DOI: 10.31038/AWHC.2021431

Abstract

We present a new approach to understand the importance of aspects of shopping behavior, focusing the empirical portion of the paper on the multiple attributes of shopping for home furnishings. Respondents evaluated different combinations of 36 descriptive elements of the shopping experience, doing so in five different studies, each pertaining to one product (bed sheets, decorator pillows, drapes, table cloths, towels, respectively). The ratings were deconstructed into the part-worth contribution of each of the 36 elements. Clustering the 622 respondents into five groups (mind-sets) showed that four of the five mind-sets valued similar features of the shopping experience (assortment, convenience price), but in different rank orders of importance. We suggest that when the topic combines both the experience and the product, mind-set segmentation may not reveal polar opposites, but rather gradations of what is really important. There may be fundamentally different ways of when people thinking about thinking about the combination of experience + product versus thinking separately about product or experience.

Introduction

During the past two decades author HR has explored the use of Mind Genomics as a way to understand the underlying criteria by which people make decisions. Rather than working from a top-down framework where individuals are assigned to clusters based upon the pattern of responses to different aspects of life [1], Mind Genomics works at the granular level, assigning people to clusters or mind-sets based upon the patterns of reaction to description of specific situations, and specific products. Mind Genomics can thus be seen as an inductive approach to understand the world, an approach which does not prescribe a specific pattern, but which simply organizes responses to a limited part of a person’s experience [2,3].

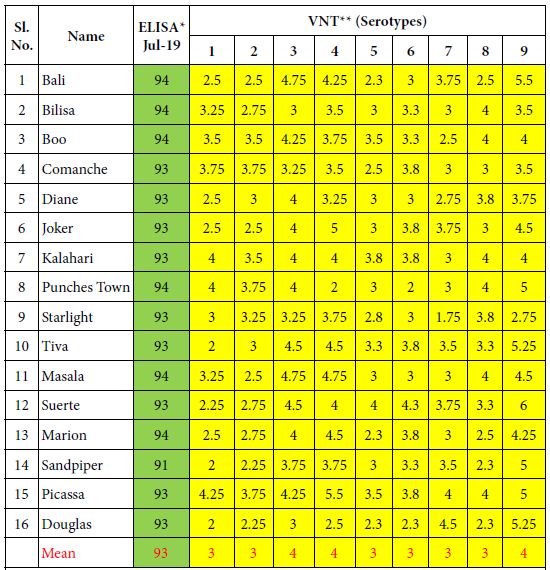

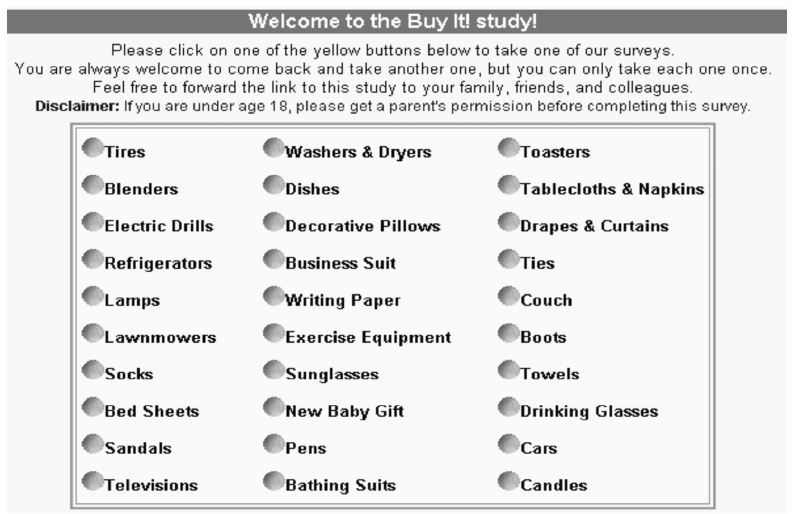

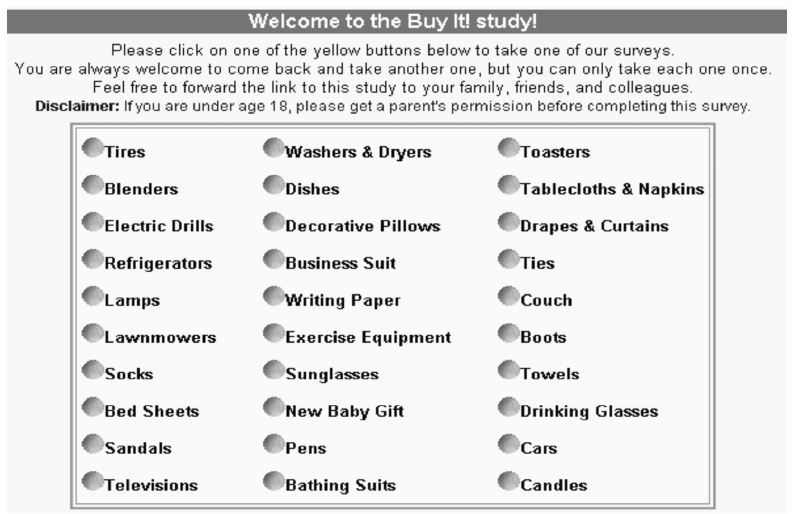

During the early years of the 21st Century, the author and colleagues from the Understanding and Insight Group began work on large scale Mind Genomics studies in specific areas, such as products that one might buy at a store (Buy It!), on different types of insurance (Protect It!), on foods (Crave It!) and on beverages (Drink It!). At the time of these experiments, the idea was to create a series of related studies, with similar elements, but particularized in certain aspects, such as the store where things were sold (Buy It!), or the ingredients that the product included (e.g., Crave It! and Drink It!). The objective was to create the studies, present the respondents with a wall of studies from which to choose (Figure 1), and then analyze the results of the respondents who chose to participate.

One of the interesting patterns to emerge was the existence of general patterns across related studies (e.g., [4]. As an example, for food and beverage, three mind-sets emerge. These were the classics (want what is typical), the elaborates (describe the sensory characteristics or the ingredients), and the imaginers (talk about the experience.) The emergence of three general, overarching mind-sets was interesting, especially when the topic was products in a store. But what about experience? Do we have the same clearly simple, obvious mind-sets emerging when we have a complex experience, involving the person, the action, but a goal (viz., buying a specific product)? The topic is not new, interesting researchers over a period of decades, because it involves what has come to be called multi-attribute decision making [5-7]. Multi-attribute decision making becomes very interesting and attracts attention, both in theory and in practice, when the topic involves shopping [8-10].

The project reported here moved the focus beyond the simple product, and beyond the simple experience, to conjoin them. The topic was explored in the Buy It! study, with 30 different products, shown in Figure 1. Figure 1 shows the array of different products that were studied. In the actual study we had respondent select the product in which they were most interested.

Figure 1: The ‘screen’ showing the different studies for Buy It!

It is now two decades after the data were collected. In the world of science, especially in the world of the hypothetico-deductive, that type of data is considered irrelevant, ante-diluvian, and perhaps other, more negative terms. The data from these ‘attitude studies’ is often considered valuable only when the data are collected ‘today,’ to address ‘today’s issues.’ Yet, the data from Mind Genomics studies have been designed to be archival and to represent the way the mind works, not to necessary to reflect the momentary issues of today. It is with this perspective that we proceed to evaluate the data of two decades ago, data which will prove just as enlightening today as they proved two decades ago, although we will add some new analyses to the old data.

The importance of similar underlying structures cannot be emphasized enough. Too much research in the world of consumer decision making, as well as deep analysis of attitudes, is a one-off, without the possibility of creating a database to understand the mind, either across relative topics or across time, or both. There are simplistic trends evaluations, such the Quinnipiac polls for political opinion, but the polls are simplistic, and do not provide the potential for a deeper analysis, indeed one analysis becoming increasing value with more data collected in a disciplined manner.

The Buy It! Experiment

The data come from Buy It! a large-scale study of more than 4,000 respondents across 30 different products that one could purchase (Figure 1). The It! studies were designed to investigate related topics using a structured set of elements, these elements being particularized to the specific product, but being as similar as possible across the 30 studies. In that way it would be straightforward to compare the data from study to study, product to product, because the phrasing of the element was maintained. Table 1 shows the 36 phrases. These phrases apply to each product. The word PRODUCT is inserted where each study would have the actual product name. The objective is to find the degree to which each phrase drives similarity to one’s ideal shopping experience.

Table 1: The elements. The table shows the elements, with the study configured to bedsheets (replaced by PRODUCT).

|

Question 1: What type of selection does the store feature?

|

| A1 |

We have catalogs that feature sheets of all sizes, blankets, comforters, and bedspreads… page after page of bed linens |

| A2 |

Online or in the store… lots of choices in today’s most popular styles |

| A3 |

Shop at our online store for every kind of (PRODUCT) you can imagine… plus all the accessories you could want |

| A4 |

A discount store featuring all kinds of (PRODUCTS) |

| A5 |

Featuring areas for all types of (PRODUCT)… and many related items |

| A6 |

Lots of very different store environments showcasing the latest trends in (PRODUCTS)… shop the entire day |

| A7 |

Your favorite specialty store… they always seem to have that special (PRODUCT) set you are looking for and all the accessories you need |

| A8 |

A relaxing shopping experience… well designed displays, marble, wood, soft lighting and professional salespeople |

| A9 |

(PRODUCTS) chosen to fit your decorating style, lifestyle, room colors, and personality…to try out at your leisure |

|

How is price described? |

| B1 |

The price is JUST RIGHT … ALL OF THE TIME |

| B2 |

Self-service… no one to get in your way or slow you down |

| B3 |

Start anxious, leave happy … spending that is well worth it |

| B4 |

Offering a GREAT DEAL on the suggested retail price |

| B5 |

An upscale focus makes you feel like you’re part of an exclusive club |

| B6 |

Offering affordable packaging and gift wrapping for your (PRODUCTS) |

| B7 |

Priced a bit more than you would expect – but worth it! |

| B8 |

Shopping with salespeople just like you… who take the time to appreciate your needs! |

| B9 |

Helpful staff, not patronizing … the service is personalized but you don’t feel like you’re being taken advantage of! |

|

How is the shopping experience described? |

| C1 |

A practical and useful store setup… just right for targeted shopping |

| C2 |

Lets you get your shopping done quickly |

| C3 |

One stop shopping … lots of choices, options, brands, colors and sizes |

| C4 |

An easy-to-use gift registry to help you find the perfect gift for someone on your shopping list |

| C5 |

Such a good experience you just have to come back for more |

| C6 |

Takes away the boredom … just when you need it |

| C7 |

When you’re feeling down, shopping lifts your spirits up |

| C8 |

Share the experience with family and friends … get the encouragement when you need it! |

| C9 |

Designer (PRODUCT)s with a range of matching complementary items |

|

What is the nature of the ‘place’ or ‘process’ by which to obtain the PRODUCT? |

| D1 |

At a store such as Wal-Mart, Kmart, or Target PARTICULARIZED TO THE PRODUCT |

| D2 |

At a store such as Sears, JC Penney, or Kohl’s PARTICULARIZED TO THE PRODUCT |

| D3 |

At a store such as Linens & Things or Bed Bath & Beyond PARTICULARIZED TO THE PRODUCT |

| D4 |

At a store such as Macy’s, Marshall Fields, Famous-Barr, L.S. Ayres, Lazarus, Burdines, or Rich’s PARTICULARIZED TO THE PRODUCT |

| D5 |

At Williams-Sonoma PARTICULARIZED TO TH PRODUC |

| D6 |

When ordering by phone or by Internet … friendly customer service helps you through it all |

| D7 |

Simple, easy shopping … no hassles |

| D8 |

Great hours … it may not be around the corner, but it’s still convenient for you |

| D9 |

With a chain of stores all over … buy your (PRODUCTS) anywhere |

The Mind Genomics process differs from the conventional questionnaire or polls. Most researchers as well as respondents are accustomed either to simple questionnaires presenting one-at-a-time ideas, or concepts/mini advertisements, crafted in such a way as to present coherent selling propositions.

The typical approach, questionnaire or polls, presents the 36 phrases to a respondent, one phrase at a time, instructing the respondent to assign a rating to the phrase. In the Buy It! study, the rating would be ‘How similar is this phrase to your ideal shopping experience for the PRODUCT? This popular ‘one-at-a-time’ scaling procedure ends up producing data, but one cannot be clear about the stability of the judgment criterion used by a respondent as the respondent evaluates single element of different types. For one-element-at-a-time, this method makes little sense. For example, can a respondent instructed to rate a single element on the scale of similarity to ideal shopping, actually use the same criterion when applying that scale to the selection (elements A1-A9) versus to price (B1-B9)? There is no context, and the idea of ‘shopping experience’ is hard to understand.

Having the respondents rating lists of ideas is typically done at the start of a project, when there is little idea about what may be important to the shopper, and may not be important. Later, after the lists of ideas have been evaluated, and promising elements chosen, the research will involve the evaluation of, completed, polished concepts. The test stimulus moves from a single idea or set of ideas (so-called promise testing) to a fully executed idea, the concept incorporating the winning ideas into a proposition evaluated by the respondents, and used as a basis for a go/no go decision.

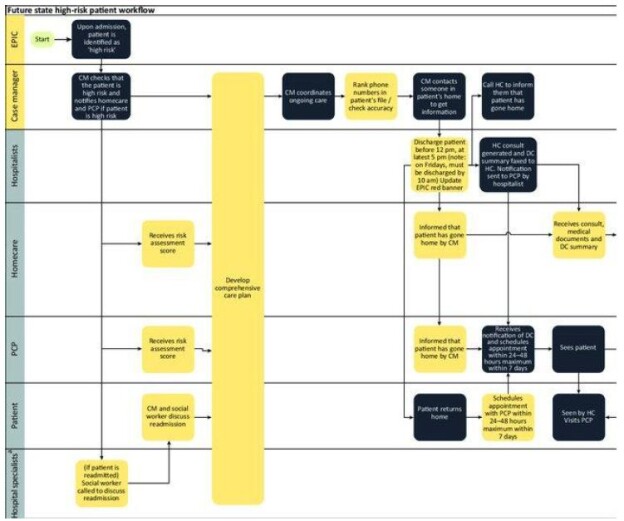

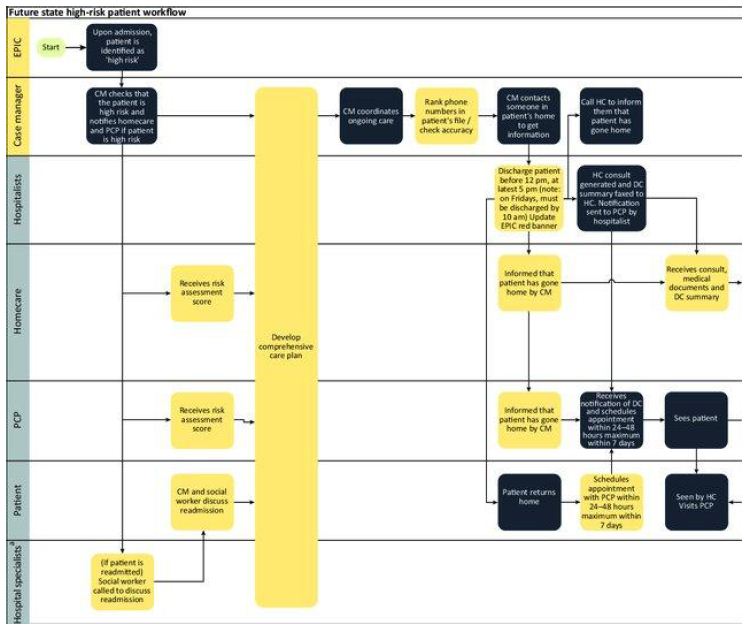

The Mind Genomics approach begins with a different point of view. To get the best answer the respondent should evaluate vignettes, combinations of messages which paint a more realistic word picture of the situation. The vignettes need not be crafted, but should contain different types of elements, put together, presented to the respondent as a single idea, and the whole idea then itself rated. No effort should be made to craft the combination. Rather, the combination should be created according to an underlying rule, the so-called experimental design [11], which specifies the composition of the combination. The combinations should be created so that each element from a category (or question in today’s language) appears approximately equally often with every element from the other categories. This approach, called a permuted design [12] ends up producing a unique 60 combinations of vignettes for each respondent. The permutations mean that the research covers more of the ‘design space.’ The researcher need not know ‘what works’ ahead of the study.

The approach, embodied in the Mind Genomics approach, today available as a do it yourself ‘app’ for a small set of 4 categories or questions x 4 answers or elements, was done with a bit more effort in 2002. However, the actual study was run in the same way, totally automatically after the set-up. For each respondent, the combinations were created automatically by computer and evaluated by the respondent. Each respondent evaluated 60 unique combinations. Each element appeared an equal number of times across the 60 vignettes or combinations, the element appearing in five of the 60 vignettes, and thus absent from 55 of the 60 vignettes. The vignettes themselves comprised 2-4 elements, most one element from each group or question.

The benefit of this seeming ‘blooming, buzzing confusion’ is that the respondents pay minimal attention, but do pay attention, and cannot game the system. Respondents can’t figure out the correct answer. Furthermore, the elements appear in combination, defeating the respondent’s effort to adjust the judgment criterion to match the element.

Another key benefit of the Mind Genomics approach is the use of individual-level experimental design, permutations of the same basic experimental design, but with the combinations differing from one respondent to another [12]. Recall that each respondent evaluated combinations. Across all respondents participating in the same study, it is unlikely that the same vignette will appear twice, and extremely rare that the vignette will appear three times. This feature means that the researcher needs not know the ‘correct answer,’ because the pattern will emerge from the array of the thousands of vignettes evaluate. The analogy is the MRI in medicine, which takes many pictures of the underlying tissue from different angles, and combines them analytically afterwards to provide the picture. The really important thing to know is the elements can be developed quickly, and the process is inexpensive, and welcomes iterations.

The goal of the Mind Genomics study is not the measurement of the combinations. The combinations are only vehicles to embed the elements. Rather, Mind Genomics measures of the strength of each element, as the driver of the ideal shopping experience for the product (ratings 7-9 on the scale).

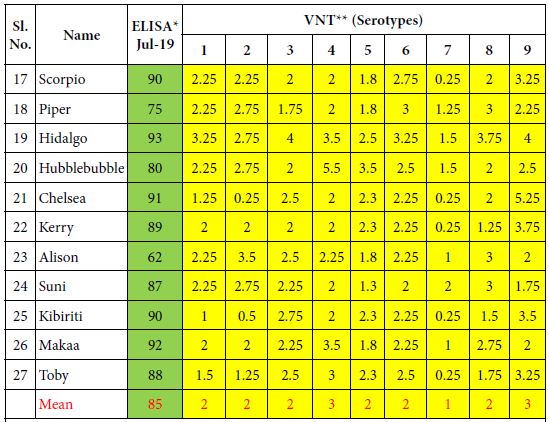

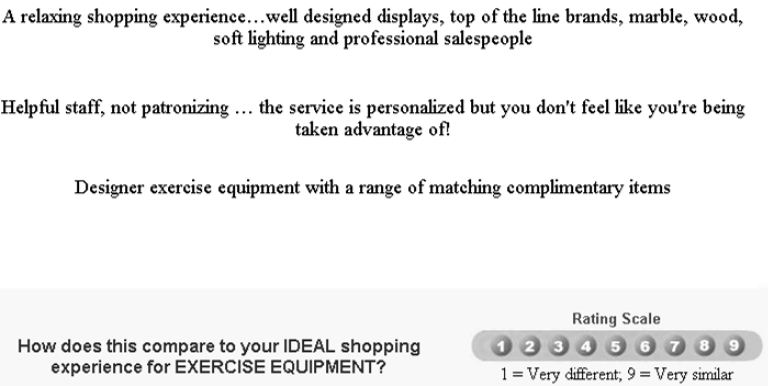

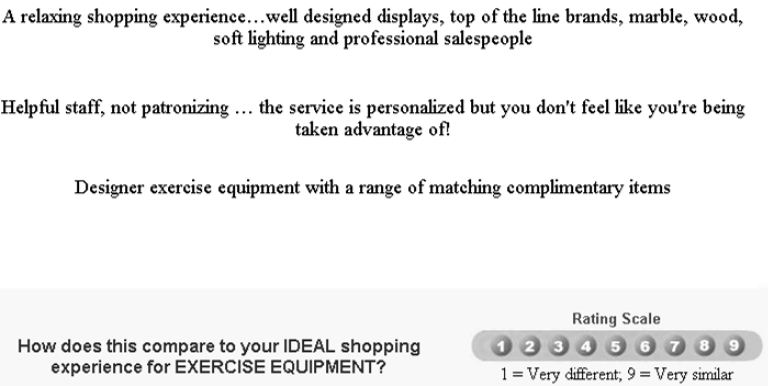

Figure 1 shows an example of one combination, comprising three elements. Figure 1 provides a ‘scenario’ that can be judged. The respondent is still presented with ‘incomplete’ information, an unpleasant fact which irritates many perfectionist marketers, who want a densely written concept to be judged. The reality, however, is that respondents presented with short vignettes such as the one shown in Figure experience little difficulty assigning a rating to the vignette. Figure 1 comprises enough information to describe a shopping experience. No effort is made to polish the combination. The specific product is particularized, so that the third element (Design exercise equipment with a range of matching complementary items) would have the world ‘tablecloth’ substituted for the phrase Designer exercise equipment. The same substitution would be done for the rating scale.

The respondent presented with the vignette in Figure 1 often feels confused. Some significant portion of the time the respondent’s first attempt is to identify the one element that the respondent feels to be important. The respondent will attempt to select that element but become frustrated because there is no place on the screen to select a single element. It is for that reason that the Mind Genomics studies begin with an introduction.

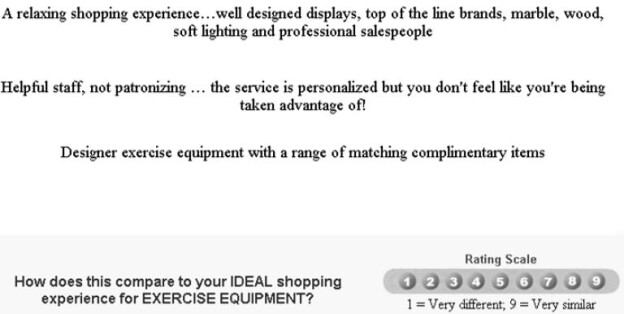

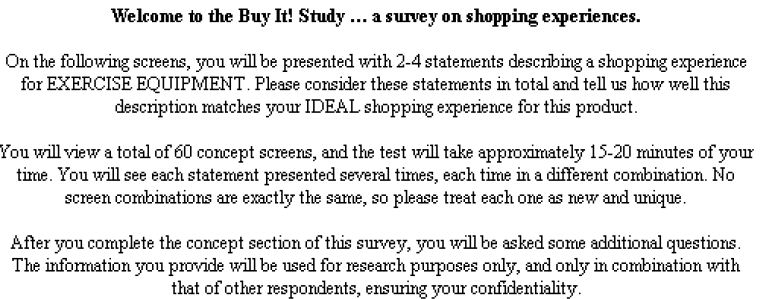

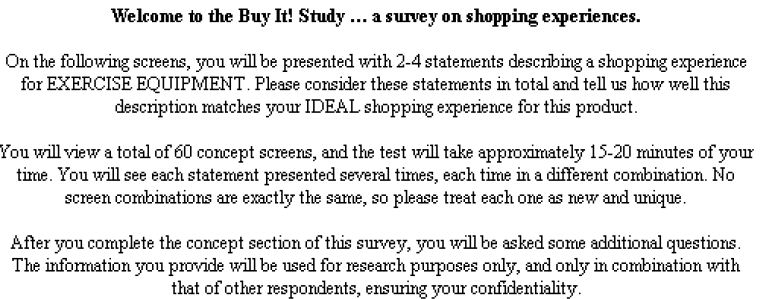

Figure 2 shows the introduction to the study as it was done in 2002. By today’s standards, 2021, 19 years later, the respondent orientation is unnecessarily long. The objective in 2002 was to ensure that the respondent ‘knew’ what the stimuli were (combinations of the elements), that the respondent understood the meaning of the rating question, and that the respondent knew how long the Mind Genomics interview (really experiment) would take (15-17 minutes). As of this writing (2021), the introduction is a line or two, telling the respondent about the topic of the study, and to consider the elements are one idea.

Figure 2: Example of a three-element vignette. The phrase ‘exercise equipment’ would be changed to the appropriate product for the Mind Genomics topic.

Figure 3: The orientation page. The phrase ‘exercise equipment’ would be replaced by the appropriate product.

The study is itself was ‘fielded’ by Open Venue, Ltd., of Canada, which had a large panel of online respondents. The respondents were invited to participate. Those respondents agreeing to participate clicked on the link embedded in the email, were led to the ‘wall’ of studies shown in Figure 1, selected the study, read the introduction, evaluated 60 vignette, and completed large-scale self-profiling classification. Some of the self-profiling data will be referenced in this paper to give a better sense of the nature of emergent mind-sets.

Experimental Design, Modeling, and Clustering

Figure 2 shows an example of one vignette, one combination of elements. Each respondent evaluated 60 different vignettes, a vignette comprising 2-4 elements, at most one element (or answer; Table 1) from a question. The vignettes were created by a systematic plan, experimental design. The underlying experimental design prescribed which combinations a respondent would evaluate. The experimental design was the same for each person, but the specific combinations differed from person to person, according to a permutation scheme [12]. This scheme ensured that the study for any product would cover a large number of possible combinations. The scheme also ensured that no mutually contradictory elements would appear in the same vignette, e.g., two different stores. Finally, the scheme ensured that it would be possible to do complete statistical analyses such as OLS (ordinary least-squares) regression on the results of each separate respondent, a capability that would prove vital to understand the different ‘mind-sets’ of the 622 respondents who would participate.

Each respondent chose one of the studies shown in Figure 1. The data presented here will deal with the results of five studies; bed sheets, decorator pillows, drapes; tablecloths, and towels, respectively. The respondent was presented with the requisite set of 60 vignettes in randomized order, responded to the combination, with the response being on a 1-9 scale. In addition, the respondent completed an extensive self-profiling classification, some of the results from which will be shown at the end of this paper.

The Mind Genomics program (then called IdeaMap®) presented the combination, recording the structure of the combination, as well as the rating. The structure of the combination comprised 36 columns, one column for each of the 36 elements. The coding for a specific vignette comprised a set of 1’s for the elements (columns) which appeared in the vignette, and a set of 0’s for the elements (columns) which did not appear in the vignette. Since the vignettes comprised 2-4 elements by design, across the 36 columns coding the elements, only 2-4 of the columns contained the number ‘1’, and the remaining columns contained the number ‘0’. The 37th column was the rating, later converted to a binary value. The 38th column, corresponding to the newly created binary variable, contained the number ‘0’ plus a very small random number for those ratings which were 1-6. The 38th column contained the number ‘100’plus a very small random number for those ratings which were 7-9. It will be the binary transformation that we will use for the analysis. The very small random number added to each transformed value ensured that the dependent variable would show some miniscule variability in the unlikely case that all of the transformed ratings for a respondent turned out to be either 0 or 100, respectively.

The OLS regression computed this equation for each respondent, storing the parameters in a data file associated with the respondent: Transformed Binary Value = k0 + k1(A1) + k2(A2) … k36(D9). The regression output, therefore, comprises a set of 37 numbers, the additive constant (k0), and numbers, one for element.

At the very start of the research the experimental design ensures ensured that the 36 elements are statistically independent of each other at the level of each respondent. Furthermore, the vignettes are incomplete, with many of the vignettes absent elements from one or two of the questions. This independence and the incompleteness of the vignettes ensures that the coefficients k0-k36 in the foregoing equation have ratio scale properties.

We interpret the additive constant, k0, as the estimated likelihood of a rating of 7-9 assigned (similar to my ideal shopping experience) for a vignette comprising no elements. Of course, the experimental design ensured that every vignette would comprise a minimum 2-4 element. Thus, the reality is that the additive constant is a purely estimated parameter. A baseline, telling us the degree to which the respondent is prepared to respond strongly and positively to a vignette as representing their ‘ideal shopping experience’. In turn, the coefficient shows the driving power of the element to a response of 7-9 when the element is part of the vignette. The additive constant and the coefficients can be added to estimate the percent of respondents who would rate a vignette 7-9, ‘matches my ideal shopping experience’. When constructing new vignettes it is best to use only one element from each of the four questions.

The Standard Analysis for a Single Study and Its Modification to Combine the Five Studies

Mind Genomics studies comprising one topic typically follow a templated analysis, beginning with the creation of equations for total panel, and for subgroups. All of the data for a specific subgroup are placed into the same data set and then a single OLS regression is performed on the full data set. There is no worry that the OLS regression will fail since the permuted experimental design ensures that each individual’s data constitutes the appropriate number of cases (observations) to run a valid regression. Incorporating many respondents with the same experimental design but permuted to create different combinations across respondents simply strengthens the statistical power of the regression.

For this study, however, we looked at five different products. Following a slightly different path, the analysis created an individual model for each respondent. A total of 622 respondents participated across the five studies, creating a database of 622 rows, one row for each respondent. The first data column was the additive constant, the second to the 37th column corresponded to the coefficient of each of the 36 coefficients.

We treated the 622 rows of data (viz., additive constant and coefficients) as one large one data set, despite the fact that there were five products. The elements were similar from product to product. The next step clustered the 622 respondents into mutually exclusive groups, based upon the patterns of the coefficients [13]. For this analysis we removed the five elements corresponding to stores, leaving 31 coefficients. Based upon previous suggestions of at least three major groups of respondents (price, convenience, assortment) we opted to divide the 622 respondents into five groups or clusters, based upon the pattern of their 31 coefficients. The rationale for selecting five was to keep the number of clusters to a minimum, recognizing that there were five different products. Three were known; two additional clusters might reveal new to the world criteria of judgment.

The actual clustering was preceded by a data simplification task. Previous experience revealed that many of the different answers or elements were correlated with each other. To reduce the correlation, we performed a principal components factor analysis on the matrix of 31 variables (viz., all elements but the five stores), and 622 rows (viz., the respondents). The additive constant was not used. The principal components factor analysis revealed 14 statistically independent factors, rather than 31 corresponding to the 31 elements. Each respondent became a set of 14 factors scores, on this ‘reduced space.’ We then clustered the respondents based on their 14 newly created factor scores, rather than on their 31 original coefficients. The approach of clustering is k-means. The measure of distance between respondents is defined as (1-Pearson Correlation, viz., 1-R). When the 14 factor scores of two respondents correlated perfectly (R=1), the distance between them is 0. When the 14 factor scores of two respondents correlated perfectly but inversely, viz. moving in precisely opposite directions (R=-1), the distance between them is 2. The k-means clustering put the respondents into five groups, based upon minimizing the distance between respondents with a cluster, and maximizing the distance between the centroids of the five clusters.

What Stories Do the Coefficients Tells Us for Each of the Five Mind-sets?

The important outcome from the analysis is the ‘story’ told by the elements which score strongly for a mind-set. These are the elements which drive the respondent in the mind-set to say what is being read corresponds to something driving towards an ideal shopping experience. We should keep in mind that the respondent never saw single elements, but only combinations comprising 2-4 elements. Yet, some of the vignettes were rated far more similar to the ideal shopping experience than were others, so the respondents are differentiating.

We begin with some information about the five mind-sets emerging from the clustering. Keep in mind that these clusters were created from the data of all respondents, and so respondents from studies with several products can appear in the same mind-set. The clustering program neither considered the study in which the respondent participated (viz., product), nor considered the additive constant.

Table 2 shows the distribution of the respondents in the five mind-sets created by the clustering program. The five mind-sets are shown in descending order of the strong performing coefficients. That is, each mind-set shows will have a set of elements which score highly, viz., which correspond to the ideal shopping experience. The strong performing elements, shown in subsequent tables, will suggest names for the emergent mind-sets. These names are based upon discovering a possible theme uniting, when possible, the strong performing coefficients in that mind-set

- The five mind-sets are shown in order, based upon the sum of strong performing coefficients (coefficient >=8). This number is shown at the bottom. Mind-Set A shows the largest sum of positive coefficients greater than 8. The sum is 1,006. In contrast, Mind-Set E shows the smallest sum of positive coefficients greater than 8. The sum is 19.

- Each product shows a different number of respondents in every mind-set. The five mind-sets distribute in similar but not identical numbers in each product.

- Mind-Set E shows the greatest number of respondents, 202 out of 622, or one third of the respondents.

Table 2: Distribution of respondents in the five product studies across five mind-sets.

|

Mind-Set

|

A |

B |

C |

D |

E1 |

Total

|

| |

Product & Experience

|

Price Convenience |

Shopping Emotions |

Everything – Choice, Price, Shopping Experience |

High Quality, Choice |

|

| |

Base size of each product (row) in each mind-set (column)

|

| Bedsheet |

30

|

29 |

22 |

27 |

33 |

141

|

| Decorator Pillow |

25

|

25 |

21 |

19 |

42 |

132

|

| Drapes |

19

|

23 |

18 |

28 |

38 |

126

|

| Tablecloth |

25

|

17 |

25 |

17 |

45 |

129

|

| Towel |

17

|

22 |

31 |

20 |

44 |

134

|

| Total |

116

|

116 |

117 |

111 |

202 |

662

|

| Sum of strong performing coefficients (>=8) |

1006

|

571 |

556 |

396 |

19 |

2548

|

The fact that this mind-set shows the lowest sum of strong performing elements (19) suggests that there may be other mind-sets hidden by in Mind-Set E1, failing to surface because the patterns of coefficients of these hidden mind-sets possibly canceling out one another. The extraction of six, seven or even more mind-sets would make this paper unduly long, so the statistical analysis was stopped at five.

Research note: There is no fixed number of clusters of mind-sets to extract in these types of studies. The objective is to create a workable set of different groups, with clearly different patterns. It is quite possible, although statistically nonsensical; to make every person into a mind-set, viz., create 622 clusters. In the same fashion, it is equally nonsensical to create one mind-set and force everyone into that mindset. The best practice is to create a relatively small number of mind-sets which seem to tell ‘different, but interpretable stories.’ The operative words are parsimony (fewer mind-sets are better than many mind-sets), and interpretability (the mind-sets should be coherent, telling a story or suggesting a common theme).

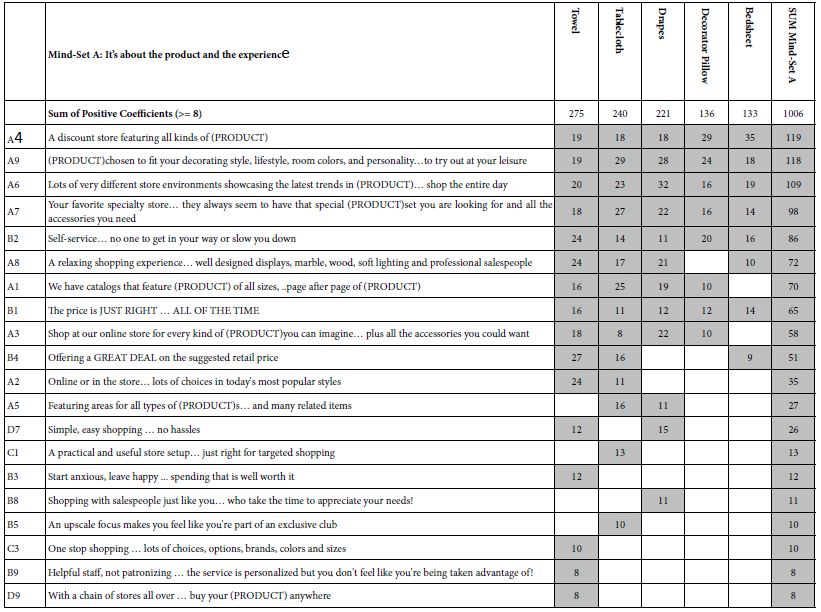

With five different products of the same type, and with 31 elements in the segmentation, the data becomes overwhelming. Patterns cannot be easily seen in this ‘wall of numbers,’ defeating the purpose of the project. To make the analysis simpler, and to allow patterns to emerge. We show only those elements which achieve at least a coefficient of +8 for one or more of the five products. All other cells are blanked out. We will show the data for each of the five mind-sets in a separate table.

None of the mind-sets emerging from the combination of five studies could be described as single-minded. Each of the five mind-sets comprised at least two different aspects, albeit in different patterns as shown below.

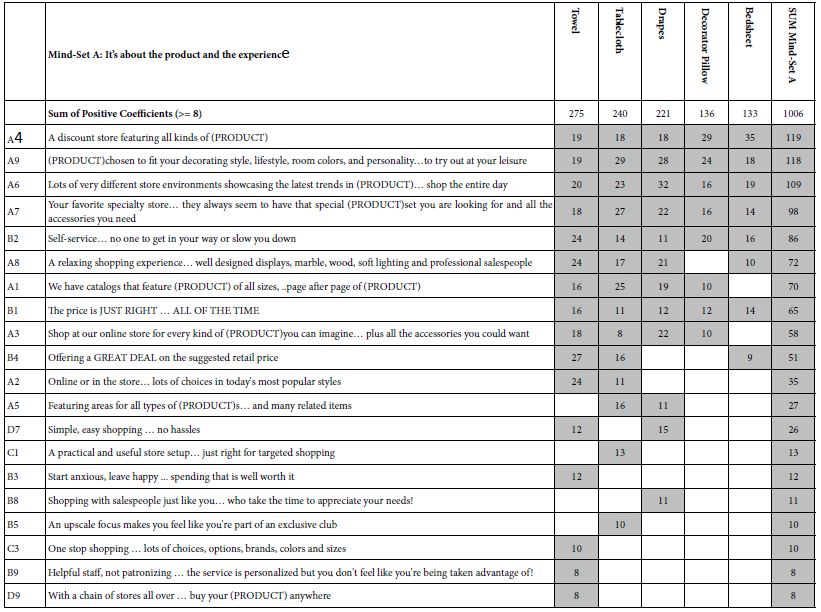

We begin with the strongest performing mind-set, Mind-Set A which focuses on the product and the experience. Mind-Set A is the most likely to feel that the elements portray the idea shopping experience. Yet, Mind-Set A is discriminating. Here is a comparison of the strongest performing positive element versus the weakest performing positive element (Table 3):

A4 A discount store featuring all kinds of (PRODUCT) (Total =119)

D9 With a chain of stores all over. buy your (PRODUCT) anywhere (Total = 8)

Table 3: Strong performing elements for Mind-Set A: It’s about the product and the experience.

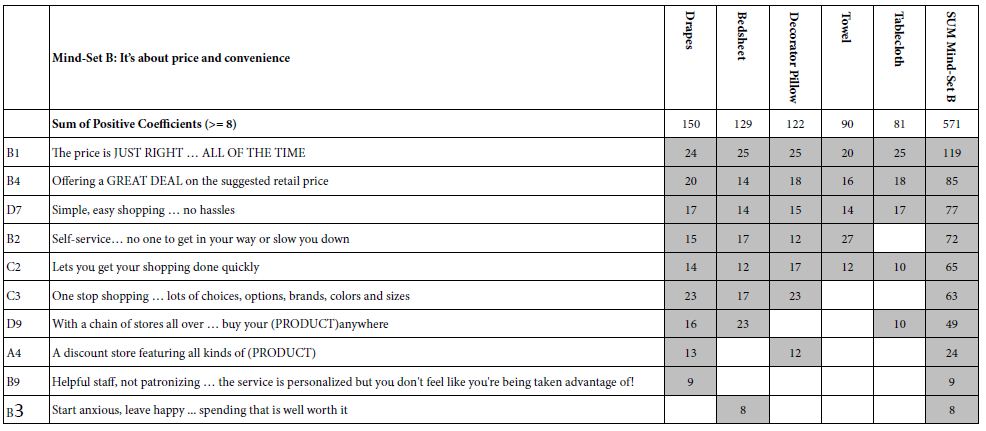

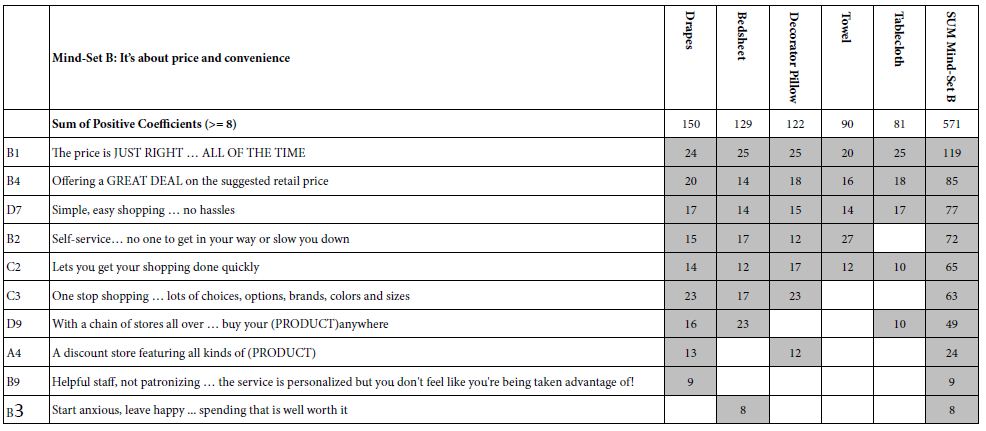

Table 4 presents the results for Mind-Set B, which might comprise those respondents focusing both on price and on convenience, respectively. The orders of the five studies differ, with the highest sum emerging for drapes, and the lowest sum emerging for tablecloths and towels. This difference across the different products suggests an interaction between product and mind-set. Here are the strongest and weakest performing ‘relevant’ elements.

B1 The price is JUST RIGHT … ALL OF THE TIME (Total = 119)

B3 Start anxious, leave happy … spending that is well worth it (Total = 8)

Table 4: Strong performing elements for Mind-Set B: It’s about price and convenience.

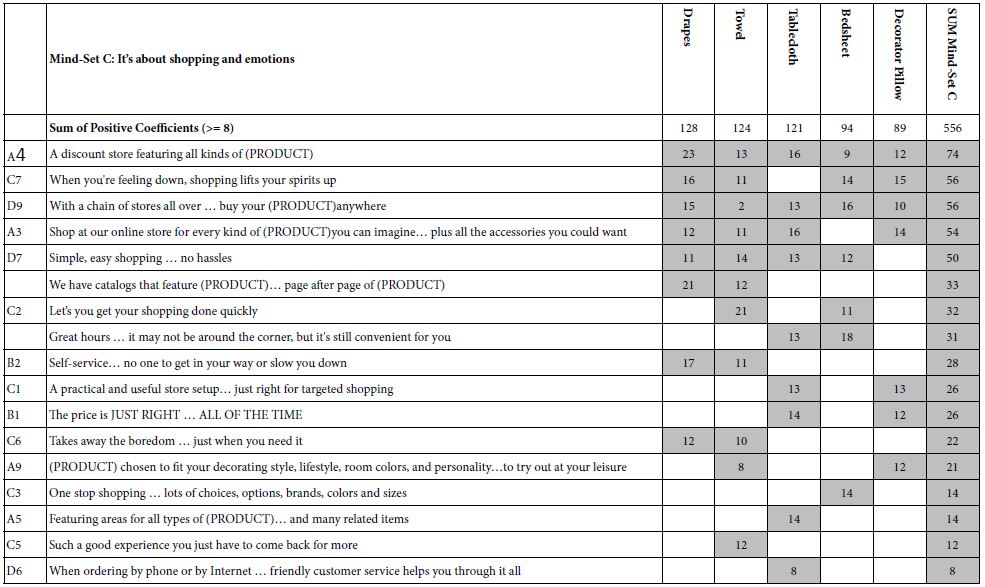

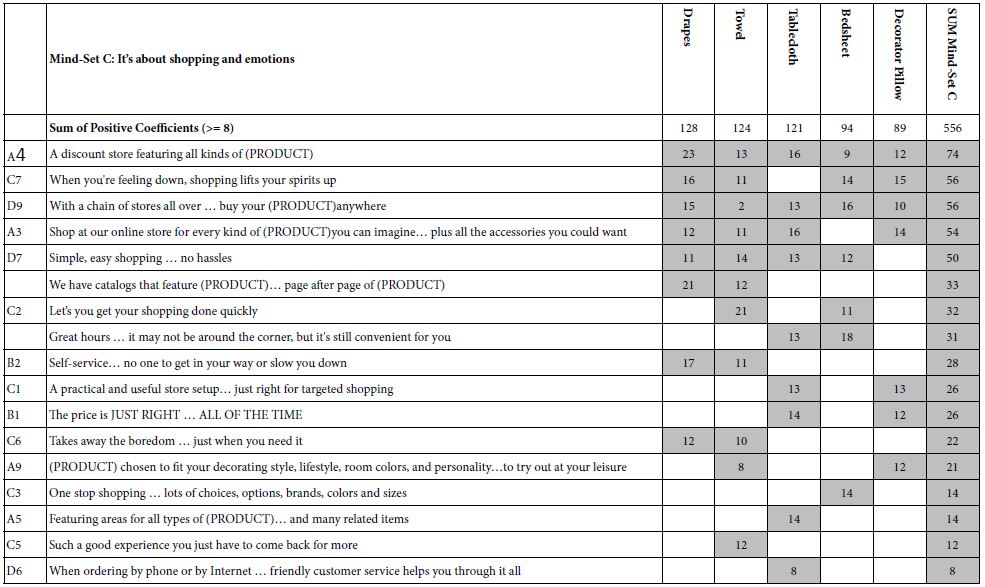

Table 5 presents the results for Mind-Set C, comprising respondents focusing on shopping and emotions, as well as the other aspects such as price and convenience. It is clear from Mind-Set C that the respondents in a mind-set do not focus only on the distinguishing elements (viz., emotion), but rather include those distinguishing elements in the ones important to them. Here are the strongest two and weakest one elements for Mind- Set C. Notice that element C7 introduces emotion as a strong part of the ideal shopping experience.

A4 A discount store featuring all kinds of (PRODUCT) Total = 74

C7 When you’re feeling down, shopping lifts your spirits up Total = 56

D6 When ordering by phone or by Internet … friendly customer service Total = 8

helps you through it all

Table 5: Strong performing elements for Mind-Set C: It’s about shopping and emotions.

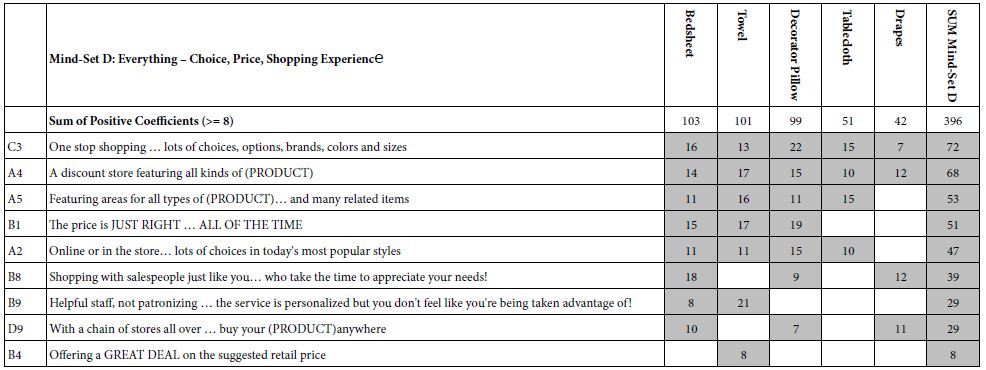

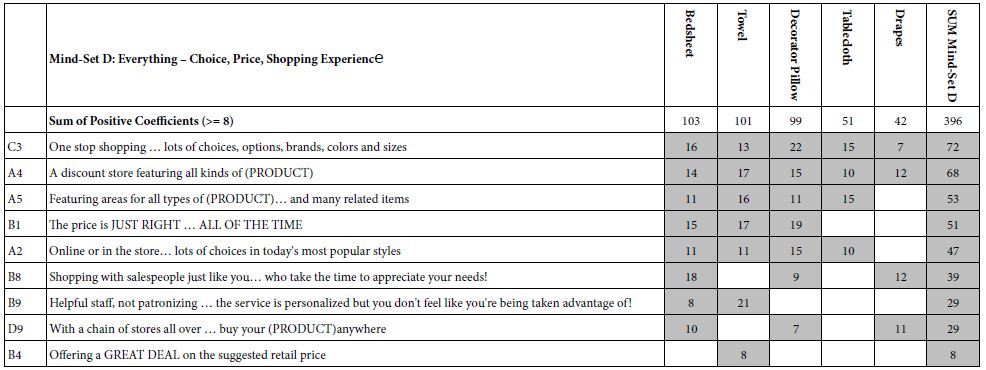

Table 6 presents the results for Mind-Set D, which might comprise those respondents without a specific focus. They appear to react to only nine elements, but these elements come from all of the aspects of shopping: choice, price, shopping, and experience. Here are the strongest and weakest elements from the relevant set of elements.

C3 One stop shopping … lots of choices, options, brands, colors and sizes Total = 72

B4 Offering a GREAT DEAL on the suggested retail price Total = 8

Table 6: Strong performing elements for Mind-Set D: Choice, Price, Shopping Experience.

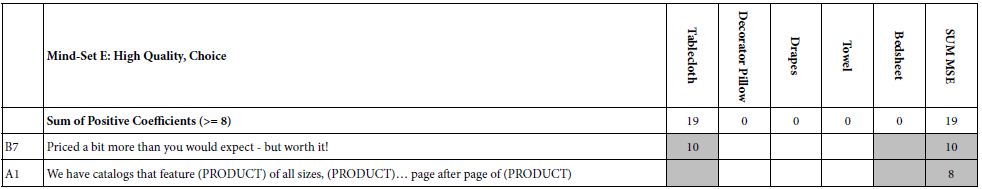

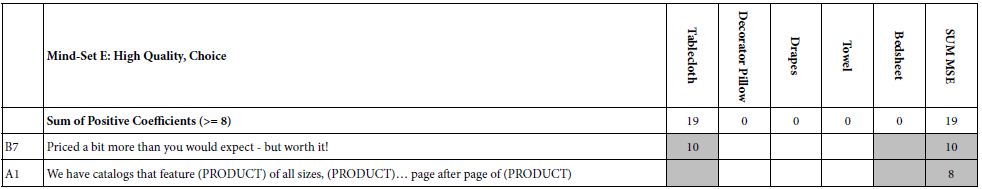

Table 7 presents the results for Mind-Set E, the most numerous mind-set, but the group which responds to only two elements, representing high quality and choice. Mind-Set E might comprise several mind-sets within it, but we focus here only on five mind-sets, and treat Mind-Set E as a single mind-set

Table 7: Strong performing elements for Mind-Set E: Quality and choice.

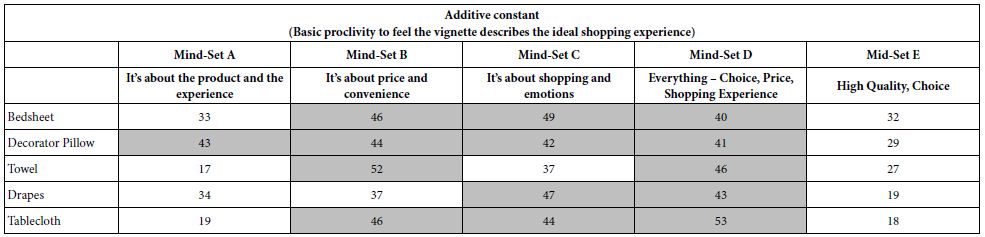

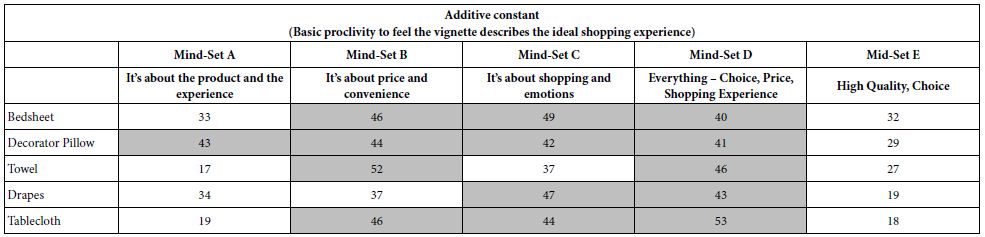

We now move to the additive constant, which was not included in the clustering, but nonetheless plays an important part in the interpretation of the results, and their practical application. The additive constant tells us about the basic proclivity of the respondent in the mind-set to assign the rating (7-9) to a mind-set which is absent any elements. Again we see different patterns (Table 8).

Table 8: The additive constants for the five mind-sets and the five products within each mind-set.

Mind-Set A (It’s about the product and the experience) shows the highest additive constant for the decorator pillow, the one item which can be considered the least necessary item.

Mind-Set B (It’s about price and convenience) show the highest additive constant for bedsheets and towel, and unexpectedly for decorator pillow.

Mind-Set C (It’s about shopping and emotions) show the high additive constant for all products except towel.

Mind-Set D (Everything, chi8ce, price, shopping experience) shows the highest additive constant for all five products.

Mind-Set D (High Quality, Choice) shows no additive high additive constant, and seems to be uninterested in the topic

Can We Find a ‘Golden Message’ Which Works for a Product across Mind-sets?

Thus far, we have in front of us an unusual situation in which there exist mind-sets, but the mind-sets are not opposite of each other, but rather emphasize the same types of messages (price, convenience, assortment), albeit in different orders. The next level of question, and the final in our analysis of messages, the elements of the vignette, is whether there exist a set of messages for each product which promise good performance across the mind-sets. Based upon what we have seen above its quite likely that the strongest performing elements will comprise messages from price, convenience, and assortment, and that the strongest performing messages will do well for all five products.

Table 9 shows the performance of each of the elements across the mind-sets, broken out by product. The e table shows the number of mind-sets out of five mind-sets where the element generates a positive coefficient of 8 or higher. The right half of the table shows the sum of the strong performing coefficients for the element across the five mind-sets, for each product.

Table 9: Performance of each element in terms of generating strong performing coefficients (>=8).

| |

|

Count (Number of mind-sets out of five in which the element performs well (>=8)) |

| |

|

Total |

Bedsheet |

Decorator Pillow |

Drape |

Tablecloth |

Towel

|

| A4 |

A discount store featuring all kinds of (PRODUCT) |

17

|

3 |

4 |

4 |

3 |

3

|

| B1 |

The price is JUST RIGHT … ALL OF THE TIME |

15

|

3 |

4 |

2 |

3 |

3

|

| D9 |

With a chain of stores all over … buy your (PRODUCT)anywhere |

12

|

3 |

2 |

3 |

2 |

2

|

| B2 |

Self-service… no one to get in your way or slow you down |

11

|

2 |

2 |

3 |

1 |

3

|

| D7 |

Simple, easy shopping … no hassles |

11

|

2 |

1 |

3 |

2 |

3

|

| C3 |

One stop shopping … lots of choices, options, brands, colors and sizes |

10

|

3 |

2 |

2 |

1 |

2

|

| B4 |

Offering a GREAT DEAL on the suggested retail price |

9

|

2 |

1 |

1 |

2 |

3

|

| A3 |

Shop at our online store for every kind of (PRODUCT)you can imagine… plus all the accessories you could want |

8

|

0 |

2 |

2 |

2 |

2

|

| A1 |

We have catalogs that feature sheets of all sizes, blankets, comforters, and bedspreads… page after page of bed linens |

7

|

0 |

1 |

2 |

2 |

2

|

| A5 |

Featuring areas for all types of bed sheets… and many related items |

7

|

1 |

1 |

1 |

3 |

1

|

| A9 |

(PRODUCT)chosen to fit your decorating style, lifestyle, room colors, and personality…to try out at your leisure |

7

|

1 |

2 |

1 |

1 |

2

|

| C2 |

Let’s you get your shopping done quickly |

7

|

2 |

1 |

1 |

1 |

2

|

| A2 |

Online or in the store… lots of choices in today’s most popular styles |

6

|

1 |

1 |

0 |

2 |

2

|

| A6 |

Lots of very different store environments showcasing the latest trends in bed sheets… shop the entire day |

5

|

1 |

1 |

1 |

1 |

1

|

| A7 |

Your favorite specialty store… they always seem to have that special (PRODUCT)set you are looking for and all the accessories you need |

5

|

1 |

1 |

1 |

1 |

1

|

| A8 |

A relaxing shopping experience… well designed displays, marble, wood, soft lighting and professional salespeople |

4

|

1 |

0 |

1 |

1 |

1

|

| B8 |

Shopping with salespeople just like you… who take the time to appreciate your needs! |

4

|

1 |

1 |

2 |

0 |

0

|

| B9 |

Helpful staff, not patronizing … the service is personalized but you don’t feel like you’re being taken advantage of! |

4

|

1 |

0 |

1 |

0 |

2

|

| C7 |

When you’re feeling down, shopping lifts your spirits up |

4

|

1 |

1 |

1 |

0 |

1

|

| C1 |

A practical and useful store setup… just right for targeted shopping |

3

|

0 |

1 |

0 |

2 |

0

|

| B3 |

Start anxious, leave happy … spending that is well worth it

|

2 |

1 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

1

|

| C6 |

Takes away the boredom … just when you need it |

2

|

0 |

0 |

1 |

0 |

1

|

| D8 |

Great hours … it may not be around the corner, but it’s still convenient for you |

2

|

1 |

0 |

0 |

1 |

0

|

| B5 |

An upscale focus makes you feel like you’re part of an exclusive club |

1

|

0 |

0 |

0 |

1 |

0

|

| B7 |

Priced a bit more than you would expect – but worth it! |

1

|

0 |

0 |

0 |

1 |

0

|

| C5 |

Such a good experience you just have to come back for more |

1

|

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

1

|

| D6 |

When ordering by phone or by Internet … friendly customer service helps you through it all |

1

|

0 |

0 |

0 |

1 |

0

|

| B6 |

Offering affordable packaging and gift wrapping for your (PRODUCT) |

0

|

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0

|

| C4 |

An easy-to-use gift registry to help you find the perfect gift for someone on your shopping list |

0

|

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0

|

| C8 |

Share the experience with family and friends … get the encouragement when you need it! |

0

|

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0

|

| C9 |

Designer (PRODUCT)with a range of matching complementary items |

0

|

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0

|

The data tell a straightforward story. There are four tiers of messages:

Very strong messages, likely appealing to all mind-sets and all products

A4 A discount store featuring all kinds of (PRODUCT)

B1 The price is JUST RIGHT … ALL OF THE TIME

Strong messages, appealing to all mind-sets, but only some of the products

D9 With a chain of stores all over … buy your (PRODUCT)anywhere

B2 Self-service… no one to get in your way or slow you down

D7 Simple, easy shopping … no hassles

C3 One stop shopping … lots of choices, options, brands, colors and sizes

Truly losing messages, performing poorly, possibly well with one product/mindset combinations

B5 An upscale focus makes you feel like you’re part of an exclusive club

B7 Priced a bit more than you would expect – but worth it!

C5 Such a good experience you just have to come back for more

D6 When ordering by phone or by Internet … friendly customer service helps you

through it all

B6 Offering affordable packaging and gift wrapping for your (PRODUCT)

C4 An easy-to-use gift registry to help you find the perfect gift for someone on your shopping list

C8 Share the experience with family and friends … get the encouragement when you need it!

C9 Designer (PRODUCT)with a range of matching complementary items

All other messages.

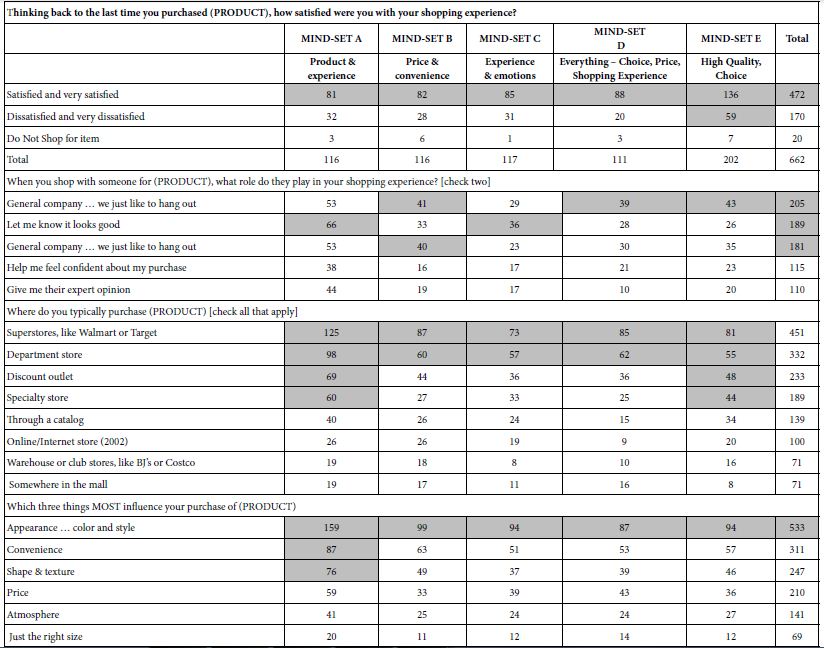

Learning about the Mind-sets by What They Say about Themselves

The foregoing analysis suggested at least five mind-sets about shopping, as well as showing that for each mind-set (except Mind-Set E), the elements which ‘drive’ the perception of an ideal shopping experience come from three major groups; product choice, price, shopping convenience. Do these respondents feel the same regarding the way they describe the shopping?. That is, how do the respondents in a mind-set feel about the shopping experience, and do respondents in the five mind-sets answer differently? Furthermore, if there are segment to segment differences are there a clear story, or are the differences unrelated to the mind-sets?

At the end of the evaluation of the 60 vignettes, the respondents completed a lengthy self-profiling questionnaire on shopping habits, feelings, etc. This is the so-called habits and practices or attitude and usage questionnaire. The question is quite lengthy, often reflecting the researcher’s effort to acquire as much information about the topic as possible.

Table 10 shows the tabulation of the some of the questions by the five mind-sets. The self-profiling questionnaire suggests that the mind-sets are similar in the pattern of their attitudes. In light of previous studies with Mind Genomics which reveal dramatically different attitudes and behaviors of mind-sets, the similarity of patterns in Table 10 beg the question of ‘what is special about the topic of shopping for household furnishings?’

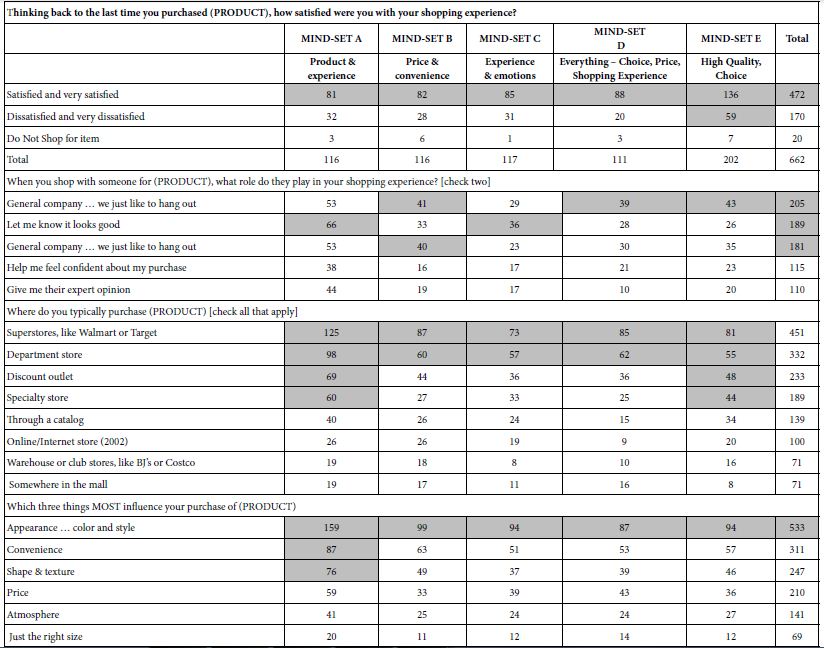

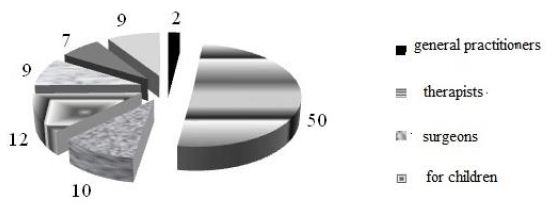

Table 10: How the total panel and the five mind-sets respond four questions taken from the self-profiling questionnaire. All numbers in the table refer to the number of respondents.

Discussion and Conclusions

Most of the previous work using Mind Genomics focused on products, specific experiences, social issues, medical, and legal topics, respectively. Many of these studies revealed dramatically different mind-sets, with the coefficients of the elements clearly revealing the nature of the mind-set. This study on shopping, and a recently published study on the experience of dining in a casual restaurant [14] suggest that the mind-sets which emerge are less polarized.

In the 1980’s a similar observation emerged, not with ideas, but with food products. There were some food products wherein the taste preference segments were dramatic, including pasta sauce, pickles, and coffee [15]. Yet, there was one product, pizza, which showed some sensory preference segmentation, but the segmentation was a matter of degree to which one topping scored higher than other, rather than accept/reject. The explanation proffered at that time was that flavor-driven foods, the segmentation would be polarization. Pizza, however, is not a flavor driven food as much as it is different levels of acceptance of the various toppings. As a consequence, there were differences in the preference for pizza, leading Pizza Hut to modify some of its offerings to better accord with the preferences [16]. That finding for pizza confirmed the results of almost a decade earlier before, for exploratory studies with pizza done with Campbell Soup Company [17].

We surmise from the pizza vs pasta sauce that the shopping experience is not one of ‘flavor’ but rather one of a hierarchy of preferences. That is, a person does not fail to care about price, but care about assortment, and so forth. It is just a matter of which is somewhat more important than others. The nature of the segmentation is not dramatically different. Rather the segmentation reveals the minor differences among people.

The pattern of likes for many products is based upon simple dimensions, such as flavor, and to a lesser extent appearance and texture (mouthfeel). These simple dimensions drive strong likes and dislikes, which emerge in the description of the product. The mind-set segmentation may be too simple, too dramatic, when the focus moves from simple products or simple, relatively one-dimensional experiences to a complex of experiences with clearly different aspects, shopping as well as eating in a restaurant, represent these complex situations. Both shopping, the topic of this paper [18-22] and eating at restaurants [14], there are two aspects making the segmentation less powerful. The first aspect is that which is sought and for which the experience is initiated (the item shopped for, the food served in the restaurant). The second aspect is the dimensions of the experience as it happens. It may well be that fuzzy mind-sets emerge when there are these two-pronged situations, that which is being sought, and that which has to be experienced, separate and parallel to what is being sought.

Acknowledgment

Author Howard Moskowitz wishes to acknowledge the help of the late Hollis Ashman, a member of It! Ventures at the time of the research. Hollis created the study, and put together the basic data from the study results.

References

- Moskowitz HR, Gofman A, Beckley J, Ashman H (2006) Founding a new science: Mind Genomics. Journal of Sensory Studies 21: 266-307.

- Kell DB, Oliver SG (2004) Here is the evidence, now what is the hypothesis? The complementary roles of inductive and hypothesis‐driven science in the post‐genomic era. Bioessays 26: 99-105. [crossref]

- Moskowitz HR (2012) ‘Mind Genomics’: The experimental, inductive science of the ordinary, and its application to aspects of food and feeding. Physiology & behavior 107: 606-613. [crossref]

- Rabino S, Moskowitz H, Katz R, Maier A, Paulus K, et al. (2007) Creating databases from cross‐national comparisons of food mind‐ Journal of Sensory Studies 22: 550-586.

- Chopra K (2014) Study of relationship between utilitarian and hedonic motives and temporal perspective at retail malls. International Journal for Research in Applied Science and Engineering Technology 2: 35-40.

- Van Limburg B (1998) City marketing: a multi-attribute approach. Tourism Management 19: 475-477.

- Zanakis SH, Solomon A, Wishart N, Dublish S (1998) Multi-attribute decision making: A simulation comparison of select methods. European journal of operational research 107: 507-529.

- Milutinovic V, Salom J (2016) Mind Genomics: A Guide to Data-Driven Marketing Strategy. Springer.

- Marmorstein H, Grewal D, Fishe RP (1992) The value of time spent in price-comparison shopping: Survey and experimental evidence. Journal of Consumer Research 19: 52-61.

- Neal WD (2005) Principles of market segmentation. AMA Core Marketing Knowledge: Segmentation, American Marketing Association, New York.

- Lundstedt T, Seifert E, Abramo L, Thelin B, Nyström Å, et al. (1998) Experimental design and optimization. Chemometrics and Intelligent Laboratory Systems 42: 3-40.

- Gofman A, Moskowitz H (2010) Isomorphic permuted experimental designs and their application in conjoint analysis. Journal of Sensory Studies 25: 127-145.

- Likas A, Vlassis N, Verbeek JJ (2003) The global k-means clustering algorithm. Pattern Recognition 36: 451-461.

- Mazzio J, Harizi A, Rappaport SER, Bejarano L, Moskowitz H (2021) Mind Genomics & perception of the restaurant: Homo Emotionalis vs Homo Economicus. Psychology Journal of Research Open 3: 1-8.

- Moskowitz HR, Gofman A (2007) Selling Blue Elephants: How to Make Great Products that People Want Before They Even Know They Want Them. Pearson Education.

- Abbot M (1986) Personal communication.

- Adams A (1977) Personal communication.

- Sarantopoulos P, Theotokis A, Pramatari K, Doukidis G (2016) Shopping missions: Analytical methods for the identification of shopper need states. Journal of Business Research 69: 1043-1052.

- Turley LW, Milliman RE (2000) Atmospheric effects on shopping behavior: A review of the experimental evidence. Journal of Business Research 49: 193-211.

- Vaughn RL, Hansotia BJ (1977) A multi-attribute approach to understanding shopping behavior. Journal of the Academy of Marketing Science 5: 281-293.

- Büttner OB, Florack A, Göritz AS (2013) Shopping orientation and mindsets: How motivation influences consumer information processing during shopping. Psychology & Marketing 30: 779-793.

- Harizi A, Trebicka B, Tartaraj A (2020) A Mind Genomics cartography of shopping behavior for food products during the Covid-19 pandemic. European Journal of Medicine and Natural Sciences 4: 25-33.