DOI: 10.31038/MGSPE.2022223

Abstract

The paper presents a novel way of solving societal problems, combining experimental design of ideas (Mind Genomics), artificial intelligence, and consumer research. The objective is to identify social problems, and then create a mechanism to suggest solutions to these problems, doing so in a way which poses questions, obtains answers, doing so quickly, easily, and inexpensively. The long term objective of the approach is to empower the average citizen to participate in the solution of problems, doing so as an integral part of the effort, and not just a source of complaints, such complaints being processed in unknown fashion, by unknown professionals, too often disappear without really being publicly addressed.

Introduction

A voyage across the literature of public problems, whether this literature is conventional popular literature or academic literature, will continue to reveal study after study detailing the nature of the problem. The material to which the public is exposed varies from virtual ‘hand wringing about how things are’ onto less passionate, more academically focused papers which deal with the problem in a disciplined way. One can be sure, however, that there is rarely a lack of published materials about the problem being reported. One can also be sure, however, that the majority of the writing is given over to descriptions of the problem for the sake of description, and precious little if anything is given over to specific solutions.

The topic of this paper is a small-scale demonstration of what might happen when a group of young people is allowed to select a ‘tough societal problem’, and then use artificial intelligence to help them solve the problem, along with the help of real but a minimal number of human judges (respondents) who evaluate the problem and the solution in a disciplined fashion presented below. The motivation for the actual experiment (or better, the actual ‘experience’) was the desire to implement the steps, and assess the potential for a new way to solicit answers to social problems. The process was to be very rapid (hours), very low cost, knowledge-building, and when possible ‘actionable’, pointing to actions, not just feelings.

Three converging ‘realities’ prompted this paper. The first is the evolution of the new science of Mind Genomics, a tool coming from a synthesis of consumer research method, statistical experimental design, and the ability to work with small and affordable groups of consumers to obtain stable, and often insight-delivering data. The second is the incorporation of artificial intelligence in the Mind Genomics tool, making the creation of intellectually advanced experiments easy and quick to do, often taking 15-30 minutes to set up a study which previously would have taken several hours or even longer. The third is the evolving recognition that in the world of everyday, the effort by scientist to be right creates the situation recognized by Voltaire that ‘the perfect is the enemy of the good’ [1]. It the world of everyday, the better strategy is to ‘satisfice’, not to optimize [2]. We might have better solutions if we improve things in modest, but continuing ways, rather than search around with high-paid consulting talent for the perfect solution, a search which generates wonderful reports, but often hinders progress because the process is inherently filled with barriers. It is much like the heralded ‘stage-gate’ process, which prevents failure at the cost of reducing success because it is a complex, clerically oriented process, designed to minimize risk, rather than maximize opportunity [3].

As will be shown below, the process presented here might be called ‘fast and easy’, or ‘best guesses with a little help from friend and artificial intelligence.’ The goal is to avoid perfection, or even the effort to be ‘right’, but rather get out into the world , get a sense of what is happening, what might work, and what seems to be absolutely ‘off target.’

The Available Tools

The actual study (traffic in Bogota, Colombia) was made possible by two tools, the Mind Genomics suite of tools (www.BimiLeap.com), and the incorporation of artificial intelligence provided by OpenAI LP (2022). Together, these tools made it possible for a group of students in Bogota, at a weekend class, without any experience, to design a study on solving the traffic problem in Bogota, launch the study, and in a few hours receive fully analyzed results. This paper presents their work, more deeply explicated, showing the societal opportunities emerging from the combination of two worlds. The first is world is, Artificial Intelligence, which provides a rich vein of information relevant to the problem, augmenting human thinking by ‘coaching. The second is Mind Genomics to incorporate and measure human judgment in powerful way which, in turn, actually augments Artificial Intelligence.

Mind Genomics

Mind Genomics is the systematic evaluation of how we make decisions about the issues of the everyday. Mind Genomics posits that one can learn a great deal about decision making by presenting respondents (test subjects) with combinations of ideas, these combinations having been set up so that there is an underlying structure. The respondent evaluates combinations of ideas, rather than single ideas alone. The database generated by the Mind Genomics experiment is analyzed by ‘regression modeling’ (curve fitting). The outcome is a measure of the strength of each idea (or element) as a driver of the rating. When presented with this approach, most people wonder why respondents rate combinations, rather than rate each idea or element separately. The answer is that when a respondent rates combinations, it is impossible to guess what is the appropriate or right answer. Furthermore, with a set of combinations the respondent ends up keeping a consistent rating scale. In contrast, when the researcher presents the set of ideas ‘one idea at a time’, it is possible to guess the ‘right answer’. Furthermore when the specific ideas change in their nature (e.g., problems phrases, solution phrases), that rating scale has to change, but the researcher does not recognize that issue of ‘criterion change’, and ends up using the same scale. The strategy of having respondents rate mixtures avoid both ‘guessing the right answer’ and ‘maintains a consistent rating scale across stimuli [4].

Artificial Intelligence Made Possible by Advances in Computation, and Public Availability

By itself, artificial intelligence is a vast ocean of material, whose contents can be accessed, albeit with appropriate tools. We use artificial intelligence within the framework of Mind Genomics to create questions relevant to a topic, and create answers relevant to those questions. Artificial intelligence does not stop there, however, but rather works within a tightly constrained system. It is artificial intelligence which creates information about problems and solutions, that information is then put into the Mind Genomics framework. Artificial intelligence becomes ‘augmented intelligence.’ Rather than allow people to think about problems and solutions by themselves, with whatever knowledge and insights they may bring to a situation, the artificial or augmented intelligence provides additional material for them to use, or acts as coach, providing the material, and helping the thinking [5].

Demonstration – Putting Together Mind Genomics and Artificial Intelligence to Address a Problem

As Mind Genomics evolved it became increasingly obvious that the best way to teach it was by doing it. In the world of medicine this is known colloquially is ‘learn it, see it, do it’ (Cooper, personal communication to HRM, 2022). With Mind Genomics studies, actually setting up and executing a study with as few as 5-10 respondents, taking the better part of 45 minutes to one hour, ends up being the best teacher. Furthermore, the data is ‘rich’, leading to insight, scientific learning, and publishable data which increases knowledge, and may lead to follow on actions. This paper proceeds in that spirit, showing with the steps to set up the study, acquire the data, and then interpret the results. Furthermore, the ‘research effort’ was done with people who had never done this type of work before, whose native language was Spanish, who were confronted with the requirement to identify a problem, and who were given 45 minutes to set up and launch the study. Finally, the effort involved 20 respondents, small enough to be affordable in a school exercise, but large enough to generate quite interesting results, as reported here.

Step 1: Define the Problem

The students who participated in the study had never experienced Mind Genomics. They were challenged by the senior author to think of a very hard societal problem in Bogota, Colombia, indeed a very hard and seemingly unsolved problem. The objective here was to put the new ‘researchers’ into the frame of mind that this exercise would be real, and not simply a marketing research exercise. The topic had to be relevant. The group decided to deal with the problem of traffic in Bogota, Colombia, and how to solve the problem.

Step 2: Create Four Questions Which Tell a Story, and for Each Question Create Four Answers

The questions themselves will never be part of the material shown to the respondent. The purpose of the four questions is to prompt a set of answers to each question. It will be the combinations of these answers that will comprise the test stimuli.

Continuing observation from more than a decade of research with Mind Genomics suggests that it is at Step 2 when the natural discomfort with the process begins to emerge. Although the instructions sound easy, viz., ‘select four questions which tell a story,’ the reactions to the instructions both amuse and concern. Many people appear visibly uncomfortable when asked to ‘fill in the empty space’ of questions. It is simply too different from that to which they are accustomed. People answer questions, not design sets of questions. People may ask one or two questions during the course of a conversation, but the reality of our daily experience is that questions emerge at the spur of the moment, to flesh out a topic, not to create a dialogue or stream of information. It is for the above reason, the resistance to or fear of creating questions, that Idea Coach was developed. Idea Coach utilizes APIs from OpenAI LP.

After the questions are created, the answers often flow freely. A great deal of the effort appears to be the structured thinking needed to solve the problem. It appears that creating the structure is difficult, filling the structure with answers is a great deal easier.

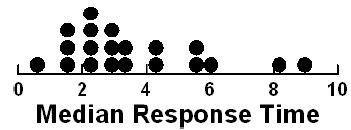

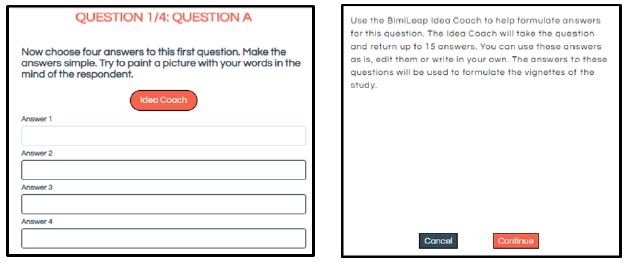

The important thing to keep in mind is that the phrasing of the questions and the phrasing of the answers come from artificial intelligence, with the group of researchers slightly polishing and enhancing the phrases that emerged. If the researcher is unable to provide four questions, the researcher presses the Idea Coach box. A second screen opens up, instructing the researcher to write a short description of the topic. The underlying artificial intelligence provided by OpenAI LP then processes the information, and returns with 10-30 relevant questions, from which the researcher can select up to four questions, insert them automatically, and even edit the selected elements. In addition, the research can, of course, select fewer, providing the researcher’s own questions. In those cases when the researcher fails to find the relevant questions, the researcher can return with the same paragraph submitted to Idea Coach, this time with a different paragraph, re-run Idea Coach, and receive another selection of 10-30 questions. The goal for Idea Coach is to provide the 30 questions each time.

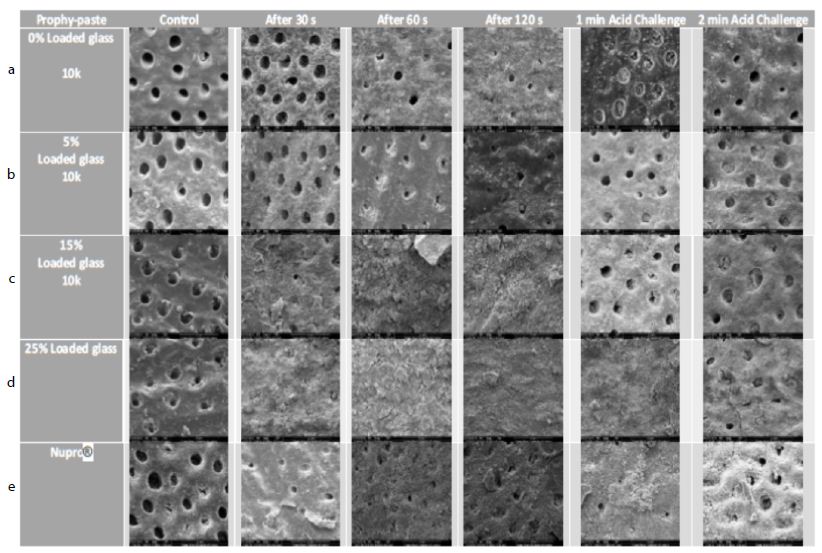

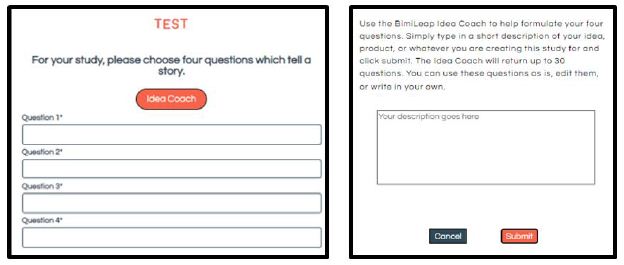

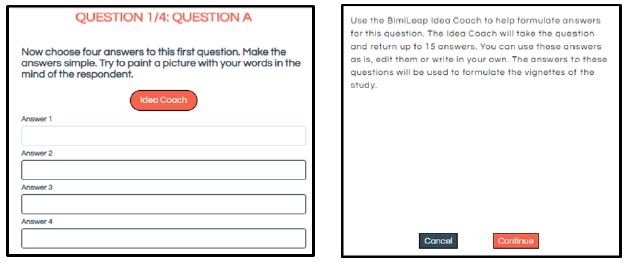

The same capability for AI to provide the necessary text information occurs for the creation of four answers to a question This time, however, the question has already been selected. The researcher does not have the ability to rephrase the question. Rather, the researcher who cannot provide four answers simply invokes Idea Coach, which has been programmed to provide 15 answers. Once again, if the researcher fails to find the appropriate answer, the researcher can invoke Idea Coach again to have another pass through the AI engine. Figure 1 shows the schematic screens requesting questions, and offering the use of Idea Coach. The right panel shows the request to fill in the box with a description of the topic. The artificial intelligence returns with up to 30 questions.

Figure 1: Schematic screen to get questions, and the Idea Coach screen to elicit the help of AI. The researchers must describe the topic and the objective in a short paragraph.

Figure 2 shows the use of artificial intelligence to suggest answers. The left panel shows the request for the answers to a question. The right panel shows the automatic use of Idea Coach to provide 15 answers to the same question. Once again, generating a set of separate answers to each of the four question is simply a matter of pressing two buttons, one on the left to ‘start’ Idea Coach, and one on the right to obtain the 15 answers to the already selected/created question (here the first question of the four).

Figure 2: One of four screens, set up to elicit answers, and the Idea Coach to invoke the help of AI. The AI works automatically, based upon the text of the question that has already been selected and inserted into the system in the previous stage, viz., selecting the four questions.

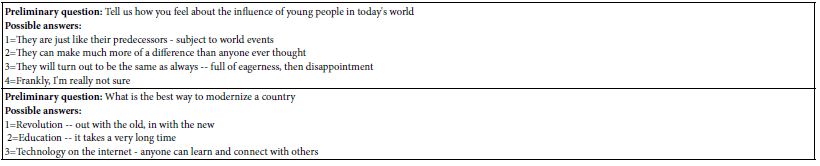

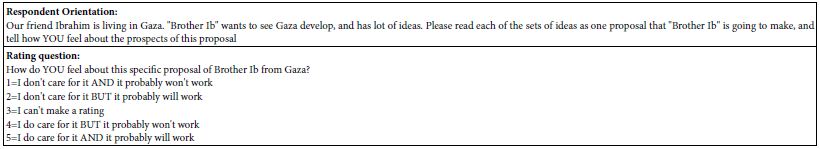

Step 3: Introduction, Rating Question, and Additional Background Information

Moving beyond the creation of the raw materials (questions and answers), the Mind Genomics process proceeds to an orientation paragraph to tell respondents what they will be evaluating, as well as the scale that they will use. Finally, the Mind Genomics process allows the researcher to request additional background information about what the respondent does and thinks about a topic (self-profiling classification; open ended question), and finally the researcher’s own documentation about why the study is being run. Table 1 provides this information, which is recorded in the report provided to the researcher at the end of the study.

Table 1: The information page

|

Study Title

|

Traffic Jam in Bogota

|

| Identification Number of the study: |

11052022.Traffi |

| Date when the study was run: |

(11/05/2022-11/05/2022) |

| Number of respondents: |

20 |

| Purpose of the study (for the researcher, not the respondent): |

Traffic in Colombia, Mexico and Brazil is bad in rush hours, reducing productivity and quality of life of people living in this countries. Is key to find a solution for this problem. |

| Keywords: |

Traffic, traffic jam |

| Study info: |

Tell us about how you feel about traffic jams in cities |

| Self-profiling question: |

What is your interest in traffic? |

| Possible answers: |

1=Never think about it 2=Bother about it but there’s no solution 3=Bother about and I’m looking for a solution 4=I talk with my friends all the time because it bothers me |

| Self-profiling question: |

What are the main ways of transportation used |

| Possible answers: |

1=Bicycle 2=Walking 3=Bus 4=Train 5=Private transportation |

| Rating question: |

In a 5 points scale please choose the phrase below that expresses your feelings. |

| Ratings |

1=Can’t be solved and doesn’t describe my situation |

|

2=Can’t be solved but it does describe my situation |

|

3=I don’t have a point of view |

|

4=Can be solved but does not describe my situation |

|

5=Can be solved and describes my situation |

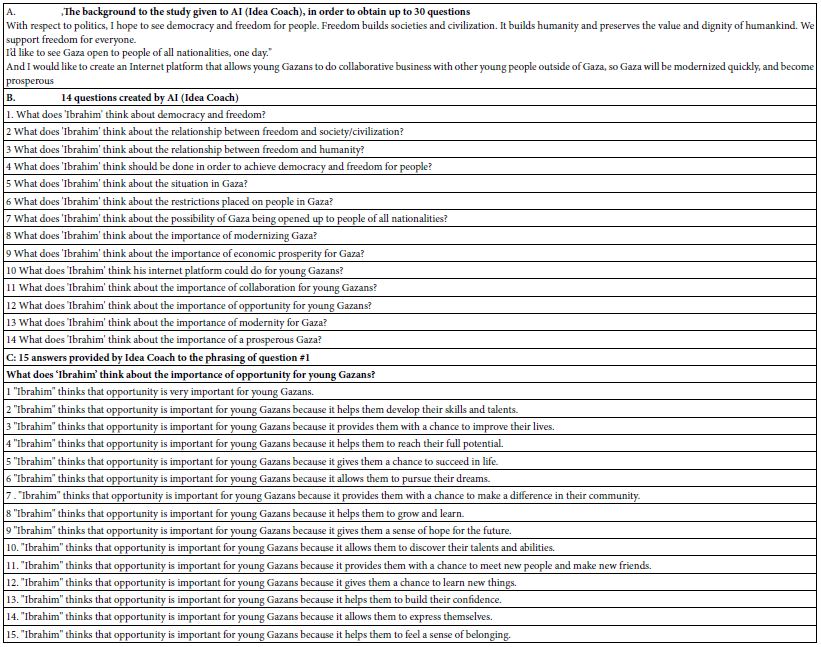

Step 4 – Artificial Intelligence Returns with up to 30 Questions

Within approximately 30-45 seconds, the embedded link to the artificial intelligence system returns with up to 30 questions. Up to four can be selected, dropped into the questions, and even edited afterwards. In the frequent case that the Idea Coach does not generate the ‘best questions’, the researcher can use the same paragraph in Table 1 and try again, or change the paragraph and try again. Within a minute or two the questions are created, usually to the approval of the researcher, who learns more from the exercise than would have been imagined. Table 2 shows the final set of questions, selected by the students, without any guidance.

Table 2: The four questions and the four answers to each question. Most of the text can be traced to Idea Coach, with some text slightly edited as per the preferences of the researcher.

|

Question A: What are some of the potential solutions to reduce traffic congestion in Bogotá? |

| A1 |

Improve public transportation options |

| A2 |

Improve traffic flow through infrastructure improvements |

| A3 |

Implement intelligent transportation systems |

| A4 |

Stagger work hours |

|

Question B: What is the role of the private sector in reducing traffic congestion in Bogotá? |

| B1 |

The private sector can help reduce traffic congestion in Bogotá by providing incentives for employees to use alternative modes of transportation, such as carpooling or telecommuting. |

| B2 |

The private sector can help reduce traffic congestion in Bogotá by working with the government to create incentives for businesses to locate closer to public transportation. |

| B3 |

The private sector can help reduce traffic congestion in Bogotá by developing apps or other technology solutions that help people avoid traffic jams or plan their routes more efficiently. |

| B4 |

The private sector can help reduce traffic congestion in Bogotá by sponsoring car-free days or other events that encourage people to use alternative modes of transportation. |

|

Question C: What is the role of the citizens in reducing traffic congestion in Bogotá? |

| C1 |

Carpooling |

| C2 |

Consolidating trips |

| C3 |

Biking or walking instead of driving |

| C4 |

Avoiding travel during peak hours |

|

Question D: How can public transportation be improved to reduce traffic congestion in Bogotá? |

| D1 |

Increase the capacity of public transportation. |

| D2 |

Increase the use of public transportation. |

| D3 |

Improve the infrastructure for public transportation. |

| D4 |

Improve the marketing of public transportation. |

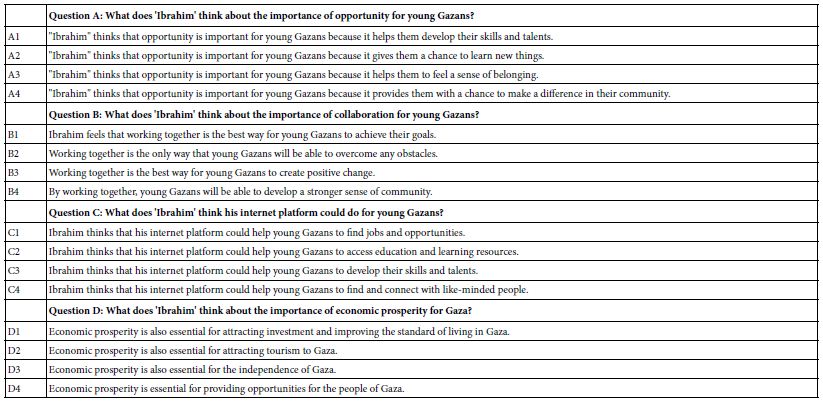

Step 5: Invoke the Underlying Experimental Design to Create Different Sets of 24 Vignettes

As noted above, the Mind Genomics process works by presenting combinations of answers (now called elements). The basic experimental design for the study comprises 24 vignettes, each vignette containing 2-4 elements. To many people looking at the design in simple format (e.g., an Excel file with 24 rows, one per vignette), everything looks random. Indeed, to respondents participating in the study, who evaluate the 24 vignettes, one after another, the experience feels like the baby’s perception of the world, in the words of Harvard psychologist William James, ‘a blooming, buzzing confusion’ [6]. Nothing could be further from the truth as the next paragraphs will show. The goal of the experimental design is to ensure that the ‘correct’ combinations of elements be shown to the respondent. The term ‘correct’ is used here to mean ‘statistically appropriate for analysis by OLS (ordinary least=squares) regression, or simply standard regression analysis [7].

There are two specifications for the experimental design. These are explained in the next two paragraphs.

The first specification is that the design comprise a moderate number of vignettes or combinations of messages, allowing a single respondent to evaluate all of the combinations, which in turn would allow the data from a single individual to be analyzed by OLS regression. This is called a within-subjects design [8]. The actual system is descended from the very popular group of methods called ‘conjoint measurement’ or ‘conjoint analysis’ [9,10]. The popularity of conjoint has extended into traffic planning, anticipating this study [11,12].

For the Mind Genomics efforts, a total of 16 elements combined into 24 combinations has been found to be easiest both for the researcher who has to come up with the questions and answers, and for the respondent, who only has to evaluate 24 combinations, a 3-4 minute task. As an aside, but well worth noting, many researchers want custom experimental designs with unequal sized groups of attributes and level (viz., unequal numbers of answers, with some questions generating many answers, and other questions generating few answers). The objective is Mind Genomics is to present an easy-to-use system, giving solid, robust results, in a way which satisfies many needs. Experience has shown that many of these custom-developed experimental designs really could be turned into a Mind Genomics design with little loss of truly relevant information.

The second specification is that each of the respondents should test different sets of 24 vignettes rather than having all the respondents test the same set of 24 vignettes. The analogy to this is the creation of an underlying picture of human tissue afforded by the MRI (magnetic resonance imaging approach). The MRI takes pictures of the same tissue from different angles. After the fact, the computer program integrates all the picture into a three-dimensional representation. In the same way, the Mind Genomics system covers different combinations, giving a view of the underlying design space. Rather than spending the effort to measure the response to one set of combinations, doing so with many respondents to reduce ‘sampling error,’ Mind Genomics figuratively ‘throws a blanket over the design’, and gets a sense of the strong performing elements (answers), and the weak performing elements. In the end, this approach, permuting the combinations [13] enables the discovery of important versus unimportant elements, as well as the discovery of underlying mind-sets, groups of individuals with different patterns of results, suggesting different ways of thinking about the topic.

Table 3 shows an example of the experimental design for two respondents. The mathematical structure is the same for each respondent, but the two designs are permuted. Each row correspond to one of the 24 vignettes evaluated by a respondent. The matrix comprises 16 columns, one column for each element. When an element or answer is present in the vignette, the cell is coded as ‘1’. When an element or answer s absent from the vignette, the cell is coded as ‘0’.

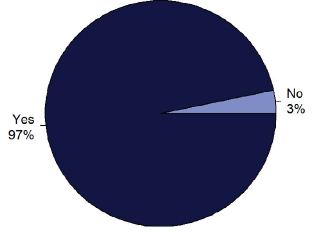

Step 6: Invite Respondents to Participate and Acquire the Ratings

As noted several times earlier in this paper, the objective of Mind Genomics is to create a system which produces knowledge at an industrial scale, with speed, volume, and price all optimized. One of the continuing issues in consumer research is the ongoing decline of participation in studies, along with fraudulent data, such as data produced by ‘bots’ which scour the network to discover opportunities to get paid for participation.

The Mind Genomics process attempts to reduce some of the friction and fraud in the acquisition of respondent data. The first way is to work with a panel supplier with known credibility, which in the case of Mind Genomics is Luc.id Inc., in the United States. Luc.id is not a panel provider but rather an aggregator of panel providers world-wide, a group that has been vetted and accepted by the consumer research community. Thus, the source is credible. The respondents can be specified in terms of number of characteristics, such as age and gender. The panel can be further specified in terms of country, which here was Colombia.

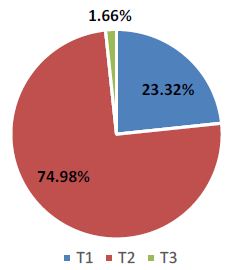

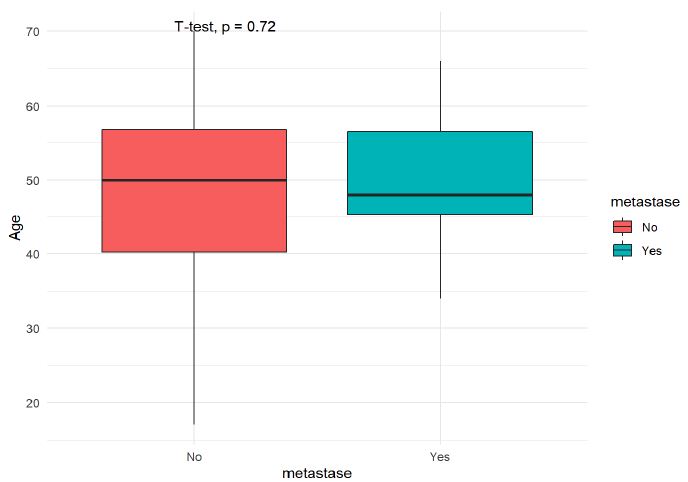

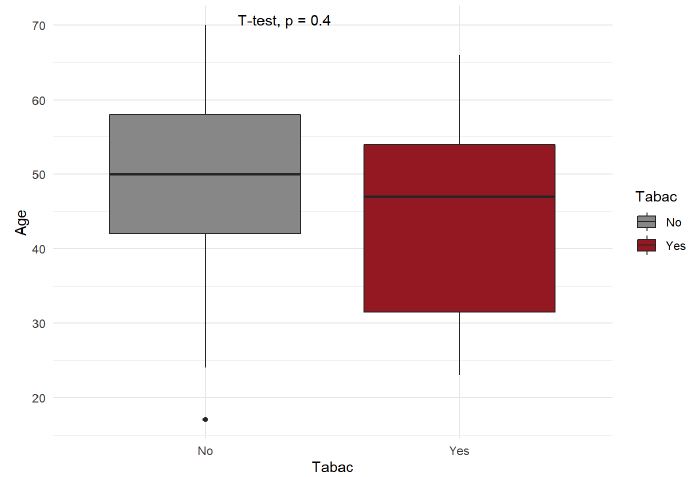

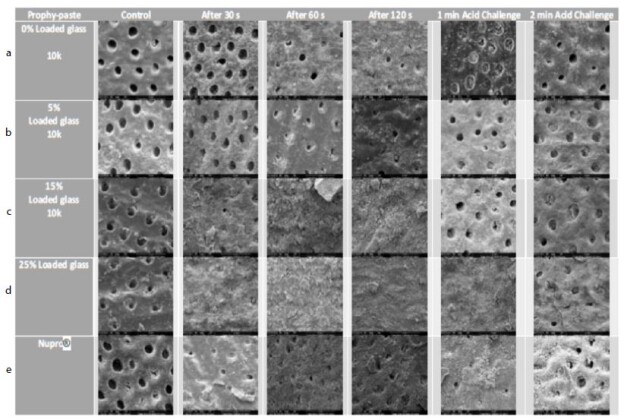

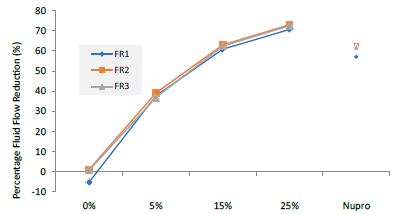

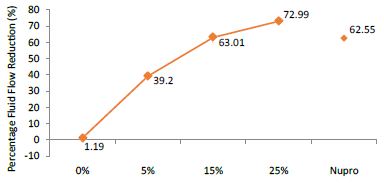

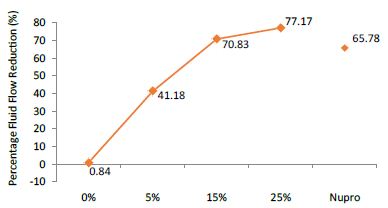

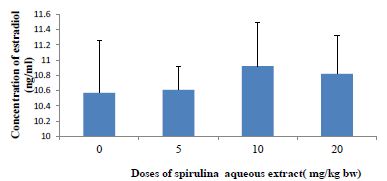

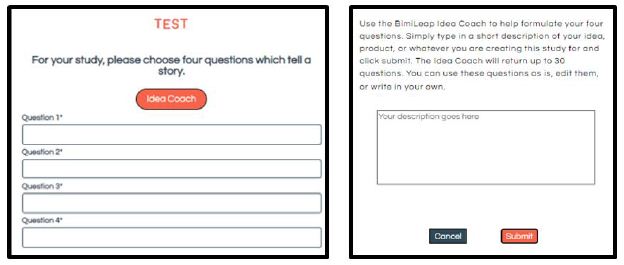

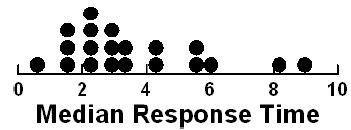

The second way to ensure quality is by measuring the time between the appearance of a vignette and the rating of that vignette. A ‘bot’ would not be able to simulate the necessary response times. Figure 3 shows a histogram of the median response time for each of the 20 respondents across the 24 vignettes. A ‘bot’ would not have produced longer response times, especially response times of a second or more, unless specifically programmed to do so.

Figure 3: Distribution of median response times to 24 vignettes from each of 20 respondents

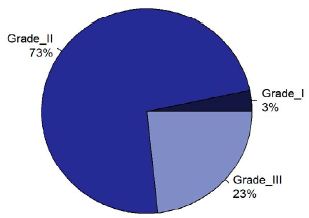

Step 7 – Transform the Ratings to a Binary Scale

Although researchers are accustomed to the believed precision of scales, such as the category or Likert Scale, with each category labelled, once the researcher averages the scale the manager has a difficult time understanding the meaning of the average in terms of practical next steps. As easy as it is to calculate the average, the interpretation of the averages is quite confusing. For example, what does it mean for two test averages to different by 0.58 scale points (e.g., 3.58 vs. 3). The typical manager does not know, and in reality except for the statistics involved, the researcher does not know either. It makes no real sense to say that the averages are statistically different from each other. The underlying statistics may be valid, but the interpretation is difficult.

Consumer researchers have recognized the seductiveness of scales, as ways to measure feelings, but the reality is that most researchers feel more comfortable with percentages, such as ‘70% of the respondents rated Test Product ‘A’ 4 or 5, whereas only 40% rated Test Product B 4 or 5. There is still the discomfort of ‘what does it really mean’, but much of the discomfort goes away after the data are transformed. The transformation is simple; ratings of 4 and 5 are transformed to 100 vs. ratings 1,2, and 3 are transformed to 0. This is called a ‘top down’ transformation. We can also do the opposite, transforming ratings of 1 and 2 to 100, and ratings 3,4, and 5 transformed to 0. This is called a ‘bottom up’ transformation. The transformation from 5-point Likert Scale (1-5) to a binary scale will help us interpret the result.

The five point scale in Table 1 really comprises two scales, allowing us to create the following four binary transformations:

Solvable – Ratings 5 and 4 transformed to 100, ratings 1,2,3 transformed to 0.

Not Solvable – Ratings 1 and 2 transformed to 100, ratings 3,4, and 5 transformed to 0.

Affects Me – Ratings of 5 and 2 transformed to 100, ratings of 1,3, and 4 transformed to 0

Does Not Affect Me – Ratings of 1 and 4 transformed to 100, ratings 2,3 and 5 transformed to 0.

After the transformation to our binary scale, a vanishingly small random number (<10-4) was added to the transformed variable. This prophylactic measure was done ensure that there would be some variation in the dependent variable, so that the ensuing OLS (ordinary least-squares) regression would not ‘crash.’ OLS regression crashes (viz., stops automatically) when the dependent variable (the transformed binary variable) has no variation. There is generally no problem with group data, but when the models or equations are created for individual respondents there are many situations when the respondent ends up assigning all 24 vignettes numbers which either transform to 0 or transform to 100. The prophylactic action of adding the random number ensures that this unhappy event never ends up affecting the OLS regression.

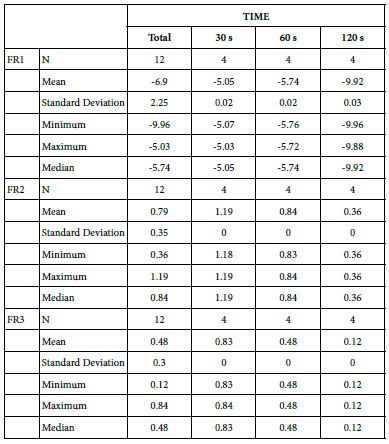

Step 8 – Run a Separate OLS Regression for the Four Transformed Variables, Using Total Panel (All Data)

We want to discover how each of the 16 elements, our ‘answers’ or ‘messages’, drives the binary transformed rating. To discover the driving power of the elements, we subject the data matrix to OLS regression. Regression, often known colloquially as ‘curve fitting’, creates an equation of the form: Dependent Variable = k0 + k1(A1) + k2(A2)…k16(D4) + (Test Order).

The regression equation summarizes how the 16 elements contribute to the dependent variable. The dependent variable in turn, becomes R54 (solvable), R12 (not solvable), R52 (affects me), and R14 (does not affect me). A separate regression equation is estimated for response time versus the variables A1 – D4, and Test Order. The only difference is that the regression equation for response time does not have an additive constant, k0.

We introduce Test Order as a new independent variable. Our focus here is on the possible change of the rating as the respondent proceeds through 24 vignettes, independent of what the composition of the vignettes happens to be.

Step 9 – Present the Results from the Total Panel in an Easy-to-Read Form

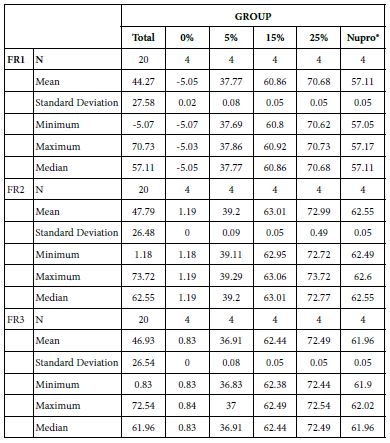

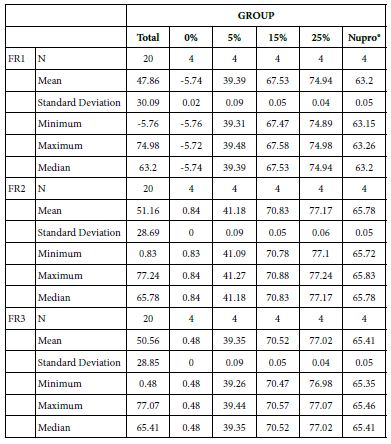

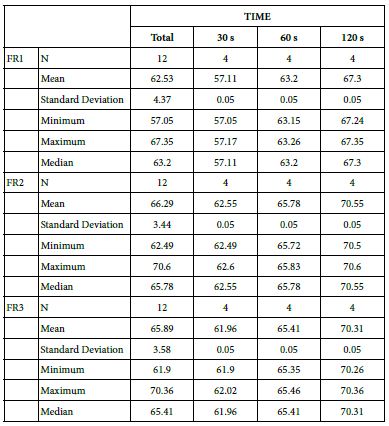

Mind Genomics studies return a great deal of data, once the large matrix of raw data is processed by OLS regression. For every key dependent variable, and selected subgroup, the regression analysis will return 16 coefficients, the 17th number, the additive constant (except for response time). It is critical to eliminate the coefficients which do not tell a story. Consider the data for Total Panel in Table 4.

The additive constant (also called the intercept) in the regression model tells us the conditional probability of the respondent assigning a rating of 5 or a rating of 4 (both denoting ‘solvable’) in the absence of any elements. Of course, the experimental design ensured that each of the 24 vignettes comprised a minimum of two elements or messages, and a maximum of four. Nonetheless, the OLS regression can estimate what would have been the expected value of dependent R54 had there been no elements. Such an estimate emerges from the pattern of the ratings and can be treated as a ‘baseline’. With this in mind, we look at the four additive constants, to get a sense of the baseline:

R54 – Additive constant of 45 suggests that slightly fewer than half of the responses would be positive (solvable)

R12 – Additive constant of 39 means slightly fewer, but a large proportion of responses would be negative (not solvable)

R25 – Additive constant of 21 means that only about of fifth of the responses would be that the situation describes the person

R14 – Additive constant of 63 means that a majority of 63% of the responses suggest that the situation does not describe the person.

Moving now to the coefficients (A1-D4) in Table 4, we see that the table has only positive numbers, many empty cells, and that some cells are shaded. The underlying reason for this is that we learn nothing from negative coefficients. Negative coefficients can either mean the ‘opposite’ of the rating scale or a rating of 3 (I don’t know). The negative and zero coefficients are ambiguous, often misleading because of the rating of ‘3’, and thus can be discarded from the presentation. They are still relevant for the statistics, but need not be interpreted.

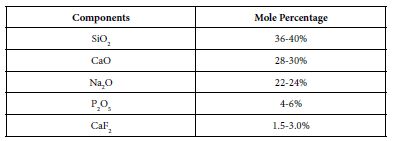

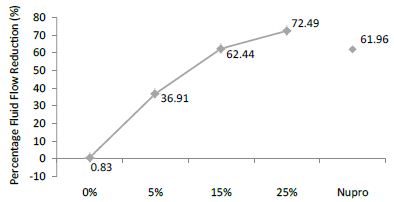

Table 4: Parameters of the models for Total Panel. Only positive coefficients are shown for the four binary transformed rating scale. Strong performing elements (10 or higher) are presented in shaded form.

| |

Total Panel

|

R54

|

R12

|

R25

|

R14

|

RT

|

| |

Solvable |

Y

|

N

|

|

|

|

| |

Describes Me |

|

|

Y

|

N

|

|

| |

Additive constant |

45

|

39

|

21

|

63

|

NA

|

| D4 |

Improve the marketing of public transportation. |

10

|

|

15

|

|

1.6

|

| D1 |

Increase the capacity of public transportation. |

8

|

|

10

|

|

1.1

|

| C4 |

Avoiding travel during peak hours |

7

|

|

|

8

|

1.7

|

| D2 |

Increase the use of public transportation. |

7

|

|

4

|

|

1.0

|

| B2 |

The private sector can help reduce traffic congestion in Bogotá by working with the government to create incentives for businesses to locate closer to public transportation. |

3

|

|

|

|

1.6

|

| C1 |

Carpooling |

|

4

|

7

|

|

1.6

|

| A3 |

Implement intelligent transportation systems |

|

3

|

7

|

|

0.9

|

| A1 |

Improve public transportation options |

|

3

|

|

|

1.4

|

| B4 |

The private sector can help reduce traffic congestion in Bogotá by sponsoring car-free days or other events that encourage people to use alternative modes of transportation. |

|

|

13

|

|

2.1

|

| C2 |

Consolidating trips |

|

|

11

|

|

1.4

|

| D3 |

Improve the infrastructure for public transportation. |

|

|

11

|

|

1.6

|

| B3 |

The private sector can help reduce traffic congestion in Bogotá by developing apps or other technology solutions that help people avoid traffic jams or plan their routes more efficiently. |

|

|

9

|

|

1.8

|

| C3 |

Biking or walking instead of driving |

|

|

5

|

|

1.8

|

| A4 |

Stagger work hours |

|

|

4

|

|

1.4

|

| B1

|

The private sector can help reduce traffic congestion in Bogotá by providing incentives for employees to use alternative modes of transportation, such as carpooling or telecommuting. |

|

|

4

|

|

1.3

|

| A2 |

Improve traffic flow through infrastructure improvements |

|

|

|

|

1.8

|

|

Test order |

0.5

|

-0.5

|

-0.1

|

0.1

|

-0.1

|

The coefficient itself is the ‘additive conditional probability’ that the dependent variable will be selected when the element is inserted into the vignette. Recall that the coefficient emerges from the full pattern of ratings assigned to the 480 vignettes. An easier way to think about the additive constant is that it represent the ‘incremental percent of responses which select the dependent variable when the element is present’.

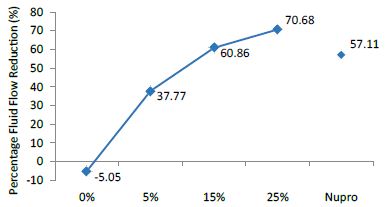

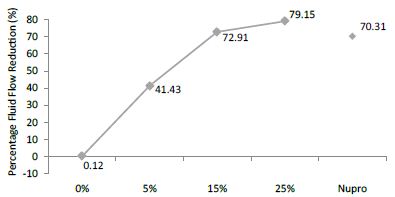

Here are the patterns emerging from the total panel:

Dependent Variable = R54 (Solvable)

Begin with the additive constant of 45, meaning that in the absence of elements, 45% of the responses will be 4/5.

Now look at the coefficients, which have been sorted by the value of coefficient for R54. The coefficients which appear are those respondents feel drive increased solvability of the problem From Table 4 we see the following strong performing elements for the dependent variable, R54 (solvable). Only one of the elements, D4, is a very strong performer, operationally defined as a coefficient of + 10 or higher.

D4 Improve the marketing of public transportation. 10

D1 Increase the capacity of public transportation. 8

C4 Avoiding travel during peak hours 7

D2 Increase the use of public transportation. 7

B2 The private sector can help reduce traffic congestion in Bogotá by working with the government to create incentives for businesses to locate closer to public transportation. 3

Dependent Variable = 52 (Applies to Me)

Begin with the additive constant of 21, meaning that in the absence of elements 21% of the responses will be 5 or 2 (viz., applies to me, whether solvable or not.)

D4 Improve the marketing of public transportation. 15

B4 The private sector can help reduce traffic congestion in Bogotá by

sponsoring car-free days or other events that encourage people

to use alternative modes of transportation. 13

C2 Consolidating trips 11

D3 Improve the infrastructure for public transportation. 11

D1 Increase the capacity of public transportation. 10

Dependent Variable R12 (Cannot be Solved)

This variable has a moderate additive constant (39), a s similar baseline to variable R54 (solvable, additive constant 45). There are no strongly performing elements, however.

Dependent Variable R14 (Does Not Apply to Me)

This variable has a high additive constant (63), suggesting a high baseline, viz., not applicable. There are no strong elements either.

Response Time (RT)

The Mind Genomics program, Bimileap, measures the time elapsed between the presentation of the vignette on the screen and the response to the vignette, no matter which of the five scale points is selected. The regression analysis does not, however, contain additive constant, because the assumption is that the response time would be ‘0’ in the absence of elements.

The deconstruction of the elements into response times is shown at final column, at the far right. The table shows the coefficient for response time for all 16 elements. The coefficients for response time tend to be higher than many coefficient for different topics emerging from studies whose native language is English (viz., respondents living in the USA, Canada, etc.). Given the fact that the respondents live in Colombia, there is the reasonable supposition that the response times might be higher simply because a respondent might require a longer time to read and process the information. Thus, the criterion for an ‘engaging’ message was set at 1.7 seconds.

B4 The private sector can help reduce traffic congestion

in Bogotá by sponsoring car-free days or other events that encourage

people to use alternative modes of transportation. 2.1

B3 The private sector can help reduce traffic congestion in Bogotá by

developing apps or other technology solutions that help people avoid

traffic jams or plan their routes more efficiently. 1.8

C3 Biking or walking instead of driving 1.8

A2 Improve traffic flow through infrastructure improvements 1.8

C4 Avoiding travel during peak hours 1.7

Test Order

The issue has often been raised about Mind Genomics that the data are not stable over time. There are no particular observations to support the contention of instability. On the other hand, one may be able to discover an ‘order’ effect by using order of presentation as an independent variable, along with the presence/absence of the elements in a vignette. Operationally the incorporation of response time into the independent predictors means simply that each of the 480 vignette has a new variable, Test Order, which takes on a value between 1 and 24, dependent upon the order of appearance.

When the analysis was run, an order effect emerged for the dependent variable of for solvability (R54, R12), and for the dependent variable of response time (RT). Over 24 vignettes, from 1 to 24, we expected to see as 12 point increase in the binary rating of R54 (solvability), and a 12 decrease in the binary rating of R12 (not solvable). Over the same range of 24 vignettes, we expected to see a decrease in response time of 2.4 seconds (24 x -0.1 = -2.4). The decrease in response time is not unexpected, and makes intuitive sense. With increasing number of vignettes, the respondent ‘learns’ to graze information quickly, becoming much faster. In contrast, with dependent variables which depend upon judgment, such as ‘solvability’ (R54) there is no priori expectation other than perhaps sensitization to the problem leading to a change in criterion underlying the rating. Order effects approached in this way through Mind Genomics may eventually teach a lot more about the change in judgment criteria for different types of messages.

Step 9 – Uncover ‘Minds’ at the ‘Granular’ Level of the Specific Topic

A hallmark of Mind Genomics is the ability to uncover different ‘mind-sets’ in the population. The term ‘mind-set’ refers to a group of respondents who show the same pattern of coefficients for a specific topic. Thus, Mind Genomics enjoys the distinct benefit of generating specific, testable, viz, actionable data. Individuals who fall into the mind-set may differ radically from one another in the common ways that people are described, namely by who they ARE, what they Do, what they say they BELIEVE, and so forth. By definition, mind-sets emerge from the granular world of everyday experience, making them far more actionable that comparable ways of dividing people using general phrases, not specific phrases.

The division of respondents into these aforementioned ‘mind-sets’ is accomplished in a straightforward manner, a manner which does not require any deep knowledge about the topic. Creating mind-sets is a purely statistical endeavor. Only after mind-sets are created does judgment come into play, for two specific aspects. The first aspect is parsimony. Fewer mind-sets are better than many mind-sets. The second aspect is interpretability. The mind-sets must make intuitive sense, and allow for interpretation, even though the mind-sets are create by methods which are purely statistical In nature. Nonetheless, the mind-set must ‘tell a story’, no matter what their origins.

The clustering follows a standard statistical procedure [14]. The first stage computes the additive constant and the 16 coefficient for each respondent. This ability to create an additive model for the individual is made possible by the up-front creation of 24 vignettes for an individual following the experimental design (Table 3). Each individual respondent has a separate set of 24 vignettes, specified according to the underlying experimental design [15].

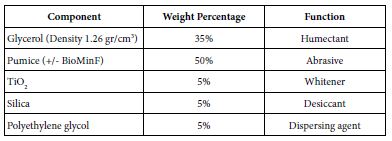

Table 3: The experimental design for two respondents. The design prescribes the composition of vignettes for each respondent. The columns correspond to the respondent number, the number of elements in the vignette, the order of appearance, and then the specific elements appearing (coded by ‘1’) versus absent (coded by ‘0’).

|

Resp

|

# EL

|

Order

|

A1

|

A2

|

A3

|

A4

|

B1

|

B2

|

B3

|

B4

|

C1

|

C2

|

C3

|

C4

|

D1

|

D2

|

D3

|

D4

|

| 1 |

3 |

1 |

1 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

1 |

1 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

| 1 |

3 |

2 |

1 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

1 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

1 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

| 1 |

3 |

3 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

1 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

1 |

1 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

| 1 |

3 |

4 |

0 |

1 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

1 |

0 |

1 |

0 |

0 |

| 1 |

4 |

5 |

0 |

1 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

1 |

0 |

0 |

1 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

1 |

| 1 |

4 |

6 |

0 |

0 |

1 |

0 |

0 |

1 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

1 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

1 |

0 |

| 1 |

4 |

7 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

1 |

0 |

0 |

1 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

1 |

0 |

0 |

1 |

0 |

| 1 |

3 |

8 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

1 |

1 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

1 |

| 1 |

4 |

9 |

0 |

1 |

0 |

0 |

1 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

1 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

1 |

0 |

| 1 |

4 |

10 |

0 |

0 |

1 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

1 |

0 |

1 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

1 |

0 |

| 1 |

3 |

11 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

1 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

1 |

0 |

0 |

1 |

0 |

0 |

| 1 |

3 |

12 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

1 |

0 |

0 |

1 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

1 |

0 |

0 |

| 1 |

3 |

13 |

0 |

1 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

1 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

1 |

| 1 |

3 |

14 |

1 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

1 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

1 |

| 1 |

3 |

15 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

1 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

1 |

0 |

0 |

1 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

| 1 |

4 |

16 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

1 |

0 |

1 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

1 |

0 |

0 |

1 |

0 |

0 |

| 1 |

4 |

17 |

1 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

1 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

1 |

0 |

0 |

1 |

0 |

| 1 |

4 |

18 |

1 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

1 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

1 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

1 |

| 1 |

2 |

19 |

0 |

0 |

1 |

0 |

1 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

| 1 |

4 |

20 |

0 |

0 |

1 |

0 |

1 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

1 |

0 |

1 |

0 |

0 |

| 1 |

4 |

21 |

0 |

1 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

1 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

1 |

1 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

| 1 |

2 |

22 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

1 |

0 |

0 |

1 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

| 1 |

3 |

23 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

1 |

0 |

1 |

0 |

0 |

1 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

| 1 |

3 |

24 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

1 |

0 |

1 |

0 |

0 |

1 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

|

| 2 |

4 |

1 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

1 |

0 |

0 |

1 |

0 |

0 |

1 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

1 |

0 |

0 |

| 2 |

4 |

0 |

0 |

1 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

1 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

1 |

0 |

1 |

0 |

0 |

| 2 |

4 |

3 |

0 |

1 |

0 |

0 |

1 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

1 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

1 |

0 |

0 |

| 2 |

3 |

4 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

1 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

1 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

1 |

| 2 |

3 |

5 |

1 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

1 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

1 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

| 2 |

4 |

6 |

1 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

1 |

1 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

1 |

0 |

0 |

| 2 |

3 |

7 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

1 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

1 |

1 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

| 2 |

3 |

8 |

0 |

1 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

1 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

1 |

| 2 |

4 |

9 |

0 |

0 |

1 |

0 |

1 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

1 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

1 |

0 |

| 2 |

4 |

10 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

1 |

0 |

1 |

0 |

0 |

1 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

1 |

0 |

| 2 |

3 |

11 |

0 |

0 |

1 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

1 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

1 |

0 |

| 2 |

3 |

12 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

1 |

1 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

1 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

| 2 |

3 |

13 |

1 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

1 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

1 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

| 2 |

4 |

14 |

0 |

1 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

1 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

1 |

0 |

1 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

| 2 |

3 |

15 |

1 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

1 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

1 |

| 2 |

3 |

16 |

1 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

1 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

1 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

| 2 |

3 |

17 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

1 |

0 |

1 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

1 |

0 |

| 2 |

2 |

18 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

1 |

0 |

1 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

| 2 |

4 |

19 |

0 |

0 |

1 |

0 |

0 |

1 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

1 |

0 |

0 |

1 |

0 |

0 |

| 2 |

4 |

20 |

0 |

0 |

1 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

1 |

0 |

1 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

1 |

| 2 |

3 |

21 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

1 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

1 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

1 |

| 2 |

3 |

22 |

0 |

1 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

1 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

1 |

0 |

| 2 |

2 |

23 |

0 |

0 |

1 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

1 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

| 2 |

2 |

24 |

0 |

0 |

1 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

1 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

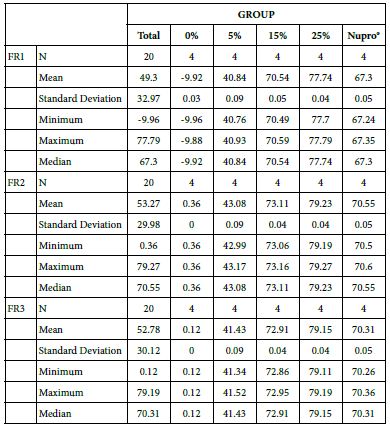

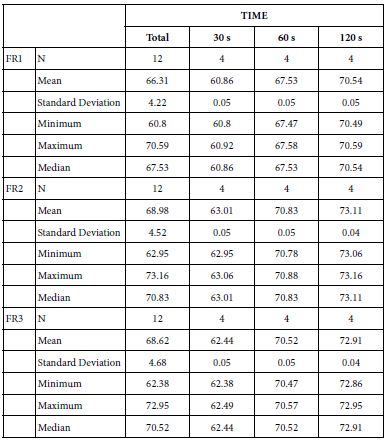

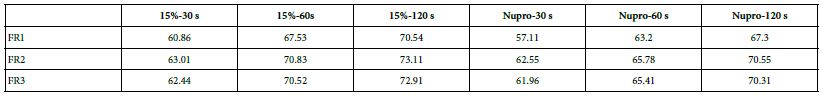

Each respondent’s data, viz., the 24 vignettes and their ratings, are subject to an individual-level OLS regression. This action creates 20 rows of “data”, which will be the input to the clustering program., the first column being the additive constant, the second to the 17th column being the coefficient, with each row corresponding to a respondent. The clustering program computes the ‘distance’ between each pair of respondents, using the value (1-Pearson R). The Person R or correlation coefficient measures the strength of the linear relation between two variables. The ‘distance’ between people based on the Pearson R is defined as quantity (1-R). When two respondents show a highly positive pattern pair of 16 comparable coefficient, then the correlation is close to 1.0, and the distance is 1-1 or 0. When the two respondents show no correlation, viz. no discernible pattern of coefficients when coefficients are plotted again each other in a scattergram, then the correlation is 0, and the distance is (1-0) or 1.0. When the coefficients show opposite patterns when plotted against each, the correlation is -1, and the distance (1-R) is 2 (viz, 1- -1 = 2).

The clustering algorithm puts the respondents into two groups, so that the distance is minimal between the respondents in group, while at the same time the distance between the ‘average person’ in the two groups is as large as possible. The clustering algorithm then repeats the process, this time with three groups, using the same thinking about minimal person to person ‘distances’ within the group, but maximal distance among the three ‘average people’, these three average people computed from the values in the three groups or clusters, respectively. The process of clustering, the aforementioned method of assigning people to non-overlapping groups, is not ‘fixed in stone’, but rather a heuristic. It is a statistically valid manner to uncover patterns in a noisy set of data. The clustering program does not ‘know’ the meaning of the groups, which will be called ‘mind-sets’. It is the job of the researcher to discover the meaning (viz., the criterion of interpretability).

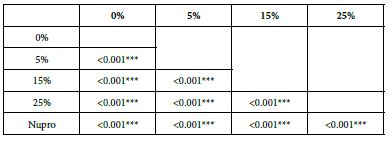

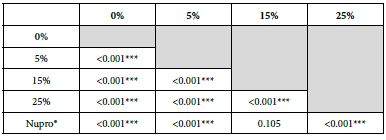

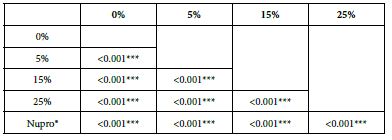

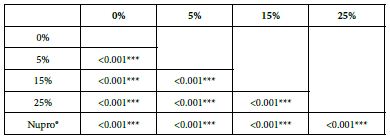

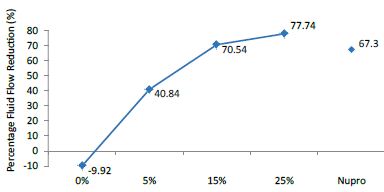

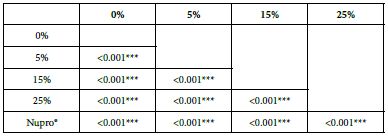

With this introduction, turn now to the two groups created by the k-means clustering program. Once the clustering has assigned the respondents to the two groups, we re-run the equations, using only the data from the respondents in a single group. Table 5 shows the results for cluster 1, or mind-set A, Table 6 shows the results for cluster 2, viz., mind-set B. It is now the researcher’s task to find the patterns, by looking at the elements which score highest in each mind-set, viz., each cluster.

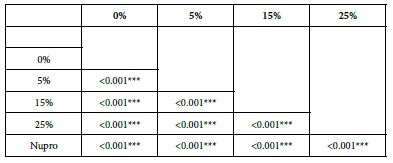

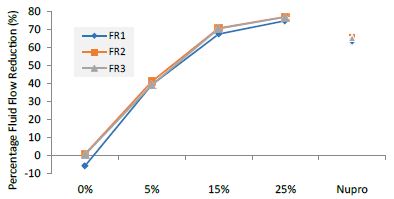

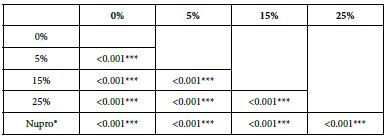

Table 5: Key results for Mind-Set A – Focus on changing one’s own behavior within the system

| |

Mind-Set A – Focus on changing one’s own behavior within the system |

R54

|

R12

|

R25

|

R14

|

RT

|

| |

Solvable |

Y

|

N

|

|

|

|

| |

Describes Me |

|

|

Y

|

N

|

|

| |

Additive constant |

61

|

36

|

39

|

58

|

|

| C4 |

Avoiding travel during peak hours |

13

|

|

|

5

|

1.5

|

| D2 |

Increase the use of public transportation. |

12

|

|

1

|

|

0.7

|

| D4 |

Improve the marketing of public transportation. |

3

|

|

11

|

|

1.4

|

| C2 |

Consolidating trips |

3

|

|

5

|

|

1.1

|

| C3 |

Biking or walking instead of driving |

3

|

|

3

|

|

1.5

|

| D3 |

Improve the infrastructure for public transportation. |

|

6

|

10

|

|

1.2

|

| A1 |

Improve public transportation options |

|

5

|

9

|

|

1.5

|

| D1 |

Increase the capacity of public transportation. |

|

|

9

|

|

0.9

|

| A3 |

Implement intelligent transportation systems |

|

3

|

7

|

|

0.7

|

| B4 |

The private sector can help reduce traffic congestion in Bogotá by sponsoring car-free days or other events that encourage people to use alternative modes of transportation. |

|

8

|

4

|

|

2.6

|

| B3 |

The private sector can help reduce traffic congestion in Bogotá by developing apps or other technology solutions that help people avoid traffic jams or plan their routes more efficiently. |

|

3

|

3

|

|

1.8

|

| A2 |

Improve traffic flow through infrastructure improvements |

|

|

|

|

2.1

|

| A4 |

Stagger work hours |

|

|

|

|

1.2

|

| B1 |

The private sector can help reduce traffic congestion in Bogotá by providing incentives for employees to use alternative modes of transportation, such as carpooling or telecommuting. |

|

|

|

|

1.4

|

| B2 |

The private sector can help reduce traffic congestion in Bogotá by working with the government to create incentives for businesses to locate closer to public transportation. |

|

15

|

|

4

|

2.3

|

| C1 |

Carpooling |

|

|

|

|

1.7

|

|

Test order |

0.7

|

-0.9

|

-0.5

|

0.3

|

-0.1

|

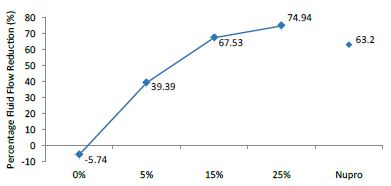

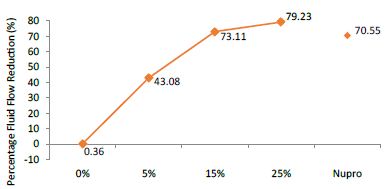

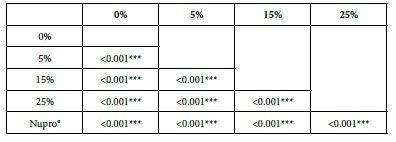

Table 6: Key results for Mind-Set B

|

Mind-Set B: Create system solutions |

R54

|

R12

|

R25

|

R14

|

RT

|

|

Solvable |

Y

|

N

|

|

|

|

|

Describes Me |

|

|

Y

|

N

|

|

|

Additive constant |

14

|

51

|

-5

|

70

|

|

| D1 |

Increase the capacity of public transportation. |

26

|

|

14

|

|

1.4

|

| B2 |

The private sector can help reduce traffic congestion in Bogotá by working with the government to create incentives for businesses to locate closer to public transportation. |

21

|

|

2

|

|

0.6

|

| D4 |

Improve the marketing of public transportation. |

21

|

|

27

|

|

1.9

|

| D3 |

Improve the infrastructure for public transportation. |

18

|

|

18

|

|

2.1

|

| A2 |

Improve traffic flow through infrastructure improvements |

12

|

7

|

14

|

5

|

1.3

|

| B3 |

The private sector can help reduce traffic congestion in Bogotá by developing apps or other technology solutions that help people avoid traffic jams or plan their routes more efficiently. |

11

|

|

18

|

|

2.0

|

| B4 |

The private sector can help reduce traffic congestion in Bogotá by sponsoring car-free days or other events that encourage people to use alternative modes of transportation. |

9

|

|

28

|

|

1.4

|

| A1 |

Improve public transportation options |

7

|

|

|

16

|

1.4

|

| A4 |

Stagger work hours |

3

|

|

8

|

|

1.8

|

| B1 |

The private sector can help reduce traffic congestion in Bogotá by providing incentives for employees to use alternative modes of transportation, such as carpooling or telecommuting. |

3

|

|

5

|

|

1.0

|

| C2 |

Consolidating trips |

|

|

20

|

|

1.8

|

| C1 |

Carpooling |

|

7

|

17

|

|

1.4

|

| D2 |

Increase the use of public transportation. |

|

|

9

|

|

1.2

|

| C3 |

Biking or walking instead of driving |

|

|

6

|

|

2.1

|

| A3 |

Implement intelligent transportation systems |

|

4

|

5

|

|

1.3

|

| C4 |

Avoiding travel during peak hours |

|

|

|

11

|

1.9

|

|

Test order |

0.4

|

0.0

|

0.5

|

0.0

|

-0.1

|

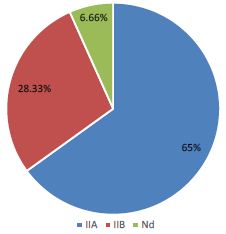

Results for Mind-Set A

Mind-Set A – (base size 8 of 20 respondent) (Table 5). A possible name for this mind-set is Focus on Changing One’s Own Behavior within the System. The reasons for this choice of names are:

Dependent variable R54 (solvable) – additive constant = 61, very high. Strong solvability elements are

C4 (avoiding travel during peak hours)

D2 (Increase the use of public transportation

Dependent variable R12 (not solvable) – additive constant 36 = los. Strong elements militating against solution is the expectation that anyone other than the individual can really solve the problem. A particular negative element, diminishing the hope for solvability, is

B2 The private sector can help reduce traffic congestion in Bogotá by working with the government to create incentives for businesses to locate closer to public transportation.

Dependent variable R25 (describes me) – additive constant = 39. The strongest performers are:

D4 Improve the marketing of public transportation

D3 Improve the infrastructure for public transportation

Response Time – The elements that generate the longest response times are those which propose actions that the government can do. That is, these respondents pay the greatest attention to elements which talk about specific actions that can be done. Of course those elements also tend to be the longest elements, and thus some of the increased response time may be due to the fact that the respondents, non-native speakers of English, are reading long sentences (except for C1, Carpooling, which is one word. Here are the five most ‘engaging’ elements, based upon the response time.

B4 The private sector can help reduce traffic congestion in Bogotá by sponsoring car-free days or other events that encourage people to use alternative modes of transportation.

B2 The private sector can help reduce traffic congestion in Bogotá by working with the government to create incentives for businesses to locate closer to public transportation.

A2 Improve traffic flow through infrastructure improvements

B3 The private sector can help reduce traffic congestion in Bogotá by developing apps or other technology solutions that help people avoid traffic jams or plan their routes more efficiently.

C1 Carpooling

The final row, test order, suggests that as the experiment goes on, and the respondent works her or his way through the experiment with the 24 vignettes. Mind-Set A will feel that the solutions are more solvable (coefficient 0.7 or an increase of almost 17% from start to finish in the solvable rating, R54). They will feel like the problem is less ‘theirs’, with a drop of 12 points in the value of R25 (describes me). Finally, their response time will drop about 2.4 seconds for a vignette from the first rating to the last rating.

Results for Mind-Set B

Mind-Set B (Base size of 12 of 20 respondents) (Table 6). A possible name for this mind-set is Create System Solutions.

Dependent variable R54 (solvable) – additive constant = 14, very low. It is the elements which drive solvability, not simply a change of behavior. Strong solvability elements require cooperation to change the system, perhaps a reason for the low additive constant. These elements are:

D1 Increase the capacity of public transportation.

B2 The private sector can help reduce traffic congestion in Bogotá by working with the government to create incentives for businesses to locate closer to public transportation.

D4 Improve the marketing of public transportation.

D3 Improve the infrastructure for public transportation.

A2 Improve traffic flow through infrastructure improvements

B3 The private sector can help reduce traffic congestion in Bogotá by developing apps or other technology solutions that help people avoid traffic jams or plan their routes more efficiently.

Dependent variable R12 (not solvable) – additive constant 51. However, there are no elements which militate against a solution.

Dependent variable R25 (describes me) – additive constant=-5. These respondents want to see specific solutions. They are not ready to agree ‘at a basic level’ with a high additive constant. Just the opposite – they seem to be ‘show me’ types, consistent with their interest in changing the system, along with changing some behaviors. The strong elements which describe them are listed below. Elements B4, D4 and C2 generate exceptionally high scoring elements, with coefficients of +20 or higher.

B4 The private sector can help reduce traffic congestion in Bogotá by sponsoring car-free days or other events that encourage people to use alternative modes of transportation.

D4 Improve the marketing of public transportation.

C2 Consolidating trips

D3 Improve the infrastructure for public transportation.

B3 The private sector can help reduce traffic congestion in Bogotá by developing apps or \\ other technology solutions that help people avoid traffic jams or plan their routes more efficiently.

C1 Carpooling

Dependent variable 14 (Not me). As expected the additive constant is very high. Mind-Set 2 respondents are more critical. Only two elements perform strongly, however, saying ‘not me’

A1 Improve public transportation options

C4 Avoiding travel during peak hours

Response Time – The elements to engage the respondents in Mind Set B are not necessarily the long elements, but rather the simple types of solutions, of different types. One gets a sense that respondents in Mind-Set 2 are more ‘thoughtful’ about the topic. Keep in mind that Response Time was not a consideration when developing mind-sets

D3 Improve the infrastructure for public transportation.

C3 Biking or walking instead of driving

B3 The private sector can help reduce traffic congestion in Bogotá by developing apps or other technology solutions that help people avoid traffic jams or plan their routes more efficiently.

D4 Improve the marketing of public transportation.

C4 Avoiding travel during peak hours

A4 Stagger work hours

C2 Consolidating trips.

The final row, test order, suggests that as the experiment goes on, and the respondent works her or his way through the experiment with the 24 vignettes, Mind Set B will feel more positive about the solvability of the problem, and about the degree to which they agree with the solution as fitting ‘them’. Both order coefficients are positive, 0.4 for solvable (a 9.6 increase in the expected rating R54 for a vignette), and 0.5 for R25 (a 12,0 increase in the expected rating R25 for a vignette), both across the 24 vignettes. The coefficient for RT, response time, is -0.1, meaning once again a 2.4 second decrease in response time for a vignette, starting with the first vignette, and finishing with the 24th vignette. This decrease in response time is based on the coefficient for Test Order across all 24 response time.

Discussion

The study that we report was done ‘at the spur of the moment’, over a 90 minute zoom meeting, with a class of graduate students in Bogota Colombia, the lecturer for that class (author Herrera), and the senior author of this paper (author Moskowitz), who had been invited to talk about Mind Genomics. Author Rappaport introduced the notion of AI to Mind Genomics, and worked with author Deitel, the programmer.

The initial effort revealed the ease with which one could work with novices to arrive at possible solutions to common societal problems. As the data emerged from the study, so did the realization that a combination of artificial intelligence and human responses could provide a new opportunity to solve common problems. The solutions proffered here are those which emerged after 20 minutes of effort at the start of the project, and about 45 minutes in the field as the project was being completed by the 20 respondents. The respondents were invited by a link in the BimiLeap program which led immediately to the Luc.id system, and in turn secured the respondents in what was designed to be a ‘turn-key system’ for the user.

If we were to look at this study from the point of view of traditional science, we would immediately receive comments that the base size is too small, viz., that there are too few respondents participating to use as a database to decide or to plan. This criticism is often levelled at small-scale studies, primarily because researcher in the world of science are searching for replicable, meaningful result, a noble cause, but one which end up forcing the studies to be long, expensive, and overly focused. One consequence is the effort to be right, to achieve statistical significance, to ensure replicability, subtly forcing the research into the world of ‘confirmation,’ rather than the world of exploration.

This paper stands in contrast to the world of the more thought out studies, the careful delineation of that which is being explored, and the search for what can be defended rather than what can ‘teach’. This paper stands for early stage, simple, low cost exploratory research, research of a type which reveals potentially interesting patterns in nature, patterns which may excite more stringent, focused, larger-sale researcher. Yet, in terms of scientific potential, this paper argues for the value of early stage, but disciplined exploration of a topic, explorations. These studies can form the foundation of a science once the small-scale explorations move to more acceptable studies, viz., simply studies with a much higher base size. In other words, the approach presented here explores nature in the way that early scientists did, to find out ‘what’s going on’ in people’s minds, when people are confronted with realistic situations in society worth addressing, and problems worth solving.

Acknowledgments

The authors are grateful to the students who put together this study on a five-minute notice, and completed the set-up of the study with very little help. This exercise was done in the Consumer Knowledge Management class of CESA’s Master of Marketing Management in November 2022, with the MDM22 group.

References

- Frazer M (2018) Moderation in All Things: Contribution to a Symposium on Dennis C. Rasmussen’s” The Pragmatic Enlightenment: Recovering the Liberalism of Hume, Smith, Montesquieu, and Voltaire”. The Adam Smith Review. 10: 130-138.

- Schwartz B, Ben-Haim Y, Dacso C (2011) What makes a good decision? Robust satisficing as a normative standard of rational decision making. Journal for the Theory of Social Behaviour. 41: 209-227.

- Sommer AF, Hedegaard C, Dukovska-Popovska I and Steger-Jensen K (2015) Improved product development performance through agile/stage-gate hybrids: The next-generation stage-gate process? Research-Technology Management. 58: 34-45.

- Moskowitz HR, Gofman A, Beckley J and Ashman H (2006) Founding a new science: Mind Genomics. Journal of Sensory Studies. 21: 266-307.

- Gawłowicz P and Zubow A (2019) November. Ns-3 meets OpenAI gym: The playground for machine learning in networking research. In Proceedings of the 22nd International ACM Conference on Modeling. Analysis and Simulation of Wireless and Mobile Systems. 113-120.

- Patel A (2015) Person of the Issue: William James (1842-1910). The International Journal of Indian Psychology. 2: 1.

- Pohlmann JT and Leitner DW (2003) A comparison of ordinary least squares and logistic regression (1). The Ohio Journal of Science. 103: 118-126.

- Charness G, Gneezy U and Kuhn MA (2012) Experimental methods: Between-subject and within-subject design. Journal of Economic Behavior & Organization, 81, 1-8.

- Green Paul E, Krieger Abba M, and Wind Yoram (2001) Thirty years of conjoint analysis: Reflections and prospects. Interfaces. 31: S56-S73.

- Mead R (1990) The design of experiments: statistical principles for practical applications. Cambridge University Press.

- Kagaya S and Shinada C (2002) A use of conjoint analysis with fuzzy regression for evaluation of alternatives of urban transportation schemes. In Proceedings of the 13th Mini-Euro Conference, Handling Uncertainty in the Analysis of Traffic and Transportation Systems. 117-125.

- Muraleetharan T, dachi T, Uchida KE, Hagiwara T and Kagaya S (2004) A study on evaluation of pedestrian level of service along sidewalks and at crosswalks using conjoint analysis. Infrastructure Planning Review. 21: 727-735.

- Gofman A and Moskowitz H (2010) Isomorphic permuted experimental designs and their application in conjoint analysis. Journal of sensory studies. 25: 127-145.

- Likas A, Vlassis N and Verbeek JJ (2003) The global k-means clustering algorithm. Pattern Recognition. 36: 451-461.

- Open AI. 2022. https://beta.openai.com/docs/api-reference/introduction.