Abstract

Objective: To explore the mechanism of Guishen Decoction in the treatment of ischemic stroke by network pharmacology, to find the essence of modern pathology in Traditional Chinese Medicine (TCM) “kidney brain correlation” theory, and to furnish notions for the development of new medicaments and the expansion and application of classical formulas.

Methods: The dominating chemical components and targets of mulberry, yam and dodder seed were secured through TCMSP (Traditional Chinese Medicine Systems Pharmacology Database and Analysis Platform) database, and the active components were screened in the accordance with OB (Oral bioavaliability) and DL (Drug-likeness); Genecards, PharmGkb, TTD, OMIM, DrugBank and other databases obtained the main relevant targets of ischemic stroke, and employed the String platform to construe protein-protein-interactions, build PPI networks and explore potential protein functional compartments. R software was applied to essay the “drug-component-target” relationship and the biological processes and pathways involved, and Cytoscape software was utilized to establish the “nourishing kidney ingredient-ischemic stroke target-pathway” network.

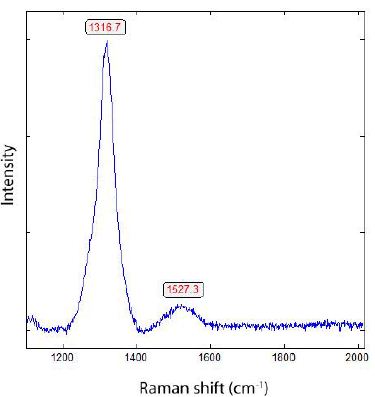

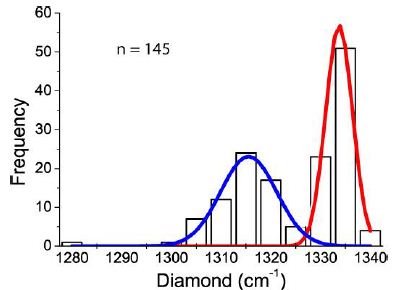

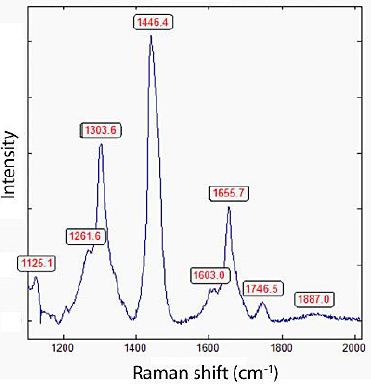

Results: The screened core active targets of the Guishen Decoction for the treatment of ischemic stroke were prostaglandin G/H synthase 2, interleukin 10, fatty acid synthase, etc., and most of the targets and components had good binding activity. The signaling pathway of nourishing kidney and filling essence formula for ischemic stroke mainly acts on reactive oxygen species and mitochondria.

Conclusion: This investigation preliminarily extrapolates the pathognomonic feature of multi-component, multi-target and multi-pathway combination of the method of Guishen Decoction in ischemic stroke, which provides ideas for the discussion of the modern medical essence of the “kidney brain correlation” theory of TCM.

Keywords

Nourishing Kidney, Network pharmacology, Ischemic stroke, Kidney brain correlation, Guishen decoction

Introduction

Stroke, which also known as cerebrovascular accident or brain vascular accident, is regarded as an acute cerebrovascular disease evoked by the rhexis or blockage of blood vessels in the brain, resulting in damage to brain tissue. It is the primary cause of disability among adults and the second leading cause of death in humans. Stroke includes two capital categories: ischemic stroke and hemorrhagic stroke, with ischemic stroke being the most prevalent [1]. Ischemic stroke is individualized by high disability, mortality, and recurrence rates. In accordancce with survey statistics, the onset age of strokes is decreasing year by year [2], and it has now become one of the material agents of death among habitants in China [3].

The temporary or permanent occlusion of cerebral blood vessels can lead to cerebral tissue ischemia, causing local brain tissue and functional damage. The extent of contaminate is associated to the duration of ischemia and reliquus blood flow: short-term incomplete ischemia only induces reversible impairment, while long-term complete or severe ischemia can reflect on cerebral ischemic infarction. Ischemic stroke causes neuronal damage through multiple pathways and targets, including apoptosis, transformation of astrocytes and neurons mediated by Neural Precursor Cells (NPCs), and loss of neurotrophic factors (NT). In the ischemic core, neuronal cell bodies and axons disappear, and glial cells exhibit cytoplasmic swelling and nucleolar loss; in the ischemic border zone, there is disintegration of endoplasmic reticulum ribosomes and mitochondria. At this time, microglia are activated, exhibiting amoeboid-like swelling, concomitted with the generation of inflammatory substances such as cytokines, chemokines, and oxygen free radicals. Additionally, Blood-Brain Barrier (BBB) permeability increases, allowing immune cells, like leukocytes, monocytes, and macrophages, to infiltrate the ischemic lesion, causing neurotoxicity and damaging NT [4]. Cerebral tissue suffers from hypoxia and glucose deprivation due to interrupted blood flow, resulting in inadequate ATP synthesis, energy imbalance, and disturbances in ion and acid-base balance. Upon reperfusion of cerebral blood vessels, the brain tissue undergoes repeated injury, presenting pathological changes such as mitochondrial swelling, cristae rupture, endoplasmic reticulum swelling, and increased intercellular gaps of vascular endothelial cells, leading to irreversible damage [5]. The concrete pathological mechanisms occurred in the Cerebral Ischemia Reperfusion Injury (CIRI), for example, the release of oxygen free radicals, calcium ion overload [6], excitatory amino acids, inflammatory responses [7,8], apoptosis [9], and depletion of high-energy phosphates [10]. These pathological changes cause cerebral tissue necrosis, structural damage, neuronal death, and local neurological dysfunction [11].

The existence of a time window for CIRI poses a dominating challenge in the diagnosis and cure process of ischemic stroke. With prolonged cerebral ischemia time, the difficulty of using drugs or surgical methods to restore cerebral blood flow increases, and the severity of CIRI worsens. Currently, the only evidence- based treatment drug accepted for treating acute ischemic stroke is recombinant tissue-type plasminogen activator (r-tPA) (Powers et al., 2019) [12]. However, this drug cannot alleviate reperfusion injury after cerebral ischemia. Ischemic stroke is among the primary element conditions threatening human life and causing disability and cognitive impairment [13].

TCM has build up abundant experience in the obviattion and iateria of ischemic stroke. In “Synopsis Golden Chamber”, there is a method of “pounding the juice of sedge and pouring it into the ears, blowing the powder of honey locust into the nose” to treat blindness due to stroke. Since the Jin and Yuan Dynasties, with the gradual rise of Mingmen theory, the theory of “kidney brain correlation” has also become one of the main guiding ideas for the prevention and treatment of ischemic stroke. “Huangdi Neijing” states that the kidneys and brain are connected through the brain marrow. “Huayang Zangxiang Yuanbian” agrees with this statement and believes that the brain marrow is the main material basis for the brain to exert its physiological functions: “Within the human body, spanning from the waist to the spine, governing the limbs, connecting the joints, lies the pivotal point of the soul and the essence of life – the brain and spinal cord.” Zhang Xichun’s “Yixue Zhongxi Canxi Lu” describes in detail the relationship between the brain and the kidneys under the theory of TCM: the kidneys contain innate essence, and are related to The acquired essence and Qi in the kidneys are combined into kidney essence. The kidney essence goes up the spine and perfuses into the brain. The clear part is transformed into the marrow. It is called the spinal cord in the spine. It flows into the bones and is called the bone marrow. When it enters the brain, it is called the cerebral marrow. The kidneys and brain communicate with each other through the transformation of the essence, and are connected by the bladder meridian, governor meridian, and kidney meridian, forming a “kidney-brain mutual support” relationship that is interconnected in terms of material relationships, meridians, and organ functions. Therefore, during the onset of ischemic stroke, the physiological activities occuring in the brain are severely damaged, and the method of nourishing the kidneys and replenishing essence can be used to indirectly replenish the brain marrow, abundant the prognosis methods of ischemic stroke patients and improve the prognosis of ischemic stroke patients. In modern medical research, cerebral blood flow is interrupted during cerebral ischemia injury, glucose and oxygen in the brain are depleted, ATP synthesis is interrupted, and energy is insufficient [14], ion homeostasis is damaged, acid-base balance is disordered, causing brain neuroinflammation, nerve cell death, and mitochondrial dysfunction; in the core area of ischemia, brain neuron cell bodies and axons disappear [15], cytoplasmic swelling of neurons and glial cells, disappearance of nucleoli, disintegration of endoplasmic ribosomes and Nissl bodies in the ischemic penumbra area, morphology of microglia and astrocytes Changes in [4], damage to brain endothelial cells [16], and reduction in the number of neurons and neural stem cells [17], reducing the content of brain-derived neurotrophic factor [18], corresponding to the insufficient permeability of Qi and blood in the brain, malnutrition of brain marrow, and ineffectiveness of Yuanshen in the theory of TCM, and the hypothalamus-pituitary- adrenal axis can regulate Ca2+ concentration and Ca2+ channel activity [19], inhibit neuroinflammatory response [17,16,20], reduces oxygen free radical damage [21], reduces neuronal and hippocampal The expression of pro-apoptotic proteins [22] protects brain tissue, which provides modern medical basis for the “kidney brain correlation” theory of TCM.

Professor Yuan Zhenyi of our school prepared the “Guishen Decoction”, which is composed of three TCMs: mulberry, yam and dodder seed. It is very effective in treating kidney Qi deficiency. The kidneys are the foundation of innateness. Kidney yang transpires and transforms into Qi, guiding the passage of water; kidney yin communicates with the liver and relieves the liver’s strong Qi; kidney essence inherits the innate nature and is nourished by acquired nutrients. In Guishen Decoction, mulberry nourishes yin and blood, and also benefits moisture; yam nourishes the lungs, spleen, and kidneys, which can nourish the kidneys and astringent essence, improve intelligence and calm the mind; dodder seeds nourish the liver and kidneys, warm the kidneys, solidify essence, and reduce urination. The three medicines work together to nourish kidney Qi, kidney essence, kidney yin and kidney yang, diuretic, astringent essence, soothe the nerves and nourish blood. The properties of the three medicines are nourishing and greasy, which is consistent with the nature of the kidney as a water organ. It nourishes the kidneys, replenishes essence and nourishes vitality, and then nourish the brain. At present, the research on the treatment of stroke with kidney is gradually deepening and extensive. Ling et al. [23] used Ruyi Zhenbao Pills to treat stroke, evaluation found that the patient’s motor and sensory functions were restored; Li et al. [24] verified that Zuogui Pill’s treatment for ischemic stroke by means of network pharmacology and in vitro experimental verification therapeutic effect of ischemic stroke; Tang et al. [25] found that kidney essence deficiency syndrome is the most common among the TCM syndrome types in patients with post- stroke dementia, and is commonly used in clinical practice. Among the kidney-based prescriptions for treating ischemic stroke, Zuogui Pills, Liuwei Dihuang Decoction, Ruyi Zhenbao Dan, etc. all contain the shadow of Guishen Decoction. For example, Zuogui Pills contain yam and dodder seeds, while wolberry and cooked rehmannia root are included, deer antler glue has the same effect as mulberry; Liuwei Dihuang Pills contain yam, while Rehmannia glutinosa, wine cornus and Alisma have the same effect as dodder and mulberry; Ruyi Zhenbao Dan contains long pepper, clove, galangal, fragrant celery, Cinnamon and cardamom dispel wind and cold, warm and unblock the life vessels, and have the same effect as Guishen Decoction. It can be seen that the formulation idea of Guishen Decoction has important implications in the clinical cure process of ischemic stroke building upon the “kidney brain correlation” theory. Wide range of applications. In modern medical research, mulberry could reverse the disorder of redox system in brain conduced by rotenone [26], chronic stress [27], halopeidol [28], D-galactose [29], Schistosoma mansoni infection [30], aging [31], glyphosate [32], Alzheimer [33] and cholinotoxins (Wattanathorn et al., 2012) [34], and increase the levels of antioxidant enzymes in the body including catalase (CAT), superoxide dismutase (SOD), glutathione peroxidase (GPx), glutathione S-transferase (GST), glutathione reductase (GRd), and the contents of reduced glutathione (GSH), decrease the levels of lactate dehydrogenase (LDH) activity, nitrite (NO), and malonyldialdehyde (MDA) levels, which are formed by the oxidation. Sheeba S. S. et al [35] Comparison of mulberry leaf extract MLE-AR-14 and the effect of resveratrol on CIRI mice. Both mulberry extract and resveratrol can remarkably deplete the cerebral infarction mice’s volume, and mulberry extract can reduce malondialdehyde (a kind of malondialdehyde) in serum, increase glutathione (an endogenous antioxidant) level, and exert a protective effect on nerve cells by suppressing the activity of oxygen free radicals. Studies by Kang T. H. [36], Kaewkaen P [37] and others have proven mulberry exerts protective effects on the brain tissue of stroke rats [38]. In the study of Hou et al. [39], Cuscutae can increase brain Nrf-2 and inflammatory responses caused by oxidative stress. HO-1 protein levels, reduce neuroinflammatory response in mice, and inhibit the activation of microglia and astrocytes [40], found that dodder it can inhibit synaptic loss in the hippocampus of Alzheimer’s mice and inhibit neuronal apoptosis by inhibiting Caspase-3 activation, thereby exerting neuronal protection. Although there are few studies on yam and ischemic stroke, current research shows that yam has immunomodulatory effects and can effectively inhibit the inflammatory response [41,42].

With the advancement of bioinformatics technology and the improvement of related databases, network pharmacology technology has become one of the main tools in drug research to reveal the relationship between drugs, targets, pathways and related diseases [43], molecular docking technology has also become an effective means to verify the potential association between active ingredients and target genes analyzed by network pharmacology [44]. Therefore, this study uses Professor Yuan Zhenyi’s self-prepared “Guishen Decoction” to conduct network pharmacology research on ischemic stroke, and conducts in-depth research on the molecular correlation between nourishing kidney and filling essence recipe and ischemic stroke through network pharmacology methods, explore the modern medical connotation of the “kidney brain correlation” theory of TCM, broaden strategies for stroke prevention and treatment using TCM, and further carry out research on the “kidney essence” mechanism.

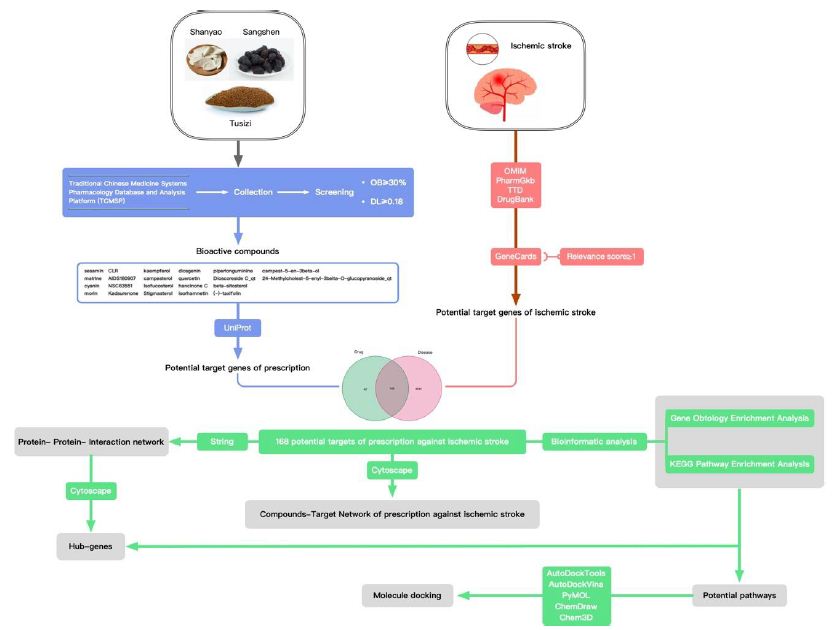

In this study, the author plans to employ network pharmacology approaches to study the bioactive compound targets and signaling pathways of the pharmaceutical ingredients of Guishen Decoction to provide more complete TCM ideas for the ischemic stroke prevention and management. In this study, the author examined the intricate interplay among diseases, medications, and targets utilizing diverse databases and system predictions. The focus was on elucidating the pivotal targets and potential mechanisms of Guishen Decoction in managing ischemic stroke. Molecular docking technology was employed to validate the potential target of Guishen Decoction for ischemic stroke. The entire study is illustrated in Figure 1.

Figure 1: Network pharmacology and molecular docking workflow of bioactive compounds in Guishen Decoction for the treatment of ischemic stroke.

Materials and Methods

Identification and Screening of Bioactive Compounds in Guishen Decoction

Search separately using the Traditional Chinese Medicine Systems Pharmacology Database (TCMSP; https: //tcmsp-e.com/tcmsp.php, accessed on 20 February 2024) [45]. The chemical composition of the three-flavored Guishen Decoction of yam, mulberry and dodder. Guishen Decoction is an effective prescription for the treatment of ischemic stroke. The active ingredients in the drug should be able to normally complete the absorption, distribution, metabolism and excretion processes in the human body. Accordingly, we searched and evaluated the absorption, distribution, metabolism and excretion (ADME) [46] properties of the three Guishen Decoction drugs in the model of human body through the TCMSP database, and screened out compounds without ADME information. According to the standards established by the TCMSP database, compounds should meet the oral bioavailability (OB) ≥ 30% and drug-likeness (DL) ≥ 0.18 before they can be considered as potential bioactive ingredients of Guishen Decoction. Accordingly, OB and DL were used as key parameters to screen the compounds again.

Prediction of Target Genes in Guishen Decoction Bioactive Compounds

The TCMSP database was used to identify target genes of bioactive compounds found in Guishen Decoction, using the Universal Protein Knowledgebase in 2023 (UniProt; https: //www.uniprot.org/, accessed on 20 February 2024) [47] database normalizes the target gene names, deletes non-Homo sapiens category entries and duplicate entries, and organizes the final target gene list.

Prediction of Target Genes in Ischemic Stroke

Use “Ischemic stroke” as the keyword to search in the GeneCards ( https: //www.genecards.org/, accessed on 21 February 2024) [48] database, and filter the results based on Relevance score ≥ 1; use the same keyword to search in the Online Mendelian Inheritance in Man (OMIM; https: //omim.org/, accessed on 21 February 2024) [49], The Pharmacogenomics Knowledgebase (PharmGKB; https: //www.pharmgkb.org/, accessed on 21 February 2024) [50], Therapeutic Target Database (TTD; http: //db.idrblab.net/ttd/ , accessed on 21 February 2024) [51] and DrugBank (https: //go.drugbank.com/, accessed on 21 February 2024) [52] databases. The target gene lists of each database are summarized and redundant content is removed to ensure that the result list is comprehensive and not duplicated. The searches from each database were presented as Venn diagrams using R software.

Construction of Venn Diagram

Use the venn package of R 4.3.2 software to examine the targets of the ingredients in Guishen Decoction and the targets associated with ischemic stroke, and clarify the drug ingredient targets of Guishen Decoction that are related to ischemic stroke, the findings of the analysis are illustrated using a Venn diagram.

Construction of “Compound-Target-Disease” Network

Use Cytoscape 3.10.1 (https: //cytoscape.org/, accessed on 23 February 2024) software to illustrate the interaction between the drug ingredients of Guishen Decoction and ischemic stroke. The specific method is: classify and adjust the activated ingredient information of the compositions in Guishen Decoction and integrate the data into Cytoscape software enables the active ingredients of drugs to be visually displayed in Cytoscape; taking the drug ingredients of Guishen Decoction and the common target genes of ischemic stroke as network nodes, the relationship between the active ingredients of the drug and the common target genes is Displayed in the form of connecting lines, a “compound-target-disease” network is formed.

Protein-Protein-Interaction (PPI) Network Analysis

The STRING 12.0 (https: //cn.string-db.org/, accessed on 23 February 2024) database was used to analyze the intersection of bioactive compounds of Guishen Decoction and ischemic stroke target genes, and the analysis content was limited to human species, the confidence level is 0.7 and above, perform network visualization on the obtained protein, and enter the network into Cytoscape software. After integrating the data from the STRING database on the Cytoscape platform, use the CytoHubba plug-in [53] to calculate the Maximum Clique Centrality (MCC), Maximum Neighborhood Component (MNC) and degree values of each target gene, respectively determine the highest-ranking 10 genes with three algorithm scores, thereby determining potential central target genes in the network. The results of these three algorithms were copied into a set of target genes that were used as potential key targets in the network.

Gene Ontology and Pathway Enrichment Analysis

For the purpose of exploring the potential mechanism of action between the medicinal ingredients of Guishen Decoction and ischemic stroke, the Database for Annotation, Visualization, and Integrated Discovery database (DAVID), version 2021 (https: //david.ncifcrf. gov/home.jsp, accessed on 25 February 2024) [54] was deployed to analyze biological functions, cellular structures, molecular activities and signaling cascades [55-57] to obtain GO, and the first 15 results of KEGG analysis, using the Bioinformatic (https: //www.bioinformatics. com.cn, accessed on 25 February 2024) platform to visualize the results. After calculating the P value, statistically significant results have a P value of less than 0.05.

Molecular Docking

To analyse the interaction between the Guishen Decoction and the main genes specified via the UniProt database molecular connection is used to find the UniProt ID of the main gene., and the crystal structure of the core gene was searched in the RCSB protein database (https: //www.rcsb.org/, accessed on 25 February 2024) [58] based on the protein ID, resulting in IL6 (UniProt ID: P05231; PDB ID: 1ALU), TNF (UniPort ID: P01375; PDB ID: 1TNF), IL1B (UniProt ID: P01584; PDB ID: 1HIB). Import the three-dimensional structure of the core gene into PyMOL 2.5 (https: //pymol.org/, accessed on 25 February 2024) software, remove water molecules and existing small molecule ligands, and obtain the protein ligand file; use the PubChem database (https: //pubchem.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/, accessed on 25 February 2024) [59] to search Guishen Decoction active ingredients matrine, quercetin, kaempferol For 2D structure, ChemOffice 22 (https: // www.chemdraw.com.cn/, accessed on 25 February 2024) software was used to convert the 2D structure of the active ingredient into a three-dimensional structure, and the three-dimensional structure was optimized using minimum energy. Using the active ingredient as the ligand and the core gene as the receptor, AutoDockTools 4.2 (http: // autodock.scripps.edu/, accessed on 25 February 2024) [60] software was used to predict the binding conformation between the ligand and the receptor, and AutoDockVina 1.2.0 (https: //vina.scripps.edu/, accessed on 25 February 2024) [61,62] software was used to visualize the molecular interaction between the protein and the ligand.

Results

Identification and Screening of Active Compounds in Guishen Decoction

Search the active compounds of the Guishen Decoction drug according to the TCMSP website, and a total of 191 bioactive compounds were obtained. All results were screened and sorted using OB≥30% and DL≥0.18 as the filtering conditions. The UniProt website was adopted to identify the protein target names. After annotation, a total of 33 active ingredients were found in the whole prescription. After excluding the ingredients whose corresponding targets could not be found, the remaining 22 kinds were found. There were a total of 210 corresponding target proteins, which can be used for further analysis (Table 1).

Table 1: The pharmacokinetic properties of the bioactive ingredients of Guishen Decoction based on Traditional Chinese Medicine Systems Pharmacology (TCMSP) database and Uniprot database.

|

Drug |

Mol ID | Ingredient | Oral Bioavailability OB (≥30%) | Drug-Likeness DL (≥0.18) |

Target number |

| mulberry |

MOL010300 |

dIDP |

41.08 |

0.57 |

none |

| mulberry | MOL002372 | (6Z,10E,14E,18E)-2,6,10,15,19,23-hexamethyltetracosa- 2,6,10,14,18,22-hexaene |

33.55 |

0.42 |

none |

| mulberry | MOL006209 | cyanin |

47.42 |

0.76 |

2 |

| mulberry | MOL000737 | morin |

46.23 |

0.27 |

14 |

| mulberry | MOL002773 | beta-carotene |

37.18 |

0.58 |

none |

| mulberry | MOL000098 | quercetin |

46.43 |

0.28 |

136 |

| yam | MOL000310 | DenudatinB |

61.47 |

0.38 |

none |

| yam | MOL000322 | Kadsurenone |

54.72 |

0.38 |

22 |

| yam | MOL000449 | Stigmasterol |

43.83 |

0.76 |

27 |

| yam | MOL000546 | diosgenin |

80.88 |

0.81 |

15 |

| yam | MOL000953 | CLR |

37.87 |

0.68 |

3 |

| yam | MOL001559 | piperlonguminine |

30.71 |

0.18 |

8 |

| yam | MOL001736 | (-)-taxifolin |

60.51 |

0.27 |

3 |

| yam | MOL005429 | hancinol |

64.01 |

0.37 |

none |

| yam | MOL005430 | hancinoneC |

59.05 |

0.39 |

17 |

| yam | MOL005435 | 24-Methylcholest-5-enyl-3belta-O-glucopyranoside_qt |

37.58 |

0.72 |

1 |

| yam | MOL005438 | campesterol |

37.58 |

0.71 |

1 |

| yam | MOL005440 | Isofucosterol |

43.78 |

0.76 |

9 |

| yam | MOL005458 | DioscoresideC_qt |

36.38 |

0.87 |

2 |

| yam | MOL005461 | Doradexanthin |

38.16 |

0.54 |

none |

| yam | MOL005463 | Methylcimicifugoside_qt |

31.69 |

0.24 |

none |

| yam | MOL005465 | AIDS180907 |

45.33 |

0.77 |

10 |

| dodder seed | MOL001558 | sesamin |

56.55 |

0.83 |

20 |

| dodder seed | MOL000184 | NSC63551 |

39.25 |

0.76 |

1 |

| dodder seed | MOL000354 | isorhamnetin |

49.6 |

0.31 |

29 |

| dodder seed | MOL000358 | beta-sitosterol |

36.91 |

0.75 |

27 |

| dodder seed | MOL000422 | kaempferol |

41.88 |

0.24 |

54 |

| dodder seed | MOL005043 | campest-5-en-3beta-ol |

37.58 |

0.71 |

1 |

| dodder seed | MOL005440 | Isofucosterol |

43.78 |

0.76 |

9 |

| dodder seed | MOL005944 | matrine |

63.77 |

0.25 |

10 |

| dodder seed | MOL006649 | sophranol |

55.42 |

0.28 |

none |

| dodder seed | MOL000953 | CLR |

37.87 |

0.68 |

3 |

| dodder seed | MOL000098 | quercetin |

46.43 |

0.28 |

136 |

Target Gene Prediction of Ischemic Stroke

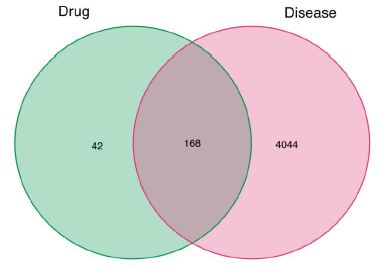

Through a comprehensive search of five databases: GeneCards, Online Mendelian Inheritance in Man (OMIM), The Pharmacogenomics Knowledgebase (PharmGKB), Therapeutic Target Database (TTD), and DrugBank, 4212 target genes related to ischemic stroke were collected (Figure 2).

Figure 2: The target genes of ischemic stroke based on Genecards, Online Mendelian Inheritance in Man (OMIM), The Pharmacogenomics Knowledgebase (PharmGkb), Therapeutic Target Database (TTD) and DrugBank databases.

Common Target of Guishen Decoction and Ischemic Stroke

Venn diagram was used to show the potential targets of Guishen Decoction for ischemic stroke (Figure 3). This figure shows 168 intersection target genes of Guishen Decoction and ischemic stroke.

Figure 3: The potential targets of between bioactive compounds of Guishen Decoction against ischemic stroke via Venn diagram. There are 168 target genes in Guishen Decoction bioactive compounds and ischemic intersection (the middle part).

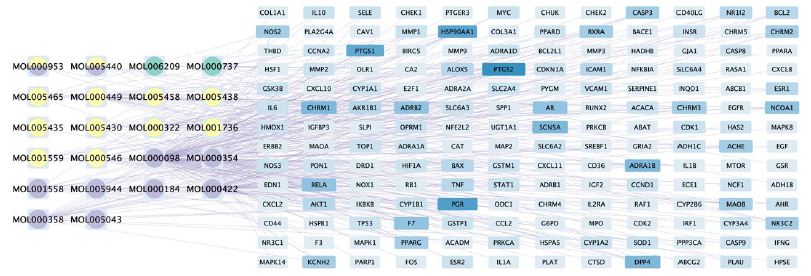

Compound-Target Network Constructions

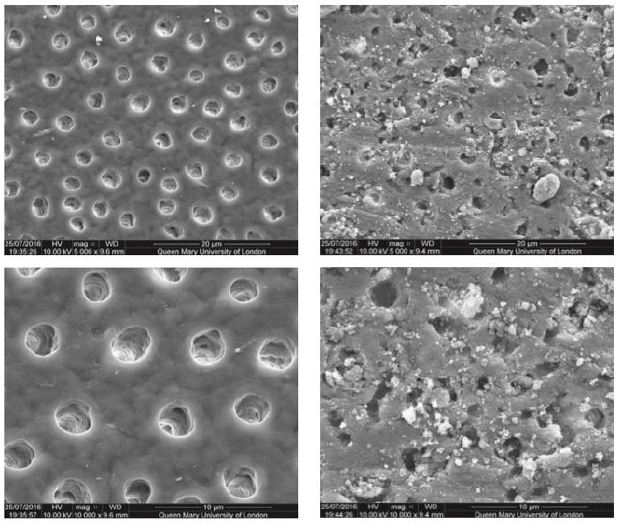

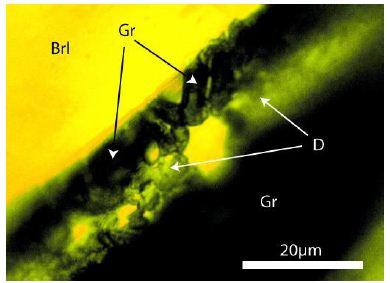

Cytoscape software was used to describe the interaction between the bioactive components of Guishen Decoction and its potential targets for the treatment of ischemic stroke (Figure 4).

Figure 4: The compound-target network of Guishen Decoction bioactive compounds against ischemic stroke by using Cytoscape. The blue nodes represent the interacting target genes between the compound (yellow, green and purple nodes) and the ischemic stroke. The yellow nodes represent the bioactive compounds belong to yam, the green ones belong to mulberry, the purple ones belong to dodder seed; the nodes containing multicolor indicate that the compound is shared by two or three drugs. The color and width of the square in gene targets represent the number of genes, with darker colors and wider widths indicating a greater number of genes.

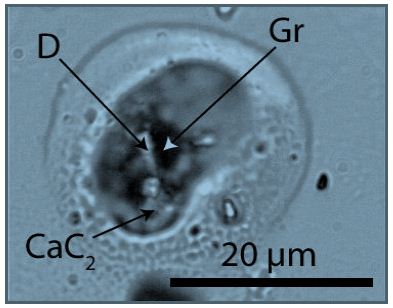

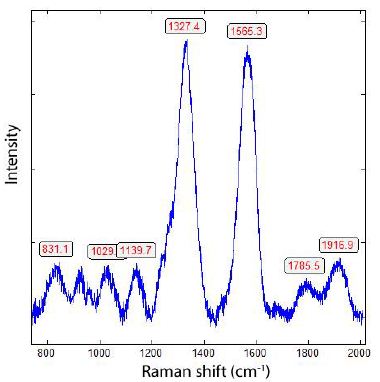

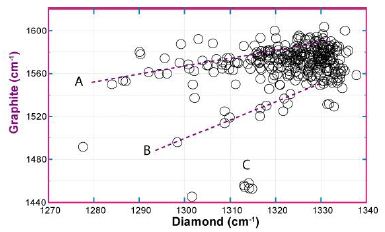

Protein-Protein Interaction (PPI) Network

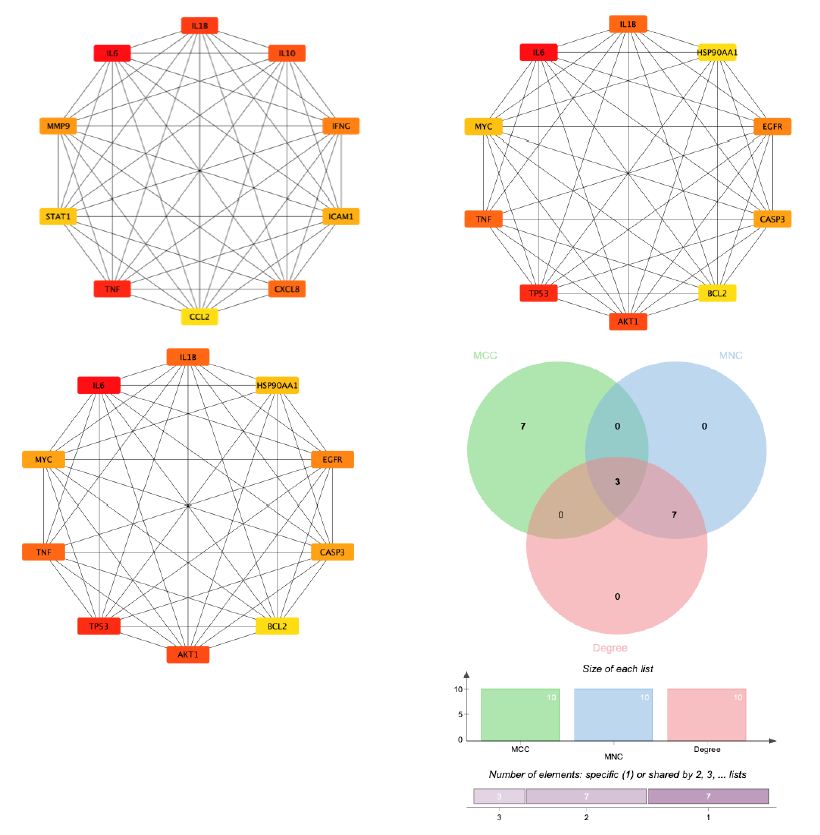

By employing the STRING database and Cytoscape software, we depicted the interaction network between the active compounds of Guishen Decoction and their potential targets for treating ischemic stroke through Protein-Protein Interaction (PPI) analysis (Figure 5). The resulting network has 168 nodes, with 1271 edges after hiding unconnected nodes representing proteins and protein-protein associations, compared to the expected 335 edges, meaning that network interactions for this 168 targets are significantly enriched, and indicates that the proteins are at least partially biologically connected, as a group. Use the CytoHubba plug-in in the Cytoscape software to assign scores to the Betweenness, Closeness, Degree, Eigenvector, Information and LAC values of the PPI network nodes, and filter out each score to be greater than the median. Targets were finally identified as 21 core targets of Guishen Decoction on ischemic stroke (Figure 6).

Figure 5: Protein-protein interaction networks are constructed using the STRING database. The network nodes represent proteins, each node represents all the proteins produced by a single, protein-coding gene locus. The colored nodes represent query proteins and first shell of interactors, and the white nodes representing the second shell of interactors. The edges represent protein- protein associations, the confidence levels of interaction are visually represented in the network diagram using color edges, including from curated databases, experimentally determined, gene neighborhood, gene fusions, gene co-occurrence, text-mining, co-expression and protein homology.

Figure 6: By combining 3 algorithms, MCC, MNC, degree, the key gene network of Guishen Decoction bioactive compounds with scores above the median for ischemic stroke was screened out. The genes with the highest values are considered the most important key genes and are indicated in yellow. Conversely, genes with lower values are considered less important and are indicated in blue, indicating each gene’s ranking position in the network.

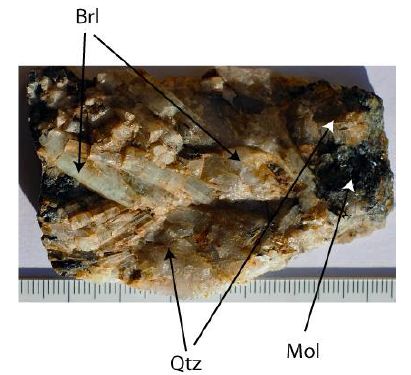

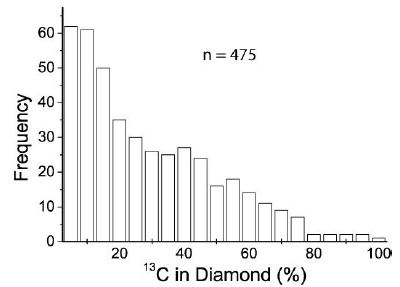

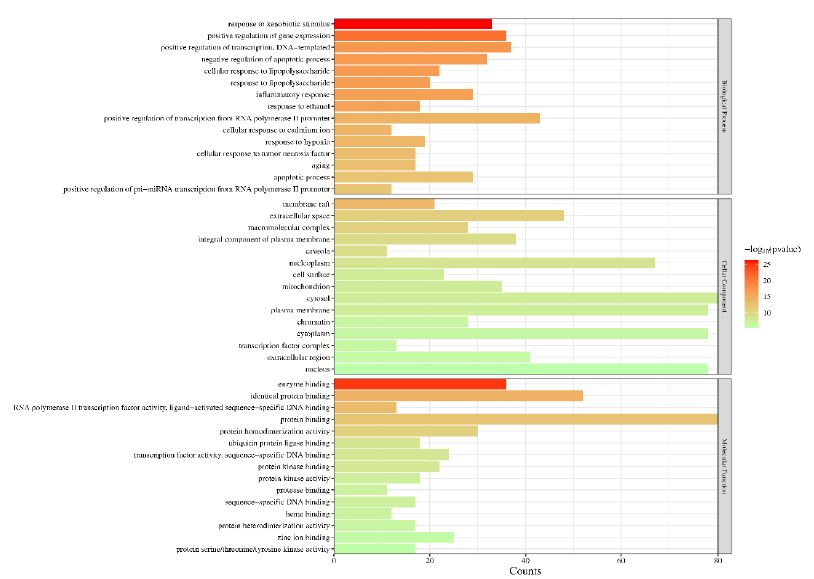

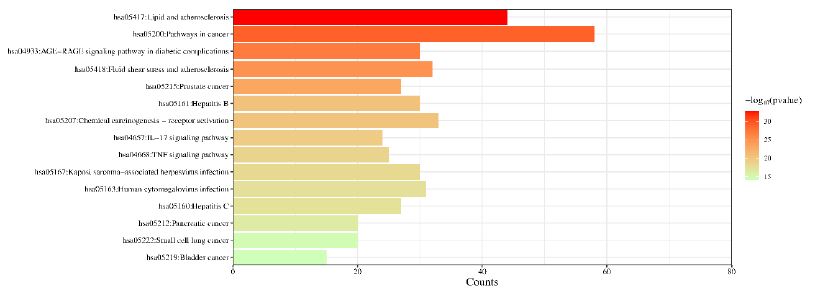

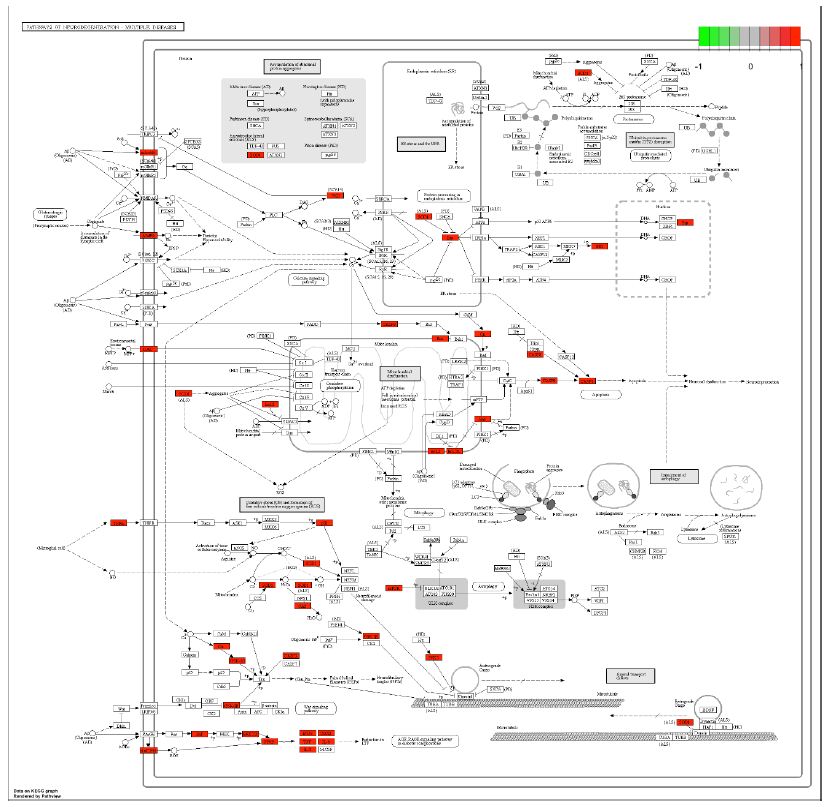

Gene Ontology and Pathway Enrichment Analysis

In order to further understand the biological processes, cellular components, molecular functions and pathways involved in the therapeutic effect of Guishen Decoction bioactive compounds on ischemic stroke, a Gene Ontology (GO) study and Kyoto Encyclopedia of Genes and Genomes (KEGG) pathway enrichment analysis was conducted using DAVID bioinformatics resources and the Bioinformatics platform. The results of GO analysis (Figure 7) show that the targets of the bioactive compounds in Guishen Decoction are the most significant biological processes related to xenobiotic stimulus and lipopolysaccharide. Analysis of cellular components showed that these targets mainly involved membrane raft, membrane microdomain and caveola. In terms of molecular function, the top 10 significantly enriched terms include DNA-binding transcription factor binding, G protein-coupled amine receptor activity and transcription coregulator binding. The results of KEGG analysis (Figure 8) show that many targets of the bioactive compounds of Guishen Decoction on ischemic stroke are enriched in signaling pathways, such as lipid and atherosclerosis, AGE-RAGE signaling pathway in diabetic complications, fluid shear stress and atherosclerosis and prostate cancer. Through the analysis of metabolic pathways, signaling pathways such as pathways of neurodegeneration are directly related to ischemic stroke. Find the potential targets and mechanisms of Guishen Decoction to treat ischemic stroke by regulating Pathways of neurodegeneration (Figure 9).

Figure 7: Gene ontology (GO) enrichment analysis. The bar chart represents the most significantly enriched GO terms in biological processes, cellular components, and molecular function, comprising the top 10 terms related to the target genes.

Figure 8: Kyoto Encyclopedia of Genes and Genomes (KEGG) pathway enrichment analysis. The bar chart visualizes the top 30 enriched KEGG pathways of Guishen Decoction against ischemic stroke.

Figure 9: Potential targets and mechanism of bioactive compounds in Guishen Decoction against ischemic stroke. The figure represents the neurotrophin signaling pathway. The red ndoes represent the genes targeted within the pathways of neurodegeneration.

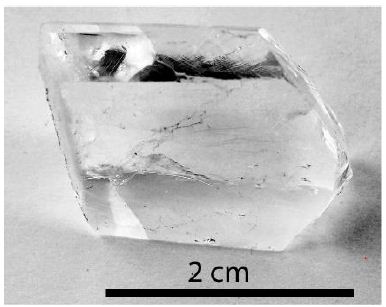

Molecular Docking

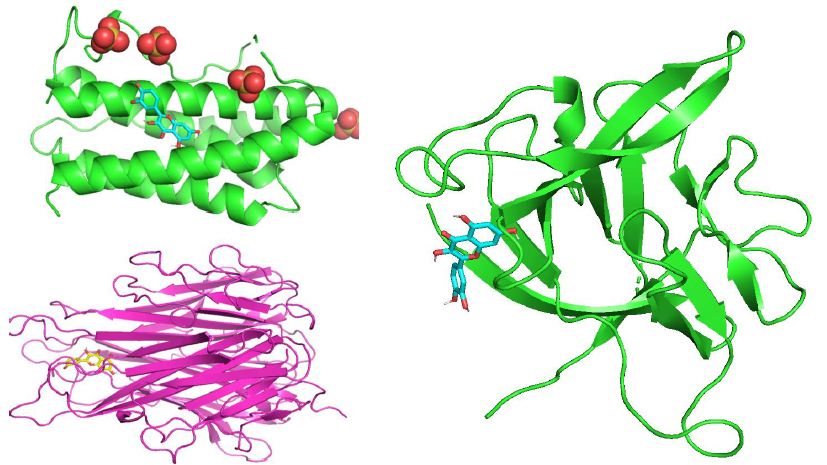

Through molecular docking research, the interaction relationship between the three active compounds selected in Guishen Decoction (matrine, kaempferol, quercetin) and three potential target genes (IL6, IL1B, TNF) was analyzed. AutoDockTools software was used to conduct molecular docking studies, and a total of 9 docking results were obtained, 7 of which had binding energies that resisted -5.0 kcal/ mol (Figure 10). The docking scores are shown in Table 2. The lower the binding energy, the tighter the binding between the compound and the protein. The binding energy of kaempferol and quercetin to each target gene is lower than -5.0 kcal/mol. Therefore, kaempferol and quercetin are important in the treatment of ischemic stroke. Play a particularly important role. The results show that most active ingredients have strong binding ability to the target gene TNF. The docking scores of kaempferol, matrine and quercetin combined with TNF are -6.6, -4.9 and -6.7 respectively. This result suggests that the bioactive compounds target TNF of Guishen Decoction may play a key role in the treatment of ischemic stroke. Use PyMOL to construct visualizations of the lowest binding energies between targets and bioactive compounds.

Figure 10: Molecular docking results of the lowest binding energy in each target with the bioactive compound of Guishen Decoction (a) IL6-quercetin, (b) IL1B-quercetin, (c) TNF-quercetin.

Table 2: Binding energy between active compounds and three core targets of Guishen Decoction.

| Compound |

Binding Energy (kcal/mol) |

||

| IL 6 | IL 1 B |

TNF |

|

| kaempferol |

-5. 5 |

-5. 4 |

-6. 6 |

| matrine |

-4. 7 |

-4. 3 |

-4. 9 |

| quercetin |

-5. 6 |

-5. 6 |

-6. 7 |

Discussion

The complexity of ischemic stroke’s mechanism is profound, and the process of damage to neurons and brain tissue is related to various programmed cell deaths such as apoptosis, pyroptosis, and ferroptosis. The basic process of this disease is that internal and external factors damage the brain, resulting in the interruption or reduction of local blood supply to the brain, and brain cells die due to the inability of the brain tissue to obtain oxygen and other nutrients [63]. Although r-tPA remains the most efficacious medication for treating this condition, only 11% of patients are eligible for its use due to the constraints imposed by the time window for intervention [64]. Therefore, finding alternative treatments for ischemic stroke from TCM is one of the important directions for the development of TCM in the new era.

Clinical work and related literature research have validated that Guishen Decoction has a definite therapeutic effect on ischemic stroke. In previous studies, researchers have confirmed the correlation between ischemic stroke and kidneys [65], TCM prescriptions can not only be used in the treatment of kidney disease [66], but also through the method of nourishing kidney and yin indirectly affects the brain [67], achieving the effect of protecting brain neurons. As a kidney- tonifying and essence- replenishing prescription, the medicinal composition of Guishen Decoction has the effect of inhibiting the activity of oxygen free radicals, suppressing the activation of microglia and astrocytes, and reducing inflammatory reactions. In order to verify the therapeutic effect of Guishen Decoction on ischemic stroke through further research, and to understand as fully as possible the target and mechanism of Guishen Decoction in the treatment of ischemic stroke, this study Network pharmacology and molecular docking technology were employed to study the positive effect of Guishen Decoction on the treatment of ischemic stroke.

After network pharmacology analysis, this study identified 191 potential bioactive compound targets of Guishen Decoction; in the network diagram, this article focused on three central targets: IL6, IL1B, and TNF. To elucidate the pharmacokinetic characteristics of Guishen Decoction bioactive decoder compounds in ischemic brain injury, this study used oral bioavailability (OB) ≥ 30% and drug-likeness (DL) ≥ 0.18 as the screening criteria, and Discard the remaining compounds whose corresponding targets cannot be obtained, and only summarize the remaining compounds as potential bioactive compounds. Three compounds, matrine, quercetin, and kaempferol, were selected from Guishen Decoction for further research because they meet the criteria for drug screening and may play an important role in the treatment of ischemic stroke.

Interpreting the KEGG pathway results in the process of GO and KEGG enrichment analysis shows that Apoptosis, Neurotrophin signaling pathway, Pathways of neurodegeneration, Glioma, lipids, IL-17 signaling pathway, HIF-1 signaling pathway, etc. have all been confirmed and lacking [68-70]. This article conducts visual research on related signaling pathways, and conducts molecular docking verification of 3 key targets and 3 active ingredients. The results show that quercetin and kaempferol play an important role in the treatment of ischemic stroke, as these compounds can be closely bound in the active pouch of key targets with low binding energy. At the same time, TNF looks relatively well with most of guishen’s active analgesics.

This article uses network pharmacology and molecular docking to study the potential active ingredients, possible relevant targets and important biological pathways of Guishen Decoction in the treatment of ischemic stroke, providing a preliminary theory for further experimental research. It must be noted that the pharmacological mechanisms proposed in this article are all derived from network pharmacology technology and require further verification by pharmacological and clinical studies.

Conclusions

In summary, this article uses network pharmacology and molecular docking methods to study the potential mechanism of the bioactive compounds of Guishen Decoction in the treatment of ischemic stroke. The results show that matrine, quercetin, Compounds such as kaempferol may have a therapeutic effect on ischemic stroke through key biological targets such as IL6, IL1B, and TNF. Molecular docking studies have shown that the active ingredients of Guishen Decoction can interact with these targets relatively effectively. These conclusions provide a valuable basis for further clinical and pharmacological research.

References

- Wang L, Zhang X, Xiong X, Zhu H, Chen R, et (2022) Nrf2 Regulates Oxidative Stress and Its Role in Cerebral Ischemic Stroke. Antioxidants (Basel, Switzerland) 11: 2377. [crossref]

- Merel S Ekker, Jamie I Verhoeven, Mijntje MI Schellekens, Esther M Boot, Mayte E van Alebeek, et al. (2023) Risk Factors and Causes of Ischemic Stroke in 1322 Young Stroke 54: 439-447. [crossref]

- Wen-Jun Tu, Zhenping Zhao, Peng Yin, Lei Cao, Jingsheng Zeng, et (2023) Estimated Burden of Stroke in China in 2020. JAMA Network Open 6: e231455. [crossref]

- Chuan Qin, Sheng Yang, Yun-Hui Chu, Hang Zhang, Xiao-Wei Pang, Lian Chen, et (2022) Signaling pathways involved in ischemic stroke: Molecular mechanisms and therapeutic interventions. Signal Transduction and Targeted Therapy 7: 215. [crossref]

- Gao L, Liu F, Hou P-P, Manaenko A, Xiao Z-P, Wang F, et (2022) Neurons Release Injured Mitochondria as ‘Help-Me’ Signaling After Ischemic Stroke. Frontiers in Aging Neuroscience 14: 785761. [crossref]

- Han Y, Li X, Yang L, Zhang D, Li L, Dong X, et (2022) Ginsenoside Rg1 attenuates cerebral ischemia-reperfusion injury due to inhibition of NOX2-mediated calcium homeostasis dysregulation in mice. Journal of Ginseng Research 46: 515-525. [crossref]

- Jurcau A, Simion A (2021) Neuroinflammation in Cerebral Ischemia and Ischemia/ Reperfusion Injuries: From Pathophysiology to Therapeutic Strategies. International Journal of Molecular Sciences 23:14. [crossref]

- Zhang B, Zhang H-X, Shi S-T, Bai Y-L, Zhe X, et al. (2019) Interleukin-11 treatment protected against cerebral ischemia/reperfusion Biomedicine & Pharmacotherapy Biomedecine & Pharmacotherapie 115: 108816. [crossref]

- Shi Y, Han L, Zhang X, Xie L, Pan P, et (2022) Selenium Alleviates Cerebral Ischemia/Reperfusion Injury by Regulating Oxidative Stress, Mitochondrial Fusion and Ferroptosis. Neurochemical Research 47: 2992-3002. [crossref]

- Li X, Ma N, Xu J, Zhang Y, Yang P, et (2021) Targeting Ferroptosis: Pathological Mechanism and Treatment of Ischemia-Reperfusion Injury. Oxidative Medicine and Cellular Longevity 2021: 1587922. [crossref]

- Zhao Y, Zhang X, Chen X, Wei Y (2022) Neuronal injuries in cerebral infarction and ischemic stroke: From mechanisms to treatment (Review). International Journal of Molecular Medicine 49: 15. [crossref]

- Powers WJ, Rabinstein AA, Ackerson T, Adeoye OM, Bambakidis NC, et al. (2019) Guidelines for the Early Management of Patients With Acute Ischemic Stroke: 2019 Update to the 2018 Guidelines for the Early Management of Acute Ischemic Stroke: A Guideline for Healthcare Professionals From the American Heart Association/ American Stroke Stroke 50. [crossref]

- Benjamin EJ, Blaha MJ, Chiuve SE, Cushman M, Das SR, et al. (2017) Heart Disease and Stroke Statistics-2017 Circulation 135: e146-e603. [crossref]

- Aleksandra Steliga, Przemysław Kowiański, Ewelina Czuba, Monika Waśkow, Janusz Moryś, et (2020) Neurovascular Unit as a Source of Ischemic Stroke Biomarkers— Limitations of Experimental Studies and Perspectives for Clinical Application. Translational Stroke Research 11: 553-579. [crossref]

- Derek Barthels, Hiranmoy Das (2020) Current Advances in Ischemic Stroke Research and Therapies. Biochimica et Biophysica Acta. Molecular Basis of Disease 1866: 165260. [crossref]

- Lena Bourhy, Aurélien Mazeraud, Fernando A Bozza, Guillaume Turc, Pierre-Marie Lledo, et (2022) Neuro-Inflammatory Response and Brain-Peripheral Crosstalk in Sepsis and Stroke. Frontiers in Immunology 13: 834649. [crossref]

- Ji Ma, Shaofeng Shui, Xinwei Han, Dong Guo, Tengfei Li, Lei Yan (2017) microRNA- 200a silencing protects neural stem cells against cerebral ischemia/reperfusion PloS One 12: e0172178. [crossref]

- Karantali E, Kazis D, Papavasileiou V, Prevezianou A, Chatzikonstantinou S, et (2021) Serum BDNF Levels in Acute Stroke: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Medicina (Kaunas, Lithuania) 57: 297. [crossref]

- Maria Calvo-Rodriguez, Elena Hernando-Pérez, Sara López-Vázquez, Javier Núñez, Carlos Villalobos, et al. (2020) Remodeling of Intracellular Ca2+ Homeostasis in Rat Hippocampal Neurons Aged In Vitro. International Journal of Molecular Sciences 21:1549. [crossref]

- SK Kritas, A Saggini, G Cerulli, A Caraffa, P Antinolfi, et (2014) Corticotropin- Releasing Hormone, Microglia and Mental Disorders. International Journal of Immunopathology and Pharmacology 27: 163-167. [crossref]

- Sebastian Zimmer, Philip Roger Goody, Matthias Oelze, Alexander Ghanem, Cornelius F Mueller, et (2021) Inhibition of Rac1 GTPase Decreases Vascular Oxidative Stress, Improves Endothelial Function, and Attenuates Atherosclerosis Development in Mice. Frontiers in Cardiovascular Medicine 8: 680775. [crossref]

- An-rong Wang, Lian-fang Mi, Zhi-lei Zhang, Ming-zhe Hu, Ze-yu Zhao, et (2021) Saikosaponin A improved depression-like behavior and inhibited hippocampal neuronal apoptosis after cerebral ischemia through p-CREB/BDNF pathway. Behavioural Brain Research 403: 113138. [crossref]

- Ling S-S, Pan R-H, Zhan L-C, Li M, Yang Z-J, et al. (2022) Ruyi Zhenbao Pills for Patients with Motor and Sensory Dysfunction after Stroke: A Double-Blinded, Randomized Placebo-Controlled Clinical Trial. Chinese Journal of Integrative Medicine 28: 872-878. [crossref]

- Li L, Liu Y, Zheng Y, Zhu J, Wu D, et al. (2023) Exploring the mechanisms under Zuogui Pill’s treatment of ischemic stroke through network pharmacology and in vitro experimental Frontiers in Pharmacology 14: 1153478. [crossref]

- Tang N-Y, Liu C-H, Liu H-J, Li T-C, Liu J-C, et al. (2012) Chinese medicine patterns in patients with post-stroke dementia. Journal of Traditional and Complementary Medicine 2: 123-128. [crossref]

- Saji SS, Abhishek DRR, Venkatesh KR (2016) Anti-Oxidant activity of various leaf extracts of mulberry species in rotenone induced oxidative stress model of rat. J Chem Pharm Sci 9: 2732-2736.

- Nade VS, Yadav AV (2010) Anti-stress effect of ethyl acetate soluble fraction of Morus alba in chronic restraint Pharmaceutical Biology 48: 1038-1046. [crossref]

- Nade VS, Kawale LA, Yadav AV (2010) Protective effect of Morus alba leaves on haloperidol-induced orofacial dyskinesia and oxidative stress. Pharmaceutical Biology 48: 17-22. [crossref]

- Turgut NH, Mert DG, Kara H, Egilmez HR, Arslanbas E, et al. (2016) Effect of black mulberry (Morus nigra) extract treatment on cognitive impairment and oxidative stress status of D-galactose-induced aging mice. Pharmaceutical Biology 54: 1052-1064. [crossref]

- Bauomy AA (2014) The potential role of Morus alba leaves extract on the brain of mice infected with Schistosoma mansoni. CNS & Neurological Disorders Drug Targets 13: 1513-1519. [crossref]

- Shih P-H, Chan Y-C, Liao J-W, Wang M-F, Yen G-C (2010) Antioxidant and cognitive promotion effects of anthocyanin-rich mulberry (Morus atropurpurea ) on senescence-accelerated mice and prevention of Alzheimer’s disease. The Journal of Nutritional Biochemistry 21: 598-605. [crossref]

- Rebai O, Belkhir M, Boujelben A, Fattouch S, Amri M (2017) Morus alba leaf extract mediates neuroprotection against glyphosate-induced toxicity and biochemical alterations in the brain. Environmental Science and Pollution Research International 24: 9605-9613. [crossref]

- El-Baz KF, Aly H, Khalil W, Booles H (2016) Neuroameliorative effects of berry extracts in Alzheimer induced Int J Pharma Bio Sci 7.

- Wattanathorn J, Muchimapura S, Thukhammee W, Tong-un T, Wannanon P, et (2012) Mulberry Fruits Protects Against Age-Related Cognitive Decline. American Journal of Applied Sciences 9: 1503-1511.

- Samuel SS, Desai A, Raghubir R, Kumar VR (2016) Neuroprotective profile of mulberry leaf extract in focal cerebral ischemia model in Indian Journal of Research in Pharmacy and Biotechnology 4: 116.

- Kang TH, Oh HR, Jung SM, Ryu JH, Park MW, et (2006) Enhancement of neuroprotection of mulberry leaves (Morus alba L.) prepared by the anaerobic treatment against ischemic damage. Biological & Pharmaceutical Bulletin 29: 270-274. [crossref]

- Kaewkaen P, Tong-Un T, Wattanathorn J, Muchimapura S, Kaewrueng W, et al. (2012) Effects of Mulberry Fruit Powder in Animal Model of American Journal of Agricultural and Biological Sciences 7: 322-329.

- Tam DNH, Nam NH, Elhady MT, Tran L, Hassan OG, et al. (2021) Effects of Mulberry on the Central Nervous System: A Literature Current Neuropharmacology 19: 193-219. [crossref]

- Hou L, Yang L, Zhu C, Miao J, Zhou W, Tang Y, et (2023) Cuscutae semen alleviates CUS-induced depression-like behaviors in mice via the gut microbiota- neuroinflammation axis. Frontiers in Pharmacology 14: 1107781. [crossref]

- Ju IG, Kim N, Choi JG, Lee JK, Oh MS (2019) Cuscutae Japonicae Semen Ameliorates Memory Dysfunction by Rescuing Synaptic Damage in Alzheimer’s Disease Nutrients 11: 2591. [crossref]

- Kim S, Shin S, Hyun B, Kong H, Han S, et (2012) Immunomodulatory Effects of Dioscoreae Rhizome Against Inflammation through Suppressed Production of Cytokines Via Inhibition of the NF-κB Pathway. Immune Network 12: 181-188. [crossref]

- Lee S-C, Tsai C-C, Chen J-C, Lin C-C, Hu M-L, et (2002) The evaluation of reno- and hepatoprotective effects of huai-shan-yao (Rhizome Dioscoreae). The American Journal of Chinese Medicine 30: 609-616. [crossref]

- Li S, Zhang B (2014) Traditional Chinese medicine network pharmacology: Theory, methodology and application. Chinese Journal of Natural Medicines 11: 110-120. [crossref]

- Liu C, Liu L, Li J, Zhang Y, Meng D-L (2021) Virtual screening of active compounds from jasminum lanceolarium and potential targets against primary dysmenorrhea based on network pharmacology. Natural Product Research 35: 5853-5856. [crossref]

- Ru J, Li P, Wang J, Zhou W, Li B, et (2014) TCMSP: A database of systems pharmacology for drug discovery from herbal medicines. Journal of Cheminformatics 6: 13. [crossref]

- Williams J, Siramshetty V, Nguyễn Ð-T, Padilha EC, Kabir M, et (2022) Using in vitro ADME Data for Lead Compound Selection: An Emphasis on PAMPA pH 5 Permeability and Oral Bioavailability. Bioorganic & Medicinal Chemistry 56: 116588. [crossref]

- Consortium U (2023) UniProt: The Universal Protein Knowledgebase in Nucleic Acids Research 51: D523-D531. [crossref]

- Safran M, Dalah I, Alexander J, Rosen N, Stein TI, et (2010) GeneCards Version 3: The human gene integrator. Database: The Journal of Biological Databases and Curation 2010: baq020. [crossref]

- Amberger JS, Bocchini CA, Schiettecatte F, Scott AF, Hamosh A (2015) org: Online Mendelian Inheritance in Man (OMIM®), an online catalog of human genes and genetic disorders. Nucleic Acids Research 43: D789-D798. [crossref]

- Barbarino JM, Whirl-Carrillo M, Altman, RB, Klein TE (2018) PharmGKB: A worldwide resource for pharmacogenomic information. Wiley Interdisciplinary Systems Biology and Medicine 10: e1417. [crossref]

- Zhou Y, Zhang Y, Zhao D, Yu X, Shen X, et (2024) TTD: Therapeutic Target Database describing target druggability information. Nucleic Acids Research 52: D1465-D1477. [crossref]

- Knox C, Wilson M, Klinger CM, Franklin M, Oler E, et (2024) DrugBank 6.0: The DrugBank Knowledgebase for 2024. Nucleic Acids Research 52: D1265-D1275. [crossref]

- Chin C-H, Chen S-H, Wu H-H, Ho C-W, Ko M-T, et al. (2014) CytoHubba: Identifying hub objects and sub-networks from complex interactome. BMC Systems Biology 8: S11. [crossref]

- Sherman BT, Hao M, Qiu J, Jiao X, Baseler MW, et (2022) DAVID: A web server for functional enrichment analysis and functional annotation of gene lists (2021 update). Nucleic Acids Research 50: W216-W221. [crossref]

- Dennis G, Sherman BT, Hosack DA, Yang J, Gao W, Lane HC, et (2003) DAVID: Database for Annotation, Visualization, and Integrated Discovery. Genome Biology 4: R60. [crossref]

- Huang DW, Sherman BT, Lempicki RA (2009) Systematic and integrative analysis of large gene lists using DAVID bioinformatics Nature Protocols 4: 44-57. [crossref]

- Kanehisa M, Furumichi M, Sato Y, Kawashima M, Ishiguro-Watanabe M (2023) KEGG for taxonomy-based analysis of pathways and Nucleic Acids Research 51: D587-D592. [crossref]

- Berman HM, Westbrook J, Feng Z, Gilliland G, Bhat TN, et al. (2000) The Protein Data Nucleic Acids Research 28: 235-242.

- Kim S, Chen J, Cheng T, Gindulyte A, He J, et (2021) PubChem in 2021: New data content and improved web interfaces. Nucleic Acids Research 49: D1388-D1395. [crossref]

- Morris GM, Huey R, Lindstrom W, Sanner MF, Belew RK, et (2009) AutoDock4 and AutoDockTools4: Automated docking with selective receptor flexibility. Journal of Computational Chemistry 30: 2785-2791. [crossref]

- Eberhardt J, Santos-Martins D, Tillack AF, Forli S (2021) AutoDock Vina 1.2.0: New Docking Methods, Expanded Force Field, and Python Bindings. Journal of Chemical Information and Modeling 61: 3891-3898. [crossref]

- Trott O, Olson AJ (2010) AutoDock Vina: Improving the speed and accuracy of docking with a new scoring function, efficient optimization, and multithreading. Journal of Computational Chemistry 31: 455-461. [crossref]

- Rui Mao, Ningning Zong, Yujie Hu, Ying Chen, Yun Xu (2022) Neuronal Death Mechanisms and Therapeutic Strategy in Ischemic Neuroscience Bulletin 38: 1229-1247. [crossref]

- Zhao F, Peng C, Li H, Chen H, Yang Y, et (2023) Paeoniae Radix Rubra extract attenuates cerebral ischemia injury by inhibiting ferroptosis and activating autophagy through the PI3K/Akt signaling pathway. Journal of Ethnopharmacology 315: 116567. [crossref]

- T Olsson, N Marklund, Y Gustafson, B Näsman (1992) Abnormalities at different levels of the hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenocortical axis early after stroke. Stroke 23: 1573-1576. [crossref]

- Yang L, Wang B, Ma L, Fu P (2022) Traditional Chinese herbs and natural products in hyperuricemia-induced chronic kidney Frontiers in Pharmacology 13: 971032. [crossref]

- Liu Y, Wu D, Yan X, Xu X, Zhu J, et al. (2024) Zuogui Pill Promotes Neurite Outgrowth by Regulating OPN/ IGF-1R/PTEN and Downstream mTOR Signaling Combinatorial Chemistry & High Throughput Screening. [crossref]

- Cui Y, Zhang Y, Zhao X, Shao L, Liu G, Sun C, et al. (2021) ACSL4 exacerbates ischemic stroke by promoting ferroptosis-induced brain injury and Brain, Behavior, and Immunity 93: 312-321. [crossref]

- Ghosh MK, Chakraborty D, Sarkar S, Bhowmik A, Basu M (2019) The interrelationship between cerebral ischemic stroke and glioma: A comprehensive study of recent Signal Transduction and Targeted Therapy 4: 42. [crossref]

- Yang C, Hawkins Ke, Doré S, Candelario-Jalil E (2019) Neuroinflammatory mechanisms of blood-brain barrier damage in ischemic stroke. American Journal of Physiology. Cell physiology 316. [crossref]