Abstract

We present a new approach to designing a school and its curriculum. The approach is based upon experimental design of ideas, in which the researcher combines different features of a curriculum, creates a set of vignettes or test combinations, obtains responses from prospective students and others, and then deconstructs the response into the contribution of each individual element or idea. The approach is efficient, cannot be ‘gamed,’ and enables the designer to identify new to the world mind-sets of prospects. These mind-sets entail different ideas about what members of each mindset want. We finish by showing a personal viewpoint identifier, which enables the designer to assign a new person, student, faculty, or donor to one of the mind-sets uncovered. This approach can become a tool for designing a health-professional curriculum.

Introduction

With the increasing costs of medicine in these early decades of the 21st century, the profession of nursing is undergoing a renaissance. Nurses are becoming recognized as major players in the profession of health care [1, 2]. Nursing has advanced from care to a professional skill in various specialties growing towards a graduate profession status [3, 4]. As with any profession, there is a continuing need to monitor what the desire of customers. This study examines expectations of the public from nursing school. We present the general population with a variety of concepts or ‘vignettes’ about a nursing school, measure their reactions to these vignettes, and then uncover the most appealing concepts per mind-set.

The professional role of nurses is based on the socialization of a set of patterns of behavior. These patterns are embodied in the patient-nurse interactive relationship. The behavior requires skills, knowledge and behaviors based on values, attitudes, guided by the overarching goal of promoting a positive clinical outcome and patient well-being [5]. Nurses assimilate their professional identity through teaching and clinical practice, a combination which generates the ability to cope with the tension between the professional standardization and the nurse’s own individuality and proclivities [6]. Professional education in nursing functions as a disciplinary mechanism design to engender a professional ‘ideology’ and a professional identity as a medical profession stressing the biomedical model [5]. In contrast, the reality of nurses in clinical practice eventuates into what might well be described as shock as they witness traumatic events in the healthcare environment. The unexpected events which occur, often quite frequently, coupled with the individual styles of behavior displayed by senior professional nurses lead to anxiety and dissonance, responses often evident in the published literary discourse regarding the education in Nursing. Anxiety and dissonance are responses to the chasm separating the “theoretical-educational nursing learned in the classroom, the theory as opposed to the reality, the clinical practice experience at hospitals.

There is a looming gap between professional idealism and clinical- practice realism [7, 8]. Professional idealism highlights values of compassion, empathy, holism, cultural competency, and patient-centered care [9, 10]. Reality occasionally eventuates into other behaviors. The ability of nursing students to introject and then realize these values is inhibited by organization constraints and processes, burnout of nurses and staff shortages. All of the former have negative consequences, diminishing the opportunity to develop meaningful relationships with patients, and chipping away at both the satisfaction and sense of mission among nursing students [11]. After completing their education, nursing students were found divide into at least three groups; sustained idealists, compromised idealists and crushed idealists, respectively [12]. There are other effects [8]. views the professional socialization as leading to desensitization toward patients due to experiencing cynicism of senior nurses, and anxiety accompany their efforts to cope with and ameliorate the suffering patients in their care. To preserve themselves in a stressful, demanding at times, chaotic work environment, upon completing their education, nurses adapt emotional desensitization [5, 13]. The idealism of new entrants to Nursing gives way to disillusion after the nurses begin to face an onslaught of never-ending practical concerns [5]. Vulnerable and disoriented nurses, new to the nursing occupation, aspire to “fit in,” resulting in radical changes in understanding, attitudes and behavior towards patients.

Nurses Encounter Three Kinds of Dualism:

- The good nurse they introjected as themselves versus the bad nurse they encounter in hospitals.

- their genuineness based on their emotions versus the cynicism they experience as they witness nurses who only care about money

- An ambiguous identity of authority of the nurses who supervise them, and the lack of morality in the hospital setting.

The Nursing literature concludes that socialization into professional nursing is deeply problematic. Nurses who identify with their professional ideals throughout their education often end up losing professional values, and decline from their ideals to accepting the fact that they compromise, and deliver poor care [14, 15, 16]. The desire to articulate the impact of nursing practice propels professional preparation beyond the existence fuzzy fringes of medicine towards a unique contemporary identity [2].

This study represents an exploration of a method for understanding what the ‘public’ wants in a nursing school. The objective is to create a system to guide education, the system grounded in the feelings of the public towards general, operationally feasible topics and strategies that the nursing school can address. The success of the method (Mind Genomics) has been in understanding the mind of people for a variety of situations. With this success it may be possible for Mind Genomics to contribute to the world of nursing education.

The Background and Contribution of Mind Genomics to Aid Understanding

Mind Genomics is an emerging science, the focus of which is the experimenting science of the everyday. Research tells us a great deal about ‘what is’ but does not tell us how people make decisions about the quotidian, ordinary issues of their daily lives. We know that people have definite opinions about what they want and why they want it; polls and surveys provide us that information. We do not know however, their weighting schemes when they choose what to do. We know what people say, retrospectively, but we do not have a deep knowledge of the decision criteria for the events of the everyday. Rather than asking people to say what they would do Mind Genomics presents people with different combinations of features of a typical situation (here a nursing school) and instructs them to rate the entire combination. From the pattern of their choices for different combinations, Mind Genomics emerges with a set of weights, showing which option(s) or feature(s) in the combinations really ‘drives’ the decision. Through experiment, therefore, Mind Genomics reveals the ‘mind’ in a way that surveys and observations cannot. Mind Genomics shows causality, at least in terms of what the respondent says she or he would do when presented with the type of information one would encounter in a situation. The origin of Mind Genomics comes from statistics experimental design [17] from mathematical psychology conjoint measurement [18] from marketing applications of conjoint measurement [19, 20] and from psychophysical thinking [21]. The foundations have been explicated in several seminal papers, including how the science was founded [22] the major applications [23] and some of the specific mathematics which make the approach and the analyses possible, and actually quite straightforward [24]. The original approaches were patented. Mind-Genomics has been applied to health in several recent studies [25–30].

The Mind Genomics Method

Mind Genomics begins with the Socratic method of question and answer.

Step 1 defines the topic, which is a ‘New Nursing Services Company’

This first step seems so obvious, but it is important to the Mind Genomics experiment that each question and its associated set of answers be relevant to the topic.

Step 2 asks four questions which ‘tell a story’

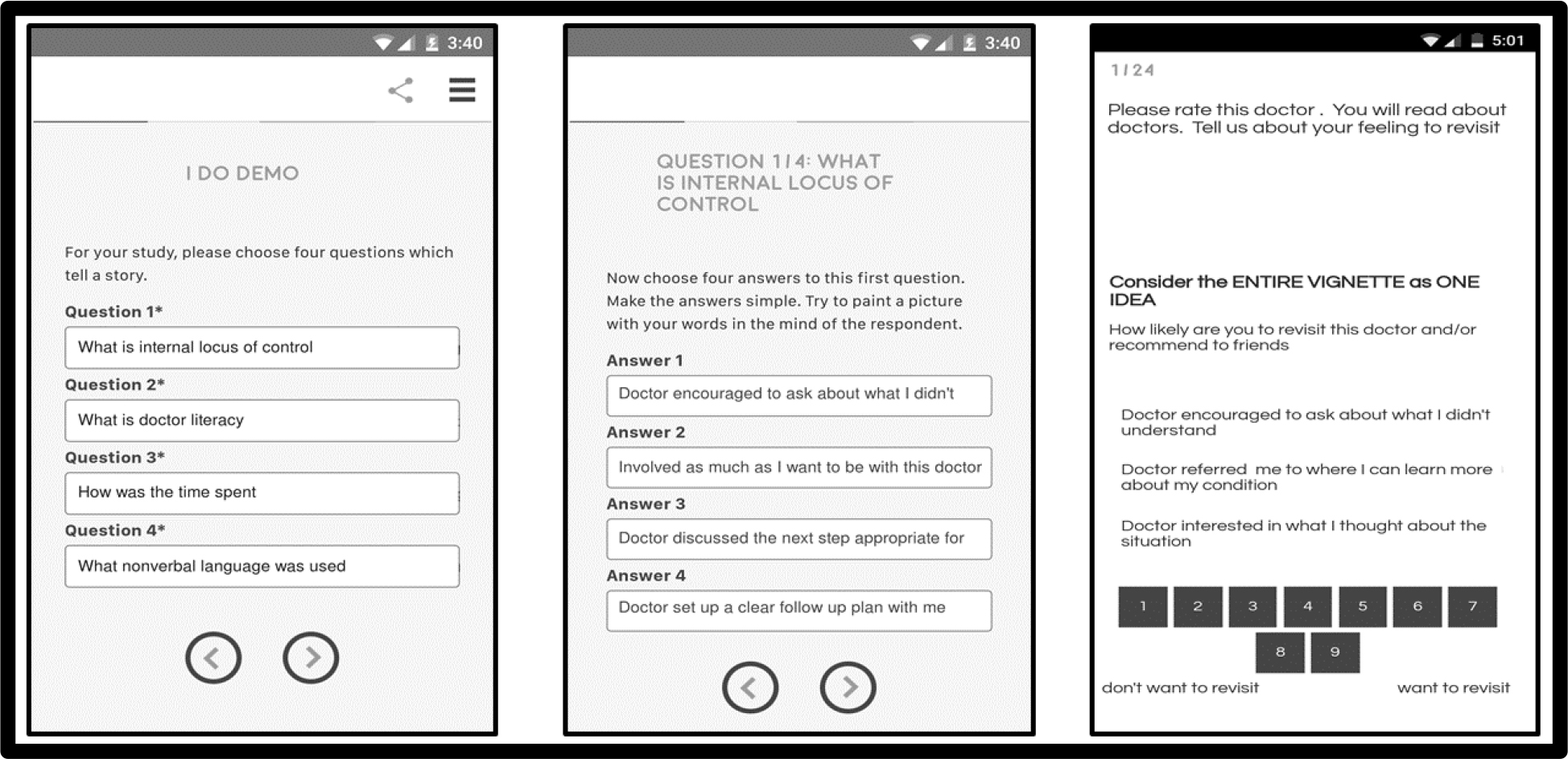

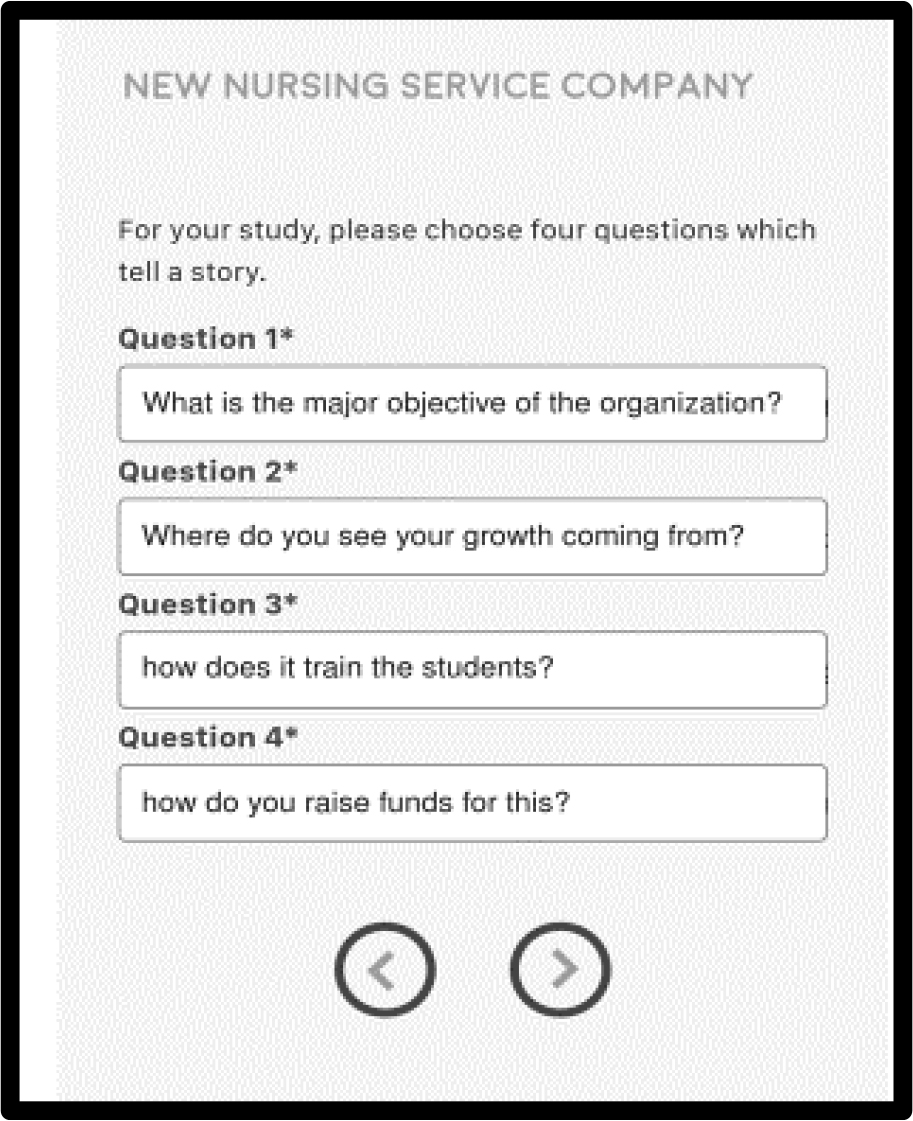

As simple as that sounds, it requires a great deal of thinking. We are accustomed to facts, not to systematic thinking about a problem. Figure 1 show a screen shot where the researcher is instructed to write out the four questions.

Figure 1. Screen shot showing the screen in the program where the researcher must ask the four questions.

Step 3 Instructs the Researcher to Give Four Different Answers to Each Question

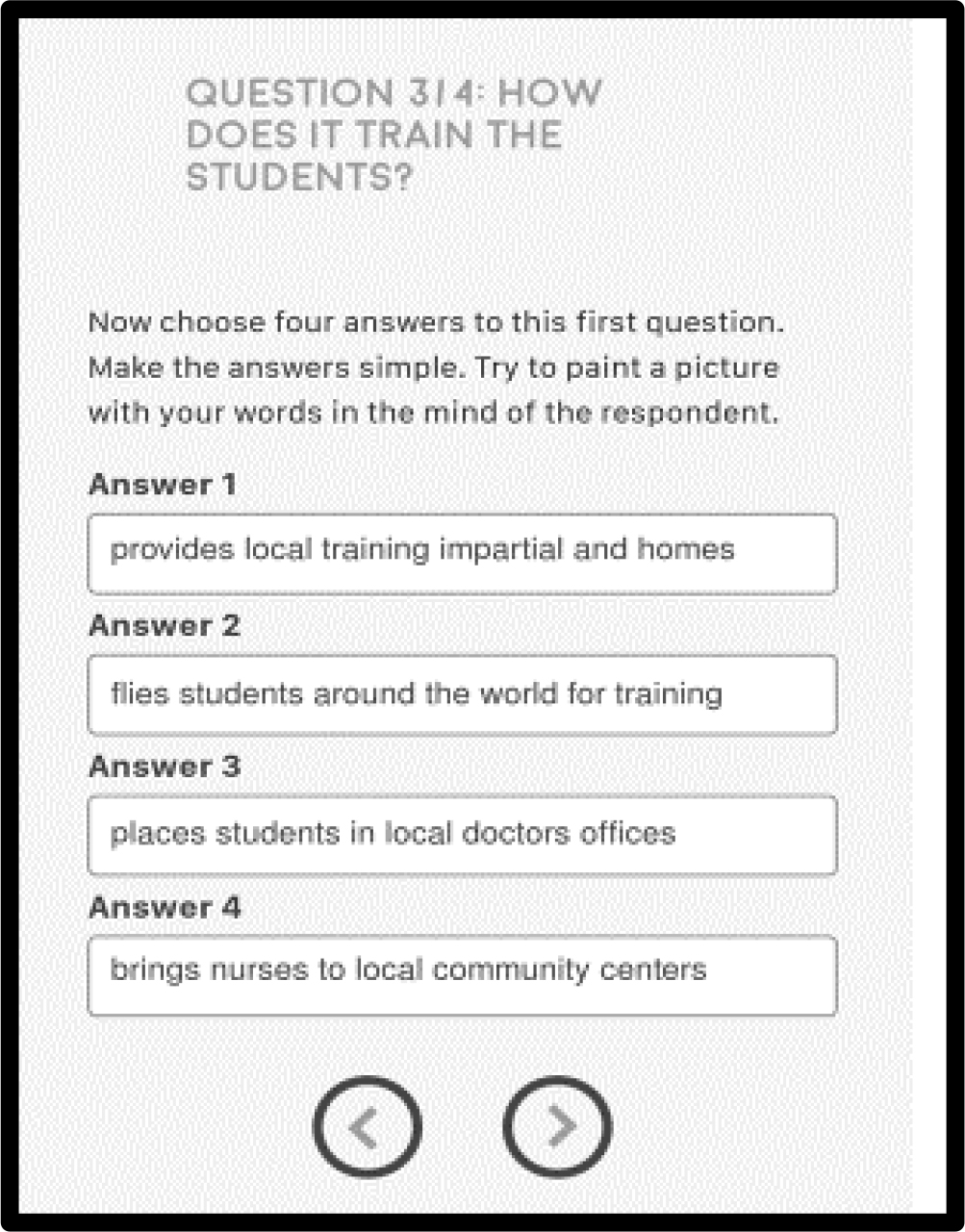

It is the answers which will be presented to the respondent. The answers may either be simple words when the topic is clear and concrete, easy to visualize (here a nursing school), or may be simple phrases when the concept is not clear and concrete, not easy to visualize (e.g., the daily routine of the nursing student in the school.). Figure 2 shows a screen shot of the page where the researcher must provide answers to question #3 (How does it train the students?)

Figure 2. Screen shot showing the page where the researcher provides the four answers to question #3.

The final array of questions and answers appears in Table 1. It will be the answers, in combination, which comprise the test stimuli. The respondent never sees the actual questions motivating the answers. The questions are simply there to create the structure and to motivate the answers.

Table 1. The four questions and the four answers to each question.

|

|

Question A: What is the major objective of the organization? |

|

A1 |

to teach |

|

A2 |

to prepare |

|

A3 |

improve local health |

|

A4 |

serves as test location for new medical development |

|

|

Question B: Where do you see growth coming from? |

|

B1 |

supported and promoted by local hospitals |

|

B2 |

allies closely with local community |

|

B3 |

allies closely with government |

|

B4 |

supported by UN |

|

|

Question C: how does it train the students? |

|

C1 |

provides local training in homes |

|

C2 |

fly students around the world for training |

|

C3 |

places students in local doctor’s offices |

|

C4 |

brings nurses to local community centers |

|

|

Question D: how do you raise funds for this? |

|

D1 |

supported by government contributions |

|

D2 |

supported by citizens paying low fee for service |

|

D3 |

allow researchers to work and help support |

|

D4 |

supported by public appeals |

Experimental Design and Test Vignettes

The foundation of Mind Genomics is the use of experimental design to combine disparate ideas, present these ideas to the respondent, obtain ratings, and relate the presence/absence of the ideas (also called answers or elements) to the ratings. At first glance one might confuse Mind Genomics with a survey, because a survey instructs the respondent to answer questions. The difference is that Mind Genomics is an experiment. The stimuli are pre-defined, systematic and structured mixtures of messages. The rating is assigned by the respondent based upon the impression of the entire message. The respondent assigns a single rating, mentally weighting the different elements in the vignette. It is the mental weights which are of interest to the researcher, for they reveal what are important features, and what are unimportant features.

The ratings are analyzed by the well-accepted method of OLS (ordinary least-squares, curve fitting) regression. The OLS reveals causality, how the individual elements in the vignettes or combinations ‘drive’ the ratings. It is also worth noting that the same element or answer appears many different times, continually combined with a variety of answers from other questions. This strategy produces, in the words of psychologist William James of Harvard University in the end of the 19th Century a ‘blooming, buzzing confusion,’ a phrase taken from his description of the world of the baby, but apt for the way the combinations of messages must appear to the respondent. The continual mixing and remixing of messages make it virtually impossible for the respondent to ‘game’ the system. The Mind Genomics experiment reveals quite quickly how the respondent really feels about the combinations, rather than providing answers which might be appropriate and ‘politically correct.’

The experimental design used in this study comprises 24 different vignettes or combinations. Each vignette comprises at most one answer from each question, but in many vignettes one or two questions do not contribute an answer, so that vignette is said to be ‘incomplete.’ The rationale for this strategy is a statistical consideration, namely, to allow the subsequent regression analysis (see below) to provide absolute values for the coefficients.

Every respondent evaluated a unique set of 24 vignettes. Each set was constructed so that the combinations of elements differed, even though the basic structure of the experimental design was maintained. This approach, so-called ‘permutation of the design’[24] allows the Mind Genomics experiment to measure responses to a great number of the possible combinations, albeit with each combination appearing only once or twice across all the respondents. This permutation strategy can be likened to the MRI, which takes ‘pictures’ of underlying tissue from many angles, and combines them by computer to create a three-dimensional image. Each picture in the MRI may be ‘noisy’ just like the data underlying each vignette is ‘noisy.’ Nonetheless, it is the pattern of pictures, and the pattern of responses which emerges clearly in both cases, even though the individual observations are noisy. In contrast, conventional research, specifically conjoint analysis, suppresses the noise through replication, but only covers a limited number of combinations.

A parenthetical note about worldviews in science. Much of science operates on the world view of suppressing noise by replicating the study many times, in order to get a better estimate of the ‘central tendency, i.e., the mean. Inferential statistics tells us that the precision of the measurement increase with the square root of the number of observations. Following this dictum, most researchers opt to increase the number of respondents testing the same stimuli in an experiment or responding to the same questionnaire in a survey. Mind Genomics differs because it looks at the patterns generated by many different combinations, not the response to one combination measured with great precision.

Executing the Mind Genomics study

The actual study takes approximately 3–5 minutes in the field, once the respondent is invited. The effort to run studies is simplified by a service, Luc.id Inc., which hosts on-line surveys, and is linked to the Mind Genomics program as an option. One can also send the study link to other respondents, but the approach of using a panel makes the recruitment more objective, and the panelists more cooperative, since they already do other studies.

The 40 respondents who participated were invited by Luc.id through a link. Most respondents participated within the first hour of launching the study, and all participated within the first two hours, allowing the Mind Genomics experiment to become one step in an easily iterated process. One need not know the answer. One can iterate quickly. The answer, if there is one, appears within the first 1–3 iterations, and certain by the fifth iteration. The key phase is ‘if there is one,’ i.e., if there is a real answer.

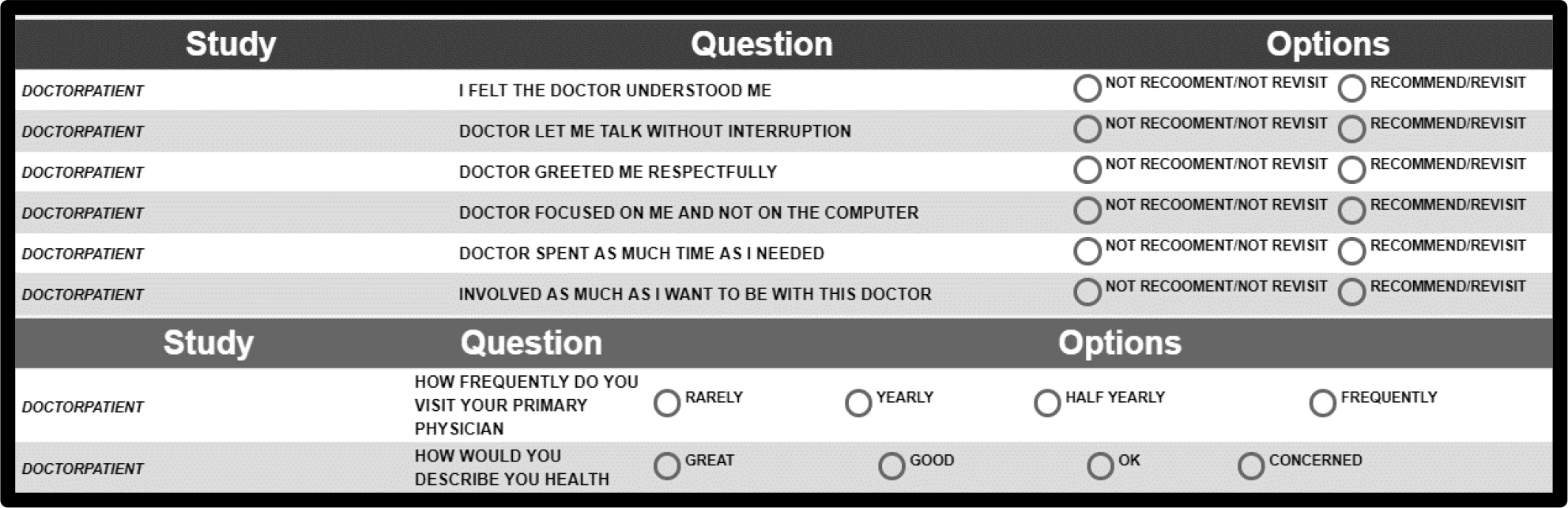

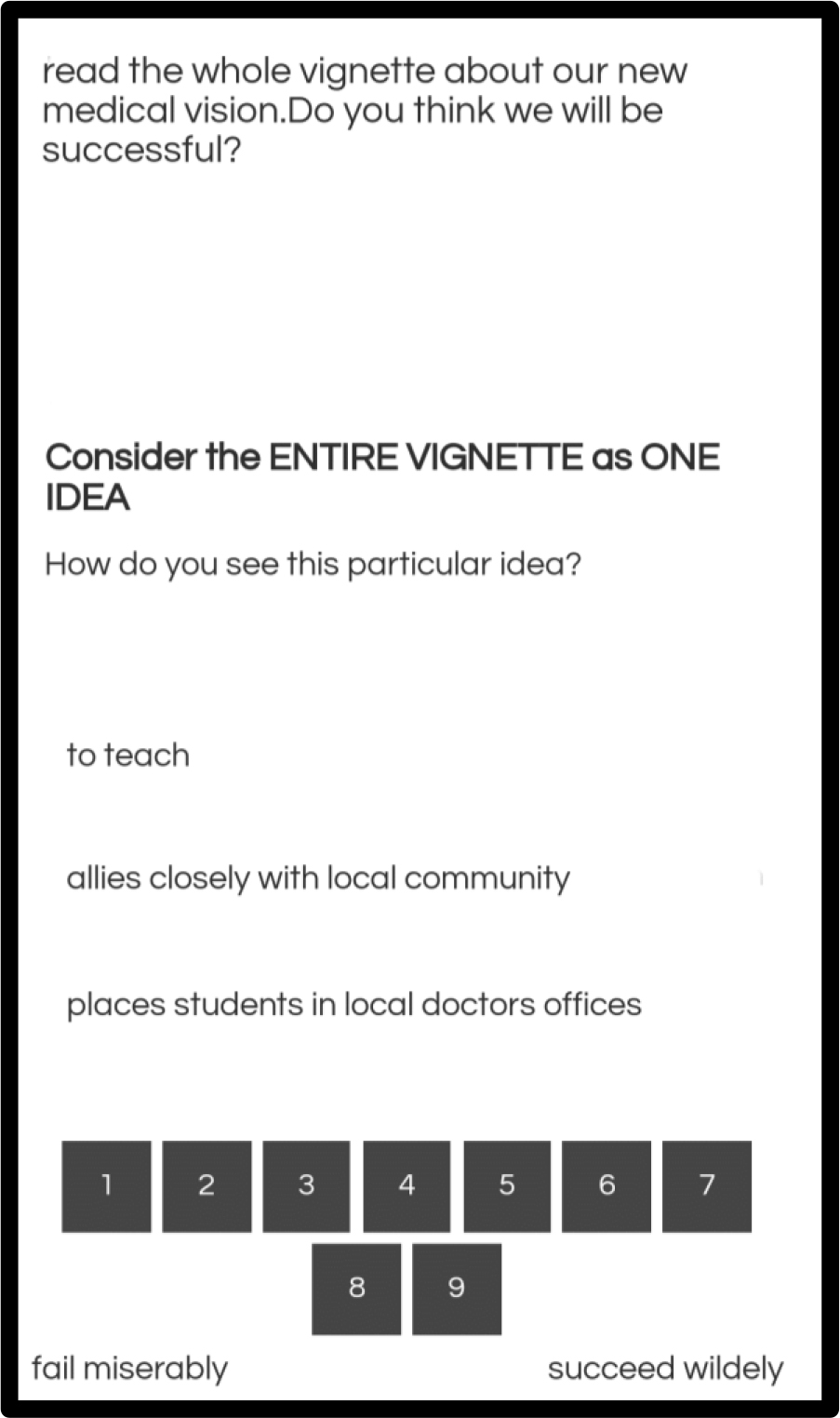

The respondent was first presented with an introduction, which simply said: Read our new medical vision. Do you think we will be successful? The respondent then read single vignettes, combinations of elements as shown in Figure 3. The respondent rated the vignette on the 9-point scale. The computer acquired the response, measured the response time between the appearance of the vignette and the rating, and then automatically sequenced to the next vignette. The typical response times are approximately 5 seconds (see Table 2). As just noted above, entire sequence takes 3–5 minutes at most, an experience which is not onerous to those accustomed to surveys lasting 30 minutes but may irritate the purist who wants the respondent to have an experience which is as much fun as a game.

Table 2: Average ratings for total panel, self-defined subgroups, and three emergent mind-sets.

|

|

9-Point Rating |

Binary: Positive-Outcome (7–9) → 100 |

Binary: Negative-Outcome (1–3) → 100 |

Response Time |

|

Total |

5.4 |

36 |

21 |

2.6 |

|

Female |

5.6 |

39 |

20 |

2.9 |

|

Male |

5.2 |

32 |

22 |

2.2 |

|

Age 15–24 |

5.3 |

33 |

28 |

1.6 |

|

Age 25–40 |

5.5 |

39 |

17 |

2.0 |

|

Age 41+ |

5.5 |

36 |

19 |

4.0 |

|

Mind-Set 3E |

5.6 |

42 |

23 |

2.4 |

|

Mind-Set 3D |

5.3 |

31 |

21 |

2.7 |

|

Mind-Set 3C |

5.5 |

37 |

18 |

2.8 |

Figure 3. Example of a test vignette, configured for the smart phone.

Transforming the Data

The initial results come in the form of 9-point Likert scales, easy to create and administer, but very difficult to interpret. Indeed, it is not surprising that the standard practice of consumer research is to transform the 9-point rating scale (or other type of rating scale) to a binary scale, more easily understood by managers. Managers who are tasked with the job of ‘doing something with the data’ often ask simple questions like ‘what does an 9 or an 8 mean on the 9-point scale?’ or ‘should I be worried if I got a 5 or lower?’ and so forth.

One ongoing solution to the problem of interpreting the scale simply divides the scale into two parts, often of unequal size. We follow the conventions of consumer research, creating two new scales:

Positive-Outcome

Ratings 1–6 are converted to 0 to denote that these are ‘not positive’ outcomes. They are not ‘Negative-Outcomes,’ but rather just not positive ones. Ratings of 7–9 are converted to 100 to denote that these are ‘positive’ outcomes. The choice of the cut-point is arbitrary, and can be made more stringent by including only ratings of 8 or 9, or even only 9, and less stringent by including ratings such as 6–9, rather than 7–9 as ‘positive.

Negative-Outcome

Ratings of 1–3 are converted to 100 to denote that these are ‘negative’ outcomes. Ratings of 4–9 are converted to 0 to denote that these are not ‘negative’ outcomes. They are not Positive-Outcomes, necessarily, but certainly not Negative-Outcomes. The arbitrary choice holds once again, with possible cut-points being 1–2 as 100, or even only 1 and 100.

A very small random number (<10–5) is added to each rating in order to ensure that there is some variability within an individual’s ratings, were that individual to limit the ratings to regions where all of their ratings for the vignette would be coded either 0 or 100. Such a situation would cause the individual-level regression modeling to fail. The small random number does not affect the regression model, while ensuring the necessary variation in the dependent variable in order for the regression model to run.

Initial Results – Average Ratings Across Groups

A logical first analysis looks at averages for total and across groups, to determine whether there are any dramatic group to group difference. Table 2 shows the averages for the total panel and for key subgroups as well as three emergent mind-sets to be explicated later. The ratings suggest only a modest level of belief in the success of the enterprise, on average. It will have to be the individual elements which propel success, and not simply the basic idea.

The response time (RT) measured in seconds shows some interesting differences among groups. Females take longer to read the vignettes than do males, on average (2.9 seconds vs 2.2 seconds.) Older respondents take longer to read the vignettes than do younger respondents (4.0 seconds for those age 41+ versus a very fast 1.6 seconds for respondents ages 15–24.)

Despite these differences, we still do not know the relation between the individual elements in the vignettes and the Positive-Outcome, the Negative-Outcome, or the response time, respectively. The analysis of the data by deconstructing the patterns laid out through the experimental design will allow us a far better understanding of the mind of the respondent.

Modeling

The experimental design ensures that the 16 elements or answers are statistically independent of each other. By pooling together all data we generate a database from which we trace ‘causality,’ or the relation between the elements that we put into the vignettes and the responses that individuals make.

The models for the Positive and the Negative-Outcomes are estimated with an additive constant and appear in (Table 3). The additive constant is modest for Positive-Outcome (38) and quite low for Negative-Outcome, respectively (16). We conclude that the respondents feel that it will have to be the element themselves which must do a lot of the work to convince the respondent that there will be a good outcome.

Table 3. Parameters of the equations relating the presence/absence of the 16 elements to Positive-Outcomes (ratings 7–9 converted to 100), Negative-Outcome (rating 1–3 converted to 100), and response time (in seconds.)

|

|

|

Positive-Outcome |

Negative-Outcome |

Response Time |

|

|

Additive constant |

38 |

16 |

NA |

|

A1 |

to teach |

3 |

1 |

0.3 |

|

A2 |

to prepare |

2 |

-1 |

0.2 |

|

C4 |

brings nurses to local community centers |

2 |

0 |

0.9 |

|

B2 |

allies closely with local community |

1 |

5 |

0.8 |

|

C1 |

provides local training in homes |

1 |

-1 |

1.2 |

|

C3 |

places students in local doctor’s’ offices |

1 |

-3 |

0.9 |

|

A3 |

improve local health |

0 |

0 |

0.2 |

|

B1 |

supported and promoted by local hospitals |

0 |

1 |

0.6 |

|

B4 |

supported by UN |

0 |

2 |

0.5 |

|

D1 |

supported by government contributions |

0 |

4 |

0.7 |

|

B3 |

allies closely with government |

-1 |

5 |

0.9 |

|

D2 |

supported by citizens paying low fee for service |

-1 |

0 |

0.8 |

|

A4 |

serves as test location for new medical development |

-2 |

-2 |

0.7 |

|

D4 |

supported by public appeals |

-2 |

3 |

1.3 |

|

D3 |

allow researchers to work and help support |

-4 |

4 |

1.1 |

|

C2 |

fly students around the world for training |

-7 |

1 |

1.2 |

When we look at the 16 individual coefficients, we find that there are no elements which strongly drive the Positive-Outcome. For the Negative-Outcome, only two elements really drive additional negativity:

allies closely with community

allies closely with government.

When we look at response time, we do not use an additive constant. The response time does not measure positive or negative, but rather engagement, i.e., time to read and digest the information. The longest response time was 1.3 seconds, supported by public appeals.

Interactions Between ‘Objective Of The Organization’ And Other Elements – Scenario Analysis

The permutation scheme created a large number of different vignettes, with only a few vignettes duplicated. A benefit of this strategy is the ability to uncover interactions between pairs of elements and show how some combinations generate coefficients far higher or far lower than would be expected from looking simply at the performance of the single elements.

Our focus is on how way the different ‘goals of the school’ (answers to question A) ‘interact’ with the remaining elements from the other questions. The process, known as ‘scenario analysis,’ follows these steps:

- Sort the data set into the five strata, i.e., sets of vignettes. These five strata are where there is no answer from Question A (goal of the organization), and then four remaining strata where the answer appearing in the vignette is A1, A2, A3, and A4, respectively.

- Run a separate regression analysis on each stratum.

- The independent variables for each of the five new regression analyses are now the 12 remaining elements or answers, (B1-B4; C1-C4; D1-D4). The variables A1-A4 do not appear in the regression model because they are constant for each regression analysis, and thus are not predictors.

- The actual analysis is straightforward and shown in Table 4 when the dependent variable is ‘Positive-Outcome,’ Table 5 when the dependent variable is ‘Negative-Outcome,’ and Table 6 when the dependent variable is Response Time. The very strong performing elements are shown by shaded cells, with coefficient values in bold type.

- Positive-Outcome: Table 4 shows pairs of elements where the stated goal or objective for the school either strongly increases the coefficient of the element (synergism) or strongly suppresses the coefficient of the element (suppression).

- An example of synergism is the combination of ‘provides local training in homes,’ element C1. In the absence of any objective stated, it generates a coefficient of +7. When combined with the objective ‘to teach’ the coefficient for ‘provides local training in homes’ jumps to +15.

Table 4: Scenario analysis – How the different objectives of the nursing school synergize with other elements to drive the prediction that the outcome will be positive. Only combinations with strong synergism or suppression are shown.

|

|

Positive-Outcome |

None |

to teach |

to prepare |

improve local health |

serves as test location for new medical development |

|

|

|

A0 |

A1 |

A2 |

A3 |

A4 |

|

|

Additive constant |

18 |

49 |

28 |

38 |

53 |

|

C3 |

places students in local doctor’s offices |

23 |

-13 |

20 |

-11 |

-8 |

|

D4 |

supported by public appeals |

14 |

-12 |

-6 |

7 |

-8 |

|

C1 |

provides local training in homes |

7 |

15 |

7 |

8 |

-16 |

|

B2 |

allies closely with local community |

-3 |

-3 |

1 |

9 |

-3 |

|

D2 |

supported by citizens paying low fee for service |

-5 |

-14 |

12 |

9 |

-6 |

Table 5: Subgroup models relating the presence/absence of elements to Positive-Outcome.

|

|

|

Total |

Male |

Female |

Age 15–24 |

Age 25–40 |

Age 41+ |

|

|

Additive constant – Positive Outcome |

38 |

27 |

48 |

45 |

31 |

43 |

|

A1 |

to teach |

3 |

-2 |

7 |

-3 |

10 |

-2 |

|

A2 |

to prepare |

2 |

-2 |

5 |

-12 |

13 |

-2 |

|

C4 |

brings nurses to local community centers |

2 |

10 |

-5 |

1 |

5 |

-2 |

|

C3 |

places students in local doctor’s offices |

1 |

3 |

-1 |

-7 |

-1 |

8 |

|

B2 |

allies closely with local community |

1 |

13 |

-8 |

11 |

-5 |

0 |

|

A3 |

improve local health |

0 |

-6 |

4 |

-6 |

8 |

-6 |

|

|

Additive constant – Negative Outcome |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

16 |

26 |

9 |

27 |

9 |

18 |

|

|

B1 |

supported and promoted by local hospitals |

1 |

-5 |

6 |

-4 |

8 |

3 |

|

B2 |

allies closely with local community |

5 |

-2 |

10 |

0 |

12 |

0 |

|

B3 |

allies closely with government |

5 |

-5 |

13 |

1 |

7 |

8 |

|

D3 |

allow researchers to work and help support |

4 |

-1 |

8 |

1 |

4 |

6 |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Response Time |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

D4 |

supported by public appeals |

1.3 |

1.2 |

1.3 |

1.1 |

1.1 |

1.8 |

|

C1 |

provides local training in homes |

1.2 |

0.9 |

1.5 |

0.4 |

0.8 |

2.3 |

|

C2 |

fly students around the world for training |

1.2 |

1.0 |

1.5 |

0.9 |

0.9 |

1.9 |

|

D3 |

allow researchers to work and help support |

1.1 |

0.5 |

1.5 |

0.5 |

1.0 |

1.5 |

|

C3 |

places students in local doctor’s offices |

0.9 |

0.8 |

1.1 |

0.9 |

0.3 |

1.6 |

|

C4 |

brings nurses to local community centers |

0.9 |

0.9 |

1.0 |

0.9 |

0.3 |

1.6 |

|

B3 |

allies closely with government |

0.9 |

0.9 |

0.8 |

0.7 |

0.4 |

1.4 |

|

D2 |

supported by citizens paying low fee for service |

0.8 |

0.2 |

1.2 |

0.4 |

0.4 |

1.5 |

Key Subgroups

The ability to create models for each individual means that it is easy to create models for pre-defined subgroups. Tables 4–6 show parameters of the models for key subgroups, when the respondents fall into the pre-defined subgroups generated from the self-profiling classification. For this analysis we look at the gender and age, respectively. In the interest of space, we show only those elements which score well in at least one subgroup.

Table 6: The three mind-sets and their reaction to elements in terms of ratings of ‘Positive-Outcome.

|

|

Positive-Outcome |

MS1 |

MS2 |

MS3 |

|

|

Additive constant |

47 |

14 |

66 |

|

|

Mind-Set 1: Focuses on training venue |

|

|

|

|

C3 |

places students in local doctor’s offices |

10 |

4 |

-16 |

|

C1 |

provides local training in homes |

9 |

2 |

-10 |

|

A2 |

to prepare |

8 |

1 |

-5 |

|

|

Mind-Set 2: Focus on practicality of support |

|

|

|

|

B4 |

supported by UN |

-2 |

17 |

-21 |

|

D1 |

supported by government contributions |

-18 |

15 |

-6 |

|

B1 |

supported and promoted by local hospitals |

-8 |

14 |

-12 |

|

D3 |

allow researchers to work and help support |

-17 |

14 |

-14 |

|

B2 |

allies closely with local community |

-7 |

13 |

-8 |

|

D4 |

supported by public appeals |

-21 |

8 |

3 |

|

|

Mind-set 3 – Basically positive but can be ‘spooked’ |

|

|

|

|

|

No element drives a strong positive response beyond the additive constant (baseline) |

|

|

|

|

|

Not a strong driver of any mind-set |

|

|

|

|

A4 |

serves as test location for new medical development |

4 |

-12 |

5 |

|

D2 |

supported by citizens paying low fee for service |

-19 |

7 |

4 |

|

A1 |

to teach |

7 |

1 |

-2 |

|

C4 |

brings nurses to local community centers |

6 |

0 |

-2 |

|

A3 |

improve local health |

5 |

-3 |

-2 |

|

C2 |

fly students around the world for training |

-7 |

-7 |

-14 |

|

B3 |

allies closely with government |

2 |

6 |

-16 |

Table 5 (top panel) shows the parameters of the models created for the subgroup when the dependent variable was chosen to be Positive-Outcome. The additive constant provides us with a with a baseline of expected Positive-Outcome in the absence of elements. For the total panel the additive constant is 38, but much higher for females (constant = 48), for younger respondents (age 15–24, constant = 45) and for the oldest respondents (age 41+, constant = 41+). If we were to hazard a rationale for the results it would be that females are basically more interested in the nursing school, as are those contemplating but not yet ready (age 15–24) and those who have made a career decision (age 41+.) Males are less interested, confirming the literature report that there is a dearth of males in professional nursing.

Table 5 (Middle panel) shows the parameters of the models for the subgroups when the dependent variable was chosen to be Negative-Outcome. The additive constants are all low. The highest additive constants are from males (constant = 26) and from age 15–24 (additive constant = 27.) Across the subgroups the key elements driving a predicted Negative-Outcome tends to be ‘allies closely with government,’ and ‘allies with the local community.”

Table 5 (bottom panel) shows the coefficients for the response time model by key subgroups. the longest response times are shaded. The data suggest that the oldest respondents take the longest to process the information. This tends to be a general pattern. It is not clear whether this longer time is because the older respondents take longer to read, longer to comprehend, or longer to respond, or any combination thereof.

Mind Sets

People can be divided by who they ARE, by what they DO, or by their BELIEFS. These ways of dividing people put people into complementary groups with the hope that people in the different groups will think ‘similarly’ about a specific topic. Once groups of people are discovered who ‘think alike,’ they can be efficiently targeted with messages engineered to appeal to them. Conventional research easily creates these clusters of individuals, these segments, based on situational data, behavioral data, or even responses to general questionnaires about a topic. The segments which emerge from these conventional methods are coherent, but only coherent with respect to the measures from which the clusters or segments were derived. People in the same behavioral segment behave similarly on the measures used. People in the same attitudinal or so-called psychographic segment, respond similarly to the general questions [31].

There is a fundamental flaw in most of the segmentation scheme in use today, namely the failure of the ‘top down segmentation’ to be specific and prescriptive at the level of action. The problem of top-down segmentation, dividing people on the basis of general patterns, is the problem of granularity, or more properly the inability of the general segmentation to deal with the granular application, the specific need. When we assume that people in attitudinal or psychographics respond ‘similarly,’ we are dealing with general responses. They may respond quite differently when the topic is far more specific, more granular, and far less general. With the data we have here, a two people might be in the same general segment for education yet respond quite differently when we deal with granular topic of nursing education.

Mind Genomics works at the level of the granular, where everyday life is lived. Rather than looking for these large segments, Mind Genomics operates at the level of specifics, granularity, at the level of the actual questions and answer for the topic. Mind Genomics works from the bottom up, in the manner of a pointillist artist, focusing on the segments which can be uncovered from the granular, individual-level data of a specific project.

The process to discover these Mind-Sets in the population is again quite straightforward, driven by a combination of statistical methods which are ‘objective,’ and interpretation, which is ‘subjective’. The method creates an individual-level model for each respondent, and clusters the models using cluster analysis [32] The results comprise a small number of groups, the so-called clusters, with the property that the patterns of coefficients within a cluster are all similar, whereas the pattern of averages of the coefficients differs dramatically from cluster to cluster. In simple terms, a cluster represents a group of like-minded individuals, based upon the pattern of their coefficients. The individuals are like-minded only with respect to the top of the nursing school. That is the clustering is based upon granular thinking of a specific topic.

The subjectivity of clustering comes when the researcher must decide how many clusters to select, and what to name the clusters for future work. The decision is based upon searching for the smallest number of clusters (parsimony), but with each cluster ‘telling a story’ based upon the pattern of its 16 coefficients (interpretability). These clusters become Mind-Sets in the terminology of Mind Genomics, namely groups which ‘think alike’ in the granular topic of this ‘nursing school.’

The clustering was based on the pattern of coefficients for Positive-Outcome. Once the clusters or mind-sets are established, we can look at the elements which drive Positive-Outcome, as well as Negative-Outcome and Response Time. Tables 6–8 show these three mind-sets, and the elements which drive the three dependent variables, respectively.

Table 7: The three mind-sets and their reaction to elements in terms of ratings of ‘Negative-Outcome.’ The table shows only the elements which drive a strong estimate of ‘Negative-Outcome’ for at least one of the three mind-sets.

|

|

Negative-Outcome |

MS1 |

MS2 |

MS3 |

|

|

Additive constant |

10 |

22 |

15 |

|

|

Mind-Set 1: Focuses on training venue |

|

|

|

|

D3 |

allow researchers to work and help support |

14 |

-4 |

4 |

|

|

Mind-Set 2: Focus on practicality of support |

|

|

|

|

|

No element drives a strong negative response beyond the additive constant (baseline) |

|

|

|

|

|

Mind-set 3 – Basically positive but can be ‘spooked’ |

|

|

|

|

B3 |

allies closely with government |

7 |

-3 |

15 |

|

B4 |

supported by UN |

2 |

-4 |

9 |

|

B1 |

supported and promoted by local hospitals |

3 |

-6 |

8 |

Table 8: The three mind-sets and their reaction to elements in terms of Response Time. The table shows only those elements which generate a long response time (>1.4 seconds) for at least one mind-set.

|

|

Response time |

MS1 |

MS2 |

MS3 |

|

|

Mind-Set 1: Focuses on training venue |

|

|

|

|

D3 |

allow researchers to work and help support |

1.5 |

0.4 |

1.6 |

|

C2 |

fly students around the world for training |

1.4 |

1.5 |

0.8 |

|

|

Mind-Set 2: Focuses on practicality of support |

|

|

|

|

C1 |

provides local training in homes |

1.2 |

1.5 |

1.0 |

|

D4 |

supported by public appeals |

1.2 |

1.3 |

1.4 |

|

C4 |

brings nurses to local community centers |

0.8 |

1.3 |

0.7 |

|

|

Mind-set 3 – Basically positive but can be ‘spooked’ |

|

|

|

|

|

allow researchers to work and help support |

1.5 |

0.4 |

1.6 |

|

|

supported by public appeals |

1.2 |

1.3 |

1.4 |

Finding Mind-Sets In the Population

Mind Genomics usually uncovers the different minds in the population. The mind-sets emerge clearly because the input material underlaying the mind-sets are phrases which are ‘cognitively meaningful and rich.’ What does not emerge so quickly is a way to discover these mind-sets in the population. The mind-sets do not distribute by the conventional ways of dividing people, as Table 9 shows, for the distribution of mind-sets by gender and by age, respectively. Even psychographic divisions of people, such as their interest in education and so forth, often do not co-vary with the mind-sets. The mind-sets exist, but it is difficult to assign a new person to the proper mind-set unless the person participates in the research.

Table 9: Distribution of mind-sets by gender and age.

|

|

Total |

Mind-Set 1: Focuses on training venue |

Mind-Set 2: Focuses on practicality of support |

Mind-set 3: Basically positive, but can be ‘spooked’ |

|

Total |

40 |

12 |

16 |

12 |

|

Male |

18 |

4 |

10 |

4 |

|

Female |

22 |

8 |

6 |

8 |

|

Age 15–24 |

10 |

3 |

3 |

4 |

|

Age 25–34 |

16 |

7 |

5 |

4 |

|

Age 41+ |

14 |

2 |

8 |

4 |

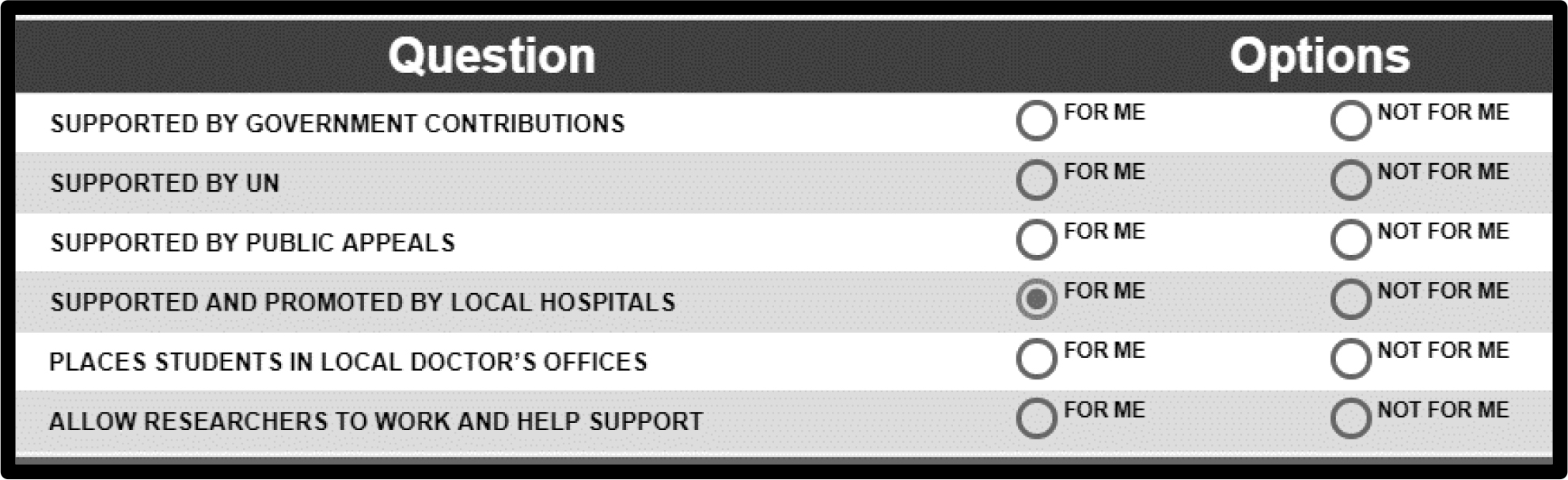

Recently, author Gere has developed a set of algorithms using Monte Carlo simulations, in order to create a set ‘questions’ based on the elements. The pattern of answers to these questions allow the new person to be assigned to the most likely mind-set. The method is called the PVI, the personal viewpoint identifier. It is based on a Monte Carlo simulation, in which the likely pattern of responses to six questions created from six of the elements co-varies with membership in each of the three mind-sets. Figure 4 shows the six questions and the two answers to each question. There are 64 patterns based upon six questions and two answers. Each pattern is most likely with one of the two mind-sets. When a respondent generates a pattern by answering the question the most likely mind-set associated with that pattern becomes the mind-set to which the new person is assigned.

Figure 4. The six question PVI (Personal Viewpoint Identifier) for this study.

Discussion and Conclusions

The traditional topics of curriculum, approaches, and values have been left to the professionals in the field. The role of the ordinary person has generally been to get support for nursing schools (and indeed other types of schools), to fund schools and their programs, and then to quietly hand over the reins of control to professionals. The professional literature is replete with the points of view of professionals about what the curriculum should be, how the student should be taught, and trained to be ready to deliver nursing-care. The general public is often excluded from these discussions. Often, however, it is the general public, or at least those who RECEIVE nursing-care who are the ones able to add most to what is missing. Those involved in teaching, in the world of purveying knowledge, may not realize the changes occurring in their own field and the public expectations from Nursing. Up to now, Nursing has been considered a ‘weak signal,’ rather than the emerging need it really is, to increase patient trust, patient-adherence, patient experiences and patient resilience [33, 34].

Across mind-set segments, the public expects Nursing programs to better prepare nurses by enhancing their professionalism through exposure to more medical settings, as they encounter their clinical practice. For example, the data from the public, non-nursing world, suggests that nursing students should receive clinical practice at doctors’ offices, at local community health centers and at patients’ homes, each beyond the traditional hospital settings. The public also expects local community hospitals to support training of nursing students. Furthermore, the public expects nursing programs to allow researchers to support training and professionalism. Future studies may test the effect of interventions to adopt the above recommendations on the tensions nursing students experience as they complete their professional education.

Postscript Mind Genomics Research as the Public’s Input and Guide for Educational Institutions

There is an emerging recognition that the fast-changing world of today requires different modalities for learning. Emblemizing this change in the world of textbooks, as an example. The era of heavy, expensive textbooks has gone, or is in the process of departing. These traditional textbooks enjoying two, three, four or more editions, provided a standardized body of knowledge updated regularly. The demands for knowledge are changing, forcing many schools to create their own unique ‘textbooks’ by cobbling together papers available on the Internet, and in the university’s own private collection. The need for creative thinking to develop professional schools for ‘today’ is beginning to be recognized. When we look at the data presented here, the requirements for a nursing school, not from the point of view of the teaching profession but from the point of view of the public, we see these results in a different light.

Acknowledgment

Attila Gere wishes to acknowledge the Premier Post-Doctoral Research Program of the Hungarian Academy of Sciences.

References

- Allen-Johnson A (2017) Framework for 21st century school nursing practice: Framing professional development. NASN School Nurse 32: 159–161.

- Cogan RM, Conway SM, Atkins JD (2017) Redesigning school nursing education in New Jersey to address the challenges and opportunities of population health. NASN School Nurse 32: 83–86.

- Andrew N (2012) Professional identity in nursing: are we there yet? Nurse Education Today 32: 846–849.

- National Association of School Nurses (2016) Framework for 21st century school nursing practice: National Association of School Nurses. NASN School Nurse 31: 45–53.

- Traynor M and Buus N (2016) Professional identity in nursing: UK students’ explanations for poor standards of care. Social Science & Medicine 166: 186–194.

- Frost HD and Regehr G (2013) “I am a doctor”: negotiating the discourses of standardization and diversity in professional identity construction. Academic Medicine 88: 1570–1577.

- Curtis K, Horton K, Smith P (2012) Student nurse socialisation in compassionate practice: A Grounded Theory study. Nurse Education Today 32: 790–795.

- Mackintosh C (2006) Caring: The socialisation of pre-registration student nurses: A longitudinal qualitative descriptive study. International Journal of Nursing Studies 43: 953–962.

- Apker J, Propp KM, Ford WSZ, Hofmeister N (2006) Collaboration, credibility, compassion, and coordination: professional nurse communication skill sets in health care team interactions. Journal of professional nursing 22: 180–189.

- Ozcan CT, Oflaz F, Bakir B (2012) The effect of a structured empathy course on the students of a medical and a nursing school. International nursing review 59: 532–538.

- Leiter MP, Jackson NJ, Shaughnessy K (2009) Contrasting burnout, turnover intention, control, value congruence and knowledge sharing between Baby Boomers and Generation X. Journal of Nursing Management 17:100–109.

- Maben J, Latter S, Clark JM (2007) The sustainability of ideals, values and the nursing mandate: evidence from a longitudinal qualitative study. Nursing Inquiry 14: 99–113.

- Williams LB, Bourgault AB, Valenti M, Howie M, Mathur S (2018) Predictors of underrepresented nursing students’ school satisfaction, success, and future education intent. Journal of Nursing Education 57: 142–149.

- Delamothe T (2011) We need to talk about nursing. British Medical Journal M.J 342: 3416 London.

- Francis R (2013) (a). Report of the Mid Staffordshire NHS Foundation Trust Public Inquiry: Executive summary. London: House of Commons.

- Francis R (2013) (b). Report of the Mid Staffordshire NHS Foundation Trust Public Inquiry: Volume III Present and Future Annexes. London: House of Commons.

- Box GE, Hunter WG, Hunter JS (1978) Statistics for experimenters, New York, John Wiley.

- Luce RD, Turkey JW (1964) Simultaneous conjoint measurement: A new type of fundamental measurement. Journal of mathematical psychology 1: 1–27.

- Green PE, Rao VR (1971) Conjoint measurement for quantifying judgmental data. Journal of marketing research 8: 355–363.

- Green PE, Srinivasan V (1990) Conjoint analysis in marketing: new developments with implications for research and practice. The journal of marketing 54: 3–19.

- Stevens SS (1975) Psychophysics: An Introduction to its Perceptual, Neural and Social Prospects, New York, John Wiley.

- Moskowitz HR, Gofman A, Beckley J, Ashman H (2006) Founding a new science: Mind genomics. Journal of sensory studies 21: 266–307.

- Moskowitz HR and Gofman A (2007) Selling blue elephants: How to make great products that people want before they even know they want them. Pearson Education.

- Gofman A and Moskowitz H (2010) Isomorphic permuted experimental designs and their application in conjoint analysis. Journal of Sensory Studies 25: 127–145.

- Gabay G, Zemel G, Gere A, Zemel R, Papajorgji P, Moskowitz HR (2018) On the threshold: What concerns healthy people about the prospect of cancer? Cancer Studies and Therapeutics Journal 3: 1–10.

- Gabay G, Gere A, Stanley J, Habsburg-Lothringen C, Moskowitz HR (2019) (a). Health threats awareness – Responses to warning messages about cancer and smartphone Usage. Cancer Studies Therapy Journal 4: 1–10.

- Gabay G, Gere A, Zemel G, Moskowitz D, Shifron R, Moskowitz HR (2019) (b). Expectations and attitudes regarding chronic pain control: An exploration using Mind Genomics. Internal Medicine Research Open Journal 4: 1–10.

- Gabay G, Gere A, Moskowitz HR (2019) (c). Uncovering communication messages for health promotion: The case of arthritis. Integrated Journal of Orthopedic Traumatology 2: 1–13.

- Gabay G, Gere A, Moskowitz HR (2019) (d). Understanding effective web messaging – The Case of Menopause. Integrated Gynecology & Obstetrics Journal 2: 1–16.

- Gabay G, Gere A, Stanley J, Habsburg-Lothringen C, Moskowitz HR (2019) (e). Health threats awareness – Responses to warning messages about Cancer and smartphone usage. Cancer Studies Therapeutics Journal 4: 1–10.

- Weinstein A and Cahill DJ (2014) Lifestyle market segmentation. Routledge.

- Dubes RC and Jain AK (1988) Algorithms for clustering data. Prentice Hall.

- Gabay G (2019) Patient Self-worth and Communication Barriers to Trust of Israeli Patients in Acute-Care Physicians at Public General Hospitals. Qualitative health research Pg No. 1049732319844999.

- Gabay G (2019) A Nonheroic Cancer Narrative: Body Deterioration, Grief, Disenfranchised Grief, and Growth. OMEGA-Journal of Death and Dying Pg No. 0030222819852836