Abstract

The objectives of this study were to explore the relationships between categories around the undertaking of migratory flows in order to specify a model for their systematic study. A documentary, exploratory and transversal study was carried out with an intentional selection of sources indexed to international repositories; Dialnet, Latindex and Redalyc, considering the publication period from 2007 to 2019, as well as the search for keywords. A relationship structure was observed between three preponderant categories in the literature: acculturation, multiculturalism and interculturalism in which significant differences were established with respect to selected extracts from the consulted literature. However, there was no appreciable collaborative and consensual learning among the judges who evaluated the marks in three qualification rounds, although the design of the research limits the findings to the informative sample. These results demonstrate the specification of a model in order to establish differences between the categories and anticipate exclusion or inclusion scenarios between migratory flows and native communities, as well as the relevance of entrepreneurship in the local development of both groups.

Keywords

Migration, Entrepreneurship, Development, Setting, Acculturation

Introduction

Roughly, migratory flows allude to a process of passage, stay and return that has been explained by three epistemic foundations: a) acculturation; B) selectivity and c) identity. It is a multidimensional process in which each phase and each dimension unveils the differences between governors and governed in terms of sustainable, human and local development policies, and mainly explains the asymmetries between migratory flows and native spheres [1].

The concept of migration is multidimensional, but the studies related to migrant cultures with respect to native cultures have focused on a generalizing concept of rupture, crossing, stay and return in the economic and occupational order. Many occupational studies, emphasizing dependence, conformity, and obedience of migrant cultures with respect to native culture, are destined for human, local and regional development only with migrant cooperation in services or agroindustrial activities [2]. The phenomenon of migration has been approached from an ethnocentric, polyculture or multicultural approach, focusing on the adjustment of migrant cultures with respect to the laws, values, and norms of native cultures [3]. In that sense, substantial justice from multiculturalism is the integration of social justice and cultural justice, or, the concatenation of economic, political and social rights with respect to cultural differences and self-determination.

From these approaches, migration has been understood as a process of acculturation, assimilation, adaptation, and selectivity of talents with respect to an internal labor market that demands the environment and the capacities required to carry out local development, through the distribution of the labor force in strategic sectors such as agro-industry or services. The selectivity of talents that moved from emerging to developed countries is only possible in the cases of the so-called economy 4.0 [4].

This is because the perspectives of migration have considered the native cultures as active and vital in the development process whereas migrant cultures are passive or collaborative in the endogenous development of native cultures, coupled with substance justice, as antecedent of interculturalism, the concepts of impartiality such as granting rights to minorities, self-government or political and legal autonomy, polyethics or equality dissemination guarantees among members of a group, as well as the specificity and cultural legitimacy embodied in dialogue, negotiation and co-responsibility subscribe to the construction of a new model for the study of migrant cultures in relation to native cultures ([3]: page 255).

In this sense, the notion of social justice was linked to the consequences of immigration as it warned about asymmetries in terms of rights and obligations, opportunities and capabilities, as well as between commitments and responsibilities between migrant cultures and native cultures [5].

Well, the study of migratory flows no longer as passive entities and dependent on native cultures gestate in the work of entrepreneurship and innovation that distinguish this new wave of its predecessors focused on compliance and obedience, now observed at migration as active and innovative entities. These are migratory flows with civic virtues oriented towards a sense of identity and belonging to a universal community, observed by their degree of empathy, commitment, altruism, solidarity, satisfaction and happiness [5].

The theoretical, conceptual, empirical and hypothetical frameworks with respect to entrepreneurial migratory flows are grouped into 1) acculturation, assimilation, and adaptation; 2) selectivity and human capital; 3) identity, spheres, networks, and multi and intercultural flows.

The acultural, assimilative or adaptive perspective distinguishes migrants and natives not only from the place of origin, its uses, and customs but also its objectives, tasks, and goals. It is logic of profit and utility as a preponderant and determining factor of the relations between migratory and native flows. In this sense, development policies with such an approach highlight the achievements and scope of programs based on sustainable rather than human or local development, since it is assumed that the labor market will generate and disseminate the bases for establishing the quality of life and subjective well-being related to health, education, and employment. These are sector programs and strategies in which support and incentives, as well as financing, are aimed at containing migratory flows according to the needs of the labor market [6].

In this way, entrepreneurial migrant flows are circumscribed to the inclusion and social protection policies that the receiving State implements in order to promote development in the economy of industrial production and services. Migrants are considered a skilled and specialized workforce, a fundamental part of the gearing of the productive and service sectors. It is assumed that the State must protect the interests of the natives by postponing the stay of migrants and encouraging their abilities; knowledge, and skills from and with the corresponding occupational health [7].

The selectivity approach considers that the development will be gestated from the policies of business promotion and market opening. Regionalism and multilateralism are essential to encourage sustained development and, immediately, human and local development. The aim is to promote policies for evaluation, accreditation, and certification of the quality of the processes and achievements of institutions and organizations sponsored by business development policies, as well as market-opening policies. In this process of selectivity, migratory flows are evaluated by their degree of intellectual capital in relation to the requirements of the labor market [8].

The undertaking of migratory flows is considered as a phase or instance subsequent to the implementation of business promotion policies, but above all, as a result of health, educational and labor policies with emphasis on the evaluation, accreditation, and certification of objectives, tasks and goals both institutional and organizational, since, it is precisely in these instances where the asymmetries between natives and migrants are resolved in favor of sustainable, human and local development. It is considered that the selection of the best talents, intellectual capitals, skills, and knowledge will build a culture of entrepreneurship, innovation, and success [9].

The paradigm of identity, unlike acculturation and selectivity, warns that the asymmetries between migrants and natives are due to the establishment of spheres, networks and flows since migrants establish relations of empathy and commitment by virtue of their abilities and the natives are organized rather in terms of a culture of domination. Among other differences, the migrant customs and practices are oriented and tolerated by the natives from their consensual diversity, which means, the migrants are considered as different in their traditions, but at the same time, indispensable for the development of the country. A receiver as the economy that expels those [10].

Therefore, the policies implemented from this approach recognize the differences between migrants and natives that will determine sustained, human and local development. That is to say, programs and strategies do not seek to dilute asymmetries, but to increase them in favor of the recognition, admiration, and respect of personal attributes, organizational innovations, state integrality and national competitive advantages [11].

This is how development policies are properly structured based on differences between migrants and natives, but the approach distances and approaches groups according to programs and strategies implemented at different levels: sustainable, human and local [12].

From the theoretical point of view, the study of migration supposes, without a doubt, the establishment of an agenda, which from a thorough review of the literature (that is, the state of the art, the state of the question or of the state of knowledge), alluding to the issue of migration. In effect, starting from an epistemological criterion, two major groups of theoretical discussion approaches are established [13].

Since it was about social work, it was thought to privilege the “intervention”; however, the concept of intervention has been questioned and even replaced by the term of intercession. Indeed, in the past with the Benefactor State, social work would have to contribute to economic and social development. Instead, now paradoxically, with neoliberalism in between, society comes to participate more; however, the work of social work is to promote dialogue, management, and evaluation. In other words: intercession, mediation between the State and organizations. Social work will intercede in the communication of the different actors of civil society. This is your future [9].

Entrepreneurship consists of empowering opportunities (including the generation of their own opportunities); as well as optimize resources and strengthen capacities [14]. Entrepreneurship is also a historical process in which levels of development are reflected according to migratory flows. Therefore, the learning of entrepreneurship is, undoubtedly, an indicator of development.

In this sense, social work has generated models for the study of entrepreneurship, understood as learning from actors involved in the journey and stay with an entrepreneurial culture so that, upon return, with the use of certain capital, learning, the knowledge and skills, favorably affect, in this case, in the commercialization of a product (organic coffee).

Studies related to knowledge networks, also known as neural networks, have established associations between different variables, such as beliefs, attitudes, intentions, and behaviors; in order to demonstrate a node learning (group) with respect to a neuron (or network system).

In the case of migratory flows [Exit (expulsion) ⇨ Crossing (travel) ⇨ Stay (residence-work) ⇨ Return (return to the place of origin)] is possible to note the degree of entrepreneurship, if they are considered as nodes in a particular network of migrants returning to their place of origin, provided with resources, skills, knowledge and expertise; all this oriented to investment in the local economy [15].

However, studies of migratory flows have focused their interest on the dominant native cultures by proposing laws, values, and norms are ethnocentric, polycultural or multicultural, although they limit the entrepreneurial capacities of migratory flows, they can adapt, assimilate the dominant lifestyles and be selected according to their skills and knowledge to achieve their insertion in society [16].

Precisely, the objective of this work was to explore the relationships between the categories of acculturation, multiculturalism and interculturalism reported in the literature from 2007 to 2019 in repositories such as; Dialnet, Latindex, and Redalyc in order to specify a model for the study of the phenomenon in endogenous development with local entrepreneurship.

Method

A documentary, exploratory and transversal study was carried out. A non-probabilistic selection of sources indexed to Dialnet, Latindex and Redalyc was made, considering the period of publication from 1999 to 2017, as well as the key words: “migration”, “entrepreneurship”, “inclusion”, “development” and “networks”.

An array of content analysis in order to set the agenda, axes and discussion topics related to migration was used. The matrix includes the coding, weighting of judges’ evaluations around the revised information (Table 1).

Table 1: Content Analysis Matrix

|

Model |

Indicator | Coding | Weighing |

Interpretation |

| Acultural | Adaptation, assimilation and return | 0 = vertical exclusion, 1 = horizontal exclusion, 2 = vertical inclusion, 3 = horizontal inclusión | 0 to 1 0 points as vertical exclusion threshold | Agenda, axes and discussion topics focused on exclusion and social injustice |

| Multicultural | Insertion, Selectivity andreincersion | 0 = vertical exclusion, 1 = horizontal exclusion, 2 = vertical inclusion, 3 = horizontal inclusión | 11 to 20 points as selective inclusion threshold : vertical | Agenda, axes and discussion topics focused on social justice based on the legal framework and native culture |

| Intercultural | Entrepreneurship andinnovation | 0 = vertical exclusion, 1 = horizontal exclusion, 2 = vertical inclusion, 3 = horizontal inclusión | 21 to 30 points as horizontal social inclusion threshold | Agenda, axes and discussion topics focused on participation, dialogue and co-responsibility between migrant and native cultures |

Source: self-made

The coding was established by judges who evaluated the findings matrix (Table 1A in the annex) based on criteria such as 0 = vertical exclusion, 1 = horizontal exclusion, 2 = vertical inclusion and 3 = horizontal inclusion.

For example: the information related to “Identity, globalization and equity” was evaluated on Thursdays as a content or extract of vertical exclusion, as the dominant culture prevails as regards migrant cultures disseminated in identities such as diaspora, ferry wheels or nomads. The latter oriented to equity by a multicultural legal framework that raises the self-determination of groups as long as these conform to the laws of the recipient country.

The weighting threshold, considering that three models prevail for the study of the migratory phenomenon: acculturation, multiculturalism and interculturalism, was structured as: 0 to 10 information oriented to the study of vertical exclusion, from 11 to 20 information directed towards the selective exclusion vertical and 21 to 30 information oriented to the study of horizontal inclusion.

Following the same example of “identity, globalization and equity”, it reached a score of 9, evidencing that it is information oriented to the study of exclusion, focused on the vertical asymmetries between the dominant cultures that may be the native with respect to the migrant cultures that can be identities such as: nomads, diaspora and ferry wheel.

The threshold of 0 to 10 points of 30 possible was interpreted as a reflection of an agenda, axes and content issues related to exclusion and social injustice for evidencing asymmetries between native cultures and migrant cultures regarding economic, political, social and sexual rights .

The threshold of 11 to 20 points out of 30 possible was interpreted as a reflection of a genre, axes and debate topics focused on the possibility of dialogue between migrant and native cultures with respect to human development, health, education and employment, which, being equitable, substantially improves the selectivity of talents and directly affects productivity as well as competitiveness.

The threshold of 21 to 30 points was interpreted as a reflection of an agenda, axes and discussion topics focused on the social inclusion of migrant cultures through dialogue with native cultures. This supposes a deliberative participation, whether informed or reasoned with respect to equity in terms of economic, political and social rights.

Based on the Delphi technique, the content of the concepts and indicators of migratory flows was analyzed with respect to development: sustainable, human and local, as well as with inclusion and social protection.

The information was compared and integrated considering, year, author, concept, technique and findings in order to be able to synthesize the information and expose it to 10 expert judges in the problem, who evaluated the content following the criterion of vertical exclusion, horizontal exclusion, vertical and horizontal inclusion to highlight the differences and similarities between migrant cultures and native cultures.

The confidentiality and anonymity of the judges was guaranteed in writing with respect to their responses, as well as the results of the study, which informed the participants that these findings would not negatively or positively affect their economic, political and social status.

Two tables or matrices were drawn up to show the differences and similarities in terms of the categories of development and social protection, indicators of exclusion and vertical as well as horizontal inclusion.

A model of trajectories and axes of dependency relations between the variables used in the revision of the literature was specified in order to be able to discuss the scope and limits of the results, as well as future research lines concerning the problem, the phenomenon and object of study.

Results

Table 2 shows the descriptive values of the instrument or matrix of content analysis, which demonstrate the normal distribution of the coded responses of the literature consulted and the expert judges who evaluated the contents.

Table 2: Instrument Descriptions

|

E |

M | S | K | A | C1 | C2 | C3 | ||||||

|

R1 |

χ2 | Df | p | χ2 | df | p | χ2 | df |

p |

||||

|

e1 |

2,67 |

0,89 | 0,75 | 0,70 | 13,25 | 14 |

<,05 |

||||||

|

e2 |

2,91 |

0,83 | 0,73 | 0,76 | 15,23 | 14 |

<,05 |

||||||

|

e3 |

2,03 | 0,94 | 0,60 | 0,77 | 14,36 | 18 | <,05 | ||||||

| e4 | 2,43 | 0,85 | 0,84 | 0,73 | 13,26 | 10 |

<,05 |

||||||

|

e5 |

2,78 | 0,80 | 0,63 | 0,78 | 14,36 | 13 | <,05 | ||||||

| e6 | 2,15 | 0,81 | 0,61 | 0,83 | 15,47 | 11 | <,05 | ||||||

|

e7 |

2,09 | 0,96 | 0,59 | 0,82 | 14,25 | 11 | <,05 | ||||||

| e8 | 2,79 | 0,85 | 0,73 | 0,84 | 14,23 | 15 |

<,05 |

||||||

|

e9 |

2,56 | 0,87 | 0,64 | 0,74 | 14,56 | 13 |

<,05 |

||||||

|

e10 |

2,75 | 0,93 | 0,83 | 0,72 | 15,42 | 12 | <,05 | ||||||

| R2 | |||||||||||||

|

e1 |

2,90 | 0,94 | 0,63 | 0,80 | 13,25 | 17 | <,05 | ||||||

| e2 | 2,86 | 0,96 | 0,74 | 0,85 | 15,49 | 15 | <,05 | ||||||

|

e3 |

2,75 | 0,98 | 0,84 | 0,89 | 13,46 | 10 | <,05 | ||||||

| e4 | 2,98 | 0,89 | 0,74 | 0,83 | 14,35 | 15 |

<,05 |

||||||

|

e5 |

2,84 | 0,85 | 0,77 | 0,67 | 14,35 | 16 | <,05 | ||||||

| e6 | 2,70 | 0,88 | 0,80 | 0,84 | 14,35 | 13 |

<,05 |

||||||

|

e7 |

2,84 | 0,99 | 0,82 | 0,88 | 13,24 | 12 | <,05 | ||||||

| e8 | 2,80 | 0,94 | 0,73 | 0,73 | 15,32 | 12 |

<,05 |

||||||

|

e9 |

2,78 | 0,93 | 0,72 | 0,72 | 13.45 | 13 | <,05 | ||||||

| e10 | 2,45 | 0,84 | 0,89 | 0,75 | 15.46 | 16 |

<,05 |

||||||

|

R3 |

|||||||||||||

| e1 | 2,63 | 0,79 | 0,82 | 0,84 | 15,47 | 13 |

<,05 |

||||||

|

e2 |

2,70 | 0,84 | 0,80 | 0,85 | 14,35 | 15 | <,05 | ||||||

| e3 | 2,64 | 0,85 | 0,73 | 0,80 | 15,47 | 18 | <,05 | ||||||

|

e4 |

2,53 | 0,96 | 0,86 | 0,83 | 15,46 | 13 | <,05 | ||||||

| e5 | 2,58 | 0,98 | 0,75 | 0,74 | 14,36 | 15 | <,05 | ||||||

|

e6 |

2,51 | 0,99 | 0,77 | 0,77 | 14,38 | 13 | <,05 | ||||||

| e7 | 2,43 | 0,86 | 0,63 | 0,85 | 16,54 | 15 |

<,05 |

||||||

|

e8 |

2,58 | 0,88 | 0,85 | 0,73 | 16,58 | 12 | <,05 | ||||||

| e9 | 2,50 | 0,84 | 0,95 | 0,75 | 13,24 | 11 |

<,05 |

||||||

|

e10 |

2,74 | 0,82 | 0,82 | 0,80 | 12,34 |

13 |

<,05 |

Source: Elaborated with data study

E: Extract, R: Round, M: Median, S: Standard Deviation, K: Kurtosis, A: Asimetry, C: Category: C1: Acultural, C2: Multicultural, C3: Intercultural; χ2: ji squared, DF: Degree Fredom, P: Level of significance.

It is possible to appreciate a consensus based on the relationships between extracts and categories, but not in terms of collaborative learning between the sources since the first round includes equal or less consensus for the first and second, but favorable for the third category.

That is, the literature consulted seems to agree on differences between acculturation, multiculturalism and interculturalism with respect to the selected extracts, but only for this intercultural category are there consensuses in the qualifications of judges as the evaluation rounds go on.

Ell means that acculturation and multiculturalism seem to be controversial for judges in relation to interculturalism. Entrepreneurial migratory flows seem to be assumed as part of a system of balances between resources and demands, opportunities and challenges, resources and capacities among political and social actors, although the lack of consensus regarding their structure of relationships, communication and motivation seems to indicate that these are emerging phenomena that literature has not been able to assess.

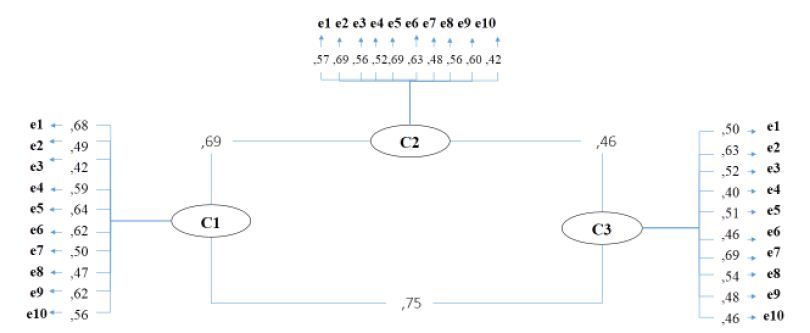

Figure 1 shows the relationships between the categories with respect to the extracts qualified by expert judges in the subject areas.

Figure 1: Structure of Categorical Relationships.

Source: Elaborated wit data study.

E: Extract, C: Category: C1: Acultural, C2: Multicultural, C3: Intercultural; relations between categories and extracts.

It is possible to appreciate that there are relations close to the unity between the categories established by the literature and the extracts qualified by expert judges, although category 2 and category 3 maintain a close relationship to zero, suggesting that multiculturalism and interculturalism are mutually scenarios Exclusive to the entrepreneurial local development.

In contrast, acculturation and interculturalism seem to converge in terms of endogenous entrepreneurial development, suggesting that it is an antecedent and consequent relationship. That is to say, interculturalism will emerge from acculturation and not from multiculturalism.

Discussion

Within the framework of male and female gender relations focused on employment opportunities and capacities, the discussion of the similarities and differences between the concepts of human, sustainable and local development can be located in two indicators of social development: 1) the dignity of life and 2) the quality of life [17], as well as at the institutional level regarding its lack of coordination at the different levels of government, federal, state and municipal [18].

The dignity of life refers to human and social rights as mediators of public action and social necessity [17]. It is to say, it is assumed from the social development approach that the differences of rights between men and women are gestated after both identities, masculine and feminine, are victims of a crucible of violations of their rights. This is so because, even though they are different in their opportunities and capacities, they share common development problems and strategies.

This is the case of quality of life, refers to health; nutrition, housing, education, environment, culture and longevity ([17]: 66). These are opportunities and capacities for access and usefulness of each of these privileges, once again circumscribed between the recognition and ignorance of female identity and masculine identity.

In this way, social development is the product of public and private actions, programs and strategies aimed at dignity and health, reflected in the quality of life, but at the same time part of a vicious circle of similarity (shared problem) and differentiation (development privileges). Therefore, it is necessary to have a state rectory [18].

From this definition of social development, it will be possible to derive the differences and similarities between human, sustainable and local development. It will be essential to establish the definitions, objectives, instruments and goals that distinguish them, since the scarcity or lack of dignity and quality of life is the common denominator [19].

However, it is necessary to consider that the differences related to employment opportunities and capacities between men and women are limited to the imperfections of the labor market ([17]: 66). Therefore, the policies of collection and redistribution will be fundamental to clarify the solidarity that characterizes masculine identities and feminine identities, mainly cooperation oriented to their development [20].

From a matrix around sustainable, human and local dimensions, it is possible to notice differences and similarities if the diagnosis is considered in terms of the absence or scarcity of rights, objectives, instruments and goals (Table 3).

Table 3: Matrix of similarities and differences in development

|

Dimension |

Diagnostics (absence or inefficiency, inefficiency and ineffectiveness of rights) | Objectives (effectiveness of rights) | Instruments (efficiency of rights) |

Goals (rights, effectiveness) |

| Sustainable (generation of health, educational and employment opportunities with an emphasis on social equality: female claim, afro-descendant, indigenist and older adult to overcome poverty) | State dismantling (page 72); lack of leadership of SEDESOL (minute 6:25), federal, state and municipal lack of coordination (minute 4:15), polarization (minute 3:48), social inequality (p.74), containment and reduction of public expenditure (pp. 71 and 72), business exemptions and reduction of state employment ( p.72), discontinuous growth (p.70), limited business contribution (p.71), competition in services and commerce (p.71), state malformation; macroeconomic management (p.72), extreme poverty (minute 3:30), feminization of poverty (p.73) by race and age (p.74), educational lag, access to health, access to housing, income (p. 7:50 to 9:13) | Interinstitutional coordination (minute 6:35) restoration of civil trust (p.72), social integration (p.73). | Social policy: focus, coordinate and influence (minute 4:00 to 5:00), institutional scaffolding (minute 4: 48), public investment (page 71), social dialogue (page 73), representation and governance (p. 72), solidarity and social integration (p.71), governmental responsibility (p.73); transparency (p.73), national crusade against hunger (minute 7:10), popular insurance affiliation (minute 8: 20), subsidy and productive linkage (9: 10) | Sustained growth (p.70). |

| Human (capacity building for dignity and quality of life in health, education and employment) | Mobility requirements (p.66 and 67), institutional precariousness (p.67), informal work (p.68), unemployment (p.70). | Overcoming poverty (p.68), strengthening human capital (p.69). | Universal care (p.67); education (p.66). | Family welfare (page 68). |

| Local (Public and private support and services through cooperative solidarity) | Abandonment of state centrality (p.74), end of assistentialism and paternalism (p.75), political corruption and social untying (p.71), institutional administrative centralism (p.71), scarcity of fiscal resources, monetary precariousness, labor exclusion (p.67), social distrust (p.72). | Employment opportunities (page 66), promotion of positive interactions between cultures and communities (p.75). | Social and economic compensation (p.66), migration and remittances (p.67), social capital (p.66 and 68), solidarity and trust (p.69), promotion of survival strategies (p.69). | Labor stability (p.70) , equitable remuneration (p.66 ). |

Source: Modified from [17,18]

In this way, sustainable development refers to an area in which the State generates opportunities and contributes to the capacities of civil society to reduce inequalities between cultures, localities, communities, families and individuals [21].

If sustainable development orients social equality in order to overcome the poverty of the most excluded sectors, then human development will focus on the promotion of health, education and labor rights in order to establish capacity building that will culminate in the scope of dignity and quality of life [22].

In this way, human needs and expectations will correspond to the policies of strengthening human capital through social care in general and education in particular, generating the desired social well-being [23].

However, the abandonment of the welfare paternalism of the state rectory supposes local policies focused on the reconstruction of the social fabric and the recovery of civil trust through the promotion of solidary and cooperative relations, social and economic compensations, indicated by labor equity and remunerative [24].

In each of the dimensions of sustained development, human and local, the effectiveness, efficiency and effectiveness of rights is the central issue in the state and civil agenda, deriving in cultures, races, gender identities, ages, levels of education and income [25] .

The differences and similarities between the sustained, human and local developments allow observing the inequality between men and women, among other items. This is so, because the problems, objectives, instruments and goals seem to disfavor the feminine identity over the masculine identity not only evidenced in the poor number, but also in the opportunities generated by institutions and companies, which favor a competition logic focused on the conviction of success, an essential attribute of male identity and to the detriment of conservation ethics, a fundamental feature of female identity [26].

In this way, policies of sustained, human and local development, focusing their emphasis on competence rather than solidarity, will favor male identity, but at the same time they not only exclude female identity in the health, education or labor fields. , but also confine the male identity to these areas bypassing the relative to family as is the case of paternity rights [27].

The phenomenon of masculine youth migratory flows can be understood from the asymmetries and similarities between the processes of inclusion and social protection, considering that human rights are the universal and integral implementation instrument [28,29].

That is to say that social inclusion, being an ethics, vocation and discourse of equality, not only implies the exercise of rights in the foundation of programs and strategies, but also is aimed at reducing the barriers that inhibit the construction of citizenship , cohesion, belonging and democratic life. Through administrative decentralization, social recognition, the social pact, the negotiation of conflicts and the expansion of rights for their social redistribution [30].

If social inclusion is reflected in social protection as synonymous with social assistance, then masculinities in their youth and migratory flows would have ample possibilities of being included and protected, but this last question implies social assistance related to progressivity, equality, integrality, institution, participation, transparency, accessibility and accountability [31].

In other words, social and economic rights must not only be guaranteed by the State, they must be inserted in a policy, program and strategy aimed at eradicating inequalities, indicated by their regression in terms of opacity of resources and inaccessibility of information [32].

In this way, the similarities and differences between inclusion and social protection are central issues in the political and civil agenda, mainly in relation to a diagnosis of inequality and social exclusion, as well as in the objectives, instruments and goals aimed at the inclusion of from protection [33].

“Grosso modo” (Table 4), social inclusion is the effect of social protection understood as a policy, program and integral strategy for managing demands and redistribution of resources in order to regulate: 1) social assistance, 2) social security and 3) the labor market [28].

Table 4: Matrix of differences and similarities between protection and social inclusion

|

Dimension |

Diagnosis (lack of efficacy, efficiency and effective rights) | Objective (effectiveness of rights) | Instrument (efficiency of rights) |

Goal (effectiveness of rights) |

| Inclusion (ethics, vocation and discourses of social equality for the exercise of social and economic rights) | Ethics of inequality (p.332), distortion of citizenship (p.332), absence of cohesion, social belonging and democratic life (p.332), | Equality in well-being (page 332), dignity, autonomy and freedom (page 344), democratic participation (page 344), universality of rights (page 346). | Decentralization of responsibilities (page 346), social recognition without distinction of gender, race, ethnicity, age, belonging to specific socioeconomic groups or geographic location (page 332), social pacts (page 333), conflict negotiation (p. 333), expansion of rights (p.333), cohesion and social identity (p.333). | Social redistribution (p.332), discourses of rights (p.332), |

| Protection (Implementation of economic and social rights based on standards of progressivity, equality, integrality, institutionality, participation, transparency, access and accountability) | Policy of social inequality (p.332), regressivity that inhibits the exercise of social and economic rights (p.333), illegality and labor informality (minute 4: 33), multidimensional poverty (minute 6:49), differential needs (p. minute 9: 35), transitional (minute: 9:55) and chronic (minute 10:10), female uniparental leadership (minute 11: 22). Municipal operational technical coordination (minute 17:40), information and opaque management (minute 18:35), | Reduction of social inequality (p.332) from integrality (minute 6:20), identification of demands and guarantee of access to resources (minute: 3:21), promotion of decent work (minute 4:06), focused on income (minute 2: 10), | Universal policies (p.332), horizontal integrality (minute 6:50), vertical administration (7: 10 minute), sectoral transversality (minute 8: 03), institutional coordination (minute 16:40), promotion of human rights; economic and social with an inalienable sense (p.331 and 332), coverage of needs (p.335), conflict control systems (minute 20:15), | Social assistance, contributory social security and regulation of the labor market (minute 15: 10 to 16: 25). Multi-sectoriality of state intervention (minute 6: 49); legal commitments (p.332), social security (p.342) and social assistance (p.342) |

Source: Modified from [28,29]

That is to say that social exclusion, indicated by social inequality and determined by the regression of economic and social rights, is reflected in illegality and labor informality, multidimensional poverty, differentiated needs, and directly impacts single-parent families headed by women; It supposes a lack of technical and operational municipal coordination fed by an absence of informative transparency and accountability, justifies social protection [34].

In this sense, social protection is the implementation of strategies and mechanisms of assistance, security and the labor market as part of universal, comprehensive policies, verticality in its elaboration and horizontal implementation. It implies a sectoral transverse condition; an institutional coordination in the coverage of needs and a control of conflicts between political and civil actors [35].

Understood as a strategy of assistance, security and labor regulation, the differences and similarities between social inclusion as an ethic derived from social protection show that: 1) migrant flows occupy a place in the integration of social protection through demographic bonus; however, 2) migrant masculine identities would only be a priority while they are in a productive age; 3) both migrant flows and masculine identities are more prone to state exclusion, since it prioritizes the sectors of the future [36].

From the intercession model of social work, which proposes the incidence of contextual repertoires on narratives and discourses, fifteen former migrants settled in Xilitla, SLP, in the Huasteca Potosina, were interviewed in order to interpret and establish the influence, they had throughout their journey, stay and return, all this in the face of acculturation, selectivity, identity and governance; as well as before the rationality: economic, multicultural, intercultural and ethnocentric, having as evident background to the enterprising culture of the EU [37-47].

The former migrant traders of organic coffee had an apprenticeship in entrepreneurship based on the transparency of the management of their micro-enterprise. Each peso was used for the development of your business. The merchants without experience in migration had an apprenticeship of the enterprise based on the specificity of their sales. Each weight should be invested in a single product.

A specification refers to the establishment of axes, trajectories, relationships and hypotheses around a process in which the variables reviewed in the state of knowledge reflect a particular context or scenario, but their expected relationships anticipate conflicts and changes.

In this way, a preponderant axis: the integrality of the public policies on the other nodes; diversity, security, activism and co-responsibility. Each path of dependency relationship between each of the five factors allows the establishment of hypotheses that can be contrasted in the immediate future if the theoretical, conceptual and empirical frameworks reviewed in the state of knowledge are fulfilled.

The model proposes the study of entrepreneurial migratory flows based on the leadership of the State through the integrality of social policies, as well as the diversification of social protection and public social security, although in another aspect, movements for social security They propose a co-responsibility in the management and administration of public services in the field of social entrepreneurship.

It is a model delimited by two political and social actors around the establishment of a business promotion system that is distinguished by its degree of social protection, comprehensive strategies, local security and openness to social demands, as well as the construction of a co-government or governance indicated by its degree of co-responsibility.

However, the co-governance or governance scheme also implies the inclusion of other public and private sectors and actors, such as joint-stock companies and cooperative societies. This means that the model is limited to two actors that, although they are the predominant axes of co-government, whose management and administration capacity is regulated by civil organizations and government institutions.

In this way, the selection of indexed sources can be extended to repositories such as EBSCO, SCOPUS, ELSELVIER or SCIELO. This would include variables that explain the dialogue between the governors and the governed in terms of entrepreneurship, mainly in terms of the innovation of development policies.

In the case of the Delphi technique used to analyze the content and its specification in a model, it could be complemented with the neural network technique in order to be able to establish possible scenarios from available data and feasible dependency relationships. It is the same case of the data mining technique, which would delimit the study scenario to a context and space in which entrepreneurship contrasts with protectionism or corruption.

Regarding the model of complex trajectories of interdependence between the factors subtracted from the literature consulted, it is possible to amplify such a model using the logic of structures, which warns measurement errors that can indicate the similarity or difference of constructs in the explanation of a problematic.

Finally, in relation to the works of [9,13], in which entrepreneurship has its origin in local identity, regional roots, attachment to the place, and the sense of community as a substantial part of the uses and customs oriented to profit and profit. Present work rather considers that it is the interdependence between migrant and native cultures that generates an entrepreneurial hybrid, and that although the local identity is its foundation, also the labor expectations that drive the crossing, the stay and the return of migrants is a factor determinant of a migrant’s work cycle.

Subsequently, it is recommended: a) to carry out an intensive processing of information in other repositories; b) adopt other content analysis techniques; c) generate integral models, that include entrepreneurial migratory flows and entrepreneurial spheres; c) as well as the discussion between the historical identity of the place of origin with respect to the labor expectation of the migrant receiving context.

Conclusion

The contribution of this work to the state of the question lies in the establishment of five assumptions that explain the trajectories of interdependence between five nodes or factors used in the state of the matter and specified in a model for addressing entrepreneurial migratory flows. It deals with the integrality, diversification, security, participation and co-responsibility of the political and social actors in the construction of a system of co-management and co-administration of resources and public services related to social entrepreneurship, business development, microfinance or microcredit focused on the localities that receive or boost migratory flows.

The discussion about social entrepreneurship, as a process of state management or administration, or, because of civil participation in self-management and self-organization, is being rethought towards models of co-government, co-management, co-administration and co-responsibility, which they indicate a rapprochement of public administration with organized civil society, but in terms of social protection, policies, strategies and programs are disjointed. Therefore, opening the debate is necessary to establish an integral system of social entrepreneurship, at least between the governors and the governed.

References

- García C (2019) Dimensions of the theory of human development. Ehquidad 11: 27-54.

- Sánchez A, Juárez M, Bustos JMY, García C (2018) Contraste de un modelo de expectativas laborales en exmigrantes del centro de México. Gestión de las Personas y Tecnología 32: 21-36.

- Cruz E (2014) Multiculturalism, interculturalism and autonomy. Social Studies 43: 243-269.

- González M, Iglesias C (2015) Decisions on housing tenure and acculturation of the foreign population resident in Spain. Economic Trimester 82: 183-209.

- Tena J (2010) Towards a definition of civic virtue. Convergence 53: 311-337.

- Carreón J (2013) Discourses on labor migration, return and social reincession based on group identity in Xilitla, micro-region of Huasteca Potosina (Mexico). In L. CANO (coord.), Poverty and social inequality. Challenges for the reconfiguration of social policy. (pp. 153-174). Mexico: UNAM-ENTS.

- Sánchez A, Quintero ML, Sánchez R, Fierro E, García C (2017) Governance of social entrepreneurship: Specification of a model for the study of local innovation. Nomads 51: 21.

- Carreón J (2016) Human development: Governance and social entrepreneurship. Mexico: UNAM-ENTS 143.

- García C, Carreón J, Hernández J, Bustos JM (2016) Governance of risk from the perception of threats and the sense of the community. In S. VÁZQUEZ, BG Cid, E. MONTEMAYOR (coord.), Risks and social work (pp. 71-94). Mexico: UAT.

- Carreón J, Hernández J, Quintero Ml (2016) Specification of a local development model”. In D. Del-CALLEJO, ME CANAL and G. HERNÁNDEZ (coord.), Methodological guidelines for the study of development (pp. 149-168). Mexico: Universidad Veracruzana.

- Carreón J, Hernández J, Bustos JM, García C (2017) Business promotion policies and their effects on risk perceptions in coffee growers in Xilitla, San Luis Potosí, central Mexico. Poiesis 32: 33-51.

- Rodríguez RF (2010) Xenophobic speech and agenda setting. A case study in the Canary Islands press (Spain). Latin Magazine of Social Communication 65: 222-230.

- Carreón J, Morales M, Rivera B, Garcia C, Hernández J (2014b) Migrant entrepreneur and trader: State of knowledge. Tlatemoani 15: 1-30.

- García C (2018) Coffee farming enterprise in migrants from the huasteca region of central Mexico. Equidad & Desarrollo 30: 119-147.

- Campillo C (2012) The strategic management of municipal information. Analysis of issues, their treatment and irruption in the municipality of Elche (1995-2007). Magazine of Strategy, Trend and Innovation of Communication 3: 149-170.

- Albert MC, Espinar E, Hernández MI (2010) The immigrants as a threat. Migratory processes in Spanish television. Convergence 53: 49-68.

- Sojo C (2006) Social development, integration and public policies. Luminar Social and Humanistic Studies 4: 65-76.

- Robles R (2013) Ministry of Social Development. Interview on eleven TV.

- Carreón J, Hernández J, Morales MI, Rivera Bl, Limón GA, et al. (2014a). Towards the construction of a civil sphere of identity and public security. Realities 4: 23-36.

- Carreón J, Hernández J, García C (2015) Migratory identity in the establishment of an agenda. Dialogues of Law and Politics 16: 69-87.

- Fuentes F, Sánchez S (2010) Analysis of the entrepreneur profile: A gender perspective. Applied Economics Studies 28: 1-28.

- García C (2008) The psychosocial dynamics of the migratory communities. Approaches 1: 137-152.

- Gutiérrez R (2013) The linguistic dimension of international migrations. Languages and Migrations 5: 11-28.

- García C, Carreón J, Hernández J, Aguilar A, Rosas F, et al. (2015) Differences in reliability against risk, uncertainty and conflict between coffee farmers in Xilitla, Mexico. Eureka 12: 73-93.

- Long H (2013) The relationships between learning orientation, market orientation, entrepreneurial orientation, and firm performance. Management Review 20: 37-46.

- Rentería V (2015) Socioeconomic panorama of international migration originated in Latin America and the Caribbean: state of the art. University Act 25: 40-50.

- Yepes I (2014) Scenarios of Latin American migration: Transnational family life between Europe and Latin America. Roles of the CEIC 107: 1-27.

- Martínez R (2011) Inclusive social protection: A comprehensive look, a rights approach. Seminar, Argentine social protection in Latin American perspective: inclusion and integrity challenges.

- Cecchini S, Filgueira F, Martinez R, Rossel S (2015) Social protection instruments. Latin American roads towards universalization. New York: UN-ECLAC. 321.

- Rodríguez A (2009) New perspectives to understand business entrepreneurship. Thought and Management 26: 94-119.

- Yuangion Y (2011) The impact of strong ties on entrepreneurial intention. An empirical study based on the mediating role of self-efficacy. Journal Entrepreneurship 3: 147-158.

- Amujo O, Otubango O, Adeyinka B (2013) Business news configuration of stakeholders opinions and perceptions of corporate reputation of some business organizations. International Journal of Management and Strategie 6: 1-27.

- Ariza M (2002) Migration of family and transnationality in the context of globalization: some points of reflection. Mexican Journal of Sociology 64: 53-84.

- Trimano L, Emanuelli P (2012) Social representations and citizen practices in the rural community: A contribution from strategic communication. Latin Magazine of Social Communication. 67: 494-510.

- Ferreiro F (2013) Women and entrepreneurship: A special reference to business incubators in Galicia. RIPS 12: 81-101.

- García C, Bustos Jm, Carreón J, Hernández J (2017) Theoretical and conceptual frameworks around local development. Margin 85: 1-11.

- Sandoval FR, Carreón J, García C, Valdés O (2015) Formalization of dependency relationships between water and social variables for the management of sustainable local development. Kaleidoscope 2: 85-93.

- Anguiano M, Cruz R, García R (2013) International migration of return. Trajectories and labor reintegration of Veracruz migrants. Population Papers 19: 115-147.

- Barrón A (2013) Unemployment among agricultural day laborers, an emerging phenomenon. Development Problems Magazine 175: 55-79.

- Fuentes G, Ortiz L (2012) The Central American migrant passing through Mexico, a review of his social status from the perspective of human rights. Convergence 58: 157-182.

- Gavazzo N (2011) Actions and reactions: Forms of discrimination against Bolivian migrants in Buenos Aires. Journal of Social Sciences 24: 50-83.

- Granados J, Pizarro K (2013) Paso del Norte, how far you are staying. Implications of return migration to Mexico. Demographic and Urban Studies 28: 469-496.

- Izcarra S (2011) Migratory networks versus labor demand: the elements that shape the migratory processes. Convergence 57: 39-59.

- Martínez G (2014) Chiapas: social change, migration and life course. Revista Mexicana de Sociología 76: 347-382.

- Pérez M, Rivera M, Uribe I (2014) Migration from the perspective of employers of an agro-industry in the Altos de Jalisco, Mexico. Social Studies 43: 112-136.

- Sabino J (2014) Internal migration and size of locality in Mexico. Demographic and Urban Studies 29: 443-479.

- Wieviorka M (2007) Identities, globalization and inequality. Puebla: UIA.