DOI: 10.31038/ASMHS.2019353

Abstract

The objective of this study was to understand how ordinary people react to information about conferences. The study is part of the Mind Genomics exploration of the world of the everyday. Respondents evaluated systematically created vignettes about conferences, with the elements of the vignettes presenting information about the topic of the conference, the way the material is presented to excite emotions, the way the facts are presented, and the after-conference activities, respectively. The study introduced the assessment of interactions between ideas in a vignette (scenario analysis). The results suggest three clearly different mind-sets; those who focus on the topic, those who focus on the nature of the presenter, and those who focus on the after-conference activities. These three mind-sets distribute similarly in the population. The study presents a PVI, personal viewpoint identifier, allowing a conference planner to understand the mind-set to which members of the prospective audience may belong, which knowledge may produce a more impactful conference.

Introduction

One need only look at the proliferation of non-governmental organization intent on solving key issues in the world to get a sense of an increasing social awareness. Beyond the world of the organization is the world of the meeting, where experts and others in the field come together, under one or another aegis or directorate, to discuss the problems, to formulate solutions, or simply to meet. The meetings are in the thousands, often by invitation, and limited, presumably to those attendees whose interest is established in the topic. Every organization attempts to validate its meaning, its raison d’etre, either by publications which communicate important information to the world, by publications of an academic nature which dissect the problem, or more typically in today’s world, by a ‘meeting.’ The meeting, formally titled ‘conference’ , assembles those who are involved in the topic. The conference may turn into a standard, periodic meeting, or become a one-off attempt to ‘solve a problem’ or at least to discuss how various experts would approach the problem. One needs only look at the announcements of such meetings to get a sense of how popular it is for people to get together for short, concentrated periods of time, be available to the public as the public face of those concerned, come up with recommendations, and then scatter back to their regular jobs. Our focus in this paper is to understand how the average person reacts to these types of conferences. To be sure, the topic of ‘meeting’ is not one of high interest to people, unless they are somehow involved. Despite the special nature of conferences, the notion of conferences is by now well known, especially due to the high-profile nature of conferences dealing with important issues. The emerging science of Mind Genomics, the study of the everyday, provides a perfect tool to understand how ordinary people respond to descriptions of these ‘meetings.’ We are not taking the pulse of people towards meetings in general, the points of satisfaction and dissatisfaction, but rather trying to understand the mind of the typical person confronted with special topic, issue-related conferences.

The world of public conferences

The topics of conferences vary dramatically. Most conferences are of minor importance, dealing with specific issues and relevant to a limited number of people, the organizers and the attendees. On the other hand, there are major conferences, often sponsored by world organizations such as the United Nations or by NGO’s (non-government organizations.) The participation of NGO’s continues to interest researchers [1–4], perhaps because the NGO’s are involved with high-profile topics. Conferences are also venues for professionals to meet, and especially for graduate students to introduce themselves to their colleagues, and present papers about their work [5,6] For the seasoned professional, conferences are a venue for promoting one’s work, and for developing a support system [7,8]. For the undergraduate student, an often-overlooked ground of nascent professionals, conferences can provide a launching pad to create a life-long professional [9] The focus of published research literature dealing with conferences is the topic itself, and secondarily a venue in which people interact [10]. In spirit the literature is sociology, the interact of people, and not psychology, the individual’s needs, wants, feelings, and behavior. There is some literature on the desires of conference attendees in terms of they want [11,12], and even papers dealing with people’s behaviors in conferences, such as tweeting [13]. The result of such investigations reveals the nature of people’s participation, and even prescriptions about creating good conferences [14]. They do not tell us about the inner feelings of people towards a conference as a part of their daily life.

This paper moves from the conferences as a topic of sociology, looking from the outside, to a topic of psychology, looking at the conference from the inside, focusing on the reactions of a respondent presented with vignettes, small descriptions, about conferences. Each description comprises different features of the conference; topic, speaker, nature of information, follow up activities. The objective of the Mind Genomics effort in general, and this study in particular, is to create the science of the everyday, using one’s knowledge of quotidian events like conferences, to understand the way people think about and make decisions about the ordinary events of their lives.

The Mind Genomics approach

When confronted with everyday situations, especially those which do not require much thinking, and where there is no real ‘risk,’ the typical person acts automatically, what Nobel Laureate Daniel Kahneman calls involving the System 1 mode of thought. System 1 is the emotion-driven, automatic system upon which virtually people rely most of the time. System 1rapidly processes the information, incorporates emotions, and drives a response, often on what seems to be ‘auto-pilot.’ Such a system is necessary to navigate a life in which many choices are required to be made each few minutes, ranging from where to move when walking, to how to eat a meal, and so forth [15]. The automatic responses and behaviors need to be limited to the very ordinary. For example, people who attend the meetings often form opinions in what seems to be an automatic fashion, talking freely about the different aspects of the meeting without much rehearsal. That is, people respond to the meetings, can dissect the different aspects of the meetings with great ease after the fact, and in the case of boring meetings, during the meeting as people talk with each other while ignoring the presenter. The set of tools to investigate the aspects of the everyday are housed in Mind Genomics. Mind Genomics is the emerging science of the everyday, created to look at the nature of the different patterns of reactions that people exhibit to descriptions of situations [16–18]. The intellectual history of Mind Genomics emerges from mathematical psychology [19], and the adaptation to market research with consumers [20, 21]. When applied to social issues such as meetings sponsored by NGO’s, Mind Genomics reveals what is important about the meeting versus what is unimportant, or how the presenter affects the credibility of the information being presented.

Raw materials

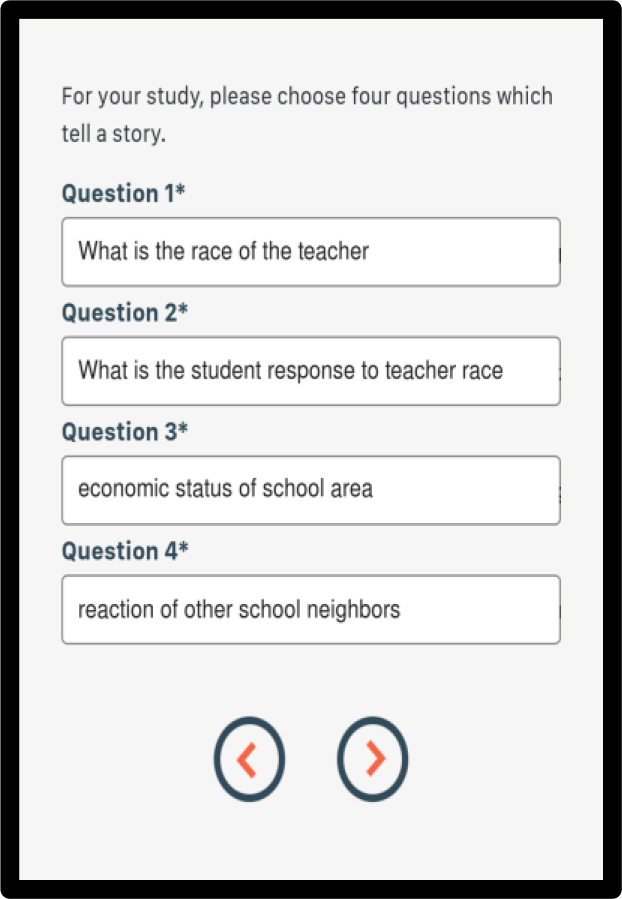

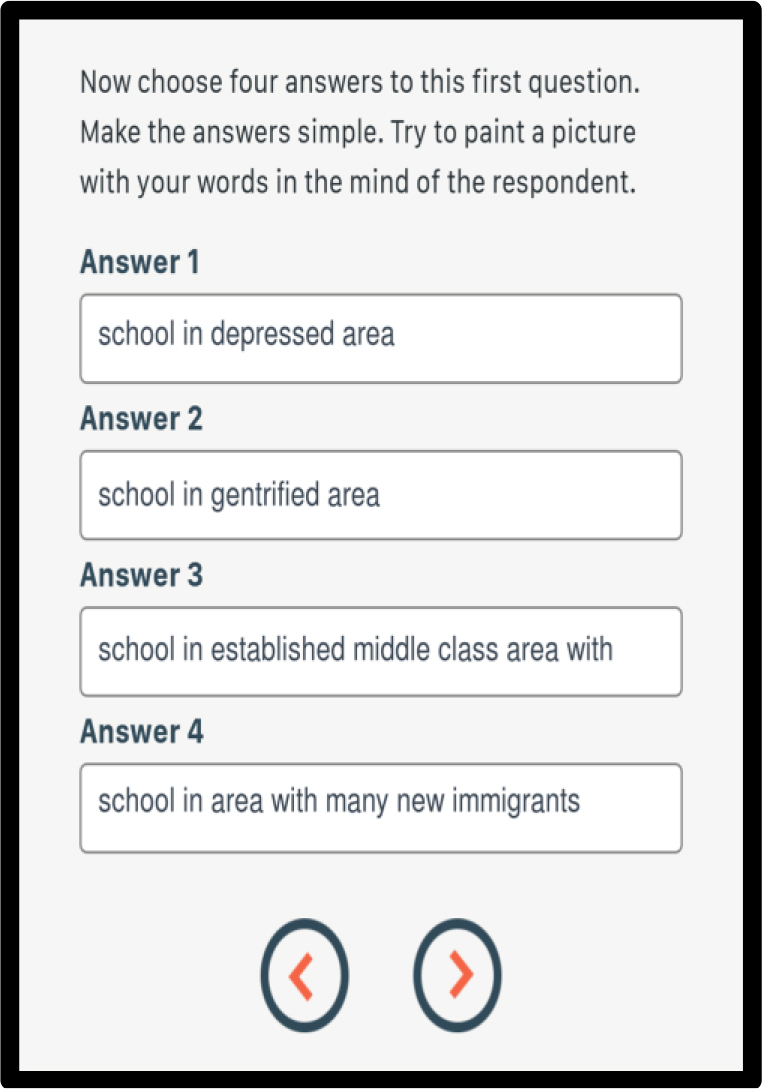

The input to Mind Genomics comprises a set of questions, and alternative answers to each question. Table 1 presents the four questions and the set of 16 answers. Typically, these questions ‘tell a story’, with the different answers providing the necessary material to ‘flesh out’ the story. The questions never appear in the actual experiment with respondents. Rather, the questions are used to elicit the answers, which will appear in combination.

Table 1 presents the information in a way which enables the respondent to ‘graze the vignette,’ and extract the relevant ideas. Each answer is prefaced by an introductory phrase, such as ‘conference topic,’ ‘presenter,’ ‘expert’ and ‘follow-up’ respectively. Although this format does not lead to grammatically elegant vignettes, the format makes it easy to present the respondent with the information necessary to make a decision. In studies using experimentally designed combinations of ideas, with individuals exposed to many combinations, it is becoming increasingly vital to shorten the interview. The time for elegantly written but dense paragraphs has passed, as researchers are forced to do increasingly shorter interviews and experiments. The design of the individual elements in this study (Table 1), and the design of the vignettes are done with the recognition that the entire Mind Genomics experiment should last no more than five minutes.

Table 1. The questions and answers about conferences.

|

|

Question A: What is the nature of the conference?

|

|

A1

|

conference topic: problems in world environment

|

|

A2

|

conference topic: problems teaching students to think critically

|

|

A3

|

conference topic: loss of respect and empathy of people towards each other

|

|

A4

|

conference topic: government actions and quality of life

|

|

|

Question B: How are the problems presented to excite emotions?

|

|

B1

|

presenter: talks about personal experiences and suffering

|

|

B2

|

presenter: video presentation narrated

|

|

B3

|

presenter: well-known social activist

|

|

B4

|

presenter: critical NGO (non-governmental organization)

|

|

|

Question C: How do experts present the facts?

|

|

C1

|

expert: well-known university professor with to-do list

|

|

C2

|

expert: well-known author on topic

|

|

C3

|

expert: panel of business people

|

|

C4

|

expert: high government official in topic area

|

|

|

Question D: How does the conference ensure its real value with post conference activities?

|

|

D1

|

follow-up: create workshops to teach how to solve

|

|

D2

|

follow-up: create workshops in schools

|

|

D3

|

follow-up: a stronger awareness thru media

|

|

D4

|

follow-up: create free groups to give meaning and motivation

|

The answers are combined according to an underlying experimental design, a prescription of what answers or ‘elements’ should be combined [22] The experimental design prescribes a set of 24 combinations for the array of four questions and four answers for each question. The underlying experimental design ensures that all 16 answers are statistically independent, permitting the analysis by OLS (ordinary least-squares) regression. The underlying experimental design ensures that some of the test combinations, called ‘vignettes’, are incomplete, lacking either one or two answers. This deliberate creation of incomplete vignettes is done so that the coefficients from the OLS regression have ‘absolute value,’ allowing them to be compared from study to study, even when the studies comprise other types of messages.

Each respondent evaluated a totally unique set of combinations of vignettes, created according to the same underlying experimental design, but ‘permuted’. This strategy enables the researcher to assess many different combinations of answers or elements [23] it is important to emphasize that this strategy of testing many different vignettes, with 1–2 evaluations of each vignette, means that we look for patterns by looking at the entire space of alternatives, rather than looking for patterns by canceling out the variability. Most research looks for patterns by suppressing the noise through replication. Mind Genomics does the exact opposite, discovering the pattern by looking at a lot of the space, even if the individual measures are ‘noisy.’

The rating 5-pooint rating scale combining understanding and action

Traditionally, Mind Genomics has worked with bipolar Likert scales, anchored at the top and at the bottom. The scales usually have focused on one dimension, whether that be ‘do not understand versus understand’ (what is), or ‘not motivated to do something versus motivated to do something’ (intended action.). When the two topics of ‘what is’ versus’ intended are investigated in the same study, they often have been separate questions, answered quickly in succession. The Mind Genomics experiment presented here represents the next generation, in which a single rating question is created to encompass two dimensions.

For this study, the five rating points appear below:

Here are conferences dealing with major problems. How do you feel about this specific conference as described? Choose one of the following five answers

1=tuned out immediately. ..waste of time

2=don’t understand facts & not motivated to solve problem

3=understand facts but not motivated to solve problem

4=don’t understand facts but motivated to solve problem

5=understand facts & motivated to solve problem

Analyzing the results at a surface level

The easiest way to understand the data, and to compare groups looks at averages. We create the following key dependent variables, and then compare them by group:

- Response time

- Rating 1 converted to binary (tuned out)

- Rating 5 converted to binary (understand facts & motivated to solve problems),

- Ratings 3&5 converted to binary, a so-called ‘netted variable’ that we call UNDERSTAND.

- Ratings 4&5 converted to binary, another ‘netted variable’ that we call MOTIVATED TO SOLVE PROBLEMS

Table 2 shows the average value for each of these five variables, for total panel, and key subgroups (gender, age, self-defined focus on the topic of these conferences, and finally two groups of mind-sets emerging from dividing the 50 respondents into complementary groups, based upon the pattern how motivated they are to solve problems

Table 2. Average ratings for response time (seconds), and binary variables, based upon the analysis of subgroups.

|

|

|

RT

SECONDS

|

R1

TUNED OUT

|

R5

YES UNDERTAND YES MOTIVATED

|

NET YES UNDERSTAND

|

NET YES

MOTIVATED

|

|

1

|

Total

|

5.1

|

14

|

23

|

51

|

48

|

|

2

|

Female

|

5.4

|

13

|

24

|

49

|

51

|

|

3

|

Male

|

4.7

|

16

|

23

|

54

|

45

|

|

4

|

Age 50+

|

7.0

|

25

|

23

|

49

|

42

|

|

5

|

Age 30–49

|

4.3

|

6

|

27

|

56

|

54

|

|

6

|

Age 15–29

|

2.7

|

12

|

16

|

45

|

47

|

|

7

|

Q3 Interested

|

5.0

|

6

|

28

|

56

|

57

|

|

8

|

Q3 Skeptic

|

5.9

|

32

|

15

|

43

|

30

|

|

9

|

Q3 Passionate

|

3.9

|

9

|

21

|

52

|

51

|

|

10

|

Q3 Turned off

|

5.7

|

46

|

5

|

26

|

19

|

|

11

|

Q3 Not applicable

|

5.5

|

22

|

22

|

53

|

31

|

|

12

|

Mind-Set 2A

|

4.0

|

14

|

27

|

51

|

54

|

|

13

|

Mind-Set 2B

|

6.1

|

15

|

19

|

51

|

42

|

|

14

|

Mind-Set 3C

|

4.1

|

13

|

20

|

46

|

53

|

|

15

|

Mind-Set 3D

|

5.9

|

12

|

18

|

51

|

45

|

|

16

|

Mind-Set 3E

|

5.3

|

19

|

32

|

57

|

45

|

The important lesson from Table 2 is that there are differences which manifest themselves in the response time, and in the pattern of ratings. We see the expected differences between the respondents who say that they are ‘tuned out’ versus those say they are passionate. Furthermore, some age differences emerge, few gender differences emerge, and so forth.

Table 2 lacks the cognitive dimension of the results. We see behaviors, but the averages have only meaning in a numerical way, telling us an external measure, a measure that we attempt to use as we search for an underlying pattern. The pattern lies within the mind of the researcher, not in the data. There is no cognitive richness in the data presented by Table 2, but only patterns, the meaning of which must be imposed on the data, and with any luck, will be perceived as appropriate for the data, not as imposed on the data.

Finally, in (Table 2) there is the story, but the story is general, not specific, not rich, and certain does not tell us of the inner workings of the mind of the respondent.

Linking messages to judgments

We undertook this Mind Genomic study to understand how people react to the different aspects of these NGO-sponsored conferences. We focused on five different responses that people might have, including absolutely no interest (Rating 1, R1), do not understand and not motivated to solve the problem (Rating 2, R2), understand but not motivated to solve the problem (Rating 3), do not understand but motivated to solve the problem (Rating 4, R4), and finally understand and motivated to solve the problem (Rating3, R3) or motivated to solve the problem (Rating5, R5). We also presented two net key variables; understand (Rating3 + Rating4, R3+R4), and motivated to solve the problem (Rating4 + Rating5, R4+R5).

The underlying experimental design enables us to relate the presence/absence of the 16 elements to either one of the responses (1–5), or any subset of the responses (e.g., those of men versus those of women). The approach used is known generically as regression analysis, occasionally referred to as ‘curve fitting.’ The objective is to deconstruct the dependent variable to the contribution of the 16 contributing elements the answers provided the four questions. The cases or observations for the regression analysis comprise the full set of 1200 vignettes, wherein one knows both the composition of the vignette, e.g., which of the answers were present,’ and the reaction, e.g., which rating or net rating was selected, and thus converted to 100. All rating variables will be presented after transformation to the binary values 0 (not chosen) or 100 (chosen) when the respondent evaluated the vignette. (Table 3) shows us the coefficients for six dependent variables; R1, R5, Net Not Understand, Net Not Motivated, Net Understand, Net Motivated. The model begins with the additive constant. The additive constant is the estimated value of the dependent variable when there are not elements or answers in the vignette, a hypothetical situation since all vignettes comprised at least two elements, and at most four elements. Nonetheless, the additive constant is a useful number, behaving as a baseline. When we look at the coefficients, we should keep in mind that the underlying statistics of the regression enable us to estimate the likelihood that the coefficient that we observe is not just a random occurrence from an underlying distribution of coefficients with a real average or mean of 0. That critical value is 8 or higher, or -8 and lower. Knowledge of that range (beyond +/- 8) helps us focus on those answers or elements which drive a strong positive or negative response. These strong performers are shown as number in bold font, and in shaded cells. Visual inspection suggests possible patterns in this otherwise daunting ‘wall of numbers.’

Table 3. Links between elements (answers, messages) in the vignettes and six dependent variables. The strong linkages are shown in bold font, and shaded cells.

|

|

Total

|

R1 TUNED OUT

|

R5 YES UND YE & SMOT

|

NET NOT UNDERSTAND

|

NET NOT MOTIVATED

|

NET UNDERSTAND

|

NET MOTIVATED

|

|

|

CONSTANT

|

24

|

20

|

26

|

40

|

50

|

36

|

|

A1

|

conference topic: problems in world environment

|

-2

|

-2

|

5

|

-4

|

-2

|

6

|

|

A2

|

conference topic: problems teaching students to think critically

|

-7

|

6

|

0

|

-3

|

8

|

11

|

|

A3

|

conference topic: loss of respect and empathy of people towards each other

|

-3

|

10

|

-3

|

-9

|

6

|

12

|

|

A4

|

conference topic: government actions and quality of life

|

-5

|

4

|

3

|

-4

|

2

|

9

|

|

B1

|

presenter: talks about personal experiences and suffering

|

-3

|

3

|

6

|

-6

|

-3

|

8

|

|

B2

|

presenter: video presentation narrated

|

0

|

2

|

4

|

-7

|

-4

|

7

|

|

B3

|

presenter: well-known social activist

|

-5

|

3

|

6

|

-3

|

-1

|

8

|

|

B4

|

presenter: critical NGO (non-governmental organization)

|

-1

|

2

|

9

|

-6

|

-8

|

8

|

|

C1

|

expert: well-known university professor with to-do list

|

-4

|

-2

|

6

|

7

|

-2

|

-3

|

|

C2

|

expert: well-known author on topic

|

-3

|

1

|

0

|

8

|

3

|

-5

|

|

C3

|

expert: panel of business people

|

1

|

-3

|

3

|

4

|

-4

|

-5

|

|

C4

|

expert: high government official in topic area

|

-3

|

-4

|

-1

|

7

|

4

|

-4

|

|

D1

|

follow-up: create workshops to teach how to solve

|

-6

|

2

|

3

|

1

|

3

|

5

|

|

D2

|

follow-up: create workshops in schools

|

-1

|

0

|

-1

|

-2

|

1

|

3

|

|

D3

|

follow-up: a stronger awareness thru media

|

0

|

-7

|

3

|

6

|

-3

|

-6

|

|

D4

|

follow-up: create free groups to give meaning and motivation

|

-3

|

2

|

-2

|

-1

|

5

|

4

|

We look now in a rapid fashion at the six response variables:

R1 – Tuned out: This response has a low additive constant, 24, meaning that in the absence of elements in the vignette, approximately one quarter of the responses will be ‘tuned out;’ There are no key drivers of ‘tuning out’, at least with the total panel.

R5 – Understand and motivated to make a change: This variable has the lowest additive constant, 20, meaning that in the absence of elements in the vignette, approximately one fifth of the responses will be this positive. It is the job of the elements, the answers, to drive understanding and motivation. Only one element is sufficiently powerful to drive this response, A3, conference topic: loss of respect and empathy of people towards each other. The strong response to A3 emerges because of the strong ‘pull’ of this idea.

Net Not Understand: This variable is constructed from the two response variables which feature ‘Do Not Understand’. They are rating choices R2 and R4. When either is selected, the newly constructed variable, Net Not Understand, is given the value of 100. When neither is selected, Net Not Understand is given the value of 0. Ironically, the only group which promotes a possible misunderstanding is the presenter being from a critical NGO (non-governmental organization.) This suggest that the role of NGO is not perceived as very instructive, at least by the average American respondent.

NET NOT MOTIVATED (to solve problems): This variable takes on the value 100 when the respondent chooses R2 or R3, both involving no motivation to solve problems. Otherwise, this variable takes on the value 0. The key destroyer of motivation to these respondents is the presenter being the well-known author on the topic. It is as if having the well-known author is a symbolic fulfillment of what has to be done. Metaphorically, the author is the ‘priest’ who atones for the congregation. An analogy may be made to modern corporations which send their employees to conferences on innovation, have walls of awards and certificates in their lobbies, but are prisoners to outdated processes, and believe that despite innovation, ‘process is king.’ As long as the employees listen to experts, the corporation may be said to fulfill its role to embrace innovation.

NET UNDERSTAND: This variable is constructed from R3 and R5. Both responses talk about understanding the facts. The additive constant is high. The key element driving this response is the conference dealing with teaching students to think critically. The respondents believe that they will understand the issues involved.

NET MOTIVATED: This variable is constructed from R4 and R5. Both responses talk about being motivated to change. The elements appear to connect with the human experience:

conference topic: loss of respect and empathy of people towards each other

conference topic: problems teaching students to think critically

conference topic: government actions and quality of life

presenter: talks about personal experiences and suffering

presenter: well-known social activist

presenter: critical NGO (non-governmental organization)

Does the topic of the conference affect how people judge the different vignettes?

The features or messages to which one responds are not independent of each other. That is, depending upon one part of the message, another part of the message may either make sense or not make sense. A good example is the price. For example, we can lay out prices for an object, and ask people to rate the degree to which the price is fair. Yet, none of the pricing data makes sense unless we know the object or service for which the price is designed. A $2.00 price for a loaf of bread is meaningful. A $2.00 price for an automobile makes no sense whatsoever.

The Mind Genomics system enables us to assess pairwise interactions answers from different questions (or elements from different silos.) This ability to address the issue of interactions emerges as a happy byproduct of the nature of the underlying experimental design, a structure which specifies the test combinations. The design remains the same for all respondents, but the actual combinations change from one respondent to another. The ensures a statistically robust set of combinations, with all the answers from one question appearing with all the answers in the other questions. In other words, the final set of combinations is sufficiently robust to allow us to pull out pairwise combinations.

The strategy to uncover pairwise interactions is straightforward both in computation and in meaning, respectively. We divide the set of 1200 vignettes into strata, based upon the answer in one question. In the analysis presented here we divide the 1200 vignettes into five strata, depending upon the specific question. We will focus on Question A, the topic of the conference. Our focus now is how the different elements or answers perform when the conference topic is held constant, focusing on problems in world environment, problems in teaching students to think critically, and so forth.

We first sort the data, creating five strata, depending upon the particular topic. We then run the OLS regression once again, this time running the data separately in each stratum. The OLS regression is run on 12 predictors, the four answers from Question B, the four answers from Question C, and the four answers from Question D. Thus, we have five parallel analyses, one for each topic, and one analysis where no topic is specified. Thus, the focus is not on the topics as separate, but the topics as guiding the performance of the remaining elements. This approach has been coined ‘scenario analysis’ [24]. The reason for the term ‘scenario’ is that the analysis operates with a specific type of meeting, the ‘scenario’ in which everything is judged.

What makes a respondent feel that he or she would tune-out, i.e., reject the conference

We begin our analysis of interactions by identifying those elements or answers which lead to the respondent ‘tuning out.’

- No topic (all vignettes lack the presence of A1-A4): These vignettes generate a fair amount of tune-out responses. The additive constant is 26, meaning that in the absolute of a topic, and just information about the presenter and the follow-up,, about one out of four responses will be ‘tuned out’ (R1). What really bores people, however, is a presenter with a video narration. The coefficient is +12, a really boring strategy.

- Problems in the world’s environment: This topic is also slightly boring, with an additive constant of 20. That 20 means that in the absence of answers or specific elements, just knowing that the conference is about problems in the world’s environment will generate about 20% responses of ‘tuned out.’ However, there are no elements which drive ‘tuned out.’ The elements themselves are interesting.

- Problems in teaching students to think critically: This topic of a conference is more interesting. The additive constant is 15, meaning only 15% of the responses are expected to be ‘tuned-out’ when the specific elements or messages are missing. Once again, we see that no elements or answers drive boredom and tune-out. The specifics are interesting.

- The loss of respect and empathy of people towards each other: This is also a fundamentally more interesting topic, with the additive constant of 14. There are three elements which drive the respondent feel that he or she would tune out, despite the fundamentally interesting nature of the topic:

follow-up: create workshops in schools

presenter: critical NGO (non-governmental organization)

presenter: well-known social activist

- Government actions and the quality of life: This is perhaps the most likely topic to drive the response of ‘tuned out.’ The additive constant is 25. Beyond that, however, we find no elements which are turn-offs.

- We conclude from this analysis that there are interactions between the topic of the conference and the elements which can be found boring. Some interactions are dramatic. A narrated video presentation might be a turn off by itself when there is no topic specified, and a turn-off when the topic is loss of respect and empathy of people towards each other (coefficients of +12 and +6, respectively), but will be not a turn off when the topic is government actions and the quality of life (Table 4).

Table 4. Scenario analysis. How the nature of the conference (top row) drives the response R1 (tuned out).

|

|

Dependent variable = R1

(TUNED OUT)

|

no topic

|

problems in world environment

|

problems teaching students to think critically

|

loss of respect and empathy of people towards each other

|

government actions and quality of life

|

|

|

Additive constant

|

26

|

20

|

15

|

14

|

25

|

|

B2

|

presenter: video presentation narrated

|

12

|

-3

|

-3

|

6

|

-9

|

|

C2

|

expert: well-known author on topic

|

1

|

-5

|

0

|

-16

|

-1

|

|

C3

|

expert: panel of business people

|

1

|

-1

|

1

|

-4

|

7

|

|

D2

|

follow-up: create workshops in schools

|

0

|

0

|

-10

|

12

|

-2

|

|

B4

|

presenter: critical NGO (non-governmental organization)

|

-2

|

-2

|

-4

|

8

|

-7

|

|

D1

|

follow-up: create workshops to teach how to solve

|

-5

|

-8

|

-5

|

1

|

-5

|

|

D3

|

follow-up: a stronger awareness thru media

|

-5

|

1

|

4

|

7

|

-4

|

|

D4

|

follow-up: create free groups to give meaning and motivation

|

-6

|

-9

|

-2

|

3

|

-5

|

|

C1

|

expert: well-known university professor with to-do list

|

-7

|

4

|

3

|

-12

|

-9

|

|

C4

|

expert: high government official in topic area

|

-7

|

2

|

4

|

-7

|

-8

|

|

B1

|

presenter: talks about personal experiences and suffering

|

-8

|

3

|

-3

|

1

|

0

|

|

B3

|

presenter: well-known social activist

|

-11

|

-3

|

-4

|

8

|

-12

|

Getting the message across – what drives the response of ‘I understand the facts’?

Our second analysis looks at the drivers of ‘I understand the facts), which comprises responses R3 and R5, together. When a respondent selected R3 or R5, this new ‘net variable’ of ‘understand’ was assigned the value 100. When a respondent selected R1, R2 or R4, respectively, this new net variable ‘understand’ was assigned the value 0. The analysis then proceeded as did the previous analysis, considering five strata, based upon the topic of the conference. (Table 5) shows the detailed results.

Table 5. Scenario analysis. How the nature of the conference (top row) drives the ‘net response’ of understand the facts (combined Rating3 and Rating5).

|

|

Understand the facts

(R3 and R5)

|

No topic

|

problems in world environment

|

problems teaching students to think critically

|

loss of respect and empathy of people towards each other

|

government actions and quality of life

|

|

|

Additive constant

|

45

|

67

|

54

|

47

|

52

|

|

D4

|

follow-up: create free groups to give meaning and motivation

|

21

|

-1

|

-2

|

1

|

9

|

|

C4

|

expert: high government official in topic area

|

17

|

-7

|

0

|

9

|

8

|

|

C3

|

expert: panel of business people

|

15

|

-1

|

-13

|

5

|

-15

|

|

D2

|

follow-up: create workshops in schools

|

14

|

-3

|

1

|

0

|

-3

|

|

C2

|

expert: well-known author on topic

|

8

|

4

|

10

|

8

|

-2

|

|

C1

|

expert: well-known university professor with to-do list

|

7

|

-8

|

-15

|

18

|

-4

|

|

D1

|

follow-up: create workshops to teach how to solve

|

7

|

-13

|

9

|

-5

|

9

|

|

D3

|

follow-up: a stronger awareness thru media

|

7

|

-13

|

2

|

-3

|

-5

|

|

B3

|

presenter: well-known social activist

|

-9

|

-5

|

-4

|

4

|

-1

|

|

B1

|

presenter: talks about personal experiences and suffering

|

-12

|

-29

|

8

|

-4

|

3

|

|

B4

|

presenter: critical NGO (non-governmental organization)

|

-24

|

-17

|

0

|

-5

|

-4

|

|

B2

|

presenter: video presentation narrated

|

-36

|

-12

|

10

|

4

|

3

|

- The additive constants suggest that even without elements or answers, at least half of the responses are going to encompass some understanding. The most likely understanding will come from conferences dealing with problems in the world’s environment. The least likely understand will come from conferences dealing with loss of respect and empathy of people towards each other.

- No topic specified – strongest contribution to understanding comes from creating free groups to give meaning and motivation. Follow up here is important.

- Problems in world environment – basic understanding is very high (additive constant = 67), but no elements or answers increase understanding.

- Problems teaching students to think critically’

expert: well-known author on topic

presenter: video presentation narrated

- Loss of respect and empathy of people towards each other – expert: well-known university professor with to-do list

- Government actions and quality of life –

Follow up: create free groups to give meaning and motivation

expert: high government official in topic area

What makes the respondent feel that she or is motivated to make changes?

Our third analysis looks at the net rating of ‘yes, motivated to make changes.’ This net variable comprises the selection of rating 4 (do not understand the facts, motivated to make changes) or the selection of rating 5 (understand the facts, motivated to make changes).

The actual analysis is identical. The only difference is the choice of the dependent variable. (Table 6) presents the detailed results regarding what motivates the reader to believe that she or he will take action.

Table 6: Scenario analysis. How the nature of the conference (top row) drives the ‘net response’ of motivated to make changes (combined Rating4 and Rating 5).

|

|

Motivated to make changes (R4 and R5)

|

No topic

|

problems in world environment

|

problems teaching students to think critically

|

loss of respect and empathy of people towards each other

|

government actions and quality of life

|

|

|

Additive constant

|

51

|

31

|

36

|

59

|

47

|

|

C4

|

expert: high government official in topic area

|

4

|

-2

|

-13

|

-8

|

1

|

|

D3

|

follow-up: a stronger awareness thru media

|

3

|

4

|

-15

|

-19

|

-2

|

|

B1

|

presenter: talks about personal experiences and suffering

|

1

|

13

|

0

|

16

|

9

|

|

B4

|

presenter: critical NGO (non-governmental organization)

|

0

|

16

|

12

|

-4

|

16

|

|

B3

|

presenter: well-known social activist

|

-1

|

11

|

22

|

-6

|

2

|

|

C1

|

expert: well-known university professor with to-do list

|

-1

|

-14

|

4

|

2

|

-6

|

|

D1

|

follow-up: create workshops to teach how to solve

|

-5

|

15

|

-2

|

1

|

9

|

|

D2

|

follow-up: create workshops in schools

|

-5

|

7

|

17

|

-12

|

-3

|

|

B2

|

presenter: video presentation narrated

|

-6

|

20

|

19

|

0

|

0

|

|

C3

|

expert: panel of business people

|

-7

|

-15

|

9

|

-2

|

-11

|

|

D4

|

follow-up: create free groups to give meaning and motivation

|

-8

|

22

|

9

|

-4

|

9

|

|

C2

|

expert: well-known author on topic

|

-18

|

-4

|

10

|

1

|

-11

|

When we look at the additive constants, showing the expected likelihood of people saying ‘I am motivated to make changes,’ we find that the highest motivation emerges with conferences on loss of respect and empathy of people towards each other (additive constant = 59.) The lowest likelihood emerges with conferences regarding problems in the world’s environment (additive constant = 31), and problems teaching students to thinking critically (additive constant = 36).

The elements or answers which drive the motivation tell their own stories. The operating elements which ‘work’ must have a topic of the conference

Problems in the world’s environment – best to have a video presentation and follow-up groups.

Problems teaching students to think critically – best to have a social activist presenting, or a narrated video presentation, and then follow-up groups

Loss of respect and empathy of people towards each other – best to have a person with experience talking about the experience

Government actions and quality of life – best to have an NGO presenter

Gender differences

Often, genders do not differ dramatically from each other, except in topics that are gender-relevant, such as cosmetics. The data from the total panel (Table 3) can be deconstructed into the responses by gender (Table 7). When we look at males versus females for the net response of ‘understand’ (ratings 3 and 5 combined), we see that women are more likely to say that they ‘understand the fact’s (additive constant 55 for women, 43 for men), and that they are also more ‘motivated’ (additive constant 41 for women, 28 for men). Thus, the first observation is that women will be more likely to say that they are affected by the conference.

Table 7. Comparison of male versus female in their ratings of ‘understand the facts’ and ‘motivated to make a change.’ The numbers in the body of the table are the coefficients from the ‘net’ models (understand = R3 & R5; motivated = R4 & R5).

|

|

|

Understand

|

Understand

|

|

Motivated

|

Motivated

|

|

|

|

M

|

F

|

|

M

|

F

|

|

|

Additive constant

|

43

|

55

|

|

28

|

41

|

|

A1

|

conference topic: problems in world environment

|

5

|

-8

|

|

8

|

5

|

|

A2

|

conference topic: problems teaching students to think critically

|

19

|

-3

|

|

5

|

17

|

|

A3

|

conference topic: loss of respect and empathy of people towards each other

|

12

|

0

|

|

3

|

21

|

|

A4

|

conference topic: government actions and quality of life

|

2

|

2

|

|

5

|

13

|

|

B1

|

presenter: talks about personal experiences and suffering

|

1

|

-6

|

|

7

|

9

|

|

B2

|

presenter: video presentation narrated

|

2

|

-9

|

|

3

|

11

|

|

B3

|

presenter: well-known social activist

|

0

|

0

|

|

10

|

6

|

|

B4

|

presenter: critical NGO (non-governmental organization)

|

3

|

-16

|

|

13

|

3

|

|

C1

|

expert: well-known university professor with to-do list

|

2

|

-6

|

|

-1

|

-4

|

|

C2

|

expert: well-known author on topic

|

0

|

7

|

|

1

|

-9

|

|

C3

|

expert: panel of business people

|

-6

|

-2

|

|

4

|

-12

|

|

C4

|

expert: high government official in topic area

|

-2

|

9

|

|

2

|

-9

|

|

D1

|

follow-up: create workshops to teach how to solve

|

2

|

4

|

|

8

|

2

|

|

D2

|

follow-up: create workshops in schools

|

9

|

-6

|

|

8

|

-2

|

|

D3

|

follow-up: a stronger awareness thru media

|

0

|

-5

|

|

-4

|

-8

|

|

D4

|

follow-up: create free groups to give meaning and motivation

|

3

|

7

|

|

6

|

3

|

The real gender differences emerge when we look at the answers or elements. In terms of helping the person to understand the facts, men strongly feel that the conference will help them to understand two topics, problems teaching students to think critically and loss of respect and empathy of people towards each other. It may be that these are the only topics that men feel they will learn something new.

When it comes to the topic of motivation, (Table 7) shows dramatic differences by gender. Men are convinced by presenters from NGO’s and by social activists. Men start at a lower level (additive constant = 28), feeling that it will be harder to motivate them, and in turn feel that NGO’s and social activists will be effective. Women, in contrast, are far more likely to say that they will be motivated (additive constant = 41). The truly dramatic topics, those which women think will motivate them those dealing with loss of respective and empathy (coefficient = 21), teaching students to think critically (coefficient = 17), and government actions and the quality of life (coefficient = 13).

In search of different mind-sets

It has become increasingly clear during the past decades that people differ dramatically in what they find interesting. This variation across people in liking is not a new discovery. The old adage holds increasingly today: Of taste one does not dispute. Each person has his or her own pattern of preferences, these preferences ranging from the sensory experience one enjoys (e.g., different flavors), but moving on to experiences themselves (ways of being treated; activities to do on vacations.)

The notion of differences across people is obvious. One important question is to develop a way to measure the pattern of preferences, which has been done by Mind Genomics, and just demonstrated for data from the total panel versus from males versus females. The next question is to determine whether there are fundamental groups of people, so that the patterns of preference are similar within a group, but the patterns of the groups differ dramatically from each other?

Discovering different groups, mind-sets, can be formulated in terms of a statistical problem answerable by the technique of clustering [25]. Each respondent in this study generated a set of 16 coefficients, one coefficient for each of the 16 phrases. The coefficients we choose are those emerging out of Ratings 4 and 5, motivated to change. Clustering divides the set of 50 respondents into mutually exclusive groups, with the property that the patterns within a group are similar to each other, whereas the patterns of the averages of the groups are very different from each other. These groups, statistically developed, are called Mind-Sets in the parlance of Mind Genomics.

The clustering procedures works with a measure of ‘distance’ between pairs of respondents. The distance is defined as the quantity (1-R), where R is the Pearson correlation coefficient. Thus, the distance measure looks at how well the two patterns correlate. When the patterns of coefficients from two respondents correlate perfectly, they are really reacting in the same way to the answers or elements. The Pearson correlation is 1.0, and the distance should be minimal, which it is. The distance is (1-R), i.e., (1–1), or 0. In contrast, when the two respondents react in opposite ways, they are maximally different from each other. The Pearson correlation is -1, and the distance is maximal (1 – – 1 = 2.)

The clustering procedure is agnostic, not concerned with the meaning of the clusters, focusing only on satisfying the mathematical criteria of maximal distance between the averages of the two clusters on the 16 answers, and minimal distance between pairs of respondents within a cluster. The clustering must be augmented by some researcher input, specifically:

Parsimony – fewer clusters or mind-sets are better than more, both from an aesthetic point of view in research, as well as from an actionability point of view when the data are put to use.

Interpretability – the cluster must ‘make sense,’ i.e., tell a story

The two clusters based upon ‘Motivated’ (R4 and R5; converted to binary) were not interpretable. Too many different ‘stories’ emerged. The three clusters which emerged based upon ‘Motivated’ tell a more coherent story, and so we settle on the three clusters

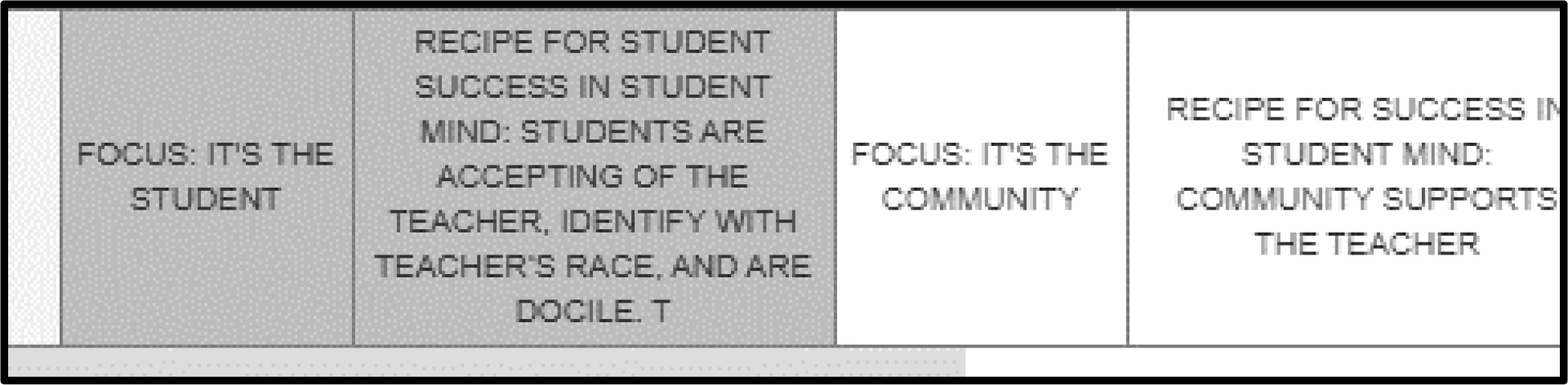

The three-cluster solution is remarkably simple to interpret, suggesting three different ways to motivate the audience. There are those who are motivated by the topic, those who are motivated by the presenter, and those who are motivated by the after-conference opportunities to share ideas (Table 8).

Table 8. Comparison of three emergent Mind-Sets based on clustering the coefficients from ‘Motivated’ (R4 & R5). The numbers in the body of the table are the coefficients from the ‘net’ models (motivated R4 & R5; understand the facts R3 & R5.

|

|

|

Motivate (R4 & R5 as binary)

|

|

Understand (R3 & R5 as binary)

|

|

|

|

MS1

|

MS2

|

MS3

|

|

MS1

|

MS2

|

MS3

|

|

|

Additive constant

|

26

|

50

|

26

|

|

30

|

46

|

77

|

|

|

Mind-Set 1 – Responds to the topic

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

A3

|

conference topic: loss of respect and empathy of people towards each other

|

29

|

5

|

7

|

|

15

|

9

|

-6

|

|

A4

|

conference topic: government actions and quality of life

|

25

|

9

|

-6

|

|

9

|

1

|

-3

|

|

A1

|

conference topic: problems in world environment

|

24

|

4

|

-6

|

|

-4

|

-2

|

0

|

|

A2

|

conference topic: problems teaching students to think critically

|

23

|

1

|

12

|

|

21

|

7

|

-4

|

|

D2

|

follow-up: create workshops in schools

|

16

|

-19

|

12

|

|

2

|

3

|

-4

|

|

|

Mind-set 2 – responds to the type of presenter

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

B3

|

presenter: well-known social activist

|

-1

|

18

|

7

|

|

1

|

-1

|

-3

|

|

B2

|

presenter: video presentation narrated

|

-1

|

17

|

2

|

|

5

|

-2

|

-15

|

|

B4

|

presenter: critical NGO ( non-governmental organization)

|

6

|

16

|

-1

|

|

-10

|

-2

|

-12

|

|

B1

|

presenter: talks about personal experiences and suffering

|

4

|

14

|

3

|

|

-4

|

0

|

-5

|

|

|

Mind-set 3 – Responds to activities created for the after-conference

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

D1

|

follow-up: create workshops to teach how to solve

|

6

|

-19

|

30

|

|

5

|

2

|

1

|

|

D4

|

follow-up: create free groups to give meaning and motivation

|

5

|

-11

|

24

|

|

12

|

4

|

-3

|

|

|

Does not appeal to any of the three Mind-sets generated from Motivation

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

C2

|

expert: well-known author on topic

|

-11

|

3

|

-2

|

|

20

|

-3

|

-8

|

|

C4

|

expert: high government official in topic area

|

-21

|

5

|

2

|

|

12

|

-1

|

1

|

|

C1

|

expert: well-known university professor with to-do list

|

-9

|

-2

|

2

|

|

10

|

-9

|

-5

|

|

C3

|

expert: panel of business people

|

-9

|

0

|

-3

|

|

6

|

-10

|

-11

|

|

D3

|

follow-up: a stronger awareness thru media

|

6

|

-25

|

6

|

|

1

|

5

|

-19

|

Finding mind-sets in the general population for better conference design and effective messaging

Mind Genomics as we have just demonstrated begins to provide a corpus of information about the aspects of daily life. The issue beyond science and discovery is application. How can one apply these results in a way which makes the discoveries more than simply part of the knowledge base of sociology and human behavior? Can we learn more if we can expand the discovery of these three mind-sets beyond the limited confines of this study of 50 respondents? In other words, can we apply this information to create better conferences, or at least better understand the audience’s predispositions towards what they want in a conference?

It will be difficult, if not impossible, to assign a person to the proper mind-set simply by knowing who the person IS. (Table 9) shows the distribution of the three mind-sets by gender, by age, and by how the person describes herself or himself when it comes to issues about the world. The distribution is fairly flat, so any opportunity to find a specific group of people with a designated mind-set if probably going to end up in failure.

Table 9. Distribution of the three mind-sets across gender, age, and self-report attitude towards conferences.

|

|

Mind-Set 1 – Responds to the topic

|

Mind-set 2 – responds to the type of presenter

|

Mind-set 3 – Responds to activities created for the after-conference

|

Total

|

|

Total

|

16

|

18

|

16

|

50

|

|

Gender

|

|

|

|

|

|

Male

|

9

|

9

|

6

|

24

|

|

Female

|

7

|

9

|

10

|

26

|

|

Age

|

|

|

|

|

|

No Answer

|

0

|

1

|

0

|

1

|

|

Age 15 to 29

|

3

|

3

|

2

|

8

|

|

Age 30 to 49

|

5

|

9

|

7

|

21

|

|

Age 50 plus

|

8

|

5

|

7

|

20

|

|

Attitude towards

conferences

|

|

|

|

|

|

Turned Off

|

0

|

2

|

2

|

4

|

|

Skeptical

|

1

|

3

|

3

|

7

|

|

Interested in the world

|

10

|

11

|

8

|

29

|

|

Passionate

|

3

|

2

|

2

|

7

|

|

No answer

|

2

|

0

|

1

|

3

|

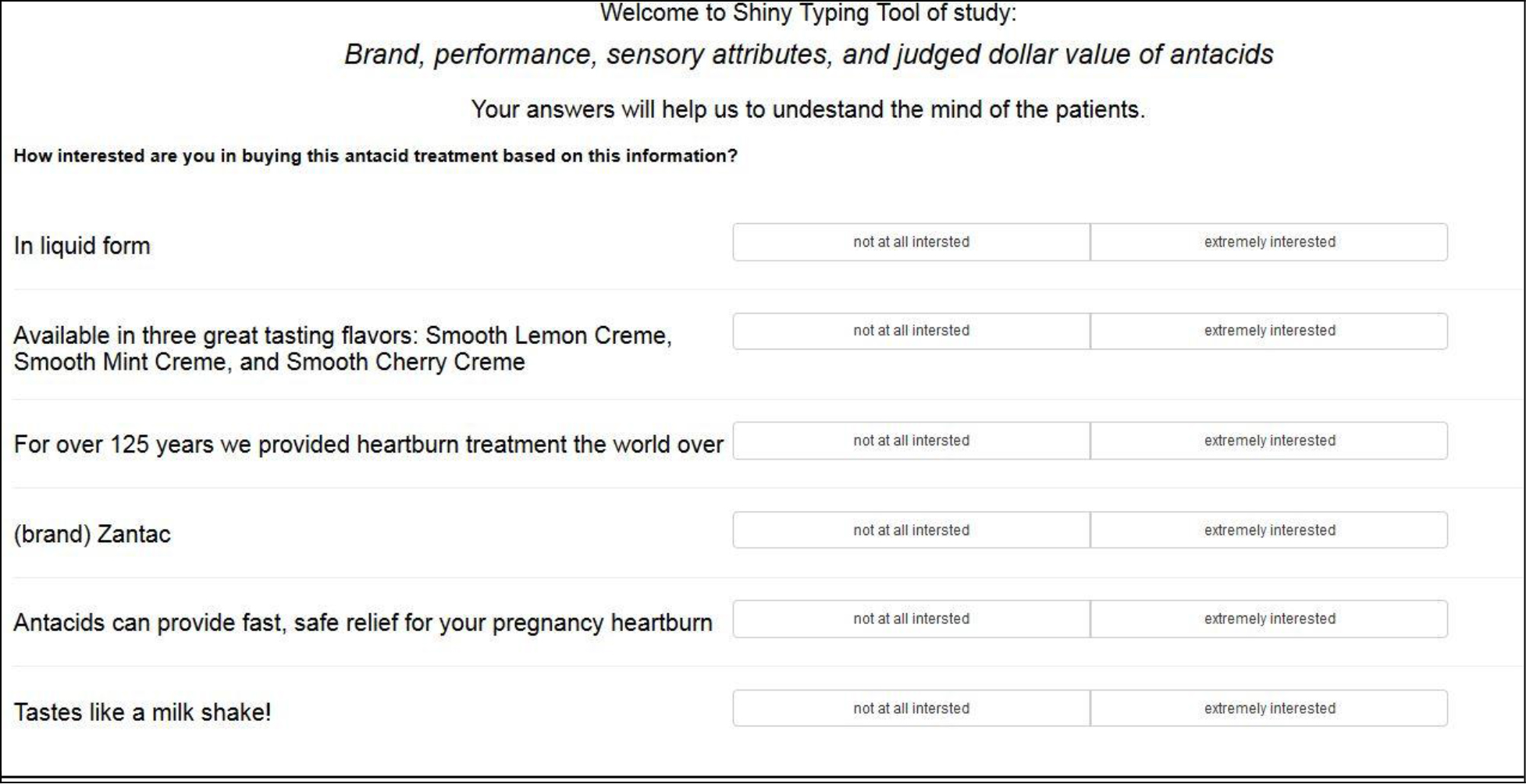

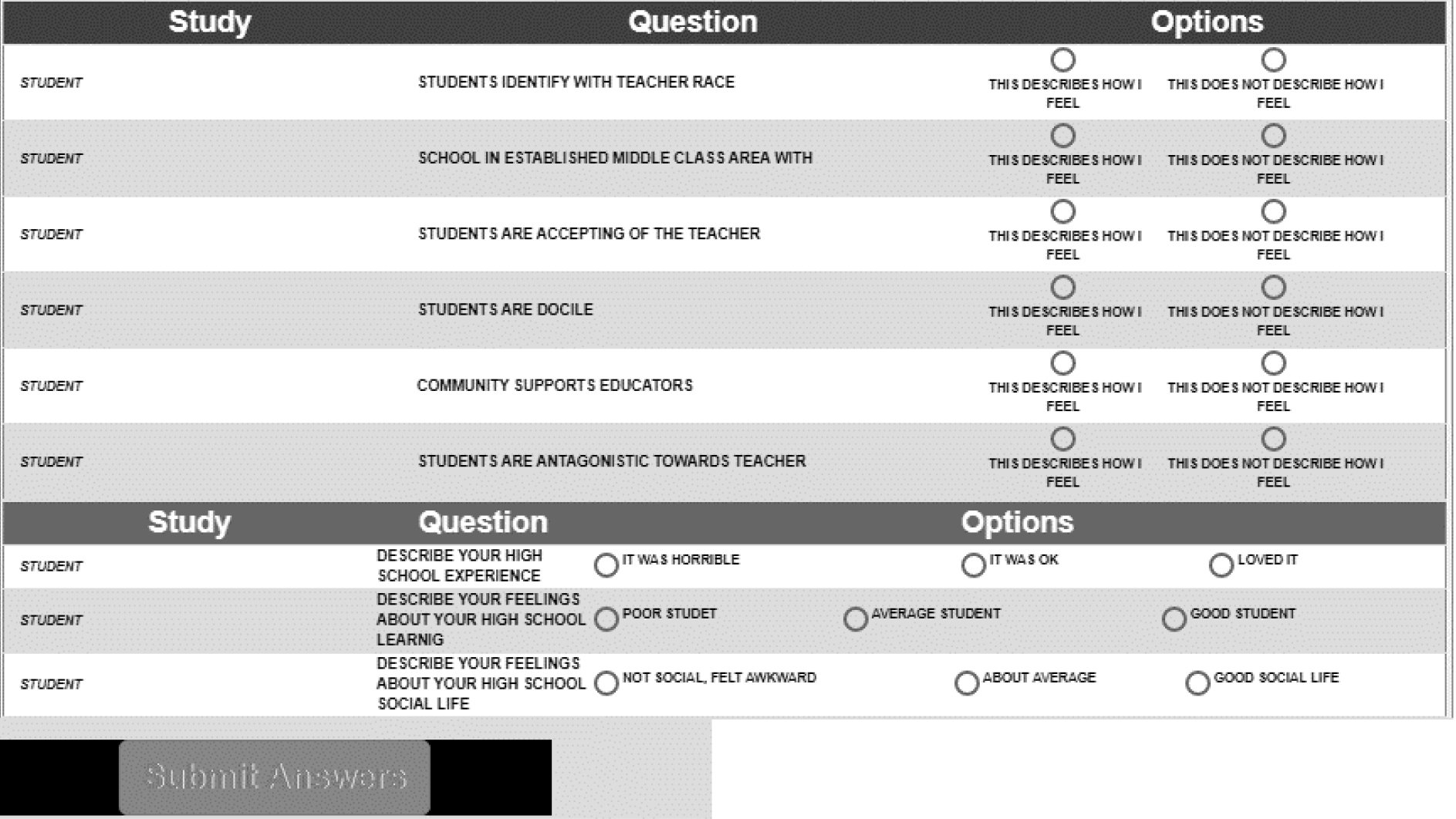

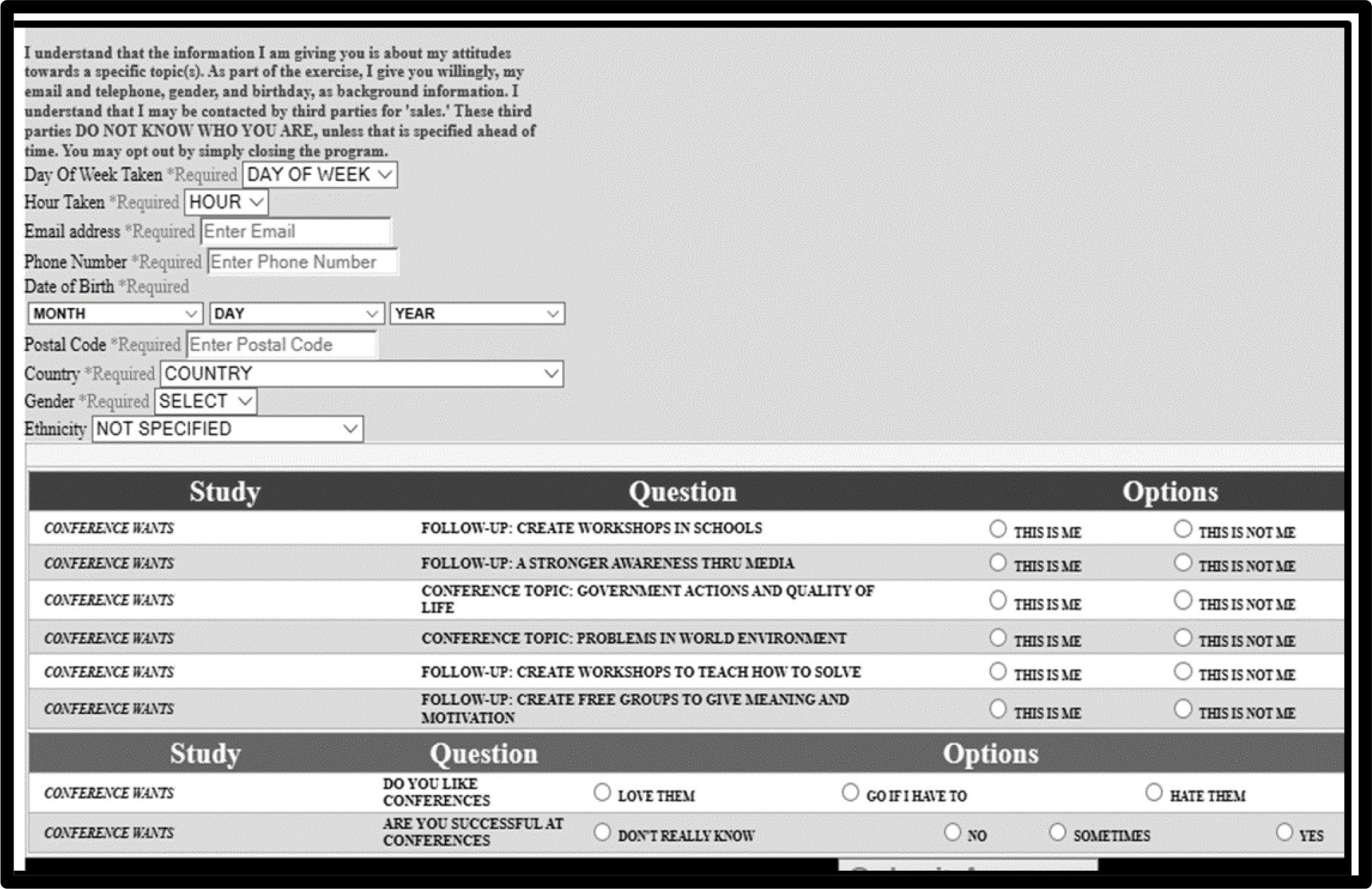

An alternative way to identify people comes from reducing the large-scale experiment to a set of questions, the PVI, the personal viewpoint identifier. The questions emerge from the actual experiment, the study described here. The PVI as currently designed, comprises a fixed number of six questions, with the questions themselves taken from the actual study, and thus varying from study to study. The respondent reads each question and chooses one of two answers. The total set of 64 patterns is mapped to the assignment to a mind-set. Thus, each of the possible patterns corresponds to the likely membership in one of the three mind-sets. The approach is empirical, based upon the actual study, with the PVI created shortly after the experiment.

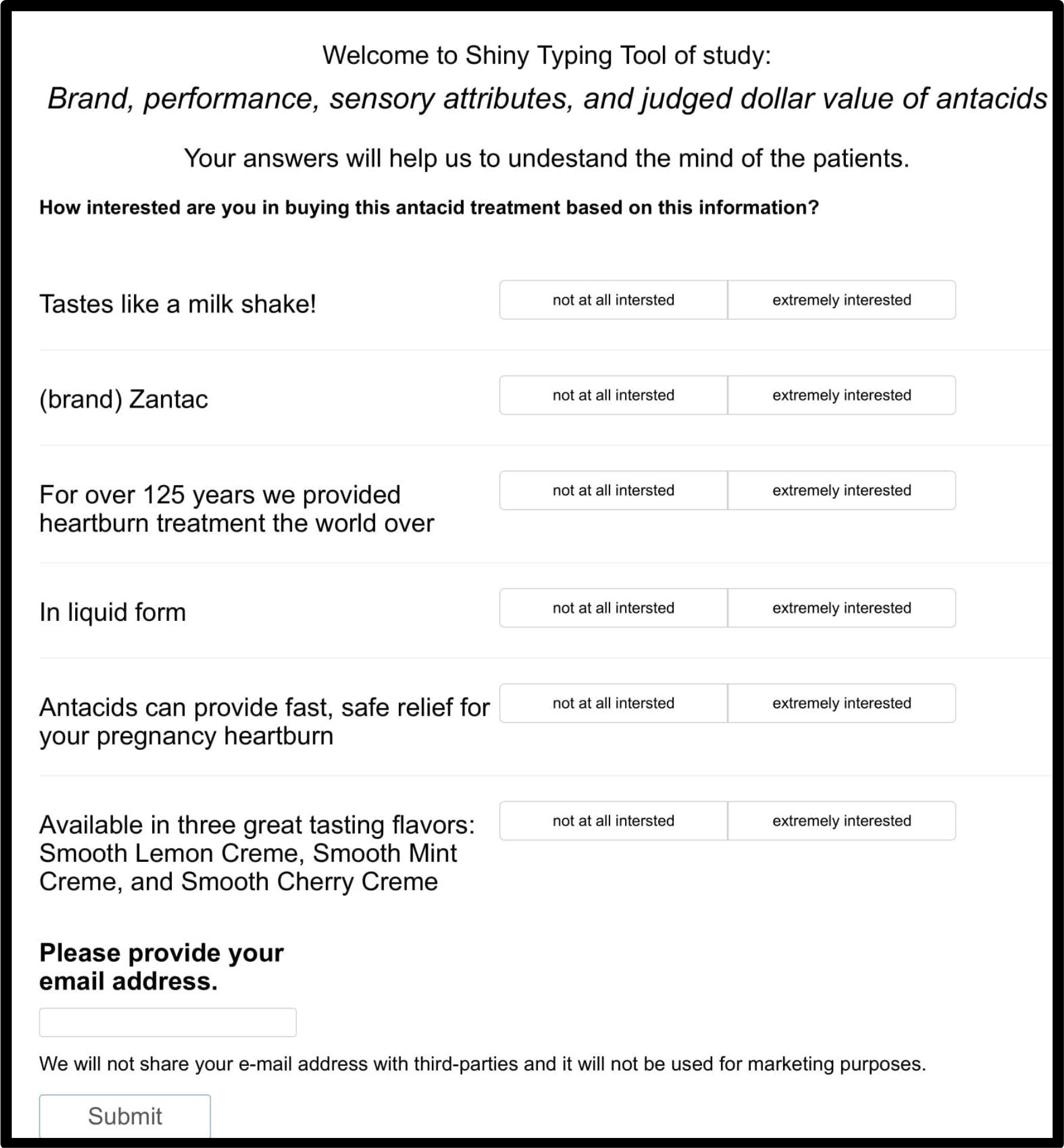

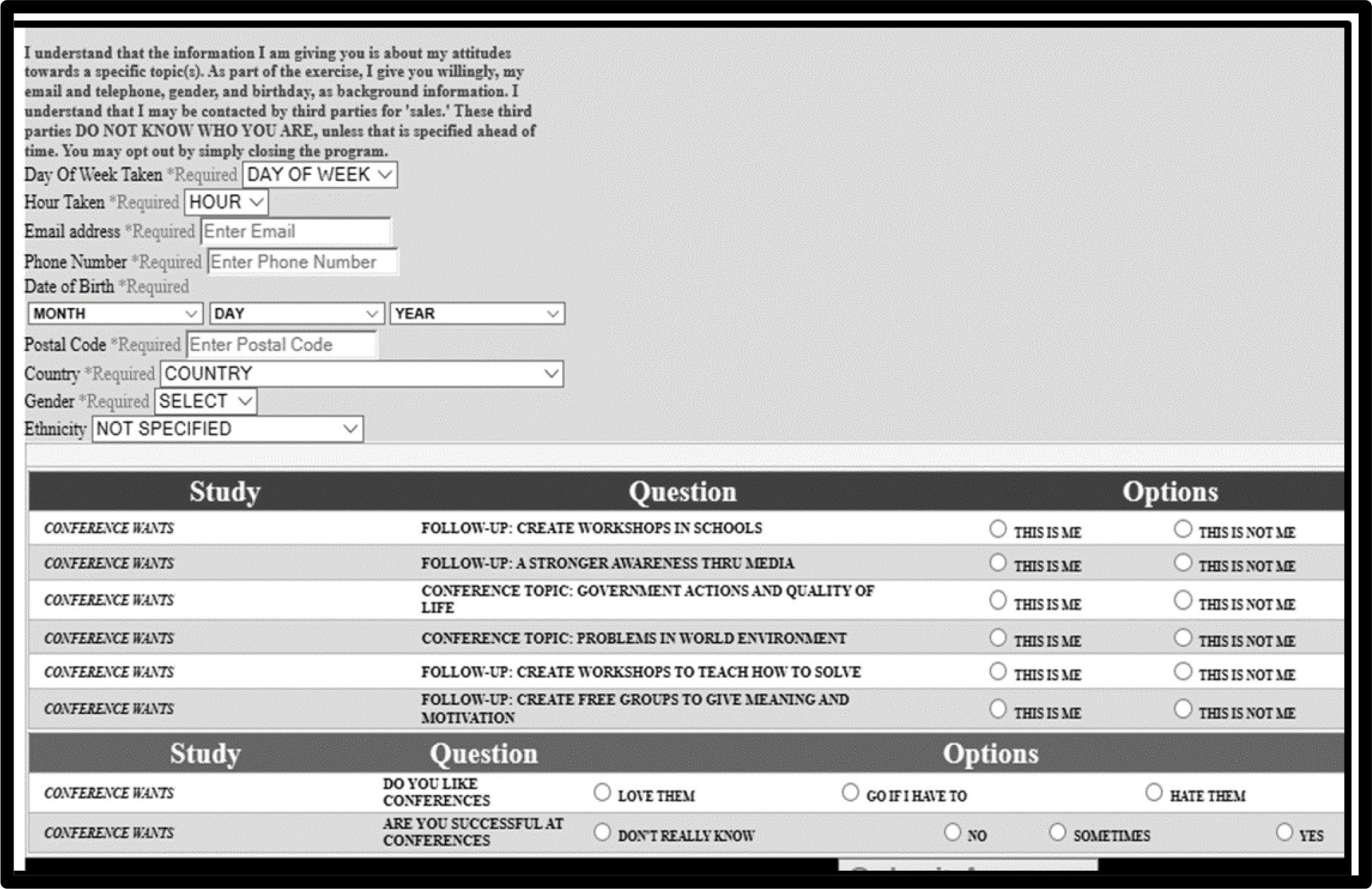

(Figure 1) shows the PVI as the respondent see it. It takes approximately 30–45 seconds to complete the PVI. The appropriate mind-set may either be returned in a report to the respondent as a motivating device to make the PVI fun, and in turn, the data may be store in a digital record. That record, obtained from thousands of people, may be used for marketing in the case of commercial events, and follow-up for other uses, e.g., for health when the topic is not conferences, but health-issues and concerns.

A parenthetical note: Without the knowledge of mind-sets, and the disturbing reality that these mind-sets distribute without any noticeable skew towards a specific group in the population, marketers, event planners and others continue to believe that who a person is co-varies with how a person thinks. That is, in the absence of such knowledge, one must use demographics and other variables. Rather than doing the simple Mind-Genomics experiment followed by a PVI for the topic, the strategy has evolved to using Big Data of low information density, coupled with very high-powered analytics. The metaphor is needing to rely upon powerful, expensive equipment in a mine where the gold is rare, rather than using simple equipment or even one’s own hands in a mine where the gold is abundant.

Figure 1. The PVI for conferences as the respondent would see it.

Response time

Beyond the aspect of what persuades at a cognitive level, aspects captured in the rating, lies a whole world of ‘processing,’ of psychological aspects to which the cognitive mind may not be privy. Experimental psychologists almost a century and a half ago recognized that beneath the surface responses to test stimuli lie many factors, such as attitudes, norms, and so forth. These factors govern the response but cannot be articulated.

Recent developments in Mind Genomics have focused on capturing the response time to vignettes, defined as the time between the appearance of the test stimulus and the response to the test stimulus. With the advent of today’s computer technology this information is readily available. The response times (often referred to in the literature as ‘reaction times’) become meaningful when they can be paired with specific stimuli, as they are in the Mind Genomics paradigm. That is, when the researcher can estimate the number of seconds that can be linked with each answer, it becomes possible to learn more about what engages the respondent. We don’t know what is happening, but we do know that some answers are processed more slowly (longer response times), and some elements are processed more quickly (shorter response times.)

The analysis of response times requires a slightly modified equation. The equation incorporates all the answers or elements as predictors, but there is no additive constant. The rationale is that in the absence of answers or elements in the vignette the response time is 0. We write the equation as follows:

Response time = k1(A1) + k2(A2) … k16(D4)

(Table 10) shows the response times for the three mind-sets generated from the mind-sets based upon ‘motivation’. The table shows the longest response times as shaded cells with bold font. What surprises in a delightful way is the observation that the different mind-sets pay attention in accordance with their mind-sets. The correspondence is not perfect, but there is a clear connection between what persuades/motivates and what people attend to. This is an area worth exploring in more detail.

Table 10. Estimated response times attributes to the different answers/elements, from each of the three mind-sets.

|

|

|

MS1

|

MS2

|

MS3

|

|

|

Most engaging – MS1 (responds to topic)

|

|

|

|

|

C4

|

expert: high government official in topic area

|

2.4

|

1.5

|

1.4

|

|

C1

|

expert: well-known university professor with to-do list

|

2.2

|

1.5

|

1.3

|

|

A4

|

conference topic: government actions and quality of life

|

2.1

|

1.6

|

1.7

|

|

A2

|

conference topic: problems teaching students to think critically

|

1.9

|

1.3

|

1.3

|

|

C2

|

expert: well-known author on topic

|

1.9

|

1.5

|

1.6

|

|

|

Most engaging – MS2 (responds to presenter)

|

|

|

|

|

B4

|

presenter: critical NGO .. non-governmental organization

|

1.0

|

2.0

|

1.2

|

|

|

Most engaging – MS3 (responds to after-conference activities)

|

|

|

|

|

D4

|

follow-up: create free groups to give meaning and motivation

|

1.7

|

0.9

|

2.2

|

|

D3

|

follow-up: a stronger awareness thru media

|

1.3

|

0.2

|

1.9

|

|

|

Less engaging

|

|

|

|

|

B3

|

presenter: well-known social activist

|

1.6

|

1.7

|

1.7

|

|

B1

|

presenter: talks about personal experiences and suffering

|

1.6

|

1.4

|

1.7

|

|

C3

|

expert: panel of business people

|

1.7

|

1.6

|

1.6

|

|

D2

|

follow-up: create workshops in schools

|

1.5

|

0.3

|

1.6

|

|

D1

|

follow-up: create workshops to teach how to solve

|

1.6

|

0.2

|

1.6

|

|

B2

|

presenter: video presentation narrated

|

1.3

|

1.4

|

1.5

|

|

A3

|

conference topic: loss of respect and empathy of people towards each other

|

1.7

|

1.0

|

1.3

|

|

A1

|

conference topic: problems in world environment

|

1.7

|

1.1

|

1.0

|

Discussion and conclusion

The literature of conferences is a growing one. The focus, however, is the nature of the specific conferences, from the point of view of the topic, and the influence of the topic. Few papers, if any, focus on the psychology of the listener, other than perhaps papers dealing with the role of conferences in the development of a person’s professional career. This paper introduces a new world of understanding conferences, not so much from the topic and the importance of the topic to the world, but rather conferences as a part of a person’s quotidian, daily life. As noted in the presentation of Mind Genomics, the world of the everyday presents us with a way to understand people. With the tools of Mind Genomics, we begin a new psychology of people, the psychology of the ordinary, of which conferences as a topic constitute one facet.

The results from the data should not surprise, although the reality is that were one to be asked about ‘what makes a good conference,’ one might not emerge with answers as clear as those provided by Mind Genomics. Nor, in fact, would there be the specifics provided by the cognitively rich stimuli used in Mind Genomics studies, specific, meaningful statements. The initial foray into ‘what interests a person in a conference’ shows the simplicity by which one can begin to create a detailed understanding of a person’s mind with regard to a topic. The call now should be for systematics, namely structured investigations. Should the topic of such investigations be ‘conferences,’ and the current study comprises, the next steps would be the way the conferences are organized, the nature of the material presented, the tonalities of the presentation, the venues, and so forth. Following this structured approach, it is likely that an entire “foundational knowledge infrastructure” (FKI) about conferences might be constructed within the period of a year, providing insight to the specific topic of conferences, but potentially greater insight into the nature of social interactions of a formal nature. The potential of a set of FKI’s, updated each year, and done cross-sectionally within a topic, across topics, within a country, and across countries, beckons, almost a ‘Wiki of the Mind.’

Acknowledgement

Attila Gere thanks the support of Premium Postdoctoral Research Program of the Hungarian Academy of Sciences.

References

- Clark AM, Friedman EJ, Hochstetler K (1998) The sovereign limits of global civil society: a comparison of NGO participation in UN world conferences on the environment, human rights, and women. World Politics 51: 1–35.

- Gordenker L (1995) NGO participation in the international policy process. Third World Quarterly 16: 543–556.

- Ritchie C (1995) Coordinate? Cooperate? Harmonise? NGO policy and operational coalitions. Third World Quarterly 16: 513–524.

- Van Rooy A (1997) The frontiers of influence: NGO lobbying at the 1974 World Food Conference, the1992 Earth Summit and beyond. World Development 25: 93–114.

- Gardner SK, Barnes BJ (2007) Graduate student involvement: Socialization for the professional role. Journal of College Student Development 48: 369–387.

- Jacobs N, McFarlane A (2005) Conferences as learning communities: some early lessons in using ‘back-channel’technologies at an academic conference–distributed intelligence or divided attention? Journal of Computer Assisted Learning 21: 317–329.

- Kowalsky M (2012) Networking at conferences: Developing your professional support system. Knowledge Quest 41: 60.

- Shoaff-Ballanger SM, Davis DJ (1992) Professional conferences for art educators: A pilgrimage to excellence. Art Education 45: 37–44.

- Carsrud AL, Palladino JJ, Tanke ED, Aubrecht L, Huber RJ (1984) Undergraduate psychology research conferences: Goals, policies, and procedures. Teaching of Psychology 11: 141–145.

- Gunawardena CN (1995) Social presence theory and implications for interaction and collaborative learning in computer conferences. International Journal of Educational Telecommunications 1: 147–166.

- Hines SS (2014) What do library workers want from professional conferences? In: Revolutionizing the development of library and information professionals: Planning for the future (1–16). IGI Global.

- López-Pastor VM, Monjas R, Manrique JC (2011) Fifteen years of action research as professional development: Seeking more collaborative, useful and democratic systems for teachers. Educational Action Research 19: 153–170.

- Reinhardt W, Ebner M, Beham G, Costa C (2009) How people are using Twitter during conferences. Creativity and Innovation Competencies on the Web. Proceedings of the 5th EduMedia Pg No: 145–156.

- Werner SE, Kenefick C (2005) A Primer for effective organization of professional conferences. Medical Reference Services Quarterly 24: 39–54.

- Kahneman D, Egan P (2011) Thinking, fast and slow. New York: Farrar, Straus and Giroux.

- Moskowitz HR, Gofman A, Itty B, Katz R, Manchaiah M, et al. (2001) Rapid, inexpensive, actionable concept generation and optimization: the use and promise of self-authoring conjoint analysis for the food service industry. Food Service Technology 1: 149–167.

- Moskowitz H, Gofman A, I novation Inc (2003) System and method for content optimization. U.S. Patent 6: 662,215.

- Moskowitz HR, Gofman A, Beckley J, Ashman H (2006) Founding a new science: Mind genomics. Journal of sensory studies 21: 266–307.

- Luce RD, Tukey JW (1964) Simultaneous conjoint measurement: A new type of fundamental measurement. Journal of mathematical psychology 1: 1–27.

- Green PE, Rao VR (1971) Conjoint measurement for quantifying judgmental data. Journal of marketing research 8: 355–363.

- Green PE, Srinivasan V (1990) Conjoint analysis in marketing: new developments with implications for research and practice. The journal of marketing 54: 3–19.

- Box GE, Hunter WG, Hunter JS (1978) Statistics for experimenters, New York, John Wiley.

- Gofman A, Moskowitz H (2010) Isomorphic permuted experimental designs and their application in conjoint analysis. Journal of Sensory Studies 25: 127–145.

- Moskowitz HR, Gofman A (2007) Selling blue elephants: How to make great products that people want before they even know they want them. Pearson Education.

- Dubes R, Jain AK (1980) Clustering methodologies in exploratory data analysis. Advances in Computers 19: 113–238.