DOI: 10.31038/IJOT.2020323

Abstract

Background: In vitro data demonstrated that TOL-19-001, a spirulina-based dietary supplement, improves tendon healing in IL-1β and ciprofloxacin induced tendinopathies

Aim: To obtain, from real life conditions, preliminary data on efficiency and safety of TOL19-001, before designing a high quality double-blind, controlled clinical trial.

Patients and methods: Cross-sectional survey including 300 consecutive subjects treated at least 3 months with TOL-19-001 for a tendinopathy. Patients were asked to fulfill a 37-item questionnaire including demographic data, previous and current sports activity, location and duration of the tendinopathy, previous and current treatments for tendinopathy, patient assessment of efficacy, safety, and satisfaction. Patients were classified according to the tendinopathy duration (<and> 6 months).

Results: 219 patients (73%) fulfilled the questionnaire (mean age 61, range 21-88). The most frequently involved tendons were rotator cuff (44%), lateral epicondyle (19%) and Achilles (16%) tendons. Before taking TOL19-001 most patients have been treated with NSAIDs and/or analgesics (56%), rehabilitation/physiotherapy (58%), corticosteroid injection (40%), and shock waves (21%). Patients with tendinopathy 6 months (65%) were not significantly different regarding demographics, sports activity and tendinopathy location. 88% of patients reported improvement in pain and function after TOL19-001 treatment. Time for achieving improvement was 8 weeks in 28%. There was no difference in patient’s satisfaction according to the involved tendon and the tendinopathy duration. 78% of patients who had to stop professional or sports activity were able to return to sport or work. The percentage of patients who returned to sport was lower in long-lasting tendinopathies (77% vs. 93%; p=0.004). There was no safety concern.

Conclusion: Due to its original mechanism of action, TOL19-001 might be helpful in patients with long-lasting tendinopathy, in whom the conventional treatment has failed. Randomized controlled trials are mandatory to confirm or refute these preliminary data.

Introduction

Tendinopathies account for a substantial percentage of overuse injuries in sports and are very common causes of consultation with General Practitioners (GPs), rheumatologists and sports medicine doctors [1,2]. The medical management of tendinopathy includes non-pharmacological approach (i.e., rest, rehabilitation with eccentric exercises and stretching, low laser therapy, extracorporeal shock waves, cryotherapy…) and pharmacological treatments [3-5]. The latter are mainly symptomatic and include analgesics, Non-Steroidal Anti-Inflammatory Drugs (NSAIDs), corticosteroid, prolotherapy, and hyaluronic acid [6] or Platelet-Rich Plasma (PRP) injections. NSAIDs, in the absence of an inflammatory process, do not change the course of chronic tendinopathy [5] and should be used with caution, because of a possible negative effect on the regenerative processes of tissue [7]. Corticosteroid injections are very commonly used but have a short-term effect on pain and their effectiveness at long term has not been evidenced [4]. However, despite the adequate use of the available therapies, tendinopathies can result in chronic disability and ultimately in the most severe cases, in tendon rupture most often requiring surgery.

Histologic abnormalities of tendinopathy include tenocyte apoptosis, disorganization of the collagen matrix, and acute or chronic inflammation mediated through an up regulation of pro-inflammatory cytokines, enhancing Matrix Metalloproteinases (MMPs) expression, and Prostaglandin E2 (PGE2) production [5,8,9]. Despite an appropriate management, after injury the tendon structure and mechanical properties can no more reach those of healthy tendons, especially because of higher concentrations of type III collagen, thinning of fibrils and hypercellularity [8]. All these histologic abnormalities result in tendon weakening that predispose to injury recurrences. However, most of the tendinopathies have a spontaneously favorable prognosis, and cure in a few weeks to a few months, even in absence of treatment, provided that relative rest is maintained.

TOL19-001 is a food supplement composed of spirulina, glucosamine sulfate and several antioxidants (ginseng, selenium, silicon, iron, vitamin E and zinc). Due to its mechanisms of action TOL19-001 might improve tendon healing by inhibiting the abnormal production of type III collagen. In an in vitro study Baugé et al. [8] showed that, in IL-1β stimulated human tenocytes, co-treatment with TOL19-001 reduced the effects of IL-1β by inhibiting by about 40% the induction of matrix metalloproteases MMP1, MMP2 and MMP3. Interestingly, TOL19-001 reduced dramatically (by 80%) type III collagen expression, suggesting a potential effect on tendon healing.

Before considering the design of a high quality clinical controlled trial, aimed to demonstrate the clinical effectiveness of TOL19-001 in patients with chronic or remitting tendinopathies, it seemed to us of mandatory to obtain data from real life conditions, on both efficacy and safety of TOL19-001. Hence, we conducted the present study by collecting data on safety and efficacy, in subjects suffering from a tendinopathy who have been treated with TOL19-001 in daily practice conditions. We particularly studied those whose tendinopathy had been evolving for more than 12 months. Indeed, if one can imagine that most of the patients, treated for a recent tendinopathy would have cured anyway in a few weeks or months, it is much unlikely that those suffering from a tendinopathy for more than 1 year, despite adequate care, can heal within a few weeks.

Patients and Methods

Design: Observational Cross-sectional Survey

Patients

300 consecutive patients who have been treated within the previous year with TOL19-001 (marketed under the brand name Cicatendon®, Labrha SAS, Lyon, France) at a dosing regimen of 2 capsules by day for at least 3 months, for a symptomatic tendinopathy, were asked to fulfill a 37-item standardized questionnaire. Patients were fully informed of the trial objectives and methodology and were required to give their oral informed consent on the scientific and anonymous usage of the data collected in the questionnaire. The survey was achieved in compliance with the reference methodology of the French “Conseil National Informatique et Libertés” (CNIL MR-001).

Patients were registered under a single number, in increasing order of inclusion (neither initials nor birth dates were registered). According to the French regulatory, no IRB number was necessary due to the non-drug status of the studied food-supplement. The questionnaire was administered by a single research nurse, blinded to the patient’s identity. Demographic data (gender, age, professional activity), previous and current sports activity, frequency of sports practice, location of the tendinopathy, history of recurring tendinopathy, time since diagnosis, analgesics and NSAIDs consumption, previous and current pharmacological and non-pharmacological treatments for tendinopathy, patient self-evaluation of efficacy, satisfaction with the treatment and tolerability were all collected on a 4-point Likert scale (4 pt-LS). Patients were classified according to the disease duration (<and> 6 months).

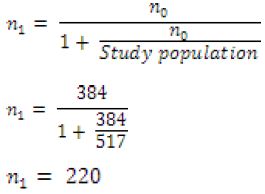

Statistics

A descriptive analysis was performed on the collected data. Qualitative variables were described using frequencies and percentages. Quantitative variables were described using mean, standard deviation and characteristics of their distribution (minimum, maximum and median). Univariate analysis was performed using chi-2 test or Fischer’s exact test, or Mann-Whitney test as appropriate. All statistical tests were carried out two tailed at the 5% level of significance. The statistical analysis was carried out using XLstats© software version 2019.3.2 (Addinsoft).

Results

Patients’ Characteristics

Two hundred nineteen patients (73%) accepted to fulfill the questionnaire: 59% were women, and 41% men. The mean age was 61, ranging from 21 to 88. Most patients were retired (56%) and practiced a regular sporting activity (61%), mostly twice a week. In 66% the present tendinopathy was the first one involving this tendon, but 51% had history of previous tendinopathy at other(s) tendon(s). The most frequently involved tendons were rotator cuff (44%), lateral epicondyle (19%) and Achilles (16%) tendons. Before taking TOL19-001 most patients have been treated with NSAIDs and/or analgesics (56%), rehabilitation and physiotherapy (58%) Forty percent received at least one corticosteroid injection, and 21% were treated with shock wave therapy. Prescribers were mostly rheumatologists (45%) and sports medicine practitioners (14%). The tendinopathy was attributed by patients to a transient overuse (26%), sports practice (24%), work (21%) and injury (13%). In 16% no etiology was mentioned. At time of TOL19-001 prescription, the tendinopathy has been evolving for less than 3 months in 20% of patients, from 3 to 6 months in 15%, from 6 to 12 months in 11% and for more than 1 year in 54%.

The 76 patients with recent tendinopathy (<6 months) and the 143 with long-lasting tendinopathy (>6 months) were not significantly different regarding gender, age, body mass index, sports activity, tendinopathy location (all p>0.05). Patients with long-lasting tendinopathy were more often treated by rheumatologists, whereas those with recent tendinopathy were more likely treated by sport medicine practitioners (p=0.04). Patients with long-lasting tendinopathy attributed it more frequently to their professional activity (27%) but the difference with patients with recent tendinopathy (12%) did not reach the statistical significance (p=0.07). Unsurprisingly the 2 subgroups differed in the treatments used before resorting to TOL19-001 (p=0.001): In 38% of patients with recent tendinopathy, TOL19-001 was the first-line treatment versus only 17% in patients with long-lasting tendinopathies. Long-lasting tendinopathies were more frequently treated with corticosteroid injection (44% versus 30%). The full patients’ characteristics are given in Table 1.

Table 1: Patients characteristics.

| Items |

Units |

All |

<6 Months |

>6 Months |

P Value |

| Number of patients |

N |

219 |

76 |

143 |

– |

| Gender: M/F |

% |

41/59 |

43/57 |

39/61 |

0.66 |

| Age (SD) range |

year |

61(13) 21-88 |

61 (13) 28-88 |

61(13) 21-86 |

0.99 |

| BMI (SD) range |

kg/m2 |

25(4) 18-35 |

24(4) 18-35 |

25(4) 18-38 |

0.70 |

Activity

- Active/Retired or inactive

|

%

|

44/56 |

51/49 |

42/58 |

0.26

|

| Regular sport practice: Yes/No |

% |

61/39 |

67/33 |

58/42 |

0.24 |

Weekly sport practice

- 1 time

- 2 times

- 3 times or more

|

%

|

29

42

30 |

32

47

21 |

25

39

35 |

0.08

|

| First tendinopathy: Yes/No |

% |

66/34 |

73/27 |

61/39 |

0.07 |

| History of other tendonitis Yes/No |

% |

49/51 |

49/51 |

49/51 |

1 |

Involved tendon

- Rotator cuff tendinopathy

- Epicondylitis

- Calcaneus tendinopathy

- Other

|

%

|

44

19

16

21 |

42

22

18

18 |

45

16

15

24 |

0.64

|

Previous treatment for current tendinopathy

- None

- Rehabilitation

- Shock waves

- NSAIDS/analgesics

- Corticosteroid injection

- PRP injection

- Hyaluronic acid injection

- Acupuncture

|

%

|

25

58

21

56

40

4

5

16 |

38

55

19

53

30

2

0

6 |

17

58

22

57

44

4

7

19 |

0.001

|

Prescriber of TOL19-001

- Rheumatologist

- Sport medicine

- Orthopedic surgeon

- General practitioner

- Other

|

%

|

45

14

4

4

33 |

36

22

1

4

37 |

50

10

5

4

31 |

0.04

|

Probable cause of tendinopathy

- Sport

- Work

- Injury

- Transient overuse

- No detectable cause

|

%

|

24

21

13

26

16 |

29

12

11

29

19 |

21

27

14

24

14 |

0.07

|

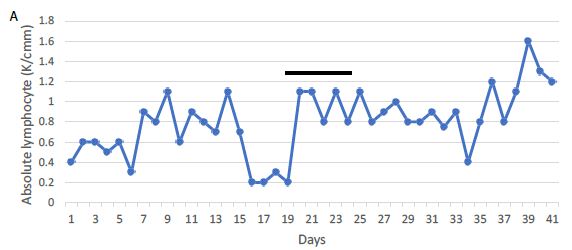

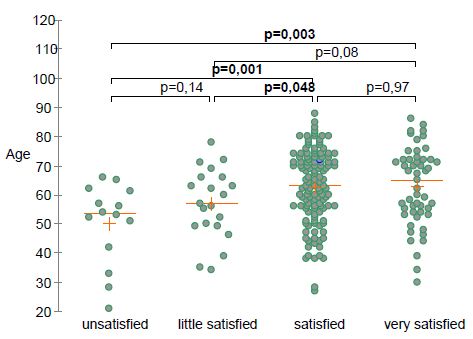

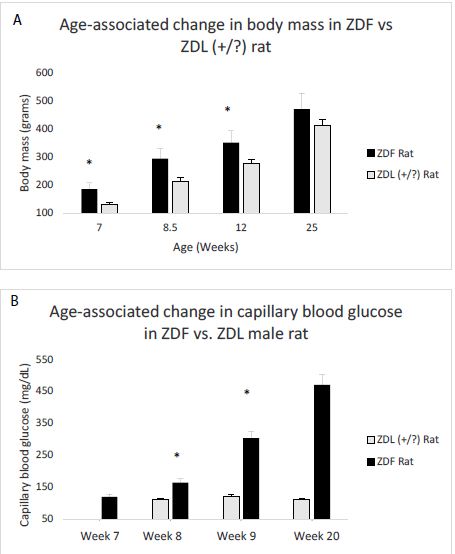

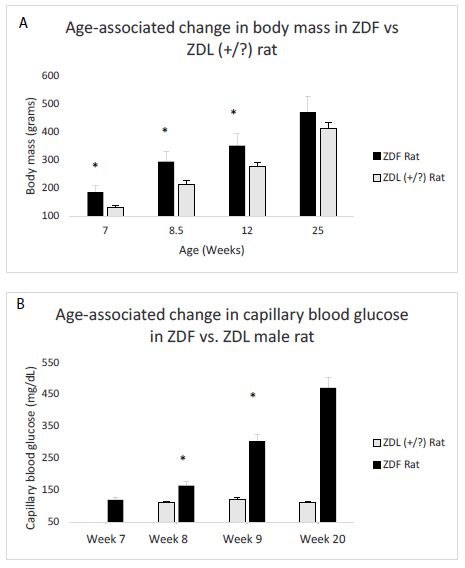

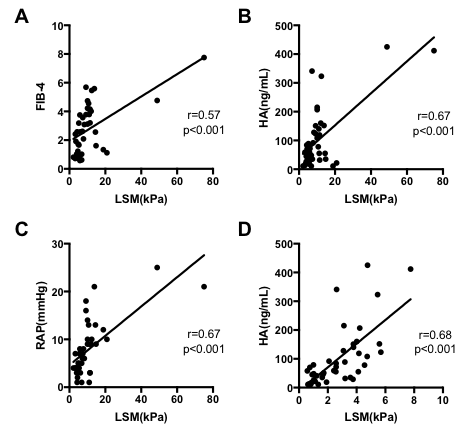

Efficacy Outcomes

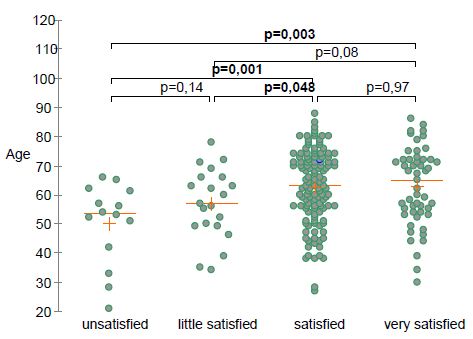

Eighty-eight percent of patients reported pain and function improvement after TOL19-001 treatment. Time needed to achieve improvement was <4 weeks in 36% of patients, 4 to 8 weeks in 37% and more than 8 weeks in 28%. After TOL19-001 treatment, 78% of patients who had to stop their professional of sport activity because of the tendinopathy, were able to return to sport or go back to work. Overall, 83% of patients expressed satisfaction with the treatment (24% very satisfied, 59% satisfied, 10% little satisfied, 7% not satisfied). There was no difference in the patient’s satisfaction according to the involved tendon (χ2, P=0.54; Fisher’s test, P=0.48) and gender (P=0.24). Satisfaction was positively correlated with age (Figure 1).

Figure 1: Self-rated patient’s satisfaction according to age.

Differences between Recent and Long-Lasting Tendinopathies

Even more interestingly, there was no significant difference in improvement (P=0.89), time before onset of improvement (P=0.12) and patient satisfaction (P=0.15) (Table 2), according to the tendinopathy duration. However, the percentage of patients who returned to sport or professional activities was lower in long-lasting tendinopathies (P=0.004) and the treatment duration was significantly longer (P=0.001) in the latter than in those with recent ones. All details are given in Table 3.

Table 2: Improvement, patient’s satisfaction and return to sport and professional activities, according to the tendinopathy duration (6 months).

| Items |

Units |

All |

<6 Months |

>6 Months |

P Value |

| Number of patients |

N |

219 |

76 |

143 |

– |

| Improvement Yes/No |

% |

88 |

93 |

86 |

0.89 |

Percentage of improvement

- <25%

- [25-50[%

- [50-75[%

- [75-100[%

- 100%

|

|

12.5

22.8

37.2

21.9

5.6

|

9

21

35

23

9 |

16

25

37

21

2 |

0.15

|

Time before improvement

- <2 weeks

- [2-4[ weeks

- [4-8[ weeks

- > 8 weeks

|

%

|

8

28

37

28 |

9

25

45

21 |

7

29

31

33 |

0.12

|

TOL19-001 treatment duration

- <3 months

- [3-6[ months

- >6 months

|

%

|

11

36

53 |

16

42

42 |

9

33

58 |

0.001

|

Satisfaction

- Very satisfied

- Satisfied

- Little satisfied

- Not satisfied

|

%

|

24

59

10

7 |

22

68

7

4 |

26

54

12

8 |

0.19

|

Return to sport or work

- Without limitation

- With some limitations

- No recovery

|

%

|

49.5

33

17.5 |

59

34

7 |

44.4

32.3

23.3 |

0.004

|

Table 3: Percentage of satisfied and unsatisfied patients according to the tendinopathy duration before TOL19-001 prescription (χ2 test: P=0.23; Fisher test: P=0.25).

|

Time Before TOL19-001 (month=M)

|

<1 M |

[1 M-3 M[ |

[3 M-6 M[ |

[6 M-12 M[ |

≥12 M

|

|

Level of satisfaction

(% of patients) |

1-Very satisfied

|

54.5 |

12.5 |

19.3 |

20.8 |

26.8 |

|

2-Satisfied

|

45.5 |

81.2 |

61.3 |

62.5 |

52.7

|

|

1+2

|

100 |

93.7 |

80.6 |

83.3 |

79.5

|

|

3-Little satisfied

|

0 |

6.3 |

9.7 |

12.5 |

11.6

|

|

4-Not satisfied

|

0 |

0 |

9.7 |

4.2 |

8.9

|

| 3+4 |

0 |

6.3 |

19.4 |

16.7 |

19.5

|

Safety

Neither severe nor serious Adverse Events (AEs) were reported by the patients. Safety was rated as very good or good by 97% of subjects. Only 7 patients reported minor gastrointestinal discomfort, possibly related to treatment. Three patients (1.4%) discontinued TOL19-001 for AEs.

Discussion

First of all it must be stressed that the present study has not been designed to demonstrate the efficacy of TOL19-001 in tendinopathies, but for giving information that could be useful to design, at best, a controlled trial. It should also be emphasized that, in the absence of a control group, we do not assert that TOL19-001 is an effective treatment for relieving pain and “accelerate” healing of tendinopathies. Although the magnitude of the clinical benefit may be overestimated due to a possible placebo effect, our results suggest that TOL19-001 may be helpful in many patients with long-lasting tendinopathies, in whom conventional therapies have failed. Indeed, it is unlikely that a chronic tendinopathy, lasting for more than 6, and even more than 12 months (i.e., 54% of our cohort), despite a well-conducted treatment (including rehabilitation and corticosteroid injection), spontaneously cures in less than two months, as we observed in several of our patients. On the contrary, as mentioned above, it is probable that most patients suffering from a tendinopathy for less than 3 to 6 months would have healed within 2 or 3 months anyway, even without treatment. It is the reason why we particularly focused attention on patients with tendinopathy evolving for many months (>12 months). Most of them had been forced to stop any sport or professional activity because of the tendinopathy. Among those patients, a large majority could return to sport or work after only a few weeks, most of the time without any limitation. More than 8 out of 10 patients considered TOL19-001 as very effective or effective and were satisfied with the treatment, whatever the tendon involved or the duration of the condition. Yet most of them had already received multiple treatments, without getting healing.

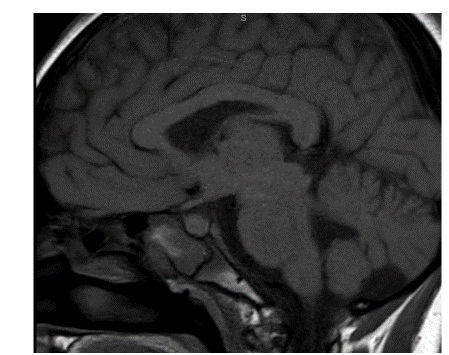

Our survey suffers from several limitations. The present data are patient self-reported and have been obtained retrospectively. Only 73% of TOL19-001 treated patients answered the questionnaire. So it cannot be presumed what the missing 27% would have answered. The retrospective nature of the survey made impossible to measure the decrease of pain over time. Furthermore, we were not able to obtain data about the anatomical severity of the condition and did not have any imaging data. Lastly, satisfaction with a treatment, is a subjective and patient-dependent data, involving many and varied parameters.

It has been shown that the mechanism of action of TOL19-001 is mainly mediated through its antioxidant properties [9]. TOL19-001 is mainly constituted of spirulina (Arthrospira maxima), an undifferentiated multicellular filamentous cyanobacterium, also called blue-green alga. Spirulina is known, since a long time, for being a potential source of vitamins and essential amino acids. Indeed, Spirulina contains a wide spectrum of nutrients including B-complex vitamins, minerals, essential amino-acids, beta-carotene, vitamin E. Spirulina is also noteworthy for its high contents (7%) in fatty acids (α-linolenic acid, linoleic acid, stearidonic acid, docosahexaenoic acid, and arachidonic acid) and proteins, making it desirable as a food supplement [10]. Spirulina has hypolipidemic, hypoglycemic, and antihypertensive properties. It is claimed to have also anti-cancer and immune-suppressing properties [11,12]. Spirulina also exerts a strong Radical Oxygen Species (ROS) scavenging activity and can reduce oxidative damage by decreasing free oxygen radical accumulation, through activation of several antioxidant enzyme systems (i.e., Superoxide Dismutase (SOD), glutathione peroxidase, catalase) [13]. The anti-inflammatory activity of Spirulina is mainly due to phycocyanin as demonstrated in several in vitro and in vivo animal models of arthritis [13].

Spirulina is also an important source of essential amino acids. A strong relationship between leucine and collagen synthesis has been demonstrated in several animal models [5]. A positive effect on collagen synthesis was demonstrated in malnourished mice teated with a leucine-enriched diet. Leucine increases hydroxyproline levels which plays a role in collageb fiber stability [14]. Glycine also stimulates the synthesis of both hydroxyproline and glycosaminoglycans, resulting in higher collagen fiber strength [15]. These properties could also support recovery from tissue damage [5].

TOL19-001® is mainly composed of Spirulina maxima (about 60%), but also contains significant amounts of glucosamine sulfate (~20%), and ginseng (~15%). Consequently, it is impossible to assert which of these components are responsible for TOL19-001 effect on the tendon. A systematic review [16] including preclinical and clinical data from 46 articles suggested that several nutraceuticals (i.e. curcumin, vitamin C, bromelain, glucosamine, chondroitin…) demonstrated beneficial effects on normal and pathological tendons through a possible role on collagen synthesis, inflammation, mechanical properties, oxidative stress, and analgesia. We previously published that TOL19-001® reduces the expression of MMPs, PGE2 and type III collagen in IL-1β stimulated cells. By reducing MMPs, TOL19-001 might reduce the deterioration and favor regenerative processes and tendon healing [8]. The downregulation of PGE2, likely plays a role in relieving pain due to tendon inflammation.

Glucosamine may also contribute to the beneficial effect of TOL-19-001 on tendon. Animal studies [17-19] have shown positive effects of glucosamine and chondroitin sulfate on collagen synthesis, tendon ultrastructural organization and biomechanical properties, probably as a consequence of the lower tissue inflammation and greater collagen synthesis [19]. Lastly, another reason for TOL19-001 effectiveness in long-lasting tendinopathies may be its ability in reducing type III collagen production, since type III collagen-rich scar tissue impairs tendon function and makes the tendon susceptible to re-injury [8]. This particular property might be beneficial effect on tendon healing, especially in long-lasting or recurrent tendinopathies.

Conclusion

This pilot cross-sectional study, carried-out in real life conditions gave interesting information on tendinopathies clinical evolution in patients taking TOL19-001. It suggested that TOL19-001 might benefit patients with long-lasting tendinopathy, in whom the conventional treatment failed. Further randomized controlled trials, focused on patients with long-lasting tendinopathies and using tendon imaging methods, are mandatory for confirming these preliminary results, and to assess the in vivo mechanisms of action of TOL19-001 on tendon tissue.

Authors Contribution

TC performed data analysis, contributed to the drafting the article, gave final approval of the version to be published, and agreed to be accountable for all aspects of the work.

PL wrote the article, gave final approval of the version to be published, and agreed to be accountable for all aspects of the work.

EN contributed to the drafting the article, gave final approval of the version to be published, and agreed to be accountable for all aspects of the work.

HB contributed to the drafting the article, gave final approval of the version to be published, and agreed to be accountable for all aspects of the work.

Funding

No funding.

None of the authors have received fees related to the present study.

LABRHA SAS paid only for the article publication.

Ethics Declarations

Conflict of Interest

HB declares having received fees from LABRHA SAS as a board member.

TC declares having received fees from LABRHA SAS as a scientific and medical consultant and board member.

EN and PL declare that they have no conflict of interests related to the present study.

Informed Consent

Due to the retrospective nature of the study, the patient consent was not required. We make sure to keep patient data confidential and compliance with the Declaration of Helsinki.

Availability of Data and Materials

All data generated or analyzed during this study are available at Laboratoire de rhumatologie appliqué; 19 place Tolozan, Lyon, France.

References

- Andarawis-Puri N, Flatow EL, Soslowsky LJ (2015) Tendon Basic Science: Development, repair, regeneration, and healing. J Orthop Res 33: 780. [crossref]

- McCormick A, Charlton J, Fleming D (1995) Assessing health needs in primary care. Morbidity study from general practice provides another source of information. BMJ 310: 1534. [crossref]

- Andres BM, Murrell GAC (2008) Treatment of tendinopathy: What works, what does not, and what is on the horizon. Clin Orthop Relat Res 466: 1539-1554. [crossref]

- Childress MA, Beutler A (2013) Management of chronic tendon injuries. Am Fam Physician 87: 486-490. [crossref]

- Loiacono C, Palermi S, Massa B, Belviso I, Romano V, et al. (2019) Tendinopathy: Pathophysiology, therapeutic options, and role of nutraceutics. A narrative literature review. Medicina (Kaunas) 55: 447. [crossref]

- Abate M, Schiavone C, Salini V (2014) The use of hyaluronic acid after tendon surgery and in tendinopathies. Biomed Res Int 2014: 783632. [crossref]

- Zhang K, Zhang S, Li Q, Yang J, Dong W, et al. (2014) Effects of celecoxib on proliferation and tenocytic differentiation of tendon-derived stem cells. Biochem Biophys R Commun 450: 762-766.

- Baugé C, Leclercq S, Conrozier T, Boumediene K (2015) TOL19-001 reduces inflammation and MMP expression in monolayer cultures of tendon cells. BMC Complement Altern Med 15: 217. [crossref]

- Riley G (2008) Tendinopathy-from basic science to treatment. Nat Clin Pract Rheumatol 4: 82-89. [crossref]

- Nicoletti M (2016) Microalgae nutraceuticals. Foods 5. [crossref]

- Khan Z1, Bhadouria P, Bisen PS (2005) Nutritional and therapeutic potential of spirulina. Curr Pharm Biotechnol 6: 373-379. [crossref]

- Finamore A, Palmery M, Bensehaila S, Peluso I (2017) Antioxidant, immunomodulating, and microbial-modulating activities of the sustainable and ecofriendly spirulina. Oxid Med Cell Longev 2017: 3247528. [crossref]

- Romay C, Armesto J, Remirez D, González R, Ledon N, et al. (1998) Antioxidant and anti-inflammatory properties of C-phycocyanin from blue-green algae. Inflamm Res Off J Eur Histamine Res Soc Al 47: 36-44. [crossref]

- Barbosa AWC, Benevides GP, Alferes LMT, Salomão EM, Gomes-Marcondes MCC, et al. (2012) A leucine-rich diet and exercise affect the biomechanical characteristics of the digital flexor tendon in rats after nutritional recovery. Amino Acids 4: 329-336. [crossref]

- Vieira CP, De Oliveira LP, Guerra FDR, De Almeida MDS, Marcondes MCCG (2015) Glycine improves biochemical and biomechanical properties following inflammation of the achilles tendon. Anat Rec 298: 538-545. [crossref]

- Fusini F, Bisicchia S, Bottegoni C, Gigante A, Zanchini F, et al. (2016) Nutraceutical supplement in the management of tendinopathies: A systematic review. Muscles Ligaments Tendons J 6: 48-57. [crossref]

- Taşkesen A, Ataoğlu B, Özer M, Demirkale İ, Turanli S (2015) Glucosamine-chondroitin sulphate accelerates tendon-to-bone healing in rabbits. Jt Dis Relat Surg 26: 77-83. [crossref]

- Lippiello L (2007) Collagen synthesis in tenocytes, ligament cells and chondrocytes exposed to a combination of glucosamine hcl and chondroitin sulfate. Evid Based Complement Alternat Med 4: 219-224. [crossref]

- Ozer H, Taşkesen A, Kul O, Selek HY, Turanlı S, et al. (2011) Effect of glucosamine chondroitine sulphate on repaired tenotomized rat achilles tendons. Eklem Hastalik. Cerrahisi 22: 100-106. [crossref]