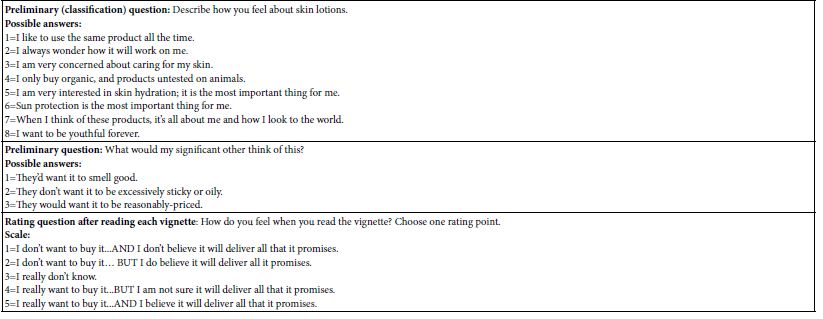

Abstract

Rheumatoid arthritis (RA), a chronic autoimmune disorder characterized by synovial inflammation and joint destruction, necessitates novel therapeutic strategies due to limitations in current treatments. This study investigates the molecular mechanisms of Portulaca oleracea L. (POL), a traditional medicinal herb with anti-inflammatory and antioxidant properties, in RA management using network pharmacology and molecular docking. Ten bioactive POL components, including quercetin, luteolin, and kaempferol, were identified via the Traditional Chinese Medicine Systems Pharmacology (TCMSP) database, targeting 208 potential human proteins. RA-associated genes (2,142 targets) were curated from GeneCards, OMIM, and TTD, with 134 overlapping targets identified as POL-RA interaction hubs. Protein-protein interaction (PPI) analysis revealed TNF, AKT1, and IL6 as core targets, while Gene Ontology (GO) enrichment highlighted inflammatory response, apoptotic regulation, and cytokine activity. Kyoto Encyclopedia of Genes and Genomes (KEGG) pathway analysis implicated POL in modulating RA-related signaling cascades, including PI3K-Akt, TNF, and IL-17. Molecular docking confirmed strong binding affinities of quercetin (−7.85 kcal/mol with TNF), luteolin (−7.62 kcal/mol with IL6), and kaempferol (−7.52 kcal/mol with TNF), validating their interactions with key targets. These results demonstrate POL’s polypharmacological effects through multi-component, multi-target, and multi-pathway mechanisms, offering a scientific foundation for its development as a complementary RA therapy. This study bridges traditional medicine and systems biology, providing insights into POL’s therapeutic potential and guiding future drug discovery efforts.

Keywords

Portulaca oleracea L, Rheumatoid arthritis, Network pharmacology, Molecular docking

Introduction

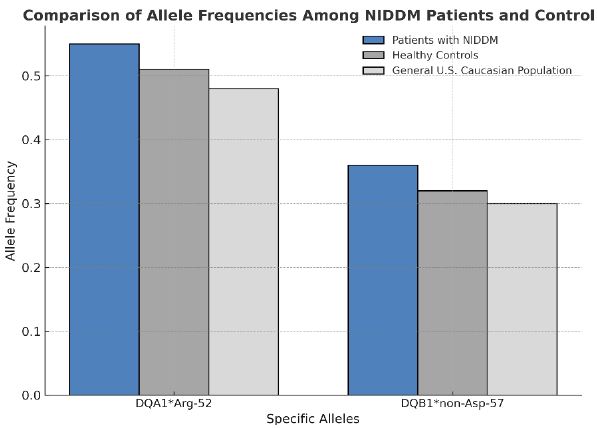

Rheumatoid arthritis (RA) is a chronic, systemic autoimmune disease characterized by persistent synovial inflammation, cartilage destruction, and bone erosion, leading to progressive joint damage and systemic complications [1]. Early-stage clinical manifestations of RA typically include joint stiffness, particularly in the morning, swelling, and pain, which are often symmetrical and affect small joints such as those in the hands and feet. As the disease advances, these symptoms may progress to joint deformities, functional impairment, and even permanent disability, significantly impacting patients’ daily lives and overall well-being [2]. With a global prevalence of approximately 0.5–1%, RA is one of the most common autoimmune disorders, disproportionately affecting women and older adults. The disease not only contributes to significant morbidity but also leads to a reduced quality of life and increased healthcare costs due to the need for long-term management and treatment [3]. The pathogenesis of RA is highly complex and involves a multifaceted interplay of genetic predisposition, environmental triggers, and dysregulated immune responses [4]. Genetic factors, such as specific human leukocyte antigen (HLA) alleles, play a critical role in increasing susceptibility to the disease. Environmental triggers, including smoking, infections, and hormonal changes, may further contribute to the onset and progression of RA. These factors collectively lead to the breakdown of immune tolerance, resulting in the activation of autoreactive T and B cells [5]. Once activated, these immune cells initiate a cascade of inflammatory processes, driving the production of pro-inflammatory cytokines such as tumor necrosis factor-alpha (TNF-α), interleukin-6 (IL-6), and interleukin-17 (IL-17). These cytokines perpetuate synovial inflammation, promote the formation of pannus tissue, and contribute to the destruction of cartilage and bone, ultimately leading to joint damage and systemic complications [6]. While multiple hypotheses exist regarding pathogenesis of Rheumatoid arthritis, the exact mechanisms remain unclear [7].

Traditional treatment regimens include the use of disease-modifying antirheumatic drugs (DMARDs), nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs and steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs [8]. Methotrexate (MTX), a cornerstone of antirheumatic drugs, acts as a folate antagonist with anti-proliferative, anti-metabolic, and anti-inflammatory properties. It modulates immune cell infiltration and reduces pro-inflammatory cytokine levels [9]. However, long-term MTX can produce toxicity and side effects such as bone marrow suppression, pulmonary toxicity, nephrotoxicity and an increased risk of infections [10]. NSAIDs, which inhibit cyclooxygenase to suppress prostaglandin synthesis, provide analgesic, antipyretic, and anti-inflammatory benefits. Despite their efficacy, they pose risks of gastrointestinal ulcer complications (bleeding, perforation), renal dysfunction, cardiovascular events, and mortality [11]. Steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs, though effective as anti-inflammatory adjuncts by supplementing cortisol levels, are clinically controversial due to adverse effects including infections, hypertension, cardiovascular disease, metabolic disorders (diabetes, obesity), osteoporosis, and ocular complications (cataracts, glaucoma) [12]. The treatment landscape for RA has evolved dramatically over the past decade, with the introduction of biologic DMARDs (bDMARDs) and targeted synthetic DMARDs (tsDMARDs) revolutionizing disease management [13]. TNF-α inhibitors, such as etanercept and adalimumab, were among the first bDMARDs to demonstrate efficacy in reducing inflammation and halting radiographic progression [14]. Subsequent developments include IL-6 inhibitors (e.g., tocilizumab), B-cell depleting agents (e.g., rituximab), and Janus kinase (JAK) inhibitors (e.g., tofacitinib and baricitinib), which offer alternative mechanisms of action for patients with inadequate responses to conventional therapies [15,16]. Despite these advancements, a significant proportion of patients experience suboptimal responses or adverse effects, highlighting the need for novel therapeutic targets and personalized treatment approaches [17]. In addition to pharmacological interventions, non-pharmacological approaches, such as physical therapy, exercise, and dietary modifications, play a complementary role in RA management. Regular physical activity has been shown to improve joint function, reduce pain, and enhance quality of life in RA patients [18].

Dietary interventions, including the Mediterranean diet and omega-3 fatty acid supplementation, may exert anti-inflammatory effects and modulate disease activity [19]. However, further research is needed to establish standardized guidelines for integrating these modalities into routine clinical practice. Given the limitations and toxicity profiles of existing therapies, there remains an urgent unmet need for safer, more effective pharmacological interventions to improve RA management and patient outcomes. Studies have shown that traditional Chinese herbs may have significant potential in the treatment of rheumatoid arthritis in recent years [20]. Portulaca oleracea L (POL) belonging to the Portulaceae family and the Portulaca genus is an annual fleshy herbaceous plant., Portulaca has a sour taste and a cold nature. It is reported that this herb was used as a kind of food and medicine for thousands of years in China [21]. As a medicinal and edible plant, it has the effects of clearing heat and detoxifying, cooling blood and stopping bleeding, and stopping dysentery; Meanwhile, purslane has multiple functions such as anti-inflammatory, immune regulation, antioxidant, and hypoglycemic effects. It has been used to treat diabetes, headache, gastrointestinal infection and other diseases [22,23]. Studies have shown that purslane extract can alleviate yeast polysaccharide induced joint inflammation in mice by inhibiting Nrf2 expression [24]. Ehsan Karimi et al. conducted a double-blind, randomized controlled clinical trial The findings demonstrated that purslane supplementation significantly alleviated clinical symptoms, including reductions in joint swelling, tenderness frequency, and morning stiffness duration. At the molecular level, purslane administration led to a marked increase in total antioxidant capacity (TAC) and superoxide dismutase (SOD) activity. indicating a potential anti-inflammatory and antioxidant effect of purslane in RA patients [25]. However, the precise mechanism and related signaling pathways of POL reatment for rheumatoid arthritis has not been elucidated. Network pharmacology is a research field based on systems biology, genomics, proteomics and other disciplines, which is a method to discover new drug targets and molecular mechanisms by combining computational analysis with in vivo and in vitro experiments and integrating a large amount of information [26]. It focuses on studying multiple components, multiple targets, and multiple signaling pathways, providing new ideas for the research of traditional Chinese medicine [27]. Within TCM monographs, network pharmacology serves to explore relationships between active components and TCM targets, elucidating mechanisms of action and potential effects [28]. This study investigates the molecular mechanisms underlying Portulaca oleracea L. (POL) in treating rheumatoid arthritis (RA) through integrated network pharmacology and molecular docking, offering novel therapeutic insights and a scientific foundation for further pharmacological exploration.

Materials and Methods

Databases and Software

This study employed the following databases and computational tools: Traditional Chinese Medicine Systems Pharmacology (TCMSP) (http://tcmspw.com/tcmsp.php) was used to identify bioactive compounds in Portulaca oleracea L. (POL) based on pharmacokinetic parameters. GeneCards (http://www.genecards.org), OMIM (https://omim.org), and Therapeutic Target Database (TTD) (https://db.idrblab.org/ttd) were queried to collect rheumatoid arthritis (RA)-related targets. UniProt (https://www.uniprot.org) standardized gene names and species-specific identifiers. Venny 2.1.0 (http://bioinfogp.cnb.csic.es/tools/venny) generated Venn diagrams to identify overlapping targets. STRING (https://string-db.org) constructed protein-protein interaction (PPI) networks with a confidence score cutoff ≥ 0.4. DAVID (https://david.ncifcrf.gov) performed Gene Ontology (GO) and Kyoto Encyclopedia of Genes and Genomes (KEGG) enrichment analyses. Cytoscape visualized and analyzed networks, while PyMOL rendered molecular structures. AutoDock 4.2.6 executed molecular docking simulations. PubChem (https://pubchem.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov) and Protein Data Bank (PDB) (https://www.rcsb.org) provided 3D structures of ligands and receptors, respectively. Weishengxin (http://www.bioinformatics.com.cn) visualized enrichment results.

Network Pharmacology Analysis

Prediction of Active Ingredients and Targets in POL

Active ingredients in POL were retrieved from TCMSP using stringent pharmacokinetic filters: oral bioavailability (OB) ≥ 30% and drug-likeness (DL) ≥ 0.18, thresholds established for predicting compounds with therapeutic potential [1]. Corresponding targets were extracted from TCMSP and cross-validated via UniProt to ensure human gene symbol consistency (taxonomic ID: 9606). Non-human or uncharacterized targets were excluded.

Acquisition of RA Disease Targets

RA-associated targets were systematically collected from GeneCards, OMIM, and TTD using “rheumatoid arthritis” as the search term. GeneCards targets were filtered by a relevance score median ≥ 2.41, a statistically validated cutoff to prioritize high-confidence targets [2]. Duplicate entries across databases were removed to compile a non-redundant RA target dataset.

Intersection Target Screening

POL and RA targets were intersected using Venny 2.1.0 to identify shared therapeutic targets. A compound-target network was constructed in Cytoscape, where nodes represented compounds or targets, and edges denoted interactions. Topological parameters (degree, betweenness centrality) were calculated to rank core bioactive components.

Protein–Protein Interaction (PPI) Network Construction and Analysis

Shared targets were uploaded to STRING (organism: Homo sapiens) to build a PPI network with default parameters (confidence score ≥0.4, hidden disconnected nodes). The network was imported into Cytoscape and analyzed using the Network Analyzer plugin. Key targets were prioritized using a composite score integrating degree centrality, betweenness centrality, and closeness centrality, with the top 20 nodes retained for downstream analysis.

Functional and Pathway Enrichment

DAVID was utilized for GO and KEGG analyses with the following settings: species = Homo sapiens, adjusted p-value <0.05, and enrichment score ≥1.5. GO terms were categorized into biological processes (BP), cellular components (CC), and molecular functions (MF). KEGG pathways were filtered for RA relevance (e.g., inflammation, immune regulation). Enriched terms were visualized as bubble charts using Weishengxin. A drug-target-pathway network was constructed to map POL’s multi-scale therapeutic mechanisms.

Molecular Docking Validation

The molecular docking protocol involved three sequential phases: ligand and receptor preparation, docking simulations, and methodological validation. Canonical SMILES of core POL components (e.g., kaempferol, quercetin) were retrieved from PubChem and converted to 3D structures (.mol2 format) using Chem3D, followed by energy minimization with the MMFF94 force field and Gasteiger charge assignment to generate ligand files in .pdbqt format. For receptor preparation, crystal structures of key targets (e.g., TNF-α: PDB ID 2AZ5; AKT1: PDB ID 3O96) were obtained from the Protein Data Bank (PDB), with PyMOL removing heteroatoms and water molecules, and AutoDockTools optimizing hydrogen placement and charge distribution. Docking simulations were performed using AutoDock Vina with a grid box dimension of 25 × 25 × 25 Å centered on the active site, an exhaustiveness parameter of 20 for conformational sampling, and generation of 10 ligand poses ranked by binding affinity (kcal/mol). The lowest-energy conformation was selected for structural visualization in PyMOL, where hydrogen bonding and hydrophobic interactions were annotated. To validate the protocol, co-crystallized ligands were redocked into their respective receptors, achieving a root mean square deviation (RMSD) of <2.0 Å, confirming the reliability of the docking methodology.

Results

Anti-Rheumatoid Arthritis Active Ingredients and Target Proteins of POL

Ten bioactive components in Portulaca oleracea L. (POL) with potential anti-rheumatoid arthritis (RA) activity were identified via the TCMSP database, including quercetin, luteolin, kaempferol, arachidonic acid, β-carotene, β-sitosterol, 5,7-dihydroxy-2-(3-hydroxy-4-methoxyphenyl)chroman-4-one, isobetanidin, isobetan in-qt, and cycloartenol. These compounds were selected based on pharmacokinetic criteria (oral bioavailability ≥30% and drug-likeness ≥0.18). A total of 208 potential POL-related targets were curated using UniProt, with gene symbols standardized to human orthologs.

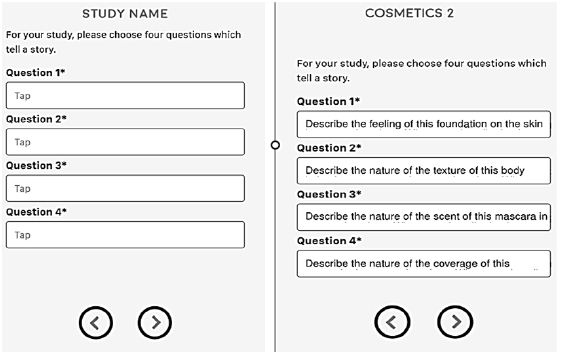

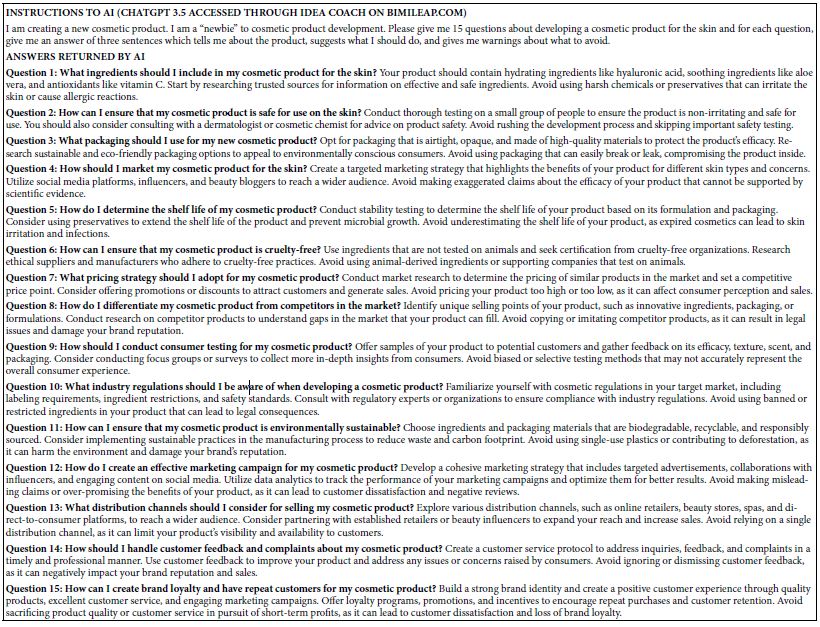

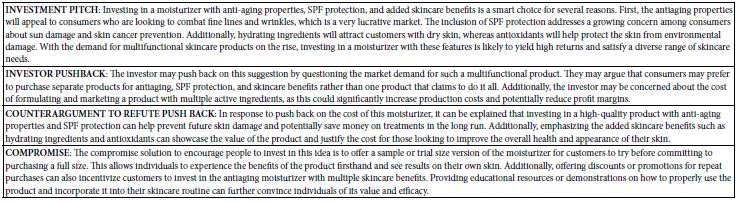

RA-associated targets were systematically retrieved from GeneCards (2,065 targets), OMIM (48 targets), and TTD (100 targets). After merging datasets and removing duplicates, 2,142 unique RA-related targets were retained. Intersection analysis using a Venn diagram revealed 134 shared targets between POL and RA (Figure 1A), suggesting their critical role in mediating POL’s therapeutic effects. The compound-target network (Figure 1B) highlights quercetin, luteolin, and kaempferol as core bioactive components with the highest connectivity.

Figure 1: (A) Venn diagram of potential targets for the anti- rheumatoid arthritis of POL; (B) compound–target network of POL for anti- rheumatoid arthritis. The middle red diamond node represents POL, the triangle nodes represent the Key POL Components, and the surrounding Rectangular nodes represent the targets that interact with POL.

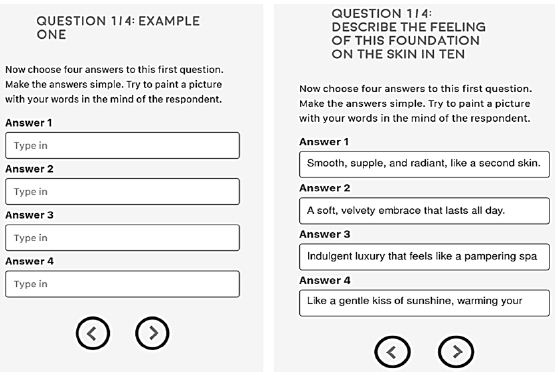

Screening of Key POL Components for RA Treatment

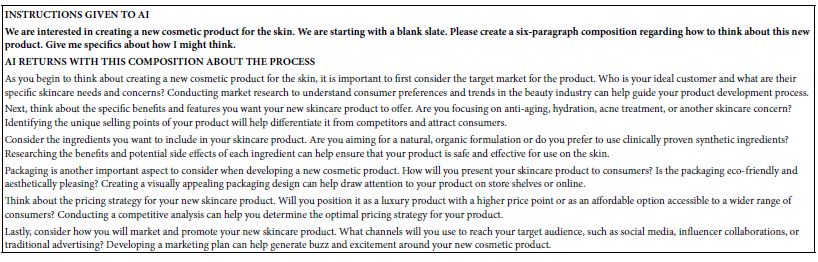

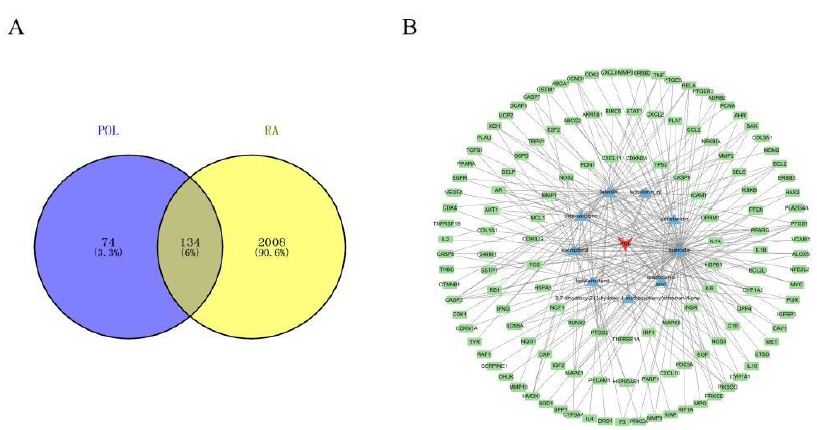

A compound-target interaction network (Figure 2) was constructed using Cytoscape 3.10.2 to identify critical bioactive components in Portulaca oleracea L. (POL) for rheumatoid arthritis (RA) therapy. Among 11 candidate bioactive components, quercetin, luteolin, and kaempferol exhibited the highest target connectivity (Table 1), suggesting their pivotal role in mediating POL’s therapeutic effects. Cycloartenol was excluded from network analysis due to the absence of associated targets. A multi-layered drug-component-target-disease network was subsequently generated to systematically explore POL’s molecular mechanisms, highlighting synergistic interactions between bioactive compounds and RA-related pathways.

Figure 2: Construction of the drug–target–disease network. The red diamonds symbolize POL and RA, the orange polygons depict the active components of POL, and the blue ellipses represent the core targets of RA.

Table 1: Thirteen components of CA with potential anti-angiogenic activity.

|

Molecule Name |

OB (%) | DL |

Degree |

| Quercetin |

46.43 |

0.28 |

103 |

| Luteolin |

36.16 |

0.25 |

45 |

| Kaempferol |

41.88 |

0.24 |

37 |

| Arachidonic acid |

45.57 |

0.2 |

25 |

| Beta-carotene |

37.18 |

0.58 |

19 |

| Beta-sitosterol |

36.91 |

0.75 |

19 |

| 5,7-Dihydroxy-2- (3-hydroxy-4-methoxyphenyl)chroman-4-one |

47.74 |

0.27 |

5 |

| Isobetanidin |

59.73 |

0.52 |

5 |

| Isobetanin_qt |

30.16 |

0.52 |

2 |

| Cycloartenol |

38.69 |

0.78 |

0 |

Identification of Core Bioactive Components in POL for RA Intervention

To delineate the therapeutic potential of Portulaca oleracea L. (POL) in rheumatoid arthritis (RA), a compound-target interaction network was constructed using Cytoscape 3.10.2. From 110 candidate bioactive components, quercetin, luteolin, and kaempferol demonstrated maximal target connectivity (degree centrality >15), underscoring their centrality in POL’s anti-RA efficacy. Cycloartenol was excluded due to the absence of validated targets in RA pathogenesis. Subsequently, a multi-scale network integrating drugs, components, targets, and disease pathways was generated, revealing synergistic crosstalk between POL-derived phytochemicals and RA-associated signaling cascades (e.g., TNF, IL-17). This systems-level analysis elucidates POL’s polypharmacological mode of action, driven by multi-target engagement.

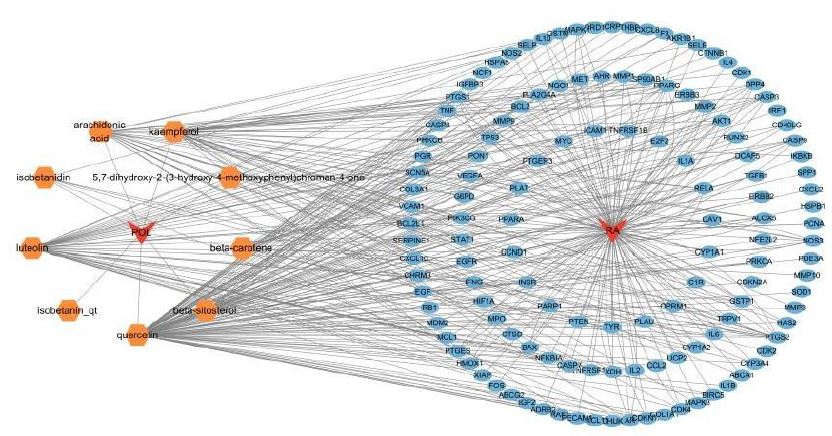

Protein-Protein Interaction (PPI) Network Construction

The 134 overlapping targets between Portulaca oleracea L. (POL) and rheumatoid arthritis (RA) were analyzed using the STRING database (confidence score ≥0.4, Homo sapiens), and the resultant PPI network was imported into Cytoscape for topological characterization. The network comprised 133 nodes and 3314 edges, with an average node degree of 56.2, reflecting robust interconnectivity (Figure 3). Node importance was quantified via centrality metrics: degree (number of edges), betweenness centrality (bridging role in network paths), and closeness centrality (proximity to other nodes) (Table 2. Visual attributes (node size and color intensity) were scaled proportionally to composite centrality scores. Hierarchical ranking identified TNF, AKT1, and IL6 as top-ranked hub targets, implicating their critical roles in mediating POL’s anti-RA effects through inflammatory and proliferative signaling modulation.

Figure 3: PPI network diagram of therapeutic targets for rheumatoid arthritis.

Table 2: Top 15 anti-rheumatoid arthritis target information in PPI network.

|

Number |

Target name | Degree | Betweenness centrality |

Closeness centrality |

|

1 |

AKT1 |

117 |

0.050 |

0.898 |

|

2 |

TNF |

117 |

0.041 |

0.898 |

|

3 |

IL6 |

116 |

0.039 |

0.892 |

|

4 |

IL1B |

108 |

0.026 |

0.846 |

|

5 |

MMP9 |

104 |

0.027 |

0.825 |

|

6 |

TP53 |

104 |

0.019 |

0.825 |

|

7 |

PTGS2 |

102 |

0.022 |

0.815 |

|

8 |

CASP3 |

100 |

0.016 |

0.805 |

|

9 |

HIF1A |

97 |

0.015 |

0.791 |

|

10 |

EGFR |

95 |

0.016 |

0.781 |

|

11 |

BCL2 |

95 |

0.016 |

0.781 |

|

12 |

TGFB1 |

94 |

0.014 |

0.776 |

|

13 |

PPARG |

90 |

0.013 |

0.759 |

|

14 |

IFNG |

87 |

0.013 |

0.746 |

|

15 |

MYC |

87 |

0.012 |

0.746 |

Gene Ontology (GO) and Kyoto Encyclopedia of Genes and Genomes (KEGG) Pathway Enrichment Analyses

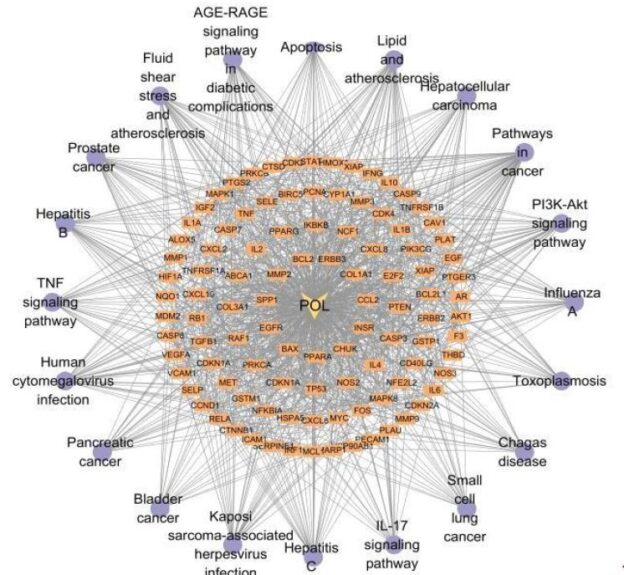

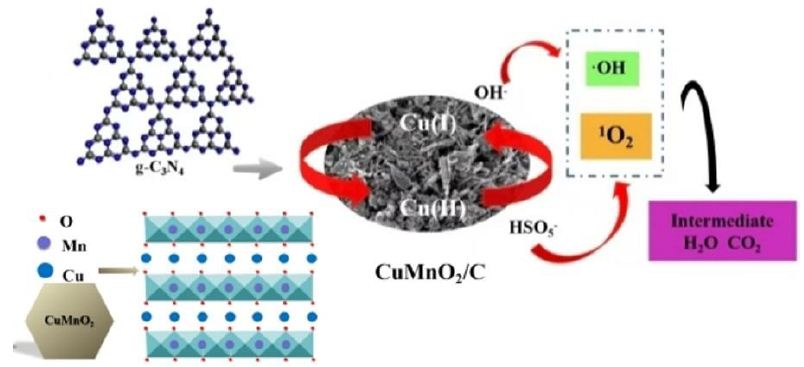

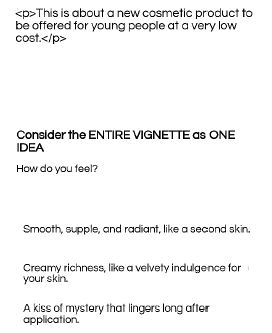

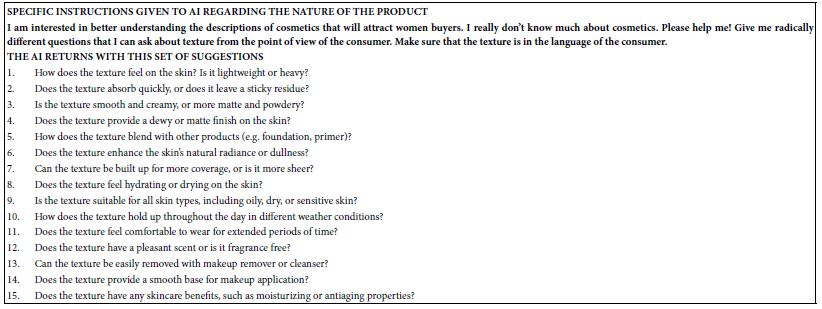

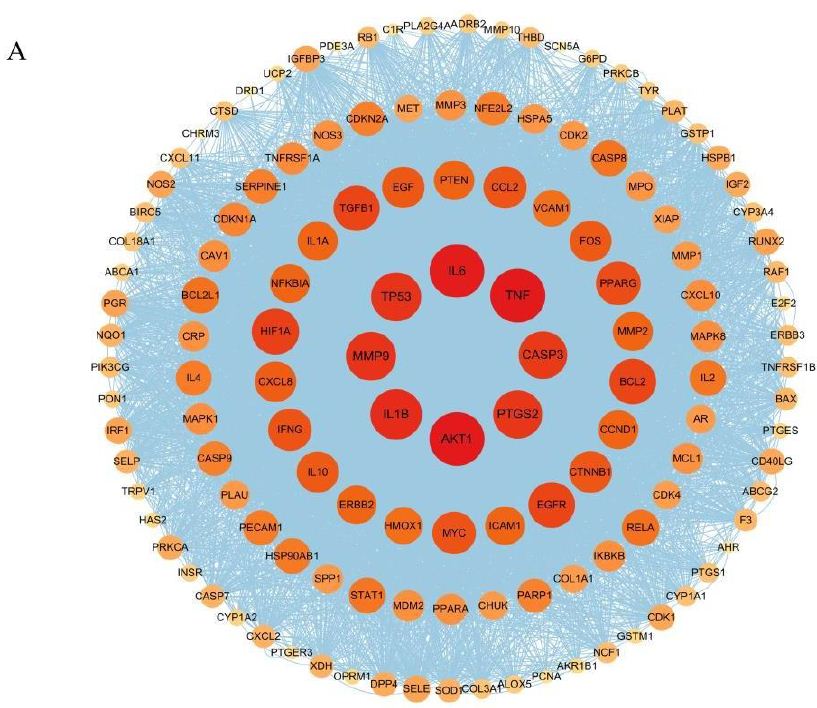

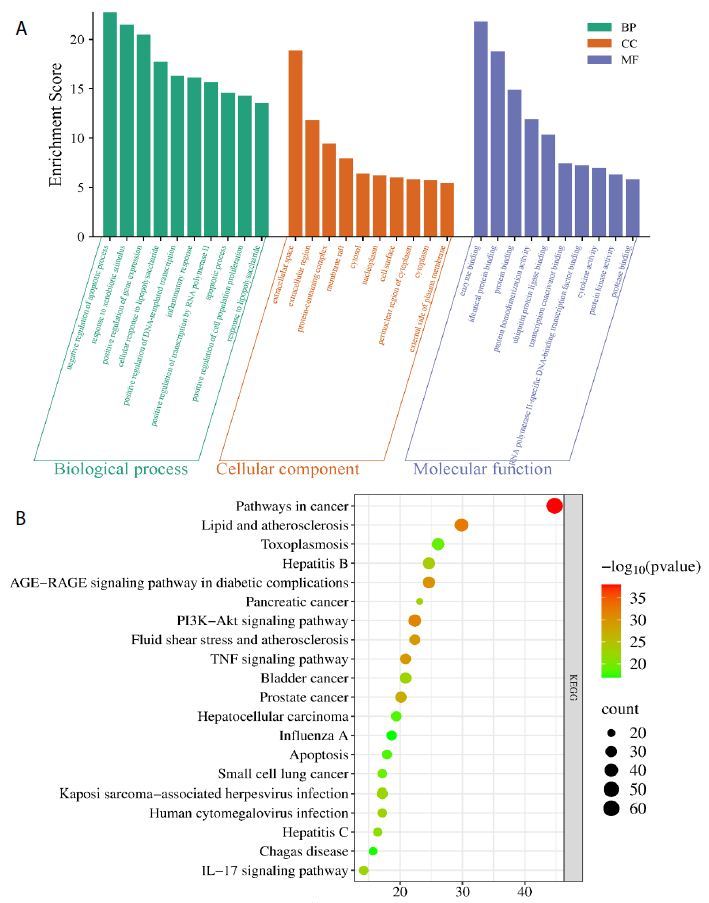

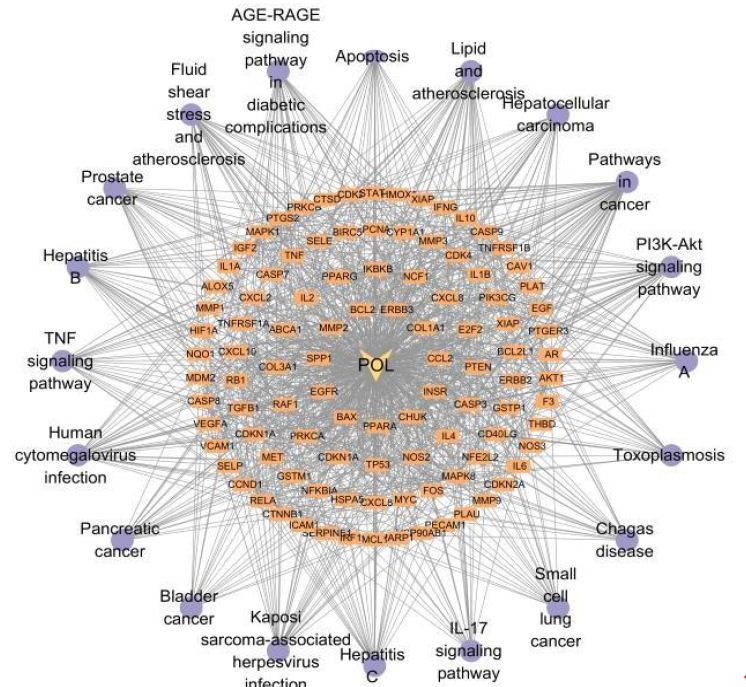

Functional enrichment analysis of Portulaca oleracea L. (POL) targets was performed using DAVID software. Statistical filtering (p < 0.001) identified 223 significant biological processes, 54 cellular components (p < 0.05), 110 molecular functions (p < 0.05), and 126 KEGG pathways (p < 0.001). The enriched GO terms and KEGG pathways were systematically analyzed to infer the potential biological functions of POL targets in rheumatoid arthritis (RA) pathogenesis. In the GO function analysis, the top 10 enriched GO terms across biological processes (BP), cellular components (CC), and molecular functions (MF) were identified based on adjusted p-values (Figure 4A). In BP, significant terms included negative regulation of apoptotic process (GO: 0043066), inflammatory response (GO: 0006954), response to xenobiotic stimulus (GO: 0009410), cellular response to lipopolysaccharide (GO: 0071222), and positive regulation of gene expression (GO: 0010628), highlighting POL’s roles in inflammation modulation, detoxification, and transcriptional regulation. CC enrichment predominantly localized to extracellular space (GO: 0005615), cytosol (GO: 0005829), membrane raft (GO: 0045121), and nucleoplasm (GO: 0005654), suggesting coordinated signaling across extracellular, cytoplasmic, and nuclear compartments. MF analysis revealed critical interactions involving enzyme binding (GO: 0019899), cytokine activity (GO: 0005125), protein kinase activity (GO: 0004672), and RNA polymerase II-specific transcription factor binding (GO: 0061629), underscoring POL’s engagement with enzymatic, signaling, and transcriptional machinery. These findings collectively implicate POL in multi-layered regulatory mechanisms relevant to RA pathology. The top 20 enriched KEGG pathways were identified and visualized as bubble maps (Figure 4B). A drug-target-pathway network integrating POL components, core targets (e.g., TNF, AKT1, IL6), and enriched pathways was constructed in Cytoscape 3.10.2(Figure 5). Key pathways included PI3K-Akt signaling (hsa04151), TNF signaling (hsa04668), IL-17 signaling (hsa04657), AGE-RAGE signaling in diabetic complications (hsa04933), and Fluid shear stress and atherosclerosis (hsa05418). Additional pathways such as Pathways in cancer (hsa05200), Hepatitis B (hsa05161), Apoptosis (hsa04210), and Influenza A (hsa05164) further implicated POL’s regulatory roles in inflammation, proliferation, and immune response. Annotation of pathway-target interactions revealed POL’s multi-target engagement across these cascades, with TNF, AKT1, and IL6 serving as central hubs. These results demonstrate POL’s polypharmacological properties, characterized by synergistic modulation of interconnected signaling networks relevant to rheumatoid arthritis (RA) pathogenesis and associated comorbidities.

Figure 4: Functional enrichment analyses of the target proteins of POL against RA. (A) Top 10 GO terms in the biological processes (p < 0.001), cellular components (p < 0.05), molecular functions (p < 0.05). (B) Top 20 KEGG pathways (p < 0.001). The depth of the circle color represents “- log10 pvalue”, and the size of the circle represents the number of genes enriched in this signaling pathway.

Figure 5: A drug-target-pathway network integrating POL, target and signaling pathways. The diamond represents POL, the rectangle represents the target of POL action, and the purple circle represents the top 20 signaling pathways.

Molecular Docking Validation

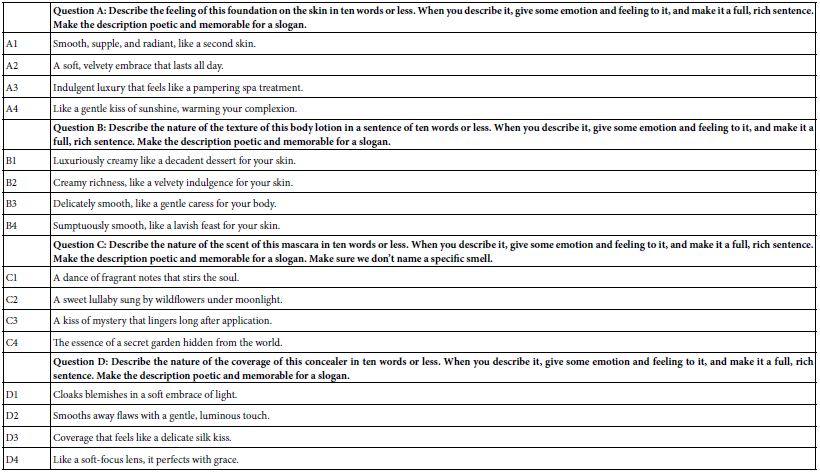

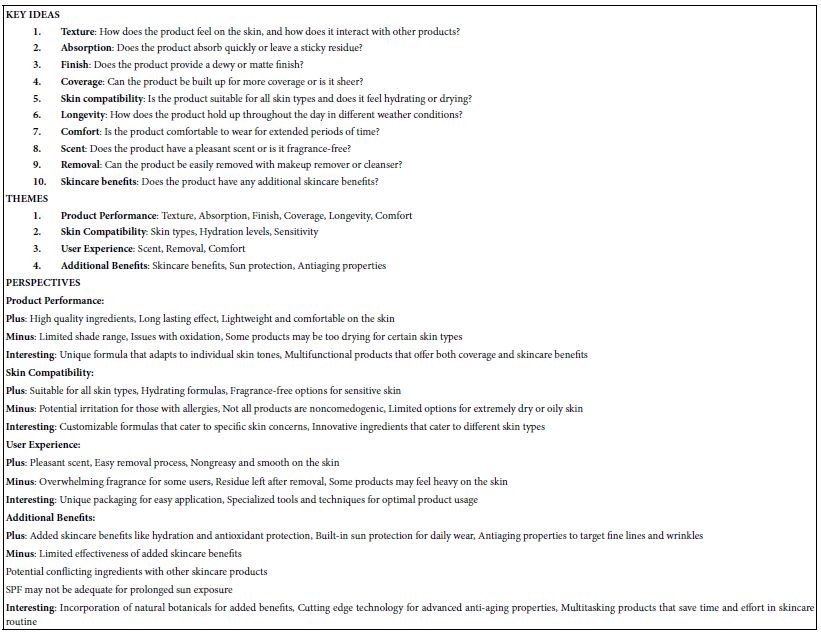

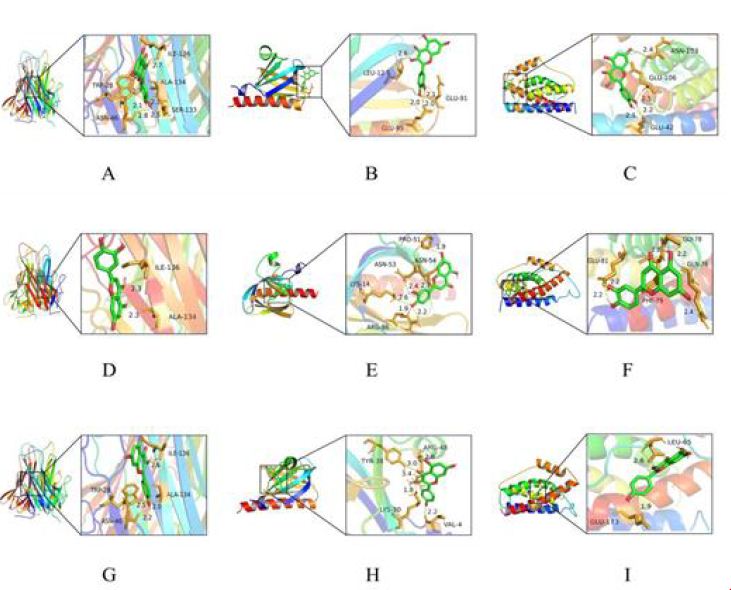

To validate the binding interactions between Portulaca oleracea L. (POL) components and rheumatoid arthritis (RA)-associated targets, molecular docking simulations were performed using AutoDock software. The binding affinities (kcal/mol) of quercetin, luteolin, and kaempferol with core targets (TNF, IL6, AKT1) are summarized in Table 3. Quercetin exhibited the strongest binding affinity to TNF (−7.85 kcal/mol), followed by IL6 (−7.06 kcal/mol) and AKT1 (−6.76 kcal/mol). Luteolin demonstrated optimal binding to IL6 (−7.62 kcal/mol), with affinities of −6.73 kcal/mol (TNF) and −7.31 kcal/mol (AKT1). Kaempferol showed preferential binding to TNF (−7.52 kcal/mol), alongside affinities of −6.15 kcal/mol (IL6) and −6.94 kcal/mol (AKT1). Lower binding energy values (more negative) correlate with stronger ligand-receptor interactions, as confirmed by structural visualization of hydrogen bonding and hydrophobic contacts (Figure 6A-I). These results validate POL’s multi-target engagement, with quercetin emerging as the most potent inhibitor of TNF-driven inflammatory signaling, a hallmark of RA pathogenesis.

Table 3: Binding energies of the molecular docking of POL with targets.

|

Quercetin |

Luteolin |

Kaempferol |

|

|

TNF |

-7.85 kcal/mol | -6.73 kcal/mol |

-7.52 kcal/mol |

|

AKT1 |

-6.76 kcal/mol | -7.31 kcal/mol |

-6.94 kcal/mol |

|

IL-6 |

-7.06 kcal/mol | 7.62 kcal/mol |

-6.15 kcal/mol |

Figure 6: Molecular docking pattern between pivotal compounds of POL and the core target protein. (A) Quercetin-TNF; (B) Quercetin- AKT1; (C) Quercetin- IL-6; (D) Luteolin- TNF; (E) Luteolin- AKT1; (F) Luteolin- IL-6; (G) Kaempferol- TNF; (H) Kaempferol- AKT1; (I) Kaempferol- IL-6.

Discussion

Portulaca oleracea L. (POL), a traditional herbal medicine with significant ethnopharmacological relevance, exhibits broad therapeutic potential in inflammation, immune regulation, antioxidant activity, and metabolic disorders [30]. While historical texts document its efficacy against diabetes, headaches, and gastrointestinal ailments [31], its molecular mechanisms in rheumatoid arthritis (RA) remain underexplored. Leveraging network pharmacology and molecular docking, this study deciphered POL’s multi-component, multi-target, and multi-pathway anti-RA properties, addressing the complexity inherent to traditional Chinese medicine. Ten bioactive components were identified through pharmacokinetic screening, with quercetin, luteolin, and kaempferol emerging as core constituents. Quercetin, a multifunctional flavonoid, exhibits both anti-inflammatory and anti-ferroptosis properties. Research indicates that quercetin significantly alleviates the pathological progression of osteoarthritis by inhibiting chondrocyte apoptosis and promoting the polarization of synovial macrophages toward the M2 phenotype [32]. Additionally, quercetin promotes bone health through antioxidant pathways and regulates metabolic balance, further highlighting its therapeutic potential in bone and joint diseases [33,34]. Luteolin, a potent immunomodulator, significantly mitigates neutrophil-driven oxidative stress by inhibiting superoxide anion generation, reducing reactive oxygen species (ROS) production, and blocking the formation of neutrophil extracellular traps (NETs) [35]. Moreover, studies have found that luteolin alleviates osteoblast pyroptosis by activating the PI3K-Akt signaling pathway, thereby promoting bone formation and inhibiting bone resorption, which has the remarkable efficacy in the treatment of postmenopausal osteoporosis [36]. Kaempferol plays a crucial role in the treatment of rheumatoid arthritis (RA) by inhibiting the activation of the MAPK signaling pathway. Research has shown that kaempferol blocks the activation of the MAPK pathway in fibroblast-like synoviocytes, thereby inhibiting synovial invasion and regulating bone metabolism [37]. Quercetin, luteolin, and kaempferol synergistically enhance bone repair and significantly suppress inflammatory cascades through multiple molecular mechanisms. These findings provide robust scientific evidence for the osteoprotective and anti-arthritic potential of POL.

Protein-protein interaction (PPI) network analysis has emerged as a powerful tool for identifying key molecular players in complex diseases such as rheumatoid arthritis (RA). Through this approach, TNF, AKT1, and IL6 have been prioritized as pivotal therapeutic targets due to their central roles in the pathogenesis of RA. TNF-α, a master regulator of RA pathogenesis, orchestrates a cascade of inflammatory and destructive processes within the joint microenvironment. It drives chronic inflammation by upregulating pro-inflammatory cytokines such as IL-1β and IL-6, which perpetuate synovial inflammation and contribute to systemic manifestations of the disease [38-40]. Furthermore, TNF-α promotes osteoclastogenesis, leading to bone resorption and joint destruction, while simultaneously inhibiting bone formation through the upregulation of Wnt antagonist DKK-1 [41]. This dual role in bone remodeling underscores its critical involvement in RA progression. IL-6, another key cytokine identified in the PPI network, plays a dual role in immune regulation. While it is essential for mediating acute immune responses, its dysregulation in RA exacerbates disease pathology. IL-6 activates the Jak/STAT-3 and Ras/Erk/C/EBP signaling pathways, which promote T-cell activation, synovial hyperplasia, and the production of additional inflammatory mediators [42-44]. Clinically, the efficacy of IL-6 receptor inhibitors such as tocilizumab and sarilumab has validated IL-6 as a therapeutic target, demonstrating significant reductions in disease activity and joint damage in RA patients [45]. AKT1, a central node in the PI3K/Akt signaling pathway, has also been identified as a critical therapeutic target through PPI network analysis. This kinase modulates a wide range of cellular processes, including inflammation, endothelial apoptosis, and neutrophil infiltration, all of which are implicated in RA pathogenesis [46-48].

KEGG pathway enrichment analysis revealed that POL (the active compound under investigation) is implicated in several rheumatoid arthritis (RA)-related signaling pathways, including the PI3K-Akt, TNF, and MAPK cascades, which are critical to the pathogenesis of RA. The PI3K/Akt signaling axis plays a pivotal role in regulating chondrocyte apoptosis and extracellular matrix (ECM) remodeling, processes central to joint degradation in RA [49,50]. Studies have demonstrated that pharmacological inhibition of the PI3K/Akt pathway attenuates osteoarthritis progression and subchondral bone sclerosis, highlighting its therapeutic potential in inflammatory joint diseases [51-54]. TNF-α, a key pro-inflammatory cytokine in RA, drives synovial inflammation and joint destruction. TNF-α blockade remains a cornerstone of RA therapy, as evidenced by the clinical success of biologics such as etanercept and infliximab. Molecular docking studies have revealed that quercetin, a bioactive component of POL, exhibits strong binding affinity to TNF-α, suggesting a mechanism by which POL may exert its anti-inflammatory effects [55,56]. Furthermore, the MAPK/ERK signaling pathway, which is modulated by POL components, plays a critical role in bone regeneration and inflammation resolution. Activation of MAPK/ERK signaling has been shown to promote osteoblast differentiation and bone formation, while its dysregulation contributes to inflammatory responses in RA [57,58]. MiR-133a can regulate the MAPK/ERK signaling pathway to rescue glucocorticoid induced bone loss [59,60]. These findings collectively position POL as a polypharmacological agent capable of simultaneously targeting multiple pathological pathways, including inflammation, apoptosis, and metabolic dysregulation, thereby offering a holistic and multi-targeted approach to RA management.

Conclusion

This study delineates POL’s anti-RA mechanisms through network pharmacology and molecular docking, emphasizing its multi-target synergy against TNF-α, IL-6, and PI3K/Akt pathways. While promising, further in vivo validation and clinical trials are warranted to translate these insights into therapeutic applications.

Notes

The authors declare no competing financial interest.

References

- Smolen JS, Aletaha D, McInnes IB (2016) Rheumatoid arthritis [published correction appears in Lancet.

- Smith MH, Berman JR (2022) What Is Rheumatoid Arthritis? JAMA 22. [crossref]

- Scott DL, Wolfe F, Huizinga TW (2010) Rheumatoid arthritis. Lancet 25.

- Venetsanopoulou AI, Alamanos Y, Voulgari PV, Drosos AA (2023) Epidemiology and Risk Factors for Rheumatoid Arthritis Development. Mediterr J Rheumatol 34: 404-413. [crossref]

- McInnes IB, Schett G (2011) The pathogenesis of rheumatoid arthritis. N Engl J Med 365: 2205-2219. [crossref]

- McInnes IB, Schett G (2017) Pathogenetic insights from the treatment of rheumatoid arthritis. Lancet 389: 2328-2337. [crossref]

- Firestein GS, McInnes IB (2017) Immunopathogenesis of Rheumatoid Arthritis. Immunity 46: 183-196. [crossref]

- Demoruelle MK, Deane KD (2012) Treatment strategies in early rheumatoid arthritis and prevention of rheumatoid arthritis. Curr Rheumatol Rep 14: 472-480. [crossref]

- Zhao Z, Hua Z, Luo X, Li Y, Yu L, et al. (2022) Application and pharmacological mechanism of methotrexate in rheumatoid arthritis. Biomed Pharmacother 150. [crossref]

- Hamed KM, Dighriri IM, Baomar AF, Alharthy BT, Alenazi FE, et al. (2022) Overview of Methotrexate Toxicity: A Comprehensive Literature Review. Cureus 23. [crossref]

- Panchal NK, Prince Sabina E (2023) Non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs): A current insight into its molecular mechanism eliciting organ toxicities. Food Chem Toxicol 172. [crossref]

- Cutolo M, Shoenfeld Y, Bogdanos DP, Gotelli E, Salvato M, et al. (2024) To treat or not to treat rheumatoid arthritis with glucocorticoids? A reheated debate. Autoimmun Rev 23. [crossref]

- Harrington R, Al Nokhatha SA, Conway R (2020) JAK Inhibitors in Rheumatoid Arthritis: An Evidence-Based Review on the Emerging Clinical Data. J Inflamm Res 13: 519-531. [crossref]

- Smolen JS, Landewé RBM, Bijlsma JWJ, Burmester GR, Dougados M, et al. (2020) EULAR recommendations for the management of rheumatoid arthritis with synthetic and biological disease-modifying antirheumatic drugs: 2019 update. Ann Rheum Dis 79: 685-699. [crossref]

- Radu AF, Bungau SG (2021) Management of Rheumatoid Arthritis: An Overview. Cells 10. [crossref]

- Armuzzi A, Lionetti P, Blandizzi C, Caporali R, Chimenti S, et al (2014) anti-TNF agents as therapeutic choice in immune-mediated inflammatory diseases: focus on adalimumab. Int J Immunopathol Pharmacol 27(1 Suppl): 11-32. [crossref]

- Tanaka Y (2021) Recent progress in treatments of rheumatoid arthritis: an overview of developments in biologics and small molecules, and remaining unmet needs. Rheumatology (Oxford). 60(Suppl 6). [crossref].

- Hurkmans E, van der Giesen FJ, Vliet Vlieland TP, Schoones J, Van den Ende EC (2009) Dynamic exercise programs (aerobic capacity and/or muscle strength training) in patients with rheumatoid arthritis. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. (crossref)

- Sköldstam L, Hagfors L, Johansson G (2003) An experimental study of a Mediterranean diet intervention for patients with rheumatoid arthritis. Ann Rheum Dis 62: 208-214. [crossref]

- Wang Y, Chen S, Du K, Liang C, Wang S, et al. (2021) Traditional herbal medicine: Therapeutic potential in rheumatoid arthritis. J Ethnopharmacol 279. [crossref]

- Ghorani V, Saadat S, Khazdair MR, Gholamnezhad Z, El-Seedi H, et al. (2023) Phytochemical Characteristics and Anti-Inflammatory, Immunoregulatory, and Antioxidant Effects of Portulaca oleracea L.: A Comprehensive Review. Evid Based Complement Alternat Med 2023. [crossref]

- Iranshahy M, Javadi B, Iranshahi M, Jahanbakhsh SP, Mahyari S, et al. (2017) A review of traditional uses, phytochemistry and pharmacology of Portulaca oleracea L. J Ethnopharmacol 205: 158-172. [crossref]

- Yang Y, Zhou X, Jia G, Li T, Li Y, et al. (2023) Network pharmacology based research into the effect and potential mechanism of Portulaca oleracea L. polysaccharide against ulcerative colitis. Comput Biol Med 161. [crossref]

- He Y, Long H, Zou C, Yang W, Jiang L, et al. (2021) Anti-nociceptive effect of Portulaca oleracea L. ethanol extracts attenuated zymosan-induced mouse joint inflammation via inhibition of Nrf2 expression. Innate Immun 27: 230-239. [crossref]

- Karimi E, Aryaeian N, Akhlaghi M, Abolghasemi J, Fallah S (2024) The effect of purslane supplementation on clinical outcomes, inflammatory and antioxidant markers in patients with rheumatoid arthritis: A parallel double-blinded randomized controlled clinical trial. Phytomedicine.

- Boezio B, Audouze K, Ducrot P, Taboureau O (2017) Network-based Approaches in Pharmacology. Mol Inform 36. [crossref]

- Nogales C, Mamdouh ZM, List M, Kiel C, Casas AI, et al. (2022) Network pharmacology: curing causal mechanisms instead of treating symptoms. Trends Pharmacol Sci 43: 136-150. [crossref]

- Li L, Yang L, Yang L, He C, He Y, et al. (2023) Network pharmacology: a bright guiding light on the way to explore the personalized precise medication of traditional Chinese medicine. Chin Med 18. [crossref]

- Meng XY, Zhang HX, Mezei M, Cui M (2011) Molecular docking: a powerful approach for structure-based drug discovery. Curr Comput Aided Drug Des 7: 146-57. [crossref]

- Kumar A, Sreedharan S, Kashyap AK, Singh P, Ramchiary N (2021) A review on bioactive phytochemicals and ethnopharmacological potential of purslane (Portulaca oleracea L). Heliyon 8. [crossref]

- Iranshahy M, Javadi B, Iranshahi M, Jahanbakhsh SP, Mahyari S, et al. (2017) A review of traditional uses, phytochemistry and pharmacology of Portulaca oleracea L. J Ethnopharmacol 205: 158-172. [crossref]

- Hu Y, Gui Z, Zhou Y, Xia L, Lin K, et al. (2019) Quercetin alleviates rat osteoarthritis by inhibiting inflammation and apoptosis of chondrocytes, modulating synovial macrophages polarization to M2 macrophages. Free Radic Biol Med 145: 146-160. [crossref]

- Feng Y, Dang X, Zheng P, Liu Y, Liu D, et al. (2024) Quercetin in Osteoporosis Treatment: A Comprehensive Review of Its Mechanisms and Therapeutic Potential. Curr Osteoporos Rep 22: 353-365. [crossref]

- Yamaura K, Nelson AL, Nishimura H, Rutledge JC, Ravuri SK, et al. (2023) Therapeutic potential of senolytic agent quercetin in osteoarthritis: A systematic review and meta-analysis of preclinical studies. Ageing Res Rev 90. [crossref]

- Yang SC, Chen PJ, Chang SH, Weng YT, Chang FR, et al. (2018) Luteolin attenuates neutrophilic oxidative stress and inflammatory arthritis by inhibiting Raf1 activity. Biochem Pharmacol 154: 384-396. [crossref]

- Chai S, Yang Y, Wei L, Cao Y, Ma J, et al. (2024) Luteolin rescues postmenopausal osteoporosis elicited by OVX through alleviating osteoblast pyroptosis via activating PI3K-AKT signaling. Phytomedicine 128. [crossref]

- Pan D, Li N, Liu Y, Xu Q, Liu Q, et al. (2018) Kaempferol inhibits the migration and invasion of rheumatoid arthritis fibroblast-like synoviocytes by blocking activation of the MAPK pathway. Int Immunopharmacol 55: 174-182. [crossref]

- Kalliolias GD, Ivashkiv LB (2016) TNF biology, pathogenic mechanisms and emerging therapeutic strategies. Nat Rev Rheumatol 12: 49-62. [crossref]

- Lee SJ, Lee A, Hwang SR, Park JS, Jang J, et al. (2014) TNF-α gene silencing using polymerized siRNA/thiolated glycol chitosan nanoparticles for rheumatoid arthritis. Mol Ther 22: 397-408. [crossref]

- Moelants E-A, Mortier A, Van Damme J, et al. (2013) Regulation of TNF-α with a focus on rheumatoid arthritis. Immunol Cell Biol 91: 393-401. [crossref]

- Cici D, Corrado A, Rotondo C, Cantatore FP (2019) Wnt Signaling and Biological Therapy in Rheumatoid Arthritis and Spondyloarthritis. Int J Mol Sci 20. [crossref]

- Tanaka T, Narazaki M, Kishimoto T (2014) IL-6 in inflammation, immunity, and disease. Cold Spring Harb Perspect Biol 4. [crossref]

- Neurath MF, Finotto S (2011) IL-6 signaling in autoimmunity, chronic inflammation and inflammation-associated cancer. Cytokine Growth Factor Rev 22: 83-89. [crossref]

- Huizinga TW, Fleischmann RM, Jasson M, Radin AR, van Adelsberg J, et al. (2014) Sarilumab, a fully human monoclonal antibody against IL-6Rα in patients with rheumatoid arthritis and an inadequate response to methotrexate: efficacy and safety results from the randomised SARIL-RA-MOBILITY Part A trial. Ann Rheum Dis 73: 1626-1634. [crossref]

- Scott LJ (2017) Tocilizumab: A Review in Rheumatoid Arthritis. Drugs 77: 1865-1879. [crossref]

- Cheng C, Zhang J, Li X, Xue F, Cao L, et al. (2023) NPRC deletion mitigated atherosclerosis by inhibiting oxidative stress, inflammation and apoptosis in ApoE knockout mice. Signal Transduct Target Ther 8. [crossref]

- Di Lorenzo A, Fernández-Hernando C, Cirino G, Sessa WC (2009) Akt1 is critical for acute inflammation and histamine-mediated vascular leakage. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. Aug 25;106(34): 14552-14557. [crossref]

- Gao WL, Li XH, Dun XP, Jing XK, Yang K, et al. (2020) Grape Seed Proanthocyanidin Extract Ameliorates Streptozotocin-induced Cognitive and Synaptic Plasticity Deficits by Inhibiting Oxidative Stress and Preserving AKT and ERK Activities. Curr Med Sci 40: 434-443. [crossref]

- Peng Y, Wang Y, Zhou C, Mei W, Zeng C. PI3K/Akt/mTOR Pathway and Its Role in Cancer Therapeutics: Are We Making Headway? Front Oncol. 2022 Mar 24;12: 819128. [crossref]

- Sun K, Luo J, Guo J, Yao X, Jing X, et al. (2020) The PI3K/AKT/mTOR signaling pathway in osteoarthritis: a narrative review. Osteoarthritis Cartilage 28: 400-409. [crossref]

- Ba X, Huang Y, Shen P, Huang Y, Wang H, et al. (2021) WTD Attenuating Rheumatoid Arthritis via Suppressing Angiogenesis and Modulating the PI3K/AKT/mTOR/HIF-1α Pathway. Front Pharmacol 27. [crossref]

- Liu C, He L, Wang J, Wang Q, Sun C, et al. (2020) Anti-angiogenic effect of Shikonin in rheumatoid arthritis by downregulating PI3K/AKT and MAPKs signaling pathways. J Ethnopharmacol 260. [crossref]

- Shi X, Jie L, Wu P, Zhang N, Mao J, et al. (2022) Calycosin mitigates chondrocyte inflammation and apoptosis by inhibiting the PI3K/AKT and NF-κB pathways. J Ethnopharmacol 28. [crossref]

- Lin C, Shao Y, Zeng C, Zhao C, Fang H, et al. (2018) Blocking PI3K/AKT signaling inhibits bone sclerosis in subchondral bone and attenuates post-traumatic osteoarthritis. J Cell Physiol 233: 6135-6147. [crossref]

- Lewis MJ (2024) Predicting best treatment in rheumatoid arthritis. Semin Arthritis Rheum 64S.[crossref]

- Li H, Shi W, Shen T, Hui S, Hou M, et al. (2023) Network pharmacology-based strategy for predicting therapy targets of Ecliptae Herba on breast cancer. Medicine (Baltimore) 102. [crossref]

- Zhou T, Guo S, Zhang Y, Weng Y, Wang L, et al. (2017) GATA4 regulates osteoblastic differentiation and bone remodeling via p38-mediated signaling. J Mol Histol 48: 187-197. [crossref]

- Wu Y, Xia L, Zhou Y, Xu Y, Jiang X (2015) Icariin induces osteogenic differentiation of bone mesenchymal stem cells in a MAPK-dependent manner. Cell Prolif 48: 375-384. [crossref]

- Wang G, Wang F, Zhang L, Yan C, Zhang Y (2021) miR-133a silencing rescues glucocorticoid-induced bone loss by regulating the MAPK/ERK signaling pathway. Stem Cell Res Ther 12. [crossref]

- Chen L, Zhan CZ, Wang T, You H, Yao R (2020) Curcumin Inhibits the Proliferation, Migration, Invasion, and Apoptosis of Diffuse Large B-Cell Lymphoma Cell Line by Regulating MiR-21/VHL Axis. Yonsei Med J 61: 20-29. [crossref]