DOI: 10.31038/GEMS.2024673

Abstract

The Eifel Volcanic Field (EVC) is one of the best-known intraplate volcanic fields on earth. Carbonatitic ejecta were already described at the beginning of the last century and were associated with volcanism. The investigation of carbonatitic tephra from the EVC, the Kaiserstuhl (KVC) and El Hierro (EHSR) with regard to shape, size, composition and geochemistry, together with thermodynamic and fluid mechanical considerations, allow a reconstruction of the eruption process that ultimately calls into question the sole interpretation of maar formation as a phraetomagmatic eruption.

Introduction

In their overview of the worldwide distribution of carbonatites, Woolley and Kjarsgaard (2008) [1] report 527 carbonatite localities, 46 of which are classified as extrusive. The ratio is unlikely to have changed significantly to date. While the intrusive carbonatites represent the frozen state of a relatively slow intruding melt that has cooled in the host rock, the extrusive carbonatites are the result of sudden events that, due to the physical nature of the carbonatite melts, leave behind mechanical but only minor chemical traces. The genesis of carbonatitic melts can be very different, depending on whether they occur alone or in combination with alkali silicate rocks. They can be formed primarily by partial melting in the mantle or also by fractional crystallization of melilitic-nephelinitic magmas or generally by segregation of silicate melts supersaturated with carbonate [2]. In all cases considered, the carbonatitic events are determined by the unique properties of the carbonatite melts themselves [2]. For example, carbonatites generally have a high solubility for rare earth elements, which makes them economically interesting. They have a strongly pressure-dependent density of 2000 kg /m3 at P = 0.1 GPa up to 2900 kg/m3 at P = 10 GPa, a very low viscosity and a high solubility of CO2 and H2O (Genge et al 1995). The high solubility of CO2 in carbonatitic melts is associated with the onset of incongruent melting of CaCO3 at temperatures > 1230°C and a pressure range of 0.1 – 0.7 GPa according to the reaction [3].

2CaCO3 (solid) = (CaCO3 +CaO)(liquid) + CO2 Eq (1)

A further increase in pressure ultimately leads to congruent melting [3-4]. The incongruent melting behavior of CaCO3 explains the high saturation of carbonatite melts with CO2 . This saturation is associated with a drastic reduction in the melting temperature (solidification temperature). According to Huang and Wyllie (1976) [5], saturation of the carbonate melt with CO2 to 11.5 wt% at 2.7 GPa results in a melting point reduction from 1610°C to 1505°C. Investigations by Eggler (1974) [6] on the solubility of CO2 in diopside at 3 GPa show that mantle silicate melts dissolve approx. 5 wt% CO2 , which is associated with a melting point reduction of 120 degrees. Due to the incongruent melting behavior of the carbonate [Eq (1)], a high CO2 content of the melt combined with high fluidity and low density is inevitable. A high H2 O content also has the effect of lowering viscosity and melting point, which is particularly important in silicate melts. The low viscosity of carbonatitic melts leads to magma ascent velocities of 20 – 65 m/s (70-230 km/h) if the appropriate tectonic conditions are present [45]. However, this also means that extrusive carbonatitic events are unpredictable. Furthermore, rapid magma ascent leads to rapid depressurization, which results in spontaneous release of the CO2 dissolved in the melt and decomposition of the carbonate according to the relationship leads.

CaCO3 = CaO + CO 2 Eq (2)

This creates a gigantic CO2 fan at depths of 3 – 20 kilometers. This means that the probability of carbonatitic melt reaching the earth’s surface is very low. Such carbonatitic diatreme fillings are characterized by a quantitatively high proportion of accessory rock xenoliths, which can amount to 70% and more [7]. Silicate-magmatic tephra occurs when the eruptive reservoir is a carbonate-bearing silicate magma. Stoppa et al (2003) [8] have pointed out these processes. The type of eruption also means that only small traces of the carbonatite itself can be found. This may also be the reason why only a small number of extrusive carbonatites have been detected to date. A model is being developed from the known data of carbonatitic melts, which allows a better understanding of the phenomena associated with carbonatitic volcanism and a better interpretation of the material found in the field. For this purpose, data from sample material from three known volcanic fields are used: the Eifel (EVC = Eifel Volcanic Complex), the Kaiserstuhl KVC = Kaiserstuhl Volcanic Complex) and El Hierro (EHSR = El Hierro South Rift).

Geological Context of the Regions Belonging to the Sample Material

EVC, Eifel Volcanic Complex

One of the most famous intraplate volcanic districts in the world is located in the Eifel, as it contains the type locality of the Maar eruption type. The Eifel volcanic field has two quaternary volcanic fields that follow tectonic northwest-southeast AC fissures of the Variscan folded crust. The West Eifel consists of around 240 eruption centers, the East Eifel of around 100 [9]. Due to the economic use of the volcanic structures for the extraction of building materials, gravel and pumice, the two Eifel volcanic fields are excellently accessible for geological investigations. Multiphase volcanic activity began in both volcanic fields around 700 ka ago [10-11]. The last activities occurred in the Western Eifel around 11 ka ago with the eruption of the Ulmen Maar [12] and in the Eastern Eifel around 13 ka ago with the eruption of the Laacher See Volcano [13]. Two older foidite suites (melilitite, melilitite-nephelinite and ol-nephelinite/leucitite and leucite- phonolite) and a younger basanite-tephrite-phonolite suite [14-16] occur in both volcanic fields. In the West Eifel, the basanite suite first appears around 80 ka, in the East Eifel at around 215 ka [10-11]. These alkali-rich magmas originate from varying degrees of partial melting in the upper mantle (< 120 km), which were subjected to more or less strong differentiation by fractional crystallization on their way to the Earth’s surface. The foiditic magmas in particular are potential sources of carbonate-bearing to carbonatitic magmatic rocks, which have long been known from the Laacher See region [17-19]. They were first described from the West Eifel by Lloyd and Bailey (1969) – [20] and again investigated by Riley et al. (1996) [21] and Riley et al. (1999) [22]. To date, however, scientific interest in the Eifel carbonatites has remained rather low. A dissertation on the genesis of the Laacher See carbonatites was published by Liebsch (1997) – [23]. He interpreted the Laacher See carbonatites as precipitates from a phonolitic silicate melt supersaturated with carbonate in the last stage of differentiation and cooling. This work is little known as its results have not been published. Schmidt et al. (2010) [24] investigated the temporal development of intrusive carbonatites using uranium-thorium dating on the same sample material. Since 2019, an international working group led by the German Volcanological Society has turned its attention to the problem of Eifel carbonatites. The initial focus is on a geological survey combined with the discovery of further carbonatite deposits.

The carbonatite deposit of the Laacher See volcano is the youngest in the Eifel with an age of 13 ka years. The other known carbonatite deposits in the Eifel are located in the Rieden complex (Eastern Eifel) [25] and in the Western Eifel in the Rockeskyll and Essinger Maar area. They are generally linked to phonolitic magmatism and are characterized by the associated occurrence of sanidine megacrysts with masses of up to 60 kilograms. In terms of age, the West Eifel deposits can be dated to approx. 469 ka years ago and the East Eifel deposits to 410 ka years ago [10, 26]. If one takes the conspicuous association of sanidine megacrysts and carbonatites as an indicator, then there are still 3 carbonatite-rich areas. One area is the Kerpener- Maar in the West Eifel. This is a phonolitic maar, which is also known for its sanidine megacrysts [14]. The other two deposits are located in the Eastern Eifel. One is located on the southern edge of the Wehrer Kessel, a polyphase phonolitic eruption center where, according to Frechen (1976) [27], sanidine megacrysts were also found in the Wehr I tephra. The age of the deposits of the Wehr I eruption is given by Wörner et al. (1988) [28] as 480 ka years. The other occurrence is in the area of the Leilenkopf near Niederlützingen, where the oldest melilitic-nephelinitic deposits of the Leilenkopf volcano are also said to contain sanidine megacrysts [29]. The age of these sanidine ejecta was determined to be 405 ka years [30]. However, all 3 of these carbonatite-rich deposits are currently unexplored.

KVC, Kaiserstuhl Volcanic Complex

The Kaiserstuhl Volcanic Complex is the best-studied carbonatite complex in Europe [31-34]. Its age is given as 16-19 Ma [35], Braunger [36]. It consists mainly of tephritic to phonolitic rocks, associated with a small proportion of olivine nephelinites and melilites. The youngest formations are the carbonatites, whose age is given as 15 Ma [33]. The magmatic origin of the carbonatites from the Kaiserstuhl was first postulated by Högbom in 1895 [33]. The carbonatites of the KVC occur both as subvolcanic carbonatite bodies of sövitic character and as extrusive events in the form of dykes, veins and carbonatitic tephra. Carbonatitic tephras are of particular importance for the investigation of the eruption mechanism of carbonatitic volcanoes. A special feature of the Kaiserstuhl ejecta are the lapillite tuffs known from Henkenberg and Kirchberg, which are only known from a few other localities (Cape Verde, Silva et al. 1981 [37], Fort Portal Volcanic Field, Uganda, Barker and Nixon 1988) [38]. They are so distinctive that they form the locus typicus for this type of tuff. Since this paper is concerned with the interpretation of the eruption mechanisms of carbonatitic volcanoes, only those samples that can be expected to contribute to this topic were considered in the processing.

Region El Hierro, South Rift (EHSR)

El Hierro is one of the seven volcanic islands of the Canary Islands archipelago, which is located approximately 100 kilometers northwest of Africa in the Atlantic Ocean. The age of the archipelago is estimated at around 60 million years, with the island of El Hierro being the youngest link in this chain at around 1.2 million years old. All islands are considered volcanically active [39]. El Hierro can be divided into 3 rift systems [40]. The North-East Rift (Tinor Volcano, 1.2-0.88 Ma), the West Rift (El Golfo Volcano, 0.55-0.176 Ma) and the South Rift (0.158 Ma – today). The South Rift is the youngest formation and had its last eruption in 2011 as a submarine volcano off the southern tip of the island. The South Rift volcanism is characterized by highly differentiated lavas of tephritic character. Such lavas originating from tephritic magmas are certainly indicative of carbonate-enriched silicate rocks and their differentiates (carbonatites). The search for carbonatitic ejecta is therefore quite promising and opens up the possibility of verifying the thesis of the dissociation of CaCO3 with subsequent recombination according to equations 2 to 5 by applying the C14 determination method. Since C14 is only formed under the influence of high-energy particles in the atmosphere, volcanic CO2 is ad hoc free of C14 . If the detection of C14 in carbonatitic tephra is successful, then the proof for the sequence of reactions according to equations 2 to 5 is provided. As the isotope C14 is a relatively short- lived nuclide with a half-life of 5730 years, verification must take place in a young volcanic area with carbonatitic episodes. Through a systematic search, the author found suitable sample material for a C14 determination in the South Rift of El Hierro.

Gas Mechanical Processes in the Light of Volcanology

Depending on pressure, flow velocity, flow type, solid and liquid content, a gas flow through a tube produces effects that have long been used in technology and that can be studied excellently on extrusive carbonatites from the Eifel. Some of the gas-mechanical processes that we will deal with below are known as fluidized bed processes. In volcanology, publications dealing with this topic appear from time to time [41-44].

Basically, three processes can be distinguished in the fluidized bed process, depending on the prevailing conditions:

- Agglomeration, granulation, integration

- Abrasion, disintegration, fragmentation

- Transportation

The result of all three modes can be demonstrated on diatremes in the Eifel.

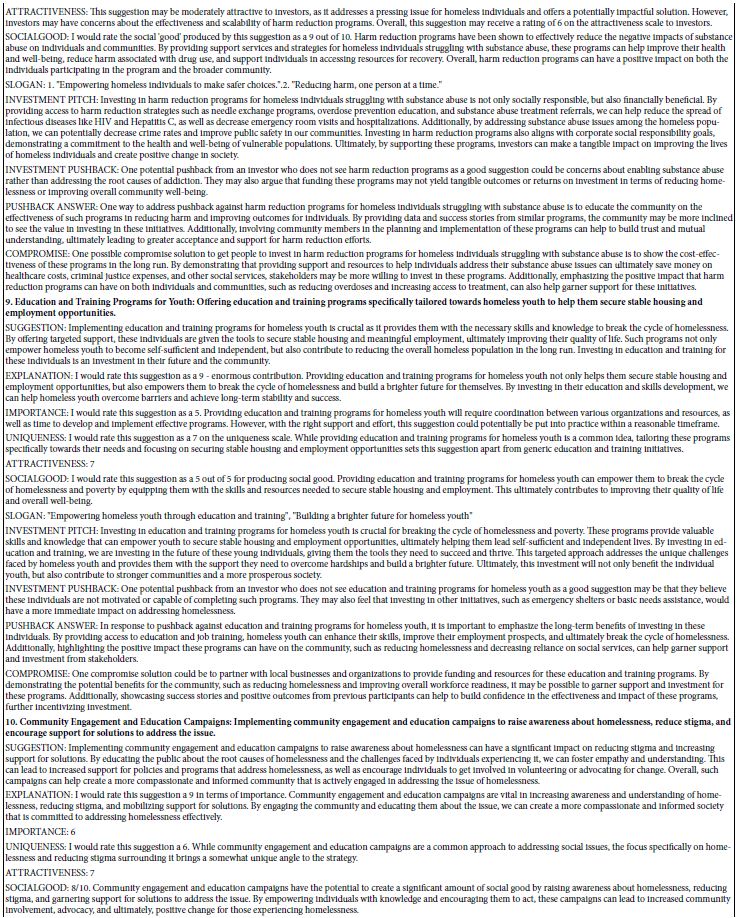

We want to understand a diatreme sensu stricto as a volcanic ascent channel, which is very narrow in relation to its length and can reach the Earth’s mantle under certain circumstances. It is tectonically pre-formed and is created by mechanical fragmentation as a result of rapidly rising highly fluid melts (70-230km/h; Genge et al 1995) [45]. In the case of carbonate-containing melts, these reach a pressure level during ascent at which the decomposition reaction of the calcium carbonate according to Eq. (1) and Eq. (2) begins explosively, which is accompanied by a fragmentation of the residual channel up to the earth’s surface. This leads to foreign xenolith contents of up to 70% and more in the eruption centers. The explosive initial phase can be followed by a quieter degassing phase, which can be described by a kind of boiling reaction in a relatively narrowly defined area of the ascent zone, whereby this area can be characterized by the diameter of the diatreme and the thickness of the boiling zone. The intensity of the eruption is determined by the amount of material extracted from the depth per unit of time. The onset of the reactions according to equations (1) and (2) is associated with the emission of large quantities of CaO in the volcanic ejecta. This fact has not yet been mentioned in the literature, although one has to ask how carbonatitic tuff was formed. Obviously, it is tacitly assumed that a carbonate liquid phase cemented the tephra particles. However, we have no known C, O and Sr isotope data to prove that the binding phase of the tephra is magmatic in nature (according to the usual criteria for magmatic isotopy, Taylor et al. 1967) [46]. As a way out of this dilemma, it is argued that the isotopy of the tephra has been altered by alteration processes (Demeny et al 1998) [47].

Accordingly, large quantities of CaO and CO2 are released into the atmosphere during the eruption. The overall isotopic picture of the CaCO3 is therefore split into a CaO isotope and a CO2 isotope. Both components are carried into the atmosphere, where they are influenced by the prevailing conditions such as humidity, temperature and air velocity. While the CO2 remains as a gas, the CaO sinks back to the earth’s surface as dust. The CaO can recombine with volcanic CO2 or CO2 from the air or react with the moisture in the air. The following reactions are possible:

CaO + CO2 = CaCO3 Eq (3)

CaO + H2 O = Ca(OH)2 Eq (4)

Ca(OH)2 + CO2 = CaCO3 + H O2 Eq (5)

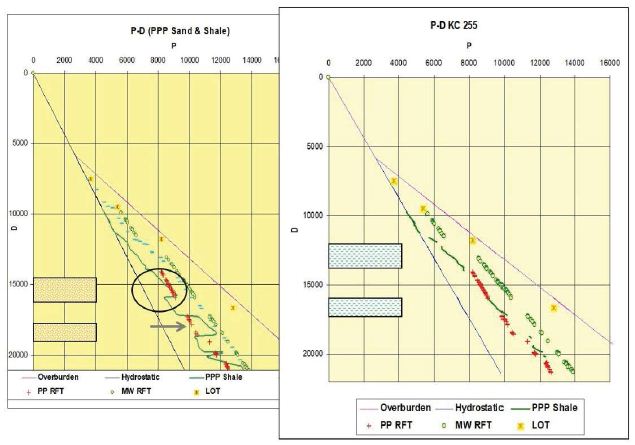

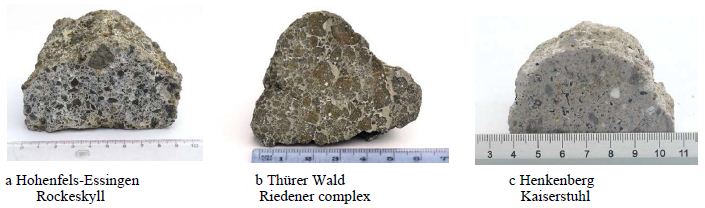

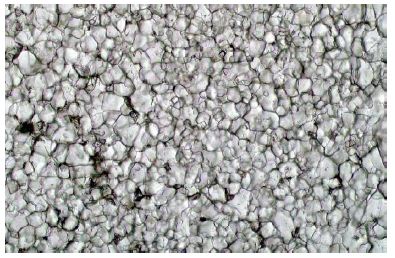

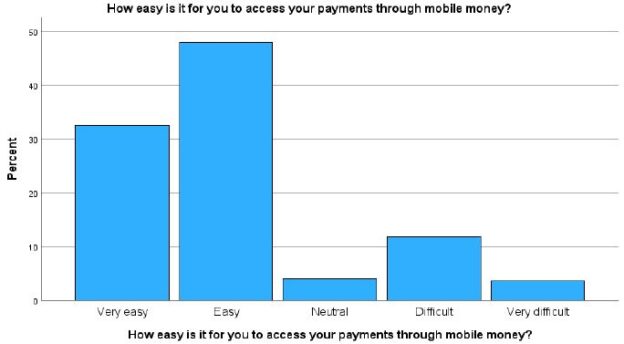

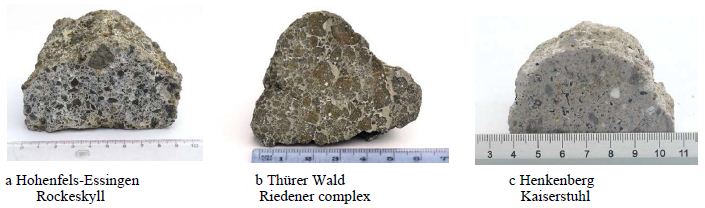

There is therefore ultimately a fallout of clasts (predominantly xenoliths from secondary rocks, but also xenocryst fragments from the primary carbonate melt) and a dust mixture of CaO, Ca(OH)2 and CaCO3 , with CaO as the main component. This dust forms the binding material for the carbonatitic tuff, whereby CaO and Ca(OH)2 are transformed into CaCO3 by the atmospherics according to Eqs. (4) and (5), a process that also takes place with quicklime. Ultimately, a tuff with a carbonate binder phase is formed. We will return to these facts below (Figure 1a-1c).

Figure 1a-c: Tuff with carbonate binder phase.

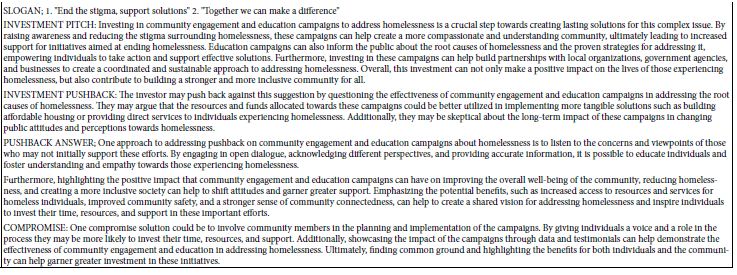

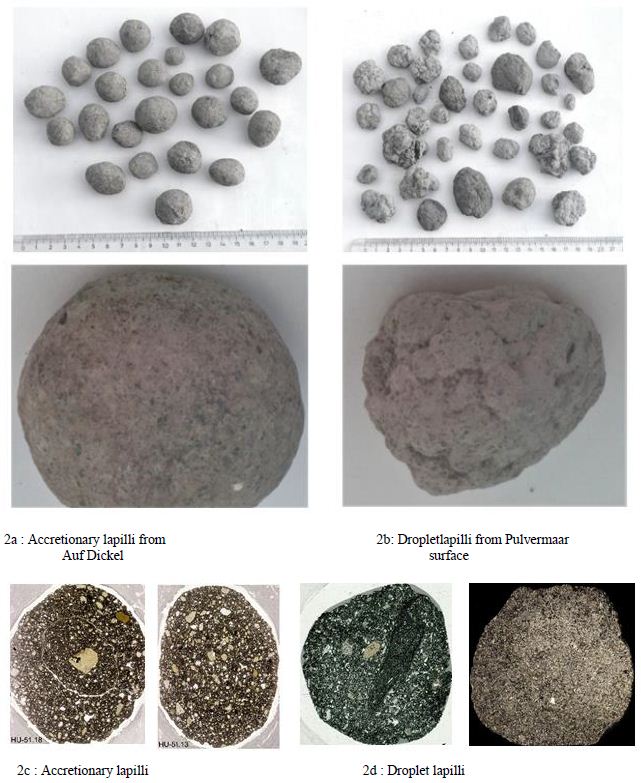

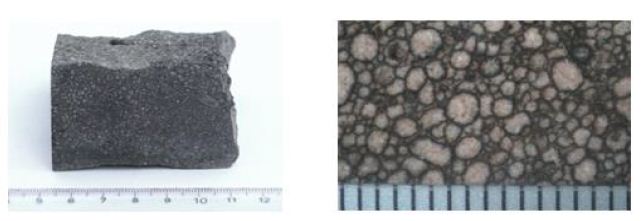

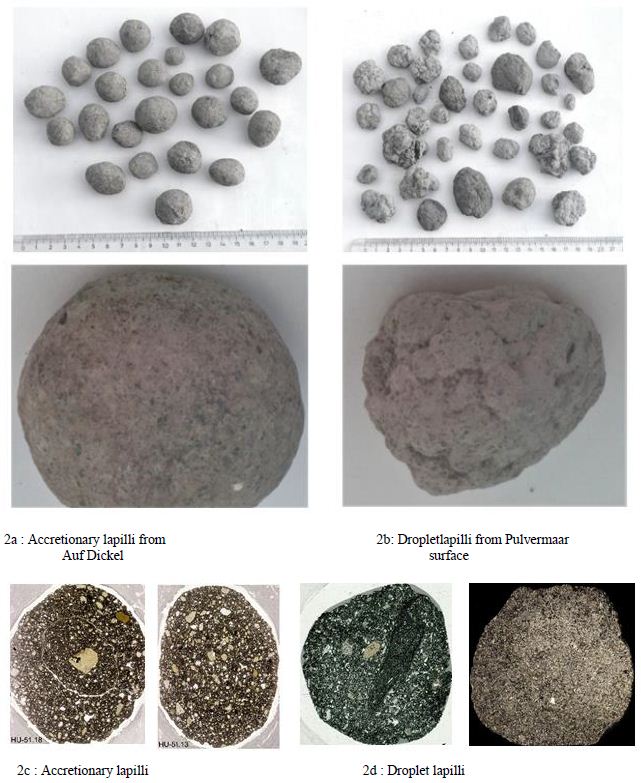

Above the evaporation zone, turbulence can occur within the ascent channel if the appropriate conditions for flow velocity and pressure are present, leading to the formation of a fluidized bed. This means that the diatreme is in agglomeration or granulation mode. Depending on the role played by the liquid phase involved, we obtain accretionary lapilli or droplet lapilli. Accretionary lapilli are formed when dust particles collect in a rotating gas flow and stick together due to a highly fluid medium (carbonatite melt). Droplet lapilli are formed when low-viscosity silicate melt (e.g. melilititic or melilite- nephelinitic) is atomized and the droplets agglomerate in the turbulent gas space. This causes the so-called “cauliflower surface” of these lapilli (Figure 2a-2b).

Figure 2:

The lapilli can occur with or without a nucleation center, with the droplet lapilli often forming around an inclusions or juxtaposed xenolith (Figure 2c-2d) with and without nucleation center (micrograph, edge length approx. 2.5 cm). If the flow conditions in the ascending channel change, the system can switch from agglomeration mode to abrasion mode. In this case, the rotating clasts transported in the conveyor chute are rounded in a similar way to a sandblasting fan. The rounded sanidine megacrysts from Rockeskyll and Hohenfels- Essingen, whose rounded surfaces have so far been interpreted as fusions, are well known (Eilhard 2018) [48]. There are also plenty of rounded accessory rock xenoliths and comagmatic clasts in the form of pyroxenites and amphibolites (Figure 3a-3b).

Figure 3:

The Problem of the Carbonatitic Binding Phase in Tephra

Ultimately, the problem of CO2 emission in carbonatitic volcanic eruptions can only be solved according to equation 2 by analyzing the binding phase of carbonatitic tephra. For this reason, we will deal with carbonatitic tephra from various volcanic regions in the following. These volcanic areas are the Eifel (EVC = Eifel Volcanic Complex), the Kaiserstuhl (KVC = Kaiserstuhl Volcanic Complex) and El Hierro (EHSR = El Hierro South Rift).

Sample Material from the EVC

The sample material comes from both the Eastern Eifel (EEVC) and the Western Eifel (WEVC).

In detail, the samples are as follows:

68.3 Tephra, EEVC, Thürer Wald

101.5 subvolcanic soevite, EEVC, Thürer Wald

101.6 Sövite, carbonatitic vein, EEVC, Thürer Wald

94.1 Tephra, WEVC, Essinger Maar

94.5 Tephra, WEVC, Essinger Maar

94.6 Tephra, WEVC, Essinger Maar

95.1 Tephra WEVC, Pulvermaar

Material 101.5 and 101.6 are subvolcanic carbonatites. Figures 4a and 4b provide a visual impression.

Figure 4:

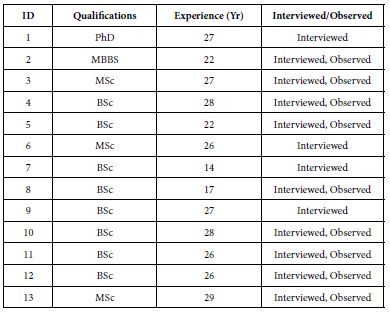

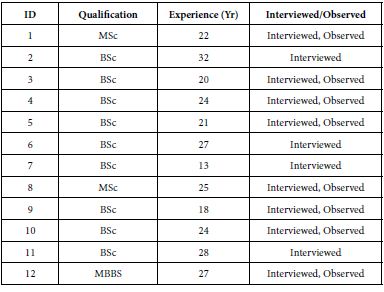

The isotope signature can be used as a starting point (Table 1):

These data are typical for magmatic carbonatites. We will find comparable data in the subvolcanic soevites of the Kaiserstuhl.

Table 1: Isotope signature.

| |

δ44Ca

|

δ13C |

δ18O |

87Sr/86Sr |

Sr/μg g-1 |

| 101.5 |

– |

-6,12 |

7,52 |

0,70442 |

14990

|

|

101.6

|

– |

-5,79 |

7,53 |

0,70439 |

15060

|

Description of the Sample Material

Tephra Thürer Wald, Sample 68.3

The volcanic clastics are cemented by a zeolitic-carbonatitic binding phase. As a result of a syneruptive or posteruptive hydrothermal phase. The geochemical data of the carbonatitic phase are listed in the following table (Table 2).

Table 2: Geochemical data of the carbonatitic phase.

|

|

δ44Ca

|

δ13C |

δ18O |

87Sr/86Sr |

Sr/μg g-1 |

| 68.3 |

– |

-7,54 |

21,68 |

0,70442 |

3500

|

The oxygen signature indicates that the fluid phase was under the influence of vadose waters, with the magmatic signature of carbon and Sr preserved.

Tephra Essinger Maar, Sample 94.1/5/6 and Tephra Pulvermaar, Sample 95.1

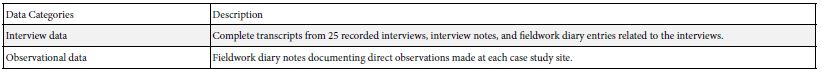

They show the volcanic clastics embedded in a carbonatitic binding phase, whose isotopic signature is shown in the following table (Table 3 and Figure 5a-5c).

Table 3: Volcanic clastics embedded in a carbonatitic binding phase.

| |

δ44Ca

|

δ13C |

δ18O |

87Sr/86Sr |

Sr/μg g-1 |

|

94.1

|

– |

-17,94 |

19,47 |

0,70594 |

800 |

| 94.5 |

0,53 |

-13,32 |

22,18 |

0,70645 |

410

|

|

94.6

|

0,59 |

-20,35 |

19,51 |

0,70613 |

1900

|

|

95.1

|

– |

-12,64 |

25,60 |

0,70603 |

1900

|

Figure 5: The tephra of the Essinger Maar is shown in a-c.

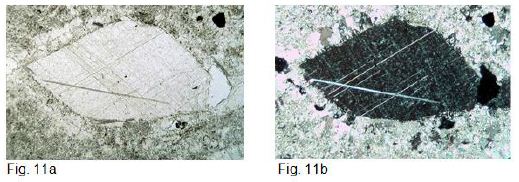

The direct indication of the magmatic origin of the Eifel tephra is provided by the high Sr content. The Sr content of sedimentary limestones of the Eifel is max. 300 ppm. The C and O isotopy of the carbonate tephra binding phase can no longer represent the Taylor criteria for magmatic isotopy [46] due to its origin. The strontium content of the carbonate binding phase was determined at the tephra of the three localities EM, PM and TW using the ICP-OES method. The tephra of the Pulvermaar is not yet diagenetically consolidated due to its young age. The CaCO3 appears as an outer coating on the tephra particles, as demonstrated in the Figure 6.

Figure 6: Tephra from the Pulvermaar.

The figure shows the state of the tephra of the Pulvermaar on the left and the state after treatment with diluted acetic acid on the right. The CaCO3 coating has been removed in this case. However, this means that the tephra particles were embedded in the dusty fallout of CaO, Ca(OH)2 and CaCO3 and not in a liquid binding phase of CaCO3 melt.

Sample Material from KVC

The material was collected in 2023 and then processed. In detail, the samples are as follows:

Sample. Remarks.

69.1. subvolcanic sövite, Badloch

97.2 Droplet lapilli, Kirchberg

105.1. Droplet lapilli, Henkenberg

105.4 Droplet lapilli, Henkenberg

105.5 white tephra, Henkenberg

105.6 hydrothermal limestone, Henkenberg

105.9 gray tephra, Henkenberg

105.10 gray tephra, Henkenberg

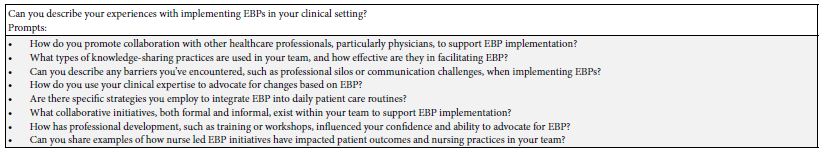

Sample 69.1 is the reference value for the initial magma with the following isotope ratios (Table 4):

Table 4: The reference value for the initial magma with isotope ratios.

|

δ44Ca

|

δ13C |

δ18O |

87Sr/86Sr |

Sr/μg g-1 |

| 0,60- |

-6,05 |

7,08 |

0,70357 |

0,70357

|

Description of the Sample Material

Droplet lapilli from Kirchberg, 97.2.

Figures 7a and 7b provide a visual impression of the sample material. The scale in mm is indicated at the bottom of the images. Figure 7b clearly shows the spherical shape of the droplets (droplet), which indicates that they were deposited in a solid state.

Figure 7a and b: Droplet lapilli from Kirchberg.

The isotope data are as follows (Table 5):

Table 5: Isotope data.

|

δ44Ca

|

δ13C |

δ18O |

87Sr/86Sr |

Sr/μg g-1 |

| 0,48 |

-7,92 |

15,53 |

0,70354 |

4690

|

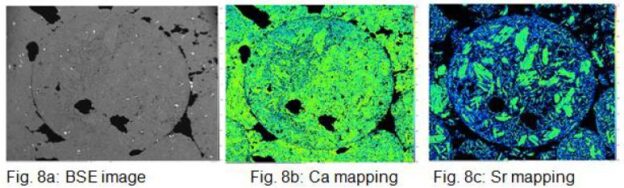

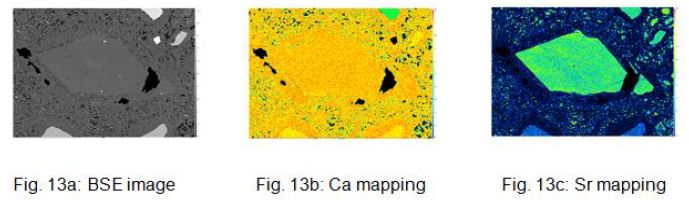

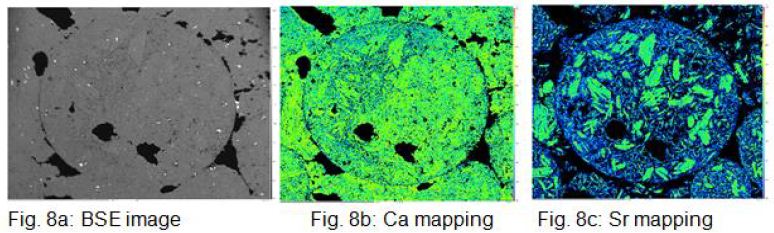

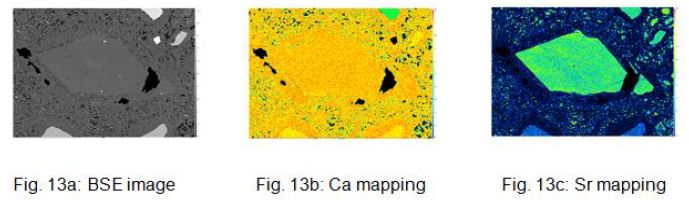

Figures 8a, b and c show the BSE image and the Ca and Sr element distribution mapping of a droplet. The Sr- mapping shows very nicely large Ca primary crystals floating in a matrix of fine crystalline CaCO3, which can be interpreted as residual solidification.

A pronounced carbonatitic binding phase similar to that of the Thürer Wald sample material is not present. This is also confirmed by comparing the δ13C values of the whole rock (wr) and the isolated droplet, which are almost identical (see Hubberten 1988 [49] Hay and O’Neil 1983 [50] and table 10.

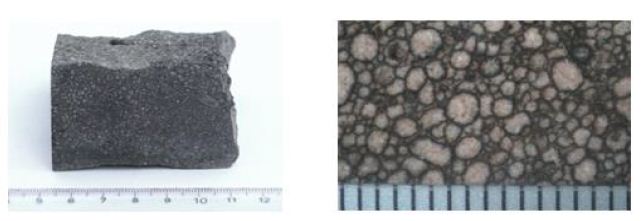

Droplet Lapilli vom Henkenberg, 105.1 and 105.4.

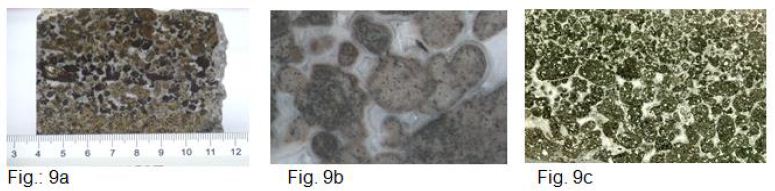

A striking feature of Figure 9a is the occurrence of light (Dl) and dark (Dd) droplets in the center of the image, embedded in a strongly developed carbonate phase (M). Detailed examinations of the microstructural components (see pictures) reveal the following picture (Table 6).

Table 6: Detailed examinations of the microstructural components.

| |

δ44Ca

|

δ13C |

δ18O |

87Sr/86Sr |

Sr/μg g-1 |

|

Dd dark

|

0,66 |

-7,91 |

14,66 |

0,70376 |

3450

|

| Dl light |

–

|

–9,43 |

15,67 |

0,70376 |

3450 |

|

Matrix

|

0,80 |

-11,57 |

24,6 |

– |

<NWG

|

Figure 9: a, b and c provide an optical impression of the sample material. Figure c shows a micrograph.

The absence of strontium and the high δ18O value of 24.6 ‰, as well as the occurrence of drusen spaces with calcite crystals in the matrix (9b) indicate a hydrothermal post-phase with vadose waters, which also explains the partial alteration of the magnetites and the associated brown coloration of part of the droplets.

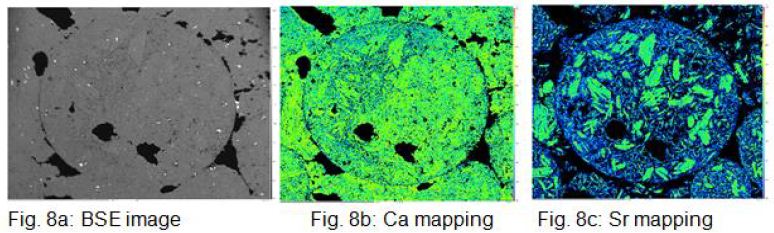

Siliceous tephra from Henkenberg, 105.9 and 105. 10.

Figure 10 gives an optical impression of the tephra. 84% of the material consists of CaCO3 . In addition, fragments of silicate minerals such as olivine, pyroxene, Al-Ca-Fe-containing garnet and Mg-Al-Ti- containing iron spinel occur.

Figure 10: 84% of the material consist of CaCO3. In addition fragments of silicate minerals such as olivin, pyroxene, Al-Ca-fe containing garnets and Mg-Al-Ti containing spinel occur.

The isotope data are as follows (Table 7):

Table 7: Isotope data.

|

Sample

|

δ44Ca

|

δ13C |

δ18O |

87Sr/86Sr |

Sr/μg g-1 |

| 105.9 |

0,42 |

-10,02 |

24,02 |

0,70477 |

281

|

|

105.10

|

0,80 |

-10,26 |

23,95 |

0,70485 |

239

|

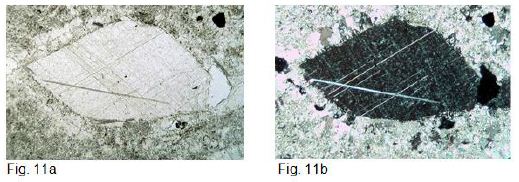

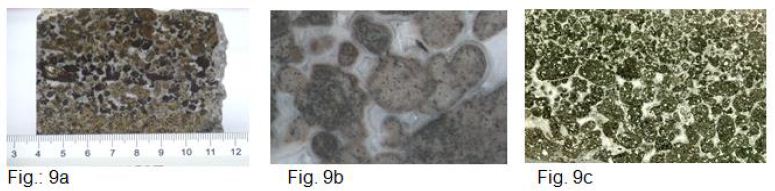

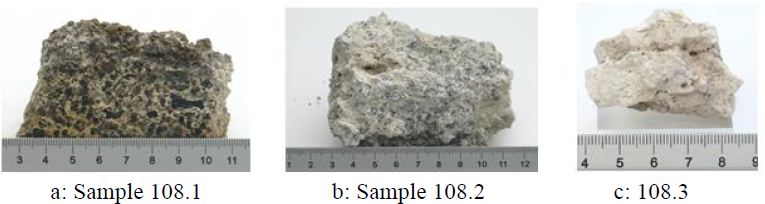

Remarkable is the occurrence of calcite crystal fragments, with strontium contents of approx. 3000 μg g-1, which are interpreted as ejected primary crystal fragments from the carbonatitic magma (Figure 11a-b, 12a-b, and 13a-c).

Figure 11: a and b shows an 800 µm x 450 µm primary crystal fragment in thin section. Figure a parallel polarizers, figure b crossed polarizers. It can be clearly seen that the calcite matrix has recrystallized at the edge of the primary crystal fragment. The grain size of this edge is up to 100 µm in contrast to the matrix, which has a grain size of approx. 15 µm. The same proportions can also be seen on the primary crystal fragments of garnet and spinel in Fig. 12 a and b.

Figure 12:

Figure 13: a, b and c show the BSE image and the Ca and Sr mappings of the calcite xenolith.

Silicate-free tephra from Henkenberg, 105.5.

The material consists of 99% CaCO3 . Figure 15 gives a visual impression of the sample material (Figure 14).

Figure 14: Silicate-free tephra.

The isotope data are as follows (Table 8):

Table 8: Isotope data.

|

Sample

|

δ44Ca

|

δ13C |

δ18O |

87Sr/86Sr |

Sr/μg g-1 |

| 105.5 |

1,03 |

-9,82 |

24,42 |

0,70656 |

68

|

The thin section shows a uniform growth structure with grain sizes of 20µm to 50µm. No foreign mineral phases are recognizable (Figure 15).

Figure 15: Thin section of sample 105.5.

The results of samples 105.5, 105.9 and 105.10 can be easily explained if one assumes that CaO and CO2 are erupted during a carbonatitic volcanic eruption and that the reactions take place according to equations 2 to 5.

During the eruption, CaO dust is blown into the atmosphere, which gradually sediments again. Coarser particles, such as mineral fragments and calcite clasts, are also deposited near the eruption site, as can be seen in material 105.9 and 105.10. The heavy SrO is also deposited near the eruption site. The material of sample 105.5 was transported further, making it xenolith-free, as the heavy crystal fragments sediment near the eruption site. Similarly, the strontium content decreases with distance from the eruption site. The material from Badloch has a strontium content of 9300 μg g-1, material 105.9/10 has a strontium content of 280 μg g-1 and material 105.5 of 68 μg g-1. The xenolith crystals of samples 105.9/10 act as nucleation centers for carbonate formation, as can be clearly seen.

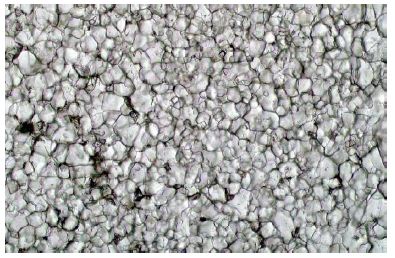

Sample Material from EHSR

The find situation can be seen in Figures 16 and 17.

The discovery points are approx. 3 kilometers apart.

Figure 16: Finding point sample 108.1.

Figure 17: Finding point samples 108.2 and 108.3

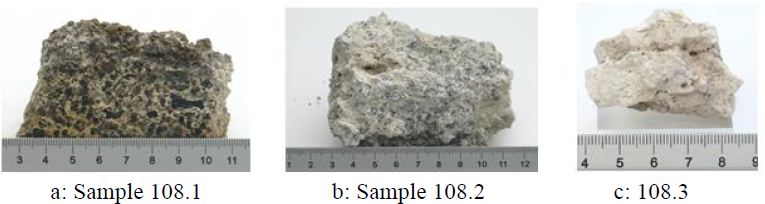

Description of the Sample Material

The geochemical data is shown in the table (Table 9 and Figure 18a-c). These three tephras are not yet strongly diagenetically consolidated. As a result, surface waters can exert a strong altering influence. Nevertheless, the tephras show a clear magmatic signature, the C and O isotope values are shifted in the sense of Hay and O’Neil towards carbonates in equilibrium with meteoric water [50]. The 14C isotope analysis has shown that a considerable 14C content is present, which correlates with ages of 9000 and 4000 years. These ages represent maximum values, as the dilution effect of the natural air CO2 content by the volcanic CO2 means that the initial value of 14C is lower than is normally assumed. In any case, the detection of 14C in the tephra confirms the sequence of reactions according to equations 2 to 5.

Table 9: Geochemical data.

|

sample

|

δ44Ca

|

δ13C |

δ18O |

87Sr/86Sr |

Sr/μg g-1 |

14C |

| 108.1 |

0,79 |

-7,71 |

28,55 |

0,70390 |

980 |

0,5497

|

|

108.2

|

0,91 |

-8,931 |

28,12 |

0,70373 |

1100 |

n.d. |

| 108.3 |

1,41 |

-8,832 |

29,24 |

0,70464 |

494 |

0,3262

|

Figure 18: a to c provide an impression of the sample material.

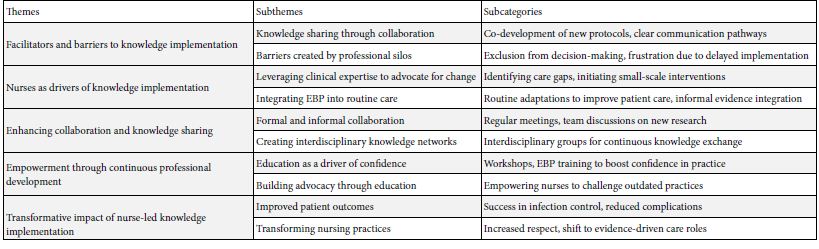

Results and Discussion

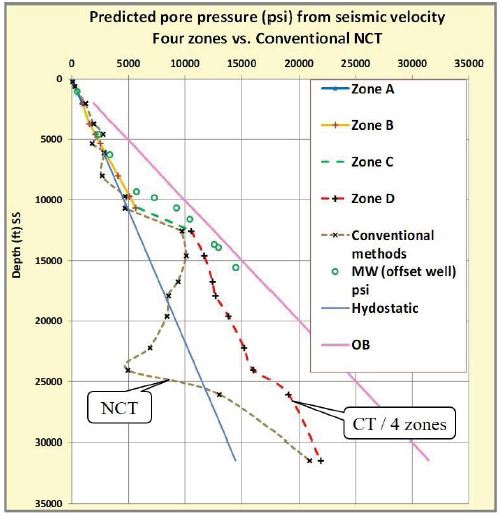

It can be seen that the δ18O value of the carbonatitic binder phase is generally greater than 20 ‰. Obviously, the δ18O value of the carbonatitic source materials (CaO and CO2) changes under the influence of atmospheric oxygen (δ18O = 23.5 ‰) in the eruption cloud to these high values of δ18O > 20‰ (Table 10).

Table 10: Summarizes the results of the tephra data.

|

Sample

|

Location |

age/Ma |

Sr/μg g-1 |

δ13C |

δ18O |

87Sr/86Sr |

δ44Ca |

| 68.3 |

TW |

0,44 |

3500_ic |

-7,54 |

21,68 |

0,70442 |

n.d.

|

|

94.1

|

EM |

0,47 |

800_ic |

-17,94 |

19,47 |

0,70594 |

n.d. |

| 94.5 |

EM |

0,47 |

410_ic |

-13,32 |

22,18 |

0,70645 |

0,53

|

|

94.6

|

EM |

0,47 |

1900_ic |

-20,35 |

19,51 |

0,70613 |

0,59 |

| 95.1 |

PM |

0,03 |

1900_ic |

-12,64 |

25,6 |

0,70603 |

n.d.

|

|

105.5

|

KS/HB |

16,4 |

68_ic |

-9,822 |

24,42 |

0,70656 |

1,03 |

| 105.9 |

KS/HB |

16,4 |

281_ic |

-10,02 |

24,02 |

0,70477 |

0,42

|

|

105.10

|

KS/HB |

16,4 |

238_ic |

-10,26 |

23,95 |

0,70458 |

0,8 |

| 97.2 |

KS/K |

16,4 |

4690_wr |

-7,92 |

15,53 |

0,70354 |

0,48

|

|

105.1/GLD

|

KS/HB |

16,4 |

3450 |

-7,91 |

14,66 |

0,70376 |

0,66 |

| 105.1/GLH |

KS/HB |

16,4 |

3450 |

-9,43 |

15,67 |

0,70376

|

|

|

105.1/M

|

KS/HB |

16,4 |

<NWG |

-11,57 |

24,6 |

|

0,8 |

| wr |

KS/K |

16,4 |

n.d. |

-7,6 |

16,9 |

|

Data from [49]

|

|

wr

|

KS/K |

16,4 |

n.d. |

-7,8 |

15,7 |

|

Data from [49] |

| isolated lapilli |

KS/K |

16,4 |

n.d. |

-7,1 |

15,6 |

|

Data from [49]

|

|

isolated lapilli

|

KS/HB |

16,4 |

n.d. |

-8,8 |

15 |

|

Data from [49] |

| M |

KS/HB |

16,4 |

n.d. |

-10,4 |

24,6 |

|

Data from [49]

|

|

M

|

KS/HB |

16,4 |

n.d. |

-10,2 |

24,7 |

|

Data from [49] |

| M |

KS/HB |

16,4 |

n.d. |

-10,2 |

24,6 |

|

Data from [49]

|

|

GL

|

KS/HB |

16,4 |

3500 |

-9,3 |

13,9 |

Data from [50] |

Data from [50] |

| GL |

KS/HB |

16,4 |

3500 |

-9,2 |

14,3 |

Data from [50] |

Data from [50]

|

|

GL

|

KS/HB |

16,4 |

3500 |

-8,4 |

14,7 |

Data from [50] |

Data from [50] |

| M |

KS/HB |

16,4 |

<NWG |

-17,7 |

20,6 |

Data from [50] |

Data from [50]

|

|

M

|

KS/HB |

16,4 |

<NWG |

-12,1 |

23 |

Data from [50] |

Data from [50] |

| 108.1 |

El_H |

0,003 |

980_ic |

-7,71 |

28,55 |

0,70390 |

0,79

|

|

108.2

|

EL_H |

0,003 |

1100_ic |

-8,931 |

28,12 |

0,70373 |

0,91 |

| 108.3 |

El_H |

0,003 |

494_wr |

-8,832 |

29,24 |

0,70464 |

1,41

|

Ic: isolated carbonate, wr: whole rock, n.d.: not detected.

The δ13C value does not change during the eruption as it lacks the exchange partner and the small amount of CO2 in the air also has a δ13 C value of -6.5‰. This means that the change in the δ C value of the tuffitic binding phase is due to later alteration. This can be seen very clearly in the tephra of El Hierro, which can be regarded as recent at around 3 ta and which still fulfills the Taylor criterion for carbon with values of δ13C of around -8‰, while the oxygen is already far from this with values of 28 ‰. This shows that the C isotope ratio will be changed by alteration processes after the eruption. However, the lapilli tephra from Kaiserstuhl also shows that the isotopic composition δ13C of massive carbonatite, as present in the lapilli, is much more stable than the δ18O isotopy. The values in the table also show that in cases where the δ13C isotope does not deviate or deviates only slightly from the Taylor criterion, the 87Sr/86Sr value has a magmatic signature. The formation of the droplet lapilli at Kirchberg and Henkenberg must have taken place under conditions that are extremely rarely realized in nature. This shows that only three such sites are currently known: Kaiserstuhl [51], Cape Verde Islands [37] and Fort Portal Volcanic Field, Uganda (Barker and Nixon 1988 [38]). The carbonate melt must have spattered. It then formed into a sphere due to the surface tension and suddenly solidified. Accordingly, the micrographs Figure 8c show calcite primary crystals precipitated from the melt and a fine-grained matrix as residual solidification.

Figure 8: a, b and c show the BSE image and the Ca and Sr element distribution mapping of a droplet. The Sr- mapping shows very nicely large Ca primary crystals floating in a matrix of fine crystalline CaCO3 , which can be interpreted as residual solidification.

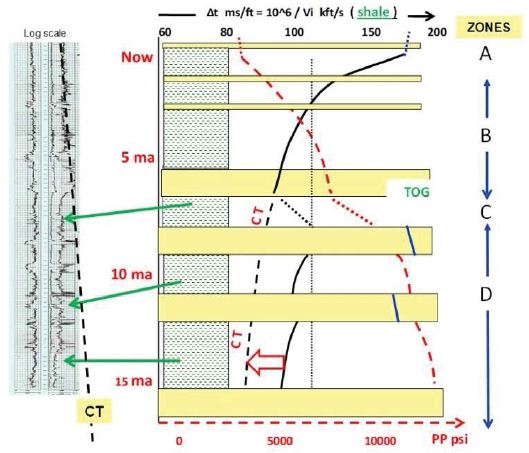

The synthesis of physical data on the pressure- and temperature- dependent phase relationships in the CaCO3 system and the findings on the dissolution behaviour of CaCO3 and H2O in silicate melts and their influence on the density and fluidity of the melts under consideration, as well as the calculation of the associated ascent rates, allow conclusions to be drawn about the eruption behaviour in diatremes. Diatremes are bound to tectonically predetermined structures that allow the highly fluid melts to rise rapidly and thus leave them no time to cool. If the melts reach the pressure range that results in the decomposition of the CaCO3 or the release of the CO2, a gigantic fan is created that opens the vent to the Earth’s surface by fragmenting the overlying cover, which explains the high content of wall rock xenoliths in the diatreme. If one now takes into account the phenomena known from technology that are associated with the transport of particles in flowing gases (fluidisation), then the tephras of volcanic pipes that can be found in the terrain can be easily explained. Furthermore, the detection of the carbon isotope 14C in carbonatitic tephra confirms the dissociation and recombination of CaCO3 during the eruption. For the Eifel, this means that the formation of the maars exclusively by phreatomagmatic processes must be reconsidered. This concept was already criticised in the work of Rausch et al. (2015) [52], but was only included in the work of Schmincke et al (2022) [53], in which the formation of maars in the Eifel by sudden magma degassing is also considered possible.

Acknowledgement

We would like to thank A.Pack, Georg-August University of Göttingen for massive support at measuring the oxygen und carbon isotopy. We would also like to thank L. Viereck for valuable advice during the preparation of the manuscript.

References

- Woolley AR, Kjarsgaard BA (2008) Paragenetic types of carbonatite as indicated by the diversity and relative abundances of associated silicate rocks: evidence from a global The Canadian Mineralogist . 46 : 741-752.

- Jones AP, Genge M, Carmody L (2013) Carbonate Melts and Reviews in Mineralogy & Geochemistry. 75 : 289-322.

- Irving AJ, Wyllie PJ (1975) Subsolidus and melting relationships for calcite, magnesite and the join CaCO3-MgCO3 to 36 Geochim. Cosmochim. Acta 39 : 35-53.

- Shatskiy AF, Litasow KD, Palyanov YN (2015) Phase relations in carbonate systems at pressures and temperatures of lithospheric mantle: review of experimental data. Russian Geology and Geophysics. 56 : 113-142.

- Huang WL, Wyllie PJ (1976) Melting relationships in the systems CaO-CO2 and MgO-CO2 to 33 Geochim. Cosmochim. Acta. 40 : 129-132.

- Eggler DH (1974) Effect of CO2 on the melting of peridotite. Carnegie Inst. Yearb. 73 : 215-224.

- Zimanowski B (1985) Fragmentationsprozesse beim explosiven Vulkanismus in der Diss. Univ. Mainz, 251S. 64 Abb., 30 Tab., Mainz 1985.

- Stoppa F, Lloyd FE, Rosatelli G (2003) CO2 as the propellant of carbonatite-kamafugite cognate pairs and the eruption of diatreme tuffisite. Mineral. 72 : 205-222.

- Schmincke H-U (2007) The quaternary volcanic fields of the East and West Eifel (Germany). – In: Ritter R, Christensen U (Hrsg), Mantle Plumes – A Multidisciplinary Springer, Heidelberg. 241-322

- Bogaard van den P & Schmincke H-U (1990) Die Entwicklungsgeschichte des Mittelrheinraumes und die Eruptionsgeschichte des Osteifel-Vulkanfeldes. In: Schirmer W (Hrsg) Rheingeschichte zwischen Mosel und Maas. DEUQUA-Führer 1, Deutsche Quartärvereinigung, Hannover. 166-190.

- Mertz DF, Löhnertz W, Nomade S, Pereira A, Prelevic D, et al. (2015) Temporal- spatial evolution of low-SiO2 volcanism in the Pleistocene West Eifel volcanic field (west Germany) and relationship to upwelling Journal of Geodynamics 88 : 59-79.

- Zolitschka B, Negendank JFW, Lottermoser BG (1995) Sedimentological proof and dating of the early Holocene volcanic eruption of Ulmener Maar (Vulkaneifel, Germany). Rdsch. 84 : 213-219.

- Reinig F, Wacker L, Jöris O, Oppenheimer C, Guidobaldi G, et (2021) Precise date for the Laacher See eruption synchronizes the Younger Dryas. Nature. 595 : 66-69.

- Mertes H (1983) Aubau und Genese des Westeifeler Vulkanfeldes. Bochum. Geotech. Arb. 9 : 1-415.

- Mertes H, Schmincke H-U (1984) Age distribution of volcanoes in the West-Eifel. Jb. Geol. Paläont. Abh. 166 : 260-283.

- Mertes H, Schmincke H-U (1985) Petrology of potassic mafic magmas of the Westeifel volcanic Major and trace elements. Contrib. Mineral. Petrol. 89 : 330-345.

- A Brauns R (1925) Ein Carbonatit aus dem Laacher Seegebiet. Centralblatt für Mineralogie, Geologie und Paläontologie, A4, 97-101.

- Brauns R (1934) Ein neuartiges Skapolithgestein aus dem Laacher Seegebiet mit kurzer Uebersicht ueber die Laacher Auswürflinge und der Bedeutung der fluechtigen Bestandteile im Magma fuer deren Bildung und Centr. Miner. Abt.A. 3: 65-72.

- Schuster E (1920) Calcitführende Auswürflinge aus dem Laacher Seegebiet. Neues Jahrbuch für 4 : 295-318.

- Lloyd FE, Bailey DK (1969) Carbonatite in the tuffs oft he West Eifel,Germany. Mineral. Petrol. 23 : 136-139.

- Riley TR, Bailey DK, Lloyd FE (1996) Extrusive carbonatite from the quaternary Rockeskyll complex, West Eifel, The Canadian Mineralogist 34 : 389-401

- Riley TR, Bailey DK, Harmer RE, Liebsch H, Lloyd FE, et al. (1999) Isotopic and geochemical investigation of a carbonatite-syenite-phonolite diatreme, West Eifel (Germany). Mineralogical Magazine 63 : 615-631.

- Liebsch H (1996) Die Genese der Laacher See-Karbonatite. Thesis PHD, Göttingen 1996, ISBN 3-932325-06-0.

- Schmitt AK, Wetzel F, Cooper KM, Zou H, Worner G (2010) Magmatic Longevity of Laacher See Volcano (eifel, Germany) indicated by U-Th Dating of Intrusive Journal of Petrology, s1, 1053-1085.

- Viereck L (1984) Geologische und petrologische Entwicklung des pleistozänen Vulkankomplexes Rieden, Ost-Eifel. Bochumer Geologische und geotechnische Arbeiten, Herausgeber: Ruhr-Universität Bochum, 1984.

- Bogaard van den P (1995) Ar40/Ar39 ages of sanidine phenocrysts from Laacher See Tephra (12,900 yr BP) Chronostratigraphic and petrological Earth and Planetary Science Letters. 133 : 163-174.

- Frechen J (1976) Siebengebirge am Rhein – Laacher Vulkangebiet – Maargebiet der Westeifel – Vulkanisch – petrologische Exkursionen. Sammlung Geol. Führer, 4th Borntraeger, Berlin, Stuttgart, 1-195.

- Wörner G, Viereck L, Plaumann S, Pucher R, Bogaard vdP, Schmincke H-U (1988) The Quaternary Wehr Volcano: A multiphase evolved eruption center in the East Eifel volcanic field (FRG). Neues Jahrbuch Abh. 159 : 73-99.

- Meyer W (2013) Geologie der Eifel,4.Aufl., 435, ISBN 978-3-510-65279.

- Frechen J, Lippolt HJ (1965) Kalium-Argon-Daten zum Alter des Laacher Vulkanismus, der Rheinterassenund der Eiszeiten. Eiszeitalter und Gegewart.16 : 5-30.

- Keller J (1981) Carbonatitic Volcanism in the Kaiserstuhl Alkaline Complex: Evidence for Highly Fluid Carbonatitic Melts at the earth`s Surface. of Volcanology and Geoth. Reserarch. 9 : 423-431.

- Zartner S (2009) Der Kaiserstuhlkarbonatit. „Exkursion Oberrheingraben und Kaiserstuhl“ am 05.-06. Juni 2009, leitung Brügmann G, Mertz D.

- Braunger S, Marks MAW, Walter BF, Neubauer R, Reich R, et (2018)_The Petrology of the Kaiserstuhl VolcanicComplex, SW Germany: the Importance of metasomized and Oxidized Lithospheric Mantle for Carbonatite Generation. Journal of Petrology 59 : 1731-1762.

- Rapprich V, Walter BF, Kopackova-Strnadova V, Kluge T, Ceskova B, et (2023) Gravitational collapse of a volcano edifice as a trigger for explosive carbonatite eruption, The Geological Siciety of America.

- Ghobadi M, Brey GP, Gerdes A, Höfer H, Keller J (2021) Accessories in Kaiserstuhl carbonatites and related rocks as accurate and faithful recorders of whole rock age and isotopic International Journal of Earth Sciences.111 : 573-588.

- Högbom, AG (1895) Über das Nephelinsyenitgebiet auf der Insel Alnö. Fören. Stockholm Föhr. 17 : 101-115, 214-258.

- Silva LC, Le Bas MJ, Robertson AHF (1981) An oceanic carbonatite volcano on Santiago, Cape Verde Nature. 294 : 644-645.

- Barker DS, Nixon PH (1989) High-Ca, low-alkali carbonatite volcanism at Fort Portal, Contributions to Mineralogy and Petrology. 103 : 166-177.

- Carracedo JC, Troll VR (2016) The Geology of Canary Elsevier Inc.

- Abis C, Di Capua A, Marti J, Meletlidis S (2023) Geology of El Hierro Southern Rift.

- Woolsey TS, McCallum ME, Schumm SA (1975) Modelling of diatreme emplacement by Physics and Chemistry oft he Earth. 9 : 29-42.

- Gilbert JS, Lane SJ (1994) The origin of accretionary Bull. Volcanol. 56 : 398-411.

- Gernon TM, Gilbertson MA, Sparks RS, Field M (2007) Tapered Fluidized beds and the role of Fluidization in Mineral The 12th International Conference on Fluidization – New Horizons in Fluidization Engineering.

- Gernon TM, Brown RJ, Tait MA, Hincks TK (2012) The origin of pelletal lapilli in explosive kimberlite eruptions. Nature Communications 1-7.

- Genge MJ, Price GD, Jones AP (1995) Moleccular dynamics simulations of CaCO3 melts to mantle pressures and temperatures:implications for carbonatite magmas. Earth and Planetary Science Letters, 131 : 225-238.

- Taylot HP, Frechen J, Gegens ET (1967) Oxygen and carbon isotope studies of carbonatites from the Laacher See District, West Germany and the Alnö District, Geochimica et Cosmochimica Acta. 31 : 407-420.

- Demeny A, Ahiado A, Casillas R, Vennemann TW (1998) Crustal contamination and fluid/rock interaction in the carbonatites of Fuerteventura (Canary Islands, Spain): a C, O, H isotope study. Lithos 44 : 101-115.

- Eilhard N (2018) Genese der Sanidin-Megakristalle aus den Quartären Vulkanfeldern der Eifel, Deutschland. Dissertation Ruhruniversität Bochum 2018.

- Hubberten HW, Katz-Lehnert K, Keller J (1988) Carbon and Oxygen Isotope Investigations and Related Rocks from the Kaiserstuhl, Germany.

- Hay RL, O´Neil JR (1983) Carbonatite Tuffs in the Laetolil Beds of Tanzania and the Kaiserstuhl in Contrib. Mineral. Petrol. 82 : 403-406.

- Keller J (1965) Eine Tuffbreccie vom Henkenberg bei Niederrotweil und ihre Bedeutung für die Magmatologie des Kaiserstuhls.

- Rausch J, Grobety B, Volanthen P (2015) Eifel Maars: Quantitative shape characterisation of juvenile ash particles (Eifel Vlcanic Field, Germany). Journal of Volcanology and Geothermal Research. 291: 86-100.

- Schmincke H-U, Sumita M, Chakraborty S, Hansteen T (2022) The origin of maars at the type locality Eifel (Germany): H2O or CO2. (preprint).

- Jarosewich, E., MacIntyre, I.G., (1983) Carbonate reference samples for electron microprobe and scanning electron microscope analyses. Journal of Sedimentary Research. 53 : 677-678.

- Merlet C (1994) An accurate computer correction program for quantitative electron probe microanalysis. Microchimica Acta. 114-115, 363-376.

- Mollenhauer G, Grotheer H, Gentz T, Bonk E, Hrefter J (2021) Standart operation procedures and performance oft he MICDAS radiocarbon laboratory at Alfred Wegener Institute (AWI), Germany. Nuclear Instruments and Methods in Physics Research, Section B. 496 : 45-51.

- Wacker L, Christl M, Synal HA (2010) Bats: Anew tool for AMS data Nuclear Instruments and Methods in Physics Research, Section B. 268 : 976-979.