DOI: 10.31038/PSYJ.2021351

Abstract

The paper presents two studies dealing with attitude towards closing economic gaps, as defined by the poet Percy Bysshe Shelley’s aphorism ‘The rich get richer, and the poor get poorer.’ Both studies worked with sets of 16 different messages, elements that were combined into small vignettes comprising 2-4 elements, the combinations dictated by an underlying experimental design (Mind Genomics). In Study #1 the elements were actual solutions respondents rating the feasibility of the combination of solutions The results from 51 respondents suggest three different mind-sets about what will close the economic gaps ways of evaluating the elements, so-called mind-sets (MS- A1 Business takes lead to create solutions, MS-A2 Can’t think of solutions, MS-A3 Big picture activists). In Study #2 the elements were either specific people, or roles that people fill. The results from101 respondents suggest that there are only two mind-sets about who can close the economic gaps (MS-B1 those who work through power, orders and hierarchy, MS-B2 those who work by convincing others.) The two studies present a complementary pair of approaches to understand the mind of the citizen from the ‘inside out’ when the topic is a societally relevant problem.

Introduction

One need only read the news to get a sense that the economic situation of the middle and the lower classes is becoming increasing dire. Over the past decades, the disparity in income or really in purchasing capabilities have widened, until there is almost a sense of a shrinking middle class, and an increasing group of people who are living from check to check, simply because of the high prices. The awareness of the disparity is decades old [1-3]. The answer is the economy, of course, just like it was in 1992, when William Clinton was elected. The problems of today, 2021, are more severe, however, and the issues far deeper. Economic issues, especially the massive disparity between the rich/ultra-rich and everyone else is codified in the phrase ‘the 1%.’ Furthermore, at the time of this writing, inflation is rearing its ugly head, goods are becoming in short supply because of the ‘supply chain,’ lawless is breaking out across the United States, the country is emerging slowly from the ravages of COVID-19 pandemic, and the nation is divided into the red states and the blue states, the so-called Republican (party) States, and the so-called Democratic (party) states. In other words, the Fraying of America, a term coined by Arthur Kover in work begun a decade ago with Howard Moskowitz, awaiting publication [4].

The traditional answers to the general issue of economic disparity range from laissez-faire (as it is being one today, November 2021, by President Biden, in the United States), to more activist efforts such as government actions [5]. Beyond government action are community/social activities [6], education [7]. All the methods being tried are being stress4r when they move from the almost-hobby nature, serious national application [8].

In the beginning of 2021, Arthur Kover suggested that Mind Genomics be applied to the issue of America’s problems, first to see whether one could create a series of ‘solutions’ and see how they worked with 26 different societal problems, and second to look at the same set of 26 societal problems, but this time look at people (specific individuals or generic titles) to see how they might be perceived as able to solve the problems. This second approach was novel; to identify different individuals, really ‘icons’, combine these icons into small groups, and ask whether the small group would be able to cooperate and arrive at a solution [9]. The ideas for both experiments came in part from conversations about systems thinking and systematic approaches to problems [10].

Mind Genomics – What It Is, Where It Comes From, and How It Works?

The typical approach to social research comprises either observation or studies of large-scale systems, inspired by sociology, or in-depth observation of a small ‘world’ inspired by anthropology. These approaches tend to be observational, looking from the outside in. The observational approaches are complemented by research using surveys, where respondents are instructed to answer many questions about a topic, the questions then tabulated to give a profile of the topic. The observational approaches are also complemented by qualitative research, discussions with the respondent, whether alone (in-depth interview), in pairs (dyads) to allow for interactions, or focus groups with three or more respondents.

The traditional methods are valuable sources of data, but they are not experiments. They are data gathering methods of what exists. They do not show causation, although sometimes causation can be hinted at through so-called causal modeling, an advanced form of statistical regression analysis [11].

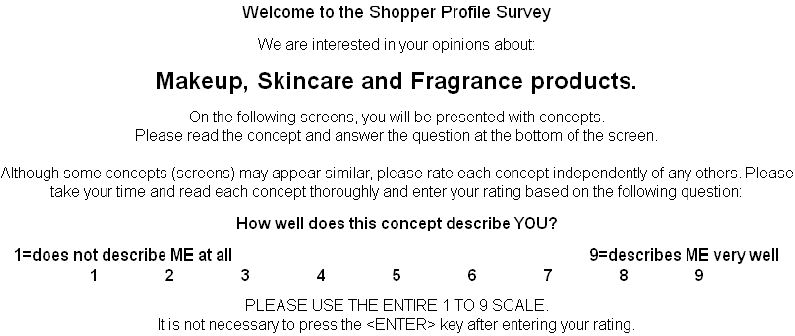

Rather than working from the ‘outside-in’ Mind Genomics focuses on the pattern of responses of people to test stimuli, these test stimuli approach for the topic. The researcher in Mind Genomics identifies the topics, identifies relevant ideas in the form of ‘messages’, combines these messages into small, easy to read ‘vignettes’, presents the vignettes to the respondent, obtains the rating of the vignette, and then deconstructs the rating into the contribution of the different messages.

The Mind Genomics approach relies on experiment, on observing the pattern of responses of people to messages dealing with everyday life. The respondent, in turn, is a simple responder, a subject present with this material. The research does not focus on what the respondent says she or he ‘feels’ or ‘thinks’, but simply how the respondent behaves when confronted with the test material.

The foregoing may seem overly subtle and controlled, because it seems so natural to ask questions and to get honest answers. The reality is quite different, however. Most people come with many biases, some to give the ‘right answer’, some to please the interviewer, some to avoid conflict, and so forth. Just as important is the reality that the topics spread across many dimensions, e.g., social, economic, personal, and so forth. The criteria differ from dimension to dimension, but the respondent may not even be aware of these differences.

Mind Genomics was designed to deal with the decision processes of everyday, taking into account the fact that the situations of every day are multi-faceted. Although one might think that a person could adjust the criterion of judgment to be appropriate to the topic, a questionnaire which intersperses different topics becomes hard to deal with, as the criteria demand vary from question to question. A simpler way might be to present the respondent with different stories, doing so rapidly, and request a rating of each story (or combination). One could then attempt to deconstruct the response to the combination, to the vignettes, and estimate the contribution of each component in the vignette, viz., each message or idea. The respondent would not be able to be politically correct. A rapid evaluation of different vignettes would lead to the respondent simply guessing, rather than trying to be correct. Guessing, not trying to give the perfect answer is more typical of everyday behavior.

Its original format, Mind Genomics was set up to look at what drives ‘YES’ for various offers of features, both in products and in services [12,13]. The effort was modeled after the pioneering effort by Wharton professors Paul Green and Yoram Wind [14]. The Mind Genomics process comprised a simple set of features, combined by an experimental design, which prescribed the precise combinations of the features. Each respondent evaluated a unique set of combinations each set a permuted variation of the basic design [15]. It was easy to run these experiments the experiments could be done on a wide variety of topics, and the output was easy to understand, inexpensive to run fast allowing for iteration, and databasing [16,17].

Mind Genomics evolved, from large studies to small, study, easy to set up, and to execute. The focus of the studies evolved from products to social issues. Mind Genomics provided a way to get into the mind of a person, not by the usual observation or questionnaire, but by a simple, hard-to-‘game’ experiment. The respondent would evaluate a set of vignettes (here 24), comprising prescribed combinations of elements, or statements about the topic. The respondent was instructed to read the entire vignette, and the rate the combination on an anchored scale. . Although it sounds difficult to do, and although the respondents attempt to ‘do it right’ and give the ‘correct answer,’ the reality is that only a perfect with perfect memory could even suspect that there was an experimental design controlling the combinations. To most people, the combinations were described as ‘random’, and responded to as such. Most exit interviews revealed that the respondents felt that they just ‘guessed’.

Complementing the elements and the experimental design, was the rating scale. At first the rating sale was a simple 9-point sale, with the assumption that 9 points would allow for more discrimination than a shorter scale of fewer points. Events soon made it clear that the users of the results had no idea what a 6 meant on a 9-point scale. As tractable and sensitive to fine differences the 9-point scale seemed to be, it was hard to understand. Managers would often ask questions which ended up being ‘what does the data mean – please explain). It was to this end that the scale was shorted to five points, and often labelled, usually at both end anchors, ]but now often labelled at each of the five points.

The Worldview of Mind and How It Drives the Design of the Two Experiments

As noted above, traditional research about problems works with the description of a problem, followed either by a discussion about the problems and solutions (qualitative research) or a set of questions dealing with aspects of the topic (survey). The survey questions may be open ended, following the approach of qualitative research, or the questions can be answer on rating scales. The analysis would then present a summary of the discussion or open-ended answers for qualitative research, or a tabulation of answers for the survey.

Mind Genomics follows a different path, combining aspects from three different disciplines, whose aspects it amalgamated into a nascent science with the aim of understanding the mind of the ‘everyday experience,’ and databasing that information.

Psychophysics

The study states the relation between physical stimuli and perceptions. The notions of psychophysics is that one can ‘measure’ private sensory experience The typical psychophysical study has systematically varied stimuli from a simple physical continuum (e.g.., sound pressure levels of noise, even statements of different amounts of money, or statements about different crimes), and instruct the respondents to assign numbers to represent some perceived aspect such as loudness of the noise, perceived ‘happiness’ or utility corresponding to the different amounts of money, or the seriousness of the crimes. In other words, psychophysics focuses on relating the physical level of the stimulus (e.g., stated amount) to a felt intensity of a response (e.g., degree of happiness, degree of the value of money, ability to buy things, etc.) There is inherent magnitude in both the independent variable, and in the response rating itself.

Experimental Design (Statistics)

Create test stimuli in such a way as to allow the research to gain information about the stimuli by comparing ratings to each other, and by creating a mathematical equation. Mind Genomics works on the response to defined mixtures of stimuli, as we will see below. The experimental design prescribes the specific experimental designs needed for Mind Genomics to create equations at the level of the individual respondent.

Consumer Research

Use consumer research to run surveys (actually experiments which look like surveys) with the results already in the form of a scalable, cross-referenceable database, the foundation of a new science, the mind of the everyday.

Two Studies -What Drives Three Strong Responses – Absolutely Yes, Absolutely No, Don’t Know?

Just to reiterate, our focus now is on the emerging issue of inequality, as summarized by ‘the rich get richer, the poor …’ the topics are HOW can that issue of economic inequality be solved, and WHO can solve it. We will look at the data from the point of what respondent feel will work, won’t work, and can’t even approach to be appropriate in the situation

Study 1: How Solutions Drive Perceived Feasibility

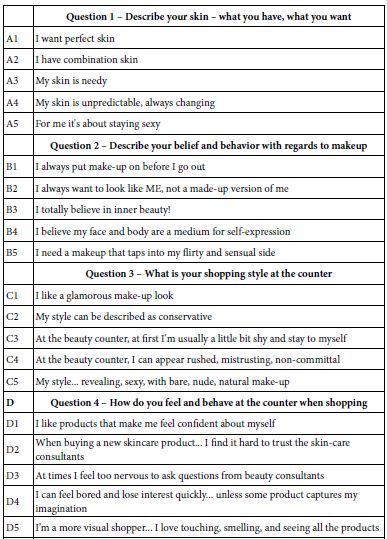

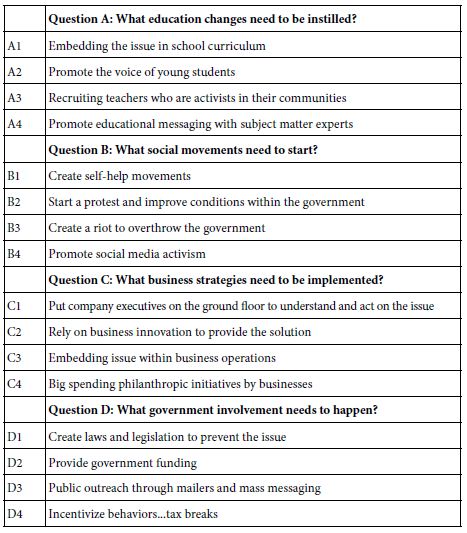

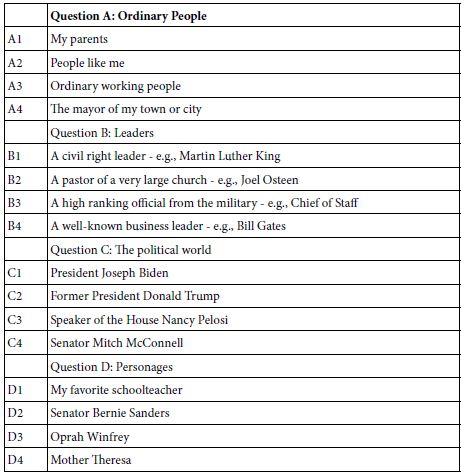

Our first study concerns a series of solutions of different types, taken in part from the summarizations of Baumann & Majeed (2020). Table 1 shows the different solutions, as well as the question ‘driving’ the solution. The important thing to keep in mind is that the solutions are generic. The solutions can work with anything.

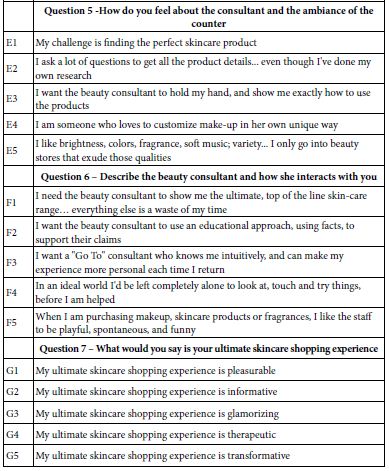

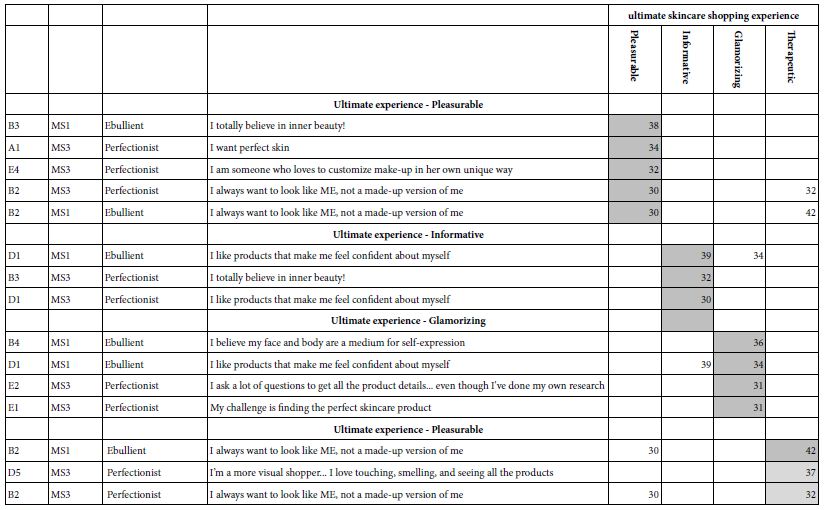

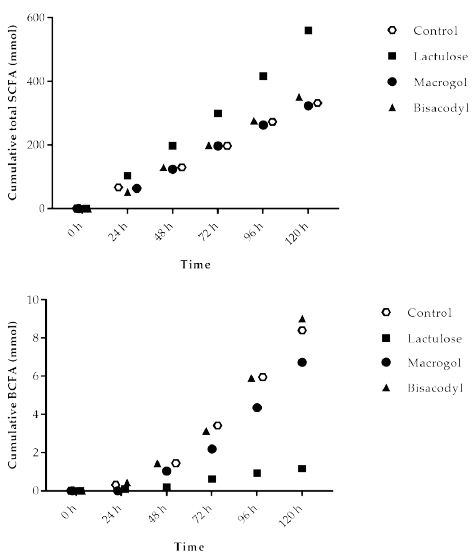

Table 1: The four types of solutions, and the four specifics in each type of solution.

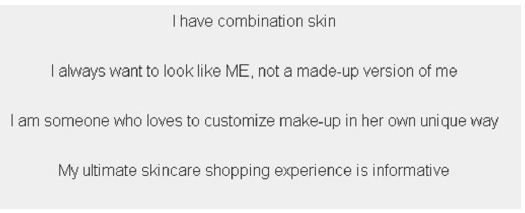

We begin with the self-profiling question, and the rating question and answers. The rating question introduces the problem. It is short, to the point. The objective is to have the 16 specifics provide the information that will be rated.

a. A set of self-profiling questions, including age, gender, and the third question below

What is the most effective approach to solve the problem of Economic gap – Rich people get richer, everyone else falls behind.

1=Education Changes 2=Social Movements 3=Business Strategies 4=Government Rules

b. Orientation to the topic and the 5-point anchored rating scale

What is the most effective approach to solve the problem of Economic gap – Rich people get richer, everyone else falls behind.

RATE1=Will encounter resistance … and… Probably won’t work

RATE2=Will not encounter resistance… but … Probably won’t work

RATE3=Can’t honestly decide

RATE4=Will encounter resistance… but … Probably will work

RATE5=Will not encounter resistance … and… Probably will work

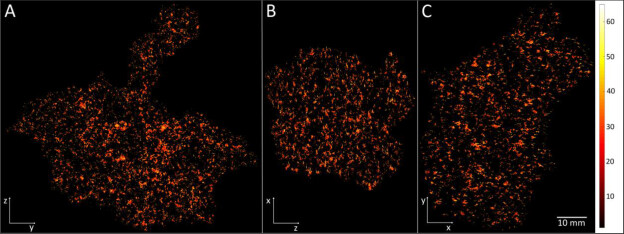

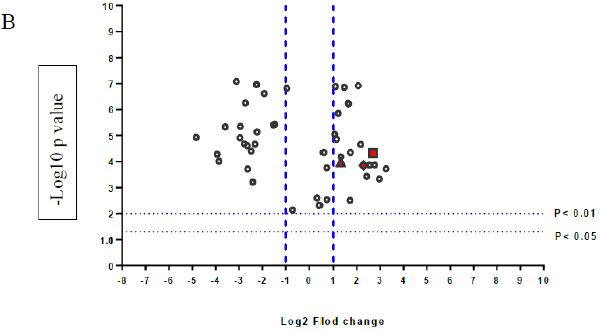

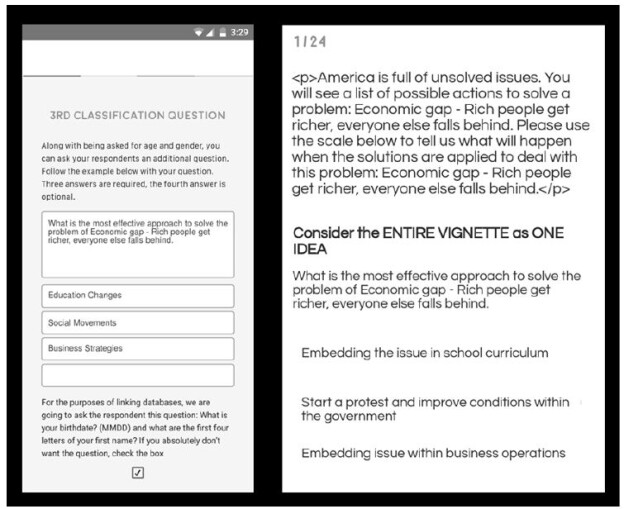

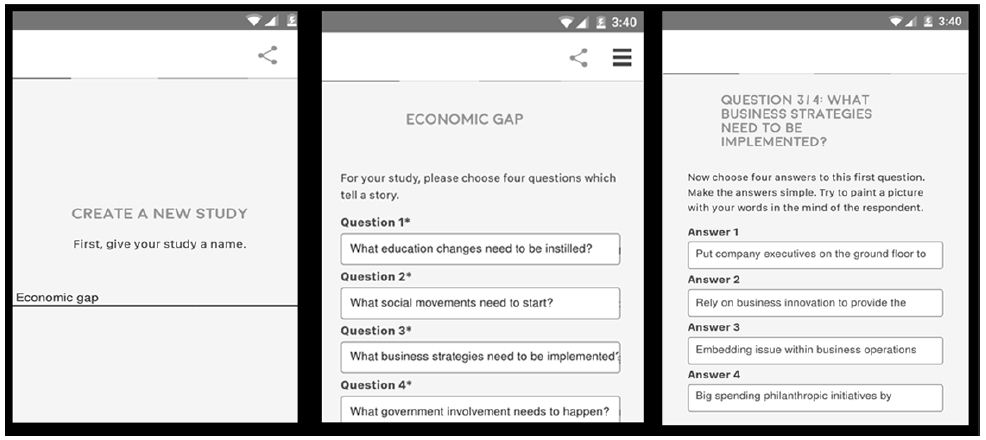

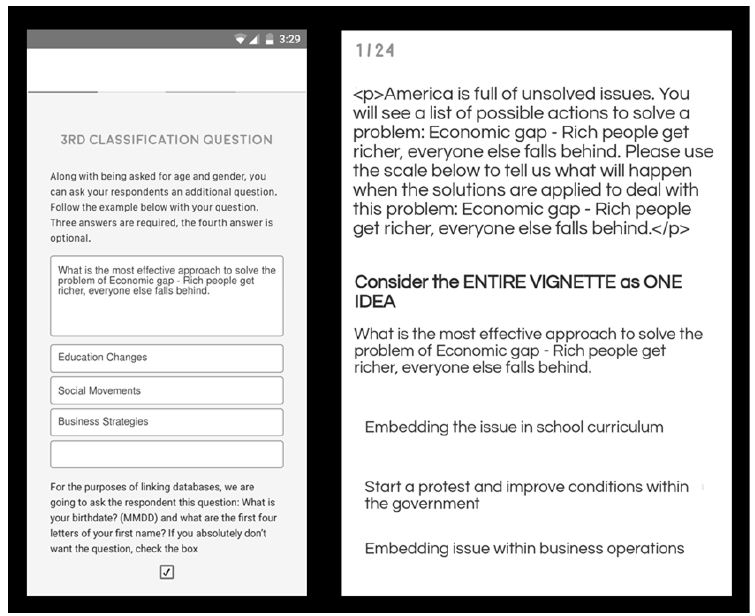

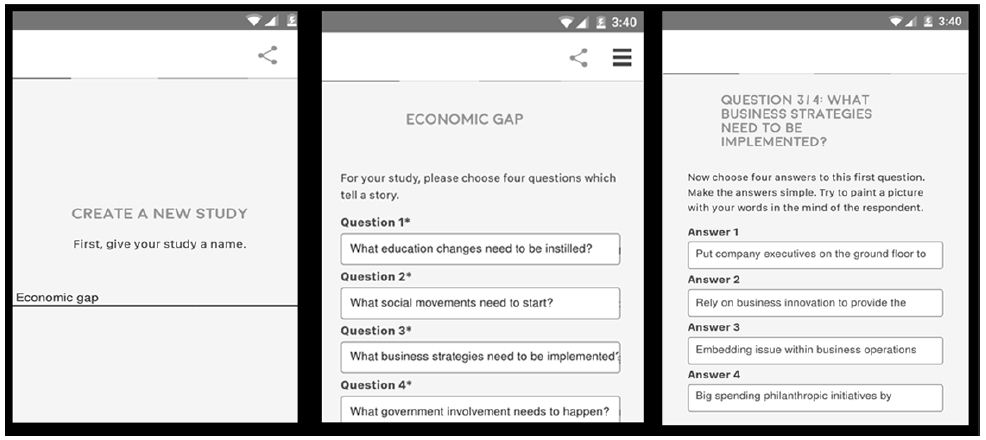

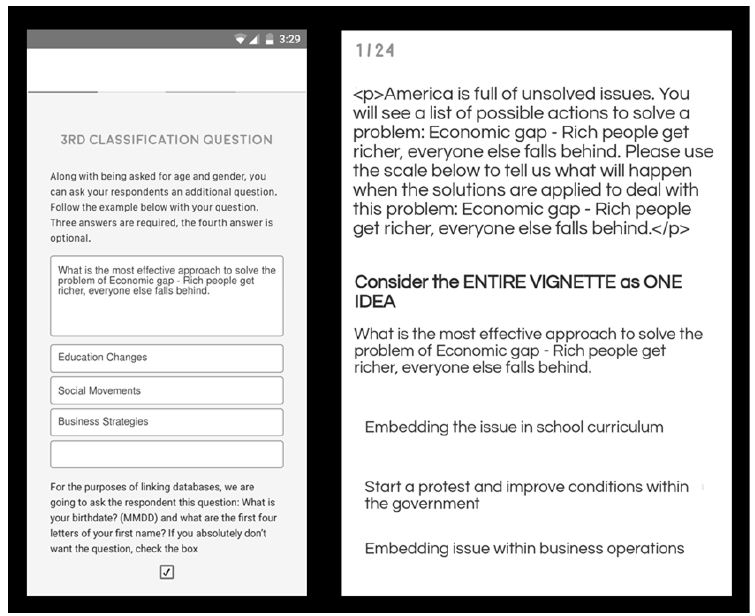

The set-up for these Mind Genomics studies is templated, enabling the researcher to follow a simple series of steps to provide the necessary information. Figure 1 shows the set-up template. Figure 2 shows two screens in the set-up template, screens that show the self-profiling classification, and an example of a vignette.

Figure 1: The set-up template for the first Mind Genomics study on the solutions to problems.

Figure 2: Example of the set-up screen for the third self-classification (left) and an example of the set-up page showing a test vignette (right).

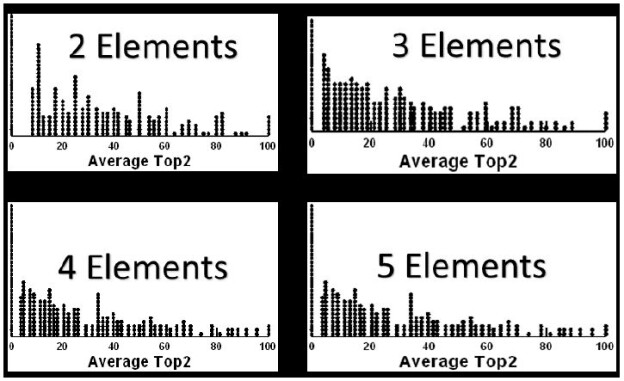

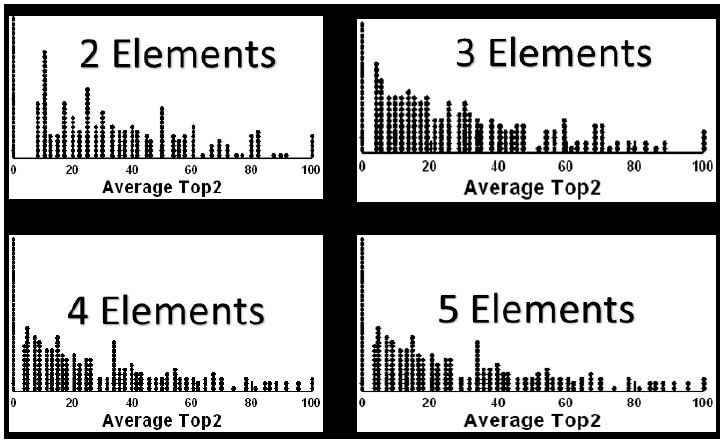

This first study was run with 50 respondents. Each respondent rated the set of 24, unique vignettes created by mixing the 16 elements into combinations comprising 2-4 elements. Each question contributed at most one element to a vignette, but for four vignettes contributed no elements to the vignette. Every element appeared five times in 24 vignettes and was absent 19 times. The experimental design was set up to allow for an individual-level regression relating the presence/absence of the 16 elements to the responses. For this project, the preliminary analysis created four dependent variables:

- RATE1=Will encounter resistance … and… Probably won’t work. When the rating was ‘1’ on the 5-point scale RATE1 took on the value 100. When the rating was not ‘1’ on the 5-point scale, RATE1 took on the value 0. RATE1 corresponds to a belief that the solution will not help solve economic inequity, the problem posed in the introduction.

- RATE5=Will not encounter resistance … and… Probably will work. When the rating was 5 on the 5-point scale RATE5 took on the value 100. When the rating was not 5, RATE5 took on the value 0. RATE5 corresponds to the belief that the solution will help solve the problem of economic inequality.

- RATE3=Can’t honestly decide. When the rating was 3 on the 5-point scale RATE3 took on the value 100. When the rating was not 3 on the 5-point scale, RATE3 took on the value 0.

- RT – The measured response time from the time the vignette was presented to the time the rating was assigned

To ensure that there would be at least minimal variation in the dependent variable, viz., the newly created binary scales (RATE1, RATE3, RATE5), a vanishingly small random number (<10-5) was added to each newly created binary variable for every case. The added variability does not affect the regression but ensures that there is the requisite variability so that the regression does not crash.

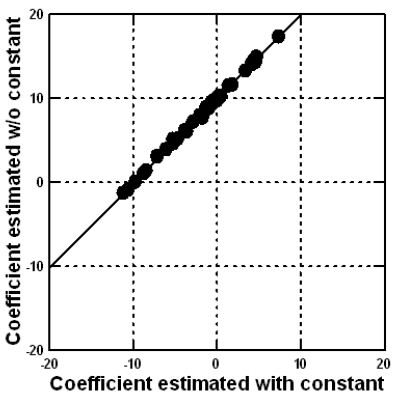

The regression model was run without an additive constant, to allow direct comparisons of the coefficients across groups. The regression equation, estimated using OLS (ordinary least-squares) methods, is expressed as: Dependent Variable=k1(A1) + k2(A2) … k16(D4)

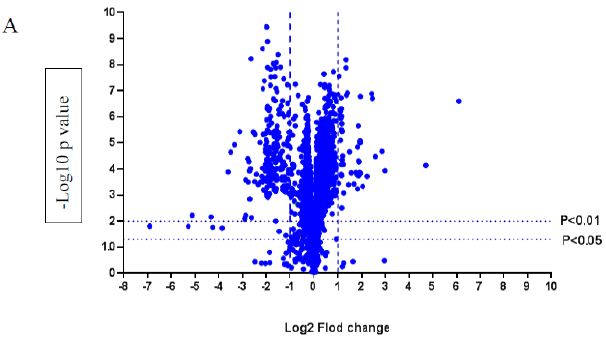

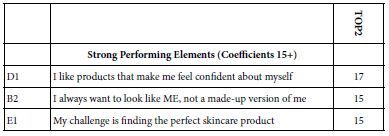

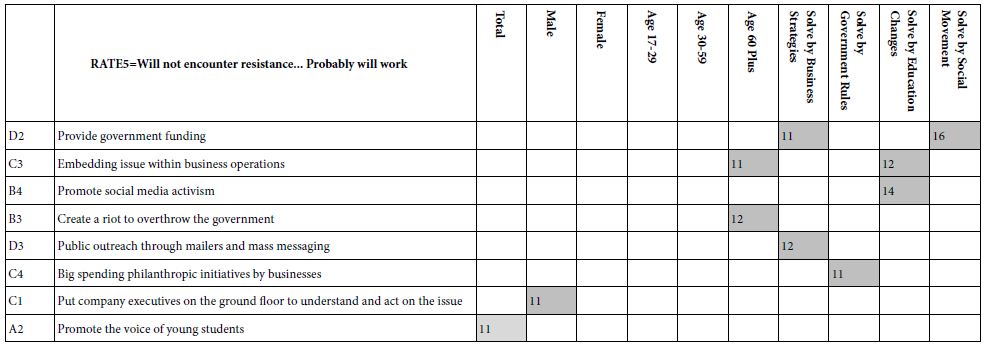

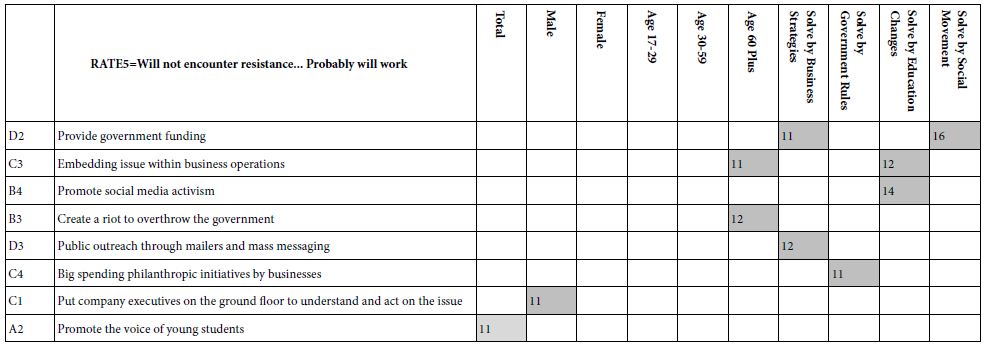

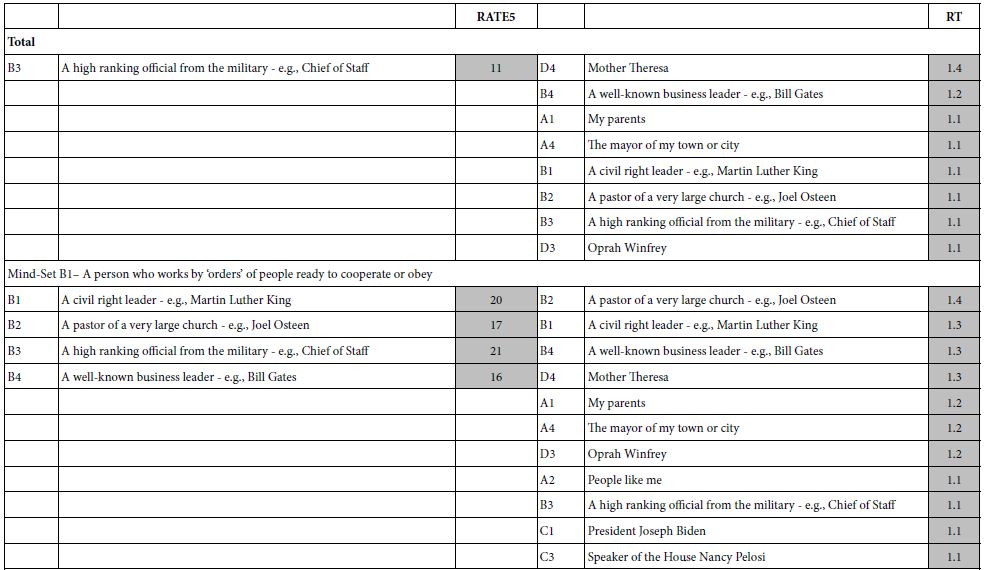

The self-profiling classification allows us to assign each respondent to gender, to age group, and to the way that problems of this type might be solved. The definition of the subgroups generates 10 different groups. We show only those elements with coefficient of 11 or higher, coefficients that would be clearly significant. The elements and the strong performing coefficients appear in Table 2. The elements are sorted by the sum of the strong performing coefficients. Thus, the strongest performing element in this reduced set of elements is D2 (Provide government funding). The weakest, but still strong performing elements are C4, C1, and A2, all with one strong group, and coefficients of 11.

Table 2: Strong performing elements by element and key self-defined subgroup for RATE5 vs the 16 elements. Only coefficients of 11 or higher are shown.

It is important to note that there is no clear pattern, either by element or by self-classification. Furthermore, half the elements simply fail to drive a perceived ability to drive a strong solution (viz., RATE5). We might have more elements appearing if we create the model based on a combination of RATE4 and RATE5, both saying that the solution will probably be successful, but RATE4 saying it will encounter resistance, and RATE5 saying it will not encounter resistance.

The importance of this first result is that there are no simple solutions. Either the solutions are weak, or the groups are so variable in what the people of the group believe to work that the power of the idea of the solution is attenuated.

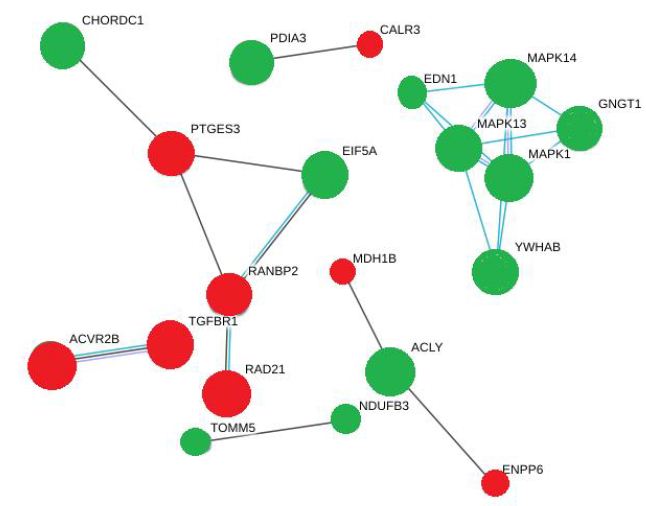

An ongoing theme of Mind Genomics is that there exists in everyday experience a different group of ideas which constitutes ‘mind-sets.’ A mind-set comprises a set of ideas which ‘travel together’ and which can be interpreted. That is, the mind-set makes intuitive sense, and tells a meaningful story.

The mind-set emerges from the pattern of responses to the different elements. Once we see which elements emerge together as strong, we may find that the pattern almost ‘jumps out at us.’ When we work with a set of elements for a specific topic, usually about 2-3 mind-sets emerge. There could be more, but the ideal is to work with mind-sets that are interpretable (tell a story), and which are relatively few in number for the topic. Fewer mind-sets are better than many, even though as we extract more and more mind-sets from the same data the story gets clearer, because we focus on narrower and narrower ranges of ideas.

The mind-sets emerge from a simple mathematical analysis, and not from preconceived notions of the researcher. The mind-sets emerge sing the mathematical methods called clustering which puts into separate groups the various objects (viz. respondents) based upon some quantitative criterion. For example, one may put together individuals who show very similar patterns of coefficients. The similarity in the pattern of coefficients from one person to another suggests that these people think in similar fashion.

Our data provides the ideal set up for k-means clustering [18]. Each respondent evaluated 24 vignettes arranged according to an experimental design. We can create an individual level equation for each respondent. The equation will be written as it was before: Dependent Variable=k1(A1) + k2(A2) … k16(D4)

The clustering program works with the 51 sets of 16 coefficients, one set for each of the 51 respondents, one coefficient for each of the 16 elements. The clustering program first computes the ‘distance’ between each pair of respondents, defined as (1-Pearson R). The Pearson R is a measure of the strength of a linear relation. If two respondents show a perfect correlated set of 16 coefficients, the correlation is +1 their distance is 0 . The distance is 1-1=0.

The clustering was done using RATE5 as the dependent variable. The first step in the clustering was to run the 50 regression models, each without the additive constant, as noted above. The second step was to apply the k-means clustering, and extract three mind-sets. Two mind-sets produced a more parsimonious set, but the stories were not clear, viz., interpretability was not sufficient.

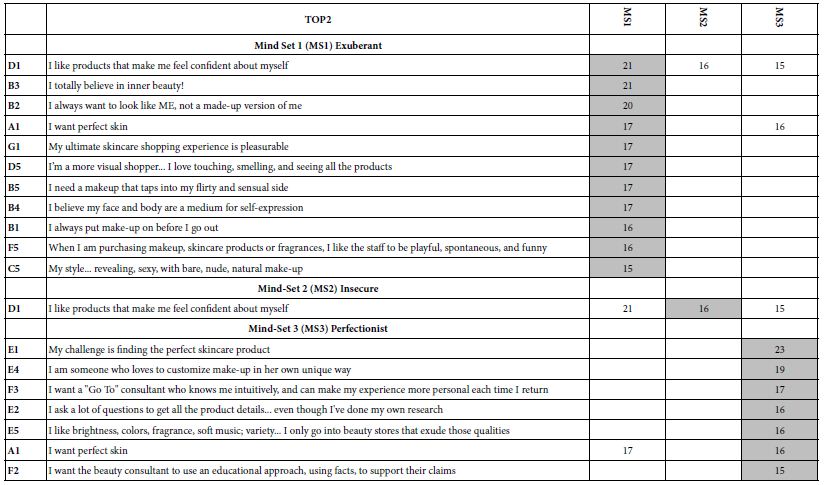

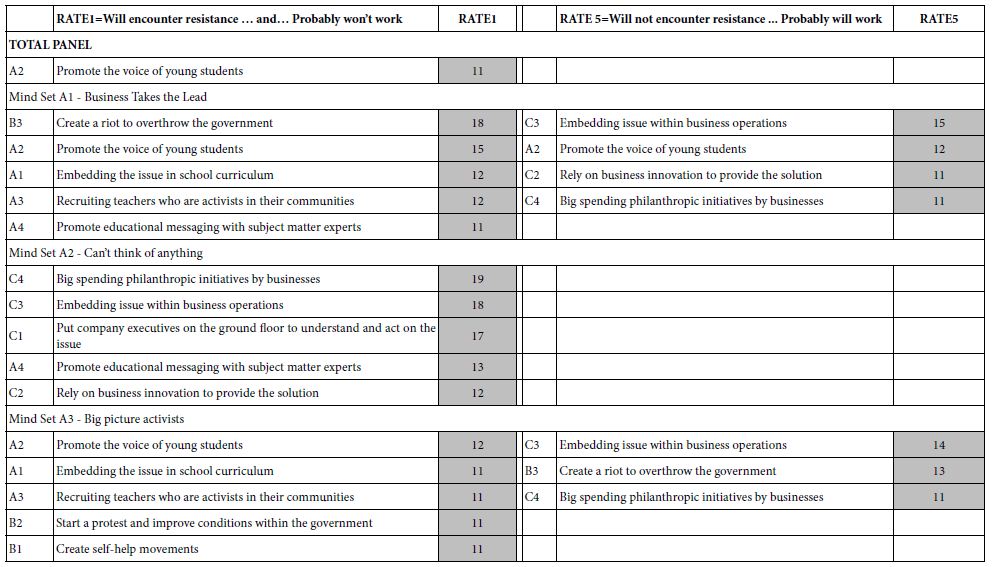

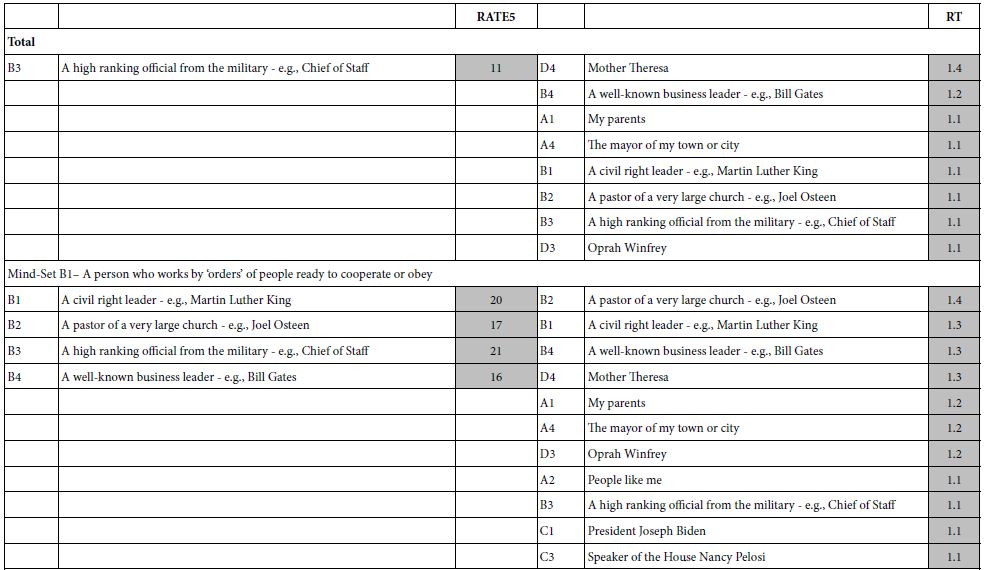

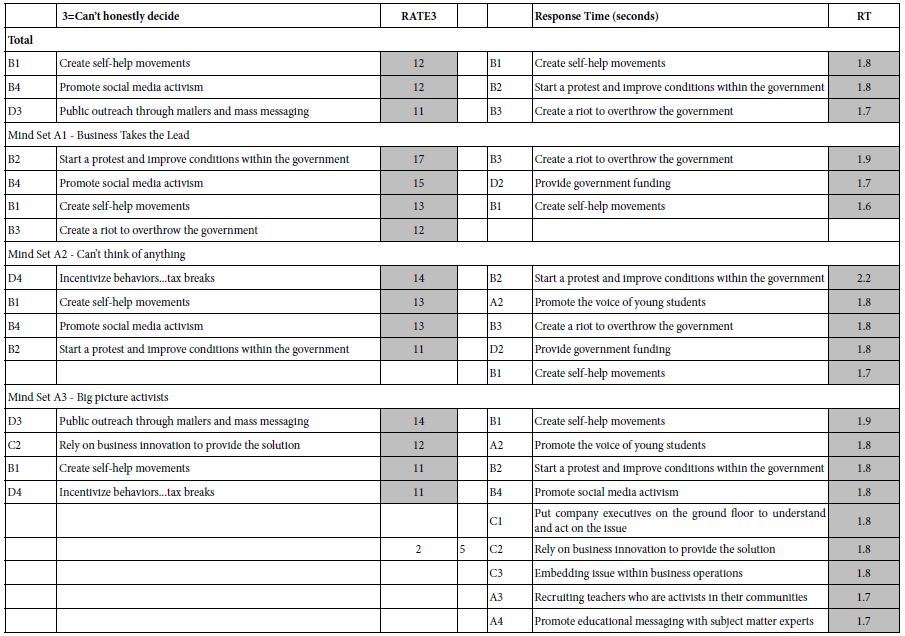

Finally, the k-means clustering program assigned each of the 51 respondents to one of the three clusters or mind-sets, based upon a measure of cohesiveness of the cluster. After each respondent was assigned to one of the three non-overlapping clusters, it was a simple matter to run four equations for each cluster, using only those respondents assigned to the cluster. The four equations were RATE1, RATE5 (Table 3), and RATE3 and Response time (Table 4).

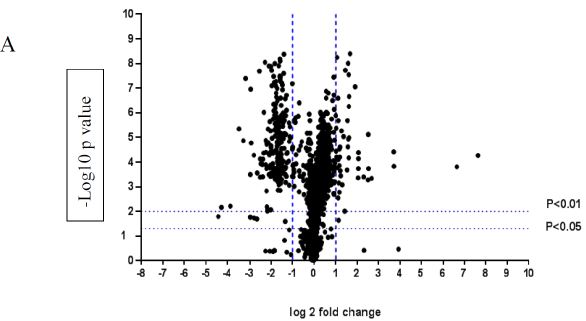

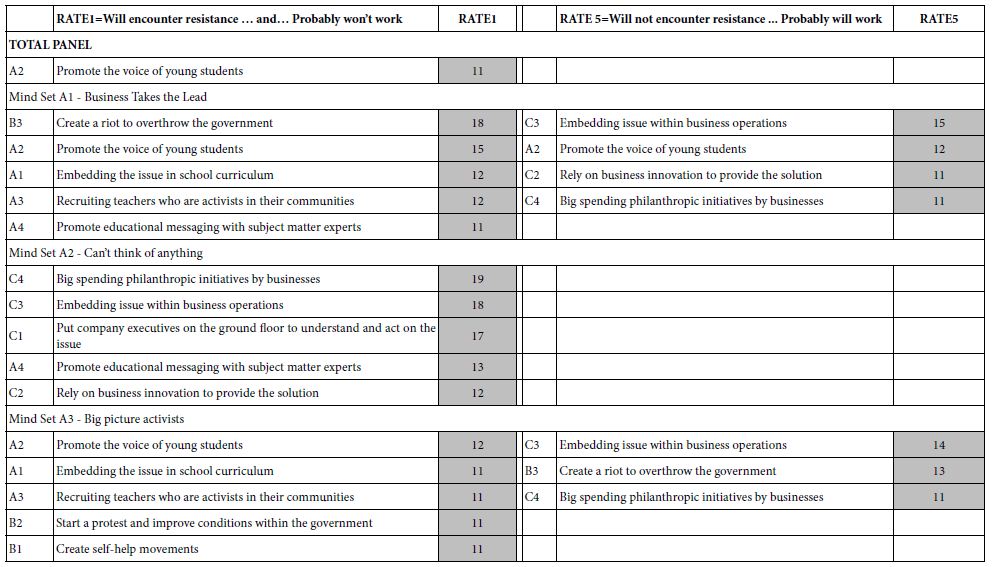

Table 3 presents the results for Total panel and for the three mind-sets. Based upon the strong performing elements, we can call the mind-sets as following:

Table 3: Strong performing elements for total and for each mind-set, based upon the model for RATE1 (encounter, resistance and won’t work), and based upon the model for RATE5 (encounter no resistance, will work).

Mind-Set A1=Based on Rate 5: Business Takes the Lead

The business has to be open to new ideas, receptive to solving the problem as part of the business flow and be open to innovation. Avoid activism. The only solution which is problematic is listening to the voice of young people. There are those in Mind-Set3 who think it will work, and those who think it won’t work, based upon the strong performance of element A2 (Promote the voice of young students) for both RATE1 and RATE5.

Mind-Set A2– Can’t Think of Anything

Mind-Set 4 is interesting simply because nothing seems to have a chance of working. On the other hand, when it comes to this mind-set thinking about what absolutely won’t work, viz., how they perform on RATE1 (resistance/won’t work) they ae negative to the ideas which seen perfectly reasonable to others.

Mind-Set A3 – Big Picture Activists

They want major change, which can be through business practice, major philanthropic donations from business, or even through riots. They don’t believe in slow activist movements.

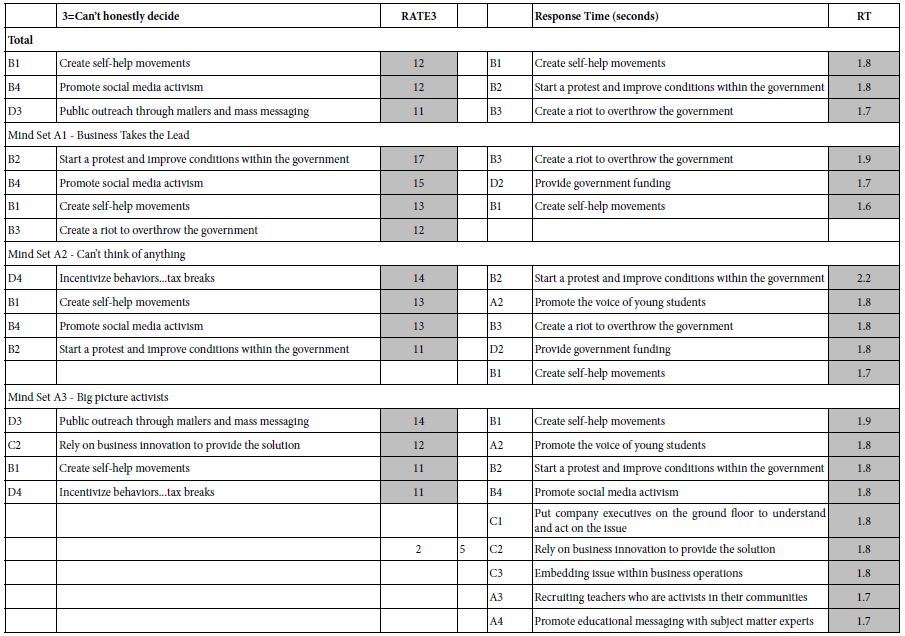

Table 4 presents the strong performing elements for RATE3 (cannot decide), and for response time (RT). The models were once again the standard linear models, without an additive constant. The dependent variable for RATE3 was the binary transformed value for ratings that were either 3 (transformed to 100), or not 3 (transformed to 0). The dependent variable for response time, the number of seconds did not need any added very small random number because there was clear variation among the different response times.

Table 4: Strong performing elements for total and the three mind-set segments, for RATE3 (can’t decide) and RT (response time).

In contrast to the interpretations for RATE1 (NO) or RATE5 (YES), the elements driving RATE3 do not tell a coherent story. There are three strong performing elements for Total Panel, and four strong performing elements for each mind-set. In no mind-set do we see a story.

The elements driving long response times are not related to the mind-set itself, but tend to of two types, either starting a riot or protest, or create a self-help movement Both of these seem emotionally evocative, suggesting that the response time measure is not a measurement of good/bad, but rather of the startle-value of the idea, coupled with the ability of the idea to paint a suggestive word picture.

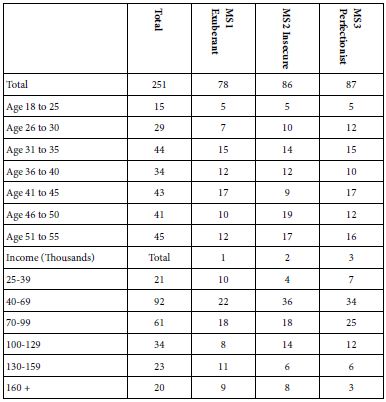

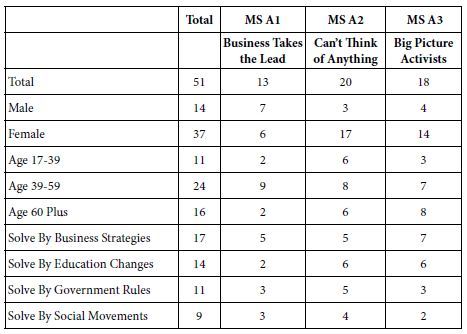

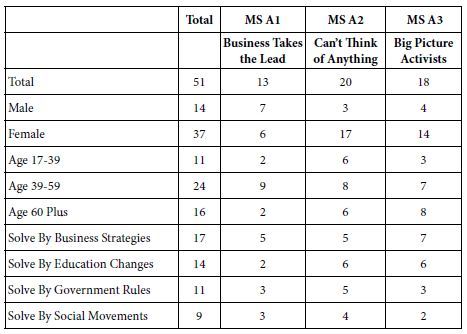

Table 5, showing the distribution of respondents in the three emergent mind-sets reveals no simple pattern. It often comes as a surprise that when we penetrate a topic, people faced with the same topic find radically different points of view when they evaluate specifics. These different points of view emerging from a ‘micro-topic’ often fail to emerge when the topics so large as to avoid specifics. Thus the 17 people who say that problems can be solved by business strategies do not fall into Mind-Set A1 (Business Takes the Lead). Only 5 of 17 respondents are assigned to the correct mind-set. Similarly, of the nine respondents who way that the problem can be answer by social movements, only two are assigned to Mind-Set A3 (Big Picture Activities).

Table 5: Distribution of the respondents across the three mind-sets for study 1 (Solutions).

Study 2 – How People as Icons or Emblems Drive Perceived Feasibility of Solutions

The second study moved from actual solutions, albeit general ones, to individuals who represent prospective problem solvers. The underlying thinking was that although people may not ‘know’ what solution to a problem ‘feels right’, they may have a feeling of WHO can solve their problem. Some of the thinking behind Study 2 comes from the notion that there might be ‘archetypes’ which emerge, based upon those who are perceived to be able to solve the problem [19,20].

Following the same Mind Genomics approach of a topic, four questions, and four answers to the questions, we did the same type of study. We begin with the self-profiling classification, the introduction to the topic, and the five-point anchored rating scale:

a. A set of self-profiling questions, including age, gender, and the third question below

Which political description fits YOU best?

1=Old time Republican 2=Trump Republican 3=Democrat 4=None

b. The topic but the rating scale and the answers changed to fit the issue of solution providers, rather than solutions themselves:

What will happen when these people work together to solve this problem: Economic Gap: Rich people get richer, everyone else falls behind

RATE1=Cannot cooperate … and … No real solution will emerge

RATE2=Cannot cooperate … but … Real solution will emerge

RATE3=Honestly cannot tell

RATE4=Can cooperate … but … No real solution will emerge

RATE5=Can cooperate … and … Real solution will emerge

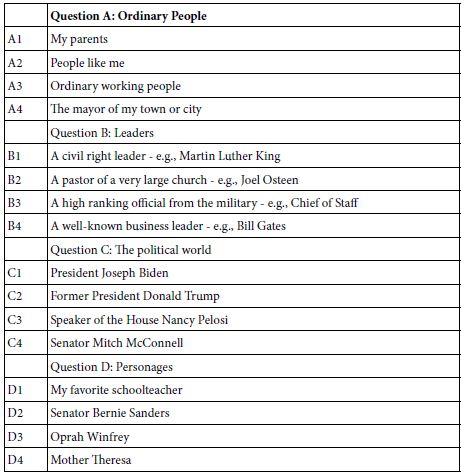

This time, however, we replace the questions and answers with those in Table 6.

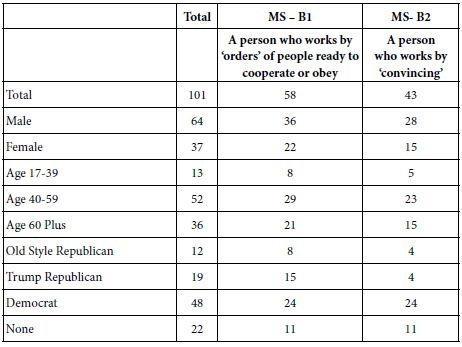

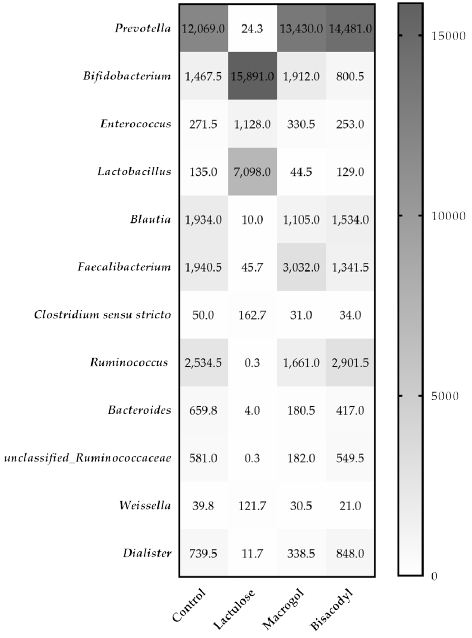

The analysis for Study 2 on People as icons or emblems was done in precisely the same fashion as was done with Study 1 on problem solutions. Thus, the two studies can be compared, at least in their general morphologies, regarding the number and magnitude of coefficients emerging as strong drivers, the nature of the mind-sets.

Table 6: The four types of emblematic problem solvers, and four specific people or groups for each type.

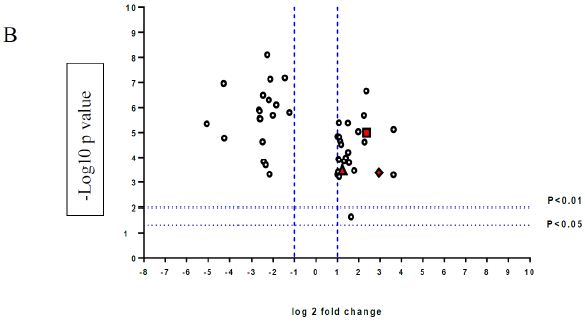

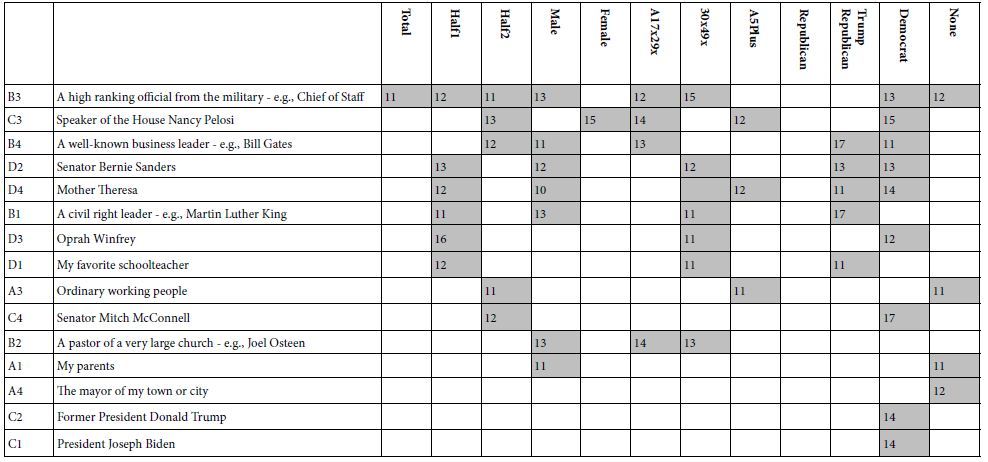

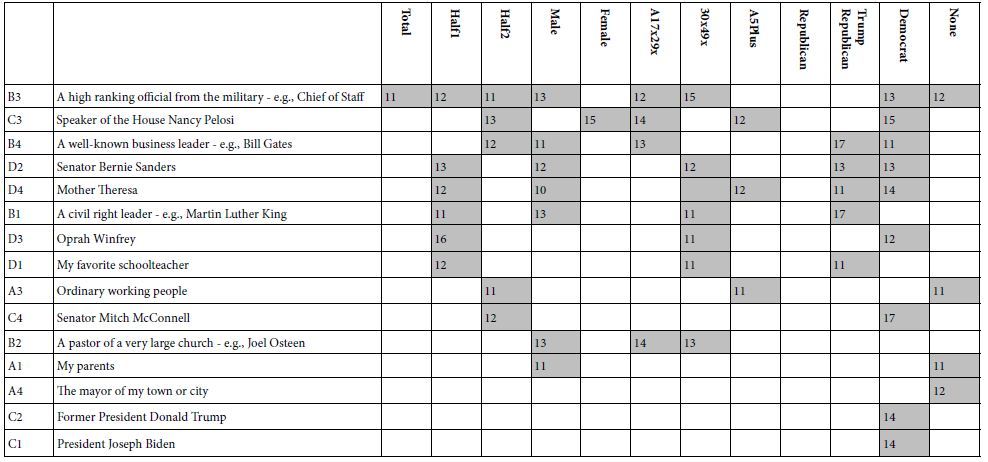

In contrast to the relatively sparse number of very strong performing elements for actual, albeit general solutions (Table 2), putting people in as problem solvers, and building models for RATE5 versus elements (no additive constant) shows many more strong elements (Table 7) The stronger performers are the ‘usual suspects. What is remarkable is that at the time of this study, when President Biden was doing reasonably well at the polls, and there were no looming disasters, President Biden was seen as a problem solver only by those who called themselves Democrats. Surprisingly, so did former President Trump, and only among Democrats. He scored poorly everywhere else.

Table 7: Strong performing elements by element and key self-defined subgroup. Only coefficients of 11 or higher are shown.

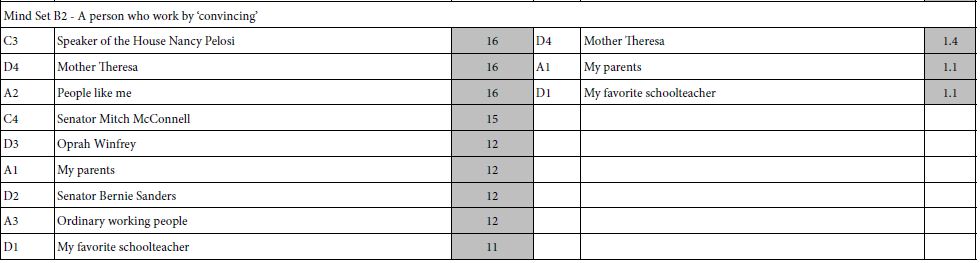

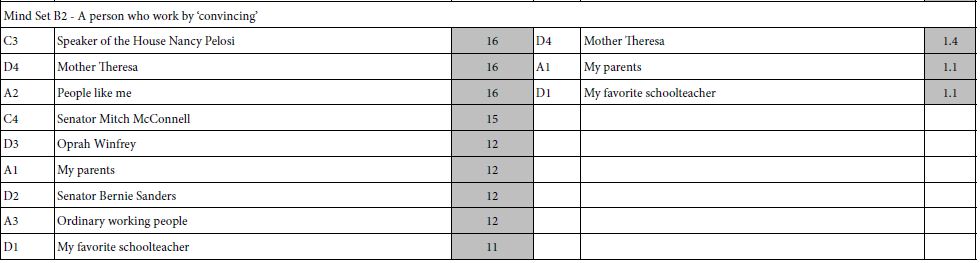

The clustering of respondents on the basis of the pattern of coefficients for RATE5 (RATE5=Can cooperate … and … Real solution will emerge) produced some strong surprises. First, no elements scored strongly on RATE1 (Cannot cooperate … and … No real solution will emerge) nor on RATE3 (honestly cannot tell). The failure to score strongly on these two response points suggests that people ‘know’ who they believe and trust, but their critical thinking may stop there. The data suggest an asymmetry in thinking between positives (people who are respected and probably liked), and negatives (people who are disrespected and probably disliked). Furthermore, only two clusters or mind-sets were needed. A three-cluster solution revealed two quite similar mind-sets, differing only in one of two elements.

Table 8 shows the strong performing elements for RATE5, and for response time, by total panel, and by the two mind-sets emerging from study 2. The important thing to notice is the set of high coefficients for RATE5 meaning that the respondents feel strongly about their answers, AND the short response times. There is very little ‘shock value’ of people, except Mother Theresa, who would not be typically thought of as a problem solver.

Table 8: The strong performing elements for RATE5 and for Response Time (RT) for study 2, with the elements being people and the rating scale being ability to cooperate and solve the problem. RATE1 and RATE3 generated virtually no strong performing elements.

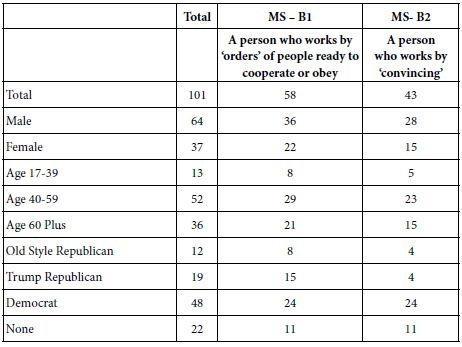

The group membership is more interesting for this second experiment (Table 9). The self-proclaimed Democrats appear equally in the two mind-sets, Mind Set B1 (working through orders) and Mind-Set B2 (working by convincing.) The self-proclaimed Republicans (both regular and Trump Republicans) appear far more frequently in Mind-Set B1 (working through orders).

Table 9: Distribution of the respondents across the three mind-sets for study 1 (Icons, Emblems).

Discussion and Conclusion

The original motivation for these studies was an interest how we think about solving social problems. The approaches to problem solving generally talk about strategies, about success stories. The strategies and success stories are so individuated that they either lack flavor entirely because they are generic (viz., strategies, such as points about solving issues), or they are so specific as to leave one wondering what to do. Furthermore, a glance at the literature about problem solving for social solutions did not bring up the role of the individual thinker, but rather the role of the situation, and the role of the expert.

The objective here was to approach the topi of problem solving of social issues from two angles, first specifics and then individuals. The specifics make sense; they are types of actions that can be taken to solve a problem. Which ones would work in the case of certain social issues, of which the economic inequality described here is one of them?

In a previous paper author Kover and Moskowitz introduced the idea of Projective Iconics, doing so within the realm of Mind Genomics [9]. The idea was to move beyond the rational to the emotion in the assessments of problems and solutions. The traditional methods for dealing with problems appeared to be all rational, left brain oriented with the utility of solving the problem (soft benefits), or harder, more economically measurable benefits. The test stimuli were always problems, the solutions were generally tangible, except for some feelings, and the evaluation was rational.

A different way had to be developed, one which would encompass something deeper than rational solutions, the act. We were taken with the adage than investors often say that they bet on the jockey, not on the horse. That is, it is the person leading the solution might be just as important as the solution itself. In that way, was born the version of Mind Genomics used here, labelled Projective Iconics. Rather than having solutions, we have combinations of problem solvers would that approach work?

Study 1 using the standard solutions suggests that people can evaluate good versus poor solutions. That is, across the set of respondents there are s number of solutions which clearly are not perceived to work, viz., RATE1, and another set of solutions which may or may not work, but people cannot decide. And, of course, quite a number of solutions which ae believed to work, especially when the total panel is broken out in subgroups. There are also a great number of solutions which are deemed not to work.

Study 2 upends the pattern, by suggesting that when we move from concrete solutions to icons on whom people can project their feelings, we are able to identify people or groups who can solve the problem but find it hard to assign people to groups who cannot solve the problem.

The conclusion here is that there is a profound difference in the way we think about the solution to problems, with far more concreteness when we talk about the actual solution, and far emotion when we talk about the problem solvers themselves.

References

- Durham Y, Hirshleifer J, Smith VL (1998) Do the rich get richer and the poor poorer? Experimental tests of a model of power. The American Economic Review 88: 970-983.

- Kotler PT, Lee NR (2009) Up and Out of Poverty: The Social Marketing Solution. Pearson Prentice Hall.

- Baumann S, Majeed H (2020) Framing economic inequality in the news in Canada and the United States. Palgrave Communications 6: 1-11.

- Kover A, Bejarano LER, Moskowitz H (2021) Social and business problems through the lens of projective iconics: Introducing a new systematics to understand and quantify perceptions of social issues. Psychology Journal Research Open 3: 1-9.

- Wright G (2018) The political implications of American concerns about economic inequality. Political Behavior 40: 321-343.

- Babu S, Pinstrup-Andersen P (2007) Social innovation and entrepreneurship: Developing capacity to reduce poverty and hunger. Twenty twenty (2020) focus brief on the world’s poor and hungry people/International Food Policy Research Institute (IFPRI).

- Knapp MS, Turnbull BJ, Shields PM (1990) New directions for educating the children of poverty. Educational Leadership 48: 4-8.

- Thorbecke E, Charumilind C (2002) Economic inequality and its socioeconomic impact. World development 30: 1477-1495.

- Kover A, Moskowitz HR, Pagajorgji P (2021) The Fraying of America, in Review.

- Stroh DP (2015) Systems thinking for social change: A Practical Guide to Solving Complex Problems, Avoiding Unintended Consequences, and Achieving Lasting Results. Chelsea Green Publishing.

- Cliff N (1983) Some cautions concerning the application of causal modeling methods. Multivariate Behavioral Research 18: 115-126.

- Moskowitz HR (2012) ‘Mind Genomics’: The experimental, inductive science of the ordinary, and its application to aspects of food and feeding. Physiology & Behavior 107: 606-613.

- Moskowitz HR, Gofman A (2007) Selling Blue Elephants: How to Make Great Products that People Want Before They Even Know They Want Them, Pearson Education.

- Green PE, Krieger AM, Wind Y (2001) Thirty years of conjoint analysis: Reflections and prospects. Interfaces 31: S56-S73.

- Gofman A, Moskowitz H (2010) Isomorphic permuted experimental designs and their application in conjoint analysis. Journal of Sensory Studies 25: 127-145.

- Milutinovic V, Salom J (2016) Mind Genomics: A Guide to Data-Driven Marketing Strategy. Springer.

- Salom J (2021) Mind Genomics with big data for digital marketing on the internet. Handbook of Research on Methodologies and Applications of Supercomputing, 282-289. IGI Global.

- Likas A, Vlassis N, Verbeek JJ (2003) The global k-means clustering algorithm. Pattern recognition 36: 451-461.

- Harootunian JA, Quinn RJ (2008) Identifying and describing tutor archetypes: The pragmatist, the architect, and the surveyor. The Clearing House: A Journal of Educational Strategies 82: 15-20.

- Bradshaw TK (2007) Theories of poverty and anti-poverty programs in community development. Community Development 38: 7-25.