DOI: 10.31038/NAMS.2023622

Abstract

In this study, a novel polyaniline/graphitic carbon nitride/zinc tungstate (PANI/g-C3N4/ZnWO4) (PGZ) ternary nanocomposites (NCs) as a heterostructure photocatalys was examined during photocatalytic degradation process in the efficient removal of glyphosate herbicide from a aqueous solution. Different pH values (3.0, 5.0, 7.0, 9.0 and 11.0), increasing glyphosate concentrations (5 mg/l, 10 mg/l, 15 mg/l and 20 mg/l), increasing PANI/g-C3N4/ZnWO4 ternary NCs concentrations (5 mg/l, 15 mg/l, 30 mg/l and 45 mg/l) and increasing recycle times (1., 2., 3., 4., 5., 6. and 7.) was operated during photocatalytic degradation process in the efficient removal of glyphosate in a aqueous solution. The characteristics of the synthesized nanoparticles (NPs) were assessed using X-Ray Difraction (XRD), Field Emission Scanning Electron Microscopy (FESEM), Energy-Dispersive X-Ray (EDX), Fourier Transform Infrared Spectroscopy (FTIR), Transmission Electron Microscopy (TEM), Diffuse reflectance UV-Vis spectra (DRS) and X-Ray Photoelectron Spectroscopy (XPS) analyses, respectively. The cyctotoxicity test was operated to the standard TBE (trypan blue dye exclusion) assay technique with Drosophila melanogaster (fruit fly). ANOVA statistical analysis was used for all experimental samples. The maximum 99% glyphosate removal efficiency was obtained during photocatalytic degradation process in aqueous solution, at 15 mg/l gylphosate, at 30 mg/l PANI/g-C3N4/ZnWO4 ternary NCs, at pH=11.0, at 150 W UV-vis light irradiation power, after 180 min photocatalytic degradation time and at 25°C, respectively. The maximum 99% cyctotoxicity removal was observed at untreated glyphosate samples, after 180 min photocatalytic degradation time, at 150 W UV-vis light irradiation power, at pH=7.0 and at 25°C, respectively. The maximum 99% cyctotoxicity removal was observed at 5 mg/l PANI/g-C3N4/ZnWO4 ternary NCs photocatalyst concentrations, after 180 min photocatalytic degradation time, at 150 W UV-vis light irradiation power, at pH=7.0 and at 25°C, respectively. The study revealed the excellent minimization of cytotoxicity of glyphosate after photocatalytic degradation process with the PANI/g-C3N4/ZnWO4 ternary NCs photocatalyst. As a result, the PANI/g-C3N4/ZnWO4 ternary NCs photocatalyst is found to be non-cytotoxic irrespective of its quantity used. Finally, the combination of a simple, easy operation preparation process, excellent performance and cost effective, makes this a novel PANI/g-C3N4/CoMoO4 ternary NCs heterostructure photocatalyst a promising option during photocatalytic degradation process in agricultural industry wastewater treatment.

Keywords

ANOVA statistical analysis, Cytotoxicity test, Diffuse reflectance UV-Vis spectra (DRS), Drosophila melanogaster (fruit fly), Electrochemical filtration process, Energy-dispersive X-ray (EDX), Field emission scanning electron microscopy (FESEM), Fourier transform infrared spectroscopy (FTIR), Gylphosate, Herbicites, Ionic liquid-assisted synthesis, Novel polyaniline/graphitic carbon nitride/zinc tungstate (PANI/g-C3N4/ZnWO4) ternary nanocomposites, Pesticides, Photocatalytic degradation, Transmission electron microscopy (TEM), X-ray difraction (XRD), X-ray photoelectron spectroscopy (XPS)

Introductıon

The intense populational growth and industrial expansion in the most diverse segments of society have led to a substantial increase in the demand for drinking water supply and large-scale food production [1]. Thus, to increase productivity at an economically profitable level, the employment of agrochemicals has been widely used to combat pests and weeds [2]. With the enhanced use of a new variety of anthropogenic compounds towards industrialization, water pollution has increased substantially [3]. Anthropogenic compounds like synthetic pesticides and herbicides are often used in agricultural fields to protect crops. However, pesticides are characterized by low biodegradability, high bioaccumulative capacity arising from their physicochemical properties, and a long half-life, of 5-15 years, increasing their toxicity to the environment and humans [4,5]. Thus, pesticide persistence in soil, wastewater, ground, and surface water has proved to be a considerable environmental problem, and may be compounded along the food chain, reaching concentrations toxic to human health [6]. Due to their high stability, these compounds can contaminate areas distant from pulverization through water volatilization and soil absorption. Studies have associated exposure to compounds with hormonal changes in the immune, neurological and cardiac systems, as well as with the development of neoplasms [7,8].

For this purpose, diverse techniques, such as adsorption and advanced oxidative processes (AOPs), which include Fenton, photo-fenton, heterogeneous photocatalysis and ozonation systems, have been explored for removing and degrading biopersistent organic compounds [9-11]. AOPs are based on the generation of free radicals, e.g., hydroxyl (OH●) and superoxide (O2– ●) radicals, which have high oxidizing power in an aqueous solution and are able to degrade pollutants into lower molecular weight intermediates and inorganic precursors [12,13]. Heterogeneous photocatalysis is an advanced oxidative process that occurs through the photoactivation (by sunlight or artificial light) of a semiconductor, which uses water molecules and dissolved oxygen as reagents of oxi-reduction reactions [14]. This technique is very efficient and promising for the degradation of organic pollutants, including dyes, drugs and pesticides [15,16]. Among the materials used, metallic nanooxides (zinc oxide, ZnO and titanium dioxide, TiO2) have been largely employed due to their excellent properties, such as low toxicity, good availability, chemical stability, large surface area/porosity, and photocorrosion [17,18]. However, these conventional nanocatalysts are characterized by their high bandgap energy, which is the energy required to start photocatalytic reactions. Additionally, due to their high surface energy, they tend to agglomerate during the photocatalytic process. Therefore, the association of these nanocatalysts with a second, less active material (called catalytic support or matrix) can solve these drawbacks, even when the active material is dispersed in low concentrations (ca. 0.5-5 wt%) on the support [19]. Thus, combining the two materials results in a new material called NCs, in which the active substance is in the above-mentioned concentration range and this is named the reinforcement phase [20].

NCs are multiphase materials formed by a continuous and dispersed phase and have at least one dimension in the nanoscale [21]. The continuous phase (matrix) consists of a compound of polymeric, ceramic or metallic origin, while the dispersed phase (reinforcement) is commonly derived from fibrous materials [22-24]. NCs materials are synthesized to combine individual properties and reduce limitations, such as physicochemical and thermal instability, expanding the scope of applications. In parallel, at the nanoscale, the materials exhibit distinct behaviors to those found at the micrometer scale, such as volume/area relationship and increased reactivity [25]. Another technique widely used for pesticide removal from wastewater consists of adsorption, especially when using nanomaterials (adsorbents), due to its simplicity of operation, relatively low cost, and low energy requirements [26]. In addition, nanoadsorbents are characterized by their high specific surface area, chemical/thermal stability, and affinity for organic pollutants [27]. Although the efficiency of nanoadsorbents in the removal of organic compounds is remarkable, there are still limitations to conventional materials’ use, such as separation from the aqueous medium and the reuse of nanoadsorbents and nanocatalysts [28]. Recently, the development of nanocomposites as nanoadsorbents has been the subject of diverse research due to their increased surface area and physicochemical stability. Moreover, magnetic NCs have been used as a good alternative to improve the stability, textural properties, and reuse of nanoadsorbents [29]. The facilities separate material from the aqueous medium and considerably increase their reuse, resulting in high adsorptive capacity [30]. Additionally, the same behavior is observed for magnetic NCs as nanocatalysts. Using magnetic nanocatalysts allows the reuse of the material, increasing the cost-effectiveness and avoiding subsequent steps such as filtration and centrifugation [31].

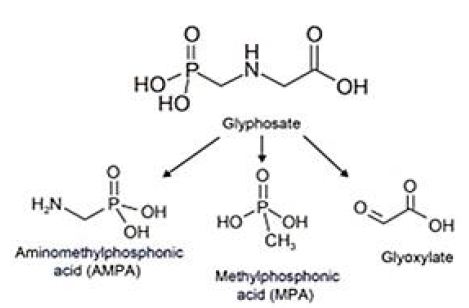

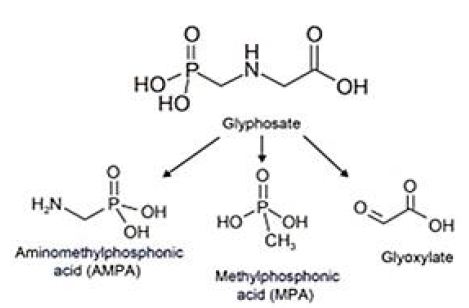

Glyphosate {N-phosphomethyl[glycine] or (C3H8NO5P)}, is an organophosphorus compound with herbicide properties discovered in 1970. It is a competitive inhibitor of the 5-enolpyruvylshikimate-3-phosphate synthase, an enzyme involved in aromatic amino acid biosynthesis in plants and microorganisms [32]. Glyphosate is now the most used herbicide globally, and its usage keeps increasing with the emergence of weed resistance, from 16 million kg spread in the world in 1994 to 79 million kg spread in 2014, including 15% in the United States alone [33]. Once in the environment, glyphosate is metabolized by microorganisms into aminomethylphosphonic acid (AMPA; known as its most active metabolite) and methylphosphonic acid (MPA) (Figure 1) [34]. Glyphosate and its metabolite AMPA can be found in soils, water, plants, food, and animals [35-37]. Glyphosate is detected in human urine, blood, and maternal milk, with urinary levels of 0.26-73.5 μg/l in exposed workers and 0.16-7.6 μg/l in the general population [38,39]. Glyphosate most likely enters the body via the dermal, oral and pulmonary routes [40]. Even if the dermal route allows a poor absorption (≈2%), it is the main reported route of entry in exposed farmers [41]. Glyphosate then seems to accumulate principally in the kidneys, liver, colon, and small intestine and is eliminated in the feces (90%) and urine within 48 h. Because of this omnipresence, its safety is of grave concern. Glyphosate has long been regarded as harmless allegedly because it targets an enzyme inexistent in animals, is supposedly degraded into CO2, and its formulation contains misleadingly-called “inert” ingredients. Nevertheless, there is growing literature that describes the risks for glyphosate and glyphosate-based herbicides on human health [42]. After more than 40 years of global use, glyphosate has been classified as “probably carcinogenic” in humans by the International Agency for Research on Cancer (IARC). In March 2015, the World Health Organization’s IARC classified three organophosphates (glyphosate, malathion, and diazinon) as “probably carcinogenic for humans” (Category 2A) [43]. In contrast, in November 2015 the European Food Safety Agency determined glyphosate was “unlikely to pose a cancer risk for man” [44]. In 2018 the European Chemicals Agency, Risk Assessment Committee concluded that “the scientific evidence so far available does not satisfy the criteria for classifying glyphosate as carcinogenic, mutagenic or toxic for reproduction” [45]. In 2019, US federal health agency, the Agency for Toxic Substances and Disease Registry (ATSDR) [46], part of the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention [47], determined that both cancer and non-cancer hazards derive from exposure to glyphosate and glyphosate-based herbicides.

Figure 1: Glyphosate and main glyphosate by-products; aminomethylphosphonic acid (AMPA), methylphosphonic acid (MPA) and glyoxylate, respectively.

In modern agriculture, especially in most intensive and large-scale crops, herbicides are used to eliminate weeds. Glyphosate is a non-selective, highly effective, broad-spectrum, and low toxicity herbicide, whose usage increases exponentially for the effective in eliminating weeds indiscriminately [48]. In recent years, the long half-life of glyphosate and its main metabolite AMPA causes the existence in the environment. The potential impact of glyphosate in the environment is an increasing concern around the world. In the recent past, a significant increase in the use of the glyphosate herbicide has been noticed which further increased after the introduction of glyphosate-tolerant crops [49,50]. According to a report, The United States saw a 14 times increase in glyphosate use between 1992 and 2015, where the majority was applied to soybean and corn crops [51]. Being a nonselective, mutagenic, and carcinogenic herbicide, their presence in atmosphere can cause severe health and environmental issues [52]. As a result, it poses a high environmental risk and requires prompt studies towards its elimination.

In recent years, photocatalytic studies have explored the fabrication of ternary heterojunctions as a preferred scientific and practical method to improve the migration of photogenerated charge carriers [53]. Towards this end, ternary type II heterojunctions have shown significant success with accelerated charge carrier production [54]. However, the repulsion between the photogenerated electrons and the formation of weaker redox potentials limit its photocatalytic activity [55]. Therefore, another promising photosystem known as a Z-scheme heterojunction was developed to overcome the aforementioned issues [56]. In the case of Z-scheme photosystems, the conduction band electrons with a lower energy of one semiconductor migrate towards the valence band holes with a higher energy of other semiconductors. This combination leads to the formation of highly reductive electrons as well as highly oxidative holes [57]. Additionally, Z-scheme photo-systems not only enhance the charge separation efficiency of semiconductor photocatalysts but also possess electrons and holes with strong redox potential for superior photocatalytic applications. Moreover, ternary heterojunctions with a double electron transfer Z-scheme have photogenerated charge carriers with a prolonged lifetime compared to binary systems which improves the scope of light-harvesting [58]. Some recent ternary heterojunctions with double electron transfer Z-scheme channelization are g-C3N4/ZnO/ZnWO4, polyaniline-BiOBr-GO, g-C3N4/Zn2SnO4N/ZnO [59-61].

The fabrication of NCs in ionic liquid (IL) media can provide a better scaling up approach for microscopic dispersion of particles and close interface contact between the individual components [62]. ILs as synthetic media provide unique advantages like negligible vapor pressure, thermal stability, and better conductivity than NCs. Additionally, the effect of “cation-π” and “π-π” interactions due to the presence of ionic liquids improve the nanoparticles (NPs) dispersion and stabilization which boosts the surface to volume ratio of NCs [63]. Recently, ionic liquids have been also employed for extensive polymerization and catalysis applications. Pahonik et al. [64] verified the oxidative polymerization of aniline with ammonium persulphate and the IL 1-butyl-3-methylimidazolium chloride (BMIMCl) under acidic conditions. More interestingly, IL-assisted NCs synthesis processes are relatively rapid, facile, greener, and more efficient without the requirement of any foreign stabilizer and surfactants [65]. The development of nanostructures and NCs with a simplified and greener IL-assisted in situ oxidative polymerization method is highly preferable method for photocatalytic degradation process of environmental pollutants.

Polyaniline (PANI) is a conducting polymer and organic semiconductor of the semi-flexible rod polymer family. PANI is one of the most studied conducting polymers [66,67]. To fabricate a ternary heterojunction, PANI can serve as the third active component of the photosystem. PANI has high demand as a low-cost and environment-friendly conjugated semiconductor for the fabrication of visible light harvesting photocatalysts [68]. It is a conducting polymer with an extensive conjugated π-system and high absorption coefficient towards visible light mediated charge carrier production. Furthermore, advantages like simple processing and high conductivity make it an emerging material for the synthesis of heterojunction materials. Recently, many efforts have been made to maximize the photo-harvesting efficiency of PANI-based composite materials. Researchers explored many positive hybrid effects arising from such systems due to the close contact of the interfaces of individual components leading to high separation efficiency of photogenerated electron-hole pairs [69].

The two-dimensional (2D) g-C3N4 semiconductor has a wide range of applications in the environmental and energy fields because of its visible-light activity, unique physicochemical properties, excellent chemical stability and low-cost [70,71]. Some important limitations of the photocatalytic activity of g-C3N4 are its low specific surface area, fast recombination of electrons and holes and poor visible light absorption [72-74]. To improve the above problems, the construction of a heterojunction with a suitable band gap semiconductor (co-catalyst) has been shown to be a good strategy to improve the photocatalytic performance of g-C3N4, such as g-C3N4-based conventional type II heterostructures, g-C3N4-based Z-scheme heterostructures, and g-C3N4-based p-n heterostructures, etc. The unique “Z” shape as the transport pathway of photogenerated charge carriers in Z-scheme photocatalytic systems is the most similar system to mimic natural photosynthesis in the many g-C3N4-based heterojunction photocatalysts. The construction of Z-scheme photocatalytic systems can promote visible light utilization and carrier separation, and maintain the strong reducibility and oxidizability of semiconductors [75-78]. There are many studies on g-C3N4-based Z-scheme heterojunction photocatalysts, such as ZnO/g-C3N4 [79-82], WO3/g-C3N4 [83], g-C3N4/ZnS, g-C3N4/NiFe2O4 [84], g-C3N4/graphene/NiFe2O4 [85], NiCo/ZnO/g-C3N4 [86] and Bi2Zr2O7/g-C3N4/Ag3PO4 [87], respectively. g-C3N4-based Z-scheme heterojunction photocatalysts have been made to improve the photocatalytic activity by combining with other semiconductor materials. Therefore, there are some problems with the single photocatalytic method, such as low adsorption ability, limited active sites and low removal efficiency. The integration of the adsorption and photocatalytic degradation of various organic pollutants is considered as a suitable and promising technology. On the other hand, it is still essential to fabricate photocatalysts with superior adsorption and degradation efficiencies.

g-C3N4 has been gaining great attention as a potential photocatalyst due to its stability and safety characteristics, as well as the fact that it can be facilely synthesized from low-cost raw materials. The low bandgap (~2.7 eV) can drive photo-oxidation reactions even under visible light [88-90]. However, the pure g-C3N4 has some drawbacks such as its low redox potential and high rate of recombination between photo-induced electrons and holes, which dramatically limits its photocatalytic efficiency. Several strategies have been investigated, including modification of the material’s size and structure [91], nonmetal and metal doping [92,93], and coupling with other photocatalysts [94-97]. For example, Liu et al. improved bulk g-C3N4’s performance in terms of Rhodamine B degradation from 30% to 100% by synthesizing mesoporous g-C3N4 nanorods through the nano-confined thermal condensation method. Dai et al. doped g-C3N4 with Cu through a thermal polymerization route and acquired a degradation rate of 90.5% with norfloxacin antibiotic. Nithya and Ayyappan, synthesized hybridized g-C3N4/ZnBi2O4 for reduction of 4-nitrophenol and reached an optimal removal efficiency of 79%. Among all, the construction of heterostructure photocatalysts by coupling g-C3N4 with other semiconductors seems to be an effective strategy to prevent electron and hole recombination, hence improving photocatalytic efficiency for contaminant treatment.

Zinc tungsten oxide or zinc tungstate (ZnWO4) has received wide attention owing to its high ultraviolet (UV) light response, tunable band edges, optical transparency, easy availability, chemical stability, and adequate strength [98]. The band edge tunning of ZnWO4-centered nanostructures can be organized through appropriate changes such as heterostructure construction, doped/combining with transition metal ions, and noble metals [99,100]. The alteration of electronic environment in ZnWO4 nanomaterials through such engineered modifications can lead to interesting catalytic properties. The relationship between their structures and properties should therefore be considered to progress extremely proficient solar light conserving photocatalysts for the removal of toxic contaminants [101]. In the case of heterogeneous photocatalysis such as ZnWO4, solid catalysts/semiconductors are utilized to remove organic pollutants under light irradiation due to redox reactions in photogenerated charge carriers. The mechanism is divided into three significant steps, generation of charge carrier pairs under irradiation, photogenerated charge carriers migrating on the surface of the catalyst, and initiation of the redox reaction by oxidative (OH●) and superoxide (O2– ●) radicals [102]. For instance, Alshehri et al. [103] investigated that ZnWO4 was used as a photocatalyst to degrade MB dye, and they reported the formation of OH● and O2– ● free radicals oxidized the dye molecules to form inorganic minerals. The organic molecules by the photogenerated electron holes can also occur while hydroperoxyl radicals (OOH●) and H2O2 are produced by the subsequent reactions, which occur between O2– ● and H+. This heterogeneous photocatalytic process induces the mineralization of organic pollutants (CO2 and H2O). Depending on the process’s efficiency, the pollutant’s composition, and its structure, additional products such as acids and salts can be formed. Exploration into photocatalysis has shown how UV-light, visible light, and solar irradiation can be utilized effectively to reduce environmental pollution [104,105]. Electron-hole pairs are produced when photon energy more prominent than the band gap of the semiconductor used to illuminate the semiconductor; this then leads to the formation of electron-hole pairs. OH● when the generated electrons and holes react with H2O and molecular oxygen on the surface of the crystal. With oxygen ions deposited around the tungsten, ZnWO4 forms an insulated [WO6] octahedron coordination with an asymmetric shape showing its local atomic structures with a monoclinic wolframite-type structure with the space group P2/c [106]. This is an essential inorganic ternary oxide material as it has been known to crystallize as a scheelite structure depending on the ionic radius [107]. However, W clusters form a network because they are more stable, which leads to forming the covalent nature of W-O bonds. In forming electron-hole pairs associated with a charge separation process and dipoles, the WO6 clusters act as electron receptors. Thus, the oxygen vacancies in the Zn/W clusters can transfer electrons to the tungsten cluster and thus form permanent dipoles [108]. The Zn and W vacancies act as hole traps because they are negatively charged [109]. During the UV irradiation of ZnWO4, the conduction band electrons generated are transferred to Ag nanocrystallite due to the Schottky barrier at Ag/ZnWO4, which aid the charge carrier separation [110,111]. Different researchers have provided detailed and in-depth information, including improving ZnWO4 as the next-generation catalysts for wastewater treatment. For instance, Gouveia et al. demonstrated that the overall performance of ZnWO4 NPs was linked to the exposed surfaces of materials, their functional properties, and morphological structures; however, the authors failed to explain the concept of binary and multiple doping effects of ZnWO4. According to the first-principle approach, the photocatalytic activity of ZnWO4 depends on the intrinsic atomic properties and the electronic structure of the incomplete surface clusters of the exposed surfaces of the morphology. The authors found that the surface clusters in the morphology controlled the intrinsic atomic properties of the metal oxide in question. Furthermore, Geetha et al. [112] prepared ZnWO4 nanoparticles via the co-precipitation method for the photocatalytic degradation of methylene blue (MB). The highest dye removal (81%) was observed for ZnWO4 NPs prepared with 30 cm3 distilled water. Also, the performance of ZnWO4 depended on the volume of the solvent (30-90 ml) and band gap energy (3.19 eV-3.16 eV), which was evidence of reduced interaction between metal and oxygen orbital. The members of the tungstate family have, over the years, been used for the mineralization of organic pollutants under UV [113] and sunlight [114] irradiation. However, the photocatalytic strength of ZnWO4 stand-alone is not strong enough (Rahmani and Sedaghat, 2019). The enhancement of the photocatalytic activity of semiconductor ZnWO4 for practical applications has deeply been considered for the degradation of contaminants. This has been the goal of many industries and scientists interested in environmental pollution control. However, a couple of approaches have been reported to further increase the properties of ZnWO4 NPs for wastewater treatment.

In this study, a novel PANI/g-C3N4/ZnWO4 ternary NCs as a heterostructure photocatalys was examined during photocatalytic degradation process in the efficient removal of glyphosate herbicide from a aqueous solution. Different pH values (3.0, 5.0, 7.0, 9.0 and 11.0), increasing glyphosate concentrations (5 mg/l, 10 mg/l, 15 mg/l and 20 mg/l), increasing PANI/g-C3N4/ZnWO4 ternary NCs concentrations (5 mg/l, 15 mg/l, 30 mg/l and 45 mg/l) and increasing recycle times (1., 2., 3., 4., 5., 6. and 7.) was operated during photocatalytic degradation process in the efficient removal of glyphosate in a aqueous solution. The characteristics of the synthesized NPs were assessed using XRD, FESEM, EDX, FTIR, TEM, DRS and XPS analyses, respectively. The cyctotoxicity test was operated to the standard TBE (trypan blue dye exclusion) assay technique with Drosophila melanogaster (fruit fly). ANOVA statistical analysis was used for all experimental samples.

Materıals and Methods

Preparation of Graphitic Carbon Nitride (g-C3N4) Nanoparticles

g-C3N4 nanoparticles (NPs) was prepared by calcination of melamine (C3H6N6) in a crucible with a lid at 550°C for 4 h. The obtained yellow powder was ground in an agate mortar after being cooled down to 25°C room temperature.

Preparation of Zinc Tungstate (ZnWO4) Nanoparticles

ZnWO4 NPs was prepared to sol-gel methods. Sol-gel method also called chemical solution deposition; it entails hydrolysis and polycondensation, gelation, aging, drying, densification, and crystallization. It is a highly effective method for synthesizing ZnWO4 NPs with modified surfaces. Grossin [115] describe this method as involving the hydrolysis of the precursor in acidic or basic mediums and the polycondensation of the hydrolyzed. Rahmani and Sedaghat studied the nature of the ZnWO4 NPs obtained from this study. The ZnWO4 NPs were synthesized by adding 30 ml ethanol and 3 ml HCl into a mixture of zinc acetate dropwise, while sodium tungstate in deionized water was added to 20 ml of ethanol in a dropwise form. Both solutions were mixed vigorously, after which urea was added to the zinc acetate and sodium tungstate mixture. The ZnWO4 NPs synthesized were characterized as well, where it was observed that the band gap energy was 3.20 eV. The ZnWO4 NPs synthesized had an average diameter of between 26-78 nm.

Preparation of A Novel PANI/g-C3N4/ZnWO4) (PGZ) Ternary Nanocomposites (NCs)

The novel PANI/g-C3N4/ZnWO4) (PGZ) ternary NCs was synthesized by adopting an ionic liquid-assisted in situ oxidative polymerization process. The process includes the 1-butyl-3-methylimidazolium chloride-assisted polymerization of aniline using (NH4)2S2O8 as an oxidant. Firstly, 0.5 ml, 1.0 ml and 2.0 ml of aniline was added to an aqueous solution of 1-butyl-3-methylimidazolium chloride to make three different PANI solutions. Afterward, to each PANI mixture, an appropriate amount of (NH4)2S2O8 was added in a (NH4)2S2O8 /aniline=1/1 molar ratio. In two other round bottom flasks, 0.20 g g-C3N4 and 0.20 g ZnWO4 were dispersed in 30 ml of 0.10 M HCl solution under ultra-sonication for 30 min. Subsequently, the particle mixtures were poured into the previously prepared PANI mixtures. The polymerization process was maintained for 12 h under mechanical stirring at 25°C room temperature. The products were separated by centrifugation and washed multiple times with ethanol to remove the residual IL media. The three composite mixtures obtained were dried in a vacuum oven at 70°C. The prepared samples are marked as xPGZ (0.5-PGZ, 1-PGZ, and 2-PGZ), where x denotes the amount of aniline added. For simplicity, sample 1-PGZ is referred to as PGZ throughout this study.

Photocatalytic Degradation Reactor

A 2 liter cylinder quartz glass reactor was used for the photodegradation experiments in the glyphosate aqueous solution at different operational conditions. 1000 ml glyphosate aqueous solution was filled for experimental studies and the photocatalyst were added to the cylinder quartz glass reactors. The UV-A lamps were placed to the outside of the photo-reactor with a distance of 3 mm. The photocatalytic reactor was operated with constant stirring (1.5 rpm) during the photocatalytic degradation process. 10 ml of the reacting solution were sampled and centrifugated (at 10000 rpm) at different time intervals. The UV irradiation treatments were created using one or three UV-A lamp emitting in the 350-400 nm range (λmax=368 nm; FWHM=17 nm; Actinic BL TL-D 18W, Philips). Three 50 W UV-A lamps (Total: 150 W UV-A lamps) were used during experimental conditions for this study.

Glyphosate Photocatalytic Degradation Experiments

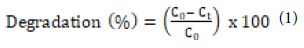

The photocatalytic degradation efficiencies of PANI, g-C3N4 NCs, ZnWO4 NCs and PANI/g-C3N4/ZnWO4 ternary NCs were investigated with a cylinder quartz glass photocatalytic reactor under UV-vis light irradiation. The series of glyphosate degradation studies were performed in an aqueous solution. The temperature of the photocatalytic system was maintained using continuously circulating aqueous solution. Typically, 25 mg/l catalysts were used for the batch degradation study with 100 ml of 10 mg/l glyphosate under continuous magnetic stirring. The pH=7.0 ± 0.1 of the pollutant solutions was maintained throughout the degradation process by adding H2SO4 and NaOH solutions as necessary. Initially, the reaction mixtures were kept in dark to check the adsorption properties of glyphosate and to attain adsorption-desorption equilibrium. Next, the whole setup was exposed to UV-vis light for the photocatalytic degradation study. In 20 min time gap, a 4 ml aliquot of the pollutant solution was withdrawn and centrifuged to separate the NCs. The initial and final concentration supernatants were analyzed using a UV-vis spectrometer for detection of the intermediates and degradation products formed during the photocatalytic degradation process. The percentage degradation was calculated by the following Equation (1):

Determination of Glyphosate and Photodegradation by-Products

The quantification of glyphosate and glyphosate major photodegradation products was determined to a Gas Chromatography-Mass Spectrometry (GC-MS). These samples were performed with a gas chromatographya gas chromatographically (Agilent 6890N GC) equipped with a mass selective detector (Agilent 5973 inert MSD) (GC-MS) (Hewlett-Packard 6980/HP5973MSD). A capillary column (HP5-MS, 30 m, 0.25 mm, 0.25 m) was used. The initial oven temperature was kept at 50°C for 1 min, then raised to 200°C at 25°C/min and from 200°C to 300°C at 8°C/min, and then maintained for 5.5 min. High purity He(g) was used as the carrier gas at constant flow mode (1.5 ml/min, 45 cm/s linear velocity). The method involves the addition of 5% borate buffer to the aqueous sample to adjust the pH=9.0 and then mixing with 9-fluorenylmethyl chloroformate (FMOC) in acetonitrile prior to analysis. The derivatization process was continued for 16 h at 25°C and the process was stopped by drop-wise addition of 6 M HCl solution where the resulting pH was measured to be pH=1.5. Chromatographic separation was performed with a C18 column where the mobile phase was 5 mM HAc/NH4Ac (pH=4.8) acetonitrile. The acetonitrile percentage was changed from 75% (0-42 min) to 100% (42.1-45 min) to 5% (45.1-50 min). For each sample separation process was completed in 50 min. The degradation products were detected at 210 nm with a PDA detector. The same method was also applied for derivatization and analysis of glyphosate and glyphosate by-products; acetate, aminomethylphosphonic acid (AMPA), phosphate, sarcosine and glycine as standards.

Quantification of Major Oxygen Species

To quantify the reactive oxygen species (OH● and O2– ●) production under light illumination, 1.2 g/l benzoic acid and 5×10−5 mol/l nitro blue tetrazolium dichloride (NBT) solutions were considered as molecular probes, respectively. 100 mg of PANI/g-C3N4/ZnWO4 ternary NCs was dispersed in 100 ml of the molecular probe solutions to evaluate the radical production efficiency. For every 10 min, 3 ml of sample was pipetted out for further analysis. The NBT sample was analyzed with a UV spectrometer (Shimadzu 2450) at 258 nm. The quantification of O2– ● was done by the NBT degradation method. The quantity of OH● was measured by analyzing the amount of p-hydroxybenzoic acid in the sample with the same GC-MS method mentioned above. In this case, the mobile phase was acetonitrile/water (30/70) with a 1 ml/min flow rate.

Characterization

X-Ray Diffraction Analysis

Powder XRD patterns were recorded on a Shimadzu XRD-7000, Japan diffractometer using Cu Kα radiation (λ=1.5418 Å, 40 kV, 40 mA) at a scanning speed of 1°/min in the 10-80° 2θ range. Raman spectrum was collected with a Horiba Jobin Yvon-Labram HR UV-Visible NIR (200-1600 nm) Raman microscope spectrometer, using a laser with the wavelength of 512 nm. The spectrum was collected from 10 scans at a resolution of 2 /cm. The zeta potential was measured with a SurPASS Electrokinetic Analyzer (Austria) with a clamping cell at 300 mbar.

Field Emission Scanning Electron Microscopy (FESEM) and Energy Dispersive X-Ray (EDX) Spectroscopy Analysis

The morphological features and structure of the synthesized catalyst were investigated by FESEM (FESEM, Hitachi S-4700), equipped with an EDX spectrometry device (TESCAN Co., Model III MIRA) to investigate the composition of the elements present in the synthesized catalyst.

Fourier Transform Infrared Spectroscopy (FTIR) Analysis

The FTIR spectra of samples was recorded using the FT-NIR spectroscope (RAYLEIGH, WQF-510).

Transmission Electron Microscopy (TEM) Analysis

The structure of the samples were analysed TEM analysis. TEM analysis was recorded in a JEOL JEM 2100F, Japan under 200 kV accelerating voltage. Samples were prepared by applying one drop of the suspended material in ethanol onto a carbon-coated copper TEM grid, and allowing them to dry at 25°C room temperature.

Diffuse Reflectance UV-Vis Spectra (DRS) Analysis

DRS Analysis in the range of 200-800 nm were recorded on a Cary 5000 UV-Vis Spectrophotometer from Varian. DRS was used to monitor the glyphosate concentration in experimental samples.

X-Ray Photoelectron Spectroscopy (XPS) Analysis

The valence state of the biogenic palladium nanoparticles was investigated and was analyzed using XPS (ESCALAB 250Xi, England). XPS used an Al Ka source and surface chemical composition and reduction state analyses was done, with the core levels recorded using a pass energy of 30 eV (resolution ≈0.10 eV). The peak fitting of the individual core-levels was done using XPS-peak 41 software, achieving better fitting and component identification. All binding energies were calibrated to the C 1s peak originating from C-H or C-C groups at 284.6 eV.

Cytotoxicity Test

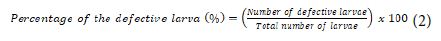

The standard TBE (trypan blue dye exclusion) assay technique was followed for to check the cytotoxicity of the photo-treated glyphosate solution and photocatalyst. Drosophila melanogaster (fruit fly) was considered as a model organism since 75% of its disease genome sequence is functionally homologous to that of humans [116]. Similar studies were also reported where Drosophila melanogaster was employed as a model research organism to study the toxic effects of various chemicals, drugs, medicines and NPs. The TBE assay has been studied for differentiating live and dead cells in the Drosophila melanogaster larval gut. Before the cytotoxicity study, glyphosate samples (untreated, 5 mg/l, 10 mg/l, 15 mg/l and 20 mg/l) were prepared. And, to analyze the cytotoxic effects of both the initial glyphosate solution and phototreated products, the TBE assay was implemented. Firstly, third instar larvae were taken and washed with 1× PBS to remove food particles that remained in the larval body. Then, the larvae were transferred to a Petri plate with 2% solidified agar to keep them hungry. After that, 10 3rd instar larvae were transferred to 1.5 ml eppendorf tubes each containing 500 μl of the glyphosate solutions, respectively. These larvae were kept for 30 min to feed on the chemical orally. After the incubation, the larvae were washed once with 1× PBS. Then, the larvae were transferred into a container with 0.5% TBE solution and kept for 45 min in a dark atmosphere at 25°C room temperature. After incubation, again the excess strain was washed twice with 1× PBS for 10 min each [117]. Then, further analysis was done with a USB stereomicroscope and digital images were taken to check any abnormality in the gut. A similar procedure was followed for different amounts of the PANI/g-C3N4/ZnWO4 ternary NCs samples (5 mg, 15 mg, 30 mg and 45 mg). Finally, the percentage of the defective Drosophila melanogaster larva is calculated as following Equation (2):

Statistical Analysis

ANOVA analysis of variance between experimental data was performed to detect F and P values. The ANOVA test was used to test the differences between dependent and independent groups [118]. Comparison between the actual variation of the experimental data averages and standard deviation is expressed in terms of F ratio. F is equal (found variation of the date averages/expected variation of the date averages). P reports the significance level, and d.f indicates the number of degrees of freedom. Regression analysis was applied to the experimental data in order to determine the regression coefficient R2 [119]. The aforementioned test was performed using Microsoft Excel Program.

All experiments were carried out three times and the results are given as the means of triplicate samplings. The data relevant to the individual pollutant parameters are given as the mean with standard deviation (SD) values.

Results and Discussions

A Novel PANI/g-C3N4/ZnWO4 Ternary NCs Characteristics

The Results of X-Ray Diffraction (XRD) Analysis

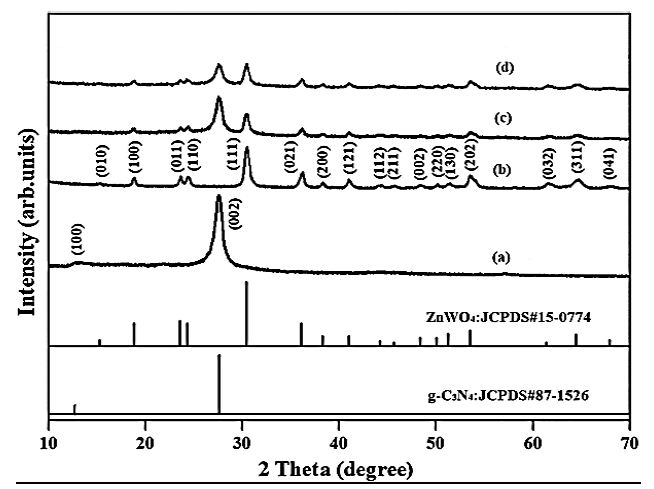

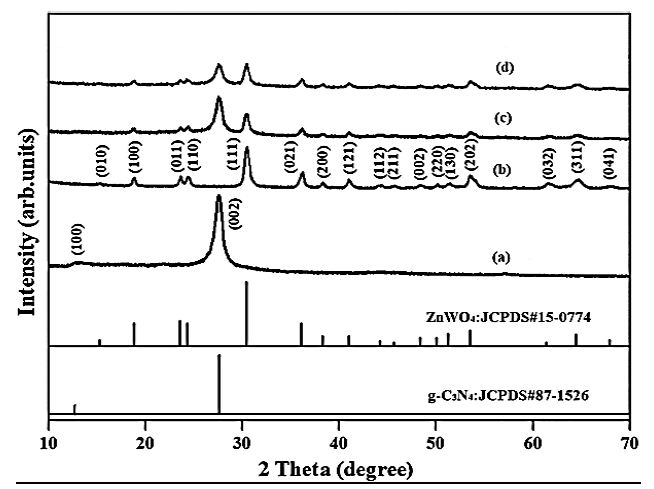

The results of XRD analysis was observed to pure g-C3N4 NPs, pure ZnWO4 NPs, pure PANI and PANI/g-C3N4/ZnWO4 ternary NCs, respectively, in aqueos solution with photocatalytic degradation process for glyphosate removal (Figure 2). The characterization peaks were observed at 2θ values of 12.71° and 28.84°, respectively, corresponding to the (100) and (002) planes of implying pure g-C3N4 NPs in aqueous solution with photocatalytic degradation process for glyphosate removal (Figure 2a). The characterization peaks were obtained at 2θ values of 17.10°, 19.52°, 14.70°, 15.01°, 30.17°, 37.28°, 39.11°, 42.34°, 44.41°, 46.53°, 49.20°, 50.65°, 53.42°, 54.41°, 61.36°, 65.22°, and 68.74°, respectively, corresponding to the (010), (100), (011), (110), (111), (021), (200), (121), (112), (211), (002), (220), (130), (202), (032), (311) and (041), respectively, implying pure ZnWO4 NPs in aqueous solution with photocatalytic degradation process for glyphosate removal (Figure 2b). The characterization peaks were found at 2θ values of 18.27°, 24.32°, 26.11°, 28.44°, 30.10°, 37.22°, 41.34°, 53.28°, 61.34° and 64.42°, respectively, corresponding to (100), (011), (110), (002), (111), (021), (200), (121), (202), (032) and (311), respectively, implying PANI in aqueous solution with photocatalytic degradation process for glyphosate removal (Figure 2c). The characterization peaks were observed at 2θ values of 28.39°, 30.17°, 37.63°, 41.20°, 54.33°, 61.20° and 64.60°, respectively, corresponding to (002), (111), (021), (121), (202), (033) and (312), respectively, implying PANI in aqueous solution with photocatalytic degradation process for glyphosate removal (Figure 2d).

Figure 2: The XRD patterns of (a) pure g-C3N4 NPs, (b) pure ZnWO4 NPs, (c) PANI and (d) PANI/g-C3N4/ZnWO4 ternary NCs, respectively, in aqueous solution with photocatalytic degradation process for glyphosate removal.

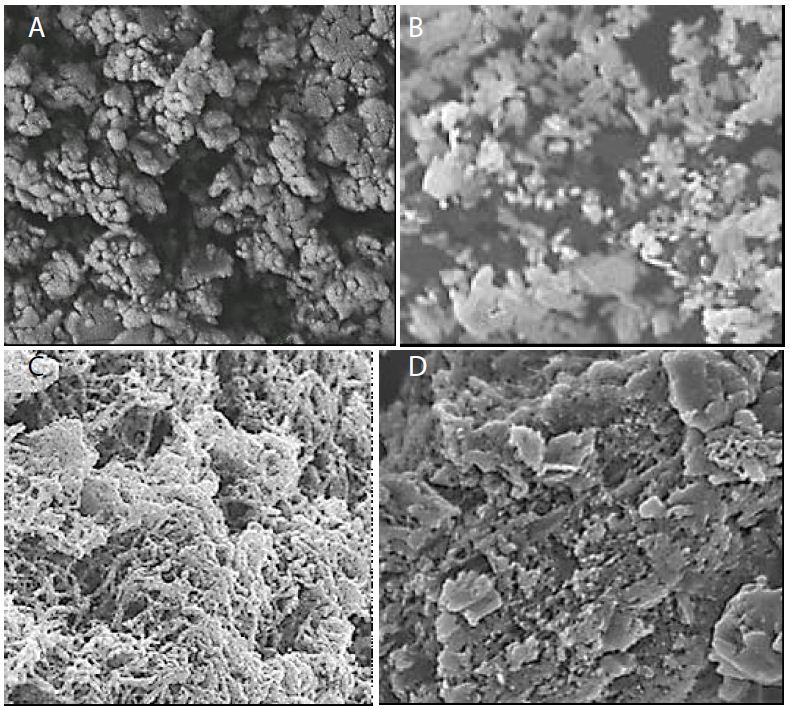

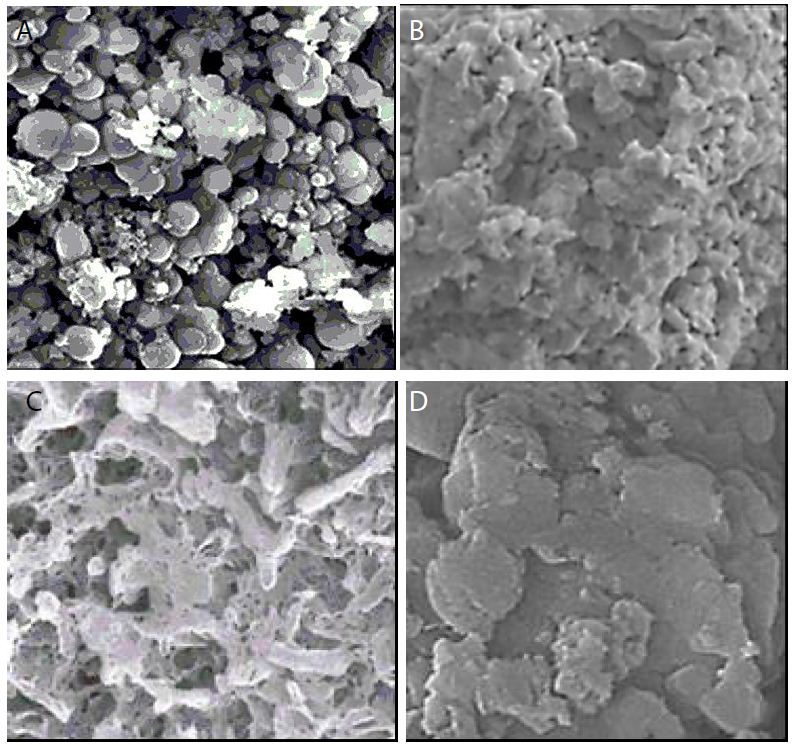

The Results of Field Emission Scanning Electron Microscopy (FESEM) Analysis

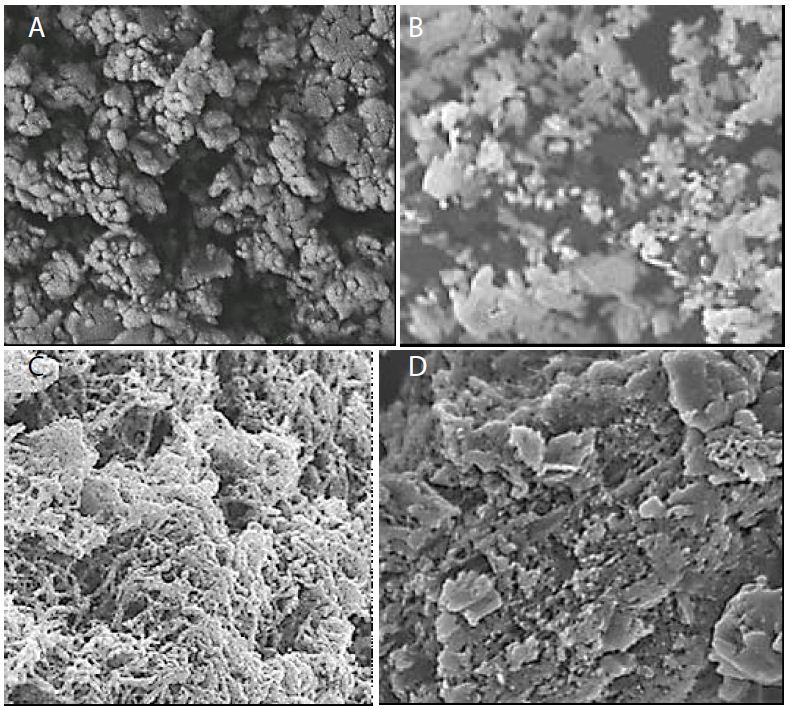

The morphological features of pure g-C3N4 NPs, pure ZnWO4 NPs, PANI and PANI/g-C3N4/ZnWO4 ternary NCs were characterized through FE-SEM images (Figure 3). The FESEM images of pure g-C3N4 NPs were obtained in aqueous solution with photocatalytic degradation process for glyphosate removal (Figure 3a). The FESEM images of pure ZnWO4 NPs were observed in aqueous solution with photocatalytic degradation process for glyphosate removal (Figure 3b). The FESEM images of PANI were viewed in aqueous solution with photocatalytic degradation process for glyphosate removal (Figure 3c). The FESEM images of PANI/g-C3N4/ZnWO4 ternary NCs were characterized in aqueous solution with photocatalytic degradation process for glyphosate removal (Figure 3d).

Figure 3: FESEM images of (a) pure g-C3N4 NPs, (b) pure ZnWO4 NPs, (c) PANI and (d) PANI/g-C3N4/ZnWO4 NCs, respectively, in aqueous solution with photocatalytic degradation process for glyphosate removal.

The Results of Energy Dispersive X-Ray (EDX) Spectroscopy Analysis

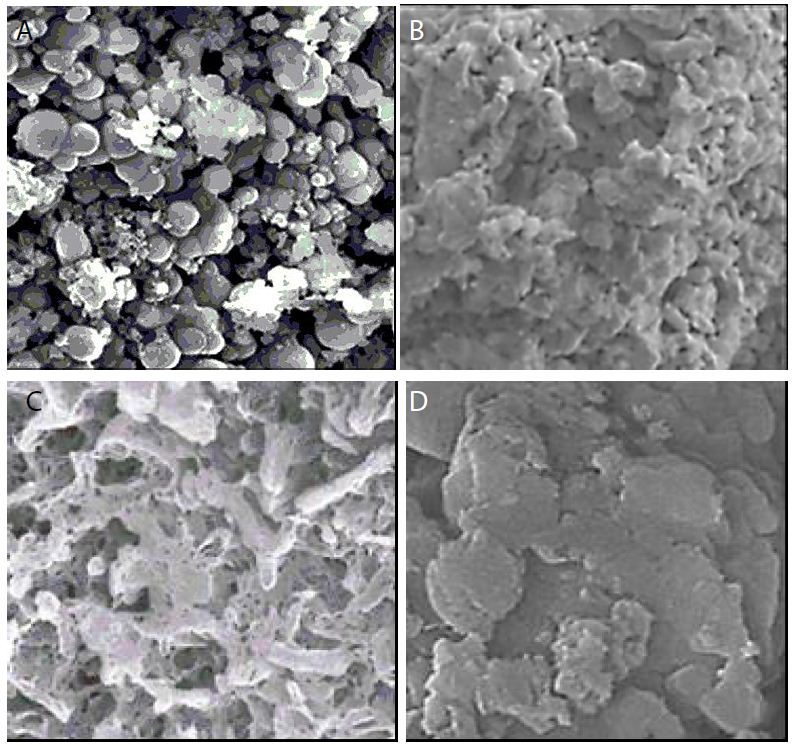

The EDX analysis was also performed to investigate the composition of pure g-C3N4 NPs (Figure 4a), pure ZnWO4 NPs (Figure 4b), PANI (Figure 4c) and PANI/g-C3N4/ZnWO4 NCs (Figure 4d), respectively, in aqueous solution with photocatalytic degradation process for glyphosate removal.

Figure 4: EDX images of (a) pure g-C3N4 NPs, (b) pure ZnWO4 NPs, (c) PANI and (d) PANI/g-C3N4/ZnWO4 ternary NCs, respectively, in aqueous solution with photocatalytic degradation process for glyphosate removal.

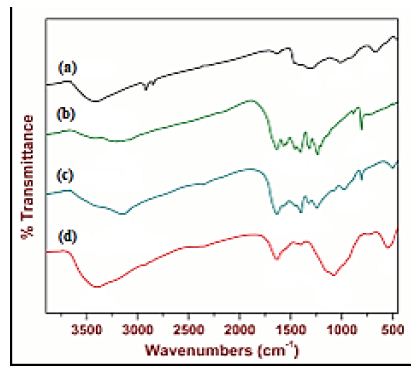

The Results of Fourier Transform Infrared Spectroscopy (FTIR) Analysis

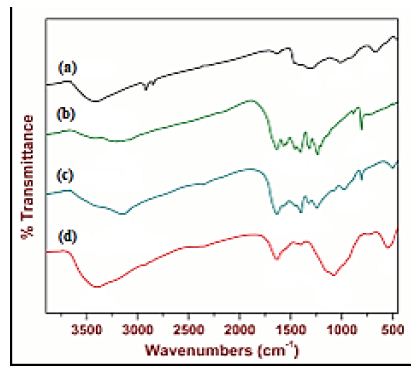

The FTIR spectrum of pure g-C3N4 NPs, pure ZnWO4 NPs, PANI and PANI/g-C3N4/ZnWO4 ternary NCs, respectively, were determined in aqueous solution with photocatalytic degradation process for glyphosate removal (Figure 5). The main peaks of FTIR spectrum for pure ZnWO4 NPs (black spectrum) was observed at 3421 1/cm, 1326 1/cm, 1015 1/cm and 678 1/cm wavenumber, respectively (Figure 5a). The main peaks of FTIR spectrum for pure g-C3N4 NPs (green spectrum) was obtained at 3348 1/cm, 1645 1/cm, 1410 1/cm, 1234 1/cm and 807 1/cm wavenumber, respectively (Figure 5b). The main peaks of FTIR spectrum for PANI (blue spectrum) was determined at 3151 1/cm, 1544 1/cm, 1408 1/cm, 1239 1/cm, 900 1/cm and 815 1/cm wavenumber, respectively (Figure 5c). The main peaks of FTIR spectrum for PANI/g-C3N4/ZnWO4 ternary NCs (red spectrum) was obtained at 3416 1/cm, 1638 1/cm, 1074 1/cm and 549 1/cm wavenumber, respectively (Figure 5d).

Figure 5: FTIR spectrum of (a) pure ZnWO4 (black spectrum), (b) g-C3N4 NPs (green spectrum), (c) PANI (blue spectrum) and (d) PANI/g-C3N4/ZnWO4 ternary NCs (red spectrum), respectively, in aqueous solution with photocatalytic degradation process for glyphosate removal.

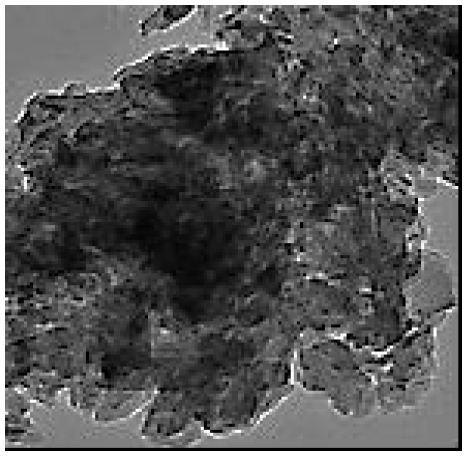

The Results of Transmission Electron Microscopy (TEM) Analysis

The TEM images of PANI/g-C3N4/ZnWO4 ternary NCs was observed in micromorphological structure level in aqueous solution with photocatalytic degradation process for glyphosate removal (Figure 6).

Figure 6: TEM images of PANI/g-C3N4/ZnWO4 ternary NCs in micromorphological structure level in aqueous solution with photocatalytic degradation process for glyphosate removal.

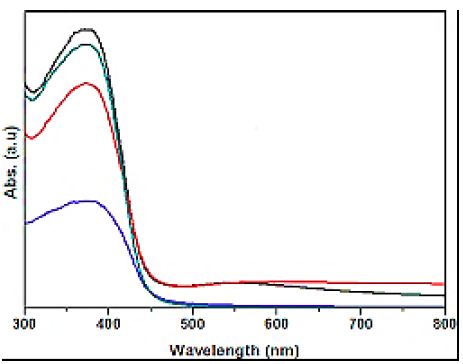

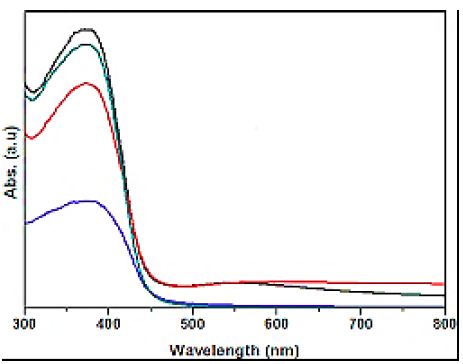

The Results of Diffuse reflectance UV-Vis Spectra (DRS) Analysis

The absorption spectra of glyphosate was observed in DRS Analysis (Figure 7). First, the absorption spectra of glyphosate were obtained at a maximum concentration of 15 mg/l in the wavelength range from 300 nm to 800 nm using diffuse reflectance UV-Vis spectra (Figure 7). Absorption peaks were observed at wavelengths of 375 nm for pure g-C3N4 NPs (red pattern) (Figure 7a), 390 nm for pure ZnWO4 NPs (blue pattern) (Figure 7b), 370 nm for PANI (green patern) (Figure 7c) and 430 nm for PANI/g-C3N4/ZnWO4 NCs (black pattern) (Figure 7d), respectively, in aqueous solution with photocatalytic degradation process for glyphosate removal.

Figure 7: The DRS patterns of (a) pure g-C3N4 NPs (red pattern) (b) pure ZnWO4 NPs (blue pattern), (c) PANI (green pattern) and (d) PANI/g-C3N4/ZnWO4 NCs (black pattern), respectively, in aqueous solution with photocatalytic degradation process for glyphosate removal.

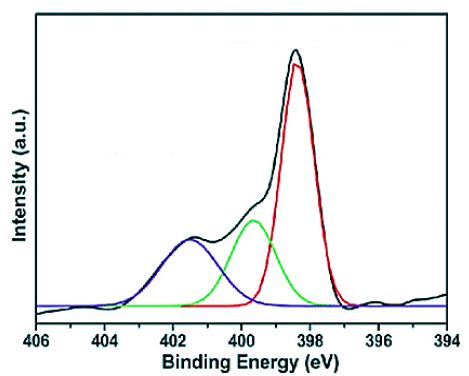

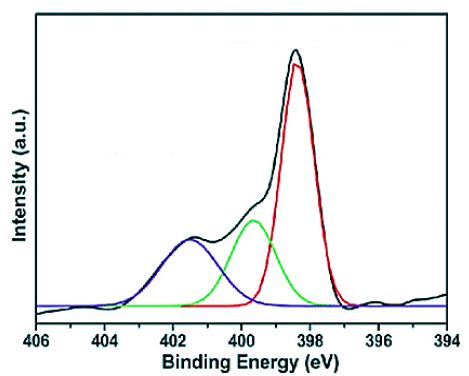

The Results of X-Ray Photoelectron Spectroscopy (XPS) Analysis

The XPS analysis of pure g-C3N4 NPs, pure ZnWO4 NPs, PANI and PANI/g-C3N4/ZnWO4 ternary NCs, respectively, were perforned to investigate in aqueous solution with photocatalytic degradation process for glyphosate removal (Figure 8). Absorption peaks were observed at binding energy of 401.51 eV for pure g-C3N4 NPs (blue pattern) (Figure 8a), 399.63 eV for pure ZnWO4 NPs (green pattern) (Figure 8b), 398.12 eV for PANI (red patern) (Figure 8c) and 398.36 eV for PANI/g-C3N4/ZnWO4 NCs (black pattern) (Figure 8d), respectively, in aqueous solution with photocatalytic degradation process for glyphosate removal.

Figure 8: The XPS spectra of (a) pure g-C3N4 NPs (blue pattern) (b) pure ZnWO4 NPs (green pattern), (c) PANI (red pattern) and (d) PANI/g-C3N4/ZnWO4 NCs (black pattern), respectively, in aqueous solution with photocatalytic degradation process for glyphosate removal.

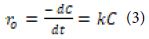

The Reaction Kinetics of Glyphosate Herbicide

The reaction kinetics glyphosate were investigated using the Langmuir-Hinshelwood first-order kinetic model, expressed by Eddy et al. [119], as following Equation (3):

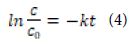

where; ro: denotes the initial photocatalytic degradation reaction rate (mg/l.min), and k: denotes the rate constant of a first-order reaction. At the beginning of the reaction, t=0, Ct=C0, the equation can be obtained after integration as following Equation (4):

where; C0 and C: are the initial and final concentration (mg/l) of glyphosate; the solution at t (min) and k (1/min) are the rate constant.

The pollutants photocatalytic degradation rate was found using a pseudo first-order reaction kinetic equation (Equation 5):

where; Kapp: is the apparent rate constant, C0: is the pollutant concentration before illumination and Ct: is the final concentration of the pollutant at time t.

The correlation coefficients had R2 values greater than 0.9, as a result, the first-order kinetic model fit the experimental data well. The first-order rate constants (k) were determined from the slope of the linear plots.

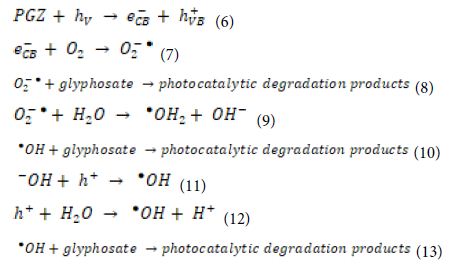

Photocatalytic Degradation Mechanisms

The possible photocatalytic reactions for glyphosate degradation over the PANI/g-C3N4/ZnWO4 ternary heterojunction (PGZ) can be expressed as following Equation (6), Equation (7), Equation (8), Equation (9), Equation (10), Equation (11), Equation (12) and Equation (13):

The photocatalytic degradation mechanism can be better understood when it is correlated to the kinetics of the degradation reaction. The rate constants were determined from the equation ln(Ct/C0)=Kappt, where Kapp is the apparent rate constant for the reaction, and C0 and Ct represent the initial and final (after time t) concentrations of glyphosate. The apparent rate constants were calculated from the experimental data. Linear fitting between the experimental data and pseudo-first order kinetic model suggested that the degradation process of glyphosate follows the pseudo-first-order kinetic model. The optimized results indicate the highest photo-degradation ability and kinetics for the PANI/g-C3N4/ZnWO4 ternary NCs, which may be due to its suitable composition and enhanced surface active sites as suggested by BET (Brunner-Emmett-Teller) analysis.

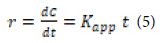

Effect of Increasing pH values for Glyphosate Removal in Aqueous Solution during Photocatalytic Degradation Process

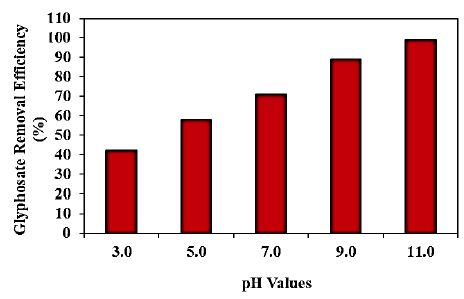

Increasing pH values (pH=3.0, pH=5.0, pH=7.0, pH=9.0 and pH=11.0, respectively) was examined during photocatalytic degradation process in aqueous solution for glyphosate removal (Figure 9). 42%, 58%, 71% and 89% glyphosate removal efficiencies was measured at pH=3.0, pH=5.0, pH=7.0 and pH=9.0, respectively, at 150 W UV-vis light irradiation power, after 180 min photocatalytic degradation time, at 25°C (Figure 9). The maximum 99% glyphosate removal efficiency was obtained during photocatalytic degradation process in aqueous solution, at pH=11.0, at 150 W UV-vis light irradiation power, after 180 min photocatalytic degradation time and at 25°C, respectively (Figure 9).

Figure 9: Effect of increasing pH values for glyphosate removal in aqueous solution during photocatalytic degradation process, at 150 W UV-vis light irradiation power, after 180 min photocatalytic degradation time and at 25°C, respectively.

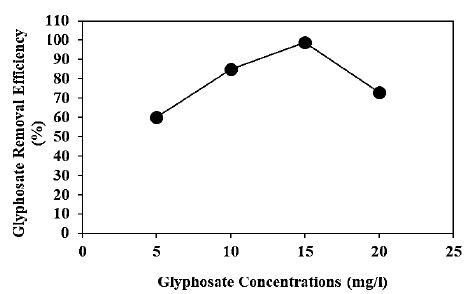

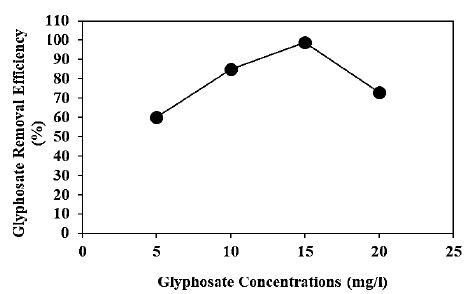

Effect of Increasing Glyphosate Concentrations for Glyphosate Removal in Aqueous Solution during Photocatalytic Degradation Process

Increasing glyphosate concentrations (5 mg/l, 10 mg/l, 15 mg/l and 20 mg/l) were operated at 150 W UV-vis light irradiation power, after 180 min photocatalytic degradation time, at pH=11.0, at 25°C, respectively (Figure 10). 60%, 85% and 73% glyphosate removal efficiencies were obtained to 5 mg/l, 10 mg/l and 20 mg/l glyphosate concentrations, respectively, at 150 W UV-vis light irradiation power, after 180 min photocatalytic degradation time, at pH=11.0 and at 25°C (Figure 10). The maximum 99% glyphosate removal efficieny was found with photocatalytic degradation process in aqueous solution, at 15 mg/l glyphosate, at 150 W UV-vis light irradiation power, after 180 min photocatalytic degradation time, at pH=11.0 and at 25°C, respectively (Figure 10).

Figure 10: Effect of increasing glyphosate concentrations for glyphosate removal in aqueous solution during photocatalytic degradation process, at 150 W UV-vis light irradiation power, after 180 min photocatalytic degradation time, at pH=11.0 and at 25°C, respectively.

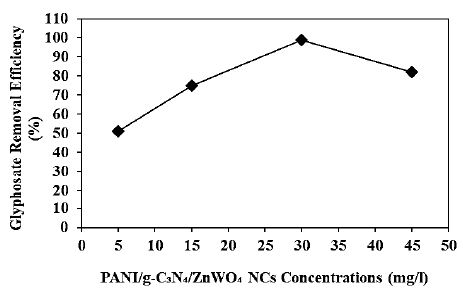

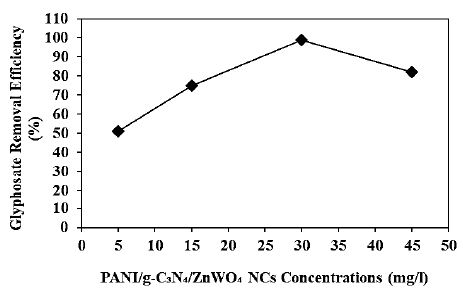

Effect of Increasing PANI/g-C3N4/ZnWO4 Ternary NCs Concentrations for Glyphosate Removals in Aqueous Solution during Photocatalytic Degradation Process

Increasing PANI/g-C3N4/ZnWO4 ternary NCs concentrations (5 mg/l, 15 mg/l, 30 mg/l and 45 mg/l) were operated at 15 mg/l glyphosate, at 150 W UV-vis light irradiation power, after 180 min photocatalytic degradation time, at pH=11.0, at 25°C, respectively (Figure 11). 51%, 75% and 82% glyphosate removal efficiencies were obtained to 5 mg/l, 15 mg/l and 45 mg/l PANI/g-C3N4/ZnWO4 ternary NCs concentrations, respectively, at 15 mg/l glyphossate, at 150 W UV-vis light irradiation power, after 180 min photocatalytic degradation time, at pH=11.0, at 25°C, respectively (Figure 11). The maximum 99% glyphosate removal efficieny was measured to 30 mg/l PANI/g-C3N4/ZnWO4 ternary NCs with photocatalytic degradation process in aqueous solution, at 15 mg/l glyphosate, at 150 W UV-vis light irradiation power, after 180 min photocatalytic degradation time, at pH=11.0 and at 25°C, respectively (Figure 11).

Figure 11: Effect of increasing PANI/g-C3N4/ZnWO4 ternary NCs concentrations for glyphosate removal in aqueous solution during photocatalytic degradation process, at 15 mg/l glyphosate, at 150 W UV-vis light irradiation power, after 180 min photocatalytic degradation time, at pH=11.0 and at 25°C, respectively.

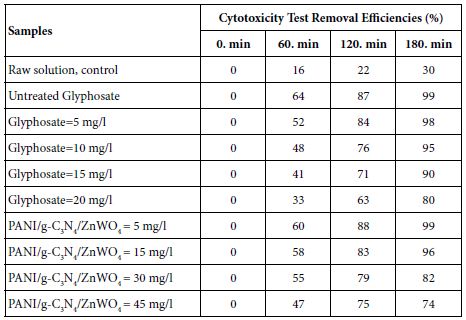

The Results of Cytotoxicity Test

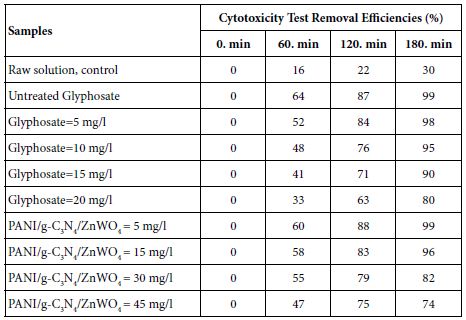

The cytotoxicity of PANI/g-C3N4/ZnWO4 ternary NCs photocatalyst and the glyphosate solutions were tested with the TBE assay analytical protocol and by considering with Drosophila melanogaster larvae before and after photocatalytic degradation process. Cytotoxicity test was performed with untreated glyphosate solution and after photodegradation process sample of different glyphosate concentrations (5 mg/l, 10 mg/l, 15 mg/l and 20 mg/l) and different PANI/g-C3N4/ZnWO4 ternary NCs concentrations (5 mg/l, 15 mg/l, 30 mg/l and 45 mg/l), at 25°C, at pH=7.0, respectively (Table 1).

98%, 95%, 90% and 80% cyctotoxicity removal efficiencies were obtained to 5 mg/l, 10 mg/l, 15 mg/l and 20 mg/l glyphosate concentrations, respectively, after 180 min photocatalytic degradation time, at 150 W UV-vis light irradiation power, at pH=7.0 and at 25°C, respectively (Table 1). The maximum 99% cyctotoxicity removal was observed at untreated glyphosate samples, after 180 min photocatalytic degradation time, at 150 W UV-vis light irradiation power, at pH=7.0 and at 25°C, respectively (Table 1).

96%, 82% and 74% cyctotoxicity removal efficiencies were measured to 15 mg/l, 30 mg/l and 45 mg/l PANI/g-C3N4/ZnWO4 ternary NCs photocatalyst concentrations, respectively, after 180 min photocatalytic degradation time, at 150 W UV-vis light irradiation power, at pH=7.0 and at 25°C, respectively (Table 1). The maximum 99% cyctotoxicity removal was observed at 5 mg/l PANI/g-C3N4/ZnWO4 ternary NCs photocatalyst concentrations, after 180 min photocatalytic degradation time, at 150 W UV-vis light irradiation power, at pH=7.0 and at 25°C, respectively (Table 1). The study revealed the excellent minimization of cytotoxicity of glyphosate after photocatalytic degradation process with the PANI/g-C3N4/ZnWO4 ternary NCs photocatalyst. Also, the PANI/g-C3N4/ZnWO4 ternary NCs photocatalyst is found to be non-cytotoxic irrespective of its quantity used.

Table 1: Effect of increasing glyphosate and PANI/g-C3N4/ZnWO4 ternary NCs concentrations on cyctotoxicity test in aqueous solution after photocatalytic degradation process, at 25°C, at pH=7.0, respectively.

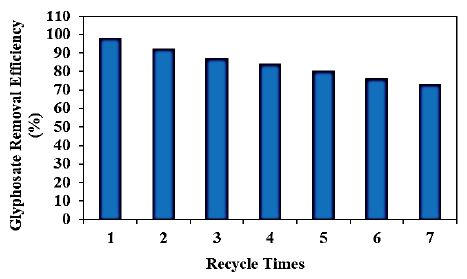

Effect of Different Recycle Times for Glyphosate Removals in Aqueous Solution during Photocatalytic Degradation Process

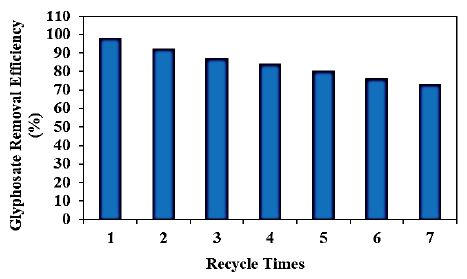

Different recycle times (1., 2., 3., 4., 5., 6. and 7.) were operated for glyphosate removals in aqueous solution during photocatalytic degradation process, at 15 mg/l glyphosate, 30 mg/l PANI/g-C3N4/ZnWO4 ternary NCs, at 150 W UV-vis light irradiation power, after 180 min photocatalytic degradation time, at pH=11.0 and at 25°C, respectively (Figure 12). 92%, 87%, 84%, 80%, 76% and 73% glyphosate removal efficiencies were measured after 2. recycle time, 3. recycle time, 4. recycle time, 5. recycle time, 6. recycle time and 7. recycle time, respectively, at 15 mg/l glyphosate, 30 mg/l PANI/g-C3N4/ZnWO4 ternary NCs, at 150 W UV-vis light irradiation power, after 180 min photocatalytic degradation time, at pH=11.0 and at 25°C, respectively (Figure 12). The maximum 99% glyphosate removal efficiency was measured in aqueous solution during photocatalytic degradation process, after 1. recycle time, at 15 mg/l glyphosate, 30 mg/l PANI/g-C3N4/ZnWO4 ternary NCs, at 150 W UV-vis light irradiation power, after 180 min photocatalytic degradation time, at pH=11.0 and at 25°C, respectively (Figure 12).

Figure 12: Effect of recycle times for glyphosate removal in aqueous solution during photocatalytic degradation process, at 15 mg/l glyphosate, 30 mg/l PANI/g-C3N4/ZnWO4 ternary NCs, at 150 W UV-vis light irradiation power, after 180 min photocatalytic degradation time, at pH=11.0 and at 25°C, respectively.

Conclusıons

The maximum 99% glyphosate removal efficiency was obtained during photocatalytic degradation process in aqueous solution, at pH=11.0, at 150 W UV-vis light irradiation power, after 180 min photocatalytic degradation time and at 25°C, respectively.The maximum 99% glyphosate removal efficieny was found with photocatalytic degradation process in aqueous solution, at 15 mg/l glyphosate, at 150 W UV-vis light irradiation power, after 180 min photocatalytic degradation time, at pH=11.0 and at 25°C, respectively.The maximum 99% glyphosate removal efficieny was measured to 30 mg/l PANI/g-C3N4/ZnWO4 ternary NCs with photocatalytic degradation process in aqueous solution, at 15 mg/l glyphosate, at 150 W UV-vis light irradiation power, after 180 min photocatalytic degradation time, at pH=11.0 and at 25°C, respectively.The maximum 99% cyctotoxicity removal was observed at untreated glyphosate samples, after 180 min photocatalytic degradation time, at 150 W UV-vis light irradiation power, at pH=7.0 and at 25°C, respectively. The maximum 99% cyctotoxicity removal was observed at 5 mg/l PANI/g-C3N4/ZnWO4 ternary NCs photocatalyst concentrations, after 180 min photocatalytic degradation time, at 150 W UV-vis light irradiation power, at pH=7.0 and at 25°C, respectively. The study revealed the excellent minimization of cytotoxicity of glyphosate after photocatalytic degradation process with the PANI/g-C3N4/ZnWO4 ternary NCs photocatalyst. Also, the PANI/g-C3N4/ZnWO4 ternary NCs photocatalyst is found to be non-cytotoxic irrespective of its quantity used.

As a result, the a novel PANI/g-C3N4/CoMoO4 ternary NCs photocatalyst during photocatalytic degradation process in aqueous solution for glyphosate removal was stable in harsh environments such as acidic, alkaline, saline, and then was still effective process. When the amount of contaminant was increased, the a novel PANI/g-C3N4/CoMoO4 ternary NCs photocatalyst during photocatalytic degradation process performance was still considerable. The synthesis and optimization of a novel PANI/g-C3N4/CoMoO4 ternary NCs heterostructure photocatalyst provides insights into the effects of preparation conditions on the material’s characteristics and performance, as well as the application of the effectively designed photocatalyst in the removal of gylphosate herbicites, which can potentially be deployed for purifying wastewater, especially agricultural industry wastewater treatment. Finally, the combination of a simple, easy operation preparation process, excellent performance and cost effective, makes this a novel PANI/g-C3N4/CoMoO4 ternary NCs heterostructure photocatalyst a promising option during photocatalytic degradation process in agricultural industry wastewater treatment.

Acknowledgement

This research study was undertaken in the Environmental Microbiology Laboratories at Dokuz Eylül University Engineering Faculty Environmental Engineering Department, Izmir, Turkey. The authors would like to thank this body for providing financial support.

References

- Rout PR, Zhang TC, Bhunia P, Surampalli RY (2021) Treatment technologies for emerging contaminants in wastewater treatment plants: A review. Sci Total Environ 753: 141990. [crossref]

- Song B, Xu P, Chen M, Tang W, Zeng G, et al. (2019) Using nanomaterials to facilitate the phytoremediation of contaminated soil Crit Rev Environ Sci Tecnol 49: 791-824.

- Xiang H, Zhang Y, Atkinson D, Sekar R (2020) Effects of anthropogenic subsidy and glyphosate on macroinvertebrates in streams. Environ Sci Pollut Res 27: 21939-21952.[crossref]

- García-García CR, Parrón T, Requena M, Alarcón R, Tsatsakis AM, et al. (2016) Occupational pesticide exposure and adverse health effects at the clinical, hematological and biochemical level. Life Sci145: 274-283. [crossref]

- Saleh IA, Zouari N, Al-Ghouti MA (2020) Removal of pesticides from water and wastewater: Chemical, physical and biological treatment approaches. Environ Technol Innov 19: 101026.

- Sharma A, Kumar V, Shahzad B, Tanveer M, Sidhu GPS, et al. (2019) Worldwide pesticide usage and its impacts on ecosystem. Sn Appl Sci 11: 1446-1462.

- Mostafalou S, Abdollahi M (2013) Pesticides and human chronic diseases: Evidences, mechanisms, and perspectives. Toxicol Appl Pharmacol 268: 157-177.[crossref]

- Casida JE, Durkin KA (2017) Pesticide chemical research in toxicology: Lessons from nature. Chem Res Toxicol 30: 94-104. [crossref]

- Abdennouri M, Baâlala M, Galadi A, El Makhfouk M, Bensitel M, et al. (2016). Photocatalytic degradation of pesticides by titanium dioxide and titanium pillared purified clays. Arab J Chem 9: S313-S318.

- Liu G, Li L, Huang X, Zheng S, Xu X, et al. (2018) Adsorption and removal of organophosphorus pesticides from environmental water and soil samples by using magnetic multi-walled carbon nanotubes@ organic framework ZIF-8. J Mater Sci 53: 10772-10783.

- Pandiselvam R, Kaavya R, Jayanath Y, Veenuttranon K, Lueprasitsakul P, et al. (2020) Ozone as a novel emerging technology for the dissipation of pesticide residues in foods—A review. Trends Food Sci Technol 97: 38-54.

- Barka N, Qourzal S, Assabbane A, Nounah A, Ait-Ichou Y (2010) Photocatalytic degradation of an azo reactive dye, Reactive Yellow 84, in water using an industrial titanium dioxide coated media. Arab J Chem 3: 279-283.

- Dehghani MH, Karamitabar Y, Changani F, Heidarinejad Z (2019) High performance degradation of phenol from aqueous media using ozonation process and zinc oxide nanoparticles as a semiconductor photo catalyst in the presence of ultraviolet radiation. Desalin Water Treat 166: 105-114.

- Ibhadon AO, Fitzpatrick P (2013) Heterogeneous photocatalysis: Recent advances and applications. Catalysts 3: 189-218.

- Silva WL, Lansarin MA, Livotto PR, Santos JHZ (2015) Photocatalytic degradation of drugs by supported titania-based catalysts produced from petrochemical plant residue. Powder Technol 279: 166-172.

- Dariani RS, Esmaeili A, Mortezaali A, Dehghanpour S (2016) Photocatalytic reaction and degradation of methylene blue on TiO2 nano-sized particles. Optik 127: 7143-7154.

- Kamat PV (2012) TiO2 Nanostructures: Recent Physical Chemistry Advances. J Phys Chem C 116: 11849-11851.

- Hernández S, Hidalgo D, Sacco A, Chiodoni A, Lamberti A, et al. (2015). Comparison of photocatalytic and transport properties of TiO2 and ZnO nanostructures for solar-driven water splitting. Phys Chem Chem Phys 17: 7775-7786.[crossref]

- Das S, Srivastava VC (2017) Synthesis and characterization of ZnO/CuO nanocomposite by electrochemical method. Mater Sci Semicond Process 57: 173-177.

- Saravanan R, Karthikeyan S, Gupta VK, Sekaran G, Narayanan V, et al. (2013) Enhanced photocatalytic activity of ZnO/CuO nanocomposite for the degradation of textile dye on visible light illumination. Mater Sci Eng C 33: 91-98. [crossref]

- Da Silva Bruckmann F, Ledur CM, da Silva IZ, Dotto GL, Rhoden CRB (2022) A DFT theoretical and experimental study about tetracycline adsorption onto magnetic graphene oxide. J Mol Liq 353: 118837.

- Rane AV, Kanny K, Abitha VK, Thomas S (2018) Methods for synthesis of nanoparticles and fabrication of nanocomposites. In Synthesis of Inorganic Nanomaterials; Woodhead Publishing: Amsterdam 121-139.

- Omanovi´c-Mikliˇcanin E, Badnjevi´c A, Kazlagi´c A, Hajlovac M (2020) Nanocomposites: A brief review. Health Technol 10: 51-59.

- Nunes FB, Da Silva Bruckmann F, Da Rosa Salles T, Rhoden CBR (2022) Study of phenobarbital removal from the aqueous solutions employing magnetite-functionalized chitosan. Environ Sci Pollut Res 12: 908-931. [crossref]

- Khan I; Saeed K; Khan I (2019) Nanoparticles: Properties, applications and toxicities. Arab J Chem 12: 908-931.

- Yoldi M, Fuentes-Ordoñez E, Korili S, Gil A (2019) Zeolite synthesis from industrial wastes. Microporous Mesoporous Materials 287: 183-191.

- Mintova S, Jaber M, Valtchev V (2015) Nanosized microporous crystals: Emerging applications. Chem Soc Rev 44: 7207-7233.[crossref]

- Nguyen CH, Tran HN, Fu CC, Lu YT, Juang RS (2020) Roles of adsorption and photocatalysis in removing organic pollutants from water by activated carbon-supported titania composites: Kinetic aspects. J Taiwan Inst Chem Eng 109: 51-61.

- Bruckmann FS, Rossato Viana A, Tonel MZ, Fagan SB, Garcia WJS, et al. (2022) Influence of magnetite incorporation into chitosan on the adsorption of the methotrexate and in vitro cytotoxicity. Environ Sci Pollut Res 29: 70413-70434.[crossref]

- Rahimi B, Jafari N, Abdolahnejad A, Farrokhzadeh H, Ebrahimi A (2019) Application of efficient photocatalytic process using a novel BiVO/TiO2-NaY zeolite composite for removal of acid orange 10 dye in aqueous solutions: Modeling by response surface methodology (RSM) J Environ Chem Eng 7: 103253.

- Falyouna O, Eljamal O, Maamoun I, Tahara A, Sugihara Y (2020) Magnetic zeolite synthesis for efficient removal of cesium in a lab-scale continuous treatment system. J Colloid Interface Sci 571: 66-79.[crossref]

- Steinrucken H, Amrhein N (1984) 5-Enolpyruvylshikimate-3-phosphate syn- € thase of Klebsiella pneumoniae 2. Inhibition by glyphosate [N-(phosphonomethyl)glycine]. Eur J Biochem 143: 351-357.[crossref]

- Benbrook C (2016) Trends in glyphosate herbicide use in the United States and globally. Environ Sci Eur 28: Article number: 3.[crossref]

- Williams G, Kroes R, Munro I (2000) Safety evaluation and risk assessment of the herbicide Roundup and its active ingredient, glyphosate, for humans. Regul Toxicol Pharmacol 31: 117-165.[crossref]

- Alferness P, Iwata Y (2002) Determination of glyphosate and (aminomethyl)- phosphonic acid in soil, plant and animal matrixes, and water by capillary gas chromatography with mass-selective detection. Am Chem Soc 42: 2751-2759.

- Caloni F, Cortinovis C, Rivolta M, Davanzo F (2016) Suspected poisoning of domestic animals by pesticides. Sci Total Environ 539: 331-336.[crossref]

- El-Gendy K, Mosallam E, Ahmed N, Aly N (2018) Determination of glyphosate residues in Egyptian soil samples. Anal Biochem 557: 1-6.[crossref]

- Acquavella J, Alexander B, Mandel J, Gustin C, Baker B, et al. (2004) Glyphosate biomonitoring for farmers and their families: Results from the Farm Family Exposure Study. Environ Health Perspect 112: 321-326. [crossref]

- Gillezeau C, van Gerwen M, Shaffer R, Rana I, Zhang L, et al. (2019) The evidence of human exposure to glyphosate: A review. Environ Health 18: 2.

- Martinez T, Long W, Hiller, R (1990) Comparison of the toxicology of the herbicide Roundup by oral and pulmonary routes of exposure. Proc West Pharmacol Soc 33: 193-197.[crossref]

- Connolly A, Coggins M, Galea K, Jones K, Kenny L, et al. (2019) Evaluating glyphosate exposure routes and their contribution to total body burden: A study among amenity horticulturalists. Ann Work Expo Health 63: 133-147.[crossref]

- Vandenberg LN, Blumberg B, Antoniou MN, Benbrook CM, Carroll L, et al. (2017) Is it time to reassess current safety standards for glyphosate-based herbicides? J Epidemiol Community Health 71: 613-618.

- IARC (2015) Outdoor Air Pollution. IARC Monographs on the Evaluation of Carcinogenic Risks to Humans 109.

- EFSA (2016) The 2014 European Union Report on pesticide residues in food. EFSA J 14: e04611.

- ATSDR (2019) Toxicological Profile for Silica. Atlanta, GA: U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, Public Health Service.

- CDC (2009) Fourth National Report on Human Exposure to Environmental Chemicals. Atlanta (GA)

- Huang Y, Li Z, Yao K, Chen C, Deng C, et al. (2021) Suppressing toxic intermediates during photocatalytic degradation of glyphosate by controlling adsorption modes. Appli Catal B: Environ 299: 120671.

- Duke SO, Powles SB (2009) Glyphosate-resistant crops and weeds: now and in the future. AgBioForum 12: 346-357.

- Annett R, Habibi HR, Hontela A (2014) Impact of glyphosate and glyphosate-based herbicides on the freshwater environment. J Appl Toxicol 34: 458-479. [crossref]

- United States Geological Survey, Pesticide National Synthesis Project, 2014.

- Torretta V, Katsoyiannis IA, Viotti P, Rada EC (2018) Critical review of the effects of glyphosate exposure to the environment and humans through the food supply chain. Sustainability 10: 950.

- Wang H, Zhang L, Chen Z, Hu J, Li S, et al. (2014) Semiconductor heterojunction photocatalysts: design, construction, and photocatalytic performances. Chem Soc Rev 43: 5234-5244.

- Cai H, Wang B, Xiong L, Bi J, Yuan L, et al. (2019) Orienting the charge transfer path of type-II heterojunction for photocatalytic hydrogen evolution. Appl Catal B 256: 117853.

- Di T, Xu Q, Ho W, Tang H, Xiang Q, et al. (2019) Review on metal sulphide-based Z-scheme photocatalysts. ChemCatChem 11: 1394-1411.

- Low J, Jiang C, Chen B, Wageh S, Al-Ghamdi AA, et al. (2017) A review of direct Z-scheme photocatalysts. Small Methods 1: 1700080.

- Yang C, Xue Z, Qin J, Sawangphruk M, Rajendran S, et al. (2019) Visible-light driven photocatalytic H2 generation and mechanism insights on Bi2O2CO3/G-C3N4 Z-scheme photocatalyst. J Phys Chem C 123: 4795-4804.

- Liang C, Niu CG, Guo H, Huang DW, Wen XJ, et al. (2018) Combination of efficient charge separation with the assistance of novel dual Z-scheme system: self-assembly photocatalyst Ag@AgI/BiOI modified oxygen-doped carbon nitride nanosheet with enhanced photocatalytic performance. Catal Sci Technol 8: 1161-1175.

- Zhu L, Li H, Xu Q, Xiong D, Xia P (2020) High-efficient separation of photoinduced carriers on double Z-scheme heterojunction for superior photocatalytic CO2 J Colloid Interface Sci 564: 303-312.[crossref]

- Liu X, Cai L (2019) A novel double Z-scheme BiOBr-GO-polyaniline photocatalyst: Study on the excellent photocatalytic performance and photocatalytic mechanism. Appl Surf Sci 483: 875-887.

- Wang M, Tan G, Ren H, Xia A, Liu Y (2019) Direct double Z-scheme O-g-C3N4/Zn2SnO4N/ZnO ternary heterojunction photocatalyst with enhanced visible photocatalytic activity. Appl Surf Sci 492: 690-702.

- Ravula S, Zhang C, Essner JB, Robertson JD, Lin J, et al. (2017) Ionic Liquid-Assisted Synthesis of Nanoscale (MoS2)x(SnO2)1-x on Reduced Graphene Oxide for the Electrocatalytic Hydrogen Evolution Reaction. ACS Appl Mater Interfaces, 9: 8065-8074.[crossref]

- Barik B, Kumar A, Nayak PS, Achary LSK, Rout L, et al. (2020) Ionic liquid assisted mesoporous silica-graphene oxide nanocomposite synthesis and its application for removal of heavy metal ions from water. Materials Chemistry and Physics, 239: 122028.

- Pahovnik D, Žagar E, Vohlídal J, Žigon M (2010) Ionic liquid-induced formation of polyaniline nanostructures during the chemical polymerization of aniline in an acidic aqueous medium. Synthetic Metals 160: 1761-1766.

- Zhao S, Fang J, Wang Y, Zhang Y, Zhou Y (2019) Poly(ionic liquid)-assisted synthesis of open-ended carbon nitride tube for efficient photocatalytic hydrogen evolution under visible-light irradiation. ACS Sustainable Chem Eng 7: 10095-10104.

- Okamoto Y, Brenner W (1964) Organic Semiconductors. New York: Reinhold Publishing Corporation.

- Heeger, A (201) Nobel Lecture: Semiconducting and metallic polymers: The fourth generation of polymeric materials. Reviews of Modern Physics 73: 681-700.

- Chen S, Huang D, Zeng G, Xue W, Lei L, et al. (2020) In-situ synthesis of facet-dependent BiVO4/Ag3PO4/PANI photocatalyst with enhanced visible-light-induced photocatalytic degradation performance: Synergism of interfacial coupling and hole-transfer. Chem Eng Sci 382: 122840.

- Jiang J, Li H, Zhang L (2012) New insight into daylight photocatalysis of AgBr@Ag: synergistic effect between semiconductor photocatalysis and plasmonic photocatalysis. Chemistry A European Journal 18: 6360-6369.

- Fu J, Yu J, Jiang C, Cheng B (2018) g-C3N4-based heterostructured photocatalysts. Adv Energy Mater 8: 1701503.

- Ren Y, Zeng D, Ong WJ (2019) Interfacial engineering of graphitic carbon nitride (g-C3N4)-based metal sulfide heterojunction photocatalysts for energy conversion: A review, Chin J Catal 40: 289-319.

- Hao Q, Chen T, Wang R, Feng J, Chen D (2018a) A separation-free polyacrylamide/bentonite/graphitic carbon nitride hydrogel with excellent performance in water treatment. J Clean Prod 197: 1222-1230.

- Hao X, Zhou J, Cui Z, Wang Y, Wang Y, et al. (2018b) Zn-vacancy mediated electron-hole separation in ZnS/g-C3N4 heterojunction for efficient visible-light photocatalytic hydrogen production. Appl Catal B 229: 41-51.

- Mestre AS, Carvalho AP (2019) Photocatalytic degradation of pharmaceuticals carbamazepine, diclofenac, and sulfamethoxazole by semiconductor and carbon materials: a review, Molecules 24: 3702. [crossref]

- Chen Y, Fan ZX, Zhang ZC, Niu WX, Li CL, et al. (2018) Two-dimensional metal nanomaterials: synthesis, properties, and applications. Chem Rev 118: 6409-6455.

- Xu Q, Zhang L, Yu J, Wageh S, Al-Ghamdi AA, et al. (2018) Direct Z-scheme photocatalysts: Principles, synthesis, and applications. Mater Today 21: 1042-1063.

- Huang D, Chen S, Zeng G, Gong X, Zhou CY, et al. (2019) Artificial Z-scheme photocatalytic system: What have been done and where to go?, Coord Chem Rev, 385: 44-80.

- Zhang X, Lou S, Zeng Y (2020) Facile fabrication of a novel visible light active g-C3N4-CoMoO4 heterojunction with largely improved photocatalytic performance. Mater Lett 281: 128661.

- Yu W, Xu D, Peng T (2015) Enhanced photocatalytic activity of g-C3N4 for selective CO2 reduction to CH3OH via facile coupling of ZnO: a direct Z-scheme mechanism. J Mater Chem A 3: 19936-19947.

- Liu X, Pang F, He M, Ge J (2017a) Confined reaction inside nanotubes: New approach to mesoporous g-C3N4 Nano Res 10: 3638-3647.

- Liu D, Zhang M, Xie W, Sun L, Chen Y, et al. (2017b) Porous BN/TiO2 hybrid nanosheets as highly efficient visible-light-driven photocatalysts, Appl Catal B-Environ 207: 72-78.

- Liu S, Chen F, Li S, Peng X, Xiong Y (2017) Enhanced photocatalytic conversion of greenhouse gas CO2 into solar fuels over g-C3N4 nanotubes with decorated transparent ZIF-8 nanoclusters. Appl Catal B 211: 1-10.

- Cui L, Ding X, Wang Y, Shi H, Huang L, et al. (2017). Facile preparation of Z-scheme WO3/g-C3N4 composite photocatalyst with enhanced photocatalytic performance under visible light. Appl Surf Sci B 391: 202-210.

- Gebreslassie G, Bharali P, Chandra U, Sergawie A, Boruah PK, et al. (2019a) Novel g-C3N4/graphene/NiFe2O4 nanocomposites as magnetically separable visible light driven photocatalysts. J Photochem Photobiol A 382: 111960.

- Gebreslassie G, Bharali P, Chandra U, Sergawie A, Boruah PK, et al. (2019b) Hydrothermal synthesis of g-C3N4/NiFe2O4 nanocomposite and its enhanced photocatalytic activity. Appl Organomet Chem 33: e5002.

- Wu J, Hu J, Qian H, Li J, Yang R, et al. (2022) NiCo/ZnO/g-C3N4 Z-scheme heterojunction nanoparticles with enhanced photocatalytic degradation oxytetracycline. Diamond Relat Mater 121: 108738.

- Qu Z, Jing Z, Chen X, Wang Z, Ren H, et al. (2023) Preparation and photocatalytic performance study of dual Z-scheme Bi2Zr2O7/g-C3N4/Ag3PO4 for removal of antibiotics by visible-light. J Environ Sci 125: 349-361. [crossref]

- Zhao H, Yu H, Quan X, Chen S, Zhang Y., et al. (2014) Fabrication of atomic single layer graphitic C3N4 and its high performance of photocatalytic disinfection under visible light irradiation. Appl Catal B 152-153: 46-50.

- Mamba G. Mishra AK (2016) Graphitic carbon nitride (g-C3N4) nanocomposites: A new and exciting generation of visible light driven photocatalysts for environmental pollution remediation. Appl Catal B 198: 347-377.

- Zhang C, Li Y, Shuai D, Shen Y, Xiong W, et al. (2019) Graphitic carbon nitride (g-C3N4)-based photocatalysts for water disinfection and microbial control: A review, Chemosphere 214: 462-479.[crossref]

- Darkwah WK, Ao Y (2018) Mini review on the structure and properties (photocatalysis), and preparation techniques of graphitic carbon nitride nano-based particle, and its applications. Nanoscale Res Lett 13: 388. [crossref]

- Oh WD, Chang VWC, Hu ZT, Goei R, Lim TT (2017) Enhancing the catalytic activity of g-C3N4 through Me doping (Me = Cu, Co and Fe) for selective sulfathiazole degradation via redox-based advanced oxidation process Chem Eng J 323: 260-269.

- Dai Y, Gu Y, Bu Y (2020) Modulation of the photocatalytic performance of g-C3N4 by two-sites co-doping using variable valence metal. Appl Surf Sci 500: 144036.

- Ye L, Liu J, Jiang Z, Peng T, Zan L (2013) Facets coupling of BiOBr-g-C3N4 composite photocatalyst for enhanced visible-light-driven photocatalytic activity. Appl Catal B 142-143: 1-7.

- Tian N, Huang H, He Y, Guo Y, Zhang T, et al. (2015) Mediator-free direct Z-scheme photocatalytic system: BiVO4/g-C3N4 organic-inorganic hybrid photocatalyst with highly efficient visible-light-induced photocatalytic activity, Dalton Trans., 44: 4297-4307.[crossref]

- Nithya R, Ayyappan S (2020) Novel exfoliated graphitic C3N4 hybridised ZnBi2O4 (g-C3N4/ZnBi2O4) nanorods for catalytic reduction of 4-Nitrophenol and its antibacterial activity. J Photochem Photobiol Chem 398: 112591.

- Tian N, Huang H, Wang S, Zhang T, Du X, et al. (2020) Facet-charge-induced coupling dependent interfacial photocharge separation: A case of BiOI/g-C3N4 p-n junction. Appl Catal B 267: 118697.

- Reddy CV, Koutavarapu R, Reddy IN, Shim J (2021) Effect of a novel onedimensional zinc tungsten oxide nanorods anchored two-dimensional graphitic carbon nitride nanosheets for improved solar-light-driven photocatalytic removal of toxic pollutants and photoelectrochemical water splitting. J Mater Sci Mater Electron 32: 33-46.

- Ojha DP, Kim HJ (2020) Investigation of photocatalytic activity of ZnO promoted hydrothermally synthesized ZnWO4 nanorods in UV-visible light irradiation. Chem Eng Sci 212: 115338.

- Ke J, Younis MA, Kong Y, Zhou H, Liu J, et al. (2018) Nanostructured ternary metal tungstate-based photocatalysts for environmental purification and solar water splitting: a review. Nano-Micro Lett 10: 69.[crossref]

- Liu H, Huang J, Chen J, Zhong J, Li J, et al. (2019) Preparation and characterization of novel Ag/Ag2WO4/ZnWO4 heterojunctions with significantly enhanced sunlight-driven photocatalytic performance. Solid State Sci 95: 105923.

- Enesca A (2021) The influence of photocatalytic reactors design and operating parameters on the wastewater organic pollutants removal – a mini review. Catalysts 11: 556: 1-22.

- Alshehri SM, Ahmed J, Ahamad T, Alhokbany N, Arunachalam P., et al. (2018) Synthesis, characterization, multifunctional electrochemical (OGR/ ORR/SCs) and photodegradable activities of ZnWO4 J Sol Gel Sci Technol 87: 137-146.

- Zhang L, Wang Z, Wang L, Xing Y, Li X, et al. (2014a) Electrochemical performance of ZnWO4/CNTs composite as anode materials for lithium-ion battery. Appl Surf Sci 305: 179-185.