DOI: 10.31038/IJNM.2021214

Abstract

Background: Thirty-five percent of all the known workforce in the United States, across all genders, races, and ethnicities are bullied at work. According to the Workplace Bullying Institute (2017) racial/ethnic minorities in the general population are bullied at a higher rate. By estimating that these trends would continue and remain applicable, racial/Ethnic minority female nurses, as a significant subset of nurses, maybe bullied at a higher rate than Caucasian counterparts. While nurses in the United States (US) who are studied in the health workplace are largely women, female minority wellbeing in the workforce is especially understudied primarily because minority nurses are subsumed in aggregate data that represents predominantly white women. There has been a longstanding goal to increase numbers of minority nurses in all areas of nursing practice but in particular in acute care to advance trust and confidence in quality of care with diverse communities served. The need for minority nurses and wanting to understand the experiences that would draw and keep them in the nurse workforce is a significant area in need of study.

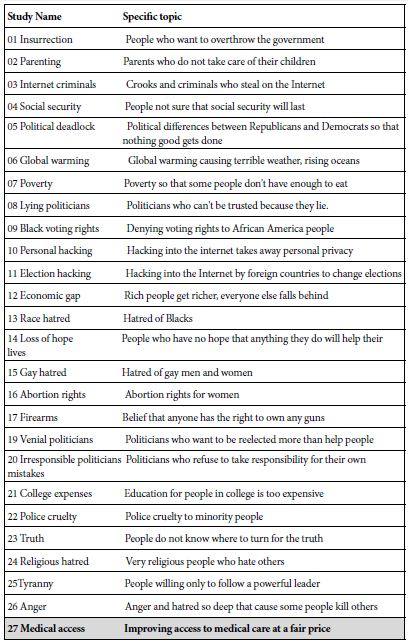

Objective: The objective of this study was to give “voice” to the experience of minority nurses who self-identified as being bullied at work in acute care settings by understanding their experience. Two key areas of exploration were 1) understanding what is experienced and 2) using these data to create an explanatory model that could guide nursing organizations to create a welcoming environment for employment and success of minority nurses.

Design: Face-to-Face semi-structured recorded interviews and survey data including participant demographics and characteristics of professional life and range of support systems in each participant’s personal and professional life.

Setting area hospital(s): The study of nurses currently or formerly employed at Boston, Massachusetts area hospital was conducted at neutral locations outside of the workplace.

Participants: Purposive, typical sampling. Eighteen female minority nurses who work in acute care facilities in the Boston, MA area.

Methods: This study used a constructivist grounded theory method to examine the experiences of self-reported bullying of female racial/ethnic minority nurses in the acute care/hospital workplace.

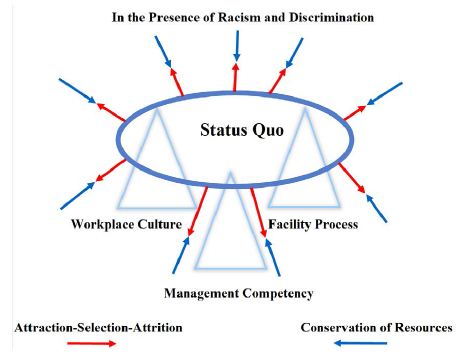

Results: It was found that organizational racism and discrimination foster an environment where WPB against minorities can flourish. The workplace culture and facility processes appear not to mitigate these circumstances. These mechanisms serve to maintain the status quo and allows those with both formal and informal power to maintain control.

Conclusion: Minority female nurses who are subjected to bullying are forced to conserve their personal resources. They respond by becoming silent about their work conditions or by leaving the job. The consequences of this disengagement by a vital portion of the workforce negatively affects the individuals, the organization, and society.

Keywords

Minority nurses, Workplace bullying acute care workplace culture, Constructivist Grounded

Theory

What is Known About This Topic

. Workplace bullying is a burden on the individual, workplace, healthcare system, and economy

. Minorities are bullied at higher rates than others

What This Paper Adds

. Detailed account of the bullied experience of minority female nurses in the workplace

. A theory of the organizational mechanisms that support and perpetuate workplace bullying of minority female nurses.

The full account of this study resides in the University of Massachusetts Boston Doctoral Dissertation Library.

Introduction

Workplace Bullying (WPB) is intentional abusive behavior that is systematic and repeated to intimidate or control a person, therefore, making them a target [1]. This abusive behavior negatively impacts the individual and the workplace [2]. Bullying involves an imbalance of power, which can be actual or perceived between the target and the perpetrator [3]. Bullying behaviors can manifest as either overt acts such as demeaning in public or covert acts such as undermining. Grimes [4] notes that aggressive, abusive behavior leads to negative impacts on physical health and psychological safety, adversely contributing to poor patient care and medication errors.

The Workplace Bullying Institute conducted a study in 2010 and found that 35% of the workforce across all genders, races, and ethnicities reported experiencing bullying while at work. Within nursing, studies report a wide range of prevalence of 31% to 85%. While bullying can occur anywhere in the nursing field, a study conducted by Vessey and colleagues [5] found that it occurred more often in Acute Care Medical-Surgical areas (23%). The Workplace Bullying Institute found that minority groups are affected by bullying more than other groups and further reported that 39% of Hispanics, 43% of African Americans, 51% of Asians, and 36% of Caucasians are bullied (WBI, 2017). The same study reported that females (66%) were affected by bullying more than males (34%). The sample included 1008 individuals African Americans: 120; Hispanics: 130; Asian: 30; White: 681. Women made up 58% of the WPB targets and; Males 42%. Minorities currently make up 19.2% of the nursing population (American Association of Colleges of Nursing, 2020) [6]. The impact of WPB reaches all levels of society. At an individual level, the target experiences escalating stress levels manifesting into physiological and psychological disorders [7,8]. The effect of individual bullying also reaches the workgroup because the target’s ability to optimize the work unit’s contributions is impaired. For the organization, if bullying becomes embedded into the organization’s culture and multiple departments within an organization are affected, the lack of psychological safety caused by WPB prevents the organization from providing optimal care to all patients under their care. The impact of WBP affects healthcare costs. For example, the exact cost of WPB in the United States is unknown; however, in England, the estimated cost of workplace bullying is estimated to be around $3 billion/year [9]. In 2017 the United States spent 17.9% of the total Gross Domestic Product ($3.5 trillion or $10,739 per person) on healthcare. Being mistreated at work lead to a 42% increase in missed workdays in a sample size of 13,807 employees [10] calculated this to be around $4.1 billion. A prominent factor in healthcare costs is health disparities [11]. Since it is conjectured that WPB disproportionally affects minorities and nurses, the phenomenon of WPB becomes a barrier to recruitment and retention to address the factors that lead to health disparities. Retention and recruitment suffer, which may contribute to Hospital turnover, which is on the rise, currently standing at 19.1% [12]. Themes emerge from a review of the literature specific to bullying of minority nurses. First, minorities get bullied in the workplace at higher rates than others. Second, race/ethnicity is a stressor and agonist for WPB [13-15], and third institutional racism permeated the workplace. Workplace characteristics and ethnicity were predictive factors for bullying because it signaled to the workers that the prevailing culture is the dominant culture [14,16]. As a result, minority groups lived in fear of ongoing attacks and or anticipating attacks [17]. There was fear of retaliation. The theory of social identity suggests that minority groups are likely to be targets of bullying due to differences in appearance, communication style, and assimilation into the popular culture [18,19].

Nurses belonging to multiple minority groups experience bullying more than those nurses who only fall into one category of the racial-ethnic minority. Female minorities face challenges not necessarily faced to the same degree as male minorities.

Two questions emerged from gaps in knowledge from the literature:

1) What are the experiences of racial/ethnic minority nurses with workplace bullying? 2) What are the antecedents and consequences of WPB on racial/ethnic minority nurses? A constructivist grounded theory methodology aided in answering these questions.

Method

Constructivist Grounded theory is a qualitative research methodology that seeks to understand a social process where no adequate prior theory exists. It uses an inductive approach to generate a new theory. The theory culminates ideas and constructs operationalized by social structures and processes [20]. Constructivist grounded theory is a useful method to examine individual experiences with workplace bullying to uncover themes to explain and delineate the participants’ experiences.

Participants

The Purposive (typical) sampling technique enabled the recruitment of racial/ethnic female minority nurses who worked in acute care hospitals in a metropolitan city on the east coast of the U.S. (within the last year). Recruitment occurred through word of mouth and posting of recruitment flyers on sites like LinkedIn and Facebook. Nurses were eligible if they met the above criteria and which included: spoke and read English at a 10th-grade level; phone access; employed in an acute care hospital in the Metro Boston area either full or part-time; were aged 21 years or greater; identified as a racial/ethnic minority by definition; had access to a primary care provider. Excluded were those who presented with cognitive impairment, any bullying experience over two years ago, vulnerable populations, males (including minority male), and Caucasian females (see Table 1 Sample and Demographics).

Ethical Review

The study procedure included obtaining Investigation Review Board approval at the University of Massachusetts Boston.

Procedure

Communication with participants first involved the establishment of eligibility and willingness to participate. Next was a review of WPB’s definition and the determination of self-reported racial/ethnic minorities. If eligible, they filled out a written consent, demographics, and other participant information utilizing Qualtrics. A 60–90-minute interview was then scheduled and accomplished by the primary researcher in a suitable location. The interview was audio-recorded and transcribed into a sanitized written transcript. At the completion, they received a $25 gift card funded through the primary researcher’s resources. No outside funding sources contributed to this research. The final communication with participants involved a written brief of the study findings with an offer to discuss the study findings via a phone call. Throughout the study, a reflexivity journal was essential, considering the nature of the content discussed. With the negative emotion often generated, it was necessary to reflect on the researcher’s objectivity. Analysis of the memo log and entries were consistent with the process applied during coding. Memos allowed an overall perspective and guided the putting together concepts and linkages from the data. Memos were crucial to developing the subthemes, hypothesis, themes, and the theory that resulted.

Data Analysis

The data analysis process consisted of coding, comparing, memo writing, sampling, and theory production [21]. The process of coding involved an iterative process of initial coding and focused coding. During the initial open coding stage, the primary researcher reviewed data word by word and line by line. Probing questions guided the understanding of what was emerging from the data. These questions guided modifications to future interviews and coding. Two such examples center on the extreme negativity of the WPB experiences of the participants. One was the need to establish neutral, open coded terms where possible. Another example was to ask the participants if anything good came out of their experience. Research team members reviewed and discussed the coding throughout the coding and analysis process. For this study, a priori sample size initially was set at twenty interviews. Theoretical saturation was determined when three consecutive interviews gave no new concepts. Sampling continued to the point of terminal saturation. The sample size was adjusted [22] to eighteen after no new concepts emerged after the tenth interview. Data saturation was proved with no new concepts emerging after ten interviews however since eighteen interviews were completed at this time all data was included for analysis. An increase from 245 open codes after ten interviews yielded 13 initial axial coded groups or categories. There were no new axial coded groups or categories when increased to 395 open codes after 18 interviews. The categories were adjusted a couple of times, but there were no new meanings encountered. The constant comparison method [19] compared data with data, data with codes, and codes with data. The initial codes were open for modifications, but at the end of this stage, codes that are most frequent and or significant are identified, leading to focused coding where a review of the larger data segments took place. The data formulated into temporary conceptual positions with the application of the framework of axial associations. Data analysis software (NVivo 12) served as the base reservoir of the transcribed data, and Microsoft Excel was the vehicle for the data sorts. Theoretical coding involved analyzing the memos [23] to connect different categories and codes. The constant comparison method aided by the memos’ resulted in a final re-sorting and realignment of the concepts. Eleven final categories emerged, making up three major themes and three transitional or linking categories. Hypothesis aided in understanding the relationship between categories. From this process, the themes and theories were developed and solidified.

Findings

This study consisted of eighteen participants. Table 1. Presents the Demographic data. Participants included seven African/American; five Hispanic American; three Asian American; one Native American, and two identified as “other.” The participants represented a span of work experience. More than half of the participants were married or in committed relationships.

Table 1: Demographics

| Gender |

Number

|

Percent |

Range |

Mean

|

| Female |

18

|

100

|

|

|

| Race |

|

|

|

|

| African American |

7

|

39

|

|

|

| Asian/Asian American |

3

|

17

|

|

|

| Hispanic/Hispanic American |

5

|

28

|

|

|

| Native American |

1

|

6

|

|

|

| Other (English as a Second Language) |

2

|

11

|

|

|

| Marital Status |

|

|

|

|

| Married |

13

|

72

|

|

|

| Widowed |

3

|

17

|

|

|

| Single |

2

|

11

|

|

|

| Age |

|

|

|

|

| 20-29 |

0

|

0

|

|

|

| 30-39 |

3

|

17

|

|

|

| 40-49 |

8

|

44 |

25-65 |

47.3

|

|

50-59

|

4 |

22

|

|

|

| 60-69 |

3

|

17

|

|

|

| Educational Level |

|

|

|

|

| Doctoral |

2

|

11

|

|

|

| Masters |

5

|

28

|

|

|

| Bachelor |

10

|

56

|

|

|

| Associate |

1

|

6

|

|

|

| Diploma |

0

|

0

|

|

|

| Employment Status |

|

|

|

|

| Full Time |

18

|

100

|

|

|

| Part Time |

0

|

0

|

|

|

| Practice Area |

|

|

|

|

| Med/Surg |

5

|

28

|

|

|

| ICU |

1

|

6

|

|

|

| Prenatal |

1

|

6

|

|

|

| Other |

11

|

61

|

|

|

| Position Held |

|

|

|

|

| Staff |

10

|

56

|

|

|

| NP |

1

|

6

|

|

|

| Supervisor |

0

|

0

|

|

|

| Administer |

6

|

33

|

|

|

| Other |

1

|

6

|

|

|

| Employment Years |

|

|

|

|

| 1-3 Years |

3

|

17

|

|

|

| 4-6 Years |

1

|

6

|

|

|

| 7-9 Years |

1

|

6

|

|

|

| 10-12 Years |

2

|

11

|

|

|

| >12 Years |

11

|

61

|

|

|

| Static/Float Role |

|

|

|

|

| Static |

16

|

89

|

|

|

| Float |

2

|

11

|

|

|

Characteristics of the participants related to their professional life and the range of support systems in each participant’s personal and professional life are in Table 2. The personal support system includes four types of supportive behaviors: emotional (expressions of empathy, love, trust, caring), instrumental (tangible aide), informational (advice, suggestions, and information), and appraisal (assists with self-appraisal) [24]. Seventeen participants reported receiving personal emotional support, with 13 (72.2%) listed as very supportive, while only 3 of 18 (16.7%) received very supportive professional help. None reported personal nonsupport. Six out of 18 (33.3%) did list professional support as unsupportive.

Table 2: Support Systems

| Support Type |

Number

|

Percent

|

| Emotional |

17

|

94

|

| Instrumental |

9

|

50

|

| Informational |

14

|

78

|

|

Appraisal

|

10 |

56

|

| Personal Support Rating |

|

|

| Very Supportive |

13

|

72

|

| Somewhat Supportive |

5

|

28

|

| Neither Supportive now Unsupportive |

0

|

0

|

| Somewhat Unsupportive |

0

|

0

|

| Very Unsupportive |

0

|

0

|

| Professional Support Rating |

|

|

| Very Supportive |

3

|

17

|

| Somewhat Supportive |

7

|

39

|

| Neither Supportive nor Unsupportive |

2

|

11

|

| Somewhat Unsupportive |

3

|

17

|

| Very Unsupportive |

3

|

17

|

A rich database from the interviews yielded the following results. Table 3 revealing participant’s reflection of what the experience meant to them and how they dealt with the effects of WPB. The selected samples of direct quotes from participants have been organized around three themes with the categories as links, merging to form a theory.

Table 3: Data Analysis

| Themes |

GROUPS |

Axial Association |

| Organizational Injustice |

Racism |

A, B |

| Discrimination |

| Exclusion |

| Transition |

Opportunity |

C |

| Organizational Stability that Fosters WPB |

Facility Process |

C, D |

| Workplace Culture |

| Management Competency |

| Transition |

WPB Acts |

A |

| Survival |

Effects of WPB |

E, F |

| Coping |

| Transition Back to Organizational Stability |

Silence |

F |

| Phenomena that relates to the actions and interactions of WPB |

A |

| Causal conditions that resulted in the occurrence of WPB |

B |

| Attributes of the context of the WPB |

C |

| Intervening conditions that influence WPB |

D |

| Actions and interactional strategies participants used to cope with WPB |

E |

| Consequences of actions and interactions |

F |

Organizational Injustice

First is the theme of organizational injustice, defined as instances of employees perceiving organizational actions, policies, decisions, or messaging to be unjust or unfair [25]. These are instances where employees perceived that they were mistreated compared to other employees, including actions that stemmed from feelings of superiority, inequality, or racism. The theme of organizational injustice includes three subthemes of racism, discrimination, and exclusion. Examples from the data representing these three subthemes follow.

Racism: A participant described a coworker whose actions conveyed aggression and hostility based on the participant’s race. The coworker’s actions conveyed racism. A participant noted:

“Comments would be made about anybody that’s of African American race; that they were dumdums and slow. Whenever there is African American or black nurses or nursing assistants in the classroom, she would say they will never get it; they are not going to get it. Those people are always slow. She said black people are known to be slow. She said those very words.”

Discrimination: A participant observed selection for positions based on race:

“Right. So, the group of people that are getting these positions, and that can exercise this power. They are all white, But if it is a white person, then things get a little bit smoother, so you know what is going to happen based on the color of the nurse.”

Exclusion: The race or ethnicity-based discrimination and exclusion experienced by these participants is ubiquitous and ongoing. When individuals work for organizations that exhibit organizational racism, they can feel isolated or excluded from cooperation, social, training, or advancement opportunities.

Another participant started with a classic example of suppression of opportunity when directed not to present a project she had completed for her work unit:

“My assistant manager even did not want to allow me to present it. Wow, who is now still there? So, after the meeting, she said, ‘Oh, who wants to hear what N4 has to say.’ She was reluctant to allow me to present.”

The three subthemes are deeply interconnected, as organizational racism can be the root cause of both discrimination and exclusion. These data revealed the possibility that discrimination may occur throughout the organization during employee hiring, salary negotiations, training opportunities, and consideration for advancement. Discriminating against individuals in a minority group results in their exclusion from opportunities. The exclusion occurs via a deliberate “control of opportunity,” leading to the second theme maintaining the status quo.

Organizational Characteristics that Foster Bullying

The second theme relates to organizational characteristics and processes that foster bullying of female minority employees. There are three subsections of the facility process, workplace culture, and management competency. Many participants discussed the lack of resources to help with the experience of WPB. These resources include collective bargaining (union activities) and other employee assistance entities and the lack of management ability to understand and mitigate the situation. The notable facility factors highlighted to be inadequate included ineffective advice or assistance by employee assistance entities.

Regarding the effectiveness of the Union and other facility entities, a participant said:

“They implemented a couple of years ago, maybe last year,… a website… an anonymous website that you could go in. You do not have to go to your manager because we figured that the manager does not help, and H.R. does not help, and the Union does not help”.

When facility processes fail to result in productive actions, participants report it being a barrier to reporting problems. A participant illustrated how limitations in time constraints are a barrier to reporting issues:

“Because EEO, at this hospital, you have to file a case within 21 days. It seems to me everywhere it is more than a few months. My lawyer had to write them, and they should excuse the time limit. Anyway, the system they have in place is rigged.”

Next is the workplace culture, which exists within the context of racism, discrimination, and exclusion. Workplace culture includes the subcomponents of teamwork, workload inequities, cliques, and informal power.

A participant stated that some managers found bullying to be humorous and were unable to take behavior issues seriously:

“There was another scrub he did not like because he had an accent. They had a physical fight. This is the culture I was in. When the manager came in, she was smiling, not taking it too seriously. It was fun for them.”

A participant demonstrated the normalization of bullying in the workplace:

“She got away with it because nobody was reporting it. I guess that was a cultural norm from what I heard, and that is how they always are. So, it was like cultural acceptance, a cultural norm”.

In the workplace, the objective of teamwork is to support the outcome of the work product. Cliques in a workplace, however, are formed to meet the individual needs of the workers. Participants in this study frequently spoke of race/ethnic-based cliques, which develop out of the need to improve a sense of control or power over their environment.

A participant described a clique at a granular level and how it impacts teamwork and team reliance.

“So you just get those other black nurses to help you. I remember days like; you come in ‘oh my God, I hope there’s somebody that looks like me. I hope there’s another black person here.’ And that’s what we are always saying under our breath.”

Workplace culture comprised accepted and repeated behaviors because they served some function that maintains the existing structure, even if those behaviors are detrimental to some people. Considering the workplace culture, its influence in perpetuating WPB is evident. Inasmuch, it is essential to look at the processes within the healthcare institution’s culture and structure, including management, leadership, and limitations of opportunities for participants. Informal power emerged as a critical component of workplace culture. Informal power is that which results from relationships that develop in the workplace. Informal power is obtained from relationships that employees build with each other and may come from additional influences such as intimidation, fear, and self-entitlement [26]. When a group of lower power individuals is combined with one of higher power the outcome of work teams suffers. The group begins to feel vulnerable and becomes aware of the power inequity raising intra-team power sensitivity. Resource threats in the group such as assignments, workload, unequal application of tardiness rules, and external resource threats such as budget cuts and layoffs bring forward intra-team struggles. This dysfunction results in adverse outcomes for team performance, organizational efficiency, and patient care [26].

Employees with no formal authority were able to wield influence over other employees supported informally by the workplace. Participant said:

“I did have a coworker like that. It was kind of interesting because she was a friend with a couple of managers. And she would talk about how, ‘Oh, I’ll just see her tonight. I’ll talk to her later, regarding….’ She would always give you the impression that they were going out for drinks after work.”

The third of the three subthemes is management competency. Many participants do not directly challenge management’s competency; however, analysis of remarks points to this as a factor in their WPB experiences. Managers are responsible for the work environment that optimizes the quantity and quality of work accomplished [27]. The failure to create this environment can negatively impact the employees’ well-being and health and the work output. The loss of credibility of the manager based on their actions is an example of this. One participant stated:

“Earlier on, there had been a case where people had been stealing time, and it came to fruition with the awareness of Central Office. And they did an investigation that they charged that manager and her assistant with manipulation and stealing of time.”

Evidence that management is unwilling or incapable of acting appropriately or doing the right thing is the source of participants feeling disheartened and discouraged. A participant said:

“I tried to inform the Chief Nurse. That is when I realized that she might be part of it. Because nothing was ever done. I went to her when it happened. And then it was like what I told her, somehow was worked into my [doing the] bullying”.

Specific to race, ethnicity, and management cultural competency, Participant illustrated a management deficit: “So, I think it was a lack of understanding of me as an individual and a lack of respect of me as an individual.”

Some participants reported experiencing instances of their managers “gaslighting” them. The term “gaslighting” refers to one individual’s ability to erode the sense of another’s reality (Arabi, 2019). One participant spoke of staff that got together to come up with a typical story regarding a conflict at work:

“The manager says, ‘I need to hear from his side.’ And then the surgeon and other nurses got together and wrote me up. So, that is not the first time the surgeon demanded, and they all agreed. So, they said they all kind of coordinated. And the manager was very happy to get them on her side.”

An essential part of “gaslighting” and worthy of separate mention is false accusations. These set the stage for building a manufactured narrative about a target of WPB. A participant addressed this when accused by a supervisor of keeping a personal logbook about people’s activities in her office:

“You can call the police right now and have them search like there’s nothing there. It’s not true. Then I found out from another colleague that everybody had been asked about their interactions with me. So, I was asked to leave, and I was told there’s a GYN position, right, you can take. And the irony of it was at the beginning of that same meeting; I was accused of refusing to see female patients.”

Survival

Last is the theme of Survival, which includes two subthemes: Effects of Workplace Bullying and Survival. Effects of workplace bullying describe the lived experience of female minority nurses regarding the reported WPB effects and serve as a validation that participants‘ descriptions of their experience correlate well with existing literature regarding the effects of WPB. Fifteen of eighteen participants interviewed for this study reported suffering from anxiety and stress. A participant said,

“I think… at first it was just…it started as nervousness and a little bit of anxiety of like, ‘Oh, I have to be perfect and like do everything right.” Another participant explained:

“I kept records, and when I went to report it initially to the Director with the first incident, and he asked me if I wanted to go back to my department. And I said ‘no,’ because I couldn’t even walk down that hallway without getting a dry mouth and having my heart race.”

Another consequence of WPB is the effect of dehumanizing the victim. This aspect is often associated directly with the person’s ethnic or racial minority status. A participant experienced the following where a coworker deliberately referred to her by the wrong name:

“I will tell you what happened one day, the same surgeon that I told you who physically grabbed me…called me Natasha. He would call me Mila one day and Natasha, making fun of me and making jokes about my accent. And one day, I will never forget, he went around and said, ‘Look Mila’ and I said, ‘I am Natasha.’ So, I tried to make some jokes to get through this, but you get fed up with this.”

A Native American participant revealed that the impact of workplace bullying was demoralizing and dehumanizing:

“I remember going to the ‘bed meetings,’ and my counterparts would make the whooping noise to make jokes about Native Americans, and I just ignored them. And I didn’t realize that they were in the process of demoralizing and dehumanizing me.”

The effects discussed above demonstrate that these participants went through matches the effects and consequences of WPB, as reported in the literature. What is more, these events show context for their overall experience and why they had to attempt to cope with their lives and livelihoods.

Survival includes examples of coping. A significant finding of the study was that when minority female nurses are in workplaces where bullying routinely occurs, they can reach a point where they acknowledge that the bullying is unlikely to stop or change, regardless of their actions. Every participant had statements coded that related to coping. The interview results related to coping included emotion-focused coping, referring to the regulation of emotions generated by bullying events like anger or frustration, and problem-focused coping, referring to an effort to solve or mitigate the problem or avoid the problem in the future. It was clear from the following results that problem-focused coping far outweighed emotion-focused coping.

For one participant, the emotion-focused response was to cry, which represents a release of sad, frustrated, or otherwise negative emotions,

“And then after that, I start to cry because it’s, you know, bullying and bullying, bullying, I think that crying is the best thing. But I cry so heavily, you know, I felt like, how am I going to work tonight?”.

Prayer and other spiritual guidance aspects are the most frequently cited example in the emotion-focused coping category. Prayer is well established in human history as a mitigation strategy for stressful situations, and this continues into these examples from bullied minority female nurses in the workplace. A participant described using prayer and faith to get through the day: “Praying works for me all the time. So, it’s the prayer that’s kept me at work up to today. It works for me. I tell you 100% yes to that. And that’s what gets me through.”

The consistent exposure to the WPB experience and lack of assistance from any external source left the participants working out how to survive their receiving treatment. Having no control over external factors, they turned to an internal factor they could control: to go silent about the treatment and or leave their position.

Problem-focused coping was concentrated on the strategy of silencing-the-self or leave the job. All participants made remarks about leaving the job where bullied, going silent about the bullying, or both. There is no ambiguity with many of the WPB participants driving their intention to leave that job. A participant stated: “Oh yes, right, this is why a nurse left the ward. I become the next target. And I decided to leave. This is why I left because you don’t attack me professionally.”

A response from another participant showed the desire to get away from the bully, “So, I knew the only way to get out was to apply for a different department where she would have no control.” When the interviewer asked, “What do you think would have happened if you had to stay in the same position?” her response was, “I knew I was going to quit.”

Repeated WPB experiences were behind a participant leaving other jobs as well:

“I’ve left jobs because of bullying. I left the ICU position because I didn’t have ICU experience. I wanted to learn the ICU, and I had a nurse there, she was my preceptor, and she was just so, so mean and nasty.”

In the absence of mitigating circumstances, the WPB experience’s effects led directly to all eighteen participants’ decision to go silent and or leave the position where bullied.

Discussion

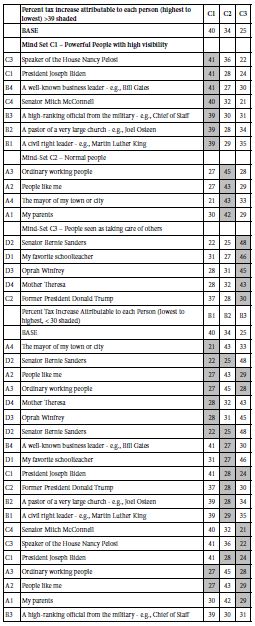

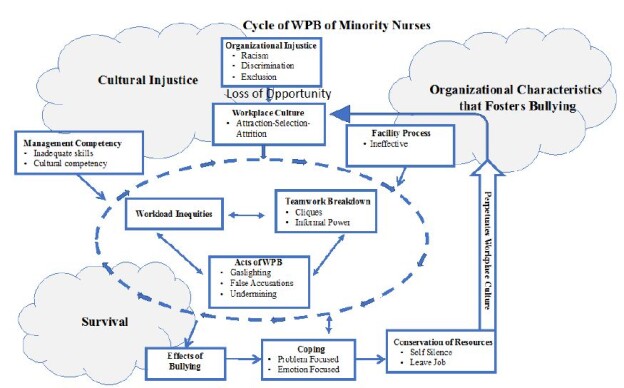

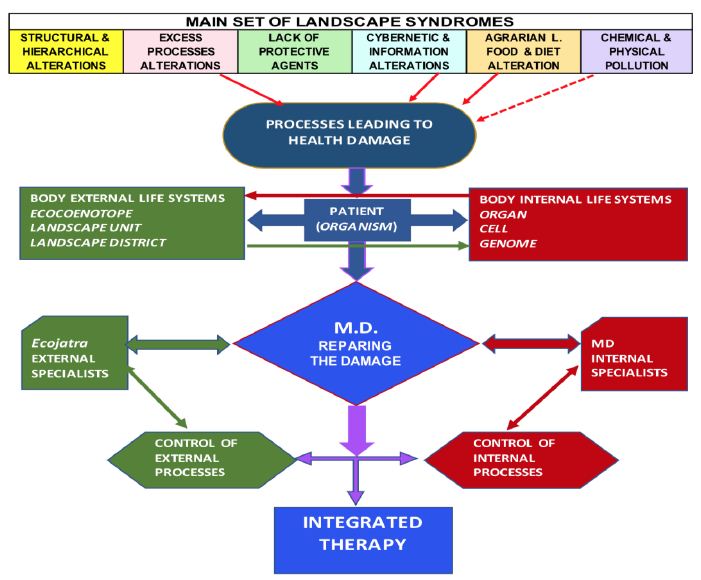

The purpose of this constructivist grounded theory study was to examine the overall experiences of self-reported bullying of female racial/ethnic minority nurses in the acute care/hospital workplace in their own voice through dialogue. Three significant themes describe the antecedents (cultural injustice), contributing factors (organizational stability), and the consequences of bullying (Survival) for the participants. Components of workplace bullying reveal a workplace environment and facility processes that synergistically form the context for experiencing bullying. Workplace culture, the overall work environment, the lack of teamwork, and the formation of workplace cliques represent the structure that makes workplace bullying possible. The participants described the processes that allow WPB to occur, including leadership passivity, lack of facility resources to support those experiencing WPB, deployment of informal power through favored persons as perpetrators of bullying, the vanishing of professional opportunities for those targeted, and sabotaging the quality of work of minority nurses. Ineffective organizational oversight was described that allowed workplace bullying to occur repeatedly while bullying and various coping strategies used against it resulted in self-silencing or leaving the job. The current literature on workplace bullying indicates that racial or ethnic minorities experience bullying more than non-minorities (WBI, 2017). However, contemporary literature lacks sufficient rigor on the racial/ethnic minorities’ perspectives and the circumstances surrounding their experiences. The purpose of this study was to bridge the gap in the literature by examining the experiences of female nurses who self-identify as racial/ethnic minorities that have faced bullying in an acute care hospital setting. This study aimed to understand how these experiences are unique to racial or ethnic minorities and describe specific factors that give rise to these unique experiences using a rigorous type of research inquiry. Understanding these unique bullying experiences and addressing the factors leading to bullying of racial/ ethnic minorities in acute care settings will have numerous benefits to society. The literature illustrates that health outcomes improve when nurses’ racial and ethnic makeup represent the communities they serve. However, if these same nurses are being bullied at higher rates, stripped of their voice, the attrition rate will outpace the replacement rate. The quality of care received by the corresponding patient population cannot improve. Understanding this group of nurses’ workplace bullying experience is essential for creating a supportive place to work. Three themes emerged from the data. These three themes and their subcategories describe the workplace bullying experiences of female minority nurses. They also describe the organizational factors that propagate and perpetuate bullying of these nurses. Figure 1 illustrates these mechanisms. This figure illustrates the mechanism of the perpetuation of workplace bullying in the nursing workgroup. From this view, we can focus on the role of organizational culture and the finding that within an environment fostered by the workplace culture, management competency, and facility process are the breakdown of real teamwork, the rise of cliques, and the inevitable workload inequities that result leading to the acts of WPB. There is a breakdown of collegiality and a lack of a common goal impacting the organization’s output. Coping with silence or leaving the position was the universal result.

Figure 1: Cycle of Workplace Bullying of Minority Nurses

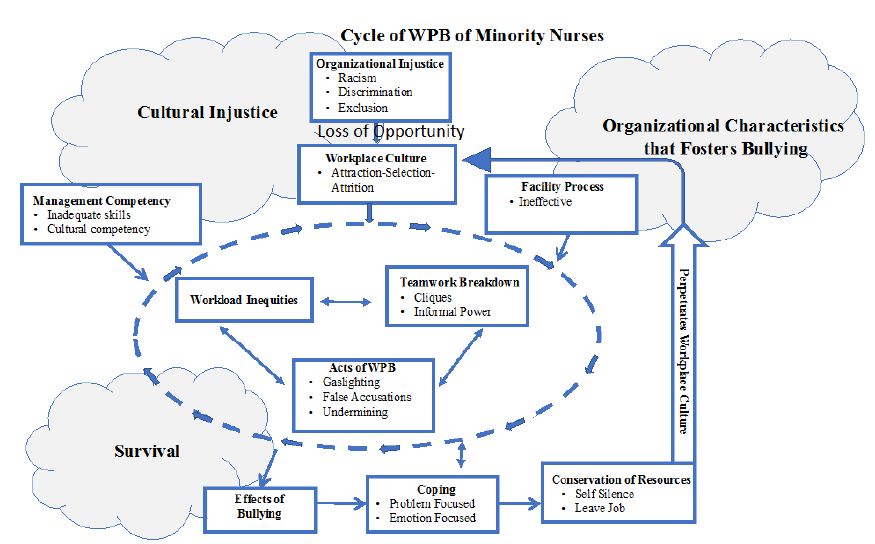

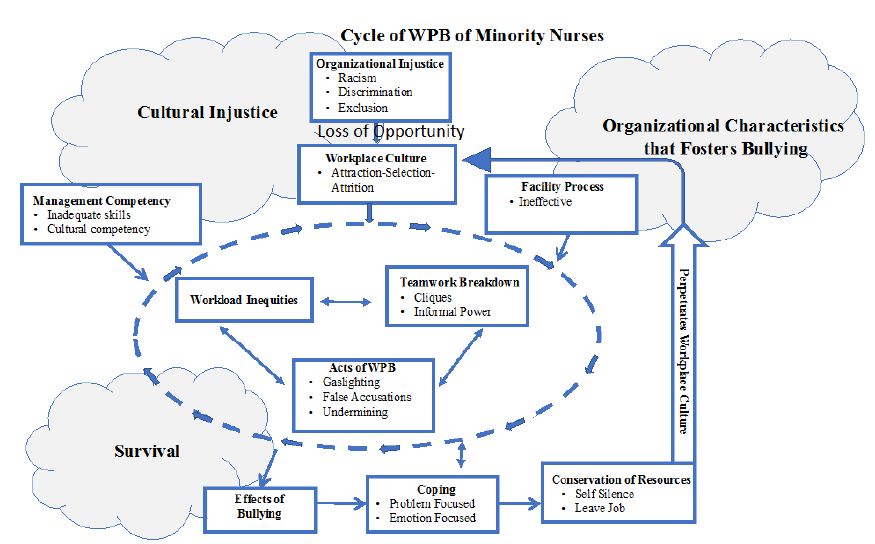

The three themes and their relationship with each other revealed the core social process of bullying, maintaining the status quo through the deliberate attraction-selection-attrition of employees. Bullying maintained the status quo by perpetuating a culture where anyone who did not fit in with the dominant group of the organization was left with a choice to leave the job or become silent. Racism, discrimination, and exclusion make up the theme of organizational injustice, which results in the unfair allocation of opportunity for minority nurses. Racism and discrimination are foundational in all workplace settings, but the degree and how it is manifested may differ. Organizational injustice forms the backdrop and is a precursor for elements within the workplace culture to include facility process and management competency that did not function in a way that could stop or even significantly mitigate these actions. Facility processes were not effective mechanisms for surveillance, to assess the overall workplace culture, or to manage reports of WPB occurrences. One explanation for this could be the attraction and selection of employees that match the status quo in concert with the attrition of the minorities viewed as outliers. The victims of WPB had two options: to leave or be silent if they stayed. In this study, silence or to leave was functionally the same action as either helps maintain the status quo. Those who did not fit in could and did push back but only to the extent that they had personal and professional resources available. These mechanisms describe the theory of structural-functional bullying in nursing Figure 2.

Figure 2: Maintaining the Status Quo

Academic literature supports organizational injustice findings [28,29] stated that racism is the initial framework from which discrimination and exclusion can build. In a racist workplace, individuals are far more likely to be excluded and discriminated against [28,29] found that racism by individuals with hiring authority reflected the type of employees they select and to whom they provide promotional opportunities to. At an institutional level, racism becomes depersonalized. The lines between racism, bullying, and discrimination became blurry, and the inability to hold any person or entity directly accountable makes it challenging to address [30]. Workplace Characteristics that Promote Bullying, the data analysis shows that participants experienced flaws in facility processes such as confidential reports being shared with subjects and unions or human resources representatives failing to follow up on bullying reports. Additionally, workplace culture elements fostered bullying and occurred in a spectrum of minimizing complaints to enabling an outright hostile work environment. Participants reported a culture of employees protecting themselves and securing an environment that unfairly blames some employees. Finally, participants reported experiencing issues with managers who lacked credibility or managers who relied on bullying to force employees’ compliance. The attraction and selection of like-minded people that fit the dominant culture and the attrition of those that do not fit in explain the mechanism for workplace culture formation. The Attraction-Selection-Attrition model explains that organizational culture, and the social structure that emerges from it, is built and formed over time by the individuals within that organization. Facility processes such as the Union or other employees’ resources were inadequate to address reports of bullying. In theory, facility processes were in place to improve employee fairness, satisfaction [31,32]. Two typical facility processes in play here were union support for the nurse and the facility process for reporting issues detrimental to the organization and its people. The findings, however, showed little to no positive outcomes of these processes.

Managers in charge of workgroups were unable to mitigate bullying. Managers were recruiting bullies to collect information and bully others. They thrived in a culture of chaos where the employees were fighting with each other. Lack of cultural awareness and management competency may be an agonist for the prevalence of WPB against minorities.

Factors working together made up the workplace structure and culture, including the global environment, management competency, and cliques considered teamwork. These factors, when combined with facility process factors, set the stage for acts of WPB. Organizational complicity allowed the cliques to flourish, permitting discrimination and informal power by individual staff-level employees. Bullying action was allowed within this context, including tactics of gaslighting, false accusations, favoritism, exclusion, and undermining. These structures and techniques tended toward organizational stability though favoring the status quo. WPB was not inhibited, which in turn perpetuated a climate of bullying. The workplace culture that came forward in this study demonstrated how the current environment empowered bullies. Also, the same processes channeled bullying acts because bullies were protected. The result squelched opportunities and destruction of professional dreams that remained out of sight until the individual stories brought it out. The workplace culture demonstrated a contradiction between a caring environment’s expected nature and surface civility, with the participants’ aggressive, non-caring behaviors. As a result of the workplace characteristics, bullying acts were allowed to go on, causing participants to go into a survival mode as they tried to cope with the effects. Consistent with appraisal theory, Survival involved both emotion-focused coping and problem-focused coping. Resulting actions included deliberate attempts at resolution from which silence and leaving became the most common form. The nurse’s choice to consciously become silent seems to result from the desire to control the situation by conserving resources. The concept of resilience can be a factor for participants going through these traumatic events. On the surface, resilience is a term used to denote someone exposed to challenges but can adapt and move on. In biological theory, it involves the concept of natural selection and the phrase “survival of the fittest” [33]. The implication is those who should survive do end up surviving. Resilience [34] can have a positive connotation. Our society values this trait in people [35], but this view does not adequately explain these participants’ experiences with bullying and its aftermath. The self-silencing is not a form of resiliency and does not demonstrate acceptance. The silence is a deliberate effort to conserve resources. Self-silencing represents a functional mechanism to carry on. This study has shown that nurses may be erroneously viewed as “resilient” when, in reality, they may just be avoiding the “stigma” associated with getting bullied. This form of silencing occurs due to the limited energy available to minorities to counter the repulsive force and change the status quo. The minority nurse’s operational decision was to conserve resources and rely on personal support mechanisms to carry on. The self-silencing manifested in ways that were not mutually exclusive, including silence about how one was treated at work in their current position and being silent while leaving the job to take action against bullying. The nurse’s choice to consciously become silent seemed to result from the desire to control the situation by conserving resources. It emerged that self-silencing was mutually beneficial in the short term for both the participant and the organization. In contrast to the individual level experience of self-silencing, maintaining the status quo perpetuates the workplace culture. The status quo is supported by those who bully and self-silence or leave the job. In discussing the themes, another relevant concept is the concept of intersectionality. Kimberlie Crenshaw defines intersectionality as how race, class, gender, and other individual characteristics “intersect” with one another and overlap to influence societal and interpersonal interactions [36]. Intersectionality requires that consideration of the uniqueness of each individual and their personal experiences. As intersectionality became more complex for the participants (i.e., female, black, religious minority), the likelihood of being mistreated from all sources grew. This study’s revelation, needing further exploration in quantitative studies focusing on isolating related variables, separates the perceived impacts of race, gender, and unrelated personal quality on workplace bullying. Many individuals in the study perceived bullying instances to have a racial component, but others may have included a gender component. Women face bullying in the workplace, and individuals belonging to minority groups experience bullying in the workplace, so that those female minority nurses may experience bullying differently [37].

Implications for Policy

Health inequities and health disparities are a significant economic burden on government. For example, while the healthcare costs account for 17% of the gross domestic products, the health care quality in the United States is the lowest among all other industrialized nations [38]. With the increase of minorities in the U.S. population, examining minority nurses and the workplace’s specific challenges is essential in our society’s evolution. Minorities will soon become the majority of the U.S. population. Reducing WPB against minority nurses has ramifications well beyond the proper treatment of individuals. Evidence in the literature shows that improving the influx of minority healthcare workers may remedy the growing health disparities. To retain minorities in the healthcare space, federal governments, and organizations could consider instituting an anti-bullying framework. It is important to frame these findings with the quadruple aim of the Institute of Healthcare Improvement (IHI) for the future success of health care systems worldwide (IHI 2017) [39,40]. In keeping with IHI’s triple aims of excellent quality of care at an optimized cost while improving the health of the population served, one would argue that bullying’s organizational support provides a fertile ground for bullying to occur. Care suffers for both the nurse and the patient, increasing medical errors and decreasing the nurse’s sense of self. Increased turnover and other errors drive up the cost of care. This environment undermines the trust between the frontline nurse, the administration, and the public they serve. IHI’s fourth aim involves improving the work experience of healthcare workers. It links patients’ healthcare experience to the nurses’ overall work experience [41], underscoring the urgency of developing WPB mitigation strategies. Strategies could start with resources to improve cultural competency, focusing on implicit bias, multiple reporting avenues, awareness and training, building a functional support system, and assessing practical teamwork barriers in nursing. It is reported in the literature that many employees are afraid of reporting bullying incidents for fear of reprisal [42,43]. Multiple reporting avenues provide options for employees to select the reporting mechanism with which they feel most comfortable. Anonymous reporting mechanisms should be made available. Many employees perceive that their workplace structure supports a bullying culture [3,44]. It is essential to start, however, to build a culture of trust for employees. Awareness and training are a start to this. As organizations initiate intervention strategies, it is essential to note that reported bullying’s initial frequency and intensity may increase due to heightened awareness of bullying [45].

Study Limitations

This study has several limitations. One limitation is inherent to qualitative studies, in that it is not able to establish correlation or causation between specific variables. The participant sample for this study was appropriate for a qualitative study but too limited to be representative. The findings in this study are not applicable to all nurses, all female nurses, or even all minority female nurses. To establish causation, further studies would need to conduct randomized control trials which are representative of the population they include. However, the workplace factors such as cliques masquerading as teamwork can form the basis for intervention research utilizing model for improvement framework. Similarly, another limitation is the focus on female-only population. While the importance to understand the experiences of all groups of employees to isolate all factors that make up the multidimensional nature of WPB was perceived, this study focused just on female minority nurses due to their exposure to the microcosm of societal and organizational factors that are unique to female experience in a male-dominated society. These dominations operate to silence their voices. Furthermore, even within female participants, there are cultural variations within minority groups that could not be fully explored in a pilot study of this size. In order to fully understand the experience of minority nurses with workplace bullying, it would be important to compare male perspectives and identify areas of similarity and differences. Another limitation of this study was a lack of focus on individual attributes and how they interact with their coworkers. There are many factors which contribute to workplace bullying, including cooperation style, communication style, individual preferences, and inherent characteristics like race or gender. Without understanding the characteristics of the individual nursing being bullied and the individual doing the bullying, it is challenging to understand why bullying occurred and how it could be prevented in the future (Pallesen et al., 2017). Further studies could consider isolating variables which contributed to bullying, which may include the intersectionality of race, gender, and ethnicity and the WPB of nurses.

Conclusion

The constructivist grounded theory method provided a framework to guide participants in examining their bullying experiences in the acute care workplace. A significant finding was the extent to which racism and its companion concepts of discrimination and exclusion are connected. The summation of organizational processes and the participants’ use or non-use of resources revealed a workplace culture focused on maintaining the status quo. Three factors that supported this were workplace culture, management competency, and facility processes. Resistance from those that did not fit-in occurred only to the extent that they had personal and professional resources available. Many participants discussed the lack of resources to assist them in dealing with the environment. All participants made remarks that consisted of either leaving the job or going silent about the bullying. The consistency of such comments across participants clarifies that these coping-related responses, leaving the job or silencing, were crucial aspects of their WPB experience and how to carry on in its aftermath.

This study’s results support the Institute for Healthcare Improvement’s Quadruple Aim Initiative to improve the health of populations, enhance the experience of care for individuals, reduce the per capita cost of health care, and in particular increase the quality of the work experience for healthcare providers by allowing them to attain joy in work (IHI, 2017). Workplace psychological safety and the essential component of cultural competency are integral to improving, rebuilding, and reshaping workplace culture. By promoting cultural competency within its structure and processes, an organization could create a psychologically safe environment for all employees. Also, focusing on attaining joy in the workplace through psychological safety would create an environment where minority and all nurses would want to work, succeed, and flourish.

Funding

No external funding was used for this research.

Conflict of Interest

There are no conflicts of interest with the authors of this research.

Interview Guide

1. Tell me about your experience with workplace bullying?

2. The Bullying that you experienced: Was it an attack on you, personally, against your professionalism/competence, or against you by affecting your work tasks?

a. Personally

Did you have a personal relationship with the bully?

Did you or the bully try to have a personal relationship with each other?

Did the bully ever directly threaten you?

What do You Feel Now?

Are You Able to Move On?

b. Against your professionalism/competence:

Were there attempts to discredit you? Give examples

Do you feel that this has impacted your professional career?

Do you feel that this has impacted your personal life?

Do you feel that this has impacted your health?

c. Against you by affecting your work tasks:

3. Were there attempts to limit or otherwise interfere with your work? Give examples

4. Did this make you change anything you did? How?

5. Upstream Factors

a. Did your workplace tolerate behaviors consistently?

What were some examples of differences?

How did that make you feel?

What if anything, did you do because of this?

6. Did your workplace reward staff consistently?

a. What were some examples of differences?

How did that make you feel?

What if anything, did you do because of this?

7. Did you observe cliques in your workplace?

Did cliques have influence over decisions that affected your work there?

Did you feel pressure to join a clique?

Did this change anything you did or didn’t do at work?

Did this change how you felt at work?

8. Did you observe people attempting to exercise more authority than you thought they had?

a. Was this known to higher authority?

Did higher authority tolerate this?

Did this directly affect you at work?

Did this indirectly affect you at work?

9. Did you observe people at work ever deliberately violate known policy or procedure?

a. Did it affect your work?

Did it affect you?

Did it make you change anything you did at work?

What do you feel now?

Are you able to move on?

10. The bullying you experienced at work, do you feel it affected or changed anything in your life outside of work? Please tell me about that.

11. Has this impacted your personal life (can you explain)?

12. Downstream Factors

a. How do you cope with getting bullied?

b. Do you think getting bullied affects your ability to provide safe patient care?

c. Can you explain?

d. Has getting bullying affected your health?

Examples include: (anxiety, depression, psychological and physiological changes)

Have you had to seek medical or psychological treatment?

13. Reporting

a. Did you report the bullying to anybody?

Do you feel comfortable reporting bullying incidence at work?

Did you notice any consequence to you reporting bullying?

References

- Workplace Bullying Institute (2010) Workplace bullying: Recognize and prevent it.

- Askew DA, Schluter PJ, Dick ML (2013) Workplace bullying—What’s it got to do with general practice? Aust Fam Physician. 42: 186-188. [crossref]

- Hutchinson M, Vickers M, Jackson D, Wilkes L (2006) Workplace bullying in nursing: towards a more critical organizational perspective. Nursing Inquiry 13: 118-126. [crossref]

- Grimes-Holsinger V (2018) Reduction of workplace discord through self-awareness and personal de-escalation skills [unpublished doctoral dissertation]. Quinnipiac University.

- Vessey JA, DeMarco RF, Gaffney DA, Budin WC (2009) Bullying of staff registered nurses in the workplace: a preliminary study for developing personal and organizational strategies for the transformation of hostile to healthy workplace environments. Journal of Professional Nursing 25: 299-306. [crossref]

- American Association of Colleges of Nursing. (2011). Nursing Fact Sheet.

- Hurley J, Hutchinson M, Bradbury J, Browne G (2016). Nexus between preventive policy inadequacies, workplace bullying, and mental health: Qualitative findings from the experiences of Australian public sector employees. International Journal of Mental Health Nursing 25: 12-18. [crossref]

- Kivimaki M, Virtanen M, Vartia M, Elovainio M, Vahtera J, et al. (2003) Workplace bullying and the risk of cardiovascular disease and depression. Occupational and Environmental Medicine 60: 779-783.

- Kline R, Lewis D (2018) The price of fear: Estimating the financial cost of bullying and harassment to the NHS in England. Public Money & Management 39: 166-174.

- Asfaw AG, Chang CC, Ray TK (2014) Workplace mistreatment and sickness absenteeism from work: results from the 2010 National Health Interview survey. American Journal of Industrial Medicine 57: 202-213.

- LaVeist TA, Gaskin DJ, Richard P (2009) The economic burden of health inequalities in the United States. Washington, D.C.: Joint Center for Political and Economic Studies.

- Colosi B (2019) National health care retention and R.N. staffing Report.

- Allan HT, Cowie H, Smith P (2009) Overseas nurses’ experiences of discrimination: a case of racist bullying? Journal of Nursing Management 17: 898-906. [crossref]

- Chipps E, Stelmaschuk S, Albert NM, Bernhard L, Holloman C (2013) Workplace bullying in the OR: Results of a descriptive study. Association of Perioperative Nurses Journal 98: 479-493. [crossref]

- Shannon CA, Rospenda KM, Richman JA, Minich LM (2009) Race, racial discrimination, and the risk of work-related illness, injury, or assault: findings from a national study. Journal of Occupational and Environmental Medicine 51: 441-448. [crossref]

- Lindsey AP, Avery DR, Dawson JF, King EB (2017) Investigating why and for whom management ethnic representativeness influences interpersonal mistreatment in the workplace. Journal of Applied Psychology, 102: 1545-1563.

- Wang ML, Hsieh YH (2015) Do gender differences matter to workplace bullying? Work 53: 631-638. [crossref]

- Tajfel H, Turner JC (1986) The Social Identity Theory of Intergroup Behavior. In: S. Worchel and W. G. Austin, (Eds.), Psychology of Intergroup Relations, Hall Publishers, Chicago, pg: 7-24.

- Tajfel H, Turner JC (2004) The Social Identity Theory of Intergroup Behavior. Key readings in social psychology. In: Jost JT, Sidanius J (Eds,), Political psychology: Key readings, Key readings in social psychology, pg: 276-293. Psychology Press.

- Guba E, Lincoln Y (1994) Competing paradigms in qualitative research, In: Denzin N , Lincoln Y (Eds), Handbook of qualitative research. Pg: 105-117. Sage.

- Charmaz K, Thornberg R, Keane E (2018) Evolving grounded theory and social justice inquiry. In: NK Denzin, YS Lincoln (Eds.), The SAGE Handbook of Qualitative Research pg: 411-443 Sage.

- Breckenridge J, Jones D (2009) The grounded theory reviews. An International Journal 8: 1-71. http://www.groundedtheoryreview.com/wp-content/uploads/2012/06/ GT-Review-Vol8-no2.pdf#page=64.

- Strandmark KM, Rahm G, Wilde LB, Nordstrom G, Rystedt I (2017) Preventive Strategies and Processes to Counteract Bullying in Health Care Settings: Focus Group Discussions. Issues Mental Health Nursing 38: 113-121. [crossref]

- Malecki C, Demaray M (2003) What type of support do they need? Investigating Student Adjustment as related to emotional, Informational, Appraisal, and Instrumental Support. School Psychology Quarterly, 18: 231-252.

- Khattak MN, Khan MB, Fatima T, & Shah SZA (2019) The underlying mechanism between perceived organizational injustice and deviant workplace behaviors: Moderating role of personality traits. Asia Pacific Management Review 24: 201-211.

- Greer LL, Van Bunderen L, Yu S (2017) The dysfunctions of power in teams: A review and emergent conflict perspective. Research in Organizational Behavior 37: 103-124.

- Spence Laschinger HK, Fida R (2014) New nurses burnout and workplace well-being: The influence of authentic leadership and psychological capital. Elsevier 1: 19-28.

- Brewer LC, Cooper LA (2014) Race, Discrimination, and Cardiovascular Disease. Virtual Mentor 16: 455-460.

- Schilgen B, Nienhaus A, Handtke O, Schulz H, Mösko M (2017) Health situation of migrant and minority nurses: A systematic review. PloS one [crossref]

- Came H (2012) Institutional racism and the dynamics of privilege in public health, Thesis, Doctor of Philosophy (Ph.D.). University of Waikato, Hamilton, New Zealand.

- Mohammadpour A, Anumba C, Bulbul T, Messner J (2012) Facility management, industrial facilities, occupational safety, health care facilities, safety, decision making, information management. American Society of Civil Engineers Construction Research Congress 2012, Conference Information, May 21-23, 2012 | West Lafayette, Indiana, United States.

- Pallesen S, Nielsen MB, Magerøy N, Andreassen CS, et al. (2017) An Experimental Study on the Attribution of Personality Traits to Bullies and Targets in a Workplace Setting. Frontiers in psychology 8. [crossref]

- Mistry M, Latoo J (2009) Bullying: A growing workplace menace. British Journal of Medical Practitioners 3: 23-26.

- Rosa MW (2000) Some thoughts about resilience versus positive development, main effects versus interactions, and the value of resilience. Child Development 71: 567-569. [crossref]

- Oshio A, Taku K, Hirano M, Saeed G (2018) Resilience and big five personality traits: A meta-analysis. Personality, and Individual Differences 127: 54-60.

- Crenshaw K (1989) “Demarginalizing the Intersection of Race and Sex: A Black Feminist Critique of Antidiscrimination Doctrine, Feminist Theory and Antiracist Politics,” University of Chicago Legal Forum: Vol. 1989, Article 8.

- Woodrow C, Guest DE (2017) Leadership and approaches to the management of workplace bullying. European Journal of Work and Organizational Psychology 26: 221-233.

- Squires D, Anderson C (2015) U.S. health care from a global perspective: spending, use of services, prices, and health in 13 countries. Issue Brief (Common Fund). 15: 1-15. [crossref]

- Institute for Healthcare Improvement (2017) The triple aim or the quadruple aim? Four points to help set your strategy.

- Lewis N (2014) A primer on defining the triple aim. Institute for Healthcare Improvement.

- Bodenheimer T, Sinsky C (2014) From triple to quadruple aim: Care of the patient requires care of the provider. The Annals of Family Medicine 12: 573-576. [crossref]

- Johnson SL (2015) Workplace bullying prevention: a critical discourse analysis. Journal of Advanced Nursing 71: 2384-2392. [crossref]

- Rodwell J, Demir D, Steane P (2013) Psychological and organizational impact of bullying over and above negative affectivity: A survey of two nursing contexts. International Journal of Nursing Practice 19: 241-248. [crossref]

- Wilson BL, Diedrich A (2011) Bullies at work: The impact of horizontal hostility in the hospital setting and intent to leave. Journal of Nursing Administration 41: 453-458. [crossref]

- Chipps EM, McRury M (2012) The development of an educational intervention to address workplace bullying: a pilot study. Journal Nurses Staff Development 28: 94-8 [crossref]