DOI: 10.31038/MIP.2021212

Abstract

CYP3A4*1B is a single nucleotide polymorphism of CYP3A4 and is associated with prostate cancer which exhibits higher nifedipine oxidase activity in liver. This research provides details of the effects of structural variation and medium effects for the recently reported split-oligonucleotide (tandem) probe system for excimers-based fluorescence detection of DNA. In this approach the detection system is split at a molecular level into signal-silent components, which must be assembled correctly into a specific 3-dimensional structure to ensure close proximity of the excimer partners and the consequent excimer fluorescence emission on excitation. The model system consists of two 11-mer oligonucleotides, complementary to adjacent sites of a 22-mer DNA target. Each oligonucleotide probe is equipped with functions able to form an excimer on correct, contiguous hybridization. The extremely rigorous structural demands for excimer formation and emission required careful structural design of partners for excimer formation, which are here described. This study demonstrates that the excimer formed emitted at ~480 nm with a large Stokes shift (~130-140 nm).

Keywords

DNA probe systems, Excimers, DNA detection, Fluorescence, CYP3A4*1B, Stokes shift

Introduction

Reversible hybridisation of complementary polynucleotides is essential to the biological processes of replication, transcription, and translation. Physical studies of nucleic acid hybridisation are required for understanding these biological processes on a molecular level. The physical characterisation of nucleic acid hybridisation is essential for predicting the performance of nucleic acids in vitro, for instance, in hybridisation assays used to detect specific polynucleotide sequences.

Fluorescence measurements present an improved sensitive measure of nucleic acid concentration compared to conventional solution-phase detection techniques. Additionally, the sensitivity of fluorophores to their environments offers a means by which to differentiate hybridised from unhybridised nucleic acids without resorting to separation techniques. This was first demonstrated by attaching different fluorescent labels to the termini of oligonucleotides, which hybridise to adjacent regions on a complementary strand of DNA. Appropriate selection of fluorophores led to a detectable signal between the labels on hybridisation of the two-labeled strands to their complementary strand. For example, split-probe systems based on excimer fluorescence were first described by Ebata [1-3], who attached pyrene to the 5′-terminus of one oligonucleotide probe and to the 3′-terminus of the other oligonucleotide probe. The probes bound to adjacent regions of the target, bringing the pyrene molecules into close proximity, forming an excimer [4,5]. Excimer emission from oligonucleotides containing 5-(1-pyrenylethynyl)uracil [6], trans-stilbene [7], and perylene [8] have also been reported.

Numerous genetic diseases have been found to result from a change of a single DNA base pair. These single nucleotide polymorphisms (SNP) may cause changes in the amino acid sequence of important proteins [9,10]. Methods sensitive to single base-pair mutations for the fast screening of patient samples to identify disease-causing mutations will be essential for diagnosis, prevention and treatment. Usually hybridisation analysis is used, where a short, probe oligonucleotide (15-20 base pairs) bearing some kind of label (e.g. fluorophore) hybridises to complementary base pairs in DNA or RNA. The nucleic acids required for analysis can be recovered from a variety of biological samples including blood, saliva, urine, stool, nasopharyngeal secretions or tissues [11-13]. Highly specific, simple, and accessible methods are needed to meet the accurate requirements of single nucleotide detection in pharmacogenomic studies, linkage analysis, and the detection of pathogens. Recently there has been a move away from radioactive labels to fluorescence.

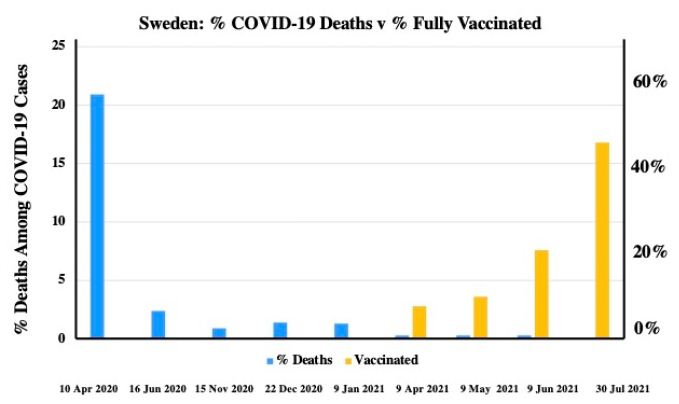

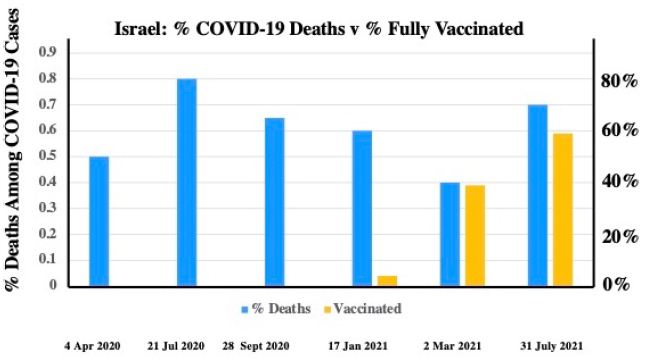

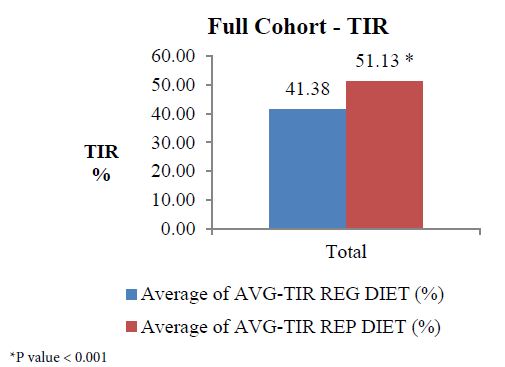

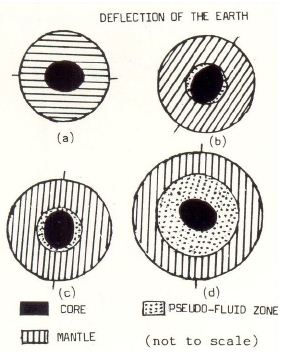

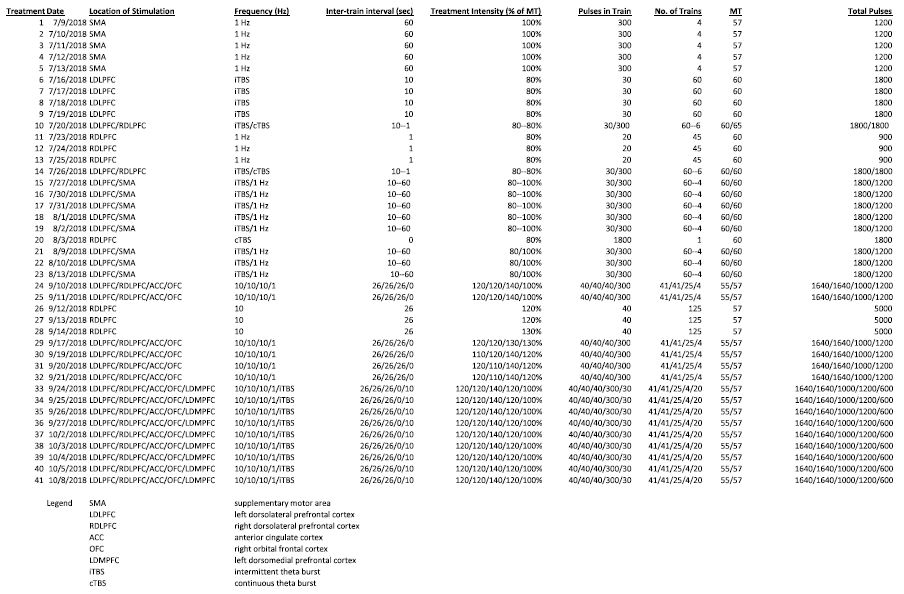

It has been reported [14] that an emissive exciplex can be formed by juxtaposition of two different externally oriented exciplex-forming partners (pyrene and naphthalene) at the interface (nick region) of tandem oligonucleotides forming a duplex of some kind on hybridization with their complementary target strand. We have been mainly interested in using excimer fluorescence signals to study the hybridisation between two fluorophore-labeled complementary DNA strands, as shown in Figure 1. Attaching fluorescent labels (pyrene and pyrene in Figure 1) to the probe of complementary DNA strands showed strong interactions between particular fluorophore pairs on hybridisation. Split-probe systems based on two 11 mer probe strands were investigated in this paper using the base sequences shown in Figure 1.

In the split-probe model system (Figure 1) two 11-mer probe oligonucleotides labelled with 1-pyrenylmethylamine (Pyrene) attached to 3′ and 5′ terminal phosphate groups. Hybridization of these probes to a complementary 22-mer oligonucleotide target resulted in correct orientation of the two pyrenes excimer-partners. Excitation of the pyrenylmethylamino partner at 350 nm led to the structure of an excited-state complex (excimer) with the pyrene partner. This excimer emitted at a longer wavelength of 480 nm (Stokes shift 130 nm) as compared with a mixture of unhybridisedsplit-probes. The excimer emission was particularly preferred by the use of trifluoroethanol as co-solvent (80 % v/v) [14].

Figure 1: Base sequences of the split-probe systems.

The split-probe model system used in this study containing 22-mer target sequence which corresponds to a region of the CYP3A4 major genome (3′-AGCGGAGAGAGGACGGGAACAG-5′) and complementary 11 mer probes(5′-TCGCCTCTCTC-pyrene and pyrene-CTGCCCTTGTC-3′). CYP3A4*1B (-392A>G, rs2740574) is a CYP3A4 polymorphism and it is the frequently studied proximal promoter variant which occurs in White human populations at around 2-9% but at elevated frequencies in Africans including Libyans [15-17]. We now report how this excimer strategy can permit detection of an allelic variant of the human CYP3A4*1B gene sequence.

Single-nucleotide polymorphisms (SNPs) in genes coding for cytochrome P450 (CYP) enzymes have been linked to many diseases and to inter-individual differences in the efficiency and toxicity of many drugs. Thirty seven CYP3A4 variants, with amino-acid changes located in coding regions, have been identified among the different ethnic populations (www.pharmvar.org/gene/CYP3A4). For example, CYP3A4*1B allele (CYP3A4-V, rs2740574), a −392A>G transition in the promoter region, has been reported to be considerably connected with HIV infection [18], increased threat of hormone negative breast cancer(missing estrogen, progesterone receptors) [19], prostate cancer [20] and increased risk for developing leukemia after epipodophyllotoxin therapy [21]. Also, theCYP3A4*1B allele causes amino acid substitution affecting the metabolism of a range of drugs such as Nifidipine and Carbamazepine which leads to altered enzyme activity and drug sensitivity, e.g. the mutant enzyme results in impaired metabolism [22,23].

Materials and Methods

The excimer constructs used standard DNA base/sugar structures in both complementary probes. The targets were a part of the CYP3A4 chromosome 7 sequence band q22.1 (Genbankcode[ENSG00000160868 nucleotides r=7:99354604-99381888]: 3′-AGCGGAGAGAGGACGGGAACAG-5′ (the bold base provided the SNP location G>A). The ExciProbes had the sequence (X1) p-5′-CTGCCCTTGTC-3′ and (X2) 5′-TCGCCTCTCTC-3′-p. The probes were supplied with a free 3’ or 5’-phosphate group (p). Reagents of the highest quality available and DNA probes and DNA targets were purchased from Sigma-Aldrich (Paris France,). Distilled water was further purified by ion exchange and charcoal using a MilliQ system (Millipore Ltd, UK). Tris buffer was prepared from analytical reagent grade materials. pH was measured using a Hanna(Lisbon, Portugal)HI 9321 microprocessor pH meter, calibrated with standard buffers (Sigma-Aldrich) at 20°C.

HPLC

HPLC purification of probes was performed on an Agilent 1100 Series HPLC system (California, USA), consisting of a quaternary pump with solvent degasser, a diode-array module for multi-wavelength signal detection using an Agilent 1100 Series UV-visible detector and an Agilent 1100 Series fluorescence detector for on-line acquisition of excitation/emission spectra. The system had a manual injector and thermostatted column compartment with two heat exchangers for solvent pre-heating. The HPLC system was operated by Agilent HPLC 2D ChemStation Software. Depending on the purification performed, the columns used were: Zorbax Eclipse X DB-C8 column (California, USA) (length 25 cm, inner diameter 4.6 mm, particle size 5μm), or a Luna C18 (2) column (California, USA) (length 25 cm, inner diameter 4.6 mm, particle size 5 μm) with elution using an increasing gradient (0–50%) of acetonitrile in water (fraction detection at 260, 280, and 340 nm).

UV-Visible Spectrophotometry

UV–visible absorption spectra were measured at 20°C on a Cary-Varian 1E UV–visible spectrophotometer (London, UK.) with a Peltier-thermostatted cuvette holder and Cary 1E operating system/2 (version 3) and CARY1 software. Quantification of the oligonucleotide components used millimolar extinction coefficients (e260) of 99.0 for ExciProbe (X1), 94.6 for ExciProbe (X2). The extinction coefficients were calculated by the nearest neighbour method [24] and the contribution of the exci-partners was neglected.

Spectrophotofluorimetry

Fluorescence emission/excitation spectra were recorded in 4-sided quartz thermostatted cuvettes using a Peltier-controlled-temperature Cary-Eclipse, spectrofluorophotometer (London, UK). All experiments were carried out at 5°C. Hybridisation: Duplex formation was induced by sequential addition of ExciProbe(X1) and ExciProbe (X2). The mole ratio of all oligonucleotides ExciProbe (X1)and ExciProbe (X2) used were 1:1, the concentration of each component was2.5 µM. Tris buffer was added either with or without 80% TFE and thevolume made up to 1000 µl with deionized water. Excitation wavelengths of 340 nm (for the pyrene monomer) and 350 nm (for the full two probes and the target) were used, at slit width of5 nm and recorded in the range of 350-650 nm. Emission spectra were recorded after each sequential addition of each component to record the change in emission of each addition. A baseline spectrum of buffer and water or buffer, water and 80% TFE was always carried out before start of the measurement. After each addition the solution was left to equilibrate for 6 minutes in the fluorescence spectrophotometer and emission spectra were recorded until no change in the fluorescence spectra was seen to ensure it had been reached. The sequence of experiments was first using ExciProbe (X1) then ExciProbe (X2). Control experiments were conducted using firstly ExciProbe (X1) followed by the 3’-free oligonucleotide probe and finally the complementary target. All spectra were buffer corrected.

Control Experiments

Control experiments were carried out in 80% TFE/Tris buffer as for the experimental systems using the standard method described above. The control experiment was performed to confirm whether the obtained excimer emission is a result of such background effects or arise from the hypothesised excimer structures. Then fluorescence melting curve experiments (based on excitation 350 nm and emission 480 nm for the excimer) were performed using a Cary Eclipse fluorescence spectrophotometer by measuring the change in fluorescence intensity for the excimer with melting temperature(Tm). Tm was also determined spectrophotometrically by measuring the change in absorbance at 260 nm with temperature. Tm was determined either by taking the point at half the curve height or using the first derivative method.

Synthesis and Oligonucleotide Modification

Attachments of 1-pyrenemethylamine to oligonucleotide probes were as described in [14,25]. One equivalent of 1-pyrenemethylamine was attached via phosphoramide links to the terminal 5’-phosphate of (X1) p-5′-CTGCCCTTGTC-3′ probe and to the 3’-phosphate of (X2) 5′-TCGCCTCTCTC-3′-p. To the cetyltrimethyl ammonium salts of the oligonucleotides (~1 micromole) dissolved in N, N-dimethylformamide (200 µl) were added triphenyl phosphine (80 mg, 300 µmol) and 2,2′-dipyridyl disulfide (70 mg, 318 µmol), and the reaction mixture was incubated at 37°C for 10 min. 4-N’,N’-Dimethylaminopyridine (40 mg, 329 µmol) was added, the reaction mixture incubated for a further 12 minutes at 37°C and 1-pyrenemethylamine hydrochloride (4 mg, 14.9 μmol, dissolved in 100 µl of N, N-dimethylformamide and three microliter triethylamine) added. The mixture of the reaction was incubated at 37°C for full day (24 hours) product then was purified using reverse-phase HPLC (eluted by 0.05 M LiClO4 with a gradient from 0 to 60 % acetonitrile).

CYP3A4*1B Single Nucleotide Polymorphism

Split-probe systems were used to investigate the effect of SNP in the CYP3A4*1B target sequence on excimer emission compared to the normal-type target. Experiment was carried out in 80% TFE/Tris buffer at 5°C. The sequence of addition was: ExciProbe (X1), ExciProbe (X2), and finally 22 mer mutant-target oligonucleotide (CYP3A4*1B). All spectra were buffer-corrected.

Results

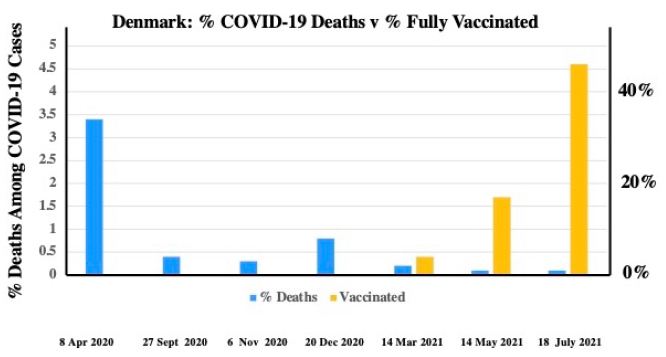

Excimer Formation Using Terminally Located Probe Systems

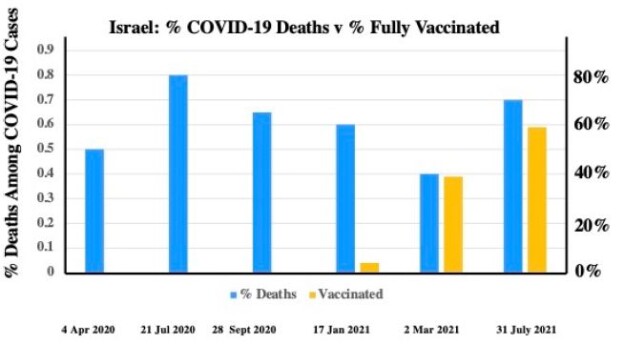

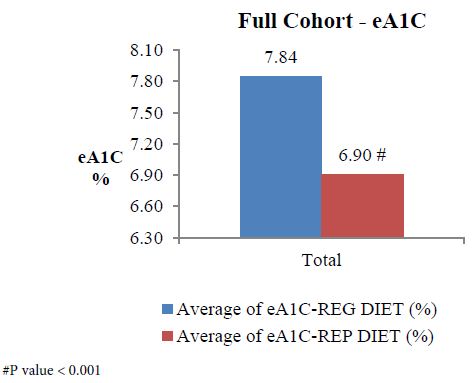

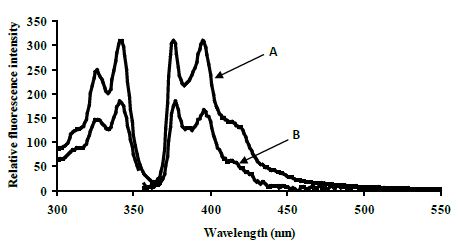

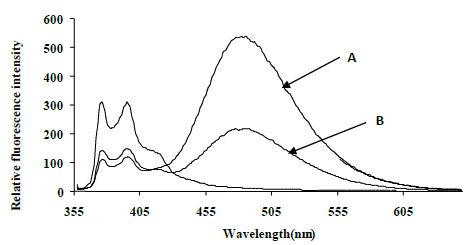

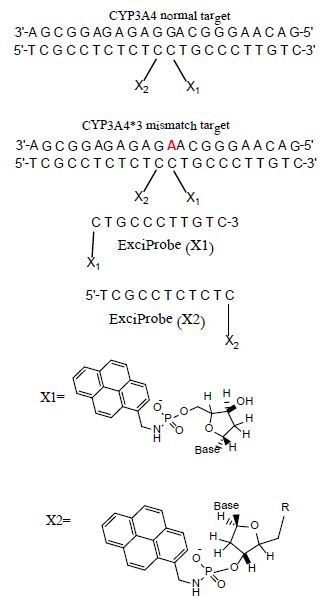

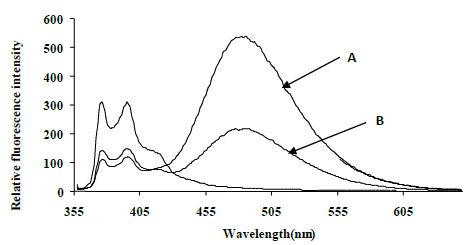

Fluorescence studies were made for solutions of ExciProbe (X1) and ExciProbe (X2) oligonucleotides with both probes complementary to each other (Figure 1). Figure 2 shows the excitation and emission spectra for (A) the ExciProbe (X1) and ExciProbe (X2) in 80% TFE/Tris buffer (0.01 M Tris, 0.1 M NaCl, pH 8.4), at5°C, (B) ExciProbe (X1) and ExciProbe (X2) hybridised to the 22-mer target oligonucleotide. On excitation at 350 nm, the 3′-pyrenyl ExciProbe (X1) and 5′-pyrenyl ExciProbe (X2) showed fluorescence typical of pyrene LES emission (lmax = 376, 395 nm). Addition of the complementary target resulted in immediate quenching of the LES emission at 395 nm to less than one-third of its original value and the appearance of a new, broad emission band (lmax = 480 nm) characteristic of pyrene excimer fluorescence after the full terminally located system had formed)[1,2,26]. Addition of the two probes to the target also caused a slight red shift in both excitation (from 342 nm to 349 nm) and emission (from 376 nm to 378 nm; λex 350 nm) spectra, consistent with duplex formation [1,2,26].

Figure 2: Excitation and emission spectra of the split-oligonucleotide (tandem) probe system A 5′-pyrenyl ExciProbe (X1) and 3′-pyrenyl ExciProbe (X2), B ExciProbe (X1), 3′-pyrenyl ExciProbe (X2) and the complementary target (full system)in 80% TFE/0.01 M Tris, 0.1 M NaCl, pH 8.4) at 5°C. Component concentrations were 2.5 μM (equimolar).

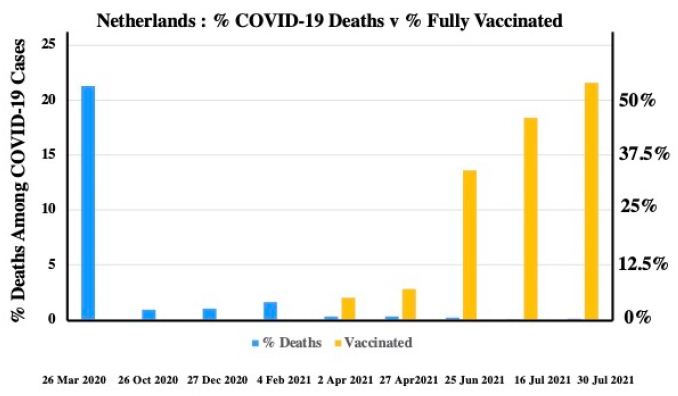

Control Experiments for the Terminally Located Excimer System

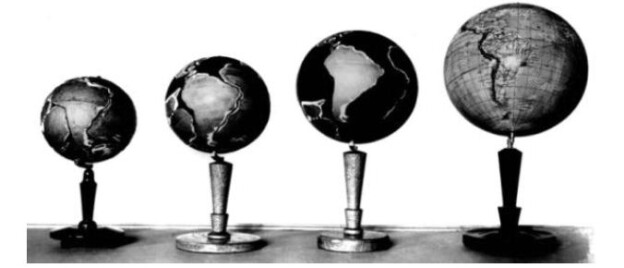

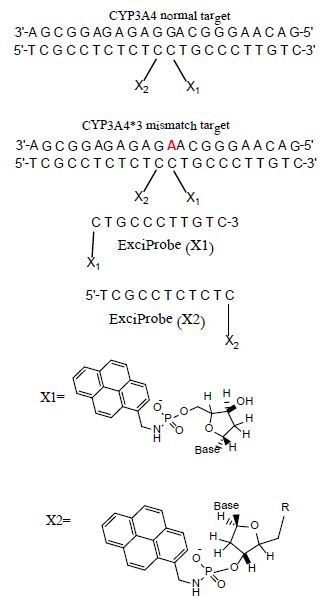

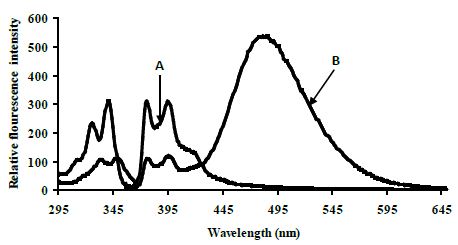

Control experiments on a 1:1 mixture of 5′-pyrenyl ExciProbe (X1) and 3′-pyrenyl ExciProbe probe (X2) oligonucleotides were carried out in 80% TFE/0.01 M Tris, 0.1 M NaCl, pH 8.4 to determine if the fluorescence was from pyrene interacting as an excimer with the intended pyrene exci-partner, or an interaction with bases of the oligonucleotides. The 5′-pyrenyl ExciProbe (X1) showed no band at 480 nm in the absence of the target oligonucleotide (Figure 3). Addition of the complementary oligonucleotide target to ExciProbe (X1) resulted in a slight shift in λmax of LES emission to 379 nm, consistent with hybridisation of the probe with the complementary target. However, no marked 480 nm band was seen, even after heating the system to 70°C and re-annealing by slowly cooling back to 5°C. The weak fluorescence emission at 480 nm for the control duplex (before and after heating cooling, Figure 3) on duplex formation appeared real and could be related to exciplex formation, due to intra-molecular interaction of pyrene within the assembled duplex. However, relative to the full system with both 3′- and 5′-pyrenyl groups (Figure 3) the emission at 480 nm is insignificant.

Figure 3: Emission spectra for control terminally located system A 5′-pyrenyl ExciProbe (X1) oligonucleotide, B 3′-pyrenyl ExciProbe (X2) and the 22 mer target in 80% TFE/10 mM Tris, 0.1 M NaCl, pH 8.4 at 5°C. Excitation wavelength 350 nm, slitwidth 5 nm. Equimolar component concentration was 2.5 μM.

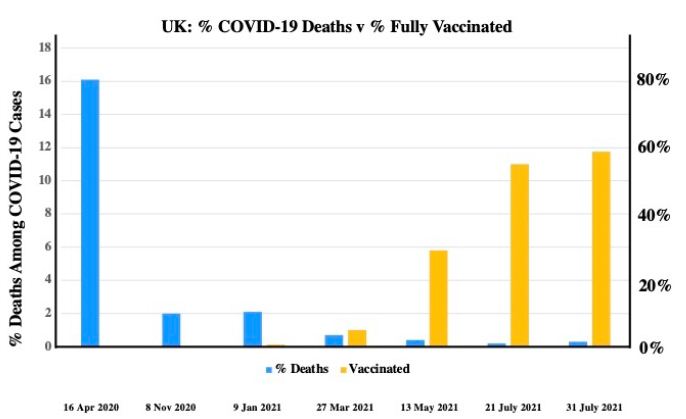

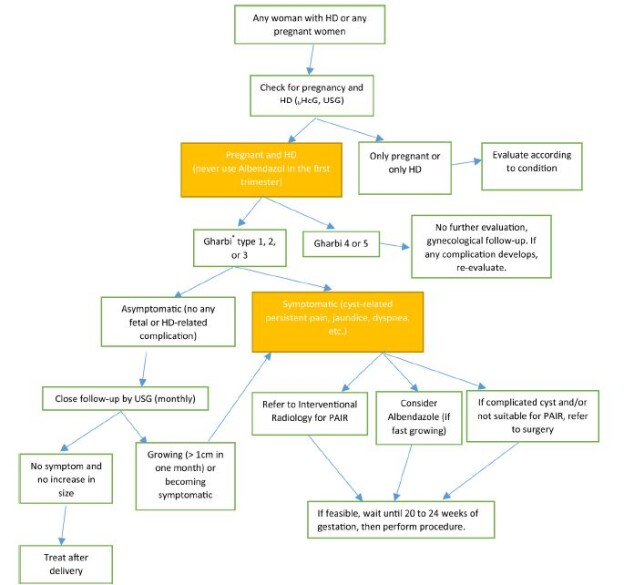

CYP3A4*1B Single Nucleotide Polymorphism

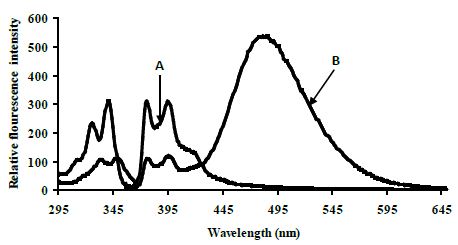

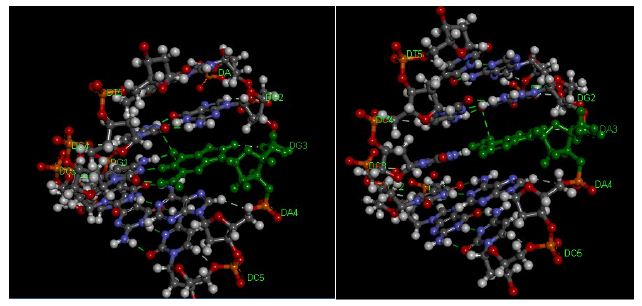

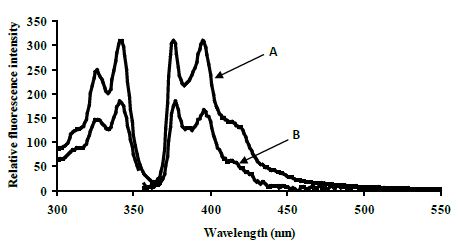

The excimer emission was detected (broadband at ~480 nm) for normal target and showed strong emission at 480 nm (545 relative fluorescence intensity) compared to the mutated target (220 relative fluorescence intensity) around 2.5 fold (Figure 4).

Figure 4: Emission spectra comparing the normal target A, CYP3A4) with the mutated target B, CYP3A4*1B) in 80% TFE/ Tris buffer (10 mM Tris, 0.1 M NaCl, pH 8.4) at 5°C after heating the samples to 90°C. Spectra were recorded when emission intensity had reached a maximum after 10 minutes at 5°C. Excitation was at 350 nm, slitwidth 5 nm. Spectra, buffer-corrected, are scaled to LES emission (378.9 nm).

Melting Temperatures of SNP

Melting curve experiments were performed spectrophotometrically at A260 and estimated by using the first derivative method. The melting temperatures (Tm) for normal CYP3A4 target was 76.9 ±0.8°C and 75.0 ±0.8°C for CYP3A4*1B, respectively. The melting temperature at 260 nm for systems was performed in 80% TFE/Tris buffer (10 mM Tris, 0.1 M NaCl, pH 8.4). Control experiments for Tm were carried out in 80% TFE/Tris buffer. In addition, similar thermal results were obtained using fluorescence melting curve experiments based on excitation 350 nm and emission 480 nm for the excimer. The fluorescence thermal study was performed using a Cary Eclipse fluorescence spectrophotometer by measuring the change in fluorescence intensity for the excimer with temperature.

Discussion

Confirmation of Duplex Formation

In our experiments of hybridising the two 11 mer probes to the complementary target in phosphate buffer (pH 7.0) containing 0.1 M NaCI, the pyrene moieties of the two probes came into close proximity, and an excimer band at 480 nm was generated. This result is consistent with results obtained by [27] who used a system that incorporated a pyrene-modified nucleotide at the 5′-end of one probe and a pyrene-modified nucleotide at the 3′-end of the other [27]. Figure 2 shows fluorescence typical of pyrene local excited state (LES) emission (lmax = 376, 395 nm) for a 5′-pyrenyl ExciProbe (X1) labelled oligonucleotide alone. The emission spectrum obtained is similar to that obtained in the literature using10 mM phosphate buffer (pH 7.0) 20 % v/v DMF, 0.2 M NaCl at 25°C and gave lmax = 377, 396 nm [1,2,26]. Addition of the 5′-pyrenyl ExciProbe (X1) to the 3′-pyrenyl ExciProbe (X2) target resulted in immediate quenching of the LES emission at 395 nm to less than one-third of its original value and the appearance of a new, broad emission band atlmax = 480 nm characteristic of pyrene excimer fluorescence (Figure 2).

Melting experiments provide further strong evidence of duplex formation. The split-probe systems showed sigmoid single-transition melting curves spectrophotometrically (A260 or A350) or spectrofluorometrically from fluorescence intensity at 340 nm for the LES (lex) and 376 nm (lem) for thepyrene monomer and at 350 nm for LES (lex) and 480 nm (lem) for the excimer (data not shown). Additional evidence of duplex formation comes from the emission spectra, as one probe oligonucleotide alone did not give an excimer signal in the absence of the other complementary probe. Further evidence of duplex formation and reversibility came from experiments using a heating and cooling cycle. Experiments of terminally located probe systems at different temperatures showed that the excimer intensity decreased when the temperature increased and eventually disappeared. This process is reversible, providing further evidence of duplex formation. A better-formed duplex structure probably enables the exci-partners to be better positioned for excimer formation. The reappearance of the excimer spectra on re-cooling indicates that no destruction of the components occurs on heating the system.

Evidence of Excimer Formation

The red-shifted structureless band at ~480 nm is characteristic of excimer emission, but could be due to interaction of the exci-partners with each other or nucleobases as pyrene are able to form an exciplex with certain nucleotide bases, especially guanine and to a lesser extent thymidine [28,29]. Also some oligonucleotide sequences show weak exciplex emission from pyrene attached to their 5′-termini in the absence of any added (complementary) oligonucleotide [30]. Thus, it is important to establish for the terminally located system the origin of the emission at 480nm. Heating the system caused the excimer emission intensity to decrease due to dissociation of the duplex structure. On re-cooling the system excimer emission reappeared. The Tm values by fluorescence and UV-visible methods were similar and of the magnitude expected for such a system (22-mer duplex) [31].

CYP3A4*1B Single Nucleotide Polymorphism

The search for sequences that differ in only one or two nucleobases needs tools to detect nucleic acid sequences that have high performance, speed, simplicity, and low cost. There have been many different techniques developed to identify the mutations in nucleic acid sequences. Techniques based on matched/mismatched-duplex stabilities, restriction cleavage, ligation, nucleotide incorporation, mass spectrometry and direct sequencing have been reviewed [32,33]. The DNA split-probe system of CYP3A4*1B was able to discriminate between perfectly matched CYP3A4 and mismatched CYP3A4*1B targets. Several split-oligonucleotide systems have been reported to discriminate between SNPs. These include the ligation method of Landegen [34], nanoparticle probes[35,36] and the template-directed ligation method [37,38]. The split-probe excimer system of Paris [39] was found to be sensitive to a single-base mutation in the target, positioned four base pairs from the 3′-junction. In the Paris study the addition of the unmutated target to the pyrene probes resulted in an increase in 490 nm emission as well as a 4.7-fold decrease in 398 nm monomer emission. The resulting excimer:monomer ratio was 0.04, very different to that for the sequence with a single-base point mutation which was 2.7 [39].

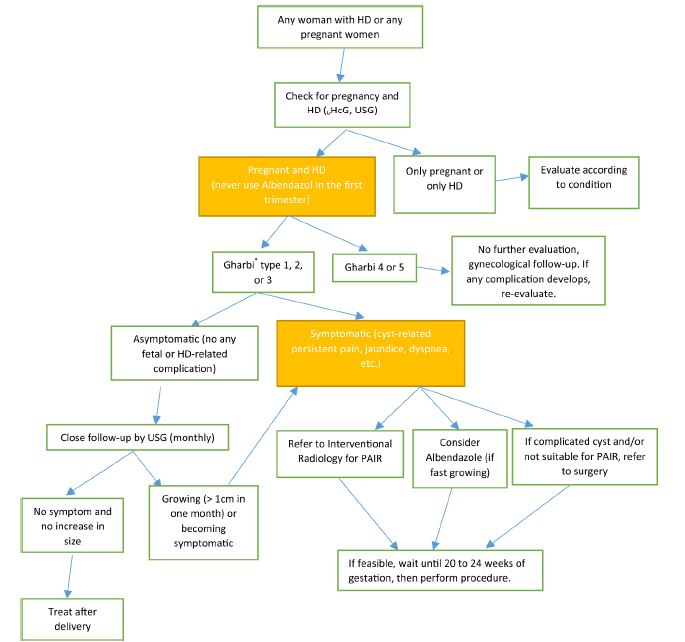

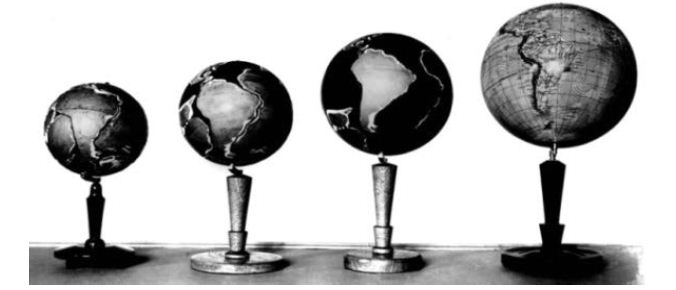

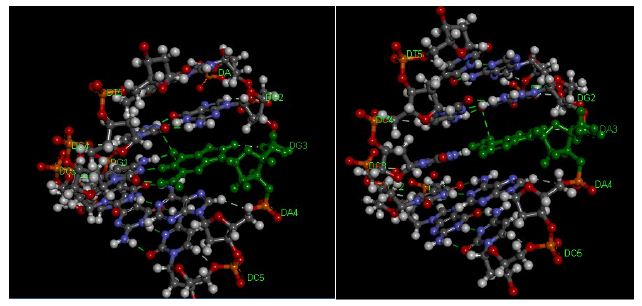

In the present study the duplexes containing GAGAACG/CTCCTGC mismatch is significantly destabilized compared with its correctly paired parent. Amber and Znosko [40] studied the thermodynamics of A/G mismatches in different nearest-neighbour contexts. They found a penalty (energy loos) of 1.2 kcal/mol for replacing a G-C base pair with either an A-U or G-U base pair. For both CYP3A4 (normal target) and CYP3A4*1B (mismatched target) showed a sigmoidal melting profile, typical of the dsDNA to ssDNA transition, providing further evidence of tandem duplex formation. The Tm values of CYP3A4*1B are less to those of the fully matched, consistent with literature studies performed on different sequences under identical conditions[25]. Duplexes of CYP3A4*1B (mismatched target) with mismatches of G/A in the twelve position from the 3′ and 5′ ends, respectively, showed significantly lower Tm than CYP3A4 (normal target). These results indicate that the ∆G contribution of a single G/A mismatch and the position of the mismatch are crucial to duplex stability and consistent with the literature [41,42]. The ∆G contribution of a single G/A mismatch to duplex stability was studied by [43] who found that ∆G is dependent on the neighbouring base pairs and ranges from +1.16 kcal/mol (for the context TGA/AAT) to -0.78 kcal/mol (for the context GGC/CAG). Allawi [43] also showed that the nearest neighbour model is applicable to internal G/T mismatches in DNA. In their study of G/T mismatches, the most stable trimer sequence containing a G/T mismatch was -1.05 kcal/mol for CGC/GTG and the least stable was +1.05 kcal/mol for AGA/TTT. On average, when the closing Watson-Crick pair on the 5′ side of the mismatch is an A/T or a G/C pair, G/A mismatches are more stable than G/T mismatches by about 0.40 and 0.30 kcal/mol, respectively [43,44]. When the 5′ closing pair is a T/A or a C/G, then G/T mismatches are more stable than G/A mismatches by 0.54 and 0.75 kcal/mol, respectively. Evidently, the different hydrogen-bonding and stacking in G/T and G/A mismatches results in different thermodynamic trends and the energy and structural information are the compositions of the following variables, such as bond angle energies, bond energies, planarity energies, dihedral angle energies, Van der Waals energies or/and electrostatic energies. These results indicate that duplexes containing mismatches are considerably destabilized (Figure 5) compared with their correctly paired parent the extent being dependent on the base composition and sequence of the oligonucleotide as well as on the type and location of the mismatch. The mismatch of DNA leads to alterations of amino acid properties and can cause a change in protein structure [45,46]. Consequently, SNP may affect enzyme activity through the modification of protein structure and function [47].

Figure 5: Pentamer of DNA Duplexes of theCYP3A4 gene. A: matched CYP3A4 target (AGGAC/TCCTG), B: CYP3A4*1B target (AGAAC/TCCTG). The hydrogen bonds are represented using green broken lines. The figure was obtained with the help ofthe molecular visualization tool (Discovery Studio Visualizer software 4.1).

Conclusion

Our results evaluate the first case of an oligonucleotide split probe system based on excimer fluorescence emission for detection of CYP3A4*1B single nucleotide polymorphism. Further studies will be necessary to understand the details of the split probe system structure which determine the formation of the excimer for CYP3A4 single nucleotide polymorphism. Based on fluorescence and spectrophotometric results, the split probe system is selective enough to detect single base mutations of CYP3A4*1B with good sensitivity and therefore could be used to detect other mutations using an excimer system.

Acknowledgement

The authors gratefully acknowledge the support and valuable suggestions obtained from Sir Khaled AB Diab (Judicial Expertise and Research Centre, Tripoli, Libya Tripoli, Libya).

References

- Ebata K, Masuko M, Ohtani H, Jibu M (1995) Excimer formation by hybridization using two pyrene-labeled oligonucleotide probes. Nucl Acids Symp Ser 34: 187-188. [crossref]

- Ebata K, Masuko M, Ohtani H, Kashiwasake-Jibu M (1995) Nucleic acid hybridization accompanied with excimer formation from two pyrene-labeled probes. Photochem Photobiol 62: 836-839. [crossref]

- Masuko M, Ebata K, Ohtani H (1996) Optimization of pyrene excimer fluorescence emitted by excimer-forming two-probe nucleic acid hybridization method. Nucl Acids Symp Ser 1996 35: 165-166. [crossref]

- Ibele LM, Sánchez-Murcia PA, Mai S, Nogueira JJ, GonzÃlez L (2020) Excimer Intermediates en Route to Long-Lived Charge-Transfer States in Single-Stranded Adenine DNA as Revealed by Nonadiabatic Dynamics. J Phys Chem Lett 11: 7483-7488. [crossref]

- Conlon P, Yang CJ, Wu Y, Chen Y, Martinez K, et al. (2008) Pyrene Excimer Signaling Molecular Beacons for Probing Nucleic Acids. J Am Chem Soc 130: 336-342. [crossref]

- Balakin KV, Korshun VA, Mikhalev II, Maleev GV, Malakhov AD, et al. (1999) Conjugates of oligonucleotides with polyaromatic fluorophores as promising DNA probes. Biosensors & Bioelectronics 14: 597. [crossref]

- Letsinger RL, Wu T (1994) Control of Excimer Emission and Photochemistry of Stilbene Units by Oligonucleotide Hybridization. J Am Chem Soc 116: 811-812.

- Shimadzu A, Ohtani H, Ohuchi S, Sode K, Masuko M (1998) Perylene excimer formation by excimer-forming two-probe nucleic acid hybridization method. Nucl Acids Symp Ser 39: 45-46.

- Vallejos-Vidal E, Reyes-Cerpa S, Rivas-Pardo JA, Maisey K, Yajez JM, et al. (2019) Single-Nucleotide Polymorphisms (SNP) Mining and Their Effect on the Tridimensional Protein Structure Prediction in a Set of Immunity-Related Expressed Sequence Tags (EST) in Atlantic Salmon (Salmo salar). Front Genet 10: 1406. [crossref]

- Xiong LL, Xue LL, Al Hawwas M, Huang J, Niu RZ, et al. (2020) Single-nucleotide polymorphism screening and RNA sequencing of key messenger RNAs associated with neonatal hypoxic-ischemia brain damage. Neural Regen Res 15: 86-95.

- Bertolini F, Scimone C, Geraci C, Schiavo G, Utzeri VJ, et al. (2015) Next Generation Semiconductor Based Sequencing of the Donkey (Equus asinus) Genome Provided Comparative Sequence Data against the Horse Genome and a Few Millions of Single Nucleotide Polymorphisms. PLoS One 10.

- Parahuleva MS, Schieffer B, Klassen M, Worsch M, Parviz B, et al. (2018) Expression of the Marburg I Single Nucleotide Polymorphism (MI-SNP) and the Marburg II Single Nucleotide Polymorphism (MII-SNP) of the Factor VII-Activating Protease (FSAP) Gene and Risk of Coronary Artery Disease (CAD): A Pilot Study in a Single Population. Med Sci Monit 24: 4271-4278.

- Liu J, Zhang L, Feng L, Xu M, Gao Y, et al. (2019) Association between single nucleotide polymorphism (rs4252424) in TRPV5 calcium channel gene and lead poisoning in Chinese workers. Mol Genet Genomic Med 7.

- Bichenkova EV, Gbaj A, Walsh L, Savage HE, Rogert C, et al. (2007) Detection of nucleic acids in situ: novel oligonucleotide analogues for target-assembled DNA-mounted exciplexes. Org Biomol Chem 5: 1039-1051.

- Wilson RT, Masters LD, Barnholtz-Sloan JS, Salzberg AC, Hartman TJ (2018) Ancestry-Adjusted Vitamin D Metabolite Concentrations in Association with Cytochrome P450 3A Polymorphisms. Am J Epidemiol 187: 754-766. [crossref]

- Serin I, Pehlivan S, Gundes I, Fidan OY, Pehlivan M. A new parameter in multiple myeloma: CYP3A4*1B single nucleotide polymorphism. Ann Hematol 1-7.

- Zeigler-Johnson CM, Spangler E, Jalloh M, Gueye SM, Rennert H, et al. (2008) Genetic susceptibility to prostate cancer in men of African descent: implications for global disparities in incidence and outcomes. Can J Urol 15: 3872-3882. [crossref]

- Berno G, Zaccarelli M, Gori C, Tempestilli M, Antinori A, et al. (2014) Analysis of single-nucleotide polymorphisms (SNPs) in human CYP3A4 and CYP3A5 genes: potential implications for the metabolism of HIV drugs. BMC Med Genet 15: 76. [crossref]

- Johnson N, De Ieso P, Migliorini G, Orr N, Broderick P, et al. (2016) Cytochrome P450 allele CYP3A7*1C associates with adverse outcomes in chronic lymphocytic leukemia, breast and lung cancer. Cancer Res 76: 1485-1493. [crossref]

- Reyes-Hernández OD, Vega L, Jiménez-RÃos MA, MartÃnez-Cervera PF, Lugo-GarcÃa JA, et al. (2014) The PXR rs7643645 Polymorphism Is Associated with the Risk of Higher Prostate-Specific Antigen Levels in Prostate Cancer Patients. PLoS One 9: 99974. [crossref]

- Johnson N, De Ieso P, Migliorini G, Orr N, Broderick P, et al. (2016) Cytochrome P450 allele CYP3A7*1C associates with adverse outcomes in chronic lymphocytic leukemia, breast and lung cancer. Cancer Res 76: 1485-1493. [crossref]

- Puranik YG, Birnbaum AK, Marino SE, Ahmed G, Cloyd JC, et al. (2013) Association of carbamazepine major metabolism and transport pathway gene polymorphisms and pharmacokinetics in patients with epilepsy. Pharmacogenomics 14: 35-45. [crossref]

- Świechowski R, JeleŠA, Mirowski M, Talarowska M, Gałecki P, et al. (2019) Estimation of CYP3A4*1B single nucleotide polymorphism in patients with recurrent Major Depressive Disorder. Mol Genet Genomic Med 7.

- Cantor CR, Warshaw MM, Shapiro H (1970) Oligonucleotide interactions. 3. Circular dichroism studies of the conformation of deoxyoligonucleotides. Biopolymers 9: 1059-1077. [crossref]

- Bichenkova EV, Savage HE, Sardarian AR, Douglas KT (2005) Target-assembled tandem oligonucleotide systems based on exciplexes for detecting DNA mismatches and single nucleotide polymorphisms. Biochem Biophys Res Commun 332: 956-964. [crossref]

- Masuko M, Ohtani H, Ebata K, Shimadzu A (1998) Optimization of excimer-forming two-probe nucleic acid hybridization method with pyrene as a fluorophore. Nucl Acids Res 26: 5409-5416. [crossref]

- Yamana K, Nunota K, Nakano H, Sangen O (1994) A new method for introduction of a pyrene group into a terminal position of an oligonucleotide. Tet Lett 35: 2555-2558.

- Geacintov NE, Moller W, Zager E (1976) The triplet state of benzo[a]pyrene as a probe of its microenvironment in DNA complexes. Biol Mol Proc Int Conf 199-206.

- Manoharan M, Tivel K, Zhao M, Nafisi K, Netzel TL (1995) Sequence dependence of emission lifetimes for DNA oligomers and duplexes covalently labeled with pyrene: Relative electron-transfer quenching efficiencies of A, G, C and T nucleosides toward pyrene. J Phys Chem 99: 17461-17472.

- Hannah Savage (2003) Studies of Fluorescence Detection of Nucleic Acid Sequences. The University of Manchester. (GENERIC)Ref Type: Thesis/Dissertation.

- Lewis FD, Wu T, Burch EL, Bassani DM, Yang JS, et al. (1995) Hybrid Oligonucleotides Containing Stilbene Units. Excimer Fluorescence and Photodimerization. J Am Chem Soc 117: 8785-8792.

- Landegren U, Nilsson M, Kwok PY (1998) Reading bits of genetic information: methods for single-nucleotide polymorphism analysis. Genome Res 8: 769-776.

- Shi MM (2001) Enabling large-scale pharmacogenetic studies by high-throughput mutation detection and genotyping technologies. Clin Chem 47: 164-172. [crossref]

- Landegren U, Kaiser R, Sanders J, Hood L (1988) A ligase-mediated gene detection technique. Science 241: 1077-1080. [crossref]

- Cao Y, Jin R, Mirkin CA (2001) DNA-modified core-shell Ag/Au nanoparticles. J Am Chem Soc 123: 7961-7962. [crossref]

- Seife C (2002) Analytical chemistry. Light touch identifies wisps of rogue DNA. Science 297: 1462. [crossref]

- Chen X, Kwok PY (1999) Homogeneous genotyping assays for single nucleotide polymorphisms with fluorescence resonance energy transfer detection. Genetic Anal-Biomol E 14: 157-163. [crossref]

- Chen X, Kwok PY (1997) Template-directed dye-terminator incorporation (TDI) assay: a homogeneous DNA diagnostic method based on fluorescence resonance energy transfer. Nucleic Acids Res 25: 347-353.

- Paris PL, Langenhan JM, Kool ET (1998) Probing DNA sequences in solution with a monomer-excimer fluorescence color change. Nucl Acids Res 26: 3789-3793. [crossref]

- Davis AR, Znosko BM (2007) Thermodynamic characterization of single mismatches found in naturally occurring RNA. Biochemistry 46: 13425-13436. [crossref]

- Sagi J (2017) In What Ways Do Synthetic Nucleotides and Natural Base Lesions Alter the Structural Stability of G-Quadruplex Nucleic Acids? J Nucleic Acids 2017: . [crossref]

- Kent JL, McCann MD, Phillips D, Panaro BL, Lim GF, et al. (2014) Non-nearest-neighbor dependence of stability for group III RNA single nucleotide bulge loops. RNA 20: 825-834.

- Allawi HT, SantaLucia J Jr (1998) Nearest Neighbor Thermodynamic Parameters for Internal G.A Mismatches in DNA. Biochemistry 37: 2170-2179. [crossref]

- Allawi HT, SantaLucia J Jr, (1997) Thermodynamics and NMR of Internal G.T Mismatches in DNA. Biochemistry 36: 10581-10594. [crossref]

- Pei J, Kinch LN, Otwinowski Z, Grishin NV (2020) Mutation severity spectrum of rare alleles in the human genome is predictive of disease type. PLoS Comput Biol 16:1007775. [crossref]

- Lyons DE, Yu KP, Vander Heiden JA, Heston L, Dittmer DP, et al. (2018) Mutant Cellular AP-1 Proteins Promote Expression of a Subset of Epstein-Barr Virus Late Genes in the Absence of Lytic Viral DNA Replication. J Virol 92: 01062-01018. [crossref]

- Jia P, Zhao Z (2017) Impacts of somatic mutations on gene expression: an association perspective. Brief Bioinform 18: 413-425. [crossref]