Introduction

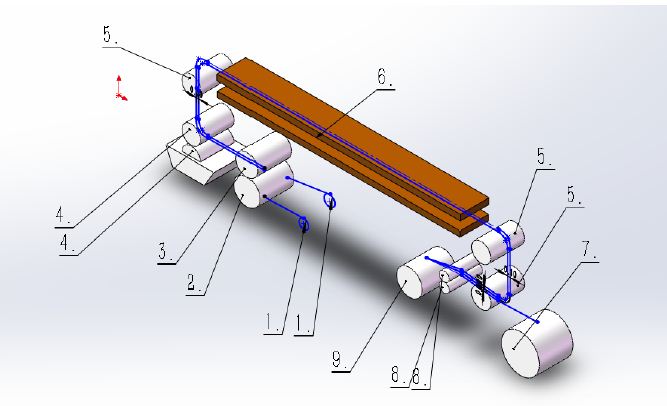

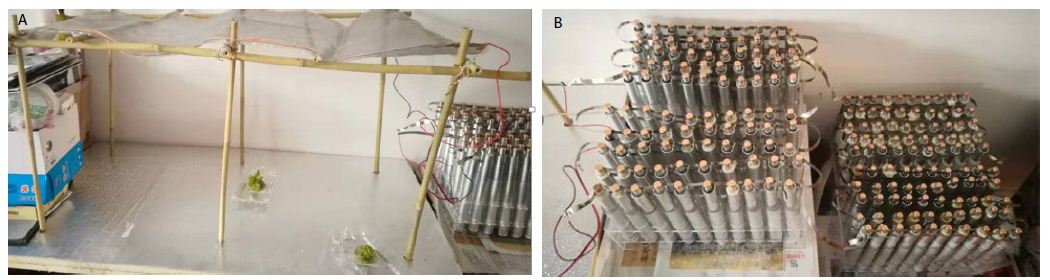

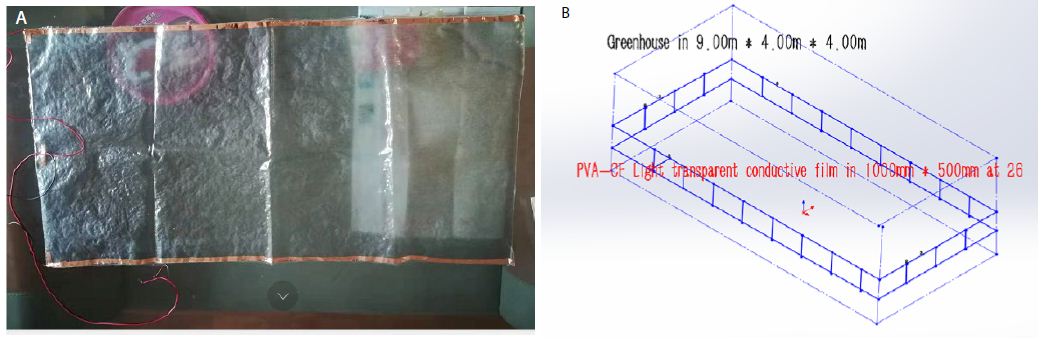

Increasingly, toxicology studies are using toxicogenomics on lines of cultured cells to identify genes whose expression is altered by toxics. However, this approach is not feasible in testicular toxicity, because there is no line of germ cells to respond to this request because the differentiation of germ cells is dependent on interactions with the somatic cells of the testis [1,2]. During the golden age of French research, we have developed and validated two culture systems of germ cells together with Sertoli cells, in bicameral chambers, in a defined culture medium, which maintain the blood testis barrier [3-5] and enable studying the mitotic phase of spermatogenesis, the entire meiotic phase, and the first steps of spermiogenesis over a 4-week culture period in the 20 days old rat [5-7]. These in vitro systems should be a major methodological breakthrough in assessing toxicological potency of chemical compounds on a relatively long time period and enabling the study of many aspects of their mechanism of action while reducing greatly the number of animals needed. It must be noted that our systems of culture in bicameral chamber allow studying the effects of a toxic substance added to the basal compartment of the culture chamber, and thus mimics what could happen in vivo in the testis. Indeed, the cellular junctions, between sertoli cells and between germ cells and Sertoli cells, which are essential for spermatogenesis, are maintained or rebuilt in our systems of culture [3]. Therefore, before reaching the germ cells, in our system, the toxic substance must cross the barrier of Sertoli cells (the main component the blood-testis barrier). By contrast, in “conventional” cultures wells, a compound may be toxic to differentiated germ cells because it is placed directly in contact with these cells, whereas in vivo, it may not have access to the compartment of the seminiferous tubules where this population of germ cells is located.

In addition, the possibility of rather long term cultures of the cells will allow, most often, testing for the reversibility of the observed effects. Our cultures can be analyzed by cell physiology, cytology, biochemical and molecular biological approaches allowing the determination of the mechanisms responsible for the gonadal toxicity or carcinogenic effect of organic or mineral compounds and of nanoparticles.

In these models it is indeed possible to analyze:

- The alterations of the blood-testis barrier.

- Survival/death of somatic and/or germ cells, proliferation of Sertoli cells and spermatogonia (stem cells of spermatogenesis).

- The course of meiotic division (key stage of spermatogenesis during which genetic recombinations occur).

- Cytogenetic abnormalities of germ cells.

- The expression of specific genes in the germ cells or Sertoli cells (transcriptome).

- The peptide profiling of the culture supernatant/cultured cells (proteome).

Our co-cultures can also serve as an original tool for rapid screening test molecules for therapeutic purposes in order to improve a failing male fertility.

The use of a cell population exposed (treated) or not (control group) to the substance allows to get rid of much of the variability between animals that are encountered in testing in vivo and to optimize the power of the tests.

Scientific Validation of these Systems (Physiology)

Two important aspects of the results obtained using in vitro models are their reproducibility (see Figure 7 in Staub et al.) [5], and their relevance to the in vivo (physiological) situation (see below).

The germ cell-Sertoli cell coculture systems that we settled [8-10]; have been carefully validated from the physiological point of view, on many aspects, over the last decades. To our knowledge, there is no other system of culture of male germ cells and Sertoli cells which has been so carefully and extensively validated. Hence, the availability of a physiologically relevant in vitro systems allowing screening the mechanism of action of a large number of potentially toxic/active molecules, at low concentrations on a relatively long period of time, is of an outmost interest. We were the first [5] to show that the whole meiotic process could occur in vitro in a mammal (the rat). This was proven by cytological and cytometrical methods and by germ cell specific gene expression; subsequently we showed that the development of the meiotic step, in vitro, in the testis of pubertal rats was close to what happens in vivo when considering the changes in the cell populations of different ploidy, the gene expression of germ cells, the kinetics of differentiation of BrdU-labeled early or middle pachytene spermatocytes and the levels of apoptosis in the different cell populations, even if the rate of in vitro differentiation of BrdU-labeled spermatocytes slowed down when reaching the stage of middle pachytene spermatocytes [11]. Then, we also showed, there was no significant difference between the percentages of leptotene, zygotene, pachytene, and diplotene stages in 42-day-old rats and on day 16 of culture of seminiferous tubules from 23 day-old rats, indicating a similar development in vivo and in vitro [12].

We showed that FSH and testosterone have positive and somewhat overlapping effects on the meiotic divisions and the post-meiotic expression of a germ cell-specific gene, effects which cannot be related solely to their ability to reduce germinal cell apoptosis [13]. These results have been confirmed by others using KO mouse models [14-16]. We have shown that βNGF and its two receptors are similarly expressed in vivo and under our culture conditions and that both βNGF and TGFβ are able to regulate the second meiotic division of rat spermatocytes by blocking secondary spermatocytes in metaphase (metaphase II) [17,18]. In vertebrates, mature oocytes are arrested at metaphase II until fertilization, because of the presence of a cytostatic factor (CSF) in their cytoplasm. We have shown that Mos, Emi2, cyclin E and Cdk2, the four proteins of CSF are present in male rat meiotic cells. In co-cultures of pachytene spermatocytes with Sertoli cells, β-NGF increases the number of metaphases II, while enhancing Mos and Emi2 levels in middle to late pachytene spermatocytes, pachytene spermatocytes in division and secondary spermatocytes; these results suggest strongly that CSF is not restricted to the oocyte [6,7]. In addition, they reinforce the view that, βNGF by enhancing Mos in late spermatocytes, is one of the intra-testicular factors which adjusts the number of round spermatids that can be supported by Sertoli cells. Actually, the yield of meiosis in vivo is not four round spermatids from one pachytene spermatocyte, but only two round spermatids from one pachytene spermatocyte [19]. Thereafter, we have demonstrated that βNGF and TGFβ1 have a totally redundant effect on this step [6,7]. These results may offer an explanation to the study of Ingman and Robertson who did not observe any effect on male meiosis of the absence of TGFβ1 in SCID null mutant mice [20]. Indeed, male gametes synthesize TGFβ1 with greatest abundance detected in spermatocytes and early round spermatids i.e., precisely, the same germ cell types which synthesize β-NGF [18]. Therefore, it is more tempting to speculate that the absence of effects of TGFβ1 knock out reported by these authors was due to the redundant effect of β-NGF on that step. We have shown that meiotic progression of rat spermatocytes requires mitogen-activated protein kinases of Sertoli cells and close contacts between the germ cells and the Sertoli cells [21,22]. Now, connexin 43 is detected between spermatocytes and Sertoli cells in our cultures [21]. These results fit with a study [23] showing that replacement of connexin 43 by connexin 26 in transgenic mice impairs spermatogenesis leading to the absence of germ cells beyond primary spermatocytes.

Furthermore, we have shown that both meiotic divisions are blocked by pharmacological inhibitors of MPF [24], as could be expected [25]. On the mitotic step of spermatogenesis, we have got results consistent with a role of GDNF in inhibiting the S-phase entrance of a large subset of differentiated type A spermatogonia, together with an enhancing effect of the factor on a small population of undifferentiated (stem cells) spermatogonia [26]. Actually these studies fit quite well with the results of the in vivo studies [27-30]. Further, we have shown that Cx43 gap junctions between Sertoli cells participate in the control of Sertoli cell proliferation and that Cx43 gap junctions between Sertoli cells and spermatogonia are indirectly involved in germ cell number increase by controlling germ cell survival rather than germ cell proliferation [4]. Similarly, by using Sertoli cell conditional Cx43 knock-out mice recent findings have reported that Cx43 is essential for control of Sertoli cell proliferation and differentiation [22,31]. Recently, we showed that our seminiferous tubule culture model, in bicameral chambers, allowed the settlement of the blood-testis barrier (BTB) in 8-day-old male rat cultures and the differentiation of spermatogonia into round spermatids [32]. Taken together, such data support the view that our co-culture systems enable to highlight mechanisms pertinent to the physiological processes. Hence toxicological studies on toxicants, and/or their identified “active” metabolites, performed with these models are most relevant.

Scientific Validation of these Systems (Toxicology)

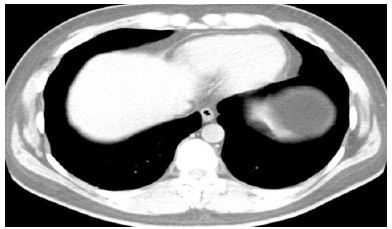

We compared cultures of normal, and irradiated by gamma rays germ cells. In spermatocytes for non-irradiated cultures, the comet assay revealed the presence of breaks of DNA, whose number decreased during the culture, resulting from the involvement of mechanisms of DNA repair associated with meiotic recombination. In irradiated cells, the development of DNA strand breaks was heavily modified. Thus, our model is able to detect genotoxic lesions and/or abnormal DNA repairing [33,34]. Numerous studies have shown the toxicity of heavy metals to spermatogenic cells. A growing body of studies is available regarding the reproductive effects of chromium (VI) in men and animals [35-37], but a detailed analysis of spermatogenesis is not available. Kawanishi et al. have demonstrated that chromium (VI) produce noxious ROS including superoxide anion, singlet oxygen, and hydroxyl radicals through the formation of chromium (V) intermediates [38]. In male mice exposed to chromium (V), the major finding reported was the alteration of permeability of the blood-testis barrier [37]. A significant reduction in semen quality is also observed in male welders occupationally exposed to chromium: decrease in sperm count, mobility and vitality, large number of morphologically abnormal spermatozoa, and these semen changes are dose dependent [36]. Low concentrations of Cadmium are found in food and water [39]. Cadmium loading of the environment is a result of human activities such as fossil fuel combustion, agriculture, and the manufacturing of Nickel-Cadmium batteries. High concentrations of Cadmium in male smokers’ seminal fluid and blood are associated with high oxidative stress and damage. The testis is extremely vulnerable to Cadmium as shown by in vivo and in vitro studies in several mammalian species [40-42]. Cadmium induces poor semen quality and carcinogenicity [43,44]. Although numerous studies describe the testicular damages induced by Cadmium, the mechanisms underlying its toxicity remain not completely understood. Chung and Cheng and Siu et al showed that the blood-testis barrier is particularly vulnerable to Cadmium which inhibits, dose-dependently, the assembly of Sertoli cells tight junction-permeability barrier [42,45]. It was hypothesized that activation of c-JNK signal transduction pathway by Cadmium could lead to general cellular apoptosis in the seminiferous epithelium [46]. Additionally hypothesized was the fact that Cadmium mimics the effects of androgens [47] and has potent estrogen-like activity [48].

We have studied, in our culture systems, the effects of concentrations of chromium or Cadmium similar to those which can be observed in the blood (“physio-toxicology”) on the spermatogenic process. [3,12,49]. The numbers of late spermatocytes and of round spermatids were decreased by chromium(VI) even at the lower concentration (1 µg/L). The percentage of synaptonemal complex abnormalities increased slightly with the time of culture and dramatically with chromium (VI) concentrations. This study shows that chromium (VI) is toxic for meiotic cells even at low concentrations, and its toxicity increases in a dose-dependent manner. The number of Sertoli cells did not appear to be affected by Cadmium. By contrast, spermatogonia and meiotic cells were decreased by 1 and 10 μg/L Cadmium in a time and dose dependent manner. Cadmium caused a time-and-dose-dependent increase of total abnormalities, of fragmented Synaptonemal Complexes and of asynapsis from concentration of 0.1 μg/L. Additionally, we observed a new Synaptonemal Complexe abnormality, the “motheaten” Synaptonemal Complexes. This abnormality is frequently associated with asynapsis and Synaptonemal Complexes widening which increased with both the Cadmium concentration and the duration of exposure. This abnormality suggests that Cadmium disrupts the structure and function of proteins involved in pairing and/or meiotic recombination. These resultsshow that Cadmium induces dose-and-time-dependent alterations of the meiotic process of spermatogenesis exvivo, and that the lowest metal concentration, which induces an adverse effect, may vary with the cell parameter studied. Our systems have been used to study the effects of low doses of Bisphenol A which is a plasticizer commonly found in many consumer and industrial products. Bisphenol A is an endocrine disruptor due to its structural similarity to estrogen and suspected to be harmful to spermatogenesis despite some controversy [50-53]. Our work has shown the deleterious effects of BPA (1 nM and 10 nM) by combining transcriptomic analysis and analysis of synaptonemal complexes by immunocytochemistry. BPA interferes with the course of meiosis by altering the synaptonemal complexes of spermatocytes. The transcriptomic analysis carried out on 120 genes involved in the first prophase of meiosis confirms the immunocytochemical observations because the transcription of 60 of these genes is modified [54].

Lilly Research Laboratories financed a pilot study to evaluate in our model the toxicity of 4 molecules known for their testicular toxicity in in vivo studies: 1,3-dinitrobenzene (at 6 µM or 60 µM), methoxyacetic acid (at 0.5 mM or 2.5 mM), Bisphenol A (at 5 µM or 50 µM) and lindane (at 5 µM or 30 µM). DNB is a nitroaromatic compound used in the production of polymers, pesticides and dyes. In vivo studies have shown that DNB induces severe effects including Sertoli cell vacuolation, spermatocyte depletion and multinucleated and misshapen spermatids [55,56]. MAA is the toxic metabolite of 2-methoxyethanol, a solvent used in printing inks, varnishes, and as a de-icing additive. The toxic effect of MAA on pachytene spermatocytes, has been described in vivo [57,58]. Although Leydig cells are a target of BPA [59], in vitro studies using primary Sertoli cells demonstrated direct targeting through disruption of cell-cell signaling [56-61]. Lindane is a pesticide used in both agriculture and parasiticidal treatment for lice. Lindane induces apoptosis in Sertoli cells as well as in spermatogonia and spermatocytes [62]. Bio-Alter®has made it possible to find the same effects as those described in vivo for these 4 compounds: Sertolian toxicity and disruption of spermatogenesis. In addition, we were able to hypothesize different mechanisms of action explaining their toxicity and also overcome the shortcomings of the European ReProTect project for 1,3-dinitrobenzene and methoxyacetic acid. It should be noted that this project (www.reprotect.eu) included a battery of 14 tests responsible for predicting the disruption of female and male fertility and embryonic development, but that the tests used were unable to predict the toxicity of 1,3-dinitrobenzene and of methoxyacetic acid on spermatogenesis [63]. The results show very close similarities between the results of the published in-vivo studies and the results obtained using the Bio-AlteR® technology. Our model can also respond to the need of some eco-toxycology studies. A large number of environmental factors can pollute air, water and food and may potentiate each other when present as a mixture [32,64,65]. Numerous studies suggest a decline in semen quality in some parts of the world [49,66-73]. This might occur in response to adverse environmental factors [74].

We then Tested Pesticides Selected on the Basis of Their Persistence in Water and Food

Carbendazim is a broad-spectrum benzimidazole fungicide used to prevent and eliminate fungal plant diseases [75]. Carbendazim has been reported to induce, in vivo, a number of testicular alterations such as atrophic seminiferous tubules [76,77], decreased germ cell numbers, sloughing of the seminiferous epithelium [77-80] and abnormal development of the acrosome [81]. Carbendazim has been also reported to induce dysfunction of the somatic Sertoli cells cell by inhibiting microtubule assembly in a colchicine-like manner [75,82-84]. However, the mechanism of action of carbendazim was not fully elucidated, especially at low doses, even if its status of endocrine disruptor has been raised [85,86]. We tested 3 low concentrations of carbendazim: 50 nM, 500 nM and 5 μM. It should be emphasized that 5 μM (IC50 for the colchicine-like effect) is 60 times lower than the serum concentration of rats treated with 25 mg of CBZ/kg weight/day for 48 days [87]. We have shown that Carbendazim induces an alteration of the blood-testicular barrier (decrease in Connexin 43 and its functionality) and proves to be an endocrine disruptor (androgen-like effect) at a concentration of 50 nM by regulating on the one hand the estrogen receptor messenger RNAs (Erα and ERß) and secondly by increasing the messenger RNAs of TP1 and TP2, two androgen-dependent genes specific to round spermatids [88]. An additional advantage of our culture systems is that they make it possible to test the effect of combinations of molecules at low concentrations for a period of several weeks.

As an example, we studied the cocktail (carbendazim 50 nM- iprodione 50 nM) because unlike carbendazim, iprodione, a dicarboximide fungicide, is known to have anti-androgenic effects by lowering circulating testosterone levels, inhibiting testicular testosterone production and delaying pubertal development in male rats [89]. Moreover, these two pesticides are present together in the environment following their use alone or in cocktails in marketed products. We have shown by transcriptomic and proteomic studies, in rat seminiferous tubule cultures, that the cocktail triggers effects greater than the sum of the cumulative effects of 50 nM CBZ and 50 nM IPR tested separately [90]. We also compared the effects of the cocktail (carbendazim 50 nM- iprodione 50 nM) and of each of these 2 fungicides at 50 nM in cultures of rat seminiferous tubules, on physiological parameters. Our results show that (i) the presence of iprodione with carbendazim (cocktail) cancels the effect of carbendazim on the increase in androgen-dependent TP1 and TP2 mRNAs and on the decrease in Erα and ERß mRNAs. Nevertheless, carbendazim alone or iprodione alone or the cocktail induces toxicity on spermatogenesis by decreasing the number of round spermatids (the direct precursors of spermatozoa). These results strongly suggest that at the concentrations used, the effects of iprodione and carbendazim do not solely depend on their respective anti-androgen and androgen-like effects but should involve several mechanisms of action [65].

A cocktail of two micropollutants (benzo[a]pyrene and atrazine at 1 µg/L each) was also tested. Atrazine has been one of the widely used agricultural pesticides all over the world. Atrazine concentrations varied from 0.2 to 14.7 μg/L in soil-water samples from La Côte Saint André (Isère, France) [91]. Studied reservoirs in Brazil showed the presence of atrazine at mean levels from 7.0 to 15.0 μg/L [92]. Although its use has been banned in France from 2003, and by the European Union from 2007, atrazine can be persistent in the soil and rivers. Atrazine is now recognized to display endocrine disrupting effects on the male reproductive system of mammals [93-95]. In rodents, in vivo studies have shown that exposure to atrazine delays puberty (Stoker et al., 2000)-[94], decreases testosterone and increases estradiol levels [95], alters meiosis [96], and reduces sperm counts [95,97]. Benzo[a]pyrene can be formed as a result of incomplete combustion from industrial processes, smoking tobacco, charring of grilled foods, and exhaust from diesel and gasoline engines. Inhalation and oral ingestion are two major routes of Benzo[a]pyrene exposure [98]. Values for oral exposure to Benzo[a]pyrene through drinking water range from 0.007 to 0.7 μg/L [99]. In vivo, Benzo[a]pyrene can affect the hormonal balance and gonadal tissue growth and development, induces apoptosis in male germ cells leading to decreased spermatozoa quality and quantity [100-104]. Inhibition of meiotic divisions of rat spermatocytes by Benzo[a]pyrene has been shown in an early in vitro study [104]. The effect of the mixture (benzo[a]pyrene and atrazine at 1 µg/L each) was investigated in our validated BioAlter® model, either during or after the establishment of the blood-testis barrier by using 8- or 20-22-day-old rats. Cultures were performed over a 3-week period. Our results showed that the mixture reduced the number of round spermatids by targeting the middle to late pachytene spermatocytes. These effects were observed in 8- and in 20-22-day-old rat seminiferous tubule cultures. However, the decrease of the number of round spermatids was faster and more marked in the 8-day- than in the 20-22-day-old rat seminiferous tubule cultures. Hence, our study emphasizes the possible influence of the age of an individual on the effect of (a) toxicant(s) on spermatogenesis [32].

We then tested the effects of Glyphosate alone, the most used herbicide in the world today [33]. Indeed, Glyphosate has been mixed with other chemicals to constitute glyphosate-based herbicides such as Roundup® which has been used in agricultural fields and home gardens [105]. Formulated glphosate and its degradation products accumulate in the environment [106]. Glyphosate has been detected in various waters: (i) from 2 to 430 μg/L (11.8 nM to 2.5 μM) in river water and stream water in the USA [107-110] (ii) from 0.1 to 2.5 μg/L i.e. 0.6 nM to 14.8 nM [111,112] in various waters in Europe. Higher levels (up to 165 μg/L i.e. 976 nM) were found in France [113] and Denmark [114]. Human beings may be exposed to glyphosate through food and drinking water [115]. Controversial in vivo studies exist on the effect of glyphosate alone on male reproductive system. Two studies have shown that glyphosate affects spermatogenesis (i) in mice by decreasing the number of spermatozoa and the plasma levels of testosterone [116], (ii) in rabbits resulting in a decline in ejaculate volume and sperm concentration [117]. By contrast, two groups have shown that glyphosate does not affect male reproduction in rat [118,119]. There are only very few in vitro studies on the effect of glyphosate alone on primary cultures of testicular cells. Seralini’s team showed that within 24-48 h glyphosate was essentially toxic to Sertoli cells [120]. The group of Meroni showed that glyphosate could alter the blood-testis barrier at a high concentration (100 μg/mL (588 μM) [121]. Toxic effects on sperm progressive motility but not on sperm DNA integrity were induced in human by glyphosate alone at 360 μg/L (2.1 μM), a concentration that greatly exceed environmental exposures in Europe [122]. We tested the effects of low concentrations of Glyphosate (50 nM, 500 nM, 5 µM or 50 µM) in our model. The observed decrease of Clusterin mRNAs by glyphosate at 50 nM or 500 nM suggested that glyphosate would target the integrity of Sertoli cells. Glyphosate targeted also young spermatocytes and middle to late pachytene spermatocytes resulting in a decrease of the numbers of round spermatids. This study underlines that the effect of a toxicant should be also studied at low doses and during the establishment of the blood-testis barrier [123]. More recently, we evaluated the effects of waters of different origins, hospital effluent waters and/or different drinking waters) on several parameters of the seminiferous epithelium. Concentrated culture medium was diluted with the waters to be tested (final concentrations of the tested waters were between 8 and 80%). The integrity of the blood-testis barrier was assessed by the trans-epithelial electric resistance (TEER). The levels of mRNAs specific of Sertoli cells, of cellular junctions, of each population of germ cells, of androgen receptor, of estrogen receptor α and of aromatase were also studied. We showed that some waters may have an impact on some parameters involved in the process and/or regulation of spermatogenesis, directly at the level of the seminiferous epithelium, including some endpoints related to possible endocrine disrupting effects [124]. Although our model allows reducing the number of rats by 20 to 30 as compared to in vivo studies; in agreement with the 3R rule (Reduction, Refinement and Replacement), it does not provide an answer to the cosmetics industry, which must no longer kill animals for toxicology studies.

In order to replace the use of animals in toxicology studies, we settled the culture of pre-pubertal domestic cat seminiferous tubules (veterinary wastes) in our model. We carried out a comparative study on the effects of 3 testicular toxicants, 1,3-dinitrobenzene at 60 µM, 2-methoxyacetic acid at 2.5 mM and carbendazim at 50 nM or 500 nM in cat or rat seminiferous tubule cultures for a period of 3 weeks. Sertoli cell or each germ cell populations as well as the levels of Sertoli cell or germ cell specific mRNAs were studied. The harmful effects of the 3 toxicants on pre-meiotic, meiotic and post-meiotic cell numbers and on Sertoli or germ cell specific mRNAs were clearly observed in the two species, even if there might be some small differences in the intensity of the effects on some of the studied parameters. Hence, the culture of prepubertal domestic cat seminiferous tubules in our validated BioAlter® model might be a solution to the requirements of the EU cosmetics directive and REACH legislation for male reproductive toxicology studies [125].

Conclusions

It should be underlined that most of the growth factors, cytokines, neurotrophins and steroid hormones produced within the testis, and necessary for spermatogenesis, are widely expressed in the organism and/or necessary for the regulation of other vital functions. For instance, (i) the glial cell-derived neurotrophic factor (GDNF) has been observed in the central nervous system [126] and peripheral organs including the kidneys, lungs, blood, and testes [127-129]; (ii) the receptor tyrosine kinase c-Kit and its ligand Stem Cell Factor (SCF) are involved in haemopoiesis, melanogenesis and spermatogenesis [130,131]. In this line, it has been reported that men with impaired semen parameters have an increased mortality rate suggesting semen quality may provide a fundamental biomarker of overall male health [132,133]. Taken together, these features suggest the possibility of using this in vitro bioassay as a “warning system”.

Acknowledgment

We wish to thank all our colleagues who participated in the realization of our presented studies

References

- Chen X, An H, Ao L, Sun L, Liu W, et al. (2011) The combined toxicity of dibutyl phthalate and benzo(a)pyrene on the reproductive system of male Sprague Dawley rats in vivo. Journal of Hazardous Materials 186: 835-841. [crossref]

- Archibong AE, Ramesh A, Niaz MS, Brooks CM, Roberson SI, et al. (2008) Effects of benzo(a)pyrene on intra-testicular function in F-344 rats. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health 5: 32-40. [crossref]

- Moffat I, Chepelev NL, Labib S, Bourdon-Lacombe J, Kuo B, et al. (2015) Comparison of toxicogenomics and traditional approaches to inform mode of action and points of departure in human health risk assessment of benzo[a]pyrene in drinking water. Critical Reviews in Toxicology 45: 1-43. [crossref]

- Boström CE, Gerde P, Hanberg A, Jernström B, Johansson C, et al. (2002) Cancer risk assessment, indicators, and guidelines for polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons in the ambient air. Environmental Health Perspectives 110: 451-488. [crossref]

- Abarikwu SO, Adesiyan AC, Oyeloja TO, Oyeyemi MO, Farombi EO (2010) Changes in sperm characteristics and induction of oxidative stress in the testis and epididymis of experimental rats by a herbicide, atrazine. Archives of Environmental Contamination and Toxicology 58: 874-882. [crossref]

- Gely-Pernot A, Hao C, Becker E, Stuparevic I, Kervarrec C, et al. (2015) The epigenetic processes of meiosis in male mice are broadly affected by the widely used herbicide atrazine. BMC Genomics 16, 885. of Andrology 14: 584-590. [crossref]

- Victor-Costa AB, Bandeira SMC, Oliveira AG, Mahecha GAB, Oliveira CA (2010) Changes in testicular morphology and steroidogenesis in adult rats exposed to Atrazine. Reproductive Toxicology 29: 323-331. [crossref]

- Stoker TE, Laws SC, Guidici DL, Cooper RL (2000) The effect of atrazine on puberty in male wistar rats: an evaluation in the protocol for the assessment of pubertal development and thyroid function. Toxicological sciences : an official journal of the Society of Toxicology 58: 50-59. [crossref]

- Jin Y, Wang L, Fu Z (2013) Oral exposure to atrazine modulates hormone synthesis and the transcription of steroidogenic genes in male peripubertal mice. General and Comparative Endocrinology 184: 120-127. [crossref]

- Sousa, A.S., Duaví, W.C., Cavalcante, R.M., Milhome, M.A.L., Do Nascimento, R.F., 2016. Estimated Levels of Environmental Contamination and Health Risk Assessment for Herbicides and Insecticides in Surface Water of Ceará, Brazil. Bulletin of Environmental Contamination and Toxicology 96: 90-95. [crossref]

- Tasli S, Patty L, Boetti H, Ravanel P, Vachaud G (1996) Persistence and leaching of atrazine in corn culture in the Experimental Site of La Côte Saint André (Isère, France). Archives of Environmental Contamination and Toxicology 30: 203-212.

- Pisani C, Voisin S, Arafah K, Durand P, Perrard MH, et al. (2016) Ex vivo assessment of testicular toxicity induced by carbendazim and iprodione, alone or in a mixture. Altex 33: 393-413. [crossref]

- Blystone CR, Lambright CS, Furr J, Wilson VS, Gray LE (2007) Iprodione delays male rat pubertal development, reduces serum testosterone levels, and decreases ex vivo testicular testosterone production. Toxicology Letters 174: 74-81. [crossref]

- Carette D, Blondet A, Martin G, Montillet G, Janczarski S (2015) Endocrine Disrupting Effects of Noncytotoxic Doses of Carbendazim on the Pubertal Rat Seminiferous Epithelium: An Ex Vivo Study. Applied In Vitro Toxicology 1: 289-301.

- Rajeswary S, Mathew N, Akbarsha MA, Kalyanasundram M, Kumaran B (2007) Protective effect of vitamin E against carbendazim-induced testicular toxicity-histopathological evidences and reduced residue levels in testis and serum. Archives of Toxicology 81: 813-821. [crossref]

- Lu SY, JW L, Kuo M (2004) Endocrine-disrupting activity in carbendazim-induced reproductive and developmental toxicity in rats. J Toxicol Environ Health 67: 1501-1515. [crossref]

- Hsu YH, Chang CW, Chen MC, Yuan CY, Chen JH, et al. (2011) Carbendazim-induced androgen receptor expression antagonized by flutamide in male rats. Journal of Food and Drug Analysis 19: 418-428.

- Winder BS, Strandgaard CS, Miller MG (2001) The role of GTP binding and microtubule-associated proteins in the inhibition of microtubule assembly by carbendazim. Toxicological Sciences 59: 138-146. [crossref]

- NAKAI M, HESS RA, NETSU J, NASU T (1995) Deformation of the Rat Sertoli Cell by Oral Administration of Carbendazim (Methyl 2‐Benzimidazole Carbamate). Journal of Andrology 16: 410-416. [crossref]

- Correa LM, Miller MG (2001) Microtubule depolymerization in rat seminiferous epithelium is associated with diminished tyrosination of alpha-tubulin. Biology of reproduction 64: 1644-1652. [crossref]

- Nakai M, Toshimori K, Yoshinaga K, Nasu T, Hess RA (1998) Carbendazim-induced abnormal development of the acrosome during early phases of spermiogenesis in the rat testis. Cell and Tissue Research 294: 145-152[crossref]

- Yu G, Guo Q, Xie L, Liu Y, Wang X (2009) Effects of subchronic exposure to carbendazim on spermatogenesis and fertility in male rats. Toxicology and Industrial Health 25: 41-47. [crossref]

- Moffit JS, Bryant BH, Hall SJ, Boekelheide K (2007) Dose-dependent effects of sertoli cell toxicants 2,5-hexanedione, carbendazim, and mono-(2-ethylhexyl) phthalate in adult rat testis. Toxicologic pathology 35: 719-727. [crossref]

- Hess RA, Moore B, Forrer J, Linder RE, Abuel-Atta A (1991) The fungicide benomyl (methyl 1-(butylcarbamoyl)-2-benzimidazolecarbamate) causes testicular dysfunction by inducing the sloughing of germ cells and occlusion of efferent ductules. Fundamental and Applied Toxicology 17: 733-745. [crossref]

- Yu GC, Xie L, Liu Y, zhong, Wang X. fen (2009) Carbendazim affects testicular development and spermatogenic function in rats. Zhonghua nan ke xue = National journal of andrology 15: 505-510. [crossref]

- Carter SD, Hess RA, Laskey JW (1987) The fungicide methyl 2-benzimidazole carbamate causes infertility in male Sprague-Dawley rats. Biology of Reproduction 37: 709-717. [crossref]

- Lim J, Miller MG (1997) The role of the benomyl metabolite carbendazim in benomyl-induced testicular toxicity. Toxicology and Applied Pharmacology 142: 401-410. [crossref]

- Gabrielsen JS, Tanrikut C (2016) Chronic exposures and male fertility: the impacts of environment, diet, and drug use on spermatogenesis. Andrology 4: 648-661. [crossref]

- Van Waeleghe, K, De Clercq N, Vermeulen L, Schoonjans F, Comhaire F (1996) Deterioration of sperm quality in young healthy Belgian men. Human Reproduction 11: 325-329. [crossref]

- Sripada S, Fonseca S, Lee A, Harrild K, Giannaris D, et al. (2007) Trends in semen parameters in the northeast of Scotland. Journal of Andrology 28: 313-319. [crossref]

- Shine R, Peek J, Birdsall M (2008) Declining sperm quality in New Zealand over 20 years. New Zealand Medical Journal 121: 50-56. [crossref]

- Mukhopadhyay D, Varghese AC, Pal M, Banerjee SK, Bhattacharyya AK, et al. (2010) Semen quality and age-specific changes: A study between two decades on 3,729 male partners of couples with normal sperm count and attending an andrology laboratory for infertility-related problems in an Indian city. Fertility and Sterility 93: 2247-2254. [crossref]

- Lackner J, Schatzl G, Waldhör T, Resch K, Kratzik C, et al. (2005) Constant decline in sperm concentration in infertile males in an urban population: Experience over 18 years. Fertility and Sterility 84: 1657-1661. [crossref]

- Carlsen E, Giwercman A, Keiding N, Skakkebaek NE (1992) Evidence for decreasing quality of semen during past 50 years. BMJ (Clinical research ed) 305: 609-613. [crossref]

- Auger J, Kunstmann JM, Czyglik FC., Jouannet, P. (1995) Decline in semen quality among fertile men in paris during the past 20 years. New England Journal of Medicine 332: 281-285. [crossref]

- Adamopoulos DA, Pappa A, Nicopoulou S, Andreou E, Karamertzanis M, et al. (1996) Seminal volume and total sperm number trends in men attending subfertility clinics in the Greater Athens area during the period 1977-1993. Human Reproduction 11: 1936-1941. [crossref]

- Durand P, Martin G, Blondet A, Gilleron J, Carette D, et al. (2017) Effects of low doses of carbendazim or iprodione either separately or in mixture on the pubertal rat seminiferous epithelium: An ex vivo study. Toxicology in Vitro 45: 366-373. [crossref]

- Cotton J, Leroux F, Broudin S, Poirel M, Corman B, et al. (2016) Development and validation of a multiresidue method for the analysis of more than 500 pesticides and drugs in water based on on-line and liquid chromatography coupled to high resolution mass spectrometry. Water Research 104: 20-27. [crossref]

- Goldstein KM, Seyler DE, Durand P, Perrard MH, Baker TK (2016) Use of a rat ex-vivo testis culture method to assess toxicity of select known male reproductive toxicants. Reproductive Toxicology 60: 92-103. [crossref]

- Saradha B, Vaithinathan S, Mathur PP (2009) Lindane induces testicular apoptosis in adult Wistar rats through the involvement of Fas-FasL and mitochondria-dependent pathways. Toxicology 255: 131-139. [crossref]

- Li YJ, Song TB, Cai YY, Zhou JS, Song, et al. (2009) Bisphenol A exposure induces apoptosis and upregulation of fas/fasl and caspase-3 expression in the testes of mice. Toxicological Sciences 108: 427-436. [crossref]

- Li MWM, Mruk DD, Lee WM, Cheng CY (2010) Connexin 43 is critical to maintain the homeostasis of the blood-testis barrier via its effects on tight junction reassembly. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America 107: 17998-18003.

- Akingbemi BT, Sottas CM, Koulova AI, Klinefelter GR, Hardy MP (2004) Inhibition of Testicular Steroidogenesis by the Xenoestrogen Bisphenol a Is Associated with Reduced Pituitary Luteinizing Hormone Secretion and Decreased Steroidogenic Enzyme Gene Expression in Rat Leydig Cells. Endocrinology 145: 592-603. [crossref]

- Wade MG, Kawata A, Williams A, Yauk C (2008) Methoxyacetic acid-induced spermatocyte death is associated with histone hyperacetylation in rats. Biology of Reproduction 78: 822-831. [crossref]

- Chapin RE, Dutton SL, Ross MD, Sumrell BM, Lamb JC (1984) The Effects of Ethylene Glycol Monomethyl Ether on Testicular Histology in F344 Rats. Journal of Andrology 5: 369-380. [crossref]

- Hess RA, Linder RE, Strader LF, Perreault SD (1988) Acute Effects and Long‐Term Sequelae of 1,3‐Dinitrobenzene on Male Reproduction in the Rat II. Quantitative and Qualitative Histopathology of the Testis. Journal of Andrology 9: 327-342. [crossref]

- Elkin ND, Piner JA, Sharpe RM (2010) Toxicant-induced leakage of germ cell-specific proteins from seminiferous tubules in the rat: Relationship to blood-testis barrier integrity and prospects for biomonitoring. Toxicological Sciences 117: 439-448. [crossref]

- Ali S, Steinmetz G, Montillet G, Perrard MH, Loundou A, et al. (2014) Exposure to low-dose bisphenol a impairs meiosis in the rat seminiferous tubule culture model: A physiotoxicogenomic approach. PLoS ONE 9. [crossref]

- Tyl RW, Myers CB, Marr MC, Thomas BF, Keimowitz AR, et al. (2002) Three-generation reproductive toxicity study of dietary bisphenol A in CD Sprague-Dawley rats. Toxicological Sciences 68: 121-146. [crossref]

- Tohei A, Suda S, Taya K, Hashimoto T, Kogo H (2001) Bisphenol a inhibits testicular functions and increases luteinizing hormone secretion in adult male rats. Experimental Biology and Medicine 226: 216-221. [crossref]

- Meeker JD, Ehrlich S, Toth TL, Wright DL, Calafat AM, et al. (2010) Semen quality and sperm DNA damage in relation to urinary bisphenol A among men from an infertility clinic. Reproductive Toxicology 30: 532-539. [crossref]

- Cariati F, D’Uonno N, Borrillo F, Iervolino S, Galdiero G, et al. (2019) bisphenol a: An emerging threat to male fertility. Reproductive Biology and Endocrinology. [crossref]

- Geoffroy-Siraudin C, Perrard MH, Ghalamoun-Slaimi R, Ali S, Chaspoul F, et al. (2012) Ex-vivo assessment of chronic toxicity of low levels of cadmium on testicular meiotic cells. Toxicol Appl Pharmacol 262: 238-246. [crossref]

- Stoica A, Katzenellenbogen BS, Martin MB (2000) Activation of estrogen receptor-α by the heavy metal cadmium. Molecular Endocrinology 14: 545-553. [crossref]

- Martin MB, James Voeller H, Gelmann EP, Jianming L, Stoica EG (2002) Role of cadmium in the regulation of AR gene expression and activity. Endocrinology 143: 263-275. [crossref]

- Yu X, Hong S, Faustman EM (2008) Cadmium-induced activation of stress signaling pathways, disruption of ubiquitin-dependent protein degradation and apoptosis in primary rat sertoli cell-gonocyte cocultures. Toxicological Sciences 104: 385-396. [crossref]

- Chung NPY, Cheng CY (2001) Is cadmium chloride-induced inter-Sertoli tight junction permeability barrier disruption a suitable in vitro model to study the events of junction disassembly during spermatogenesis in the rat testis?. Endocrinology 142: 1878-1888. [crossref]

- Goyer RA, Liu J, Waalkes MP (2004) Cadmium and cancer of prostate and testis. Ln: BioMetals. Pg: 555-558.

- Benoff S, Hauser R, Marmar JL, Hurley IR, Napolitano B, et al. (2009) Cadmium concentrations in blood and seminal plasma: Correlations with sperm number and motility in three male populations (infertility patients, artificial insemination donors, and unselected volunteers). Molecular Medicine 15, 248-262. [crossref]

- Siu ER, Mruk DD, Porto CS, Cheng CY (2009) Cadmium-induced testicular injury. Toxicology and Applied Pharmacology. [crossref]

- Chia SE, Xu B, Ong CN, Tsakok FMH, Lee ST (1994) Effect of cadmium and cigarette smoking on human semen quality. International Journal of Fertility and Menopausal Studies 39: 292-298. [crossref]

- Benoff S, Auborn K, Marmar JL, Hurley IR (2008) Link between low-dose environmentally relevant cadmium exposures and asthenozoospermia in a rat model. Fertility and Sterility. [crossref]

- Järup L, Åkesson A (2009) Current status of cadmium as an environmental health problem. Toxicology and Applied Pharmacology. [crossref]

- Kawanishi S, Inoue S, Sano S (1986) Mechanism of DNA cleavage induced by sodium chromate (VI) in the presence of hydrogen peroxide. Journal of Biological Chemistry 261: 5952-5958. [crossref]

- De Lourdes Pereira M, Santos TM, Garcia E Costa F, Pedrosa De Jesus J (2004) Functional changes of mice Sertoli cells induced by Cr(V). Cell Biology and Toxicology 20: 285-291. [crossref]

- Danadevi K, Rozati R, Reddy PP, Grover P (2003) Semen quality of Indian welders occupationally exposed to nickel and chromium. Reproductive Toxicology 17: 451-456. [crossref]

- Aruldhas MM, Subramanian S, Sekar P, Vengatesh G, Chandrahasan G, et al. (2005) Chronic chromium exposure-induced changes in testicular histoarchitecture are associated with oxidative stress: Study in a non-human primate (Macaca radiata Geoffroy). Human Reproduction 20: 2801-2813. [crossref]

- Perrin J, Lussato D, De Méo M, Durand P, Grillo JM (2007) Evolution of DNA strand-breaks in cultured spermatocytes: The Comet Assay reveals differences in normal and γ-irradiated germ cells. Toxicology in Vitro 21: 81-89. [crossref]

- Benbrook CM (2016) Trends in glyphosate herbicide use in the United States and globally. Environmental Sciences Europe 28: 1-15. [crossref]

- Durand P, Blondet A, Martin G, Carette D, Pointis G, et al. (2020) Effects of a mixture of low doses of atrazine and benzo[a]pyrene on the rat seminiferous epithelium either during or after the establishment of the blood-testis barrier in the rat seminiferous tubule culture model. Toxicology In Vitro 62.

- Sridharan S, Simon L, Meling DD, Cyr DG, Gutstein DE (2007) Proliferation of Adult Sertoli Cells Following Conditional Knockout of the Gap Junctional Protein GJA1 (Connexin 43) in Mice1. Biology of Reproduction 76: 804-812. [crossref]

- Yomogida K, Yagura Y, Tadokoro Y, Nishimune Y (2003) Dramatic expansion of germinal stem cells by ectopically expressed human glial cell line-derived neurotrophic factor in mouse sertoli cells. Biology of Reproduction 69: 1303-1307.

- Tadokoro Y, Yomogida K, Ohta H, Tohda A, Nishimune Y (2002) Homeostatic regulation of germinal stem cell proliferation by the GDNF/FSH pathway. Mechanisms of Development 113: 29-39. [crossref]

- Meng X, Lindahl M, Hyvönen ME, Parvinen M, De Rooij DG, et al. (2000) Regulation of cell fate decision of undifferentiated spermatogonia by GDNF. Science 287: 1489-1493. [crossref]

- Creemers LB, Meng X, Den Ouden K, Van Pelt AMM, Izadyar F, et al. (2002) Transplantation of germ cells from glial cell line-derived neurotrophic factor-overexpressing mice to host testes depleted of endogenous spermatogenesis by fractionated irradiation. Biology of Reproduction 66: 1579-1584.

- Fouchécourt S, Godet M, Sabido O, Durand P (2006) Glial cell-line-derived neurotropic factor and its receptors are expressed by germinal and somatic cells of the rat testis. Journal of Endocrinology 190: 59-71. [crossref]

- Ortega S, Prieto I, Odajima J, Martín A, Dubus P, et al. (2003) Cyclin-dependent kinase 2 is essential for meiosis but not for mitotic cell division in mice. Nature Genetics 35: 25-31. [crossref]

- Godet M, Dametoy A, Mouradian S, Rudkin BB, Durand P (2004) Key Role for Cyclin-Dependent Kinases in the First and Second Meiotic Divisions of Rat Spermatocytes. Biology of Reproduction 70: 1147-1152. [crossref]

- Winterhager E, Pielensticker N, Freyer J, Ghanem A, Schrickel JW, et al. (2007) Replacement of connexin43 by connexin26 in transgenic mice leads to dysfunctional reproductive organs and slowed ventricular conduction in the heart. BMC Developmental Biology 7. [crossref]

- Brehm R, Zeiler M, Rüttinger C, Herde K, Kibschull M, et al. (2007) A sertoli cell-specific knockout of connexin43 prevents initiation of spermatogenesis. American Journal of Pathology 171: 19-31.

- Godet M, Sabido O, Gilleron J, Durand P (2008) Meiotic progression of rat spermatocytes requires mitogen-activated protein kinases of Sertoli cells and close contacts between the germ cells and the Sertoli cells. Developmental Biology 315: 173-188. [crossref]

- Ingman WV, Robertson SA (2007) Transforming growth factor-β1 null mutation causes infertility in male mice associated with testosterone deficiency and sexual dysfunction. Endocrinology 148: 4032-4043. [crossref]

- Yang Z, Wreford NG, De Kretser DM (1990) A quantitative study of spermatogenesis in the developing rat testis. Biology of Reproduction 43: 629-635. [crossref]

- Perrard MH, Vigier M, Damestoy A, Chapat C, Silandre D, et al. (2007) β-nerve growth factor participates in an auto/paracrine pathway of regulation of the meiotic differentiation of rat spermatocytes. Journal of Cellular Physiology 210: 51-62. [crossref]

- Damestoy, A., Perrard, M.H., Vigier, M., Sabido, O., Durand, P., 2005. Transforming growth factor beta-1 decreases the yield of the second meiotic division of rat pachytene spermatocytes in vitro. Reproductive Biology and Endocrinology 3. [crossref]

- Holdcraft RW, Braun RE (2004) Androgen receptor function is required in Sertoli cells for the terminal differentiation of haploid spermatids. Development 131: 459-467. [crossref]

- De Gendt K, Swinnen JV, Saunders PTK, Schoonjans L, Dewerchin M, et al. (2004) A Sertoli cell-selective knockout of the androgen receptor causes spermatogenic arrest in meiosis. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America 101: 1327-1332. [crossref]

- Abel M, Wootton A, Wilkins V, Huhtaniemi I, Knight P, et al. (2000) The Effect of a Null Mutation in the Follicle-Stimulating Hormone Receptor Gene on Mouse Reproduction. Endocrinology 141: 1795-1803. [crossref]

- Vigier M, Weiss M, Perrard MH, Godet M, Durand P (2004) The effects of FSH and of testosterone on the completion of meiosis and the very early steps of spermiogenesis of the rat: An in vitro study. Journal of Molecular Endocrinology 33: 729-742. [crossref]

- Geoffroy-Siraudin C, Perrard MH, Chaspoul F, Lanteaume A, Gallice P, et al. (2010) Validation of a rat seminiferous tubule culture model as a suitable system for studying toxicant impact on meiosis effect of hexavalent chromium. Toxicological Sciences 116: 286-296. [crossref]

- Perrard MH, Hue D, Staub C, Le Vern Y, Kerboeuf D, et al. (2003) Development of the meiotic step in testes of pubertal rats: Comparison between the in vivo situation and under in vitro conditions. Molecular Reproduction and Development 65: 86-95. [crossref]

- Weiss M, Vigier M, Hue D, Perrard-Sapori MH, Marret C, et al. (1997) Pre- and postmeiotic expression of male germ cell-specific genes throughout 2-week cocultures of rat germinal and Sertoli cells. Biology of Reproduction 57: 68-76. [crossref]

- Marret C, Durand P (2000) Culture of porcine spermatogonia: Effects of purification of the germ cells, extracellular matrix and fetal calf serum on their survival and multiplication. Reproduction Nutrition Development 40: 305-319.

- Hue D, Staub C, Perrard-Sapori MH, Weiss M, Nicolle JC, et al. (1998) Meiotic differentiation of germinal cells in three-week cultures of whole cell population from rat seminiferous tubules. Biology of reproduction 59: 379-387. [crossref]

- Perrard MH, Durand P (2009) Redundancy of the effect of TGFβ1 and β-NGF on the second meiotic division of rat spermatocytes. Microscopy Research and Technique 72: 596-602. [crossref]

- Perrard MH, Chassaing E, Montillet G, Sabido O, Durand P (2009) Cytostatic factor proteins are present in male meiotic cells and β-nerve growth factor increases Mos levels in rat late spermatocytes. PLoS ONE 4. [crossref]

- Staub C, Hue D, Nicolle JC, Perrard-Sapori MH, Segretain D (2000) The whole meiotic process can occur in vitro in untransformed rat spermatogenic cells. Experimental Cell Research 260, 85-95. [crossref]

- Gilleron J, Carette D, Durand P, Pointis G, Segretain D (2009) Connexin 43 a potential regulator of cell proliferation and apoptosis within the seminiferous epithelium. International Journal of Biochemistry and Cell Biology 41: 1381-1390. [crossref]

- Carette D, Perrard MH, Prisant N, Gilleron J, Pointis G, et al. (2013) Hexavalent chromium at low concentration alters Sertoli cell barrier and connexin 43 gap junction but not claudin-11 and N-cadherin in the rat seminiferous tubule culture model. Toxicology and Applied Pharmacology 268: 27-36. [crossref]

- Parvinen M (1982) Regulation of the seminiferous epithelium. Endocrine Reviews 3: 404-417. [crossref]

- Kierszenbaum AL (1994) Mammalian spermatogenesis in vivo and in vitro: A partnership of spermatogenic and somatic cell lineages. Endocrine Reviews 15: 116-134. [crossref]

- Jeng HA, Bocca SM (2013) Influence of Exposure to Benzo[a]pyrene on Mice Testicular Germ Cells during Spermatogenesis. Journal of Toxicology 2013: 1-9. [crossref]

- Ramesh A, Inyang F, Lunstra DD, Niaz MS, Kopsombut P (2008) Alteration of fertility endpoints in adult male F-344 rats by subchronic exposure to inhaled benzo(a)pyrene. Experimental and Toxicologic Pathology 60, 269-280. [crossref]

- Georgellis A, Toppari J, Veromaa T, Rydström J, Parvinen M (1990) Inhibition of meiotic divisions of rat spermatocytes in vitro by polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons. Mutation Research – Fundamental and Molecular Mechanisms of Mutagenesis 231: 125-135. [crossref]

- Gillezeau C, Gerwen M van, Shaffer RM, Rana I, Zhang L, et al. (2019) The evidence of human exposure to glyphosate: a review | Environmental Health | Full Text. Environ health 18.

- Battaglin WA, Meyer MT, Kuivila KM, Dietze JE (2014) Glyphosate and its degradation product AMPA occur frequently and widely in U.S. soils, surface water, groundwater, and precipitation. Journal of the American Water Resources Association 50: 275-290.

- Battaglin WA, Rice KC, Focazio MJ, Salmons S, Barry RX (2009) The occurrence of glyphosate, atrazine, and other pesticides in vernal pools and adjacent streams in Washington, DC, Maryland, Iowa, and Wyoming, 2005-2006. Environmental Monitoring and Assessment 155: 281-307. [crossref]

- Battaglin WA, Kolpin DW, Scribner EA, Kuivila KM, Sandstrom MW (2005) Glyphosate, other herbicides, and transformation products in Midwestern streams, 2002. Journal of the American Water Resources Association 41: 323-332.

- Coupe RH, Kalkhoff SJ, Capel PD, Gregoire C (2012) Fate and transport of glyphosate and aminomethylphosphonic acid in surface waters of agricultural basins. Pest Management Science 68: 16-30. [crossref]

- Mahler BJ, Van Metre PC, Burley TE, Loftin KA, Meyer MT, et al. (2017) Similarities and differences in occurrence and temporal fluctuations in glyphosate and atrazine in small Midwestern streams (USA) during the 2013 growing season – News – Elsevier. Sci Total of Environ 579: 149-158. [crossref]

- Poiger T, Buerge IJ, Bächli A, Müller MD, Balmer ME (2017) Occurrence of the herbicide glyphosate and its metabolite AMPA in surface waters in Switzerland determined with on-line solid phase extraction LC-MS/MS. Environmental Science and Pollution Research 24: 1588-1596. [crossref]

- Skark C, Zullei-Seibert N, Schöttler U, Schlett C (1998) The occurrence of glyphosate in surface water. International Journal of Environmental Analytical Chemistry 70: 93-104.

- Villeneuve A, Larroud S, Humbert JF (2011) Herbicide Contamination of Freshwater Ecosystems: Impact on Microbial Communities. Pesticides – Formulations, Effects, Fate.

- Rosenbom AE, Olsen P, Plauborg F, Grant R, Juhler RK, et al. (2015) Pesticide leaching through sandy and loamy fields – Long-term lessons learnt from the Danish pesticide leaching assessment programme. Environmental Pollution 201: 75-90. [crossref]

- Bai SH, Ogbourne SM (2016) Glyphosate: environmental contamination, toxicity and potential risks to human health via food contamination. Environmental Science and Pollution Research 23: 18988-19001. [crossref]

- Pham TH, Derian L, Kervarrec C, Kernanec PY, Jegou B, et al. (2019) Perinatal exposure to glyphosate and a glyphosate-based herbicide affect spermatogenesis in mice. Toxicological Sciences 169: 260-271. [crossref]

- Yousef MI, Ibrahim HZ, Helmi S, Salem MH, Seehy MA, et al. (1995) Toxic effects of carbofuran and glyphosate on semen characteristics in rabbits. Journal of Environmental Science and Health Part B 30: 513-534. [crossref]

- Dai P, Hu P, Tang J, Li Y, Li C (2016) Effect of glyphosate on reproductive organs in male rat. Acta Histochemica 118: 519-526. [crossref]

- Johansson HKL, Schwartz CL, Nielsen LN, Boberg J, Vinggaard AM, et al. (2018) Exposure to a glyphosate-based herbicide formulation, but not glyphosate alone, has only minor effects on adult rat testis. Reproductive Toxicology 82: 25-31. [crossref]

- Clair É, Mesnage R, Travert C, Séralini GÉ (2012) A glyphosate-based herbicide induces necrosis and apoptosis in mature rat testicular cells in vitro, and testosterone decrease at lower levels. Toxicology in Vitro 26: 269-279. [crossref]

- Gorga A, Rindone GM, Centola CL, Sobarzo C, Pellizzari EH, et al. (2020) In vitro effects of glyphosate and Roundup on Sertoli cell physiology. Toxicology in Vitro 62. [crossref]

- Anifandis G, Katsanaki K, Lagodonti G, Messini C, Simopoulou, M., et al. (2018) The effect of glyphosate on human sperm motility and sperm DNA fragmentation. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health 15. [crossref]

- Blondet A, Martin G, Durand P, Perrrard MH (2022b) Low concentrations of glyphosate alone affect the pubertal male rat meiotic step: An in vitro study. Toxicology in Vitro 79. [crossref]

- Blondet A, Martin G, Paulic L, Perrard MH, Durand P (2021) An in vitro bioassay to assess the potential global toxicity of waters on spermatogenesis: a pilot study. Environmental Science and Pollution Research 28: 26606-26616. [crossref]

- Blondet A, Martin G, Durand P, Perrard MH (2022a) A comparative study of the effects of 3 testicular toxicants in cultures of seminiferous tubules of rats or of domestic cats (veterinary waste): an alternative method for reprotoxicology. Toxicology in Vitro. In press.

- Du Y, Dreyfus CF (2002) Oligodendrocytes as providers of growth factors. Journal of Neuroscience Research 68: 647-654. [crossref]

- Suter-Crazzolara C, Unsicker K (1994) GDNF is expressed in two forms in many tissues outside the CNS. NeuroReport 5: 2486-2488. [crossref]

- Suvanto P, Hiltunen JO, Arumäe U, Moshnyakov M, Sariola H, et al. (1996) Localization of glial cell line-derived neurotrophic factor (GDNF) mRNA in embryonic rat by in situ hybridization. European Journal of Neuroscience 8: 816-822. [crossref]

- Trupp M, Rydén M, Jörnvall H, Funakoshi H, Timmusk T, et al. (1995) Peripheral expression and biological activities of GDNF, a new neurotrophic factor for avian and mammalian peripheral neurons. Journal of Cell Biology 130: 137-148. [crossref]

- Ashman LK (1999) The biology of stem cell factor and its receptor C-kit. International Journal of Biochemistry and Cell Biology 31: 1037-1051. [crossref]

- Rossi P, Sette C, Dolci S, Geremia R (2000) Role of c-kit in mammalian spermatogenesis. Journal of Endocrinological Investigation 23: 609-615. [crossref]

- Eisenberg ML, Li S, Behr B, Cullen MR, Galusha D, et al. (2014) Semen quality, infertility and mortality in the USA. Human Reproduction 29: 1567-1574. [crossref]

- Jensen TK, Jacobsen R, Christensen K, Nielsen NC, Bostofte E (2009) Good semen quality and life expectancy: A cohort study of 43,277 men. American Journal of Epidemiology 170: 559-565. [crossref]