DOI: 10.31038/CST.2022733

Abstract

Rationale: Glioblastoma (GBM), which accounts for 48% of all malignant central nervous system (CNS) tumors and 57% of gliomas, has a very poor prognosis. Patients with recurrent/persistent GBM after standard therapy usually die within six months. The case of an adult female with a recurrent/persistent GBM is presented here to detail/discuss the efficacy of ANP therapy (Antineoplaston A10 {Atengenal} and Antineoplaston AS2-1 {Astugenal}) in the treatment of this disease. Objectives: This patient was treated at the Burzynski Clinic (BC), as a Compassionate Exemption (CE) according to the Phase II Protocol, BT-20, which utilized ANP therapy in the treatment of patients with GBMs. ANP therapy was delivered via subclavian catheter and infusion pump and then by mouth. Tumor response was measured by sequential magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) of the brain utilizing gadolinium enhancement. Findings: This patient was diagnosed with GBM of the right temporoparietal region in May 1997, at age 45, and underwent two surgical resections, radiation therapy (RT), and gamma knife ablation elsewhere. At age 46 years and eight months, she presented to the BC with recurrent/persistent disease. She complained of weakness, dizziness, short-term memory loss, and nausea. She had difficulty speaking and walked with assistance due to discoordination and left-sided weakness. Baseline brain MRI at the BC revealed a measurable enhancing nodule in the surgical bed. ANP therapy was initiated in August 1998 and the patient achieved a complete response (CR) within five months. Now, 24 years later, the patient is doing well and showing no evidence of tumor recurrence. Conclusions: The utilization of ANP therapy to obtain a cure in a patient with recurrent/persistent GBM is presented. We conclude that ANP therapy is an attractive therapeutic option for adults with a GBM who are ineligible for or refuse standard therapy or demonstrate recurrent/persistent disease after standard therapy.

Keywords

Brain tumor, Glioblastoma, Persistent glioblastoma, Recurrent glioblastoma, Phase II studies

Introduction

Glioblastoma (GBM), the most common malignant central nervous system (CNS) tumor, accounting for 48% of all malignant tumors and 57% of gliomas, has a very poor prognosis [1]. Long term-survival is rare. Patients with recurrent/persistent GBM after standard therapy usually die within six months. Radiation therapy (RT) and chemotherapy therapy have not significantly affected outcome. Negative prognostic factors include advanced age, low Karnofsky Performance Status (KPS), and less than a gross total resection at initial surgery [2,3]. The overall survival (OS) rate at five years has remained constant for two decades at 5.8% [1,4,5].

Exposure to ionizing radiation [6], and the Li-Fraumeni and Lynch syndromes (<1% of cases) [7] are risk factors for GBM. Based on registry data from 2011 through 2015, the annual age-adjusted incidence of GBM is 3.2 per 100,000 population in the United States while the overall prevalence is 9.2 per 100,000 population [1]. The male: female ratio is 1:4.

Isocitrate dehydrogenase (IDH) enzymes participate in several major metabolic processes, such as the Krebs cycle, glutamine metabolism, lipogenesis and redox regulation [8-10]. Concerning the diagnosis of GBM, the 2016 revision of the World Health Organization (WHO) of CNS tumors, included IDH status, which resulted in three sub-groups, IDH-wild-type, IDH-mutant, and not otherwise specified (NOS) [11,12]. IDH–wild-type GBM is characterized by de novo development with no identifiable precursor lesion and represents 90% of patients with GBM [12]. On the other hand, IDH-mutant GBM, typically arises from a precursor diffuse or anaplastic astrocytoma and represents 10% of patients with GBM [12]. O6-methylguanine-DNA methyltransferase (MGMT) promoter methylation is seen in 30-50% of IDH-wild-type GBMs and may allow a better response to alkylating chemotherapy, especially temozolomide, providing for a better prognosis [13].

Gadolinium-enhanced magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) of the brain is used in the diagnosis and follow-up of GBM. T2-weighted, T2-fluid attenuated inversion recovery (T2-FLAIR), T1 weighted, and T1-weighted contrast-enhanced images are obtained. GBMs are gadolinium-enhancing and sequential T1-weighted contrast-enhanced images are utilized to determine the effect of therapy [14,15].

We present here the successful use of ANP therapy (Antineoplaston A10 {Atengenal} and Antineoplaston AS2-1 {Astugenal}) in the treatment of recurrent/persistent GBM in a 46 year and eight-month-old female, initially diagnosed at age 45 and treated with gross total resection, radiation therapy (RT), gamma knife ablation of recurrent tumor, and subsequent right lobectomy elsewhere. We also present the use of targeted therapy in the treatment of GBM, including our own preliminary results.

Materials and Methods

ANP research began in 1967, when significant deficiencies were noticed in the peptide content of the serum of patients with cancer compared with healthy persons. Initially ANP were isolated from the blood and later from urine [16]. Subsequent studies of the isolated ANP demonstrated that Antineoplaston A-10 and Antineoplaston AS2-1 were the most active ANPs. The chemical name of Antineoplaston A-10 is 3-phenylacetylamino-2,6-piperidinedione. It consists of the cyclic form of L-glutamine connected by a peptide bond to phenylacetyl residue. When given orally, Antineoplaston A10 resists the attack of gastric enzymes. In the small intestine, under alkaline conditions, 30% is digested into phenylacetylglutamine (PG) and phenylacetylisoglutaminate (isoPG) in a ratio of approximately 4:1. The mixture of synthetic PG and isoPG in a 4:1 ratio, dissolved in sterile water constitutes Antineoplaston A10 intravenous (IV) injection. Further metabolism of Antineoplaston A10 results in phenylacetate (PN). Both metabolites PG and PN have anticancer activity. The mixture of PN and PG in a 4:1 ratio, dissolved in sterile water constitutes Antineoplaston AS2-1 IV injection [17].

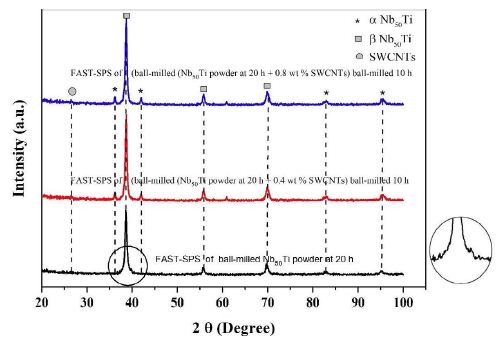

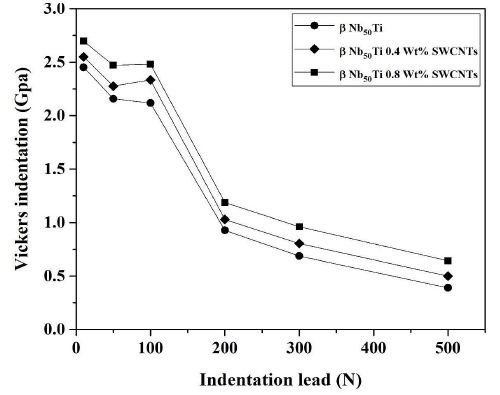

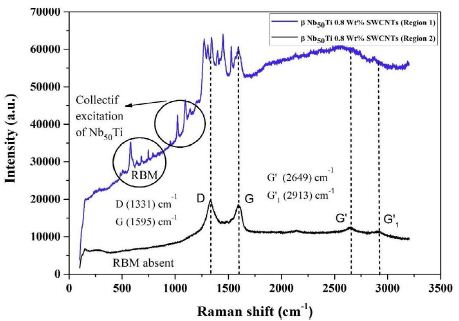

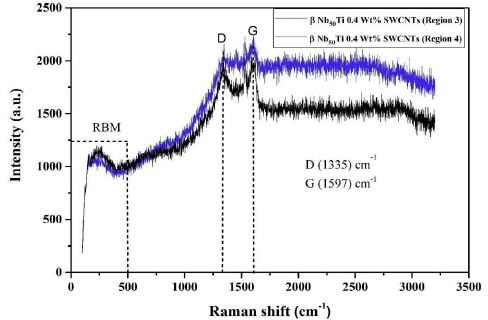

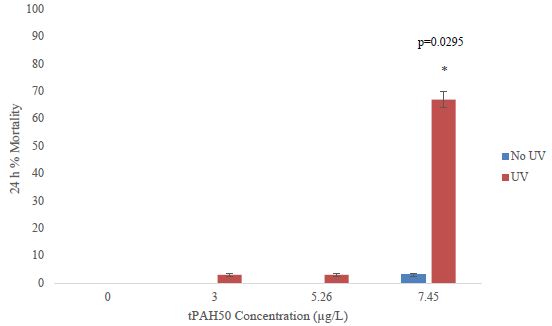

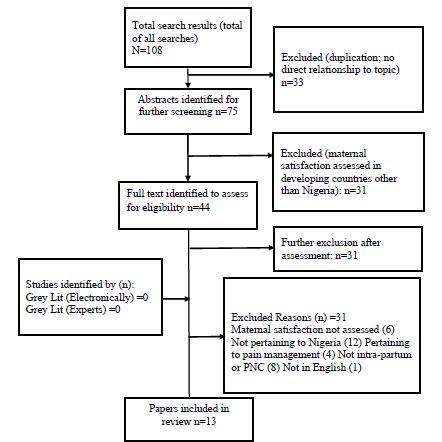

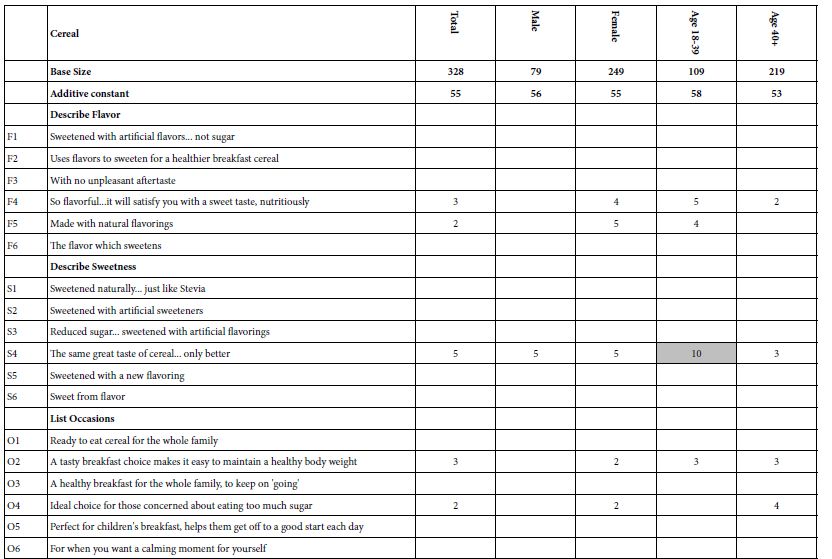

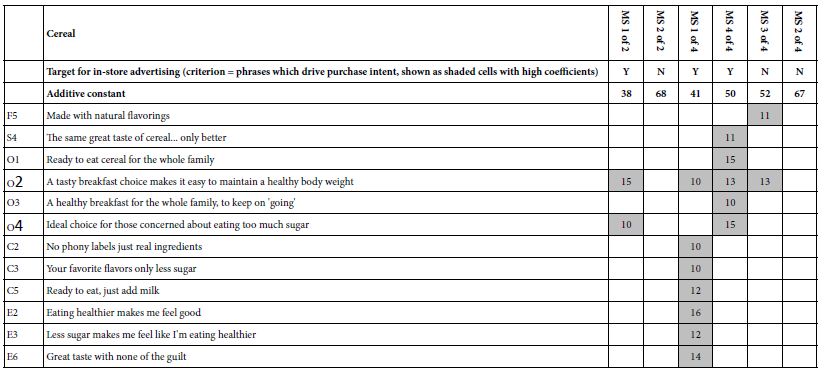

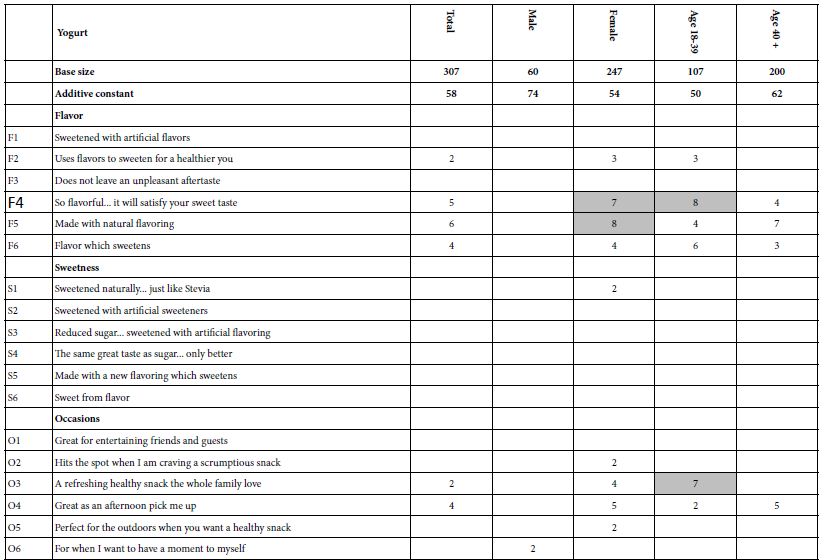

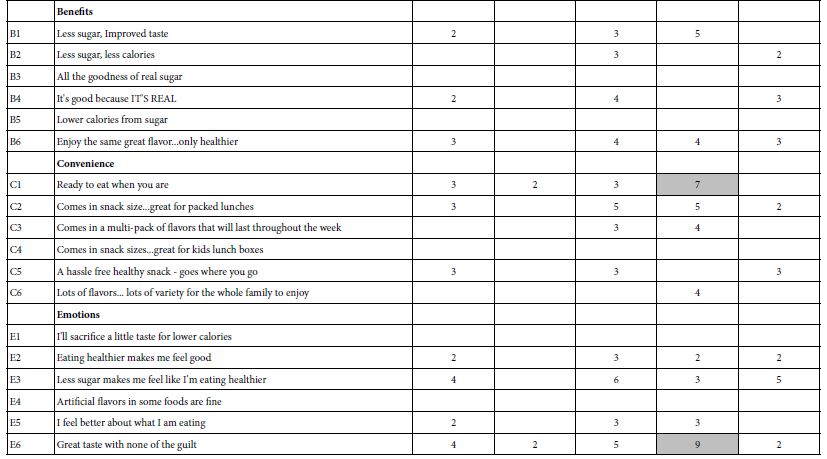

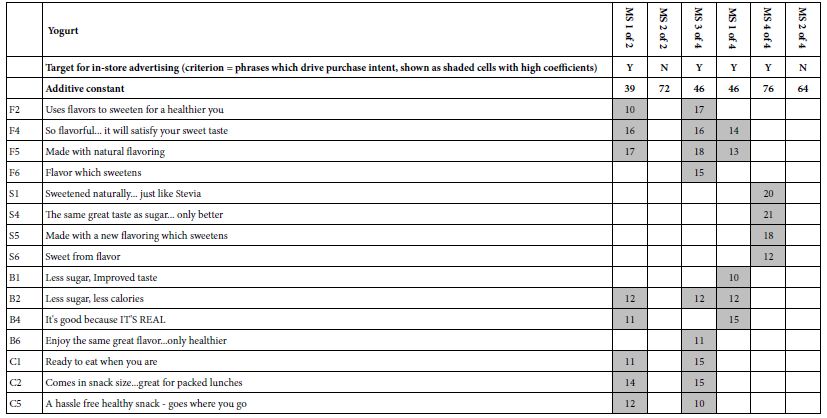

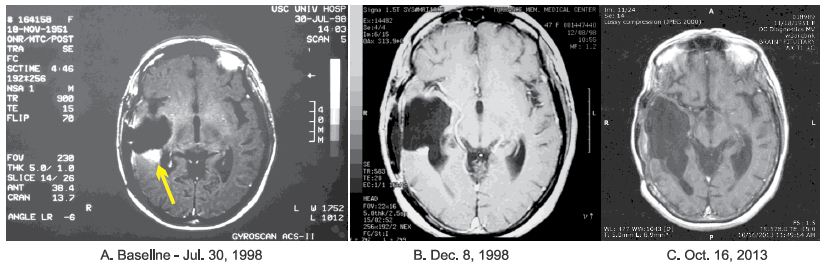

This patient was 45-years-old when she presented to a local hospital with a several month history of frequent headaches followed by left-sided weakness. Magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) of the brain showed a tumor in the right temporoparietal region. In May 1997, she underwent gross total resection of the tumor. Pathological examination of the microscopic slides from the submitted surgical specimen showed a GBM. The patient then received RT at a dose of 5940 cGy over 6 weeks. Six months later, she underwent gamma knife ablation of recurrent tumor. Seven months later, MRI of the brain MRI showed an enhancing lesion in the right temporal region. At that time, the patient underwent a right temporal lobectomy elsewhere. Histological examination of the surgical specimen provided a diagnosis of GBM. This was confirmed by positron emission tomography (PET). The patient was advised to undergo a third operation, but she refused and elected to be treated at the Burzynski Clinic (BC). MRI of the brain performed on July 30, 1998 showed a 1.3 cm x 1.2 cm (volume = 1.56 cm2) enhancing nodule in the surgical bed (Figure 1).

During her baseline evaluation at the BC, the patient complained of weakness, dizziness, short-term memory loss, discoordination, and nausea. She was found to have difficulty speaking and could not walk without assistance due to discoordination and left-sided weakness. Both optical discs were blurred. Karnofsky Performance Status (KPS) was 50. On August 10, 1998, the patient began ANP therapy according to Protocol BT-20, “Antineoplaston Therapy in Treating Adults with Residual/Recurrent/Progressive Glioblastoma Multiforme”. Intravenous (IV) ANP therapy was delivered via a subclavian catheter and a programmable infusion pump.

This Phase II trial was conducted in accordance with the U.S. Code of Federal Regulations, Title 21, Parts 11, 50, 56 and 312; the Declaration of Helsinki (1964) including all amendments and revisions; the Good Clinical Practices: Consolidated Guideline (E6), International Conference on Harmonization (ICH) and Guidance for Industry (FDA). By participating in this study protocol, the investigators agreed to provide access to all appropriate documents for monitoring, auditing, IRB review and review by any authorized regulatory agency.

Results

Response to ANP therapy was measured by serial brain MRIs, with and without gadolinium contrast. Tumor volume was calculated as the sum of the volume of all measurable lesions (>5 mm diameter) with imaging. The response criteria were as follows: a CR indicated complete disappearance of all enhancing tumor while a partial response (PR) indicated a 50% or greater reduction in total enhancing tumor volume. CR and PR required a confirmatory brain MRI performed at least four weeks after the initial finding. PD indicated a 25% or greater increase in enhancing tumor volume, or new enhancing disease, while stable disease (SD) did not meet the criteria for PR or PD [15]. All brain MRIs were reviewed by a prominent outside radiologist. Consent was obtained from the patient for publication of the brain MRIs presented in this report.

The patient’s starting dose of A10 was 1.23 g/kg/d and was gradually increased to 10.48 g/kg/d and subsequently reduced to 5.20 g/kg/d. Her starting dose of AS2-1 was 0.15 g/kg/d and was gradually increased to 0.17 g/kg/d. On December 8, 1998, MRI of the brain showed that the patient had achieved a complete response (Figure 1). IV ANP therapy was discontinued after 18.5 months [18-44].

Figure 1: Axial MRI images of the brain: A – July 30, 1998 – Baseline magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) of the brain showing measurable enhancing tumor (see arrow), with a volume of 1.56 cm2, in the surgical bed of a temporal lobectomy. B – December 8, 1998 – MRI of the brain showing a complete response (CR) with no enhancing tumor seen. C – October 16, 2013 – Post-therapy MRI of the brain showing maintenance of the CR.

Adverse events (AEs) were graded according to the Common Terminology Criteria for Adverse Events Version 3.0 (CTCAE v.3). While receiving IV ANP therapy, the patient experienced two Grade 1 AEs possibly related to IV ANP therapy. Both resolved.

Once IV ANP therapy was completed, the patient began oral ANP therapy. The starting dose of both A10 and AS2-1 was 0.05 g/kg/d and both were gradually increased to 0.14 g/kg/d. All ANP therapy was discontinued 31 months from treatment start.

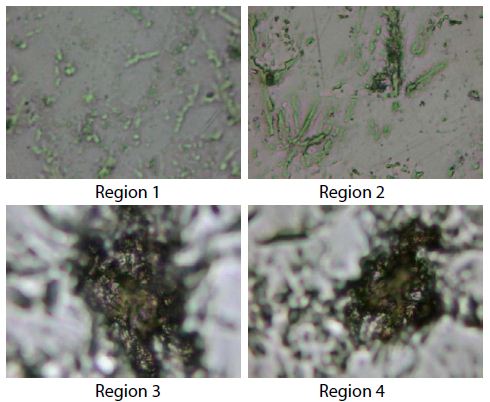

During the course of her ANP therapy, the patient made substantial clinical recovery. After 9 months of IV ANP therapy, she was able to walk with the help of a walker. Her KPS increased to 80. At 4 years after treatment completion, the patient was able to walk with a cane. Serial follow-up brain MRIs, with the latest performed in October 16, 2013, showed no recurrence of disease (Figure 1). At last follow-up (September 9, 2022), the patient was maintaining an excellent quality of life. The patient has not received any additional anti-tumor therapy since ANP therapy was discontinued and has consented to publication of the radiographs presented herein (Figure 2).

Figure 2: Photograph of the patient, on an exercise bicycle, following completion of ANP therapy and achievement of a complete response (CR).

Discussion

Based on a Phase III study by R. Stupp and colleagues, published in 2005, standard therapy for GBM consists of maximal surgical resection, followed by 60 Gray (Gy) RT over 6 weeks with concomitant daily temozolomide followed by a further 6 cycles of maintenance temozolomide [18]. In patients with good performance status (KPS > 60), the median OS was 14.6 months for RT plus temozolomide vs. 12.1 months for RT alone (P < 0.001).

After standard therapy, most patients recur within 6 months. In this setting, there is no standard-of-care systemic therapy. Alkylating chemotherapy is commonly used, including lomustine, carmustine, and additional temozolomide although the benefits are modest and only patients with MGMT promoter methylation are likely to benefit [19-21]. Salvage chemotherapy with combined procarbazine, lomustine, and vincristine may have some activity, although its use is limited by significantly greater toxicity [22,23]. The quality of data for individual chemotherapy agents or regimens is generally poor and comparison of studies is difficult.

The US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) granted accelerated approval to single-agent bevacizumab based solely on early phase 2 data indicating improved progression-free survival (PFS), although no OS benefit was seen [24,25]. Subsequent randomized phase 3 trials have demonstrated that bevacizumab in combination with lomustine improves PFS compared with lomustine alone (4.2 months vs. 1.5 months; [P < 0.001]), but again, without any change in OS [26].

ANP therapy’s mechanism of action differs from that of RT or cytotoxic chemotherapy. Growth of normal cells is controlled by cell cycle progression genes (oncogenes) and by cell cycle arrest genes (tumor suppressor genes). In cancer, alteration of these control genes in malignant cells favors aggressive cell proliferation. Evidence suggests that ANP therapy affects 112 genes in the GBM genome and functions as “molecular switches” which “turn on” tumor-suppressor genes and “turn off” oncogenes [27,28]. Hence, the antineoplastic action of ANP therapy in DIPG involves restoration of cell cycle control, induction of programmed cell death, and interference with cancer cell metabolism and nuclear transport.

Current sequencing technology allows for advanced understanding of the GBM genome and underlying molecular biology [29]. Identifying crucial and targetable genomic alterations can expand our therapeutic options.

Tyrosine kinase inhibitors (TKIs) have failed to demonstrate significant efficacy when targeting epidermal growth factor (EGFR) [30-32]. For persistent EGFR-amplified GMB, depatuxizumab mafodotin, an antibody drug conjugate targeting EGFR, in combination with temozolomide, has shown promising activity in a Phase II trial [33]. In contrast to this, a Phase III trial of depatuxizumab mafodotin in combination with standard therapy for newly diagnosed EGFR-amplified glioblastoma was stopped early because an interim analysis showed no OS benefit [34].

PTEN, PIK3CA, and PIK3R1 are frequently seen in IDH-wild-type GBM [35]. However, buparlisib, in persistent GBM, and everolimus and temsirolimus, in newly-diagnosed GBM, have not shown efficacy as single agents [36-38]. Following accelerated approval to bevacizumab, trials of vascular endothelial growth factor (VEGF) and multikinase TKIs, such as cediranib, lomustine, tivozanib, pazopanib, and sunitinib have shown little or no activity as single-agent therapy [39-43].

While single-agent targeted therapy has not yet been shown to be effective in the treatment of recurrent/persistent GBM, we have published preliminary results that encourage the simultaneous use of multiple targeted agents as therapy for recurrent GBM [44]. Twenty-nine adult patients with recurrent/persistent GBM were treated at the BC between 9/11/2015 and 06/23/2018. Seven patients had no prior treatment with bevacizumab, had radiologic evidence of recurrent GBM, had MRI assessment of tumor response, and formed the study population. The treatment plan for any patient was based on genomic profiling and consisted of Antineoplaston AS2-1 and selected targeted agents for specific genomic abnormalities [45]. The median treatment time for these seven patients was 101 days (range: 55-208 days). An OR was achieved in six patients (85.7%) with a CR in four patients (57.1%) and a PR in two patients (28.6%). PD was seen in one patient (14.3%).

Conclusion

We present here the case of a 45-year-old female with a GBM, who presented to the BC at age 46 years and eight months with recurrent/persistent GBM and obtained a cure with ANP therapy, having obtained a CR and survived 24 years since the start of ANP therapy. This therapy is an attractive option for patients with recurrent/persistent GBM who are ineligible for or refuse standard therapy or demonstrate recurrent/persistent disease following standard therapy. Multiple Phase II clinical studies of ANP therapy in a variety of low-and high-grade brain tumors under the Burzynski Research Institute’s (BRI’s) IND # 43,742 have now been completed and numerous articles have been published [46-85]. Based on the preliminary study cited above [44], we propose a Phase II study of AS2-1 plus targeted therapy in patients with recurrent/persistent GBM following standard of care therapy.

References

- Ostrom QT, Patil N, Cioffi G, Waite K, Kruchko C, et al. (2020)CBTRUS statistical report: Primary brain and other central nervous system tumors diagnosed in the United States in 2013-2017. Neuro Oncol 22: 1-96. [crossref]

- Lacroix M, Abi-Said D, Fourney DR, Gokaslan ZL, Shi W, et al. (2001)A multivariate analysis of 416 patients with glioblastoma multiforme: prognosis, extent of resection, and survival. J Neurosurg 95: 190-198. [crossref]

- Lamborn KR, Chang SM, Prados MD (2004)Prognostic factors for survival of patients with glioblastoma: recursive partitioning analysis. Neuro Oncol 6: 227-235. [crossref]

- Ostrom QT, Cote DJ, Ascha M, Kruchko C, Barnholtz-Sloan JS (2018) Adult glioma incidence and survival by race or ethnicity in the United States from 2000 to 2014. JAMA Oncol 4: 1254-1262. [crossref]

- Ostrom QT, Gittleman H, Farah P, Ondracek A, Chen Y, et al. (2013) CBTRUS statistical report: primary brain and central nervous system tumors diagnosed in the United States in 2006-2010. Neuro Oncol 15: 1-56. [crossref]

- Fisher JL, Schwartzbaum JA, Wrensch M, Wiemels JL (2007) Epidemiology of brain tumors. Neurol Clin 25: 867-890. [crossref]

- Scheurer ME, Etzel CJ, Liu M, Jill BS, Wiklund F, et al. (2010)Familial aggregation of glioma: a pooled analysis. Am J Epidemiol 172: 1099-1107. [crossref]

- Koh HJ, Lee SM, Son BG, Lee SH, Ryoo ZY, et al. (2004) Cytosolic NADP+-dependent isocitrate dehydrogenase plays a key role in lipid metabolism. J Biol Chem 279: 39968-39974. [crossref]

- Badur MG, Muthusamy T, Parker SJ, Ma S, McBrayer SK, et al. (2018) Oncogenic R132 IDH1 mutations limit NADPH for de novo lipogenesis through (D)2-hydroxyglutarate production in fibrosarcoma sells. Cell Rep 25: 1018-1026. [crossref]

- Lee SH, Jo SH, Lee SM, Koh HJ, Song H, et al. (2004) Role of NADP+-dependent isocitrate dehydrogenase (NADP+-ICDH) on cellular defense against oxidative injury by gamma-rays. Int J Radiat Biol 80: 635-642. [crossref]

- Louis DN, Perry A, Reifenberger G, Deimling AV, Dominique FB, et al. (2016) The 2016 World Health Organization Classification of Tumors of the Central Nervous System: a summary. Acta Neuropathol 131: 803-820. [crossref]

- Ohgaki H, Kleihues P (2013) The definition of primary and secondary glioblastoma. Clin Cancer Res 19: 764-772. [crossref]

- Zawlik I, Vaccarella S, Kita D, Mittelbronn M, Franceschi S, et al. (2009) Promoter methylation and polymorphisms of the MGMT gene in glioblastomas: a population-based study. Neuroepidemiology 32: 21-29. [crossref]

- Shukla G, Alexander GS, Bakas S, Nikam R, Talekar K, et al. (2017) Advanced magnetic resonance imaging in glioblastoma: a review. Chinese Clin Oncol 6: 40. [crossref]

- Wen PK, Macdonald DR, Reardon DA, Cloughesy TF, Sorensen AG, et al. (2010) Updated response criteria for high-grade gliomas: Response Assessment in Neuro-Oncology (RANO) working group. J Clin Oncol 28: 1963-1972. [crossref]

- Burzynski SR (1976) Antineoplastons: Biochemical defense against cancer. Physiol Chem Phys 8: 275-279. [Crossref]

- Burzynski SR (1986) Synthetic antineoplastons and analogs: Drugs of the future. 11: 679-688.

- Stupp R, Mason WP, van den Bent MJ, Weller M, Fisher B, et al. (2005) Radiotherapy plus concomitant and adjuvant temozolomide for glioblastoma. N Engl J Med 352: 987-996. [crossref]

- Weller M, Tabatabai G, Kastner B, Felsberg J, Steinbach JP, et al. (2015) MGMT promoter methylation is a strong prognostic biomarker for benefit from dose-intensified temozolomide rechallenge in progressive glioblastoma: the DIRECTOR Trial. Clin Cancer Res 21: 2057-2064. [crossref]

- Wick W, Puduvalli VK, Chamberlain MC, Van den Bent MJ, Carpentier AF, et al. (2010) Phase III study of enzastaurin compared with lomustine in the treatment of recurrent intracranial glioblastoma. J Clin Oncol 28: 1168-1174. [crossref]

- Jungk C, Chatziaslanidou D, Ahmadi R, Capper D, Bermejo JL, et al. (2016)Chemotherapy with BCNU in recurrent glioma: analysis of clinical outcome and side effects in chemotherapy-naïve patients. BMC Cancer 16: 81. [crossref]

- Carvalho BF, Fernandes AC, Almeida DS, Sampaio LV, Costa A, et al. (2015) Second-line chemotherapy in recurrent glioblastoma: a 2-cohort study. Oncol Res Treat 38: 348-354. [crossref]

- Schmidt F, Fischer J, Herrlinger U, Dietz K, Dichgans J, et al. (2006) PCV chemotherapy for recurrent glioblastoma. Neurology 66: 587-589. [crossref]

- Friedman HS, Prados MD, Wen PY, Mikkelsen T, Schiff D, et al. (2009) Bevacizumab alone and in combination with irinotecan in recurrent glioblastoma. J Clin Oncol 27: 4733-4740. [crossref]

- Kreisl TN, Kim L, Moore K, Duic P, Royce C, et al. (2009) Phase II trial of single-agent bevacizumab followed by bevacizumab plus irinotecan at tumor progression in recurrent glioblastoma. J Clin Oncol 27: 740-745. [crossref]

- Wick W, Gorlia T, Bendszus M, Taphoorn M, Sahm F, et al. (2017) Lomustine and bevacizumab in progressive glioblastoma. N Engl J Med 377: 1954-1963. [crossref]

- Burzynski SR, Patil S (2014) The effect of Antineoplaston A10 and AS2-1 and metabolites of sodium phenylbutyrate on gene expression in glioblastoma multiforme. J Cancer Ther 5: 929-945.

- Burzynski SR, Janicki T, Burzynski G (2015) Comprehensive genomic profiling of recurrent classic glioblastoma in a patient surviving eleven years following antineoplaston therapy. Cancer Clin Oncol 4: 41-52.

- Cancer Genome Atlas Research Network (2008) Comprehensive genomic characterization defines human glioblastoma genes and core pathways. Nature 455: 1061-1068. [crossref]

- Yung WK, Vredenburgh JJ, Cloughesy TF, Nghiemphu P, Klencke B, et al. (2010) Safety and efficacy of erlotinib in first-relapse glioblastoma: a phase II open-label study. Neuro Oncol 12: 1061-1070. [crossref]

- Raizer JJ, Abrey LE, Lassman AB, Chang SM, Lamborn KR, et al. (2010) A phase II trial of erlotinib in patients with recurrent malignant gliomas and nonprogressive glioblastoma multiforme post radiation therapy. Neuro col 12: 95-103. [crossref]

- Prados MD, Chang SM, Butowski N, Deboer R, Parvataneni R, et al. (2009) Phase II study of erlotinib plus temozolomide during and after radiation therapy in patients with newly diagnosed glioblastoma multiforme or gliosarcoma. J Clin Oncol 27: 579-584. [crossref]

- van den Bent M, Eoli M, Sepulveda JM, Smits M, Walenkamp A, et al. (2020) INTELLANCE 2/EORTC 1410 randomized phase II study of Depatux-M alone and with temozolomide vs temozolomide or lomustine in recurrent EGFR amplified glioblastoma. Neuro Oncol 229: 684-693. [crossref]

- Lassman A, Pugh S, Wang T, Aldape K, Gan H, et al. (2019) ACTR-21. A randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled phase 3 trial of depatuxizumab mafodotin (ABT-414) in epidermal growth factor receptor (EGFR) amplified (AMP) newly diagnosed glioblastoma (nGBM). Neuro Oncol 21: 17.

- Cancer Genome Atlas Research Network(2008)Comprehensive genomic characterization defines human glioblastoma genes and core pathways. Nature 455: 1061-1068. [crossref]

- Wen PY, Touat M, Alexander BM, Mellinghof IK, Ramkissoon S, et al. (2019)Buparlisib in patients with recurrent glioblastoma harboring phosphatidylinositol 3-kinase pathway activation: an open-label, multicenter, multi-arm, phase II trial. J Clin Oncol 37: 741-750. [crossref]

- Ma DJ, Galanis E, Anderson SK, Schiff D, Kaufmann TJ, et al. (2015) A phase II trial of everolimus, temozolomide, and radiotherapy in patients with newly diagnosed glioblastoma: NCCTG N057K. Neuro Oncol 17: 1261-1269. [crossref]

- Wick W, Gorlia T, Bady P, Platten M, Vandenbent MJ, et al. (2016) Phase II study of radiotherapy and temsirolimus versus radiochemotherapy with temozolomide in patients with newly diagnosed glioblastoma without MGMT promoter hypermethylation (EORTC 26082). Clin Cancer Res 22: 4797-4806. [crossref]

- Batchelor TT, Mulholland P, Neyns B, Nabors LB, et al. (2013) Phase III randomized trial comparing the efficacy of cediranib as monotherapy, and in combination with lomustine, versus lomustine alone in patients with recurrent glioblastoma. J Clin Oncol 31: 3212-3218. [crossref]

- Lombardi G, De Salvo GL, Brandes AA, et al. (2019) Regorafenib compared with lomustine in patients with relapsed glioblastoma (REGOMA): a multicentre, open-label, randomised, controlled, phase 2 trial. Lancet Oncol 20: 110-119.

- Kalpathy-Cramer J, Chandra V, Da X, Ou Y, Emblem KE, et al. (2017)Phase II study of tivozanib, an oral VEGFR inhibitor, in patients with recurrent glioblastoma. J Neurooncol 131: 603-610. [crossref]

- Iwamoto FM, Lamborn KR, Robins HI, Mehta MP, Chang SM, et al. (2010) Phase II trial of pazopanib (GW786034), an oral multi-targeted angiogenesis inhibitor, for adults with recurrent glioblastoma (North American Brain Tumor Consortium Study 06-02). Neuro Oncol 12: 855-861. [crossref]

- Hutterer M, Nowosielski M, Haybaeck J, Embacher S, Stockhammer F, et al. (2014) A single-arm phase II Austrian/German multicenter trial on continuous daily sunitinib in primary glioblastoma at first recurrence (SURGE 01-07). Neuro Oncol 16: 92-102. [crossref]

- Burzynski SR, Janicki T, Beenken S (2019) Treatment of recurrent glioblastoma multiforme (rGBM) with Antineoplaston AS2-1 in combination with targeted therapy. Cancer Clin Oncol 8: 1-15.

- Burzynski SR, Burzynski GS, Janicki TJ (2014) Recurrent glioblastoma multiforme: A strategy for long-term survival. J Cancer Ther 5: 957-976.

- Burzynski SR, Conde AB, Peters A, Saling B, Ellithorpe R, et al. (1999) A Retrospective Study of Antineoplastons A10 and AS2-1 in Primary Brain Tumors. Clin Drug Invest 18: 1-10.

- Burzynski SR, Weaver RA, Bestak M, Lewy RI, Janicki TJ, et al. (2003) Phase II study of Antineoplastons A10 and AS2-1 (ANP) in children with recurrent and progressive multicentric glioma: A preliminary report. Neuro Oncol 5: 358. [crossref]

- Burzynski SR, Weaver RA, Lewy RI, Janicki TJ, Jurida GF, et al. (2004) Phase II study of Antineoplaston A10 and AS2-1 in children with recurrent and progressive multicentric glioma: A preliminary report. Drugs in R & D 5: 315- [crossref]

- Burzynski SR, Lewy RI, Weaver R, Janicki T, Jurida G, et al. (2004) Long-term survival and complete response of a patient with recurrent diffuse intrinsic brain stem glioblastoma multiforme. Integ Cancer Ther 3: 257-261. [crossref]

- Burzynski SR, Weaver R, Bestak M, Janicki T, Jurida G, et al. (2004) Phase II studies of antineoplastons A10 and AS2-1 (ANP) in children with atypical teratoid/rhabdoid tumors (AT/RT) of the central nervous system: A preliminary report. Neuro Oncol 6: 427. [crossref]

- Burzynski SR, Weaver R, Bestak M, Janicki T, Szymkowski B, et al. (2004) Treatment of primitive neuroectodermal tumors (PNET) with antineoplastons A10 and AS2-1 (ANP): Preliminary results of phase II studies. Neuro Oncol 6: 428.

- Burzynski SR, Weaver R, Lewy R, Janicki T, Jurida G, et al. (2004) Phase II study of antineoplaston A10 and AS2-1 in children with recurrent and progressive multicentric glioma: A preliminary report. Drugs R&D 5: 315-326. [crossref]

- Burzynski SR, Weaver RA, Janicki, T, Szymkowski B, Jurida G, et al. (2005) Long-term survival of high-risk pediatric patients with primitive neuroectodermal tumors treated with Antineoplastons A10 and AS2-1. Integ Cancer Ther. 4(2):168-177. [crossref]

- Burzynski SR. (2006) Targeted Therapy for Brain Tumors. In: Yang AV, editor. Brain Cancer Therapy and Surgical Interventions. Nova Science Publishers, Inc, New York.

- Burzynski SR, Janicki, TJ, Weaver RA, Burzynski B (2006) Targeted therapy with Antineoplastons A10 and AS2-1 of high grade, recurrent, and progressive brainstem glioma. Integ Cancer Ther 5: 40-47. [crossref]

- Burzynski SR (2006) Treatments for astrocytic tumors in children: Current and emerging strategies. Ped Drugs 8: 167-168. [crossref]

- Burzynski SR (2007) Recent clinical trials in diffuse intrinsic brainstem glioma. Cancer Ther 5: 379- 390. [crossref]

- Burzynski S, Janicki T, Burzynski G, Marszalek A (2014) Long-term survival (>13 years) in a child with recurrent diffuse pontine gliosarcoma: A case report. J Ped Hematol Oncol 36: 433-439. [crossref]

- Burzynski SR, Janicki TJ, Burzynski GS, Marszalek A (2014) A phase II study of antineoplastons A10 and AS2-1 in children with high-grade glioma: Final report (Protocol BT-06) and review of recent trials. J Cancer Ther 5: 565-577.

- Burzynski SR, Janicki TJ, Burzynski GS (2014) A phase II study of antineoplastons A10 and AS2-1 in adult patients with recurrent glioblastoma multiforme: Final report (Protocol BT-21). J Cancer Ther 5: 946-956.

- Burzynski SR, Janicki TJ, Burzynski, GS, Marszalek A, Brookman S (2014) A phase II study of antineoplastons A10 and AS2-1 in children with recurrent, refractory or progressive primary brain tumors: Final report (Protocol BT-22). J Cancer Ther 5: 977-988.

- Burzynski SR, Janicki TJ, Burzynski GS, Brookman S (2014) Preliminary findings on the use of targeted therapy with pazopanib and other agents in combination with sodium phenylbutyrate in the treatment of glioblastoma multiforme. J Cancer Ther 5: 1423-1437.

- Burzynski GS, Janicki TJ, Marszalek A. (2014) Long-term survival (>20 years) of a child with brainstem glioma treated with antineoplastons A10 and AS2-1: A case report. Neuro Oncol 11: 16.

- Burzynski SR, Janicki TJ, Burzynski GS, Marszalek (2014) The response and survival of children with recurrent diffuse intrinsic pontine glioma based on phase II study of antineoplastons A10 and AS2-1 in patients with brainstem glioma. Childs Nerv Syst 30: 2051-2061. [crossref]

- Burzynski SR, Burzynski G, Janicki J, Marszalek A (2015) Complete response and Long-term survival (>20 years) of a child with tectal glioma: A case report. Pediatr Neurosurg 50: 99-103. [crossref]

- Burzynski SR, Janicki TJ, Burzynski G (2015) A phase II study of Antineoplastons A10 and AS2-1 injections in adult patients with recurrent anaplastic astrocytoma: Final report (Protocol BT-15). Cancer Clin Oncol 442: 13-23.

- Burzynski SR, Janicki TJ, Burzynski GS, Marszalek A (2015) A Phase II Study of Antineoplastons A10 and AS2-1 in adult patients with newly-diagnosed anaplastic astrocytoma: Final report (Protocol BT-08). Cancer lin Oncol 4: 28-38.

- Burzynski SR, Burzynski GS, Marszalek A, Janicki J, Martinez-Canca J (2015) Long-term survival (over 20 years), complete response and normal childhood development in medulloblastoma treated with Antineoplastons A10 and AS2-1. J Neurol Stroke 2: 00054.

- Burzynski SR, Burzynski GS, Marszalek A, Janicki TJ, Martinez-Canca JF (2015) Long-term survival over 21 years and pathologically confirmed complete response in pediatric anaplastic astrocytoma: A case report. J Neurol Stroke 2: 00072.

- Burzynski SR, Burzynski GS, Brookman S (2015) A case of sustained objective response of recurrent/progressive diffuse intrinsic pontine glioma with phenylbutyrate and targeted agents. J Cancer Ther 6: 40-44.

- Burzynski SR, Janicki, T, Burzynski G, Marszalek A (2015) A phase II study of antineoplastons A10 and AS2-1 in patients with brainstem gliomas: The report on non-diffuse intrinsic pontine glioma (Protocol BT-11). J Cancer Ther 6: 334-344. [crossref]

- Burzynski SR, Janicki T, Burzynski G (2015) A phase II study of Antineoplastons A10 and AS2-1 in adult patients with primary brain tumors: Final report (Protocol BT-09). J Cancer Ther 6: 1063-1074.

- Burzynski SR, Janicki TJ, Burzynski GS (2016) Primary CNS tumors and leptomeningeal, disseminated and/or multicentric disease in children treated in Phase II studies with Antineoplastons A10 and AS2-1. Cancer Clin Oncol 5: 38-48.

- Burzynski SR, Janicki TJ, Burzynski GS (2016) A phase II study of antineoplastons A10 and AS2-1 in children with low-grade astrocytomas: Final report (Protocol BT-13). J Cancer Ther 7: 837-850.

- Burzynski SR, Janicki TJ, Burzynski GS (2017) Antineoplastons A10 and AS2-1 in the treatment of children with optic pathway glioma. Final report (Protocol BT-23). Cancer Clin Oncol 6: 25-35.

- Burzynski SR, Janicki TJ, Burzynski GS, Marszalek A (2017) A phase II study of Antineoplastons A10 and AS2-1 in children with brain tumors: Final report (Protocol BT-10). J Cancer Ther 8: 173-187. [crossref]

- Burzynski, SR, Janicki, T, Burzynski, GS, Beenken S (2021) Long-term survival (27.7 years) following IV Antineoplaston Therapy (ANP) in a 36-year-old-female with a progressive diffuse intrinsic pontine glioma (DIPG). Int J Radiol Imaging Technol 7: 073-078.

- Burzynski, SR, Burzynski, GS, Janicki, T, Beenken S (2021) Long-term survival (23 years) in a 26-year-old male after Antineoplaston therapy for a progressive, diffuse intrinsic pontine glioma: A case report. Int J Brain Disord Treat 6: 038-044.

- Burzynski, SR, Janicki T, Burzynski GS, Beenken S (2021) Resolution of clinical signs, a complete response, and long-term survival (>23 Years) in a 3 and ½ month female with a newly diagnosed diffuse intrinsic pontine glioma treated with antineoplastons. Biomed Res Clin Prac 6: 1-6.

- Burzynski, SR, Janicki T, Burzynski GS, Beenken S (2021) Diffuse intrinsic pontine glioma in an 11-year-old female treated with antineoplastons: Complete response and > 25-year survival. Pediatr Neonatal Med 1: 1-5.

- Burzynski SR, Janicki T, Burzynski GS, Beenken S (2022) A 25-year-old female with diffuse intrinsic pontine glioma surviving for more than nine years following treatment with antineoplastons. Int J Clin Oncol Cancer Res 7: 1-7.

- Burzynski SR, Burzynski GS, Janicki T, Beenken S (2022) Twenty-two-year survival in a 15-year-old female with a recurrent posterior fossa ependymoma treated with antineoplastons. Oncol Clin Res 3: 99-105. [crossref]

- Burzynski S, Burzynski G, Janicki T, Beenken S (2022) Recurrent and progressive ganglioglioma in an 11-year-old male treated with antineoplastons: Partial response with more than nine years and nine months survival and complete resolution of clinical symptoms/signs. Biomed Res J 37: 1-13.

- Burzynski S, Burzynski G, Janicki T, Beenken S (2022) Newly-diagnosed Multicentric Pilocytic Astrocytoma: Complete response and > 22 Years Survival in a Six Year and Nine-month-old Female treated with Antineoplastons. Int J Clin Oncol Cancer Res 7: 76-82.

- Burzynski SR, Burzynski GC, Janicki T, Beenken S (2022) Outcome in Four Children with Persistent, Recurrent, and Progressive Gangliogliomas Treated in Phase II Studies with Antineoplastons A10 and AS2-1. Neurol Neurosci 3: 1-9.