DOI: 10.31038/IDT.2021212

Abstract

The evidence for the cometary origin then rapid global spread of COVID-19 through 2020 is critically reviewed. We outline why it is an alternative plausible scientific explanation to the current bat/pangolin animal jump theories. In our view this explanation is consistent with all the available temporal unfolding scientific data (genomic, immunologic, epidemiologic, geophysical, astrophysical and astrobiological). Thus COVID-19 arrived as infective cryopreserved virions in cometary meteoritic dust clouds from space in a bolide strike in the stratosphere over China on October 11 2019. Prevailing high-level and low-level wind systems then globally distributed the infective viral dust clouds, striking different regions at different times. Given this possibility, a new space challenge for mankind is to develop near-Earth early warning biological surveillance (and mitigation) systems for incoming cosmic in-falls of micro-organisms and viruses from the cometary dust and meteorite streams that our planet routinely encounters as it orbits the Sun.

Since it first emerged in Wuhan, China in late November into December 2019 the coronavirus pandemic due to COVID-19 (SARS-CoV-2) has been engulfing the world with considerable economic and health impact targeting mainly our elderly co-morbid citizens with clear deficits mainly in type I and type III interferon inducible anti-viral immunity [1-5].

How credible then is our conclusion, embodied in our title, that the COVID-19 pandemic could have arrived from space? The journal has invited us to outline this evidence for an extra-terrestrial origin, which we began publishing from early 2020 [6-10] and then in a mid-year review which appeared in November 2020 [11]. Our initial focus has been to explain the key events of the first months of the pandemic so as to understand its origin and rapid global spread. We marshalled not only the geophysical and temporal global epidemiological evidence [6-8,12], the prior knowledge from astrophysical and astrobiological evidence [13-16] but also gained insight into the genetic adaptation strategy of the virus, based on APOBEC and ADAR deaminase driven responses in infected subjects. These host innate immune responses designed to mutate and thus cripple the viral RNA genome actually helps steer viral haplotype diversification for optimal replicative efficacy. We view this as a ribo-switching host-parasite selection process for the fittest transmissible RNA haplotypic genome in a subject host [12,17].

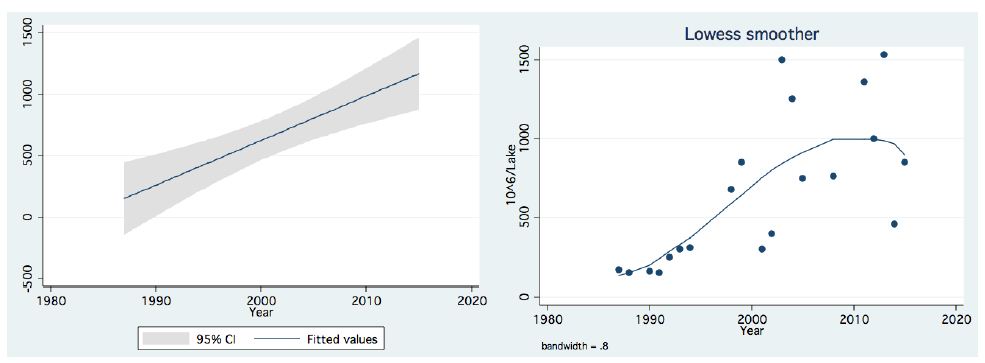

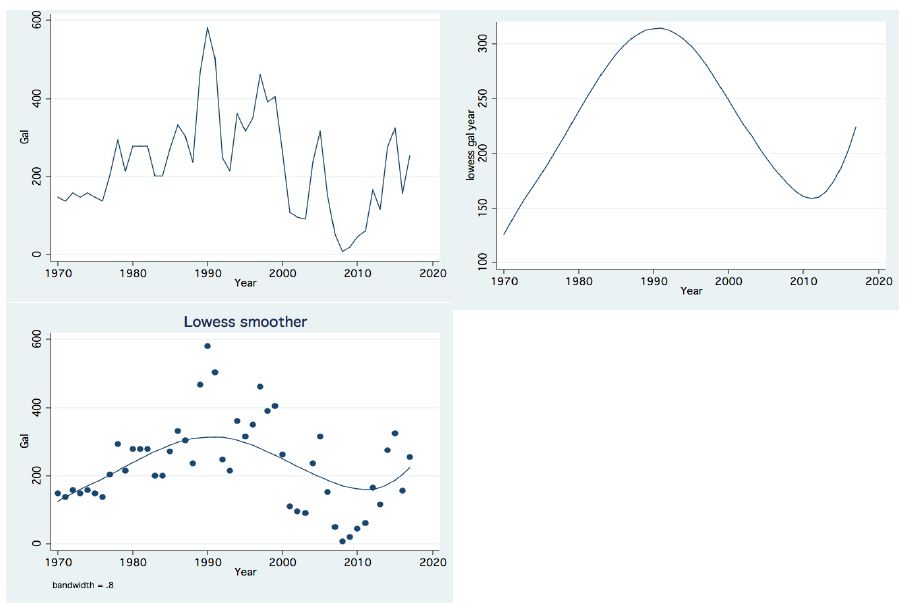

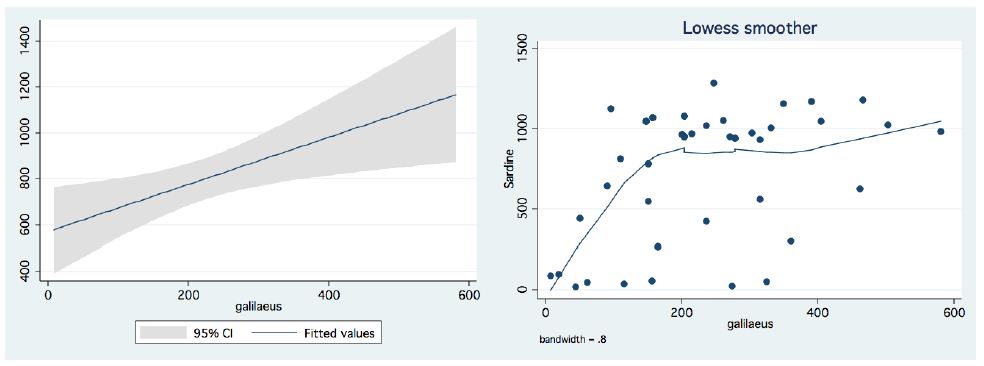

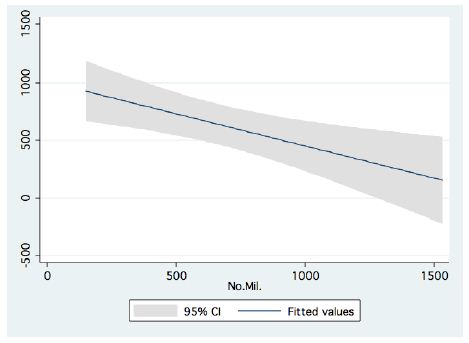

Our short narrative summary of one possible scenario not considered as mainstream thinking goes like this: A life-bearing loosely held carbonaceous cometary bolide arrived in the stratosphere over Jilin in North East China on the night of Oct 11 2019. This well-documented and widely observed event is recorded at the Space.com website. The viral-laden cometary dust particles and clumps (typically micron size) were released prior to the fireball in a fragmentation process, and they began their expected slow descent from the stratosphere in the 40° N Latitude band (30-50°). Over the next month some of this cometary-meteorite dust cloud was brought down to ground by local weather precipitation (rain) targeting the central Chinese city of Wuhan in Hubei province. This event, within another month, ignited by mass simultaneous infective exposure caused the explosive rise of COVID-19 cases through January in Wuhan and its wider contaminated regions. About 30% of all such infections were demonstrably not connected to any food or wet market [18,19]. However much of the upper troposphere/stratosphere viral laden dust remained there in the East to West (E-W) jet streams and was distributed around the globe at great speed (jet-streams circle the globe in ~ 3 days at speeds 150-200 km/hr). We speculate that explosive outbreaks on the ground of human person-to-person (P-to-P) passaged COVID-19 viruses could have created a secondary rising plume of viral-laden pollution and dust [20,21] over Wuhan and Hubei province containing trillions of dust-associated COVID-19 virions. We think that this plume was then carried by the lower level West to East (W-E) prevailing wind systems across the Pacific (Max Wallis, pers comm) engaging cruise ships through February in the South China Sea and Sea of Japan (Diamond Princess, Westerdam). This mode of transfer, including early first wave in-falls in South Korea and Japan and, by mid-February, to the US West Coast [7], could explain the virus outbreak on the Grand Princess cruise ship sailing out of San Francisco. This scenario for the Grand Princess outbreak has supportive genetic evidence as the main COVID-19 haplotype in infected passengers was identical to the unmutated (and lightly mutated) L haplotype that dominated the Wuhan outbreak [12,22]. The deposits in the higher E-W jet streams could have been brought down by capricious local weather conditions during early-mid March 2020 in Tehran/Qom, Lombardy/Italy and Spain, and then on the 40° N Latitude band to engage New York City as our earlier analysis had predicted [7,8].

The explosive outbreaks at widely dispersed global sites are consistent with this scenario. Further, they happened at great speed, with exponential growth rates of case numbers per day, that defied initial expectations of P-to-P spreading with the expected 1-2 week infection incubation periods. Aerial infective in-fall by viral laden dust over large population centres seems the most logical explanation for the simultaneous infections with little evidence of delay due to incubation time. The same explosive apparent simultaneous large-scale outbreaks occurred in clearly documented cases of deck crew members on ships at sea [17,23] and in the remote Chilean Bernardo O’Higgins Army Station in Antarctica in late December 2020 [24]. In a similar vein, the island of Sri Lanka flat lined in case numbers for many months with hardly any cases, and became suddenly engaged in a mass outbreak of over a 1000 COVID-19 cases in the period Oct 4-6 [10] and see also Sri Lanka at the Google URL search link below [25].

By March into April part of the E-W 40° N jet stream transporting the dust clouds was diverted into South America, particularly Brazil by prevailing Atlantic ocean wind systems [9]. From there on the prevailing wind systems of the Southern Hemisphere became engaged as the principal carriers of the infalling viral laden dust clouds. The high profile infective outbreaks were those in June through September occurring predominantly in South Africa and Victoria Australia, which coincidently are on the same prevailing W-E 40° S Latitude band (the French Polynesian Islands became engaged several months later from September). The latter interpretation for Victoria, Australia, is at odds with the prevailing local belief that the 2nd Wave outbreak was caused by hotel quarantine “escapees into the community”. This claim infers that infected travellers to Melbourne in March-April from Northern Hemisphere zones inadvertently spread the virus into the community where after several months these “escapee” variants then ignited the 2nd Wave in late June 2020. However, our evaluation of the publicly available Victorian case incidence data and the publicly available COVID-19 genomic sequence data leads to a qualified and quite different explanation which is also consistent with the viral laden dust cloud in-fall interpretation.

Interested readers can perform their own survey of the global COVID-19 cases per day patterns since early 2020 to the present at the Google URL site listed below to verify our claims [25]. It is evident that the disease has now spread all over the globe to all major continents and regions. At the time of writing (April-May 2021) a major in-fall has occurred over India and regions which we speculate is a down draft off the 40° N latitude band on the southern side of the Himalayan Mountains. But it is an exceedingly patchy pattern worldwide as discussed extensively in Hoyle and Wickramasinghe [13] again recently in Wickramasinghe et al [10] and as is evident in the Figures and Supplementary data to be found in Steele and Lindley [12] and Steele et al. [11,17]. Thus epidemics begin and end at different times in different regions and reach different intensities. In our view this behaviour reflects globally dispersed fragmented viral laden dust clouds brought haphazardly and capriciously to ground by local meteorological conditions. Certain regions may not experience a real in-fall event, and this is borne out in islands like Taiwan despite its closeness to China. The vagaries of local weather, prevailing winds, and chance in-fall of viral-laden dust clouds combine to present a capricious pattern of attack.

So in the ongoing pandemic, outbreaks around the globe have their own sudden beginnings and endings, yet major regions on the N 40° Latitude band (North America, Europe Asia Minor and the Indian subcontinent) have experienced several “Waves” already, or by the scenario considered here, separate “wash down” events from the troposphere. An interesting feature across all regions where a clear single mode of in-fall can be discerned is an unmistakable symmetrical bell-shaped curve, such as happened for the 2nd Wave in Victoria Australia, 1st Wave in South Africa, and the 1st Wave in Pakistan. There are many instances of this type if one cares to Google survey the case incident patterns per day across the globe [25]. Despite the height of the peak or intensity of the epidemic in individual instances, it is remarkable that the base of the symmetrical curve stretches typically over 2-3 months. The simplest interpretation is that this reflects the decay time of the virions in the physical environment, which remains remarkably the same across the globe.

With respect to the symmetrical nature of the bell-shaped curves describing the distributions of cases per day seen in such well documented epidemics such as the Victorian 2nd Wave an important deduction can be drawn about the impact of extreme ‘lockdown’ social distancing measures aimed at reducing viral reproduction rate Ro to less than 1. We have statistically analysed the Gaussian features of the Victorian 2nd Wave (which peaked on August 1-2, 2020). The best Gaussian fit with R2 gives 0.8999 which implies an almost perfect statistical fit to a symmetrical bell-shaped curve. Such a result would be consistent with the epidemic curve being overwhelmingly dominated by the growth and decay of a localised atmospheric in-fall event. The hard Stage 4 lockdown in Victoria came into effect on August 2, 2020. Given this perfect symmetry we conclude that the hard lock down measures had little impact, if any, on the course of the 2nd Wave COVID-19 epidemic in Victoria, Australia. This conclusion is consistent with the independent analyses of the impact of extreme lockdown measures on the course of the COVID-19 lockdowns introduced in a number of States in the USA during 2020 [26].

The patterns we have discussed apply generally to the manner in which suddenly emergent pandemics run their course throughout history [13]. It seems plausible to us that many might be a combination of wash down from the troposphere, leading to population wide exposures, eventually inducing herd immunity and a natural decay of the virions in the environment. However, we admit that there are many unknowns and that there are alternative explanations for these effects. Yet, on some specific details presented to us, the scenario presented here is a possible new reality that will need much future research.

Thus, from our viewpoint, the bulk of the key global evidence is consistent with an extra-terrestrial origin of COVID-19. Are there alternative explanations for the sudden origin and rapid global spread of the pandemic? We have dealt with this issue at some length [17], and there is one possible yet highly unlikely scientific explanation, and a bio weapon conspiracy theory explanation. Both are discussed in detail in Steele et al [17], but it is the zoonotic theory that can be dealt with rationally and scientifically, namely that COVID-19 arose in a jump from an animal reservoir, either in one or two steps or in combination, with SARS CoV related variants growing in bats and/or pangolins. In reviewing all the known related bat and pangolin SARS-CoV-like sequences the closest possible precursors are 96.2 % similar to the COVID-19 Hu-1 reference sequence (29903 nt). To get an exact match, in the normal haplotype range for globally dispersed COVID-19 of 99.98% sequence similarity [12,17] this involves>1100 specific nucleotide changes in the precursor to get such an exact COVID-19 match. These numbers imply super astronomical odds against a successful jump. Indeed, even if we are generous and assume only a 1% difference (which has not been seen in the wild) this gives odds of one successful mutational jump in 10180 trials, which also is a super astronomical number, far exceeding the molecular, and statistical, resources of the known universe. In our view a zoonotic explanation for the origin of COVID-19, although a valid scientific concept, is implausible on the current evidence [17].

This leaves us then with an alternative plausible scientific explanation that is consistent with the available data: the arrival of COVID-19 as infective cryopreserved virions in cometary meteoritic dust clouds from space. Given this possibility, a new space challenge for mankind is to develop near-Earth early warning biological surveillance (and mitigation) systems for incoming cosmic in-falls of micro-organisms and viruses from the cometary dust and meteorite streams that our planet routinely encounters as it orbits the Sun.

Acknowledgement

We acknowledge for discussion and contributions in development of ideas in this and earlier articles, Stephen G Coulson, Max K Wallis, Brig Klyce, Predrag Slijepcevic, Alexander Kondakov, Dayal T Wickramasinghe, George Howard, Herbert Rebhan, Pat Carnegie, Ananda Nimalasuriya and Milton Wainwright

References

- Acharya D, Liu G-Q, Gack MU (2020) Dysregulation of type I interferon responses in COVID-19. Nat Rev Immunol 20: 397- [crossref]

- Blanco-Melo D, Nilsson-Payant BE, Liu WC, Uhl S, Hoagland D, et al. (2020) Imbalanced Host Response to SARS-CoV-2 Drives Development of COVID-19. Cell 181: 1036-1045. [crossref]

- Hadjadj J, Yatim N, Barnabei L, Corneau A, Boussier J, et al. (2020) Impaired type I interferon activity and exacerbated inflammatory responses in severe Covid-19 patients. Science 369: 718-724. [crossref]

- Netea MG, Giamarellos-Bourboulis EJ, Domı ́nguez-Andre ́s J, Curtis N, van Crevel R, et al. (2020) Trained Immunity: a tool for reducing susceptibility to and the severity of SARS-CoV-2 infection Cell 181: 969- 977. [crossref]

- Lucas C, Wong P, Klein J, Castro TBR, Silva J, et al. (2020) Longitudinal analyses reveal immunological misfiring in severe COVID-19. Nature. 584: 463-469.

- Wickramasinghe NC, Steele EJ, Gorczynski RM, Temple R, Tokoro G, et al. (2020) Comments on the Origin and Spread of the 2019 Coronavirus. Virology: Current Research 4:1.

- Wickramasinghe NC, Steele EJ, Gorczynski RM, Temple R, Tokoro G, et al. (2020) Growing Evidence against Global Infection-Driven by Person-to-Person Transfer of COVID-19. Virology: Current Research 4:1.

- Wickramasinghe NC, Steele EJ, Gorczynski RM, Temple R, Tokoro G, et al. (2020) Predicting the Future Trajectory of COVID-19. Virology: Current Research 4:1.

- Wickramasinghe NC, Wallis MK, Coulson SG, Kondakov A, Steele EJ, et al. Intercontinental Spread of COVID-19 on Global Wind Systems. Virology: Current Research 4:1.

- Wickramasinghe NC, Steele EJ, Nimalasuriya A, Gorczynki RM, Tokoro G, et al. (2020) Seasonality of Respiratory Viruses Including SARS-CoV-2. Virology: Current Research 4:2.

- Steele EJ, Gorczynski RM, Lindley RA, Tokoro G, Temple R, et al. (2020) Origin of new emergent Coronavirus and Candida fungal diseases- Terrestrial or Cosmic? Advances in Genetics 106: 75-100. [crossref]

- Steele EJ, Lindley RA (2020) Analysis of APOBEC and ADAR deaminase-driven Riboswitch Haplotypes in COVID-19 RNA strain variants and the implications for vaccine design. Research Reports Vol 4.

- Hoyle F, Wickramasinghe NC (1979) Diseases from Space. JM Dent Ltd, London.

- Hoyle F, Wickramasinghe NC (2000) Astronomical Origins of Life: Steps Towards Panspermia. Klower Academic Publishers, Dordrechl, Netherlands.

- Steele EJ, Al-Mufti S, Augustyn KA, Chandrajith R, Coghlan JP, et al. (2018) Cause of Cambrian Explosion: Terrestrial or Cosmic? Prog Biophys Mol Biol 136: 3-23. [crossref]

- Steele EJ, Gorczynski RM, Lindley RA, Liu Y, Temple R, (2019) et al. Lamarck and Panspermia – On the Efficient Spread of Living Systems Throughout the Cosmos. Prog Biophys Mol Biol 149: 10 -32.

- Steele EJ, Gorczynski RM, Rebhan H, Carnegie P, Temple R, et al. (2020) Implications of haplotype switching for the origin and global spread of COVID-19. Virology: Current Research 4: 2. Supplementary data at: https://www.hilarispublisher.com/open-access/implications-of-haplotype-switching-for-the-origin-and-global-spread-of-covid19.pdf

- Huang C, Wang Y, Li X, Zhao J, Ren L, et al. (2020) Clinical Features of Patients Infected with 2019 Novel Coronavirus in Wuhan. Lancet 395: 497-506.

- Cohen J (2020) Wuhan seafood market may not be source of novel virus spreading globally. Science Vol 367.

- Coccia M (2020) Factors determining the diffusion of COVID-19 and suggested strategy to prevent future accelerated viral infectivity similar to COVID. Science of the Total Environment 729: 138474. [crossref]

- Martelletti L, Martelletti P (2020) Air Pollution and the Novel Covid-19 Disease: a Putative Disease Risk Factor. SN Compr Clin Med 2: 383-387.

- Andersen K (2020) Clock and TMRCA based on 27 genomes. Novel 2019 coronavirus. http://virological.org/t/clock-and- tmrca-based-on-27-genomes/347

- Howard GA, Wickramasinghe NC, Rebhan H, Steele EJ, Reginald M, et al. (2020) Mid-Ocean Outbreaks of COVID-19 with Tell-Tale Signs of Aerial Incidence Virology: Current Research 4: 2.

- Antartica Base: The remote Chilean Army Base in Antartica suddenly became engaged in late December 2020 by multiple simultaneous COVID-19 cases https://www.bbc.com/news/world-latin-america-55410065; https://www.abc.net.au/news/2020-12-23/more-covid-cases-linked-to-chilean-antarctic-base/13009706

- Google: “Coronavirus disease statistics” URL is https://bit.ly/3vxbD5i This gives you the “Australia” dashboard (from there you can choose your country in the menu bar scroll)

- Luskin DL (2020) The failed experiment of COVID-19 lockdowns. The Wall Street Journal.