Abstract

The paper presents the use of an emerging science, Mind Genomics, to understand a practical aspect of daily life: what motivates a person to donate to a specific charity. Beyond the knowledge of specific messages which are deemed to be potentially effective as a stimulus to donation, the paper shows how knowledge of a specific end-use can inform us about the mind of a person for a more general problem—how understanding the messages for donation drives a deeper understanding of human motivation. The paper moves from inexpensive pilot tests, through an affordable experiment, and onto the creation of a tool to assign new people worldwide to the proper groups, so they can receive the appropriately targeted messages.

Introduction

Knowing What to Say to Donors to Encourage Giving

In today’s world, departments of development for various organizations have become increasingly important and active. One is inundated daily by requests for donations for all sorts of causes, ranging from simple letters from individuals to sophisticated outreach including brochures and other presentations with information intended to tap one’s emotions and open one’s wallets. Most appeals from organizations appear to be ‘on point,’ with the proper phrases, the proper images, and so forth [1-3].

Approaches to Science – Idiographic versus Nomothetic

Today’s culture of science drives research towards large samples and well-defined stimuli. Despite the fact that a great deal of science is exploratory, the majority of studies published would have us believe that the studies are following the hallowed dicta of philosopher of science Karl Popper, invoking the hypothetico-deductive system, creating a hypothesis, and then falsifying it. The editors of major journals look for breakthrough work, combining a robust combination of novelty and familiarity. Such work is not common, although it occasionally surfaces. The evolving culture of science focuses on extensions of today’s state of knowledge as represented in the existing scientific literature. The typical phrase is ‘plugging holes in the literature,’ or ‘answer a call from the literature.’ Scientific rigor is as much rigorous statistics as rigorous thinking. The published work must convince by virtue of statistical differences, not by daring challenges which advance science. Despite what is promoted as scientific ‘doctrine,’ today’s scientific world frowns upon these new directions, however, when the content of journals and the reactions of reviewers are studied in detail. A quandary arises when the research is meant to explore a topic rigorously with good underlying design but with affordable samples, with the goal to be used for practical ends while truly adding to knowledge of a topic. Can this effort be called science? Typically, these problems emerge in the social and behavioral sciences, but less frequently in the harder sciences.

The focus of this paper is how one can quickly, inexpensively, and rigorously uncover the nature of the donor’s mind for a specific end recipient, that recipient being Children’s Cancer Center (name disguised to preserve confidentiality). The objective is to support children with cancer by addressing their medical, social, and psychological needs, as well as their family’s challenges. The problem is to discover what type of messages are likely to drive a person to donate. The problem is a practical one with a limited scope, specifically Children’s Cancer Center’s donations, but the learning which emerges from the study is relevant to an understanding of other communications driving support for a given charity. The empirical part of this paper shows the two steps followed to discover what to say to potential donors about Children’s Cancer Center. The combination of the two studies may be viewed as a discussion of ‘method,’ so-called methodological research. The specific findings of the second study, which is larger, but still small in terms of general practice, show what can be discovered for practical use.

About Children’s Cancer Center

Data from the World Health Organization (WHO) and the National Cancer Institute reveal that, in the United States, cancer is the leading cause of death by disease past infancy and will lead to the deaths of approximately 1,190 children in the U.S. in 2021. Further, As of January, 2015, the most recent data readily available, The National Cancer Institute reports that there are 429,000 survivors of childhood and adolescent cancer (diagnosed at ages 0 to 19 years) alive in the United States, and these survivors face serious medical problems during and after the acute phase of their disease (National Cancer Institute, 2018, 2020) [4,5].

Childhood cancer is a global issue. According to St. Jude Children’s Research Hospital’s website, cancer is diagnosed each year in about 175,000 children ages 14. The World Health Organization reports that more than 300,000 new cases are diagnosed annually in children ages 0-19. The number of actual cases is probably greater, because children in low-income countries are not likely to be included as part of the count. As Alex’s Lemonade website points out, “globally, cancer stole 11.5 million years of healthy life away from children in 2017.” This is because of life years taken away from kids who die, as opposed to a 90-year-old adult who dies of cancer and has very few life years left (Alex’s Lemonade, 2020) [6].

Despite the global prevalence of childhood cancer and the death rates associated with it, now 80% survival rates for US children but only 20% globally, only 4% of US government funding in the cancer sector is directed towards pediatric cancers. This has been challenged by pediatric cancer activists for years. A 2015 article by Kristin Connor in the Washington Examiner sheds light on the logic behind why our government doesn’t increase funding for childhood cancer:

“…cancer research funds are driven by the number of people — of any age — who have the disease. And, of course, adults, with decades of exposures and behaviors, experience cancer in much greater numbers than young children. This approach therefore seems like the “democratic” way to distribute federal money. Yet it doesn’t do much for the more than 15,700 children diagnosed each year with cancer, and the more than 40,000 children undergoing cancer treatment each year all across the United States. But instead of looking at the number of annual diagnoses, perhaps we should consider the number of life-years potentially saved. For each child with cancer, on average, as many as 71 potential life years might be saved. That’s an important factor that is not being considered when funding allocation decisions are made.” [7].

Despite great progress in US survival rates (84% of children diagnosed with cancer are alive at least five years after diagnosis), 16% are still dying AND those who do survive for five years are not necessarily cured, and many of them suffer from long-term side effects from their illness and associated treatments. According to Alex’s Lemonade, “Children who were treated for cancer are twice as likely to suffer chronic health conditions later in life versus children without a history of cancer.”

Some reason for optimism comes from the WHO: “most childhood cancers can be cured with generic medicines and other forms of treatments including surgery and radiotherapy. Treatment of childhood cancer can be cost-effective in all income settings.” Early intervention is critical to improving pediatric cancer outcomes. The WHO also calls for childhood cancer data systems, which are “needed to drive continuous improvements in the quality of care, and to drive policy decisions.” Donating to organizations like Children’s Cancer Center supports those factors that will lead to improved outcomes around the world. With the WHO’s statement that “the most effective strategy to reduce the burden of cancer in children is to focus on a prompt, correct diagnosis followed by effective therapy,” supporting an organization like Children’s Cancer Center is critical to reducing death rates of children worldwide [8].

The Mind Genomics Approach

Mind Genomics is an emerging science with roots in experimental psychology, sociology, consumer research, and statistics, respectively. The objective of a Mind Genomics study is to understand the messages for a topic which drive a specific response, such as ‘Dislike/Like,’ ‘Not interested/Interested,’ ‘Will Not donate/ will donate,’ ‘Will pay a certain amount,’ ‘expected to feel a certain way,’ and so forth. The purview of Mind Genomics is everyday life and the expected decisions that people make when they are presented with messages about a specific, granular, situation, of the type that would confront them daily. The process of Mind Genomics, the intellectual underpinnings, the statistics, and business-relevant patents have been documented extensively, and need not be repeated in their specifics. The reader is directed to a representative list [9-11]. Mind Genomics grew out of the need to create a new vision of science, one studying the behavior of the everyday, from the viewpoint of experimentation, rather than observation. Anthropology already studied individual cultures and behaviors in depth, with recent efforts attempting to move from purely descriptive to quantitative [12]. Sociology already studies everyday behavior but does not conduct experiments, and looks for general rules in everyday behavior, rules which are ‘nomothetic,’ dealing with generalities. Social psychology moves more closely into the world of the mind but again deals with issues of nomos. Social psychology is not experimental, and while it may deal with ordinary daily behavior, it attempts to provide a broad sweep of the behavior of people, rather than focusing on the topic itself. The topic of the study is only a means to understand the person. In the above disciplines, researchers focus on the person, using the normal situation to understand the person.

In contrast to other disciplines, Mind Genomics focuses on the specifics of the situation, using the person and the rules of judgment to understand. Thus, the learning is about the specifics of daily life, and less so about the person himself or herself. Indeed, one might use the metaphor that Mind Genomics focuses on the situation, with the situation ‘illuminated’ through the lights of different sources. These ‘lights,’ these different forms of illumination, are the people. The ultimate objective of Mind Genomics is to create a ‘Wiki of daily experience,’ a virtual encyclopedia of daily life and the different aspects of that daily life, dimensionalized into specifics, with the data being the aspect and numbers representing the way the ordinary person feels about that specific, on some type of scale. The problem for the ‘project of science’ is what type of information is acceptable for science? That is, the project discussed has a specific objective. Does the fact that there is such an objective invalidate the science, simply because the results pertain to a specific end-user, the Children’s Cancer Center charity? Furthermore, are the results not ‘valid’ because the base size is low? Finally, what is the status of the preparatory study—a small preliminary study to identify whether there are messages which resonate? Do preparatory studies deserve a place in the research report, because they illustrate the way towards making the larger discovery, by one or a set of small, ‘trial’ experiments?

Illustrating the Process of Mind Genomics Applied to Donations

Mind Genomics has already been used to study the nature of effective communication for donations [10,13]. The objective of the study is to understand the most productive and effective way to communicate to a prospective donor to Children’s Cancer Center. The relevance of the topic, donation, and the relevance of Children’s Cancer Center in the world of charity organizations for children with cancer will become obvious from the review of today’s information about children and cancer. Thus, anything helping to understand WHAT to communicate, and to WHOM, can play a major role in the world of health care and fundraising. The ordinary process for understanding what to communicate does not invoke science, nor does it invoke foundational experiments bridging the world of science and application. The ordinary process might be either to select previous messages that ‘worked’ to drive donations, or perhaps to classify the prospective donors into different groups, based upon WHO they are, WHAT they have done in the past, or how they THINK about general topics. The short case presented here shows how a rigorous scientific approach to understand how the mind of the donor can be applied to situations where guidance is needed, rather than where one wishes to establish for a scientific proposition with reasonable certainty. The underlying world view is that even within the world of application, one can create knowledge which informs the greater science. In the case study presented here, we show how a small pair of studies, one with four respondents and a succeeding one with 50 respondents, informs the world of charitable donations, establishing patterns that can used later on as springboards either for more application or for theory building. We now move to the science of Mind Genomics, following the process, not so much to establish general rules, but rather to investigate a specific, defined situation: donation to Children’s Cancer Center Hospital. We follow a series of steps, whether the Mind Genomics study is designed to understand charitable donations in general, or to understand charitable donations to a specific cause.

Our presentation of the process shows the results from two iterations. The first iteration, with the very small base size of four respondents (n=4), will show how Mind Genomics extracts information at virtually the level of one or a few individuals, in a manner similar to the way the anthropologist or the consumer researcher extracts information from in-depth interviews with one or two people or from focus groups of three or more people. The second iteration will move on with a more quantitative study of the responses from 50 individuals, after building on the learning from the first iteration, changing some of the material, and then testing. It is important to note that the process need not be restricted to one small study followed by one larger one, but might comprise several small studies, until these sequences of ‘iterations’ provide the information which seem to be most appropriate to answer the applied question, and to provide the structured knowledge for a ‘wiki of the mind’ with respect to the topic.

Step 1: Choose a Topic

This step sounds simple, but it requires the researcher to focus on a specific topic. Choosing the specific topic is the start of critical thinking required by Mind Genomics, whether the topic is a general one of daily behavior (what makes a person donate to a charity?) or a specific one (what makes a person want to donate to Children’s Cancer Center Hospital?).

Step 2: Create Four Questions Which ‘Tell a Story,’ Pertaining to the Topic

The iterative nature of Mind Genomics ensures that the researcher need not worry that the questions are correct. Indeed, part of the underlying world view of Mind Genomics is that science should be exploratory.

Step 3: Create Four Answers to Each Question

Again, these answers need not be the correct answers. The ability to iterate, to run a number of these small experiments, generate data which guide the researcher to better questions and better answers.

Step 4: Select a Rating Scale

The rating scale can be 5, 7 or 9 points. The actual number of scale points is left to the discretion of the respondents, as is the rating scale. There is no right or wrong scale. The topic of questions and scales has been a focus of researchers for a century. The pragmatic side of Mind Genomics is that the scale should be simple. The scale for this type of question (not donate vs. donate) should be simple to understand, anchored at both ends. An odd number of scale points is easier to work with when there is the possibility of a neutral point.

Step 5: Launch the Study and Get the Results Fully Analyzed within 90 Minutes

The process obtains respondents through a panel service (Luc.id), with the Mind Genomics platform automatically analyzing the data and returning a complete report, the entire process typically taking less than one to one and a half hours.

Step 6: Present the Appropriate Vignettes to the Respondent, Vignettes Created for That Respondent by the Permuted Experimental Design

Record the rating on the anchored 1-9 scale, and record the response time (consideration time), operationally defined as the number of seconds from the appearance of the vignette on the screen to the actual rating assigned by the respondent. Each respondent evaluates the appropriate set of vignettes to constitute an experimental design, allowing subsequent powerful analyses. Each respondent evaluates a unique set of combinations of messages, so that across the set of respondents the evaluations cover many of the possible combinations, rather than covering a few combinations, but with precision. The learning will be in the stimuli, not in the precision of the measurement.

Step 7: Obtain Data Analyzable Both at the Level of the Individual and at the Level of the Group, Respectively

Each respondent evaluates a full experimental design, analyzable at the level of the individual respondent. For the design comprising four questions and four answers (elements), the design prescribes 24 combinations (vignettes). Each vignette comprises 2-4 elements, no more than one element or answer from any question. The design ensures that each element appears 5x, uncorrelated with any other element; The experimental design is maintained, but the combinations are changed according to a permutation scheme [14,15]. Thus, the combinations cover more of the ‘design space’ than the usual approach using experimental design. The underlying rationale is that it is more productive to test many possible combinations with underlying variability (noise) in each measurement than to limit oneself to a few combinations, measuring each point in the design with many replicate measures to average out the variation. In short, the argument by Mind Genomics is that knowledge emerges from scope with modest precision at each point (the big pattern emerges), rather than from precision with narrow scope. This is the key tenet of Mind Genomics: scope is better than precision, at least in the early explorations of a topic.

Step 8: Convert the Rating Scale in Two Ways

The first transformation is ‘Top 3’ defined as a transformed value of 0 when the original rating was 1-6, defined as 100 when the original was 7-9. The first transformation focuses on what ‘drives’ a person to select ‘donate.’ The second transformation is ‘Bot 3’ defined as a transformed value of 0 when the original rating was 4-9, defined as a transformed value of 100 when the original rating was 1-3. The second transformation focuses on what ‘drives’ a person to select ‘will not donate.’ To all transformed ratings a small random number was added (<10-5) to ensure variation in the transformed rating, and thus to ensure that the OLS (ordinary least-squares regression) will ‘work,’ and not ‘crash.’ OLS regression requires variation in the dependent variable. The addition of the small random number ensures that variation without materially affecting the results.

Step 9: Cluster the Individual Respondents Based Upon the Pattern of Their 16 Coefficients for Top3

The clustering is done using k-means clustering with the measure of distance being (1-Pearson Correlation), viz., [16]. The Pearson correlation coefficient shows the strength of a linear relation between two sets of measures. When the relation is perfectly linear, increases in one measure correspond to precise increase in the other measure. There is no scatter, the Pearson correlation is +1, and the distance is 0 (1-1=0). In contrast, when the relation is perfectly inverse, increases in one measure correspond to precise decreases in the other measure. Again, there is no scatter, the Pearson correlation is -1, and the distance is 2 (1–1=2). The clustering program generates two, and then three groups, called mind-sets, because the clusters represent groups who attend to the elements or messages in different ways. We select that cluster solution (the array of mind-sets) which tells the most obvious story (interpretable), and which comprises the smallest number of segments (mind-sets). For the data in this study, the three-mind-set solution was easier to understand.

Step 10: Create the Model for All Appropriate Data from the Respondents from Each Key Subgroup

Each group (Total, three Mind-Sets) generates three models or equation; Top3 (drivers of positive response), Bot3 (drivers of negative response), and RT (response time, or consideration time, measure of engagement with the material, whether the response to the element was positive or negative).

The model is a simple weighted, linear equation of the form:

Top3 (or Bot3) = ko + k1(A1) + k2(A2) … k16 (D4)

Response Time = k1(A1) + k2(A2) …. K16 (D4)

The additive constant k0, shows the estimated Top3 (or Bot3) response in the absence of elements. The additive constant can be thought of as a baseline response, or the underlying, fundamental likelihood of the respondent to ‘donate’ (Top3) or ‘not donate’ (Bot3). The additive constant is not meaningful for response time RT, since in the absence of elements there is nothing to which one can respond.

Step 11: Assign a New Person to One of the Mind-sets by Means of a Short Questionnaire, the PVI, Personal Viewpoint Identifier

The PVI assigns a NEW person to one of the mind-sets, and by so doing expands the scope of the small-scale studies to practical use, whether to create a more effective campaign (application), or to understand the distribution and possibly nature of the people in the different mind-sets. This adds to our general knowledge of the minds of people regarding messages relevant to donations (science).

Results

The Two Studies

To illustrate the value of small studies and what can be learned with a sequential approach requiring 2-3 days, we present the results of two studies designed to understand what messages may work for a campaign. The project deals with messaging to drive donations for Children’s Cancer Center, a hospital devoted to pediatric cancer (name of actual hospital disguised to maintain confidentiality). To make the topic general, the actual study was conducted among the general population to uncover the messages which would appeal the general population, not simply appeal to previous donors to Children’s Cancer Center.

The knowledge development was done in two phases. The first phase, or experiment, can be considered a pilot study with 10 respondents, sufficient to provide deep insights. The key difference between a pilot study of 10 respondents and a larger scale study of 40-50 respondents, or even a much larger scale study of 100-200 respondents, is simply the ability to identify different groups in the population and study the pattern of their responses.

Study 1: Preliminary Learning through a ‘Mini-Study’

As noted above, the Mind Genomics project begins with the topic (donating to Children’s Cancer Center specifically, or a cancer hospital for children in general). The next step requires the researcher to formulate the four questions that ‘tell a story.’ The questions emerging from the initial discussion tell such a story. They may not be the only questions, but in an exploratory study the objective is to learn just ‘what works.’ The four questions are:

A. Question A: What is it like to be a pediatric cancer patient?

B. Question B: Why is it important to support Children’s Cancer Center?

C. Question C: What are the outcomes for children when you donate?

D. Question D: How do you give your donation?

The study was executed with 10 respondents chosen from a large group of panel participants recruited by Luc.id, Inc., based in Louisiana, a provider of panel participants for on-line studies. Each respondent evaluated a different set of 24 vignettes, constructed according to Step 6 above. With as few as one respondent the Mind Genomics study generates meaningful data, readable at the level of that single respondent. With 10 respondents, and occasionally even as few as three or four, patterns rapidly emerge, patterns which are relevant for the respondents, but which may or may not be projectible to the population at large.

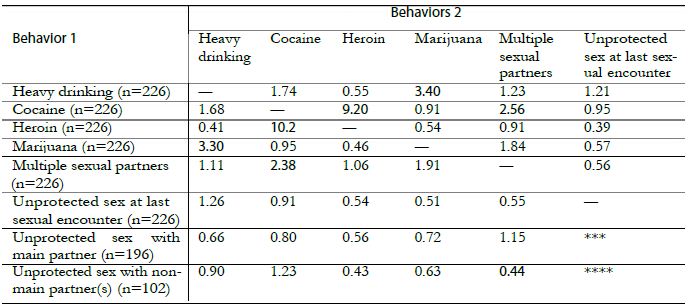

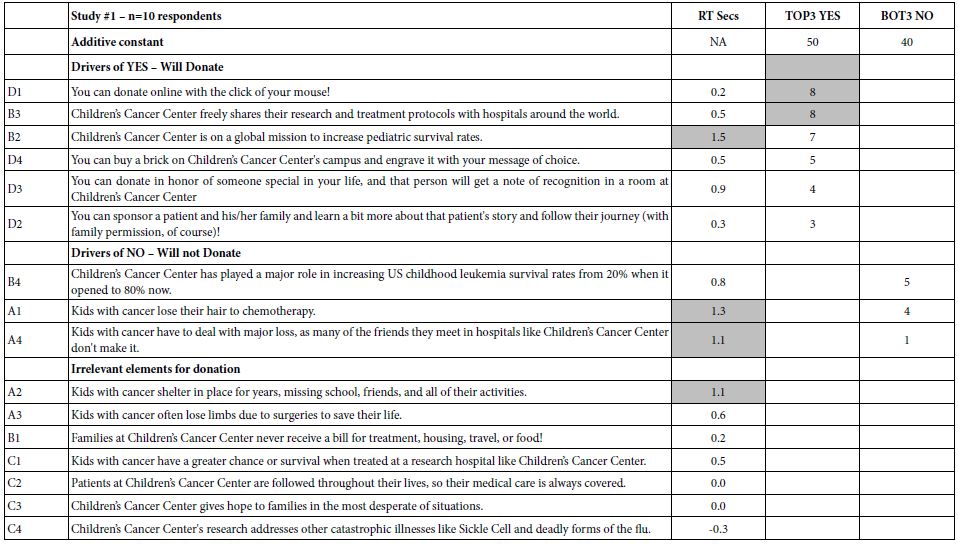

Table 1 shows the coefficients for the response time, the positive coefficients for the positive responses (I will donate), and the positive coefficients for the negative responses (I will not donate).

Table 1: The four questions, four answers to each question and the coefficients from the grand model relating the 16 elements to the binary transformed rating. To help the underlying patterns emerge, only the positive, non-zero, coefficients are shown for Top3 and for Bot3. The response times are shown for all elements, but only the response times of 1.1 seconds are shown, those driving ‘engagement’.

The response time gives a sense of the elements which most engage the respondent. Even with a small base size of 10 respondents, the data from the deconstruction of the ratings into the contribution of the elements gives a sense of the nature of elements that effectively engage. Those elements talk about the children, and survival. The elements may not ‘drive expected donations,’ but they do engage as shown by the long response time (consideration time). Moving on to the ratings, or more specifically the transformed ratings, Table 1 suggests that the additive constant, the proclivity to donate or not to donate ranges between 40 and 50. In the absence of elements which provide specific information, there is no dramatic drive to donate or not to donate, at least for these randomly chosen respondents. What is more important, however, is that among the 16 elements or, the messages, only two reach significance (coefficients of 8 or higher).

You can donate online with the click of your mouse!

Children’s Cancer Center freely shares their research and treatment protocols with hospitals around the world.

The two elements have little in common, suggesting that there is probably no single strong message. It is the nature of researchers to continue looking. These data suggest no ‘magic bullet.’ They do suggest that if there are any ‘magic bullets,’ they may be found in different mind-sets in the population, if such mind-sets can be identified. It is at this point that one can begin to formulate hypotheses about the psychology of donations. The hypothesis emerging here is that ‘painting a graphic word picture’ of the child will engage attention. The science of Mind Genomics has now enriched our thinking about the psychology of donations and generosity, suggesting that graphic design of the recipient is something to consider. The data suggest a further opportunity to understand the nature of the portrait being painted.

Study 2: Identifying the Underlying Structure of What Works for Donating to the Hospital

Study 1 constituted the first foray into the topic, executed with 10 respondents. Although 10 respondents are not often considered to be sufficient to establish results, a base of 10 respondents from one or two focus groups is acceptable when considered to be an exploratory step. Thus, we considered Study 1 to be exploratory, providing information in a disciplined way, but with simply too few respondents.

Here again are the questions from Study 1

Question A: What is it like to be a pediatric cancer patient?

Question B: Why is it important to support Children’s Cancer Center?

Question C: What are the outcomes for children when you donate?

Question D: How do you give your donation?

Based upon the patterns of responses, here are the four revised questions. The key change is Question D, and of course the text of the elements themselves.

Question A: What is it like to be a pediatric cancer patient (why would you want to help)?

Question B: Why is it important to support Children’s Cancer Center?

Question C: What are the outcomes for children when you donate?

Question D: What would inspire you to give?

The second study was conducted with 50 respondents, of which the data from 48 respondents were retained. The remaining two respondents did not provide age or gender, and so their data were eliminated.

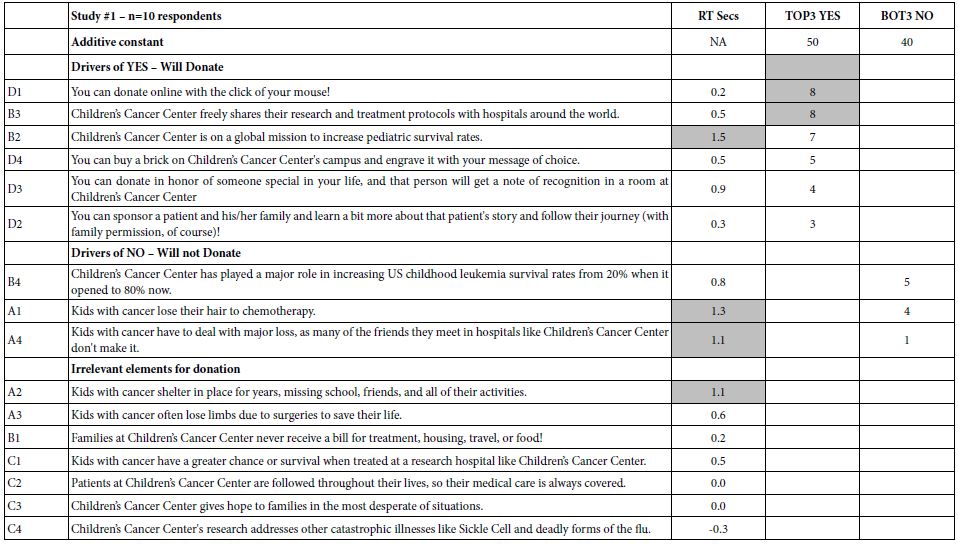

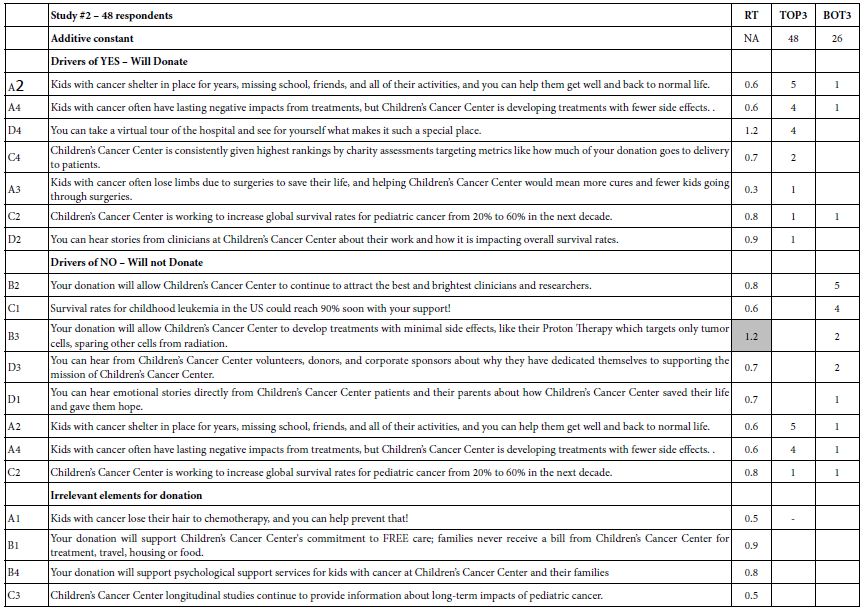

Table 2 shows the same type of data as does Table 1, this time for the new set of respondents, and the new set of elements. Once again, each respondent evaluated a unique set of 24 vignettes, constructed by experimental design, so that the data can be analyzed down to the level of the individual respondent. This strategy, so-called ‘within-subjects design’ ensures that the data can be further deconstructed into subgroups called ‘mind-sets,’ based upon the patterns of the coefficients for each respondent. At first glance, the data reaffirm the previous finding from Study #1 that there are no elements which strongly driving expected donations, when the topic is associated with Children’s Cancer Center. One might consider this a failure when the objective is to discover the so-called ‘magic bullet,’ the message that will work for everyone. The result might be the continued search for this ‘magic bullet’ in successive efforts, only to realize in the end that there is no ‘magic bullet,’ or if there is, no one has any idea about what specifically it is and how to express it. At the practical level, the effort will be seen to have been wasted. There will be no science of communication about charitable contributions and how people feel. The unsatisfactory conclusion, soon to be discarded is ‘no business results, no contributions to the science of people, no additional knowledge for science of charity communications.’

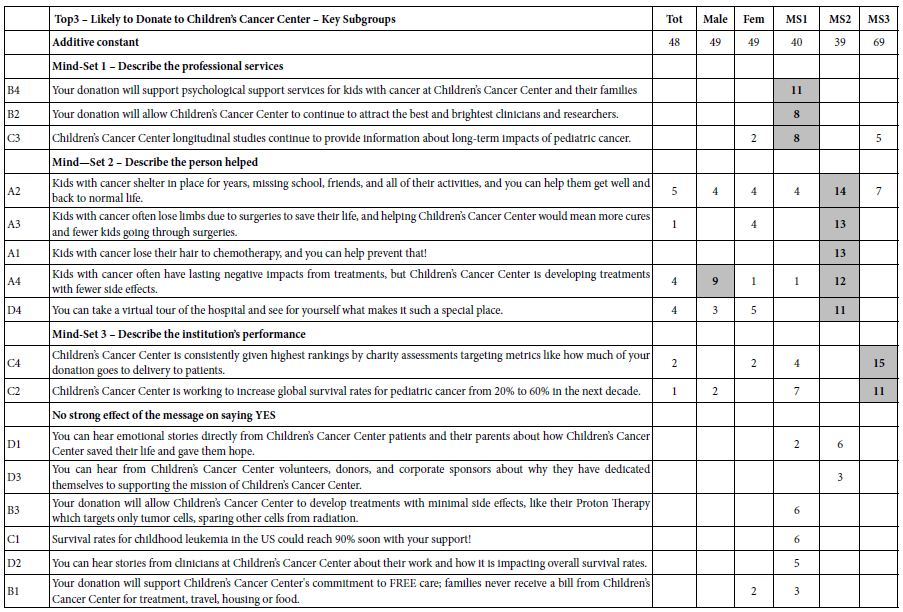

Table 2: Results from the total panel from Study #2.

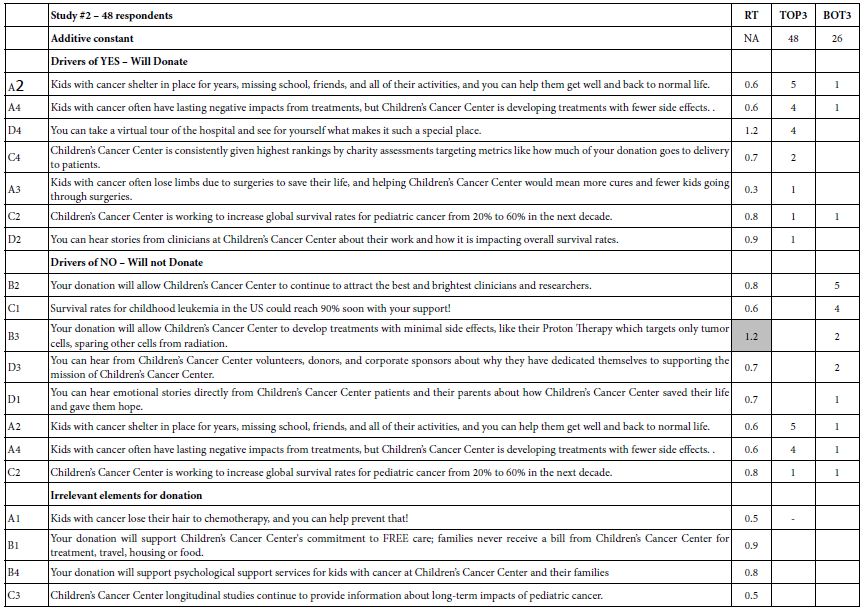

The picture changes, and significant learning for practical application and for foundational knowledge emerges, when one dives more deeply into Mind Genomics and discovers mind-sets. In Mind Genomics, the continuing data suggest the existence of what could be called mind-sets, different patterns of ideas which are interpretable in the form of a ‘story,’ patterns that seem to attach themselves to people. In the world of Mind-Genomics, considering people simply as ‘protoplasm which responds,’ there emerge groups of ideas which separately drive strong responses. People are the carriers of these ideas. People allow these groups of ideas to emerge. A person typically falls into a specific mind-set for a topic and not into the other mind-sets for the same topic. When we look at the data through the lens of mind-sets, using the computational process outlined in Steps 9 and 10 above and doing the computation on the Top3 (positive responses), we emerge with three new-to-the-world mind-sets, shown in Table 3 for Top3 (positive response – likely to donate), and in Table 4 for Bot3 (negative response – not likely to donate).

Table 3: Drivers of positive responses to messages, showing total panel, gender, and the three emergent mind-sets based on clustering using Top3.

To strengthen the scientific aspect of the results—the learning which is meant to be foundational rather than simply a direction for messaging to raise money—we include gender, as well, comparing the responses of males and females. Table 3 suggests three mind-sets. It is in the mind-sets that the strong elements emerge, elements with coefficients of +8 or higher.

a. There are some positive elements by gender, but no strong performers at all. Both male and female respondents are modestly interested in donating (additive constant=49)

b. Mind-Set 1 – Describe the professional services (modestly interested in donating at a basic level, additive constant=40)

c. Mind-Set 2 – Describe the person helped (modestly interested in donating at a basic level, additive constant=39)

d. Mind-Set 3 – Describe the institution’s performance (strongly interested in donating at a basic level, additive constant=69).

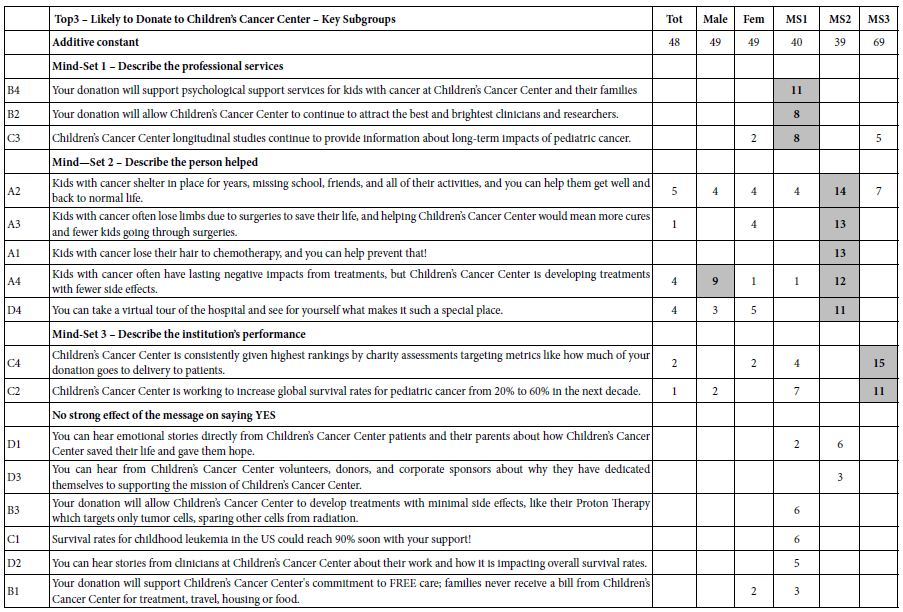

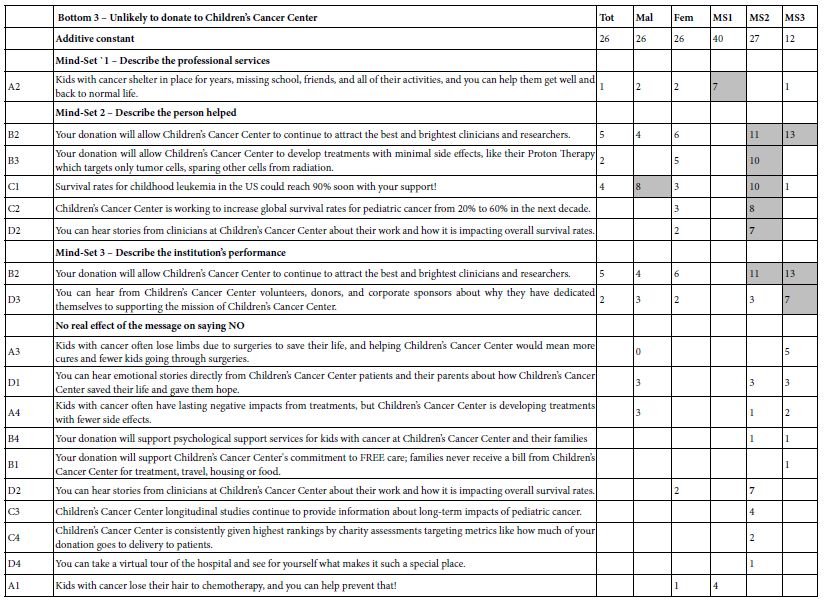

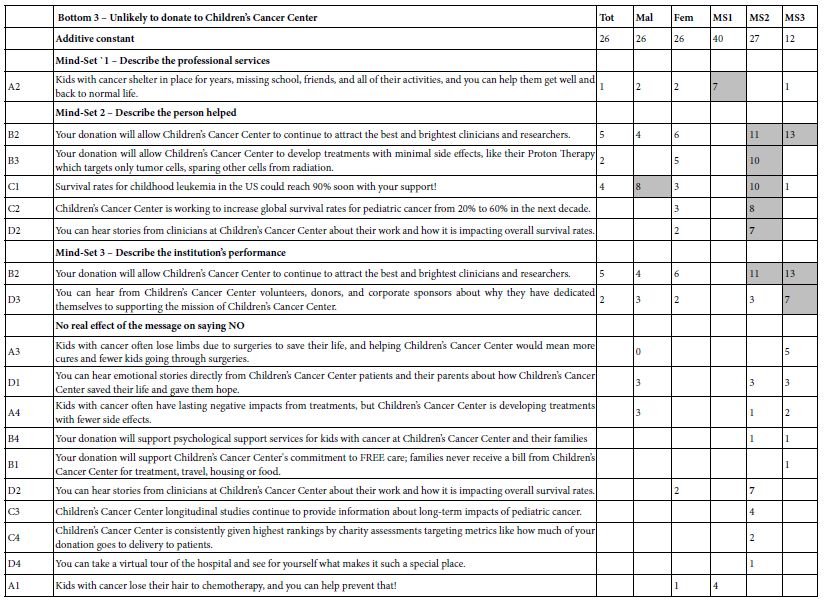

Table 4 shows the messages that should be avoided, the messages driving the response of ‘Not Donate.’ The coefficients emerge from considering only ratings of 1 and 2 as relevant on the 5-point scale, with ratings of 3-5 (neutral, will donate) as not relevant, and coded as 0. The additive constant is far lower for Not Donate than it is for Donate, meaning that people are more inclined to say that they will donate. Several messages to be used by the Center are likely to ‘backfire’, driving donors away. Mind-Set 2 is especially sensitive to the wrong messages.

Table 4: Drivers of negative responses to messages, showing total panel, gender, and the three emergent mind-sets based on clustering using Top3.

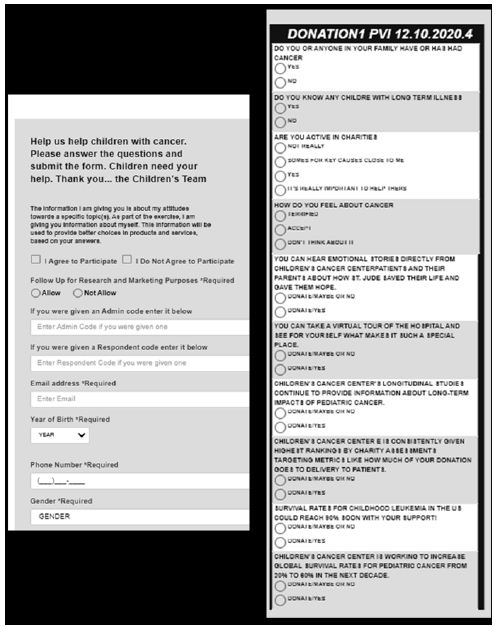

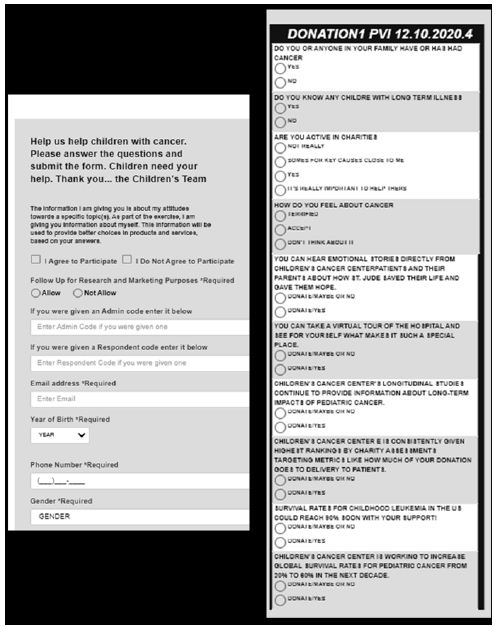

Finding these Respondents in the Population

A continuing topic in Mind Genomics is the value of a ‘next step’ beyond the already-important discovery of mind-sets. Mind-sets themselves provide a way of understanding daily life, through a new focus on the every-day and the way people differ in their typical behaviors. Yet, beyond the scientific contribution of knowledge is the remarkable potential of expanding the value of the learning, moving beyond the respondents tested in the study to the entire world. A simile is the colorimeter used to quantify colors of objects. The science of color can be developed in any location with any material. The real value of the science in terms of the ‘world outside’ is to measure the colors of new objects, not by repeating the study in which the colors were discovered, but rather by measuring the colors of the new objects using a machine in which the science has been already programmed [17-23]. The approach used in Mind Genomics is called the PVI, the personal viewpoint identifier. The objective is to use the data from Table 3 (MS1, MS2, MS3) to create a short questionnaire (six questions), on a simple to-use scale. The questions come from the actual study. The pattern of responses assigns a NEW PERSON to one of the three mind-sets. There are 64 possible patterns, each pattern mapping to one of the three mind-sets. Figure 1 shows the PVI, doing so in two parts. The left part is a short introduction, to introduce the person to the task, and to obtain optional background information. The right part is the actual PVI, including some basic questions about attitudes towards ‘giving’ and the six-question PVI. The results are forwarded to a database and can be sent to the respondents, as well.

Figure 1: The PVI, personal viewpoint identifier, based upon the second study. The PVI is located at: https://www.pvi360.com/TypingToolPage.aspx?projectid=1261&userid=2018.

Discussion and Conclusion

The empirical results are simple to discover, just by looking at the table of elements and how the elements or messages drive interest in donating. The message used in requesting should be straightforward and focus on how the organization saves and changes lives for the better. The outcome of the organization’s work, and not the process, should be the main message. One should avoid directly focusing on needs and tax breaks, respectively. Although a minority of prospective donors will care about needs or tax advantages, most people say that they will contribute when they are suitably convinced by the cause and mission of the effort and in the vision detailing how their contribution can help. It is at this point that one can begin to formulate hypotheses about the psychology of donations. The hypothesis emerging here is that ‘painting a graphic word picture’ of the child will engage attention. The science of Mind Genomics has now enriched our thinking about the psychology of donations and generosity, suggesting that graphic design of the recipient is something to consider. The data suggest a further opportunity to understand the nature of the portrait being painted. It is not important to point out major ‘learnings’ from the results, learnings which confirm or disconfirm what is known in the literature, or what is hypothesized to be the case for the psychology of donors or the psychology of children with cancer. That information is, of course, important to know for science. What is more important, however, is the ability to have at one’s disposal a tool for small-scale, iterative experimentation: Mind Genomics, a tool which returns rich information even with remarkably small base sizes, such as n=10 or even fewer. In the world of science, Mind Genomics becomes a tool bridging the gap between the idiographic (individual) and the nomothetic (the general world). Just as important, Mind Genomics becomes both a practical tool to increase donations, as well as a tool for the development of systematized knowledge, both for the current generation and for those to come—a ‘wiki of the mind.’ Finally, viewed from the grand proscenium arch of civilization, Mind Genomics provides a record of how people of a certain time, in a specific environment, and faced with known needs, think about topics— a record of inestimable value to philosophy, psychology, history, sociology, anthropology, and economics, just to name a few disciplines where knowledge of the granular is important.

References

- Cao X, Jia L (2017) The effects of the facial expression of beneficiaries in charity appeals and psychological involvement on donation intentions: evidence from an online experiment. Nonprofit Management and Leadership 27: 457-473.

- Das N, Guha, A, Biswas A, Krishnan B (2016) How product–cause fit and donation quantifier interact in cause-related marketing (CRM) settings: Evidence of the cue congruency effect. Marketing Letters 27: 295-308.

- Mejova Y, Garimella VRK, Weber I, Dougal MC (2014) February. Giving is caring: understanding donation behavior through email. In Proceedings of the 17th ACM conference on Computer supported cooperative work & social computing pg: 1297-1307.

- Childhood Cancer Survivor Study: An Overview. (2018, September 27). The National Cancer Institute. https://www.cancer.gov/types/childhood-cancers/ccss

- Childhood Cancer. (2020, Nov 7). The National Cancer Institute. https://www.cancer.gov/types/childhood-cancers

- Alex’s Lemonade (2020) Global Childhood Cancer Facts: By the Numbers. (2020, Dec 7). Alex’s Lemonade. https://bit.ly/3a49Cpl

- Connor, K. (2015, May 25). Why childhood cancer research gets shortchanged. Washington Examiner. https://www.washingtonexaminer.com/why-childhood-cancer-research-gets-shortchanged.

- Jude’s Children Research Hospital, 2020 Childhood Cancer Facts. (2020, Dec 7). St. Jude Children’s Research Hospital. https://www.stjude.org/treatment/pediatric-oncology/childhood-cancer-facts.html .

- Gabay G, Moskowitz HR (2012) The algebra of health concerns: implications of consumer perception of health loss, illness and the breakdown of the health system on anxiety. International Journal of Consumer Studies 36: 635-646.

- Galanter E, Moskowitz H, Silcher M (2011) The Price of Grace: Donations, Charities, and the Mind. People, Preferences and Prices: Sequencing the Economic Genome of the Consumer Mind pg:103.

- Moskowitz HR, Gofman A (2007) Selling blue elephants: How to make great products that people want before they even know they want them. Pearson Education.

- Williams LL, Quave K (2019) Quantitative Anthropology, A workbook. Elsevier.

- Gabay G, Moskowitz H, Gere A (2019) September. UNDERSTANDING THE DONATING MIND & OPTIMIZING MESSAGING–PUBLIC HOSPITALS. In 12th Annual Conference of the EuroMed Academy of Business.

- Gofman A, Moskowitz H (2010a) Isomorphic permuted experimental designs and their application in conjoint analysis. Journal of Sensory Studies 25: 127-145.

- Moskowitz H, Gofman A, I novation Inc (2003) System and method for content optimization. U.S. Patent 6,662,215.

- Ramasubbareddy S, Srinivas TAS, Govinda K, Manivannan SS (2020) Comparative Study of Clustering Techniques in Market Segmentation. In Innovations in Computer Science and Engineering, pg: 117-125, Springer, Singapore.

- Gofman A, Moskowitz, HR (2010b) Improving customers targeting with short intervention testing. International Journal of Innovation Management, 14: 435-448.

- Global Initiative for Childhood Cancer. World Health Organization. (2020, December 7). https://www.who.int/cancer/childhood-cancer/en/

- Health Affairs, 2020. https://www.healthaffairs.org/doi/full/10.1377/hlthaff.25.2.541

- Importance of CEO involvement in creating a culture of philanthropy in hospitals.

- Moskowitz HR, Gofman A, Innovation Inc, (2011). System and method for performing conjoint analysis. U.S. Patent 7,941,335.

- Notaro S (2020) https://bit.ly/3b7wBQi.

- Social Science Direct (2020) https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/abs/pii/S2213076415300051. Use of social media by US Children’s’ hospitals.