Abstract

AI embedded in the platform of Mind Genomics was used to synthesize mind-sets regarding the attitudes of parents towards what is being taught to their children. The AI program emerged with the three mind-sets being Traditionalists, Concerned Parents, and Progressives, respectively. The AI program clearly summarized the values of these three mind-sets when instructed to define what the mind-sets believed to be wrong with today’s education, to be ok with today’s education, and finally to be excellent with today’s education. The AI program, Idea Coach, was instructed to create 20 statements, and to predict how each of the three mind-sets would score each statement in terms of whether or not it bothered them, and whether or not this statement described what was happening in their schools. The answers made intuitive sense. The process shows the power of AI as an aid to critical thinking and understanding, as well as a novel way to deal with a complicated topic even before doing any reading or research.

Introduction

During the past several years a variety of news stories have appeared regarding the discovery that students in classrooms around the United States may be receiving propaganda in their daily lessons. One need only read stories about propaganda to realize that something may be going on, although we do not know. This issue has come to the fore recently with the spread of news about the influence of the Chinese Communist Part (CCP), such as this headline from the Oklahoma Council of Public Affair in August 2023 Tulsa Schools Linked to Chinese Communist Entity [1]. We are accustomed to hearing this in other countries and situations, such as the recently revealed but long-known fact that the ‘teachers’ in Gaza, supported by the United Nations (UNWRA) are teaching anti-Israel and anti-Semitic material, lesson material that is found in their textbooks [2]. The issue is here in the United States as well, as expressed in a November 22, 2023, story by Zachary Faria in the Washington Examiner: The Democratic Party’s panic over losing control of narratives in schools has led it to pursue a new path to propagandize to children: mandatory “media literacy” classes to teach students about “fake news.”. Media literacy lessons are now mandatory in California in English, science, history, and even math classes throughout every grade level, thanks to a law signed by Gov. Gavin Newsom (D-CA) last month. Delaware, Illinois, and New Jersey are also among the states requiring these lessons. Among other things, the California law worries about the effects of “online misinformation” that has “threatened public health.” [3]

The issue of teachers teaching what the parent’s believe the student should not be learning appears to be a systemic issue, perhaps one plaguing all of society. Increasingly, teacher values clash with parent’s values, the conflict played out in the arena of education. ‘School boards have a central position in educational governance. They have to guarantee quality, monitor results and intervene if needed’ [4]. The issue is explained even more elegantly by [5]’…while school administrators are challenged to turn schools around with limited time and resources quickly, their efforts are not a silver bullet. Engaging community requires committed partnerships that support schools to advance quality learning. Community school councils, an organizing strategy, focus on addressing potential threats and enhancing strengths for student success’.

In the United State, irate parents have verbally attacked the local school boards, often the attack making news. The complaining parents are called ‘terrorists’. The local education establishment gather around to defend the teacher and castigate the irate parents. . “New whistleblower information has revealed that the FBI targeted parents who spoke out against their local school boards’ COVID policies, after prodding from education officials. It all started in September, when the National School Boards Association (NSBA) sent a letter to the Department of Justice (DOJ) requesting federal intervention into the alleged “domestic terrorism” that is citizens disagreeing with school board officials” [6]

The conflict between parents and the educational system has created the opportunity for academic investigation on a broad front, ranging from who is teaching to whom, and most important, what is taught, with what emphasis, and with what objective [7-9].

The opportunity to explore these issues using AI embedded in the Mind Genomics platform, www.bimileap, allows us to look at the topic in a new way, and with some new tools. The tool, Idea Coach, allows us to specify a problem, and after specifying the problem, put AI to work to generate the data.

The approach presented here originates in the effort by the authors to change the way we discover how people think. The traditional methods began with qualitative discussions, in which people could surface their concerns, and in which a trained ‘listener’ or ‘moderator’ could elicit information from people leading to insights. There is an entire discipline of qualitative research, popular, growing, requiring training to understand what is really being communicated in an interview or in a group discussion. It is from these qualitative interviews with parents as well as observing what is being reported in the media that the importance of the curriculum being used with the students has emerged.

Beyond qualitative work is the effort by researchers to measure the minds of peoples, or if not the minds, then measure the attitudes of people. These measurements are done by surveys, in which the researcher creates a list of questions about topics, and instructs the respondent, the survey taker, to rate the different topics or questions on one or another scale. Most of the readers by now should be familiar with surveys which seem to follow every transaction of a business nature, with the survey attempting to quantify the different aspects of the experience. Typically the surveys are either done for general attitudes or for specific attitudes, but in either case the surveys fail to get to the granularity of the experience. Nonetheless, the researcher executing the survey ends up with a measure of performance or importance of an experience relevant to the group commissioning the survey

It was against this background of surveys and the failure to deal with the granularity of the data that the notion of presenting respondents with combinations of messages emerged. The research leading to this effort had been developed by mathematical psychologists under the name conjoint measurement [10], and popularized by Wharton professors [11]. The underlying idea was to present the respondent with combinations of messages about a situation, obtain their reaction to the messages and then deconstruct the messages into the contribution of the components.

The trajectory of science would lead to some developments in this effort to understand the mind of the person. The first effort was the creation of a DIY, do-it-yourself system, to run these experiments on topics, with the user providing questions which told a story, and for each question provide four answers, and then mix and match the answers (also called elements), to create a set of combinations (called vignettes). The respondent or survey taker would be presented with these combinations and instructed to rate the combination. Each respondent evaluated a full set of combinations, these combinations constructed by an underlying experimental design which prescribed the component elements of the vignette. The later analysis generated an estimate of the contribution of each element.

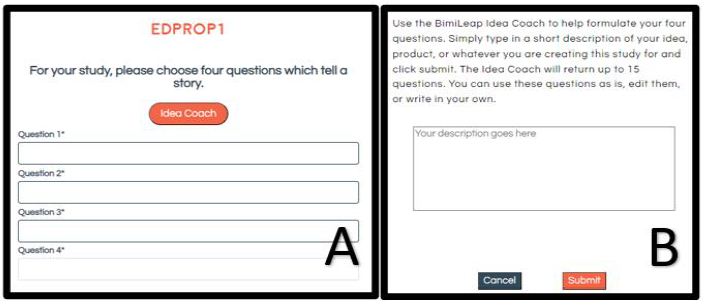

The requirement to develop the four questions which tell a story proved to be a stumbling block. It was to address this issue that the approach, now called Mind Genomics, first attempt to teach users, but then with increased effort changed direction. Rather than teaching students, it became easier to create an AI-powered system called Idea Coach which, upon receiving a background of the study, would come up with the offering of 15 questions, and then for each question 15 answers. The task facing the researcher was now to write a coherent ‘squib’ requesting the 15 questions. Once the questions were chosen it was easy to create 15 answers for each question. Figure 1 shows the process.

Figure 1: The basic Mind Genomics set-up. Panel A shows the request for four questions which tell a story. Panel B shows the AI-powered Idea Coach. The user can instruct the embedded AI to provide information.

Introducing the Problem to AI

The remainder of this paper shows the process of creating an orientation to AI, instructing AI to provide the relevant information, and then generating the necessary materials from the internal processing of AI. The approach can be done on the current Mind Genomics platform (www.bimileap.com). The one caveat is that with the same orientation to AI the output from Idea Coach varies, even when run several times. The reason for the variation is not known. The AI does try to follow instructions. Occasionally the AI returns with a message saying that it cannot fulfill the task, providing one or another reason for not be able to do so. Yet, despite the lack of perfect reproducibility, it is the very richness and instructional value from the AI output which motivates this paper.

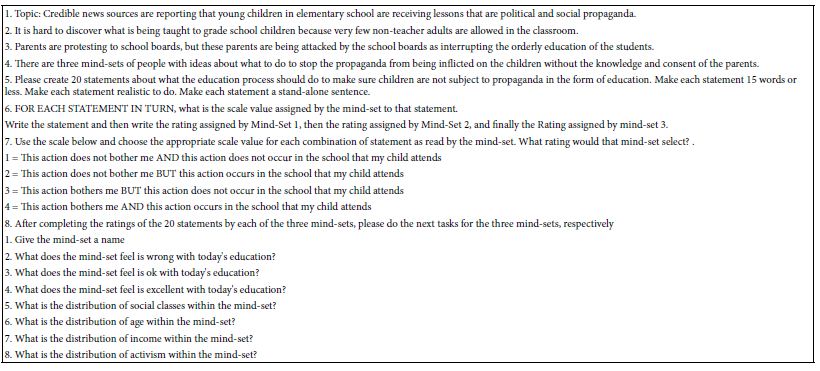

Table 1 shows the introductory ‘squib’ or description provided to the Idea Coach program embedded in the BimiLeap program. The structure of Table 1 is important to elucidate because with AI small deviations from the pattern can end up causing the AI to deliver the wrong material., or to be incomplete. The parts of the introductory squib play different roles.

Table 1: The input ‘squib’ to Idea Coach. The input describes generalities of the mind-sets, requesting that AI provide specifics for each mind-set.

Topic (Sentences 1-3)

In the ‘topic’ the user must provide the AI with some sort of background. The AI output from Idea Coach is sensitive to the phrases. In order to allow a systematic exploration of the impact of the set-up on the results, the set-up material is structured into three short sentences, each sentence spatially separated from the others by a blank line. In this way it becomes possible to change the orientation quickly, either help the AI provide the necessary information, or even to help explore what happens when the orientation is changed by adding something about the year in history for which the information is desired, or the country and year for which the information is desired

Posited Mind-Sets (Sentence 4)

The orientation states that there are three mind-sets, but does not define what a mind-set is, nor give any information about the mind-sets, other than there are three. In other uses of Mind Genomics and specifically Idea Coach, the authors have occasionally defined the mind-sets, whether these definitions be very tight and specific, or whether these definitions be ‘broad stroke.’ As will be shown in the next few paragraphs, simply defining that there are three mind-sets suffices for the AI to provide three radically different groups. From iteration to iteration there may be some changes in the nature of the three mind-sets, but each iteration makes sense.

Request for AI to Generate 20 Statements (Sentence 5)

These statements pertain to what the education process should do to ensure that the children are not subject to propaganda in the form of education. The instruction to AI is to provide a reasonably short phrase (15 words or less), that statement is realistic, and that each statement is a stand-alone sentence. AI has no problem following these directions.

Instruct AI to ‘Rate’ Each Statement on a Defined Four-point Scale (Sentences 6 and 7)

The AI is to assume that the statement was read by each of the three mind-sets, respectively. The scale is defined completely. The ingoing assumption is that the AI understands the meaning of the question, understands the meaning of the rating scale, and can assume the role of the mind-set.

Provide an Addition Eight Pieces of Information about Each Mind-set (Sentence 8)

Once presented with the request in the squib, it takes the Idea Coach approximately 10-15 seconds to provide answers. Each the user requests a new ‘run’ the Idea Coach begins anew. Occasionally Idea Coach cannot immediately answer the question immediately, returning with an apology. Later, however, after the effort has finished, Idea Coach will return with each of the iterations summarized. Those iterations that could not be addressed immediately and about which the Idea Coach apologized end up having been answered, however. The only problem seems to be the ability to provide the answers immediately and then move on to the next iteration.

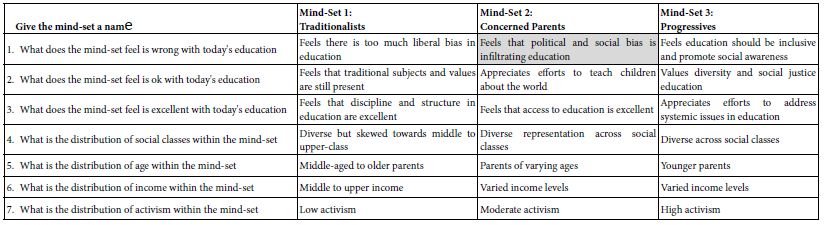

We move on with the section of the squib requesting information about the three mind-sets. The information appears in Table 2. The columns show the three mind-sets, the rows show the answers to the eight questions. If were to trace back the mind-sets to the complaint about propaganda in education, it would be Mind-Set 2, the so-called ‘Concerned Parents’ who would be the ones most likely to fear the propaganda.

Table 2: Specifics for the three mind-sets created by AI

It is important to recognize that the user provided no information to the Idea Coach other than the ‘operating hypothesis’ that there exist three different mind-sets in the population. Despite the paucity of direction given to the AI in Mind Genomics, Table 2 shows a quite reasonable division of points-of-view across the mind-sets. Table 2 also shows hypothesized demographic distributions which make intuitive sense.

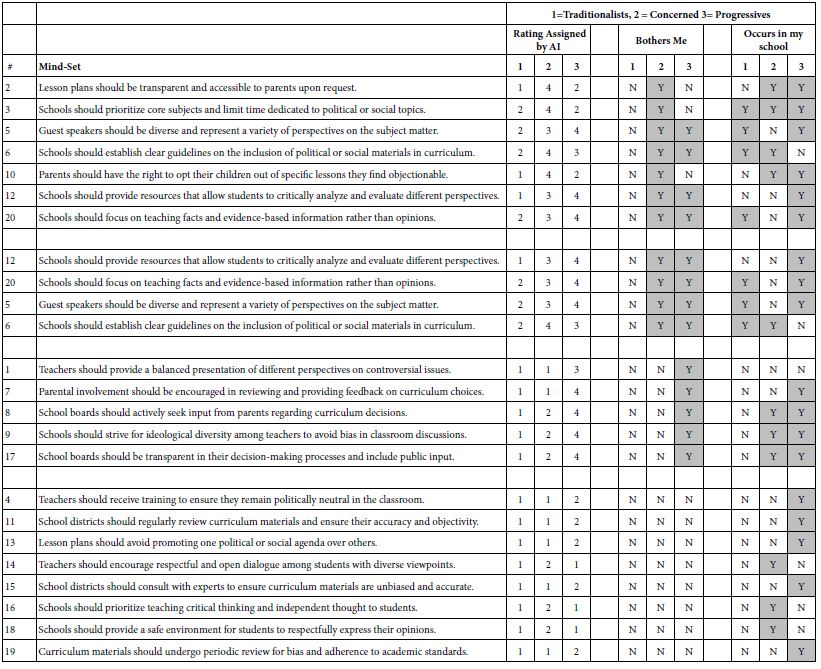

Perhaps the strongest evidence for the usefulness of AI comes from ratings assigned to the mind-sets. Part of the request to Idea Coach was to suggest the likely rating to be assigned to each of 20 statements. The rating scale was two-sided, one side of the scale talking about ‘bothers me’, and the other side of the scale talking about ‘occurs in my school’. The mind-sets emerging from AI focus on topics of opinion. The AI did not request any guidance about the mind-sets, but rather simply presented them. The three mind-sets differ in their concerns and values, as Table 3 shows.

Table 3: AI-generated ratings for the 20 statements according to the three hypothesized mind-sets, as well as the deconstruction of the ratings into what statements ‘bother me’, and what statements describe ‘what occurs in my school’.

The pattern of scaled responses appears to be more intuitively correct than might have been expected. The middle and right sets of columns show two letters, N corresponding to ‘NO’ for that rating category, Y corresponding to ‘YES’ for that rating category. The pattern of Y’s make sense. The ‘Traditionalists’ are not bothered by any of the statements. The ‘Concerned’ are bothered by the content of what is being taught. The ‘Progressives’ are concerned about fairness of what is being taught, and the ability of students to become ‘critical thinkers’.

Table 3 does not show dramatic ideological differences among the hypothesized mind-sets, but rather gives a sense of modest, nuanced differences. Furthermore, the pattern breaks down when we consider the second part of the scale dealing with ‘occurs in my school’. There seems to be no clear pattern here for any of the hypothesized mind-sets.

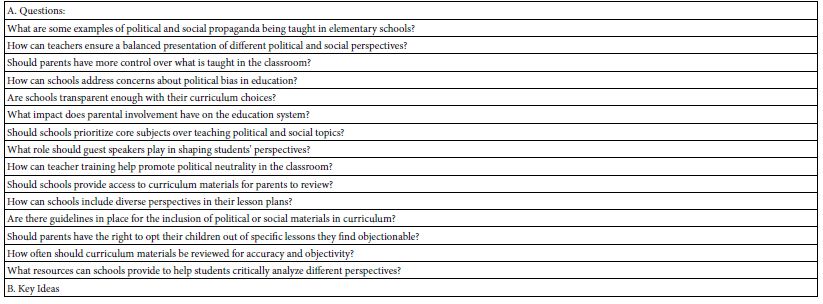

At the end of the iteration, once the user has either gone to the next iteration to obtain new ideas from AI in the Idea Coach routine or has proceeded to select questions and answers, the material created by Idea Coach is sent to a summarizer. The summarizer comprises a series of prompts which end up deconstructing the information and reconstructing the material into new perspectives. The first summarization comprises the analyses shown in Table 4. This summarization shows 15 new questions, 20 key ideas, and 20 themes. This pattern of summarizations is a legacy from the original summarizer, done when the focus of the Idea Coach was to present sets of 15 question to a simple squib, and set of 15 answers to a question. Despite being a legacy summarization, the three sets of statements provide additional topics for consideration, as well as different ways of stating the key issues.

Table 4: AI-generated summarization of the of the key issues, presented to the user in the Idea Book. The analysis is a legacy summarization used in simpler forms of the Idea Coach.

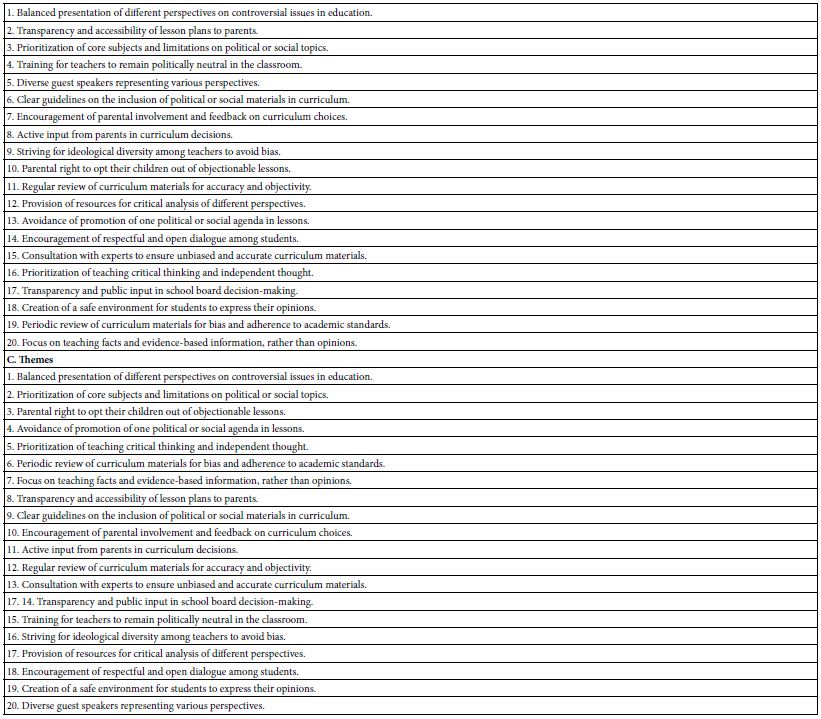

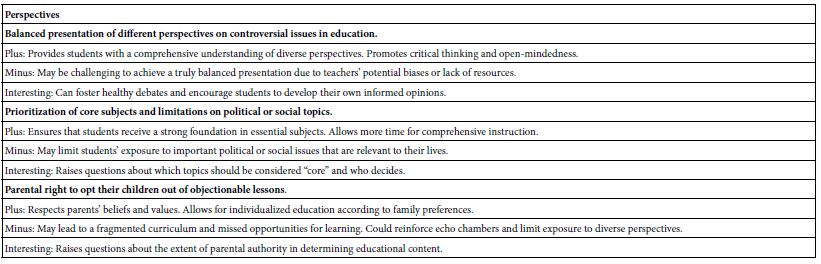

The Idea Coach further analyzes the material, presenting ideas, and for each idea three aspects. These aspects are called Plus (positive aspect), Minus (negative aspect or difficulty), and Interesting (long term benefit). The perspectives appear in Table 5.

Table 5: Perspective on the different ideas, showing short term benefits (Plus), short term problems (Minus), and long-term benefits (Interesting).

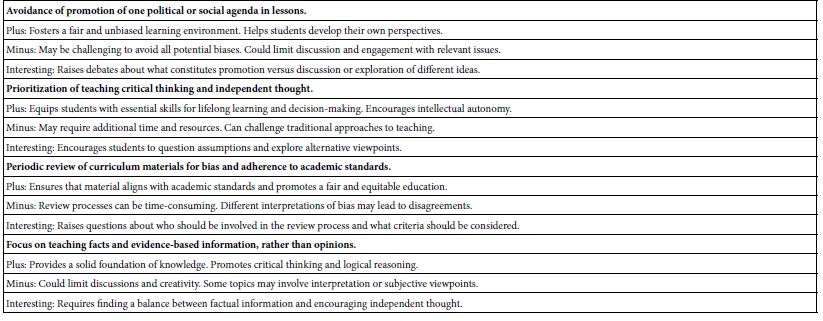

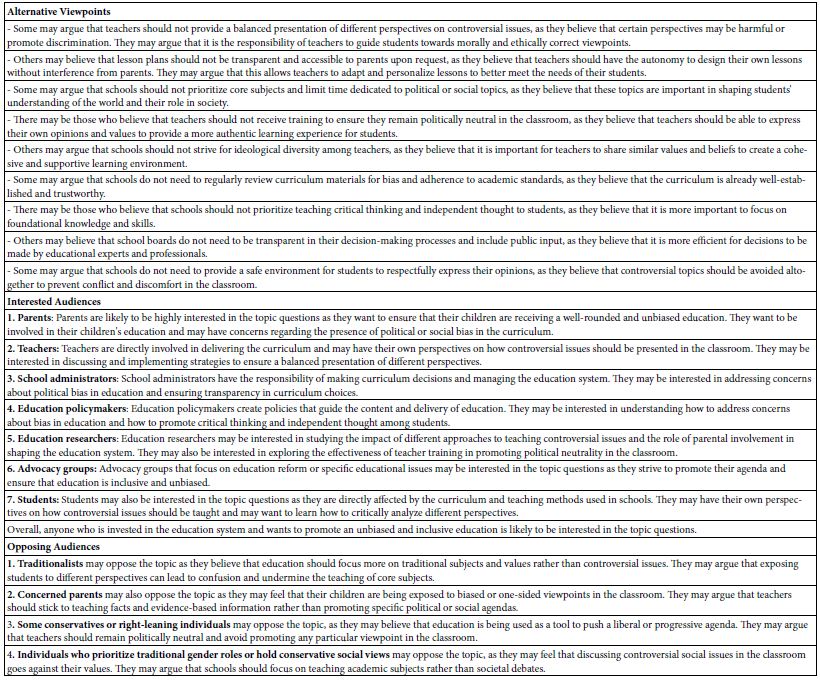

The next set of analyses provided in the Idea Book by the Summarizer deal with the different receptions that the ideas will receive. The first is the Alternative Viewpoints, or different ways of dealing with the topic. The second is the Interested Audiences, those who will accept the ideas. The third is the Opposing Audiences, those who will reject the ideas. Once again the AI embedded in Idea Coach provides a fairly thorough analysis of these viewpoints and responses to the material, an analysis which dramatically augments the understanding of the topic. Table 6 shows these groups of analyses.

Table 6: How the ideas are received, by three different groups suggested by Idea Coach

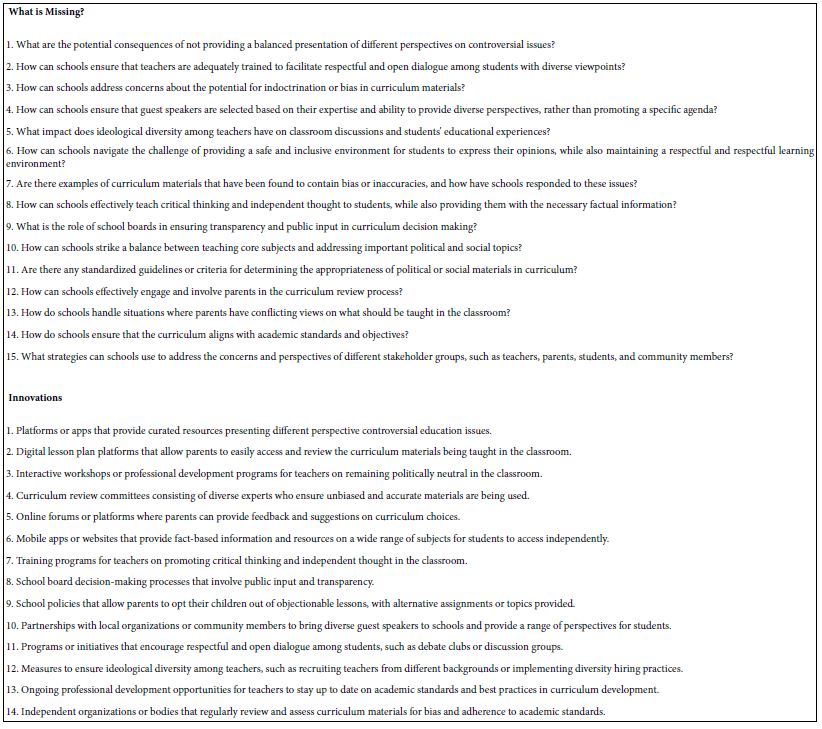

The final set of analyses appears in Table 7. These analyses consider what is missing, and innovation. Once again, the analyses are done completely by AI, working only the information generated from the input squib given to Idea Coach. That information, in turn, comprised only the suggestion of three mind-sets, as well as some modest background of a few lines provided to Idea Coach at the start of the process.

Table 7: Suggestions for the future, based upon an analysis of ‘what is missing’, and suggested ‘innovations’.

Discussion and Conclusions

This paper was generated in response to issues about possible propaganda in schools, a response to news articles and broadcasts from the media. The issue of propaganda is school emerged out of an interest in the actions of the Federal Government versus local school boards, where protesters were considered to be part of a rebellious criminal element. It is issues such as these, issues which inflame the emotions and which call into question the basic rights and liberties of people, which become interesting topics for Mind Genomics.

The original approach of Mind Genomics would have been to introduce the topic by a small squib, the writeup given to the Idea Coach, that writeup simply describing the situation as reported by the media and specifying questions to ask. The next step in the original Mind Genomics would have been to generate sets of 15 questions, select four questions which ‘told a story’, and for each question generate four answers. The respondent would then have been exposed to small vignettes; combinations of these messages would have rated the vignettes with each respondent rating a different set of 24 vignettes. The analysis of the ratings would be by accepted statistics (Ordinary Least Squares to relate elements to ratings; Clustering to define new to the world groups or mind-sets). The outcome of this straightforward approach, done in the space of an hour or two using human respondents would have generated the type of data shown in Table 2 (ratings of each statement by each group).

The approach presented here takes Mind Genomics into an entirely new direction, one fully directed by the artificial intelligence built into the Idea Coach. What emerges as most remarkable is the depth of information from a few lines of request. The AI builds upon itself, providing information at the basic level, viz., the statements, and then building on that information and nothing else to generate the wealth of information presented. What is even more interesting is that the paper deals with the results of one iteration taking about 15-30 seconds for immediate results, and about 30 minutes wait for the summarizer in the Idea Book. Not reported here are the results of 20 of the iterations, each done in 15-30 seconds, occasionally with a small change to the squib, for example to specify that the analysis is to reflect what would have happened say in 1900 vs 2000, or what would have happened had the user specified two mind-sets, or four or five or even many more mind-sets. That parametric investigation awaits the attention of a graduate student for their thesis work.

References

- Carter R (2023) Tulsa school linked to Chinese Communist entity. August 3, 2023 Oklahoma Council of Public Affairs. 2023.

- UN Watch (2023) UN Teachers Call To Murder Jews, Reveals New Report

- Faria Z (2023) The newest Democratic propaganda in schools: ‘Fake news’ classes. Washington Examiner, November 22. 2023.

- Honignh M, Honingh MR, van Thiel S (2020) Are school boards and educational quality related? Results of an international literature review, Educational Review 157-172.

- Medina MA, Grim J, Cosby G, Brodnax R (2020) The power of community school councils in urban schools. Peabody Journal of Education 95: 73-89.

- Institute for Free Speech (2020) FBI Targets Outspoken Parents, School Boards Silence Them.

- Rubin JS, Good RM, Fine M (2020) Parental action and neoliberal education reform: Crafting a research agenda. Journal of Urban Affairs 42: 492-510.

- Sampson C, Bertrand M (2022) “This is civil disobedience. I’ll continue.”: The racialization of school board meeting rules. Journal of Education Policy 37: 226-246.

- Shuffelton A (2020) What parents know: risk and responsibility in United States education policy and parents’ responses. Comparative Education 56: 365-378.

- Luce RD, Tukey JW (1964) Simultaneous conjoint measurement: A new type of fundamental measurement. Journal of Mathematical Psychology 1: 1-27.

- Green PE, Krieger AM, Wind Y (2001) Thirty years of conjoint analysis: Reflections and prospects. Interfaces 31(3_supplement), S56-S73.