DOI: 10.31038/JCCP.2022514

Abstract

Title: Epidemiological, clinical, therapeutic, evolutionary and prognostic aspects of PPCM in the Internal Medicine and Cardiology department of the Amirou Boubacar Diallo National Hospital: Retrospective and prospective descriptive study about 64 cases.

Introduction: PPCM is a heart failure secondary to left ventricular systolic dysfunction with LVEF <45% or a fraction of shortening <30%, Occurred towards the end of pregnancy or in the months following childbirth (mainly the month following the childbirth) without any other identifiable cardiac cause it is a worldwide disease whose epidemiology varies considerably with a multifactorial etiology. The true incidence or prevalence of PPCM in Africa and many other populations remains unknown. The objective of the study was to bring out the epidemiological, clinical, therapeutic, evolutionary and promostic aspects of PPCM.

Methodology: This is a retrospective and prospective descriptive and analytical study on PPCM in the internal medicine and cardiology department of HNABD from January 1, 2017 to December 31, 2019 for the retrospective part and from January 1, 2020 as of December 31, 2020 for the prospective part.

Results: The prevalence of PPCM was 8.68% for heart failure; 3.82% compared to all heart disease and 2.06% compared to all entries. The average age is 28.2 years with extremes of 15 and 5 years. The clinical presentation was essentially that of global heart failure in 81.3% of cases. The alteration of the ejection fraction of the left ventricle was found in all patients, ie 100% divided between moderate in none, moderate in 53.1% and severe in 46.9% of cases. The treatment of PPCM in our series is that of heart failure. Four therapeutic measures were the basis of symptomatic treatment in all hospitalized patients: diet and diet regimen in 100% of them and ACE inhibitors in 95.3%. B blockers were used in 73.4% of patients outside the acute phase of the disease. Anticoagulants were used in 27 of the patients, i.e. 42.1% Digoxin in 16patients or 25% and antiplatelet drugs in 54.7% of patients. SLGT2 Inhibitors was used in 32.8% (21 patients). Bromocriptine was used 9.4% of the time. Thromboembolic complications are the most frequent, namely EP in 10.9% of cases, DVT 4.7%. Only one case of arrhythmia was found. Like other complications of pneumonia, pleurisy and severe anemia have been found. The mortality rate 17.2% related to cardiogenic shock in 36.36% of cases. The prognostic factors found are Young age, primiparity, 7 out of 11 deceased patients were between 15 and 20 years old and had only one parity, i.e. 63.6%, with no statistically significant link with respectively (P=0.09) and (P=0.18). 63 1% of deceased patients came from poor and underprivileged rural areas without any statistically significant link (P=0.66). 81.8% of deceased patients had a low socioeconomic level, with no statistically significant association between SSE and death (P=0.21). Nine (9) of the eleven (11) deceased patients had a severe alteration of LVEF on admission, ie 81.8%, with a very significant link (P=0.005).

Conclusion: Knowledge of the epidemiological aspects of PPCM is necessary for the optimization of patient care. SLGT2 Inhibitors and Bromocriptine seem effective in these cases.

Keywords

PPCM, Epidemiology, Clinical, Therapeutic, SLGT2 inhibitors, Bromocriptine, Niger

Introduction

Peripartum cardiomyopathy (PPCM) is a rare heart failure characterized as an idiopathic cardiomyopathy presenting with heart failure secondary to left ventricular systolic dysfunction affecting women in late pregnancy or in the months following childbirth [1-3]. This is a diagnosis of exclusion.

Its incidence is estimated at 1/3000-4000 births [4]. The highest incidence in Africa is in the Sudano-Sahelian zone with a prevalence of 2.7 per 1000 pregnancies [5,6]. It is responsible for 10% of female heart disease in Niamey (Niger) [6]. Several factors seem to play a role in promoting hormonal changes during childbirth (fall in cardioprotective fetal estrogen levels, synthesis of cardiotoxic 16KDa-prolactin) [7]. The classic picture is that of heart failure (HF), which generally mimics the signs of a normal pregnancy, often leading to delayed diagnosis and avoidable complications [8]. Transthoracic echocardiography is the key examination, making it possible to confirm the diagnosis, eliminate differential diagnoses and monitor progress [7]. Medical management is similar to that of heart failure with reduced left ventricular ejection fraction of other etiologies, but adjustments during pregnancy are necessary to ensure fetal safety [8]. It is a serious pathology whose evolutionary potential is extremely rapid and totally unpredictable, with the possibility of sudden onset of refractory cardiogenic shock in the first 24 to 48 hours justifying treatment in a center with specialized cardiovascular resuscitation [2,7]. Complete recovery from PPCM is possible in half of the patients, while the other half will retain dilated cardiomyopathy responsible for more or less severe chronic heart failure [7]. Subsequent pregnancy carries a substantial risk of relapse and even death in the event of incomplete myocardial recovery. [8].

Given its frequency, its high morbidity, the absence of known etiology as well as the multiplicity of contributing factors; an update has been initiated.

Methods

This is a descriptive and analytical retro-prospective study which was spread over a period of 4 years (January 1, 2017 to December 31, 2019 for the retrospective part and from January 1, 2020 to December 31, 2020 for the prospective part) in the cardiology department of the National Amirou Boubacar Diallo (HNABD) hospital in Niamey.

Were included in the study, women regardless of their age, their race who presented heart failure (HF) between the eighth month of pregnancy and the first five months postpartum without etiology found and in whom dilated cardiomyopathy (DCM) was diagnosed on cardiac ultrasound. Not included in the study were women with onset of heart failure before the eighth month of pregnancy or after the first five months postpartum, women with known heart disease or any other cause of heart failure.

Data collection was carried out from hospitalization records and the consultation register using a survey sheet taking into account the epidemiological, clinical, paraclinical, therapeutic and evolutionary aspects during the study period. The variables studied included: demographic data and prenatal consultation diaries, cardiovascular risk factors, mode of onset or decompensation of heart failure, mode and course of delivery. The chronology of the signs of CI in relation to childbirth, and the data of the physical and paraclinical examination. Certain examinations were systematically requested such as chest X-ray, electrocardiogram, cardiac echo-Doppler, blood count, blood sugar, creatinine. D-dimers, cardiac enzymes and chest CT angiography were requested depending on the clinical and electrical context.

In addition to the absence of a cause of heart failure, the following ultrasound criteria were essential to retain the diagnosis of PPCM: the dilation of at least the left ventricle (DTDVG>52 mm) associated with left ventricular systolic dysfunction, i.e. say a lower left ventricular ejection fraction (LVEF) of 0.50 and/or a shortening fraction <30%.

Definition of Variables

Estimation of Socioeconomic Status

In our study we arbitrarily estimated the socio-economic level (SES) of our patients taking into account three parameters which are diet, physical work during pregnancy and level of education, according to the following scale:

Affluent

Patient having to eat a rich and varied diet regularly; exempted from intense physical work during pregnancy; secondary or higher school level.

Average

Patient regularly having a satiety diet, not exempted from intense physical work during pregnancy, primary school level or illiterate.

Low

Patient who does not regularly have enough food, subjected to intense physical work during pregnancy; illiterate.

Classification of LVEF according to the Latest ESC 2018 Guidelines: [7]

Preserved LVEF

This is an LVEF greater than 50%.

Moderately reduced LVEF

This is an LVEF between 40% and 49%.

Low LVEF

This is an LVEF below 40%.

Severely Altered LVEF

This is an LVEF <30%

High PRVG

Translated by an E / A ratio > 2.

Normal PRVG

Translated by an E/A ratio <1.

Favorable Evolution

It was defined by the remission of the symptoms and the relaxation of the patients.

Death

These are all patients with PMPC who died regardless of the cause of death.

We identified 91 suspected cases of PPCM. We rejected 27 patients who had not benefited from cardiac ultrasound. Thus we have a sample of 64 patients who met all our criteria.

Data Analysis

The data was entered, processed and analyzed on a computer with IBM SPSS statistics version 20 Data editor software after creating an input mask. The results were presented in the form of tables and graphs using the Office 2016 package (Word and Excel). The statistical test used in this study was the chi² with a degree of significance P < 0.05.

Limits of the study

– Some patients are seen after the acute phase, explaining the absence of certain signs or their low proportion;

– Financial difficulties preventing distant patients from coming for consultation and/or carrying out certain additional examinations;

– The lack of information in certain files;

Results

Epidemiological Aspects

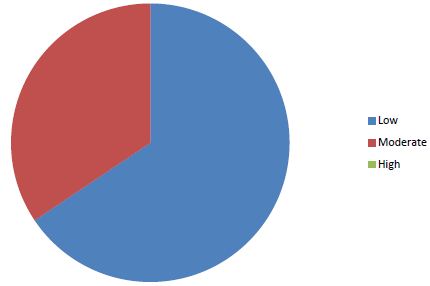

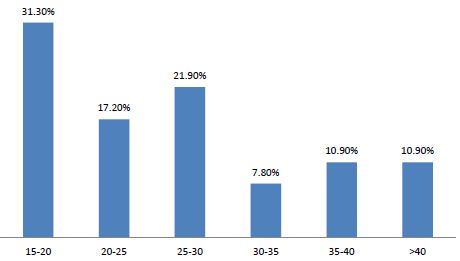

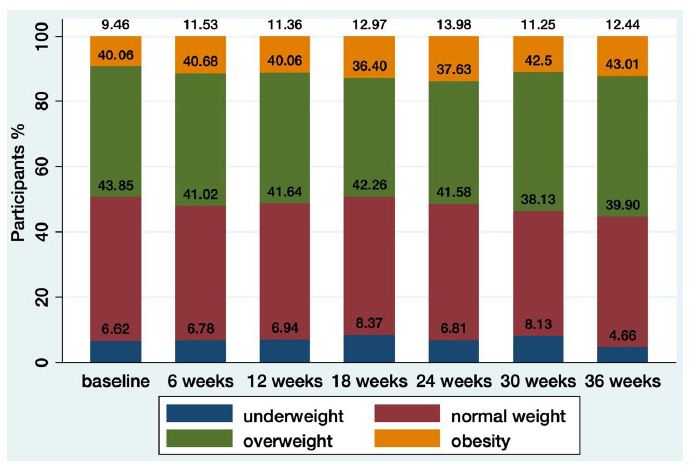

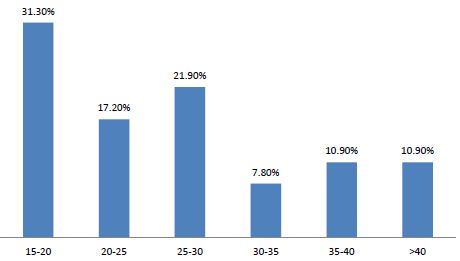

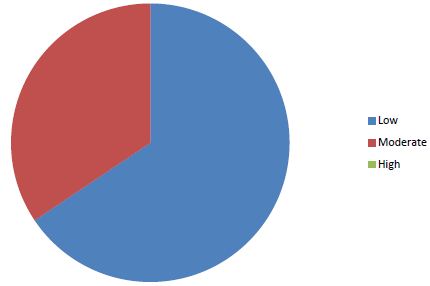

Sixty-four cases of peripartum cardiomyopathy (PPCM) were recorded in 4 years, an average of 16 cases per year. The average age was 28.2 years (extremes of 15 and 55 years). The age group 15 and 20 was the majority (31.30%) (Figure 1). PPCM represented 1/356 births, its hospital prevalence was 2.06% (64 PPCM/3094 patients admitted), 3.82% of heart disease (64/1672), 8.68% of total CI (64/737). Unemployed women made up 90.6% of the sample. The majority of patients had unfavorable socioeconomic conditions (65.6%) (Figure 2). Multiparous women were the most represented with 38.80% of cases (Table 1). The average parity was 3.07 (extremes of 1 to 6).

Figure 1: Distribution of patients by age group

Figure 2: Distribution of patients according to socio-economic status

Table 1: Data on epidemiological aspects

|

Paramètres

|

Numbers |

Percentage (%)

|

| Occupation

–Housewife

-official

– Pupil/student

-shopkeeper/seamstress |

58

3

2

1

|

90,60

4,70

3,10

1,60

|

| Education level

-Non school

-University

-High school

-Middle School

-Primary |

44

2

3

10

5

|

68,80

3,10

4,70

15,60

7,80

|

| History

Personnal

-HBP

-Chirurgical

-Gynaeco-obsetrics

Number of children;

1

2-3

4-5

6 and more

Abortion

0

1

2

3 |

6

10

24

15

11

14

60

3

0

1

|

9,40

15,60

37,5

23,4

17,2

21,9

93,7

4,7

0

1,6

|

| Parity

-Grand multiparity

-Multiparity

-Pauciparity

-Primiparity |

12

13

16

23

|

18,80

20

25

35,90

|

| Twins |

7

|

10,9 |

|

PNC

|

19 |

30

|

| Type of birth

-Low way

-Caesarean section |

58

6

|

90,60

9,40

|

| NB prognosis

– living child

-Deceased children

-Breastfeeding |

53

14

48

|

88,20

21,9

75

|

| Risk factors

-High sodium diet

-Hot bath

– Taking medication during pregnancy

– Intense physical work during pregnancy |

48

64

3

38

|

75

100

5

60

|

| Family history

-HBP

-Diabetes

-Heart disease |

12

6

1

|

18,80

9,40

1,60

|

PNC: Pre-natal Consult, HBP: High Blood Pressure, NB: New Born

Clinical Aspects

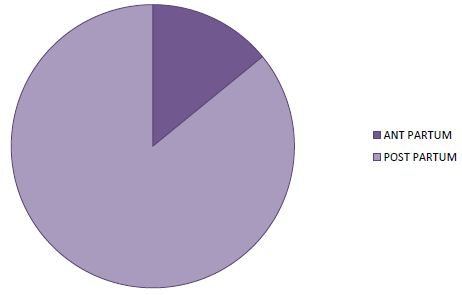

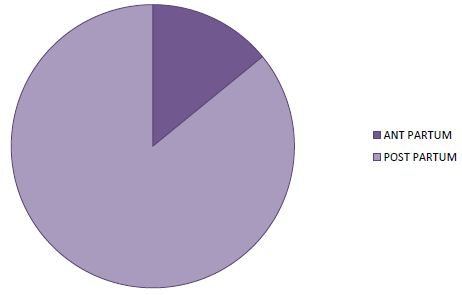

In 85.9% of cases, symptoms appeared postpartum (Figure 3). There was a delay in consultation in all patients with an average delay of 30 days (extreme: 06 to 120 days). Symptoms were dominated by exertional dyspnoea (100%) (Table 2). The decompensation was done on the mode of isolated left IC in 18.8% of the cases and on the mode of global IC in 81.2% of the cases. Table 2 summarizes the data of the clinical examination.

Figure 3: Distribution of patients according to time to onset in relation to childbirth

Table 2: The clinical data of the patients

|

Parameters

|

Number (n)

|

Percentage (%)

|

| Functional signs

-Dyspnea

-Cough

-Chest pain

-Hemoptysis |

64

43

42

12

|

100

89,10

65,52

34,4

|

| General signs

General condition (GC)

– altered

– passable

– Good

CONJUNCTIVES

-Colored

-Little colored

-Blades

Blood pressure

-Normal

-Low

-HighTempérature

– Feverish

-Non Feverish |

29

25

10

32

15

17

33

21

10

22

42

|

45,3

39,1

15,6

50

23,4

26,6

51,60

32,80

15,60

34,4

65,5

|

| PHYSICAL SIGNS

-Turgescence of the jugular veins

-Ascites

-Breath of TI

-MI Breath

– Peripheral edema

– Hepato-jugular reflux

-Hepatomegaly

-Crackling rales

– Deflected tip shock

-Gallop sound

-Tachycardia |

10

24

3

35

61

52

57

53

45

29

59

|

15,60

37

4,7

56,30

95,30

81,30

89,10

82,80

70,30

45,30

92,20

|

| Left heart failure |

12

|

18,80

|

| Global heart failure |

52

|

81,30

|

| Consultation times

-One week

-three weeks

-a month

-two months

-three months

-four months |

19

7

22

10

3

3

|

30

10

35

15

5

5

|

MI: Mitral Insufficiency, TI: Tricuspid Insufficiency

X-ray and Electrocardiographic Signs

Cardiomegaly was found in all patients (100%) with an average cardiothoracic index of 0.70 (extreme 0.57 to 0.86).

Sinus tachycardia as well as left ventricular hypertrophy were noted in the respective proportions of 87.5% and 59.4%. Thirty-three patients (51.6%) had left atrial hypertrophy. Two patients had a conduction disorder (3.10%). In 29 cases (28.1%) there were nonspecific repolarization disorders associated with ventricular hypertrophy (Table 2).

Echocardiographic Data

LV dilation was noted in all patients with a mean end-diastolic diameter of 61.93 mm (range 54 to 76 mm). The left atrium was dilated in 43 patients with an average diameter of 46.17 mm (range 23.60 and 59). The right ventricle was dilated in 7 patients (10.93%). The average EF was 30.99% with extremes of 14 and 44.60%. The average of the FR was 12.85%. LV systolic dysfunction was severe in 43.60% of cases. All patients presented with global parietal hypokinesia. Cardiac Doppler echo had objectified a left intraventricular thrombus in 14 patients (21.9%). LV filling pressures were increased in 58 patients (90.6%). Pulmonary arterial hypertension was significant in 59.37% of cases with an average of 50.43mmHg (extremes: 23 and 74 mmHg). Pericardial effusion was noted in 19 patients (29.7%).

Treatment

A lifestyle and diet was recommended in 100% of our patients. Diuretics were the most used molecules; followed by CE inhibitors, then beta-blockers and digitalis with respectively 100%; 95.3%; 73.4% and 25%. Platelet antiaggregants were used in 54.7% of cases, anticoagulants in 42.2% of cases and AVKs in 21.9% of cases. SLGT2 Inhibitors were used in 21 CASES(32.8). Bromocriptine was only used in 9.4% of cases.

Evolution in Hospitalization

Complications occurred in 15 patients, i.e. 23.4%, including 10 cases of thromboembolic disease, including 7 cases (10.9%) of PE, 3 cases (4.7%) of deep vein thrombosis (DVT), 4 cases cardiogenic shock (6.3%) and 1 case of arrhythmia (1.6%). The evolution was favorable in 82.8% of our patients and death occurred in 17.2% of cases.

The average duration of hospitalization of our patients was 10 days (extreme 7 to 33 days). Fifty-three patients (82.8%) had found a clinical cure with disappearance of the signs. We noted 11 deaths (17.2%). 81.80% of deceased patients had severe LVEF impairment with a statistically significant link (P=0.034). Within our sample, in the multivariate analysis after logistic regression, it appears that only severe alteration of LVEF, low socio-economic status and primiparity were factors statistically associated with an unfavorable evolution with respectively P=0.034; P=0.044 and P=0.025.

Discussion

The hospital prevalence of PPCM was 2.06% in our study. In Africa, the prevalence of PPCM varies according to the studies [9,10]. In the West, the disease appears to be less frequent with an incidence of 1/3000 to 1/15000 [11]. These results confirm that PPCM is a pathology that is more prevalent in women of black origin [12]. Other associated factors are advanced maternal age [13]. In this study, the average parity was 3.07 (extremes: 1 and 6) with 82.93% multiparous. This testifies to the frequency of this condition in multiparous women [13]. In addition, 93.75% of our patients were from low socio-economic conditions. We agree with the authors that low socioeconomic status is also a risk factor for PPCM [14].

In total, maternal age over 30 years, multiparity, unfavorable socio-economic conditions are the risk factors for PPCM found in this study. Other factors such as the notion of chronic hypertension and prolonged use of tocolytics, twin pregnancies cannot be formally retained in this study [13].

We have observed a great delay in consultation among our patients. Dyspnea on exertion was the main symptom with an advanced stage (NYHA classification). The same observations were reported in the African literature [10,14]. These are patients in reality in whom the symptoms start earlier but ignorance and poverty would be the causes of delays in consultation and most of the patients are found in a table of global IC with a state of anasarca. The women considered the edema of the limbs as a normal fact linked to a pregnancy and it was in view of the increasing intensity of the dyspnea that the majority had consulted. The other symptoms found were precordialgia and cough. Precordial pain ranged from simple precordial tingling to angina-like pain with chest tightness. Their frequency varies according to the authors [10,11,14]. These chest pains associated with coughing pose a real diagnostic problem because they can raise the suspicion of a pulmonary embolism. In all cases, the patients are sufficiently put on anticoagulants at a curative dose. Tachycardia with a galloping sound, systolic murmur of mitral insufficiency and crackles were the most frequent auscultatory data found in our patients. Several authors have reported these same physical examination data but at widely varying rates [10,14]. These statistical disparities are explained by the subjective nature of clinical examinations, hence the need for paraclinical examinations. Cardiomegaly was noted in 100% of cases in this study. Cardiomegaly is constant in heart failure but remains non-specific [4]. This is an essential element in our regions where cardiac ultrasound is rare and inaccessible to the population.

On the EKG, serious arrhythmias are reported in the literature. Ferrière out of 11 observations noted 1 case of ventricular tachycardia [15]. It is a ventricular tachycardia detected by Holter ECG recording. Sinus tachycardia, LVH and nonspecific repolarization disorders are frequently found electrical abnormalities [10,14].

Faced with a recent woman who complained of dyspnea, the discovery of cardiomegaly associated with sinus tachycardia and LVH should lead to the PPCM being withheld until proven otherwise. Cardiac ultrasound will only come to confirm the diagnosis and assess the impact and complications.

Faced with a recent woman who complained of dyspnea, the discovery of cardiomegaly associated with sinus tachycardia and LVH should lead to the PPCM being withheld until proven otherwise. Cardiac ultrasound will only come to confirm the diagnosis and assess the impact and complications.

Echocardiographic signs are one of the criteria for defining PPCM and global parietal hypokinesia is the constant disorder found [15]. Cavitary dilatation as well as LV systolic dysfunction were severe in our patients. These are the consequences of the delay in consultation and diagnosis. PPCM is a highly emboligenic pathology [11,16]. The reasons mentioned are multiple: blood hypercoagulability during pregnancy [17], dilated cardiomyopathy which appears in a recent childbirth, reduced maternal mobility during the last months of pregnancy, compression of the IVC by the fetal mobile. All these reasons justify curative anticoagulant treatment in our patients.

The evolution of PPCM is unpredictable [18]. The inter-birth interval depends on the time taken for systolic function to return to normal. When heart failure persists beyond the sixth month after delivery, mortality is 28% in one year and 85% in 5 years [19]. Forms resistant to medical treatment represent 10% of cases [18]. When PPCM is cured, the risk of recurrence in a subsequent pregnancy cannot be excluded. The advice to be given to patients is therefore adapted to each case. Some elements are considered poor prognosis. These are of African origin, age greater than 30 years, a delay in the appearance of symptoms greater than 3 months, the persistence of clinical signs 6 months after the onset of the disease, an ICT greater than 0.6 and the characteristics of the left ventricle: insignificant dilation (LTDVD <55-60 mm), an ejection fraction < 30%, a shortening fraction less than 20% at the time of diagnosis [17,20]. If we consider these factors, we would say that all of our patients had a poor prognosis.

The prognosis of the disease is unpredictable. Many patients die despite the treatment, while others progress quite favorably and after 6 to 12 months of treatment, complete recovery occurs [2,17,20,21]. Between recovery and death, the evolution is that of chronic heart failure with DMC [22]. The obstetrical prognosis is poor. Heart failure occurs in 50 to 80% of cases in subsequent pregnancies, with mortality that can reach 60% [21,23]. Given a very high mortality rate during subsequent pregnancies, we agreed with our multiparous patients to opt for a contraindication to definitive pregnancy. Primiparas wishing to have another pregnancy are monitored and decisions will be made on a case-by-case basis.

Conclusion

Peripartum cardiomyopathy is a serious cardiac complication of pregnancy. It is common in Niger as in other black African countries. It occurs preferentially in the postpartum. The risk factors were: maternal age over 30, multiparity and unfavorable socioeconomic conditions. There was a significant delay in diagnosis. The clinical picture was that of global heart failure with significant dilation of the heart chambers and severe alterations in myocardial performance. SLGT2 Inhibitors and Bromocriptine added to the classical HF therapy seem effective.

References

- Karen Sliwa, Mark C Petrie, Peter van der Meer, Alexandre Mebazaa, Denise Hilfiker-Kleiner, et al. (2020) Clinical presentation and management,6-month outcomes in women with peripartum cardiomyopathy: an ESC EORP registry. European Heart Journal 1-10.

- Koenig.T, Hilfiker-Kleiner.D, Bauersachs.J (2018) Peripartum cardiomyopathy. Department of Cardiology and Angiology, Hannover Medical School, Hannover, Germany.

- Gibelin P (2020) Cardiomyopathie du péripartum. Presse Med Form.

- Moili M, Valenzano, Menada M, Bentivoglio G, Ferrero (2010) Péripartum cardiomyopathy. Arch Gynecol Obstet 281: 183-8

- Seronde M-F (2018) La cardiomyopathie du péri-partum.Arch Mal Coeur Vaiss Prat.

- Cenac A, Moumio OM, Develoux M, Soumane I, Lamothe F, Gaulier Y et al. (1985) COLL. Cardiopathie de l’adulte à Niamey (Niger), enquete épidemologique à propos de 162 cas, obsertion. Cardiol Trop 11: 125-133.

- Diarra A (1983) La myocardiopathie du post-partum. (Syndrome de Meadows). Thèse Med, Bamako 4: 93.

- Vanzetto G, Martin A, Bouvais H, Marliere S, Durand MJ (2018) Cardiovascular diseases during pregnancy. European Haert Journal 10: 1093

- Melinda B. Davis, MD, Zolt Arany, MD, PHD, Dennis M. McNamara et al. (2020) Peripartum Cardiomyopathy JACC State-of-the-Art Review.

- Niakara A, Belemwire S, Nebie L, Drabo Y (2000) Cardiomyopathie du post-partum de la femme noire africaine: Aspects épidémiologiques, cliniques et évolutifs de 32 cas. Cardiol Trop 26: 69-73.

- Mielniczuk LM, Williams L, Davis DR, et al. (2006) Frequency of péripartum cardiomyopathy. Am J Cardiol.;97(12): 1765-1768. [crossref]

- Gentry MB, Dias JK, Luis A, Patel R, Thornton J, Reed GL (2010) African-American women have a higher risk for developing peripartum cardiomyopathy. Journal of the American College of Cardiology.;55(7): 654-659. [crossref]

- Heider AL, Kuller JA, Strauss RA, Wells SR (1999) Peripartum cardiomyopathy: a review of the literature. Obstetrical and Gynecological Survey 54: 526-531. [crossref]

- Katibi I (2003) Peripartum cardiomyopathy in Nigeria. Hesp Med 64: 249.

- Ferriere M, Sacrez A, Bouhour J, et al. (1990) La myocardiopathie du péripartum: aspects actuels. Etude multicentrique: 11 observations. Arch Mal C’ur 83: 1563-1569.

- Bennani S, Loubaris M, Lahlou I, Badidi, Haddour N, Bouhouch R, Cheti M, Arharbi M (2003) Cardiomyopathie du péripartum révélée par l’ischémie aigue d’un membre inférieur. Annales de cardiologie et angéologie 52: 382-385.

- Walkira S, Carnério de carvalho M, Cleide K, Rossi E (2002) Pregnancy and Peripartum Cardiomyopathy: A Comparative and Prospective Study. Arq Bras Cardiol 79: 489-493. [crossref]

- Burban M (2002) Pregnancy and dilated or hypertrophic cardiomyopathies. Arch Mal C’urVaiss 95: 287-291.

- Silwa K, Skudick D, Candy G, Bergemann A, Hopley M, Sareli P (2002) The addition of pentoxifylline to conventional therapy improves outcome in patients with péripartum cardiomyopathy. The European Journal of Heart Faillure 4: 305-309.

- Chapa JB, Heiberger HB, Weinert L, DeCara J, Lang R, Hibbard U (2005) Prognostic value of echocardiography in peripartum cardiomyopathy. Obstet Gynecol 105: 1303-1308. [crossref]

- Goland S, Modi K, Bitar F, et al. (2009) Clinical profile and predictors of complications in peripartum cardiomyopathy. J Card Fail 15: 645-650. [crossref]

- Rifat K (1995) La cardiomyopahie du peripartum (CMPP) Méd Et Hyg 53: 2548-2555.

- Hamdoum L, Mouelhi C, Kouka H, et al. (1993) Cardiomyopathie du péripartum. Analyse de trois cas et revue de la littérature. Rev FR Gynécol Obstét 88: 273-275.