Abstract

With the help of AI-based SCAS (Socrates as a Service), developed to support Mind Genomics, the study considered the nature of the doctor’s waiting room of the year 1850, followed by a paragraph about the doctor’s waiting room in 50-year intervals, from years 1600 to 2350. SCAS produced basic information about the doctor’s office as it changed over the centuries and was able to use that basic information to create even more information regarding ideas for innovation. Mind Genomics was also prompted to suggest responses of acceptors versus rejectors of the features of the 1850 doctor’s office. The paper demonstrates the simplicity, speed, and depth of information that can be obtained using AI, and the promise of the coupling of interesting reading with deeper information.

Introduction: The ‘Draw’ of the ‘What Was’ and ‘What Will Be’

A continuing theme in many aspects of life is the fascination of what was and what will be. The world of history gives people a chance to experience what happened before, and the world of ‘future studies’ for want of a better term gives people a chance to look at trends and peer into a future which might be. Indeed, the focus on the world over time, before, now, and in the future, has given the world wonderful works of history, literature, philosophy, just to name a few disciplines.The introduction of AI, artificial intelligence, has made it possible to move beyond what has been published in history and in ‘futurology.’ Through its own mechanisms of deep learning, it may be possible to get a sense of what the past may have been, not so much from reading books, but from asking AI to paint a picture of a specific issue. Even more interesting may be the attempt to do the same, not so much painting a picture of the past as a picture of the reasonably near future, a few decades from now, or perhaps a century or so. It was the development of two technologies which, when combined, opened up the focus on the past. The first was the emerging technology of Mind Genomics [1]. In simplest terms, Mind Genomics is the study of the everyday, the ordinary events, material things, and behaviors. The second is the new availability of user-friendly AI, artificial intelligence, embedded in Mind Genomics as SCAS, (Socrates as a Service), and based upon current AI systems [2]. Mind Genomics opened up the possibility of studying the everyday more deeply, looking into features, painting a picture of a situation and understanding what is important to people. The result was the realization that the ordinary events of everyday, the quotidian life, are worth studying. SCAS, embodying easy to use AI, allowed the investigation of the everyday life, not by doing experiments but rather by asking the embedded AI to assume a situation, and then report on its details.

It is important to note that this paper follows in a stream of previous work, much of it trying to digitize the historical narrative, to make history ‘come alive’ to students [3-5]. Furthermore, a great deal of interest in AI-based simulation comes from the desire to add reality and depth to history-games, which are very popular. These games try to create a realistic ‘set’ and realistic ‘behaviors.’

Exploring a Simple Topic: The Doctor’s Waiting Room Across Years

The ‘research’ presented here began with a request to SCAS to present a short description of what the doctor’s office was like:

The year is: [provided by user]. Everything that is talked about here happened in [provided by user].The doctor is a general practitioner in New York

What should the waiting room of the doctor be like, in terms of decor, in terms of people, in terms of the way people are greeted. Write you answer as five sentences in one long paragraph, simply written, in order to give the reader a complete description. Make the writing lively, and fun to read, and make the description realistic, as if the person reading the description were to be right there, at this time and this place

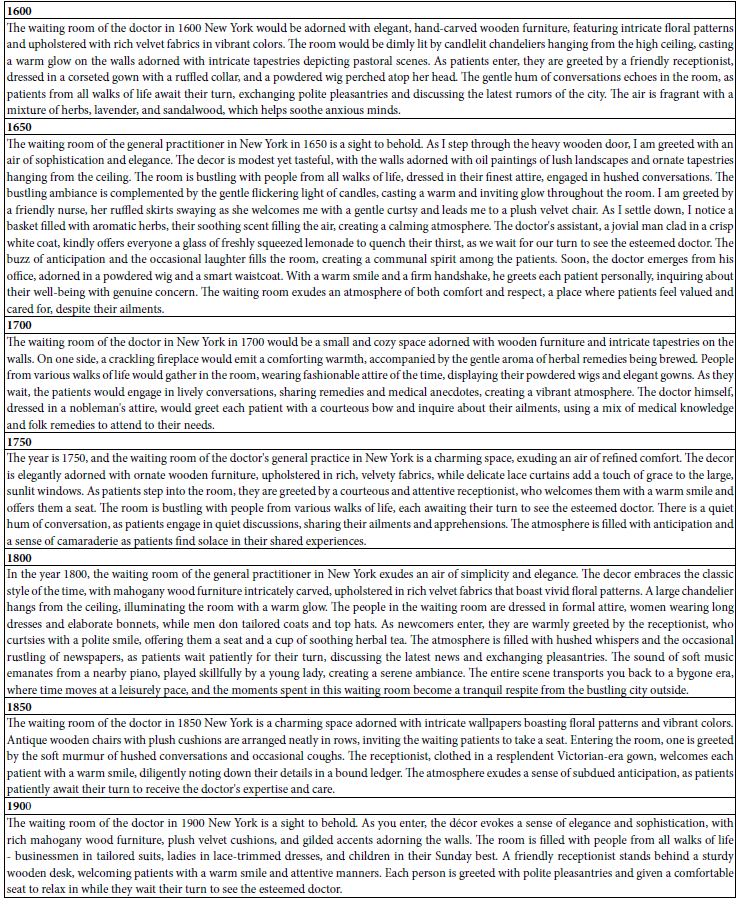

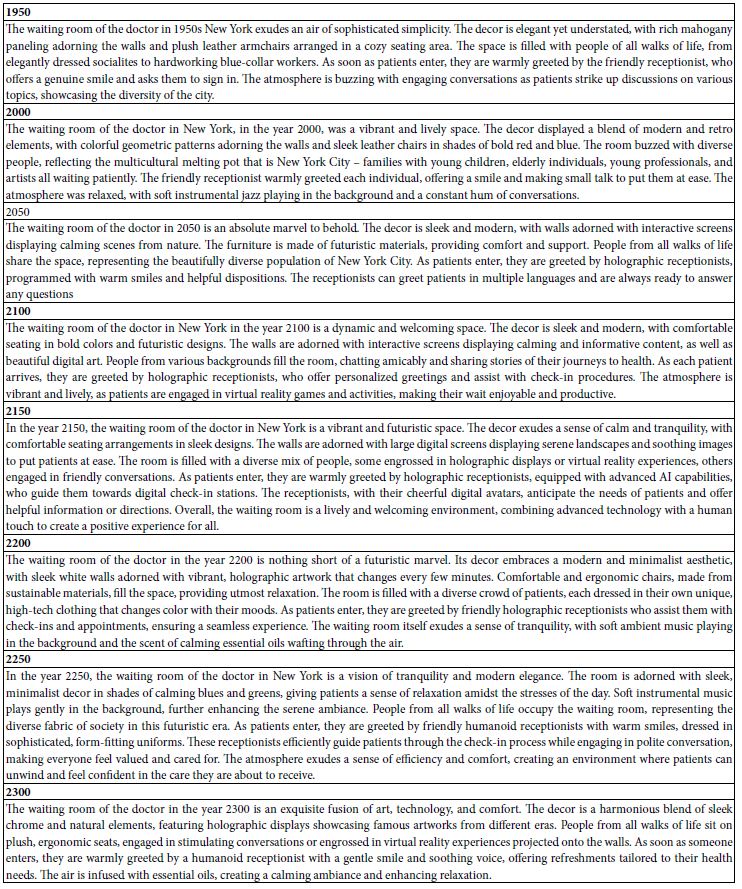

Table 1 shows the results for three years, 1900, 2000, and 2150., respectively. The appendix to this paper shows many more years, beginning with 1600 and going to 2300 in 50-year leaps. The first reaction to the ‘first fruits’ of this effort are summarized by the ‘astonishment.’ The paragraphs describing the mundane topic of the doctor’s waiting room seem real, as if someone were there. This led to doing the ‘experiment’ with 50-year intervals, starting in the year 1600, and proceeding to the year 2250. The Appendix those short descriptions.

Table 1: Descriptions of the doctor’s office, product for three years, 1900, 2000 and 2150

Exploring the Doctor’s Waiting Room in Detail – The Year is 1850

The remainder of this paper shows an AI-based exploration using SCAS. The year is 1850. The general instructions appeared above. SCAC produces the immediate output shown in Table 2. The material is similar to what appears in Table 1, as well as in the Appendix. Once again, it is important to emphasize that the paragraph is synthesized by SCAS without any information other than the year, and the directive to provide the answer as a story in five sentences.

Shortly after the completion of the session, after the Mind Genomics program finishes, SCAS produces a summarization of the results. Within the summarization appear a detailed expansion of ideas, all based upon the five sentences shown in Table 2.

Table 2: The SCAS-generated description of the doctor’s waiting room of 1850

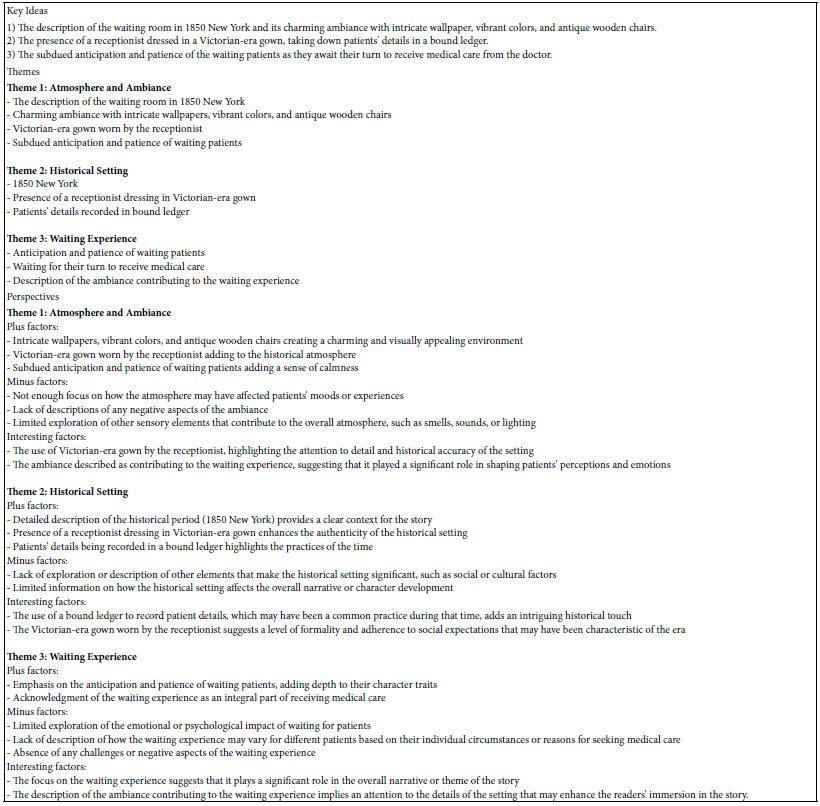

Key Ideas, Themes, and Perspectives

The first set of subsequent analyses present the various ideas, this time expanded. Once again, SCAS returns with an easy-to-read analysis, all based on what SCAS had produced initially in answer to a simple question. Essentially, therefore, SCAS is producing ‘new knowledge’ based upon ‘knowledge’ it had developed simply knowing the topic and the year. Note that the perspectives are different points of view about the topics presented in the section on themes (Table 3).

Table 3: Expansion of knowledge through the key ideas, themes, and perspective regarding those themes

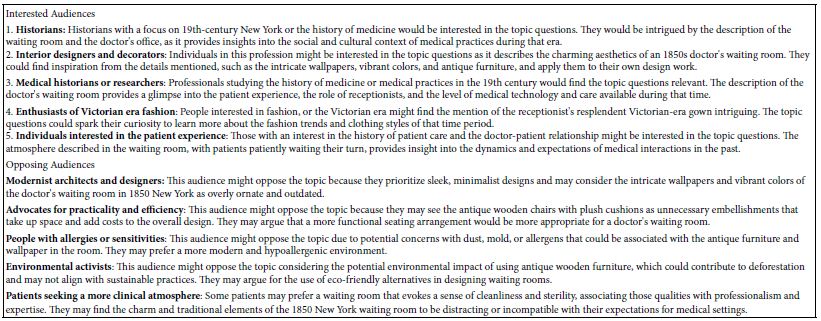

SCAS provides a sense of who would be interested in the materials, and who would be ‘opposed’ to the materials. These appear in Table 4. Once again, it is SCAS which is working on the information it first generated to provide additional information or real points of view.

Table 4: Points of view, interested versus opposed

Steps Towards Innovation (of Knowledge)

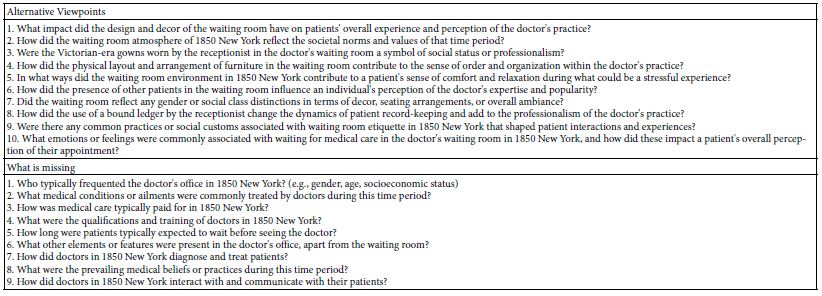

The final summarizations deal with questions and ideas for innovation. For this historical exploration using SCAS there is no ‘innovation’ per se. Rather, the ‘innovations’ comprise questions to answer. These are presented in the sections called ‘Alternative Viewpoint,’ and ‘What is Missing,’ both in Table 5. SCAS does return with ‘innovations,’ but this is the one section in SCAS which as yet cannot put itself into the mind of the 1850 doctor to look at the innovation of that time.

Table 5: Questions to answer, to create new knowledge about the doctor’s waiting room in 1850

Discussion and Conclusions

The objective of this paper is to explore how deeply one can ‘flesh out’ an otherwise modestly interesting topic, the doctor’s waiting room, although a topic which has received attention in the popular literature [6]. There is a relevant academic literature dealing with the history of doctor’s offices and their furnishings [7,8]. It is likely, however, that the material being published will interest the experts, whether these experts be those who study the history of interior design [9], or the history of medicine [10]. There is also a developing literature on the additional aspects of the doctor’s waiting room, such as design, content, etc., based upon the recognition that the waiting room is not only a place to store people, but also to make their visit pleasant [11,12], and a chance to teach them [13]. There is always a need for solid academic work the topic. It is hoped that the simulation efforts with SCAS shown here adds to the bank of knowledge and contributes to the study of the history and sociology of those in the health field and those in the field of interior design.

The real opportunity presented in this paper emerges in the world of education. The use of Mind Genomics, and especially its easy use AI embodied in SCAS can result in a great deal of relevant information being produced in minutes, with the student able to modify the requests to SCAS, and in turn get new information in virtually seconds. Afterwards, there is the major contribution to education products from the SCAS-based summarization of the information. Each iteration, the effort taking about 30 seconds per iteration, is returned with a full summarization, one Excel tab for each iteration. A student excited about the prospects, can work for 30 minutes, generating a great deal of information, with the nature of the requested information dynamically changing according to the instructions written into the squib by the user, in this case the student. One can only imagine the level of excitement as the student works with SCAS and Mind Genomics a coaches, teaching the study many things in dept, and actively interacting with the student who wants to explore the topic in different ways.

A question that can be posed is how does this AI image of a doctors waiting room across the eras, past and future, coalesce with reality? One thing that can be considered in the current and future eras is the post-COVID 19 world where telehealth and social distancing has become the norm, particularly in healthcare settings. We therefore must consider the potential future of waiting rooms with the emergence of telemedicine as less crowded [14].This is important when we consider the impact of COVID on the layout of waiting rooms, with aspects such as social distancing, spacing the time between appointments in order to prevent crowded waiting rooms, and so forth. The emergence of ancillary healthcare personnel, from the licensure of higher and higher rankings in nurse practice levels, as well as the introduction of physician assistants, have made the visit to the doctors’ office a place where there could potentially be more individuals working at the back end than patients waiting in the front.

A more casual flair is also being approached in medical offices, from patients to healthcare workers alike, with a “casualization of the workforce” occurring [15], keeping in line with recent trends in society as a whole. This casualization may likely show itself in the change of the patient waiting room, from a room psychologically separate from where the medical professionals work to simple part of a continuum of space, with far less psychological separation. This change will manifest the evolving change in power of dominance by the medical professional over the patient to one of cooperation and collaboration. One need only see the change from the formal living, dining and kitchen spaces of traditional homes to their blending in new homes, as designed by forward looking architects with their forward-looking clients.

References

- Moskowitz HR (2012) ‘Mind genomics’: The experimental, inductive science of the ordinary, and its application to aspects of food and feeding. Physiol Behav 107: 606-13. [crossref]

- Kalyan KS (2023) A survey of GPT-3 family large language models including ChatGPT and GPT-4. Natural Language Processing Journal, p. 100048.

- Danyun L, Jiun CY (2016) October. Historical cultural art heritage come alive: Interactive design in Taiwan palace museum as a case study. In 2016 22nd International Conference on Virtual System & Multimedia (VSMM) (pp. 1-8) IEEE.

- Staley DJ (2015) Computers, Visualization, and History: How New Technology Will Transform Our Understanding of the Past. Routledge.

- Taylor T (2003) Historical simulations and the future of the historical narrative. Ann Arbor, MI: MPublishing 6: 2.

- Tanner LE (2002) Bodies in waiting: representations of medical waiting rooms in contemporary American fiction. American Literary History 14: 115-130.

- Gainty C (2019) Why Wait? Modern American History 2: 249-255.

- Waltz M (2016) Patient Patients: An Ethnography of Medical Waiting Rooms. Case Western Reserve University

- Figueroa NI (2016) Culture, gender, and medical waiting rooms: A Kuwaiti case study. Journal of Interior Design 41: 33-46.

- Devlin AS (2022) Seating in doctors’ waiting rooms: Has COVID-19 changed our choices?. HERD: Health Environments Research & Design Journal 15: 41-62. [crossref]

- Berkhout C, Zgorska-Meynard-Moussa S, Willefert-Bouche A, Favre J. et al (2018) Audiovisual aids in primary healthcare settings’ waiting rooms. A systematic review. European Journal of General Practice 24: 202-210.

- Lai JCY, Amaladoss N (2022) Music in waiting rooms: A literature review. HERD: Health Environments Research & Design Journal 15: 347-354. [crossref]

- Maskell K, McDonald P, Paudyal P (2018) Effectiveness of health education materials in general practice waiting rooms: a cross-sectional study. British Journal of General Practice 68: e869-e876. [crossref]

- Swicki B (2021) “The future of the waiting room, and how telemedicine and mobile health could change it”, Healthcare IT News.

- Taub P (2001) The trend towards casual address and dress in the medical profession. Virtual Mentor 3: 169-171.