Abstract

Background: Ultrasonography (USG) has become part of everyday care of pregnant women in most of the countries of the globe. However like any other technology, it has potential to raise social, ethical, economic dilemmas about benefits, challenges for health providers, beneficiaries of the services. Awareness, utilization of USG by rural tribal women who live in extreme poverty with access problems is not well known.

Objective: Community based study was carried out to know awareness of USG amongst rural, tribal, preconception, pregnant women and use of USG during pregnancy.

Material Methods: Study was conducted in tribal communities of 100 villages where community based mother child care services were initiated after having developed a health facility in one of 100 villages. Total 2400 preconception, 1040 pregnant women of 15-45 years, were interviewed in villages for knowing their awareness about USG, whether pregnant women had USG during pregnancy.

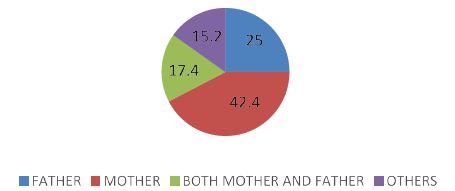

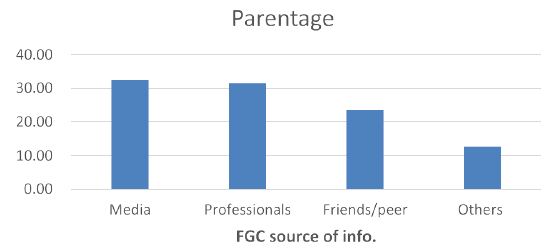

Results: Of 2400 preconception women, 626 (26.08%) were not aware of Sonography. Of those who knew, 694 (39.1%) said Sonography helped in confirmation of pregnancy, 1080 (60.88%) said it helped in knowing fetal age and position. Of 1040 pregnant women also 271 (26.1%) were not aware of USG. Those who knew, sources of information, were Accredited Social Health Activists (ASHAs) in 208 (27%), nurse midwives in 170 (22.1%), family members in 311 (40.4%), doctors in 80 (10.4%). Only 258 (33.5%) of 769 women who knew about USG had got USG done. Of them 82 (31.8%) were told that something was wrong without any details.

Conclusion: Study revealed that many rural tribal women did not even know about USG. Community health workers, ASHAs did create awareness of USG in some. Only 25% pregnant women had USG done but without knowing any details of findings.

Keywords

Preconception, Pregnancy, Awareness, Ultrasonography Finding

Background

Ultrasonography is now a integrated part of pregnancy care in most of the countries around the world. Diagnostic ultrasound during pregnancy may be employed for variety of reasons to see image of the baby, placenta and amonite fluid even for the woman and her family to see in addition to sonologist. Actually some clinicians are replacing clinical examination of pregnant women by USG, may be for confirmation of pregnancy, duration of pregnancy, number of foetuses, fetal growth and development, abnormalities of fetus, placenta and liquor by direct visualization, amniocentesis and/or cordocentesis. It can be used for foetal therapy too and even foetal foeticide and also for prediction of maternal disorders which affect mother as well as the baby [1]. However if abnormalities are detected during pregnancy it might lead to stress for the woman and the family, sometimes problems may be detected in women who do not have any risk factors, creating a lot of stress which has sequlae. Unfortunately there is likelihood of false alarm too specially when USG is performed by a person who lacks desired skill and knowledge or lack of time or desired attitude too. Assumptions are made that routine USG will prove beneficial by enabling earlier detection and improved management of pregnancy complications [2]. Routine screening may be done in early or late pregnancy, or both. Use of USG early in pregnancy is increasing, but there is limited information about linkage decision-making and impact on expectant women/couples. It is essential to know because globally there has been increasing medicalization of pregnancy [3]. However the awareness and utilization of USG by rural tribal women especially those with extreme poverty are not well known.

Material and Methods

After approval of ethics committee, which works on the principle of Helsinki Declaration, the study was conducted in tribal communities of 100 villages of rural, hilly and forestry, Melghat of Amravati, Maharashtra, India. In these villages community based mother and child care services were initiated after having created a health facility in one of the villages. Information was collected visiting every 5th house randomly, minimum 20 preconception women from each village total 2400 and 1040 pregnant women of 15-45 years. Interviews were conducted taking consent using a pretested tool in the language understood by women. Some questions needed yes or no answers and others short open answers.

Results

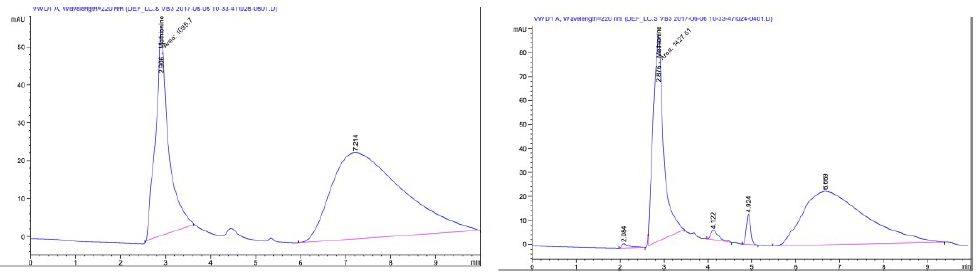

Of total 2400 preconception study subjects, 27% did not know anything and 1774 (73.9%) women were aware about sonography. Overall 694 (39.1%) of those who were aware said sonography helped in knowing about pregnancy, 1080 (60.88%) of those who knew about USG said it helped to know the fetal age and position. Overall 336 (14%) of 2400 women were of 15-19 years age, 271 (80.65%) of them were aware of sonography during pregnancy and 245 (90.41%) of them said USG helped in knowing fetal age with position and only 26 (9.59%) said it can confirm pregnancy. Of 74 women of 40-45 years age, 59 (79.3) were aware of USG similar to young women and 50 (84.75%) of them said it helped in knowing fetal age and position and only 9 (15.25%) said for confirmation of pregnancy. Of 953 (39.70%) of 2400 women were illiterate, 726 (76.18%) of them were aware of sonography and 539 (74.24%) said it helped to know fetal age and position and 187 (25.76%) said it confirmed pregnancy. Of 60 (65.93%) of 91 women with higher secondary education, 54 (90%) said USG helped in knowing fetal age and position and only 6 (10%) said confirmation pregnancy. Of 275 housewives 211 (76.72%) were aware of USG, 182 (86.26%) women said sonography helped in estimation of fetal age and position and 29 (13.74%) said for confirmation of pregnancy. Of 958 labourer 681 (71.86%), knew about sonography and 444 (65.2%) of those who knew about USG, said it helped to know the fetal age and position and 237 (34.8%) for confirmation pregnancy. Of 2400 preconception women, 662 (27.58%) belonged to upper lower economic class, [economic status was divided in five], 553 (83.53%) of them were aware of sonography, 340 (61.48%) said it helped in knowing fetal age and position and 213 (38.52%) confirmation of pregnancy. Seventy-four (50.34%) of 147 women who belonged to upper economic class, knew about sonography, significantly less (P Value 0.0127) and 39 (52.7%) said it helped in confirmation of pregnancy and 35 (47.3%) said to know about fetal age and position. Overall 85 (81%) of 105 who had no child were aware of sonography, 75 (88.24%) said it helped in estimation of fetal age, position and only 10 (11.8%) said confirmation pregnancy. Overall 421 (82.7%) of 509 who had five or more births were aware of sonography, similar to those with no child, 250 (59.4%) said it helped in confirmation of pregnancy and 171 (40.62%) estimation of fetal age and position. Total 626 (26.08%) 2400 preconception women did not know that there was something like sonography (Tables 1-3).

Table 1: Awareness of Ultrasonography in Preconception Women.

|

Variables |

Total |

Awareness |

|||

|

Age |

|||||

| No | % | Yes |

% |

||

| 15 to 19 |

336 |

65 | 19.35 | 271 |

80.65 |

| 20 to 24 |

828 |

181 | 21.86 | 647 |

78.14 |

| 25 to 29 |

736 |

243 | 33.02 | 493 |

66.98 |

| 30 to 34 |

333 |

75 | 22.52 | 258 |

77.48 |

| 35 to 39 |

93 |

47 | 50.54 | 46 |

49.46 |

| TOTAL |

74 |

15 | 20.27 | 59 |

79.73 |

|

Education |

2400 |

626 | 26.08 | 1774 |

73.92 |

| Illiterate | |||||

| Primary |

953 |

227 | 23.8 | 726 |

76.18 |

| Secondary |

850 |

282 | 33.2 | 568 |

66.82 |

| Higher secondary |

506 |

86 | 17.0 | 420 |

83 |

| Graduate |

91 |

31 | 34.1 | 60 |

65.93 |

| Post graduate |

0 |

0 | 0.0 | 0 |

0 |

| Total |

2400 |

626 | 26.08 | 1774 |

73.92 |

| Economic status | |||||

| Upper |

275 |

64 | 23.27 | 211 |

76.73 |

| Upper middle |

958 |

277 | 28.91 | 681 |

71.09 |

| Upper lower |

468 |

121 | 25.85 | 347 |

74.15 |

| Lower middle |

699 |

154 | 22.03 | 545 |

77.97 |

| Lower |

2400 |

626 | 26.08 | 1774 |

73.92 |

| Total | |||||

| Profession |

147 |

73 | 49.66 | 74 |

50.34 |

| Housewife |

183 |

59 | 32.24 | 124 |

67.76 |

| Own farm labour |

544 |

170 | 31.25 | 374 |

68.75 |

| Labourer |

662 |

109 | 16.47 | 553 |

83.53 |

| Other work |

864 |

215 | 24.88 | 649 |

75.12 |

| Total |

2400 |

626 | 26.08 | 1774 |

73.92 |

| Parity | |||||

| P. 0 |

105 |

20 | 19.05 | 85 |

81 |

| P. 1 |

411 |

131 | 31.87 | 280 |

68.1 |

| P. 2 |

672 |

218 | 32.44 | 454 |

67.6 |

| P. 3 |

453 |

123 | 27.15 | 330 |

72.8 |

| P. 4 |

250 |

46 | 18.4 | 204 |

81.6 |

| P. 5 Above |

509 |

88 | 17.29 | 421 |

82.7 |

| Total |

2400 |

626 | 26.08 | 1774 |

73.9 |

Table 2: Awareness of Ultrasonography Pregnant Women and Source of Information.

|

Variables |

Total | Awareness |

Source of information |

||||||||||

| Age |

NO |

% | YES | % | ASHA | % | ANM | % | Doctor | % | Family Member |

% |

|

| 15 to 19 |

323 |

107 | 33.1 | 216 | 66.9 | 129 | 59.7 | 49 | 22.7 | 21 | 9.7 | 17 |

7.9 |

| 20 to 24 |

536 |

130 | 24.3 | 406 | 75.7 | 166 | 40.9 | 152 | 37.4 | 66 | 16.3 | 22 |

5.4 |

| 25 to 29 |

109 |

22 | 20.2 | 87 | 79.8 | 19 | 21.8 | 41 | 47.1 | 3 | 3.4 | 24 |

27.6 |

| 30 to 34 |

68 |

12 | 17.6 | 56 | 82.4 | 21 | 37.5 | 19 | 33.9 | 4 | 7.1 | 12 |

21.4 |

| 35 to 39 |

4 |

0 | 0.0 | 4 | 100.0 | 1 | 25.0 | 0 | 0.0 | 0 | 0.0 | 3 | 75.0 |

|

TOTAL |

1040 | 271 | 26.1 | 769 | 73.9 | 336 | 43.7 | 261 | 33.9 | 94 | 12.2 | 78 |

10.1 |

| Education | |||||||||||||

| Illiterate |

56 |

19 | 33.9 | 37 | 66.1 | 21 | 56.8 | 13 | 35.1 | 3 | 8.1 | 0 | 0.0 |

|

Primary |

321 | 42 | 13.1 | 279 | 86.9 | 134 | 48.0 | 97 | 34.8 | 33 | 11.8 | 15 |

5.4 |

| Secondary |

358 |

58 | 16.2 | 300 | 83.8 | 102 | 34.0 | 186 | 62.0 | 6 | 2.0 | 6 | 2.0 |

|

Higher secondary |

196 | 58 | 29.6 | 138 | 70.4 | 41 | 29.7 | 29 | 21.0 | 13 | 9.4 | 55 |

39.9 |

| Graduate |

66 |

54 | 81.8 | 12 | 18.2 | 2 | 16.7 | 3 | 25.0 | 2 | 16.7 | 5 | 41.7 |

| Post graduate |

43 |

40 | 93.0 | 3 | 6.97 | 1 | 33.3 | 0 | 0.0 | 0 | 0.0 | 2 | 66.7 |

|

Total |

1040 | 271 | 26.1 | 769 | 73.9 | 301 | 39.1 | 328 | 42.7 | 57 | 7.4 | 83 |

10.8 |

| Economic status | |||||||||||||

| Upper |

43 |

42 | 97.7 | 1 | 2.3 | 1 | 100.0 | 0 | 0.0 | 0 | 0.0 | 0 | 0.0 |

|

Upper middle |

51 | 49 | 96.1 | 2 | 3.9 | 2 | 100.0 | 0 | 0.0 | 0 | 0.0 | 0 |

0.0 |

| Upper lower |

142 |

42 | 29.6 | 100 | 70.4 | 56 | 56.0 | 20 | 20.0 | 11 | 11.0 | 13 | 13.0 |

|

Lower middle |

186 | 61 | 32.8 | 125 | 67.2 | 67 | 53.6 | 30 | 24.0 | 12 | 9.6 | 16 |

12.8 |

| Lower |

618 |

77 | 12.5 | 541 | 87.5 | 294 | 54.3 | 166 | 30.7 | 52 | 9.6 | 29 | 5.4 |

|

Total |

1040 | 271 | 26.1 | 769 | 73.9 | 420 | 54.6 | 216 | 28.1 | 75 | 9.8 | 58 |

7.5 |

| Profession | |||||||||||||

| Housewife |

943 |

227 | 24.1 | 716 | 75.9 | 322 | 45.0 | 109 | 15.2 | 103 | 14.4 | 182 | 25.4 |

|

Own farm labour |

53 | 24 | 45.3 | 29 | 54.7 | 19 | 65.5 | 6 | 20.7 | 1 | 3.4 | 3 |

10.3 |

| Labourer |

40 |

19 | 47.5 | 21 | 52.5 | 17 | 81.0 | 2 | 9.5 | 0 | 0.0 | 2 | 9.5 |

|

Other work |

4 | 1 | 25.0 | 3 | 75.0 | 2 | 66.7 | 1 | 33.3 | 0 | 0.0 | 0 |

0.0 |

| Total |

1040 |

271 | 26.1 | 769 | 73.9 | 360 | 46.8 | 118 | 15.3 | 104 | 13.5 | 187 |

24.3 |

| Parity | |||||||||||||

| P.1 |

117 |

6 | 5.1 | 111 | 94.9 | 11 | 9.9 | 52 | 46.8 | 21 | 18.9 | 27 |

24.3 |

| P.2 |

103 |

4 | 3.9 | 99 | 96.1 | 66 | 66.7 | 21 | 21.2 | 8 | 8.1 | 4 |

4.0 |

| P.3 |

155 |

6 | 3.9 | 149 | 96.1 | 41 | 27.5 | 64 | 43.0 | 11 | 7.4 | 33 | 22.1 |

|

P.4 |

204 | 15 | 7.4 | 189 | 92.6 | 49 | 25.9 | 21 | 11.1 | 29 | 15.3 | 90 |

47.6 |

| P.5 Above |

461 |

240 | 52.1 | 221 | 47.9 | 41 | 18.6 | 12 | 5.4 | 11 | 5.0 | 157 | 71.0 |

| Total |

1040 |

271 | 26.1 | 769 | 73.9 | 208 | 27.0 | 170 | 22.1 | 80 | 10.4 | 311 |

40.4 |

ASHA: Accredited Social Health Activist.

ANM: Auxiliary nurse midwife.

Table 3: Ultrasonography during Pregnancy by Rural Tribal Women.

|

Variables |

Total | Ultrasound done |

If YES Abnormality Informed |

||||||

| Age |

NO |

% | YES | % | Yes | % | No |

% |

|

| 15 to 19 |

323 |

220 | 68.1 | 103 | 31.9 | 25 | 24.3 | 78 | 75.7 |

|

20 to 24 |

536 | 413 | 77.1 | 123 | 22.9 | 42 | 34.1 | 81 |

65.9 |

| 25 to 29 |

109 |

91 | 83.5 | 18 | 16.5 | 7 | 38.9 | 11 | 61.1 |

|

30 to 34 |

68 | 57 | 83.8 | 11 | 16.2 | 6 | 54.5 | 5 |

45.5 |

| 35 to 39 |

4 |

1 | 25.0 | 3 | 75.0 | 2 | 66.7 | 1 | 33.3 |

|

Total |

1040 | 782 | 75.2 | 258 | 24.8 | 82 | 31.8 | 176 |

68.2 |

| Education | |||||||||

| Illiterate |

56 |

40 | 71.4 | 16 | 28.6 | 4 | 25.0 | 12 | 75.0 |

|

Primary |

321 | 282 | 87.9 | 39 | 12.1 | 19 | 48.7 | 20 |

51.3 |

| Secondary |

358 |

307 | 85.8 | 51 | 14.2 | 15 | 29.4 | 36 | 70.6 |

|

Higher secondary |

196 | 136 | 69.4 | 60 | 30.6 | 16 | 26.7 | 44 |

73.3 |

| Graduate |

66 |

11 | 16.7 | 55 | 83.3 | 14 | 25.5 | 41 | 74.5 |

|

Post graduate |

43 | 6 | 14.0 | 37 | 86.0 | 14 | 37.8 | 23 |

62.2 |

| Total |

1040 |

782 | 75.2 | 258 | 24.8 | 82 | 31.8 | 176 |

68.2 |

| Economic status | |||||||||

| Upper |

43 |

1 | 2.3 | 42 | 97.7 | 11 | 26.2 | 31 | 73.8 |

|

Upper middle |

51 | 10 | 19.6 | 41 | 80.4 | 6 | 14.6 | 35 |

85.4 |

| Upper lower |

142 |

82 | 57.7 | 60 | 42.3 | 12 | 20.0 | 48 | 80.0 |

|

Lower middle |

186 | 130 | 69.9 | 56 | 30.1 | 27 | 48.2 | 29 |

51.8 |

| Lower |

618 |

559 | 90.5 | 59 | 9.5 | 26 | 44.1 | 33 | 55.9 |

|

Total |

1040 | 782 | 75.2 | 258 | 24.8 | 82 | 31.8 | 176 |

68.2 |

| Profession | |||||||||

| Housewife |

943 |

718 | 76.1 | 225 | 23.9 | 66 | 29.3 | 159 | 70.7 |

|

Own farm labour |

53 | 34 | 64.2 | 19 | 35.8 | 16 | 84.2 | 3 |

15.8 |

| Labourer |

40 |

29 | 72.5 | 11 | 27.5 | 0 | 0.0 | 11 | 100 |

|

Other work |

4 | 1 | 25.0 | 3 | 75.0 | 0 | 0.0 | 3 |

100 |

| Total |

1040 |

782 | 75.2 | 258 | 24.8 | 82 | 31.8 | 176 |

68.2 |

| Parity | |||||||||

| P.1 |

117 |

88 | 75.2 | 29 | 24.8 | 7 | 24.1 | 22 | 75.9 |

|

P.2 |

103 | 62 | 60.2 | 41 | 39.8 | 11 | 26.8 | 30 |

73.2 |

| P.3 |

155 |

87 | 56.1 | 68 | 43.9 | 24 | 35.3 | 44 | 64.7 |

|

P.4 |

204 | 135 | 66.2 | 69 | 33.8 | 22 | 31.9 | 47 |

68.1 |

| P.5 Above |

461 |

410 | 88.9 | 51 | 11.1 | 18 | 35.3 | 33 | 64.7 |

|

Total |

1040 | 782 | 75.2 | 258 | 24.8 | 82 | 31.8 | 176 |

68.2 |

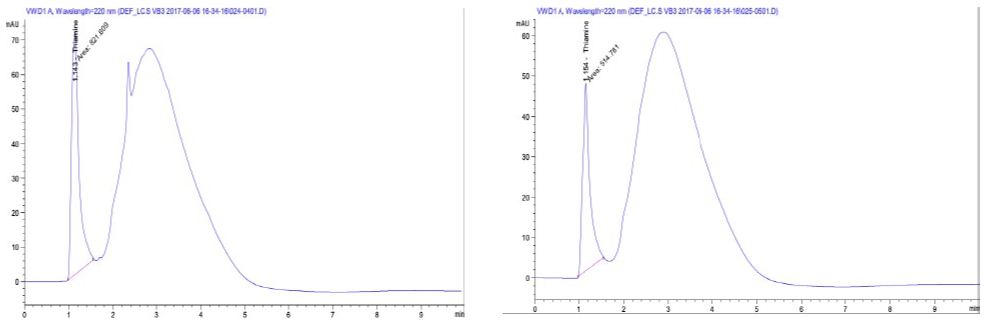

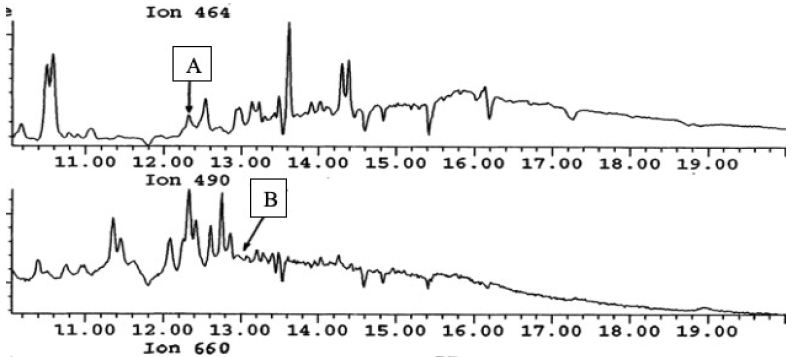

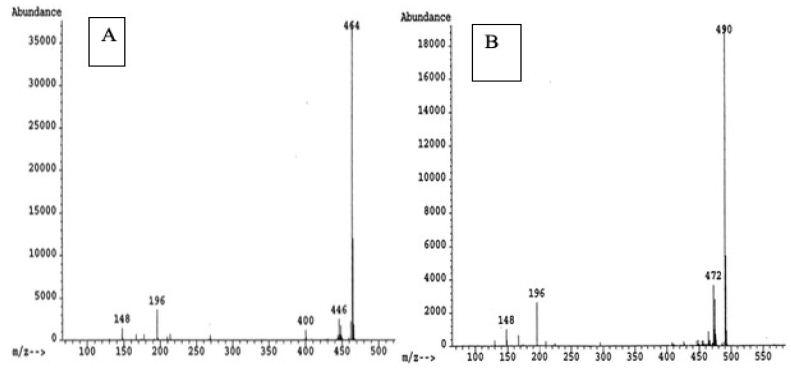

Total 769 (73.9%) of 1040 rural tribal pregnant women, knew about USG in pregnant women but 271 (26.1%) did not know. The sources of information were Accredited Social Health activists (ASHA) 208 (27%), nurse midwives 170 (22.1%), family members 311 (40.4%) and in 80 (10.4%) doctors. Of 1040 study subjects, 406 (75.7%) of 536 of 20-24 years were aware of USG, Sources of information were ASHAs in 166 (40.9%), Nurse Midwives in 152 (34.4%), 66 (16.3%) Doctors and 22 (5.4%) family members. As age increased more women were found to be knowing about USG, 216 (66.9%) of 323 of 15 to 19 year, 60 (83.33%) of 72 of 30-39 years old. (P Value 0.3776) It seemed to be related to increased parity too. Out of 1040 pregnant women, 43 (4.13%) were postgraduate studied still only 3 (6.97%) were aware, one (33.3%) was toldby ASHA and 2 (66.7%) by family members. Overall 56 (5.38%) illiterate women, 34 (66.1%) were aware of USG, by ASHAs 21 (56.8%), Nurse midwives 13 (35.1%) and Doctors 3 (8.1%). Only 2 (3.9%) of 51who belonged to middle economic class were aware of USG, ASHAs, being the source of information in both. Of 1040 pregnant women, 618 belonged to lower economic class and 541 (87.5%) of them were aware of USG, ASHAs were the source in 294 (54.3%), nurse midwives in 166 (30.7%), doctors in 52 (9.6%) and family members in 29 (5.4%). Among 1040 pregnant women, 943 were housewives and of them 716 (75.9%) were aware of USG. ASHAs were the source in 322 (45.0%) and family members in 182 (25.4%). Overall 21 (52.5%) of 40 labourers were aware of USG and 17 (81%) were told by ASHAs.

As the parity increased number of women with awareness increased, 27 (24.3%) of 111 primigravida and 157 (71%) of 221 fifth gravida said they were told by family members. Only 258 (24.8%) of 1040 pregnant women themselves had USG and 782 (75.2%) did not. 258 (33.5%) of 769 women who knew about USG had USG done. Of them 82 (31.8%) were told of possibilities of some abnormalities but they did not know any details. There seemed to be no communication in most of the cases in whom USGs was done, probably because USG were done in camps at Primary Health Centers or Sub District Hospital with crowds around. Of 1040 study subjects, 536 (51.53%) were of 20-24 year, 123 (22.9%) got USG done, 42 (34.1%) said some abnormalities were told but did not know any details. 14 (19.44%) of 72 of 30-39 year had USG, of which 8 (57.14%) were told of abnormalities without details. Of 66 graduates, 55 (83.3%) had USG and 29 (52.7%) were told of some abnormalities. Only 16 (28.6%) of 56 illiterate had USG and 4 (25%) were told of some abnormalities. Of 43 (4.13%) who belonged to middle economic class, 41 (80.4%) had USG and 9 (22%) of them were told of some abnormalities. Only 59 (9.5%) of 618 women who belonged to lower economic class had USG. Twenty (33.9%) said some abnormalities were told without any details. Of 943 (90.67%) of 1040 pregnant housewives, 225 (23.9%) had USG and 66 (29.3%) were told about abnormalities, but they did not know any details. Only 11 (27.5%) of 40 labourers had USG and no one said they were told of any abnormalities. Total 117 (11.25%) were primipara, only 29 (24.8%) of them had USG and 7 (24.1%) said some abnormalities were told without any details. Overall 188 (29.74%) of 632 women who had 3 or more births in 64 (34.04%) were told of some abnormalities with no details.

Discussion

In the present day clinical practice the discussion is on evidence-based guidelines disseminated to physicians, obstetrician, nurses and sonologists for antenatal ultrasound scans with advocacy of guidance about the appropriate use of ultrasound scans to be shared with women in order to discourage unreasonable expectations, demands and apprehensions. On one side USG is done many times during pregnancy by urban women for various reasons, many rural women do not even know about USG, do not even think of diagnostic antenatal checkup. Bashour et al. reported that private doctors, who looked after 80% of pregnant women, offered ultrasound primarily to attract women to their clinics and increase their income [4]. Kozuki et al. reported that the utilization of obstetric USG in rural women of Nepal was very limited. Researchers reported that more research was necessary to assess the potential of health impact of obstetric USG in low-resource settings, while addressing limitations such as cost and misuse [5]. Cherniak et al. reported that women could be motivated to attend antenatal clinics when offered the incentive of seeing their baby through USG [6]. Huang et al. reported high use of antenatal ultrasound in rural Eastern China, influenced by socio-demographic and clinical factors [7]. Torloni et al. reported that USG in pregnancy was not associated with adverse maternal effects, impaired physical or neurological development or increased risk to children [8]. However with over diagnosis some stress is always likely. With under diagnosis there are many problems and it is essential that there is awareness and understanding of use and misuse.

Whitworth et al. also reported that early USG helped in the detection of multiple pregnancies with improved gestational dating which resulted in fewer inductions for post maturity [2]. This can only happen if women know and can use the technology. It does not seem to be happening for rural women. Abramowicz et al. reported that USG carried some risks of misdiagnosis on the one hand and possible undesired effects on the other [9]. The general belief existed that diagnostic USG did not pose any risk, neither to the pregnant women nor to the fetus. But risk-benefit analysis may also be important, as well as education of the end users to assure safety. Fact remains false diagnosis might give mental stress even dilemmas when not knowing anything as happened in the present study. USG were done during camps at PHCs and Sub-District Hospital (SDH) and women did not know details of abnormalities. Phutke et al. reported it is essential to re-examine and update the use of diagnostic, USG widely available even the most peripheral health facilities [10]. Studies showed that pregnant women generally value routine ultrasounds in the first two trimesters because they get reassurance and chances to see their unborn baby.

Although growing, evidence on the impact, access, utility, effectiveness, and cost-benefit of obstetric ultrasound in resource-constrained settings is still somewhat limited, questions around the purpose and the intended benefits as well as potential challenges across various domains must be carefully reviewed prior to implementation and scale-up of obstetric USG in Low-and Middle-Income Countries (LMICs). Whitworth et al. reported that some (but not all) benefits described in the literature have been validated by evidence-based analysis [2]. Unlike other modes for prenatal screening and diagnosis, USG offers parents direct access to images of the fetus. This makes obstetric ultrasound popular and attractive among expectant mothers so they want to use it often [11,12]. Women see prenatal USG as means for reassurance about the health and well-being of their fetuses. However, sometimes USG may yield unexpected findings which may have adverse effects on the mental health of mother and may provoke emotional crisis [13,14]. Significant psychological harm from antenatal ultrasound as well as positive psychological effects have been reported [15]. Counselling is needed to further enhance the USG experience and to reduce anxiety and dispel any misconceptions and irrational expectations regarding the antenatal USG. In the present study quite a few preconception as well as pregnant women did not know anything about USG. Those pregnant women who knew also did not get USG done during pregnancy due to various reasons. Those who had USG did not know details of abnormalities as any discussion or communication took place.

Of 2400 preconception study subjects, 1774 (73.9%) women were aware about sonography, 694 (39.1%) said sonography helped knowing about pregnancy, 1080 (60.88%) of those who knew said it helped in knowing fetal age and position. Overall 1774 of 2400 preconception women, 626 (26.08%) were not aware of USG, of 953 (39.70%) illiterate, 726 (76.18%) were aware of sonography, 539 (74.24%) said sonography helped to know fetal age and position and 187 (25.76%) said for confirmation pregnancy. So it was word of mouth which more often made women aware.

Of 1040 pregnant women, 271 (26.1%) were not even aware about USG during pregnancy, women with more than one birth too did not know. Most women got information from ASHAs 208 (27.0%), 170 (22.1%) NM of Sub center. Of 1040 study subjects, 258 of 769 (33.5%) of those who knew had USG, 82 (10.7%) of them were told about some abnormalities, but without any details. Rest did not know anything about what was found. Communication and counseling are essential.

Halle et al. reported that USG in the first half of pregnancy were in high use in Iceland and apparently became part of a broader pregnancy culture, encompassing both high- and low-risk pregnancies [16]. Whether this is a favourable development or to some extent represents unwarranted medicalization needs further discussion. More balanced information might be provided prior to early screening for foetal anomalies. In rural community women start care by mid pregnancy.

Yadav et al. reported that in their study 72.41% pregnant women felt USG was done for knowing fetal anomalies and 27.93% for sex detection, majority (93.1%) had USG more (43.45 %) in second trimester mainly on advice of doctors (91.03%) [17]. Nearly half of them (50.69%) considered it as expensive procedure and 50.69%% of them opined it should be done twice in pregnancy. Almost 94.83% considered USG as safe and beneficial. Awareness regarding the uses of USG during pregnancy and attitude towards USG was neither negative possible. Westerneng et al. reported that pregnant women seemed to appreciate a third trimester routine ultrasound, but it did not seem to reduce anxiety or improve bonding with their baby [18]. Women’s appreciation of a third trimester routine ultrasound might arise from getting used to routine ultrasounds throughout pregnancy. Results of such findings should be taken into consideration when balancing the gains, which are as yet not clear, of introducing a third trimester routine ultrasound against unwanted side effects and costs.

Ikeako et al. did a study and reported that the number of respondents who had USG in their previous pregnancies was 58.7% [19]. Although many reasons were given for personal USG requests, 19.7% women who had obstetric scan in their previous pregnancies thought it was a normal booking test done for every pregnant woman. When compared with other booking investigations, 60.1%, mainly civil servants said that USG in pregnancy was costly, 24.4% felt it was cheap, 9.1% said it was very costly and remaining 2.4% thought it was not affordable. Apart from visualizing the images of their babies, 17.8% of the cases wanted to know the gender and 15.4% said it was for knowing of fetal position.

Total 52.9% were of the opinion that women could decide when to request for sonography. Majority of Nigerian women requested ultrasound for looking at fetus and gender determination. Gururaj et al. reported that care providers and government officials perceived ultrasound diagnosis as critical to deciding whether to refer women who might need high-risk support from higher-level centres that are often geographically remote [20]. Findings suggested a strong need to re-evaluate the evidence base for routine obstetric ultrasound in rural LMIC settings and include more stakeholders in participatory, co-design approaches to innovation. Firtha et al. opined that ultrasound would increase Antenatal Care (ANC) attendance [21]. Kim et al. opined that as cost of obstetric ultrasound became more affordable in LMICs, it is essential to assess the benefits, trade-offs and potential drawbacks of large-scale implementation [22]. Additionally, there was a need to more clearly identify the capabilities and the limitations of ultrasound, particularly in the context of limited training of providers, to ensure that the purpose, for which an ultrasound was intended, was actually feasible. Researchers also reported that there was evidence that ultrasound was not associated with reducing maternal, perinatal or neonatal mortality, also reported various studies revealed both positive and negative perceptions and experiences related to ultrasound and lastly, illegal use of ultrasound for determining fetal sex raised a concern. Saleh et al. reported that most of the participants were aware of ultrasound scan and also believed that the procedure was safe, and the main purpose was for fetal wellbeing and viability [23].

Ugwu et al. did a study and reported that 73% women got their information from antenatal centres. Over 20% were interested in the lies and presentation of their foetus [24].

Conclusion

The role of prenatal sonography in obstetric care should be real with preconception awareness in antenatal centres, and initiating mother/sonographers interaction is necessary.

References

- Ville YG, Bault JP (2016) Prenatal Diagnoses of Fetal Malformations by Ultrasound. Genetic Disorders and the Fetus 5: 121-126.

- Whitworth M, Bricker L, Mullan C (2015) Ultrasound for fetal assessment in early pregnancy. Cochrane database of systematic reviews. [crossref]

- Miller S, Abalos E, Chamillard M, Ciapponi A, Colaci D, et al. (2016) Beyond too little, too late and too much, too soon: a pathway towards evidence-based, respectful maternity care worldwide. The Lancet 388: 2176-2192.

- Bashour H, Hafez R, Abdulsalam A (2005) Syrian women’s perceptions and experiences of ultrasound screening in pregnancy: implications for antenatal policy. Reproductive Health Matters 13: 147-154. [crossref]

- Kozuki N, Katz J, Khatry SK, Tielsch JM, LeClerq SC, et al. (2016) Community survey on awareness and use of obstetric ultrasonography in rural Sarlahi District, Nepal. International Journal of Gynecology & Obstetrics 134: 126-130. [crossref]

- Cherniak W, Anguyo G, Meaney C, Kong LY, Malhame I, et al. (2017) Effectiveness of advertising availability of prenatal ultrasound on uptake of antenatal care in rural Uganda: A cluster randomized trial. Plos One 12. [crossref]

- Huang K, Tao F, Raven J, Liu L, Wu X, et al. (2012) Utilization of antenatal ultrasound scan and implications for caesarean section: a cross-sectional study in rural Eastern China. BMC Health Services Research 12: 93.

- Torloni MR, Vedmedovska N, Merialdi M, Betràn AP, Allen T, et al. (2008) OC196: Safety of ultrasonography in pregnancy: WHO systematic review of the literature and meta‐analysis. Ultrasound in Obstetrics and Gynecology 32: 307-.

- Abramowicz S, Susarla HK, Kim S, Kaban LB (2013) Physical findings associated with active temporomandibular joint inflammation in children with juvenile idiopathic arthritis. Journal of Oral and Maxillofacial Surgery 71: 1683-1687. [crossref]

- Phutke GA, Laux T, Jain P, Jain YO (2018) Ultrasound in rural India: A failure of the best intentions. Indian J Med Ethics 18: 1-7. [crossref]

- Bricker L, Gacia J, Henderson J, Mugford M, Neilson J, et al. (2000) Ultrasound screening in pregnancy: a systematic review of the clinical effectiveness, costeffectiveness and women’s views. Health Technol Assess 4: 1-193. [crossref]

- Georgsson Ohman S, Waldenstrom U (2008) Second-trimester routine ultrasound screening: expectations and experiences in a nationwide Swedish sample. Ultrasound Obstet Gyneco 32: 15-22.

- Gammeltoft T, Thi H, Nguyen T (2007) The Commodification of Obstetric Ultrasound Scanning in Hanoi, Viet Nam. Reprod Health Matters 15: 163-171. [crossref]

- Sommerseth E, Sundby J (2010) Women’s experiences when ultrasound examinations give unexpected findings in the second trimester. Women and Birth 23: 111-116. [crossref]

- Harris G, Connor L, Bisits A, Higginbotham N (2008) “Seeing the Baby”: Pleasures and Dilemmas of Ultrasound Technologies for Primiparous Australian Women. Med Anthropol Q 18: 23-47. [crossref]

- Halle KF, Fjose M, Kristjansdottir H, Bjornsdottir A, Getz L, et al. (2018) Use of pregnancy ultrasound before the 19th week scan: an analytical study based on the Icelandic Childbirth and Health Cohort. BMC Pregnancy and Childbirth 1; 18: 512.

- Yadav JU, Yadav DJ (2017) Ultrasonography awareness among pregnant women attending medical college hospital in Kolhapur District of Maharashtra, India. International Journal of Research in Medical Sciences 5: 2612.

- Westerneng M, Diepeveen M, Witteveen AB, Westerman MJ, Van Der Horst HE, et al. (2016) Experiences of pregnant women with a third trimester routine ultrasound-a qualitative study. BMC Pregnancy and Childbirth 19: 1-0.

- Ikeako LC, Ezegwui HU, Onwudiwe E, Enwereji JO (2014) Attitude of expectant mothers on the use of ultrasound in pregnancy in a tertiary institution in South East of Nigeria. Annals of Medical and Health Sciences Research 4: 949-953. [crossref]

- Gururaj A (2017) Exploring the role of a semi-automated ultrasound technology in rural Indian antenatal care (Doctoral dissertation, University of Oxford).

- Firtha ER, Mlay P, Walker R, Sill PR (2011) Pregnant women’s beliefs, expectations and experiences of antenatal ultrasound in Northern Tanzania. African Journal of Reproductive Health 15: 91-107. [crossref]

- Kim ET, Singh K, Moran A, Armbruster D, Kozuki N (2018) Obstetric ultrasound use in low and middle income countries: a narrative review. Reproductive Health 15: 129.

- Saleh AA, Idris G, Dare A, Yahuza MA, Suwaid MA, et al. (2017) Awareness and perception of pregnant women about obstetrics ultrasound at Aminu Kano Teaching Hospital. Sahel Medical Journal 20: 38.

- Ugwu AC, Udoh BE, Eze JC, Eze PC (2011) Awareness of information, expectations and experiences among women for obstetric sonography in a south east Nigeria population. East African Journal of Public Health 8: 142-144. [crossref]