DOI: 10.31038/PSYJ.2021353

Abstract

Health experts globally are currently concerned with health systems strengthening through community engagement. Community Health Volunteers is a core element of community engagement although confronted by the problem of high attrition rates and hence high cost of training to sustain community level service delivery through volunteers. This paper focuses on the identification of volunteers likely to be retained, at the time of selection by a theory based assessment framework to guide investment in volunteer training and support.

Methodology: The study was undertaken in three stages starting with literature review to identify theories to underpin the development of a volunteer assessment framework, and to inform the testing of the validity and reliability of the framework in determining task preference. A cross sectional survey was carried out to investigate the relationship between volunteer motives and task preference by comparing motives and task preference among volunteers with non-volunteers in Western Kenya. We obtained the eight motives we examined from literature, and tasks from a list of common health activities undertaken by volunteers in Kenya. We rated the task preference of 1062 respondents for each of the tasks on a 1-5 Likert scale. We compared task preference ratings by motives and volunteer status.

Findings: Volunteer motive constructs were identified from literature guided by theories underpinning volunteerism. Theories identified were Social exchange theory, Functional theory and Role identity theory. Eight motives constructs were identified which were grounded on these theories. Altruistic motive was strongly associated with most tasks investigated. Non-volunteers showed greater association with materialistic tasks. Routine, long duration health tasks such as mother and child healthcare and curative care were significantly associated more with altruistic than with material gain motives. Short-term tasks such as helping in disease outbreaks, and participation in immunization campaigns were associated with both altruistic and material gain motives. The self-seeking motives tended to be associated only with short-term tasks.

Conclusion: The resultant volunteer assessment framework consists of two core constructs, altruistic value and material gain. They are effective in identifying the motives of those likely to volunteer long term and short term. Altruistic and material gains were constructs in which the perceptions of volunteers and non-volunteers differed most significantly. The study demonstrated that it is possible to classify tasks according to the motives they satisfy identify and to select volunteers that are likely to serve long term. Assessing the motivational needs of volunteers can assist the management in providing the most effective placement of volunteers into activities that meet their needs and thus maximize their effectiveness.

Keywords

Volunteers, Motives, Constructs, Task, Preference, Assessment framework, Screening, Health service

Introduction

Health experts globally are currently concerned with health systems strengthening through community engagement, World Health Organization Astana Declaration [1]. Community Health Volunteers (CHVs) is a core element of community engagement although confronted by the problem of high attrition rates and hence high cost of training to sustain community level service delivery through volunteers. To address retention of volunteers, assessing and identifying individuals likely to remain committed to volunteer work for long at recruitment, is considered crucial to sustainability. A logical assumption underlying the assessments is that volunteers whose motives are satisfied would be more active in service delivery and more likely to continue for long.

Community Health Volunteers (CHVs) have a central role to provide the vital link between communities and formal health systems as they know and understand the health needs of the communities within which they live and work. Moreover, they can be trained and deployed quickly. Evidence from available data on the use of community health volunteers from Gambia, South Africa, Tanzania, Zambia, Madagascar and Ghana suggests that these workers enhance the performance of community engagement initiatives and that they are cost effective [2] CHVs with minimal additional training can deliver treatment for important diseases, such as malaria, HIV, TB and even isolate and care for COVID 19 cases that are either asymptomatic or exhibit mild illness.

A variety of trials have shown substantial reductions in child mortality through community case management by CHVs, guided by World Health Organization community case management guide [3]. One such trial in Tigray, Ethiopia, showed a 40% reduction in under-five mortality after local co-coordinators were trained to teach mothers to give anti-malarial medicines to their sick children in the home [4]. CHVs were promoted for implementation of packages of interventions such as antenatal home visits, promotion of immediate and exclusive breastfeeding, skin-to-skin care, appropriate care of the skin and umbilical stump [5], and recognition and treatment with antibiotics of sick newborns [6] to reduce neonatal mortality. Delivery of interventions in the home by CHVs was viewed as critical during the first month of life, when many families observe a period of postpartum confinement which makes them less likely to seek care or advice from outside the home [7]. Syed and colleagues found that CHVs were effective in tracking pregnant women through the postnatal period and in raising awareness of appropriate maternal and newborn care practices [8].

Implementation of newborn care interventions is relatively complex compared to other CHV interventions, such as the promotion of immunizations. To be effective, CHVs must gain mastery of a range of information and skills related to their area of responsibility, and know how to adapt counseling strategies to households with varied composition and needs. This, in turn, required greater investment by programs in CHV selection and training.

Studies indicated that volunteer motivation was driven by many elements including intrinsic factors such as individual goals, sense of altruism and self-efficacy. They suggested that extrinsic factors include peer approval, the incentives provided, and future expectations [9]. They concluded that high rates of attrition undermined programs’ investments in CHVs, and potentially limited the effectiveness of community engagement interventions and that higher attrition rates were associated with higher costs. High attrition rates had been reported in many CHV programs, as summarized by Bhattacharyya et al. [10], reporting attrition rates for CHVs ranging from 3.2% to 77%. The evaluation of these studies did not take into account the theoretical models that underpinned motives for volunteering. This study specifically focused on the identification of CHVs likely to be retained long term, at the time of selection by a theory based assessment framework to guide investment in volunteer training and support. The main objective was to identify, from literature, the features of an instrument that could be used to assess the underlying motivational drives of volunteers in Kenya, their validity and reliability as well as the relationship of the motives with their task preference in health service delivery at the community level.

Methodology

We carried out the study in three stages starting with literature review to identify motive construct that could be used in an assessment framework and theories that underpin volunteerism, then we tested the validity and reliability of the identified motive constructs in the Western Kenya setting, and finally we related motives to task preference, and compared volunteers to non-volunteers.

The Elements of a Framework for Assessing CHVs Motives from Literature

Volunteer motive constructs were identified from literature guided by theories underpinning volunteerism. The search used electronic database engines that provided an international word search for articles in public health, social sciences and development. These included Google scholar, Research gate, the Cochrane reviews, the National Institute of Health and Clinical Excellence (NICE), Pubmed Health, Science Direct and Popline. The purpose was to identify generic models and guidance for assessment of volunteer motives focused on the following terms used in the title, and abstract: volunteer motives assessment frameworks, volunteer task preference, volunteer task performance.

The review considered worldwide experiences, and was not time limited, while paying keen attention to published models, examples and frameworks from the African region, looking out for motives that researchers had included in assessment tools, as well as their assessment items and methods that had been used to carry out such assessments. The motives from models and frameworks identified were synthesized in to a draft volunteer’s assessment framework. The resultant framework was subjected to face and content validity testing through a pretest among respondents similar to the study population as described by [11], before it was eventually field tested more rigorously for construct validity and reliability in the local context. The pretest showed that the tool was able to measure the constructs of interest. It provided insight on how potential participants might interpret and respond to the assessment items.

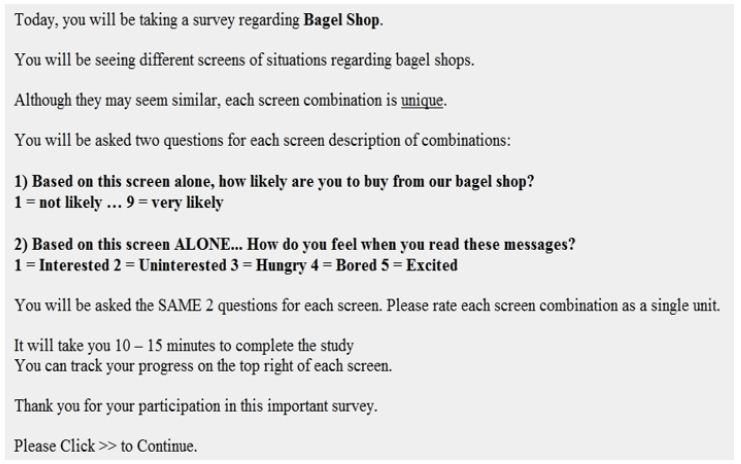

Assessing Validity and Reliability of Volunteer Motives from the Framework

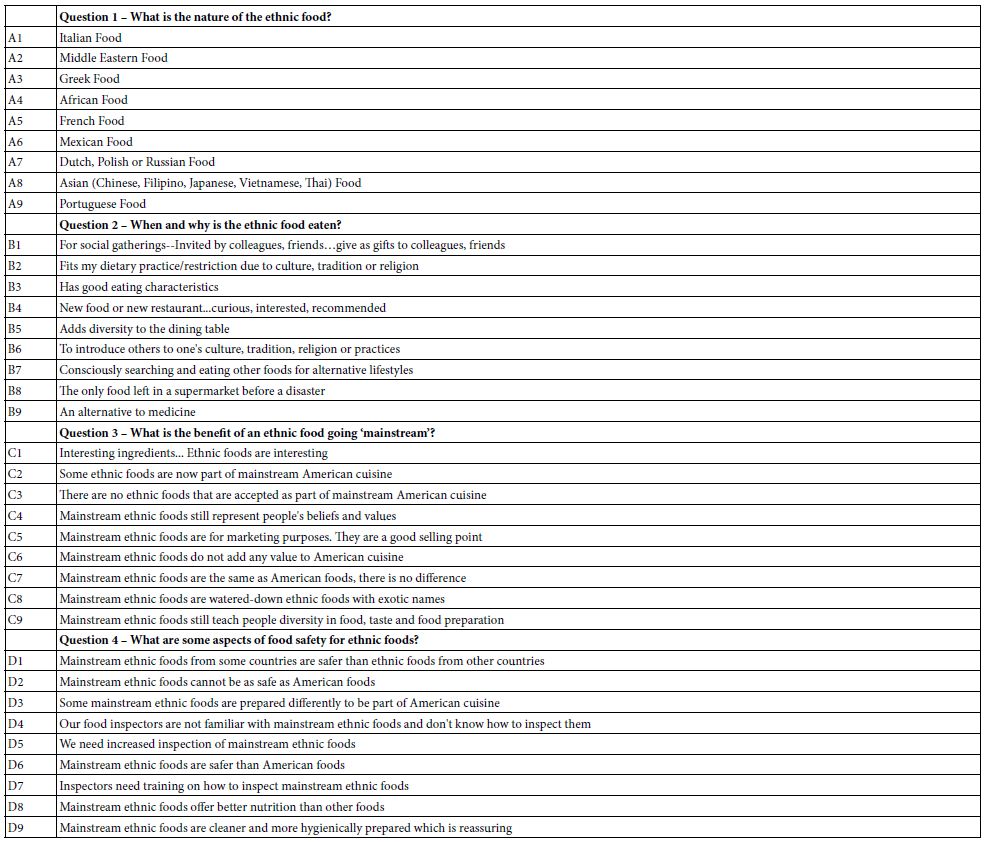

The draft framework was then taken through translational, face and content validity testing [12], using local community experts. Then it was tested for construct validity and reliability. Construct Validity was undertaken as described by Cronbach & Meehl [13], Brink & Wood [14], and Polit & Beck [15]. The effectiveness of the framework was assessed to establish the degree to which test scores predicted repeatability when the framework is used [16]. Participants were presented with descriptions of the volunteer motives in a self-administered questionnaire. Volunteers were compared with non-volunteers to establish the association of the motives significantly more either with the volunteers or non-volunteers. The participants were asked to indicate their agreement with assessment statements on a 5 – point Likert scale (ranging from 1 being “strongly disagree” to 5 being “strongly agree”) in relation to the motives for CHVs volunteerism in the draft assessment framework. The assessment items explored responses to statements designed to assess motives for volunteering, by expressing the degree to which they agreed or disagreed with the assessment items as stated. In addition, participants completed a demographic questionnaire comprising gender, age, educational background, history of volunteerism, and occupation. Respondents were asked to complete the sentences about the reason people volunteer and indicate the degree of their agreement with each one (Table 1).

Table 1: Volunteer Assessment Framework (VAF).

|

Altruistic value (core)

|

Strongly Agree |

Agree |

undecided |

Disagree |

Strongly disagree

|

| It creates a better society |

|

|

|

|

|

| It translates deep held values into actions. |

|

|

|

|

|

| They think about the welfare of other people, |

|

|

|

|

|

| They feel empathy for others |

|

|

|

|

|

| They consider themselves to be people who get involved |

|

|

|

|

|

|

Material gain (core) |

|

|

|

|

|

| They benefit at times in terms of cash or kind |

|

|

|

|

|

| At times they are given materials that have remained after volunteering |

|

|

|

|

|

| Sometimes they are paid |

|

|

|

|

|

| Sometimes they are rewarded and they feel good |

|

|

|

|

|

| Volunteer benefits add to their wealth |

|

|

|

|

|

|

3. Esteem enhancement (additional for volunteers) |

|

|

|

|

|

| They want to instill pride in themselves |

|

|

|

|

|

| It makes them feel important |

|

|

|

|

|

| It makes them feel appreciated |

|

|

|

|

|

| It makes them feel recognized |

|

|

|

|

|

| No matter how bad one has been feeling, volunteering helps one to forget about it |

|

|

|

|

|

|

4. Career Development (additional for non-volunteers) |

|

|

|

|

|

| They want to learn job-related skills |

|

|

|

|

|

| Of the chance to gain new experience |

|

|

|

|

|

| It will help them get an opportunity at a place where they would like to work |

|

|

|

|

|

| It can help them get a job |

|

|

|

|

|

| Of personal growth |

|

|

|

|

|

|

5. Social adjustment (optional for non-volunteers) |

|

|

|

|

|

| It is an opportunity for relationships |

|

|

|

|

|

| People at job/school/church/group would approve of their volunteering. |

|

|

|

|

|

| People who are close to them would support them to volunteer |

|

|

|

|

|

| Their family members would encourage them to volunteer. |

|

|

|

|

|

| Of reciprocal interactions in community |

|

|

|

|

|

|

6. Development of understanding (optional) for non-volunteers |

|

|

|

|

|

| It satisfies their curiosity about other people and the problems that they face |

|

|

|

|

|

| Of the opportunity to make friends |

|

|

|

|

|

| Of opportunity to challenge themselves |

|

|

|

|

|

| Volunteerism allows them to test their existing skills and abilities. |

|

|

|

|

|

Relating Motives to Tasks Preferred

The last part of this study was to determine relationship between health tasks and motive constructs as an attempt to categorize volunteers according to the tasks they prefer. The motives were related to tasks preferred. This was to form a basis for linking the motives to certain task categories. The CHVs were presented with descriptions of 40 volunteer tasks and were asked to rank the tasks in order of preference for engaging in them. The questions asked participants to rank each of the volunteer tasks in order of his or her preference indicating “most preferred choice” “least preferred choice.” Then, participants were presented with descriptions of volunteer motives as well as descriptions of the tasks and were asked to evaluate the extent to which each task would satisfy each of the volunteer motives for himself or herself. Finally, the CHVs were asked to assess, on 1-5 Likert scale, the extent to which each of the 8 motives had been satisfied, giving examples of tasks that had contributed to their motives satisfaction. This was to confirm the appropriate tasks to be assigned to the volunteers through triangulation of information.

Data Analysis

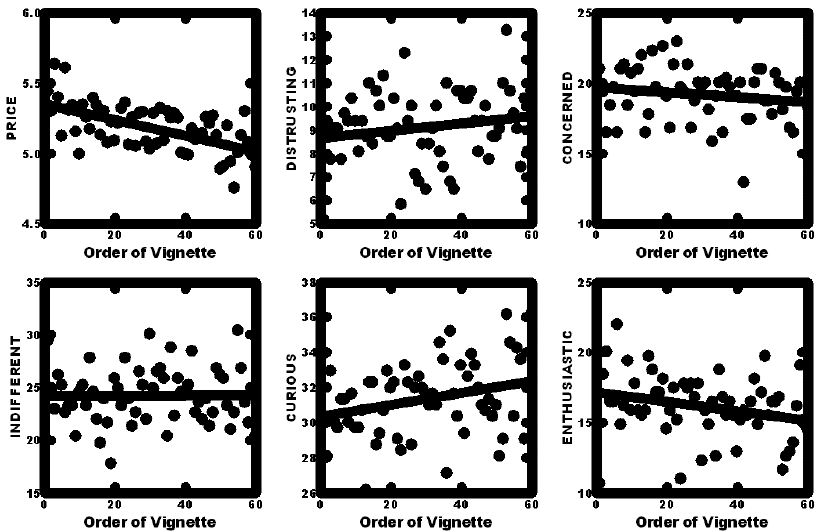

The data were analyzed using Scientific Package for Social Sciences (SPSS) Computer package version 16 and presented on frequency tables and graphs. Descriptive statistical analysis was undertaken with respect of demographic characteristics to compare the sampled volunteers and non-volunteers. The descriptive statistics also gave an impression as to the distribution of data as well as identification of values that could be seen as common. It also described the geographical distribution of the sample population [17].

Then the data were analyzed to find out the Cronbach’s alpha reliability coefficient value. The analysis of the data used the summated scales and subscales and not individual items. The results were calculated based upon the formula Cronbach’s alpha reliability coefficient = rk/[1 + (k -1)r] where k is the number of items considered and r is the mean of the inter-item correlations. Cronbach’s alpha reliability coefficient normally ranges between 0 and 1. The closer Cronbach’s alpha coefficient is to1.0 the greater the internal consistency of the items in the scale. The size of alpha is determined by both the number of items in the scale and the mean inter-item correlations. [18] provide the following rules of thumb: “_ >.9 – Excellent, _ >.8 – Good, _ >.7 – Acceptable, _ >.6 – Questionable, _ >.5 – Poor, and_ <.5 – Unacceptable. An alpha of 0.8 is a reasonable goal. A high value for Cronbach’s alpha indicates good internal consistency of the items in the scale.

For the assessment of validity and reliability of the framework the study used exploratory factor analysis, Cronbach’s coefficient alpha [19], to test the internal validity and reliability of the questionnaire derived from the framework. This was to assess the psychometric properties of the measures and thus compare CHVs and non-CHVs’ motives. Construct validity is the degree to which an instrument measures the construct it is intended to measure [13]. Cronbach’s alpha is an index of reliability associated with the variation accounted for by the true score of the underlying construct [19]. It was used to establish the internal consistency of the framework. This is important as it determines whether the instrument will always elicit consistent and reliable response even if questions were replaced with other similar questions. A variable is said to be reliable when responses generated from such a set of questions are stable. Reliability or internal consistency indicates how well the items on a framework fit together conceptually. The internal consistency test was undertaken using the Cronbach’s alpha coefficient test, as described by [14,15]. It is supported if the instrument’s items are related to its operationally defined theory and concepts.

The developed instrument was intended to measure volunteers’ motives and would be valid based on items in the framework having the capability to exclusively measure concepts that were theoretically and structurally related to volunteer motives. This was assessed by equivalence reliability test which uses the Cronbach’s alpha coefficient test. Construct was the hypothetical variable that was being measured [20]. The framework reliability was assessed, by demonstrating that there were volunteer constructs that were more associated with CHVs than non-CHVs. Reliability pertains to evidence of repeatability in identifying attributes in a measurement both in time as well as by other researchers.

Then, association of the constructs and measurement items with the volunteer status was tested using cluster analysis. Cluster analysis classifies a set of observations into two or more mutually exclusive unknown groups based on combinations of interval variables. The purpose of cluster analysis was to use a system of organizing observations into groups, where members of the groups share properties in common. It is cognitively easier for people to predict behavior or properties of people or objects based on group membership, all of whom share similar properties. By clustering the responses into agree (4, 5), undecided (3) and disagree (1, 2) and cross tabulating against the proportions among volunteer and non-volunteers the researcher was able to compare the proportions in the different clusters for each of the constructs and assessment items. The procedure tabulates a variable into categories and computes a chi-square statistic (χ2), degrees of freedom (df) and significance values (p). This goodness-of-fit test compares the observed and expected frequencies in each group to test whether the proportion of respondents are the same. In this study, the Chi-Square test was used to examine the relation between constructs and assessment items and volunteers or non-volunteers in the sample population.

This test was repeated by comparing the mean scores on the Likert scales among cases, volunteers, and controls, non-volunteers. The responses on volunteers’ motives were thus validated by correlations with construct measures, to establish their reliability in the local context. Mean scores by volunteer motives were calculated, compared and statistical significance of difference tested by t test. Association of constructs and measurement items was examined by comparing the mean scores among volunteers with those among non-volunteers. Using t test the constructs and measurement items that showed statistically different mean scores were identified for inclusion.

The results of the three tests, Cronbach’s alpha, cluster analysis, and comparison of means, enabled the researcher to select the best constructs and assessment items to include in the volunteer assessment framework for identification of volunteer health workers in the local context. The constructs and assessment items that showed statistically different scores between volunteers and non- volunteers, were considered suitable for inclusion in the final volunteer assessment framework. A p value <0.05 was considered statistically significant.

Results

Elements in a Volunteer Assessment Framework for CHVs

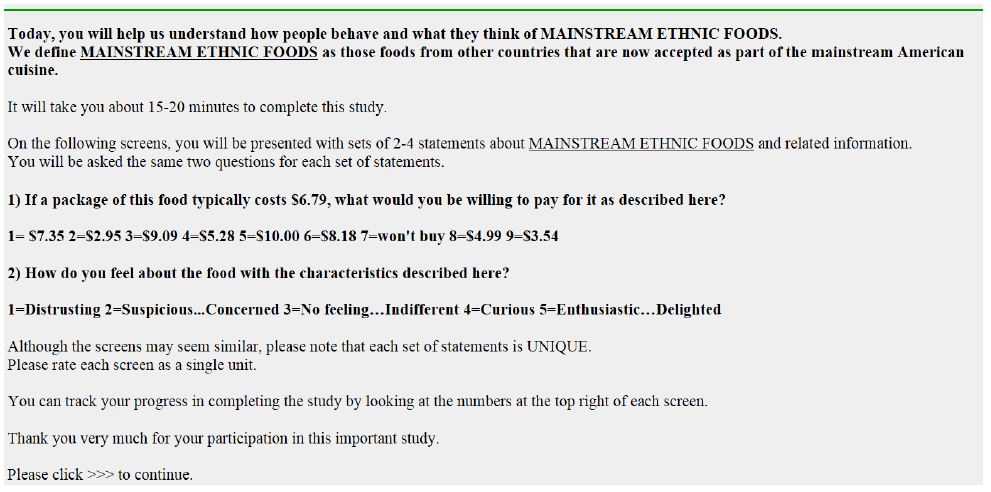

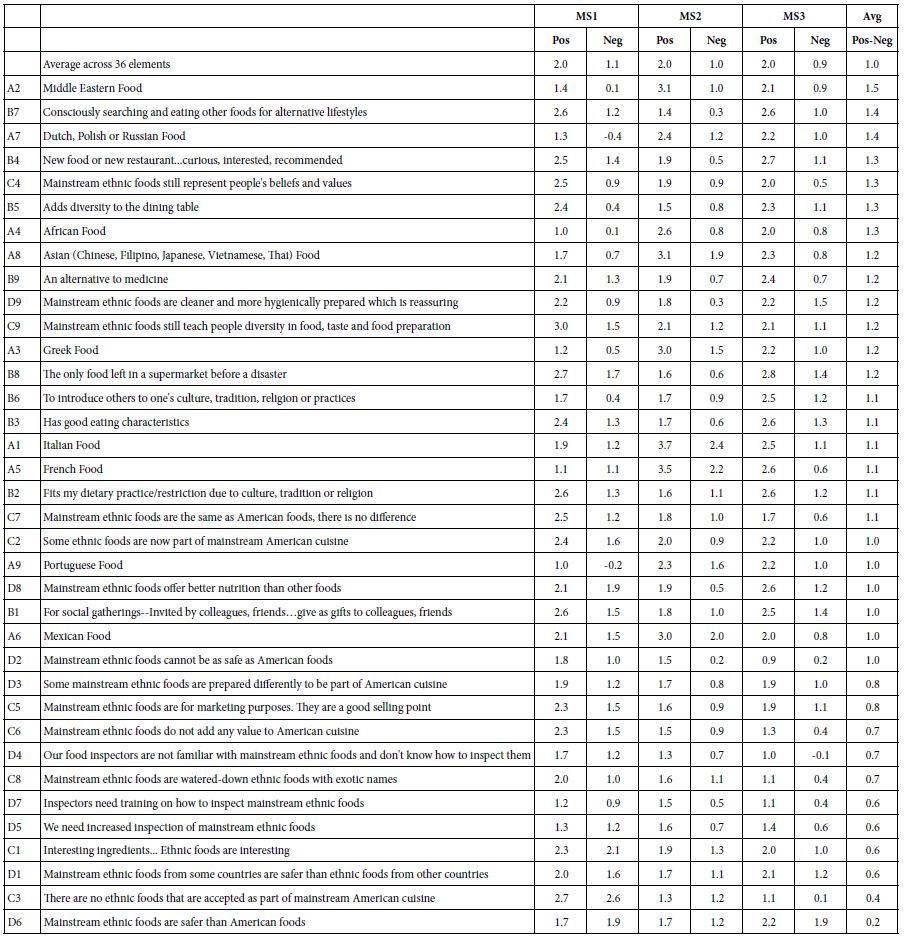

We identified three theories from literature underpinning motives identified: Social exchange theory which underpins egoistic motives, Functional theory underpins the altruistic motives and Role identity theory and underpins the Social motive constructs. Eight motive constructs were identified were from literature (Table 2). Eight categories of motive constructs with 86 assessment items were identified from literature (Table 1). The motives were: Altruism is the motive “to help others”, described by [21,22]. Community Concern motive is having a sense of obligation to the communities [23] and Spirituality motive is expression of faith [24-26].

Table 2: Motives to assess volunteer types by theory and source.

|

Theories

|

Motives |

Sources |

Remarks

|

| Functional theory |

Altruistic values |

Fitch, 1987, Omoto and Snyder (1995), Calary et al 1994 |

Intrinsic intangible rewards, humanitarian |

| Community concern |

Omoto and Snyder (1995), Clary et al (1994), Clary et al (1998) |

Caring for wellbeing of neighbor |

| Spirituality |

Ochieng B.M (2012) |

Religious motivation |

| Social exchange |

Material gain |

Fitch, 1987, Snyder (1995), Clary et al 1994, Henderson 1980, Caldwell and Andereck (1994) |

Tangible rewards, Imbalance between contribution and reward leads to discontinuation |

| Personal, career development |

Omoto and Snyder (1995), Clary et al 1994 |

Career, resume’, growth, learn skills, job opportunity |

| Role identity |

Social adjustment |

Morrow-Howell and Mui (1989), Henderson 1981, Clary et al (1998), (Moen 1995), (Greenfield 2010), (Utz 2002), (Li 2007). |

Satisfactions from interpersonal interactions, identity, make friends, accumulation of social roles, leads to wellbeing |

| Esteem enhancement, Ego Protection, |

Omoto and Snyder 2002, Clary et al (1998), (Stets 2000), Stevens 1995, (Morrow-Howell 2009), (MacNeela 2008), (Hinterlong 2006). |

Deal with guilt of success, self confidence, need to be productive and maintain meaning |

| Understanding, Knowledge |

Omoto and Snyder (1995), Clary et al (1998), Caldwell and Andereck (1994) |

Satisfy intellectual curiosity |

Social adjustment motive is seeking to respond to social pressure [27] and to the expectations of others [28-30]. Development of Understanding motive is seeking opportunity to understand, practice, and apply skills and abilities [31,32] and Ego-defensive or esteem enhancement motive is the need to enhance self-esteem, self-confidence.

Material gain motive is hope for material incentives. Career development motive is seeking to increase one’s job prospects and enhance one’s career [33], the desire for personal growth and learning of new skills [34,35].

The roles and tasks of CHVs to be used for assessing task preference were also identified and how to assess their relationship to volunteer motives.

Motive Constructs with Adequate Validity and Reliability among CHV in Western Kenya

The results of Construct Validity test showed that six out of the eight constructs in the tool were adequately valid in the local context, and suitable in Western Kenyan in identifying individuals likely to serve as long term health volunteers. These were:

Altruistic Values

Although the statements from literature were 12, only 5 of these were found to resonate with the respondents. This construct appeared to be among the most powerful predictors of long term volunteerism since it was the least egoistic in the local context. The long term CHVs scored the assessment items under this construct highly.

Material Gain

This construct was consistently, scored highly by non-volunteers and low by long serving CHVs. All the assessment items were equally strongly associated with non-volunteers than volunteers.

Career Development

This construct was scored moderately strongly by both CHVs non-volunteers than CHVs, there was no statistically significant difference in the scores, but young volunteers tended to score it highly. All the assessment items were significantly associated with non-volunteers than controls, and any could be used in the final tool.

Social Adjustment

Similarly this construct was scored moderately by both volunteers and non-volunteers were not statistically significantly different. Only two assessment items were identifiable more with volunteers as compared to non-volunteers.

Esteem Enhancement

All the assessment items under this construct were significantly associated more with long serving volunteers, scoring them more highly than the controls.

Development of Understanding

This motive was not scored by the respondents in a consistent way. Not all the assessment items were significantly associated more with long serving volunteers than with the controls except “opportunity for self-growth”.

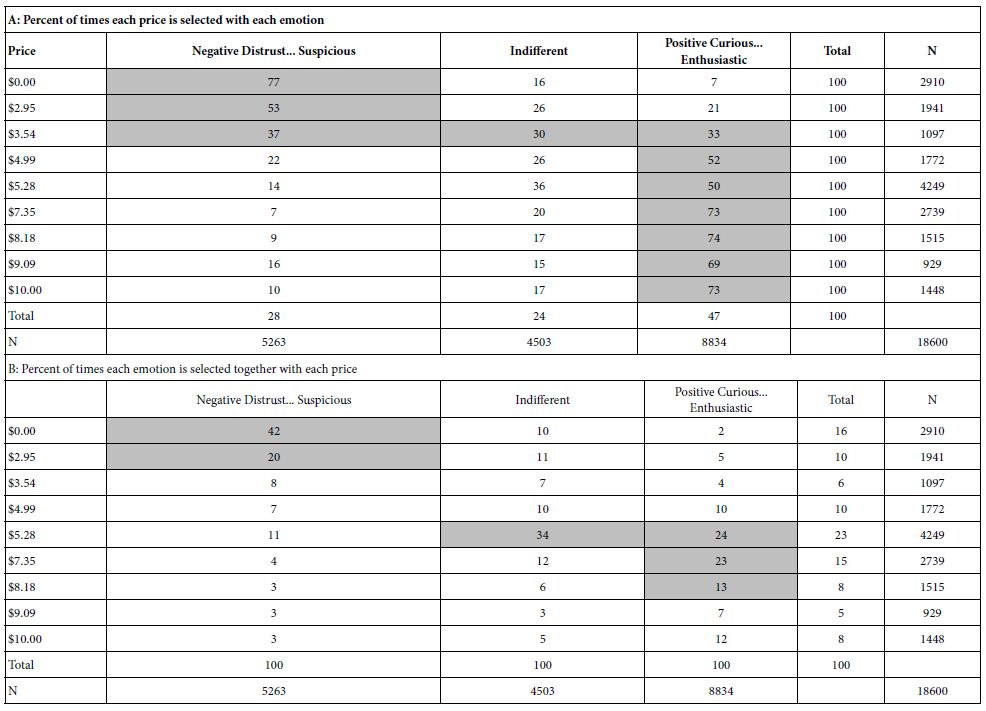

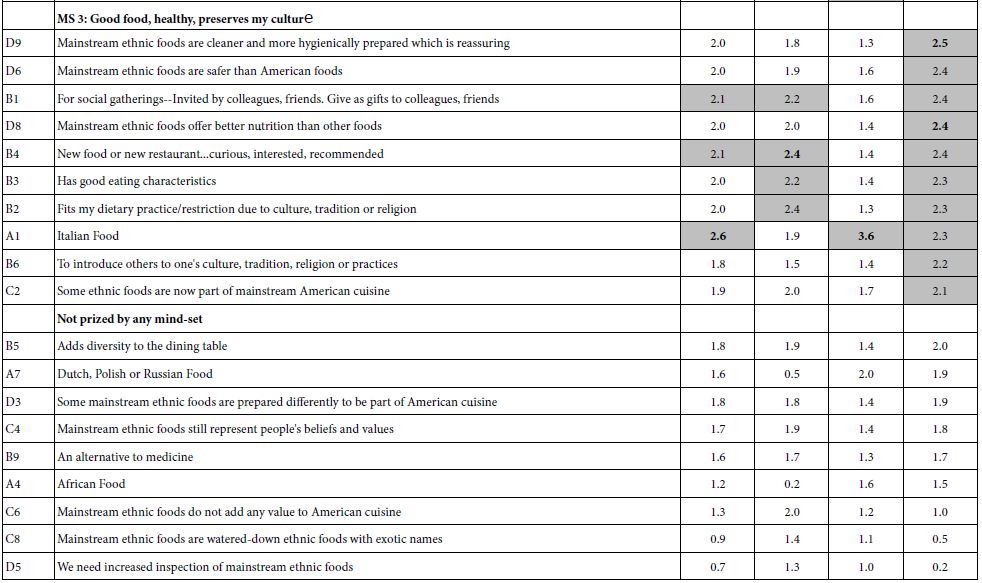

The association of constructs and assessment items with health volunteers and non-volunteers was examined by comparing mean scores. A statistical t-test was performed to determine the level of statistical significant difference in all the items in the constructs. The findings are summarized in table 2. Results showed three groups of motive constructs in terms of association with volunteers or non-volunteers. Those that demonstrated strongest associations were altruistic (with volunteers) and material gain (with non-volunteers); those that demonstrated weak association with either, community concern (with volunteers), development of understanding, esteem enhancement, and social adjustment (with non-volunteers); and those that were associated with neither volunteers nor non-volunteers were spirituality and career development (Tables 2 and 3).

Table 3: Comparison of mean scores by motives and volunteer status.

|

Volunteer Motives

|

subjects participants |

N |

Mean |

Std. Deviation |

T- test |

Criteria

|

| Altruistic value |

cases |

531

|

63.05 |

9.77 |

.000

|

Significant |

| controls |

531

|

60.15 |

11.57

|

|

|

| Career development |

cases |

531

|

25.92 |

5.47 |

.207

|

Not significant |

| controls |

531

|

25.83 |

5.97

|

|

|

| Development of understanding |

cases |

531

|

43.36 |

10.12 |

.002

|

Significant |

| controls |

531

|

44.09 |

11.72

|

|

|

| Esteem enhancement |

cases |

531

|

15.67 |

6.35 |

.255

|

Not significant |

| controls |

531

|

17.11 |

6.57

|

|

|

| Community Concern |

cases |

531

|

30.02 |

6.41 |

.006

|

Significant |

| controls |

531

|

29.13 |

7.22

|

|

|

| Social adjustment |

cases |

531

|

18.92 |

7.14 |

.001

|

Significant |

| controls |

531

|

20.29 |

7.81

|

|

|

| Material gain |

cases |

531

|

12.95 |

7.24 |

.000

|

Significant |

| controls |

531

|

16.09 |

8.03

|

|

|

| Spirituality |

cases |

531

|

20.91 |

4.99 |

.023

|

Significant |

| controls |

531

|

20.40 |

5.77

|

|

|

Comparing the conclusions from the two tests, an interesting pattern emerged. Altruistic and materialistic values were strongly associated only with volunteers and non-volunteers respectively, by both tests, and therefore the best constructs to use in the local context. While four, mostly social constructs, poorly differentiated between volunteers and non-volunteers, but could prove useful for inclusion depending on the objectives of the program for which volunteers are sought. These were social adjustment, esteem enhancement, development of understanding and career development. Thus the findings suggested two core constructs, and four additional constructs with twenty-nine assessment items that could be applied to the framework, for the local setting. Spirituality and community concern did not differentiate between volunteers and non-volunteers by both tests and therefore were unsuitable for the framework being tested (Table 4).

Table 4: Final Volunteer Assessment Framework (VAF): Complete the following sentences about the reason people volunteer and indicate the degree of your agreement with each one.

|

Altruistic value (core)

|

Strongly Agree |

Agree |

undecided |

Disagree |

Strongly disagree

|

| It creates a better society |

|

|

|

|

|

| It translates deep held values into actions. |

|

|

|

|

|

| They think about the welfare of other people, |

|

|

|

|

|

| They feel empathy for others |

|

|

|

|

|

| They consider themselves to be people who get involved |

|

|

|

|

|

|

Material gain (core) |

|

|

|

|

|

| They benefit at times in terms of cash or kind |

|

|

|

|

|

| At times they are given materials that have remained after volunteering |

|

|

|

|

|

| Sometimes they are paid |

|

|

|

|

|

| Sometimes they are rewarded and they feel good |

|

|

|

|

|

| Volunteer benefits add to their wealth |

|

|

|

|

|

|

OPTIONAL CONSTRUCT MOTIVES |

| 3. Esteem enhancement (additional for volunteers) |

|

|

|

|

|

| They want to instill pride in themselves |

|

|

|

|

|

| It makes them feel important |

|

|

|

|

|

| It makes them feel appreciated |

|

|

|

|

|

| It makes them feel recognized |

|

|

|

|

|

| No matter how bad one has been feeling, volunteering helps one to forget about it |

|

|

|

|

|

| 4. Career Development (additional for non-volunteers) |

|

|

|

|

|

| They want to learn job-related skills |

|

|

|

|

|

| Of the chance to gain new experience |

|

|

|

|

|

| It will help them get an opportunity at a place where they would like to work |

|

|

|

|

|

| It can help them get a job |

|

|

|

|

|

| Of personal growth |

|

|

|

|

|

|

5. Social adjustment (optional for non-volunteers) |

|

|

|

|

|

| It is an opportunity for relationships |

|

|

|

|

|

| People at job/school/church/group would approve of their volunteering. |

|

|

|

|

|

| People who are close to them would support them to volunteer |

|

|

|

|

|

| Their family members would encourage them to volunteer. |

|

|

|

|

|

| Of reciprocal interactions in community |

|

|

|

|

|

|

6. Development of understanding (optional) for non-volunteers |

|

|

|

|

|

| It satisfies their curiosity about other people and the problems that they face |

|

|

|

|

|

| Of the opportunity to make friends |

|

|

|

|

|

| Of opportunity to challenge themselves |

|

|

|

|

|

| Volunteerism allows them to test their existing skills and abilities. |

|

|

|

|

|

Relating Motive Constructs with Preferred Tasks

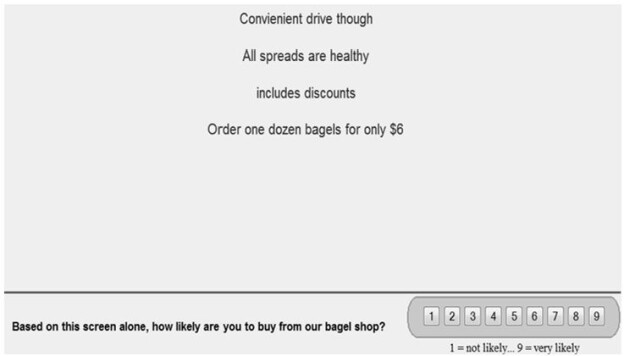

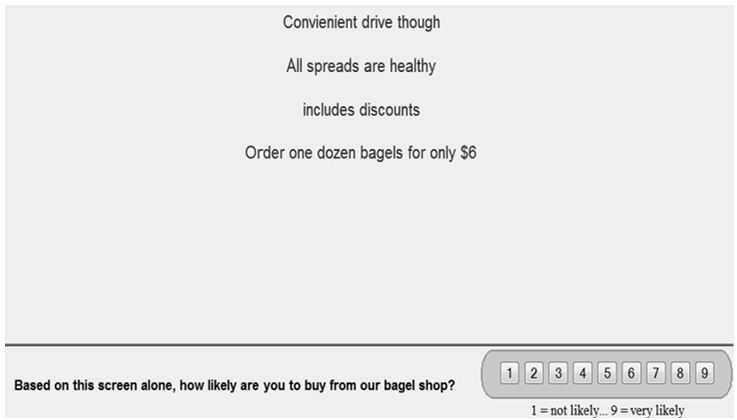

Tasks investigated were associated more with volunteers than non-volunteers based on the mean scores. The findings identified three categories of tasks: the typical long-term health tasks, preferred more by long serving health volunteers; long term participation tasks preferred by both volunteers and non-volunteers and tasks that were either short term or emergency in nature, requiring urgent response for relatively short periods (Table 3).

Long Term Health Tasks Preferred More by Long Serving Health Volunteers

Altruistic motive was strongly associated with most tasks investigated. Only family planning and community based health information system were not strongly preferred by respondents with altruistic motive. Career enhancement was associated with the care of orphaned and vulnerable children. Tasks investigated were associated more with volunteers than non-volunteers based on the mean scores.

Long Term Participation Tasks Preferred by Both Volunteers and Non-volunteers

The rest of the motives were not adequately associated with tasks. Social motives demonstrated some relationship with tasks such as attending meetings and dialogue sessions. Esteem enhancement was associated with mother and child health, and household visits for health education.

Short Term Emergency or Curative Tasks Preferred by Both Volunteers and Non-volunteers

The non-volunteers showed greater association with materialistic tasks than the volunteers themselves. These were tasks requiring urgent response for relatively short periods, tended to be associated with material gain which was not significantly associated with the majority of the tasks investigated, except curative care. Similarly, development of understanding was associated only with curative care tasks (Tables 5a-5c).

Table 5a: Task Preference by volunteers and Non-volunteers.

|

Cases

Controls

|

n-531

n-531 |

Least preferred n(%) |

Undecided

n(%) |

Preferred

n(%) |

P Value

|

| Visiting Pregnant women and Counseling them on Individual Birth Plan (IBP) and referring them for Ante Natal Care (ANC) |

Cases |

0(0.0)

|

39(3.7) |

491(46.3) |

0.00

|

| Controls |

3(0.3)

|

406(38.3) |

121(11.4)

|

| Carrying out repeat home visiting if pregnant women to discuss readiness for delivery |

Cases |

3(0.3)

|

48(4.5) |

479(45.2) |

0.00

|

| Controls |

3(0.3)

|

408(38.5) |

119(11.2)

|

| Mothers with Newborns visited soon after delivery and Counseled on Exclusive Breast Feeding( EBF) |

Cases |

5(0.5)

|

44(4.2) |

481(45.3) |

0.00

|

| Controls |

4(0.5)

|

408(38.5) |

118(11.2)

|

| Home deliveries visited and referred for Post Natal Care(PNC ) |

Cases |

5(0.5)

|

38(3.6) |

487(45.9) |

0.00

|

| Controls |

2(0.2)

|

407(38.4) |

121(11.4)

|

| Referring Children <1 years to clinic for Immunizations |

Cases |

4(0.4)

|

38(3.6) |

488(46) |

0.00

|

| Controls |

2(0.2)

|

406(38.3) |

123(11.6)

|

| Following up and referring Immunizations defaulters |

Cases |

2(0.2)

|

37(3.5) |

491(46.3) |

0.00

|

| Controls |

2(0.2)

|

406(38.3) |

122(11.5)

|

| Visiting Children <5 to monitor their health, growth and development |

Cases |

3(0.3)

|

41(3.9) |

486(45.9) |

0.00

|

| Controls |

2(0.2)

|

407(38.4) |

121(11.4)

|

| Referring <5 children who are ill for prompt treatment at Health Facility |

Cases |

5(0.5)

|

43(4.1) |

482(45.5) |

0.00

|

| Controls |

4(0.4)

|

406(38.3) |

120(11.3)

|

| Referring Children <5 years for Vitamin A and growth monitoring |

Cases |

9(0.9)

|

46(4.4) |

475(44.9) |

0.00

|

| Controls |

4(0.4)

|

407(38.4) |

119(11.2)

|

| Assessing Children < 5 nutrition status using Mid Upper Arm Circumference (MUAC ) |

Cases |

59(5.6)

|

49(4.6) |

422(39.8) |

0.00

|

| Controls |

8(0.8)

|

412(38.9) |

110(10.4)

|

| Referring Children <5 with malnutrition |

Cases |

21(2.0)

|

50(4.7) |

459(43.3)

|

0.00

|

| Controls |

6(0.6)

|

411(38.8) |

113(10.6)

|

| Referring Orphans and Vulnerable Children( OVCs) for care and support |

Cases |

44(4.1)

|

29(2.7) |

457(43.1) |

0.00

|

| Controls |

31(3)

|

91(8.5) |

408(38.5)

|

| Supplying clients with Family Planning( FP) commodities |

Cases |

132(12.4)

|

60(5.7) |

338(31.9) |

0.00

|

| Controls |

23(2.2)

|

414(39.1) |

93(8.8)

|

| Identifying and referring Cases of chronic cough |

Cases |

13(1.2)

|

42(4.0) |

475(44.8) |

0.00

|

Table 5b: Task Preference by volunteers and Non-volunteers.

|

Cases

Controls

|

n-531

n-531 |

Least preferred n(%) |

Undecided

n(%) |

Preferred

n(%) |

P Value

|

|

Controls |

8(0.8)

|

413(39) |

109(10.3)

|

|

| Tracing and referring AIDS treatment defaulters |

Cases |

21(2.0)

|

49(4.7) |

460(43.4) |

0.00

|

| Controls |

8(0.8)

|

416(39.3) |

106(10.0)

|

| Referring people for Home Counseling and treatment (HCT) |

Cases |

72(6.7)

|

53(5.0) |

405(38.2) |

0.00

|

| Controls |

13(1.2)

|

415(39.2) |

102(8.6)

|

| Identifying and managing Cases of fever and diarrhea |

Cases |

38(3.5)

|

53(5.0) |

439(41.4) |

0.00

|

| Controls |

10(1.0)

|

413(39) |

107(10.1)

|

| Providing Cases with painkillers, Managing injuries and wounds |

Cases |

103(17.8)

|

67(6.4) |

360(34) |

0.00

|

| Controls |

22(1.1)

|

84(7.9) |

424(40)

|

| Referring Elderly people for check – ups |

Cases |

69(6.5)

|

53(5.0) |

408(38.5) |

0.00

|

| Controls |

10(1.0)

|

414(39.1) |

106(10.0)

|

| Households visited for health education |

Cases |

5(0.5)

|

45(4.3) |

480(45.3) |

0.00

|

| Controls |

0(0.0)

|

408(38.5) |

132(11.5)

|

| Holding Meetings With CHEWs |

Cases |

6(0.6)

|

22(2.1) |

502(47.3) |

0.00

|

| Controls |

31(3.0)

|

95(8.9) |

404(38.1)

|

| Holding Dialogue meetings with community |

Cases |

7(0.7)

|

16(1.5) |

507(47.8) |

0.00

|

| Controls |

22(2.1)

|

84(7.9) |

424(400)

|

| Conducting Community Action Days |

Cases |

20(1.8)

|

17(1.6) |

493(46.5) |

0.00

|

| Controls |

24(2.3)

|

98(9.2) |

408(38.5)

|

| Organizing immunization campaigns |

Cases |

31(2.9)

|

26(2.4) |

473(44.6) |

0.00

|

| Controls |

34(3.3)

|

107(10) |

389(36.7)

|

| Participating in indoor spraying against malaria |

Cases |

55(5.2)

|

37(3.5) |

438(41.3) |

0.00

|

| Controls |

47(4.4)

|

114(10.7) |

369(34.8)

|

| Participating in food distribution during disasters |

Cases |

76(7.2)

|

47(4.4) |

407(38.4) |

0.00

|

| Controls |

54(5.1)

|

103(9.7) |

373(35.2)

|

| Treating water during cholera outbreaks |

Cases |

40(3.8)

|

30(2.8) |

460(43.2) |

0.00

|

| Controls |

36(3.3)

|

103(9.7) |

373(35.2)

|

Table 5c: Task Preference by volunteers and Non-volunteers.

|

Cases

Controls

|

n-531

n-531 |

Least preferred n (%) |

Undecided

n(%) |

Preferred

n(%) |

P Value

|

| Managing cholera cases during cholera outbreaks |

Cases |

55(5.2)

|

57(5.4) |

418(39.5) |

0.00

|

| Controls |

11(1.1)

|

412(38.9) |

107(10.1)

|

| Giving health education during outbreaks |

Cases |

16(1.5)

|

27(2.5) |

487(46) |

0.00

|

| Controls |

32(3.0)

|

108(10.2) |

390(36.8)

|

| Cleaning of the health facilities |

Cases |

31(3.0)

|

59(5.5) |

440(41.5) |

0.00

|

| Controls |

32(3.0)

|

108(10.2) |

390(36.8)

|

| Distribution of ITNs |

Cases |

26(2.4)

|

25(2.4) |

479(45.2) |

0.00

|

| Controls |

47(4.4)

|

113(10.7) |

370(34.9)

|

| Distribution of water guard |

Cases |

31(3.0)

|

32(3.5) |

467(44) |

0.00

|

| Controls |

31(3.0)

|

119(11.3) |

380(35.8)

|

| House H old registration and updates |

Cases |

25(2.3)

|

32(3.0) |

473(44.7) |

0.00

|

| Controls |

39(3.6)

|

149(14.0) |

342(22.3)

|

| Data analysis |

Cases |

58(5.4)

|

38(3.5) |

434(41) |

0.00

|

| Controls |

48(4.5)

|

148(14.0) |

333(35.5)

|

| Helping in emergencies (accidents victims ) |

Cases |

58(5.5)

|

46(4.3) |

426(40.2) |

0.00

|

| Controls |

34(3.2)

|

155(14.6) |

341(32.2)

|

| Helping in emergencies (house on fire ) |

Cases |

61(5.8)

|

47(4.4) |

422(39.9) |

0.00

|

| Controls |

29(2.7)

|

139(13.1) |

362(34.2)

|

| Helping in emergencies(flood victims) |

Cases |

84(8.0)

|

61(5.7) |

385(36.3) |

0.00

|

| Controls |

32(3.0)

|

141(13.3) |

357(33.7)

|

| Food distribution during famine |

Cases |

99(9.3)

|

64(6.0) |

367(34.6) |

0.00

|

| Controls |

49(4.6)

|

152(14.4) |

329(31)

|

| Vaccination of livestock/poultry campaign |

Cases |

85(7.7)

|

56(5.3) |

389(36.7) |

0.00

|

| Controls |

75(7.0)

|

183(17.2) |

271(25.7)

|

Discussion

Elements of the CHV Assessment Framework

The results of Construct Validity test showed that all the constructs in the tool were adequately valid in the local context. The constructs suited the Western Kenyan context in identification of individuals likely to serve as long term health volunteers. Literature provided theories, motives and assessment items that were used to develop a volunteer assessment framework for recruitment of CHVs, so that their motives for volunteering are known from the beginning to guide their training and management. This would improve the cost-efficiency of CHV programs. The main premise was that while different people can perform the same actions, the actions serve different psychological functions for different individuals [36-48].

The eight motive constructs identified were in three categories first suggested by Morrow-Howell and Mui in [49]. (1) Altruistic, (2) Material and (3) Social, grounded on three theories, Functional theory, Clary and Snyder underpins the altruistic motive constructs, Social exchange theory [50,51] and Role identity theory [52] which underpins the Social motive constructs [53-65].

Functional Theory

Penner [66] suggests that functional approach explained the processes that underlie long-term volunteering. Omoto and Snyder found that satisfaction with the volunteer experience was related to longevity of service, and Clary and colleagues found a positive association between satisfaction and intentions to continue volunteering [67]. Similarly, Penner and Finkelstein reported that satisfaction correlated significantly with both length of service and time spent volunteering [68], hence greater understanding of retention issues. These elements were based on Functional Analysis of motives based on this theory classified under Altruistic values.

Altruistic Values are based on deeply held beliefs of the importance of helping others, suggesting motivation processes that underlie long-term volunteering, such as is required for Community Health Volunteers. This construct was the most powerful predictor of long-term volunteerism, being least egoistic. This finding is consistent with research undertaken on volunteer motivation [66]. A person with altruistic value tends to think about the welfare of other people, to feel empathy for them, and to act in a way that benefits them. Volunteering for a worthy cause provides people with an opportunity to express their humanitarian concerns and translates their deeply held values into actions. Researchers have demonstrated that intention to volunteer was positively related to altruistic values [69,70].

Social Exchange Theory

The social exchange theory underlined the importance of matching volunteer motivations to the benefits that volunteerism provides, noting that matching benefits with personal motivations resulted in positive volunteer outcomes. Clary et al. found that students with matching benefits were more satisfied with their volunteerism experience and had greater intentions to continue volunteering. Material gain motives, and career development, were consistent with social exchange theory [71]. In this study the material gain values emerged as one of the core motive constructs.

Role Identity Theory

According to this perspective, one’s self-concept consisted of a hierarchy of social-role identities that guide behavior [72]. The more others identified one with a particular role, the more the individual internalized the role and incorporated it into the self-concept. Additionally, according to [72], carrying out the role of a volunteer not only shaped how an individual’s viewed themselves, but it also drove future behavior as individuals strove to make their behavior consistent with the volunteer-role identity. In regard to role identity theory, the concept of “self” had a direct causal effect on volunteer activity. Specifically, continued volunteering leads to the development of a volunteer role identity that drives continued volunteer actions. Social (social adjustment, esteem enhancement, development of understanding) were consistent with role identity theory [71] while the social constructs poorly differentiated between volunteers and non-volunteers.

Role identity theory proposed that women were more likely to adopt multiple roles and that maintaining some of these throughout life was important for well-being. Research also suggested that as men and women age they constructed new gender identities which relied less on traditional stereotypes (Silver 2003). In this study, these benefits were explored, utilizing role identity theory to examine how volunteering could be a positive activity for CHVs, since role identities were important throughout life, and that these roles gave life meaning.

Validity and Reliability of Motive Constructs among CHV in Western Kenya

The effectiveness of the framework was assessed to establish the degree to which test scores predicted repeatability when the tool was used (Shultz & Whitney, 2005). Two of the constructs were consistently strongly associated either with volunteers or non-volunteers. These were altruistic value and material gain, respectively. Four additional constructs did not demonstrate strong association with volunteers but could prove useful for inclusion depending on the objectives of the program for which volunteers are sought. These were social adjustment, esteem enhancement, development of understanding and career development. This was consistent with the classification by Morrow-Howell and Mui (1989), (1) Altruistic, (2) Material, and (3) Social. In this study the altruistic and material were the core constructs while the rest, mostly social constructs poorly differentiated between volunteers and non-volunteers. Thus the findings suggested two core constructs, and four additional constructs with twenty-nine assessment items that could be applied to the framework, for the local setting.

This study provided valuable information about the actual motives and their relative importance to identify volunteers likely to serve long as needed in community-based health care. Altruistic and material values emerged as the core motive constructs most useful in identifying volunteers, positively or negatively while the social constructs poorly differentiated between volunteers and non-volunteers. Career development and esteem enhancement motives showed relative relevance within the prevailing socio-cultural context but social adjustment and development of understanding motives had inconsistent association with volunteers and non-volunteers.

Altruistic Values are deeply held beliefs of the importance of helping others, (Clary, Snyder & Ridge, 1992, Penner 2002) suggesting motivation processes that underlie long-term volunteering, such as is required for Community Health Volunteers, being least egoistic. This finding is consistent with research undertaken on volunteer motivation (Penner 2002).

Material Gain was the construct describing individuals who volunteered in order to benefit in terms of cash, kind or some other tangible way. It was strongly associated with non-volunteers in this study. This finding was consistent with many other social theories underlying reasons for people to take action because they weigh investment against benefits, [73]. The assessment items would exclude candidates not interested in long term volunteering since they perceived volunteering as a productive activity (Warburton 2006). Career Development constructs identify those who volunteer to enhance job opportunity. It was not always strong in association with non-volunteers as should have been expected. This implies that both volunteers and non-volunteers desire a career, and could consider volunteering with this at the back of their mind. Given the young age of volunteers and their level of education, individuals with this motive could be considered suitable when there are career prospects in the volunteer program, which is a possibility for community based volunteers [74].

Social Adjustment statements were appreciated by volunteers who perceived volunteering as useful not only intrinsically, but in the eyes of others (Finkelstein 2009) such as esteem enhancement constructs in which volunteerism serves to enhance self-esteem, and self-confidence as observed by [75-77]. All the assessment items were significantly associated with non-volunteers than controls. The construct could be particularly useful in recruiting retired older volunteers, expected to be sensitive about self-esteem. The third construct under social, development of understanding, did not seem to resonate with respondents in this study.

The importance of identifying altruistic and egoistic motives for volunteering had been described by many researchers [78,79]. This supports the clustering of the constructs according to how altruistic or egoistic ending up with the final constructs and assessment items. Social Adjustment construct was weak in identifying volunteers. The responses from volunteers and non-volunteers were not statistically significantly different. Only two assessment items were identifiable more with volunteers as compared to non-volunteers which are culturally supportable [26].

Researchers have described the importance of these differences in the recruitment, placement and retention of volunteers in community settings (Clary, Snyder & Ridge, 1992) [80-82] (Barbuto, Marx, Etling, & Burrow, 2000). However, this study contributes in demonstrating the superiority of altruistic constructs in identifying long serving volunteers and superiority of material constructs in identifying non-volunteers and the inferiority of the social constructs in the Western Kenyan context. The study contributes to a greater understanding of the underlying reasons why people volunteer in the local setting. Understanding these motivations is of great assistance to the managers of community based health care such as the Kenyan Ministry of Health. The importance of identifying altruistic and egoistic motives for volunteering had been described by many researchers (Fitch, 1987; Phillips 1982; Smith 1981), and supports the clustering of the constructs according to how altruistic or egoistic they are.

The core motive constructs identified in the final framework contribute to a greater understanding of the underlying reasons why people volunteer. Many of these motivations were consistent with those examined by Clary, Snyder (1998) and their colleagues. However this study adds the element of identifying the most powerful predictors of long term volunteers – altruistic value, material gain. They were the constructs in which the perceptions of volunteers and non-volunteers differed most significantly. Understanding these motivations is suggested by many authors to be of great assistance to the managers of volunteers in their recruitment, selection, placement and ultimate retention of volunteers (Clary, Snyder & Ridge, 1992), and thus contributes to strengthening the health system.

The study demonstrated that it is possible to classify tasks according to the motives they satisfy. The results suggest that maternal child health, curative care, household visits are in one class; community based information system, meetings and dialogue in another and emergency tasks are in a third cluster. This will help volunteer recruiters to align them to tasks with benefits that match their personal motives resulting in higher satisfaction and commitment to serve their community for long. Other workers have reported that when volunteering met the motives for helping, individuals reported greater satisfaction and stronger intentions to continue volunteering than they did when those motives remained unfulfilled, or irrelevant motives were satisfied (Clary & Snyder, 1999; Clary et al., 1998; Stukas, Daly, & Cowling, 2005). This study adds the specific categories relevant to health volunteers: long term health, long term developmental or participative and short term tasks required in disasters and emergencies. The importance of identifying altruistic and egoistic motives for volunteering had been described by many researchers (Fitch, 1987; Phillips 1982; Smith 1981). This supports the clustering of the constructs according to how altruistic or egoistic ending up with the final constructs and assessment items.

Relating Motives to Tasks of Volunteers

Matching motives with benefits has real consequences in motivating the volunteer, hence the importance of identifying preferred tasks in allocating tasks as observed by Snyder and colleagues (Snyder et al 2000). Different combinations of motives were associated with different tasks as observed by Clary et al. (1996). In this study people differentiated tasks based on the motives they satisfied. When given a choice, individuals preferred tasks with benefits that matched their personally relevant motives. [83] found that individuals chose volunteer tasks that they perceived would satisfy the motives that were most important to them. Researchers observe that people continue to volunteer to the extent that their experiences fulfill relevant motives [84] (Van Dyne & Farmer, 2005) Clary & Snyder, 1999; Clary et al., 1998; Stukas, Daly, & Cowling, 2005). Motive fulfillment also correlated with later volunteer activity (Omoto & Snyder, 1995).

The findings identified three categories of tasks: typical long-term health tasks, long term participation tasks and short term or emergency tasks, demonstrating that the framework could be used to classify volunteers by task preference and thus aid in efficient management of volunteer activities. The value of such a classification is supported by many researchers in this field (Clary & Snyder, 1999; Clary et al., 1998; Davis, Hall, and Meyer 2003; Stukas, Daly, & Cowling, 2005). Houle, Sagarin, and Kaplan (2005) add that people do differentiate tasks based on the volunteer motives they satisfy, and hence tasks can be classified in terms of the motive(s) it does or does not satisfy. The classification of tasks for volunteer assignment would contribute to the retention of community health volunteers [85], by placing them in tasks that community volunteers prefer. The core motive constructs, altruistic value and material gain can be used in the identification and allocation of tasks to health volunteers and one does not have to use all seven constructs, making the framework short and user friendly yet effective.

Altruistic motive was strongly associated with most tasks investigated. Individuals with altruistic value are the most suitable for voluntary work of all kinds, health, developmental, participatory, short term intermittent and emergencies. A study by Anderson and Moore (1978) supported the importance of this motive construct. In contrast material gain was not significantly associated with the majority of the tasks investigated, except curative care that could be considered materialistic. Career enhancement was associated with the care of orphaned and vulnerable children. Indeed, studies have shown that individuals experience greater learning and development when volunteering involves the acquisition and application of a variety of skills [86,87]. Social motives demonstrated some relationship with tasks of participation such as attending meetings and dialogue sessions. Esteem enhancement was associated with mother and child health, and household visits for health education, described by (Omoto and Snyder 1995). Development of understanding was associated only with curative care tasks. Research suggests that volunteering can provide a mastery experiences [88].

This study makes unique contribution on determinants of sustained involvement in volunteering, by providing a mechanism to classify volunteers allocate them to the tasks they prefer. The core motive constructs identified in the final framework contribute to a greater understanding of the underlying reasons why people volunteer, many being consistent with those examined by Clary, Snyder and their colleagues (Clary et al 1998), however this study adds the element of identifying the most powerful predictors of long term volunteers – altruistic value, material gain. They were the constructs in which the perceptions of volunteers and non-volunteers differed most significantly. Understanding these motivations can be of great assistance to the managers of volunteers in their recruitment, selection, placement and ultimate retention (Clary, Snyder & Ridge, 1992), and thus contributes to strengthening the health system. [89-95]

The study adds the dimension of using the motives to predetermine volunteers that are likely to last in order to determine their tasks and training and thus improve efficiency by targeting training in content and length according to realistic expectations of volunteers by categories so defined. It makes substantial contribution to justify the expectation of volunteerism even in poor settings. This will improve the cost-efficiency of CHV programs. Individuals can thus be matched with tasks they are likely to find the most rewarding (Houle, Sagarin, & Kaplan, 2005). In general it demonstrates that volunteering is good for all people. This is a significant contribution to the community health profession. Several scholars examined volunteer motives in rural community settings (Bajema, Miller & Williams, 2002 and Fritz, Barbuto, Marx, Etling, & Burrow, 2000). This study developed a comprehensive VAF tool that is flexible and usable in the Western Kenyan context for recruitment and task allocation of health volunteers, based on the type of volunteer required. It has 6 motive constructs and 29 assessment items.

Houle, Sagarin, and Kaplan (2005) found that individuals chose volunteer tasks that they perceived would satisfy the motives that were most important to them. Individuals can thus be matched with tasks they are likely to find the most rewarding. Omoto and Snyder found that satisfaction with the volunteer experience was related to longevity of service, and Clary and colleagues found a positive association between satisfaction and intentions to continue volunteering (Clary et al., 1998; Omoto & Snyder, 1995). They reported greater satisfaction and stronger intentions to continue volunteering than when motives remained unfulfilled, or irrelevant motives were satisfied (Clary & Snyder, 1999; Clary et al., 1998; Stukas, Daly, & Cowling, 2005). This study adds the specific categories relevant to health volunteers: long term health, long term developmental or participative and short term tasks required in disasters and emergencies. Similarly, Penner and Finkelstein reported that satisfaction correlated significantly with both length of service and time spent volunteering (Penner & Finkelstein, 1998), hence appropriate allocation of tasks would contribute to tenure and retention. People continue to volunteer to the extent that their experiences fulfill relevant motives (Davis, Hall, & Meyer, 2003; Van Dyne & Farmer, 2005).

The study demonstrated that it is possible to classify tasks according to the motives they satisfy. The results suggest that maternal child health, curative care, household visits are in one class; community based information system and meetings and emergency tasks are in a third cluster, a contribution that this study is making to new knowledge. This will help volunteer recruiters to align them to tasks with benefits that match their personal motives resulting in higher satisfaction and commitment to serve their community for long.

Conclusion

The resultant volunteer assessment framework consists of two core constructs, altruistic value and material gain. The two core constructs are effective in identifying the motives of those likely to volunteer long term (altruistic) and individuals unlikely to volunteer long term (material gain) in the Western Kenya context. They were the constructs in which the perceptions of volunteers and non-volunteers differed most significantly. This tool will be instrumental in the recruitment of appropriately motivated volunteers for long term assignment, and hence improve the retention rate among volunteers. Additionally, it will be used to exclude those that are unsuitable. The core motive constructs identified in the final framework contribute to a greater understanding of the underlying reasons why people volunteer. The study finding opens up original avenues for understanding the factors that influence the sustainability of volunteering within communities. The study extends our understanding of caring and compassion by suggesting a novel way of conceptualizing community volunteering. It also contributes to the work design literature by identifying reduced volunteering as an unintended consequence of job enrichment, and to volunteering research in psychology and sociology by revealing new contextual influences on volunteering motives and role identities. The study demonstrated that it is possible to classify tasks according to the motives they satisfy. In general it demonstrates that volunteering is good for all people, including the poor. By understanding the motivations of their volunteers through the framework, a manager of volunteers can identify and select volunteers that are likely to serve long term.

The final framework, Volunteer Assessment Framework (VAF), is short and user friendly, consisting of two core constructs (altruistic value and material gain) with ten statements as assessment items that must always be in the framework. The next two constructs (esteem enhancement and career development) with ten statements as assessment items may be additional. The remaining two constructs (social adjustment and development of understanding) with nine assessment items, would be optional. Assessing the motivational needs of volunteers can assist the management in providing the most effective placement volunteers into activities that meet their needs and are satisfying to them and thus maximize their effectiveness. The framework therefore, will make a significant contribution in seeking to enhance the recruitment, effective placement and greater retention of community health volunteers. It is therefore a useful addition to available psychometric tools for improving efficiency of recruitment and training of community health volunteers (Insert Appendix A).

Study Limitations

The study focused on western Kenyan CHVs there is a need to extend it to other contexts, and other volunteers beyond the health sector to improve the generalizability of the findings.

Further Research

More work is needed to identify the theories underpinning community concern and spirituality constructs as well as assessment items to measure them, in order to improve their usefulness in an assessment framework.

A prospective experimental study design by assessing and recruiting volunteers based on altruistic and egoistic motives and following them up to measure task performance, motive satisfaction and health outcomes would strengthen the evidence.

Abbreviations

CHV: Community Health Volunteers; CHW: Community Health Workers; VAF: Volunteer Assessment Framework; LMIC: Low and Middle Income Country.

Declarations

The publication costs associated with this article are funded by Tropical Institute of Community Health (TICH).

Ethics Approval and Consent to Participate

All participants provided written consent to participate in the study. The study protocols were reviewed and approved in Kenya, by Great Lakes University of Kisumu (GLUK) Ethics Review Board. All methods were performed in accordance with relevant guidelines and regulations of Kenya that protected the research subjects.

Consent for Publication

All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Availability of Data and Materials

The datasets used and/or analyzed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on request.

Competing Interests

The authors declare no conflict of interest

Funding

This study was funded by Tropical Institute of Community Health (TICH) in Africa.

Authors Contribution

BMO: Designed the study, managed the research process, supervised all aspects of the study and the team members, carried out the analysis of data, development of the analysis framework, and synthesized the contributions from co other author into the manuscript. She further engaged actively in the revision of the manuscript in response to critiques from co-author and took the lead in writing and editing the manuscript based on internal peer reviewers’ comments.

DCOK: Participated in the analysis of data, development of the analysis framework, reviewed and contributed to the writing of the manuscript and made suggestions aan inputs towards the final draft.

All authors have read and approved the manuscript.

Acknowledgements

This work was funded and supported Tropical Institute of Community health (TICH).

End Notes: This paper provides valuable information about the actual motivations of volunteers and their relative importance to identify volunteers likely to serve for long periods of time, especially in health programs. It offers a framework that will be instrumental in the recruitment of appropriately motivated volunteers for long-term assignments, and details a screening process which will improve the cost-efficiency of health volunteer programs by considering the motivations of their volunteers. This is critical to managers involved in the recruitment, placement and retention of volunteers.

This research opens up original avenues for understanding the factors that influence the sustainability of volunteering within communities. It will extend the reader’s understanding of caring and compassion by suggesting a novel way of conceptualizing volunteering. The article makes a major contribution to the work design literature by identifying reduced volunteering as an unintended consequence of job enrichment, and to volunteering research in psychology and sociology by revealing new contextual influences on volunteering motives and role identities.

References

- WHO guideline on health policy and system support to optimize community health worker programmes. 2018.

- Hongoro C, McPake B (2004) How to bridge the gap in human resources for health. Lancet 364: 1451-56.

- World Health Organization (2006) Intergrated community case management (Iccm) guide.

- Haines A, Sanders D, Lehmann U, Rowe AK, Lawn JE, et al. (2007) Achieving child survival goals: potential contribution of community health workers. Lancet 369: 2121-2131. [crossref].

- Jones PM (2003) Juilliard: A History. 24 issue: 197-201.

- Winch PJ, GK (2005) Intervention models for the management of children with signs of pneumonia or malaria by community health workers. Health Policy Plan 20: 199-212. [crossref].

- Rowe A (2007) Entry on ‘Friendship’ in Y. Jewkes and J. Bennett. Dictionary of Prisons and Punishment.

- Macro International Report 1998.

- Walt G (1990) Community health workers in national programmes: just another pair of hands? Open University Press.

- Bhattacharyya K, Winch P, Le BK, Thien M (2001) Community health worker incentives and disincentives: How they affect motivation, retention, and sustainability.

- Ferketich S, Phillips L, Verran J (1993) Focus on psychometrics. Development and administration of a survey instrument for cross-cultural research. Research Nurses Health 16: 227-30. [crossref].

- Netemeyer RG, Bearden WO, Sharma S (2003) Scaling procedures: Issues and applications. Thousand Oaks, Sage.

- Cronbach LJ, Meehl PE (1955) Construct validity in psychological tests. Psychological Bulletin 52: 281-302. [crossref].

- Brink PJ, Wood MJ (1998) Advanced design in nursing research. Thousand Oaks, Sage.

- Polit DF, Beck CT (2004) Nursing Research. Principles and Methods. Lippincott.

- Schultz KS, Whitney DJ (2005) Measurement theory in action. Thousand Oaks. Sage.

- Saunders M, Lewis P, Thornhill A (2003) Research Methods for Business Students England: Prentice Hall.

- George, Darren & Mallery, Paul (2003) SPSS for Windows Step-by-Step: A Simple Guide and Reference.

- Cronbach LJ (1951) Coefficient Alpha and the Internal Structure of Tests. Psychometrika 16: 297-334.

- Hatcher L (1994) A Step-by-Step Approach to Using the SAS System for Factor Analysis and Structural Equation Modeling.

- Clary EG, Miller J (1986) Socialization and situational influences on sustained altruism. Child Dev 57: 1358-69. [crossref].

- Anderson JC, Moore LF (1978)The Motivation To Volunteer. Journal of Voluntary Action Research 7: 120-129.

- Omoto, Synder, Omoto, Allen M, Mark Snyder (2002) Considerations of Community: The Context and Process of Volunteerism. American Behavioral Scientist 45: 846-867.

- Kironde S, Banjunirwe F (2002) Lay workers in directly observed treatment (DOT) programmes for tuberculosis in high burden settings: Should they be paid? A review of behavioral perspectives. African HealthScience 2002: 73-78.

- Kaseke R, Dhemba J (2006) Five country study on service and volunteering in Southern Africa: Zimbabwe country report. Centre for Social Development in Africa.

- Ochieng BM, Kaseje DCO, Wafula CO (2012) Journal of Developing Countries Studies 2: 36-43.

- Francies GR (1983) The volunteer needs profile: Atool for reducing turnover. The Journal of Volunteer Administration 1: 17-33.

- Clary EG, Mark S, Robert DR, John C, Arthur AS et al. (1998) Understanding and Assessing the Motivations of Volunteers: A Functional Approach. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology 74: 1516-1530. [crossref].

- Harrison, David A (1995) Volunteer Motivation and Attendance Decisions: Competitive Theory Testing in Multiple Samples From a Homeless Shelter. Journal of Applied Psychology 80: 371-385.

- Fisher, Robert J, David A (1998) The Effects of Recognition and Group Need on Volunteerism: A Social Norm Perspective. Journal of Consumer Research 25: 262-275.

- Katz D (1960) The functional approach to the study of attitudes. Public Opinion Quarterly 106-204.

- Smith M, Bruner J, White R (1956) Opinions and personality.

- Beale AV (1984) Exploring careers through volunteerism. The School Counselor 32: 68-71.

- Phillips, Michael (1982), Motivation and Expectation in Successful Volunteerism. Journal of Voluntary Action Research 11: 118-125.

- Smith, David H (1981) Altruism, Volunteers, and Volunteerism. Journal of Voluntary Action Research, 10: 21-36.

- Stukas, Arthur A, Daly, Maree and Cowling, Martin J (2005) Volunteerism and Social Capital: A Functional Approach. Australian Journal on Volunteering 10: 35-44.

- Herek GM (1987) Can functions be measured? A new perspective on the functional approach to attitudes. Social Psychology Quarterly 50: 285-303.

- Snyder M, DeBono KG (1987) A functional approach to attitudes and persuasion. Social influence: The Ontario Symposium 5: 107-125.

- Clary EG, Snyder M (1999) The motivations to volunteer: Theoretical and practical considerations. Current Directions in Psychological Science 8: 156-159.

- Clary EG, Snyder M, Ridge R (1992) Volunteers’ motivations: a functional strategyfor the recruitment, placement, and retention of volunteers. Nonprofit Management and Leadership 2: 333-350. [crossref].

- Clary EG, Synder M, Stukas AA (1996) Volunteers Motives. Findings from a National Survey. Nonprofit and Voluntary Sector Quarterly 25: 485-505.

- Omoto AM, Snyder M (1995) Sustained helping without obligation: Motivation, longevity of service, and perceived attitude change among AIDS volunteers. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology 68: 671- 686. [crossref].

- Omoto AM, Snyder M, Berghuis JP (1993) The psychology of volunteerism: A conceptual analysis and a program of action research. The Social Psychology of HIV Infection 333-356.

- Snyder M (1993) Basic research and practical problems: The promise of a “functional” personality and social psychology. Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin 19: 251-264.

- Snyder M, Clary EG, Stukas AA (2000) The functional approach to volunteerism. Why we evaluate: Functions of attitudes.

- Snyder M, Omoto AM (1992) Volunteerism and society’s responseto the HIV epidemic. Current Directions in Psychological Science 1: 113-116.

- Snyder M, Omoto AM (1992) Who helps and why? The psychologyof AIDS volunteerism. Helping andbeing helped: Naturalistic studies. Newbury Park, Sage. 213-239.

- Clary, Snyder (2005) A Functional Approach to Volunteerism: Do Volunteer Motives Predict Task Preference? Basic and Applied Social Psychology 27(4).

- Morrow HN, Mui AC (1989) Elderly volunteers: Reasons for initiating and terminating service. J Gerontol Soc Work 13: 21-34.

- Kohlberg, Howarth E (1976) Personality characteristics of volunteers. Psychological Reports 38: 855-858.