Abstract

Aims: To test whether a novel 5-hydroxytryptamine 2A decoy receptor peptide, SN..8 (Sertuercept), administered via intraperitoneal injection, acutely lowers arterial blood pressure in obese, hypertensive male Zucker diabetic rats (ZDF). To examine the safety, tolerability and possible reno-protective effects following chronic alternate daily administration of Sertuercept (for 10 weeks) in the male ZDF rat.

Methods: Systolic and diastolic blood pressure were determined at baseline and regular intervals for up to 48 hours after a single IP administration of either Sertuercept (2 mg/kg), vehicle (saline) or an identical concentration of a scrambled sequence of the decoy receptor peptide, LN…8, in male ZDF and Zucker lean rats using tail cuff plethysmography. Plasma autoantibodies were obtained in thirteen male ZDF rats for determination of 5-hydroxytryptamine 2A receptor-mediated neurotoxicity using an acute neurite retraction assay in mouse neuroblastoma cells. Rats were sacrificed at 25-weeks of age, the kidneys were perfused, fixed and sections were stained using Masson’s trichrome for semi-quantitative determination of glomerular and interstitial fibrosis.

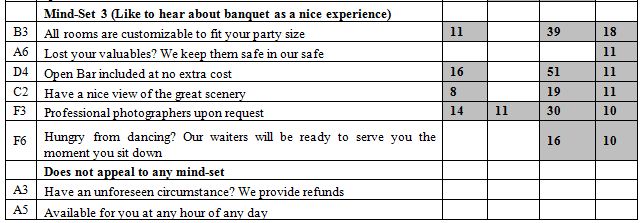

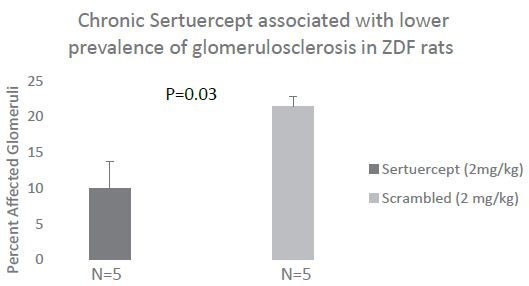

Results: Sertuercept (2 mg/kg IP) potently lowered systolic and diastolic blood pressure in both 11-week-old and 25-week-old male ZDF rats and in a subset of hypertensive Zucker lean rats. There was no significant blood pressure-lowering effect of vehicle (saline) or scrambled peptide sequence (LN.8). Blood pressure-lowering was rapid in onset (15-30 minutes following IP injection) and sustained for at least 24 hours. Alternate daily IP administration of 2 mg/kg dose of Sertuercept vs. scrambled peptide (for 10 weeks) was safe, well-tolerated and associated with a significant decrease in glomerulosclerosis in 25-week-old male ZDF rats. Plasma autoantibody-induced neurotoxicity correlated significantly with the global index of renal fibrosis severity in 25-week-old male ZDF rats.

Conclusions: These data indicate potent arterial blood pressure-lowering efficacy from a decoy receptor peptide comprised of a second extracellular loop region of the human 5-hydroxytryptamine receptor. Chronic administration of the decoy receptor peptide (10 weeks) was safe, well-tolerated and protected against renal glomerulosclerosis in the male ZDF rat.

Introduction

Obesity-associated hypertension is a major risk factor for adverse cardiovascular and renal outcomes in adult type 2 diabetic populations [1,2]. The underlying pathophysiologic mechanisms are complex and may include inflammation, lipotoxicity, and endothelial cell dysfunction as contributory factors [1]. Obesity is thought to drive sympathetic nervous system overactivation in the kidney [3] contributing to hypertension and the development of left ventricular hypertrophy [4]. Left ventricular hypertrophy is a risk factor for heart failure and myocardial infarction which both increase substantially in adult obese, hypertensive type 2 diabetes mellitus [5,6].

Volume and pressure overload cardiac hypertrophy is driven by catecholamines [7] and other hormones (e.g. angiotensin II) which (in the case of alpha 1β adrenergic R) activates Gq/phospholipase C-coupled signaling pathways in cardiac cells [8]. A hallmark feature of classical ligand-G-protein receptor interaction(s) is ligand-occupied receptor desensitization (via phosphorylation) mediated by G-protein coupled receptor kinases (GRKs) [8]. Receptor autoimmunity, on the other hand, is characterized by humoral IgG receptor-targeting autoantibodies (e.g. TSH receptor or beta-adrenergic receptor) that elicit longer-lasting receptor activation underlying various human pathologies such as Graves’ disease [9] or dilated cardiomyopathy, respectively [10]. Recently, we reported that subsets of human diabetic micro-vascular disease, stroke, refractory hypertension and/or chronic kidney disease harbored increased plasma IgG, 5-hydroxytryptamine 2A receptor (5-HT2AR)-targeting autoantibodies that caused long-lasting Gq11/phospholipase C/Ca2+ signaling activation in endothelial cells and in neurons [11-13].

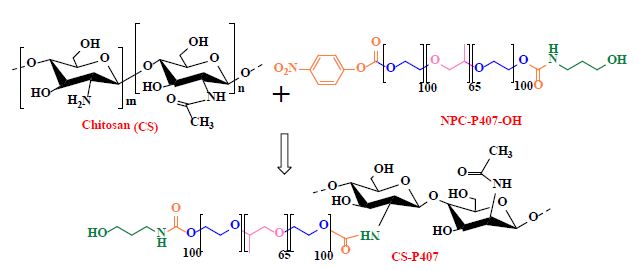

The 5-HT2AR is expressed on arterial vascular smooth muscle cells where it mediates 5-HT induced arterial vasoconstriction [14]. We developed a novel decoy receptor peptide comprised of a subregion of the second extracellular loop of the 5-HT2A receptor involved in mediated long-lasting receptor activation [15]. The decoy receptor peptide, SCLLADDN (Sertuercept) prevented human 5-HT2AR-targeting IgG autoantibodies’ endothelial and neuronal cell toxicity in vitro [13]. The aim of the present study was to test whether the decoy (5HT2A) receptor peptide (Sertuercept) acutely lowers blood pressure in an animal model of obesity-associated hypertension harboring spontaneously-occurring plasma 5-HT2AR agonist autoantibodies [16].

The male Zucker diabetic fatty rat (ZDF) is a well-known genetic model of obese, hypertensive, dyslipidemic type 2 diabetes mellitus [17,18]. In the ZDF rat, agonist plasma 5-HT2AR targeting IgG autoantibodies appeared to develop around the same time as obesity and diabetes and caused persistent Gq11/PLC/Ca2+ signaling in cells [16]. We tested whether chronic administration of active decoy 5HT2A receptor peptide vs. scrambled peptide (for ~10 weeks) might protect against deleterious cardiac hypertrophy or glomerulosclerosis associated with chronic moderate-severe hypertension in the ZDF rat.

Methods

Synthetic Peptides

All synthetic peptides were synthesized at Lifetein Inc. (Hillborough, NJ). The lyophilized peptides were aliquoted and stored (in the presence of dessicant) at -40 degrees C prior to use. On the day of intraperitoneal (IP) administration, an aliquot of lyophilized peptide was reconstituted in sterile saline at the appropriate concentration of 2 mg/kg. Reconstituted peptide was prepared fresh before each injection. Lyophilized peptide was stored for up to 4 weeks (at – 40 deg C) prior to obtaining newly-synthesized peptide needed in chronic drug administration experiments.

Sertuercept (Decoy Receptor Peptide)

A linear synthetic peptide, SCLLADDN, having amino acid sequence identical to that of a fragment of the second extracellular loop region of the human 5-hydroxytryptamine 2A receptor was synthesized and had ≥95% purity.

Scrambled Peptide Sequence LD..8

The scrambled peptide had a sequence of LASNDCLD (LD.8) and a purity of 96.37%, MW 849.91.

Animals

All procedures were conducted according to the National Institutes of Health (NIH) Guide for the Care and Use of Laboratory Animals and approved by the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee of the Veterans Affairs Medical Center (East Orange, New Jersey). Male ZDF and lean (+/?) Zucker rats were obtained from Charles River Laboratories (Kingston, NY) at approximately 6-7 weeks of age. All rats were single housed upon arrival, without enrichment. Rats were acclimatized for two weeks prior to experimental procedures. Rats were provided ad libitum access to food and water and maintained in a 12 h light/dark cycle with lights on at 0630. All procedures occurred during the light phase of the cycle. Blood pressure testing and the effects of chronic peptide administration (for 10 weeks) on cardiac or renal endpoints was conducted in several cohorts of animals.

Cohort 1: Three 25-week-old male ZDF and three, age-matched, male Zucker lean rats(ZLR) treated acutely with IP Sertuercept (ZDF) vs. saline (vehicle) (ZLR).

Cohort 2: 11-week old male ZDF (n=5) and Zucker lean rats (n=4) treated acutely with IP Sertuercept.

Cohort 3: Two groups of 12-week-old male ZDF rats (n=6/group underwent chronic treatment with alternate daily IP, free Sertuercept (2 mg/kg) vs. IP scrambled LD..8 (2 mg/kg) continuously between 13.5-23.5 weeks of age, i.e for 10 weeks. The rats were sacrificed at 25 weeks of age. Body weight was determined immediately before sacrifice and after perfusion. The hearts were excised and weighed for determination of the heart-to-(perfused) body weight ratio.

Cohorts 1 & 3: 25 weeks of age: Rats were anesthetized with xylazine/ketamine prior to undergoing non-survival surgery during which they were perfused with 4% paraformaldehyde in PBS. The kidneys were post-fixed for 24-48 hours in 4% paraformaldehyde and then stored in 70% ethanol at 4 deg C prior to shipment to Histoserve, Inc. (Germantown, MD) where they were sectioned and stained with H&E and Masson’s trichrome. Blood was obtained by cardiac puncture immediately before non-survival surgery for isolation of plasma IgG autoantibodies.

Blood Pressure Monitoring

Tail cuff blood pressure measurement was performed using an automated CODA noninvasive blood pressure system (Kent Scientific, Torrington, CT.). Rats were placed on an insulated warming platform in a well-heated room to ensure proper body temperature. Cuff monitors were provided in different sizes to accommodate rats of different ages and having different body weights. After the animal was positioned in the clear plastic restraint holder, the appropriate-sized cuff was slid over the rat’s tail. The blood pressure system uses volume pressure recording tail-cuff technology and displays up to six blood pressure measurements per cycle.

Renal Histology

Comparisons between untreated male Zucker strain (lean vs. fatty) or male ZDF rats randomized to 10 week’s treatment with (Sertuercept vs. scrambled peptide) were made by Dr. Jerrold M. Ward (veterinary pathologist) using Masson’s trichrome fibrosis score. The fibrosis score ranged from 0-4, where 0 = no fibrosis, 1= minimal fibrosis, 2= mild fibrosis, 3= moderate fibrosis, and 4= severe fibrosis. An individual glomerular score and an interstitial score (for the one kidney examined from each individual rat) was determined separately. The glomerular score consisted of the number of glomeruli affected by fibrosis among 30-40 glomeruli examined per kidney. In addition, the overall glomerular score was divided into two sub-scores: one sub-score each was derived from glomeruli examined in regions unaffected or affected by interstitial fibrosis. Glomeruli affected by fibrosis represents an average of the two individual subscores obtained in 30-40, mean 37.5 glomeruli, examined per kidney. The veterinary pathologist examiner was unaware of the treatment assignment group during examination of histologic sections of rat kidneys. An ‘index of renal fibrosis’ global severity score was comprised of the interstitial fibrosis score (1-4) times the (percent affected glomeruli per kidney x 10).

Protein G Affinity Chromatography

Rat IgG autoantibodies were isolated from 25-week-old male ZDF plasma by protein G affinity chromatography as previously reported [16].

Acute Neurite Retraction Assay

A 1/100th dilution of the protein G eluate of ZDF rat plasma was added to 35 mm dishes containing mouse neuroblastoma (N2A) cells (ATCC, Rockville, MD) cultured in DMEM with 10% fetal calf serum. Acute neurite retraction was determined after 5-10 minutes incubation in the presence of rat IgG autoantibodies as previously reported [16].

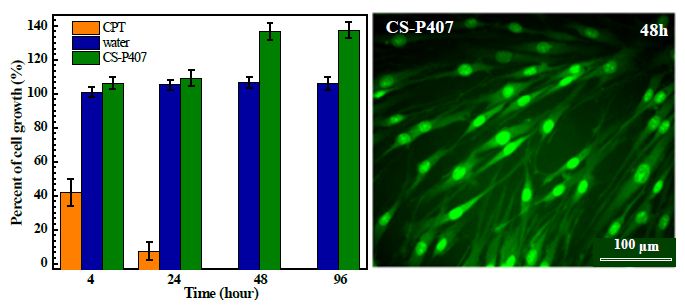

Mouse Neuroblastoma (N2A) Cell Survival Assay

The assay was performed using an MTT assay as previously reported [16].

Urine Albumin/Creatinine Ratio

One day prior to sacrifice, rats were individually housed in metabolic cages for 3-4 hours for collection of urine samples. Thymol was added to urine samples to inhibit bacterial growth and the samples were kept frozen at -40 C prior to determination of albumin and creatinine concentrations. The rat albumin ELISA kit was obtained from Novus Biologics, Inc (Centennial, CO); the creatinine colorimetric assay kit was obtained from Cayman Chemicals, Inc (Ann Arbor, MI).

Statistical Analysis

Comparisons were made using Student’s unpaired t-test.

Results

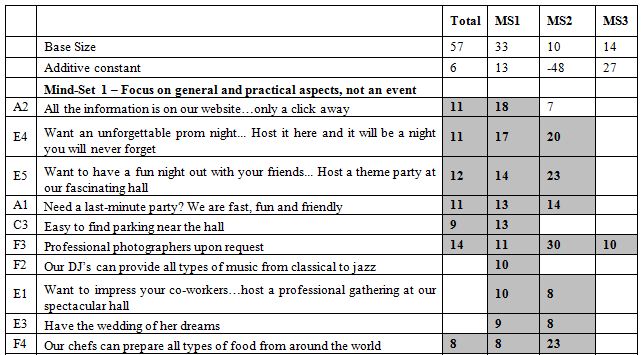

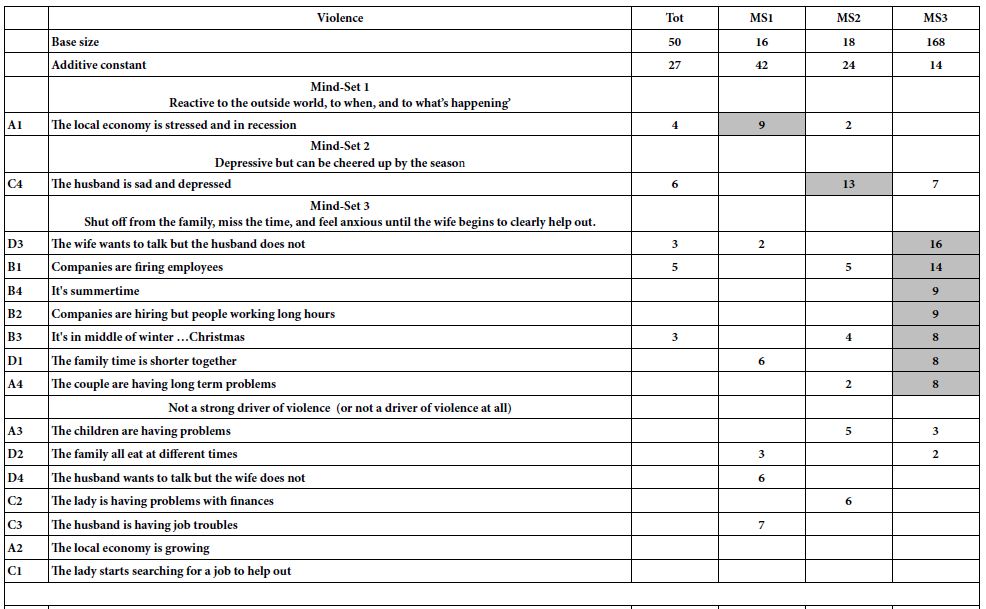

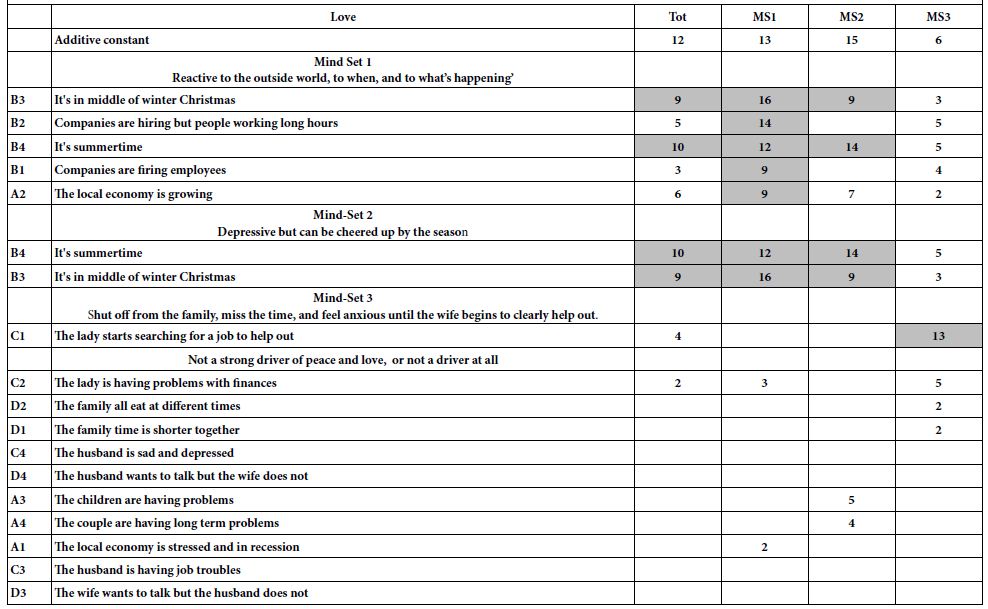

Acute Blood Pressure-lowering Effect of SN..8 Peptide (2 mg/kg IP) in Male ZDF Rats

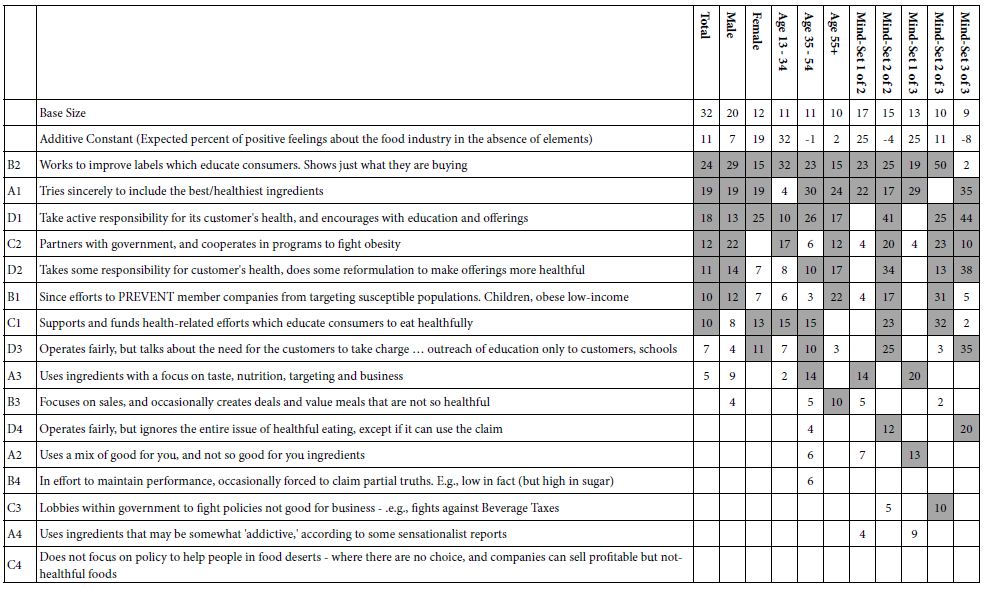

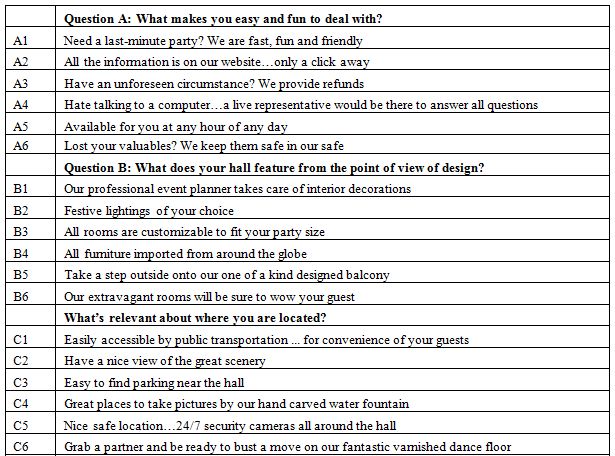

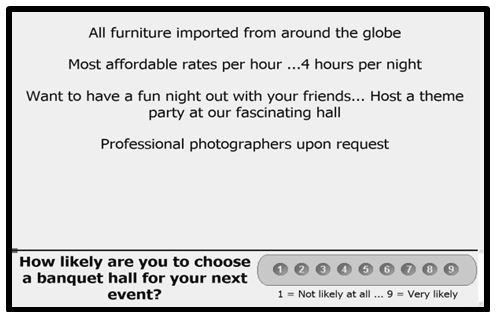

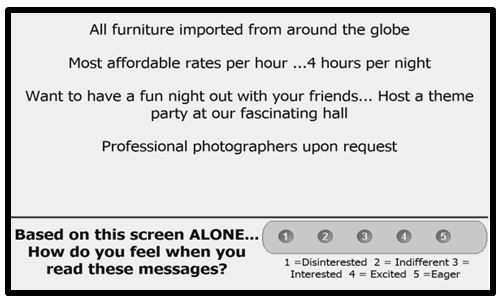

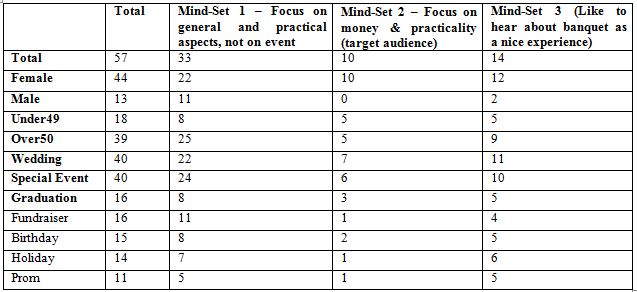

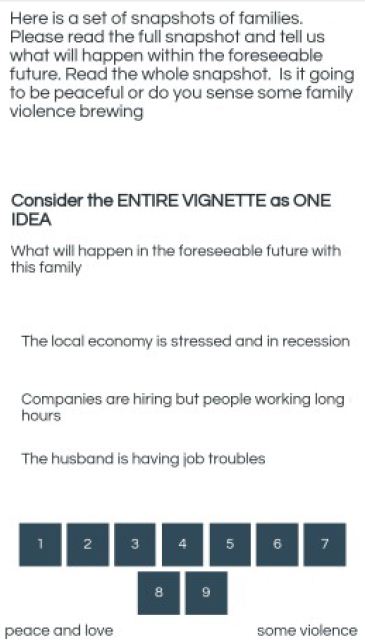

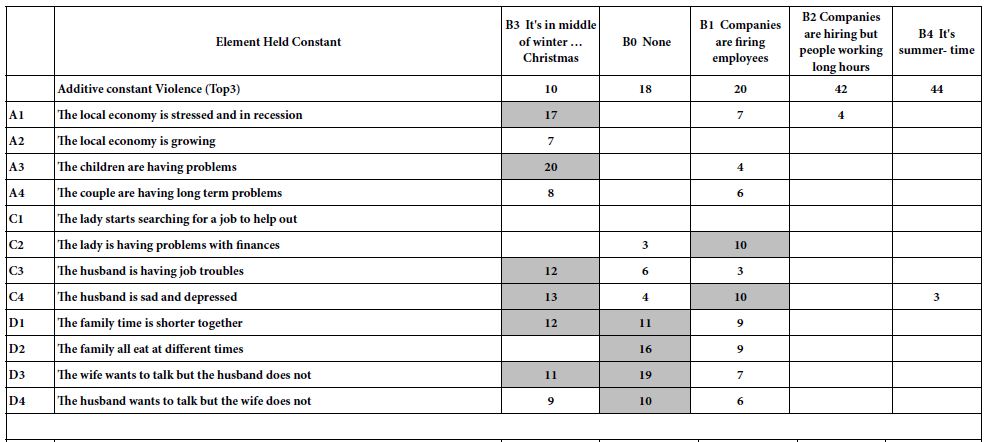

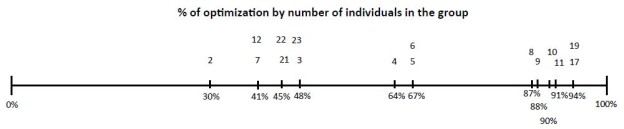

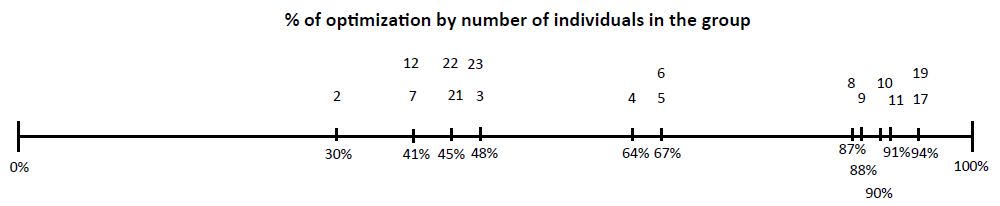

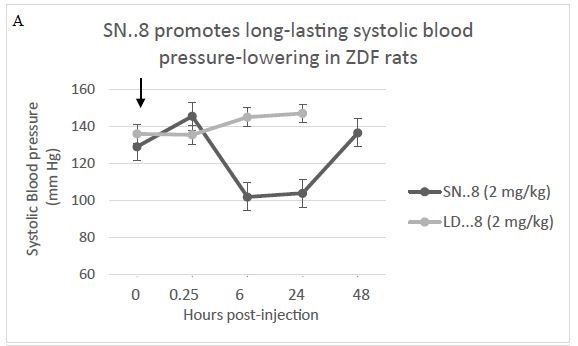

The male ZDF rat spontaneously develops hypertension by age 8-10 weeks, and manifests proteinuric nephropathy by approximately 18 weeks of age [19]. Sertuercept is a linear synthetic peptide having an amino acid sequence SCLLADDN identical to a region of the second extracellular loop of the 5-HT2A receptor involved in mediating long-lasting activation [15]. A single 2 mg/kg IP dose of Sertuercept caused highly significant (41-42%) acute decreases in systolic and diastolic blood pressure in three 25-week-old male ZDF rats tested, rats that were naïve to prior drug exposure (Table 1). The onset of acute blood pressure-lowering occurred between 15-40 minutes following IP drug injection. In two of three rats tested, IP Sertuercept administration caused sedation and borderline hypotension both of which resolved spontaneously after approximately ten minutes. Rechallenge (1 week later) with a single IP (2 mg/kg) dose of Sertuercept caused reproducibly large drops in systolic and diastolic blood pressure which were sustained for 4 hours or longer (Figure 1). There were no untoward acute or long-term side effects observed for up to 18 days following the repeat drug exposure. Taken together these data demonstrate that a single 2 mg/kg intraperitoneal injection of the peptide SCLLADDN (dissolved in sterile isotonic saline) causes acute substantial lowering of systolic, diastolic and mean arterial blood pressure in the older adult 25-week-old, hypertensive Zucker diabetic fatty rat.

Table 1: Change in systolic blood pressure in 25-week-old male ZDF rats before and after peptide SCLLADDN injection.

|

Systolic blood pressure |

||||

| Animals | Day-2. | Day 0, pre-injection | 15-40 mins post-injection. |

P-value* |

|

ZDF 1-3 |

166 + 24 | 161 + 21 | 95 + 13 |

0.018 |

|

DIASTOLIC BLOOD PRESSURE |

||||

| ZDF 1-3 | 101 + 23 | 112 + 2 | 65 + 11 |

0.05 |

Percent lowering of systolic blood pressure after peptide (161-95)/161 = 41.

Percent lowering of diastolic blood pressure after peptide (112-65)/112 = 42.

Percent lowering of mean arterial pressure (125-75)/125 =40.

Results are mean mm Hg ± SD in three, obese male Zucker diabetic fatty rats (25-weeksold),

average weight approximately 500g who had blood pressure monitored two days before, 30 minutes before and then 15-40 minutes after receiving 2 mg/kg intraperitoneal injection of the linear synthetic peptide SCLLADDN in sterile saline.

*P-value is comparing mean systolic or diastolic blood pressure immediately before and

after the peptide injection.

Figure 1: A single intraperitoneal dose of Sertuercept (2 mg/kg) acutely lowered systolic (A) and diastolic blood pressure (B) in the Zucker diabetic fatty rat. Each point represents the mean ± SEM values in two-three, 25-week-old male ZDF rats.

Acute Effect of IP Administration of Saline in Older Male Zucker Lean Rats

Age-matched male Zucker lean rats do not manifest diabetes, obesity or hypertension when fed the same diet as ZDF rats. Baseline mean systolic and diastolic blood pressure was in the normal range in 25-week-old male ZLR rats (N=3), and it did not change significantly following IP administration of 0.5 mL vehicle (sterile saline) in each rat (Table 2).

Table 2: Effect of saline injection on systolic blood pressure in Zucker lean, non-obese rats (ZLR).

|

Systolic blood pressure |

||||

| Animals | Day-2. | Day 0, pre-injection | 15-40 mins post-injection. |

P-value* |

|

ZDF 1-3 |

166 + 24 | 161 + 21 | 95 + 13 | 0.018 |

|

DIASTOLIC BLOOD PRESSURE |

||||

|

ZDF 1-3 |

101 + 23 | 112 + 2 | 65 + 11 |

0.05 |

Intraperitoneal injection of 0.5 mL of sterile saline had no significant effect on diastolic blood pressure in three Zucker lean male rats, 25-weeks-old.

*P-value comparing mean systolic and diastolic blood pressure before and after saline injection.

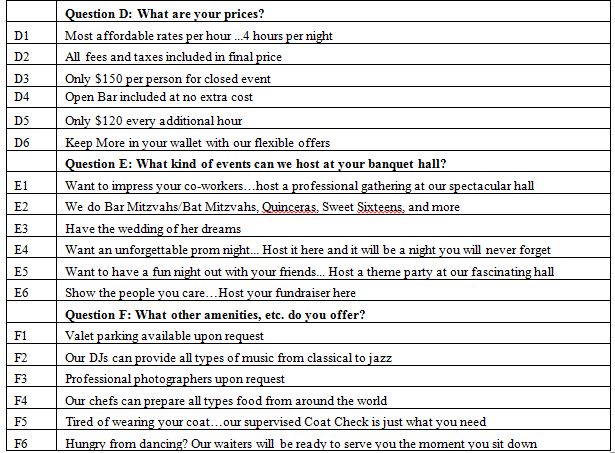

Acute Effect of Sertuercept in Younger Male ZDF and Zucker Lean Rats

We next tested a 2 mg/kg IP dose of Sertuercept in 11-week-old male ZDF rats (N=5), and age-matched male Zucker lean rats (N=4). Sertuercept caused acute significant mean systolic and diastolic blood pressure-lowering (19-23%) in five of five 11-week-old male ZDF rats tested (Table 3). Acute blood pressure-lowering was well-tolerated; none of the five male ZDF rats experienced any untoward side effects including hypotension or acute sedation.

Table 3: Acute blood pressure- lowering effect of SN..8 in 11-week-old male ZDF rats.

|

Systolic blood pressure |

|||

| Animals | Before | 15-45 mins post-injection |

P-value* |

|

ZDF (N=5) |

167 ± 24 (N=10) | 135 /-+ 18 (N=17) | 0.0004 |

|

Diastolic blood pressure |

|||

|

ZDF (N=5) |

118 + 22 (N=10) | 91 + 15 (N=17) |

0.002 |

Results are mean ± SD.

Mean acute SBP-lowering (167-135)/167 = 19%.

Mean acute DBP-lowering (118-91)/118 = 23%

Mean acute MAP-lowering (134-106)/134 = 21%.

*P-value: comparing mean systolic or diastolic blood pressure before and after IP injection

of 2 mg/kg dose of Sertuercept (SN..8).

Three of four, 11-week-old Zucker lean rats tested had normal blood pressure at baseline and Sertuercept (2 mg/kg IP) did not significantly alter blood pressure acutely in normotensive rats (Table 4). In one of four Zucker lean rats that manifested baseline hypertension, a single dose of Sertuercept (2 mg/kg IP) acutely lowered systolic and diastolic blood pressure to statistically significantly lower levels compared to baseline (Table 4). These data suggest that 2 mg/kg IP Sertuercept effectively lowers blood pressure in both young and older male ZDF rats and in a subset of hypertensive Zucker lean rats.

Table 4: Acute effect of Sertuercept on blood pressure in 11-week-old male Zucker lean rats.

| Blood pressure | |||

|

Before injection |

30 minutes after injection |

P-value* |

|

| Zucker lean #1 |

130/72 |

120/78 |

NS |

| Zucker lean #2 |

124/80 |

122/83 |

NS |

| Zucker lean #3 |

130/85 |

132/98 |

NS |

| Zucker lean #4 |

149/102 (N=6) |

130/91 (N=4) |

<0.05 |

*P-value comparing mean blood pressure before and after IP injection of 2 mg/kg Sertuercept.

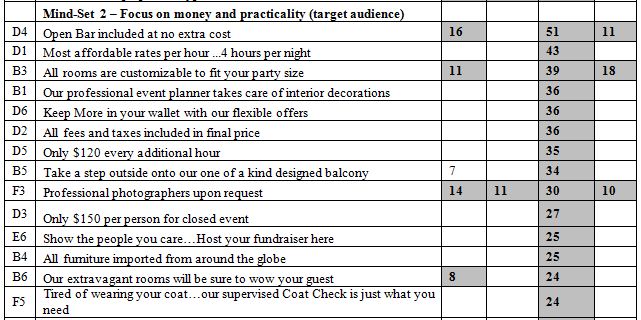

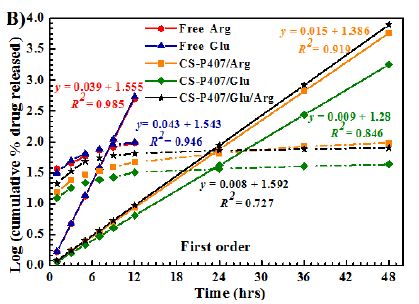

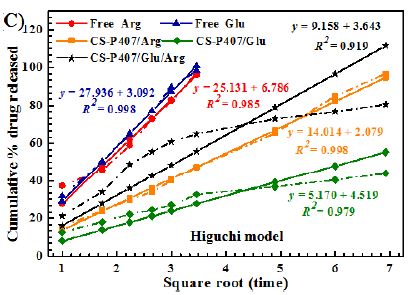

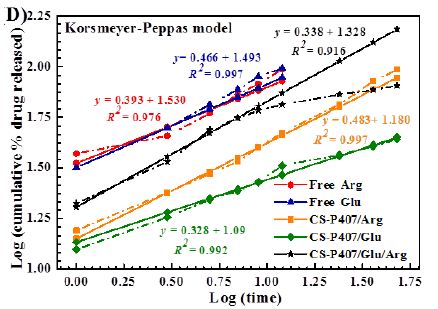

Sustained Blood Pressure Lowering Effect of Sertuercept in Adult Male ZDF Rat

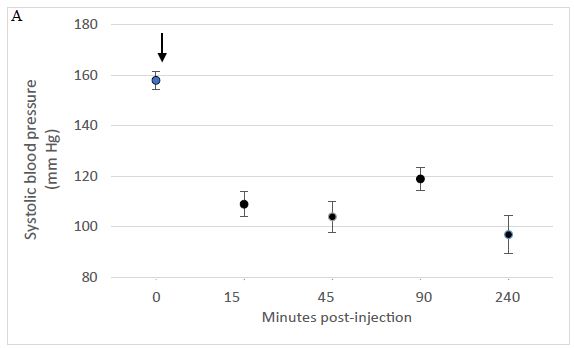

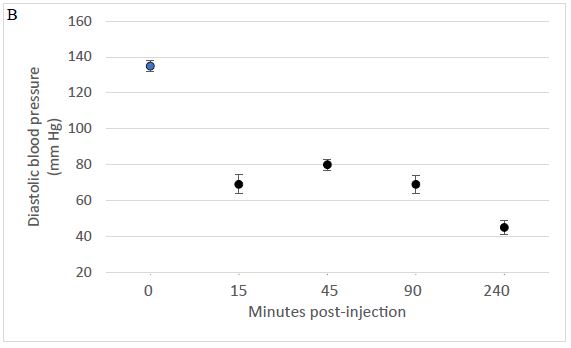

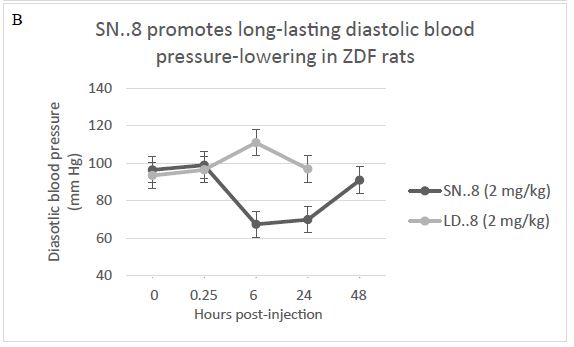

The duration of Sertuercept’s blood pressure-lowering action was evaluated in 25-week-old male ZDF rats (N=3) administered a single IP 2 mg/kg dose. The control group were age matched male ZDF rats (N=3) who received 2 mg/kg IP administration of LD..8, a scrambled peptide sequence comprised of the same eight amino acids as in Sertuercept arranged in a random order. Sertuercept caused 25-30% significant systolic and diastolic blood pressure-lowering which was sustained for 24 hours or longer (Figure 2A). Blood pressure returned to baseline elevated levels 48 hours after Sertuercept administration (Figure 2A). The scrambled peptide LD.8 sequence (2 mg/kg IP) had no significant systolic or diastolic blood pressure-lowering effect at time points up to 24 hours (Figure 2B). These data suggest that a single 2 mg/kg Sertuercept dose (but not a scrambled peptide having the same amino acids) promotes relatively long-lasting significant systolic and diastolic blood pressure-lowering in adult hypertensive male ZDF rats.

Figure 2: Sertuercept (SN..8) (2 mg/kg) single intraperitoneal injection caused long-lasting systolic (A) and diastolic blood pressure-lowering (B) in 25-week- old male ZDF rats. Each point represents the mean ± SEM values as described in Materials and Methods.

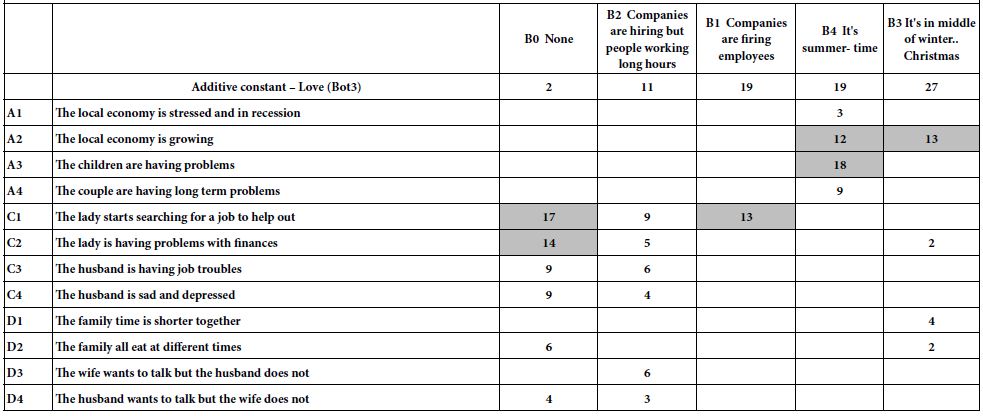

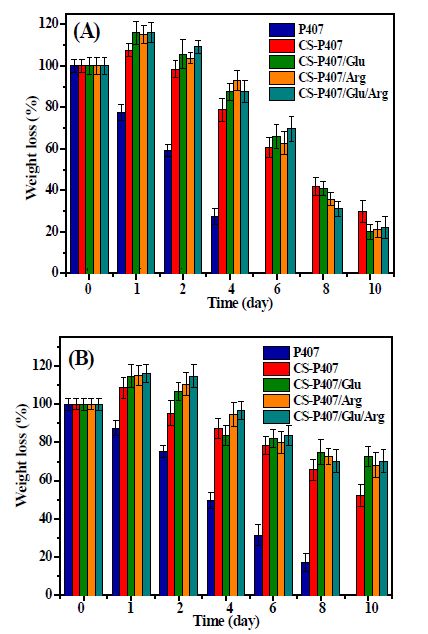

Cardio-protective Effect of Chronic Administration of Sertuercept in Male ZDF Rats

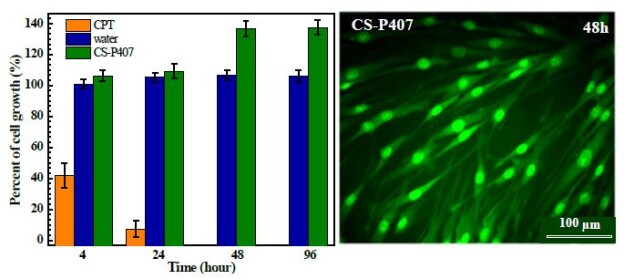

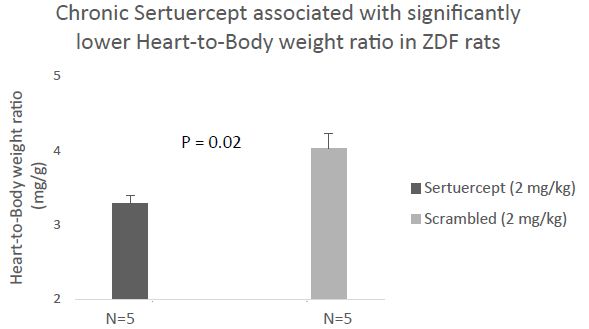

Two groups of 13.5-week-old male Zucker fatty rats (n=6/group) having matching baseline mean capillary glucose concentration and body weight (Table 5), were randomly assigned to chronic 10 weeks’ treatment (between 13.5 and 23.5-weeks of age) with either alternative daily Sertuercept (2 mg/kg) or an identical 2 mg/kg concentration of LD..8 scrambled peptide. These animals were part of a neuroprotection experiment and at 14-weeks of age, half in each drug treatment group (n=3) experienced mild traumatic brain injury (via lateral fluid percussion) or sham injury. One rat in each drug assignment group (assigned to mild traumatic brain injury) failed to gain significant weight post-injury and was excluded from the analysis. In the remaining 10 rats (n=5/peptide drug group) 10 weeks’ IP treatment with Sertuercept was associated with a significantly lower mean heart-to-body weight ratio (3.3 mg/g vs. 4.0 mg/g; P =0.02, Figure 3) compared to scrambled peptide treatment. These data suggest that 10 weeks’ alternate daily IP administration of Sertuercept (2 mg/kg) may have reduced the development of cardiac hypertrophy – a serious long-term complication of moderate, uncontrolled hypertension.

Table 5: Baseline characteristics in 13-week-old ZDF rats before chronic peptide administration.

|

Scrambled peptide (N=6) |

Sertuercept (N=6) |

P-value |

|

| Body weight (g) |

374.2 ± 24.7 |

385.8 ± 34.2 |

0.55 |

| Capillary glucose (mg/dL) |

442 ± 54 |

381 ± 120 |

0.32 |

Results are mean ± SD. Capillary glucose concentration was determined by tail nick method as previously reported [16].

Ten weeks treatment of male ZDF rats with alternate daily SN..8 (2 mg/kg) (vs. scrambled peptide) was associated with significantly lower heart-to-body weight ratio.

Figure 3: Chronic administration of alternate daily intraperitoneal Sertuercept (2 mg/kg) was associated with significantly lower heart-to-body weight ratio than in baseline matched ZDF rats treated with IP scrambled LD.8 peptide (2 mg/kg). Results are mean ± SEM.

Reno-protective Effect of Chronic Administration of Sertuercept in Male ZDF Rats

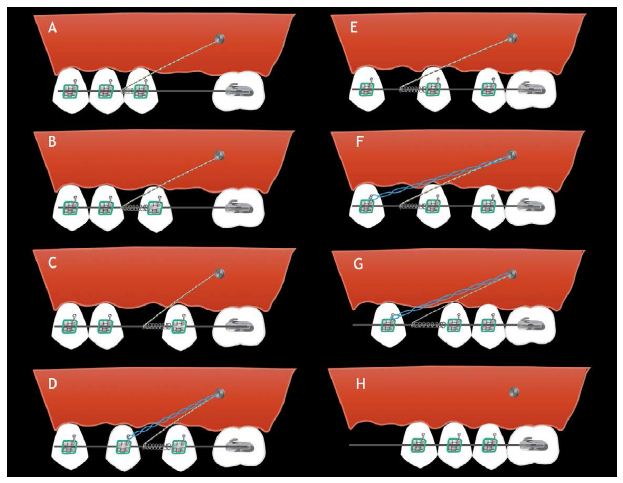

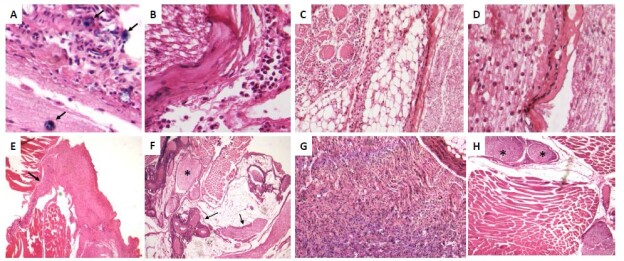

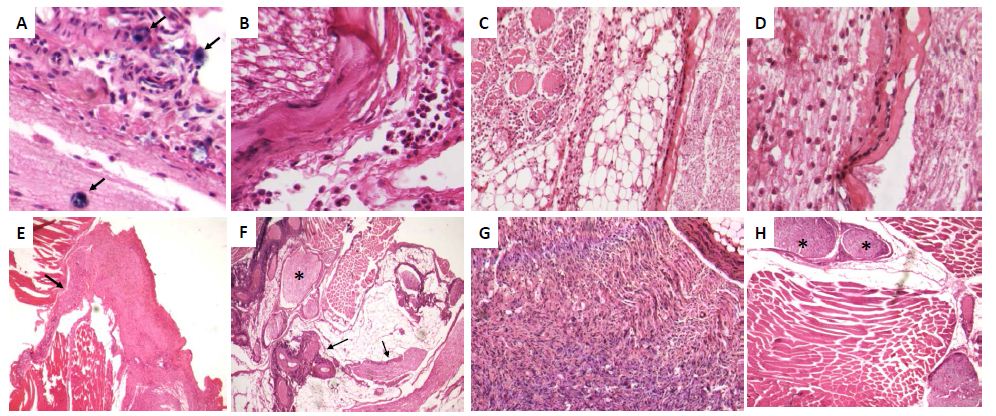

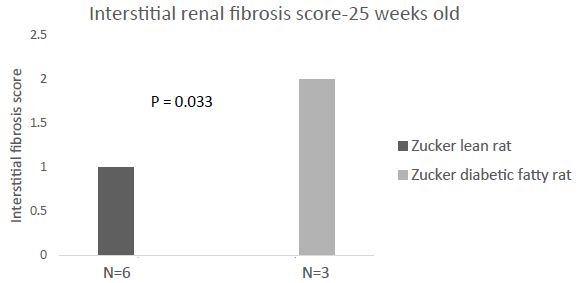

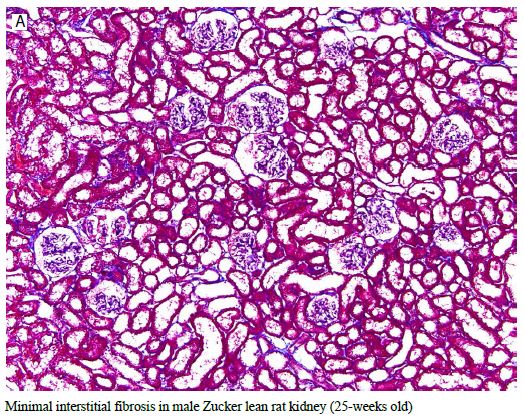

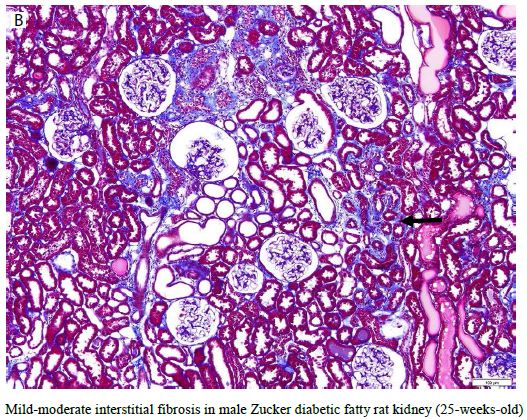

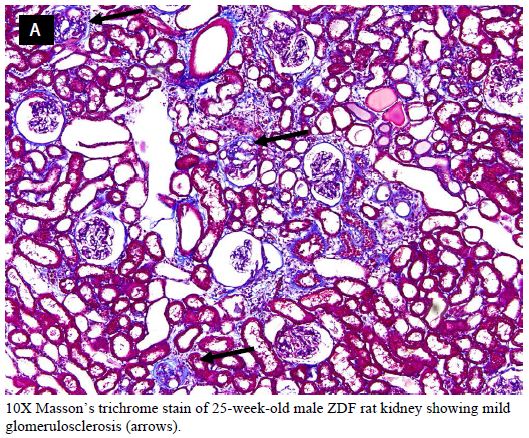

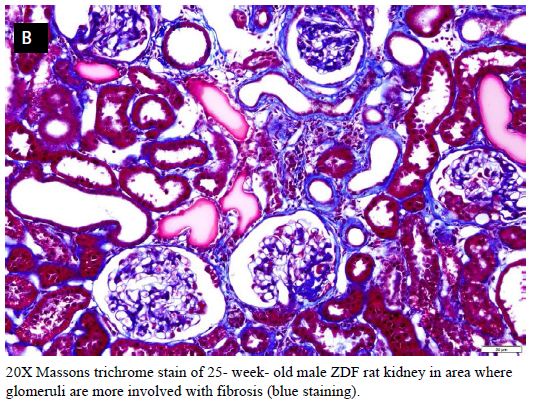

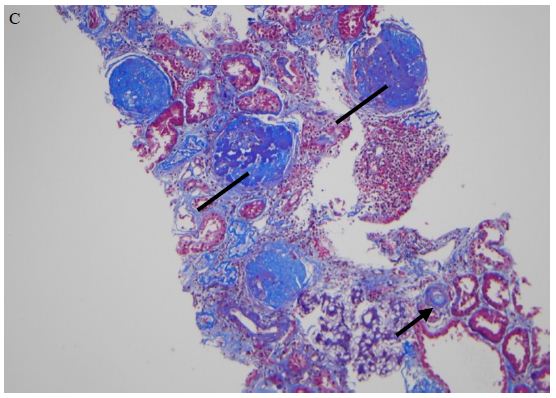

Interstitial renal fibrosis occurs spontaneously in male Zucker diabetic fatty rats. In two groups of untreated male Zucker diabetic fatty or lean rats, Masson’s trichrome stain of kidney sections was used as an indicator of severity of interstitial renal fibrosis. There was a significantly greater degree of interstitial renal fibrosis in the twenty-five-week-old male ZDF rat compared to age-matched male Zucker lean rats (Figures 4, 5a and 5b). Interstitial fibrosis is the most important renal lesion in male ZDF rats. It can be present as early as 5 months of age in some male ZDF rats, but in other rats may take a considerably longer time (8-12 months) to develop. In twelve male ZDF rats who were randomized to 10 weeks’ treatment with either Sertuercept or scrambled peptide, one rat in each treatment group was excluded from the analysis because of inherent ‘fast progression’ to renal fibrosis. In the remaining ten rats, male ZDF rats treated for 10 weeks with Sertuercept (vs. scrambled peptide) manifested a significantly lower percentage of glomeruli affected by fibrosis (10% vs. 21.5%; P = 0.03; Figure 6). Representative images of 25-week-old male ZDF rat kidney sections in which glomeruli are affected by fibrosis are shown in Figure 7A and 7B. The pattern of fibrosis is consistent with focal segmental glomerulosclerosis. Glomerular changes associated with collagen deposition in the rat glomeruli included: loss of normal glomerular structure, obliteration of capillaries, increased mesangium, adhesion to Bowman’s capsule and periglomerular fibrosis (Figure 7). Vascular lesions were not easily seen, and there was only minimal interstitial inflammation (not shown in Figure 7).

Untreated twenty-five- week old male Zucker diabetic fatty rats experience significantly greater interstitial renal fibrosis compared to age-matched, untreated male Zucker lean rats.

Figure 4: Male Zucker diabetes fatty rats (N=3) or Zucker lean rats (N=6) who did not receive chronic administration of blood-pressure lowering or control peptide(s) were sacrificed at 25-weeks of age for renal histopathologic examination. Interstitial renal fibrosis-the most important indicator of renal disease in the male ZDF rat was significantly increased compared to age matched male Zucker lean rat.

Figure 5: Representative 10X Massons trichrome stain of kidney from age-matched, 25-week-old Zucker lean (A) or Zucker diabetic fatty rat (B) showing lack of interstitial fibrosis in Zucker lean strain compared to mild interstitial fibrosis (blue staining, arrow) in ZDF rat kidney.

Ten weeks continuous treatment with alternate daily SN..8 (mg/kg) (vs. scrambled Peptide) was associated with significantly less glomerular fibrosis (sclerosis) in 25-week old male ZDF rat.

Figure 6: Chronic administration of alternate daily intraperitoneal Sertuercept (2 mg/kg) was associated with significantly less glomerular sclerosis (fibrosis) than in baseline matched ZDF rats treated with IP scrambled LD.8 peptide (2 mg/kg). Results are mean ± SEM.

Figure 7: Representative 10X (A) and 20X (B) Massons trichrome stain of kidney from a 25-week-old ZDF rat affected by mild glomerular fibrosis (blue staining, arrows).

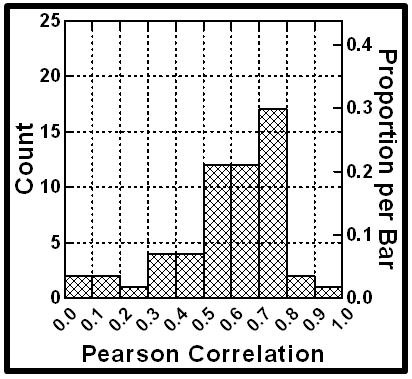

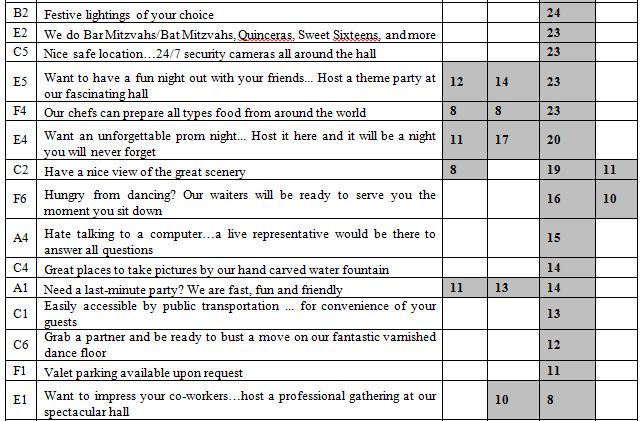

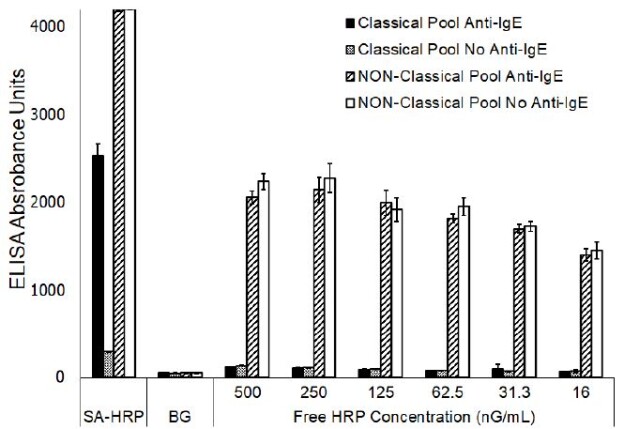

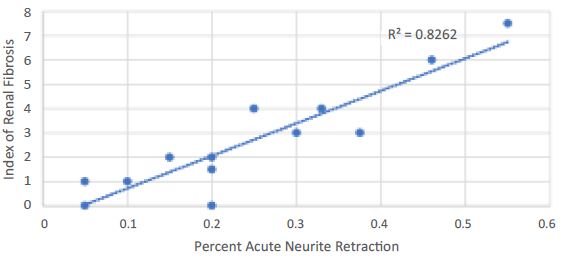

In the ZDF rat, plasma IgG autoantibodies were previously reported to cause dose-dependent acute neurite retraction in mouse N2A cells downstream of 5-HT2A receptor-mediated PLC/IP3/Ca2+ and RhoA/Rho kinase signaling pathways activation [16]. Here we tested whether plasma autoantibody neurotoxicity (a marker of long-lasting 5-HT2AR activation) was correlated with increased global renal fibrosis (interstitial and glomerular) in 13 male ZDF rats, 5 treated and 8 others not treated with the decoy receptor peptide. There was a statistically significant overall correlation between ZDF rat plasma autoantibody neurotoxicity and increased global renal fibrosis index in the male ZDF rats (Figure 8). Mean urine albumin/creatinine excretion ratio did not differ significantly in 25-week-old ZDF rats who were matched for baseline body weight and glucose concentration prior to assignment to 10 weeks’ alternate daily treatment with Sertuercept vs. scrambled peptide [0.826 ± 0.527 g/g (N=5) vs. 0.818 ± 0.391 g/g (N=6); P =0.98)].

Index of renal fibrosis global severity in 25-week-old male ZDF rats is linearly significantly correlated with plasma autoantibody serotonin 2A receptor bioactivity.

Figure 8: Index of renal fibrosis global severity was linearly, significantly correlated with neurotoxicity in plasma (obtained at the time of sacrifice) autoantibodies isolated from the same rats. A 1/100th dilution of ZDF rat autoantibodies was incubated with mouse N2A cells for 5-10 minutes. Acute neurite retraction was determined as described in Material and Methods. Results on acute neurite retraction were compared to global renal fibrosis severity score obtained from histologic examination of the kidney from the same ZDF rats.

Taken together these data suggest that plasma autoantibodies which activate PLC/IP3/Ca2+ signaling leading to acute neurite retraction may contribute (in part) to renal fibrosis which is the most important renal lesion in the ZDF rat. Although the precise mechanism is unknown, Sertuercept may afford renoprotection in part by interfering with autoantibody-induced long-lasting 5-HT2A receptor activation coupled to PLC/IP3/Ca2+ signaling activation in renal glomerular cells.

Discussion

Chronic hypertension is a significant risk factor for the later occurrence of adverse cerebrovascular, cardiovascular and renal outcomes in humans [20-22]. Hypertension, diabetes, and obesity each increases the risk of heart failure occurrence in humans [23]. The global prevalence(s) of aging, obesity and diabetes is expected to increase over the next several decades driving further increase in the global prevalence of obesity-associated hypertension [24].

In the 2015 Global Burden of Disease Study, systolic blood pressure was the leading risk factor accounting for the largest number of global deaths and disability-adjusted life years [24]. In a systematic review and meta-analysis of the cardiovascular effect of blood pressure-lowering, every 10 mm Hg reduction in systolic blood pressure was associated with significant reductions in the risks for major cardiovascular events, coronary heart disease, stroke, heart failure and all-cause mortality [25]. In high risk patients without diabetes (SPRINT), intensive vs. standard blood pressure-lowering was associated with substantially lower rates of cardiovascular death and all-cause mortality [26].

Long-term adherence to anti-hypertensive medication regimen is critical in reducing cardiovascular event occurrence and mortality risk [27]. Yet few once-daily, long-acting anti-hypertensive medications achieved sustain substantial blood pressure-lowering over 24 hours.

For example, in a study comparing valsartan and long-acting amlodipine, four-fold escalation of the initial starting dose of each medication, i.e. valsartan (40 to 160 mg) and amlodipine (2.5 to 10 mg) was undertaken. Even then, once-daily long-acting amlodipine (10 mg) caused a 10% reduction in systolic blood pressure and once-daily valsartan (160 mg) had no significant systolic blood pressure-lowering effect after 24 hours [28]. Single IP administration of (2 mg/kg) Sertuercept caused 19-27% reductions in systolic and diastolic blood pressure after 24 hours.

Sustained, substantial blood pressure-lowering by Sertuercept could lead to improved medication adherence, and perhaps be useful in the treatment of acute severe hypertension (in the emergency room) by obviating the need for costly, hospitalization. Sertuercept was generally well-tolerated except at the highest doses tested (2.5 mg/kg or slightly higher) at which dose a few animals experienced brief somnolence likely secondary to spontaneously-reversible hypotension.

Our observation that ten weeks’ alternate daily chronic IP treatment with Sertuercept (2 mg/kg) vs. scrambled peptide (2 mg/kg) resulted in significantly lower heart-to-body weight ratio (in male ZDF rats matched for diabetes and obesity) suggests Sertuercept may be cardioprotective perhaps in part via a sustained blood pressure-lowering, i.e. hemodynamic, effect. Chronic administration (for 10 weeks) of Sertuercept (2 mg/kg) in the same cohort of rats was associated with significantly less glomerulosclerosis compared to age-matched male ZDF rats treated with an identical concentration of scrambled peptide sequence.

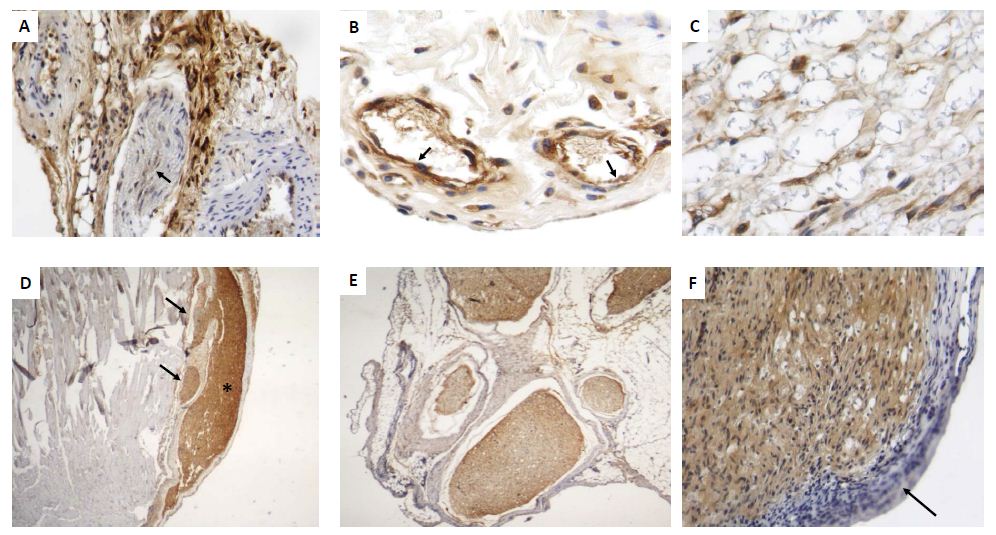

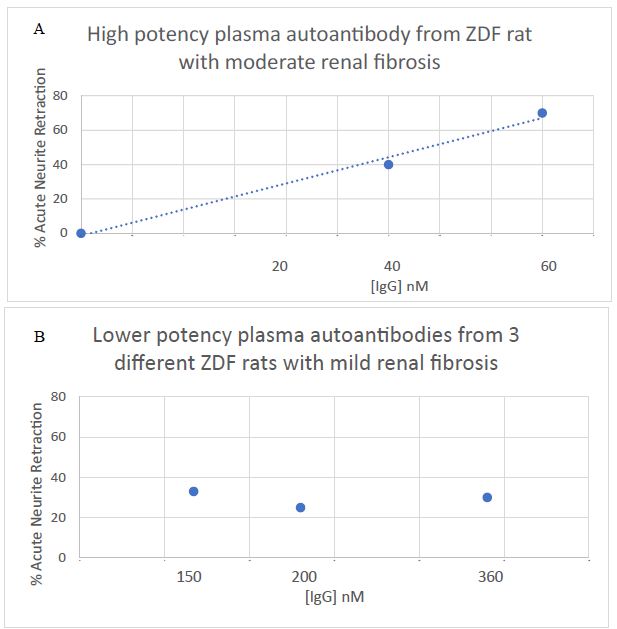

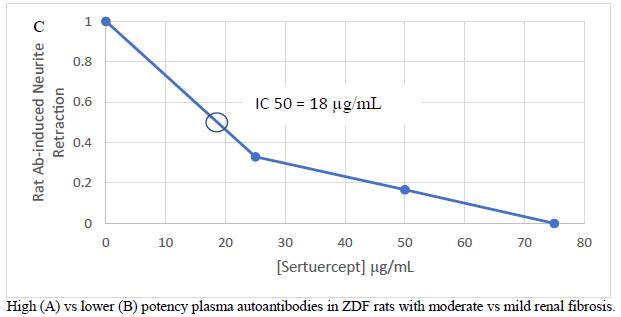

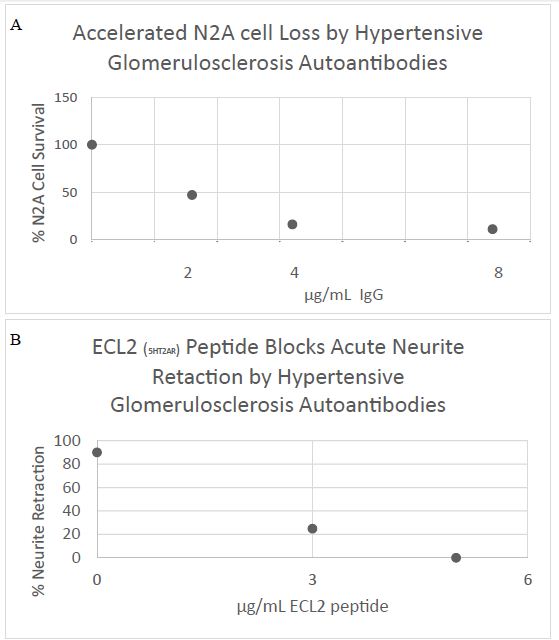

“It is of interest that the global severity of renal fibrosis index in the male ZDF rat was correlated significantly with plasma autoantibody neurotoxicity, neurotoxicity shown previously to be mediated via 5-HT2A receptor positively coupled to PLC/IP3/Ca2+ and RhoA/Rho kinase signaling pathways activation [16]. Plasma IgG from a male ZDF rat that experienced early progression to moderate renal fibrosis (Fig 9A) displayed five-seven- fold greater potency (in neurite retraction assay) compared to IgG in three age-matched male ZDF rats who experienced only mild- minimal renal fibrosis at 25-weeks of age (Fig 9B). Rat IgG autoantibody-induced acute neurite retraction was dose-dependently inhibited (IC50 = 18 ug/mL) by co-incubation with Sertuercept (Fig 9C), a peptide comprising a sub-region of the second extracellular loop of the human 5-HT2AR located near the orthosteric binding pocket [15] and which normally functions to prevent constitutive receptor activation.

Figure 9: Marked difference in potency of acute neurite retraction in mouse N2A cells induced by autoantibodies from A) a 25-week-old male ZDF rat having moderate global renal fibrosis index or B) three 25-week old male ZDF rats, each having mild global renal fibrosis index C) dose-dependent inhibition of bioactivity by Sertuercept (SN..8).

In a prior report, ZDF rat plasma autoantibodies displayed increased binding (in an ELISA) to a linear synthetic peptide corresponding to the second extracellular loop region of the human 5-HT2A receptor [16]. The 5-HT2A receptor peptide binding autoantibodies first appear in the male ZDF rat plasma around 8.5 weeks of age and persist in the circulation until at least 30 weeks of age [16]. In addition to their presence in plasma during the period of development of renal fibrosis, we used protein G affinity chromatography to recover autoantibody from urine in a subset of male ZDF rats that also displayed increased binding in the 5-HT2A receptor ELISA.

Proteinuria is a leading risk factor for chronic kidney disease progression, however, residual risk for disease progression is substantial and may be mediated in part by additional factors associated with chronic inflammation and immune dysregulation. One such factor may be autoantibodies which target receptors expressed on cells in the renal glomerulus. Identification of the relevant target receptors may lead to novel therapies to reduce residual risk for CKD progression.

In 15 of 20 older adults with chronic kidney disease previously tested (including diabetic and hypertensive nephropathy) plasma IgG displayed mean 3-fold increased binding (vs. background) to a linear synthetic peptide corresponding to the second extracellular loop of the human 5-HT2A receptor. [13]. In one such patient having biopsy-proven hypertensive glomerulosclerosis which progressed to end-stage-renal disease (Fig 10), Gq11/IP3-mediated neurotoxicity in the plasma autoantibodies was dose-dependently inhibited by co-incubation of N2A cells with low microgram per milliliter concentrations of the second extracellular loop region 5-HT2AR peptide (Fig 10). Co-incubation of the patient’s autoantibodies (100 nM) with a 20 ug/mL concentration of Sertuercept nearly completely prevented (95%) IP3-mediated acute neurite retraction (in vitro) [13]. A 2 mg/kg IP dose of Sertuercept is expected to result in a plasma concentration of roughly 30 ug/mL in the ZDF rat, i.e. sufficient concentration to neutralize the bioactivity in moderately potent 5-HT2AR targeting autoantibodies.”

Figure 10: Human hypertensive glomerulosclerosis plasma IgG autoantibody caused A) dose-dependent inhibition of mouse neuroblastoma cell survival (MTT assay) and B) acute neurite retraction in mouse N2A cells which was prevented by co-incubation with low microgram per milliliter concentrations of a linear synthetic peptide having identical amino acid sequence as the second extracellular loop (ECL2) of the human 5-HT2AR C) 10X Masson’s trichrome stain of renal biopsy specimen showing global and segmental glomerulosclerosis (lines) and hyaline arteriolosclerosis (arrow).

The 5-HT2A receptor is expressed on renal mesangial cells where it promotes protein kinase C/MAPK/ERK signaling pathway activation and increased transforming growth factor-beta expression which promotes renal fibrosis and scarring [29]. Prior studies from a number of different laboratories reported reno-protective effects from various 5-HT2A receptor antagonists in animal models of CKD or in humans [30].

The mechanism of action of Sertuercept is not known, but it may differ from other 5-HT2A receptor antagonists. In a recent report, brief exposure of neuroblastoma cells to active, human diabetic 5-HT2AR targeting autoantibodies resulted in significant downregulation of mRNA expression in the G protein-coupled receptor kinase 3 gene (GRK3) [31].

G-protein receptor kinases are a family of serine-threonine kinases which are activated by certain ligand occupied G-protein coupled receptors causing phosphorylation of the GPCR and directing arrestin-mediated receptor desensitization [8]. G-protein receptor kinase 3 has an in vivo substrate specificity for ligand occupied-alpha-1B adrenergic receptor [8] which mediates norepinephrine-induced blood pressure elevation or the ionotropic effect of epinephrine and norepinephrine in cardiac muscle. In a recent study [8], transgenic mice harboring a cardiac specific, constitutively-active mutant alpha1b adrenergic receptor developed cardiac hypertrophy which could be prevented by simultaneous cardiac overexpression of GRK3.

One possible mechanism of action of Sertuercept may be preventing downregulation of GRK mRNA expression by agonist 5-HT2AR autoantibodies thereby restoring normal level of GRK3 mRNA expression in vascular tissues expressing both 5-HT2AR and alpha-1 adrenergic receptor.

Of interest, GRK3 mRNA expression in human lymphocytes was reported to be inversely associated with systolic and diastolic blood pressure [32] perhaps consistent with a regulatory role for GRK3 gene expression in the maintenance of normal blood pressure in humans.

In summary, the decoy 5-HT2A receptor peptide (SCLLADDN) which is identical to a second extracellular loop subregion implicating in promoting long-lasting receptor activation, caused acute and relatively long-lasting significant systolic and diastolic blood pressure-lowering in the Zucker hypertensive diabetic fatty rat. There were no untoward long-term side effects after chronic (10 weeks’) administration, and early data suggested chronic blood pressure-lowering may have been reno-protective and cardioprotective in a small cohort of rats matched for baseline diabetes severity and obesity.

Acknowledgments

Mihal Grinberg and Julia Burton for expert technical assistance. The study was supported by grants from the Department of Veterans Affairs Technology Transfer Program/BLRD (ORD, Washington, DC) and a grant from the New Jersey Commission on Brain Injury Research (Trenton, New Jersey). The views expressed in this article are solely those of the author and do not necessarily represent the position or policy of the Department of Veterans Affairs or the United States Government.

Disclosure

Dr. Zimering is the Inventor on a pending patent assigned to the United States Government pertaining to results presented herein.

References

- Landsberg L, Aronne LJ, Beilin LJ, Burke V, Igel LI, Lloyd-Jones D, Sowers J (2013) Obesity-related hypertension: pathogenesis, cardiovascular risk, and treatment–a position paper of the Obesity Society and The American Society of Hypertension. Obesity (Silver Spring) 21(1): 8-24. [crossref]

- Hall J, Kuo J, daSilva A, DePaula R, Liu J, Tallam L (2003) Obesity associated hypertension and kidney disease. Curr Opin Nephrol Hypertens 12: 195-200. [crossref]

- Esler M, Rumantir M, Wiesner G, Kaye D, Hastings J, Lambert G (2001) Sympathetic nervous system and insulin resistance: from obesity to diabetes. Am J Hypertens 14(11 Pt 2): 304S-309S. [crossref]

- Woodiwiss A.J. Norton G.R. (2015) Obesity and left ventricular hypertrophy: The hypertension connection. Hypertens Rep 17: 539. [crossref]

- Kenny HC, Abel ED (2019) Heart Failure in Type 2 Diabetes Mellitus. Circ Res 124(1): 121-141. [crossref]

- Adlerberth AM, Rosengren A, Wilhelmsen L (1998) Diabetes and long-term risk of mortality from coronary and other causes in middle-aged Swedish men: a general population study. Diabetes Care 21: 539-545. [crossref]

- Rossi MA, Carillo SV (1991) Cardiac hypertrophy due to pressure and volume overload: distinctly different biological phenomena? Int J Cardiol 31(2): 133-141. [crossref]

- Eckhart AD, Duncan SJ, Penn RB, Benovic JL, Lefkowitz RJ, Koch WJ (2000) Hybrid transgenic mice reveal in vivo specificity of G protein-coupled receptor kinases in the heart. Circ Res 86(1): 43-50. [crossref]

- Adams DD (1988) Long-acting thyroid stimulator: how receptor autoimmunity was discovered. Autoimmunity 1(1): 3-9. [crossref]

- Jahns R, Boivin V, Hein L, Triebel S, Angermann CE, Ertl G, Lohse MJ (2004) Direct evidence for a beta 1-adrenergic receptor-directed autoimmune attack as a cause of idiopathic dilated cardiomyopathy. J Clin Invest 113(10): 1419-1429. [crossref]

- Zimering MB (2017) Diabetes Autoantibodies Mediate Neural- and Endothelial Cell- Inhibitory Effects Via 5-Hydroxytryptamine- 2 Receptor Coupled to Phospholipase C/Inositol Triphosphate/Ca2+ Pathway. J Endocrinol Diabetes 4(4): 10.15226/2374-6890/4/4/00184. [crossref]

- Zimering MB (2018) Circulating Neurotoxic 5-HT2A Receptor Agonist Autoantibodies in Adult Type 2 Diabetes with Parkinson’s Disease. J Endocrinol Diabetes 5(2): 10.15226/2374-6890/5/2/01102. [crossref]

- Zimering MB (2019) Autoantibodies in Type-2 Diabetes having Neurovascular Complications Bind to the Second Extracellular Loop of the 5-Hydroxytryptamine 2A Receptor. Endocrinol Diabetes Metab J 3(4): 118. [crossref]

- Watts SW, Morrison SF, Davis RP, Barman SM (2012) Serotonin and blood pressure regulation. Pharmacol Rev 64(2): 359-88. [crossref]

- Wacker D, Wang S, McCorvy JD, Betz RM, Venkatakrishnan AJ, et al. (2017) Crystal Structure of an LSD-Bound Human Serotonin Receptor. Cell 168: 377-389. [crossref]

- Zimering MB, Grinberg M, Burton J, Pang K. (2020) Circulating Agonist Autoantibody to 5-Hydroxytryptamine 2A Receptor in Lean and Diabetic Fatty Zucker Rat Strains. Endocrinol Diabetes Metab J 4(3): 413. [crossref]

- Kurtz TW, Morris RC (1989) Pershadsingh HA The Zucker fatty rat as a genetic model of obesity and hypertension. Hypertension 13: 896-901. [crossref]

- Clark JB, Palmer CJ, Shaw WN (1983) The diabetic Zucker fatty rat. Proc Soc Exp Biol Med 173(1): 68-75. [crossref]

- Coimbra T, Janssen U, Grone H, Ostendorf T, Kunter U, Schmidt H, Brabant G, Floege J (2000) Early events leading to renal injury in obese Zucker (fatty) rats with type II diabetes. Kidney Int 57: 167-182. [crossref]

- Werle M, Bernkop-Schnürch A (2006) Strategies to improve plasma half life time of peptide and protein drugs. Amino Acids 30(4): 351-67. [crossref]

- Fredersdorf S, Thumann C, Ulucan C, Griese DP, Luchner A, Riegger GA, Kromer EP, Weil J (2004) Myocardial hypertrophy and enhanced left ventricular contractility in Zucker diabetic fatty rats. Cardiovasc Pathol 13(1): 11-19. [crossref]

- Mazzaglia, G, Ambrosioni, E, Alacqua, M, Filippi, A, Sessa, E, Immordino, V, Borghi, C, Brignoli, O, Caputi, AP, Cricelli, C, Mantovani, LG (2009) Adherence to antihypertensive medications and cardiovascular morbidity among newly diagnosed hypertensive patients. Circulation 120: 1598-1605.

- Bui AL, Horwich TB, Fonarow GC (2011) Epidemiology and risk profile of heart failure. Nat Rev Cardiol 8(1): 30-41. [crossref]

- GBD 2015 Risk Factors Collaborators (2016) Global, regional, and national comparative risk assessment of 79 behavioural, environmental and occupational, and metabolic risks or clusters of risks, 1990-2015: a systematic analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2015. Lancet 388(10053): 1659-1724. [crossref]

- Ettehad D, Emdin CA, Kiran A, Anderson SG, Callender T, Emberson J, Chalmers J, Rodgers A, Rahimi K (2016) Blood pressure lowering for prevention of cardiovascular disease and death: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Lancet 387(10022): 957-967. [crossref]

- SPRINT Research Group. Wright JT, Williamson JD (2015) A randomized trial of intensive versus standard blood-pressure control. N Engl J Med 373: 2103-2116.

- The Japanese Society of Hypertension Guidelines for the Management of Hypertension (JSH 2009). Hypertens Res 32: 3-107. [crossref]

- Eguchi K, Kario K, Hoshide Y, Hoshide S, Ishikawa J, Morinari M, Ishikawa S, Shimada K (2004) Comparison of valsartan and amlodipine on ambulatory and morning blood pressure in hypertensive patients. Am J Hypertens 17(2): 112. [crossref]

- Kasho M, Sakai M, Sasahara T, Anami Y, Matsumura T, Takemura T, Matsuda H, Kobori S, Shichiri M (1998) Serotonin enhances the production of type IV collagen by human mesangial cells. Kidney Int 54(4): 1083-92.

- Kaur, G. Krishan, P. (2020) Understanding Serotonin 5-HT2A Receptors-regulated cellular and molecular Mechanisms of Chronic Kidney Diseases. Ren Replace Ther 6, 25. https: //doi.org/10.1186/s41100-020-00268

- Zimering MB, Delic V, Citron BA (2021) Gene Expression Changes in a Model Neuron Cell Line Exposed to Autoantibodies from Patients with Traumatic Brain Injury and/or Type 2 Diabetes. Mol Neurobiol. doi: 10.1007/s12035-021-02428-4. [crossref]

- Oliver E, Rovira E, Montó F, Valldecabres C, Julve R, Muedra V, Ruiz N, Barettino D, D’Ocon P (2010) beta-Adrenoceptor and GRK3 expression in human lymphocytes is related to blood pressure and urinary albumin excretion. J Hypertens 28(6): 1281-9. [crossref]