DOI: 10.31038/AWHC.2024711

Abstract

Background: Climate change poses a significant threat to communities across the globe. Whereas low and middle income countries contribute the least to this problem, they are often most affected by the consequences. In addition, women are often disproportionately affected by climate change-related occurrences. To address these issues, Women Climate Centers International (WCCI) Uganda initiated a project to empower women through the promotion of climate change solution enterprises in Uganda. The purpose of this research was to establish the impact of this approach on women social and economic empowerment and quality of life.

Methods: The study employed a cross-sectional approach, collecting both quantitative and qualitative data among 96 women purposively selected for their involvement in WCCI climate-smart enterprises in Uganda. A digitized structured questionnaire was used to gather quantitative data while a structured Focus Group Discussion (FGD) guide were used to aid qualitative data collection. The quantitative data was analyzed statistically using Stata version 15 to provide descriptive and statistics while Atlas ti9 was used to thematically analyze the qualitative data after transcribing of audios recorded during the interviews.

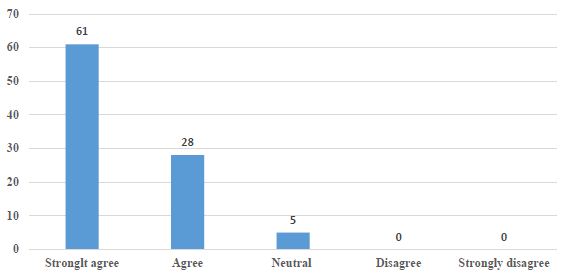

Results: About 38% (36/96) of the women make briquettes, 51% (49/96) make soap and 95.8% (92/96) are generating income from the enterprises. More than half 59.4% (57/96) of the women are confident in running their businesses sustainably while 38.5% (37/96) had trained 4-5 community women each, with the knowledge obtained from the satellites. Over 62% (59/96) of women strongly agreed to an improved sense of belonging within their community, 94.8% (91/96) noticed an improvement in their community engagement and collaboration while 63.5% (61/96) strongly agreed to better treatment from family and neighborhood. Conversely, 22.9% (22/96) of the women had ever experienced intimate or gender-based violence in their life, half of these had experienced it in the previous six months, but only 18.2% (2/11) would attribute their recent experience to engaging in entrepreneurship under WCCI. Economically, 57.3% (55/96) of the women saw a significant increase in their income, and 56.3% (54/96) in their household income. About 76% (73/96) had acquired some personal or household assets using income from the enterprises, and 65% (62/96) had joined a women’s group, Savings and Credit Cooperative Organization (SACCO), or local governing bodies since their training with WCCI. Furthermore, 82.3% mentioned that there was a positive difference in the way their husbands treated them ever since they attained financial independence. Lastly, the majority of the women, 63.6% (61/96) strongly agreed, and 29.2% (28/96) agreed that their quality of life and well-being had improved since becoming part of the climate change solution satellites. The qualitative findings strongly corroborated the quantitative.

Conclusions: Overall, participation in these entrepreneurial initiatives has brought about tangible improvements in social cohesion, economic empowerment, and the perceived quality of life and well-being for a significant majority of women involved, demonstrating the positive impact of the WCCI climate change solution satellites on their lives and communities.

Keywords

Women-led, Climate change solution satellites, Entrepreneurship, Empowerment

Introduction and Background

Globally, women and girls from marginalized communities face intersecting challenges related to gender inequalities, economic empowerment, and the profound impacts of climate change [1-3]. Regarding climate change, the complex web of vulnerabilities that these women encounter is rooted in a global context where women are both disproportionately affected by the adverse consequences but underrepresented in efforts to address and mitigate these effects [4]. The African region has witnessed an increase in average temperatures, changes in rainfall patterns, and an increase in extreme weather events such as floods, droughts, and conflicts over natural resources, which exert a disproportionate toll on the developing world including Uganda [3,5,6]. These climate shocks have significant implications for agriculture, food security and livelihoods [1,7] and burdensome for women, as they play crucial roles in agricultural production, water collection, natural resource management, and household well-being [8].

While the concept of climate-smart enterprises is gaining traction in East Africa, women-led initiatives in this sector remain scarce [9]. Recognizing the critical need to address these interconnected challenges, Women Climate Centers International (WCCI) [10], embarked on a transformative initiative in Uganda. This initiative sought to empower women through comprehensive training encompassing climate-smart solutions, livelihood strategies, and economic and social empowerment. In the first project year, WCCI has engaged 100 women and girls organized in 10 women-led grassroots groups that belong to 3 different satellites (Gomba, Butambala and Mukono), seamlessly integrating women’s entrepreneurship with grassroots climate resilience initiatives. Through these groups, WCCI conducted extensive trainings, emphasizing climate-smart solutions, livelihoods, and economic and social empowerment, leadership, and management, and fundamental entrepreneurship skills. WCCI trained the women in making climate-smart products such as briquettes, liquid and bar soap, herbal vaseline, fireless stoves, water tanks/jars, and bio-sand filters. The women were also trained to engage in Vermiculture, Agroforestry farming, and Bio-intensive farming including double digging, moist gardens, sack gardens, mixed cropping and mushroom growing, apiary (and liquid manuring year-round food production. Furthermore, WCCI Uganda facilitated the establishment and registration of the 10 women-led enterprises, with full support throughout the registration process. This registration made these enterprises eligible for government funding via the community demand-driven development funds especially the Parish Development Model [11]. WCCI offered 4 full days of training in business development and planning to all 100 women to ensure that they have the needed skills to develop, plan, and run their businesses. WCCI also provided vital business support equipment tailored to each satellite’s needs, ensuring they could efficiently produce, sell, and thrive. Importantly, these innovative approaches are expected to extend WCCI’s impact beyond parishes, fostering sustainable social and economic empowerment and quality of life within communities.

This innovative approach aimed to foster community-driven strategies from a single learning and training center (satellite) for long-term climate adaptation, mitigation, and resilience, including carbon sequestration. Through targeted training programs, mentorship, access to finance, and networking opportunities, women can enhance their entrepreneurial capabilities, understand the principles of climate-smart practices, and develop innovative business models that are environmentally sustainable and socially inclusive. Ultimately, by fostering the establishment of women-led climate smart enterprises, Uganda can unlock the untapped potential of women, create sustainable livelihoods, and promote economic resilience and sustainable practices in the face of climate change. Central to this initiative is the aspiration to establish women-led climate-change solution enterprises, recognizing the critical role women can play in driving economic growth, creating employment opportunities, and advancing gender equality and social inclusion. By aligning with Uganda’s National Development Plan 3 [12], these enterprises aim to serve as catalytic models for sustainable community development.

As these enterprises continued on their transformative journey, it was essential to evaluate the holistic impact on the social and economic empowerment and quality of life of the women involved, as well as any unintended consequences such as gender-based violence. The research sought to illuminate the transformative potential of the one-stop climate change solution center model, exemplified by these satellite initiatives, to contribute insights to inform future initiatives, strengthening WCCI’s mission to empower women and communities in their pursuit of climate resilience, economic growth, and enhanced overall wellbeing.

The Study Methods

Study Design and Study Area

The study employed a cross-sectional approach, collecting both quantitative and qualitative data from the women. The study was conducted in the three intervention groups including Gomba, Butambala and Mukono. The three districts are located in the central region of Uganda. Gomba district is a rural district which was formed in 2010 by an Act of Parliament, breaking away from Mpigi District. It is bordered by Mubende District to the west and north, Mityana District to the northeast and Butambala District to the east. Kalungu district, Bukomansimbi district and Sembabule district lie to the south of Gomba district. The district lies approximately 97 kilometers (60 mi), by road, southwest of Kampala, the capital and largest city of Uganda. Gomba district receives lower precipitation than the neighbouring districts and livestock farming is a major economic activity, supplemented with subsistence agriculture [13]. Butambala district was too created by an act of parliament, and became operational on 1 July 2010, having been split off of Mpigi district. This district is bordered by Gomba district to the west and north-west, Mityana District to the north-east, Mpigi District to the east and south, and Kalungu District to the south-west. The district headquarters at Gombe are approximately 68 kilometers (42 mi), by road, south-west of Kampala. Subsistence agriculture and small-scale animal husbandry are the backbone of Butambala district’s economy [14]. Mukono district is one of the fastest growing areas in Uganda and is located along the Kampala-Jinja highway. The district is bordered by Kayunga district to the north, Jinja district to the east, Kalangala district to the south-west, Kira Town and Wakiso district to the west, and Luweero district to the north-west. The town of Mukono is about 21 kilometers (13 mi) by road, east of Kampala. The district has a favorable climate, abundant rainfall, rich flora and fauna, and proximity to urban areas [15].

Study Population

Data was collected from women actively engaged in climate change solution satellites supported by Women Climate Centers International (WCCI) Uganda.

Sample Size and Sampling

Of the 100 women currently supported by through the satellites, 96 were engaged in this study and 4 were unavailable at the time of data collection. All the 96 participants were selected purposively because of being beneficiaries of the program. Both quantitative and qualitative data were collected from the same participants.

Data Collection Criteria

A digitized Kobo collect toolbox questionnaire was used to conduct surveys with the participants to gather quantitative data on specific aspects of their experiences and observations related to the contribution of climate change solution satellites. The surveys included predefined questions covering areas such as economic empowerment, social cohesion and collaboration, climate change knowledge, and quality of life.

Qualitatively, a structured Focus Group Discussion (FGD) guide was used to elicit data to complement the surveys. A total of six FGDs were conducted, two per district and each FGD comprised 10 women. The FGDs were moderated by a male qualitative data collection expert who was assisted by a female note taker. These FGDs were conducted in Luganda, the local dialect, and focused on open-ended questions that encouraged participants to share their experiences and perceptions in more detail.

Quality Control and Assurance

Both qualitative and quantitative tools were translated to Luganda and the researchers ensured to only recruit research assistants who were conversant with Luganda, the local dialect. Research assistants with a good command of English were recruited to conduct interviews, however, the interviews were conducted in a language most comfortable to the respondent. Research assistants were trained on the research protocol and ethical issues surrounding the study. To ensure data accuracy and consistency, the digitized tool was designed with skips, hints, and prompts to ensure that the research assistants filled in the data the way they were supposed to. Furthermore, the research assistants were supervised during the actual data collection exercise. The supervisors ensured that the tool was checked and field edited, if necessary, to ensure completeness of data before data entry.

Data Management and Analysis

Quantitative Data: Quantitative data was field edited for consistency and accuracy daily. Data materials were secured under lock and key and were only accessed by the study team. The data was downloaded from the Kobo collect web-based server, accessible on the link; (https://eu.kobotoolbox.org/#/forms/aN7ejaQfnbe4dGyp53YySM/data/table) and loaded onto Microsoft Excel for further cleaning and visualization. The data was then imported to STATA version 15 for statistical analysis. Descriptive analysis was done to generate the mean and the standard deviation for continuous variables and proportions for categorical variables. Frequency tables as well as figures were used to present these results.

Qualitative Data: All qualitative interviews were digitally recorded with permission from respondents and transcribed verbatim. The transcripts were proofread before importing them into a qualitative data management software-Atlas.ti9. Data coding and analysis were conducted subsequently. An initial codebook using a sample of two transcripts was developed. The developed codebook was then applied to the entire atlas project with any emerging codes being added in the process. Thematic analysis was used and results were presented using themes with typical quotations from different interviews to summarize social cohesion and collaboration, economic empowerment, and quality of life and well-being.

Results

Socio-demographic Characteristics of the Study Respondents

A third 33.3% (32/96) of the women were aged between 26-30 years, 44.8% (43/96) were of the Anglican religion, 67.7% (65/96) were married and 75% (72/96) had attained the primary level of education. The majority 41.8% (40/96) were from Gomba district (Table 1).

Table 1: Socio-demographic characteristics of the women engaged in climate change solution satellite enterprises in Uganda.

|

Variable

|

Category |

Frequency (n=96) |

Percentage (%)

|

| Age |

18-25 |

13

|

13.5

|

|

26-30

|

32

|

33.3

|

| 31-35 |

27

|

28.1

|

| 36+ |

24

|

25.0

|

| Religion |

Anglican |

43

|

44.8

|

| Catholic |

29

|

30.2

|

| Pentecostal |

17

|

17.7

|

| Muslim |

7

|

7.3

|

| Marital status |

Never married |

16

|

16.7

|

| Married |

65

|

67.7

|

| Separated/divorced |

15

|

15.6

|

| Education level |

Primary level |

72

|

75%

|

| Secondary level |

22

|

22.9

|

| Tertiary level |

2

|

2.1

|

| District of residence |

Gomba

|

40

|

41.8

|

| Butambala |

26

|

27.1

|

| Mukono |

30

|

31.3

|

Status of Women-led Climate Solution Satellite

Table 2 shows the status of the women-led climate change solution satellites in Uganda. All women involved in the study were part of a satellite. About 38% (36/96) were engaged in briquette making while 51% (49/96) were making soap. The majority of the respondents 70.8% (68/96) mentioned that their enterprises were registered with the district authorities while 95.8% (92/96) mentioned that their businesses were generating them income. About 18% (17/96) faced taxes and licensing as a main challenge, 13% (12/96) faced issues with the market for their products while 11.5% (11/96) found scaling and growth difficult. Additionally, on a scale of 1-10, the mean(SD) level of confidence to run the enterprise sustainably was 6.8(1.81), while 59.4% (57/96) of the women rated their confidence between 7-10. More than a third of the women, 38.5% (37/96) had trained up to 5 or more community women each, with the knowledge obtained from the satellites.

Table 2: Status of Women-led Climate Solution Satellites in Uganda

|

Variable

|

Categories

|

Frequency (n=96) |

Percentage (%)

|

| Climate change solution – products being made |

Briquettes |

36

|

37.5

|

| Water tanks/bio-sand filters |

2

|

3.1

|

| Fireless cook stoves |

9

|

13.9

|

| Agro-forestry farming |

11

|

16.9

|

| Bio-intensive farming |

3

|

4.6

|

| Soap making |

49

|

51.0

|

| Others |

17

|

26.1

|

| Enterprise registered with the district authorities? |

Yes |

68

|

70.8

|

| No |

28

|

29.2

|

| Is the business generating you any income yet |

Yes |

92

|

95.8

|

| No |

4

|

4.2

|

| Challenges faced in running the enterprise |

Taxes and licensing |

17

|

17.7

|

| Market for products |

12

|

12.5

|

| Scaling and growth |

11

|

11.5

|

|

Risk management

|

9

|

13.9 |

|

Others

|

1

|

1.5

|

| Rate your level of confidence in running the enterprise sustainably

Mean(SD)=6.80(1.81) |

1-3 |

4

|

4.2

|

| 4-6 |

35

|

36.5 |

|

7-10

|

57 |

59.4

|

| Number of women personally trained with the knowledge from the satellite |

0-1 |

40

|

41.7 |

|

2-3

|

19 |

19.8

|

| 4-5 |

37

|

38.5

|

Qualitatively, six focus group discussions were held with the women. These brought forward insights across the three districts of Gomba, Butambala, and Mukono, highlighting the collaborative nature of product-making among small groups, both for personal gain and communal development. Participants emphasized mutual support, group training, and the positive impact of acquired skills, enabling them to engage in various income-generating activities, from making briquettes and soap to cultivating vegetables and trees. Notably, the cultivation of home vegetables emerged as a significant achievement, not only economically but also in enhancing household food security and familial support. Respondents were quoted saying;

“We are in groups; some are of 10 people others 15 but not more than that. In most cases we do our things together, as in as the big group for the district. We come together for trainings and even for making our products. We support each other in case one of us has a problem. Most of us make these products as a group but also as individuals and we sell them in our communities.” (Participant 1, FGD, Gomba district)

“They told us to assist 5 other women each and some of us have gone beyond that. We gather the women and teach them. Sometimes, you team up with a politician and they help to teach the people which encourages community development.” (Participant 3, FGD, Gomba district)

“Ever since we joined the trainings, we learned so much. We make briquettes, liquid soap, tablet, and bar soap, we also make Vaseline. We have done so many things which have helped us to generate income and save.” (Participant 1, FGD, Butambala)

“We also cultivate nursery beds; we donate and plant some of our trees in schools freely. We make charcoal, soap, and cooking stoves and sell them to people. We also cultivate leafy vegetables because almost all the ladies here have homegrown vegetables, which they sell to people.” (Participant 2, FGD, Gomba)

“The cultivation of home vegetables is so good because it’s amazing for visitors when they find your yard full of vegetables. Then our husbands used to purchase vegetables from the market when they found those that they liked like Nakatti, but now they find it at home.” (Participant 3, FGD, Gomba)

“I have found growing crops as the easiest for me. We were taught how to look after banana plants, and coffee plants, which helped us to cultivate even without fertilizers since we use the home trash as manure in our gardens to be able to pay our children’s school fees.” (Participant 8, FGD, Mukono)

Social Cohesion and Community Engagement among the Women

The majority of the women, 61.5% (59/96) strongly agreed that their participation in the women-led climate change solution satellites had improved their sense of belonging within their community, 94.8%% (91/96) noticed an improvement in their community engagement and collaboration since their involvement in the enterprise, while 63.5% (61/96) strongly agreed that their family treats them better ever since joining the satellites. A similar proportion further strongly agreed that people in their neighborhoods treat them better since joining the women-led climate change solution satellites (Table 3).

Table 3: Social cohesion and community engagement among the women engaged in climate change solution satellites.

|

Variable

|

Category

|

Frequency (n=96) |

Percentage

(%)

|

| Participation in the women-led climate change solution satellite improved my sense of belonging within my community. |

Strongly agree |

59

|

61.5 |

|

Agree

|

34 |

35.4

|

| Neutral |

3

|

3.1 |

|

Noticed an improvement in community engagement and collaboration since involvement in the satellite activities?

|

Strongly agree

|

41 |

42.7

|

|

Agree

|

50 |

52.1 |

|

Neutral

|

5 |

5.2

|

| My family treats me better since joining the women-led climate change solution satellite |

Strongly agree |

61

|

63.5 |

|

Agree

|

29 |

30.2

|

| Neutral |

6

|

6.3 |

|

People in my neighborhood treat me better since joining the women-led climate change solution satellite

|

Strongly agree

|

61 |

63.5

|

| Agree |

32

|

33.3 |

|

Neutral

|

3 |

3.1

|

The narratives from the FGDs revealed profound shifts in social dynamics due to the collaborative efforts within WCCI projects. Participants emphasized the development of robust relationships transcending geographical boundaries. The once fragmented communities now exhibit solidarity, as evidenced by the warm welcome received in various households across different towns. Moreover, the newfound friendships extended beyond project members, fostering positive interactions with neighboring villages. This solidarity was born from a spirit of collaboration, where knowledge sharing and support became the norm. The collective efforts in constructing local stoves and utensil stands showcased a shared commitment to cleanliness and community welfare. The projects acted as catalysts for forming friendships, bridging gaps, and nurturing a sense of mutual admiration and respect, ultimately enhancing social cohesion and fostering a network of supportive relationships within these communities.

“We have developed very good relationships, I live in Kanyonyi town council, and I didn’t know any ladies from Kifampa, Mpenja or Kabulassobi, but as of now, once you arrive at the home of one of your project colleagues, even their children welcome you to the home which portrays a good working relationship. Additionally, on the villages where we train ladies, the relationships there are very good because back then ladies used to be very jealous of us, but right now they are not jealous anymore. They realize that once we learn something, we mobilize and teach them, which has improved our relationships with people so much, and even their husbands are very supportive of us because they see the good we are doing with their wives.” (Participant 5, FGD, Gomba”

This project has aided us so much as ladies, we mobilize ourselves and go to a colleague’s home and construct for them a local stove, and a utensil stand all in the fight for cleanliness. (Participant 7, FGD, Butambala)

“The people in the places where we reside became our friends. They know when we are supposed to come for the project meetings and even remind us. Some ladies come to us and want to support us while others request to join our program. We are admired and we are held in high regard wherever we reside.” (Participant 1, FGD, Mukono)

“We have made friends we wouldn’know if it wasn’t for this project. We have made friends from various communities, so I am personally happy about this.” (Participant 8, FGD, Gomba)

Intimate Partner and Gender-Based Violence Experiences

Table 4 shows experiences related to an intimate partner or gender-based violence. Overall, 22.9% (22/96) of the women had ever experienced intimate/ gender-based violence in their life. Of these, half, 50% (11/22) had experienced it in the previous six months, but only 18.2% (2/11) would attribute their experience to engaging in entrepreneurship. The majority 74% (71/96) of the respondents agreed that they have seen an improvement in the way their husbands treat them since they joined the satellites.

Table 4: Intimate partner and Gender-Based violence experiences among the women engaged in climate change solution satellites in Uganda.

|

Variable

|

Category |

Frequency (n=96) |

Percentage

(%)

|

| Ever experienced any intimate partner or gender-based violence in your life |

Yes |

22

|

22.9 |

|

No

|

74 |

77.1

|

| Experienced any intimate partner or gender-based violence in the last 6 months. |

Yes |

11

|

50.0 |

|

No

|

11 |

50.0

|

| Would you attribute this violence to your engagement in entrepreneurship |

Yes |

2

|

18.2 |

|

No

|

9 |

81.8

|

| Noticed improvement in the way my partner treats me since I joined WCCI |

Strongly agree |

11

|

11.5 |

|

Agree

|

71 |

74.0

|

| Neutral |

8

|

8.3 |

|

Strongly disagree

|

6 |

6.2

|

The narratives indicate a tangible positive impact on reducing intimate partner and gender-based conflicts through increased education, shared responsibilities, financial empowerment, and altered perceptions of women’s roles within their households and society. Participants noted a distinct transformation in family dynamics, citing fewer reported cases of marital conflicts and domestic violence since the inception of the programs. Increased education and engagement in income-generating activities emerged as pivotal factors redirecting attention away from potential conflict points. The shared responsibilities and shared understanding cultivated through the trainings contributed to more harmonious households, characterized by decreased tension and fewer disputes over childcare and financial obligations. Moreover, the financial independence and changed perceptions of women’s value within households led to a shift in power dynamics, generating respect and diminishing instances of disrespect and marital discord.

“I am the senior woman in my community and back then I was always called to settle cases of women fighting with their husbands all the time, but ever since we started mobilizing ladies to come for these project trainings, ladies now have what things to do. To be honest I have now spent 5 months without being called for such family fights, but before, I used to attend to cases for like 2 families each day. Right now, those cases are unheard of, even at the police station ladies are no longer reporting such cases, which is a good change that’s been brought by these projects.” (Participant 5, FGD, Gomba)

On the issue of family fights, ever since I started coming for these projects, I got enough education to now understand how to handle my family. Secondly, I have things that take up my time compared to the gossip I used to be involved in to try and find out what my husband has been up to. I now have things to occupy me because if I am not doing home chores, I am running my businesses which takes up most of my time and leaves me no time for fights. I now have a lot to do to avoid such fights at home.” (Participant 7, Mukono)

“… before we used to be fighting with the men to take care of the children and their fees. But now we came to terms with our husbands, and they too got some education about shared responsibilities and now there is less fighting in homes. Life has really changed so much.” (Participant 4, FGD, Butambala)

“To add on, even my own husband now sees high value in me and cannot easily mess around with other women. This is because he must first consider whether the person he is messing with can favorably compete with me, and these projects have weighed us up so much on the men’s weighing scale, for which I am so grateful.” (Participant 10, FGD, Mukono)

“Before, I was so disrespected at home because even when he asked me what I had to offer, I couldn’t even show a penny. But now those words cannot come out of him because he knows that I have personal money now. So, that alone brought my home at peace and now we can sit and agree on certain issues, and he calmed down the disrespect he had towards me. That helped me even in society in that whenever they see me, there’s respect because I changed so much and they ask themselves whether I stole the money from someone, they think I went to the Statehouse, but I don’t even know where it is, I just do my projects.” (Participant 2, FGD, Gomba)

Contribution of the Women-led Climate Change Solution Satellites on Individual and Household Income and Financial Stability

Table 5 shows the contribution of the climate change solution satellites to the economic empowerment of women in Uganda. More than half 57.3% (55/96) of the women mentioned that participating in the satellite activities significantly increased their income, 56.3% (54/96) saw some improvement in their household income and 76% (73/96) had acquired some personal or household assets using income from the enterprise. Electronics (42.7%), furniture (24%), and rented/bought land (21.9%) were the most mentioned assets that were acquired by the women. Over 76% (73/96) of the women plan to acquire assets in the future using income from the satellite enterprises.

Table 5: Contribution of the women-led climate change solution satellites on individual and household income and financial stability in Uganda.

|

Variable

|

Category |

Frequency (n=96) |

Percentage

(%)

|

| The participation in the climate change solution satellite affected individual income |

Increased significantly |

55

|

57.3 |

|

Increased moderately

|

36 |

37.5

|

| Remained unchanged |

5

|

5.2 |

|

The enterprise had a noticeable impact on household income and financial stability

|

Considerable improvement

|

42 |

43.7

|

| Some improvement |

54

|

56.3 |

|

Acquired personal or household assets with income from the climate change solution satellite

|

Yes

|

73 |

76.0

|

| No |

23

|

24.0 |

|

If yes, which assets were acquired so far

|

Rented/bought land

|

21 |

21.9

|

| Constructed a house, roofed/repaired a house |

19

|

19.8 |

|

Car, truck, bicycle, motorcycle

|

3 |

3.1

|

| Furniture |

23

|

24.0 |

|

Electronics

|

41 |

42.7

|

| Others |

30

|

31.3 |

|

Plan to acquire any other assets in the coming 3 months

|

Yes

|

73 |

76.0

|

| No |

23

|

24.0 |

|

If yes, which assets

|

Electronics

|

13 |

13.5

|

| Furniture |

19

|

19.8 |

|

Land

|

31 |

32.3

|

| Construct house |

17

|

17.7 |

|

Car, truck, motorcycle

|

7 |

7.3

|

| Others |

27

|

28.1

|

Qualitatively, participants highlighted tangible improvements in their standards of living, evident through enhanced household conditions and increased financial stability. Engaging in skill-building activities such as liquid soap making and briquette production became collective family endeavors, involving both children and spouses, resulting in augmented household income. The acquired skills not only boosted individual businesses but also elevated their marketability, as exemplified by one participant’s improved catering services and the plan to acquire business transportation assets. Participants expressed a newfound self-control toward expenditure, demonstrating a shift from impulsive spending habits to thoughtful financial management. They acknowledged the significance of savings, with aspirations to invest in property or business expansions, showcasing a long-term commitment to financial growth and sustainability. These narratives collectively illustrate the tangible impact of climate change solution projects on individual and household incomes, fostering financial prudence.

“I see an improvement in the standards of living amongst all the women, especially those of us who manage our money well. Even our homes have improved in standard too.” (Participant 3, FGD, Butambala)

“Yes, it has helped us with the children, in that they have learnt some of these skills like liquid soap making, because they actively participate while we make it at home. We make briquettes and they also participate, as well as the husbands too, so more money comes in for all of us.” (Participant 4, FGD, Mukono)

“As a catering person, I saved money from these projects and invested in my business and this made me exemplary and marketable because my services were improved. I bought tents and chairs which made me a very presentable service provider and my services were highly demanded. I desire to purchase a vehicle that can transport my business assets in the future and in God’s name I know that I will purchase it.” (Participant 1, FGD, Gomba)

“Back then as ladies we never used to mind how much we had versus what we spent. Hawkers used to come around our communities and we would buy from almost all of them, but that has changed now. You must assess whether you need that item being hawked and ask yourself how much you made in the past month, and what improvements you need to make in your business, before purchasing say a bed cover from a hawker. Ever since we were trained, ladies have now learnt the importance of money, they appreciate saving and they know their responsibilities. It’s hard to find a lady who doesn’t save now.” (Participant 7, FGD, Butambala)

“Personally, I save the money I get from my business and in my saving group, we split profits annually so, I’ll be getting my share on 12th December and I want to use those savings to purchase an acre of land because I want to rear my cow on the same land as I live. So, I am hopeful that in the coming year, I will achieve it.” (Participant 6, FGD, Gomba)

Meaningful Participation of the Women in Livelihood/Economic Decision-making

About 65% (62/96) of the women had joined a women’s group, Savings and Credit Cooperative Organization (SACCO), or local governing body since their training with WCCI and 46.8% (29/62) had a leadership position in that body. Of those with leadership positions, 37.9% (11/29) were at the level of chairperson/vice chairperson while the rest were at secretary, treasurer, mobilizer or councilor level. Additionally, 79.3% (23/29) of the women in leadership rated high, the impact of the WCCI training on their decision to join leadership. Desire for personal growth and development (79.3%), Recognition of my abilities and potential (69%), and Desire to create a positive change (55.2%) were the most mentioned reasons for taking up leadership positions. Furthermore, 47.9% (46/96) jointly made economic/livelihoods decisions with their husbands, 81.2% (78/96) had recently been involved in livelihood/economic decisions while 82.3% mentioned that there was a positive difference in the way their husbands treat them ever since they started making their own money and being empowered. Less than a quarter 22.9% (22/96) acknowledged that their husbands do not support their work with the enterprise (Table 6).

Table 6: Meaningful participation of the Women in livelihood/economic decision-making opportunities at community and household level in Uganda.

|

Variable

|

Category |

Frequency

(n=96) |

Percentage

(%)

|

| Joined a women group, SACCO or local governing body since the training with WCCI |

Yes |

62

|

64.6 |

|

No

|

34 |

35.4

|

| Hold a leadership position on that women group, SACCO or local governing body |

Yes |

29

|

46.8 |

|

No

|

33 |

53.2

|

| Leadership position held on the women group or local leadership body or committee |

Chairperson/vice chairperson |

11

|

37.9 |

| Secretary/treasurer/mobilizer/councilor |

18 |

62.1

|

| Rate the impact of the training on your decision to join leadership and ability to serve in that capacity |

High impact |

23

|

79.3 |

|

Moderate impact

|

6 |

20.7

|

| Reasons for deciding to take up this leadership position |

Desire for personal growth and development |

23

|

79.3 |

|

Passion for climate change cause

|

14 |

48.3

|

| Recognition of my abilities and potential |

20

|

69.0 |

|

Desire to create positive change

|

16 |

55.2

|

| Need for representation and gender equality |

6

|

20.7 |

|

Previous experience

|

1 |

3.5

|

| Previously engaged in any advocacy meetings supporting women economic empowerment in your community |

Yes |

51

|

53.1 |

|

No

|

45 |

46.9

|

| In your household, who primarily makes decisions regarding economic activities and livelihoods |

Husband/male household member(s) |

12

|

12.5 |

|

Jointly made by and female household members

|

46 |

47.9

|

| Respondent/female household members |

35

|

36.5 |

|

Others

|

3 |

3.1

|

| Recently been involved in any livelihood/economic decision |

Yes |

78

|

81.2 |

|

No

|

18 |

18.8

|

| If yes, specify the type of livelihood/economic decision-making activities you have been part of. |

Income generation and business planning |

67

|

44.7 |

|

Investment decisions

|

43 |

28.7

|

| Market research |

4

|

2.7 |

|

Pricing and sales strategy

|

3 |

2.0

|

| Financial management and budgeting |

31

|

20.7 |

|

Others

|

2 |

1.3

|

| Make my own decisions regarding spending income |

Yes |

80

|

83.3 |

|

No

|

16 |

16.7

|

| Keep and spend my income by myself |

Yes |

81

|

84.4 |

|

No

|

15 |

15.6

|

| If no, who keeps or spends your income |

My husband |

13

|

86.7 |

|

Other person

|

2 |

13.3

|

| Okay with this, does this happen because of a mutual understanding between you and your partner |

Yes |

83

|

86.5 |

|

No

|

13 |

13.5

|

| Come for trainings and meetings with the knowledge of husband |

Yes |

81

|

84.4 |

|

No

|

15 |

15.6

|

| If No, does he stop you from coming for training/meetings? |

Yes |

81

|

84.4 |

|

No

|

15 |

15.6

|

| Noticed a difference in the way husband treats you since starting making own money and being empowered |

No difference |

17

|

17.7 |

|

Yes, positive difference

|

79 |

82.3

|

| Husband doesn’t support my work with the enterprise |

Agree |

22

|

22.9 |

|

Neutral

|

15 |

15.6

|

| Disagree |

17

|

17.7 |

|

Strongly disagree

|

42 |

43.8

|

In the realm of livelihood and economic decision-making, the narratives from FGD participants highlighted the impact of WCCI initiatives on women’s empowerment and assertiveness in various spheres. Participants mentioned a transformation in self-perception and assertiveness, indicating newfound confidence and self-esteem among participants. The program also cultivated the courage to engage actively in public forums, a stark contrast to previous shyness and avoidance of meetings. Furthermore, the narratives conveyed the evolution of participants into role models and trainers, and hence can be consulted on various aspects. Crucially, participants shared instances of enhanced agency in economic decision-making within their households. The shift from a scenario where men previously controlled household finances to a situation where women assertively communicate their plans while maintaining harmony in decision-making signifies a tangible shift in gender dynamics and increased agency for women in economic matters.

“WCCI has been helpful to some extent because it has created a working relationship with the government and they both know and respect each other. In my observation, WCCI has helped to make us strong women who believe in ourselves in that if you have decided to do something, you must believe it in your heart. We are on committees that are making decisions in our communities.” (Participant 3, FGD, Gomba)

“I have gained a lot of self-esteem, even when speaking in public I am more confident compared to before when I used to be shy and sometimes, I would even dodge the meetings but it’s not the case anymore and whenever I am phoned, I know that I have an important call to which I respond.” (Participant 2, FGD, Butambala)

“The other thing I’ve gained is that I have become an example for other ladies, and I am also a trainer to them of the skills I gained.” (Participant 5, FGD, Mukono)

“We used to have money back then, and the men would take it from us. But now, when he asks for it, I tell him that I have plans for my money and we still come to an agreement, without him thinking that I have refused to give him money, but I have other things to use it for.” (Participant 5, FGD, Gomba)

Overall Quality of Life and Well-being among the Women

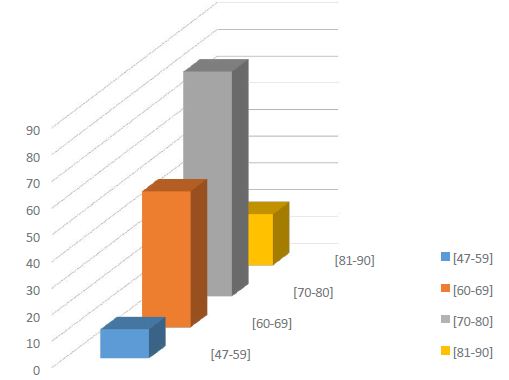

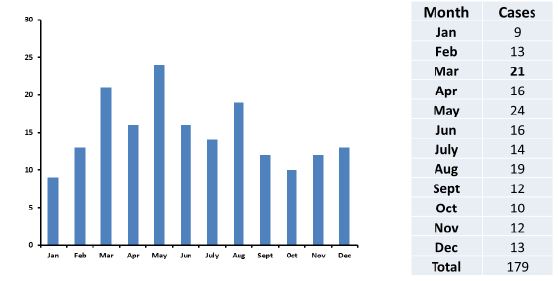

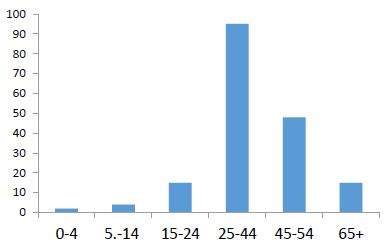

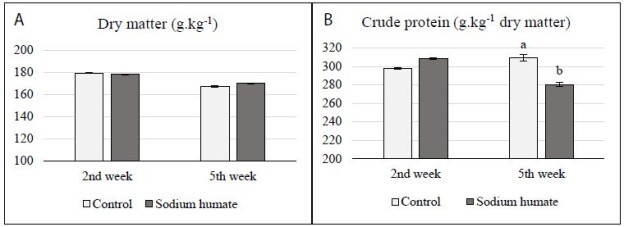

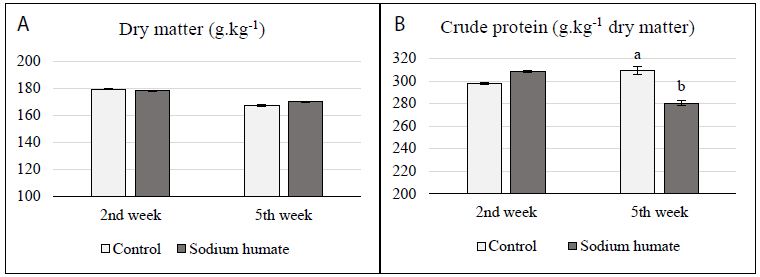

When asked if their overall well-being and quality of life have improved since becoming part of the climate-smart enterprise, the majority of the women, 63.6% (61/96) strongly agreed, 29.2% (28/96) agreed and 5.2% (5/96) were neutral. None of the women disagreed (Figure 1).

Figure 1: Perception on quality of life and overall wellbeing among the women

Through the diverse discussions, participants conveyed transformative personal and communal changes spurred by engagement in WCCI projects. These initiatives not only empowered women economically but also fostered improved family dynamics and social recognition. Participants highlighted a shift in household dynamics, with husbands now supportive and involved, and even prompting participation in the projects. Moreover, individual transformations were evident, reflected in enhanced self-esteem, improved appearance, and upgraded living standards. Participants celebrated tangible improvements in cleanliness, financial independence, diversified diets, and sustainable practices, demonstrating a profound shift in mindset towards environmental stewardship.

“… before, our husbands would get angry whenever we left home to come engage in such projects, but now they are steadily adjusting because we are very open about the dates when the projects will take place. So, the men have calmed down on realizing how much these projects have aided us. Even expenditures at home weighed down on men since we are now able to chip in on some of the home expenses. The husbands now even remind us of the dates when we are supposed to attend the projects. The improvement has been so evident in that even the children acknowledge that back then, they used to be chased from school due to lack of school fees, but now it’s no more.” (Participant 2, FGD, Gomba)

“I did not look like this before, the first thing I did with my money was to make sure I look good, and I am no longer looked down upon wherever I go. So, I see a big improvement from the ratchet I used to be to now looking better, it’s a very awesome change we should clap for ourselves.” Participant 6, FGD, Butambala

The other thing I had forgotten is that these trainings have improved cleanliness at home. A lady who is part of WCCI has a significantly decent home compared to those who are not in the project. We as ladies are very proud of these improvements. (Participant 1, FGD, Mukono)

“I used to just sit at home without much to do, but ever since WCCI came, it taught me so many things so right now I do my projects and have some personal money on me, and I have a job that I do, and doesn’t put me on pressure, I do it from my home without paying rent; customers come at my home without me having to hawk, schools too come and pick from my home. It has helped me a lot since I used to just sit at home back then. I am more satisfied with life now.” (Participant 5, FGD, Gomba)

“I used to eat cassava with tea and no sauce, but now life has changed. I can go and purchase beef, fish, and any sauce because the money is available. Even the dress code has changed.” (Participant 4, FGD, Buambala)

“I learned how to handle nature more than I used to before I could cut down trees but now, I look at trees like my own children and I cannot cut them down because it feels like I am cutting down my child like I’m ruining my child’s future.” (Participant 7, FGD, Mukono)

Discussion

The study aimed to assess the feasibility of Women-led climate change solution satellites on women’s social and economic empowerment and quality of life in the face of climate change in Uganda. The findings earlier shown are discussed per the objective below.

Collective Action in Women-led Climate Change Solution Satellites Influences Social Cohesion and Community Engagement

A noteworthy aspect of this project lies in its ‘train the trainer’ model, which has yielded substantial social impact while justifying the claim that empowering women through training can have far-reaching effects. Beyond individual skill acquisition, the project has employed a strategy where trained women become mentors, disseminating knowledge and skills within their communities. This ‘train the trainer’ approach has catalyzed a transformative shift among the women, not just as beneficiaries but as active agents of change within their communities.

The majority of participants reported significant improvements in their sense of belonging, increased community engagement, and notably better treatment from their families and neighbors. These outcomes are emblematic of a deeper societal transformation facilitated by these women-turned-trainers. By imparting their acquired knowledge and skills and actively engaging in communal projects, they have redefined their roles within their communities. Their involvement as both conveyors of expertise and active contributors to communal endeavors has elevated their status and influence, positioning them as key contributors to community progress.

Moreover, the collaborative nature of their work within the group-learning from each other, practicing in front of fellow satellite members-has fostered a supportive environment that nurtures confidence and competence. This newfound confidence not only improved their individual capacities but also equipped them to meaningfully contribute to larger communal initiatives. The ‘train the trainer’ model not only enhanced individual capabilities but also served as a catalyst for community development through knowledge dissemination and collaborative engagement.

Gender inequality, poverty, and other economic challenges are among the major causes of intimate and gender-based violence globally [16]. Given the high poverty levels of not only women but the general rural population in Uganda, it is understandable to unearth a 22% prevalence of intimate partner or gender-based violence among the respondents. The World Health Organization recommends seven strategies for prevention and reduction of violence against women, among which is the empowerment of women; Poverty reduction and creating an enabling environment [17], which were all targeted outcomes of this project. This evaluation indicated a 50% reduction in intimate partner and gender-based violence, with only 2 out of 11 individuals who had recent experiences attributing the violence to their engagement in entrepreneurship and the majority alluding to better treatment from their husbands. The trainings and empowerment given to women may have played a critical role in managing intimate and gender-based violence as has been deduced by earlier scholars [18,19].

The Economic Impact of Women-led Climate Change Solution Satellites on Individual and Household Income and Financial Stability

Significant proportions of the respondents mentioned an increase in their individual and household income, with some already purchasing property including gadgets, furniture, and land, using the newly found income. This result confirmed a partially achieved goal of the project; to positively impact women’s economic status and financial sustainability. The achievement can be explained by WCCI’s efforts in training the women on how to manage their finances including self-control towards expenditure, a saving culture and skilling in income-generating projects. WCCI engages the women in skill-building activities such as making soap, vaseline, and briquette among others that can be sold within the community to generate income and also supports them with the pre-requisite equipment for enhanced production. Skilling of women and trainings on financial literacy coupled with start-up support have been associated with economic empowerment in Uganda and other settings globally [20-22]. Through the “train the trainer model” which the women have wholesomely embraced and already practicing, this transformation can be transitioned to entire communities to contribute to the achievement of Sustainable Development Goal (SDG) 1; eradicating extreme poverty for all people everywhere by 2030 [23].

This evaluation also revealed the participation of women in decision-making ventures both in the community and in the households regarding livelihoods and economic development. Over 60% of the women joined women groups, SACCOs or local governing bodies and 47% of these were in leadership. These findings can be explained by the fact that WCCI emphasizes transformation in self-perception and assertiveness, which are key in interpersonal relationships and leadership [24,25] and can collaborate the newfound confidence and self-esteem among participants to join groups and even take up leadership positions. The program also cultivated the courage to engage actively in public forums, a stark contrast to previous shyness and avoidance of meetings, and women evolving into role models and trainers, who can be consulted on various aspects. The women are also gradually joining in decision-making at home, contributing ideas and funds for household development projects. The majority of the women mentioned keeping, planning for, and spending their money on things they find important unlike before when they used to spend randomly or simply give the money to their husbands to spend. This could be as a result of understanding the value of money, and the fact that these women have financial goals and have been taught to gradually grow their businesses and achieve more rather than being comfortable in their poverty.

The Overall Well-being and Quality of Life Improvements among Women Engaged in Climate Change Solution Satellites

Almost all the women in the study agreed that their overall well-being and quality of life has improved since becoming part of the climate-change solution satellites. The transformation can be attributed to the different gains from associating with WCCI. The nexus of economic empowerment heightened self-esteem, improved personal appearance, hygiene, financial autonomy, diverse dietary habits, enhanced family dynamics with increased support from husbands, improved treatment within families, and elevated social recognition collectively signify an elevated quality of life among the participants. According to the World Health Organization [26], the physical and psychological aspects of one’s life, their level of independence, social relationships, and the environment are key determinants of one’s quality of life and are the domains in the WHO quality of life assessment (WHOQOL) tool. These findings show that even though WCCI did not apply the standard 100-item WHO assessment tool, the women’s claim of improved quality of life and overall well-being is to a greater extent in accordance with the standard measurements as spelled out in the WHO’s quality of life user manual [26]. The findings therefore imply that WCCI’s model of women’s transformation through the climate change solution satellites is achieving their intended results, however, more standard assessments could be needed to further ascertain these findings.

Strengths and Limitations

The study encompassed a relatively large sample size (96 women), providing a diverse pool of participants engaged in different entrepreneurial activities related to climate change solutions. The study also collected data across various thematic areas, including social, economic, and personal aspects, offering a holistic view of the impacts of women’s engagement in entrepreneurship. The combination of quantitative and qualitative insights provides a comprehensive understanding of the women’s experiences and the findings indicated tangible outcomes such as increased income, asset acquisition, and improved social cohesion, highlighting the practical implications. On the other hand, there could be biases in self-reporting, especially regarding sensitive issues like experiences of violence or attributing them to entrepreneurship, which might lead to underreporting or misinterpretation. To address this, the women were made aware of the importance of giving accurate information and that their responses would be anonymous. The data collection process was also conducted by people who are not part of the trainers to try and make the participants comfortable to air out their issues. In addition, whereas the study highlights positive outcomes associated with entrepreneurship and WCCI training and support, establishing a direct causal link between participation and outcomes might be challenging due to external factors not accounted for in the study. The study however tried to focus on specific attributes provided to the participants through WCCI trainings and eliminated possible external factors.

Conclusions

Overall, participation in these entrepreneurial initiatives has brought about tangible improvements in social cohesion, economic empowerment, and the perceived quality of life and well-being for a significant majority of women involved, demonstrating the positive impact of the WCCI climate change solution satellites on their lives and communities. Through the train the train-the-trainer approach that has been embraced by the women and community, the program ought to be scaled up to enable more women to benefit, contributing to SDG 1.

Declarations

Data and Materials Availability

The data used in this study is available upon reasonable request from the corresponding author.

Ethics Approval and Consent to Participate

Informed consent was obtained from all participants for both the structured surveys and FGDs conducted, after ensuring that they understood the purpose of the research, their rights, and the confidentiality of their responses. The research was also approved by the Uganda Christian University Research and Ethics Committee-approval number UCUREC-2023-55. Measures were also taken to protect the anonymity and confidentiality of participants’ identities and responses.

Authors’ Contributions

All authors conceptualized the study. CHM, AT and GB participated in data collection, and drafted the first manuscript, CHM, GB, AT, RA, RWN, EM, and SD reviewed the first manuscript draft. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Funding

Support for this research was made possible through funding support of the Forum for Women and Development (FOKUS) in partnership with the sisters of Joseph and Climate Justice Resilience. The information provided does not necessarily reflect the views of the funders.

Conflict of Interest

Authors Comfort Hajra Mukasa, Godliver Businge, Rosemary Atieno, Rose Wamalwa Nyarotso, Elaine McCarty, Sarah Diefendorf are employed by Women Climate Centers International. The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

References

- Women, Gender Equality and Climate Change. 2023 [cited 2023 28th May]; Available from: https://shorturl.at/flxFO

- Increasing women’s economic equality would reduce poverty for everyone. 2023 [cited 2023 6th June]; Available from: https://www.oxfam.org/en/why-majority-worlds-poor-are-women.

- Akinbami CAO, et al. (2019) Exploring potential climate-related entrepreneurship opportunities and challenges for rural Nigerian women. Journal of Global Entrepreneurship Research 9: 19.

- Cardella GM, BR Hernández-Sánchez, JC Sánchez-García (2020) Women entrepreneurship: A systematic review to outline the boundaries of scientific literature. Frontiers in Psychology 11: 1557. [crossref]

- Njuguna Nu, TA Théophile (2023) KEYS TO CLIMATE ACTION.

- Climate change exacerbates violence against women and girls. 2023 [cited 2023 7th June]; Available from: https://shorturl.at/oqwJY

- Tol RS (2018) The economic impacts of climate change. Review of Environmental Economics and Policy.

- Hernández Martínez A (2023) Climate change on rural women in East Africa: analysis of consequences and recommendations from a gendered approach.

- Nchanji EB, et al. (2022) Gender differences in climate-smart adaptation practices amongst bean-producing farmers in Malawi: The case of Linthipe Extension Planning Area. Frontiers in Sustainable Food Systems.

- WCCI-Uganda. WCCI-Uganda is responsible for community training and regional project management. 2023 [cited 2023 28/11]; Available from: https://www.climatecenters.org/wcci-uganda.

- Ministry of Local Government-The Parish Development Model. 2021 [cited 2023 28/11]; Available from: https://molg.go.ug/parish-development-model/.

- N A T I O N A L P L A N N I N G A U T H O R I T Y, THIRD NATIONAL DEVELOPMENT PLAN (NDPIII) 2020/21-2024/25. 2020, N A T I O N A L P L A N N I N G A U T H O R I T Y,: Kampala, Uganda.

- Gomba District Local Government. History. 2023 [cited 2023 27/11]; Available from: https://gomba.go.ug/district/history.

- Butambala District Local Government. History. 2023 [cited 2023 27/11]; Available from: https://butambala.go.ug/.

- Mukono District Local Government. History. 2023 [cited 2023 28/11]; Available from: https://mukono.go.ug/.

- Sanjel S (2013) Gender-based violence: a crucial challenge for public health. Kathmandu University medical journal 11: 179-184. [crossref]

- Violence against women. 2021 [cited 2023 22/Nov]; Available from: https://www.who.int/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/violence-against-women.

- Ellsberg M, et al. (2015) Prevention of violence against women and girls: what does the evidence say? The Lancet 385: 1555-1566.

- Kiani Z, et al. (2021) A systematic review: Empowerment interventions to reduce domestic violence? Aggression and violent behavior 58: 101585.

- Kiconco B (2023) The contribution of the presidential initiative for skilling a girl child on women’s economic empowerment in Kampala District, Uganda. 2023, Makerere University.

- Ghosh A (2023) Skilling Women in Non-Traditional Livelihoods: Pathways to Women’s Economic Empowerment-Policy Brief. Available at SSRN 4551736.

- Singh V (2018) Empowering Women through Skill Development: Interlinking Human, Financial and Social Capital. Productivity. 58.

- Sustainable Development Goals-No poverty. 2023 [cited 2023 11th/12]; Available from: https://www.un.org/sustainabledevelopment/poverty/.

- Ames D (2009) Pushing up to a point: Assertiveness and effectiveness in leadership and interpersonal dynamics. Research in organizational behavior 29: 111-133.

- April K, N Sikatali (2019) Personal and interpersonal assertiveness of female leaders in skilled technical roles. Effective Executive 22: 33-58.

- WHO, WHO quality of life user manual. 2012.