Abstract

People going through the United States (US) criminal justice system often exhibit multiple behaviors that increase their risk of HIV infection and transmission. This paper examined the pattern of co-occurring HIV risk behaviors among male jail detainees in the US. We conducted multivariate analyses of baseline data from an HIV intervention study of ours, and found that: [1] cocaine use, heroin use and multiple sexual partners; and [2] heavy drinking and marijuana were often co-occurring among this population. From pairwise analyses, we also found that [1] heroin and IDU [2] unprotected sexes with main, with non-main, and in last sexual encounter were mostly co-occurring behaviors. Further analyses of risk behaviors and demographic characteristics of the population showed that IDU were more prevalent among middle ages (30-40) and multiple prior incarcerations, and having multiple sex partners was more prevalent among young males younger than 30 years, African American race, and those with low education. Our findings suggest that efficient interventions to reduce HIV infection in this high-risk population may have to target on these behaviors simultaneously and be demographically adapted.

Keywords

HIV risk, Co-occurring behaviors, Correctional facilities, Male jail detainees

Introduction

Over seven million people passed through the criminal justice system in the United State (US) in year 2012 [1]. Among this population, it was estimated that about 2% was infected with HIV including those unaware of their infection [2-4] — as a contrast, the prevalence among the US adult population is around 0.3% according to the US Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC). The prevalence of HIV infection within jails and prisons was estimated to be about 3 to 6 times higher compared with that among non-incarcerated populations [4-8].

The reasons for this increased burden of HIV among populations in correctional settings are multi-factorial and include increased rates of substance abuse, mental illness, poverty and health disparities [9]. Persons who interact with the criminal justice system may be disenfranchised from health services in the community, such as screening programs. That makes the time of incarceration an important public health opportunity to provide HIV prevention and testing services and linkage to care [10-12].

The time period preceding incarceration has been shown to be characterized by increased substance use and risky sexual behaviors that increased exposure to HIV, viral hepatitis, and other transmitted diseases [13-18]. Release from correctional facilities might also be a time of high-risk of acquiring or spreading infections as persons re-entered their communities and resumed risk behaviors [19-21]. Thus, correctional-based HIV counseling and testing programs and prevention interventions may help to decrease their risk behaviors following release from the correctional environment and therefore reduce new HIV infections in this as well as the general population.

Although studies have documented prevalent (direct and indirect) HIV risk behaviors before entering jail (including heavy drinking, substance abuse, sexual promiscuity, and unprotected sex) [19-26] there is limited understanding of the interrelationships among these risk factors. To effectively target prevention interventions to persons at the greatest risk of HIV infection among this population, it is critically important to understand their risk profiles and quantify which risk behaviors are more likely to co-occur. In this paper, co-occurring behaviors are defined as behaviors that occur within certain time period (e.g. a 3 months window) and not necessarily always in the same episode (i.e. concurrently). This definition is consistent with the need of broader interventions on behaviors that are predictive of (not necessarily determinative of) each other and jointly place an individual at a higher risk of HIV infection.

In this paper, we conducted a secondary analysis of data from a study on HIV counseling and testing in jail [27]. Specifically, we used the baseline data of the study to investigate: 1) whether certain risk behaviors were co-occurring and to what extent, and 2) whether risk behaviors were prevalent among people with certain demographic characteristics.

Methods

Prior Study and Data

We previously conducted a two-arm randomized study [27] to assess HIV risk behaviors among males entering the Rhode Island Department of Corrections (RIDOC) jail and compared the efficacy of two methods of HIV counseling and testing (conventional versus rapid HIV testing) with respect to reducing post-release HIV risk behaviors. A total of 264 HIV-negative males met the study enrollment criteria, provided the written informed consent, were recruited within 48 hours of incarceration, and completed the study. The study was approved by the Miriam Hospital institutional review board, the Rhode Island Department of Corrections (RIDOC) Medical Research Advisory Group, and the Office for Human Research Protections of the Department of Health and Human Services. More details of the study are available elsewhere [27].

In this paper, we focused on data that were collected at the baseline of the study, including demographic information and self-reported HIV risk behaviors during 3 months prior to incarceration. The self-reported risk behaviors were collected using a written quantitative behavioral assessment survey on participant’s recent drinking, substance use behaviors (cocaine use, heroin use, marijuana use, injection of any drug) and sexual behaviors (multiple sexual partners, unprotected sex at last sexual encounter, unprotected sex with main partner, and unprotected sex with non-main partner). Because only data at the baseline prior to intervention randomization were used in this paper, we did not distinguish study participants by their study arms.

Statistical Analyses

We conducted three sets of statistical analyses, outlined as follows:

Analysis I

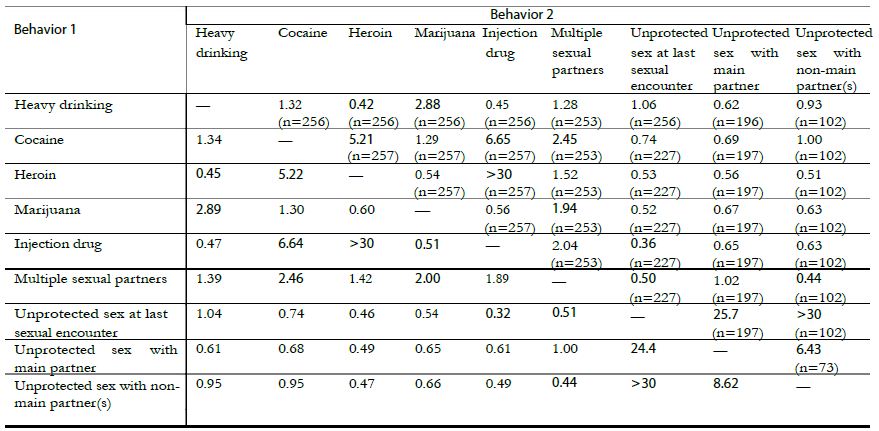

The co-occurrence of two risk behaviors (pair-wise analysis) was assessed using logistic regressions where one behavior (Behavior 1) was used as the dependent variable, and the other behavior (Behavior 2) as an predictor variable. The results are shown in Table 1. All regressions were adjusted for the following demographic covariates: age (categorized as <25; 25 ∼ 30; 30 ∼ 40; and > 40 years), race (Caucasian; Black; Hispanic; others), number of prior incarcerations (dichotomized at median: < 7; ≥ 7), length of incarceration as severity index of crime leading to incarceration (<2 wks; 2 wks ∼ 1/2 yr; > 1/2 yr), and education (did not finish high school; otherwise).

Table 1: Pair-wise association among risk behaviors.

(a) The table is not symmetric because the analyses are adjusted for the following covariates as predictors of Behavior 1: age, race, prior incarcerations, length of incarceration, and education.

(b) The numbers in parentheses are sample sizes.

(c) Bold indicates a p-value < 0.05 and italic < 0.10.

Pair-wise co-occurring risk behaviors were quantified using odds ratios (ORs), where an OR > 1 (OR < 1) suggests that the existence of one behavior was predictive of the existence (or absence) of the other behavior.

We used the available complete data for assessing risk behaviors, so the analysis sample size varied (range: 73-256 as in Tables 1 and 2). The overall missing data on risk behaviors were moderate (<5%), if we did not count systematic missingness as missing values (e.g. Missing sexual behaviors for those without sexual partner). Throughout, we made the missing at random (MAR) assumption [28]; that is, we assumed that with the same demographic profile, those who provided complete answers to the baseline questionnaire had engaged in similar risk behaviors as those who did not [29].

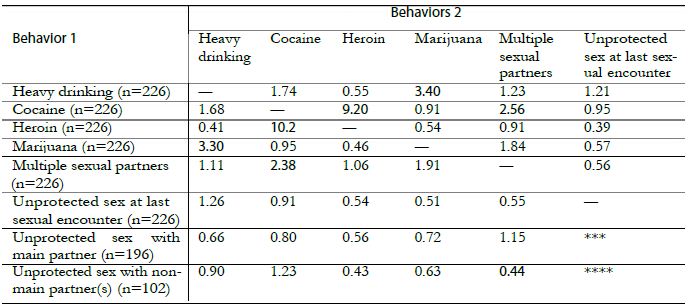

Table 2: Multivariate analyses of co-occurring risk behaviors.

(a) The table is not symmetric because the analyses are adjusted for the following demographic covariates: age, race, prior incarcerations, length of incarceration, and education.

(b) The numbers in parentheses are sample sizes.

(c) Bold indicates a p-value < 0.05 and italic < 0.10.

(d) *** “Unprotected sex at last sexual encounter” is not included as a predictor variable in the model.

Analysis II

Multiple co-occurring risk behaviors were assessed using multivariate logistic regressions where one risk behavior (Behavior 1) was used as the dependent variable and other behaviors (Behaviors 2) as predictor variables. The results are shown in Table 2. Similar to Analysis I, the co-occurring of Behavior 1 with other behaviors was characterized by ORs, which have similar interpretations except that the ORs in Table 2 are conditional ORs after accounting for all other behaviors of (Behaviors 2). Again, all analyses were adjusted for the same set of demographic characteristics as in Analysis I. When heavy drinking, cocaine, heroin, marijuana and multiple sexual partners were used as dependent variables, we excluded the risky behaviors ‘unprotected sex with main partner’ and ‘unprotected sex with non-main partner’, because they only applied to subsets of study participants with sexual partners and including them would reduce the sample size by half and reduce the analysis power. When ‘unprotected sex with main partner’ and ‘unprotected sex with non-main partner’ were used as the dependent variables, ‘unprotected sex at last sexual encounter’ was excluded from predictor variables because the later behavior strongly correlated with the former behaviors and therefore overwhelmed the associations of the former two behaviors with other risk factors. IDU was excluded from the analysis because the prevalence of injection drug use was low (overall 8%) leading to sparse data for multivariate analysis and unreliable estimates due to collinearity of heroin use and IDU [30].

Analysis III

Further, we examined the associations between HIV risk behaviors and various demographic characteristics using logistic regressions, where each risk behavior was used a dependent variable and predictor variables included: age, race, the number of prior incarcerations, length of incarceration as severity index of crime leading to incarceration, and education. The predictor variables were categorized in the same way as in Analyses I and II. The associations of each risk behaviors and certain demographic profiles were characterized by ORs.

Data were extracted and prepared using Access 2003 [31]. All analyses were conducted using the statistical program R [32]. Analysis lack of fit was assessed using Hosmer-Lemeshowtests. Statistical significance was set at a p-value < 0.05.

Results

Among the 264 male HIV-negative participants, the median age was 30 years (range 18-65); the majority was Caucasian (52% Caucasian, 22% Black, 14% Hispanic, 12% others); 51% did not finish high school; and the median number of lifetime incarcerations was 6 (range 1-200). Within the prior 3 months before incarceration, 103 (39%, data not available (NA) = 1) were heavy drinkers; 27 (10%, NA = 1) used heroin; 100 (38%, NA = 1) used cocaine; 161 (61%, NA = 1) used marijuana; and 22 (8%, NA = 1) had injected any type of drug. For the same time period, 203 (77%) had a main sexual partner and of those 170 (84%, NA = 1) never used a condom; 111 (42%) had a non-main sexual partner and of those 37 (36%, NA = 3) never used a condom; 81 (31%) had both main and non-main sexual partners; 61 (26%, NA = 4) had multiple (≥ 3) recent sexual partners; and 233 (90%, NA = 4) did not use a condom at last sexual encounter.

In Analysis I, cocaine use was found to be highly predictive of heroin use (OR = 5.21 with a 95% confidence interval (CI) of 1.8-15), IDU (OR = 6.65, CI = 1.9-23), and multiple sexual partners (OR = 2.45, CI = 1.1-5.3); see Table 1. Heroin use and IDU were mostly co-occurring, suggesting that injection might be the preferred route of heroin use. Heavy drinking and marijuana use were predictive of each other (OR = 2.88, CI = 1.6-5.3). Participants who had unprotected sex with their main and non-main sexual partner(s) were more likely to have unprotected sex at last sexual encounter (OR = 25.7, CI = 9.1-73.0 and OR = 88.6, CI = 15-200, respectively). Notably, unprotected sex with main partner and with non-main partner(s) was likely to co-occur (OR = 6.43, CI = 1.56-78.8). In terms of protective behaviors, participants who reported IDU and those with multiple sexual partners were found to be more likely to use condoms at “the last sexual encounter”, though this finding was marginally statistically insignificant (p-values = 0.08 and 0.07, respectively).

In Analysis II, we found that (1) cocaine use, heroin use, and multiple sexual partners, and (2) heavy drinking and marijuana use were mostly co-occurring (Table 2). Heavy drinking and marijuana use were highly predictive of each other (OR = 3.40, CI = 1.7-7.1). Cocaine use was predictive of heroin use (OR = 9.20, CI = 2.7-38.7) and multiple (≥ 3) sexual partnerships (OR = 2.56; CI = 1.1-6.0).

The analyses that examined the relationships between risk behaviors and demographic characteristics (Analysis III) showed that male jail detainees with age between 30-40 were more likely to abuse cocaine (OR = 8.6, CI = 3.5-23.2), heroin (OR = 4.7, CI = 1.2-23.7), and IDU (OR = 2.8, CI = 1.2-6.9). Younger males with age <30 were more likely to abuse marijuana (OR = 3.8, CI = 2.2-6.9) and had multiple sexual partners (OR = 2.1, CI = 1.2-3.8). African American were more likely to have multiple sexual partners (OR = 3.7, CI = 1.8-7.9), but less likely to engage in unprotected sex in last sexual encounter (OR = 0.3, CI = 0.1-0.6), with main partner (OR = 0.3, CI = 0.1-0.9) and non-main partner(s) (OR = 0.1, CI = 0.03-0.4). Having more than 7 prior incarcerations was predictive of heavy drinking (OR = 1.8, CI = 1.1-3.2), cocaine use (OR = 2.5, CI = 1.4-4.6), and IDU (OR = 2.9, CI = 1.1-7.7). Finishing high school was predictive of having less sexual partners (OR = 0.5, CI = 0.3-0.9) but more likely engaging in unprotected sex in last sexual encounter (OR = 3.3, CI = 1.6-7.2) and with main sexual partner (OR = 3.2, CI = 1.3-8.0).

Discussion

Our results indicate that males entering jail exhibit high rates of substance use and sexual risk behaviors that increase their risk of HIV and other infectious diseases. Our study adds to the existing literature by demonstrating high risk behaviors among incarcerated populations and by highlighting whether certain risk behaviors are more likely to be co-occurring thus compounding risk for HIV infection.

Particularly from our pairwise and multivariate analyses, we find that cocaine is co-occurring with several other risk behaviors including heroin use, injection drug use, and multiple sexual partners. Cocaine use has been reported to not only increase the probability of HIV transmission, but also the potential of poor health outcomes in those living with HIV infection [22,33-35]. Given that there is currently no pharmacotherapy based intervention for cocaine addiction as there is for opiate addiction, our study supports the need of developing behavior-based interventions for cocaine abuse that is appropriate for incarcerated populations in addition to addressing opiate use and risky sexual behaviors. Since jail incarcerations may be as short as several days, behavioral interventions such as contingency management (CM) [36-39] may provide immediate reinforcement for abstinence from cocaine use, and cognitive behavioral interventions that are paired with CM upon release may offer a bridge for continued abstinence following community re-entry [40]. However, these interventions have not been implemented among incarcerated populations [41].

The finding that unprotected sex with main partner is co-occurring with unprotected sex with non-main partner(s) is another important finding, as this suggests that some participants could be involved with concurrent sexual relationships. Concurrent sexual partnerships in incarcerated populations have been reported in several studies [42-46]. Further accounting for concurrent sexual partnerships (and social/sexual networks) in our analyses would strengthen our conclusions, but unfortunately as one limitation of this paper, collecting concurrent behaviors data is not a focus of our original study.

Heavy alcohol use and marijuana use are common substances used by this population and found to be mostly co-occurring. Previous findings with younger incarcerated men [47] suggested that prior to incarceration, the use of marijuana alone and alcohol alone increased the likelihood of multiple sexual partners (i.e. 3 or more) and when in used in combination, sexual HIV-risk behaviors and inconsistent condom use behaviors with female partners increased. Similar finding also can be found in [15,48]. Comparable to other drugs of abuse, alcohol and marijuana use can impair judgment thereby preventing safer sex behaviors, and hence remain an important domain for intervention.

This paper has several limitations. The risk behavior data were self-reported which might have introduced bias and possibly an underreporting of risk behaviors given the environment in which participants completed the questionnaire. Our findings are not generalizable to incarcerated women or the entire population, because it is known that incarcerated women have a different rate of HIV infection and other transmissible diseases compared to men. The study sample size is limited and study participants are restricted only to those at the RIDOC, which limits our analysis power to identify all co-occurring risk behaviors.

As the U.S. incarceration population continues to grow and disproportionate rates of HIV infection continue to rise among incarcerated individuals, the implications for intervention are important and imperative. Jails provide a unique opportunity for structural interventions for this high-risk population. The results of this study offer more insight into the risk behaviors of males entering the RIDOC jail, and elucidate the educational, counseling, and intervention needs of men at risk for HIV infection within the criminal justice system.

Sources of Funding Support

The research is supported by the Providence/Boston Center for AIDS Research (grant P30AI42853). Dr. Pinkston’s work is partially supported by a National Institute of Mental Health grant (5R01MH084757).

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare that there is no conflict of interest regarding the publication of this paper.

References

- Glaze L, Parks Correctional Populations in the United States, 2011. Retrieved Dec 12, 2012, from http: //bjs.ojp.usdoj.gov/content/pub/pdf/cpus11.pdf; 2012.

- Monitoring Selected National HIV Prevention and Care Objectives by Using HIV Surveillance Data—United States and 6 US Dependent Areas—2010. HIV Surveillance Supplemental Report 2012;17(3): part A.

- Spaulding AC, Stephenson B, Macalino G, Ruby W, Clarke J, Flanigan T (2002) Human immunodeficiency virus in correctional facilities: A review. Clinical Infectious Diseases 35: 305–312.

- Spaulding AC, Seals RM, Page MJ, Brzozowski AK, Rhodes W, Hammett TM (2009) HIV/AIDS among inmates of and releasees from US correctional facilities, 2006: declining share of epidemic but persistent public health PLoS One 4(11): e7558. [corssref]

- National Commission on Correctional Health Care. The health status of soon-to-be- released inmates: A report to Congress, Volumes 1 and 2. National Commission on Correctional Health Care; 2002, Chicago.

- Dean-Gaitor HD, Fleming PL (1999) Epidemiology of AIDS in incarcerated persons in the United States, 1994-1996. AIDS 13: 2429–2435. [corssref]

- Hammett TM (1998) Public health/corrections collaborations: Prevention and treatment of HIV/AIDS, STDs, and TB. US Department of Justice, Office of Justice Programs, National Institute of Justice.

- Maruschak L. HIV in prisons, 2004. Retrieved March 6, 2009, from http: //www.ojp.usdoj.gov/bjs/pub/pdf/hivp04.pdf;

- Springer R (2004) Patient safety initiatives–correct site verification. Plast Surg Nurs 24(1): 6–7.

- Harrison P, Beck Prisoners in 2005. Washington, DC: Bureau of Justice Statistics, US Dept of Justice; 2006. NCJ publication 2006; 215092.

- Braithwaite R, Hammett T, Mayberry R. Prisons and AIDS: A public health challenge. New York: Jossey-Bass;

- Braithwaite R, Arriola K (2008) Male prisoners and HIV prevention: a call for action ignored. Am J Public Health 98(9 Suppl): S145–9. [corssref]

- Wohl AR, Johnson D, Jordan W, et al. (2000) High-risk behaviors during incarceration in African-American men treated for HIV at three Los Angeles public medical centers. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr 24(4): 386–92.

- Conklin TJ, Lincoln T, Tuthill RW (2000) Self-reported health and prior health behaviors of newly admitted correctional inmates. Am J Public Health 90(12): 1939–41. [corssref]

- Altice FL, Mostashari F, Selwyn PA, et al. (1998) Predictors of HIV infection among newly sen- tenced male prisoners. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr Hum Retrovirol 18(5): 444–53.

- Stephenson BL, Wohl DA, McKaig R, et al. (2006) Sexual behaviours of HIV-seropositive men and women following release from prison. Int J STD AIDS 17(2): 103–8.

- Weinbaum CM, Sabin KM, Santibanez SS. Hepatitis B, hepatitis C, and HIV in cor- rectional populations: a review of epidemiology and AIDS 2005;19 Suppl 3: S41–6.

- Mertz KJ, Schwebke JR, Gaydos CA, Beidinger HA, Tulloch SD, Levine Screening women in jails for chlamydial and gonococcal infection using urine tests: feasibility, acceptability, prevalence, and treatment rates. Sex Transm Dis 2002;29(5): 271–6.

- Chandler RK, Fletcher BW, Volkow ND (2009) Treating drug abuse and addiction in the criminal justice system: improving public health and safety. JAMA 301(2): 183– [corssref]

- Morrow KM. HIV, STD, and hepatitis risk behaviors of young men before and after incarceration. AIDS Care 2009;21(2): 235–43. [corssref]

- Milloy MJ, Buxton J, Wood E, Li K, Montaner JS, Kerr T (2009) Elevated HIV risk behavior among recently incarcerated injection drug users in a Canadian setting: a longitudinal analysis. BMC Public Health 9: 156.

- McCoy CB, Lai S, Metsch LR, Messiah SE, Zhao W (2004) Injection drug use and crack cocaine smoking: independent and dual risk behaviors for HIV Ann Epidemiol 14(8): 535–42. [corssref]

- Shannon K, Rusch M, Morgan R, Oleson M, Kerr T, Tyndall MW. HIV and HCV prevalence and gender-specific risk profiles of crack cocaine smokers and dual users of injection drugs. Subst Use Misuse 2008;43(3-4): 521–34.

- Effectiveness of interventions to address HIV in prisons. Geneva, Switzerland: World Health Organization 2007.

- Fazel S, Bains P, Doll H (2006) Substance abuse and dependence in prisoners: a systematic review. Addiction 101(2): 181–191. [corssref]

- Koulierakis G, Gnardellis C, Agrafiotis D, Power KG (2002) HIV risk behaviour correlates among injecting drug users in Greek prisons. Addiction 95(8): 1207–1216.

- HIV risk behavior before and after HIV counseling and testing in jail: a pilot study. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr 2009;53(4): 485–90.

- Rubin DB. Inference and missing data (with discussion). Biometrika 1976;63: 581–592.

- Little RJA, Rubin DB. Statistical Analysis with Missing Data 2nd ed. Hoboken, NJ: John Wiley & Sons; 2002.

- Armitage P, Berry G, Matthews JNS. Statistical Methods in Medical Research. Malden, MA: Blackwell; 2002.

- Microsoft Access (2003). Microsoft Co (www.microsoft.com); 2003.

- R Development Core R: A Language and Environment for Statistical Computing. Vienna, Austria; 2010. ISBN 3-900051-07-0.

- Strathdee SA, Sherman SG. The role of sexual transmission of HIV infection among injection and non-injection drug users. J Urban Health 2003;80(4 Suppl 3): iii7–14. [corssref]

- Moore J, Hamburger ME, Vlahov D, Schoenbaum EE, Schuman P, Mayer Longitudinal study of condom use patterns among women with or at risk for HIV. AIDS and Behavior 2001;5: 263–273.

- Lucas GM, Griswold M, Gebo KA, Keruly J, Chaisson RE, Moore RD (2006) Illicit drug use and HIV-1 disease progression: a longitudinal study in the era of highly active antiretroviral therapy. Am J Epidemiol 163(5): 412–20. [corssref]

- Petry NM, Alessi SM, Hanson T (2007) Contingency management improves abstinence and quality of life in cocaine abusers. J Consult Clin Psychol 75(2): 307–15. [corssref]

- Rash CJ, Alessi SM, Petry NM (2008) Contingency management is efficacious for cocaine abusers with prior treatment attempts. Exp Clin Psychopharmacol 16(6): 547–54. [corssref]

- Ledgerwood DM, Alessi SM, Hanson T, Godley MD, Petry NM (2008) Contingency management for attendance to group substance abuse treatment administered by clinicians in community clinics. J Appl Behav Anal 41(4): 517–26. [corssref]

- Petry NM, Barry D, Alessi SM, Rounsaville BJ, Carroll KM (2012) A randomized trial adapting contingency management targets based on initial abstinence status of cocaine- dependent patients. J Consult Clin Psychol 80(2): 276–85. [corssref]

- Epstein DH, Hawkins WE, Covi L, Umbricht A, Preston KL (2003) Cognitive-behavioral therapy plus contingency management for cocaine use: findings during treatment and across 12-month follow-up. Psychol Addict Behav 17(1): 73–82. [corssref]

- Polonsky S, Kerr S, Harris B, Gaiter J, Fichtner RR, Kennedy MG (1994) HIV prevention in prisons and jails: obstacles and opportunities. Public Health Rep 109(5): 615–25.

- Adimora AA, Schoenbach VJ, Martinson F, et al. (2004) Concurrent sexual partnerships among African Americans in the rural south. Annals of Epidemiology 14(3): 155–160. [corssref]

- Mumola C, Karberg Drug use and dependence, state and federal prisoners, 2004. Re- trieved March 6, 2009, from http: //www.ojp.usdoj.gov/bjs/pub/pdf/shsplj.pdf; 2006.

- Adimora AA, Schoenbach VJ, Martinson FEA, Donaldson KH, Stancil TR, Fullilove RE (2003) Concurrent partnerships among rural African Americans with recently reported heterosexually transmitted HIV infection. JAIDS 34(4): 423–429.

- Khan MR, Doherty IA, Schoenbach VJ, Taylor EM, Epperson MW, Adimora AA (2009) In- carceration and high-risk sex partnerships among men in the United States. J Urban Health 86(4): 584–601. [corssref]

- Manhart LE, Aral SO, Holmes KK, Foxman B (2002) Sex partner concurrency: measurement, prevalence, and correlates among urban 18-39-year-olds. Sexually Transmitted Diseases 29(3): 133–143.

- Valera P, Epperson M, Daniels J, Ramaswamy M, Freudenberg N (2009) Substance use and HIV-risk behaviors among young men involved in the criminal justice system. The American Journal of Drug and Alcohol Abuse 35(1): 43–47.

- Edlin BR, Irwin KL, Faruque S, et al. (1994) Intersecting epidemics–crack cocaine use and HIV infection among inner-city young adults. New England Journal of Medicine 331(21): 1422–1427.