DOI: 10.31038/PSC.2022211

Abstract

Childhood Obesity is a complex health issue caused by the abnormal accumulation or excessive fat in the body, threatening the life of the infant. We report the case of a 9 months old male infant who came in for a paediatric general consultation with complaints of left ocular reddishness and associated purulent discharge but was later on addressed to the endocrinologist consultation because was found to have a weight above normal on taking anthropometric parameters prior to consultation. After a complete medical observation, the diagnosis retained was communal obesity on the basis of a genetic predisposition (macrosomia at birth, a family history of obesity in both parents) and unhealthy life style habits (inappropriate nutrition). Through this case report with literature review, we wish to emphasize the facts that, although there are several aetiologies of obesity in children, the most common being communal obesity, include genetic predisposition which may serve as breeding ground to nutritional factors. Macrosomia appears to be a starting point, and so such babies should be followed up closely as they are at high risk of becoming obese later on in infancy. This with related complications. While the early diagnosis relies on routine assessment of anthropometric parameters, the effective management of communal obesity of childhood requires a multidisciplinary approach, with the parents being at the frontline.

Keywords

Macrosomia, Obesity, Anthropometric parameters, WHO-child growth curves

Introduction

Childhood Obesity is a challenging health issue caused by the abnormal accumulation or excessive fat in the body threatening the life of the infant through systemic involvement. The World Health Organization (WHO) defines obesity in children less than 5 years of age as a weight-for-height greater than 3 standard deviations above the WHO-Child Growth Standards median [1,2]. Many factors contribute to the onset of obesity in children such as non-modifiable factors including genetics and modifiable factors. Because anthropometric mensuration may suffice to pose the diagnosis, obesity is therefore a clinical diagnosis. It is worth mentioning that up to 39 million children under the age of 5 were overweight or obese in 2020 [1,2]. The fundamental cause of obesity is thought to be an energy imbalance between calories consumed and calories expended. Many factors might predispose to the onset of obesity in children. They can be classified as modifiable and non-modifiable risks factors with macrosomia and genetics being at the forefront, as it is often associated with a higher chance of obesity, premature death and disability in adulthood [3,4]. In addition to increased future risks, obese children experience breathing difficulties, hypertension, and early markers of cardiovascular disease, insulin resistance and psychological effects [3,4].

Case Report

We report the case of a 9 months old male infant who came in for a paediatric general consultation with complaints of left ocular reddishness and associated purulent discharge but was later on addressed to the endocrinologist consultation because was found to have a weight above normal on taking anthropometric parameters prior to consultation. The mother’s history revealed a notion of deliveries of big babies ˃ 3,5 kg. The pregnancy was uneventful without gestational diabetes, nor chronic diseases. The infant was born preterm at 36 weeks Gestational Age (GA) with a birth weight of 3600 g ˃ 95th percentile, with good extra uterine adaptation. Nutritional history permitted to note that the infant was exclusively breastfed up to 3 weeks of age, mixed feeding was then initiated till 6 months and thereafter, milk substitutes were stopped, while breast milk was continued thrice during the day and five times at night, in addition to meals that covered the day.

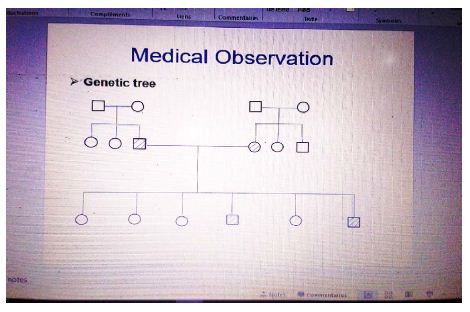

The Genetic Tree of Family Obesity

During the systemic enquiry we noted rhinorrhoea. On Physical exam, the infant was obese with weight at 15.8 Kg (˃ 3 zscore) and height at 80 cm (height˃ 3 zscore) weight-for-height index was ˃ 3-zscore as well. A flu-like syndrome was found with cough, rhinorrhoea and fever. There was systemic inflammatory response syndrome with fever at 38,5°c, tachycardia with 120 beats per minute and also reddishness of the left sclera associated with purulent discharge. No dysmorphic signs were found. The diagnosis posed was a left bacterial conjunctivitis associated with rhinitis in a child with communal obesity. The management consisted of nasal wash with serum saline as frequent as possible (at least 6 times daily), antipyretic with paracetamol syrup: 15 mg/kg/6 h, Fucidin gel 1%: 1 eye drop twice daily as ocular antibiotic. Most essentially, was diet modification by reducing breastfeeding frequency during the night from 5 to 1 time? The mother was advised to complete breastfeeding with mineral water in case the baby cried for more. The number of meals per day was maintained at 3, but was automatically to include fruits and vegetables.

Discussion

Childhood obesity is one of the most serious public health challenges in the 21st century. The genetic factor accounts for less than 5 percent of cases [3,4]. Foetal macrosomia is associated with increased risk of obesity in children under 3 years, with estimated risk of 3,74 folds higher than that of babies with normal birth weight [3,4]. Results from a study conducted by Sonia Sparano et al. in 2013 showed that macrosomia was an independent determinant of obesity after the adjustment of confounders [4,5]. This was the case of our patient, who was born premature at 36 weeks GA, but with birth weight of 3600 g˃95th percentile for gestational age, which corresponded to macrosomia. This is a condition which requires effective perinatal and deep neonatal assessments, given potential complications. More so, there was maternal obstetrical history of big babies, which was predisposing to macrosomia as well, and a contributing finding [6-19].

The diagnosis of obesity is solely made on a clinical basis and varies according to age of the infant. For infants aged ≤ 5 years the diagnosis relies upon the use of weigh-for-height growth curves from which an index ˃ 3 z-score is indicative of obesity. This was the case of our patient weighing 15.8 Kg for 80 cm height which corresponded to this classification. On the other hand, it is worth mentioning that the diagnosis of obesity in children aged ≥ 5 years makes use of the body mass index-for-age curves when ˃ 2 z-score. This indicates a necessity for routine anthropometric assessment in paediatric consultations [20-22].

The known risk factors of childhood obesity can be classified into two groups, namely: modifiable risk factors and non-modifiable risk factors. The modifiable risk factors include maternal overweight or obesity, maternal smoking, gestational weight gain, sleeping, sedentary lifestyle, lack of breastfeeding, infant and young child feeding [23-27]. Whereas the non-modifiable risk factors are genetic or familial, and high birth weight. Our patient had family history of obesity, as well as history of macrosomia which oriented etiological hypotheses towards genetic determinism.

In effect, there are several aetiologies attributed to childhood obesity. They could have a genetic origin, especially when there is family history as it was the case in the patient we presented. Nevertheless, obesity could as well be of endocrinal cause with hypothyroidism, growth hormone deficiency and hypercortisolemia, in which case there is usually characteristic stunting with rapid onset obesity [20-22]. From a semiological standpoint, childhood obesity may be communal, when there is no other possible nor identifiable cause than genetic. Meanwhile, it is classified as syndromic when associated with a spectrum of other anomalies such as mental retardation, dysmorphism and/or visceral malformations, hypogonadism, just to name a few. This is the case with classical paediatric syndromes such as Prader Wilis or Bardet Biedl syndromes in which dysmorphism is often associated with obesity.

Oedemato-ascitic syndromes such as in heart failure, nephrotic syndrome, malnutrition, and anaphylactic reaction are sometimes evoked as differential diagnoses in the discussion of childhood obesity. However, they lack consistency with regards to context, evolution, duration, and physical exam findings. As a matter of facts, the positive diagnosis of obesity is clinical as we earlier mentioned, and anthropometric parameters are pathognomonic [20-22].

The management of childhood obesity relies upon a multidisciplinary approach and spans on a long term. Specialists involved in this procedure include the paediatrician and/or endocrinologist who coordinate and evaluate the process at regular intervals. The nutritionist-dietician enables to regulate quality and quantity feeding, while the sports coach helps to lose weight through age-appropriate physical exercises. The role of a psychologist is important and may be indispensable especially in adolescents, for whom the development of individual character may transit through constant opposition to established rules and recommendations, doubled with rebellion [28]. Furthermore, in this population group, self-esteem is paramount, being grounded in mirror image, peer, and peers’ opinion. Surgical intervention with liposuction or partial gastrectomy is experimental in paediatrics, but may be envisaged in extreme situations, just as in adults. However, the initial management in our patient consisted solely of dietetic measures given the young age. This comprised modification of breastfeeding frequency, meals with vegetables, and fruits [23-27].

When childhood obesity is not adequately managed, complications are numerous and multisystemic, occuring as time goes on. The basis of these complications stem from four factors, including: disorders of excess lipid metabolism, atherosclerosis, physical impact of plethora and conditioning. Cardiovascular complications include dyslipidemia, hypertension, blood coagulation disorders, chronic inflammation and endothelial dysfunction which are all due to accumulating lipids [20-22]. Neuropsychological complications may occur with pseudotumor cerebri with intracranial hypertension syndrome mimicry, while poor self-esteem, depression and eating disorders are related with non-acceptation or non-coping with the body image. Pulmonary manifestations are also frequent with physical exercise intolerance, asthma, sleep apnoea, and are aggravated by lung compliance disorders. This is due to the work load of mobilising relatively massif surrounding tissues to the respiratory system. Increased lipogenesis may give rise to gastrointestinal and urinary complications with gallstones, steatohepatitis and glomerulosclerosis. Affected by the impact of weight, the musculoskeletal system can manifest with fractures and arthrosis. Whereas, the metabolic syndrome might induce endocrinopathies such as type-2 diabetes, precocious puberty, polycystic ovary syndrome in girls and hypogonadism in boys [20-22].

Conclusion

We reported a case of communal obesity with fortuitous discovery, in an infant predisposed through macrosomia and family obesity, to which a nutritional factor was grafted. The diagnosis being purely clinical through anthropometric mensuration, a long course but simplified management was initiated by the child specialist. This process essentially relied on parental observation of recommendations over nutrition and dietetics, based on the child’s age. Another important aspect of this paper was the emphasis on the need for routine assessment of anthropometric parameters during children consultations. This is important for the early diagnosis and management of growth or nutritional disorders in children, in order to prevent complications.

References

- Obesity: preventing and managing the global epidemic. Report of a WHO consultation. World Health Organ Tech rep Ser. 2000;894:i-xii,1-253. PMID: 11234459

- World Health Organization. Obesity and Overweight. Fact sheet 2014 311.

- Sahoo K, Sahoo B, Choudhury AK, Sofi NY, Kumar R, et al. (2015) Childhood obesity causes and consequences. J Family Med Prim Care 4: 187-192. [crossref]

- Pan XF, Tang L, Lee AH, Binns C, Yang Y, et al. (2019) Association between fetal macrosomia and risk of obesity in children under 3 years of age in western china: a cohort study. World J Pediatr 15: 153-160. [crossref]

- Sparano S, Ahrens W, De Henauw S, Marild S, Molnar D, et al. (2013) Being macrosomic at birth is an independent predictor of overweihgt in children: results from the IDEFICS study. Matern Chirld Health J 17: 1373-1381. [crossref]

- Chiabi A, Kago DA, Moyo GPK, Obadeyi B (2019) Relevance and Applicability of the Apgar Score in Current Clinical Practice. EC Paediatrics 8: 01-07.

- Moyo GPK, Tetsiguia JRM (2020) Discussing the “First Cry” as an Initial Assessment for Neonates. Am J of Pediatr 6: 129-132.

- Moyo GPK, Sobguemezing D, Adjifack HT (2020) Neonatal Emergencies in Full-term Infants: A Seasonal Description in a Pediatric Referral Hospital of Yaoundé, Cameroon. Am J Pediatr 6: 87-90.

- Moyo GPK, Um SSN, Awa HDM, et al. (2022) The pathophysiology of neonatal jaundice in urosepsis is complex with mixed bilirubin!!! J Pediatr Neonatal Care 12: 68-70.

- Moyo GPK, Nguedjam M, Miaffo L (2020) Necrotizing Enterocolitis Complicating Sepsis in a Late Preterm Cameroonian Infant. Am J Pediatr 6: 83-86.

- Moyo GPK, Sap Ngo Um S, Awa HDM, Mbang TA, Virginie B, Makowa LK et al. (2022) An Atypical Case of Congenital and Neonatal Grave’s Disease. Annal Cas Rep Rev 2.

- Ngwanou DH, Ngantchet E, Moyo GPK (2020) Prune-Belly syndrome, a rare case presentation in neonatology: about one case in Yaounde, Cameroon. Pan Afr Med J 36: 120. [crossref]

- Tague DAT, Evelyn Mah, Félicitee Nguefack, Moyo GPK, Tcheyanou LLK, et al. (2020) Beckwith-Wiedemann Syndrome: A Case Report at the Gynaeco-Obstetric and Pediatric Hospital in Yaounde, Cameroon. Am J Pediatr 6: 433-436.

- Moyo GPK, Mendomo RM, Batibonack C, Mbang AT (2020) Neonatal Determinants of Mothers’ Affective Involvement in Newly Delivered Cameroonian Women. Journal of Family Medicine and Health Care 6: 125-128.

- Moyo GPK (2020) Epidemio-clinical Profile of the Baby Blues in Cameroonian Women. Journal of Family Medicine and Health Care 6: 20-23.

- Moyo GPK, Djoda N (2020) Relationship between the Baby Blues and Postpartum Depression: A Study among Cameroonian Women. American Journal of Psychiatry and Neuroscience 8: 26-29.

- Moyo GPK (2020) Perinatality and Childbirth as a Factor of Decompensation of Mental Illness: The Case of Depressive States in Newly Delivered Cameroonian Women ABEB 4: 000592.

- Moyo GPK, Djoda N (2020) The Emotional Impact of Mode of Delivery in Cameroonian Mothers: Comparing Vaginal Delivery and Caesarean Section. American Journal of Psychiatry and Neuroscience 8: 22-25.

- Foumane P, Olen JPK, Fouedjio JH, GPK Moyo, Nsahlai C, Mboudou E (2016) Int J Reprod Contracept Obstet Gynecol 5: 4424-4427.

- Moyo GPK, Djomkam IFK (2020) Epidemio-clinical Profile of Stunting in School Children of an Urban Community in Cameroon. Am J Pediatr 6: 94-97.

- Moyo GPK, Djomkam IFK (2020) Factors Associated with Stunting in School Children of an Urban Community in Cameroon. Am J Pediatr 6: 121-124.

- Moyo GPK, Ngapout OD, Makowa LK, Mbang AT, Binda V, Albane EA et al. (2022) Exogenous Cushing’s Syndrome with Secondary Adrenal Insufficiency in an Asthmatic Infant: “Healing Evil with Evil”. Arch Pediatr 7: 203.

- Hermann ND. Moyo GPK (2020) Neonatal Determinants of Inadequate Breastfeeding: A Survey among a Group of Neonate Infants in Yaounde, Cameroon. Open Access Library Journal 7: e6541.

- Hermann ND, Moyo GPK, Ejake L, Félicitée N, Evelyn M, et al. (2020) Determinants of Breastfeeding Initiation Among Newly Delivered Women in Yaounde, Cameroon: a Cross-Sectional Survey. Health Sci Dis 21: 20-24.

- Moyo GPK, Dany Hermann ND (2020) Clinical Characteristics of a Group of Cameroonian Neonates with Delayed Breastfeeding Initiation. Am J Pediatr 6: 292-295.

- Moyo GPK, Hermann ND (2020) The Psycho-Sociocultural Considerations of Breastfeeding in a Group of Cameroonian Women with Inadequate Practices. J Psychiatry Psychiatric Disord 4: 130-138.

- Moyo GPK, Ngwanou DH, Sap SNU, Nguefack F, Mah EM (2020) The Pattern of Breastfeeding among a Group of Neonates in Yaoundé, Cameroon. International Journal of Progressive Sciences and Technologies 22: 61-66

- Moyo GPK (2020) Children and Adolescents’ Violence: The Pattern and Determinants Beyond Psychological Theories. Am J Pediatr 6: 138-145.

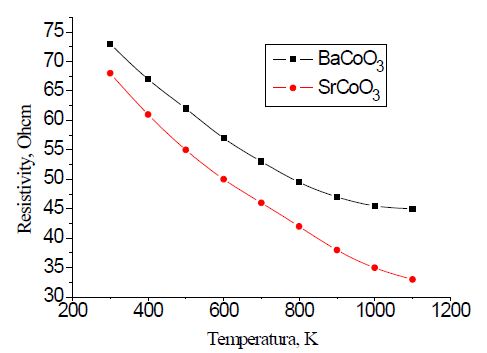

, where σ = 5.67 × 10-8 W/m2K is the Stefan Boltzmann constant, corresponded to the temperature of the heated body 1900°C. At this temperature, the sample melted. Melt droplets fell into water and cooled at a rate of 103 deg/s. Such cooling conditions made it possible to fix the high-temperature structural states of the material.

, where σ = 5.67 × 10-8 W/m2K is the Stefan Boltzmann constant, corresponded to the temperature of the heated body 1900°C. At this temperature, the sample melted. Melt droplets fell into water and cooled at a rate of 103 deg/s. Such cooling conditions made it possible to fix the high-temperature structural states of the material.