DOI: 10.31038/AFS.2021332

Abstract

Fish population is a subject to natural control processes in respect of resource and a renewable resource if they are exploited in a systematic and planned manner. Random fish samples of Cyprinus carpio were collected. A total of 548 fish specimens in size ranges between 97 to 687 mm and age classes of 0+ to 9+ were used in present study. Invasion potential and population structure of C. carpio was studied during February 2019 to January 2020 from Sirsa fish landing centre at Prayagraj, Uttar Pradesh, Central India. C. carpio is of great socioeconomic importance for the region and keeps active a population of about 100 to 150 fishermen communities in Sirsa at Prayagraj, Uttar Pradesh. The age classes (0+ to 9+) indicated that the C. carpio was powerfully invaded in the Tons river. In total stock, male population comprised 49.63% and female population 50.36% of the total catches. In the pooled samples, 1+ age group was most dominated with 24.09%. Stock of this age group was most abundant in the Tons river. The mesh size of the nets and length of net was also more harvested this age group compared to other age groups. The 7+, 8+ and 9+ age groups were shared minute proportion with 2.19%, 0.91% and 0.55%, respectively. These age groups considered as old age groups. In case of pooled samples, 0+, 2+, 3+, 4+, 5+ and 6+ age groups contributed as 6.35%, 21.35%, 18.61%, 13.87%, 7.85% and 3.83%, respectively.

Keywords

Population structure, Invasion potential, Cyprinus carpio, stock health, Tons river, Ganga basin, Riverine ecosystem

Introduction

The non-native fish impact assessment and native fish stock management in respect of ecosystem function, biodiversity, recruitment pattern and fish stock, presently disputing both environmental executives (e.g. policy maker/government) and scientific communities especially in riverine sector and other large water bodies in developing countries [1-4]. Non-native species may become invasive and are capable of decreasing biodiversity through competition, spreading exotic diseases, predation and habitat degradation, genetic deterioration of wild populations through hybridization and gene introgression in short or long course of time [5-8]. Non-native fish species are also responsible for reduction of fish lenght, damage breeding ground and change food web structure and population structure of indigenous fish species and also earlier introduced fish species [9-13].

Fish stocks are altering, damaging and invading by human activities like as domestic, business, ornamental or trial purposes [14-18]. The Indian riverine fisheries are mostly disturbed by various stressors as like invasion of fishes (example alien species), overexploitation, domestic and industrial effluents [19-22]. Alien or exotic fish species have the great capacity to cause considerable ecological consequences in introducing or receiving ecosystems especially rivers, streams and reservoirs [23-25].

Cyprinus carpio is commonly called as common carp is non-native fish species or an exotic major carp for India. C. carpio forms a capture fishery of great value in the Ganga river system and other major riverine system and large water bodies of the country, apart from being one of the important species in the culture fishery of the country due to high consumer preference and higher production with Indian major carp (Catla catla, Labeo rohita, Cirrhinus mrigala) [3,16,25,26]. It is widely distributed in the inland water in India [27,28]. The present study was thus undertaken to estimate invasion potential and population structure of C. carpio from the Tons river at Prayagraj, Uttar Pradesh, Central India. This study will help in enhancing the productivity of the river and formulating the fishery management policies of C. carpio from the Tons river in respect of Indian major carp.

Material and Methods

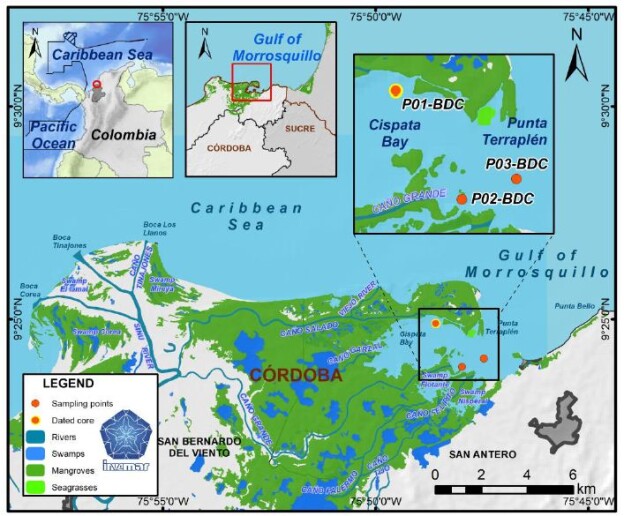

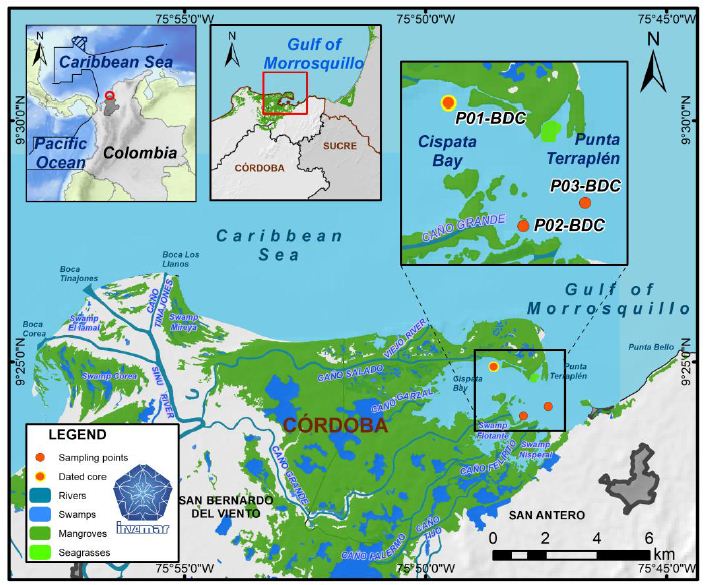

The fish samples of Cyprinus carpio were collected from Sirsa fish landing centre at Prayagraj, Uttar Pradesh, India during February 2019 to January 2020 (Map 1). Samples of the key scales from 548 fish specimens in the length ranges between 97 to 687 mm were examined for determination of age group and population structure. The key scales were removed from the row above lateral line and below dorsal fin region [17,29]. The scales were cleaned in 5% KOH solution to remove adhering- tissues and finally washed in distilled water. The scales were then pressed between two glass plates while drying in order to avoid their curling. The total length (mm) from the tip of snout to the end of largest caudal fin rays was measured and key scales were taken from below the dorsal fin (3 or 4 rows) and above the lateral line. The annulus or annuli formation was determined according to the criterion suggested by [30,31]. A percentage frequency table was prepared on the basis of age and to compute in different sexes (male and female). Population structures of male and female fish were determined on the basis of age group.

Map 1: Tons river map with Allahabad district now Prayagraj district. The sampling site Sirsa is confluence of Tons river from the Ganga river at Prayagraj, Uttar Pradesh.

Result and Discussion

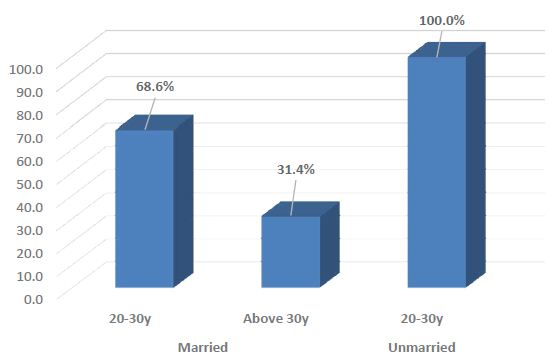

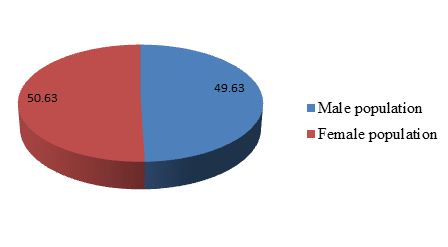

Cyprinus carpio is one of the most desirable fish species for food and commercial purposes by majority consumers in this region (Tons river basin). The population structure of the male and female C. carpio was varied from 85 to 472 mm (total length) and 0+ to 9+ age groups. This species is of great socioeconomic importance for the region and keeps active a population of about 100 to 150 fishermen communities at Sirsa at Prayagraj, Uttar Pradesh. In stock, male population comprised 49.63% and female population 50.36% of the total catches (Table 1 and Figure 1). In general, female fishes are more active compared to male in breeding season. Female population was higher due to twice or thrice breeding season.

Table 1: Population structure of Common carp (Cyprinus carpio) from the Tons river at Prayagraj, India.

|

Age classes |

Number of male | Percentage | Number of female | Percentage | Pooled samples | Percentage |

| 0+ | 20 | 7.35 | 17 | 6.16 | 37 |

6.75 |

|

1+ |

64 | 23.53 | 68 | 24.64 | 132 | 24.09 |

| 2+ | 57 | 20.95 | 60 | 21.74 | 117 |

21.35 |

|

3+ |

50 | 18.38 | 52 | 18.84 | 102 | 18.61 |

| 4+ | 37 | 13.60 | 39 | 14.13 | 76 |

13.87 |

|

5+ |

20 | 7.35 | 23 | 8.33 | 43 | 7.85 |

| 6+ | 12 | 4.41 | 9 | 3.26 | 21 |

3.83 |

|

7+ |

7 | 2.57 | 5 | 1.81 | 12 | 2.19 |

| 8+ | 3 | 1.11 | 2 | 0.72 | 5 |

0.91 |

|

9+ |

2 | 0.73 | 1 | 0.36 | 3 | 0.55 |

| Total | 272 | 49.63 | 276 | 50.36 |

548 |

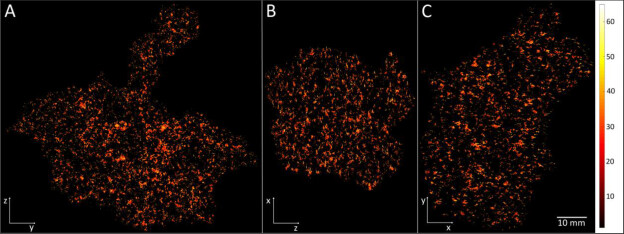

Figure 1: Population structure of male and female from the Tons river at Prayagraj, Uttar Pradesh, Central India.

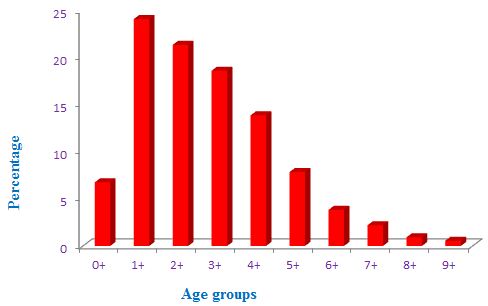

In the pooled samples, 1+ age group was most dominated with 24.09%. Stock of this age group was most abundant in the Tons river, Uttar Pradesh, Central India (Figure 2). The mesh size of the nets was also more harvested this age group compared to other age groups. The 7+, 8+ and 9+ age groups were shared small proportion with 2.19%, 0.91% and 0.55%, respectively. These age groups considered as old age groups. In case of pooled samples, 0+, 2+, 3+, 4+, 5+ and 6+ age groups contributed as 6.35%, 21.35%, 18.61%, 13.87%, 7.85% and 3.83%, respectively (Figure 2). The 9+ age group indicated that the ecological condition was most favorable for C. carpio from the Tons river. The age classes also indicated that the C. carpio was powerfully invaded in the Tons river. It is believed that this healthy stock (0+ to 9+ age groups) of C. carpio from the Tons river due to habitat degradation and water quality of the river. Overall, population distribution was systematic in the pooled samples. The 5+ age group probably remain unexploited. Distribution pattern indicated that the population of C. carpio in future will be increased (Figure 2).

Figure 2: Population structure of stock fishes (Pooled samples) from the Tons river at Prayagraj, Uttar Pradesh, Central India.

According to the percentage occurrence 1+ age group was also most dominated with male (23.53%) and female (24.64%) of the total stocks (Table 1). Male population was contributed in 0+, 2+, 3+, 4+, 5+ and 6+ age groups with percentage shared as 7.35%, 20.95%, 18.38%, 13.60%, 7.35% and 4.41%, respectively (Table 1). The old age groups 7+, 8+ and 9+ were contributed minute proportion with 2.57%, 1.11% and 0.73%, respectively.

While female population was contributed in 0+, 2+, 3+, 4+, 5+ and 6+ age groups with percentage as 6.16%, 21.74%, 18.84%, 14.13%, 8.33% and 3.26%, respectively (Table 1). The old age groups 7+, 8+ and 9+ were contributed very minute proportion with 1.81%, 0.72% and 0.36%, respectively (Table 1). In the present study, C. carpio indicates that occurrences of males and females are difference in number; this is possibly caused by the incidence of fish pairs near to the nest area where females take care of their broods. It breeds twice or thrice per year. The frequency of the breeding is more suitable for the stabilization of the stocks in the river.

Present time, the ecological condition of Tons river at Prayagraj is most fitting (example age composition, population structure) for C. carpio. [32] reported that the population structure of Labeo bata, female was greater than male in the Ganga river at Allahabad. The age group 1+ of C. carpio was dominant (21.54%) and constituted nearly one fifth of the total population from the Ganga river at Allahabad [33]. [34] reported that the O. niloticus of males comprised 56.1% and females 43.9% of the catches in Barra reservoir, Brazil. [35] determined the population structure of the Himalayan Mahseer (T. putitora) in the foothill section of the Ganga river and reported that the samples comprised of 1+ to 9+ age groups individuals. Of these 2+ and 4+ age groups constituted 66.01%, while 1+ was nearly 8.07% of the total stock. Most wild fish stocks (example indigenous fish species) in Indian rivers have been over exploited or have reached their maximum sustainable yield but stock of exotic species increasing day by day [26,36,37]. C. carpio with a known capability to adjust to different environmental situation and its high prospective for aquaculture, can now be found in many rivers of India [38-41].

References

- Hooper DU, Chapin FS, Ewel JJ, Hector A, Inchausti P, et al. (2005) Effects of biodiversity on ecosystem functioning: a consensus of current knowledge. Ecological Monographs 75: 3-35.

- Dwivedi AC, Mayank P, Tripathi S, Tiwari A (2017) Biodiversity: the non-natives species versus the natives species and ecosystem functioning. Journal of Biodiversity, Bioprospecting and Development

- Dwivedi AC, Mayank P (2018) Suitability of ecosystem determination through biology and marketing of exotic fish species, Oreochromis niloticus (Linnaeus, 1757) from the Ganga River, India. Journal of Aquatic Research and Marine Sciences 1: 69-75.

- Dudgeon D, Arthington AH, Gessner MO, Zen-Ichiro K, Knowler DJ, et al. (2006) Freshwater biodiversity importance, threats, status and conservation challenges. Biological Review 81: 163-182. [crossref]

- Casal CMV (2006) Global documentation food fish introductions the growing crisis and recommendations for action. Biological Invasions 8: 3-11.

- Tiwari A, Dwivedi AC, Mayank P (2016) Time scale changes in the water quality of the Ganga River, India and estimation of suitability for exotic and hardy fishes. Hydrology Current Research 7:

- Daga VS, Sko´ra F, Padial AA, Abilhoa V, Gubiani EA, et al. (2015) Homogenization dynamics of the fish assemblages in Neotropical reservoirs comparing the roles of introduced species and their vectors. Hydrobiologia 746: 327-347.

- Gozlan RE, Záhorská E, Cherif E, Asaeda T, Britton, JR, et al. (2020) Native drivers of fish life history traits are lost during the invasion process. Ecology & Evolution 10: 8623-8633.

- Dwivedi AC, Mayank P (2017) Reproductive profile of Indian Major Carp, Cirrhinus mrigala (Hamilton, 1822) with Restoration from the Ganga River, India. Journal of Fisheries & Livestock Production 5.

- Dwivedi AC, Jha DN (2013) Population structure of alien fish species, Oreochromis niloticus (Linnaeus, 1757) from the middle stretch of the Ganga river, India. Journal of the Kalash Science 1: 157-161.

- Dwivedi AC (2009) Ecological assessment of fishes and population dynamics of Labeo rohita (Hamilton), Tor tor (Hamilton) and Labeo calbasu (Hamilton) in the Paisuni river. Aquacult 10: 249-259.

- Vilizzi L, Copp GH (2017) Global patterns and clines in the growth of common carp Cyprinus carpio. Journal of Fish Biology 91: 3-40.

- Dwivedi AC, Mayank P, Tiwari A (2017) Size selectivity of active fishing gear: changes in size, age and growth of Cirrhinus mrigala from the Ganga River, India. Fisheries and Aquaculture Journal

- Vitousek PM, Mooney HA, Lubchenco J, Melillo JM (1997) Human domination of earth’s ecosystems. Science 277: 494-499.

- Tripathi S, Gopesh A, Dwivedi AC (2017) Framework and sustainable audit for the assessing of the Ganga river ecosystem health at Allahabad, India. Asian Journal of Environmental Science 12: 37-42.

- Dwivedi AC, Mishra N (2021) Age structure of non-native fish species, Cyprinus carpio (Linnaeus, 1758) from the tributary of the Ganga river, India. Journal of Aquaculture & Marine Biology 10: 76-79.

- Miehls ALJ, Mason DM, Frank KA, Krause AE, Peacor SD, et al. (2009) Invasive species impacts on ecosystem structure and function A comparison of the Bay of Quinte, Canada, and Oneida Lake USA, before and after Zebra mussel invasion. Ecological Modeling 220: 3182-3193.

- Dwivedi AC, Mayank P, Masud S, Khan S (2009) An investigation of the population status and age pyramid of Cyprinus carpio communis from the Yamuna river at Allahabad. The Asian Journal of Animal Science 4: 98-101.

- Rizvi AF, Dwivedi AC, Singh KP (2010) Study on population dynamics of Labeo calbasu (Ham.), suggesting conservational methods for optimum yield. National Academy of Sciences Letter 33: 247-253.

- Mayank P, Dwivedi AC (2016) Linking Cirrhinus mrigala (Hamilton, 1822) size composition and exploitation structure to their restoration in the Yamuna river, India. Asian Journal of Bio Science 11: 292-297.

- Mayank P, Dwivedi AC (2017) Resource use efficiency and invasive potential of non-native fish species, Oreochromis niloticus from the Paisuni River, India. Poultry Fisheries & Wildlife Sciences

- Dwivedi AC, Mayank P, Tiwari A (2016) The River as transformed by human activities: the rise of the invader potential of Cyprinus carpio and Oreochromis niloticus from the Yamuna River, India. Journal of Earth Science & Climatic Change 7:

- Dwivedi AC, Tiwari A, Mayank P (2018) Environmental pollution supports to constancy and invader potential of Cyprinus carpio and Oreochromis niloticus from the Ganga river, India. International Journal of Poultry and Fisheries Sciences 2: 1-7.

- Gozlan RE, Britton JR, Cowx I, Copp GH (2010) Current knowledge on non-native freshwater fish introductions. Journal of Fish Biology 76: 751-786.

- Mishra N, Dwivedi AC (2020) Environmental derivers supports to distribution, composition and biology of Cyprinus carpio (Linnaeus, 1758) in respect of time scale: A review. Journal of the Kalash Science 8: 91-102.

- Mayank P, Dwivedi AC (2015) Biology of Cirrhinus mrigala and Oreochromis niloticus. LAP LAMBERT Academic Publishing GmbH & Co. KG, Dudweiler Landstr. 99, 66123 Saarbrucken, Germany 188.

- Pathak RK, Gopesh A, Dwivedi AC (2011) Alien fish species, Cyprinus carpio communis (common carp) as a powerful invader in the Yamuna river at Allahabad. Natl. Acad. Sci. Lett 34: 367-373.

- Dwivedi AC, Mishra AS, Mayank P, Tripathi S, Tiwari A (2019) Resource use competence and invader potential of Cyprinus carpio from the Paisuni river at Bundelkhand region, India. Journal of Nehru Gram Bharati University 8: 20-29.

- Mayank P, Dwivedi AC, Pathak RK (2018) Age, growth and age pyramid of exotic fish species Oreochromis niloticus (Linnaeus 1758) from the lower stretch of the Yamuna river, India. National Academy Science Letter 41: 345-348.

- Tempero GW, Ling N, Hicks BJ, Osborne MW (2006) Age composition, growth, and reproduction of koi carp (Cyprinus carpio) in the lower Waikato region, New Zealand. New Zealand Journal of Marine and Freshwater Research 40: 571-583.

- Nautiyal P, Dwivedi AC (2020) Growth rate determination of the endangered Mahseer, Tor tor (Hamilton 1822) from the Bundelkhand region, central India. Journal of Fisheries Research 4: 7-11.

- Dwivedi AC, Tripathi S, Khan S, Mayank P (2011) Population structure of Labeo bata (Hamilton) from the middle stretch of the Ganga river. Asian Journal of Animal Sciences 6: 188-190.

- Pathak RK, Gopesh A, Joshi KD,Dwivedi AC (2013) Cyprinus carpio communis in middle stretch of river Ganga at Allahabad. Journal of the Inland Fisheries Society India 45: 60-62.

- Novaes JLC, Carvalho ED (2012) Reproductive, food dynamics and exploitation level of Oreochromis niloticus (Perciformes: Cichlidae) from artisanal fisheries in Barra reservoir, Brazil. Rev. Biol. Trop 60: 721-734. [crossref]

- Bhatt JP, Nautiyal P, Singh HR (2000) Population structure of Himalayan mahseer a large cyprinid fish in the regulated foothill section of the River Ganga. Fisheries Research 44: 267-271.

- Dwivedi AC, Nautiyal P (2012) Stock assessment of fish species, Labeo rohita, Tor tor and Labeo calbasu in the rivers of Vindhyan region, India. Journal of Environmental Biology 33: 261-264. [crossref]

- Tripathi S, Gopesh A, Dwivedi AC (2017) Fish and fisheries in the Ganga river: current assessment of the fish community, threats and restoration. Journal of Experimental Zoology, India 20: 907-912.

- Zambrano L, Martinez-Meyer E, Menezes N, Peterson AT (2006) Invasive potential of common carp (Cyprinus carpio) and Nile tilapia (Oreochromis niloticus) in American freshwater systems. Canadian J Fisheries Aquatic Sci 63: 1903-1910.

- Montana CG, Choudhary SK, Dey S, Winemiller KO (2011) Composition trends of fisheries in the River Ganges, India. Fisheries Management and Ecology 18: 282-296.

- Mayank P, Dwivedi AC (2015) Role of exotic carp, Cyprinus carpio and Oreochromis niloticus from the lower stretch of the Yamuna river. In: Advances in Biosciences and Technology Edited by K. B. Pandeya, A. S. Mishra, R. P. Ojha and A. K. Singh published by NGB (DU), Allahabad, 93-97.

- DwivediAC (2006) Age structure of some commercially exploited fish stocks of the Ganga river system (Banda-Mirzapur section). Thesis submitted to Department of Zoology, University of Allahabad, Prayagraj, (Uttar Pradesh) 138.