DOI: 10.31038/JIPC.2021111

Abstract

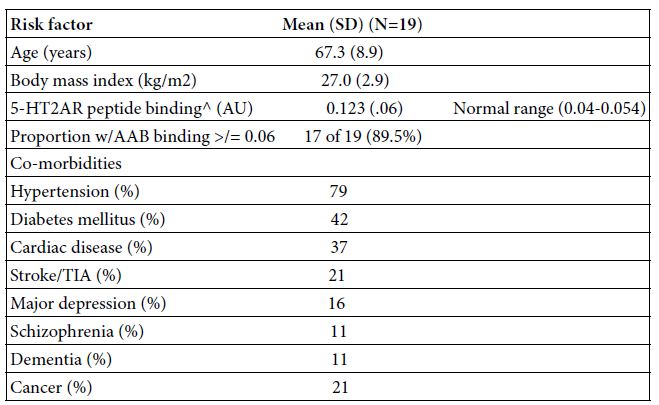

The paper presents a statewide study of responses to COVID-19, done in Arizona, USA, as preparation for the upcoming vaccine, promised for 2021. The objective is to determine the key messages which would engage Arizonans, and interest them in as preparation for a state-wide vaccination campaign. The process followed the Mind Genomics protocol, a protocol used to uncover how people think about the ordinary topics of their lives, done by exposing them to systematic combinations of messages, and determining which individual messages drove their ratings. The data confirmed previous North American findings, that there are two major mind-sets when it comes to COVID-19, the Pandemic Onlookers who are not involved and are engaged by one set of messages, and the Pandemic Citizens, who are involved, want to be guided by the government, and are engaged by another set of messages. These two mind-sets distribute throughout the population but can be quickly identified through a six-question, 30-second intervention, the PVI, Personal Viewpoint Identifier.

Introduction

During the past 50 years, researchers have adopted more and more structured approaches to gaining information about people, whether these people be consumers of products, clients for services, and now citizens who need government guidance in the case of emergencies. Clients of services may include individuals who are already sick and need medical help, whether from doctors, or from hospitals, as well as from pharmacists, and so forth. Indeed, it is well accepted that the customer, whether patient of a physician or patient in a hospital is due good service, at a fair price, and in a reasonable time [1-3].

The issue becomes ‘sticky’ when the client or the customer is the citizen, and the need is for guidance which has medical aspects involved, aspects which may need to be personal to be effective. For example, COVID-19 continues to suggest that bland messaging from the government about the dangers of COVID-19 appears to be effective for some individuals, but not for others. Some citizens believed the information and took precautions suggested by government spokespeople, whereas others flaunted the recommendations, frequently and with abandon.

The recent COVID-19 Pandemic has affected many states in what can only be considered a true crisis. The origin of the research reported in this paper was the effort to begin a program of understanding the mind of the Arizonan, a state, a defined entity in the United States. The objective was to find out how the Arizonan felt about the different aspects of the COVID-19 virus, to classify the citizen, not according to who the citizen is, but how the citizen thinks. The slighter longer-term goal was to use this information to drive next-steps in communication, specifically to tailor communications about protection from COVID-19 using the specific way the citizen thinks.

The study reported here represents the first effort to apply the emerging science of Mind Genomics to the citizens of an entire state, with the goal of improving communication about the pandemic, doing so during the crisis, rather than as an academic exercise AFTER the virus.

During the past decade, the increasing sophistication of marketers has moved from selling ideas to selling better lives through public messages, hopefully effective ones. The basic notion is quite simple; the more one knows about the customer with respect to the specific topic to be ‘messaged,’ the more effective the message will be. Despite the simplicity of the idea, the actual implementation is fraught with problems from beginning to end.

Marketers attempt to ‘know’ their customers, but for most topics the effort to know customers is expensive relative to the opportunity. For example, for most small items, such as shoes or dresses, or even houses, it costs much more to discover the proper messaging than the marketer is willing to pay. There emerges a culture of fast, qualitative research, if any research at all. The marketer hires a competent focus group or individual moderator, moves on with the test, and determines next steps, such as the proper words.

This paper presents the first part of an attempt to understand the mind of the Arizona citizen with respect to COVID-19, in preparation for the upcoming vaccine, promised in 2021. The objective is to understand the motivating messages which ‘reach citizens,’ not only in terms of actual messages, but themes which could be used later on to drive vaccination. The anti-vaxxer movement has gained strength over the years for various reasons, ranging from religious to conspiracy theory, as well as disbelief, and indifference [4-7].

Knowing the nature of how people respond to messages about COVID-19, and how people respond to messages about vaccination provides a way of convincing people to do what is medically appropriate.

Method

The approach presented in this paper is called mind genomics. Mindy genomics is an emerging psychological science based in experimental psychology, anthropology, sociology, consumer research, statistics, and political polling, respectively. It does not, of course, take into account the full gamut of these sciences but finds the topics and methods of the science to be relevant, and to form a good foundation for the science.

The fundament of Mind Genomics is the focus on the world of the everyday, about the decisions that we make as we confront problems and situations in our daily life. What are the criteria which convince us about the ordinary? We are not talking about the attempts to elucidate basic principles of behavior by putting people into artificial test situations, unusual experiments, watching their response and then concluding about a certain type of thinking which must be going on to result in that behavior. Rather, we are talking about responses to stated everyday situations, the pattern of the way a person thinks deduced from the way a person reacts [8].

It is important to emphasize the worldview of Mind Genomics, the world of experiment, and the history with deep roots in experimental psychology. The word ‘experiment’ is key; data which emerges from the science should be based upon experiments. The experiments, in turn, are different ways of obtaining opinions, ways emerging from the recognition that the respondent often wants to please the interviewer and be seen in a way that is today called ‘politically correct.’ This bias makes itself known in surveys when the respondent changes the criterion of the rating, based upon the specific topic of the survey question. The goal of the respondent defeats the purpose of the survey.

Mind Genomics presents these respondent-generated biases. Rather than having a person answer a survey questionnaire, item by item, the experiment puts different messages together in combinations, presents this combination or the set of combinations to a respondent, obtains a rating of the combination, and then through regression analysis at estimates the contribution of each individual element or message. The approach is simple because the messages present simple situations and issues that the respondent encounters every day. The respondent simply responds to the designed combination, from which the judgment criteria emerge by linking the individual elements or messages to the responses.

The Arizona study and the Mind Genomics protocol now follow. The protocol is illustrated by the specifics of the study.

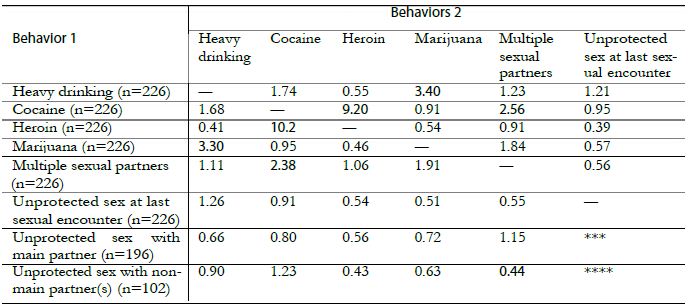

Step 1 – Topic, Question, Answers (Messages, Elements)

The researcher must select the topic select four questions which illuminate the topic, and create four answers, in phrase form, which address each question. Table 1 shows an example of the exercise. Note that the Mind Genomics worldview is that these experiments are cartographies, mapping out the different topics of the mind. Anyone can become a Mind Genomics researcher simply by following the steps, the most important step being Step 1. It is also important to note that Mind Genomics is quick, iterative, inexpensive, building knowledge quickly, often in a matter of hours. The feature of iteration means that the questions and answers or elements shown in Table 1 need not be the final materials. One might go through four or five iterations, improving, throwing out what doesn’t ‘work’, or doesn’t convince respondents, replacing the discarded with new material, and then move on to the next iteration. In this fashion, Mind Genomics is as much a learning system as it is a scientific testing and research technology.

Table 1: The four questions and the four answers (aka messages, elements) to each question

|

Question A: What is the perceived risk of COVID-19? |

| A1 |

COVID-19 is spreading quickly in Arizona |

| A2 |

New strains of the virus – causing concern |

| A3 |

Government should be doing more |

| A4 |

Everyone should take care of themselves |

|

Question B: What are my practices of masking? |

| B1 |

Stay home so I don’t have to worry about masks |

| B2 |

Masks protect me |

| B3 |

I mask up to protect older people that I love |

| B4 |

Avoid places where people aren’t wearing masks |

|

Question C: Who do I trust for information about the virus? |

| C1 |

I trust my doctor’s advice |

| C2 |

My employer gives the best information about the virus |

| C3 |

My religious leader tells me how to stay safe |

| C4 |

I listen to my family and children about staying safe |

|

Question D: Where do I get my news? |

| D1 |

Local Arizona media keeps me up to date |

| D2 |

Social media gives me the fastest news |

| D3 |

News from my employer is accurate |

| D4 |

My friends and family pass along the news |

The reader should note that we report the results of the first experiment regarding how to understand and how to motivate Arizonans to consider the COVID-19 vaccine. The materials selected in Table 1 for questions and answers have appeared in part in other studies [9], albeit with some of the language changed, based upon previous results in other countries. It is also worth noting that the study was done overnight in Arizona, approximately four hours after the study was launched on the internet.

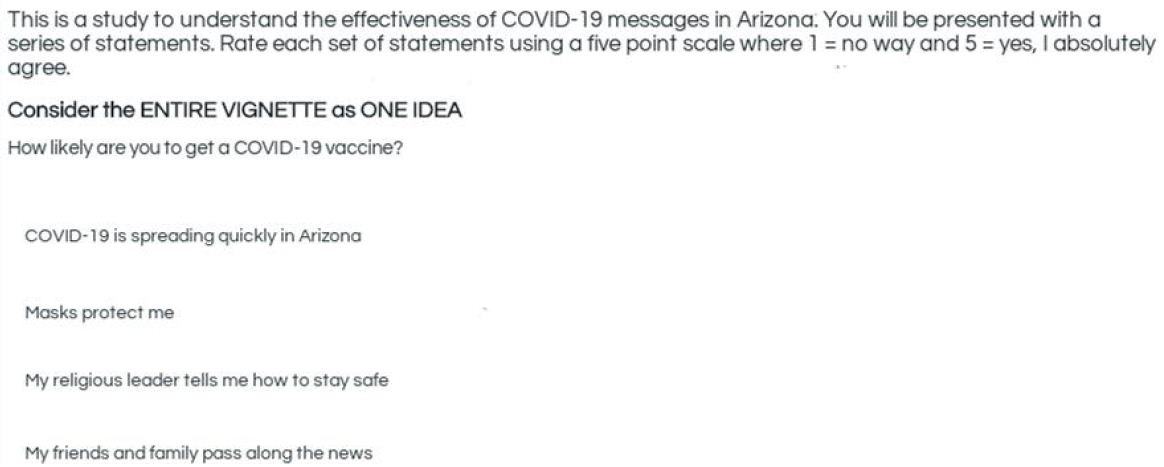

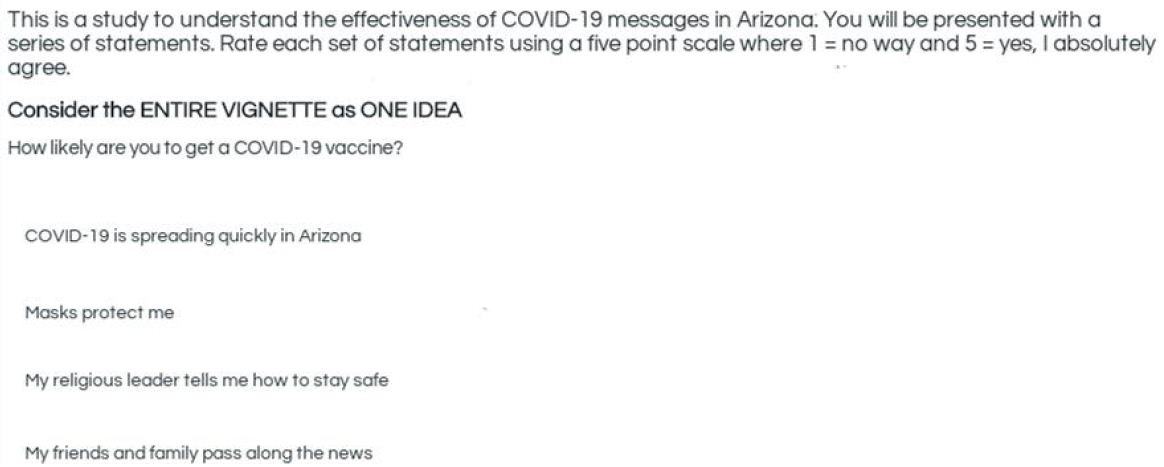

Step 2: Prepare the Introduction to the Respondent, and the Rating Question

The ideal format for a Mind Genomics questionnaire differs for consumer/citizen studies vs. medical/legal studies. For consumers and citizens, the objective is to understand how they react to specific messages, in terms of the degree to which the messages motivate them to do something, in this case to obtain a vaccine. In such cases, the less said the better in the introduction. The introduction just introduces the topic. The specific messages, their content, their tonality, and the mind of the respondent will drive the respondent’s rating. The rating scale is a simple 5-point Likert Scale [9].

The introduction and the rating question appear below:

This is a study to understand the effectiveness of COVID-19 messages in Arizona. You will be presented with a series of statements. Rate each set of statements using a five-point scale

How likely are you to get a COVID-19 vaccine? 1=No way 5=Yes, I absolutely agree

Step 3: Build the Test Vignettes

The respondent evaluates combinations of elements, not single elements alone. It is the set of 24 combinations, created according to an underlying experimental design, which is the mechanism by which the respondent’s underlying attitude towards a topic can be obtained and the tendency to be politically correct defeated or at least strongly stymied. The vignette, appearing as an example in Figure 1, presents a combination of elements in a manner which seems haphazard, almost created by random.

Figure 1: Example of a vignette.

The reality underlying the construction of the vignette is as far away from randomness as one can get with a systematic design. It is true that the combination is not written to tell a story. The objective of the vignette specifically, and Mind Genomics generally, is, figuratively, to ‘throw combinations of messages at the respondent, and see the rating.’ There is no underlying store to which the respondent can anchor, and be consistent within that anchor, and common principle. Rather, Mind Genomics is simply the response to seemingly random combinations. The respondent sits at the computer for about two-minutes, responding to 24 of these combinations, feeling that they are random, not realizing that the combinations have been systematically created. The respondent attempts to cope with the overload, but quickly relaxes into an almost automatic response, the type called System 1 by Nobel Laureate, Daniel Kahneman [11]. The respondent eventually ends up assigning the rating in an almost automatic, passive way, frustrated in the attempt to ‘game the system’ by the rapidly appearing and disappearing combinations.

There are two powerful aspects of the experimental designs used by Mind Genomics, of which the 4×4 (four questions, four answers to each question) is only an example. The first aspect is that the elements are statistically independent, viz. in a statistical sense all 16 elements are independent so that they can be used without concern in an OLS (ordinary least-squares) regression to uncover the relation between the elements and either the response or the linkage of the element to response time, the time needed to process the information and respond. The second aspect is that all the 24 vignettes used by a respondent are different from the 24 vignettes evaluated by a second response. The benefit there is that the Mind Genomics procedure covers a lot of the design space [12].

Across the set of 24 vignettes each person will encounter the same number of each of 11 different structures, albeit with different specific elements. The structure is defined as the questions which generate the elements, but not the specific elements themselves. The 11 structures comprise the six different structures for two-element vignettes, (AB AC AD BC BD CD), the four different structures for three-elements vignettes (ABC ABD ACD BCD), and the one structure of four elements (ABCD). We will see that some of these structures are, on average, stronger performers than other structures, when the data from the respondents is analyzed by structure.

Step 4: Run the Experiment and Create a Simple Topline Report (Surface Analysis)

Mind Genomics studies are run entirely on the internet, in a structure which is presented as a survey, not as an experiment. The appellation ‘experiment’ often irritates and confounds prospective respondents. The 500 respondents were members of a set of panels, used by the online study vendor, Luc.id of Louisiana. Luc.id provides populations of respondents from different geographical areas, of specific demography and activities. The panelists had to be residents of Arizona over the age of 18.

Table 2 shows the average ratings on the 5-point scale, and the average response time for each of the 11 structures. Each vignette in the study was assigned one of the 11 structures, depending upon the elements appearing, those elements dictated by the underlying experimental design. The respondent rated each vignette with the rating and the response time recorded. The response is operationally defined as the number of seconds, to the nearest tenth of second, elapsing between the appearance of the vignette and the rating.

Table 2: How average rating and average response time covary with structure of the vignette

| Structure |

Questions |

Rating

|

Response Time

|

| ALL |

Total |

3.4

|

3.8

|

| AD |

Risk News |

3.4

|

4.0

|

| AB |

Risk Masking |

3.4

|

4.0

|

| ABC |

Risk Masking Trust |

3.4

|

3.9

|

| CD |

Trust News |

3.5

|

3.8

|

| BCD |

Masking Trust News |

3.4

|

3.8

|

| ACD |

Risk Trust News |

3.4

|

3.8

|

| ABCD |

Risk Masking Trust News |

3.4

|

3.8

|

| ABD |

Risk Masking News |

3.4

|

3.8

|

| AC |

Risk Trust |

3.1

|

3.8

|

| BC |

Masking Trust |

3.4

|

3.7

|

| BD |

Masking News |

3.5

|

3.6

|

Table 2 shows a modest range in the average ratings, from a high of 3.5 to a low of 3.1). This suggests that the either the elements are seen to be equal, or there are deep differences among people in the types of elements with which they agree, but these deep differences cannot easily be seen. The differences are not emerging out the structure of the vignette, suggesting that respondents ‘graze’ for the information they need, rather than proceeding linearly through the vignette. If respondents were to proceed linearly through the text of a vignette, the vignettes with more elements would show higher response times, due to the longer times needed to read three and four elements. In contrast, the vignettes with fewer elements would show lower responses times but they do not. The data suggest that it is the nature of the information which drives the response times. The topic of ‘risk’ is the most engaging, the topic of ‘masking’ the least engaging.

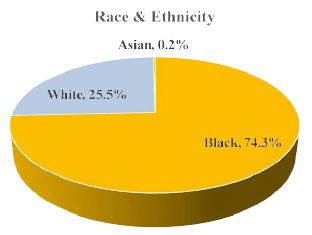

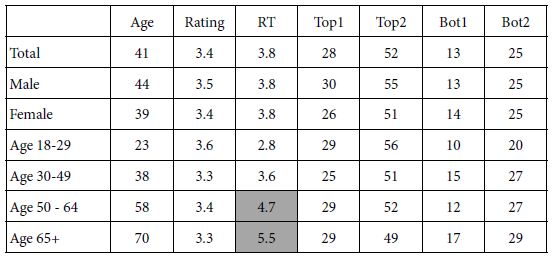

One of the recurring themes in social research is that the differences in the responses may well be due to who the respondent IS. That is, there is an ongoing belief that people vote based upon who they are. Thus, much of the news reported focuses on differences between groups of people who can be easily identified, such as gender, or age-cohorts (e.g., Baby Boomers vs. Millennials vs. Generation X, etc.).

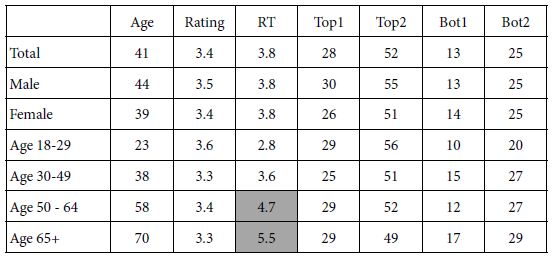

The data from this study allows us to look at the average rating and the response time from different, identifiable groups, as shown in Table 3. Table 3 shows the average age, the average rating, and the average response time, for each defined group. Table 3 also shows averages from transformed data (see Step 5 below). We see little difference in the average ratings, but we do see substantial differences in the average values of the response times, differences which make sense. Young respondents (age 18 – 29) read and rate much faster than average (2.8 seconds per vignette vs. 3.8 seconds on average), whereas old respondents (age 65+) read and rate more slowly (5.5 seconds on average).

Table 3: Average age, 5-point rating, response time (RT), and binary transformed ratings) for Total, Gender and Age, respectively

It is important to keep in mind that the differences in response time may be due both to age and to topic. We know that when the topic moves from social issues such as vaccine and COVID-19, to issues that are more ‘fun’ such as products, the response time usually diminishes, perhaps because the respondent does not have to think about the topic quite as seriously.

Step 5 – Prepare the Data for Regression Linking Elements to Responses

The underlying experimental design allows us to link the presence or absence of each element to the rating and to the response time. Yet, there is a problem with the data, one which must be solved before the analysis can proceed in a smooth manner. The problem or issue is the way one should interpret the results of a Likert Scale. From author HRM’s experience, managers commissioning the study or working with the data often ask about the meaning of the rating, such as ‘what does a 4 mean on the scale, from a practical point of view?” What the manager needs is a more black-and-white metric, one which reduces the task of interpreting the data.

Consumer researchers and public opinion pollsters are well-aware of the problems with managers interpreting the data for simple scales. Indeed, in the words of S.S. Stevens, Doyen of modern-day psychophysics, ‘one of the hardest problems in science is to go from a scale to a yes/no’ [13].

Researchers world-wide have suggested simple ways of dividing Likert Scales. For the five-point scale used today, researchers had suggested using the ratings of 5 & 4 as the key variable. Vignettes rated 5 or 4 are assigned the value of 100, vignettes rated 1, 2 or 3 are assigned the rating of 0. This is called the ‘Top2 Box,’ abbreviated here ‘Top2’. The reason is simple; The top 2 scale points (or ‘boxes’) are the ones selected.

In this spirit, we have created four new variables to use in our exploration:

Agree with the need for/goal of vaccination

Top1: Rating of 5 transformed to 100, ratings of 1, 2, 3 and 4 transformed to 0

Top 2: Rating of 5 and 4 transformed to 100, ratings of 1, 2, and 3 transformed to 0

Bot1: Rating of 1 transformed to 100, ratings of 2, 3, 4 and 5 transformed to 0

Bot 2: Rating of 1 and 2 transformed to 100, ratings of 3, 4 and 5 transformed to 0

A small random number less than 10-5 is added to each of these numbers to create some variability around the ratings. When a respondent assigns all ratings 1 & 2, or 4 & 5, respectively, regression analysis will ‘crash’ because the regression needs a bit of variation in the dependent variable, the transformed number. The transformation prevents the crash of the regression modeling but is far too small to affect the data in a meaningful way.

Step 6: Relate Elements to Ratings by OLS Regression

OLS (ordinary least-squares) regression relates the presence or absence of the 16 elements to the dependent variable. We begin with two dependent variables, the 5-point rating scale, and the response time. We add four more dependent variables, emerging from our transformation to the binary scales; Top1, Top2, Bot1, Bot2. These were defined in Step 5.

The basic equation is simple:

Dependent Variable = k0 + k1 (A1) + k2(A2) … k16(D4)

Simply stated, the dependent variable is the sum of a single base number (additive constant), and the contributions of the elements in the vignettes, these contributions being estimated by the OLS regression, and shown as k1-k16.

The value k0 is not estimated for the response time, RT, simply because it has no meaning. The value k0 is also not estimated for the 5-point scale, to give a sense of the number of rating points contributed by each element. For the other five dependent variables, k0 is the estimated value of the dependent variable in the case where all the elements in the vignette are 0, viz., absent. Such a situation, a vignette without elements, is impossible according to the underlying experimental design.

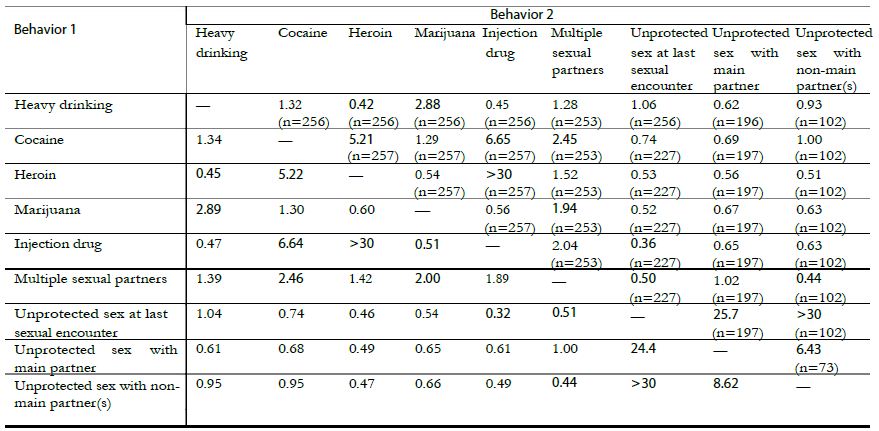

Table 4 presents the data from the Total Panel, showing only the positive coefficients. The data are incomplete, but to show all coefficients, negative values as well as 0, overwhelms the reader. The positive coefficients are those which drive the response towards the top of the scale, whether the scale be Top1 (highest possible agreement with getting a vaccine), Top2 (strong agreement with getting a vaccine), or towards the bottom of the scale, Bot1 (highest possible disagreement with getting a vaccine), or Bot2 (strong disagreement with getting a vaccine).

Table 4: How the 16 elements drive the ratings, both transformed binary ratings, original 5-point rating, and response time.

| |

|

TOP1 |

TOP2 |

BOT1 |

BOT2 |

RATING |

RT

|

|

Additive constant |

28

|

53 |

15 |

28 |

NA |

NA

|

| A1 |

COVID-19 is spreading quickly in Arizona |

|

|

|

|

1.0 |

1.1

|

| A2 |

New strains of the virus – causing concern |

|

|

|

|

0.9 |

1.1

|

| A3 |

Government should be doing more |

|

|

|

|

0.9 |

1.0

|

| A4 |

Everyone should take care of themselves |

1

|

|

|

|

1.0 |

1.1

|

| B1 |

Stay home so I don’t have to worry about masks |

|

1 |

|

|

1.1 |

1.2

|

| B2 |

Masks protect me |

|

|

|

|

1.0 |

1.1

|

| B3 |

I mask up to protect older people that I love |

|

1 |

|

|

1.0 |

1.2

|

| B4 |

Avoid places where people aren’t wearing masks |

|

|

|

|

1.0 |

1.2

|

| C1 |

I trust my doctor’s advice |

|

|

|

|

1.0 |

1.1

|

| C2 |

My employer gives the best information about the virus |

|

|

|

|

1.0 |

1.1

|

| C3 |

My religious leader tells me how to stay safe |

|

|

|

|

1.0 |

1.1

|

| C4 |

I listen to my family and children about staying safe |

1

|

1 |

|

|

1.1 |

1.1

|

| D1 |

Local Arizona media keeps me up to date |

|

|

|

|

1.0 |

1.0

|

| D2 |

Social media gives me the fastest news |

|

1 |

|

|

1.0 |

1.0

|

| D3 |

News from my employer is accurate |

|

1 |

|

|

0.9 |

1.0

|

| D4 |

My friends and family pass along the news |

|

1 |

|

|

1.0 |

1.0 |

The actual interpretation of the data is left to the reader, but the Total Panel shows little in the way of patterns. The additive constant for Top1 tells us that about a quarter of the responses would be ‘5’ in the absence of the elements. Note that the additive is a theoretical, computed value, since all vignettes comprised 2-4 elements. The additive constant is a good parameter to give a sense of the ‘baseline’ level of feeling. For Top1 (strongest interest), we see an additive constant of 28, low, and in need of a ‘push’ from the elements. When we look at positive responses, 4 and 5, combined into the variable Top2, see a little over half, 53% of the responses are expected to be positive. Similarly, when we look at the negative part of the scale, about 15% of the responses are expected to be extremely negative, and a little less than twice that number (viz., 28%) are expected to be strongly or moderately negative.

Our next task is to use judgment to identify, where possible, elements with high positive coefficients for either Top1 (ideal) or Top2 (strong or moderate interest in the vaccine). Table 4 shows us no strong elements at all, a disappointing finding. From our first effort, and looking at the total panel, we find that no elements drive interest in being vaccinated. The answer may be either that we have not found that ‘magic bullet,’ or that we may have a powerful element, but it is lost in ‘noise’. We soon will see that the latter is probably the case, that there is noise in the data emerging from different groups of people, with varying, occasionally conflicting opinions.

A second look is at the response times. Do opinions of these messages engage the respondent? Engagement might be either good or bad, good when the message is a driver for vaccination, bad when the message is irrelevant, and a time waster. The model for the response time is lacking a constant. No elements engage by having the respondent focus on the element for more than 1.2 seconds.

Our first conclusion is that there is no pattern, that all the messages are irrelevant, and that the experiment was unable to uncover any element which is promising. That is, when we treat all of the respondents in the same way. We are either dealing with irrelevant elements, certainly a strong possibility in the absence of any other reasons to think otherwise, OR we are dealing with elements which push in opposite directions, cancelling each other out.

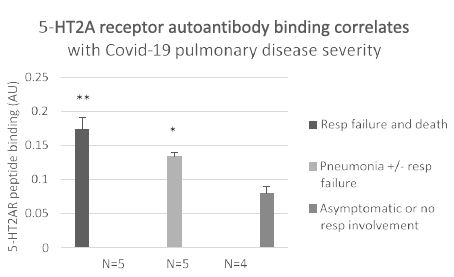

Step 7: Granular Understanding by Clustering to Uncover Mind-sets

We saw above that there are few differences among the elements in terms of those driving positive interest to get vaccinated. Some of this ‘flatness’ may emerge from the fact that people think in different ways, effectively canceling each other when they are blended together in a database which does not recognize these individual patterns.

Mind Genomics studies have uncovered the existence of different groups of ideas which go together, different mind-sets of these related ideas. It is not that people differ, but rather that the ideas they hold are of different types, even when the topic is the same. By clustering the patterns of coefficients across the individual respondents, viz., putting together people with similar patterns, Mind Genomics can identify these basically different groups of ideas. These different groups are the so-called ‘mind-sets’ [14,15].

The process of clustering is a standard statistical method. The method of k-means clustering looks at the 16 coefficients of each respondent, based upon the relation between Top2 (dependent variable) and the presence/absence of the elements. The additive constant is computed, but not used here. The clustering, based upon similarity of patterns, divides the 500 patterns into one, two, and the three groups. Each respondent is a member of only one of the groups, with two groups, or a member of one group when three groups are extracted [15].

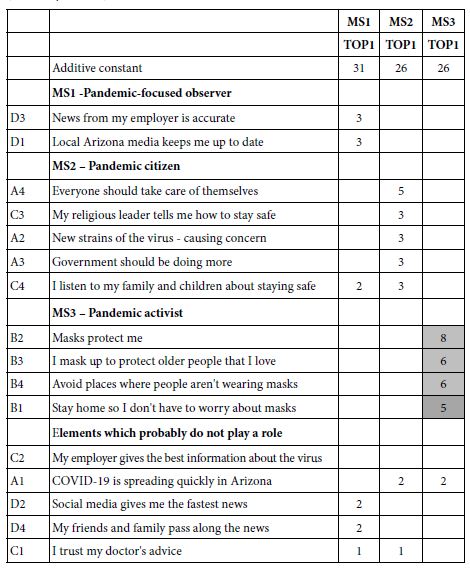

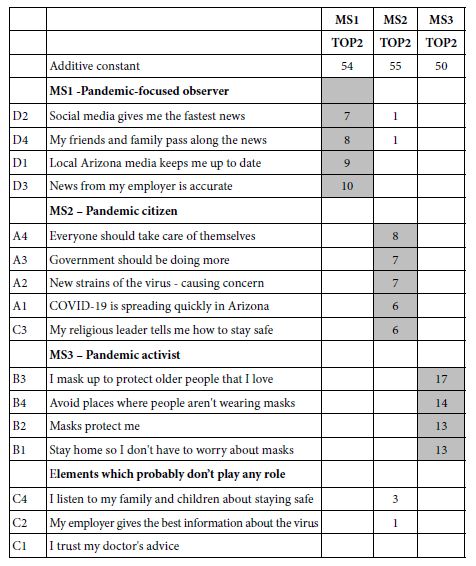

The original analysis by clustering uses the coefficients obtained for the Top2 analysis, meaning that ratings of 4 and 5 are converted to 100, and ratings of 1-3 are converted to 0. We will remain with that clustering. For the prescription of what to feature in the messages, we will the make analysis more stringent, however. We will look at the models or equations relating the presence/absence of the 16 elements to rating 5:, How likely are you to get a COVID-19 vaccine? 1=No way 5=Yes, I absolutely agree. This is the Top1 equation, showing which elements are the strongest. Thus, we keep the clustering method the same (based on Top2), but the reportage as more stringent (use Top1 data for modeling).

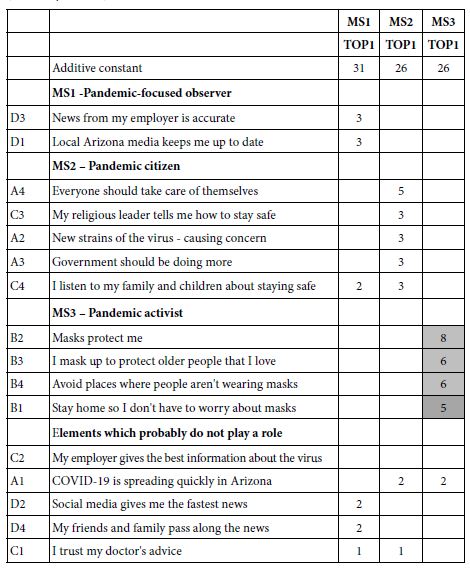

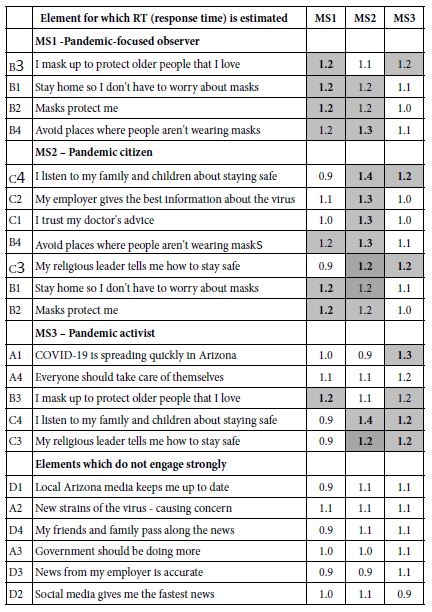

Table 5 shows the positive coefficients for the Top1 model. It is clear that there are few elements which are strongly effective for each mind-set. These are the elements to select for the final messaging. The selection is far easier when the criterion is low, but the downside of the process is that the coefficients are low, albeit the most powerful. The only exception to the pattern of low coefficients emerges from mind-set MS3, the Pandemic Activist, comprising about 1/3 of the respondents.

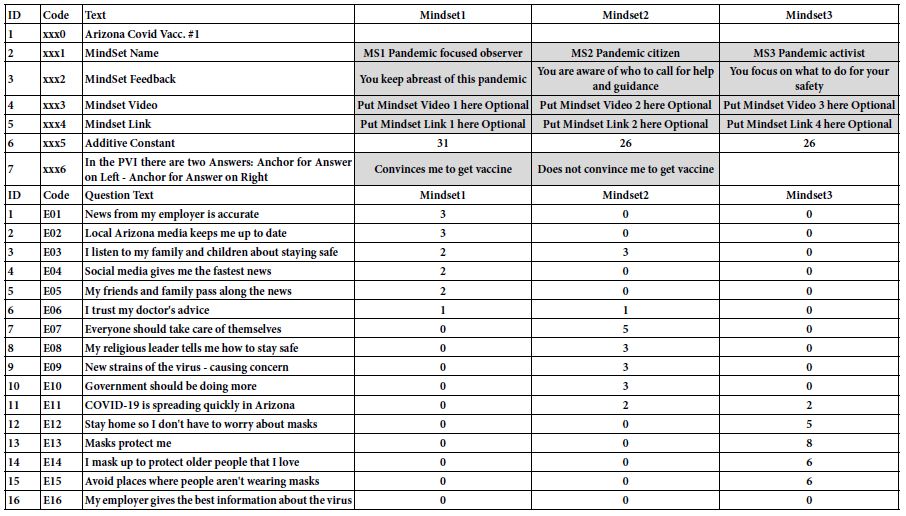

Table 5: Strongest performing elements for vaccination, viz., highest coefficients for TOP1 (Definitely will vax)

The important consideration here is that the message be strong. Choosing a message which contributes to rating 5 (definitely will vax) is better than a message which contributes to both rating 4 and 5 (definitely/probably will vax.) The choice towards the messages which are most effective, recognizing that there can probably be at most three messages.

The final thing to keep is mind is the radically different elements which score well. These elements are clearly touching different aspects of the COVID-19 experience, suggesting quite different mind-sets among the respondents.

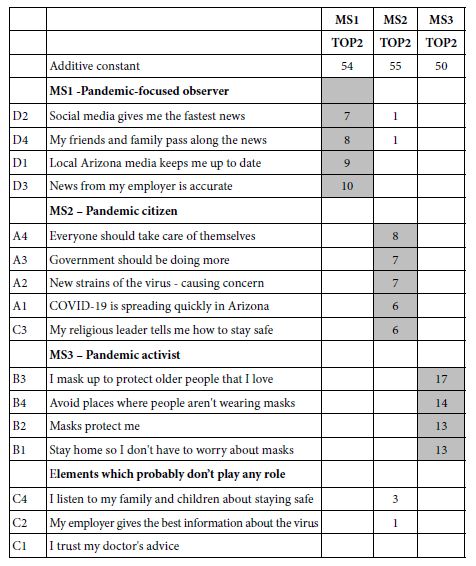

To get a sense of the power of a tough criterion, such as Top1, consider the same Table, but the more typical case, wherein the elements are the strong performers, but for Top2 (Definitely/Probably be vaccinated). Many of the elements are the same, but the first impression from Table 6 is a greater richness of information. That richness is certainly satisfying, but when it comes time to put the information into practice one will inevitable be confronted with the question about which of the strong performing elements is actually the ‘strongest’. That is, having a wealth of information is rewarding for the stage when one seeks understanding, but problematic when the task is to choose the one, two, or three elements from the set, and allowed only those choices.

Table 6: Strong performing elements for vaccination, viz., highest coefficients for TOP2 (Definitely will vax, probably will vax, ratings 5 and 4)

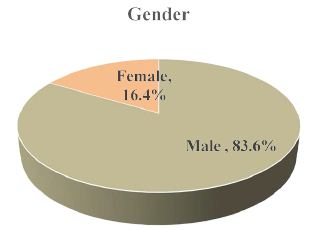

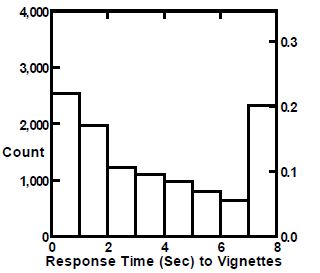

Step 8: Understand the Engagement Power of the Elements Using RT (Response Time)

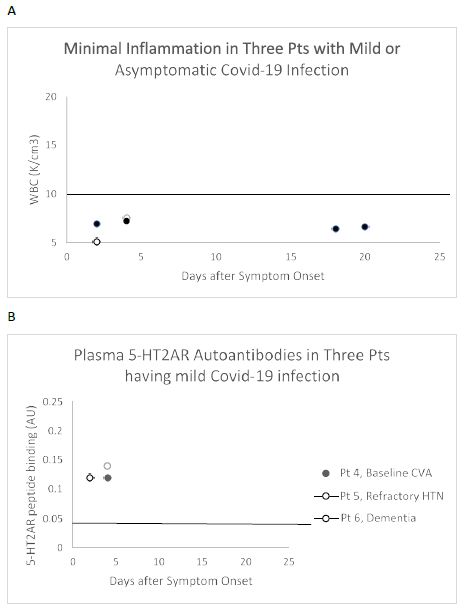

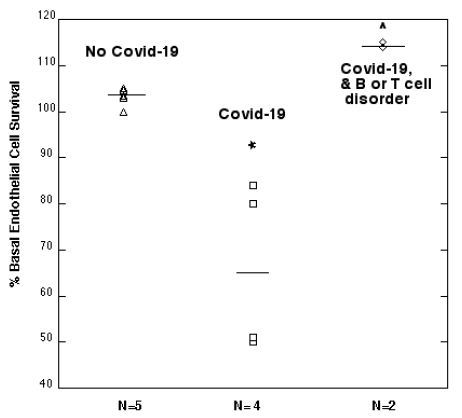

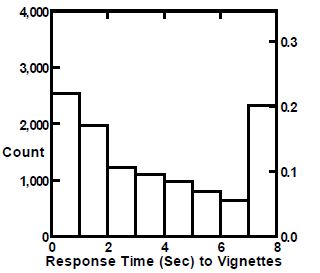

Figure 2 shows the distribution of measured response times for the vignettes, independent of the structure of the vignette and the specific elements. A great many vignettes are rated faster than two seconds, most vignettes rated in fewer than five seconds. As we see below, there is very little difference in the response times linked to the different messages.

Figure 2: Distribution of measured response times for the vignettes.

The final element-level analysis links the elements to estimated response times for the elements. The equation for response time comprises the 16 independent variables, the elements, but does not make provision for an additive constant. The rationale for leaving out the additive constant is that in the absence of any elements (again a hypothetical case) there is no expectation of any response at all.

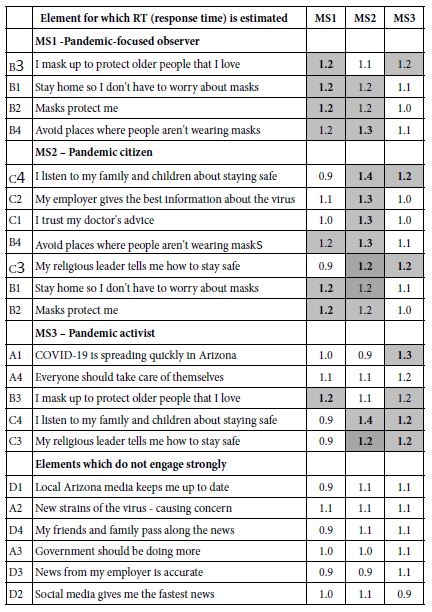

Table 7 shows the estimated response time attributed to each element. The important thing to note is that strong performing elements in Table 5 are not necessarily those with long response times, viz., those which are engaging. Indeed, most of the response times are around 1.0 – 1.2 seconds per element, with a few shorter and a few longer. The results suggest that the respondents do not ‘whiz through’ the elements when making their ratings. They do ‘whiz through’ for other studies, especially the less serious studies having to do with brands and products. Thus, one can feel good that the respondents are actually paying attention to the information, at least in terms of taking the time to read the vignettes.

Table 7: Estimated response time for each element, by each mind-set.

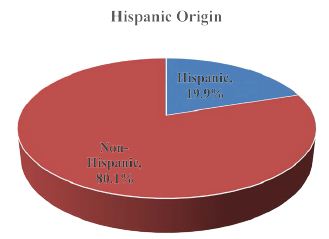

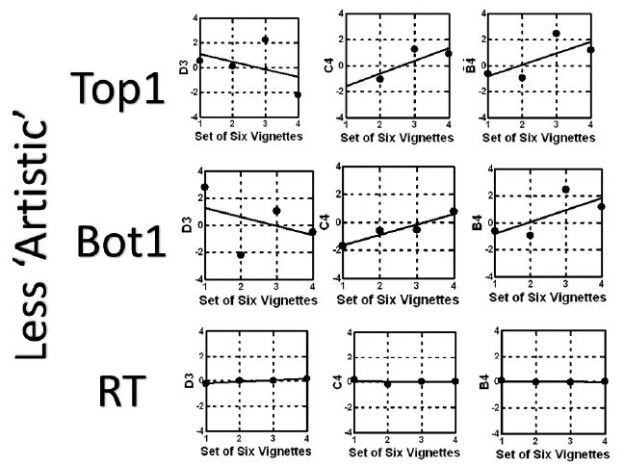

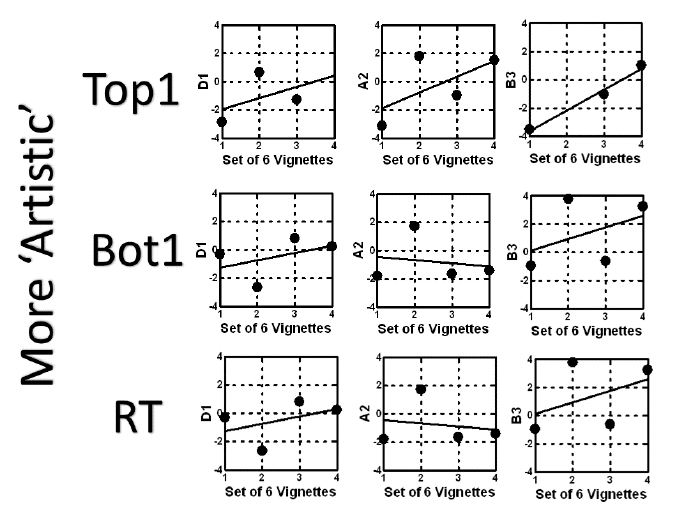

Step 9: Artistic Judgment for Next Steps – Identify the Elements Which have the Greatest Staying Power

One of the ongoing issues in any messaging campaign is the probability that at some time the messages will simply ‘wear out.’ The wear out is habituation, a well-known phenomenon in psychology, wherein the stimulus fails to evoke attention as it continues to be repeated. Experimental psychology demonstrates this phenomenon in rigorous studies, such as the measuring attention reactions of cats presented with the same tone in a steady, expected, repeated, monotonous fashion. Habituation occurs in our everyday life; simply witness people who live near train tracks, and who quickly become accustomed to the noise.

How can we identify messages which have staying power, especially messages which are good to being with? One way to do this uses the actual data from the study. This time, however, the data matrix is divided into equal fourths (viz., vignettes 1-6, 7-12, 13-18, and 19-24). One takes the set of elements to be used in the proposed messaging, viz. one winning element for each mind-set. The selection of the winning element is a matter of judgment, and may involve ‘gut feelings,’ viz., intuition, which move beyond the actual data. The approach here considered only the elements doing well among the three vignettes in the Top1 metric. These were D1, A2, B4:

Local Arizona media keeps me up to date

New strains of the virus causing concern

I mask up to protect older people that I love

These three elements became the only predictors of Top1, Bot1, and RT (response time). The vignettes (fourth = 2, fourth = 3), and for the final vignettes (fourth = 4). By looking at the coefficients for each element across the four sets of evaluations, we get a sense as to whether or not the elements are ‘wearing out’.

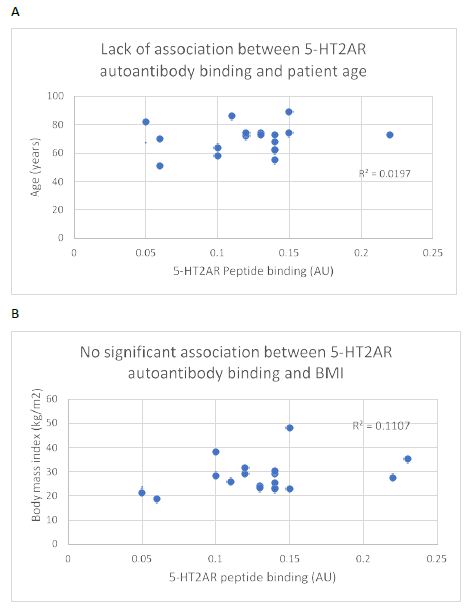

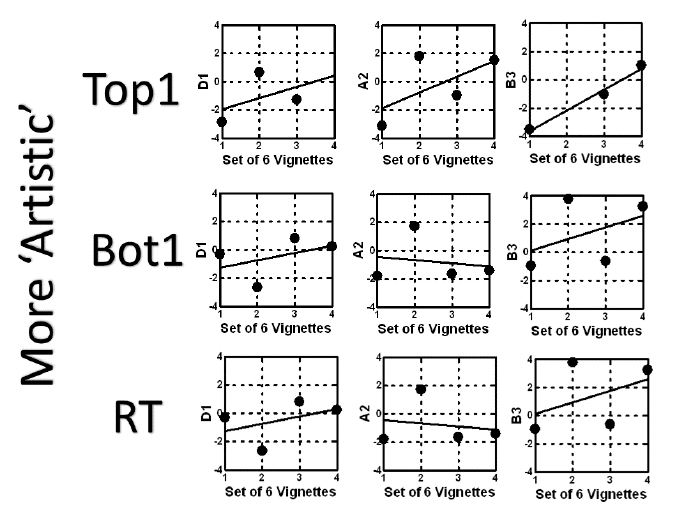

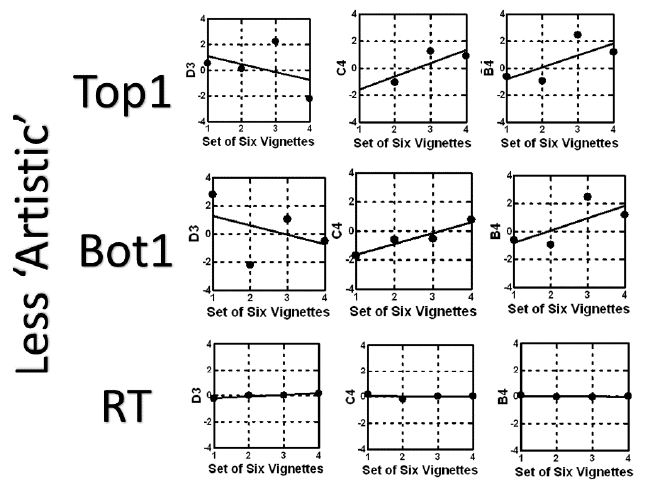

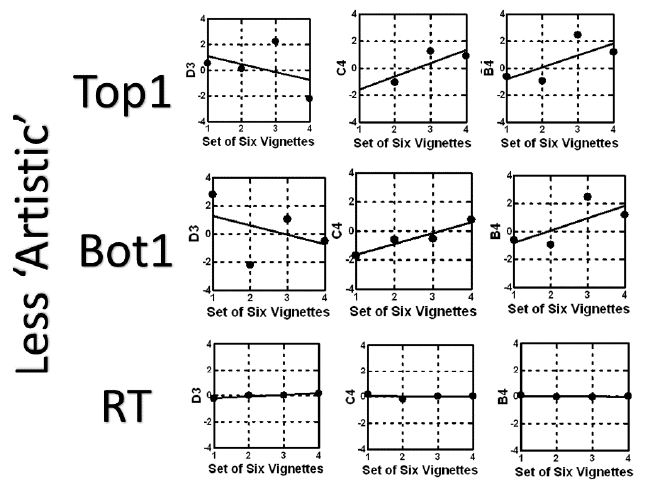

Figure 3 suggests that repeating the messages will enhance the impact of each element in terms of driving the respond to agree to a vaccine (Top1), and for the most part will reduce the resistance (Bot1). The only exception to this general trend is element B3, which shows no loss in negativity with repetition, and perhaps even a slight increase, perhaps resentment at being reminded. The same analysis can be done for any set of messages, to determine whether the messages will change with repeated exposure. Figure 4 show the same analysis, this time for strong performing elements using their coefficients for Top1, but a combination ‘artistically’ sensed as inferior:

Figure 3: Likely wear-out of messages for the vignette which seems ‘more artistic’. The graphs show the expected change of the coefficient for each promising element, when evaluated in sets of six vignettes each. The combination comprises D1, A2 and B3, winning elements from the three mind-sets, selected by artistic sensibility as ‘working together’.

Figure 4: Likely wear-out of messages for the vignette which seems ‘less artistic’. The graphs show the expected change of the coefficient for each promising element, when evaluated in sets of six vignettes each. The combination comprises D1, A2 and B3, winning elements from the three mind-sets, selected by artistic sensibility as ‘working together’.

News from my employer is accurate

I listen to my family and children about staying safe

Avoid places where people aren’t wearing masks

The approach does not replicate the actual events in the world, but rather may be analogous to the process of ‘accelerated aging’ in the world of food science, with the attempt to determine the ‘shelf life’ of a product, so that the product can be pulled from the market shelves before it changes in quality and becomes significantly less palatable [17].

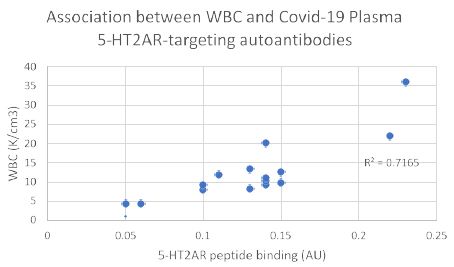

Step 10: Find the Mind-sets in the Population for Targeted Messaging

Ongoing patterns of results from Mind Genomics cartographies, of the type done here, albeit in many other areas, suggest that there exist clearly different mind-sets, but that these mind-sets are distributed in the population in an almost random way, at least to the outside researcher who only has data from who the respondent IS (geo-demographics), how the respondent THINKS (personas based upon large-scale segmentation), or how the person BEHAVES (either in everyday life, or in tracked shopping behavior.)

In none of the standard analysis of WHO, THINKS, or BEHAVES can we find easy covariation with the mind-sets. That is, it is quite unlikely to know how a person will think about a topic just be knowing the typical information available to the researcher. There may on occasion be some happenstance covariation that can be used, but as far as a robust system to link together mind-sets and people, there does not seem to be a recognized tool.

Table 8 shows the distribution of the three mind-sets by gender, by age, and by ethnicity. It is clear from Table 8 that simply finding the mind-set will be difficult in the population. The next best thing is to use set of messages woven together to incorporate the essence of one message for each mind-set, as Figure 3 suggests.

Table 8: The distribution of respondents by mind-set, gender, age, and ethnicity. The numbers in the body of the table are the actual number of respondents who classified themselves at the start of the Mind Genomics experiment, in the self-profiling questionnaire

| |

Total

|

MS1 |

MS2 |

MS3

|

| Total |

494

|

181 |

169 |

144

|

| Male |

192

|

65 |

62 |

65

|

| Female |

302

|

116 |

107 |

79

|

| Age 18-29 |

160

|

62 |

51 |

47

|

| Age 30-49 |

181

|

63 |

60 |

58

|

| Age 50-64 |

79

|

30 |

28 |

21

|

| Age 65+ |

74

|

26 |

30 |

18

|

| Caucasian |

322

|

120 |

118 |

84

|

| Latinx |

85

|

30 |

27 |

28

|

| Other |

81

|

30 |

21 |

30

|

The fact that mind-sets can so easily emerge from data, and be found at any level of granularity desired, and virtually for any topic, in as a fast as one hour, suggests that a new way of thinking is needed to use the mind-set segments. It is no longer sufficient to spend days, weeks, or months cogitating over the application of mind-set segmentation when the actual results had been obtained in a matter of hours.

During the past four years authors Gere and Moskowitz have worked on algorithms to classify the respondent as a member of a mind-set, recognizing that the algorithm should be quick to develop, easy to implement, and inexpensive. The algorithm also must minimize the ability of a respondent to ‘game the system,’ by guessing what the interviewer wants to hear.

The approach developed emerges out of the actual experiment and data set used to create the mind-sets in the first place. This first step ensures that the elements used to assign a new person to a mind-set are relevant to the topic, moving away from the potential error-propagating step of searching for other language that can be used for assigning the respondent to the mind-set. This first is close in, and immediate. As soon as the mind-sets are determined so is the performance of each element for each mind-set.

The second step uses a Monte Carlo system to introduce noise, and then assign respondents to the mind-set in the present of the noise.

The third step aggregates the data and generates the decision rule which is most resistive to the introduced ‘noise’ and correctly types of the mind-sets in the presence of the noise.

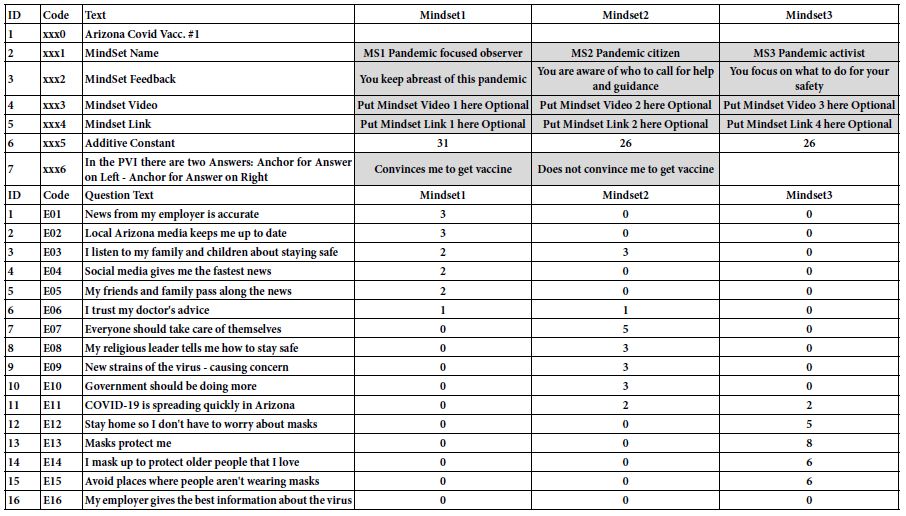

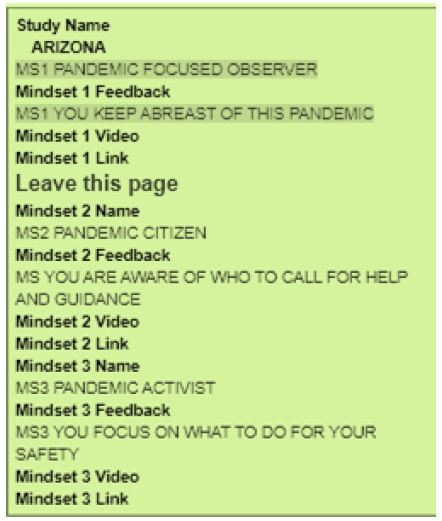

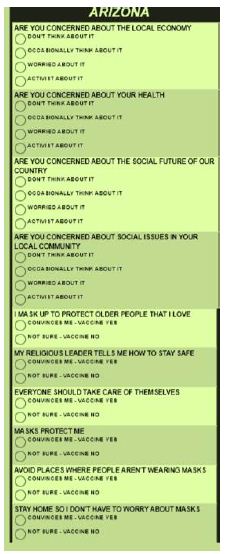

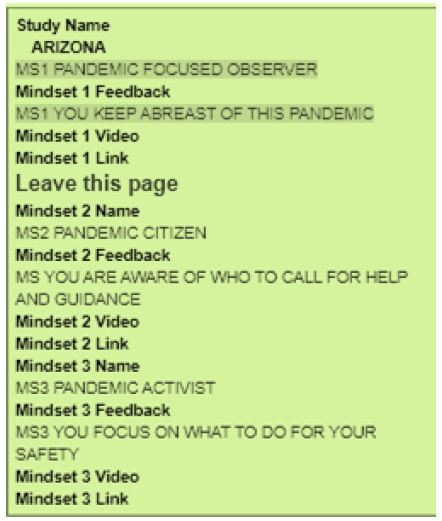

The resulting approach is called the PVI, the personal viewpoint identifier. The set-up is done according to a Microsoft Excel template (Table 9). The template requires the researcher to provide specific information about the mind-sets (viz., name, feedback), as well as an optional video or landing page corresponding to the mind-set, right after the respondent is assigned to one of the mind-sets. At the bottom of Table 9 is the summary data from the mind-sets, used by the PVI to create the actual calculation table.

Table 9: Template for the creation of the PVI (personal viewpoint identifier).

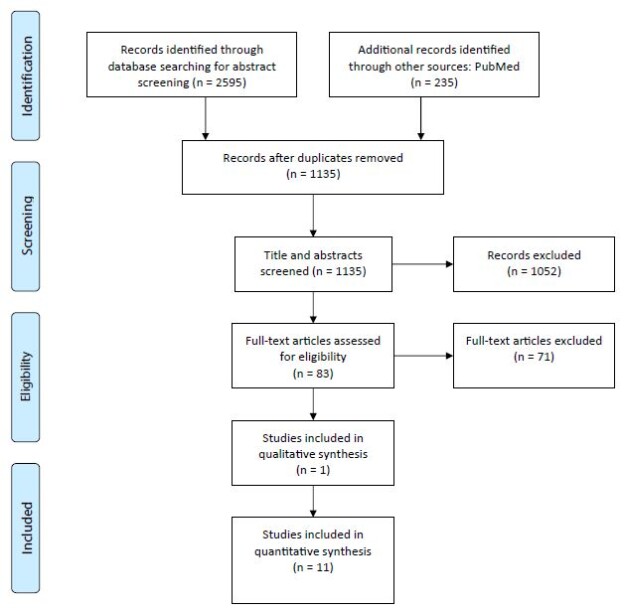

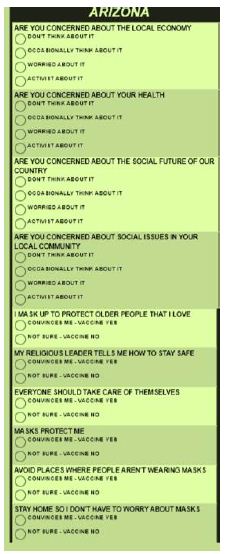

Once the input in Table 9 has been processed to create the PVI, the result comes back in a link. The respondent who clicks on the link is led to the PVI on the web. Figure 5 shows the introductory page, which introduces the respondent to the reason for the short study, obtains permission, and obtains background data. Figure 6 shows the set of questions, comprising background questions (not part of the classification algorithm), and six questions answered by one of two answers. These six questions are the PVI. Each respondent sees the six questions in a different order. The data are stored in a database for further work, and the results sent back to the respondent either in a detailed form, or just an email with mind-set membership, and something about the mind-set to which the respondent belongs (Figure 7).

Figure 5: The orientation page for the PVI. The link (as of January, 2021) is: https://www.pvi360.com/TypingToolPage.aspx?projectid=1270&userid=2

Figure 6: The questions about one’s concerns, and the six questions for the PVI.

Figure 7: Feedback page for insertion into the database. The respondent receives a simple email showing the three mind-sets, viz., their names and the feedback, as well as the mind-set to which the respondent belongs. This example is from a person in Mind-Set 1, the Pandemic Observer.

Discussion and Conclusions

The study reported here typifies what, in the emerging science of Mind Genomics, is called cartography, for want of a better word. The cartography is not designed to test hypotheses, in the traditional view of some scientists [18]. There are no working hypotheses to falsify. The cartography, as the word connotes, explores the topic, and maps its detailed features. Here the features are the words. As we begin to create cartographies, there are usually several sequential cartographies or iterations. At the start we need not know whether the questions are the correct ones, and certainly whether the answers are correct or event relevant. Yet, we do the experiment, we put a ‘stake in the ground,’ discover what works and embellish it, discard what does not work, and then add new material for the next iteration [19].

Although this might not seem to be the most elegant way of creating a database, it certainly is the quickest, and in fact allows the database to create to be created by all sorts of people, whether these are professionals in the healthcare world, patients, doctors, or hospital administrators, or even relatives of those who are patients. The notion is not to get it right, because there is no ‘right’ – at least not at the start. Rather, the notion is that through responses to descriptions, the vignettes, the underlying patterns will emerge, in the way the underlying structure emerges from the many pictures taken by the MRI and reassemble the structure after the fact through a computer program.

A key benefit of Mind Genomics is its availability to anyone, expert or amateur alike, and the possibility that the discoveries may be made by virtually anyone. A dedicated analyst working with dozens of transcripts of interviews lasting an hour or two about the topic might emerge with similar findings, but not as crisp, nor as data rich. In contrast, the novice but avid researcher, can do an iteration overnight, following the templated approach of Mind Genomics. The templated approach forces the research to focus on the messages, do the experiment, obtain the data, and face the bare facts, specifically how the messages drive the response. The data are archival, the learning is incremental and expansive, and the result resides in a searchable data warehouse, ready for reanalysis to provide new insights. The information can be searched for words, for meanings, and for new correlations, done, at virtually any time after the study, and by virtually anyone. These data from the first study on COVID-19 in Arizona give a sense of the potential.

Practical Conclusions – Driving Vaccination in Arizona

The focus of this paper is both on method and on results. Both are important during this period of the COVID-19 pandemic. The rationale of showing what can be done in one day is not so much to provide a perfect answer or write a perfect paper, as it is to show a revolutionary change in what could be learned in a short time at a low cost. Cost, time, and the power to iterate to a better answer are important for the obvious reasons; costs of medical treatment and of medicines are increasing, making prevention increasing attractive. The more that we can learn about people ‘in the moment’ with respect to issues which emerge, the more likely it will be that we can communicate more effectively with people. This communication includes providing the necessary information and the suggestions, both tailored to the mind-set of the person, and perhaps both more convincing, more motivating. It is no simple thing to motivate people. The faster and easier it becomes to learn the necessary facts and words, ideally in ‘real time,’ the more likely it we be that people will be guided gently, through words, to live healthier lives, and to take better care of themselves. The cost of the medical interventions might be lower.

The data here suggest that it is vital to consider the different mind-sets of respondents. In light of the speed, ease of analysis, and low cost, as well as a tool to determine the mind-set of the respondent, the prudent action would be to do one to three or four Mind Genomics cartographies, as done here, eliminating the poor performing elements, and building upon the elements which look like they work. Table 6 shows the dramatic increase in performance of elements, and the clearly different mind-sets. Several more cartographies, each last no more than a day, should build a new set of ‘Table 6’s’ with increasingly strong performing elements. It is unlikely that there is a single ‘magic bullet,’ for all mind-sets, but there are clearly a number of strong elements for each mind-set.

Acknowledgments

Attila Gere thanks the support of Premium Postdoctoral Research Program of the Hungarian Academy of Sciences.

References

- Benyamini Y (2011) Why does self-rated health predict mortality? An update on current knowledge and a research agenda for psychologists. Psychology & Health 26: 1407-1413. [crossref]

- Benyamini Y, Blumstein T, Lusky A, Modan B (2003) Gender differences in the self-rated health–mortality association: Is it poor self-rated health that predicts mortality or excellent self-rated health that predicts survival? The Gerontologist 43: 396-405.

- Dulmen S, Sluijs E, Dijk L, Ridder D, Heerdink R, Bensing J (2007) Patient adherence to medical treatment: a review of reviews. BMC Health Services Research 7: 55. [crossref]

- Boodoosingh R, Olayemi LO and Sam FAL (2020) COVID-19 vaccines: Getting Anti-vaxxers involved in the discussion. World Development, 136: 105177. [crossref]

- Burki, T (2020) The online anti-vaccine movement in the age of COVID-19. The Lancet Digital Health 2: 504-505. [crossref]

- Kennedy AM, Brown CJ, Gust DA (2005) Public Health Reports 120: 252-258. [crossref]

- Zimet GD, Rosberger Z, Fisher WA, Perez S, Stupiansky NW (2013) Beliefs, behaviors and HPV vaccine: correcting the myths and the misinformation. Preventive Medicine 57: 414-418. [crossref]

- Gere A, Zemel R, Papajorgji P, Moskowitz H (2019) “Candy Is dandy”: The mind of sexuality as suggested by a Mind Genomics experiment. In Sex, Smoke, and Spirits: The Role of Chemistry, 17-31.

- Sullivan, GM, Artino Jr AR (2013) Analyzing and interpreting data from Likert-type scales. Journal of Graduate Medical Education 5: 541-542. [crossref]

- Bellissimo, N, Gabay, G, Gere, A, Kucab, M and Moskowitz, H (2020) Containing COVID-19 by Matching Messages on Social Distancing to Emergent Mindsets: the Case of North America. Int J Environ Res Public Health 17(21): 8096 [crossref].

- Kahneman D (2011) Thinking, Fast and Slow. Macmillan.

- Gofman A, Moskowitz H (2010) Isomorphic permuted experimental designs and their application in conjoint analysis. Journal of Sensory Studies 25: 127-145.

- Stevens, personal communication to Howard Moskowitz, 1968.

- Moskowitz HR (2012) ‘Mind Genomics’: The experimental, inductive science of the ordinary, and its application to aspects of food and feeding. Physiology & Behavior 107, 606-613. [crossref]

- Moskowitz HR, Gofman A, Beckley J, Ashman H (2006). Founding a new science: Mind Genomics. Journal of Sensory Studies 21: 266-307.

- Jain AK, Dubes RC (1988) Algorithms for Clustering Data. Prentice-Hall, Inc.

- Schwarz M, Rodríguez MC, Sánchez M, Guillén DA, Barroso CG (2014) Development of an accelerated aging method for Brandy. LWT-Food Science and Technology 59: 108-114.

- Popper KR (1963) Science as falsification. Conjectures and Refutations 1: 33-39.

- Benyamini Y, Idler EL, Leventhal H, Leventhal EA (2000). Positive affect and function as influences on self-assessments of health expanding our view beyond illness and disability. The Journals of Gerontology Series B: Psychological Sciences and Social Sciences, 55(2), P107-P116. [crossref]