Abstract

Respondents evaluated vignettes comprising a combination of simple phrases, designed to describe ordinary, common experiences that may be upsetting for individuals who have undergone adverse childhood events (ACE) and childhood trauma. The vignettes were systematic combinations of 2-4 stand-alone answers to four questions, each question generating four answers (aka messages, elements). The four questions generated phrases describing reactions to different types of childhood trauma, namely history of childhood sexual abuse, exposure to a caretaker or other adult with substance abuse, living in a lower socioeconomic status, and exposure to crime and gun violence, respectively. Each respondent rated a unique set of 24 vignettes constructed according to an underlying experimental design, with the 24 vignettes comprising an experimental design ready for regression modeling. The respondents rated each vignette on a five-point scale, assessing their immediate emotional reaction if they were to experience the events in the vignette and the likelihood that experiencing the events would evoke negative memories from the past. In addition to the 24 vignettes, respondents answered 8 yes/no questions regarding experience with Adverse Childhood Events (ACE). Regression analysis linked the elements in the vignettes to ratings. Three mind-sets emerged, defined by the pattern of coefficients: a strong response to emergency precautions, safety barriers, and depictions of substance abuse; a strong response to financial hardship or perceived hardship; and a strong response to startling sensory input and sexual content, respectively, The regression coefficients showed varied by individuals who answer “yes” to different ACE questions.. By employing AI within the framework of Mind Genomics, this study reveals relations between the what a person suffers as a child and how the person relates to emotionally-sensitive messages, evaluated years later. The Mind Genomics approach coupled with AI creates a new tool to understand the nuances of emotional responses associated with distinct types of traumas.

How Mind Genomics works

Mind Genomics works by presenting respondents with vignettes. A vignette is a combination of messages (elements, answers to questions), with the elements being ‘stand-alone’ phrases. An underlying experimental design prescribes the elements appearing in each vignette. The design used here is a so-called ‘permuted design.’ Each respondent evaluates the same design of 24 vignettes, but the actual combinations differ from respondent to respondent. Mind Genomics provides a way to obtain information from people without the people ‘gaming the system,’ and indeed without any prior knowledge being necessary.

There are two features of Mind Genomics which make it valid and reliable:

- Mind Genomics works at the granular, concrete level, the everyday, to generate both the test elements: The elements paint ‘word pictures.’ The test stimuli become short word pictures, albeit not connected but rather seemingly put together at random. The combination is more realistic, more similar to the world of the everyday, with the different aspects of the daily word present together in no clear pattern. Yet people are able to navigate through the ordinary world. In the same fashion, the vignettes comprise these stand-alone phrases. After a moment of shock, the respondent usually relaxes, and simply ‘grazes; through the information in what seems to be a relaxed fashion. Thus, Mind Genomics measures responses to ‘real information, viz., particulars such as descriptions of events as opposed to general ideas. Starting the evaluations from a granular experience differs from conventional scales of today in that it does not only restrict the responses to an intellectualized version of a response. Most researchers find themselves restricted to working with and considering only generalized ideas rather than specifics, but with Mind Genomics, the survey respondent is the one who more easily “abstracts” the general ideas as they are based on their answers to the particulars. by this method.

- Mind Genomics makes it impossible for people to ‘game’ the system. People do not necessarily tell the truth, either by deliberately lying, or unconsciously misrepresenting themselves to be more agreeable or more correct as they interact with the interviewer. It remains the nature of today’s science to rely on scales that can be easily ‘gamed [1]. Due to human nature and the inherent drive to be positively perceived, the validity of a scale cannot be easily assured using conventional methods.

The history of Mind Genomics traces back to three sources, the combination of which ended up synthesizing this new discipline. The history traces back to experimental psychology, particularly in the realm of psychophysics; statistical specifically in experimental design; and consumer research, with a focus on discerning and delineating patterns in decision-making processes. The ‘experiment’ in Mind Genomics presents respondents with vignettes, combinations of succinct, stand-alone phrases which create a scenario. The respondent reads the vignettes, one at a time, and then rates the vignettes. Afterwards, the underlying experimental design enables the deconstruction of the responses into the contribution of the individual elements. In order to make the analysis simple and the results straightforward for a manager to understand, the Mind Genomics program transforms the ratings into new binary variables, taking on the value of 0 or 100. The transformations are explained below. Mind Genomics endeavors to uncover interpretable patterns within the construct, such as trauma, doing so with simple stimuli, but ‘cognitively meaningful’ ones. In the Mind Genomics study, respondents ultimately generate cohesive patterns of data, as illustrated in the results below. It is crucial to underscore that throughout the study, respondents are intentionally guided to abstain from delving into the messages within the various combinations in an attentive way, pondering the message. Instead, the subconscious assumes control, steering respondents towards responses that may initially seem arbitrary. However, it is important to recognize that these responses are far from random.

Introduction to the Study

The science behind Mind Genomics allows researchers to explore the human experience in the context of a wide array of topics. Among these factors, childhood trauma stands out as a potent force shaping an individual’s perception and interaction with the world [2]. Childhood trauma, defined as adverse experiences occurring before the age of 18, encompasses a range of events such as abuse, neglect, and household dysfunction. Its profound impact on psychological development and overall well-being has been extensively documented in psychological and medical literature [3,4]. One of the most significant consequences of childhood trauma is the development of complex post-traumatic stress disorder (cPTSD) and hypervigilance [5]. These conditions manifest as heightened sensitivity to potential threats, pervasive feelings of fear and anxiety, and difficulty regulating emotions. Individuals who have experienced childhood trauma often navigate daily experiences through a lens colored by these psychological scars, which significantly alters their perceptions and reactions compared to neurotypical individuals. Whereas the neurotypical individual may take for granted the ability to engage with daily experiences without undue distress, those who have experienced childhood trauma face unique challenges. Simple tasks such as witnessing conflict, engaging in social activities, and managing emotions may turn into formidable obstacles. The omnipresent threat of triggering memories or emotions associated with past trauma can cast a shadow over even the most mundane activities, leading to avoidance behaviors and social isolation. The power behind the use of AI in the context of Mind Genomics allows researchers to expand this existing knowledge about psychology and medicine.. By applying Mind Genomics techniques to the study of reactions to daily experiences among individuals who experienced childhood trauma, researchers can identify differences in cognitive processing and information integration. This approach allows for a more comprehensive understanding of how past trauma influences the interpretation and response to everyday stimuli.

Setting up the Mind Genomics study on trauma

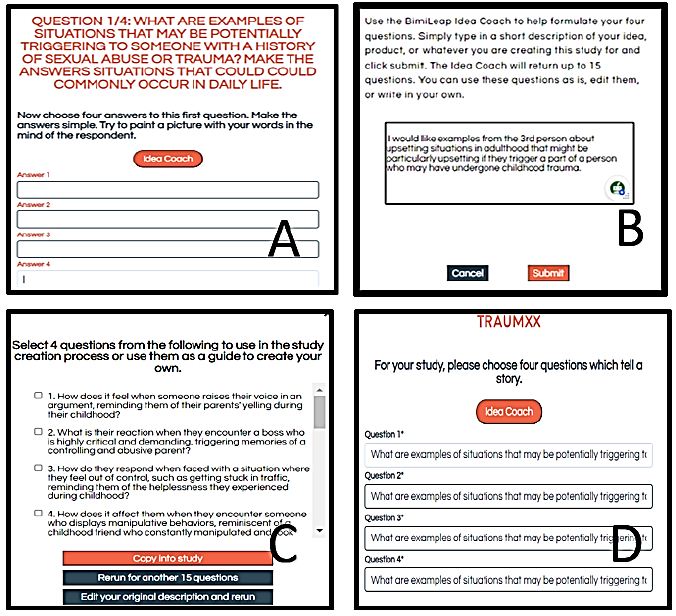

The raw material for vignettes – questions and answers: The first step registers the study, gives it a name, and proceeds to the heart of the approach, namely creating four questions, and then for each question creating four answers. The answers themselves must be simple, stand-alone phrases which paint a word picture. These answers, called ‘elements’ will end up being combined with each other in vignettes. Figure 1, Panel A shows the schematic request for the four questions. It is in this first encounter with the requirement to think of four questions than many researchers encounter difficulties. While discussing the etiology of trauma is manageable, crystallizing these etiologies proves challenging when the task is to create standard questions with answers which reflect mundane life experiences triggering trauma. Producing the questions separates the diagnosticians/therapists from statistically oriented researchers. Diagnosticians and therapists aim for a comprehensive understanding of the patient, whereas statisticians prefer straightforward numerical data for tallying questions. Consequently, the task of creating a list of questions that tells a coherent story becomes arduous. The answer to the dilemma is AI, in the form of Idea Coach, which embodies SCAS (Socrates as a Service). SCAS was created to make the process less arduous, and in some cases make the process a learning experience. Figure 1, Panel B introduces the Idea Coach, embodying SCAS. In this stage, the user articulates the issue by writing the ‘squib,’ a colloquial term for the text typed into the box. The squib may undergo multiple edits to refine the type of question desired. Panel C showcases some of the AI’s output. Finally, Panel D displays the four questions selected after user editing, preparing them for answers. Users can also rerun the Idea Coach, doing so in an iterative fashion, editing the squib when desired to see what emerges. Within the program (www.bimileap) the SCAS system embedded in Idea Coach requires about 10-15 seconds per iteration. Even with squib editing, users can generate 10 pages of 15 questions in about 8-10 minutes. The resulting ‘question book,’ combined with AI summarization, proves to be a valuable resource, as further illustrated below.

Figure 1: The first part of the Mind Genomics study, showing the four panels to help the user select questions.

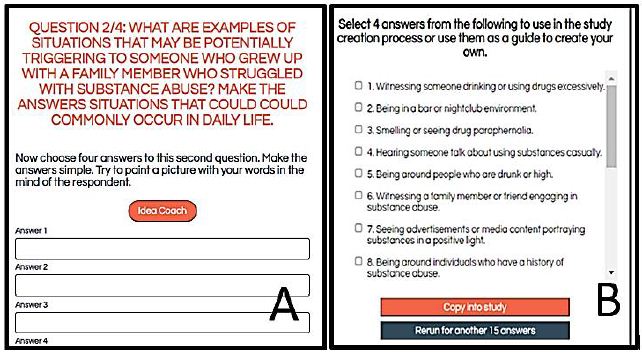

Figure 2 the second phrase, the selection of answers to each of the four questions. Panel A shows the request for four answers. The user can simply press the Idea Coach button. The ‘squib’ is the question selected by the user. Panel B shows 8 of the 15 answers emerging with 10-15 seconds. Once again the user can iterate to educate themself by looking at the different answers to the question, or the user can actually edit a particular question.

Figure 2: The Mind Genomics Template showcasing the question and the AI-generated possible answers to the question that the user can select. Panel A shows the template for the four answers for Question #2. The question comprises the full set of modifications to the prompts, to create answers which are in the proper form. Panel B shows eight out of 15 answers for this iteration.

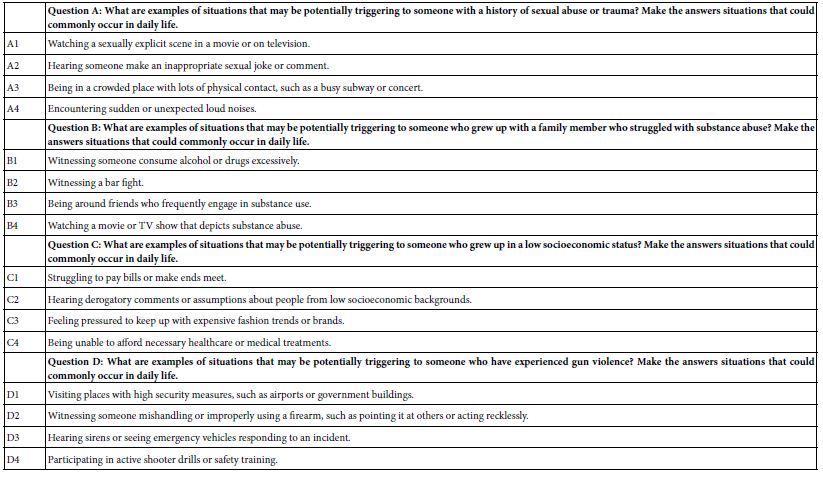

In summary, the Mind Genomics study entails a structured process to generate questions and answers, incorporating AI assistance (SCAS) and iterative refinement. The outcome is for a comprehensive exploration of complex topics, such as the effects of trauma on daily responses to various stimuli. This phase often becomes a critical juncture where researchers may encounter challenges, finding it easier to discuss cases of trauma but challenging to crystallize the discussion into standard questions. Those focused on diagnostics and therapy seek a closer, deeper understanding of the patient, whereas those concentrating on statistical analysis prefer simple numbers to tally on questions. Both will end up being satisfied with the combination of AI, creative thinking, and quantitative analysis using qualitative inputs.The final set of questions and answers appear in Table 1. These crafted inquiries and responses embody the collaborative effort to mold the content and structure of the answers. The overarching goal is to create a collection of meaningful standalone phrases (elements) which paint word pictures about the topic, and which can be combined together in small vignettes comprising 2-4 elements.

Table 1: The final set of questions and answers emerging from the collaboration of the user and SCAS (the AI embedded in the Idea Coach).

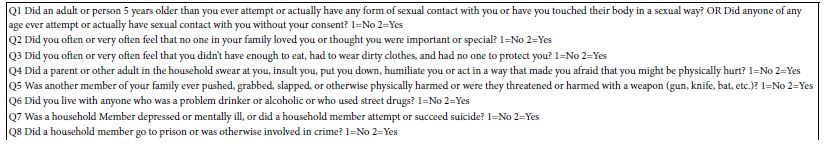

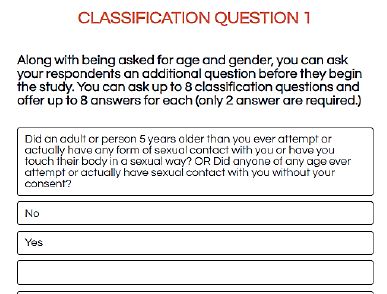

The self-profiling classification question: The setup process advances by formulating classification questions. The classification questions are simple questions which provide additional information about who the respondent IS, what the respondent has EXPERIENCED, etc. In this study, eight questions based on the original ten Adverse Childhood Events questions were asked as part of the study introduction to each respondent. Adverse Childhood Experiences (ACEs) and the ACE survey are integral components of research aimed at understanding the long-term impacts of childhood trauma on health and well-being. The concept of ACEs originated from a groundbreaking study conducted by the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) in collaboration with Kaiser Permanente’s Health Appraisal Clinic in San Diego, California, in 1997.The ACE study surveyed over 17,000 adult respondents, collecting information about their childhood experiences of abuse, neglect, and household dysfunction. The study identified ten specific types of adverse experiences [3]:

- Physical abuse

- Emotional abuse

- Sexual abuse

- Physical neglect

- Emotional neglect

- Household substance abuse

- Household mental illness

- Parental separation or divorce

- Domestic violence

- Incarcerated household member

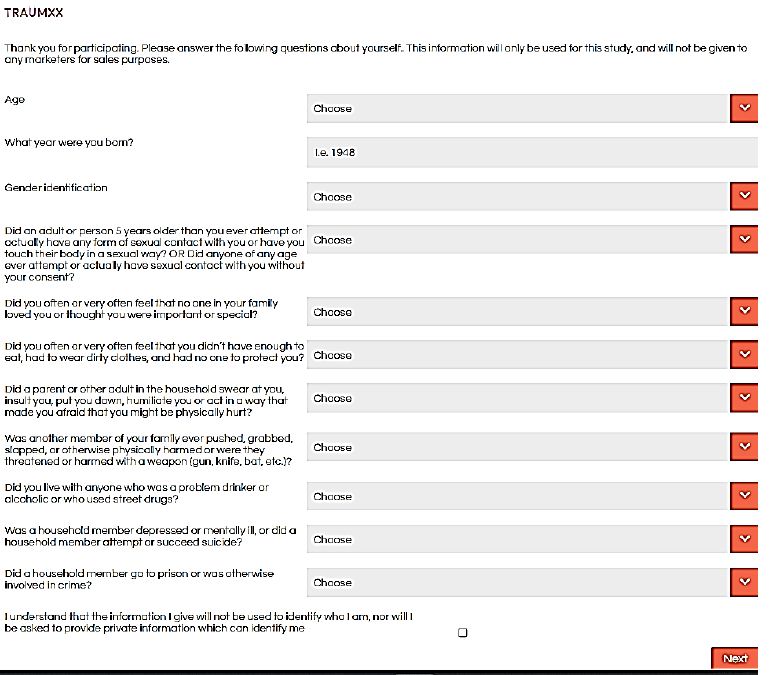

Respondents were asked to indicate whether they experienced any of these events during their childhood and adolescence. The study revealed a significant association between ACEs and a myriad of negative outcomes across the lifespan, including physical and mental health issues, substance abuse, risky behaviors, and socioeconomic challenges. For the purposes of Mind Genomics, the original ten questions were reduced to eight (Table 2) questions as seen in Table 2. Figure 3 shows the templated format in the Mind Genomics set-up for the ACE question.

Table 2: The eight ACE questions presented to respondents in the self-profiling classification part of the Mind Genomics interview, BEFORE the evaluation of the 24 test vignettes.

Figure 3: How the ACE question is inserted into the Mind Genomics study at the time of set-up.

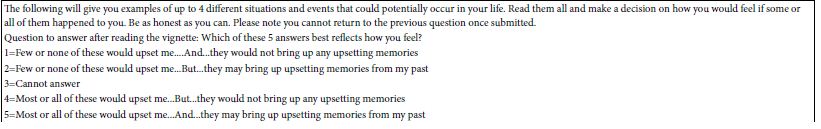

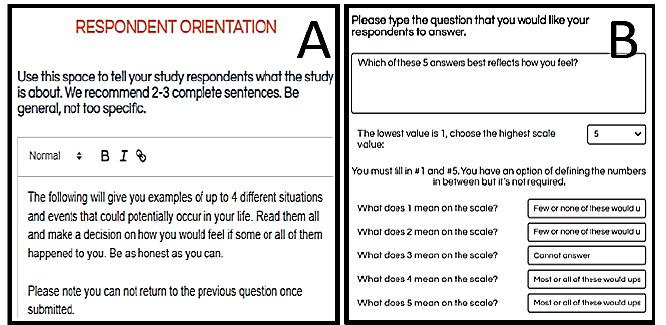

The final phase of the setup process involves crafting the introduction to the study and then establishing the scale to be utilized. Table 3 shows the introduction and the rating scale in table form. Figure 4, Panel A displays the introduction presented to the respondent. Typically, brief and direct, this introduction focuses the respondent’s attention on the task. Recognizing the increased shortening of attention spans, the introduction is written in an abbreviated way. In some cases, however, such as legal cases involving childhood trauma, the introduction to a Mind Genomics might warrant a more detailed introduction to ensure that respondents are informed of the case’s background. Panel B illustrates the five-point rating scale, customizable by the user to align with the project objectives. In this study, the rating scale captures two dimensions. The first dimension of the scale assesses the immediate feeling of being upset if one or more of the events in the vignette were to occur. The second dimension of the scale gauges the perceived ability of the vignette to evoke a distressing memory.

Table 3: The introduction to the respondent and the text of the five answers to the question

Figure 4: Respondent orientation. Panel A shows the set-up screen for the orientation that the respondent reads. Panel B shows the set-up screen for the rating scale that the respondent will use to rate each vignette.

The Respondent Experience

The respondent experience begins with the completion of a questionnaire which asks them demographic questions followed by the 8 questions about Adverse Childhood Event (Figure 5). The respondent’s experience was simplified by a pull-down questionnaire, with each tab had to be individually pulled down.

Figure 5: The pull-down menu for the self-profiling classification questionnaire

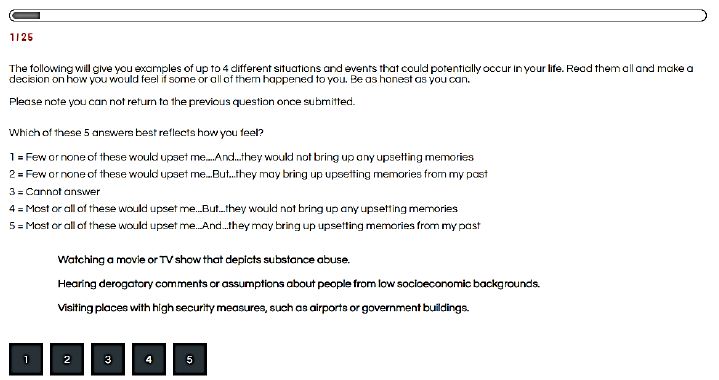

After the self-profiling classification, the Mind Genomics program initiates the presentation of vignettes to respondents. Figure 6 shows an example, the top presenting a concise introduction to the study at the top, middle showing the rating, and the bottom showing both the vignette presented as a set of lines (two to four elements shown in three successive lines), followed by the rating scale. This format enables respondents to ‘graze’ through the information, avoiding the fatigue that could result from reading 24 dense paragraphs, each consisting of two to four sentences with connectives.

Figure 6: Example of a vignette

The vignettes were developed with the following properties.

- Each respondent assessed a total of 24 vignettes, the 24 vignettes comprising a complete experimental design.

- The 24 vignettes for each respondent each comprised a minimum of two elements and a maximum of four.

- Each vignette contained at most one answer (referred to as ‘element’) from a specific category, ensuring that no vignette presented conflicting information of the same type.

- Every element appeared five times among the 24 vignettes and was absent 19 times,.

- Each question or category contributed to 20 out of the 24 vignettes.

- Each respondent evaluated unique vignettes, a distinctive feature of Mind Genomics studies. The creation of the different sets of vignettes means that the research covered a great deal of the design pace, freeing the user from having to select the ‘most promising’ elements ahead of the research. This approach, called the permutated design [6] allows the researcher to use the approach at any stage of the research.

- Every respondent assessed a precisely crafted set of 24 vignettes, with all 16 elements being statistically independent of each other, and capable of independent analysis, particularly OLS (ordinary least squares) regression analysis, also known as curve fitting. This approach enhances the statistical significance of each respondent’s contribution to the study.

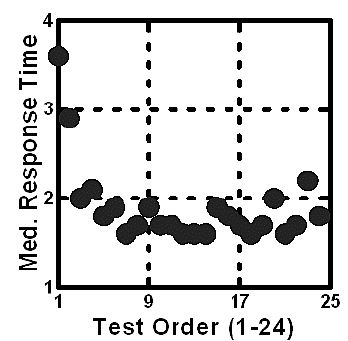

Field Specifics and Data Preparation

As demonstrated in Figures 1-6, the system has transitioned into a do-it-yourself (DIY) framework. Within this DIY paradigm, user engagement extends to recruiting respondents through an online panel aggregator equipped with a built-in API. The Mind Genomics platform empowers users to define the target population based on criteria such as country and age, which is then incorporated into the API. Users incur a nominal recruitment fee, gaining access to a pool of online volunteers facilitated by the provider, Luc.id Inc., boasting access to hundreds of millions of volunteer panelists worldwide. In the context of this study, test respondents were invited based on their prior agreement to participate in studies, accruing points towards rewards for their participation. The user’s role involved specifying the details, completing the payment through a credit card, and triggering email invitations to the target respondents. This streamlined process demonstrated efficiency, with the study involving 101 respondents, requiring less than four hours for completion. From the perspective of the study respondent, the actual duration was approximately 3-4 minutes. Respondents initiated the study by clicking on the embedded link, progressing through a brief ‘hello’ page, a self-profiling classification (Figure 5), and an introduction to the study itself. Subsequently, respondents evaluated the set of 24 unique vignettes organized according to the aforementioned experimental design (Figure 6). Figure 7 shows the median response time by test order, indicating that once respondents grasped the task, the median response time dropped to less than two seconds. The ability to swiftly inspect a vignette and assign a rating meant that the effort to read the vignettes amounted to 2-3 minutes. As noted above, in this type of study respondents adopt a ‘grazing’ approach, akin to superficially inspecting their surroundings, aligning with the Mind Genomics objective to capture data from individuals engaged in casual observation and rating. This approach aims to derive patterns not from deliberate, conscious efforts but from the more typical automatic and almost instinctive responses. Psychologist Daniel Kahneman’s conceptualization of rapid evaluation as ‘System 1,’ distinct from the considered and slower ‘System 2,’ aligns with the behavioral outcomes shaped by Mind Genomics [7].

Figure 7: How the median response time to the vignette changes across the 24 test positions, from start (test order 1) to end (test order 24).

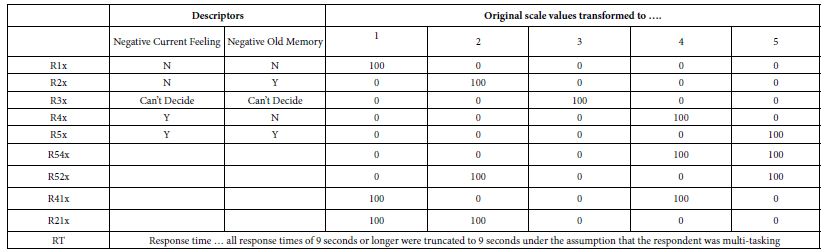

The respondent provided a rating for each vignette on a five-point scale, constructed to encompass two dimensions: the immediate negative feeling upon imaging one or more elements in the vignette were to happen to them and/or the sense of the vignette potentially evoking a memory of a negative feeling. To extract meaningful information from the scale for statistical analysis, it is necessary to create new ‘binary dependent variables’ through simple transformations. These transformations yield variables suitable for OLS (ordinary least-squares) regression, allowing the researcher to uncover the relation between the presence/absence of the element and the respondent’s ratings. Table 4 shows the transformations. After the transformations, a prophylactic step was taken, adding a vanishingly small random number (<10-5) to every newly created binary scale value.. This addition ensured a slight variability in each binary dependent variable, a requisite for the regression analysis to function effectively and prevent potential ‘crashes’ due to the lack of variability in the dependent variable.

Table 4: The transformations

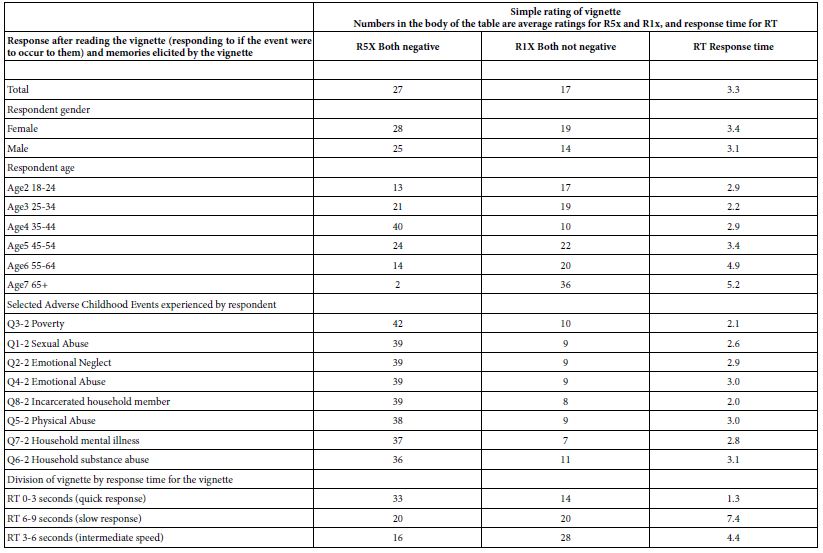

Initial Analyses – Do the Averages of the Binary Variables Different Across Key Subgroups?

The initial analysis examines the average of each newly created binary variable, first for the total panel, and then for the key groups defined by the self-profiling classifications. Three new subgroups were created, based upon the speed of rating the vignette (quick, intermediate, slow). The Mind Genomics system produce a great deal of data, especially with the many newly created binary variables, such as R1x to R5x, etc. To make the analysis more tractable, we consider only two newly created binary variables, R5x (most negative response to the vignette) and R1x (least negative response to the vignette), along with response time. Table 5 presents the average ratings. Particularly noteworthy is the inverted U pattern for R5x concerning respondent age, with the highest R5x occurring in the age group of 35-44. Additionally, respondents who answered quickly exhibited a notably high value for R5x. This finding means quite simply that when the respondent finds the vignette stressful, the respondent is likely to react more quickly to the vignette.

Table 5: Average ratings of R5x, R1X and response time by key groups

Relating the Presence/Absence of the Elements to R5x (Strongest Negative Response to a Vignette)

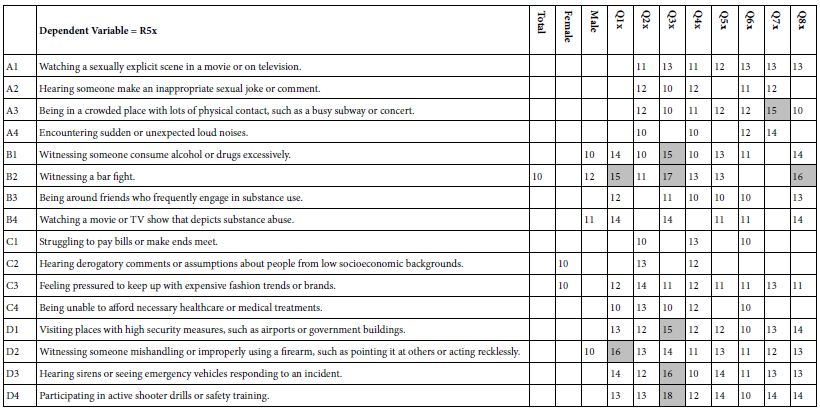

The next level of analysis is to link together the assignment of the most strongly negative response (R5x) to the 16 elements appearing in the vignettes. OLS regression will uncover the pattern. The equation estimated by OLS regression uses all the relevant data from the respondents in the defined group. The equation is expressed as R5x = k1A1 + k2A2.. k16D4. These coefficients appear in Table 6 as 16 rows, with each column corresponding to a key subgroup. The coefficient shows the link between the presence of the element as the average value of R5x. We look for high linkages, viz., a coefficient of 15 or higher. Table 6 shows elements with strong linkages of coefficients 15 or higher. These are all shaded. Table 6 It also shows coefficients greater than 10-14, meaning relevant elements, but not strong drivers of R5x. Empty cells correspond to coefficients less than 10. With large numbers of coefficients to be displayed it is often more productive to eliminate low values for the coefficients, making it easier to discover the patterns, and see elements with strong linkages. Table 6 shows some strong elements, but the pattern is difficult to discern. Most groups show very few coefficients above 10 (viz., Total Panel, males, females), which can make those elements which show a coefficient of 15 or higher stand out more amongst the total elements. What is also interesting is how certain traumatic experiences had more significant elements. Individuals who reported economic disadvantages had five strong performing elements, whereas Childhood Sexual Abuse showed only two strong performing elements. Respondents who had a caretaker or exposure to mental illness or suicidality and subjects who had a caretaker or exposure to someone who was in jail or involved in criminal activity showed only one strongly performing element. Only one element,, witnessing a bar fight, turned out to be a strong performer for more than one group of traumatic events. This element was a strong performer for three groups, those reporting childhood sexual abuse, those reporting poverty, and those reporting having an incarcerated household member.

Table 6: How the elements ‘drive’ R5x by Total panel and by key subgroups. Note: F. Female, M. Male, Q1x. Sexual Abuse, Q2x. Emotional Neglect, Q3x. Poverty, Q4x. Emotional Abuse, Q5x. Physical Abuse, Q6x. Household Substance Abuse, Q7x. Household Mental Illness, Q8x. Incarcerated Household Member.

Mind-Sets Emerging from Clustering the Respondents based on R5x

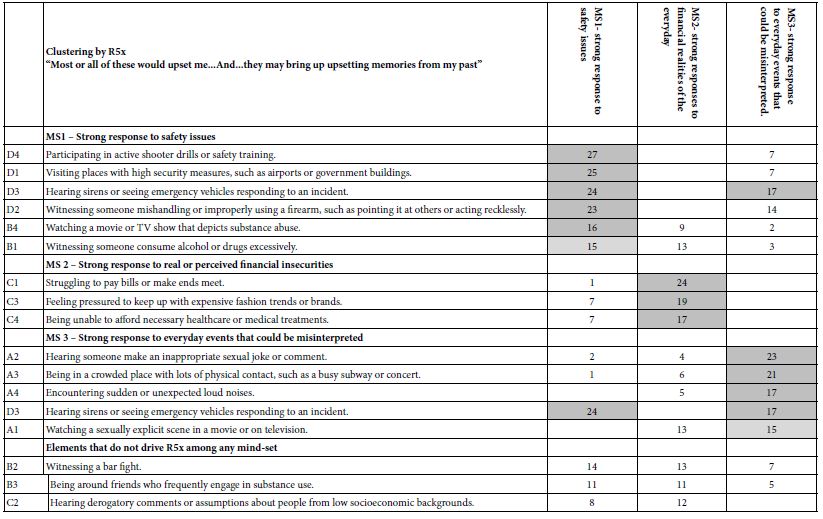

A hallmark of Mind Genomics is the search for underlying groups of people based upon their ways of perceiving the presented elements. Rather than looking for general groups of people defined by how they behave or how they look at the world in general, Mind Genomics focuses on the ‘granular,’ where experience is real and immediate. The approach to clustering combines mathematics and interpretation. The mathematics uses the coefficients emerging from the OLS regression, those coefficients showing how each of the elements ‘drives’ the response. Recall that each binary dependent variable could be expressed as a linear combination of ‘weights,’ expressed by the equation: BDV (Binary Dependent Variable) = k1A1 + k2A2… k16D4. The mathematics creates an individual equation for each of the 101 respondents, relating the presence/absence of the elements to that individual’s ratings of R5x, the key dependent variable. The data returning from this first step comprises 16 columns, each column corresponding to one of the 16 elements, and 101 rows, each row corresponding to one of the 101 respondents. The numbers inside the cells are the coefficients. The second step clusters the 101 respondents, dividing the respondents first into two groups, and then into three groups, called clusters. The clusters are defined as comprising ‘similar patterns’ of coefficients, similarity in turn defined as high Pearson correlation between the 16 coefficients of pairs of respondents. The actual mechanics of computation do not consider the meaning of the elements. Rather, each cluster comprises individuals who show highly correlated patterns of coefficients. The centroids of the different clusters are quite different from each other [8]. The process of clustering ends up generating different groups of respondents, the patterns with a group or cluster being similar, and the average pattern of each cluster differing from the average pattern of the other clusters. Once each respondent is assigned to a cluster, the clusters become new subgroups, allowing the user to estimate the coefficients for each cluster. When the 101 respondents are clustered by the pattern of their coefficients, viz., by their responses to test elements, three radically different mind-sets emerge, each mind-set comprising elements with far higher coefficients. It is in the nature of clustering by mind-sets that the user isolates groups of people with clearly different and clashing responses to the same elements. The conflicting answers frequently obscure the underlying patterns as they negate each other, creating the misleading notion that there is nothing to examine. However, a clearer picture can emerge by reconciling these contradictions. Table 7 shows these three emergent mind-sets, and the substantially higher coefficients which emerge once the mutually canceling effects are diminished by separating the mind-sets from each other. We are left with several R5x coefficients of 20 and greater. AI was able to find a general pattern between each mind-set- MS1- “strong response to safety issues”, MS2- “strong responses to financial realities of the everyday”, and MS3- “strong response to everyday events that could be misinterpreted.”

Table 7: The three emergent mind-sets after clustering on the basis of R5x

By dissecting the specific elements within each mind-set, we gain insight into the commonalities among them and uncover potential narratives about the individuals they represent. For instance, in MS1, characterized by a “strong response to safety issues,” individuals exhibit a pronounced negative reaction to seven specific elements, as Table 7 shows. These elements collectively reflect situations involving safety drills, emergency scenarios, and the witnessing of potential crisis situations. Individuals within this mind-set possess a heightened sensitivity to safety and emergency preparedness. Without considering additional factors such as Adverse Childhood Experiences (ACE), a psychologist might infer that these individuals have likely encountered various forms of heightened emergency situations, perhaps including military veterans or individuals with backgrounds in high-stress environments. Specifically, those who endured childhood sexual abuse exhibited a strong negative reaction to mishandling a firearm. Whereas it may be challenging to directly infer the correlation between childhood sexual abuse and firearm mishandling, it underscores the complex psychological impact of trauma and its potential influence on perceptions of safety and threat. In contrast, individuals who grew up in poverty, often residing in high-crime areas in the USA, displayed heightened reactions to elements such as sirens, active shooter drills, high-security measures, and witnessing excessive alcohol and drug consumption. This connection is more readily understandable, as individuals from socioeconomically disadvantaged backgrounds may have been exposed to environments characterized by increased risk and danger, thus developing heightened sensitivities to these specific stimuli. These findings highlight the intricate interplay between childhood experiences, trauma, and individual reactions to various elements. By elucidating these connections, we gain valuable insights into the nuanced ways in which past experiences shape perceptions and responses, guiding more targeted and effective interventions for those impacted by trauma. Mind-Set 2 is dominated by individuals with obvious financial insecurities whether that be real- struggling to pay bills or make ends meet and being unable to afford necessary medical treatment- or imagined such as feeling pressured to keep up with fashion trends or brands. An intriguing observation is that none of the elements within Mind-Set 2 corresponded to any Adverse Childhood Experiences (ACE). This absence of ACE alignment in Mind-Set 2 aligns with the nature of financial insecurity, which may predominantly stem from present-day circumstances rather than from childhood traumas. Financial pressures, both real and perceived, can exert substantial influence on individuals’ daily lives and psychological well-being, often overshadowing the impact of past adverse experiences. Furthermore, the unique composition of elements within Mind-Set 2 underscores the diverse manifestations of financial insecurity, ranging from tangible economic hardships to more intangible pressures of societal expectations. This multifaceted nature highlights the complexity of individuals’ experiences and the various factors contributing to their mind-set and behavior. For example, experiencing childhood poverty did not correlate to a mind-set of financial insecurities as an adult, which may seem perplexing at first glance. However, a deeper analysis reveals that individuals who endure childhood poverty might develop coping mechanisms to navigate persistent financial pressures, thereby mitigating the fear of financial strain in adulthood. Alternatively, they could be driven by an increased motivation to break free from the cycle of poverty, thereby reducing the impact of financial insecurities on their mind-set as adults. Finally, Mind-Set 3, characterized by a “strong response to everyday events that may be misinterpreted,” shares some similarities with Mind-Set 1. The difference, however, comes from the focus on situations commonly encountered by everyone, albeit with an elevated response. These elements encompass everyday occurrences which might typically evoke minor reactions but can trigger heightened distress for individuals belonging to this mind-set. For instance, encountering sudden or expected loud noises, such as a car backfiring, may prompt annoyance or momentary surprise for many individuals. However, for someone with a history of childhood trauma and hypervigilance, this noise could induce a more profound and prolonged state of distress. Moreover, the only specific adverse childhood event associated with Mind-Set 3 is having a household member with mental illness or suicide. This association underscores the profound impact of familial dynamics and mental health struggles within the household on an individual’s psychological well-being. The absence of other ACEs in this mind-set suggests that the elevated responses to everyday events may be influenced primarily by experiences within the immediate family environment, rather than broader childhood traumas. However, this is a hypothesis that would benefit from further exploration given the nature of the elements strongly responded to by MS3, specifically crowded places, loud noises, and sexually explicit content, respectively. A final point to make is that only out of all of the elements that were significant within a specific ACE category as seen in Table 6, each element had an intersection with one of the three Mind-Sets in Table 7. The only except was witnessing a bar fight, which elicited a strong negative response for individuals with a history of poverty, and those who had a household member who involved in criminal activity or incarcerated. This unique response suggests that the impact of witnessing a bar fight may transcend the typical associations with specific ACE categories and instead be influenced by broader environmental factors, such as socioeconomic status and exposure to violence in the community. This insight underscores the complexity of trauma and its intersectionality with various life experiences. By recognizing the specific elements that trigger strong responses within each ACE category and their corresponding mind-sets, we gain a deeper understanding of the interconnected factors contributing to individuals’ psychological well-being.

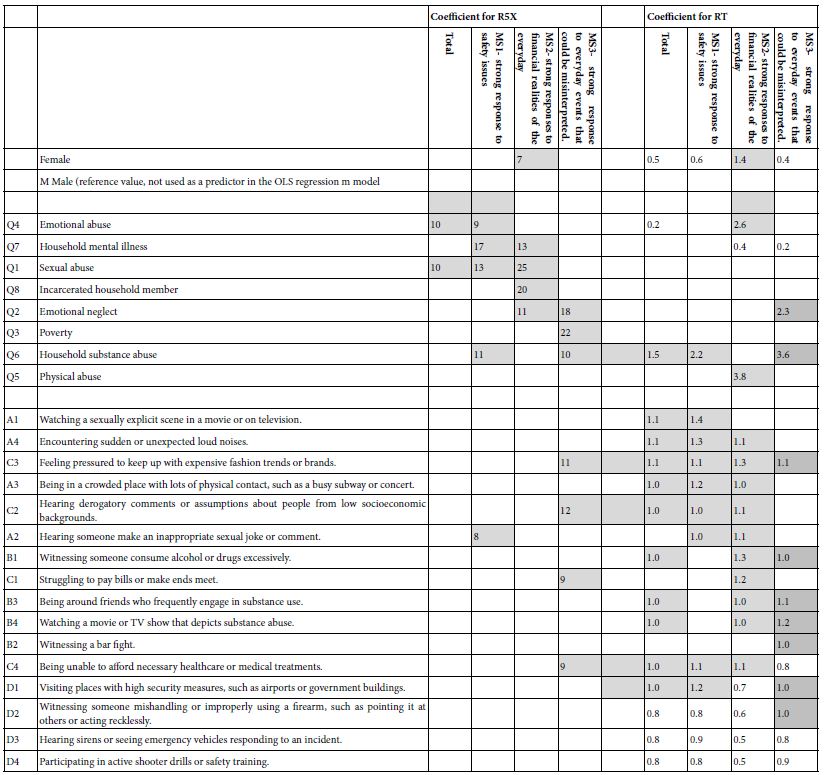

Meta-analysis: Contribution of Gender, Adverse Childhood Events, and Elements to Responses

Table 6 shows how the elements were associated with the eight ACE questions. Table 7 shows which elements strongly drive negative responses among respondents in the three mind-sets. The final analysis reveals patterns emerging when we reduce the stringency of our criterion importance by reducing the cut-off level of a coefficient of +8 or higher. using a coefficient of 8 or higher to represent strong coefficient. In this analysis, ACE, elements, and the three mind-sets were analyzed in a meta-analysis. The three objectives of this meta-analysis were: 1) Uncover the specific ACE questions and elements associated with the three mind-sets, 2) Explore gender association with each mind-set, 3) Explore response time (RT) as a function of gender and ACE experience. Table 8 shows the grand models, incorporating all predictors, for Total and for mind-sets. The grand model was created by OLS regression, using the presence/absence of the 16 elements for each vignette, but incorporating two new sets of predictor variables. One group was gender. Since there were only two genders considered, male and female, respectively, there was only one predictor. This was ‘Female.’ A respondent could either be a female or not a female. Thus, in Table 8 there is no coefficient for males. The second group was the ACE experience. For each of the eight ACE questions, the respondent was coded ‘1’ when the respondent reported having that ACE experience, and coded ‘0’ when the respondent reported not having that ACE experience. The result was a new set of 25 predictors for OLS, comprising 16 elements, one gender, and eight ACE experiences. Table 8 shows the strong performing elements shaded, as well as long response times shaded. For the binary dependent variable, R5x, a great deal has to do with who the respondent is, as show by the gender and by the ACE variable, with little additional effect due to the element. In contrast, response time is affected more by mind-set and by specific message. In this meta-analysis, few elements emerge as drivers of negative feelings. In fact, only one element “hearing someone make an inappropriate sexual joke or comment” was associated with a specific mind-set, in this case Mind-Set 1. Mind-Set 1, characterized by heightened concerns about safety issues, is associated with emotional abuse, household mental illness, sexual abuse and household substance abuse. These experiences likely contribute to a heightened sensitivity to safety, and a tendency to perceive threats more acutely. In contrast, Mind-Set 2, marked by strong responses to real or perceived financial insecurities, exhibits correlations with household mental illness, sexual abuse, incarcerated household member and emotional neglect. Noteworthy, childhood poverty, which might intuitively be thought to align with concerns about financial stability in adulthood, does not fit into this mind-set. Additionally, Mind-Set 2 stands out as the only mind-set to display a gender bias toward female respondents, indicating potential gender-specific vulnerabilities related to financial insecurities. Within this mind-set, one of the elements was “feeling pressured to keep up with expensive fashion trends or brands,” which tends to weigh more heavily on individuals identifying as women. Mind-Set 3, characterized by strong responses to everyday events that could be misinterpreted, shows correlations with emotional neglect, poverty, and household substance abuse. This suggests that individuals in this mind-set may have experienced childhood environments where misinterpretation of everyday events was prevalent, potentially leading to heightened sensitivity to ambiguous stimuli in adulthood.The overlap of household mental illness, sexual abuse, emotional neglect, and household substance abuse across two out of the three identified mind-sets in this meta-analysis highlights the profound and interconnected nature of these adverse childhood experiences (ACEs) as shaping individuals’ psychological profiles and responses to their environment. Furthermore, it is noteworthy that physical abuse is the only ACE that does not align with any of the three identified mind-sets. These discrepancies underscore the complexity of trauma and its varied manifestations, indicating that some ACEs may elicit responses which transcend the thematic boundaries of the identified mind-sets. Overall, the patterns observed in the correlation between ACEs and mind-sets highlight the diverse pathways through which childhood traumas influence adult psychological profiles.

Table 8: Meta analysis, relating the rating of 5x (negative feelings) and RT (response times) to gender, to the eight ACE experiences, and to the presence/absence of the 16 elements.

Discussion and Conclusions

Traditionally, studying human cognition and emotion has been a complex and labor-intensive process, all too often relying on subjective assessments and limited sample sizes. The particular questions to ask, the elements, have always been a stumbling block to the researcher seeking to understand the ‘unwritten rules for appropriate stimuli’, relevant when working with patients in particular, with people in general. The AI contribution here through SCAS, focusing as it does on questions to ask and answers to use, provides a new tool to explore how people think. SCAS and its underlying AI empower the user the ability to iterate again and again in real time, understanding the topic more deeply by reading, thinking, and revising questions and answers, all in real time. The research ‘teaches’ as the user sets up the study, doing so in a way which engages because the material, ranging from the squib to the questions to the answers, is relevant, and the AI is hyper-focused. One should view AI as a tool that to enhance and to augment the capabilities of human researchers rather than something which replaces them.. In the context of Mind Genomics research, AI is a powerful ally, extending the reach and scope of human imagination in the creation of the test stimuli. As shown here with the study of trauma, it is the human researcher who can set up the study, and who can guide the analysis. Mind Genomics, with its focus on vignettes as experimental stimuli, offers a platform to delve into the complexities of trauma. These vignettes serve as windows into the subconscious, allowing individuals to explore thoughts and emotions, thinking and feeling. With AI’s assistance, the researcher can generate the elements, the raw material of the vignettes, ensuring that these elements resonate with diverse audiences to capture the essence of trauma across various contexts. The elements generated in this study by SCAS in the Idea Coach are witness to the ease with which Mind Genomics coupled with AI create some of the raw material needed to understand the mind. By gaining a deeper understanding of how trauma affects emotional processing, researchers can develop more effective interventions and treatments for individuals who have experienced childhood adversity. Overall, the integration of AI into the study of emotional responses to childhood trauma represents a convergence of cutting-edge technology and compassionate inquiry. AI-driven algorithms could potentially help identify personalized treatment plans tailored to an individual’s specific needs and circumstances, leading to better outcomes and improved quality of life. By harnessing the power of AI, researchers can unlock new insights into the complex interplay between personal experiences and psychological outcomes, ultimately paving the way for more effective interventions and support systems for those affected by trauma. Ultimately, the fusion of Mind Genomics, AI, vignettes, and statistics represents a paradigm shift in the study of trauma. It offers a holistic framework for unraveling the complexities of human experience, empowering us to explore, understand, and address trauma with unprecedented depth and precision. Through this interdisciplinary approach, we pave the way for innovative solutions and interventions which resonate with the intricacies of the human mind.

References

- McCambridge J, Witton J, Elbourne DR (2014) Systematic review of the Hawthorne effect: New concepts are needed to study research participation effects. Journal of Clinical Epidemiology 67: 267-2 [crossref]

- Schauer M, Elbert T. (2010) Dissociation following traumatic stress: Etiology and treatment. Zeitschrift für Psychologie/Journal of Psychology 218: 109–127.

- Felitti VJ, Anda RF, Nordenberg D, Williamson DF, Spitz AM, Edwards V, Marks JS, et al. (1998) Relationship of childhood abuse and household dysfunction to many of the leading causes of death in adults: The Adverse Childhood Experiences (ACE) Study. American Journal of Preventive Medicine 14: 245-258. [crossref]

- Austin A. (2018) Association of Adverse Childhood Experiences with Life Course Health and Development. North Carolina Medical Journal 79: 99-103. [crossref]

- Cloitre M, Courtois CA, Charuvastra A, Carapezza R, Stolbach BC, Green BL, et al. (2011) Treatment of complex PTSD: Results of the ISTSS expert clinician survey on best practices. Journal of Traumatic Stress 24: 615-627. [crossref]

- Gofman A, Moskowitz H [. Isomorphic permuted experimental designs and their application in conjoint analysis. Journal of Sensory Studies 25: 127-145.

- Kahneman D, (2011) Thinking, Fast and Slow. Macmillan.

- Aristidis Likas, Vlassis NA, Verbeek JJ (2003) The global k-means clustering algorithm. Pattern Recognition 36: 451-461.