DOI: 10.31038/NRFSJ.2023621

Abstract

200 respondents, half from the United States and half from the United Kingdom each evaluated unique sets of 24 vignettes about their attitudes towards ultra processed foods. The vignettes were constructed from 16 different elements (messages), with 2-4 messages from the 16 incorporated into a vignette, specified by an underlying experimental design. The 16 elements were generated through AI (artificial intelligence, Idea Coach), dealing with different aspects of ultra processed food, messages meaningful to a consumer. Each respondent rated her or his specific, unique set of 24 vignettes using a two-dimensional, five-point scale, one dimension of the scale dealing with want to quit eating vs. do not want to quit eating the food (key dependent variable), and the second dimension of the scale dealing with the belief versus non-belief that the food was addictive. No strong messages emerged for the total panel, or by country. A few strong messages emerged by gender and age. Strong messages emerged when the 200 respondents were clustered by the 200 patterns of coefficients, one pattern per respondent. The 200 patterns emerged from the respondent-level equation relating the 16 elements to rating of ‘want to stop eating the food.’ After performing k-means clustering on the patterns, three mind-sets emerged that were: Mind Set 1 of 3 – Focus on the negative effects, especially eating patterns and effects on the body; Mind Set 2 of 3 – Focus on scare tactics, using well-known issues. Mind Set 3 of 3 – Focus on food as giving pleasure and then causing addiction. The approach shows that topics like social attitudes can harness the power of using AI to generate ideas in a directed fashion through question and answer (Idea Coach), followed by empirical testing of the ideas with real people, and final summarizations of the results by the researcher aided once again by AI.

Introduction – The Evolution of Food Design and Creation

The world of food product development as a serious effort is approximately 100 years old, although there are no seminal events that can really be said to usher in this period. Historians might look at the development of canning by Nicholas Appert as a key event in food preservation, one demarcated by the creation of a specific piece of technology. When we look for such a key event for the commercial design and development of food products, we might look at the origin of various historically well know processed foods, such as condiments, cereals, and the like. Those, however, are simply single events, commercial ones, which show the gradual evolution of processed foods.

A better marker of processed foods may come from the efforts by companies to determine the perceptions and preferences of their customers, subjective aspects which could guide the creation and manipulation of foods. With this revised viewpoint regarding processed food, it would be reasonable to point to the 1930’s ad 1940’s, to the seminal work of the Arthur D. Little Inc., group in Acorn Park, MA. In a westerly part of Cambridge, and in so doing to the work of Stanley Cairncross, Loren B Sjostrom and others [1]. Their creation of the Flavor Profile system reflects the effort to guide product development by creating foods which possessed specific and presumably desired sensory characteristics. Indeed, one of their papers was proudly titled ‘What makes flavor leadership? [2].

The history of food product design and creation, moving from foods available to foodstuff created by science and technology, moved into the world of statistics, design, and experiments. Early work on statistics by Joan Gordon called ‘response surface design’ [3] was expanded upon by author Howard Moskowitz to create many products in the 1970’s through the 1990’s, such as variations of Prego [4], Tropicana Grovestand Orange Juice [5], and even optimized mixtures of sweeteners incorporating Aspartame [6]. In those early experiments with mixtures of ingredients, the ingredients were primarily complete foods, such as amount of tomato sauce or size of tomato chunks for the case of Prego (and a year before, for Ragu as well, but with different ingredients). When it was time to optimize Vlasic pickles, to produce the lie of 1-4, culminating in Zesty, to become a best-selling pickle in the United States, the ingredients were again natural condiments, such as salt, acid, pepper. A finally, for Tropicana Grovestand Orange Juice, the variables were amounts of different types of orange juice amount of natural pulp, etc. The common them here was that in the period of 1970’s to 1990’s, the notion of ‘processed food’ turned out to be the combination of normal ingredients. The driving force was the demand by the president of the company to create a good testing, normal product [7].

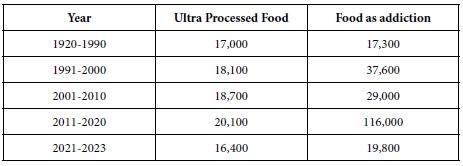

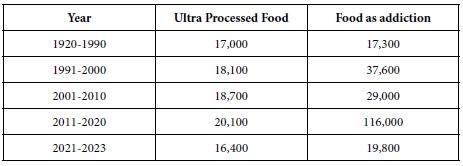

In those halcyon years, 1970’s to around 2020, the issue of a ‘processed’ food was a non-event. There may have been some issues, but the number of publications devoted to the topic of ‘ultra-processed food’ was stable. Table 1 shows the number of hits for the term ‘ultra processed food’, and then ‘food as addiction’. Many of the papers emerging from this focus deal with the linkage of ultra-processed foods to emerging health issues world-wide, such as obesity [8-12]. Other papers simply focus on responses to ultra processed foods as part of the evolution of the way people eat, including eating as an addiction, or at least some foods as addicting [13]. Beyond the emotionally tinged word ‘addicting’ lies the full gamut of different ways that people eat, the nature of the knowledge of food wants and desires, as well as the desire to use such information to educate the consuming public, which comprises just about everyone [14,15].

It is not the focus of this paper to delve into the reasons for the emergence of ultra processed food, other than to remark on the ‘processization’ of product design and development. From the author’s experiment since 1975, one change has been that the call for new products is not the job of the person at the top,. But rather of middle managers, often MBA’s, and often working by the numbers Whereas in the 1970s and 1980’s the senior management would be at meetings, and the product developers and consumer researchers were encouraged to explore ways of getting ‘better tasting food to the consumer’, the more recent experiences suggest ‘management by objectives.’ The goal is to work with ingredient and flavor suppliers to get cost=effective ingredients that can be blended into one’s product, to achieve an adequate score with consumers as reported by market researchers who hand off the task to approved suppliers, and the measurement of success. There is precious little profound knowledge about how products are formulated to appeal to different tastes, and a lack of understanding of the precise messaging which entice the consumer.

The unhappy outcome of the former situation, evolving from producing products tasting good at a cutting to blending according to nutrition, stability, has end up discarding the exciting times when products are tasted, and when the product developers are pushed to make may products, and test them to find out just what wins. The process has been routinized, less exploratory, far less able to break out of the bounds, and simply hamstrung to produce a modest change so that a brand manager can produce another product quickly to add to the resume, planning for the next job. And there is a decrease in the systematic knowledge, information that could be put into a ‘book’ or computer program, to simulate new products.

Delving into the Mind of the Person

This paper moves away from the issues of ultra processed foods from the point of view of experts discussing its ramifications. Rather, this paper focuses on the mind of a typical individua, when presented with the various messages about ultra processed food. How do people respond to these messages. The objective is to move from the surface response that would be obtained in a simple survey, and instead dive below that surface to find out how people truly feel when they are unable to ‘game’ the survey by choosing the politically correct response, or at least the response that they perceive is the ‘right one.’

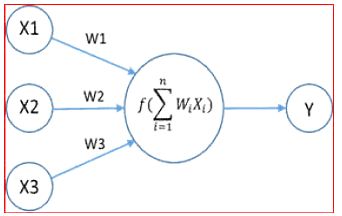

The approach used is known as Mind Genomics, an emerging branch of experimental psychology with the objective of measuring the subjective impact of messages presented to the respondent, and by so doing metricize thought [16-19].

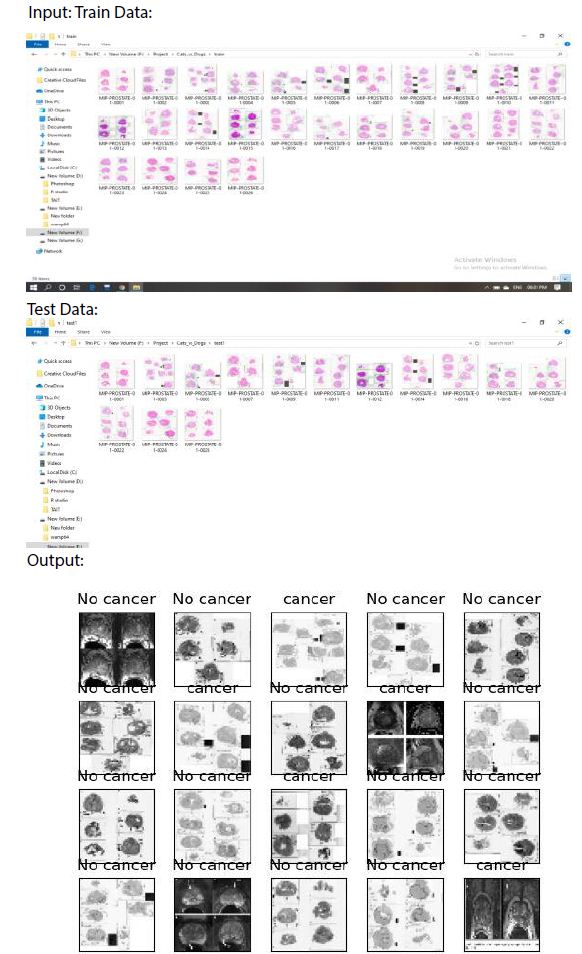

The process of Mind Genomics is simple, and direct. The respondent is presented with structured combinations of elements, viz., messages, in short, easy to read vignettes (combinations) comprising 2-4 messages for each vignette. The combinations are created by an underlying experimental design, a plan, which specifies the components of each vignette. For this particular study, each respondent will evaluate a set of 24 vignettes, with each vignette different from every other vignette. IN the end, the respondents will each evaluate unique sets of vignettes. From the pattern of their ratings, it will be straightforward to estimate how each element or message drove the response for that individual respondent. Mind Genomics as a science enables the researcher to explore a topic, as long as the topic can be dimensionalized into different elements, or phrases.

Mind Genomics emerged from the confluence of three disciplines. The first discipline is psychophysics, the oldest branch of experiential psychology, whose focus is on relating the stimulus properties to how they are perceived. The second discipline is statistics, and more specifically experimental design, with the focus of laying out the proper combinations of stimuli to create the aforementioned ‘vignettes.’ The correct layout enables the researcher to use statistics such as OLS (ordinary least squares) regression and cluster analysis to identify meaningful patterns. The third discipline is consumer research, which focuses on the world of the everyday. The Mind Genomics effort is, primarily, to understand the mind of the person facing everyday situations.

A Worked Mind Genomics Cartography about Ultra-processed Foods across Two Countries

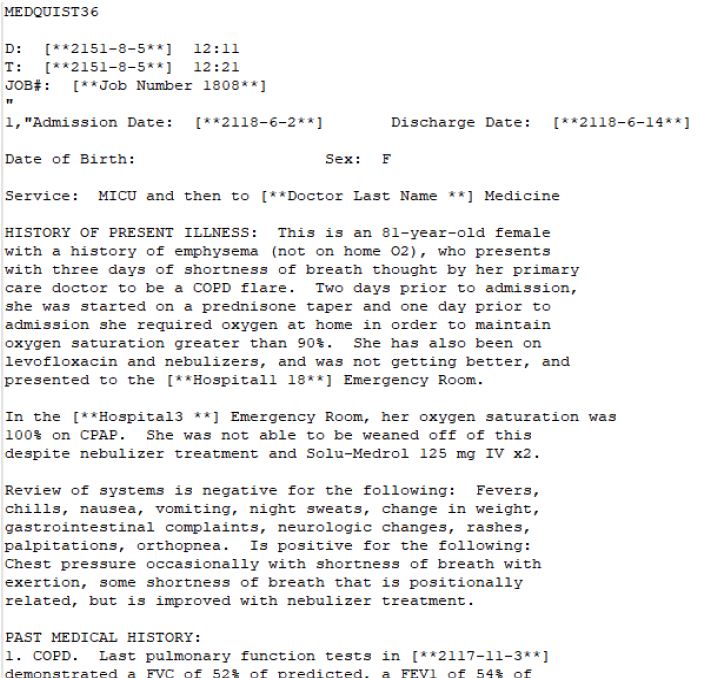

The paper presented here grew out of the interest of a broadcasting company in the topic of ultra processed foods. During the middle of 2023 the topic of ultra processed foods and its health and addiction ramifications took on a sense of increasing public focus. The reasons for the development of the interest are not important. In contrast, what emerged as being important was the reaction of ordinary people, not necessarily connected with the world of health and food, to the types of language that was used when dealing with aspects of ultra processed foods.

The Mind Genomics process works through a templated system (wwwBimiLeap.com). The objective is to enable anyone in the world to use research to ask questions (initial learning) and then to answer these questions through an experiment (experiential learning). The templated system permits the researcher to ‘fill in the empty spaces’ with information, this information comprising questions pertaining to a topic, and then answers to those questions. The actual research, described in more detail below, combines the answers (messages) about a topic, presents these combinations to respondents, obtains ratings, and then deconstructs the ratings of the vignette into the contributions of the individual elements. In that way, the manner in which a person ‘looks at the topic’ often becomes obvious, as will be seen below.

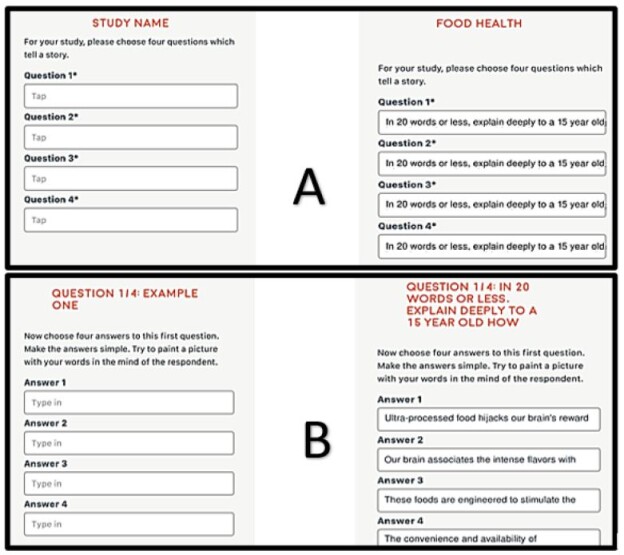

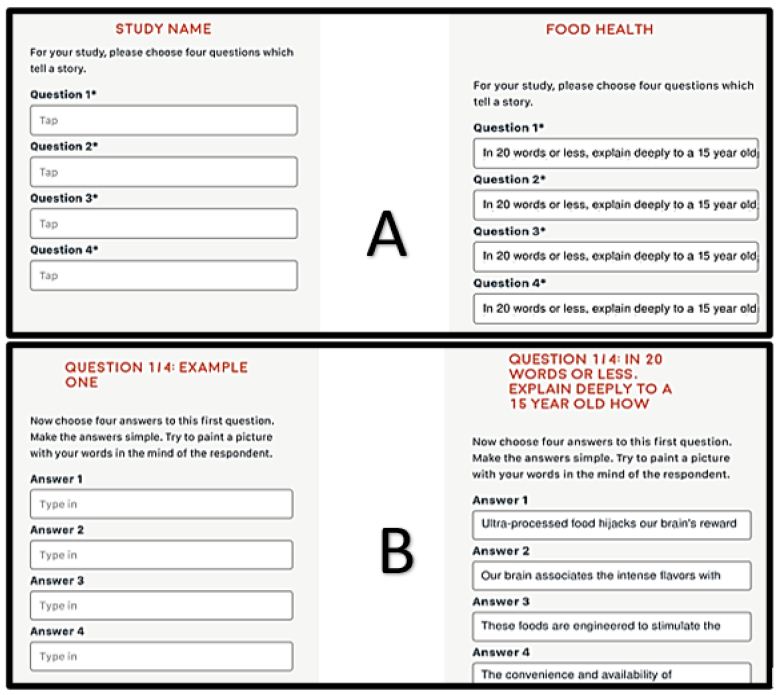

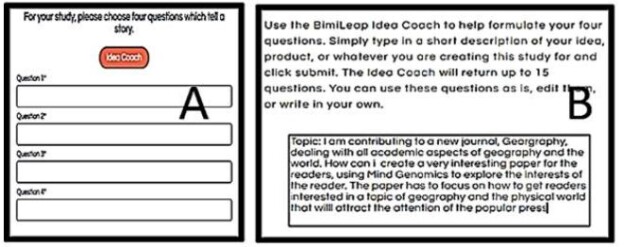

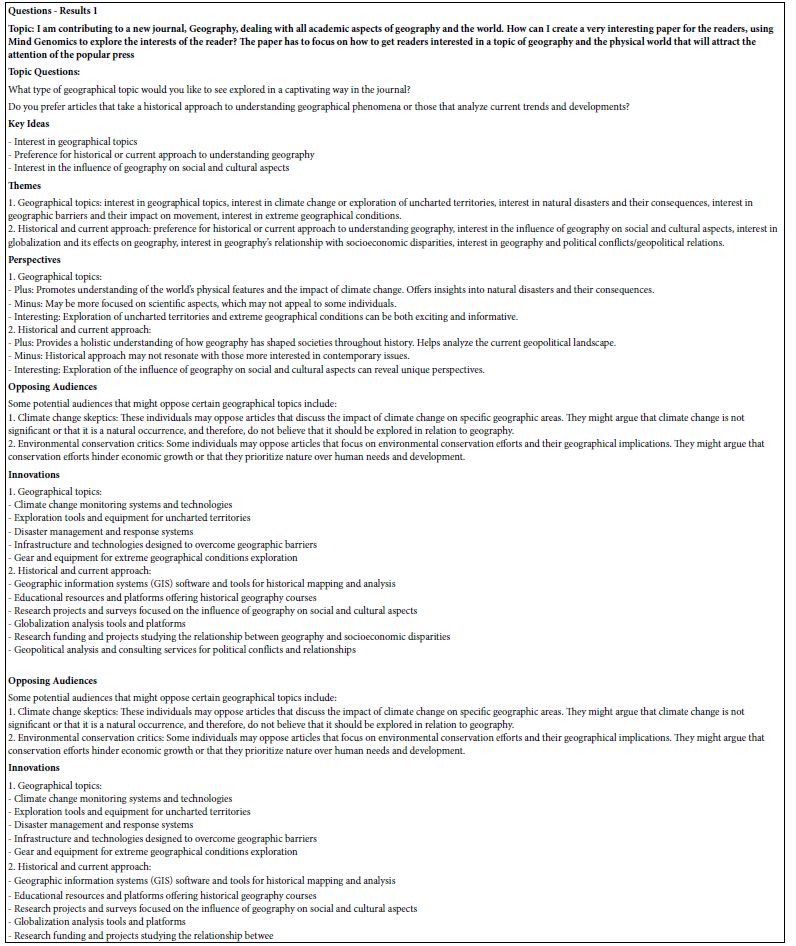

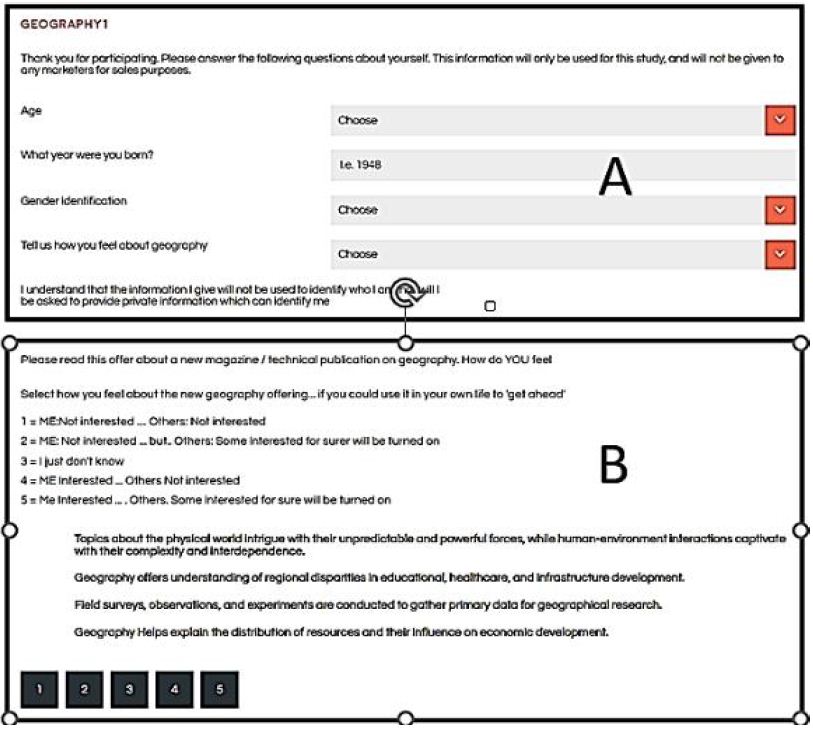

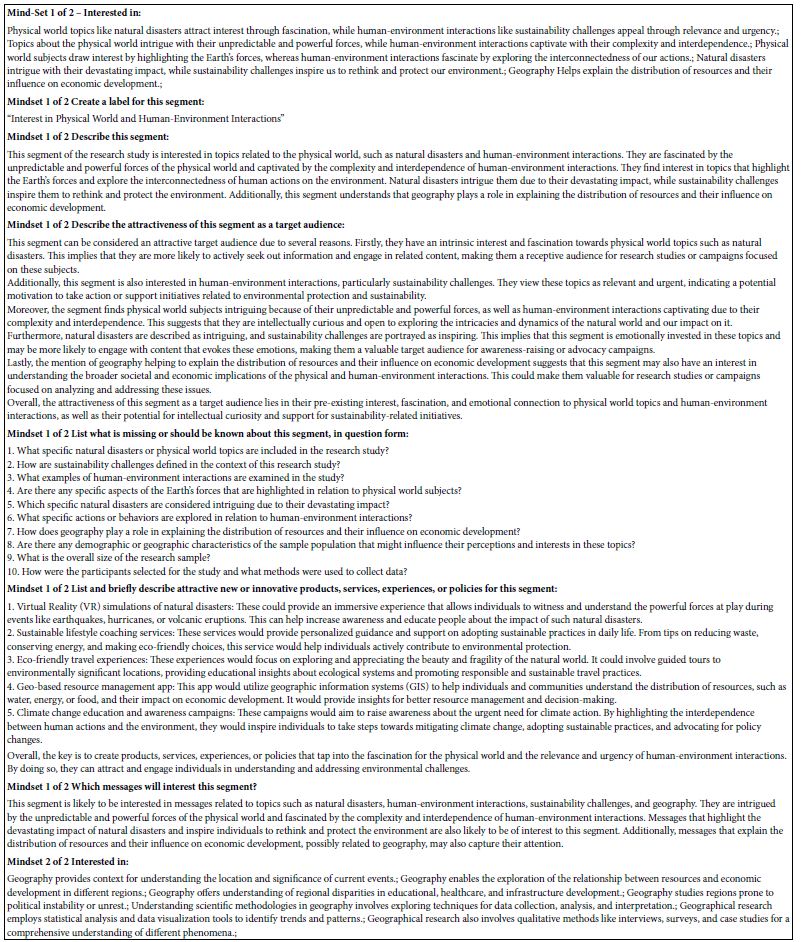

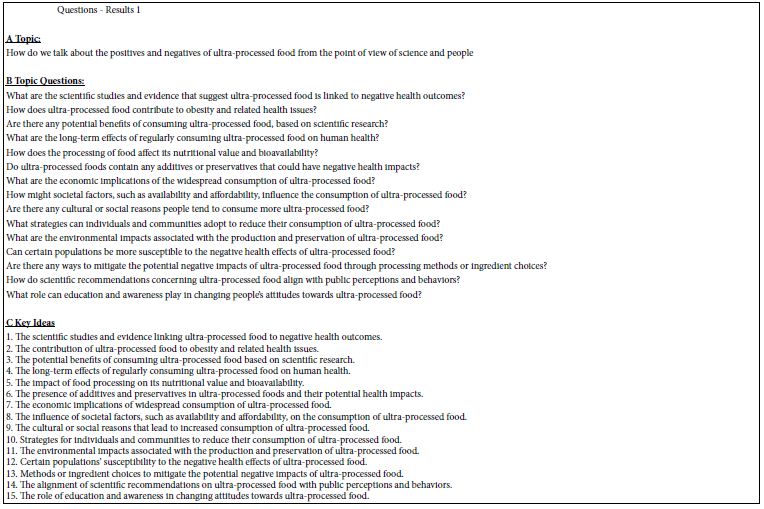

The first step is to consider what faces the researcher at the start of the effort. Panel A of Figure 1 shows the request for four questions pertaining to a topic, questions which in loose terms ‘tell a story’, or in more practical terms are simply different aspects or facets of a single topic. The left part of the panel shows the request for four questions, the right part of the panel shows four questions filled in, or more correctly the first few words of the four questions. Panel B below shows the same type of template, this time for four answers to the first question, the left being blank, the right to be completed by the researcher.

Figure 1: Panel A (right) shows the template for the four questions and the first parts of the question as filled in (left). Panel B shows the same thing for the first question, requesting four answers to that first question.

During the 15 years that the BimiLeap system was being developed, the issue of not knowing much about a topic continued to arise, an issue occasionally resulting in some hard and deep thinking, but an issue more often leading to frustration, anger, and abandonment of the Mind Genomics approach entirely. The reality is that the education system around the world is good at teaching people to answer direct questions, questions with specific types of information or opinion, but not good at teaching people to think in a creative manner. It is the inability to think in a constructive manner which continued to emerge as the ‘pain point’ of the effort.

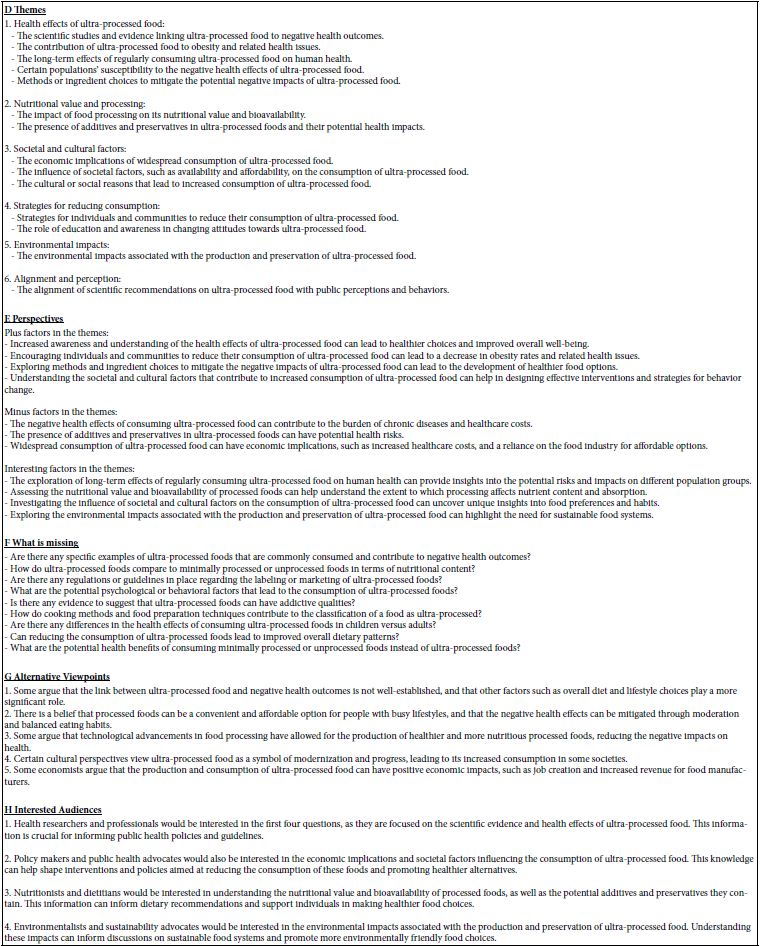

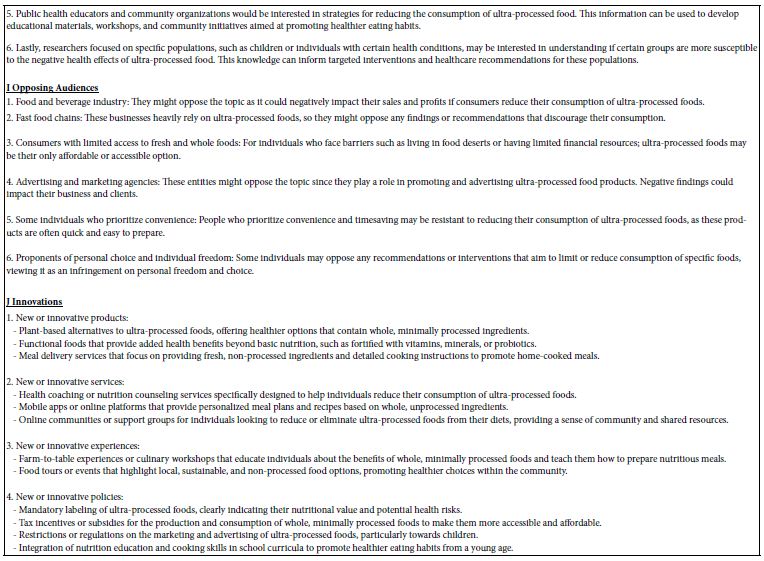

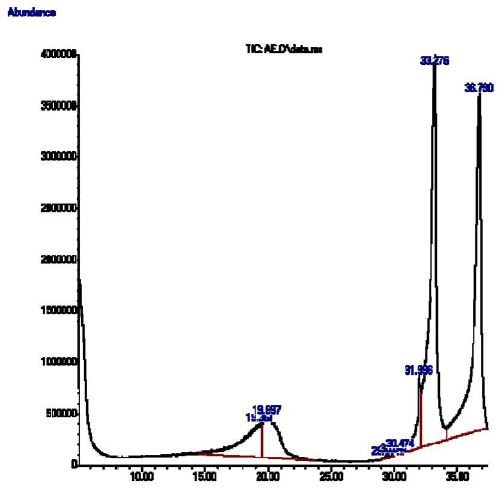

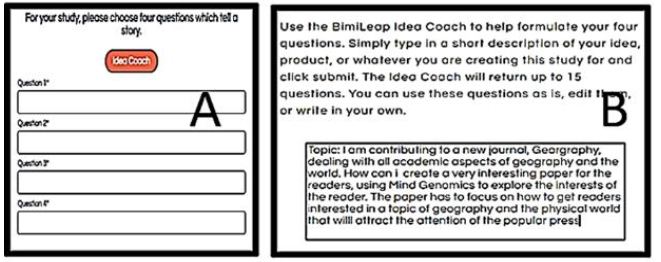

Rather than looking at the various papers and press releases dealing with ultra-processed foods, the authors began the experiment by using artificial intelligence to explore different questions that one could ask about ultra processed foods. The tool used was the Idea Coach feature of Mind Genomics (www.BimiLeap.com). The Idea Coach enables the researcher to specify a topic as a paragraph, and then return with sets of 15 questions, from which the researcher can choose up to four to research in the subsequent Mind Genomics experiment. The Idea Coach provides the researcher with the ability to select one or several questions to explore and is programmed to produce sets of 15 questions on the topic when required. The questions emerging can be edited, as can the topic paragraph used for the questions. In the end, however, the researcher generates four questions through the use of Idea Coach. These sets of questions are later returned to the researcher in the ‘Idea Book’. The Idea Book features one page for each set of 15 questions generated, along with AI summarization of the different aspects of the 15 questions, such as themes, innovations, etc., providing a unique, focused book on the topic.

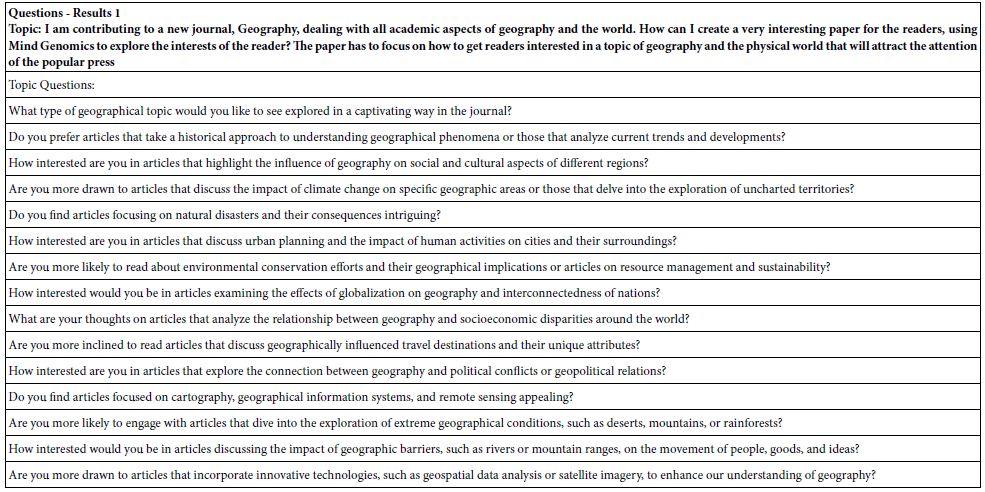

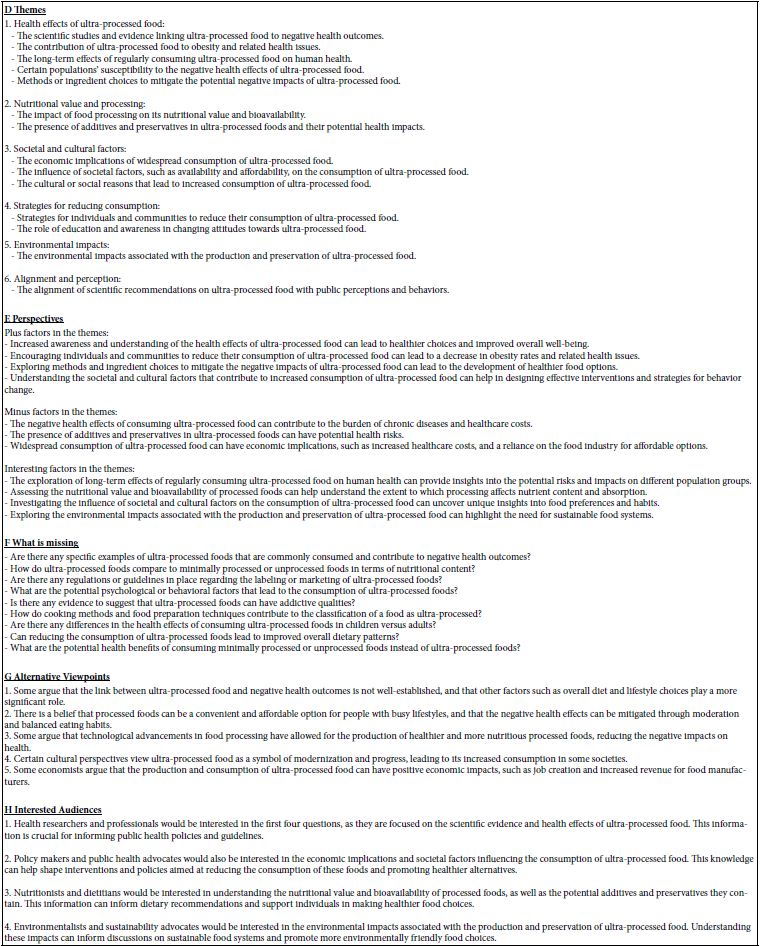

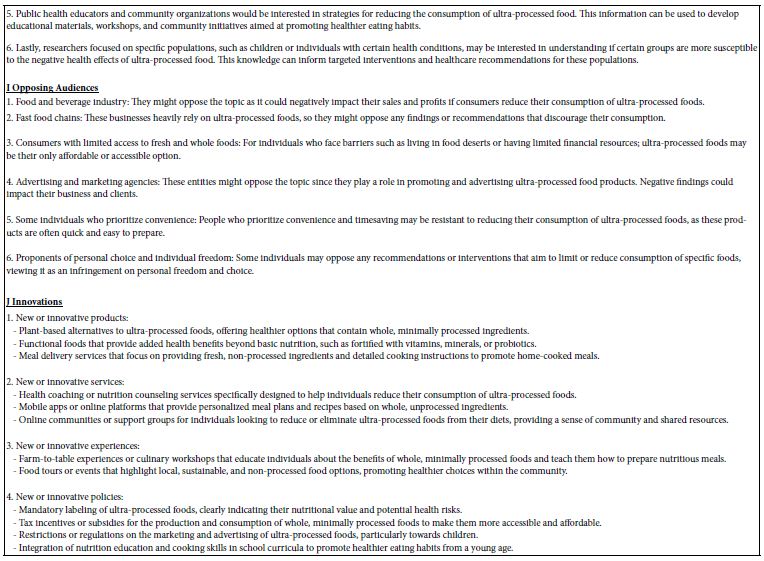

Table 1 presents the first set of questions emerging from the topic paragraph. The table provides both the actual questions emerging from the AI, as well as a summarization of the tables using pre-set queries presented to the AI in Idea Coach. The queries summarize the patterns resident within the set of questions.

Table 1: Google Scholar ‘hits’ for ‘ultra processed food’ and for ‘food as addiction’, respectively

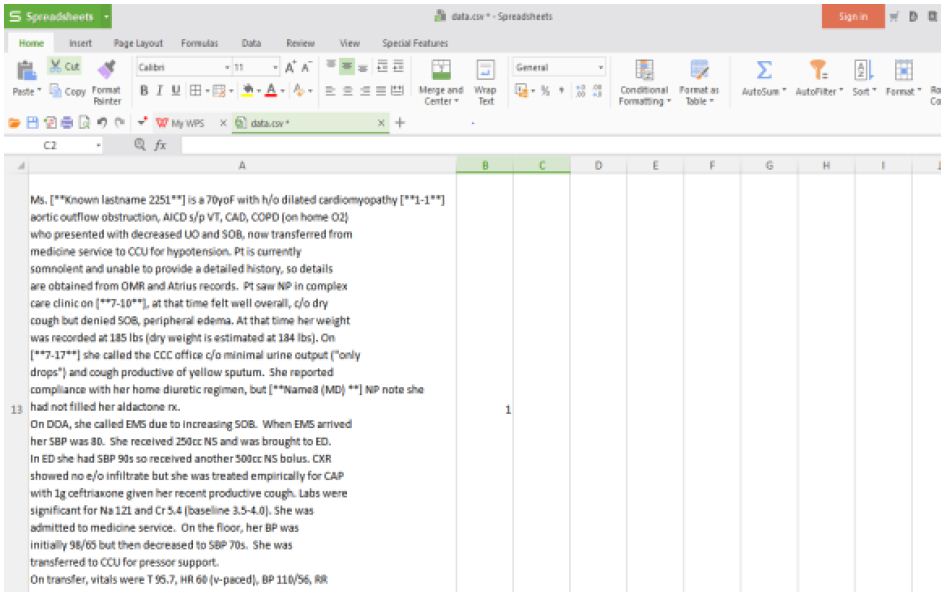

Executing the Study

The actual study itself comprises four questions, and for each question, four answers. The underlying experimental design generates the structure of the individual vignettes, with each respondent evaluating precisely 24 vignettes. The vignettes are set up so that the 16 elements are presented in a way which defeats attempts to discover the pattern. Furthermore, and using as a metaphor the MRI (magnetic resonance imaging), the 24 vignettes for each person are different from each other, permuted so that the mathematical structure remains the same, but the specific combinations differ. Thus, the experimental design covers a great deal of the so-called design space, allowing the researcher the liberty of exploring the unknown, rather than confirming the correctness or incorrectness of a guess based on prior knowledge. As noted above, the researcher need not know anything. The research itself covers a great deal of the design space, not just 24 of the many hundreds of possible combinations. The approach is called a permuted design [20].

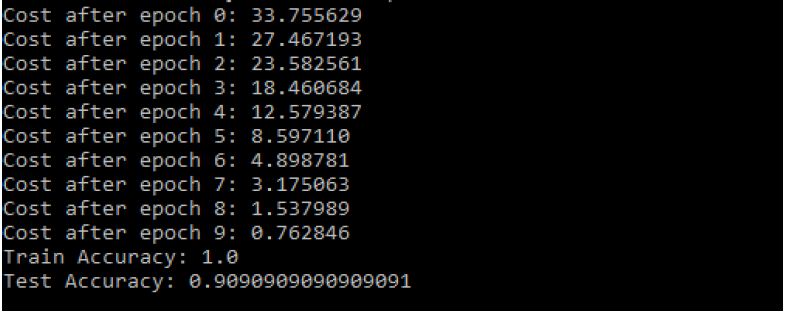

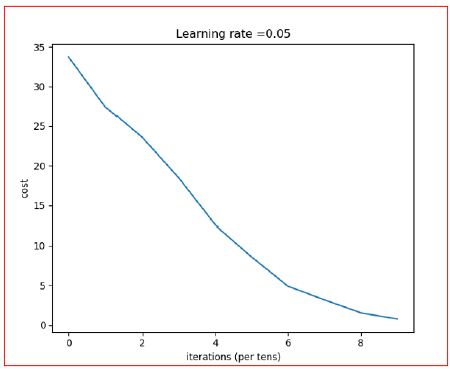

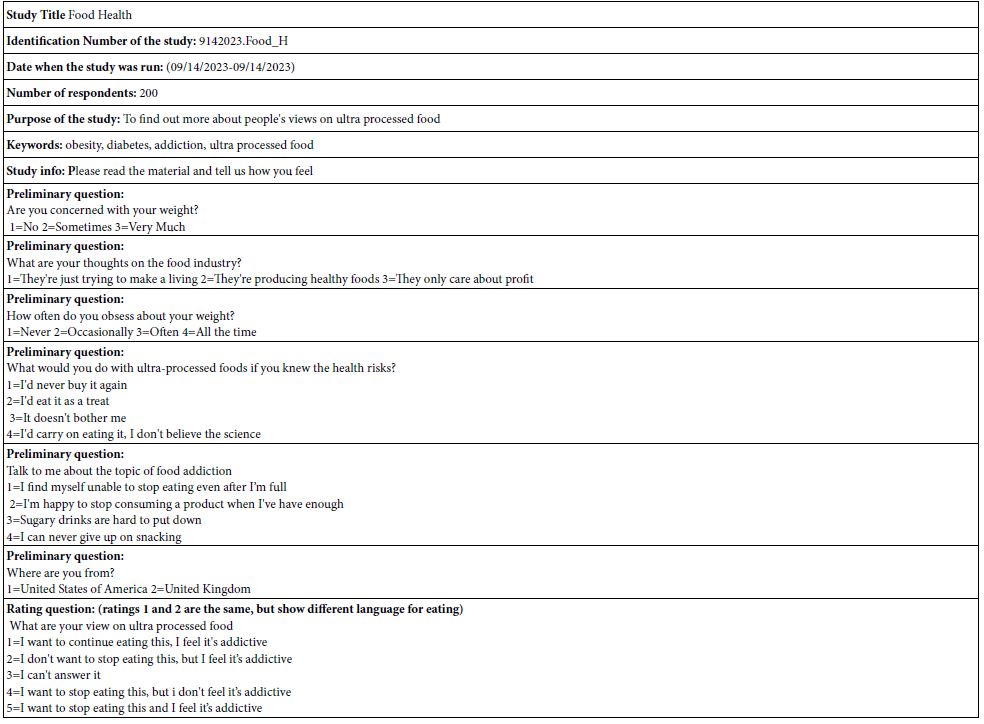

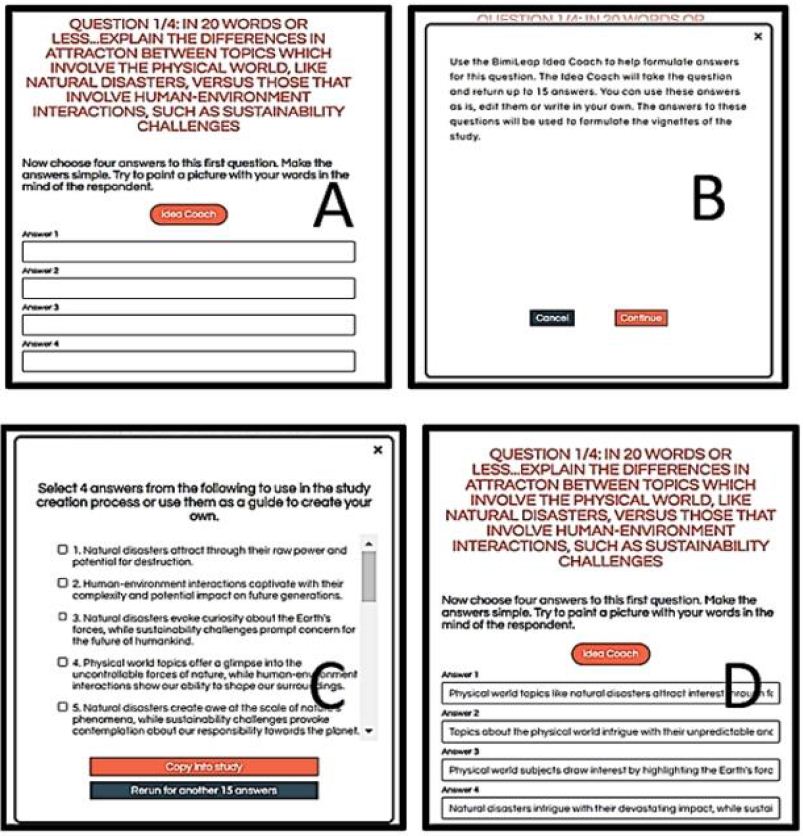

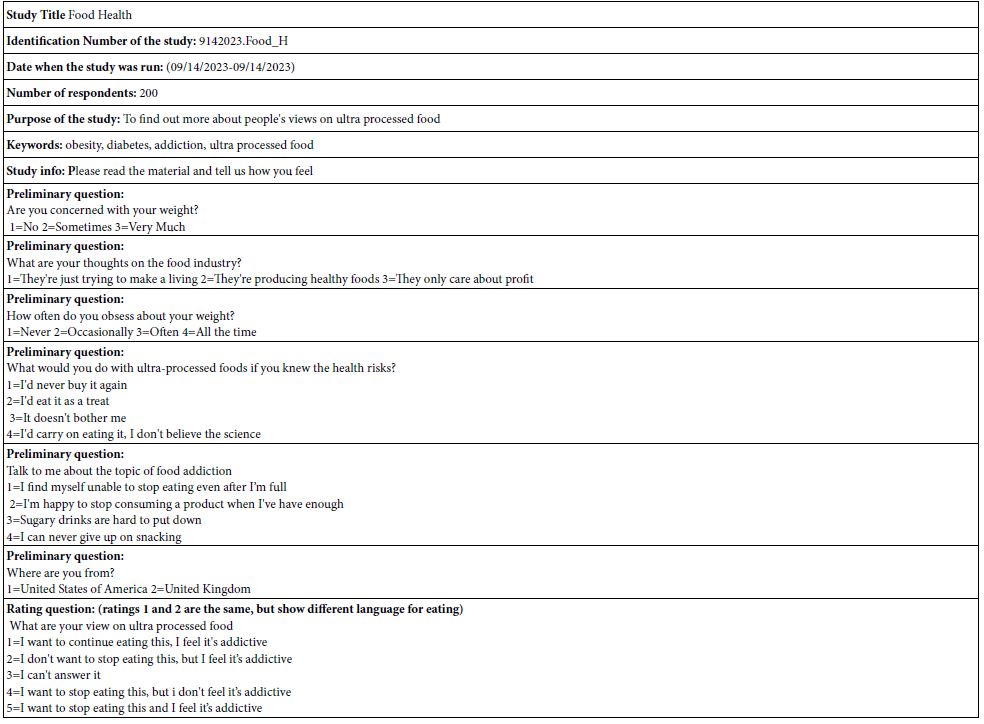

The particulars of the study are shown in Table 2. Each respondent, whether in the US or the UK, was invited to participate by Luc.Id, an online panel provider. The respondent was oriented in the study, then completed a set of self-profiling questions, including age, gender, and then statements about food. AT the bottom of Table 2 is shown the five rating questions. The focus here is on the combination of ratin5 5 and 4. That combination (R54) shows the ratings pertaining to the respondent wanting to stop eating the food, bad upon the message in the vignette.

Table 2: Questions emerging from the topic paragraph, along with additional commentary and interpretation of these questions by AI embedded in the Idea Coach. Each repetition of the Idea Coach generates a separate page of questions and AI summarization.

The actual study requires approximately 3-5 minutes, from the orientation to the completion. Most respondents who are not professionals simply read the instructions, and respond to the vignettes, using the scale. Exit interviews over the years of doing Mind Genomics studies reveal that the vast majority of conventional respondents don’t feel that they did the study correctly, that they guessed, that they stopped ‘caring’ and simply rated based upon their first impression. Nonetheless, as will emerge below the data are consistent. Despite the consistency, most professionals doing the same study find that they are irritated, they cannot ‘discern’ the pattern, they feel that they are simply guessing, and report feeling frustrated and irritated. Many quit in irritation, some in simple anger. This is the same reality which ended up producing the Idea Coach embodiment of AI. For respondents, the irritation simply means that there is more hope for data from regular people than from professionals who may pride themselves n their intellectual acumen, even in the case of simple topics such as ultra processed foods.

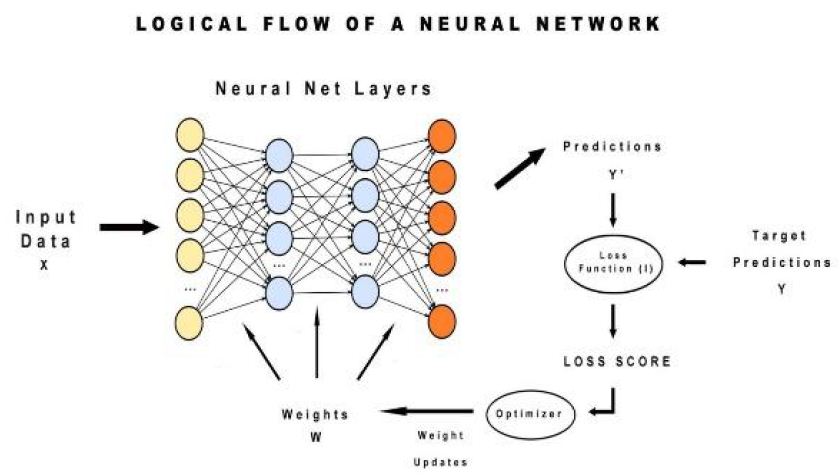

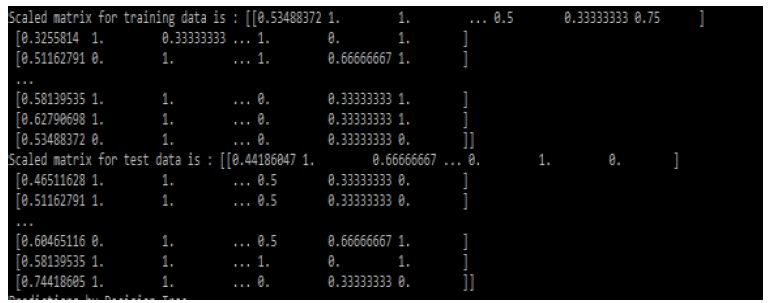

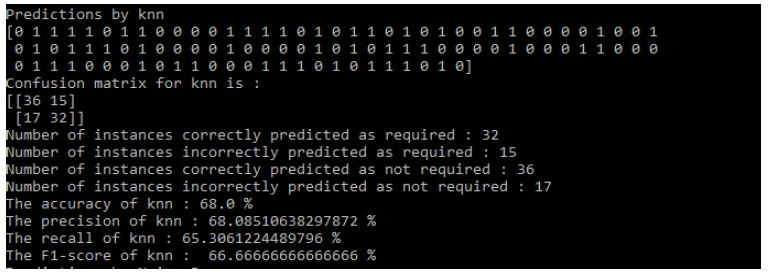

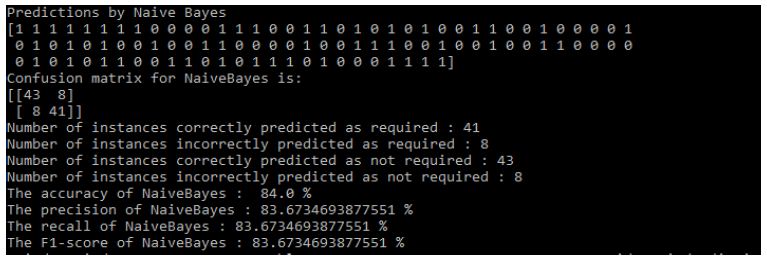

Analysis by Data Transformation, followed by OLS (Ordinary Least Squares Regression)

The analysis of these data begin by first transforming the five-point rating (bottom of Table 2) into a binary scale, based upon the rule that a rating of 5 and 4 are transformed to 100, and a rating of 1,2 or 3 are transformed to 0. The new binary variable, R54 shows us the desire to stop eating the food suggested by the text in the vignette. The respondent was presented with different vignettes. When the rating was 5 or 4, the vignette was given the aforementioned new value ‘100’, to which was added a vanishingly small random number (< 10-5). The purpose of the random number is purely prophylactic, viz., to ensure that there would be some level of variation in this newly created variable, R54.

For the initial analysis of the total panel, a second and new binary transformed variable was created, R52. This corresponds to the perception that what is read in the vignette describes something addictive. R52 takes on the value 100 when the rating is 5 or 2 and takes on the value 0 when the rating is 1, 3, or 4. Again, a vanishingly small random number is added to the newly created binary variable.

After the creation of the two binary variables, R52 and R52, respectively, it is straightforward to relate the presence/absence of the 16 elements to the newly transformed binary variables. The analysis is known as OLS (ordinary least squares) ‘dummy’ regression [21]. The independent variables are ‘dummy variables’, being either present or absent in a vignette. Neither the regression analysis nor we have any other information incorporated in this variable, such as magnitude. The independent variable, or rather the 16 independent variables, one per element, are simply present or absent in each of the 4800 vignettes generated by the 200 respondents who evaluated 24 unique vignettes each.

The equation is written as Binary Dependent Variable = k1(A1) + k2(A2) … k16(A16)

The foregoing equations summarize the relation between the messages or elements under the researcher’s control and the respondents rating, after that rating has been transformed to the binary scale. The coefficient shows how many points out of 100 can be traced to the appearance of the element in the vignette. Again, it is impossible for most if not all people to know since each person tests a unique set of 24 vignettes and cannot see the pattern.

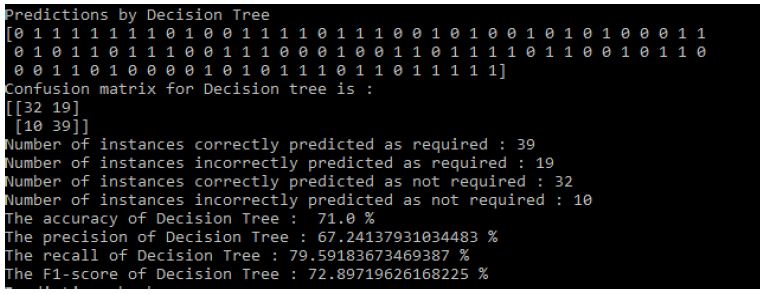

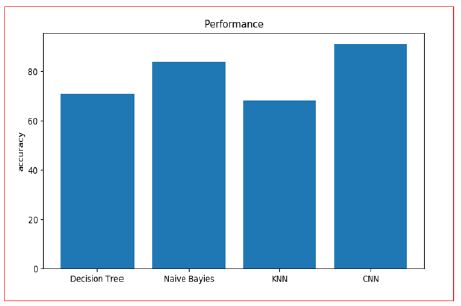

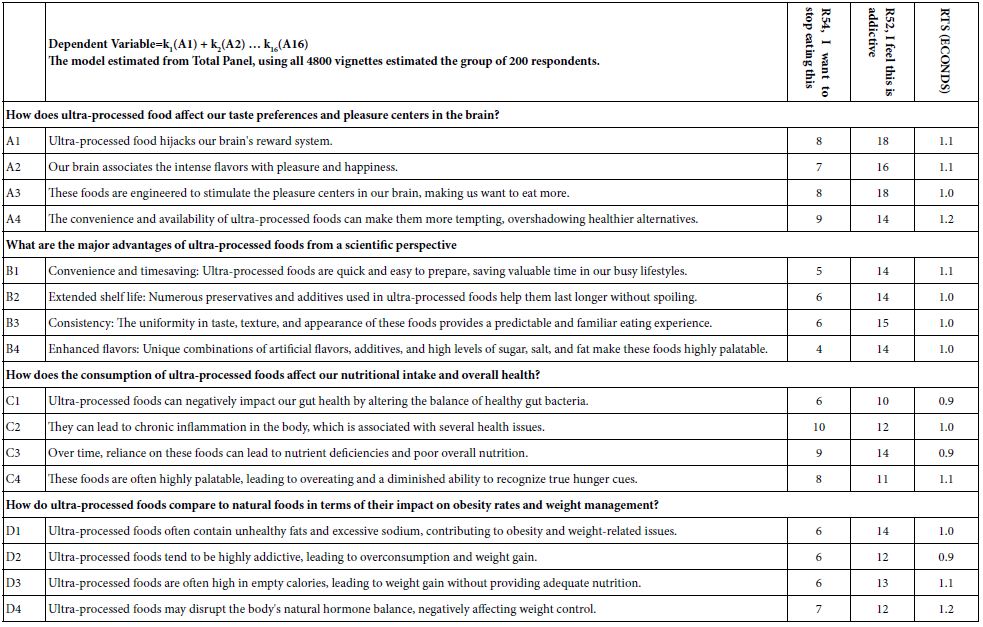

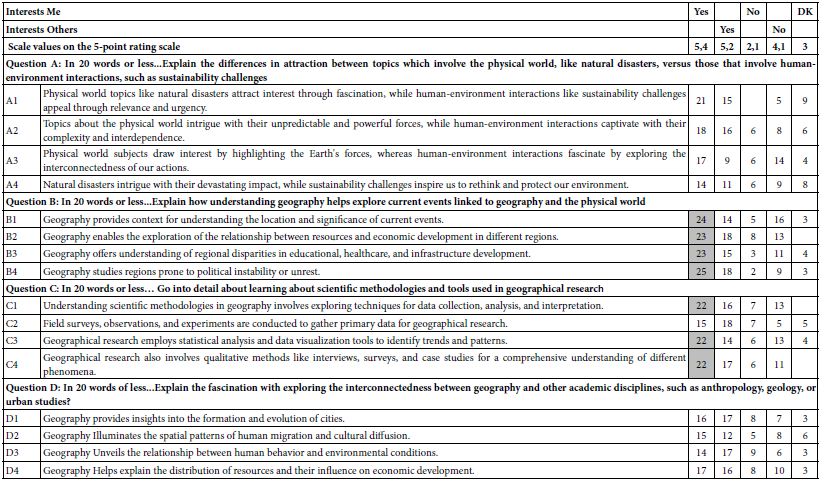

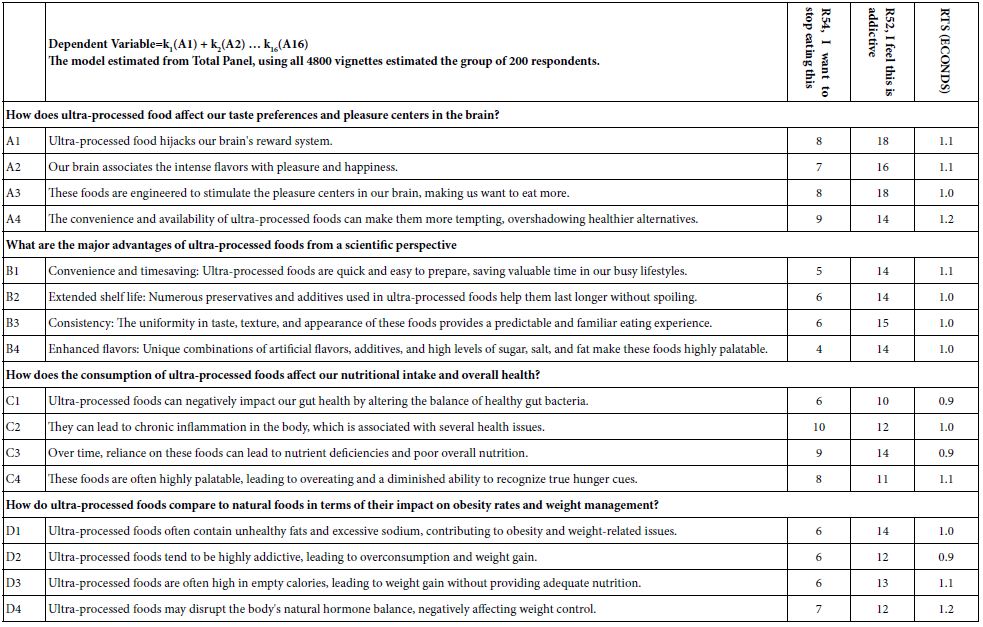

Statistical analyses suggest that coefficients around 15-16 are statistically significant. More important than significance is relevance. Coefficients of 21 or higher are deemed relevant, at least operationally, showing a strong connection to the scores. Table 3 suggests that no elements for R54 (want to quite eating) or R52 (are addicting) perform strongly. It may well be that the poor performance of these elements emerge because the research has thrown together a random 200 people of ‘all types.’ It is always the option of researchers that by breaking down the respondents into more meaningful groups, e.g., by whom they are, by what they do, by what they believe in general about food and health that our low coefficients will increase dramatically.

Table 3: The study particulars

Before moving to a deeper understanding of R54 (quit eating), it is instructive to look at the response times estimated by the weights assigned to the 16 elements. The Mind Genomics platform records the number of seconds between the presentation of the vignette and the rating assigned by the respondent, doing so to the nearest 100th of a second. For many respondents who multi-task, the response times van stretch out seconds. As a prophylactic step, all response times of 9 seconds or longer are brought to the arbitrary value of 9 seconds. Table 3 suggests that all the elements exhibit the approximately same response time, estimated to be between a low of 0.9 seconds and a high of 1.2 seconds. These are the estimated contributions to response time of each of the elements Once again we see some but not dramatic differences among elements.

What Drives ‘I Want to Stop Eating’ across Conventional Subgroups Defined by Who the Person Is?

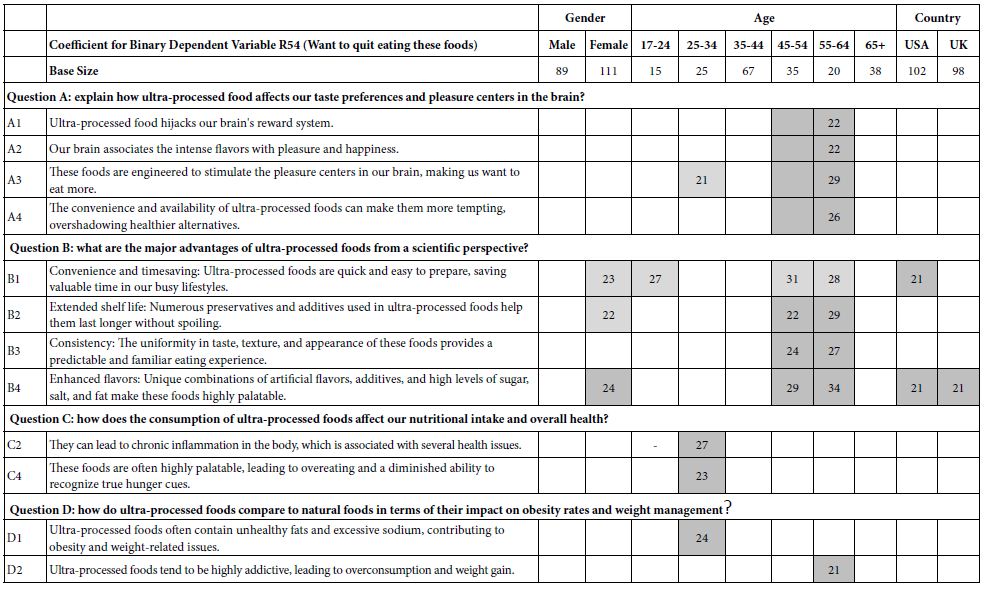

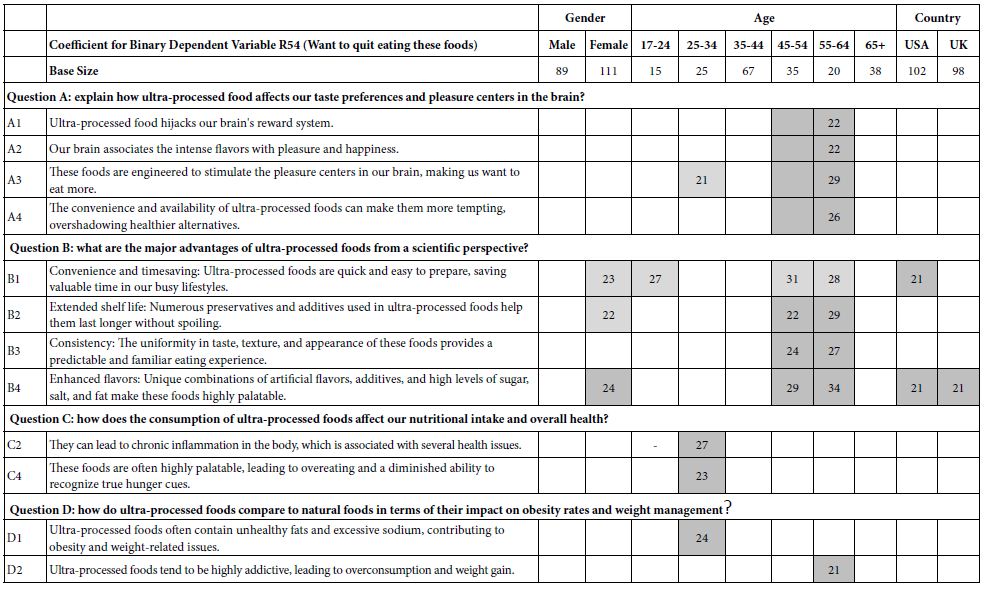

The systematic permutation of the experiment design across the 200 respondents ensures that a valid statistical analysis by OLS regression can be done for any combination of respondents. One standard analysis is done according to the convention geo-demographics. Table 4 shows the total panel broken out by gender, age, and country. To allow the patterns to emerge more clearly, only coefficients of 21 or higher are shown. The very strong coefficients, those 21 and higher, are shown in shaded cells. When the granularity is deepened in terms of ‘who the respondents are’ we end up with stronger results, but unfortunately with no clear patterns defined by the meaning of the elements. That is, elements stand out in terms of their driving power to make a respondent say, ‘I would like to stop eating this food’, but there is no clear interpretation of ‘why’.

Table 4: Additive model showing the coefficients relating the presence/absence of the 16 elements to three responses; want to stop eating (R54), believe it is addictive (R52) and response time to the element in seconds. All coefficients were estimated from the Total Panel.

Emergent Mind-sets Revealed by Clustering the Coefficients

A hallmark of Mind Genomics is the focus on emergent mind-sets at the granular level of the everyday. Many researchers focus on mind-sets, with the topic being well explored in the history of market segmentation (Reference). The traditional focus of clustering into mind-sets has begun from the top down, seeking large groups of what is believed to be first order segments. The effort, expense, and challenges of interpreting results have pushed so-called segmentation studies into the realm of the every expensive, also into the realm of what might be considered ‘hallmark studies.’ Doing segmentation studies to find out emergent mind-sets for small topics of importance to the everyday is simply not in the purview of conventional research.

The ease and the low expense, as well as the availability of simple DIY (do it yourself) software changes the focus, allowing research such as that presented here to reveal these mind-sets at the level of the granular, of the everyday. The simple precaution of having every respondent evaluate unique sets of 24 vignettes set up by experimental design means that it is straightforward to create a model for each individual. With 200 respondents, these individuals, each evaluating different combinations of vignettes, the statistics end up with 200 individual-level equations. The coefficients of the equations show how the individual element ‘drives’ the desire to stop eating, for each of the 16 elements, for one respondent.

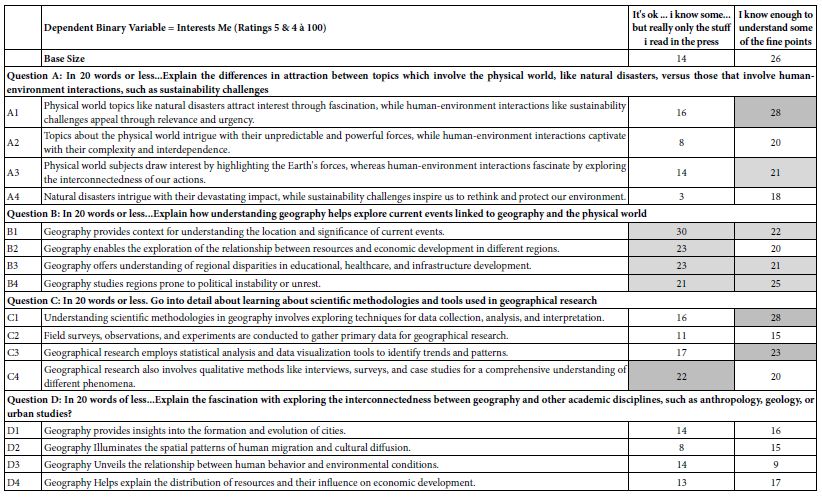

With 200 respondents, each generating a valid set of 16 coefficients, comparable across respondents, comparable across elements, they are able use k-means clustering to put the respondents into two and then three, or even more groups, such that the people within the group show similar patterns of coefficients, whereas the centroid of the groups are quite different from each other [22]. The measure of distance use is (1-Pearson Correlation(R). The Pearson Correlation, R, shows the strength of the linear relation between two sets of objects (e.g., the distance between two people based upon the pattern of their 16 coefficients). The clustering is totally mathematical, with no effort in interpreting.

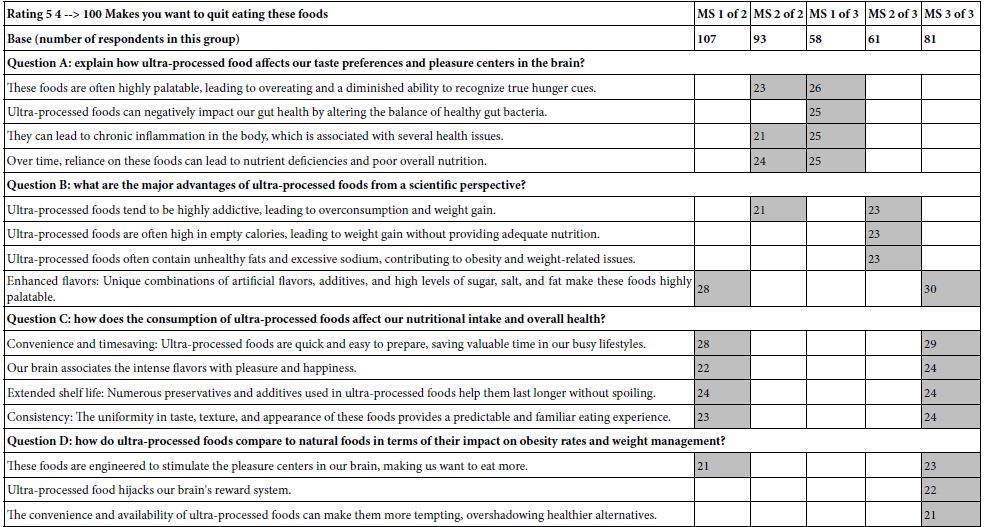

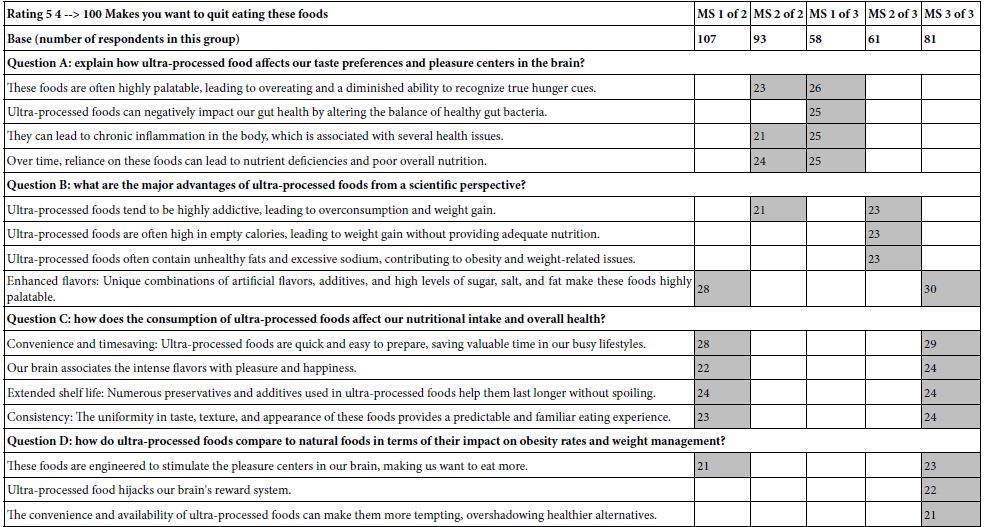

The ideal is to create two or perhaps three clusters, mutually exclusive and exhaustive, based upon the coefficients. These groups then become mind-sets. Table 5 presents the data from the two-mind-set solution emerging from clustering, and then the three-mind-set solution. When the clustering operates on the data without attempting to ‘tell a story’, at first the data are not particularly impressive. It is the job of clustering to put together like-minded people, based solely upon the patterns of the coefficients. We should expect nothing less than seeing strong performing elements.

Table 5: Additive models for key demographic groups, showing the coefficients relating the presence/absence of the 16 elements to the key transformed binary variable, R54 (want to stop eating). Only coefficients equal to or higher than 21 are shown, to allow patterns to emerge more clearly.

The results become far more remarkable when the strong elements for each mind-set are put together

Mind Set 1 of 2 – Focus on the composition of ingredients, and how the combinations affect our brain.

- Enhanced flavors: Unique combinations of artificial flavors, additives, and high levels of sugar, salt, and fat make these foods highly palatable.

- Convenience and timesaving: Ultra-processed foods are quick and easy to prepare, saving valuable time in our busy lifestyles.

- Extended shelf life: Numerous preservatives and additives used in ultra-processed foods help them last longer without spoiling.

- Consistency: The uniformity in taste, texture, and appearance of these foods provides a predictable and familiar eating experience.

- Our brain associates the intense flavors with pleasure and happiness.

- These foods are engineered to stimulate the pleasure centers in our brain, making us want to eat more.

Mind Set 2 of 2 – Focus on the negative effect of ultra-processed food on personal health.

- Over time, reliance on these foods can lead to nutrient deficiencies and poor overall nutrition.

- These foods are often highly palatable, leading to overeating and a diminished ability to recognize true hunger cues.

- They can lead to chronic inflammation in the body, which is associated with several health issues.

- Ultra-processed foods tend to be highly addictive, leading to overconsumption and weight gain.

Mind Set 1 of 3 – Focus on the negative effects, especially eating patterns. and effects on the body

- These foods are often highly palatable, leading to overeating and a diminished ability to recognize true hunger cues.

- Ultra-processed foods can negatively impact our gut health by altering the balance of healthy gut bacteria.

- They can lead to chronic inflammation in the body, which is associated with several health issues.

- Over time, reliance on these foods can lead to nutrient deficiencies and poor overall nutrition.

Mind Set 2 of 3 – Focus on scare tactics, using well-known issues.

- Ultra-processed foods tend to be highly addictive, leading to overconsumption and weight gain.

- Ultra-processed foods are often high in empty calories, leading to weight gain without providing adequate nutrition.

- Ultra-processed foods often contain unhealthy fats and excessive sodium, contributing to obesity and weight-related issues.

Mind Set 3 of 3 – Focus on food as giving pleasure and then causing addiction.

- Enhanced flavors: Unique combinations of artificial flavors, additives, and high levels of sugar, salt, and fat make these foods highly palatable.

- Convenience and timesaving: Ultra-processed foods are quick and easy to prepare, saving valuable time in our busy lifestyles.

- Our brain associates the intense flavors with pleasure and happiness.

- Extended shelf life: Numerous preservatives and additives used in ultra-processed foods help them last longer without spoiling.

- Consistency: The uniformity in taste, texture, and appearance of these foods provides a predictable and familiar eating experience.

- These foods are engineered to stimulate the pleasure centers in our brain, making us want to eat more.

- Ultra-processed food hijacks our brain’s reward system.

- The convenience and availability of ultra-processed foods can make them more tempting, overshadowing healthier alternatives.

Measuring the Strengths of the Ideas Evaluated in a Mind Genomics Study

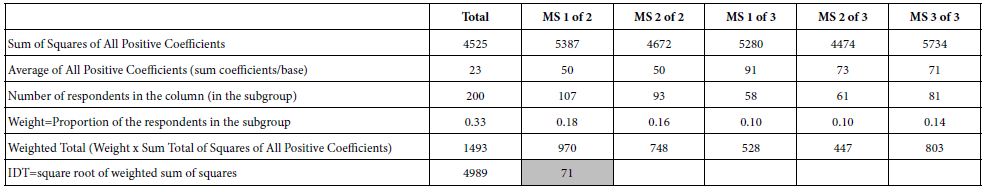

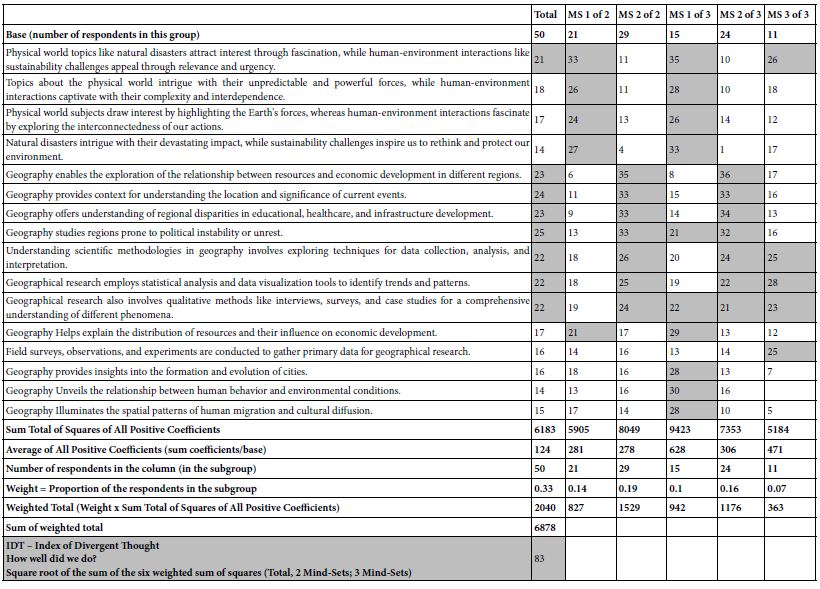

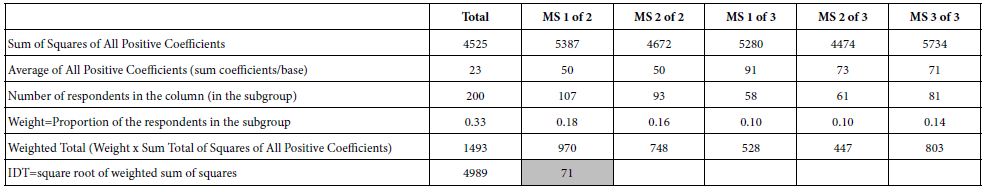

A continuing issue in the world of Mind Genomics is how one can measure the ‘strength’ of the ideas, and by doing so create a way to assess one’s own efforts in a particular project such as this study on ultra-processed food, or even to measure one’s growth in thinking and understanding a specific topic. Rather than having performance be a matter of opinion, always an option in science, it might be productive to create an index of the strength of the ideas. The operationally defined index is presented below, in Tables 6 and 7. The index is named IDT, Index of Divergent Thought. The calculations are shown in Table 6. Simply described, the IDT takes the positive coefficients for Total Panel, then for the two-set solution, and then for the three-mind-set solution, squares each, and weights the sum of square coefficients by the relative number of respondents. Since there are six groups, totaling 600 respondents, each column has a weight. For example, Mind-Set (MS) 1 of 2 comprises 107 respondents, thus having a weight of 0.18. The sum of squares for MS 1 of 2 is 5387, so the contribution is 0.18 x 5387 or 970. Summing the weighted sums of squares produces 4989. The square root is 71. That number 71 is the measure of the goodness of the thinking, the Index of Divergent thought. The IDT gives a metric which takes on meaning over time as researcher explores the topic and related topics.

Table 6: Additive models for mind-sets (clusters), showing the coefficients relating the presence/absence of the 16 elements to the key transformed binary variable, R54 (want to stop eating). Only coefficients equal to or higher than 21 are shown, to allow patterns to emerge more clearly.

Table 7: Index of Divergent Thought

Using AI to Interpret the Themes Emerging from the Strong Scoring Elements for Each Mind-set

AI Interpretation of themes which stop a person from eating ultra-processed foods (coefficients >= 21 for R54)

Mind Set 1 of 3 – Focus on the negative effects, especially eating patterns and effects on the body

Interested in:

Convenience and time-saving: Ultra-processed foods are quick and easy to prepare, saving valuable time in our busy lifestyles.; Ultra-processed foods can negatively impact our gut health by altering the balance of healthy gut bacteria.; They can lead to chronic inflammation in the body, which is associated with several health issues.; Over time, reliance on these foods can lead to nutrient deficiencies and poor overall nutrition.; These foods are often highly palatable, leading to overeating and a diminished ability to recognize true hunger cues.;

Create a label for this segment:

Time-conscious and Health-conscious Consumers

Describe this segment:

This segment consists of individuals who prioritize convenience and timesaving in their daily lives. They are attracted to ultra-processed foods because they are quick and easy to prepare, allowing them to save valuable time. However, their reliance on these foods comes with several negative consequences. Firstly, ultra-processed foods can negatively affect their gut health by disrupting the balance of healthy gut bacteria. This can lead to various digestive issues and potentially affect their overall well-being. Secondly, consuming these foods can result in chronic inflammation in the body, which is associated with a range of health problems. Additionally, individuals in this segment may face nutrient deficiencies and poor overall nutrition due to the limited nutritional content of ultra-processed foods. Moreover, these foods tend to be highly palatable, leading to overeating and a diminished ability to recognize true hunger cues. Overall, this segment is characterized by a preference for convenience and timesaving, but their reliance on ultra-processed foods can negatively impact their health and overall nutrition.

Describe the attractiveness of this segment as a target audience:

The target audience for the attributes described in this research study would be individuals who value convenience and time-saving methods when it comes to their food choices. This segment would likely consist of busy individuals or those with hectic lifestyles who prioritize efficiency and ease in their daily routines. They would be interested in ultra-processed foods that require minimal preparation time, allowing them to save valuable time in their packed schedules.

However, it is important to note that while this segment may find ultra-processed foods attractive for their convenience, there are several negative health implications associated with these types of foods. The study suggests that these foods can negatively impact gut health, lead to chronic inflammation in the body, and result in nutrient deficiencies and poor overall nutrition.

Thus, the attractiveness of this segment as a target audience is somewhat compromised by these health concerns. While they may be drawn to the convenience and time-saving aspects of ultra-processed foods, it is crucial to educate this audience about the potential risks and encourage them to prioritize healthier alternatives that provide both convenience and nutritional value.

Explain why this segment might not be attractive as a target audience:

This segment might not be attractive as a target audience because they are likely to prioritize convenience and timesaving over their health. They may not be motivated to make dietary changes or prioritize their overall well-being. Additionally, their reliance on ultra-processed foods can lead to negative health consequences such as gut health issues, chronic inflammation, nutrient deficiencies, and poor nutrition. This suggests that they may not have a strong interest in maintaining a healthy lifestyle or may not be receptive to messages promoting healthier food choices. Moreover, the fact that these foods are highly palatable and can lead to overeating indicates that this segment may have difficulty practicing portion control or recognizing true hunger cues.

List what is missing or should be known about this segment, in question form:

- How do ultra-processed foods save time and provide convenience compared to other food options?

- What specific alterations do ultra-processed foods cause in the balance of healthy gut bacteria?

- Which health issues are specifically associated with chronic inflammation caused by consuming ultra-processed foods?

- What are the specific nutrient deficiencies that can arise from relying on ultra-processed foods?

- How does the high palatability of ultra-processed foods result in overeating?

- What factors contribute to a diminished ability to recognize true hunger cues when consuming ultra-processed foods?

List and briefly describe attractive new or innovative products, services, experiences, or policies for this segment:

- Healthy convenience meal kits: These meal kits provide the convenience of ultra-processed foods but with a focus on healthier ingredients and preparation methods. They could include pre-packaged, pre-portioned, and pre-prepared ingredients that are minimally processed and rich in nutrients.

- Gut-friendly ultra-processed alternatives: Companies could develop ultra-processed foods that are specifically designed to support gut health. These products could contain ingredients that promote the growth of beneficial gut bacteria, such as prebiotics and probiotics.

- Anti-inflammatory food options: An innovative approach would be to create ultra-processed foods that are formulated to have anti-inflammatory properties. These products could contain ingredients known for their anti-inflammatory effects, such as certain spices, herbs, and plant-based oils.

- Nutrient-fortified ultra-processed foods: To address the issue of nutrient deficiencies, companies could develop ultra-processed foods that are enriched with essential vitamins, minerals, and other nutrients. This could help individuals maintain adequate nutrient intake while consuming these convenient food options.

- Mindful eating apps and tools: Innovative services could include smartphone apps or other tools that help individuals develop mindfulness around their eating habits. These apps could provide reminders to eat slowly, track hunger and fullness levels, and offer tips for recognizing true hunger cues.

- Personalized nutritional guidance: Services could be developed that provide personalized nutritional guidance for individuals who rely on ultra-processed foods. This could involve online platforms or apps that offer tailored meal plans or recommendations based on an individual’s specific dietary needs and goals.

- Industry regulations and labeling: Policies could be implemented that enforce stricter regulations on the labeling of ultra-processed foods. This could help consumers make more informed choices by providing clear information about the nutritional content and potential health impacts of these products.

Which messages will interest this segment?

This segment would likely be interested in messages related to the negative impacts of ultra-processed foods on their health. They may be particularly interested in messages about how these foods can negatively impact gut health, contribute to chronic inflammation, and lead to nutrient deficiencies and poor overall nutrition. They may also be interested in messages about the potential negative effects on weight and appetite control, such as overeating and diminished ability to recognize true hunger cues.

Mind-Set 2 of 3: Focus on scare tactics using well known issues Interested in:

Ultra-processed foods often contain unhealthy fats and excessive sodium, contributing to obesity and weight-related issues; Ultra-processed foods tend to be highly addictive, leading to overconsumption and weight gain; Ultra-processed foods are often high in empty calories, leading to weight gain without providing adequate nutrition.

Create a label for this segment:

“Processed Food Detractors”

Describe this segment:

This segment of the research study is discussing the attributes of ultra-processed foods. The description highlights several negative characteristics of these foods. Firstly, it states that ultra-processed foods often have unhealthy fats and excessive sodium, which can contribute to obesity and weight-related issues. Secondly, it suggests that these foods tend to be highly addictive, leading to overconsumption and weight gain. Lastly, it mentions that ultra-processed foods are often high in empty calories, meaning they provide little to no nutritional value and can result in weight gain without meeting the body’s nutritional needs. Overall, this segment focuses on the negative impacts of ultra-processed foods on weight and overall health.

Describe the attractiveness of this segment as a target audience:

The segment of individuals who consume ultra-processed foods may not be considered an attractive target audience from a health-focused standpoint. This is because these individuals are prone to obesity and weight-related issues due to the unhealthy fats and excessive sodium present in such foods. Moreover, ultra-processed foods tend to be highly addictive, which can lead to overconsumption and further weight gain.

Additionally, these foods are often high in empty calories, meaning they provide little to no nutritional value while contributing to weight gain. Hence, this segment may not be seen as attractive from a nutritional standpoint since they are likely to have inadequate nutrition despite gaining weight.

However, it is important to note that from a marketing perspective, this segment might still have potential as a target audience due to their consumption patterns. Ultra-processed foods are commonly accessible and widely consumed, therefore indicating a potential market size.

Explain why this segment might not be attractive as a target audience:

This segment might not be attractive as a target audience for a few reasons.

Firstly, this segment’s consumption of ultra-processed foods suggests a lack of awareness or concern about healthy eating habits. They may prioritize convenience or taste over the nutritional value of their food choices. This preference for unhealthy options may indicate a resistance to change or a lack of motivation to adopt healthier behaviors. As a result, targeting this segment may require significant effort and resources to overcome their existing habits and attitudes towards food.

Additionally, this segment’s tendency to over consume ultra-processed foods due to their addictive nature poses a challenge. Their behavior of overeating can make it harder to promote balanced eating habits or promote portion control. It might be challenging to convince them to reduce their consumption or change their eating preferences.

Moreover, the fact that ultra-processed foods high in empty calories contribute to weight gain without providing adequate nutrition is another reason why this segment may not be an attractive target audience. Convincing them to prioritize nutrition and the long-term health effects of their food choices may be difficult, as their current habits suggest a focus on immediate gratification rather than the overall quality of their diet.

Overall, the combination of their preference for ultra-processed foods, overconsumption, and disregard for adequate nutrition makes this segment less attractive as a target audience. Effectively influencing their behaviors would require significant effort, resources, and potentially a major shift in their attitudes towards food and health.

List what is missing or should be known about this segment, in question form:

- What specific types of ultra-processed foods were included in the study’s sample?

- Did the research study investigate the relationship between the consumption of ultra-processed foods and specific weight-related issues, such as diabetes or cardiovascular diseases?

- What criteria were used to classify the foods as ultra-processed?

- Were there any specific demographic characteristics (age, gender, socioeconomic status) of the participants that could have influenced the findings?

- How was the overconsumption of ultra-processed foods assessed in the study?

- Were there any other factors, aside from the addictive properties of ultra-processed foods, which could have contributed to weight gain in the participants?

- Did the study consider any potential confounding variables that could affect the relationship between ultra-processed foods and weight-related issues?

- Were the participants’ dietary patterns or overall diets considered while analyzing the association between ultra-processed foods and weight gain?

- How long was the study conducted, and did it examine any long-term effects of consuming ultra-processed foods?

- Did the research study compare the effects of ultra-processed foods to those of minimally processed or unprocessed foods on weight-related issues?

List and briefly describe attractive new or innovative products, services, experiences, or policies for this segment:

- “Clean Label” Ultra-Processed Foods: These are new products that aim to provide ultra-processed foods while minimizing the use of unhealthy fats and excessive sodium. These foods prioritize natural ingredients and are free from artificial additives, appealing to health-conscious consumers who still desire the convenience of processed foods.

- Nutrient-Enriched Ultra-Processed Foods: These innovative products add essential nutrients, such as vitamins, minerals, and fiber, to ultra-processed foods. By fortifying these products, they provide added nutritional value, making them a more attractive option for individuals concerned about weight gain and inadequate nutrition.

- Personalized Nutrition Apps: With the rise of smartphone technology, personalized nutrition apps can provide tailored recommendations and tracking for individuals consuming ultra-processed foods. These apps can help users make healthier choices within the constraints of their diet preferences, providing guidance on portion sizes, healthier alternatives, and overall nutritional balance.

- Reduced-Sodium Ultra-Processed Foods: In response to concerns about excessive sodium consumption, innovative products are minimizing sodium content in ultra-processed foods without sacrificing taste. These new options cater to individuals who are concerned about their weight and health but still crave the convenience and flavors of processed foods.

- Regulation of the Ultra-Processed Food Industry: Policy changes that aim to regulate and control the production and marketing of ultra-processed foods can have a significant impact. Introducing stricter labeling requirements, limiting advertising to children, and promoting healthier alternatives through taxation or subsidies can help steer consumers towards more nutritious options and improve overall public health.

Overall, these new and innovative products, services, experiences, or policies offer ways to address the negative attributes associated with ultra-processed foods. By improving the nutritional profile, personalizing choices, and regulating the industry, these options aim to promote healthier eating habits and combat the obesity and weight-related issues often associated with ultra-processed foods.

Which messages will interest this segment?

This segment may be interested in messages that highlight the negative impact of ultra-processed foods on health and weight-related issues. They might be particularly interested in messages that emphasize the unhealthy fats, excessive sodium, and empty calories found in these foods, which can contribute to obesity and lack of proper nutrition. They may also respond to messages that mention the addictive nature of ultra-processed foods, leading to overconsumption and weight gain.

Mindset 3 of 3: Focus on food as giving pleasure and then causing addiction

Interested in:

Ultra-processed food hijacks our brain’s reward system.; Our brain associates the intense flavors with pleasure and happiness.; These foods are engineered to stimulate the pleasure centers in our brain, making us want to eat more.; Convenience and time-saving: Ultra-processed foods are quick and easy to prepare, saving valuable time in our busy lifestyles.; Extended shelf life: Numerous preservatives and additives used in ultra-processed foods help them last longer without spoiling.; Consistency: The uniformity in taste, texture, and appearance of these foods provides a predictable and familiar eating experience.; Enhanced flavors: Unique combinations of artificial flavors, additives, and high levels of sugar, salt, and fat make these foods highly palatable.;

Create a label for this segment:

“Ultra-Processed Food Lovers”

Describe this segment:

This segment of the research study focuses on the various attributes of ultra-processed foods. It highlights how these foods can hijack our brain’s reward system by associating intense flavors with pleasure and happiness. The engineered nature of ultra-processed foods is emphasized, as they are specifically designed to stimulate the pleasure centers in our brain, leading to a desire to consume more of these foods.

The convenience and time-saving aspect of ultra-processed foods is discussed, as they are quick and easy to prepare, catering to busy lifestyles. Additionally, the use of numerous preservatives and additives in these foods allows for an extended shelf life, preventing them from spoiling quickly.

Consistency is another attribute mentioned, pointing out that ultra-processed foods deliver a predictable and familiar eating experience in terms of taste, texture, and appearance. This ensures a consistent consumer experience with these foods.

Furthermore, the enhanced flavors of ultra-processed foods are elaborated upon, with the inclusion of artificial flavors, additives, and high levels of sugar, salt, and fat. These combinations make these foods highly palatable, further contributing to their appeal.

Overall, this segment of the research study provides a comprehensive description of the attributes associated with ultra-processed foods, highlighting their impact on the brain’s reward system, convenience, shelf life, consistency, and their palatability due to enhanced flavors.

Describe the attractiveness of this segment as a target audience:

The attractiveness of this segment as a target audience is likely to be high. The description highlights several factors that make ultra-processed foods appealing to consumers. The fact that these foods hijack the brain’s reward system and create associations with pleasure and happiness suggests that individuals are likely to have a strong desire for these products.

The convenience and time-saving aspect of ultra-processed foods also makes them attractive to busy individuals who are looking for quick and easy meal options. This aligns with the busy lifestyles of many people today and can be highly appealing for those who are pressed for time.

Additionally, the extended shelf life provided by preservatives and additives makes these foods appealing to those who want their meals to last longer without spoiling. This can be particularly beneficial for individuals who prioritize budgeting or minimizing grocery shopping trips.

The consistency in taste, texture, and appearance of ultra-processed foods provides a predictable and familiar eating experience, which can be attractive to those who seek comfort or are resistant to change. Similarly, the unique combinations of flavors and high levels of sugar, salt, and fat enhance the palatability of these foods, appealing to individuals who crave rich and indulgent tastes.

Overall, the attractiveness of this segment lies in the combination of factors that make ultra-processed foods highly desirable. From the pleasure-inducing effects on the brain to the convenience and consistency they offer, these attributes make them an appealing target audience for marketers.

Explain why this segment might not be attractive as a target audience:

This segment might not be attractive as a target audience because the attributes mentioned are associated with negative health effects. The fact that ultra-processed foods hijack our brain’s reward system and stimulate the pleasure centers in our brain may lead to overeating and contribute to unhealthy eating habits. The extended shelf life and convenience of these foods may promote a sedentary lifestyle and discourage the consumption of fresh, nutritious food. Additionally, the high levels of artificial flavors, additives, sugar, salt, and fat in ultra-processed foods can be detrimental to one’s health and contribute to obesity, diabetes, heart disease, and other chronic conditions. Therefore, targeting this segment may not align with promoting a healthy and balanced lifestyle.

List what is missing or should be known about this segment, in question form:

- What are the potential negative health impacts of consuming ultra-processed foods?

- Are there any regulations in place regarding the use of preservatives and additives in ultra-processed foods?

- How do ultra-processed foods compare in nutritional value to unprocessed or minimally processed foods?

- Are there any specific ultra-processed foods that have been linked to particular health concerns?

- What are the long-term effects of regularly consuming ultra-processed foods?

- Are there any alternative options or healthier alternatives to ultra-processed foods?

- Are there any differences in the effects of ultra-processed foods on various age groups or populations?

- How do personal preferences and cultural factors influence the consumption of ultra-processed foods?

- Is there a correlation between the increasing availability and consumption of ultra-processed foods and rising rates of certain health conditions?

- What strategies can be implemented to reduce the consumption of ultra-processed foods in society?

List and briefly describe attractive new or innovative products, services, experiences, or policies for this segment:

- Healthier alternatives to ultra-processed foods: Companies can develop innovative products that offer a healthier alternative to ultra-processed foods. This can include ready-made meals or snacks that are made with natural ingredients, lower in sugar, salt, and fat, and free from artificial additives.

- Personalized meal planning services: Services that provide personalized meal plans based on individual preferences and nutritional needs can help people make healthier food choices. These services can also include pre-prepared meals that are made with fresh, whole foods and are delivered to the customer’s doorstep.

- Mindful eating apps: Mobile applications that promote mindful eating can help individuals overcome the intense cravings for ultra-processed foods by providing tools and techniques to manage emotional eating and develop healthier eating habits. These apps can include features such as guided meditation, food diaries, and tips for healthier snacking.

- Education and awareness campaigns: Policies that focus on educating the public about the negative effects of consuming ultra-processed foods and raise awareness about healthier alternatives can be effective in encouraging people to make healthier food choices. This can include campaigns through various media channels, public health programs, and collaboration with schools and community organizations.

- Strategic placement of healthy options: Policy measures that ensure healthy food options are readily available and prominently displayed in supermarkets, cafeterias, and other food retail establishments can make it easier for individuals to choose healthier alternatives instead of ultra-processed foods. This can involve collaborations with food retailers to promote and highlight nutritious options.

- Promotion of home cooking: Encouraging and supporting home cooking through policies that provide incentives, such as tax breaks or subsidies for purchasing fresh ingredients or kitchen equipment, can empower individuals to prepare their meals using whole and unprocessed ingredients. This can also be complemented by educational programs that teach cooking skills and provide recipe ideas for quick and healthy meals.

- Labeling and transparency: Policies that mandate clear and easy-to-understand labeling on food packaging can help individuals make informed choices by providing information about the level of processing, artificial additives, and nutritional content. This can empower consumers to select healthier options and avoid ultra-processed foods.

- Community gardens and urban farming initiatives: Creating community gardens or supporting urban farming initiatives can promote access to fresh and local produce, making it easier for individuals to incorporate healthier foods into their diets. These initiatives can also foster community engagement and social connections around food.

Which messages will interest this segment?

- “Discover how ultra-processed foods can hijack your brain’s reward system.”

- “Learn how the intense flavors of ultra-processed foods can bring pleasure and happiness.”

- “Uncover the science behind how ultra-processed foods stimulate the pleasure centers in your brain, making you crave more.”

- “Save valuable time with quick and easy-to-prepare ultra-processed foods.”

- “Enjoy the extended shelf life of ultra-processed foods, thanks to preservatives and additives.”

- “Experience the consistency in taste, texture, and appearance of ultra-processed foods for a predictably satisfying meal.”

- “Indulge in the enhanced flavors of ultra-processed foods, with unique combinations of artificial flavors, additives, and high levels of sugar, salt, and fat.”

Discussion and Conclusions

The history of social attitudes is a long and complex one. Only in the last century has the world of researching social attitudes emerged with new ideas. Hallowed approaches such as focus groups, surveys about topics, public opinion polls and now text mining of the available literature and press have provided much of what we know about how people feel. One need only visit the library to get a sense of the depth of knowledge that was acquired by researchers of the time. And, for those projects not guaranteeing a book, there are always the papers in the journals of then and now, for these shorter efforts.

At the same time, however, during the past fifty years the harder sciences, including psychology, have migrated away from books to journals, with the style of short, focused reports. These papers are less readable, more stylized, representing a new way to present information. This new way is considered to be professional because it focuses on a topic, presets a relevant literature review, an appropriate experiment, statistical analysis, and then discussion and conclusions.

When we compare the traditional studies of social and psychological issues to the shorter, focused, reports about experimental studies, we find far more flexibility in the harder sciences. The flexibility is not so much in the way the data are reported as the ability to carve out a piece of the world, and study it, focusing deeply on manipulating the piece of world and then measuring it. Social and traditional psychology research does not have that desirable capability.

The introduction of Mind Genomics adds a new dimension to social and attitudinal research. The underlying worldview of Mind Genomics is a combination of focus on the everyday, along with experimentation. Rather than asking the respondent to give an opinion, e.g., about desire to stop eating foods or the belief that the food is addictive, Mind Genomics actually does an experiment, to identify which particular messages, if any, drive the perception. As such, Mind Genomics brings social research to a new direction, where the topics of the everyday can be more deeply explored, with a richness of information. Rather than having to infer much of the richness from pulling together a picture from disparate sources, the Mind Genomics ‘program’ in its scientific meaning creates a matrix of direct knowledge from the responses of people to relevant stimuli. Indeed, the strong performing elements from Mind-Sets 1 of 3, 2 of 3, and 3 of 3, present to us information in a direct format, information that would have to be distilled from far more effortful, less direct source of information.

To conclude, therefore, this paper suggests that issues of attitudes can be straightforwardly investigated by experiments, using cognitively rich stimuli, in a manner that cannot be gamed, and in a fashion which immediately reveals the nature of people, and th different types of thinking about the same problem, not by those who are measurably different, but by those who think differently about the same micro-topic.

References

- Caul JF (1957) The profile method of flavor analysis. Advances in Food Research 7: 1-40.

- Sjostrom LB, Cairncross SE (1952) What makes flavor leadership? Food Technology 6: S22-S22.

- GORDON J (1965) Evaluation of sugar-acid-sweetness relationships in orange juice by a response surface approach. Journal of Food Science 30: 903-907.

- Moskowitz H (2004) From psychophysics to the world…. data acquired, lessons learned. Food Quality and Preference 15: 633-644.

- Moskowitz H, Krieger B (1998) International product optimization: a case history. Food Quality and Preference 9: 443-454.

- Moskowitz Howard R, Kathleen Wolfe, Charles Beck (1979) Sweetness and acceptance optimization in cola flavored beverages using combinations of artificial sweeteners-a psychophysical approach. Journal of Food Quality 2: 17-26.

- Moskowitz HR (2022) The perfect is simply not good enough–Fifty years of innovating in the world of traditional foods. Food Control 138: 109026.

- Askari M, Heshmati J, Shahinfar H, Tripathi N, Daneshzad E (2020) Ultra-processed food and the risk of overweight and obesity: a systematic review and meta-analysis of observational studies. International Journal of Obesity 44: 2080-2091. [crossref]

- Blanco-Rojo R, Sandoval-Insausti H, López-Garcia E, Graciani A, Ordovas JM, et al. (2019) Consumption of ultra-processed foods and mortality: a national prospective cohort in Spain. Mayo Clinic Proceedings 94: 2178-2188. [crossref]

- Elizabeth L, Machado P, Zinöcker M, Baker P, Lawrence M (2020) Ultra-processed foods and health outcomes: a narrative review. Nutrients 12: 1955. [crossref]

- Neri, Daniela, Eurídice Martínez Steele, Neha Khandpur, Gustavo Cediel, Maria Elisa Zapata, et al. (2022) Ultraprocessed food consumption and dietary nutrient profiles associated with obesity: A multicountry study of children and adolescents. Obesity Reviews 23: e13387. [crossref]

- Poti JM, Braga B, Qin B (2017) Ultra-processed food intake and obesity: what really matters for health—processing or nutrient content?. Current Obesity Reports 6: 420-431. [crossref]

- Gearhardt AN, Grilo CM, DiLeone RJ, Brownell KD, Potenza MN (2011) Can food be addictive? Public health and policy implications. Addiction 106: 1208-1212. [crossref]

- Malan H, Watson TD, Slusser W, Glik D, Rowat AC, Prelip M (2020) Challenges, opportunities, and motivators for developing and applying food literacy in a university setting: A qualitative study. Journal of the Academy of Nutrition and Dietetics 120: 33-44. [crossref]

- Sarmiento-Santos J, Souza MB, Araujo LS, Pion JM, Carvalho RA, et al. (2022) Consumers’ understanding of ultra-processed foods. Foods 11: 1359. [crossref]

- Moskowitz HR (2012) ‘Mind Genomics’: The experimental, inductive science of the ordinary, and its application to aspects of food and feeding. Physiology & behavior 107: 606-613. [crossref]

- Moskowitz HR, Gofman A (2007) Selling Blue Elephants: How to Make Great Products that People Want Before They Even Know They Want Them. Pearson Education.

- Moskowitz HR, Gofman A, Beckley J, Ashman H (2006) Founding a new science: Mind Genomics. Journal of Sensory Studies 21: 266-307.

- Porretta S, Gere A, Radványi D, Moskowitz H (2019) Mind Genomics (Conjoint Analysis): The new concept research in the analysis of consumer behaviour and choice. Trends in Food Science & Technology 84: 29-33.

- Gofman A, Moskowitz H (2010) Isomorphic permuted experimental designs and their application in conjoint analysis. Journal of Sensory Studies 25: 127-145.

- Hardy MA (1993) Regression with Dummy Variables. 93 Sage.

- Likas A, Vlassis N, Verbeek JJ (2003) The global k-means clustering algorithm. Pattern Recognition 36: 451-461.