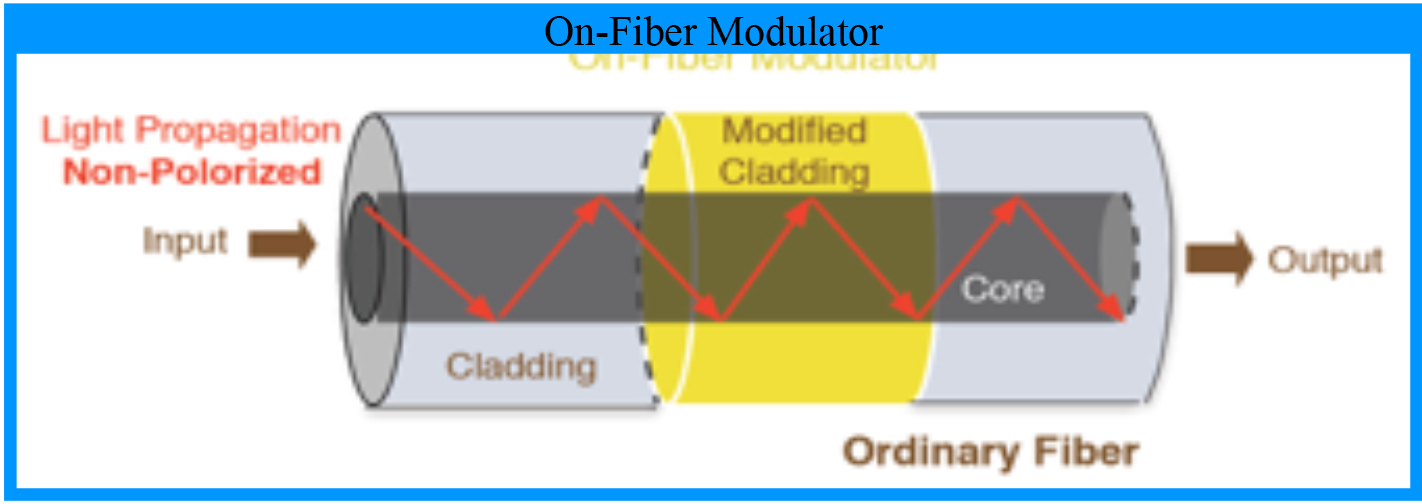

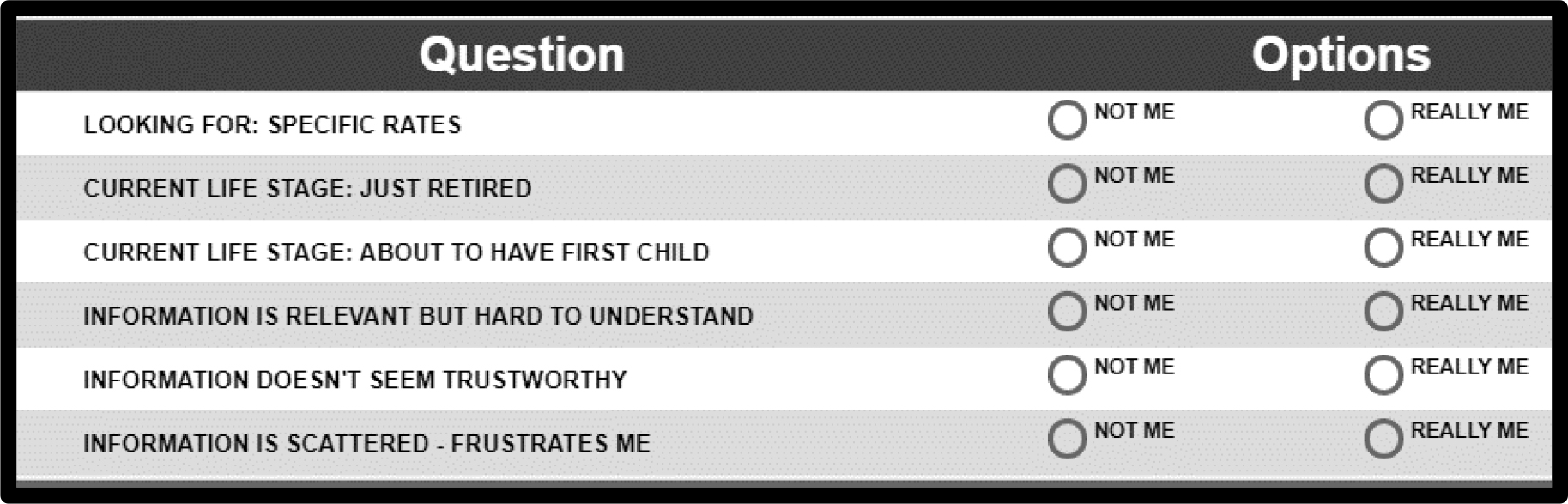

During the past several years authors Gere and Moskowitz have developed a set of simple algorithms based upon the coefficients of corresponding elements emerging from the clustering program. Either all or just a limited number of the elements need to be used, but at least eight elements are required. The algorithm uses a Monte-Carlo method to identify those elements which best discriminate between two mind-sets or across three mind-sets, when ‘noise’ is added to the data. The algorithm has been labelled the PVI, the Personal Viewpoint Identifier. The PVI works with individual respondents, identifying their mind-set, and where relevant, returning information to them, either information which is informative, prescriptive, or both. Figure 2 shows an example of the PVI. The PVI returns with the mind-set of the respondent and may provide the respondent or the health maintenance organization with additional information in terms of feedback. The PVI takes approximately 30 seconds to administer.

Figure 2.

The PVI for the study, showing the questions and the two possible answers to each question

Discussion and Conclusions

In a world where individuals are increasing empowered to discover information previously known only to a cadre of specialists brings with it the problem of frustration and indecision. The world of UX and CX, user experience and patient experience, respectively, have developed to address this situation. These efforts did not begin with the world of the Internet, but rather were begun much earlier by psychologists studying the interaction of people and machines, the field of human factors.

The issue of user experience is magnified when we move beyond games and shopping, with momentary risk, to the search for health information on the internet. Looking at the response times shows us the amount of time that respondents take to process the information. The response times are quite long compared to other topics.

The importance of this study stems from the use of Mind Genomics as an easy-to-implement first stage in understanding the user experience. Rather than building out the system and then first testing the system for usability, the Mind Genomics approach can suggest different aspects of what frustrates a person, what prevents a decision and the nature of the person as a user. Mind Genomics thus gives voice to the individual as well, not as a purely linked part of the user experience, but as another independent dimension, based upon the proclivities of the user. As such, Mind Genomics carries forth the vision of Goldsmith [19], who two decades ago recognized the coming tidal wave of innovation. Mind Genomics is just one of the contributors to what promises to be an increasing tidal wave of innovation as the opportunities and problems in managed health care become increasingly obvious with our aging population.

Acknowledgement

Attila Gere thanks the support of Premium Postdoctoral Research Program of the Hungarian Academy of Sciences.

References

- Fein R (1986) Medical care, medical costs: The search for a health insurance policy. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press.

- Fox S (2011) The social life of health information. DC: Pew Internet & American Life Project 1–33.

- Arora NK, Hesse BW, Rimer BK, Viswanath K,Clayman ML, et al.(2008) Frustrated and confused: the American public rates its cancer-related information-seeking experiences. Journal of general internal medicine 23: 223–228.

- Kim K, Kwon N (2010) Profile of e-patients: analysis of their cancer information-seeking from a national survey. Journal of health communication 15: 712–733.

- Viswanath K (2005) the communications revolution and cancer control. Nature reviews cancer 5: 828.

- Janeice-Morgan A, Janeice-Mogan M, Trauth M (2013) Socio-economic influences on health information searching in the USA: the case of diabetes. Information Technology & People 26: 324–346.

- Ayers SL, Kronenfeld JJ, (2007) chronic illness and health-seeking information on the Internet. Health 11: 327–347.

- Macinnes N,HaglundBJ (2011) Readability of online health information: implications for health literacy. Informatics for health and social care 6: 173–89.

- Cebul RD, Rebitzer JB, Taylor LJ, Votruba ME(2011) Unhealthy insurance markets: Search frictions and the cost and quality of health insurance. American Economic Review 101: 1842–1871.

- Box GE, Hunter WG, Hunter JS (1978) Statistics for experimenters. New York, John Wiley.

- Green PE, Rao VR (1971) conjoint measurement for quantifying judgmental data. Journal of marketing research 8: 355–363.

- Green PE, Srinivasan V (1990) conjoint analysis in marketing: new developments with implications for research and practice. The journal of marketing 54: 3–19.

- Moskowitz HR (2012) ‘Mind genomics’: The experimental inductive science of the ordinary, and its application to aspects of food and feeding. Physiology & Behavior107: 606–613.

- Gofman A, MoskowitzH (2010) Isomorphic permuted experimental designs and their application in conjoint analysis. Journal of Sensory Studies 25: 127–145.

- Moskowitz HR, Gofman A, Beckley J, Ashman H (2006) Founding a new science: Mind genomics. Journal of sensory studies 21: 266–307.

- Moskowitz HR, Gofman A (2007) Selling blue elephants: How to make great products that people want before they even know they want them. Pearson Education.

- Wells WD (2011) Life Style and Psychographics, Chapter 13: Life Style and Psychographics: Definitions, Uses, and Problems. Marketing Classics Press.

- Dubes R, Jain AK (1980) Clustering methodologies in exploratory data analysis. Advances in Computers 19: 113–238.

- Goldsmith J (2000) The Internet and managed care: A new wave of innovation. Health Affairs 19: 42–56.