Abstract

Background: Maternal deaths in developing countries are quite high accounting for as much as 14 percent of global maternal deaths. One of the global strategies to reduce these deaths requires utilization of health facilities manned by skilled birth attendants for childbirth. Although 67% of women attend ANC in Nigeria, only 39% utilize health facilities for delivery. Thus, this review seeks to ascertain maternal satisfaction with delivery services which will influence childbirth in health facilities in Nigeria.

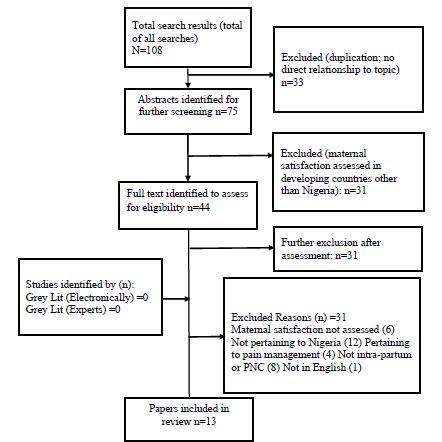

Methods: Literature search was done using different databases and search engines including goggle, PubMed/Medline, Google scholar, web of science, EMBASE, Cochrane library. The search on articles published in English on maternal satisfaction with delivery services in health institutions between 2000 and 2021 yielded 108 articles that were screened for eligibility out of which 44 underwent full text review. Thirteen (13) articles were included in the final analysis.

Results: Eight (61.5%) of the studies reported the prevalence of women’s satisfaction with delivery services to be over 90%. Dissatisfaction was reported in lack of availability and adequacy of electricity, water, equipment, space for consultation/admission and cleanliness of toilets in 5(62.5%) out of the eight studies that reported on physical environment. This was same with, availability of adequate staffing, cost, medicines and supplies. Five (62.5%) of studies reported dis-satisfaction with interpersonal relationship issues; courtesy, respect, privacy, promptness, perceived health worker competency and emotional support. There was report on preference for un-orthodox care centers in some instances.

Conclusions: Although overall satisfaction with health facility delivery services was fair, there was some dis-satisfaction expressed by the women in certain domains. There is need to improve on interpersonal attitudes, provision of medicines and supply as well as infrastructural upgrade and environmental cleanliness. A digitalized feedback system and periodic audits should be made compulsory.

Keywords

Maternal satisfaction, Mother’s perception, Associated factors, Quality of care, Health facility deliveries, Nigeria

Introduction

It is reported worldwide that approximately 800 women die daily from preventable causes which are pregnancy and childbirth related and 99% of all these maternal deaths occur in less developed nations of the world [1-4]. In some parts of the African continent Maternal Mortality Ratios (MMR) are as high as 686 per 100,000 live births which is very abysmal [2,3,5]. The World Health Organization (WHO) estimates put MMR in Nigeria at 814 per 100,000 live births. The lifetime risk of a Nigerian woman dying during pregnancy, childbirth, postpartum or post-abortion is said to be 1 in 22, in contrast to the lifetime risk in developed countries estimated at 1 in 4900 [6].

Utilization of delivery services at the hospital is believed to reduce these unacceptably high maternal complications and deaths especially in sub-Saharan Africa [7]. This is due to the fact that the hospital environment is expected to have the minimal medical standards that will guarantee clean delivery as well as a result of availability of equipment, medicine/supplies and skilled birth attendants [3,4,7,8]. Worldwide, statistics showed that about 2.5 million neonates died within the first 28 days of delivery [7]. It is reported that 2 in 3 neonates died within the first day of birth as a result of inadequate care during labour and delivery [7]. In low and middle income countries where neonatal mortality statistics are abysmal, achieving perinatal survival devoid of morbidity will guarantee maternal satisfaction [7].

Although the report of 2018 Nigeria Demographic Health Survey (NDHS) suggests that as much as 67% of women utilize Antenatal Care (ANC) services, only 39% of then deliver in a health facility where there is a Skill Birth Attendant (SBA) [9]. The poor rate of institutional deliveries shows that not all the women who are booked and attending antenatal care opt for institutional delivery [5]. A good proportion of registered antenatal attendees have alternative place of delivery and some even practice medical pluralism which entails utilizing Traditional Birth Attendants (TBAs), home deliveries and maternity homes at the same time [4,9].

A lot of reasons have been proffered as explanation to this irregular utilization of maternal health care services by women in Nigeria. These include; the high cost of services, cultural barriers, religious inclinations, attitude of health workers, distance from health facilities among others [4,8,10,11]. Childbirth experience of women will determine their future utilization and recommendation of hospital delivery to other women and yet not many studies have been conducted in Nigeria on maternal satisfaction with services [9,12].

Worldwide there have been constructive efforts to assess and subsequently improve the quality of maternal healthcare in health facilities in the last two decades which has led increase in importance being given to opinions, aspirations, expectations and actual experiences of women that use these facilities [13]. Although, assessing for maternal satisfaction may not be easy due to its multidimensional nature; because clients may be satisfied with some selected aspects of care and not minding others, maternal satisfaction is critical for quality assurance in maternal health care service delivery [14]. Hence the World Health Organization (WHO) recommends the evaluation of satisfaction by the women so as to help improve quality and effectiveness of maternity care services [10,15-17].

It is for this reason that this assessment is considered germane in Nigeria, a developing nation. The findings of the study were to provide informed recommendations and public health policy formulation, strategies and interventions that will eventually enhance institutional deliveries in Nigeria thereby not only improving maternal and child health but also reducing maternal deaths.

Methodology

Study Design

Systematic review of Literature that were peer reviewed or grey literature that was relevant to the study theme. The review followed the PICO model or frame work for systematic reviews. The population studied was women who delivered in health facilities in Nigeria whether at primary, secondary or tertiary level of care. Intervention was the delivery process which entails treatment, information, interpersonal relationship, and impact of infrastructure. The reports of women who delivered in health facilities were compared with those who delivered in un-orthodox centers. Outcome measures were the satisfaction of the women using the domains studied which included; physical environment, interpersonal issues, availability of drugs and supplies, access to health facilities.

Study Setting

It was focused on studies conducted on satisfaction of women with delivery services in health facilities in Nigeria. The country which is located in West Africa is the most populous black nation in the world with a population of about 200 million people. Maternal and child health services are offered at primary, secondary and tertiary levels. This service includes antenatal care, intra-partum care and post-partum care, family planning, child immunization and other reproductive health services.

Inclusion and Exclusion Criteria

Cross-sectional or cohort studies, some quantitative and others qualitative conducted on maternal satisfaction with delivery services in Nigerian health facilities. Therefore, the population was Nigerian women of reproductive age that had a birthing experience at primary, secondary or tertiary facility. They were also compared with those who delivered elsewhere. All included studies were published in English language. Those with no abstract or full text, editorials, anonymous authors, conference papers, lecture notes and incomplete data were excluded. Also excluded were those done on non-Nigerian population, focused on antepartum care and non-English. Also, those that did not test the outcome measures of physical environment, interpersonal issues, accessibility and availability of drugs and supplies were excluded.

Search Strategy

This was an extensive electronic literature search using different databases and search engines including Google, PubMed/Medline, Google scholar, web of science, EMBASE, Cochrane library. Report types considered were journal articles, book chapters, grey literature reports and academic theses provided that they reported a full account of either quantitative or qualitative research methods. Search terms used were “Maternal satisfaction with delivery services”, OR “Women’s satisfaction with childbirth services” AND “delivery in Nigerian health facilities”, OR “Women’s perception of satisfaction with hospital Childbirth experiences in Nigeria”, AND “satisfaction with maternity services”, “factors affecting satisfaction with child birth”. Other ways were; the manual search and review of reference lists of the included studies. Hand searching of the journals was also done as well as grey literature and interviews of experts. The period of these studies was restricted to between 2000 and 2021 to ensure that the findings were recent.

Quality and Eligibility Assessment

This was a diligent check through the full-text articles to further evaluate the quality and eligibility of the studies. Consideration was given to journal articles published by reputable publishers as high-quality research, and therefore they were included in the review: Thus, reliability of data was checked for and repetitions were also rejected.

Study Selection Process

This was a two-stage process in which the first stage involved screening of abstracts of identified studies by the researcher for relevance to the topic, based on the inclusion and exclusion criteria. In the second stage, full-text papers were reviewed for relevance and inclusion in the review work. Where there were doubts, the researcher referred the concerned abstracts/full texts to the two other researchers and decision to accept the articles were based on the inputs of the other researchers.

Risk of Bias in Assessment of Articles

Each article selected was considered to be of high, moderate or low quality. Articles were not rejected due to the study design limitations that could have existed. The priority was the achievements of the aim and objective of the study which was adjudged to have addressed the study questions and the hypotheses. So the overall interpretation became more important than technical criteria used for data collection and analysis. It was also important to take into cognizance the difficulty of research methodology for assessing the likelihood of publication or dissemination bias in qualitative studies or mixed studies even though such biases are well known to exist.

Outcome Measurement of Interest

The outcome data was satisfaction with delivery services and factors related to satisfaction with delivery services. Satisfaction was considered along the lines of prompt attention to patients, environmental issues (cleanliness, how tidy and organized, good toilets), interpersonal issues (politeness, respect and regards to patients, privacy, orientation, emotional support) and information (treatment, counselling, results of exams, hygiene, breast feeding etc.).

Data Extraction and Analysis

Data extraction was done from the included studies in Word document using a table. It included the first author, year of publication, study setting, study design, data collection method, and sample size, prevalence of satisfaction, study region, outcome measure and associated factors for satisfaction.

Table 1: Description of included studies for systematic review

|

S/N |

Authors/year |

Study setting |

Study design |

Data collection method |

Sample size |

Prevalence of maternal satisfaction (%) |

Town/state |

Outcome |

Factors associated with satisfaction |

| 1 | Somade & Ajao,

2020 |

PHC | Cross-sectional | Structured

Questionnaire |

380 |

66.7% |

Ogun | Maternal satisfaction | Communication skill, Accessibility of care, Midwives’ availability and professionalism, Cost of services |

| 2 | Timane et al,

2017 |

PHC | Cross-

Sectional |

Structured

Questionnaire |

250 |

96.7% |

Sokoto | Client

satisfaction |

Waiting time, environment, cleanliness of toilets, availability of water, treatment and outcome |

| 3 | Lawali & Lamide

2020 |

Teaching hospital | Cross-

Sectional |

Structured

Questionnaire |

158 |

97.7% |

Sokoto | Maternal

satisfaction |

Waiting time, courtesy, privacy, competence, treatment given, support, sex of health worker |

| 4 | Okonofua et al

2017 |

Teaching

Hospitals |

Cross-

sectional |

FGD |

40 |

Low |

Zaria, Mina, Abuja, Oyo, Benin, Kano, Abeokuta, Ibadan | Women’s

satisfaction |

Staffing, electricity, water, attitude of staff, waiting time, availability of drugs, attention, support |

| 5 | Uzochuckwu et al, 2014 | Community | Cross-

sectional |

Structured

Questionnaire |

405 |

90.6% |

Enugu | Maternal

satisfaction |

Availability of drugs, physical condition of facilities |

| 6 | Sayyadi et al,

2021 |

Hospitals | Cross-

sectional |

Structured

Questionnaire |

438 |

67.6% |

Kano | Maternal

satisfaction |

Supplies, competence of staff |

| 7 | Ilesami &

Akinmeye, 2018 |

PHC | Cross-

Sectional |

Questionnaire |

66 |

98.5% |

Ibadan | Mother’s

satisfaction |

Waiting time, staffing, attitude of staff, environment, water, supplies, distance to facility, competence |

| 8 | Ajayi, 2019 | Teaching

Hospital |

Cross-

Sectional |

Questionnaire |

57 |

66.7% |

Ibadan | Mother’s

satisfaction |

Infrastructure, staffing, medicine, equipment |

| 9 | Anikwe et al,

2019 |

Hospitals | Cross-

sectional |

FGD

Interviews |

1227 |

97.1% |

Ondo, Ekiti,

Nasarawa |

Maternal

satisfaction |

Cleanliness of health facility, attitude of staff, privacy, supplies and medicine |

| 10 | Oyo-Ita et al,

2007 |

Teaching

Hospital |

Cross-

sectional |

Questionnaire |

250 |

59.3% |

Abakaliki | Women’s

satisfaction |

Environment, attitude of staff, communication, care |

| 11 | Odetola &

Fakorede, 2018 |

Hospital | Cross-

sectional |

Questionnaire |

144 |

97.2% |

Calabar | Mother’s

satisfaction |

Sanitation of facility, attitude of staff, basic amenity |

| 12 | Nnebue et al,

2021 |

PHC | Cross-

sectional |

Questionnaire |

280 |

93.2% |

Nnewi | Maternal

satisfaction |

Waiting time, cost, attitude of staff |

| 13 | Yakubu et al, 2020 | UDUTH | Cross-sectional | Questionnaire |

158 |

90.0% |

Sokoto | Maternal satisfaction | Medical supplies/drugs, delivery beds, waiting rooms, toilets/showers, number of health workers, lab services. |

Ethical Clearance

Ethical clearance was not applicable in this study being a literature review work.

Results

Search Outcome

A total of 108 journal articles were retrieved after the search and out of these, 33 were eliminated due to repetitions and not been directly related to the topic. Amongst the ones retained, 31 were dropped because they were studies done for maternal satisfaction in developing countries and not limited to Nigeria. Forty four (44) journal articles were eventually picked for the review but after further screening only 13 satisfied the eligibility criteria set for the study while those that do not qualify due to a slightly different approach in methodology were discarded (Figure 1).

Figure 1: Flow diagram summarizing searches

Characteristics of Studies Selected for Review

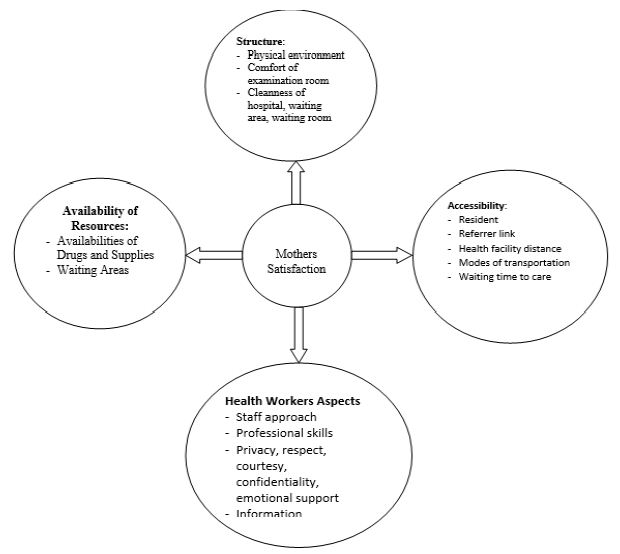

All selected articles were studies that focused on maternal/mother’s or client satisfaction with delivery services in Nigerian health institutions. Some were conducted in primary health care centers, others secondary health facilities or teaching hospitals. They were all cross-sectional, questionnaire based, with in-depth interviews and some focused group discussions. They cut across the entire regions of the country in fact one particularly involved all the six geopolitical regions of Nigeria. They were all published in reputable journals with complete data and English language (Figure 2).

Figure 2: Conceptual frame work for maternal satisfaction

Women’s Overall Satisfaction with Care

Eight (8) of the studies reported the prevalence of women’s satisfaction with delivery services to be over 90%. Three (3) reported slightly over 60%, one less that 60% and one did not report prevalence but documented a low satisfaction. From this report, there was an overall good satisfaction with the quality of care rendered in the health facilities studied.

Factors Associated with Maternal Satisfaction

A large spectrum of factors influencing maternal satisfaction emerged from this review. They are summarized here according to the Donabedian framework of structure, process and outcome, besides access, socioeconomic concerns and other factors.

Physical Environment of the Health Facilities

Eleven (11) of the studies have women’s assessment of the physical environment as a perceived factor that was associated with their satisfaction. Five (5) of them reported satisfaction of the women with environment of the facilities while six reported to be dissatisfactory by the women’s perception [18-25]. Two studies from Sokoto (North-west), one from Ibadan( South-west) and one from Abakaliki (South-east) and one from Calabar (south-south) reported that the women were satisfied with the cleanliness of the consulting rooms, waiting rooms, toilets and water supply [19,20]. However the others reported substandard facilities with dirty environment, irregular electricity, inadequate water supply, bad toilets, bad bathrooms and inadequate infrastructures [25].

The study done in secondary and tertiary health institutions in six geopolitical zones with cities such as – Zaria, Mina, Abuja, Oyo, Benin, Kano, Abeokuta, Ibadan involving a cross-section of women through in-depth interviews and focused group discussions reported that in almost all the cities women were not satisfied with facility based delivery services due to substandard infrastructure, unclean environment, lack of privacy, inadequate water supply and electricity supply [9]. They said these deficiencies in health institutions is what discourage most of them from utilizing orthodox facilities for delivery but rather prefer traditional facilities [9].

Availability of Human Resources or Manpower

In almost all the studies including those that reported satisfactory quality of care as perceived by the women there was a consistent dissatisfaction with the adequacy of the number of staffing. Inadequate manpower was considered to be responsible for long waiting time, poor attention to patients, lack of social support, poor attitude, inadequate education and information provided to the patients when needed. A study done in Sokoto reported that the women were dissatisfied with the sex of the health worker who attended to them [20].

Availability of Medicines, Supplies and Services

Only four (4) studies reported satisfaction by the women’s assessment for the supply of drugs and other medical provisions for their treatment. Most of them were not satisfied but complained of inadequacy or absence of basic medications and commodities and lamented of the high cost of the available drugs. A study in Kano reported that the women in rural compared with urban communities were more dissatisfied particularly with finance, shortage of drugs, hospital equipment, manpower deficiency and transportation difficulties [26].

Interpersonal Relationship

Out of eight (8) of the studies that reported on attitude of health workers towards the women, five (5) of them carried the report that the women were dissatisfied with the interpersonal relationship that exist between the medical personnel and their clients. Some women have reported verbal and physical insult against them [9]. Lack of respect and courtesy toward the women. The focused group discussions in the regional study revealed women complaining of maltreatment either before, during or after delivery. For instance in Edo a participant complained of harassment even when patients asked questions about their care [9]. However, two reported that hospital staff were respectful, gave orientation to patients, explained treatment procedures, sought for the opinion of the patients during treatment and gave the patients support.

Discussion

The general trend of maternal satisfaction with delivery services in Nigerian health facilities suggest a high satisfaction in most of the studies reviewed. The report is similar to those from southern Ethiopia (95%), multi-regional study in Ghana, Guinea, and Myanmar 88.4% but higher than reports from central Ethiopia (3.6%) and South Africa 55% [27].

However, the reported studies showed that a deeper and critical interrogation of the women through in-depth interviews and focused group discussions on maternal care following recommendations by the world health organization (WHO) and elaborated by Donabedian tool, revealed the obvious gaps in the health care system [21]. This probably suggests that the women may have not appreciated what their rights and privileges are due to lack of personal awareness and knowledge, although Nnebue et al. (2014), reported otherwise [28].

However, the regional study by Okonufua et al. (2017) showed so much knowledge and information that had been gathered by the women overtime. They were able to elucidate the challenges in the health sector and proffered solutions and recommendations which included; the improvement and expansion of hospital facilities, better organization of clinical services to reduce delays and mis-management, the training and re-orientation of health workers and the education/counseling of women [9]. These recommendations for rectification are consistent with previous recommendations reported in other studies in developing nations such as Ethiopia [2,29,30].

Physical Environment

Although some of the studies like the ones in PHCs in Ogun state suggested that mothers were satisfied with the physical condition of the environment, most of the reviewed studies reported dissatisfaction. In Sokoto, Kano, Minna, Ibadan and Enugu there were lack of satisfaction with electricity supply, adequacy of clean water, toilet facilities, bathrooms, waiting areas, consulting rooms and bed spaces for admission [16,19,20].

In some reports, women were said to sit on vehicles of doctors awaiting consultation because of inadequate chairs in the waiting area, some had delivered on the floor, and other situations patients bring water from home for their treatment [9,16,20]. The situation was found to be worse in the report that compared urban and rural health care service delivery as reported by Sayyad et al. (2021) in Kano [16]. These findings are typically synonymous to what is reported in other developing nations like Ethiopia, Ghana and Tanzania [31]. Women were prompt to say these were some of the reasons they do not want to utilize health facilities for delivery [17,32].

A qualitative study in Ghana in which in-depth interviews were conducted revealed some women complaining bitterly of the delivery conditions being grossly below their expectations. One women said; “I was not comfortable with the condition of the bed there, especially the mattress I slept on. The mosquito nets also need to be changed because they were not good enough for people to sleep inside them” [33]. In a study by Darebo et al. (2016) in Southern Ethiopia, some women were very unhappy with ward cleanliness. A 33-year-old woman from Soddo said: “… though I was very satisfied with the care all the way through, I felt embarrassed when I had to sleep on a couch which was left unclean from a previous birth, with some blood and secretions visible on top of the bed”. A shortage of water and dirty toilets was the main source of dissatisfaction for several women. This was particularly exacerbated by a disaster that led to interruption in power supply in the area for several days.

These are well known challenges that confront the health sector in developing countries like Nigeria. The issue of bed shortage was also a big problem in the public hospitals. According to the women surveyed, they were discharged as quickly as possible due to lack of beds or broken beds. The health sector leadership in developing nations should make more efforts in improving on the sanitary conditions of the hospitals and meeting the infrastructural needs and provision of basic amenities [2,17].

Interpersonal Relationship

The study in selected areas in Ogun State showed that the main perceived factor influencing quality of health care service was staff conducts and practice (94.6%). The women were satisfied with communications skill of the health personnel (67.6%) that attended to them [18]. This is contrary to the report from a study in Erbil City in Iraq by Ahmed (2020). The study in Sokoto [20] also, reported satisfaction with health worker attitude. Similarly, in Ondo, Ekiti and Nasarawa states where user fee removal policy was practiced, the women were also satisfied with health worker attitude [22]. High satisfaction rate was also seen in the survey of PHC centers in Ibadan which showed that 95.6% of the women were satisfied with the attitude of health workers whom they described as respectful and courteous, while 86.4% were happy with pain management [34].

However, further review of the studies show that although few reported satisfaction with conduct and practice of health workers, most were dissatisfied. Mothers reported maltreatment, disrespect and lack of courtesy by health workers [11]. In the study at Enugu south-eastern Nigeria, a lot of the participants complained of the unfriendly attitudes of the health workers [35]. Although they opined that the health personnel differs in character with some being courteous while some were not [35]. In the view of one of the client, “I think the attitude of our nurses is bad because they have no respect or mercy for a patient and they insult patients without been provoked” [35].

The clients went ahead to offer some explanations why staff behavior might be bad. Some participants felt that “easy fatigability as a result of stress on the few staff makes then easily irritable, coupled with the uncoordinated and misguided behavior of the patients who argue and jump queues” [11,35]. However, the most common explanation was that the health workers who are used to seeing illness and deaths have become insensitive to patient needs [35].

These findings were worse with the regional studies reported by Okonofua et al. (2018). In one of the narrative by a patient during the focused group discussion, in Kano the participant lamented: “they do not give enough attention to women in labour, some women will be shouting and crying and they still will not attend to them”. Several studies done in different parts of Nigeria report a lot of maltreatment [11,36]. Several women reported unfriendly, insensitive, poor and negative attitude towards them in their last deliveries by a range of 11.3% to 70.8% of women in eight cross-sectional surveys in Enugu , South-east, Nigeria [37] some in Benue State, North-central Nigeria (Orpin et al. 2018). Studies have shown that women who were maltreated are less likely to be satisfied [38,39].

A multi-country community based study done in Ghana, Myanmar, Guinea and Nigeria which reported verbal and physical abuse against the women showed that they were more likely to report less satisfaction with care [39] and this makes so many women prefer delivery at TBAs whom they say are more compassionate and supportive [40]. The same has been reported in Nigeria; for instance in Ota, Ogun State in South-western Nigeria [6]. This perhaps clearly shows the difference between actual qualities of care provided and perceived quality of care by the women [4].

Another study done in Lagos comparing satisfaction with the quality of care between faith-based and public facility care reported the women were more satisfied with the faith based health care services due to perceived effectiveness [41]. What this means is that, even if the modern health facilities in Ota have expert practitioners with internationally recognized good practice, the maternal deaths might unfortunately still be on the rise due to poor utilization, because women’s perception of ‘quality’ influences health service utilization[4,6,42].

Similarly, in Northern Nigeria, the practice of Purdah (female seclusion) is very common. In this practice, women are isolated and encouraged to give birth at home [6]. Many in these settings believe that allowing an outsider help with delivery could be disrespectful [6,42]. Thus, even if maternal health institutions exist in this region, it might not improve health outcomes because of people’s beliefs and culture [6,42].

Moreover, raising awareness on the existence of a maternal health facility, making it accessible and affordable does not always result to its utilization [6]. This has been shown for example, in Giwa Local Government Area (LGA) of Kaduna State North-western Nigeria. Despite living close to a health facility with free maternal health services, majority of the women were not utilizing the facility for child delivery [6]. One of the reasons for the poor use of formal health system in that community is the belief that health care providers have a negative attitude; consequently, many women would rather give birth at home or at a traditional health center [6].

Thus, even though the evidence towards reducing maternal mortality through access to skilled pregnancy care are largely relevant, it remains inadequate in ensuring a substantial decline in maternal deaths in Nigeria [6]. Improving the quality of health services goes beyond assessing only the supply aspect of care [4,6]. Some authors noted that even if the standard of services in Nigerian primary, secondary or tertiary health facilities is improved, maternal mortality may still be high [6]. This is because an increase in the quality of care provided at a health institution does not always translate to an increase in utilization of the health services by women [6].

Availability of Drugs and Supplies

Nnebue et al. (2014) reported the satisfaction with drugs availability and other supplies in a survey in PHCs in Nnewi amongst 78% of participants [28]. Odetola and Fakorede, 2018 reported that 93.3% of the women in Ibadan were satisfied with supplies, although 68% of the nurses were said to have complained of lack of certain instruments to work with [34]. This finding is similar to that of the report from Ethiopia by Asres et al. (2018) [43]. The challenge in developing nations is that of “out of stock” syndrome. The few inequitably distributed health centers are usually not well equipped and lack basic supplies for efficient service delivery.

Studies have shown that the private health facilities do have better supplies than public facilities [44], however the latter is usually not within the capacity of the not well to do people when it comes to the issue of affordability [44].

Accessibility to the Health Facilities

The satisfaction of the women was indirectly connected to how close the facility was to their places of residence [32,41]. A study had demonstrated that women who live closer to the health facility in which case it will take just about 30 minutes to locate the facility and do also have a means of transportation are more likely to deliver in the facility than those it will take an hour or more and do not have easy access by means of transportation [17,32,45]. On arriving the hospital, promptness of care was judged to be a criteria for satisfaction by the women while increase waiting time was a determinant for dissatisfaction as was reported by a study in Ethiopia [29,32,45]. A study done in Kenya reported that private facilities do have a lesser waiting time compared with public facilities. The report has it that a higher proportion of clients from private facility 98.1% were attended within 0 ± 30 minutes of arrival to the facility as compared to 87% from public facility [41,44].

Biosocial Factors and Maternal Satisfaction

Although majority of the studies for the assessment of perceived satisfaction with care by the women did not include biosocial factors, two particularly done in Kano by Sayyadi et al. (20210 and Ibadan by Otedola and Fakorede (2018) reported on the impact of level of education and economic status on satisfaction [26,34]. They opined that, most of the studies reporting high satisfaction were amongst women with relatively lower levels of education and economic status. Dis-satisfaction with maternity care services were seen more among women with higher socio-economic status and level of education. This could be as a result of the exposure and higher expectations of care among the higher class women. Coasta et al. (2019) in Brazil reported that the women’s birth satisfaction was positively associated with age, number of children, education level and income [46]. They found out that those who had more personal control during childbirth, lower labour pains, no underlying medical problems during delivery and more social support or labour companionship showed higher birth satisfaction levels [46].

Cultural Diversity in Childbirth Interplay

One prominent area that affects satisfaction of clients with maternal health care services that was not adequately focused on in the reviews but is worthy of mentioning is the diversity of cultures across ethnic divide in Nigeria [6,42]. Globally, it has been reported that the culture of the skill birth attendant and profession, client and the practice setting affects perceived quality of care [6,42]. There are about 374 ethnic groups, in Nigeria with different cultures which creates a challenge to the healthcare provider because these cultural variations are believed to affect the birth process [6,42]. This explains why for instance the clients could prefer certain sex of the healthcare giver to attend to them, patronage of either health facility or un-orthodox facility, interpersonal disagreements, pain coping/management issues and place of birth etc. [6,42]. It is therefore crucial for birth attendants to have a good knowledge of culturally bound behaviors in order to facilitate a satisfying birthing experience by the culturally diverse women of Nigeria. In the light of this assertion, it will be appropriate to train skill birth attendants on cultural interplay mechanism that affects client’s satisfaction with delivery services in health facilities.

Conclusion

Although overall satisfaction with health facility delivery services was good, there was some dis-satisfaction expressed by the women in certain domains. These factors that the women identified as causes of dissatisfaction with maternal care included; dirty hospital environment, inadequate and dirty toilets, inadequate water supply, and poor interpersonal relationship with health care givers in which patients have been verbally or physically maltreated. Also location/distance of health facilities, increased cost of some services and lack of drugs. For these reasons some women prefer to deliver outside orthodox health facilities. A digitalized feedback system, strict patient care pathways as well as periodic audits are compulsory. More regional research on maternal satisfaction is however recommended to capture particularly factors such as culture and place of residence whether urban or rural to appreciate their influence on maternal satisfaction.

Recommendations

To improve on the health care delivery system, the following recommendations become critical.

Physical Environment

- Health facilities should be kept clean and tidy. Environmentalist and cleaners as staff or contractors should be engaged for this responsibility of continuous maintenance of a decent hospital environment.

- Availability of adequate and clean toilets and water should be ensured regularly by health facility staff. A dedicated electricity line will guarantee regular supply of electricity to power equipment and machines for uninterrupted service delivery.

- Provision of sufficient seats in waiting areas for the clients as they await consultations as well as enough beds for admission should be ensured.

- Employment of more staff of different cadre to reduce burn out syndrome. Hopefully this could reduce the tension, irritability and anger exhibited by health workers towards patients as a result of stress of work.

- Deliberate training and retraining of health workers at maternal health care centers to improve their performance and quality of care devoid of maltreatment to patients. They should rather be able to counsel, inform and request for patient’s input into their care.

- There is need for continuous upgrading and refinement of patient care communication skills of staff in order to make them friendlier, more prompt and responsive to patients.

- There should be improvement on the hospital organization so as to reduce delays and long waiting time for consultations. Appointments to patients in batches could be considered as a strategy in this regards. Also computerization of hospital records and at every department of service delivery.

- Continuous monitoring of clients’ satisfaction with all aspects of care could aid in improvement of the quality of services.

- Provision of adequate compensation packages and appropriate incentives to health personnel to increase their commitment and motivation to work.

- Maintenance of adequate monitoring and supervision of health personnel to ensure the proper delivery of services.

- Digitalized feedback system and periodic audit is critical.

- The Ministry of Health at both the federal, state and local governments should consistently provide adequate supplies, equipment and drugs for providing maternal healthcare services in all the health facilities.

- The drugs and cost of services should be made more affordable. Maternal health free services could be considered. The national health insurance scheme (NHIS) could also help in this regard.

- Creation of awareness through mass media, religious gatherings and social functions about the need to utilize institutional maternal health services, and about the dangers associated with using traditional birth attendance.

- The government, NGOs, community development efforts should be stepped up in the provision and equitable distribution of health facilities that are well manned by skill birth attendants and optimally equipped for efficient service delivery.

- Infrastructural development such as in provision of access roads and means of affordable transportation should be given priority to enable women access care.

- Funding of the health sector in Nigeria should as a matter of urgency is improved upon through legislation.

- Finally, Caregivers need to fully understand the expectations that patients have for their care, and provide service that is consistent with those expectations.

- Babure ZK, Assefa JF, Weldemarium TD (2019) Maternal Satisfaction and Associated Factors towards Delivery Service among Mothers Who Gave Birth at Nekemte Specialized Hospital, Nekemte Town, East Wollega Zone, Oromia Regional State, Western Ethiopia, 2019: A Cross-sectional Study Design. J Women’s Health Care 9: 489.

- Darebo TD, Abera M, Abdulahi M, Berheto TM (2016) Factors Associated with Client Satisfaction with Institutional Delivery Care at Public Health Facilities in South Ethiopia”. J Med Physiol and Biophysics 25: 19-28.

- Edaso AU, Teshome GS (2019) Mothers’ satisfaction with delivery services and associated factors at health institutions in west Arsi, Oromia regional state, Ethiopia”. MOJ Women’s Health 8: 110-119.

- Chizoba N, Tobiloba O, Chigozie N (2017) Factors Influencing the Choice of Health Care Provider during Childbirth by Women in Ibadan, Oyo State, Nigeria. Int J Caring Sc 10: 511-521.

- Bitew K, Ayichiluhm M, Yimam K (2015) Maternal Satisfaction on Delivery Service and Its Associated Factors among Mothers Who Gave Birth in Public Health Facilities of Debre Markos Town, Northwest Ethiopia. BioMed Res Int 1-6. [crossref]

- Ope BW (2020) Reducing maternal mortality in Nigeria: addressing maternal health services perception and experience. J Global Health Reports 4: e2020028.

- Demis A, Getie A, Wondmieneh A, et al. (2020) Women’s satisfaction with existing labour and delivery services in Ethiopia: a systematic review and meta-analysis. BMJ Open 10: e036552.

- Adegbe OE (2021) Factors that determine the place of Childbirth in Lagos State, Nigeria’. Walden Dissertations and Doctoral Studies 10628: 2021.

- Okonofua F, Ogu R, Agholor K, Okike O, Abdus-Salam R, et al. (2017) Qualitative assessment of women’s satisfaction with maternal health care in referral hospitals in Nigeria. Reprod Health 14: 44. [crossref]

- Oikawa M, Sonko A, Faye EO, Ndiaye P, Diadhiou M, et al. (2014) Assessment of Maternal Satisfaction with Facility-based Childbirth Care in the Rural Region of Tambacouda, Senegal. Afr J Reprod Health 18: 95-104.

- Bohren AM, Vogel JP, Tunçalp O, Fawole B, Titiloye MA, et al. (2017) Mistreatment of women during childbirth in Abuja, Nigeria: a qualitative study on perceptions and experiences of women and healthcare providers. Reprod Health 14: 9. [crossref]

- Babalola TK, Okafor IP (2016) Client satisfaction with maternal and child health care services at a public specialist hospital in a Nigerian Province. Turk J Public Health 14: 117-127.

- Amu H, Nyarko SH (2019) Satisfaction with Maternal Healthcare Services in the Ketu South Municipality, Ghana: A Qualitative Case Study”. BioMed Research International 2019: 2516469. [crossref]

- Mocumbi S, Högberg U, Lampa E, Sacoor C, Valá A, et al. (2019) Mothers’ satisfaction with care during facility-based childbirth: a cross-sectional survey in southern Mozambique”. Pregnancy and Childbirth 19: 303. [crossref]

- Panth A, Kafle P (2018) Maternal Satisfaction on Delivery Service among Postnatal Mothers in a Government Hospital, Mid-Western Nepal. Obstet Gynaecol Int 2018: 1-11. [crossref]

- Sayed W, ElAal DEM, Mohammed HS, et al. (2018) Maternal satisfaction with delivery services at tertiary university hospital in Upper Egypt, is it actually satisfying? Int J Reprod Contracept Obstet Gynaecol 7: 2547-2552.

- Debela AB, Mekuria M, Kolola T, Bala ET, Deriba BS (2021) Maternal Satisfaction and Factors Associated with Institutional Delivery Care in Central Ethiopia: a Mixed Study. Patient Preference and Adherence 15: 387-398. [crossref]

- Somade EC, Ajao EO (2020) Assessing Satisfaction with Quality of Maternal Healthcare among Child Bearing Women in Selected Primary Healthcare Centers in Ogun State, Nigeria. Int J Acad Res Bus Arts Sc 2: 200-210.

- Timane AJ, Oche OM, Umar KA, et al. (2017) Clients’ satisfaction with maternal and child health services in primary health care centers in Sokoto metropolis, Nigeria. Edorium J Matern Child Health 2: 9-18.

- Lawali Y, Lamide A (2020) The Health Workers and Delivery Process Related Maternal Satisfaction with Delivery Services at UDUTH Sokoto, Nigeria. Perception in Reprod Med 3: 256-260.

- Ilesami RE, Akinmeye JA (2018) Evaluation of the quality of postnatal care and mothers’ satisfaction at the university college hospital Ibadan, Nigeria. Int. J Nurs Midwifery 10: 99-108.

- Ajayi AI (2019) I am alive; my baby is alive”: Understanding reasons for satisfaction and Dissatisfaction with maternal health care services in the context of user fee removal policy in Nigeria. PLoS ONE 14: e0227010. [crossref]

- Anikwe CC, Egbuji CC, Ejikeme BN, Ikeoha CC, Egede JO, et al. (2019) The experience of women following caesarean section in a tertiary hospital in Southeast Nigeria. Afr Health Sci 19: 2660-2669. [crossref]

- Oyo-Ita AE, Etuk SJ, Ikpeme BM, Ameh SS, Nsan EN (2007) Patients perception of Obstetrics practice in Calabar Nigeria. Nig J Clin Pract 10: 224-228. [crossref]

- Yakubu L, Muhammad F, Zulkiflu MA, et al. (2020) Health Facility Related Maternal Satisfaction with delivery Services at UDUTH Sokoto. World J Pharma Med Res 6: 04-08.

- Sayyadi BM, Gajida AU, Garba R, Ibrahim UM (2021) Assessment of maternal health services: a comparative study of urban and rural primary health facilities in Kano State, Northwest Nigeria. Pan Afri Med J 38: 1-13. [crossref]

- Oosthuizen SJ, Bergh A-M, Pattinson RC, Grimbeek J (2017) It does matter where you come from: mothers’ experiences of childbirth in midwife obstetric units, Tshwane, South Africa. Rep Health 14: 1-11. [crossref]

- Nnebue CC, Ebenebe UE, Adinma ED, Iyoke CA, Obionu CN, et al. (2014) Clients’ knowledge, perception and satisfaction with quality of maternal health care services at the primary health care level in Nnewi, Nigeria. Niger J Clin Pract 17: 594-601. [crossref]

- Fikre R, Eshetu K, Berhanu M, Alemayehu A (2021) What determines client satisfaction on labor and delivery service in Ethiopia? Systematic review and meta-analysis. PLoS ONE 16: e0249995. [crossref]

- Amdemichael R, Tafa M, Fekadu H (2014) Maternal Satisfaction with the Delivery Services in Assela Hospital, Arsi Zone, Oromia Region. Gynecol Obstet (Sunnyvale) 4: 257.

- Gashaye KT, Tsegaye AT, Shiferaw G, Worku AG, Abebe SM (2019) Client satisfaction with existing labor and delivery care and associated factors among mothers who gave birth in university of Gondar teaching hospital; Northwest Ethiopia: Institution based cross-sectional study. PLoS ONE 14: e0210693. [crossref]

- Ayamolowo LB, Odetola TD, Ayamolowo SJ (2020) Determinants of choice of birth place among women in rural communities of south-western Nigeria. Int J Afr Nursing Sc 13: 1-7.

- Amu H, Nyarko SH (2019) Satisfaction with Maternal Healthcare Services in the Ketu South Municipality, Ghana: A Qualitative Case Study. BioMed Research International 2019: 2516469. [crossref]

- Odetola TD, Fakorede EO (2018) Assessment of Perinatal Care Satisfaction amongst Mothers Attending Postnatal Care in Ibadan, Nigeria. Annals of Global Health 84: 36-46. [crossref]

- Uzochukwu BSC, Onwujekwe OE, Akpala CO (2004) Community Satisfaction with the quality of Maternal and Child Health Services in Southeast Nigeria. East Afr Med J 81: 293-299. [crossref]

- Dahiru T, Oche MO (2013) Determinants of antenatal care, institutional delivery and postnatal care services utilization in Nigeria. Pan Afr Med J 21: 321. [crossref]

- Ishola F, Owolabi O, Filippi V (2017) Disrespect and abuse of women during childbirth in Nigeria: A systematic review. PLoS ONE 12: e0174084. [crossref]

- Orpin J, Puthussery S, Davidson R, Burden B (2018) Women’s experiences of disrespect and abuse in maternity care facilities in Benue State, Nigeria. BMC Pregnancy and Childbirth 18: 1-9.

- Maung TM, Mon NO, Mehrtash H, et al. (2021) Women’s experiences of mistreatment during childbirth and their satisfaction with care: findings from a multi-country community-based study in four countries. BMJ Global Health 5: e003688.

- Ebuehi OM, Akintujoye IA (2012) Perception and utilization of traditional birth attendants by pregnant women attending primary health care clinics in a rural Local Government Area in Ogun State, Nigeria. Int J Women’s Health 4: 25-34. [crossref]

- Ogunyemi AO, Ogunyemi AA, Olufunlayo TF, Odugbemi TO (2019) Patient satisfaction with services at public and faith based primary health centers in Lagos State: A comparative study. J Clin Sci 16: 75-80.

- Esienumoh EE, Akpabio II, Etowa JB et al. (2016) Cultural Diversity in Childbirth Practices of a Rural Community in Southern Nigeria. J Preg Child Health 3: 280.

- Asres GD (2018) Satisfaction and Associated Factors among Mothers Delivered at Asrade Zewude Memorial Primary Hospital, Bure, West Gojjam, Amhara, Ethiopia: A Cross Sectional Study. Prim Health Care 8: 293.

- Okumu C, Oyugi B (2018) Clients’ satisfaction with quality of childbirth services: A comparative study between public and private facilities in Limuru Sub-County, Kiambu, Kenya. PLoS ONE 13: e0193593. [crossref]

- Tadesse BH, Bayou NB, Nebeb GT (2017) Mothers’ Satisfaction with Institutional Delivery Service in Public Health Facilities of Omo Nada District, Jimma Zone. Clin Med Res 6: 23-30.

- Costa DDOO, Ribeiro VS, Ribeiro MRC, Esteves-Pereira AP, Sá LGC, et al. (2019) Psychometric properties of the hospital birth satisfaction scale: Birth in Brazil survey. Cad Saúde Pública 35: e00154918. [crossref]

Interpersonal Relationships

Availability of Drugs and Supplies

Accessibility to Health Services

Study Strength and Limitations

The cross-sectional studies done through interviews with the use of questionnaires might have influenced the responses from the participants due to the fact that in most cases the care givers administer them to the clients. Although it was mentioned that, in the training of research assistants it was ensured that efforts were made by these research assistants to assure respondents of confidentiality of their responses. Qualitative data were also used to cross-check the quantitative results obtained from the questionnaires. Even the in-depth interviews through focused group discussion could have been biased for some form of conflict of interest. There were variation in the use of parameters and overall assessment of satisfaction and this non uniformity could have affected the general reporting of findings. The overall satisfaction of hospital delivery services in these studies was found to be suboptimal. Caregivers need to fully understand the expectations that patient have for their care, and provide care that is consistent with those expectations. Future studies should consider gathering more data from a more diverse sample to address the generalizability issue.

Acknowledgement

We acknowledge the advices offered by Jonah Musa, Audu Onyewoicho and Emmanuel Adegbe during the preparation of this manuscript.

References