Abstract

Objective: To show the capabilities of Larval Source Management (LSM) as a tool that can significantly contribute to malaria elimination agenda.

Methods: Reviewed both published and unpublished literature for LSM of varying periods from (1929-2019), learning lessons from the mines in Zambia, Sri Lanka, Kenya, India, Greece, Philippines, Rwanda and Tanzania.

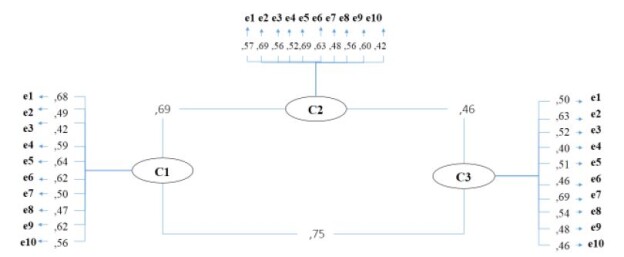

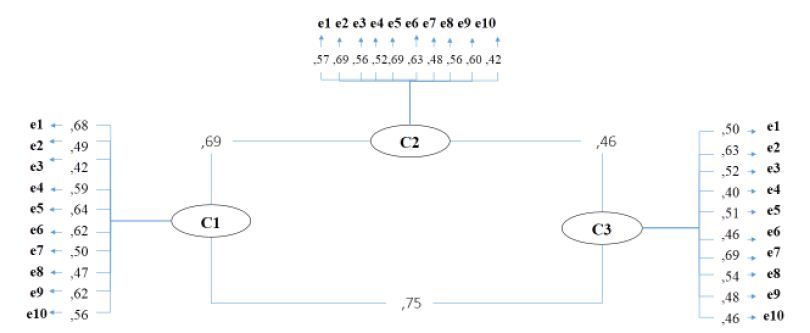

Cluster-Randomized Control Trials undertaken in Sri-Lanka, larviciding of abandoned mines, streams, irrigation ditches and rice paddies reduced malaria incidence by three-quarters compared to control (RR 0.26, 95% CI 0.22 to 0.31,20,124 participants, two trials, moderate quality assurance evidence). In three controlled, before- and trials in urban and rural India and rural Kenya, results were inconsistent (98,233 participants, three trials, very low-quality of evidence). I none trial in urban India, the removal of domestic water containers, weekly larviciding of canals and stagnant pools reduced malaria incidence that was higher at baseline intervention areas than in controls.

One cluster-RCT from Sri Lanka, larviciding reduced parasite prevalence by almost 90% (RR 0.11, 95% CI 0.05 to 0.22, 2,963 participants, one trial, and moderate quality evidence). In five controlled, before-and after trails in Greece, India, Philippines and Tanzania, an average reduction in parasite prevalence of two-thirds (RR 0.32, 95% CI 0.19 to 0.55,8041 participants, five trials, moderate quality evidence) resulted. The interventions in these five trials included dam construction to reduce larval habitats, flushing of streams, removal of domestic water containers, and larviciding. In randomized cross-over trial in the flood plains of Gambia River, larviciding by ground teams insignificantly reduced parasite prevalence (2,039) participants, one trial). So, there is strong evidence that LSM is associated with 69% of reduction in incidence (95% CI, 58-77% (in six studies) and a 75% reduction in prevalence of parasitemia (95% CI 49-88%, six studies).

In the first half of the 20th century, Zambia in the copper mines used LSM that resulted in a 97% reduction of malaria incidence from 514/1000 in 1929/1930 to 16/1000 in 1949/50; mortality fell by 88% from 32/1000/ year to 4/1000/year.

Conclusion: LSM is another policy option for Zambia to consider, alongside the primary interventions to reduce malaria morbidity and mortality in targeted breeding sites that are few, fixed, discrete and easily identifiable.

Keywords

Targeted management, Mosquito Breeding sites, Promoting larval source management, Zambia

Background

The global malaria control strategy of the 21st century aims at protecting individuals and the general public using Long Lasting Treated bed nets (LLINs), Indoor Residual Spraying (IRS) with prompt and effective measures of clinical malaria [1,2]. Notably, malaria still remains a major public health concern in Zambia and its elimination agenda strives for universal coverage of utilizing these global vector control tools. These two vector control interventions, complement each other for universal coverage for the population, as having either full coverage of LLINs or IRS within a household (NMESP, 2017-2021).

This momentum has to be maintained for further malaria reductions, supported by supplementary vector control tools needed to be added to the present arsenal [3-8]. The suppression of the transmission could be achieved by targeting the aquatic stages by reducing vector larval habitats. Larval Source Management (LSM) must be particularly important in those areas targeted for malaria elimination where malaria foci or “hot spots” persist [9-15]. LSM has been one of the oldest tools in the fight against malaria and has been largely forgotten and more often dismissed as malaria control intervention by non-vector control professionals [16].

Importantly, Zambia has to leverage the unrealized potential of LSM, that could help as the main focus for mosquito control program through lessons learnt for decades, in the developed countries like; America and other African countries [17,18]. LSM potentially aids in combating both mosquito physiology and behavioral resistance. Because LSM is primarily a complementary intervention, its impact needs to be evaluated in terms of the additive effect and cost-effective on top of primary interventions. The concept of “species sanitation” must be applied for malaria elimination. This means that attention must be directed primarily to local anopheline mosquitoes being the principal transmitters of malaria (WHO, 1982).

However, very little or no attention on financing has been given to LSM by government in Zambia. The objective of this paper was to appraise relevant literature on the global perspective, the success stories and feasible capabilities of LSM being an important tool that would contribute to the attainment of the current malaria elimination agenda for Zambia.

Justification on What Mosquito Larval Source Management is All about

Vector control has been proven to successfully reduce or interrupt malaria transmission when coverage is sufficiently high. Indoor Residual Spraying and Long-Lasting Insecticide Treated Bed nets target host-seeking adult mosquitoes while larval source management attempts to reduce malaria transmission by decreasing the number of mosquitoes that reach adult hood. However, there has been some noted chemical resistance to the two primary interventions. The mosquito larval source management is the management of water bodies (aquatic habitats) that are known to be potentially breeding sites for mosquitoes in order to prevent the completion of immature development.

Challenges of Existing Primary Malaria Interventions (LLINs and IRS) (Derue et al. 2019)

1) Wide Spread Chemical Resistance Observed in Vector Control

The insecticides used in vector control need monitoring and understanding of their trend. Malaria vector control currently in most parts of Africa relies on the use of insecticides through IRS and Plinth has proven to be effective in the last Plinth emergence and spread of insecticide resistance is threatening the susceptibility of this approach posing further enormous logistics challenges.

Monitoring and understanding the dynamics in relation to some environmental elements such as climate, physicochemical properties are key to addressing the challenges. Mosquito resistance to chemical insecticides has been identified as a global threat. According to the World Health Organization urgent action is required to prevent the further development of resistance and to maintain the effectiveness of existing vector control interventions.

2) Behavioral Modification of Target Species

Indoor mosquito species adapt to the use of LLINs and IRS through spatial avoidance and by altering the timing of their aggressiveness (changing feeding periods to earlier or later in the day).

3) Limited Outdoor Application

The dynamics of mosquito control within a confined indoor space are fundamentally different than mosquito control outdoors. Insecticide-infused nets and surface sprays have little value for controlling adult vectors that prefer outdoor spaces where disease vectors pose a significant threat to human health (beyond just malaria).

4) Negative Impact on Non-target Organisms

Depending on the product and the application, chemical interventions might have (or might be perceived as having) a negative impact on non-target organisms such as birds, bees, fish, and people.

5) Progress on Malaria Reduction has Slowed

According to the World Malaria Report 2018, only modest progress was made on global malaria reduction from 2015-2017.

LSM has been classified into:1) habitat modification, 2) habitat manipulation 3) biological control and 4) larviciding [19-22]. Habitat modification is a permanent change of land and water including landscaping drainage of surface water, land reclamation and filling but also coverage of large water storage containers, wetlands and other potential breeding sites. In addition, habitat manipulation is a recurrent activity, such as water-level manipulation, which includes measures like flushing, drain clearance, shading or exposing habitats to the sun depending on the ecology of the local vector.

Further, the biological control is the introduction of natural enemies (predators) into aquatic habitats; these are predatory fish or invertebrates, parasites or disease organisms. The use of larvicides has been the regular application of biological or chemical insecticides to water bodies for the control of mosquitoes. However, it has to be noted that the insecticides used for LSM have different modes of action including the: (1) surface films like mineral oils and alcohol or silicon based surface products that suffocate larvae and pupae, (2) synthetic organic chemicals such as organophosphate (e.g.) that interfere with the nervous system of immature stages, (3) microbial such Bacillus Thuringiesis Israelis is (BTI), and Bacillus Spharerians (BS) that kill larvae with toxins that are ingested and lead to lysis of the insect`s gut and (4) insect growth regulators such as pyriproxyfen, methoprene and diflubenzuron that interferes with metamorphoses of the insect and prevent adult emergence from the pupae stage.

Historically, by Garis Green (Copper acetoarsenite), an arsenical compound, was extensively used for anopheline larval control and the application of BTI, akatoreite, draining, and the introduction of fishes (Flinger and Lindslay, 2011) proved to be a success. http://www.malariajurnal.com/content).

Related Benefits of Larviciding as Part of an Integrated Vector Management (IVM) Approach

1) Larvicides Extend the Useful Life of Chemical Adulticides

By reducing the size of the population being selected for resistance. Biological mosquito larvicides promote the effects of chemical adulticide interventions when such applications are warranted.

2) Larvae Cannot Change Their Behavior

Unlike adult mosquitoes; larvae cannot change their behavior to avoid interventions. Once habitats have been identified and targeted interventions are highly successful because larvae are concentrated, immobile, and accessible.

3) Larviciding Works For Indoor and Outdoor Species

Larviciding is an effective intervention against both outdoor and indoor vector species. Advancements in wide area larvicide application strategies have demonstrated that larvicides can be delivered to cryptic habitats in both urban and rural settings, providing excellent reduction data for adult mosquitoes.

4) Bacterial Larvicides are Highly Specific in Their Activity

The activity of the larvicides Bacillus Thuringiensis spp. israelensis (BTI) and Bacillus Sphericus (BS) are based on highly specific protein toxins that only break down in the gut of mosquitoes and other select dipterans larvae. Excellent safety data exists for these products and their low impact on non-targets, such as birds, bees, fish, and people, all unaffected by these beneficial bacteria.

5) Data clearly Shows the Positive Effects

There is increasing adoption and a growing amount of empirical data on the impact and value of bacterial larviciding as part of an IVM program in developing countries.

Materials and Methods

We reviewed both published and unpublished literature for LSM of varying periods from (1929-2019). Zambia and other countries such as Rwanda and Tanzania LSM were reviewed bearing in mind that it is an additional intervention to the current National Malaria Elimination strategies. The reviews also addressed perceived challenges to larviciding, and heralded the research and development work that has expanded the capacity of larviciding and research cites mounting evidence that clearly demonstrates the value of larviciding in a broader integrated vector management strategy. Tanzania and Rwanda point to their empirical data demonstrating the value of a change towards a new set of interventions that includes an intensified focus on larval source management rather than only focusing on adult mosquitoes.

Discussion

This paper challenges the notion that larval source management cannot successfully be used for malaria elimination in Zambian transmission settings by highlighting historical and recent successes. It discusses LSM potential in an IVM approach working towards malaria elimination and critically reviews the common arguments that have been used against the adoption of larval source management. In addition, the paper does not aim to control advantages and disadvantages for LSM with the first line critical interventions (IRS and LLINs) which could be found everywhere [23,24] but rather aims to highlight its potential benefits as a neglected vector control tool.

The literature review addresses high demand LSM prospect, its role, efficiency and the maximum impact it can offer as well as the national neglect and underutilization in Zambia for malaria elimination, despite past success stories the interventions have contributed in some countries to control and eliminate malaria. By targeting the larval stages, mosquitoes larvae are killed “whole sale” before they disperse to human habitations. Mosquito’s larvae, unlike adults cannot change their habitat to avoid control activities [7].

Eliminating aquatic habitats close to human habitations by modification and manipulation of the environment, where possible could provide long-term and cost-effective solutions [8]. The drainage of aquatic habitats can be incorporated in the “Keep Zambia Clean, Green and Healthy Campaign Concept”. The cost for this exercise can be paid outside the health sector budget. In places where habitats cannot be eliminated, larvicides can be applied. The available formulations are very effective formulations that have been developed for anopheline control [10].

These larvicides are environmentally acceptable with minimal or no effect at all on the non-target invertebrate populations, aquatic insects such as fish, birds and mammals including human beings. LSM has been found to require no substantial change in human behavior or the management of key resources such as water, land and skills for larviciding that are similar to those requirements for IRS [11]. When LSM is appropriately and effectively used can contribute to reducing the numbers of both out-door and indoor house biting mosquitoes for malaria elimination.

LSM is a useful tool to reduce mosquito population more especially in “hot spots” and can reduce on overdependence on chemicals that at times face mosquito’s resistance. The intervention needs to be tailored to local environmental conditions. LSM can be a fordable on a small scale with pilot chemicals and then building capacity and appearance. LSM requires more than the current findings and political support needed for strategic planning and long-term funding.

The local authority and small communities with few resources but with high intervention to eliminate malaria such as in places where ITNS and IRS has not been deployed can implement LSM through heavy community strengthened engagement efforts. The interested parties outside the health sector can contribute support to LSM through major projects such as roads and buildings construction including infrastructure development in large areas and private schemes and as the mines and agriculture operations can implement LSM independent of but in collaboration with NMEP activities using corporate or local resources [6].

According to Griffin and colleagues (90) recently persecuted strong evidence that out-door biting defines the limit of what is achievable with IRS and LLINS. The only available solution to this is LSM being one of the few strategies effective against outdoor biting vectors. Locally appropriate implementation systems need to be developed on an individual basis taking local structures and administration systems into account and adapted to local epidemics ……. conditions (73). For sustainability’s sake, LSM program need time for implementation staff and institutions to develop, pilot refine and stabilize locally-appropriate, effective and sustainable procedures and institution structure (77). LSM is applied at in scale depending upon the local ecology, institutional structures including financial support.

Evidence of Efficacy of Vector Control Interventions

LSM advantage is that it abates the general mosquito’s population rather than anopheline control alone. The local population must generate more support for the program and at the same time produce infrastructure and reinforcement for the control of the adult mosquitoes especially the other viruses that have the potential for public health problems. It has to be known that interventions against malaria are typically evaluated by measuring a decline in malaria morbidity and mortality.

However, a decision making frame work must be considered before embarking on the project. The Insecticide Resistance Management and Monitoring Committee (IRMMP), the Technical Advisory Committee (TAC) must assist in decision making. The Framework to would be implementers must look at the Roll Back Malaria Structure: What is LSM? Evidence of efficacy, Economics of LSM, Minimum requirements before and embarking on LSM, where to do LSM and when not to, when to start LSM and when to stop, what`s needed for implementation? What`s needed for monitoring? Role of LSM in IVM (RBM-LSM Work stream, 2012).

Urban and Peri-urban Larval Source Management Implementation

In towns and cities, larval habitats have been found largely man-made and become relatively easy to identify and treat, as seen in the Zambian cities. Cities like Lusaka, IRS is deemed not feasible in the urban malaria vector control. LSM is very similar to that of IRS where the main evidence of efficacy is also on historical accounts and where there are few high -quality trials to measure their impact (97).

Several authors have convincingly shown that the limitations of LLINs/ITNs and IRS are largely defined by mosquitoes avoiding them by feeding or resting outdoors and/or at earlier hours and developing insecticide resistance (83,85). The concerns could be reduced if LSM is combined with indoor vector control tools. However, recent research suggests that LSM does not reduce the number of adult vectors.

It has been argued by many that LSM was not feasible in African setting due to the high number of temporary and small larval habitats for Agamidae that are difficult to find and treat promptly that the delivery of larvicide to very small habitats for example cattle hoof prints has been difficult and environmental management targets primarily larger, permanent water bodies, that are not typically anopheline habitats and therefore contribute little to malaria elimination [17]. However, recent studies show that these assertions have been found to be incorrect in many areas of the sub-Saharan Africa with stable malaria transmission. Importantly, the widely feared small and temporal habitats contribute little to the overall production of larvae and adults throughout the years (112).

Utilization of state-of-the-art tools for mapping like geographical positioning systems, geographical Information Systems with a remotely sensed imaginary, combined with modern communication tools increases the operational efficiency of disease control interventions. These interventions are successfully used for mosquito vector surveillance for example in Rwanda (126).

LSM Contributing Factors for Its Success for Malaria Elimination

There is a need for community engagement, acceptance, responsiveness, involvement, empowerment and support for LSM. The LSM interventions must strive towards community engagement of the locals in the targeted areas so that larval habitats can be increased and either treated with a larvicide or modified. The community needs have to be taken into consideration when the interventions are well planned, for example the local population livelihood might depend on some of the aquatic habitats such as sugar cane, rice and irrigation channels, pits and wells.

Therefore, capacity building programs need to be implemented to the technocrats and the community to be involved in connecting LSM as in other countries like Rwanda and Tanzania [6]. For LSM activities, information is needed for effective leadership, good arrangement and clarity of objectives. The health workforce at all levels of the implementation system and must relieve the LSM as an important industry with a tough support of the community.

Management capacity development is key to a successful LSM program. Importantly, the ability to quickly guarantee, collate, report the meaningful monotone of dates in reality, inadequate framing and management of staff and the LSM activity could lead to the limitation of LSM program, strengthening the promotion of multi-sectoral collaboration. There are key partners for LSM in Zambia such as: the Government of Republic Zambia (GRZ) sectors: Ministry of Local Government, Ministry of Agriculture, Ministry of Mining and Minerals Development, the community, local community, local business community, local parastatals, the mediators and NGOs including the Faith -Based Organizations in community mobilization.

When collaboration is well coordinated with other sectors, good practice is observed in for good infrastructure development and housing (Road construction, block making or house construction) do not create or build up new habitats for the larva [6]. Building enhanced surveillance system: strengthened surveillance system is quite important through continuous entomological monitoring. This approach has been crucial to ensure that habitat or the larva is being well handled. The epidemiological enhanced surveillance has been found to be quite vital to monitor the LSM program impact. In addition, technological innovations have also been found to make larviciding strategy viable in many parts of the world [8].

Management, Cost-effectiveness and Rate of Application of Larvicides for Malaria Elimination

Again, recent analysis from three LSM programs of various sizes and ecological settings in Africa showed the cost per person protected each year ranged from u$ LLINs U$0.94 to U$2.50 [25-50]. This compares favorably with IRS (Range from various African settings U$0.88-4.94 [47] or LLINs range costing U$5 and assumed to last three years U$1.48-2.60 [51], suggesting that LSM presents a viable and cost-effective malaria control tool that can complement existing malaria control methods. With the current agenda for the movements towards malaria elimination, there has been a need to scale-up use of additional LSM cost-effective tools to reach the elimination goal.

In order to be effective, larviciding must be specifically adapted to each locality and be carried out thoroughly and selectively. The current strategy of LSM with larvicides has been to treat all available larval habitats [24]. Many people argue for more spatially targeted approach [36] to apply larvicides only at the most productive habitats [19]. In fact, to date no published evidence exists that shows that accurately, determining where malaria vectors will develop is possible [20].

However, several models have been developed recently to predict mosquito larval habitats, location and productive potential. Still, in future it might well be possible to target interventions more effectively [22]. Any benefit of targeting larval habitats at specific times of the year needs to be proven but may work well when LSM has been part of the IVM package of intervention [14].

The other concern of LSM is the application frequency. For frequency, it must be considered for the elimination agenda with or without other interventions in the communities, where the breeding sites are few, fixable and findable [41]. The application of larvicides to potential breeding sites could be cost-effective more especially in urban communities. The LSM strategy is to treat all available larval habitats [42]. In some cases, whilst some types of habitats have been more likely than others to have aquatic stages 25, this has not been sufficiently refined for spray teams to be able to identify and target only these high-risk habitats.

However, the application frequency of larvicides is another concern; where microbial larvicides are generally applied weekly to all potential sites [4]. Whilst the larvicides with greater residual activity would benefit for treating permanent habitat [49]. It is important also to note that they are not necessarily the panacea. They might appear to be, since during periods of rain new potential mosquito larval habitats can appear and larvae can develop into adults before the next round of application becomes simpler, because the people who apply the larvicide become familiar with their treatment community area and weekly cycle of activity.

Consequently, the overall targeting interventions in space and time as well as the utilization of more residual larvicides will only reduce costs if proven to be equally effective, than blanket application and if the increased management effort for decision making does not outweigh the larvicides costs [13]. Further, the substantial reductions in long term costs might be made, if larviciding is combined with environmental management. In some country studies, like the study in Tanzania-Dar-es-Salaam, indicated that simply by improving the drainage in drains would reduce larval breeding by 40% [9].

Larval Source Management Feasible Capacity for Malaria Elimination

Generally speaking, Africa has renewed interest in LSM and is often called the heartland of malaria, with LSM application as a complementary intervention to Indoor Residual Spraying and Long-lasting Insecticide Treated nets [18]. As can be expected, LSM could perform better especially where outdoor biting by malaria vectors has been problematic or where there has been resistance to the insecticides used for IRS or LLINs [18]. In certain eco-epidemiological settings, where larval habitats have been fixable, few and findable for example in Asia and Africa have shown that larviciding can reduce adult vectors density and consequently morbidity and mortality due to malaria [6].

Major Findings

There are several lessons learnt, success factors and best practices on the effects of larval source management:

Effects of Bacterial Larvicides

It has been found that at low rates, bacterial larvicides cause: a reduction in larval density, vector density, vector biting, reduction in disease transmission in most tested areas [8]. Further, according to Cochrane data base of systemic reviews [5], they also concluded 13 studies; four cluster-RCTs, eight controlled before-and-after trials, and one randomized cross-over trial. The included studies evaluated habitat modification (one study), habitat modification with larviciding (two studies), habitat manipulation (one study), habitat manipulation plus larviciding (two studies), and larviciding alone (seven studies) all together) in a wide variety of habitats and countries.

Evidence of Effects of LSM on Malaria Incidence

Another cluster-RCTs undertaken in Sri-Lanka, larviciding of abandoned mines, streams, irrigation ditches and rice paddies reduced malaria incidence by around three-quarters compared to control (RR 0.26,95% CI 0.22 to 0.31,20,124 participants, two trials, moderate quality assurance evidence). In three controlled, before- and trials in urban and rural India and rural Kenya, results were inconsistent (98,233 participants, three trials, very low-quality of evidence). In one trial in urban India, the removal of domestic water containers together with weekly larviciding of canals and stagnant pools reduced malaria incidence that was higher at baseline intervention areas than in controls.

Further, dam construction in India and larviciding of streams and swamps in Kenya reduced malaria incidence to levels similar to the control areas. In addition, randomized cross-over trials in the flood plains of the Gambia river, where larval habitats were extensive and ill-river, where by ground teams did not result in a statistically significant reduction in malaria incidence (2039 participants, one trial).

Evidence of Effects on Parasite Prevalence

A further study, in one cluster-RCT from Sri Lanka, larviciding reduced parasite prevalence by almost 90% (RR 0.11, 95% CI 0.05 to 0.22, 2,963 participants, one trial, and moderate quality evidence). In five controlled before-and after trails in Greece, India, the Philippines and Tanzania, LSM resulted in an average reduction in parasite prevalence of around two-thirds (RR 0.32, 95% CI 0.19 to 0.55,8041 participants, five trials, moderate quality evidence). The interventions in these five trials included dam construction to reduce larval habitats, flushing of streams, removal of domestic water containers, and larviciding. In randomized cross-over trial in the flood plains of the Gambia River, larviciding by ground teams did not significantly reduce parasite prevalence (2,039) participants, one trial). So, there is strong evidence that LSM is associated with 69% of reduction in incidence (95% CI, 58-77% (in six studies) and a 75% reduction in prevalence of parasitemia (95% CI 49-88%, six studies).

In the first half of the 20th century, Zambia by then had a major threat of malaria to the economic success of the copper mines. Andes can arose to implement integrated malaria vector control program primarily based on attacking the larval stages of malaria vectors by use of environmental management 39], that resulted in a 97% reduction of annual malaria incidence from 514/1000 in 1929/1930 to 16/1000 in 1949/50 similarly, overall mortality fell by 88% from 32/1000/ year to 4/1000/year.

Recent evidence under research showed that; (I) hand – applied larviciding reduced transmission by 70-90% where the majority of aquatic mosquito larval habitats were defined and aquatic surface areas not too extensive [50], that the addition of larviciding with LLINs resulted in greater gains than could be achieved by using LLINs alone. Hard drive application of larvicides was not effective in areas with very extensive water bodies such as the floods -plains of larger river systems [33].

In the meantime, the mines on the Copper belt and Zambia Sugar field efficacy trials have been conducted for various strains of larvicides to ascertain LSM effectiveness as well as its feasibility capabilities to reduce malaria vector population density. The trial results revealed that larvicides performed extremely well and provided effective anopheles control for 30 days [31]. A further 2nd field trial study conducted by the NMEP in Nigeria on mosquitocidal strains of Bacillus Thuringiesis Var Israelensis (BTI) and Bacillus Sphaerians (BS) in 1 Kene Local Government Authority of Ogun State, revealed that the biological larvicides were highly effective against all strains of anopheline culicines and aedes mosquitoes [40].

Again, another 3rd trial was conducted in Nigeria on another formulation of BTI serotype H-14 (Bactive) and Bacillus Sphaerians strain 2362 (Griseleaf). In conclusion, the effectiveness of the residual efficacy of bactivec and Griseleaf biolarvicides were proven for the control of anopheles and other species present such as the culex quinequefasciatus. The selected 1, 2 and 4 sites a stable and significant reduction was observed from the first 24hrs to the 30th day in at least 3 of the 4 treated sites within ranges of 80.3% to 100%.

Currently, there are 734 named mosquitos’ abatement districts in countries/continents like the US, all deploying LSM, which is the primary and preferred method of mosquito control in the States. In states like California and Florida, LSM has been found to provide dual benefits of not only reducing numbers of house entering mosquitoes but, importantly, also those that bite outdoors. The large scale of LSM was a highly effective tool for malaria control in the first half of the twentieth century, but was largely disbanded in favor of IRS with DDT [40].

Further, it has been noted that currently many countries in Africa lack the capacity of local entomologists [12]. The few scientists available are very well qualified but their professional decisions are usually at the peril of the financiers` negative influence on the scientific decisions made by these scientists on the LSM programs. Yet the lack of capacity can be increased as available human resource need to be improved to ensure that any improved control could be sustained [37].

There is need for skills adaptation for empowering communities. It has been observed that LSM has several aspects that are significantly more sustainable than IRS and LLINs, since highly effective tools other than larvicides can be applied by local communities with dependency of high recurrent costs. Importantly, there is need for local adaptation and skills must be seen as an important opportunity for creating self-empowerment for malaria elimination.

Clearly, larval source management must build upon local initiatives with collaboration of existing stake holders and advocates. All mosquito species must be targeted to reduce nuisance biting “pest mosquitoes” and maintain community support. Community expectations must be met based on their perceptions of the impact to which the relationship between malaria, mosquito species and habitats are usually poorly understood, by local communities that are often more motivated by mosquito biting nuisance than malaria or any other pathogens they transmit [44].

However, there is a key challenge for mosquito control programs, focusing on larvicides in urban areas is to have full regular access to all open spaces potential for accommodating aquatic habitats where mosquito proliferation takes place. This includes all fenced plots and other areas within restricted access for the public. This has been found to require substantive and open collaboration between residents and stakeholders. Community involvement in both the recruitment process of the individuals and implementation of the intervention has been found to be essential to program performance [14].

In order to achieve wide -scale community-based implementation through a decentralized vertical management structure is by utilization of the hierarchical gradient of implementation strategies and partner roles across all the necessary spatial scales. Such centralized coordination is essential to enable institutionalization of strengthened management and planning, improved community mobilization capability and the capacity to exploit national, private and business community funding systems [43].

Data Utilization for Larval Source Management

Equally important has been the management of a successful larviciding program that requires a scientific approach with knowledge and data capture and analysis on: mosquito physiology [mosquito feeding strategy, age of larvae, and density of larvae] Temperature [Humidity, water depth and water turbidity], water organic content [Presence of vegetation, location of habitats, access to habitats]. Data shows that these skills and competencies can be managed effectively by a team, and that knowledge base created by this process offers additional benefits with positive impacts, on other areas of the program including such fundamental objectives as reduced vector densities, reduction in vector biting and reduction in disease transmission [43].

All things considered, effective mechanisms for communication and feedback to the community of monitoring data within days, weeks or months, rather than years are essential for LSM of mosquitoes that can develop from egg to an adult within a day and weeks. This calls for continuous and thorough monitoring because success and failure occur on the remarkable fine spatial (<1 KM2) and temporal scales (<1 Week) that match to the retreatment cycles and geographical division of responsibility to individual staff [43].

There is need for intensified surveillance for larvae mosquito populations in order to assess the effectiveness of the larvicide application, and the performance of individual personnel. This approach is essential for internal monitoring functions and external quality assurance of the activities, as well as monitoring and evaluation of impact on adult mosquitoes. However, malaria risk should be separately conducted by institutionally independent partners by reporting directly to program management to avoid conflicts of interest that inevitably arise from self-assessment [38].

In other words, proven systems for rigorous and timely monitoring of LSM remain to be fully developed, and take many years to slowly evolve to address the high standards required to ensure rapid identification of implementation failures at sufficiently fine spatial and temporal scales. LSM programs must therefore start small, through a manageable pilot scales and then progressively build and institutionalize implementers capacity and experience. Training and development cost must therefore be included in the budgets. These must be strategically planned and consistently supported over the long term so that locally-adapted LSM program and their supporting institutions have sufficient time to learn, consolidate and stabilize [44].

Ultimately, the effectiveness of LSM program relies upon monitoring and managing at very fine spatial and temporal scales. There must be the ability to collate, synthesize and report simple but reliable monitoring of data in the shortest time possible is essential. Furthermore, maintenance and management of a stable funding base, as well as an effective collaboration between the partner institutions responsible for the diverse and distinct functions of an LSM program that is paramount to the long-term success. Capacity to manage logistics, human resources, institutional partnerships and funding support are most limiting, far more so at this juncture than the technical entomology skills [38].

Conclusion

The pace of urbanization poses a number of public health problems including increases in malaria morbidity and mortality. Urban malaria control has to heavily rely upon larviciding and strengthened community implemented environmental management such as drainage and habitat filling. This provides vital LSM effectiveness, affordability and sustainable vector control for malaria elimination. In addition, participatory planning is equally essential to enhance local capacities and ensures community ownership. To achieve the required results, there is need for central coordination role of urban LSM by the local authorities, enabled institutionalization of strengthened management and planning, improved community mobilization capability and capacity to exploit planning for improved communities. In Zambia, LSM is another policy option to consider, alongside LLINs and IRS in order to reduce malaria morbidity and mortality in both urban and rural areas, where sufficient proportions of larval habitats can be targeted and where malaria breeding sites are fixed, discrete and easily identifiable. Therefore, in some settings LSM may complement other methods of vector control in malaria elimination programs. In such communities, there is need for high degree of LSM program ownership by the city councils, coupled with catalytic generated funding and technical support from the expertise from MOH for the establishment of a sustainable LSM program.

Acknowledgement

Part of the contents of this publication is based on the several results of the meetings of the Technical Working Groups (TWGs), Technical Advisory Committees (TACs) and Open Forum discussion on LSM over several years. I would like to thank all those who gave me time to discuss with over LSM prospects and arrived at crafting this article to spearhead the implementation of LSM as a critical supplementary Vector Control Intervention to LLINs & IRS.

References

- Becker N, et al (2003) Mosquitoes and their Control. New York.

- Blair J, et al (2008) Integrated Vector Management for malaria control.

- Carlson B (2006) Source reduction in Florida`s salt marshes: Management to reduce pesticide use and enhance the resource. J Am Mosq Control Assoc 22: 534-537. [crossref]

- Castro MC, Tsurutu A, Kanamoris S, Kamadu K, Mkude S Community-Based Environmental Management for malaria control: Evidence from a small -scale intervention in Dar-es- Salaam, Tanzania.

- Cochrane Data Base of Systematic Reviews (2013). cochranelibrary.com

- Cochrane Reviews (2012) WHO Documents, Country documents, private sector documents, LSM pilots and case studies.

- Cohen JM, Mooned B, Snow RW, Smith DL (2010) How absolute is Zero? An evaluation of historical and current definitions of malaria elimination.

- Derue, et al. (2019) Challenges of existing primary malaria interventions (LLINs and IRS).

- Dongus S, P Feither C, MettaE, Mbuyita S, Obrist B (2010) Building multi–layered resilience in a malaria control program in Dar -es-Salam, Tanzania.

- Elsen L, Eisen RJ (2011) Using Geographical Information Systems (GIS) and decision support systems for the prediction, prevention and control of vector borne diseases. Annu Rev Entomol 56: 41-61. [crossref]

- Ernst KC, Adoka SO, Kowuor DO, Wilson ML, John CC (2006) Malaria hotspot areas in a high land Kenya Sites are consistent in epidemic and non-epidemic years and are associated with ecological factors. Malar J 5: 78. [crossref]

- Ferguson HM, Dorn haust A, Beeche A, Borgemeister C, Gottlieb M, et al. (2007) Ecology: a prerequisite for malaria elimination and eradication. Plos Med 7: e1000303. [crossref]

- Flinger U, Lindslay SW (2011) Larval Source Management for malaria control in Africa: myths and reality. Malar J 10: 353. [crossref]

- Flinger U, Ndenga B, Githeko A, Lindslay SW (2009) Integrated Malaria Vector Control with microbial larvicides and Insecticide Treatednets in Western Kenya: a controlled trial. Bull World Health Organ 87: 655-665. [crossref]

- Flinger U, Sombroek H, Megampere S, Van Loon E, Takken W, et al. (2009) Identifying the most productive breeding sites for malaria mosquitoes. Malar J 8: 62. [crossref]

- Floore TG (2006) Mosquito Larval Control Practices: Past and Present. J Am Mosq Control Assoc 22: 527-533. [crossref]

- Gadawski R (1989) Annual Report on mosquito surveillance and control in Godowsky control Branch, Parks & Recreation Dept.

- Griffin JT, et al. (2010) Reducing Plasmodium Falciparum malaria transmission in Africa: a model -based evaluation of intervention strategies.

- Gu W, Novak R (2005) Habitat -Based Modelling of impacts of mosquito larval interventions on entomological inoculation rates, incidence and prevalence of malaria.

- Killen GF, Tanner M, Mukabana WR, Kalongolela MS, Kannady K, et al. (2006) Habitat targeting for controlling aquatic stages of malaria vectors in Africa. Am J Trop Med Hyg 74: 517-518. [crossref]

- Lee County Mosquito Control district website. http://www.Icmd.org/I

- LI L, Bian L, Yakob L, Zhou G, Yan G (2011) Analysing the generality of spatially predictive mosquito habitats models. Acta Trop 119: 30-37. [crossref]

- National Malaria Elimination Strategic Plan (2017-2021)

- Majambere S, Pinder M, Fillinger U, Ameh D, Conway DJ, et al. (2010) Is the mosquito larval source management appropriate for reducing malaria in areas of extensive flood in the Gambia? A cross-over intervention trial. Am J Trop Med Hyg 82: 176-184. [crossref]

- Malaria Vector Control in Africa (2001) Strategies and Challenges; Report from a symposium held at the American Association for the advancement of science annual meeting.

- Minakawa N, Sonye G, Yan G (2005) Relations between the occurrence of Anopheles Gambiae S.L (Diptera, Culicidae) and size and stability of larval habitats. J Med Entomol 42: 295-300. [crossref]

- NajeraJ A, Zaim M (2002) Malaria Vector Control-Decision making criteria and procedures for judicious use of insecticides. WHO Pesticide Evaluation Scheme (WHOPES).

- National Malaria Control Strategic Plan (2012-17)

- Pluess B, Tauser FC, Lengeler Sharp B (2010) Indoor Residual Spraying for Preventing Malaria (Review). Cochrane Review 2010: CD006657. [crossref]

- RBM: Global Malaria Action Plan. Roll Back Malaria Partnership (2008)

- Rezendaal JA (1997) Vector Control: Methods for use by individuals and communities. WHO.

- Riehle M, Guelbeogo WM, Gneme A, Eiglmeier K, Holm I, et al. (2011) A cryptic subgroup of Anopheles Gambiae is highly susceptible to human malaria parasites. Science 331: 596-598. [crossref]

- Roll Back Malaria -Larval Source Management (2012).

- Russell TL, Govella NJ, AZIZIS, Drakeley C, Kachurs P, Killen GF (2011) Increased proportion of outdoor feeding a mong residual malaria vector populations following increased use of ITNs in rural Tanzania.

- Smith D, Dushoff J, Snow RW, Hay SI, et al. (2005) The Entomological Inoculation Rate (EIR) and Plasmodium Falciparum infection in African children. Nature 438: 492-495. [crossref]

- Smith McKenzie FE, Snow RW, Hays (2007) Revisiting the basic reproductive number for malaria and its implications for malaria control. Plos Biol 5: e42. [crossref]

- Townson H, Nathan MB, ZAIM M, Gullet P, Manga L, et al (2005) Exploiting the potential of vector control for disease prevention. Bull World Health Organ 83: 942-947. [crossref]

- TustingL S, Thwing J, Sinclair D, Fillinger U, Gimnig J, et al. (2013) Mosquito Larval Source Management for controlling malaria (Review). Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2013: CD008923. [crossref]

- Utizinger J TozamY, Singer BH (2001) Efficacy and cost effectiveness of environmental management for malaria control. Trop Med Int Health 6: 677-687. [crossref]

- Walker K, Lynch M (2007) Contributions of Anopheles Larval Control to malaria suppression in Tropical Africa: Review of achievements and potential. Med Vet Entomol 21: 2-21. [crossref]

- WHO (2007).Malaria Elimination; Afield Manual for low and moderate endemic countries.

- WHO (2010). Hand book on integrated Vector Management (IVM) Geneva.

- WHO (2012). Related benefits of larviciding as part IVM Approach

- WHO (2013).A supplementary measure for malaria vector control. An Operational Manual.

- WHO Expert Committee on malaria Geneva: World Health Organization

- Wool House M, Dye C, Etard JF, Smith T, Charlwood JD, et al. (1997) Heterogeneities in the Transmission of Infectious agents: Implications for the design of control programs. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 94: 338-342. [crossref]

- E, Conor, Thomson M (2008) Improving the cost-effectiveness of IRS with climate informed health surveillance systems. Malar J 7: 263. [crossref]

- World Health Organization (1982) WHO Expert Committee on malaria, Geneva

- World Malaria Report (2018).

- Worrall E, Fillinger U (2011) Large scale use of mosquito larval source management for malaria control in Africa: A cost analysis. Malar J 10: 338. [crossref]

- Yelich Jedis Flagler C (2007) Operations, costs and cost-effectiveness of five insecticide-treated nets programs (treated) and two Indoor Residual Mozambique. Spraying Programs (Kwa Zulu Natal).