Abstract

Background: Intrauterine growth restriction (IUGR) is the most common risk factor associated with perinatal mortality after excluding congenital anomalies 1. IUGR refers to a fetus that has failed to achieve its genetically determined growth potential and affects up to 7–10% of pregnancies 2. Fetal growth restriction is associated with an increase in perinatal mortality and morbidity. This is because of a high incidence of intrauterine fetal demise, intrapartum fetal morbidity, and operative deliveries. Neonates affected by IUGR suffer from respiratory difficulties, polycythemia, hypoglycemia, intraventricular hemorrhage, and hypothermia 3,4,5.

Objective: 1. Primary objectives: to evaluate the results of Microarray in symmetrical IUGR babies. 2.Secondary objectives: to compare between microarray positive babies and negative babies regarding: gestation age, weight, Apgar score, need and indications for NICU admission as well as length of NICU of stay.

Result: Between Jan 2016 and December 2017 total 10,695 babis were born. Among that 578 babis were IUGR (501 asymmetric and 77 symmetric IUGR). Total 71 babies were taken in our analysis after excluding 3 down syndrome and 3 babies part of multiple pregnancy. Microarray test had positive findings in 14/71 (19.7%). There were copy number changes of unknown significance in 8/71 (11.2%)

Conclusion: Most of the microarray test results were copy number changes of unknown significane which is comparitvely much higher than reported prevalence. Microarray positive IUGR had comparable NICU admissions to negative result group but their duration of stay, initial lower apgar scores and thrombocytopenia was significantly higher. This may be because, even copy number changes has unknown significane, they may have some clinical effect which is not known till now and may need further studies and long term follow up for those cases.

Keywords

Intrauterine growth restriction (IUGR), Chromosomal microarray analysis (CMA), Neonatal intensive care unit (NICU)

Abbreviations and Acronyms: Intrauterine growth restriction (IUGR), Chromosomal microarray analysis (CMA), Copy-number variants (CNVs), Toxoplasmosis, rubella, cytomegalovirus, rubella (TORCH), Neonatal intensive care unit (NICU), variant of uncertain significance (VUS).

Introduction

Intrauterine growth restriction (IUGR) is the most common risk factor associated with perinatal mortality after excluding congenital anomalies [1]. IUGR refers to a fetus that has failed to achieve its genetically determined growth potential and affects up to 7–10% of pregnancies [2]. Fetal growth restriction is associated with an increase in perinatal mortality and morbidity. This is because of a high incidence of intrauterine fetal demise, intrapartum fetal morbidity, and operative deliveries. Neonates affected by IUGR suffer from respiratory difficulties, polycythemia, hypoglycemia, intraventricular hemorrhage, and hypothermia [3–5].

Intrauterine growth restriction (IUGR) can be either symmetric or asymmetric. Symmetric IUGR is characterized by a similar and proportionate reduction in all auxological parameters, including weight, length, and cranial and abdominal circumference. Early gestational growth retardation would be expected to affect the fetus in a symmetric manner, and thus may have permanent neurologic consequences for the infant. Causes include chromosomal disorders, including trisomy 13, 21 and 18 and some rare genetic syndromes, such as Cornelia de Lange and Silver Russell syndromes and early congenital infections (rubella, cytomegalovirus, rubella, toxoplasmosis) [6]. Early-onset forms of IUGR represent more severe conditions and more links with perinatal mortalities [7].

Asymmetric IUGR is characterized by a greater reduction in body weight, when compared to the length and more commonly due to extrinsic influences that affect the fetus later in gestation, such as preeclampsia, chronic hypertension, and uterine anomalies. Karyotyping is an important investigation for symmetric IURG for chromosomal disorders particularly for babies with abnormal features. Chromosomal microarray analysis (CMA) is a high resolution, whole-genome screening technique that can identify most of the chromosomal imbalances as well as smaller submicroscopic deletions and duplications that are referred to as copy-number variants (CNVs) and has quicker turnaround time than a karyotype [8–10]. As microarray has a higher diagnostic yield than conventional karyotype, in our institute we are doing microarray instead of a conventional karyotype for all symmetrical IUGR.

Objectives

- Primary objectives: to evaluate the results of Microarray in symmetrical IUGR babies.

- Secondary objectives: to compare microarray positive babies and negative babies regarding: gestation age, weight, Apgar score, need and indications for NICU admission as well as the length of NICU of stay.

Study Methodology

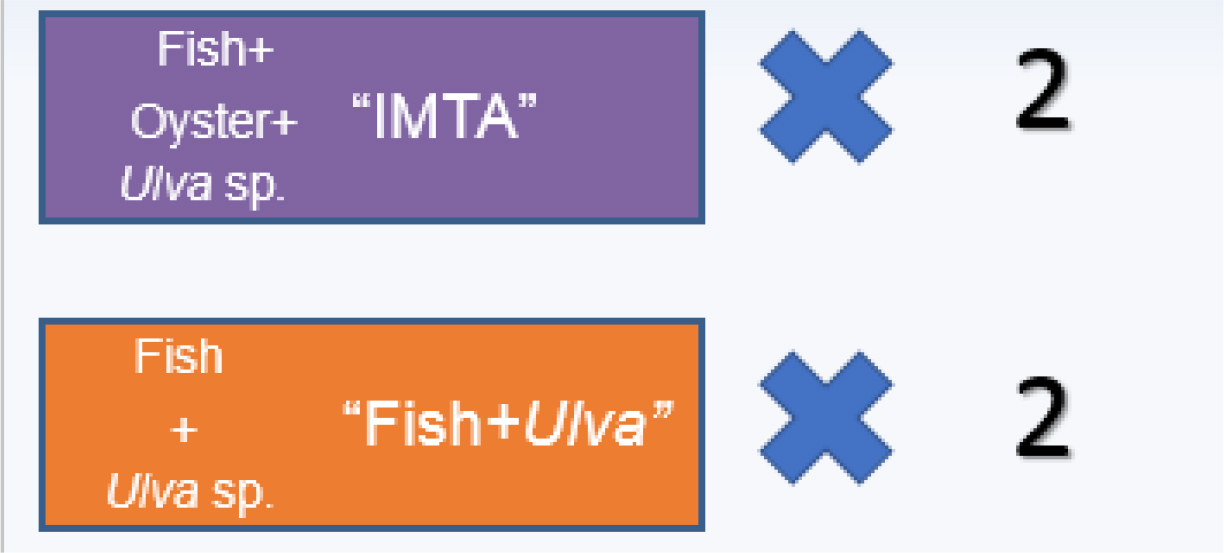

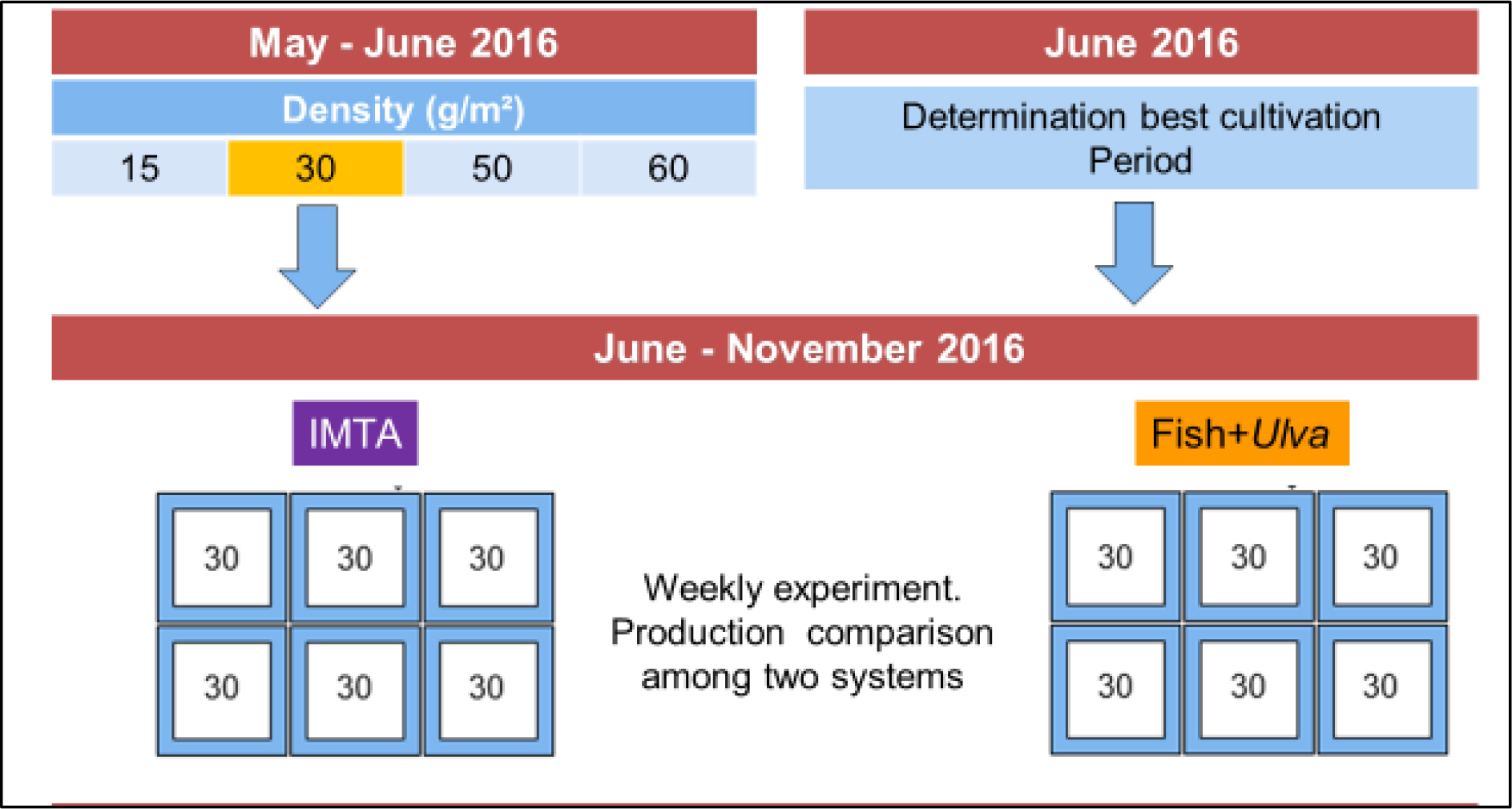

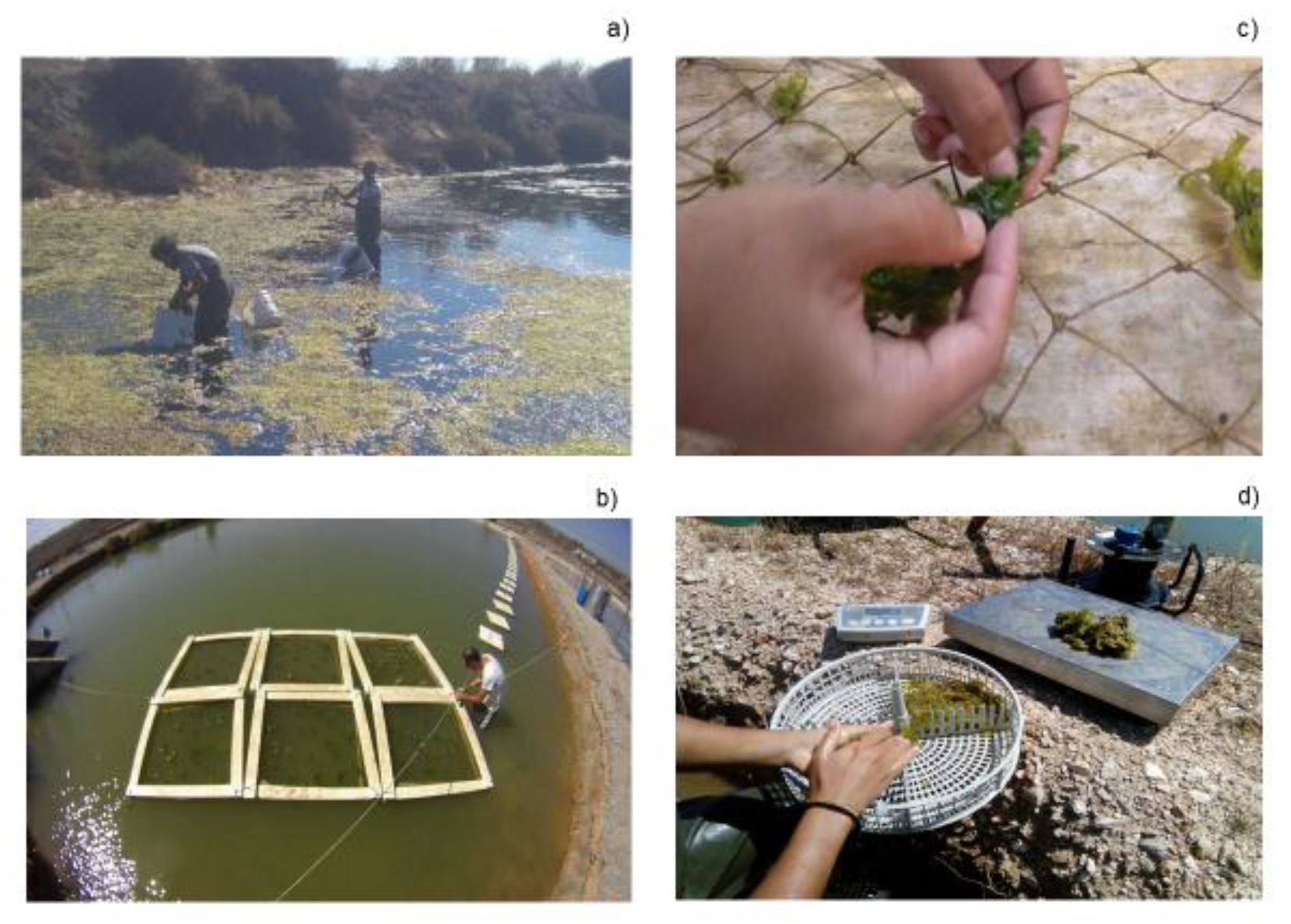

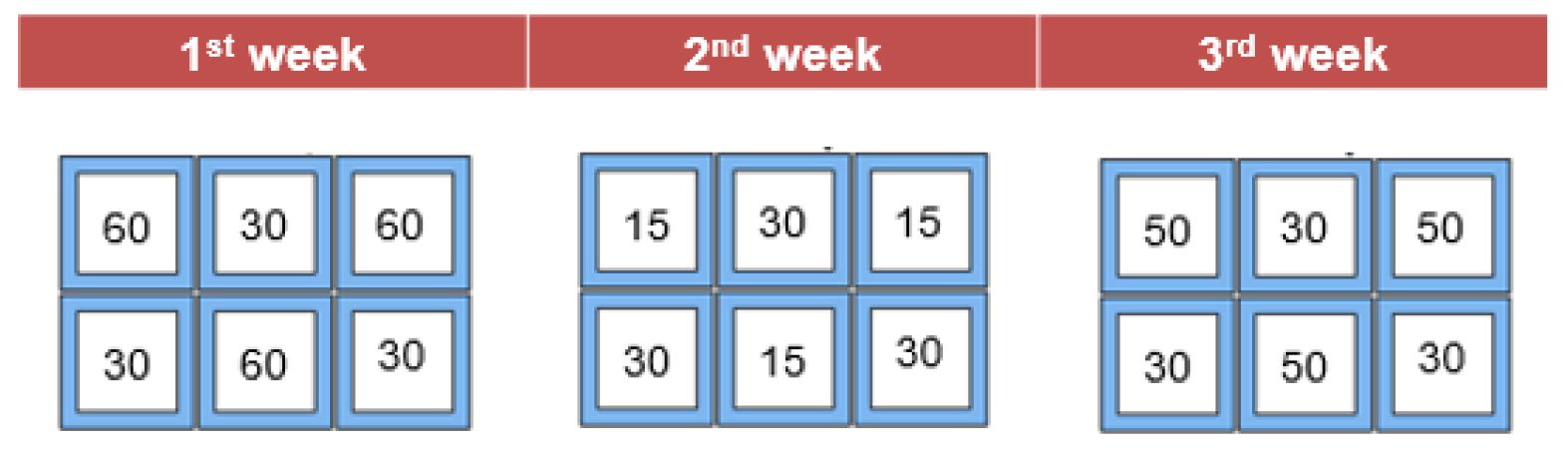

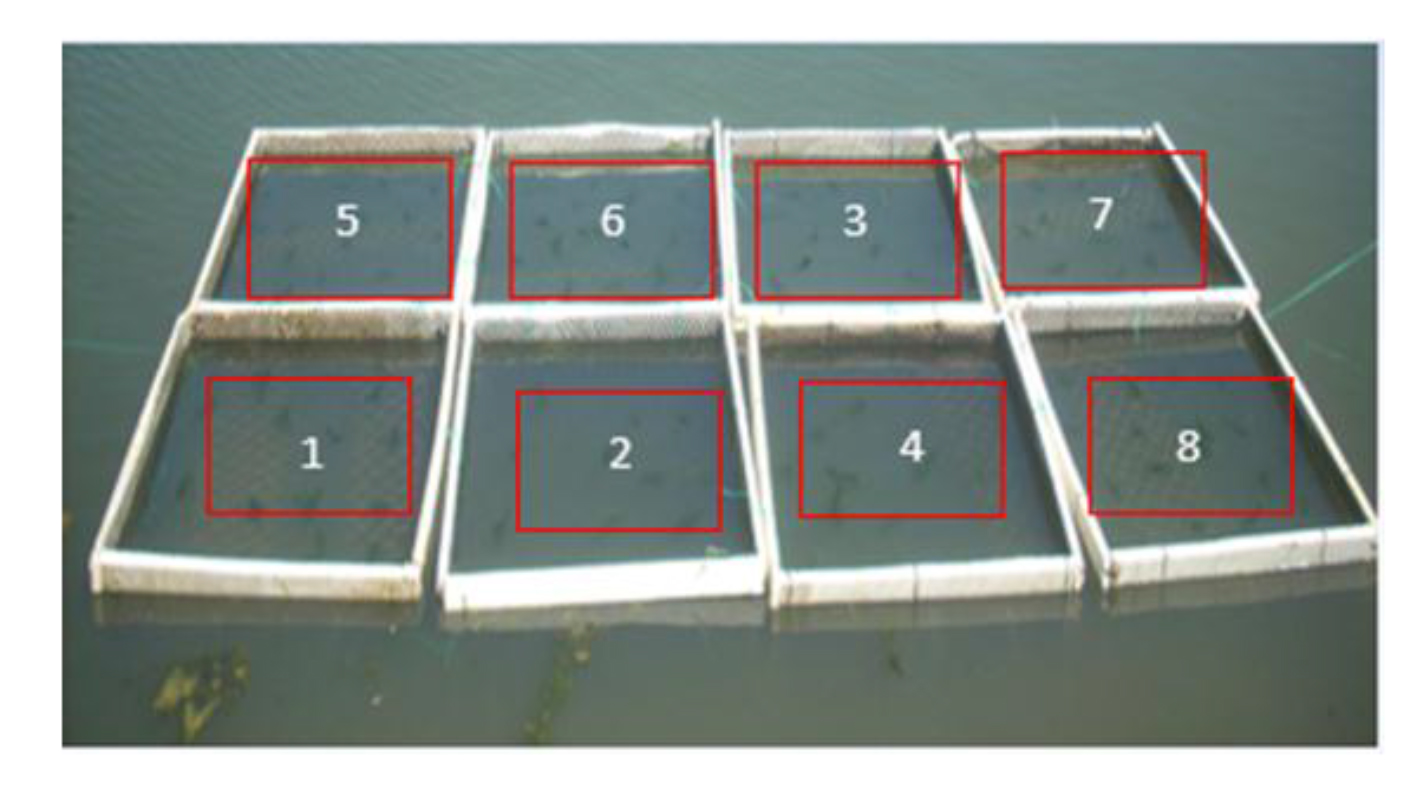

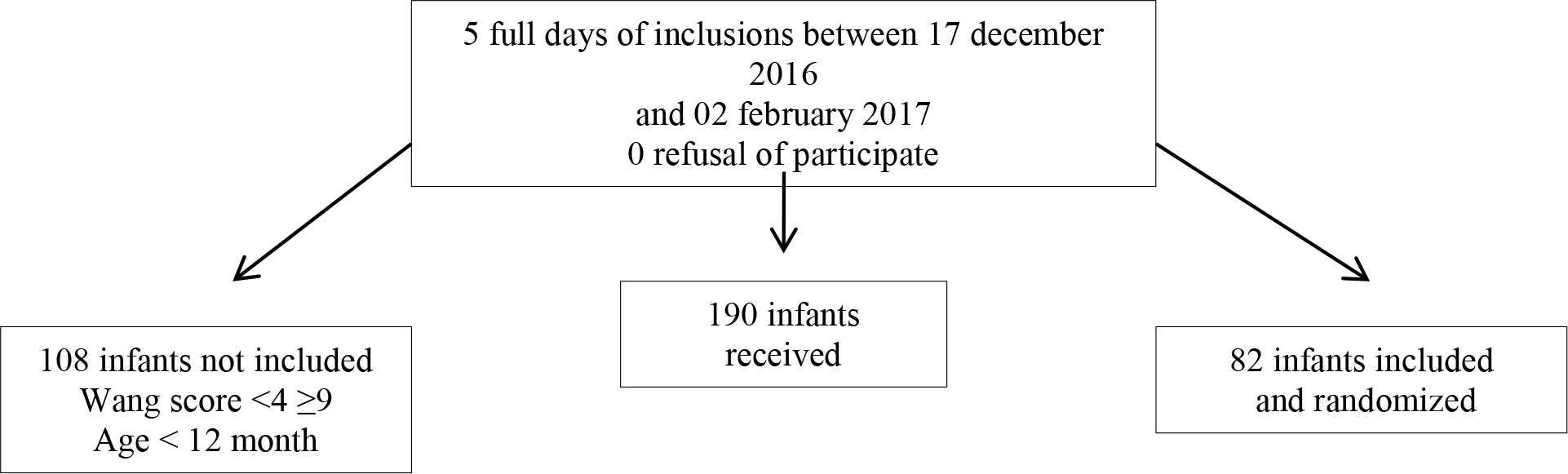

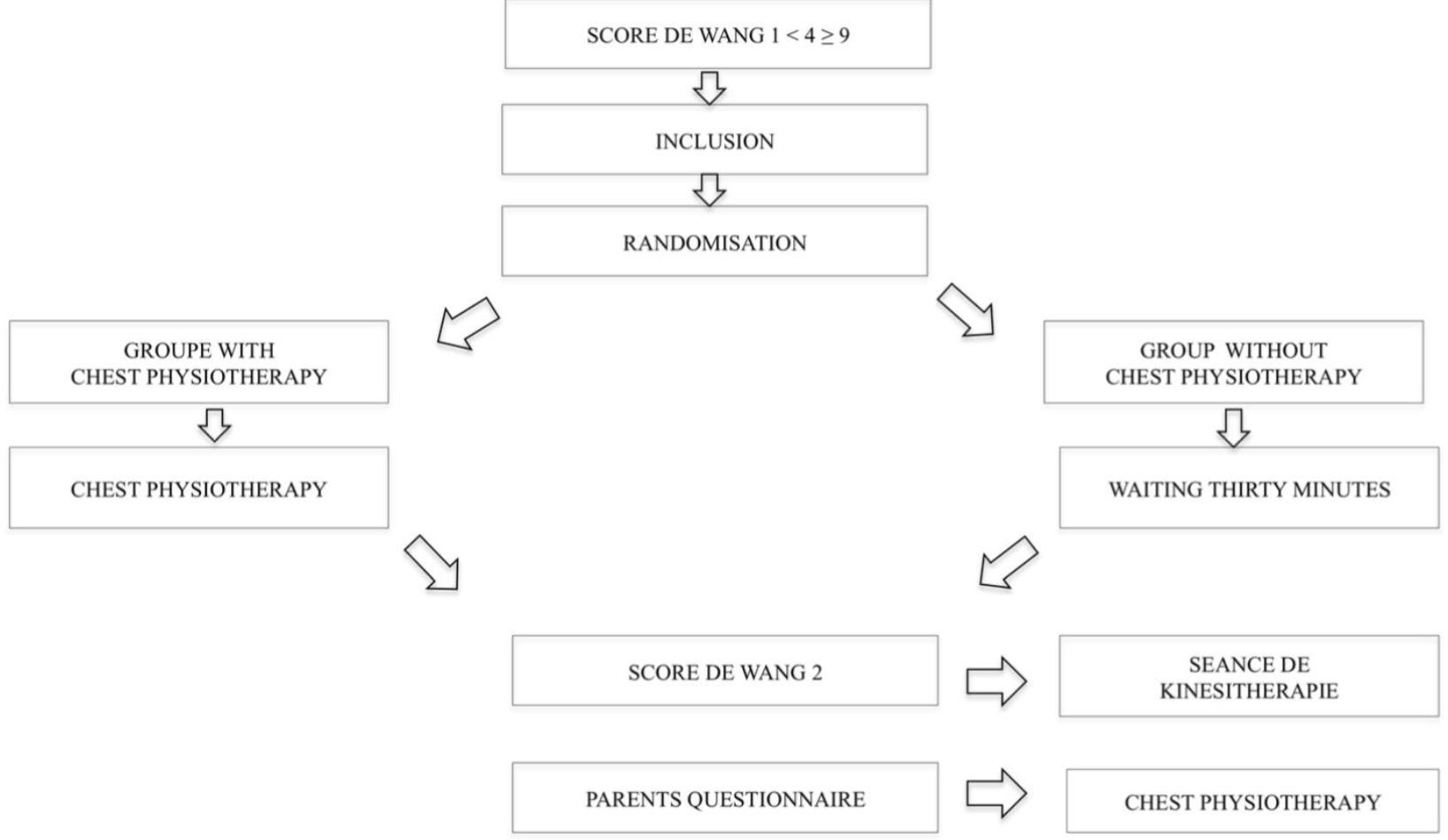

This is a retrospective study of symmetrical IUGR babies regarding their microarray results. Babies were considered symmetric IUGR if their growth parameter is less than 10 centiles of gestation age and sex. Symmetrical IUGR babies (as per growth curves) born in Al Wakra hospital, Qatar between Jan 2016 and December 2017 were included in this study. Exclusion criteria were Down syndrome babies, Multiple pregnancies and TORCH+ cases.

Required maternal and neonatal data were extracted from the electronic patient records (Cerner) and entered into the data collection sheet. Maternal data included: age, parity, history of abortions, family history, gestational age, mode of delivery, instrumental use for delivery, meconium stained liquor and fetal deceleration. Newborn data included: weight, sex, Apgar score at 5 minutes, need of resuscitation, cord pH, dysmorphic features or malformations, need for NICU admission, the reason of admission, duration of NICU stay and lab parameters as TORCH, microarray result, leukocyte count, platelet count, ultrasound and ECHO.

Data collection was started after approval from the institutional review board and ethical committee. For data analysis, SPSS 18 was used. Statistical test was applied as appropriate. P value was taken as significant if less than 0.05.

Microarray test method

The test was done by cytogenetic and molecular cytogenetic laboratory, Doha, Qatar. Genome-wide oligonucleotide array-based comparative genomic hybridization (aCGH) analysis was performed with the use of Human Genome CGH Microarray kit (OGT). The array contains ~40,000–180,000 DNA oligonucleotide probes spaced approximately 30–37kb apart genome-wide. The probe sequences and locations were from the human genome build (hg19). The purpose of this experiment was to identify any copy number changes (aneuploidy, gain/loss) associated with a chromosomal abnormality. Interpreted as per the database of Genomic Variants (projects.tcag.ca/variation).

Result

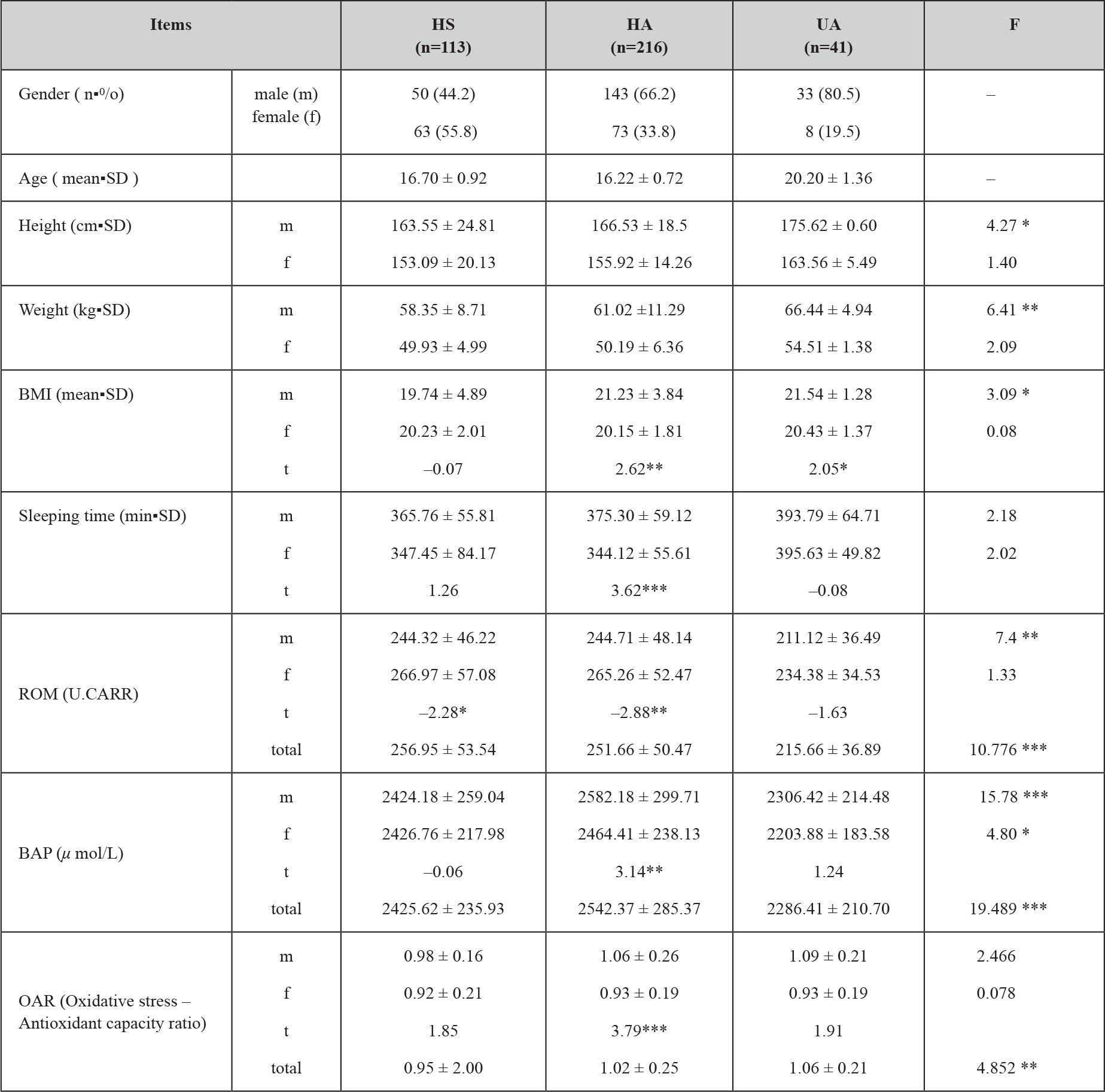

Between Jan 2016 and December 2017 total 10,695 babis babies were born. Among that 578 babis babies were IUGR (501 asymmetric and 77 symmetric IUGR). Total 71 babies were taken in our analysis after excluding 3 down syndrome and 3 babies part of multiple pregnancies. Microarray test had positive findings in 14/71 (19.7%). There were copy number changes of unknown significance in 8/71 (11.2%). In (Table 1) findings are presented. It was abnormal in 2/71 cases (2.8%), one 22q11.2 Deletion syndrome consistent with DiGeorge syndrome had left absent kidney but normal ECHO finding and another one trisomy 18 had atrial septal defect and ventricular septal defect. The latter died on day 18 of life.

Table 1. microarray test result findings in 14 positive cases. Interpreted as per the database of Genomic Variants (projects.tcag.ca/variation).

|

CASE |

RESULT |

MOLECULAR CHANGE |

CHANGE |

|

1 |

Likely Benign Familial Copy Number Change |

arr [hg19] 7q31.1(110,217,966–110, 692,136)X1 mat |

loss of the long arm of chromosome7 within cytogenetic band 7q31. The deleted segment is ~474-kb kilobases (kb) in size. |

|

2 |

familial benign copy number change of unknown significance |

arr[hg19] Xq11.2(63,481,708–64,416,909)X3 |

gain of ~935-kb of the long arm of chromosome X, within cytogenetic band Xq11. duplicated region contains OMIM gene ZC4H2, heterozygous deletion, and loss of mutation in this gene are reported in males with Wieacker-Wolff syndrome. |

|

3 |

copy number change of unknown biological significance |

arr [hg19]7q21.22 (88,419,362–89,016,837)X3, arr [hg19]13q21.33(71,030,914–71,903,305) |

two copy number changes, one is a gain of ~ 1.7 Megabase (Mb) in the long arm of chromosome 7 at cytogenetic band 7q21.2 and the second is a loss of ~872 kilobases (kb) in the long arm of chromosome 13 at cytogenetic band 13q21. No OMIM genes reported in these regions. |

|

4 |

Abnormal

|

arr [hg19] 22q11.1q11.2(17,364,612–19,835,391)x1 |

loss of the long arm of chromosome 22 involving the 22q11.2 is known as Velocardiofacial syndrome and DiGeorge syndrome (OMIM #192430) |

|

5 |

copy number change of unknown significance |

arr (hg19)18q12.1(25,278,479–26,575,519)X4 |

gain of the long arm of chromosome 18 involving cytogenetic bands 18q12. The duplicated region is ~1.3 Mb in size and includes the CDH2 gene. This gene belongs to cadherin gene family encode proteins that mediate calcium-ion-dependent adhesion. |

|

6 |

Likely benign copy number change

|

arr [hg19] 15q13.1(29,818,374–30,297,008)X3

|

gain of the long arm of chromosome 15 within cytogenetic band 15q13.1. The duplicated segment is ~478 kilobases (kb) in size and there is no reported OMIM gene in this region. |

|

7 |

Familial copy number change of unknown clinical significance

|

arr [hg19] 2p16.3(50,790,968–50,996,447)X1 pat

|

loss in the short arm of chromosome 2 within cytogenetic band 2p16.3. The size of the deleted segment is ~205 kilobases (kb), which causes partial deletion of the NRXN1 gene Heterozygous partial deletions, as well as other mutations and disruptions, of NRXN1 have been reported in association with susceptibility for neurocognitive disabilities, such as autism spectrum disorders (ASDs) |

|

8 |

copy number change of unknown significance |

arr [hg19] 22q11.1(17,666,611–17,809,359)X1 |

deletion of ~142-kb within cytogenetic band 22q11.1. The loss causes partial deletion of the CECR1 gene. Mutations in this gene have been reported in Polyarteritis nodosa, childhood-onset, an autosomal recessive condition |

|

9 |

copy number change of unknown significance

|

arr [hg19] 7q35(146,079,234–146,570,064)x3

|

duplication of ~491-kb within cytogenetic band 7q35. The copy number change causes partial duplication CNTNAP2 gene. Disruption of this gene in chromosomal rearrangements has been reported in children with autism. Homozygous mutations in this gene have been reported in children with seizures |

|

10 |

Copy number change of unknown clinical significance

|

arr [hg19] 11q13.4(73,688,299–73,783,214)X3

|

gain of ~94-kb of the long arm of chromosome 11, within cytogenetic band 11q13. This copy number change causes partial duplication of the OFD14 gene, suspected to be associated with Orofaciodigital syndrome XIV, an autosomal recessive condition |

|

11 |

Copy number change of unknown significance

|

arr [hg19] 3p26(2,213,357–2,277,767)X1

|

a ~64 kilobases deletion of the short arm of chromosome 3 within cytogenetic band 3p26, which causes partial deletion of the CNTN4 gene. Disruption of this gene have been reported in patients with physical features of 3p deletion syndrome |

|

12 |

Copy number change of unknown clinical significance |

arr [hg19] 6q14.3q15(86,371,996–88,176,951)X3 |

gain of ~1.8-Megabases (Mb) in the long arm of chromosome 6 around cytogenetic band 6q14 and q15. The duplicated segment contains multiple genes including GJB7, HTR1E etc |

|

13 |

Abnormal |

arr [hg19]18(1–48129895)X3 |

an extra copy of chromosome 18, known as Edwards syndrome. |

|

14 |

copy number change of unknown significance |

arr [hg19]11q25(133,662,374–134,373,630)X3 |

terminal duplication of ~711-kb of the terminal region of chromosome 11. The duplicated segment includes OMIM gene JAM3. |

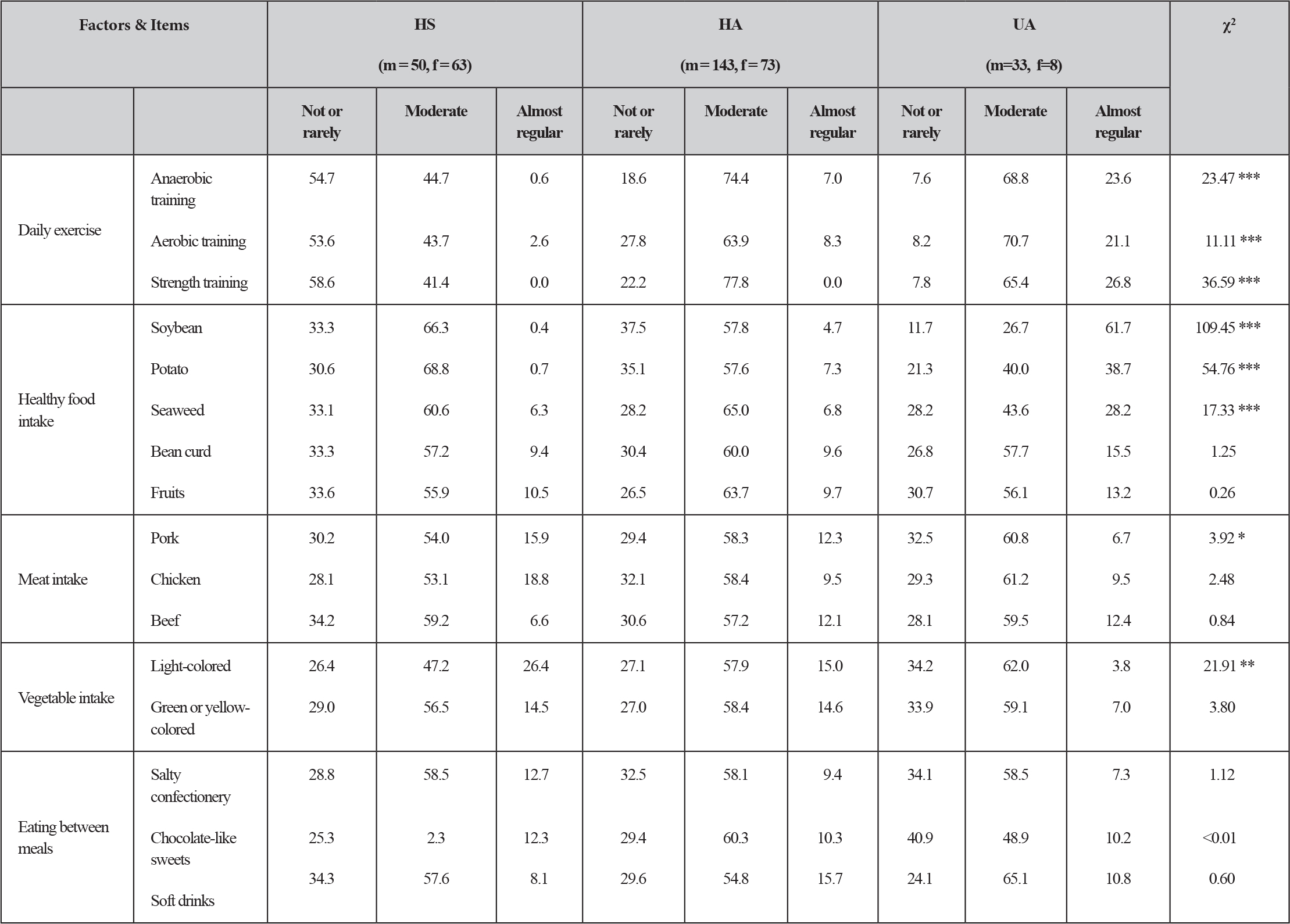

We had compared maternal outcome in microarray positive result group with negative result group in respect of parity, abortion, mother age, gestation age, delivery mode, instrument used for delivery, meconium stained liquor or fetal deceleration. Findings were not significantly different between groups. see (Table 2).

Table 2.

|

Microarray Test done |

Positive result |

Negative result |

Ods Ratio with CI 95% / |

P value |

|

Parity Number (%) |

Nulliparous 6 (43%), multipara 8 (57%) |

Nulliparous 30 (52%), multipara 27 (48%) |

1.78 (0.45 to 4.81) |

0.512 |

|

Abortion Number (%) |

4 (28.5%) |

16 (28%) |

1.02 (0.28 to 3.74) |

0.97 |

|

Mother age (year) mean±SD |

27.79 ±5.7 range 19–36 |

29.72 ±4.7 range 20–41 |

-1.9 (-4.8 to 0.99) |

0.192 |

|

Gestation age (weeks) mean±SD |

37.07 ±1.9 range 33–40 |

36.98 ±1.5 range 33–40 |

0.08 (-0.86 to 1.04) |

0.852 |

|

Delivery mode Number (%) |

Vaginal 8 (57%), caesarian 6 (43%) |

Vaginal 25 (44%), caesarian 32 (56%) |

1.7 (0.52 to 5.55) |

0.372 |

|

Instrument use Number (%) |

1 (7.1%) |

5 (8.7%) |

0.844 |

|

|

Meconium Number (%) |

1 (7.1%) |

7 (12.2%) |

0.54 (0.06 to 4.8) |

0.586 |

|

Deceleration Number (%) |

2 (14.2%) |

15 (26.3%) |

0.46 (0.93 to 2.33) |

0.345 |

|

Sex Number (%) |

Male 4 (28.5%) female 10 (71.5%) |

Male 25 (43.8%) female 32 (56.2%) |

0.51 (0.14 to 1.82) |

0.297 |

|

Weight (gram) mean±SD |

2044 ±409 |

2121 ±332 |

-77 (-130 to 248) |

0.461 |

|

Apgar at 5 min mean±SD |

9.4 ±1.15 |

9.9 ±0.34 |

-0.48 (-0.83 to -0.13) |

0.008 |

|

Resuscitation Number (%) |

2 (14.2%) |

3 (5.2%) |

3 (0.45 to 19.5) |

0.237 |

|

Cord pH mean |

7.313 |

7.03 |

0.28 (-0.66 to 1.2) |

0.107 |

|

NICU admission Number (%) |

7 (50%) |

31 (54.3%) |

0.83 (0.26 to 2.7) |

0.768 |

|

NICU stay (days) mean±SD |

18.14 ±10.6 |

8 ±6.28 |

10.1 (4.04 to 16.2) |

0.019 |

|

TORCH negative Number (%) |

14 (100%) |

55 (100%, in 2 cases not done) |

||

|

WBC 1000/cmm mean±SD |

10.36 ±4.2 (done in 8 cases) |

12.62 ±5.7 (done in 42 cases) |

-2.2 (-6.5 to 2.05) |

0.244 |

|

Platelet 100000/cmm mean±SD |

148 ±83 (done in 8 cases) |

221 ±99 (done in 42 cases) |

-73.1 (-146 to 0.1) |

0.045 |

|

Platelet <150 x 106 Number (%) <100 x 106 |

4/8 50% (done in 8 cases) 3/4 75% |

8/42 19% (done in 42 cases) 3/8 37% |

||

|

CI – Conficane interval, MD – Mean difference, WBC – white blood cells |

||||

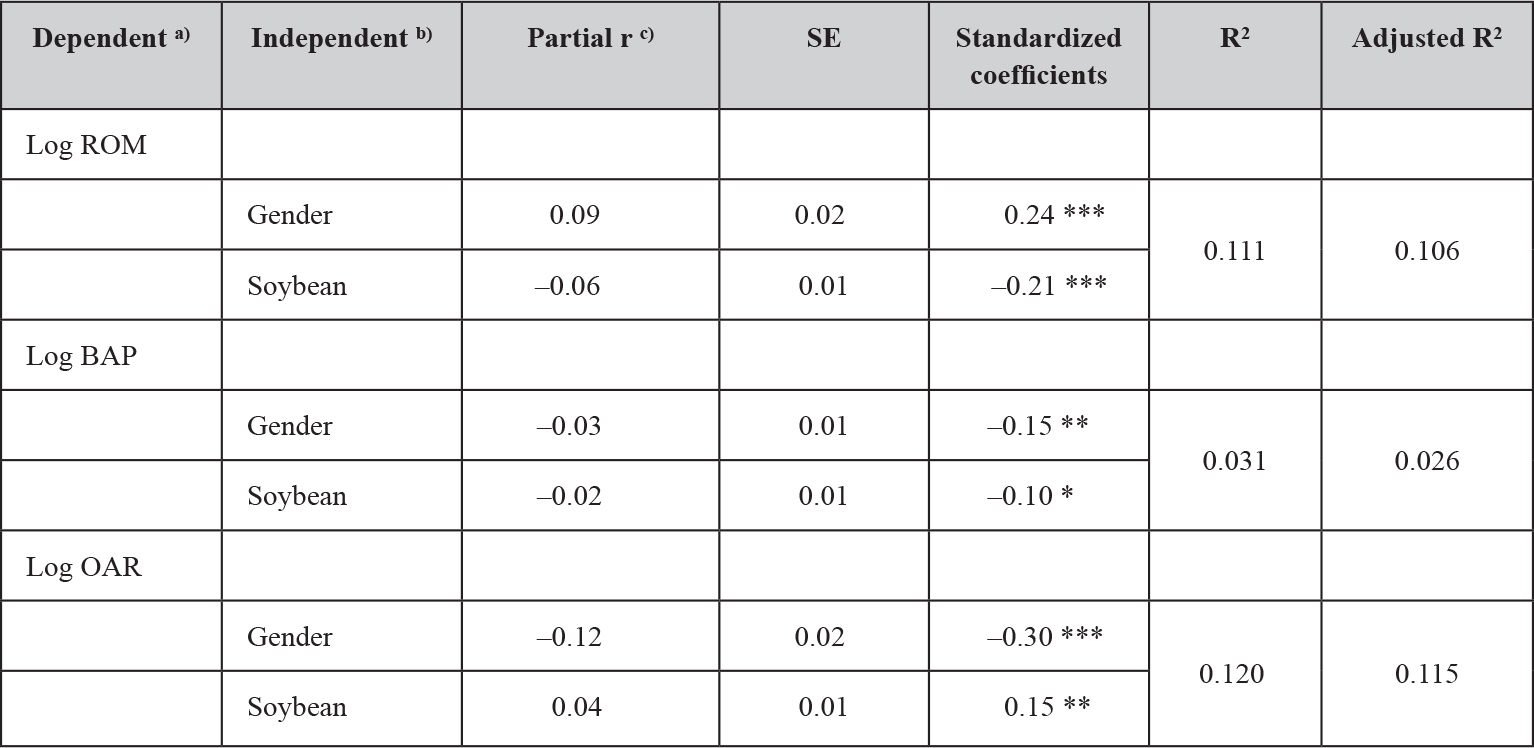

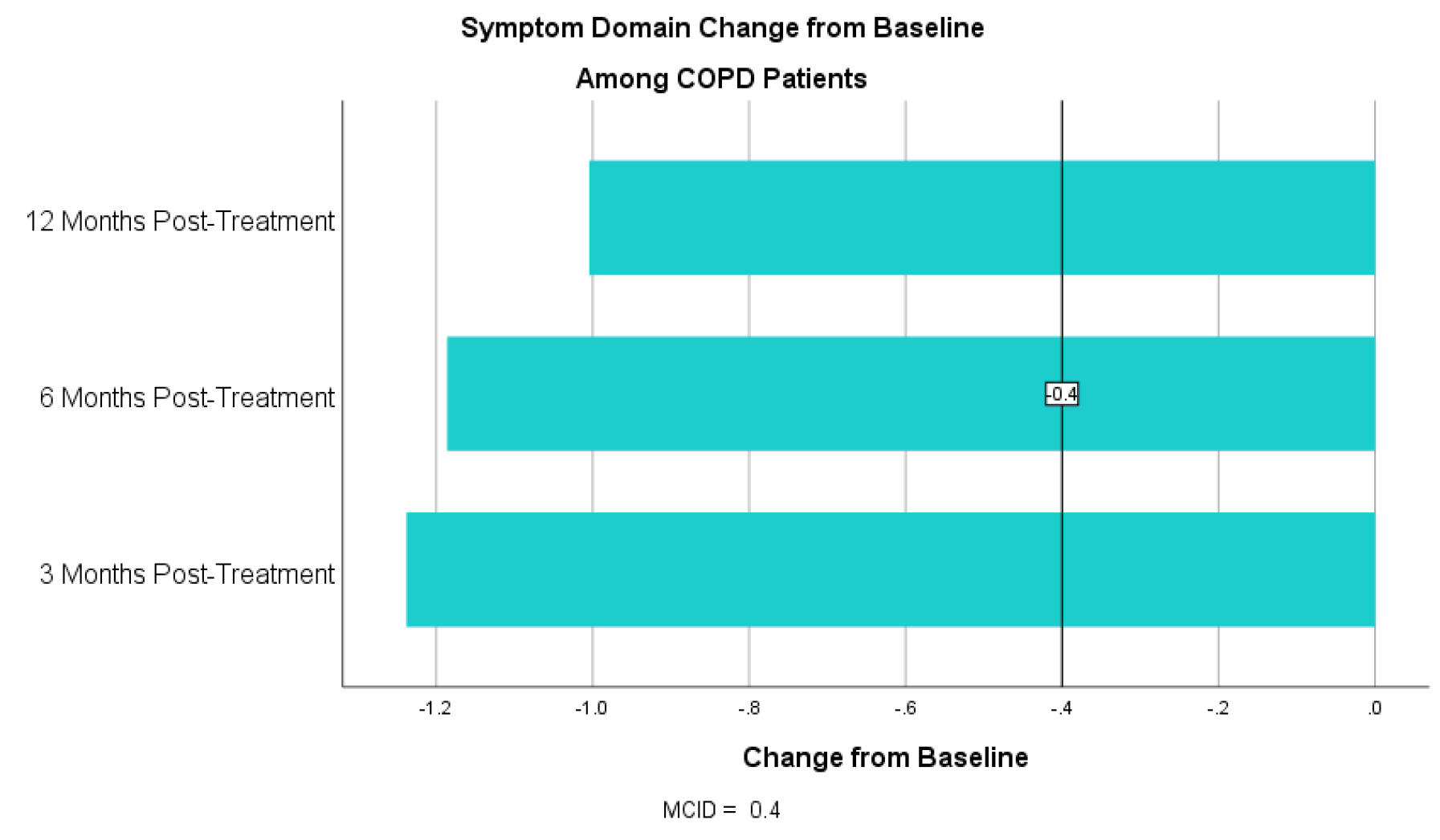

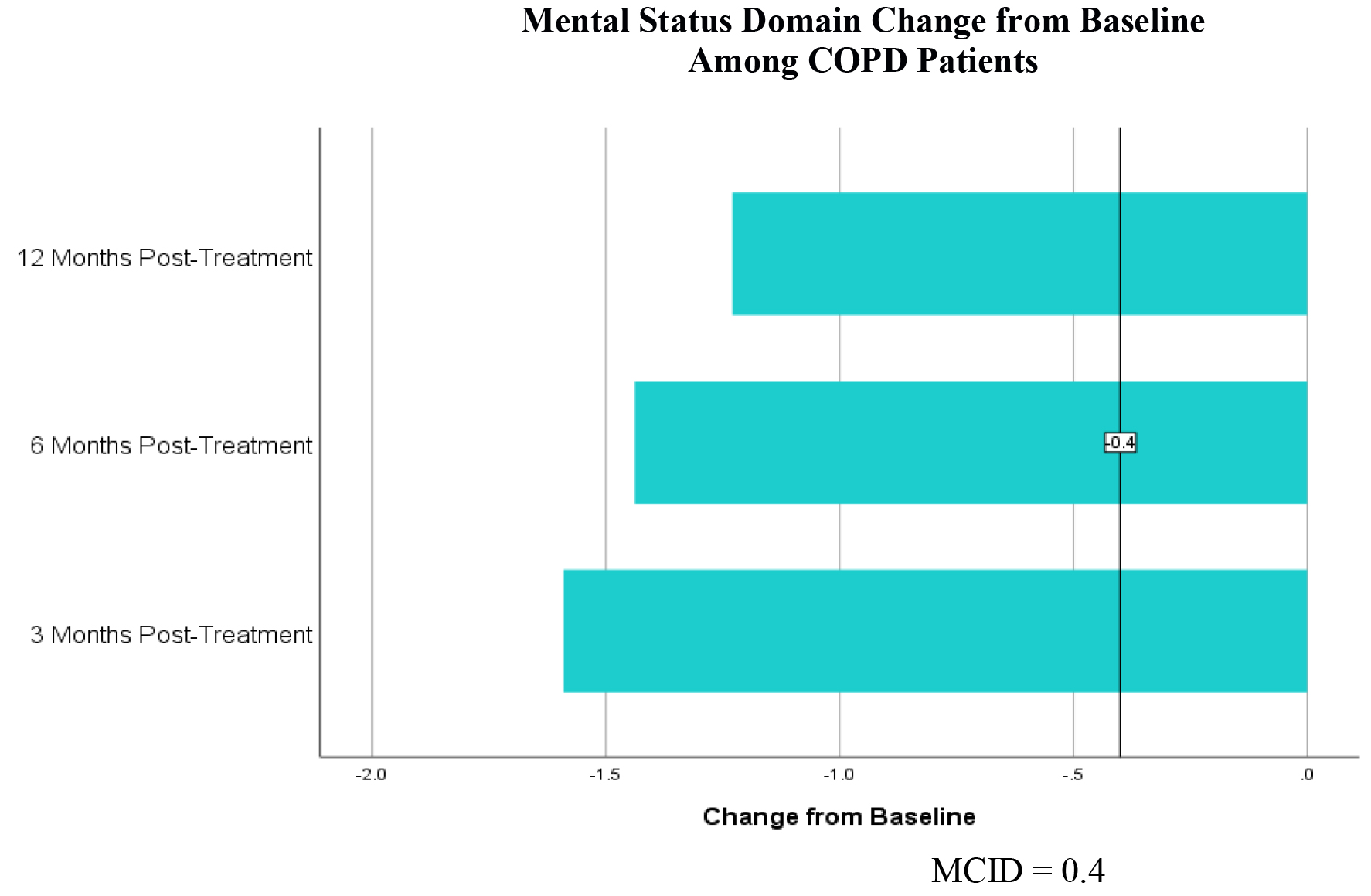

When compared some neonatal outcomes between the same two groups as sex, birth weight, the need of resuscitation, cord ph., NICU admissions, findings were not significant either. See Table 2. However apgar score at 5 minutes was statistically significant P 0.008 but clinically not significant mean 9.4/ 9.9. Duration of NICU stay was significantly high in microarray result positive group P 0.019, mean duration of stay ±SD 18.14 ±10.6 / 8 ±6.28 day. Among blood counts, platelets were significantly low in microarray positive result group P 0.045, mean ±SD 148 ±83 / 221±99. TORCH was done in 69/71 case and it was negative in all.

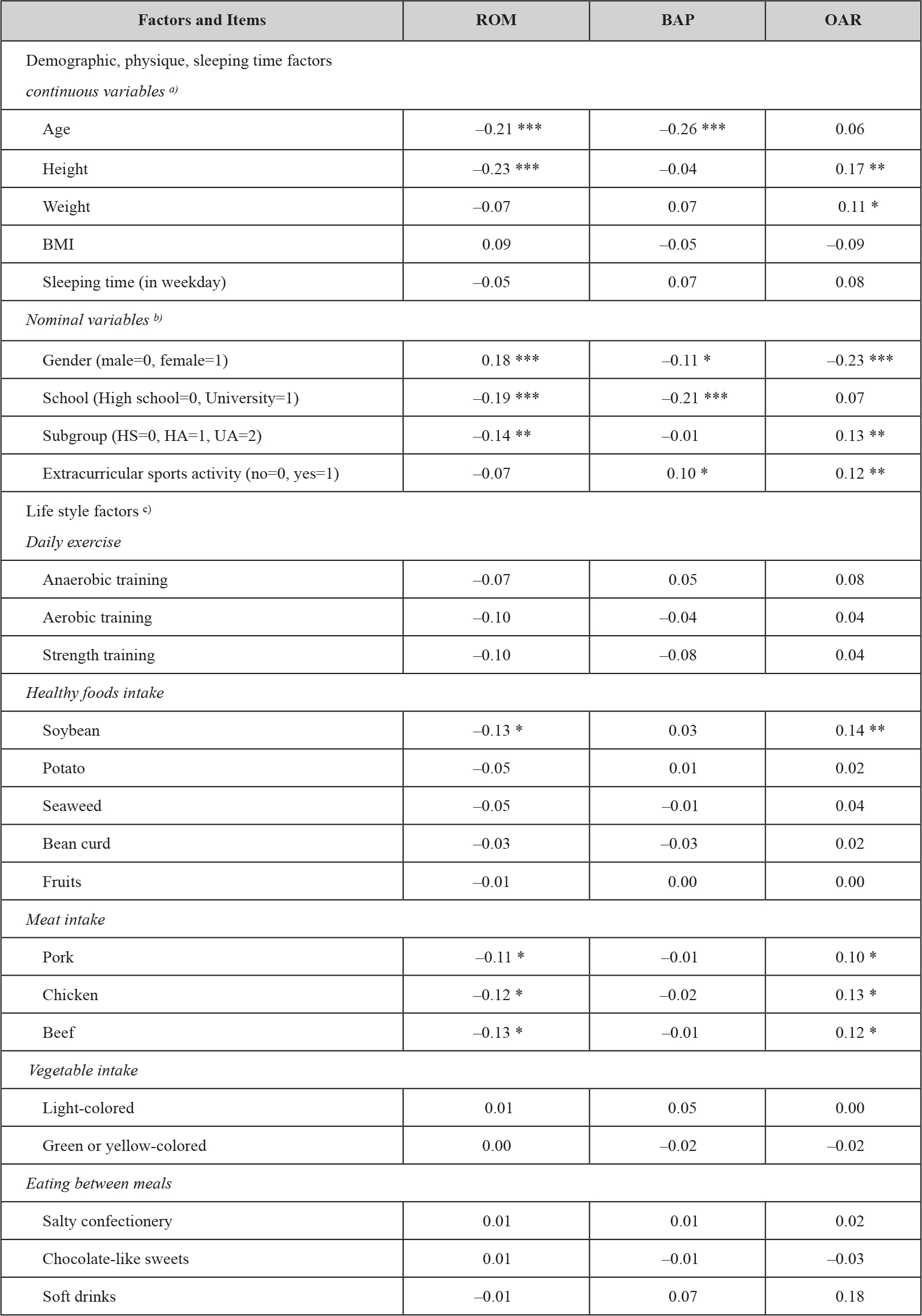

Ultrasound (brain ultrasound done in 13 cases and abdomen ultrasound in 13 cases) and ECHO done in 6 cases as clinically indicated; findings are presented in (Table 3).

Table 3. Ultrasound and ECHO result in microarray positive and negative result cases.

|

ULTRASOUND |

|||

|

Brain Abdomen |

|||

|

microarray |

Positive cases

|

Normal 4 Flare 1 |

Normal 3 Absent one kidney 1 |

|

Negative cases

|

Normal 7 Flare 1 |

Normal 7 Abnormal 0 |

|

|

ECHO |

|||

|

microarray |

Positive cases (done in 2 cases) |

Normal 1 , VSD &PDA 1 |

|

|

Negative cases (done in 4 cases) |

Normal 2, ASD 1, VSD 1, |

||

Discussion

Neonates affected with Intrauterine growth restriction (IUGR) not only have high prenatal and postnatal complication but also at high risk of cerebral palsy, developmental delay and behavioral dysfunction 4,5. Increasing evidence points to a link between IUGR and adult metabolic syndrome [11, 12].

As in early-onset symmetric IUGR one cause is chromosomal disorder. So, karyotyping is one investigation particularly if a baby is found with abnormal features. As Chromosomal microarray analysis (CMA) is a high resolution, whole-genome screening technique that can identify most of the chromosomal imbalances detected by conventional cytogenetic analysis, as well as smaller submicroscopic deletions and duplications and can be performed on uncultured DNA samples [10]. With accumulating experience during the last decade and data demonstrating improved detection of chromosomal abnormalities compared to conventional karyotyping, CMA is proving to be a valuable diagnostic tool in the prenatal setting [8,9]. Some recommend using CMA for genetic analysis when fetal structural anomalies and/or stillbirth need to be evaluated and to replace the need for fetal karyotype in these cases [10]. But CMA analysis will not detect balanced alterations (reciprocal translocation, inversions, Robertsonian translocations, and balanced insertions).

In our study, chromosomal changes were detected by microarray test in 19.7% (14/71) of symmetric IUGR babies and mostly copy number changes of unknown significance. In two cases it was abnormal 2.8% (2/71), one going with DiGeorge syndrome and another one trisomy 18. The latter died in the neonatal period. We did not find any study in IUGR babies to compare our result. In one study CMV was used as prenatal test for clinical indications as abnormal findings on fetal ultrasound, positive Down syndrome screening or maternal anxiety concerning advanced maternal age, family history of genetic disorder or previous child with anomalies; detected 20% (44/220) clinically significant copy number variants (CNV), of which 21 were common aneuploidies and 23 had other chromosomal imbalances [9]. In another study to see utility of chromosomal microarray in predicting neonatal outcomes in the setting of fetal malformations, they found that nineteen (26.8%) had pathogenic CNV and of these, there were 6 neonatal deaths (31.6%) compared to 8 of 49 (16.3%) in normal CMA cases (p . 0.16) [13]. In another study done on the utility of chromosomal microarray in anomalous fetuses, Abnormal CMA was not associated with increased odds of perinatal death in this cohort and fetal; such fetuses are at high risk of perinatal death irrespective of CMA result [14].

CMA technique does not require dividing cells, in contrast to conventional karyotyping, which requires cell culture, so has quicker turnaround time. CMA has a greater resolution than conventional karyotyping, allowing for the detection of much smaller, submicroscopic deletions, and duplications typically down to a 50- to 100-kb level [15]. The disadvantage of CMA is that it looks for genomic imbalance and is not able to detect totally balanced chromosomal rearrangements, such as translocations or inversions. Also, CMA does not provide information about the chromosomal mechanism of a genetic imbalance ie change is trisomy or an unbalanced Robertsonian translocation which sometimes need to be confirmed by a karyotype. [15,16] Another disadvantage of CMA is the inability to precisely interpret the clinical significance of a previously unreported CNV or to accurately predict the phenotype of some CNVs that are associated with variable outcomes 10. CNVs are characterized as benign, clinically significant (ie, pathogenic), and as a variant of uncertain significance (VUS). The overall prevalence of VUS is approximately 1–2% [17,18,19]. In our study it was in 11.2% symmetric IUGR babies which is much higher than reported prevalence. There is no study in IUGR babies to compare our result.

When comparing microarray positive cases with microarray negative cases, most findings were not significant except the duration of NICU stay and platelet count (Table 2). NICU admission was high among IUGR babies about 50% but comparable in both groups. In one study the overall admission rate was 7.2 per 100 births [20]. Leukopenia and thrombocytopenia are known in IURG. In our study thrombocytopenia was present in 24% (12/50) cases. Among microarray positive group it was in 50% (4/8) babies and in 75% of them (3/4) count was less than 100 x 106. Among microarray negative, thrombocytopenia was in 19% (8/42) and in 37% of them (3/8) count was less than 100 x 106. Platelet count is more significantly low in microarray test positive group 148/221 x 106 cmm P= 0.045. In our study TORCH was negative in all cases. One case with 22q11.2 Deletion syndrome had absent one kidney but normal cardiac anatomy. One case with trisomy 18 had atrial septal defect and ventricular septal defect.

Conclusion

Most of the microarray test results were copy number changes of unknown significance which is comparitively much higher than reported prevalence. Microarray positive IUGR had comparable NICU admissions to negative result group but their duration of stay, initial lower Apgar scores and thrombocytopenia was significantly higher. This may be because even copy number changes have unknown significance, they may have some clinical effect which is not known till now and may need further studies and long term followup for those cases.

This study has been Approved by Medical Research Center Hamad Medical Corporation # MRC-01-18-006

References

- Demirci O, Selçuk S, Kumru P, Asoğlu MR, Mahmutoğlu D, et al. (2015) Maternal and fetal risk factors affecting perinatal mortality in early and late fetal growth restriction. Taiwan J Obstet Gynecol 54: 700–704. [crossref]

- Bernstein IM, Horbar JD, Badger GJ, Ohlsson A, Golan A (2000) Morbidity and mortality among very-low-birth-weight neonates with intrauterine growth restriction. The Vermont Oxford Network. Am J Obstet Gynecol 182: 198–206. [crossref]

- Brar HS, Rutherford SE (1988) “Classification of intrauterine growth retardation,”. Seminars in Perinatology 12: 2–10.

- Bernstein I, Gabbe SG, Reed KL (2002) Intrauterine growth restriction,” in Obstetrics: Normal and Problem Pregnancies. Gabbe SG et al. (Eds.) Churchill Livingstone, New York, NY, USA, Pg No: 869.

- Soothill PW, Nicolaides KH, Campbell S (1987) Prenatal asphyxia, hyperlacticaemia, hypoglycaemia, and erythroblastosis in growth retarded fetuses. British Medical Journal 294: 1051–1053.

- Nikkila A, Kallen B, Marsal K (2007) Fetal growth and congenital malformations. Ultrasound Obstet Gynecol 29: 289–295.

- Baschat AA, Cosmi E, Bilardo CM, Wolf H, Berg C, et al. (2007) Predictors of neonatal outcome in early-onset placental dysfunction. Obstet Gynecol 109: 253e61.

- Zhu H, Lin S, Huang L (2016) Application of chromosomal microarray analysis in prenatal diagnosis of fetal growth restriction. Prenat Diagn 36: 686.

- Kan AS, Lau ET, Tang WF, Chan SS, Ding SC, et al. (2014) Whole-Genome Array CGH Evaluation for Replacing Prenatal Karyotyping in Hong Kong. PLoS ONE 9: 87988.

- Lorraine Dugoff, Norton ME, Kuller JA (2016) The use of chromosomal microarray for prenatal diagnosis. Am J Obstet Gynecol 215: 2–9.

- Barker DJ, Bull AR, Osmond C, Simmonds SJ (1990) Fetal and placental size and risk of hypertension in adult life. BMJ 301: 259–262. [crossref]

- Barker DJ, Winter PD, Osmond C, Margetts B, Simmonds SJ (1989) Weight in infancy and death from ischaemic heart disease. Lancet 2: 577–580. [crossref]

- Jacqueline Parchem, Teresa Sparks, Kristen Gosnell, Mary Norton (2015) The utility of chromosomal microarray in predicting neonatal outcomes in the setting of fetal malformations. American Journal of Obstetrics & Gynecology 212: 174–175.

- Parchem JG, Sparks TN, Gosnell K, Norton ME (2018) Utility of chromosomal microarray in anomalous fetuses. Prenatal Diagnosis 38: 140–147.

- Fruhman G, Van den Veyver IB (2010) Applications of array comparative genomic hybridization in obstetrics. Obstet Gynecol Clin North Am 37: 71–85.

- South ST, Lee C, Lamb AN, Higgins AW, Kearney HM (2013) Working Group for the American College of Medical Genetics and Genomics Laboratory Quality Assurance Committee. ACMG Standards and Guidelines for constitutional cytogenomic microarray analysis, including postnatal and prenatal applications: revision 2013. Genet Med 15: 901–909.

- Wapner RJ, Martin CL, Levy B, Ballif BC, Eng CM, et al. (2012) Chromosomal microarray versus karyotyping for prenatal diagnosis. N Engl J Med 367: 2175–2184. [crossref]

- Hillman SC, McMullan DJ, Hall G (2013) Use of prenatal chromosomal microarray: prospective cohort study and systematic review and metaanalysis. Ultrasound Obstet Gynecol 41: 610–620.

- Shaffer LG, Dabell MP, Fisher AJ, Coppinger J, Bandholz AM, et al. (2012) Experience with microarray-based comparative genomic hybridization for prenatal diagnosis in over 5000 pregnancies. Prenat Diagn 32: 976–985. [crossref]

- Harrison WN, Wasserman JR, Goodman DC (2018) Regional Variation in Neonatal Intensive Care Admissions and the Relationship to Bed Supply. J Pediatr 192: 73–79.