DOI: 10.31038/EDMJ.2019341

Summary

Objective: To determine the efficacy of sitagliptin alone or in combination with metformin in women with polycystic ovary in terms of ovarian cyclicity, fertility and cardio metabolic profile compared to metformin alone.

Rationale: Polycystic Ovarian Syndrome (PCOS) affects a percentage of 5–10% of women of reproductive age worldwide and has a prevalence of 6.6% (95% CI 2.3 to 10.9%). Mexican women and the most common cause of infertility in developed countries.

It has been observed that treatment with insulin-sensitizing drugs (metformin and pioglitazone) improve menstrual cyclicity and fertility in the metabolic profile with polycystic ovary patients. Incretins and DPP-4 inhibitors have been shown to improve the activity of pancreatic β cell would increase weight loss by its anorectic effect and the existence of adequate weight control and improvement of fertility.

The previous tests have compared the effect of exenatide and alone or in combination with metformin in the treatment of PCOS, in this article we are going to compare sitagliptin and metformin alone or in combination.

Study design: Blind, controlled and randomized clinical trial.

Patients: Women between 18 – 40 years of age, with a BMI> 20 and with diagnosis of PCOS with the Rotterdam criteria.

Results: In the normalized menstruation index it was found that there was a statistically significant intragroup increase in each of the treatments. The sitagliptin had a higher percentage of change with 127%, followed by that of metformin with 87.5% and then the COMBO with 60%. No statistically significant differences were found between treatment groups.

Conclusion: The therapeutic effect of Sitagliptin was observed in patients with PCOS comparable to metformin and the combination of metformin-sitagliptin is more effective in terms of ovulation than the other two treatments alone

Keywords

Polycystic Ovarian Syndrome, Diabetes Mellitus, Prediabetes, Insulin Resistance

Background

Polycystic Ovarian Syndrome is a syndrome of ovarian dysfunction whose main characteristics are hyperandrogenism, hyperandrogenemia and the presence of polycystic ovaries. This syndrome affects a percentage of between 5 to 10% of women of reproductive age [1]; however, in Mexican-American women a prevalence of 12.8% has been reported. In 2010, Moran et al. They conducted a prospective cross-sectional study in 150 Mexican women to determine the prevalence of PCOS in this population. By Rotterdam criteria, a prevalence of 6.6% was found (95% CI: 2.3–10.9%) [2–4].

Its etiology remains unknown and is the most common cause of infertility in developed countries [1]. Polycystic Ovarian Syndrome is associated with important metabolic alterations. The prevalence of Diabetes Mellitus 2 is 10 times higher in women with PCOS than among women without this entity. An alteration in glucose tolerance or the development of Diabetes Mellitus 2 is found in 30 to 50% of women over 30 years of age obese with PCOS, so screening for glucose intolerance has been recommended in women with PCOS [3]. The prevalence of metabolic syndrome is 2 to 3 times higher among women with PCOS than among women without this entity and 20% of women with PCOS less than 20 years of age have metabolic syndrome [1]. There is also a significant risk among patients with PCOS of developing Gestational Diabetes [5].

A significant number of patients with PCOS are overweight and many are obese; however, obesity is not considered as a cause for the development of this syndrome [6].

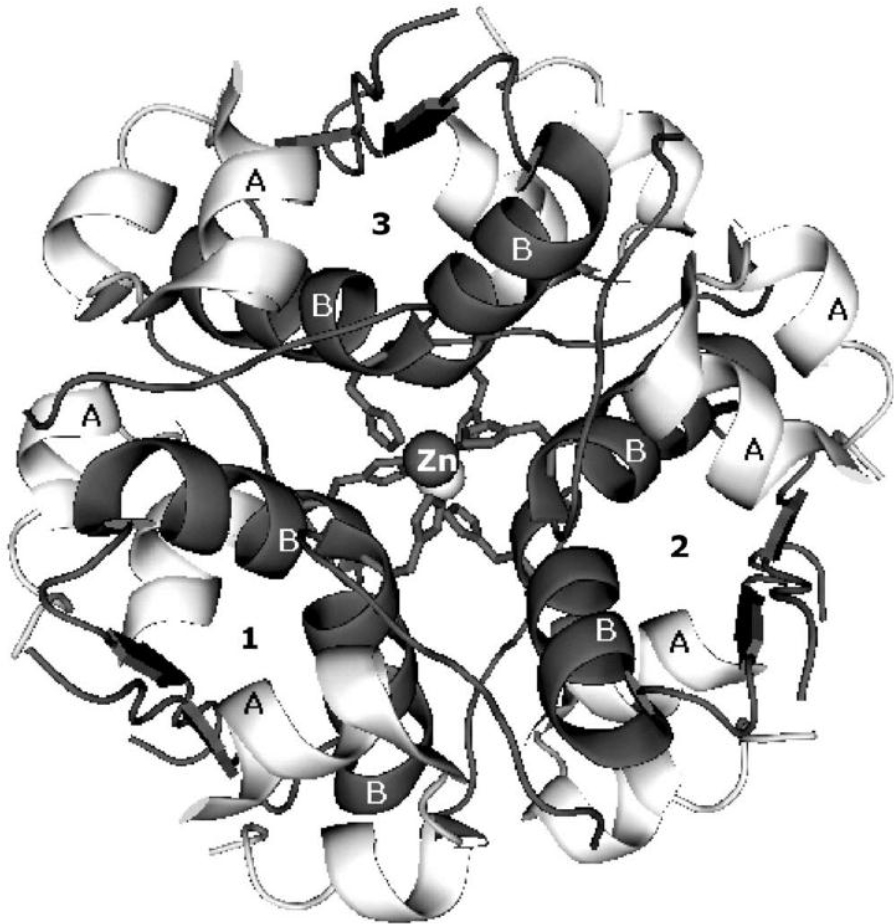

Regarding Pathophysiology in studies, it is suggested that teak cells in women with Polycystic Ovarian Syndrome are more efficient in the conversion of androgenic precursors to testosterone than teak cells in normal women. The concentration of LH has a relative increase over FSH and the ovaries preferentially synthesize androgens. An increase in the frequency of the pulses of the Gonadotropin Releasing Hormone (GnRH) was observed. The increase in the frequency of GnRH pulses favors transcription of the Beta subunit of LH over the Beta subunit of FSH [5].

The role of insulin in the pathophysiology of PCOS is very important because it acts in synergy with LH to increase the synthesis of androgens in the cells of teak and the ovaries of women with PCOS seem to have greater sensitivity to the effect of insulin, perhaps hypersensitivity to it, even when the classic white organs of insulin, such as muscle and fat, show resistance to its action [6–8].

Insulin prevents ovulation both by direct affection of follicular development and by the indirect increase of intra-ovarian androgen levels or alteration of gonadotropin secretion. A decrease in circulating insulin levels results in an increase in the frequency of ovulation or menstruation, reduction of testosterone concentrations or both [1].

Metformin is the most widely used biguanide for the treatment of type 2 diabetes mellitus worldwide. Its most important action is the inhibition of hepatic glucose production but also increases the sensitivity of peripheral tissues to insulin. Increased insulin sensitivity, which contributes to the efficacy of metformin in the treatment of diabetes, has also been found in non-diabetic women with polycystic ovarian syndrome [1].

In women with PCOS, long-term treatment with metformin can increase ovulation, improve menstrual cyclicity and reduce androgen levels; the use of metformin can even improve hirsutism. However, it has not shown any risk modification to develop DM2 [1,9].

The results of a randomized clinical study reported in 1998, that pretreatment with metformin, compared with placebo, increased the incidence of ovulation after a subsequent treatment with clomiphene. The meta-analysis of Lord and cols in 2002 included data from 13 trials and 543 women with PCOS and concluded that metformin is effective and increases the frequency of ovulation (odds ratio, 3.88, 95% confidence interval, 2.25 to 6.69) [9,10].

The signals derived from the intestine and stimulated by the intake of oral nutrients have an important role in the release of insulin. Studies suggest that glucagon-like peptide (GLP-1) and Glucose-Dependent Insulinotropic Polypeptide (GIP) represent the dominant peptides in most intestinal insulin-stimulating hormones. GIP and GLP-1 are members of the glucagon peptide superfamily and share amino acids [11].

Incretins increase insulin secretion in a glucose-dependent manner by activation of other specific β-cell receptors [11]. An intracerebroventricular injection of GLP-1, or GLP-1 receptor agonists, produces a reduction in food intake that is associated with weight loss in some but not in all studies [11].

There are other actions of GLP-1 on the β cell independent of the acute stimulation of insulin secretion. GLP-1R agonists (GLP-1 receptor) also promote insulin biosynthesis, proliferation of β-cells and stimulate exocrine or precursor cells towards greater differentiation to the β cell phenotype. The increase in the volume of the β cell dependent on GLP-1 receptors has been demonstrated in several experiments in animals. The expansion of the β cell after the administration of GLP-1R receptor agonists prevents or delays the incidence of Diabetes Mellitus in mice [12].

GLP-1 also activates anti-apoptotic pathways, leading to a reduction in β cell death. Studies in mice have shown a reduction in the activation of caspase 3. The antiapoptotic action of GLP-1R agonists is probably directed to the reduction of peroxide-induced apoptosis of Min6 cells [12].

Giovani Paacini et al. They carried out a study whose objective was the characterization of the secretion of GIP and GLP-1 after a load of 75 g of glucose in women with PCOS without glucose intolerance compared with healthy women. The concentrations of GLP1 were the same in the women with PCOS with respect to the control women in the initial phase of the tolerance curve until 60 minutes and were significantly lower in women with PCOS at 180 minutes of the curve [11].

In a study conducted by Pontikis et al. In 20 women with PCOS who underwent a glucose tolerance curve and isoglycemic test after a night of fasting in a two-week interval, they measured levels of insulin, glucose, C-peptide, GIP and GLP-1. Obese women with PCOS were found to have low levels of GIP concentrations in response to the glucose tolerance curve compared to the control group. Age, sensitivity to insulin (QUICKI), SHBG, and basal GIP did not differ between the control group and patients with PCOS. However, baseline GLP-1 was significantly lower in obese women with PCOS compared to both control groups (p 0.023) and in thin women (p <0.02). The group with PCOS showed a decrease in GIP levels after the glucose load compared to the control group [13,14].

A novel drug, exenatide, is an incretin mimetic that simulates the glucorregulatory properties of GLP-1 [12].

Exenatide therapy often results in a loss of weight which can result in a decrease in insulin resistance. The optimal treatment of PCOS should not only improve anovulation but should also reduce comorbidities such as obesity, insulin resistance and DM2, which are linked to this syndrome [11].

Exenatide, which is an analogue of incretin glp-1, apparently has beneficial effects on the β cell mass when given in pharmacological doses to rodents. The effect of DPP4 inhibitors on the mass of the β cell is less clear. In mice in which diabetes was induced and treated with sitagliptin, it was observed that this drug preserved the β cells of apoptosis but there was no increase in the β cell mass [6].

A study conducted by Elkind-Hirsch K. et al. In patients with Polycystic Ovarian Syndrome, overweight and with insulin resistance evaluated the treatment with exenatide and metformin in terms of menstrual cyclicity, hormonal parameters, metabolic profile and inflammatory markers. We included 60 overweight women (BMI> 27) and oligo-ovulation with PCOS, between 18 and 40 years of age [15].

The results of the study showed a statistically significant increase in menstrual frequency in all treatment groups (p 0,001). More regular menses were reported with combination therapy compared with single-drug therapy (p 0.018). Compared with the baseline, ovulation periods improved in all groups, with a significantly higher proportion with the combined therapy (p 0.01) [15].

The weight decreased significantly from the first to the last visit in all groups (p 0.001). The reduction in body weight was associated with an increase in menstrual frequency significantly (p <.006) [15].

HOMA-IR decreased significantly with all treatments (p 0.043). Similarly, insulin sensitivity, determined by IS OGTT, improved significantly with treatment (p <0.002). The improvement in sensitivity was significantly higher with combination therapy than with treatment with exenatide alone (p <0.02) but not compared with metformin (p <0.085) [16].

The most frequent adverse effects were gastrointestinal to medium to moderate, nausea was the most frequent adverse effect and was greater during combination therapy [15].

Sitagliptin is a molecule that belongs to the family of selective inhibitors of the enzyme Dipeptidyl Peptidase 4 (DDP-4) that normally degrades the endogenous incretins GIP and GLP-1 [16].

In humans, it has been observed that a daily dose of sitagliptin for 10 days resulted in a nearly double increase in GLP-1 after meals.

A study conducted by Kazutaka Aoki et al. It evaluated the effect of miglitol, sitagliptin and its combination on plasma concentrations of glucose, insulin and incretins in non-diabetic men. The results showed that insulin sensitivity among the group taking sitagliptin significantly improved, endogenous GIP and GLp1 concentrations increased and a statistically significant increase in pancreatic insulin secretion was observed [16].

A systematic review and meta-analysis of drugs belonging to DDP-4 showed that there is no risk of gastrointestinal adverse effects but there was an increased risk of urinary tract infections, headache and especially nasopharyngitis [16].

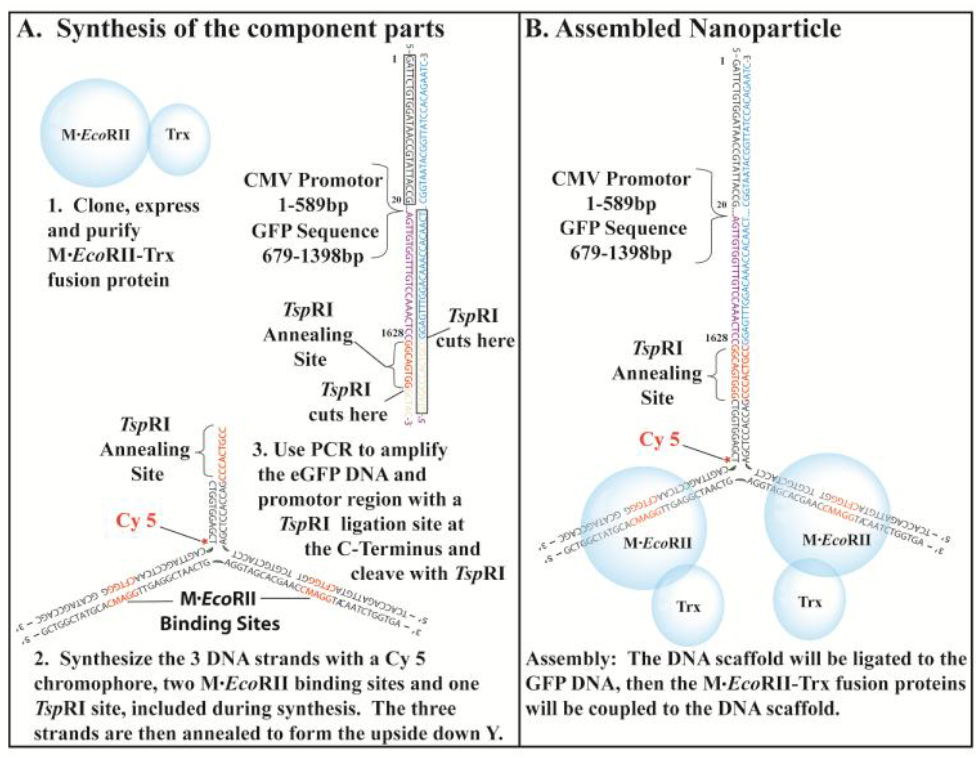

It has been observed that treatment with insulin-sensitizing drugs (metformin and pioglitazone) improves menstrual cyclicity, fertility and the metabolic profile in patients with polycystic ovary [17]. However, they have no effect on the activity of the beta cell and therefore on the progression to DM2 or Gestational Diabetes [18,19]. Incretins and DPP-4 inhibitors have been shown to improve the activity of the pancreatic β-cell, inhibit apoptosis, in addition to promoting weight loss due to its anorexigenic effect, thus providing an adequate control of weight and an improvement in fertility [17]. In addition, there was a deficit in the secretion and concentrations of GIP and GLP-1 in women with PCOS [13,14]. In a previous pilot study conducted by Paredes Palma JC et al. The statistically significant effect of sitagliptin on ovarian cyclicity was observed, increasing the normalized rate of menstruation by 60% and observing ovulation in terms of comparable progesterone secretion in women who were treated with Metformin [20]. This study carried out an extended study with a larger number of patients with PCOS to compare the use of Sitagliptin Vs Metformin Vs Metformin + Sitagliptin in patients with PCOS with a greater number of patients.

Hypothesis

Treatment with sitagliptin alone or in combination with metformin in women with polycystic ovary syndrome will be more efficient in terms of ovarian cyclicity, fertility and cardiometabolic profile compared to metformin alone.

Study Design

Blinding controlled and randomized clinical trial.

Objectives

- Evaluate the change in menstrual frequency with the use of sitagliptin and metformin, alone and in combination, in obese and nonobese women with polycystic ovarian syndrome and assess the effect on the hormonal, metabolic and inflammatory profile.

Primary Objective

- To evaluate the changes in the menstrual pattern of patients with thin and obese SOP with the use of sitagliptin and metformin, alone and in combination.

Secondary Objectives

- Evaluate changes in anthropometry (absolute weight, BMI, waist circumference, hip waist index).

- Evaluate changes in insulin sensitivity and secretion.

- Evaluate changes in the concentration of reproductive hormones (FSH, LH, PRL, testosterone, androstenedione, DHEA, DHEAS, 17 OHP4, TSH).

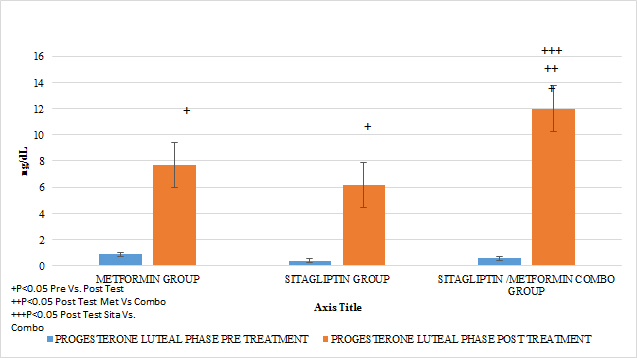

- Evaluate changes in ovulation rhythm (progesterone in luteal phase).

- Evaluate changes in the lipid profile (total cholesterol, HDL, LDL, VLDL, LDL, non-HDL cholesterol, triglycerides).

- Evaluate changes in inflammatory markers (C-reactive protein, VSG and adiponectin, IL6, SHBG).

Inclusion Criteria

- Age between18–40 years

- BMI> 20

- SOP diagnosis by Rotterdam criteria

Exclusion Criteria

- Women diagnosed with diabetes mellitus.

- Smokers

- Hormonal use in the 6 months prior to entering the study.

- Drugs that affect intestinal motility.

- Consumption of lipid-lowering drugs.

- Drugs that reduce weight in the last 3 months.

- Metformin intake in the last 6 months.

- No history of assisted fertilization treatment in the previous 6 months.

Elimination Criteria

Informed consent letter is not signed.

- There is no attachment to treatment.

- Do not attend scheduled appointments of pancreatic insulin secretion [16].

Description of the Experimental Maneuver

The participating patients were summoned every Friday from 8 am to 2 pm. The reason for the study, its advantages and disadvantages, was amply explained and the signing of an informed consent was submitted for consideration. To the patients who accepted to enter, clinical evaluation was applied (determination of menstrual pattern and application of the Ferriman Gallwey scale to determine the degree of hyperandrogenism), transvaginal USG and hormonal quantification were requested (LH, FSH, testosterone, androstenedione, dehydroepiandrosterone, prolactin, cortisol, ACTH, TSH, T4, T3) in order to identify patients who meet the Rotterdam criteria and exclude other diseases with a clinical picture similar to PCOS. Patients who were identified with PCOS were cited in the follicular phase of the menstrual cycle (from the 1st to the 5th day of menstruation), special mention are those patients who undergo amenorrhea who were cited from the 1st to the 5th day of bleeding after the application of 5 mg daily of medroxyprogesterone, at this time randomization was done to assign them to one of three groups:

- Group 1, Metformin with an initial dose of 425 mg VO before breakfast and before dinner until reaching a dose of 850 mg. every 12 hours.

- Group 2, Sitagliptin 100 mg vo. every 24 hours.

- Group 3, Sitagliptin plus Metformin in the doses described above.

Before the administration of the first dose, they were programmed for a glucose tolerance curve of 5 hours with 75 g. of glucose. In the first sample, 20 ml were obtained to quantify: lipid profile (total cholesterol, HDL, LDL, VLDL, LDL, non-HDL cholesterol triglycerides) and inflammation markers (C reactive protein, VSG and adiponectin, IL6, SHBG) taking counts the following times 0, 30, 60, 120, 180, 240 and 300 minutes. At each time 3 ml were taken to quantify glucose and insulin.

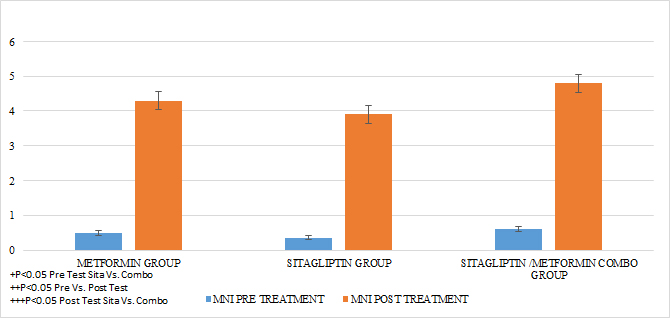

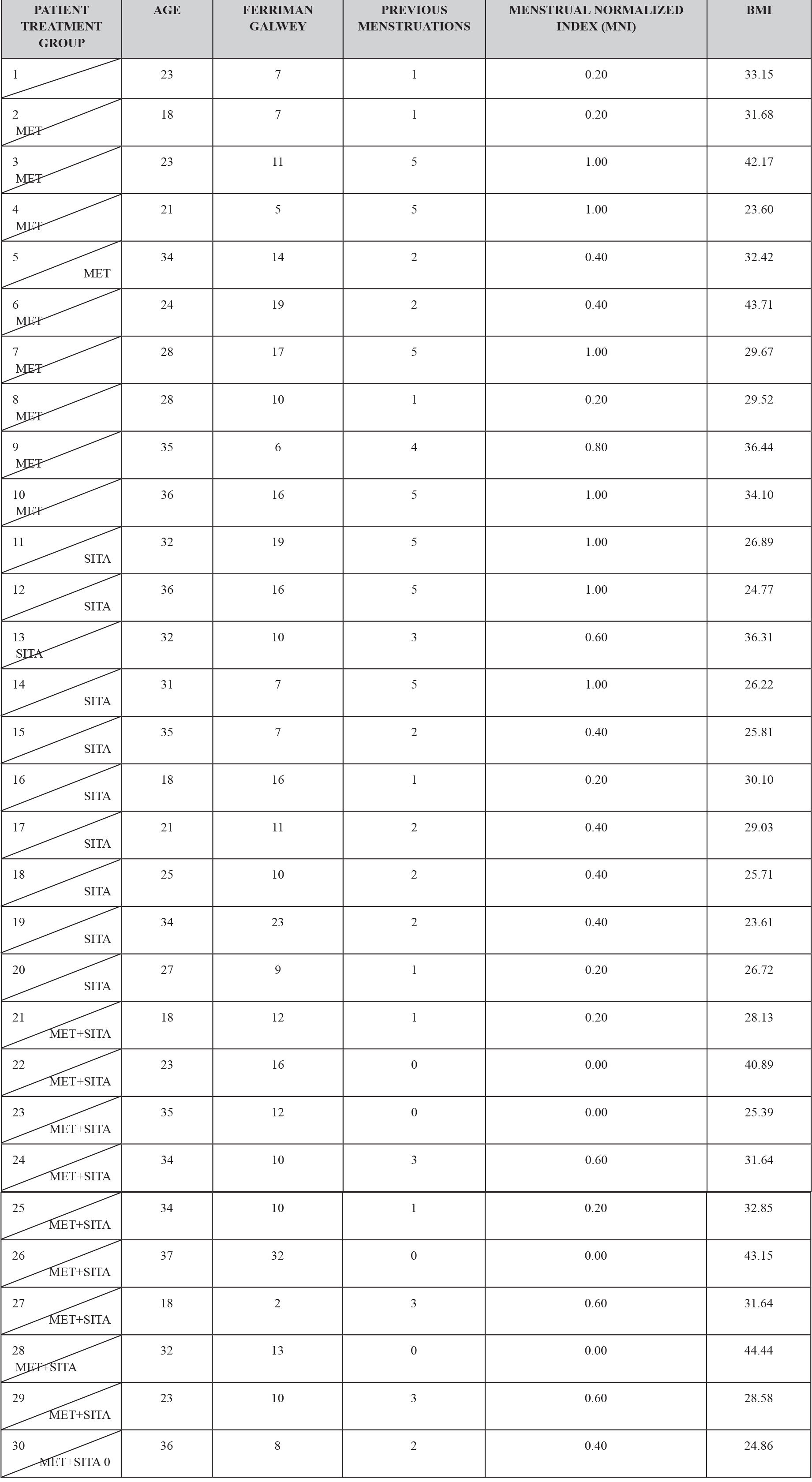

The same was done 24 weeks after the completion of the treatment according to the assigned group with only 24 hrs of suspension of the assigned medication. An individual with a normal menstrual pattern was considered if she presented 5 menses in 24 weeks of intervention with medications (Menstruation Normalization Index, INM) (FIGURE 1).

Statistical Analysis

It was performed for quantitative variables, average and standard deviation. For proportional variables, proportions were calculated. The quantitative variables were compared with a paired student’s T. For qualitative variables, chi square test was performed. A p less than 0.05 will be considered as statistical significance.

Results

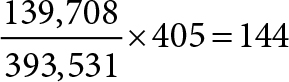

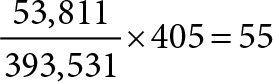

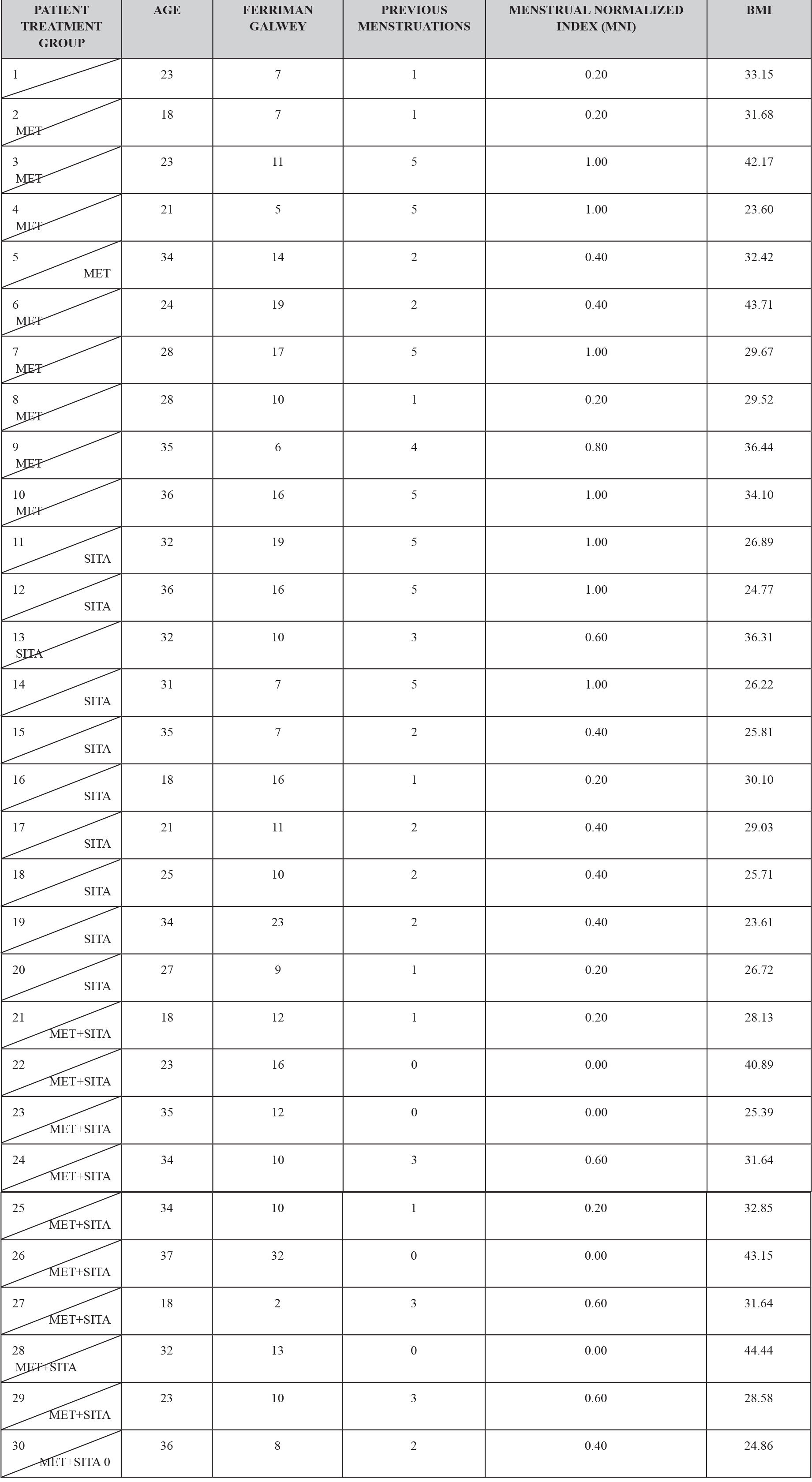

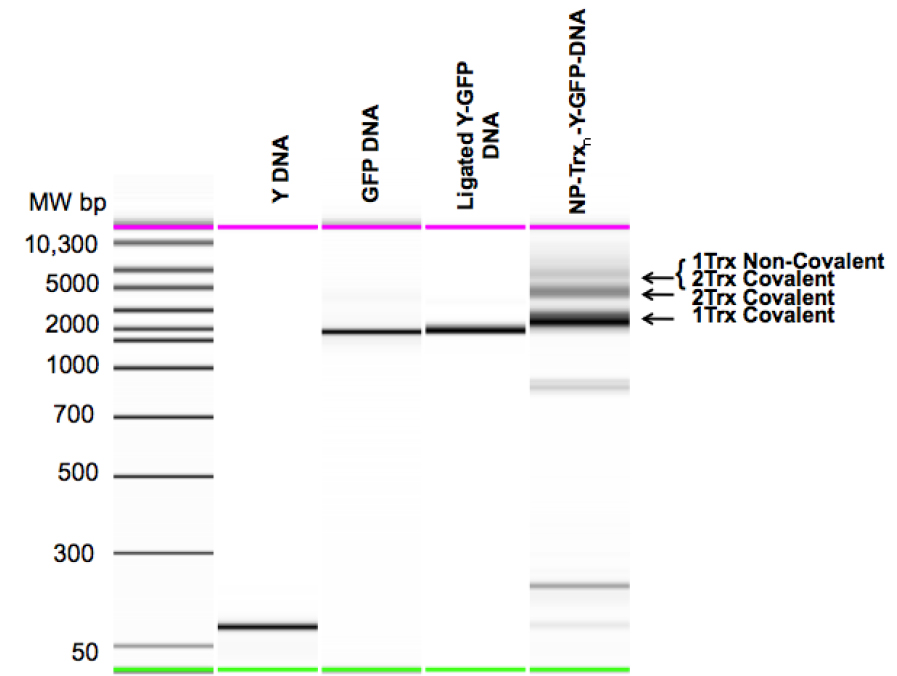

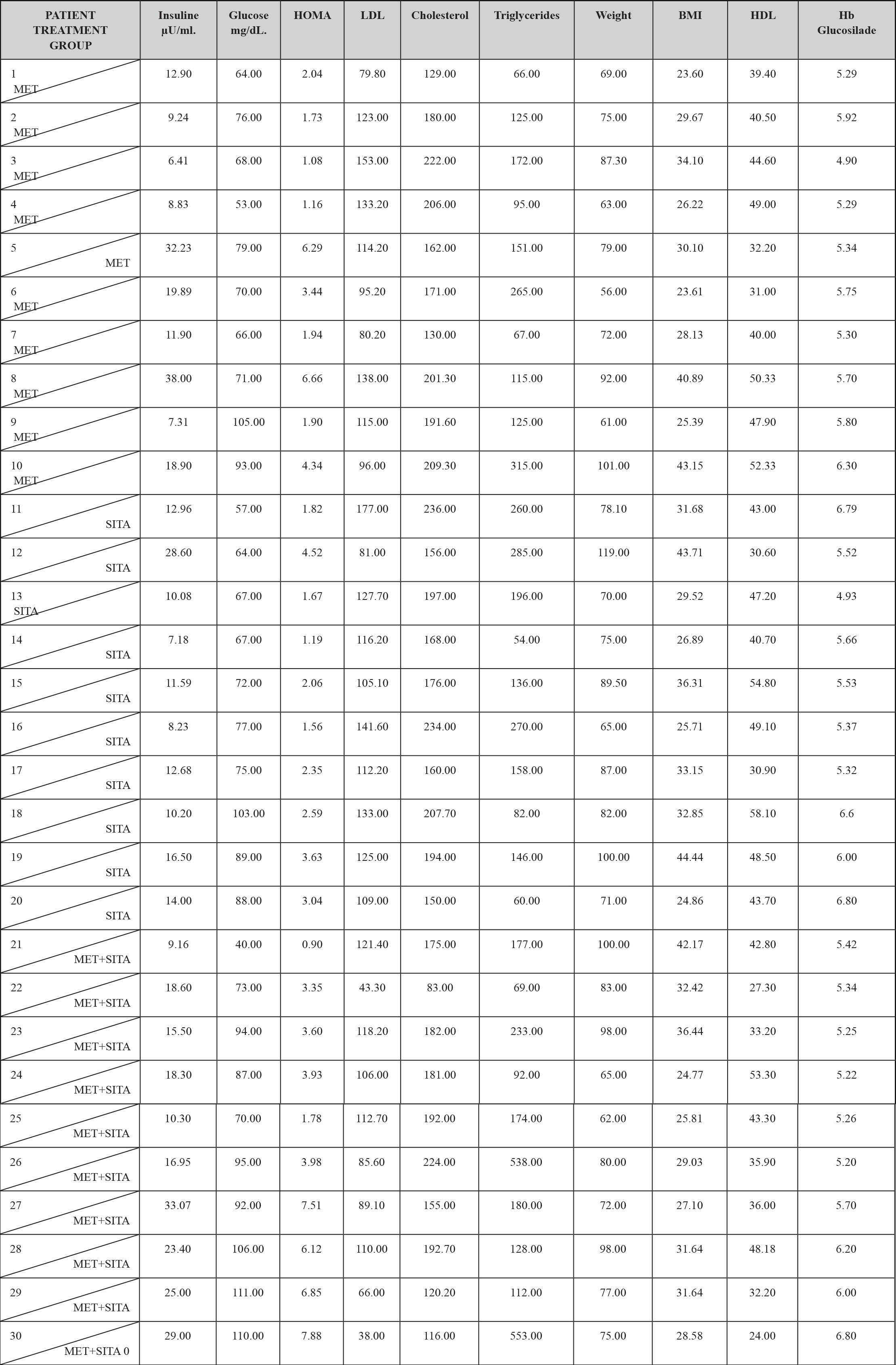

Thirty patients who were diagnosed with PCOS according to the Rotterdam criteria were included in this study, other causes of hyperandrogenism were ruled out. The patients presented clinical or biochemical signs of hyperandrogenism and 28 (93.3%) had ultrasound images compatible with polycystic ovaries. The age range was between 18 and 37 years old. Ten and nine patients (63.3%) presented menstrual alterations, 8 patients (26.6) presented opsomenorrhea and 11 (36.6%) amenorrhea. Regarding weight, 7 patients (2.3%) presented obesity grade I, 2 patients (0.6%) obesity grade II, 5 (1.6%) patients presented obesity grade III. Considering that in a time of 6 months it is normal to present 5 menstrual cycles, an index was created to normalize the number of menses per group according to their frequency. (Table 1).

TABLE 1. CLINICAL CHARACTERISTICS BY TREATMENT GROUP.

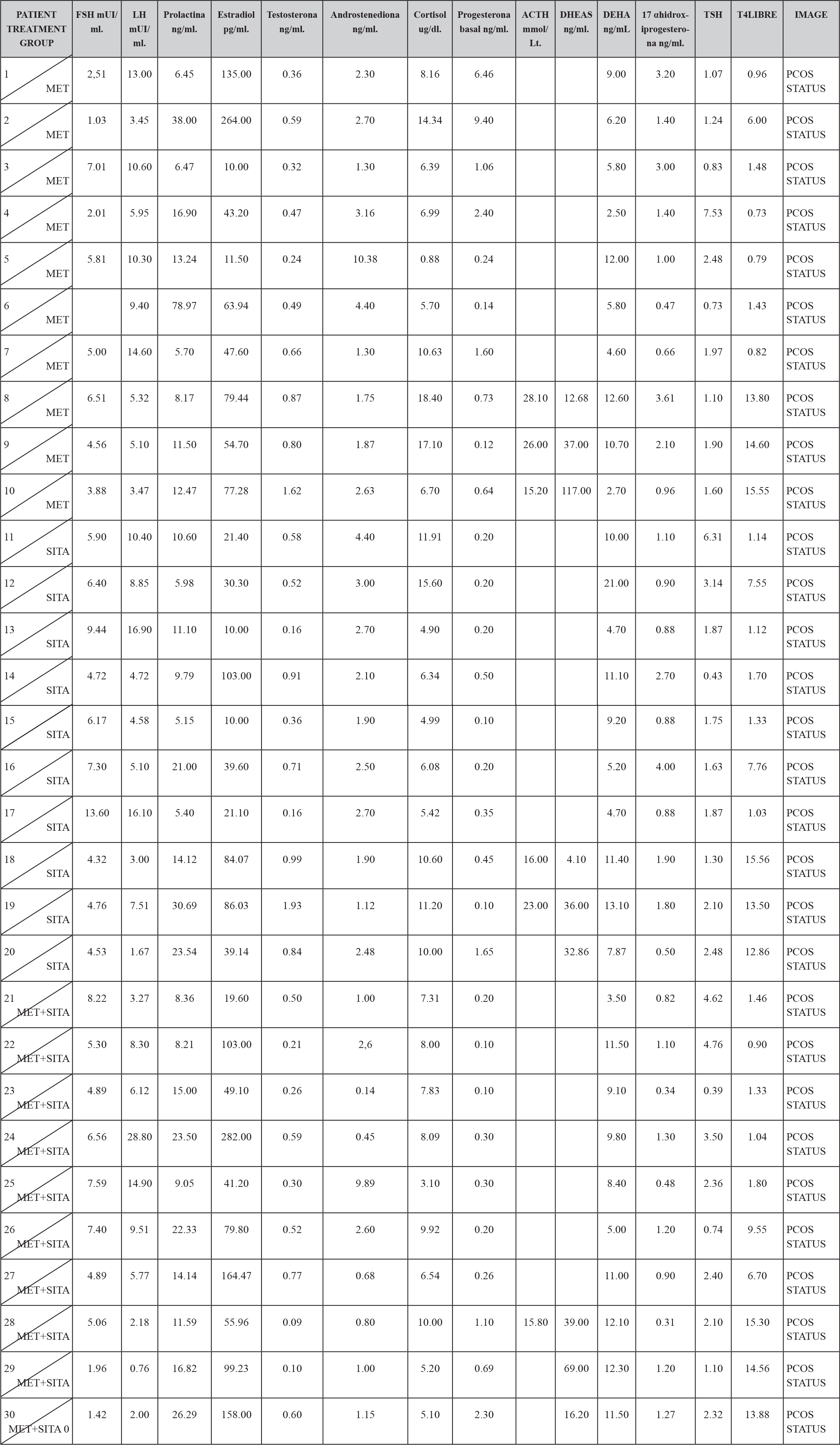

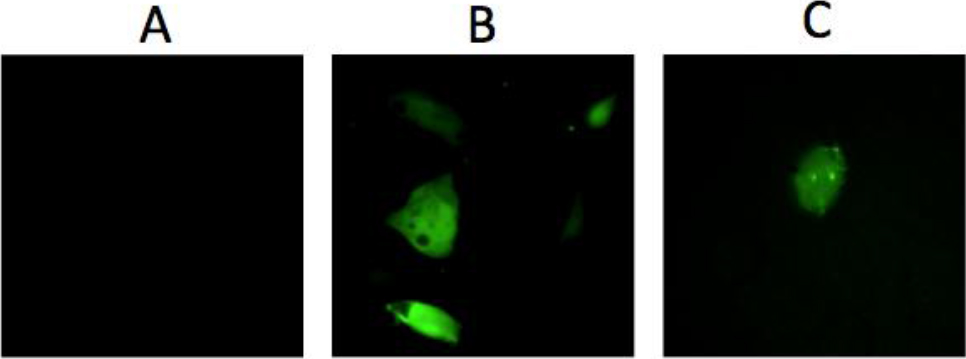

In the hormonal characteristics of the study patients it was observed that 12 patients (4%) presented the characteristic dissociation of LH and FSH and 2 patients (0.6%) presented testosterone concentrations compatible with androgen-producing ovarian tumor, which was discarded by ultrasonography, It is also to be noted that all the patients had a normal TSH concentration except two to which they were given the treatment and still continued with criteria to establish the diagnosis of PCOS; and all patients had a concentration of 17OHP4 (17 hydroxyprogesterone) below 4 ng / mL which is the cut-off point for suspecting 21-hydroxylase deficiency. (TABLE 2)

TABLE 2. BASAL HORMONAL CHARASTERISCTIC BY TREATMENT GROUP.

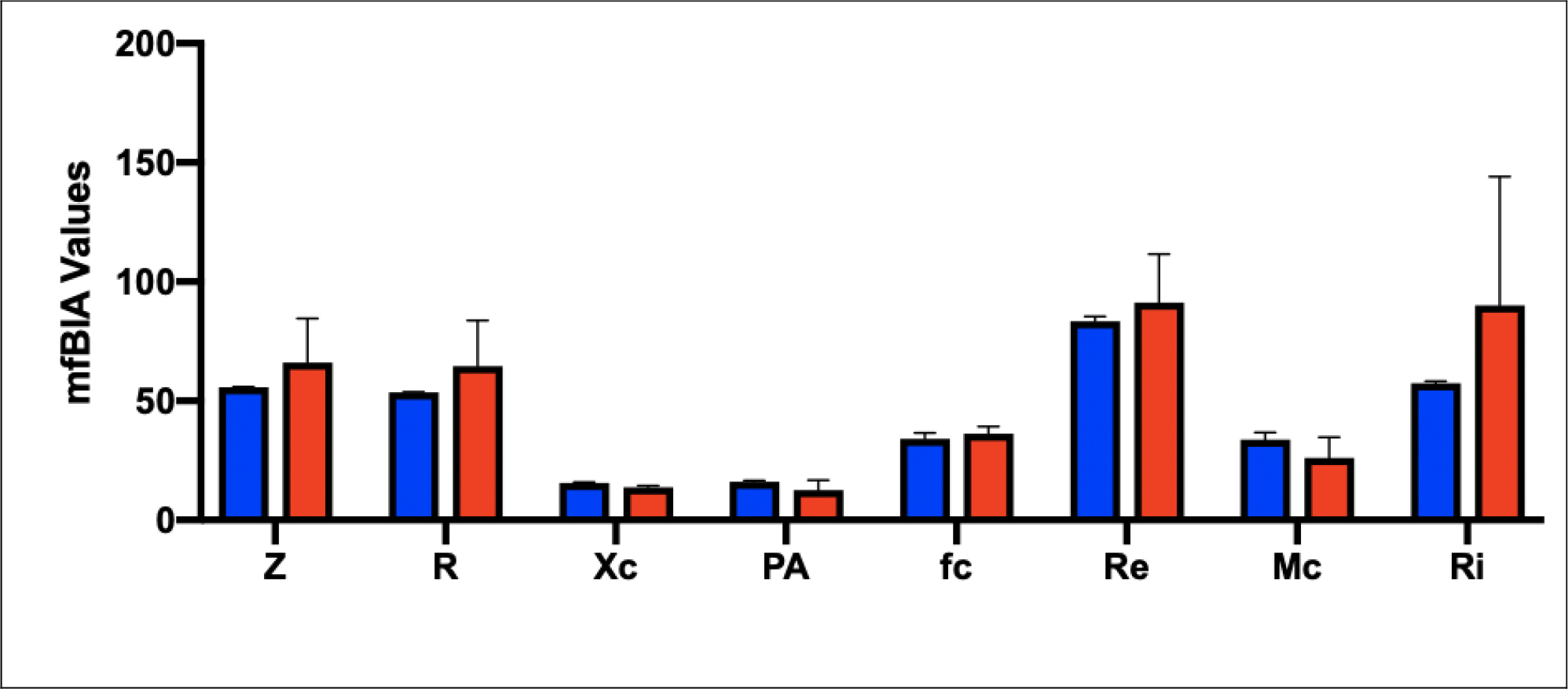

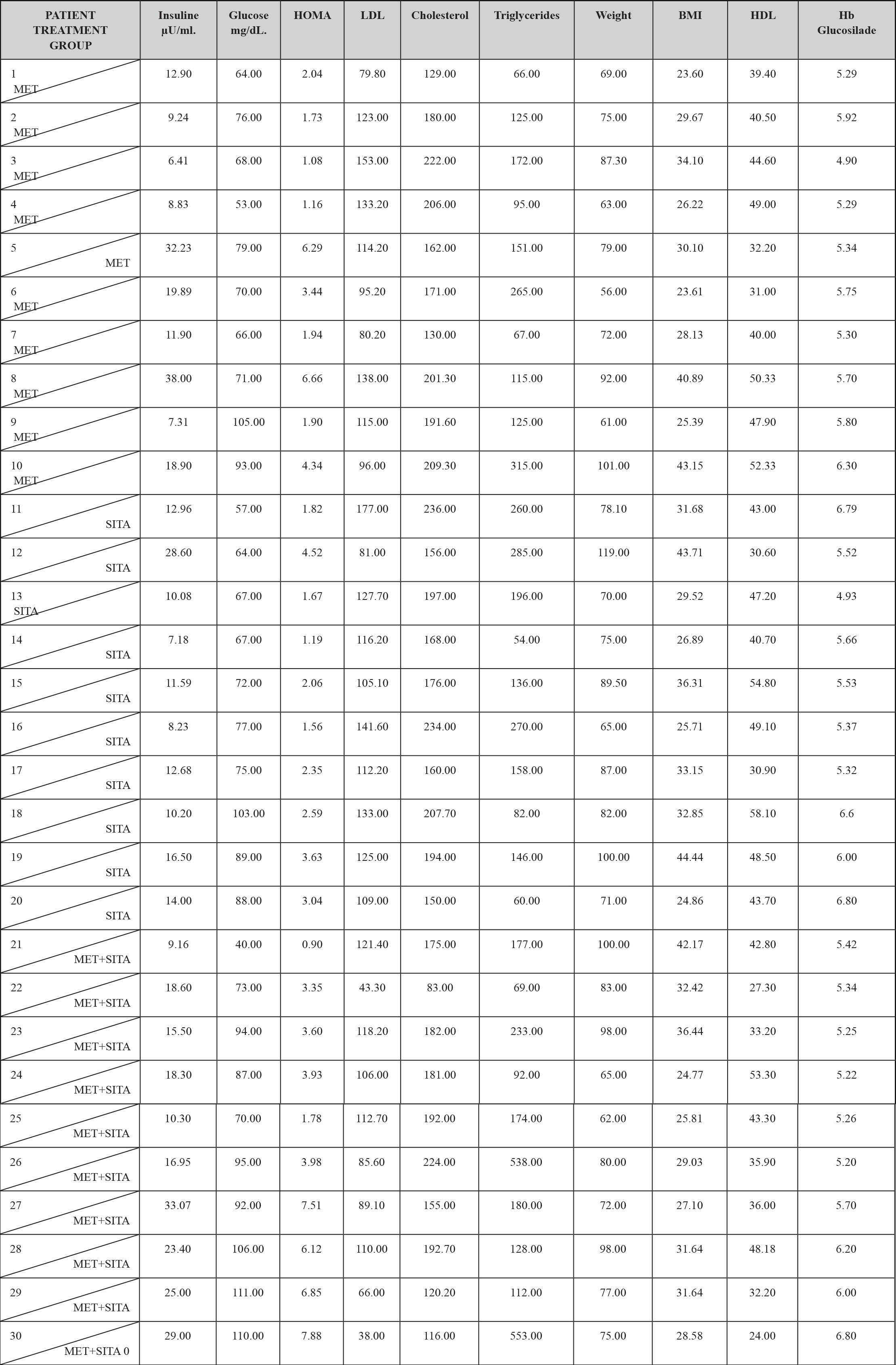

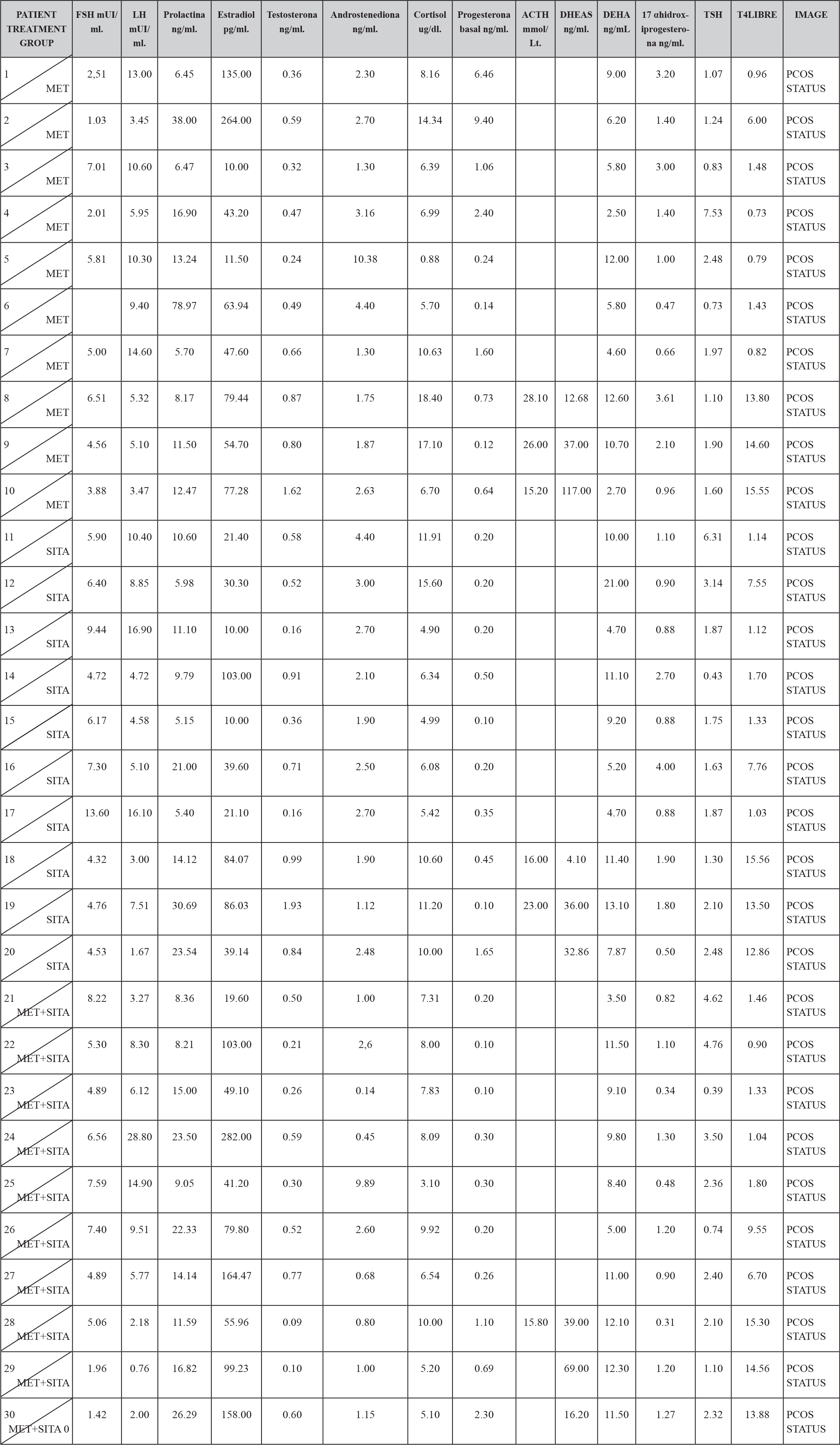

In the metabolic characteristics of the patients under study, it should be mentioned that 21 patients (7%) presented hypercholesterolemia, 15 patients (5%) presented hypertriglyceridemia, 20 patients (6.6%) presented LDL hypercholesterolemia, 8 patients (2.6%) presented abnormally low concentrations of HDL cholesterol.

On the other hand 5 patients (1.6%) had fasting altered glycemia, as well as 20 patients (6.6%) had basal hyperinsulinemia and 7 patients (2.3%) had insulin resistance and 28 patients (9.33%) disinsulinism.

Regarding the glycosylated hemoglobin in the 30 patients (100%), the value was normal, so the diagnosis of Diabetes Mellitus was ruled out by this criterion. (TABLE 3)

TABLE 3. BASAL METABOLIC CHARACTERISTICS BY TREATMENT GROUP.

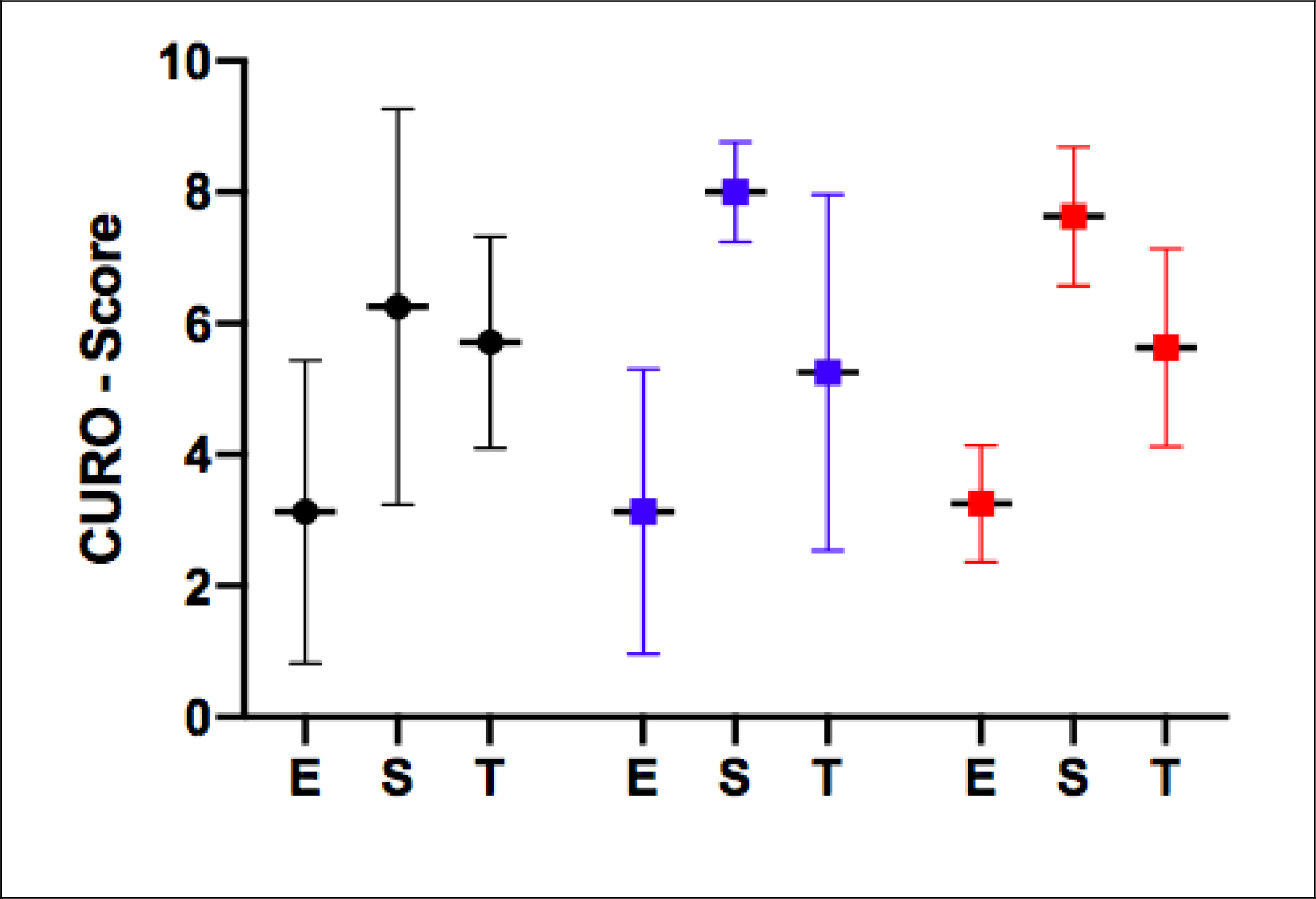

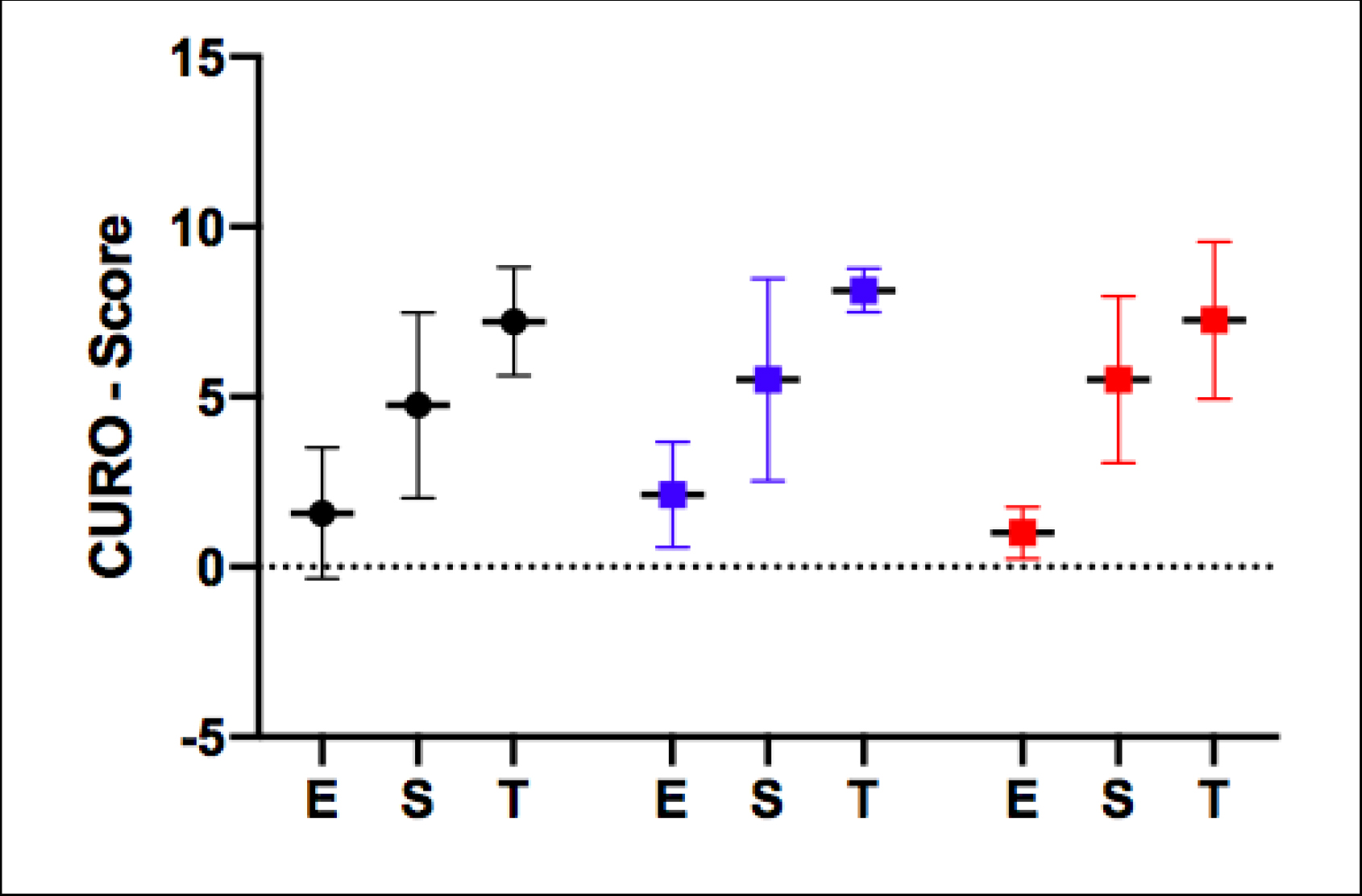

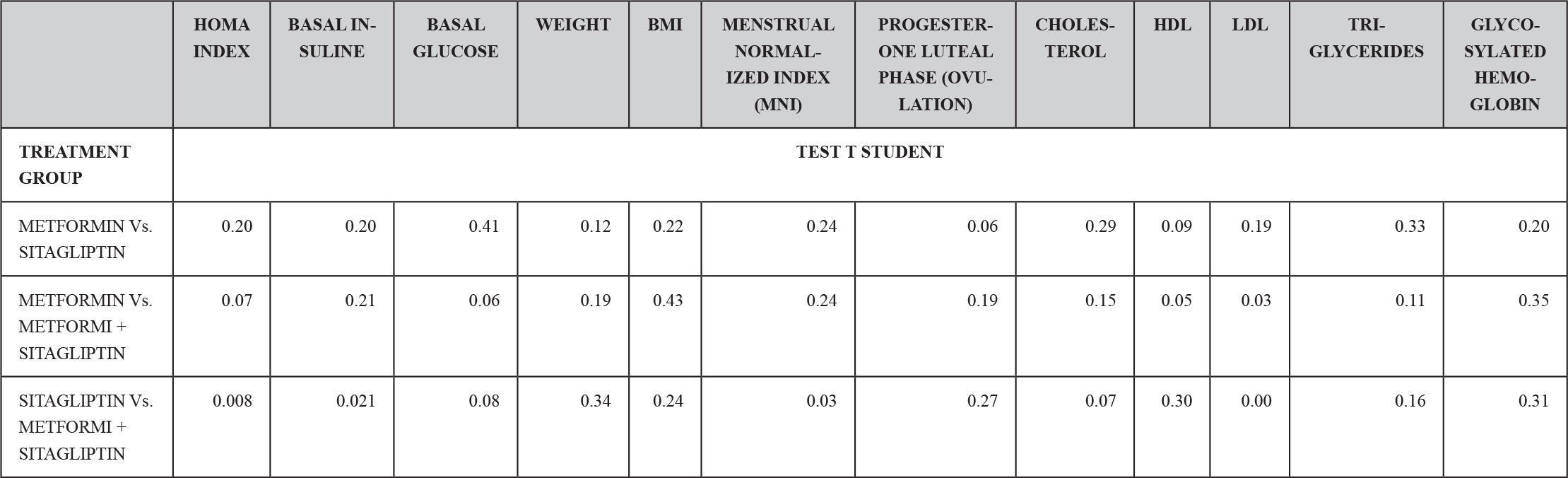

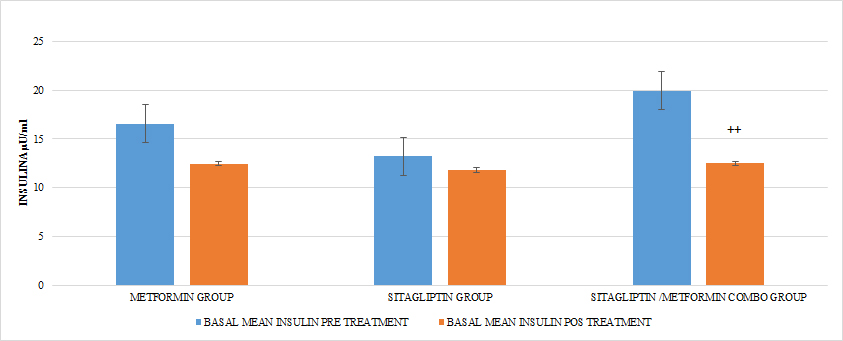

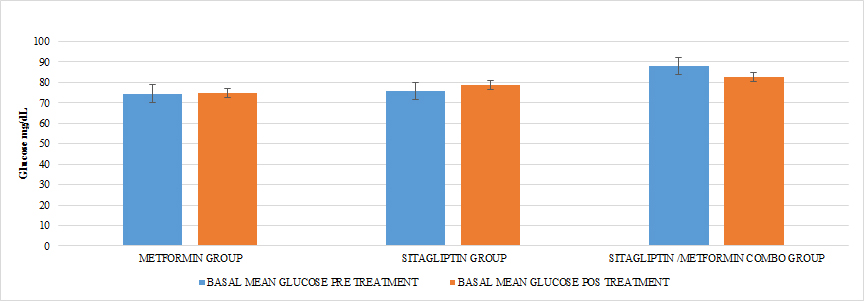

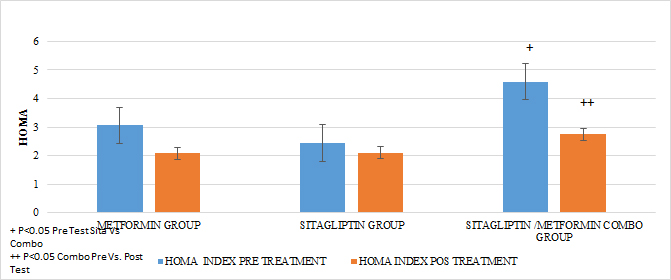

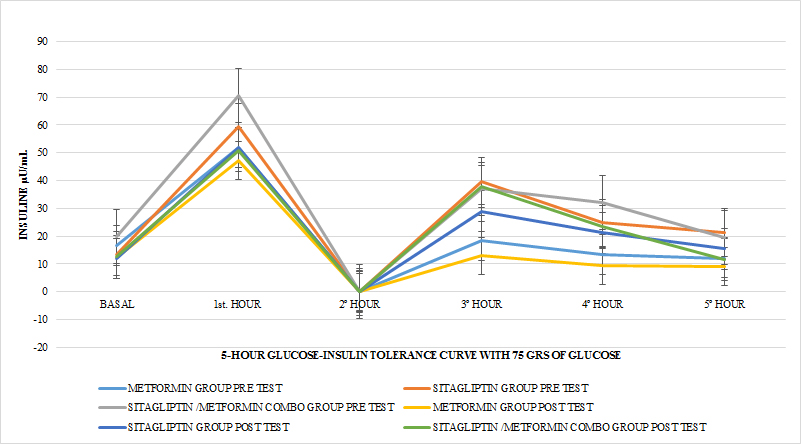

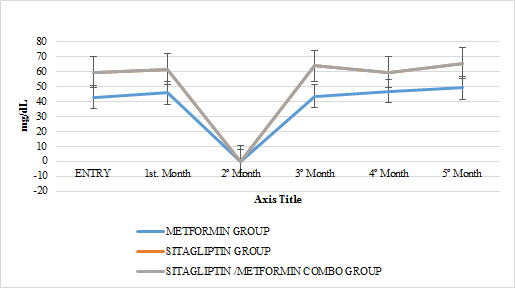

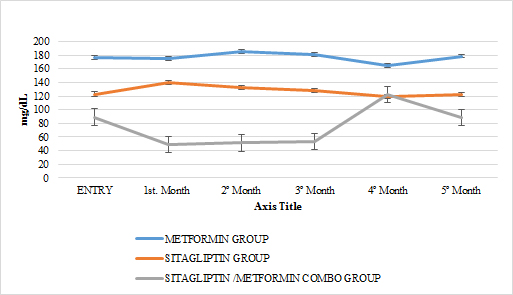

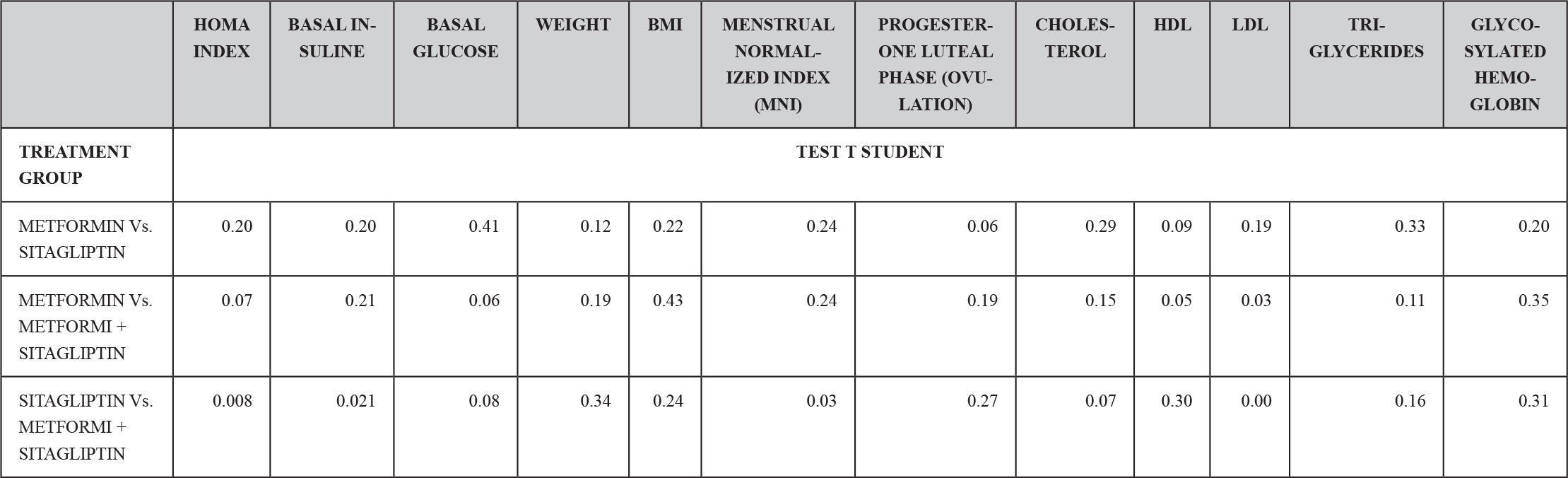

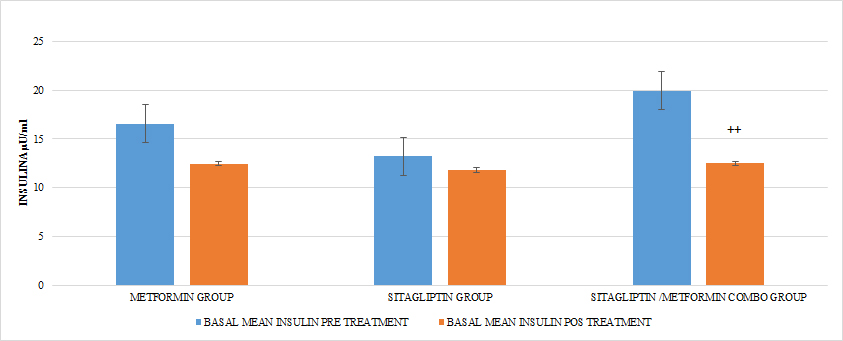

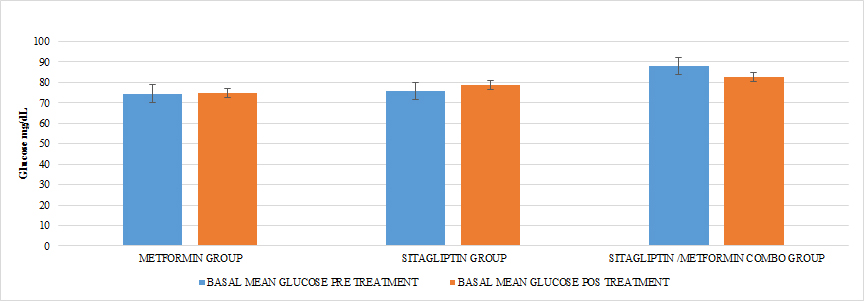

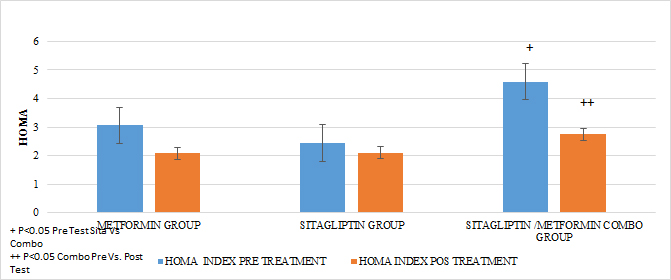

Ten patients were located in the group treated with metformin, ten patients in the group treated with sitagliptin and ten patients in the group treated with metformin + sitagliptin. The hormonal, anthropometric and metabolic characteristics between the groups were homogeneous at the beginning of the study except that in the combo group (MET + SITA) pretreatment vs the Sitagliptin group pre-treatment, initiation with greater insulin resistance (P <0.05) as well as the average basal insulin (p <0.05) but with a homogeneous index of menstruations in the three groups (P> 0.05), a condition that must be taken into account when analyzing the results for this group. (TABLE 4) (GRAPH 1)(GRAPH 2)

TABLE 4. TEST OF HOMEGENEITY OF THE TREATMENT GROUPS BEFORE THE CLINICAL ASSAY.

GRAPH 1. BASAL INSULINE PRE Y POST TREATMENT

GRAPH 2. BASAL GLUCOSE PRE AND POST TREATMENT

Although the patients were given counseling for the aspects of nutrition and exercise; only the recommendations of the international guidelines were proposed as part of the SOP management and it was sought that they had an adequate attachment, all the patients in each group reported having adhered to these recommendations in a percentage greater than 90%, so the effect of the intragroup and intergroup absolute weight loss and in the BMI, represents the effect of the medication in the corresponding group.

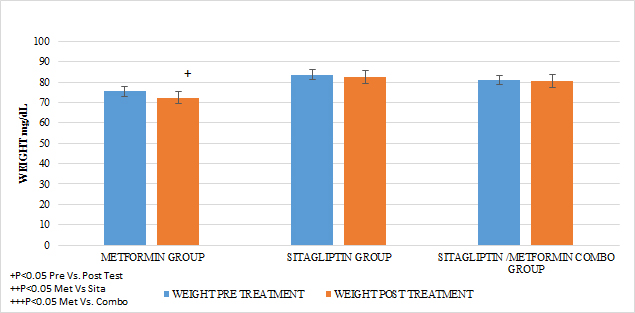

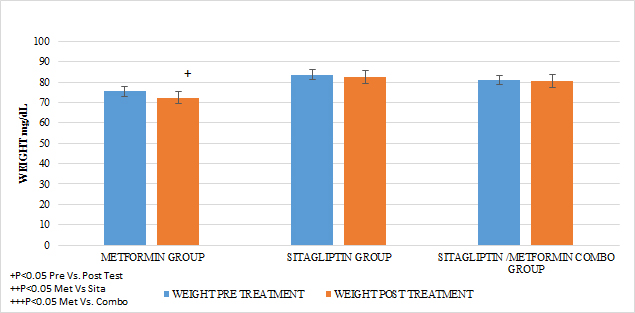

In all treatment groups there was a decrease in weight associated with the use of the medication, (p <0.05), with the percentage of change (5.8%) being higher for the metformin group and lower for the sitagliptin group (2.5%). The percentage of change for the COMBO group was 3.45%. There were significant differences in the intra-group reduction (p <0.05) in all the groups and in the comparison between groups a greater effect of the metformin group Vs sitagliptin (p <0.05) and in Metformin Vs Combo (p <0.05) was observed without having Differences between the sitagliptin group and the COMBO

(GRAPH 3)

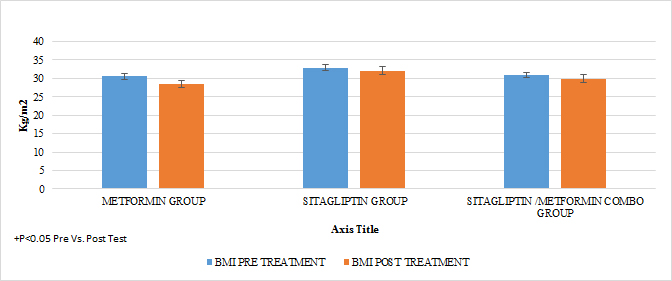

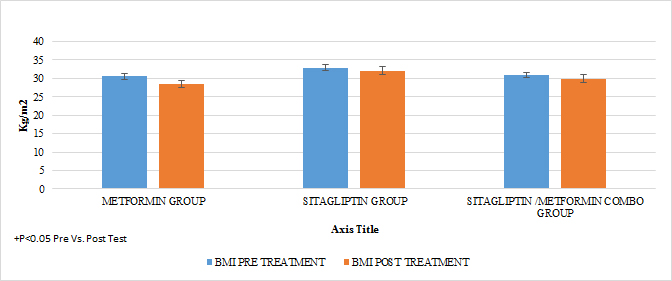

In terms of BMI in all groups there was a statistically significant reduction intragroups (p <0.05) not so between groups (p> 0.05) after 6 months of treatment (GRAPH 4)

GRAPH 3. WEGHT PRE AND POST TREATMENT

GRAPH 4. MASS BODY INDEX BMI PRE AND POST TREATMENT

A reduction in the statistically significant intra-group abdominal circumference was observed in that of metformin and COMBO (P <0.05), but not in that of sitagliptin and the metformin group showed a greater difference in the reduction of statistically significant BMIs Vs the group of sitagliptin and COMBO .

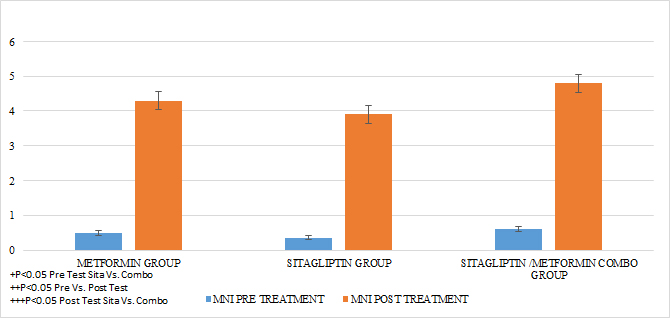

In the case of the normalized menstruation index, it was found that there was a statistically significant intragroup increase in each of the treatments. The group with the highest percentage of change was that of sitagliptin with 127%, followed by metformin with 87.5% and then COMBO with 60%. When comparing the effect of the treatment after 6 months, no statistically significant differences were found between Metformin Vs Sitagliptin, nor between Metformin vs. Combo. But the effect of the COMBO Vs Sitagliptin group was greater. (Student T test p 0.05) (GRAPH 5)

GRAPH 5. MENSTRUAL NORMALIZED INDEX (MNI) PRE AND POST TREATMENT

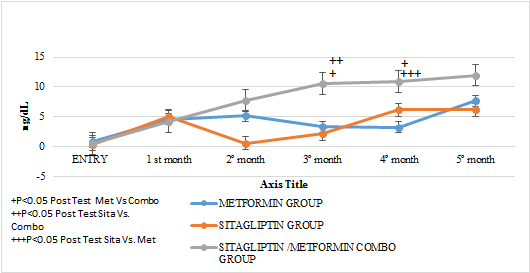

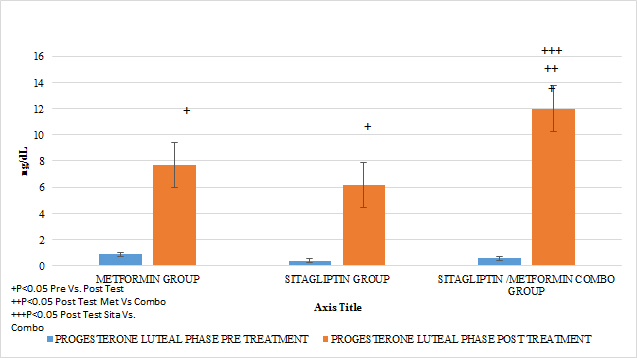

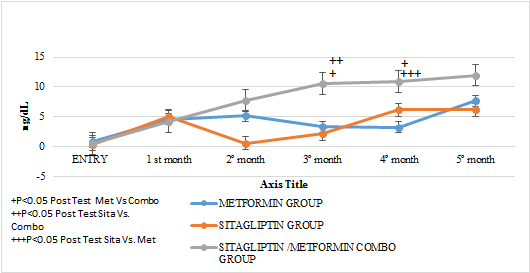

An increase in the number of ovulations was observed in all the groups reflected in progesterone concentrations as the treatment time was completed (P <0.05). It should be noted that none of the groups had statistically significant differences in the mean progesterone concentrations at entry into the study. No statistically significant differences were observed when comparing after 6 months of treatment between Metformin Vs Sitagliptin. But if greater effect between the group COMBO Vs Metformin and Vs Sitagliptin respectively. (GRAPH 6) (GRAPH 7)

GRAPH 6. PROGESTERONE LUTEAL PHASE (OVULATION) PRE Y POST TREATMENT

GRAPH 7. PROGESTERONE LUTEAL PHASE MEAN FROM 21 AND 24 DAYS (OVULATION) MONTHLY FOLLOW UP

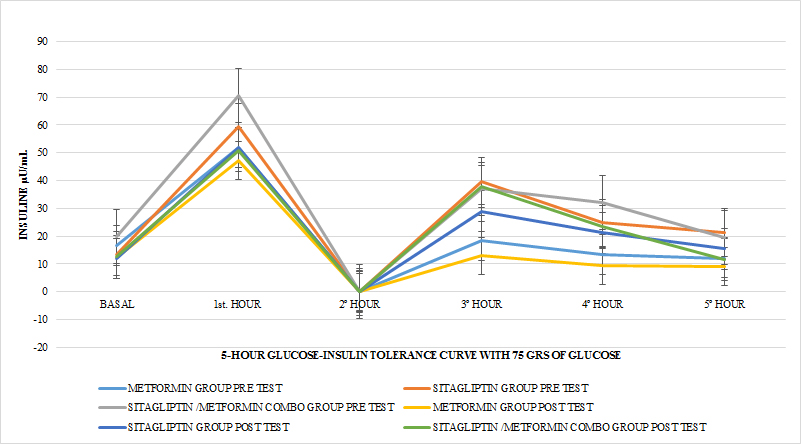

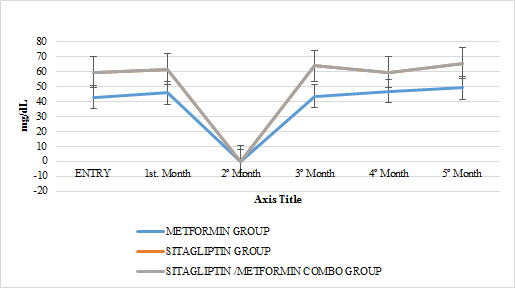

Regarding the effect of the drugs in each treatment group in terms of the HOMA pre Vs after treatment, in all the groups a tendency of decrease of the resistance was observed only reaching the statistically significant difference in the COMBO group, there were no statistically significant differences compare the effect on insulin resistance between the treatment groups (GRAPH 8). In the secretion of insulin it was observed that both in the group of metformin and sitagliptin there was a decrease in the average concentrations of insulin, especially in the middle and final part of the secretion curve. However, a greater delta of change was observed in the sitagliptin group, especially in the 2nd, 3rd and 4th hours of secretion. (7, 9 and 9 μU / ml of insulin respectively). Compared to 4.6, 0 and 6 μU / ml of insulin at the same times for metformin. In the case of the COMBO group, a reduction in secretion was observed at all times of the curve with a delta change of 6, 19, 0.8 and 6 μU / ml of insulin in each of the hours of determination. The statistical tests for the group of Metformin and Sitagliptin showed no differences in the intragroup change (paired T> 0.05) as well as between each secretion moment between groups (ANOVA p> 0.05). (GRAPH 9) In the case of the COMBO group I present statistically significant differences intragroup but not when compared with the other two treatments. (GRAPH 1)

GRAPH 8. HOMA PRE AND POS TREATMENT

GRAPH 9. INSULIN INTEGRATED SECRETION IN 5 HOURS PRE AND AFTER TEST

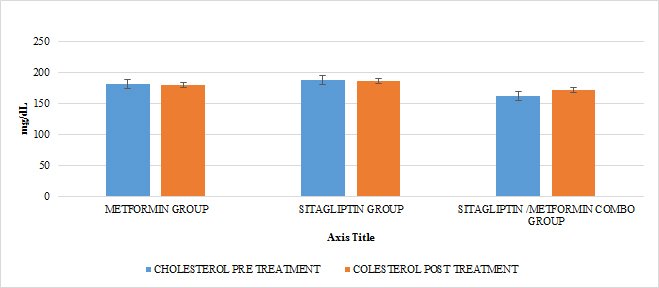

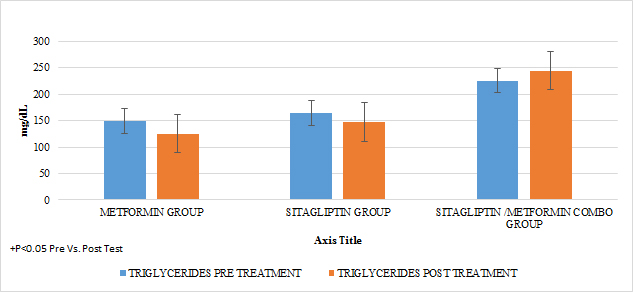

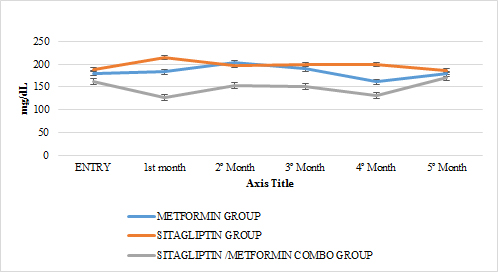

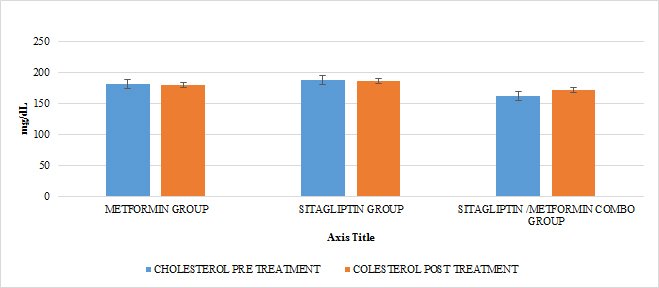

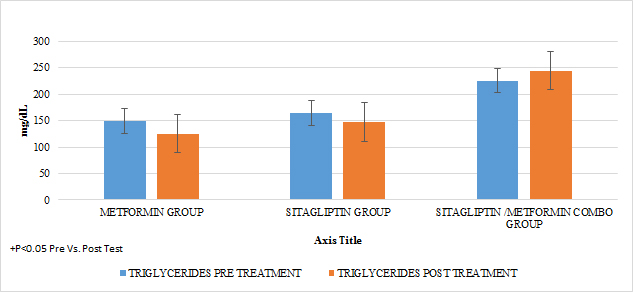

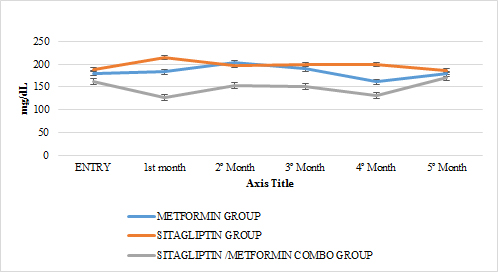

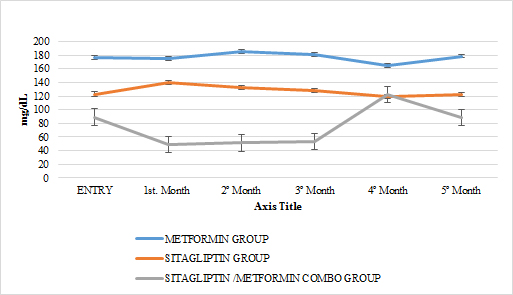

In lipids there was no effect of any of the treatments only in the case of metformin in terms of triglycerides if there was a statistically significant reduction (paired T-test p <0.05) with a delta of change of 24.04gr / dl decrease (16 %). An increase in HDL cholesterol was also observed in this group with a change delta of 6.38 (14.9%) (Paired T test p <0.05) (GRAPH 10–13)

GRAPH 10. CHOLESTEROL PRE AND POST TREATMENT

GRAPH 11. TRIGLYCERIDES PRE Y POST TREATMENT

GRAPH 12. TOTAL CHOLESTEROL MONTHLY FOLLOW UP

GRAPH 13. CHOLESTEROL HDL MONTHLY FOLLOW UP

GRAPH 14. CHOLESTEROL LDL MONTHLY FOLLOW UP

Discussion

The group of patients with PCOS had homogeneous characteristics and no statistically significant differences. In the case of the COMBO group at the beginning, significantly greater resistance to insulin was found than the Sitagliptin group, part of the effect that was observed 6 months after the start of the treatment superior to sitagliptin could have been due to this fact. The INM Menstruation Normalized Index did not show statistically significant differences between the groups at the beginning of the treatment. It is noteworthy that within the groups of sitagliptin vs metoformine the biochemical, clinical and hormonal characteristics did not show statistically significant differences and the effect on increased frequency of menses is comparable to that observed in the metformin group, considering that the basal rate of menstruation was greater in the sitagliptin group. Although the trend suggests that sitagliptin would have a greater effect on the increase in the frequency of their menses, no significant differences were found after 6 months. This stands out from the pilot study carried out by Paredes et al., Where the group with the highest delta change was metformin and this study coincides with the fact that no statistically significant differences were found after 6 months of treatment. These changes may be due to the greater number of samples in the present work. In the case of the COMBO group, the effect on the frequency of menses also reached group significance and after 6 months had a greater effect than sitagliptin, unlike those found in the pilot study, the latter can also be explained by the greater amount of patients included in the sample of this study. In the case of the Elkind-Hirsch K. study, in which metformin vs exenetide vs COMBO was compared, an increase in the frequency of menses was observed in all groups, however between groups there were also significant differences for weight loss. that the effect of exenetide on the frequency of menses can be due to this phenomenon [16].

In the case of our study, statistically significant differences in weight were observed before and after any treatment group, so we observed in terms of increased frequency of menses and ovulation could be attributed to this fact, however the percentage delta of change in minor weight of the group of sitagliptin Vs Metformin and the fact that after 6 months of treatment there was greater statistically significant weight loss in the group of Metformin Vs Sitagliptin and Vs COMBO and before the results of finding greater effect of sitagliptin in the INM and in terms of ovulation leads us to think that in the case of sitagliptin the effect in the treatment should be explained by other phenomena besides weight loss, at a certain moment we would have to carry out a study evaluate the presence of receptors and their mechanisms of action of sitagliptin within the ovary or within the reg ulation of the pituitary-ovary axis. This also highlights what was found in the pilot study where none of the treatment groups presented differences in weight, supporting the previous statement of the need to study other possible sites of action of sitagliptin in the reproductive regulation of women with PCOS. . It is noteworthy that although the COMBO group was less efficient in terms of increasing the frequency of menses, its effect on ovulation was greater than in other treatment groups, which could suggest that it is due to the additive effect that sitagliptin provides to the treatment. . In the Paredes et al pilot study, the findings were consistent with the above. In terms of insulin secretion, it should be noted that although sitagliptin is not considered an insulin sensitizer, it has been observed that it decreases insulin plasma concentrations, perhaps by influencing a better functioning of the pancreatic beta cell, in our studies showed a significant decrease in insulin secretion, even with delta change greater than in the metformin group in the first part of the secretion curve, but without reaching differences statistically between both groups, these findings are consistent with the observed in the weight loss in the treatment groups as well as with the behavior of the HOMA, where the intra-group trend was observed in all the treatments, the tendency to reduction after 6 months of treatment and with greater effect in the COMBO group, however, there is to consider that this group started with a higher degree of insulin resistance compared to other groups, so its greatest effect can be explained by this cause. This has also been observed in a study conducted by Kazaka Aoki et al [15]. In the case of the lipid profile, the only treatment that showed a pleiotropic effect for triglyceride reduction and an increase in statistically significant HDL cholesterol was Metformin, an effect that seems independent of weight reduction and insulin resistance. In many other studies, there has also been no effect of sitagliptin and even metformin on lipid metabolism [9,8,10,11,15], even in the pilot study conducted by Paredes et al [20].

Conclusion

Sitagliptin improves ovarian cyclicity and ovulation in women with PCOS in comparable terms with respect to metformin and the metformin sitagliptin combination. The combination of sitagliptin metformin is more effective in terms of ovulation than the other two treatments alone. However, sitagliptin showed that it can influence the reproductive and intra-ovarian aspect. Similarly, it showed that it can improve the metabolism of insulin in patients with PCOS, so it would be interesting to show if it could be a treatment that not only improves the clinical, metabolic and reproductive conditions of patients with PCOS, but also prevents the development of Diabetes. Mellitus, a highly frequent consequence of these patients. The weight did not change the results of the findings.

References

- John E. Nestler, M.D. Metformin for the treatment of the polycystic Ovary Syndrome. N ENG J MED; 2008; (358): 47–54.

- Moran C, et al. Prevalence of Polycystic Ovary Syndrome and related disorders in Mexican women. Gynecol Obst Invest. 2010; 69(4): 274–280.

- Kelsey E.S., et al. Position Statement: Glucose Intolerance in Polycystic Ovary Syndrome – A Position Statement of the Androgen Excess Society. JCEM 2007; 92(12): 4546–4556.

- The Rotterdam ESHRE/ASRM-Sponsored PCOS Consensus Workshop Group; Revised 2003 consensus on diagnostic criteria and long-term health risk related to polycystic ovary syndrome; Fer Ster 2004; 81: 19–24.

- David A. Ehrmann, M.D. Polycistic Ovary Syndrome. N ENGL J MED 2005; 352: 1223–1236.

- Evanthia Diamanti-Kandarakis, et al.; Molecular mechanisms of insulin resistance in polycystic ovary syndrome; Trends Mol Med 2006; 12 (7): 324–332.

- Mario Ciampelli1, et al. Human Reproduction. 1998; 13 (4): 847–851.

- Christian RC, et al.; Prevalence and predictors of coronary artery calcification in women with polycystic ovary syndrome. J Clin Endocrinol Metab 2003; 88: 2562–8

- Daniel J. Drucker, MD. Enhancing Incretin Action for the treatmen of type 2 Diabetes. Diab Care 2003; 26.

- Chee W. Chia, Jophine M. Egan. Incretin-Based Therapies in type 2 Diabetes Mellitus, J Clin Endoc Metab 2008; 93: 3703–3716.

- Jana Vrbikova, et al.; Incretin levels in polycystic ovary syndrome; Eur J End 2008; 159: 121–127

- Charalambos Pontikis et al.; the Incretin Effect and Secretion in Obese and Lean Women with Polycystic Ovary Syndrome: A Pilot Study. J Women’s Health 2011; 20 (6).

- Oscar Velázquez Monroy, Agustín Lara Esqueda, Roberto Tapia Conyer. Metformina y Síndrome Metabólico. Secretaria de Salud 2002.

- Bruno et al.; Comparison of two doses of metformin (2.5 y 1.5 g/day) for the treatment of polycystic ovary syndrome and their effect on body mass index and waist circumference; Fertil Steril 2007; 88 (2): 510–512.

- Kazutaka A, et al.; Effects of miglitol, sitagliptin or their combination on plasma glucose, insulin and incretin levels in non-diabetic men; Endo J 2010; 57 (8): 667–672.

- Karen Elkind-Hirsch, et al.; Comparision of Single and Combined treatment with Exenatide and Metformin on Menstrual Cyclicity in Overweight Women with Polycystic Ovary Syndrome. JCEM 2008; 93: 2670–2678.

- Leigh P. et al.; Incretin action maintains insulin secretion, but not hepatic insulin action, in people with impaired fasting glucose; Diab Res Clin Prac 2010; 90: 87–94.

- Solomon C. et al.; Long or Highly irregular menstrual cycles as a marker for risk of type 2 Diabetes Mellitus 2001; JAMA; 286: 2421–2426.

- Desiletes A. et al.; Rle of Metformina for weight management in patients without type 2 Diabetes; Ann Pharmacother 2008; 42: 817–826.

- PAREDES JC et al: Comparative treatment between Sitagliptin vs. Metformin, alone or in combination, in patients with Polycystic Ovarian Syndrome. A clinical entity with a high risk of developing diabetes mellitus and gestational diabetes; Rev Med Hosp Gen Mex 2018; 81(1): 15–26.