Abstract

The menstrual blood considered impure, dirty and contaminated in Jumla, a place of research for menstrual restriction and its impact on empowerment where the qualitative method, feminist ethnography employed, through three different methods: history/timeline, participant’s observation and In- Depth Interviews. The restriction during menstruation is very complex, vary from person to person, contradictory position between practice to practice within same person or family. The participant followed 29 types of restrictions related with food, touch and mobility during their menstruation. Because of these restrictions, girls and women deprived from access to food, water, shelter, mobility, hygiene, health, education. As a result, they felt isolated, inferior, disempower, deprivation from participation in school, social activities/celebrations and losing dignity. These situations contributed for compromising rights assured by the constitution of Nepal and considered as violation of human rights. Here, the restrictions during menstruation played a role to construct and shaped the power among girls and boys. As a result, the all aspects of the girls and women’s life affected and eventually they deprived from the empowerment.

Keywords

Menstruation, practice, restriction, women’s dignity, empowerment

Introduction

Globally, depending upon the areas of residence, school’s norms, parental guidance, media etc. few girls and women aware about the menstruation [1] where as many rural, tribal and even educated girls and women do not aware about the menstruation [2]. This kind of experience is very common in Nepali society even school going adolescent girls [3]. Nepalese community considered the menstrual blood as impure, dirty and contaminated that established by religious books, schools and informal institutions. As a result, girls and women are following multiple levels of restrictions during menstruation as common practice in Nepal. Among the development work, media in Nepal and beyond the word Chhaupadi is popular since MDGs (Millennium Development Goals) which as restriction during menstruation. The restriction during menstruation outlawed in Nepal since 2005 and there is law against any forms of discrimination, exploitation, violence during menstruation since 2018 (“Nepal Law Commission – NLC,” n.d.). There are schools of thought regarding the cause of practicing restrictions during menstruation. It has been in practice due to illiteracy, superstition and gender inequality revealed that the concept of impurity and poor menstrual hygiene impacted for Millennium Development Goal (MDG)-two on universal education and MDG -three on gender equality and women empowerment. Likewise, menstruation has multiplier effect for achieving the Sustainable Developmental Goals especially to goal five for gender equality.

Since the 2014, there are few studies started to take place in Nepal and globally that were most focused on hygiene. In Nepal, such studied conducted for the academic purpose as well as NGO’s intervention. Thus, the studies that encompass on consequences due to following the restrictions during menstruation is not available except some opinions in media and activism for instance for 2017, Jyoti Sanghera, a pioneer activist stated that the stigma during menstruation is violation of dignity including violation of several human rights [5]. The menstruation played a crucial role to bring equal position in holding power, participation in decision making at family and workplace [6].

In this connection, this study took place to provide the critical view on impacts of menstruation on empowerment of girls and women with following research questions:

i) What are restrictions practiced during menstruation?

ii) To what extent, the education affects by the menstrual practice?, and

iii) What are the impacts of menstrual restrictions on empowerment?

Methodology

This study employed the qualitative approach where applied postpositivist world view with feminist ethnography for the change at the life of women and society by questioning the policies and demands for social transformation [7]. Chandanath Municipality, Jumla district is the site for data collection due to accessible by bus, cost, time compare to others areas. More importantly, this community has been practicing restrictions during menstruation [8]. In order to avoid the reflexivity, the purpose and process explained with gate keepers. The participants for data collection identified as guided by the gate keepers till the saturation of data. The ethics maintained by securing the approval from National Health Research Council (August 2017) and obtained verbal and written consent. As suggested by the Elana D. Buch & Karen M. Staller, [9] primarily, the three types of methods: history taking/timeline, participants observation and In- Depth Interview employed in order to get rich data around menstrual practices. The interview guide, observational check list used for collection of data. The participants identified through gate keepers as well as snow ball methods specially to find the menstrual girls and women.

Life history/Timeline

The total four menstruating participants between 28-40 years identified. They all represented married and followed Hindu religion. Regards to caste two were from higher caste and the remaining belonged with Dalit and Chhetri respectively. Except one, all participants never ever been to school and three worked at home.

Participatory Observation (non- participant to participatory)

The six menstruating, married participants considered for participatory observation for three days. Out of six, two were never ever been to school, two were belonging with Dalit and rest of them belong with higher caste. And, three were working as health workers, two worked as house wife and one was student.

The place or location, clothing (during menstruation and after), physical gesture and sitting/sleeping, interactions (family and social), physical appearance, personal behaviours/emotions/feelings, key influencers, food/liquid intake, restrictions (private, public), mobility, used and management of sanitary materials, cleanliness observed [10].

Mass observation

Two mass activities; Teej celebration (Annual festival specific for women called red colour festival as well) and Temple observation observed.

In-Depth Interview with Key Informants

The total number of participants was 17 (Female -8, Male-9). All the female ranges from 14 to 80 years of age and have experienced of restrictions during menstruation. Regards to occupation, they belonged with teaching, health service provider, faith healers, journalist and housewife. Except three females, all were married. Regards to education, except one participant, all were educated. In terms of caste, only two participants were belonged with Dalit.

The data and informational triangulation through multimethod approach, probing questions as well as follow up visits during field visits. The field notes, videos, photos used to verify the information. The data started to analysis since the data collection. It was iterative process of collection of data and analysis. The data transcribed, coding, and generate themes. For ensuring the accuracy, the data corroboration with various sources of data. In order to ensure the grounded of data, logical inferences, appropriate themes, justified decisions and methods, credibility and biasness, the research process and analysis reviewed by peers and supervisors time and again as a form of eternal audit.

Results

Restrictions on Touch during Menstruation

Since menarche, participants were avoiding to touch various things by considering the menstrual blood impure. During menstruation, girls and women not eligible to touch places (foundation of house, house, kitchen, temple, toilet), person (male member, faith healers, seniors, priest,), things (tap, river, intercourse, book, cattle, clothes), and plants of vegetables and fruits.

Restrictions to Eat during Menstruation

Menstruators prohibited eating rice, vegetables, fruits, milk products, prasad, meat products, beans, sour foods during menstruation.

Restriction to Work/Mobility/Participation during menstruation

Menstruators restricted in mobility, cannot work inside the house, same road or place as seniors walk/work, around the temple, meetings and cultural celebrations.

Impact on Empowerment

The perceptions, practices and understanding around menstruation have been reflecting the impact on empowerment at individual, organizational and community level and overlapped each other [11]. The feminists considered the empowerment as mutually strengthening and intersecting the sub process where the problems identifying and deconstructing for action and critical reflection 12].

Due to restrictions, there is impact of education and health that overlapping each other and impacted to the lives of girls and women throughout the life. Girls and women do consider the menstruation as matter of shy, stigma, and taboo instead of biological process and pride. Simultaneously, their knowledge, attitudes, and practices pulled down the confidence of girls and women to see them as equal human being as boys or men.

Control of Body of Girls and Women during Menstruation

The imposed restrictions connote the lower status than boys. Those kinds of understanding started to build since age of fivenine years from their mothers, sisters, friends, other relatives and neighbourhood. This brings the `powerfulness’ for boys whereas the `powerlessness’ to the girls. Menstruation appeared as tool to construct the power since childhood. The boys possess the Power Over Decisions and girls resembles the Power over non-decisions according to the power theory [13] McCabe, n.d.).

Before menstruation, girls started to see themselves as humiliation and inferior than boys whereas boys are socializing the opposite direction. In addition, girls lost their dignity and peace of mind since childhood.

The isolation and exclusion from the home and regular activities, for five to seven days in a month has served the status of girls and women due to menstruation. Further, the living status gives the idea of menstrual girls and women are lesser than domestic animals.

Boys, teachers and girls know that the girls have menstruation from her absence of school during menstruation and drop off the class in between. Because menstruation considered as matter of shyness/ stigma/taboo. Such situation further amplifies the state of impurity for menstrual blood. Because of such understanding, girls cannot concentrate on class if they joining during menstruation. They lose their self-esteem, confidence within themselves and lose their dignity in the public. Participants shared that they felt like they are doing any act like crimes thus they felt so guilt while having menstruation and more shame and guilty if anyone knew without letting them directly.

“During my first menstruation, I missed the class for five days. I felt so embarrassed and powerlessness while joining the class next week. I was so flushed to see the faces of teachers and boys in class due to shame and feeling that I committed crime. Because they know automatically if any girl missed the class like this’’.

IDI_Healthworker_Female_5

Due to restrictions, menstruation considered as women’s private business thus girls and women feel humiliated and disempowered. Men never menstruate but they keep learning since about four to nine years old from their sisters, mothers, aunts, relatives and neighbourhood. Almost all of them agreed that they discussed about the menstruation among themselves (secretly). Boys gained the power that they never been menstruating means pure, higher, privileged than the girls. They started to see not only girls are inferior, low status but also started to learn to govern their ideas and body like do this and do not this since childhood to their sisters, friends and others.

As men grow by, their parents, faith healers, seniors are asked to follow the restrictions by limiting themselves because of state of impurity of women. There is a long list of` Do’ this and `Do not’ this regarding to menstruation. As a result, they strongly believed that menstruation is impure state, made by god and men should not contaminate with menstruating girls and women at all. Because men have posses’ superior position by god, men have outstanding power than women. Thus, men see themselves as governor, power holder wherever they are.

Feeling of Inferior

Regardless of caste, class, education and occupation, all female participants felt deeper level of humiliation, inferiority since they menstruate. One of the participants shared her first feeling from menarche was losing myself (aba ma sakiye -IDI_adolesent girl_17). The dehumanization and inferior complexity are deeper and stronger due to compromises the biological needs and social needs such as food, drink, shelter, sleep, security, mobility and isolation from the friends, family, affection, relationship. Participants verified themselves that the menstrual blood and menstruating women is really `impure’, `dirty’. Few close friends were visiting at shelter and often accompanied though they all confirmed that they are real `powerless’ creature in this world because their esteem needs such as self-esteem, achievement, mastery, independence, prestige etc. were heavily scrutinized. Meantime, they also so much confused with the imposed list of restrictions during menarche which were incompatible with learnings what they learned from formal education regards to purification process including cleansing with cow’s dung and urine, spray of golden water. They were depressed with lots of imposition including putting loads of responsibility to women followed by menarche.

Since the first day of menarche, participants experienced surprised, shocked, sad due to ignorance about menstruation, management of blood, the norms or lists of `Do’ and `Do not’ associated with menstruation. Continuously, they felt humiliation, disempower and lower than men. Due to inaccessibility with food, shelter, water, mobility, participation, they equally experienced humiliated, inferior and disempower. The purification process is mandatory and important even during the season of snowing and state of sick. However, all participants thought that the purification process also changed already.

“In the past, we used ash to wash for purity. Now we use soap, surf to wash cloths in river by slapping in stone. I, myself, use the shampoo for washing my hair, use tika on forehead. There are so many instructions for do and do not that make me sad, inferior and frustrated’’.

Timeline/History Talking_Female_3

All participants know that the menstrual girls and women are even not allowed to touch foundation of the house since childhood and often feel inferior to boys and men. Such feeling rises even more after their menarche. They feel themselves less recognized compared to male at family and community. They do not feel that they have any power or authority over the property of the family though they work so hard than boys and men. Participants shared that they often considered themselves as persons with less value. The restriction for not allowing to touch foundation of the house caused them disassociated with their own family and confirmed the feeling of inferior human being in this universe due to impure menstrual blood.

As like the restrictions, not allowing touching the foundation of the house, the restriction for entering into the house resembles the feeling of sad, sorrow, feeling of insecure, low confidence, low status than man. Because of the heavily compromised the biological needs such as food, air, shelter, hygiene, love affection, family etc. which are important for girls and women during menstruation.

Almost all participants including elders shared that they were so frustrated due to not allowing entering into the kitchen. They said that they have to be deprived from the getting food and water when they got hungry and thirsty. They tired up and losing their dignity while requesting and pleasing siblings/children/in laws. Most of the participants simply gave up them to please means they just waited whenever they gave. Few participants just went to bed without having food.

Because of the restriction to avoid touch with men members, girls and women lose their self -esteem, confidence and dignity as well as considered themselves as inferior and low status than men. In addition, participants also deprived from participation in activities related with learning, entertainment, social cohesion and development. Because the men are everywhere at home, school cultural gatherings and meetings at village council.

Due to the supremacy attitude and practice of seniors, the participants had `scared’ `irritating’ feeling towards seniors. They felt embarrassed, humiliation, inferior and often dehumanization’s from the comments passed by the senior. This culture is one of the pushing factors at family and community to engage in voluntary child marriage.

Feeling Isolated

The both deep ignorance and silence and emotional stress including sad, hopelessness, dying soon, crying, feeling isolated pushed participants towards disempowerment during menstruation and rest of the months.

Deprivation from Participation

The joining in a meeting is a form of participation of political process at community. The deprivation as well as the emotional and physical abuses both were double the reverse impact on empowerment. Once, they failed to exercise their rights here, they would fail to claim in municipality political process.

Losing the Dignity

The restriction for not touching the plants of vegetables and fruits promote the condition of deprivation of seasonal nutritious foods which is violation of right to food, right to dignity, right to mobility. Further, these situations created the emotional unwillingness which leads deep psychological trauma. The restriction for not touching the cattle leads disempowerment for girls. Few of them, expressed their anger and frustration against such restriction because they were responsible even during menstruation to cut grass, and graze them but not allow having it. They felt humiliation by considering the low status than the animals.

Restriction to touch toilet during menstruation negatively impacted to learning and health issues e.g. attacked by the wild animals, experienced sexual abuse including rape.

Touch has directly connection with right to dignity and right to participation or mobility or touch of the girls and women during menstruation that is assured by the constitution of Nepal (“Nepal Law Commission – NLC,” n.d.). They also deprived from safety, security, confidentiality, enough water to clean clothes and body etc.

Due to no access with clothes, adequate and nice clothes. These circumstances established the feeling of low status and humiliation among participants.

“I wanted to participate the festival at market with hiding my menstrual blood but I could not participate because my mother scolding that I should not use such new clothes during menstruation. If I were using these clothes during menstruation, I could not use these clothes in any programs for future due to concept of contamination with impure menstruation. The more I remember; I still feel more humiliation and anger though I am against of these naughty cultures’’.

IDI_Health Worker_Female_11

In the beginning, the female participants were spontaneously expressed their believes and practices regarding the reason of restrictions to have milk and milk products. Later, when they discussed deeply about their first feelings and impact, they appeared sad and unhappy. They said that this practice is visible form of discrimination towards girls and women and key reason of being weak. In earlier days of menstruation, they cried, they felt regret as being born girl, they fought with their parents and seniors and even they thought to end their life.

The restriction of not allowing to walk around temple also accelerating the disempowerment among female participants. Because of such practice, girls and women feel underprivileged and disadvantages than men. They feel humiliation, discrimination and anger towards the society, family then themselves due to unable to join in the public activities such as sports, group meetings, celebrations etc.

They had experienced of double victimization due to menstruation and also scolded by the neighbours while they were watching the celebration and meetings from distance. Often the religious or other activities were cancelled due to menstruation where menstrual women got blaming of all lost and reschedule.

“The status of menstruation is the foremost enemy and hateful thing for women. “Sometimes, I pushed myself and tried to join the cultural program but I had to stay and observe things from very distance. Sometimes, the women shouted even observing from distance. They became sad and angry if the menstrual woman is in front them. They believed that they were attacked by god and shaken (Paturne). People even do not allow to plant and gardening in the field at the beginning. The non- menstruating women start and then they allow menstrual women to enter in to field in farm. We are supposed to postpone the religious and cultural activities such as worships, weddings if the women menstruate at the house of hosting’’.

Life History//Timeline_Dalit Women _2

“I do not like to go anywhere because I often feel so weak and lazy and like to lie down.

At bed throughout the period. I often lose my appetite because of discomfort. My culture does not permit me to participate to any marriage ceremony and even religious activities. I am only allowed to go to field for work. Many times, I had to cancel my visits to religious activities with other family members after menstruation’’.

Almost all participants including men said that the menstrual women have rare chances of interactions with older and religious people. They can only interact with limited people such as daughters and female friends. The impact of menstrual restrictions, stigma has hit all aspects of life of girls and women in many ways. Because of restriction, they started to missed out the classes or poor attention on learning and education. Then they started to failing in subjects and eventually stop to go school. Some of them just trapped with early or child marriage because of dismissal of their dream on education and life. It is really complex to understand.

“I am 14 years old now studying at grade ten. It is only 5 minutes walking distance. I do not like to go school for 3-5 days during menstruation. I did marriage just six months before forcefully. My new role as married woman got much workload in the family and caused fail in English. Now, I am bit confused to continue my study or not’’.

Participants Observation__ Adolescent Girl_Dalit _6

Working in the field and collecting firewood or fodder is not a problem at all. But the problem is they have to work in pressure. They have to finish the work within bleeding days otherwise they cannot concentrate these works due to the work at inside the house. This is form of discrimination, violation of human right especially right to dignity, right to freedom, right to choose, right to food etc which is guaranteed by the constitution of Nepal.

Disempowerment due to Deprivation from Learning

Deprivation from learning and quality education, is a serious form of disempowerment. The level of chronic emotional unwillingness, deprivation from quality educational opportunities and trapped early or forced or voluntary marriage of girls, pushed further form of disempowerment.

“The situation was different in the past. In my case, I even, did not send my daughter to school after menstruation. She got marriage and sent to her husband’s house. The same situation applies to some of my relatives as well where daughters have to leave school after menstruation even at present. Now, situation seems changing gradually. Now, I myself prefer to send them to schools though few restrictions still exit in the society.”

IDI_Elder Women_12

The deprivation from touching the source of water supply means deprivation access to water supply. They disempowered from the perspective of health and dignity. The water for drinking and hygiene or clean both the basic need for humans. Participants expressed their frustration from this practice which is unavoidable at all.

‘`I have bitter experience when I got first menstruation in my life. I was not allowed to touch water for 15 days, though I got permission to stay inside my house and eat food without touching other members in the families. I was treated as beggar that made me so frustrated and angry. Even for bathing, I had to go to irrigation canal’’.

IDI_Healthworker_Female_11

Those girls and women who do not follow such restrictions, they have confidence to behave in front of all. Among the participants who represented dalit and Tibetan group, and were working at local hotel said that they never experienced discrimination and nobody asked them to follow restrictions during menstruation. They said they were serving food items to all people including even priests. They said that;

“We belong to dalit and Bhote caste people and work at this hotel for years. We do not make our menstruation period to public and do not follow any restriction as upper caste women follow. We do everything here from cooking food, serving to costumers, cleaning at kitchen, rooms and everywhere’’.

Informal Meeting_Feamle_Lama

During menstruation cycle, women are not allowed to work inside the house due to state of `impurity’ and `dirty’. This is very powerful instruction to dominate the status of girls and women since childhood even before having the menstruation. In Jumla, the kitchen is the primary level of parliamentary where the family members review their daily activities, share the common issues from neighbourhood and plan for next day and future but women in menstruation period have to miss the opportunity to participate among family members. The participants however, were found themselves as victims of social discrimination.

The youth participants said that during their menarche, even the girls from the educated families, were not allowed to go schools due to scare of contaminations. It even applied to those who were not at school. Such restriction not only hampered to their education but to their participation at household activities. The incidence of child marriage connected to menstruation however, was not perceived well. Regarding this, a female local politician said:

`I do not know why the practice of child marriage is rampant in my community. Though the Municipality is organizing various awareness raising activities, there is no impact yet’.

IDI_PoliticalLeader_Female

Discussion

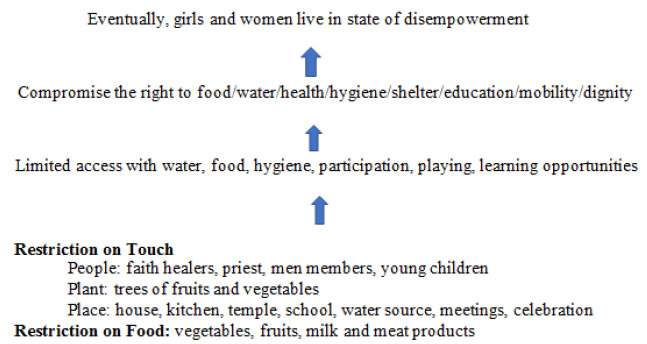

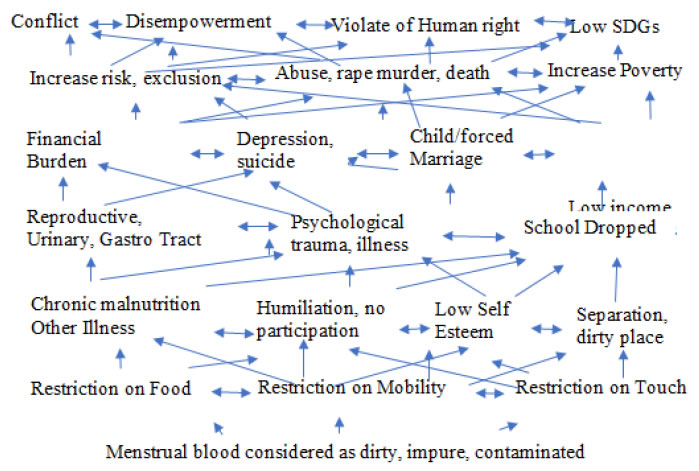

Among 29 different restrictions, few are overlapped and interlinked with each other. These restrictions hit all aspects of the life of girls and women in many ways. As like restrictions, the impact also overlapped and interlinked each other.

There are various ways of defining empowerment, primarily focused on gaining power and used as key concept in almost all discipline [14]. Menstruation has significance role on life of girls and women from womb to tomb and all aspects of the life where they may or may not gain power.

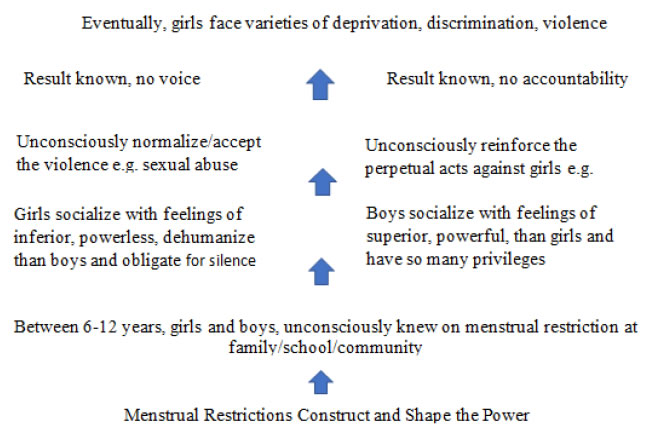

First and foremost, menstruation associated practices constructed the power at an individual level of boy and girl and at institutional. Both girls and boys started to learn the menstruation since young childhood. Without knowing any logic, girls see themselves as like mother who have to work hard, dominated by the men members, powerless due to the state of impurity of menstrual blood. It has similarity with the believe of Rappaport (1987) where the empowerment as process of gaining mastery by people, organizations and Communities, happening at multiple levels [15]. Since childhood menstruating girls and women kept actively engage with their community and an understanding the socio-political dimension around them instead of having observations or self-perceptions regards to menstruation. In this vein, [11] emphasized that that psychological empowerment is more than self-perceptions.

As time passed by, girls started to cope with all consequences brings by menstruation. They do without any questioning, challenging even they do belief in such a deep way where they see logic against restrictions. They see these restrictions as part of culture, order from the god, who make and put everything in order. Consequently, they started to realize that the sexual abuse, domestic violence, rape, intimate partner violence, deprivation from opportunities etc. are all happening because of discrimination against girls and women due to their state of impurity. These are the form of violence but they do not have courage to speak due to deep feeling of powerlessness and hopelessness. Eventually, girls and women converted as victim. In alignment with this, the close tie was revealed between restrictions during menstruation and gender based violence including rape [16]. The state of powerlessness is constructed and learned by menstruating girls and women through the observation, past experience, ongoing practices, behaviour and thinking patterns before, and during the menstruation. Feminist believed that the powerlessness or oppression or deprivation is the outcome of both socio-economic and psychological factors [17]. Further, this study emphasised for understanding the material reality of oppression. In contrary this, powerlessness considered as more than lacking power including inability to cope with emotions, skills, knowledge, lack of self-esteem including lack of external supports [18].

Meantime, boys considered themselves more powerful, superior, privileged at home and community due to the state of purity or no menstruation throughout the life since god’s time. As time passed by, boys started to provoke with all consequences brings by menstruation. They denial to do, arguing even they do belief in such a deep way where they see logic against restrictions. They described these restrictions as part of culture, order from the god, who make and put everything in order. Consequently, they started to realize that the sexual abuse, domestic violence, rape, intimate partner violence, deprivation from opportunities etc. are all happening because of discrimination against girls and women. These are the form of violence but they do remained silence due to deep feeling of powerfulness and state of privileged. Eventually, boys converted as perpetrator.

In this vein, the Garg et al., [19] Johnston-Robledo & Chrisler [20] agreed that the segregation due to impurity and restriction regarding touch, the girls considered themselves inferior, negative feelings towards their body. As Rembeck et al., [21] believed the girls and boys self-esteemed and self-agency built since childhood where the family played a vital role for that and influenced by and from menstrual practice. In this vein, Johnston-Robledo & Chrisler, [20] argued that the lower status of women was determined by menstrual stigma and taboo in the family and community.

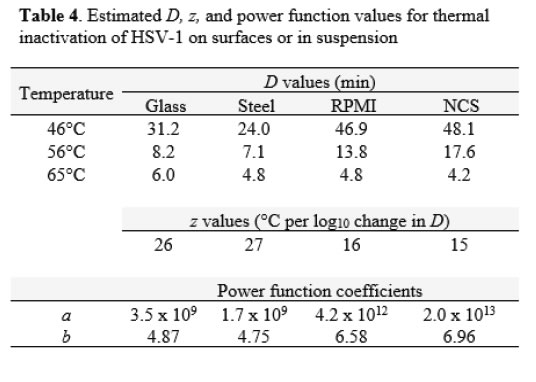

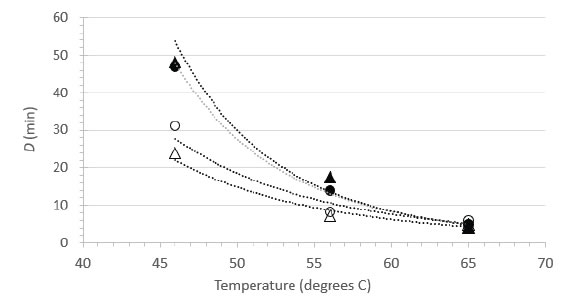

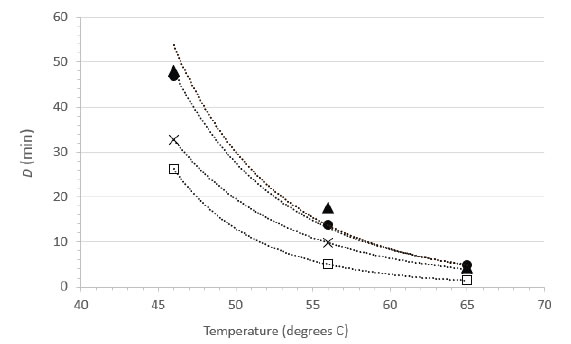

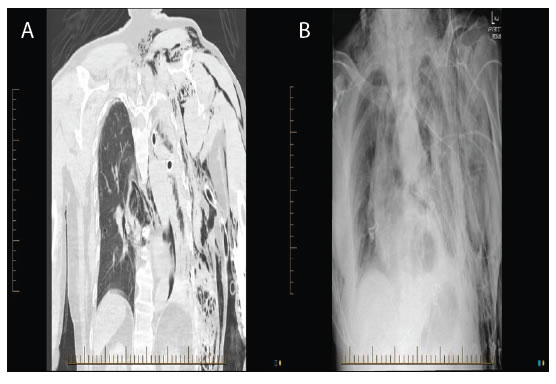

Figure 1. Menstrual Restrictions construct the power

Figure 2. Menstrual Restrictions and its Impact on Empowerment

Figure 3. Menstrual Restriction and its impact on empowerment

Menstruating girls and women lose their sense of and motivation to control, skills for decision making and problem solving and critical awareness on socio-political environment as impact of psychological disempowerment. In this vein [11] described as constructs; interpersonal, interactional and behavioural component under the homological framework of psychological empowerment. Additionally, limiting or exclusion due to menstruation also affects women legal rights and freedom of women in public sphere.

The impact of education and health are overlapping here. Girls and women have low self-esteem, feeling of inferior, humiliation, hopelessness, powerlessness because of compromising the needs and rights related with food, water, shelter, environment, education, health and eventually dignity [22]. Dignity is such a right which includes all rights and offers right to all aspects of life of girl, women and any individual. Poor education, poor health is the status of poor human right and status of disempowerment.

Conclusion

Girls and women lose the confidence for living as a dignified human kind due to imposing of varieties of restrictions during menstruation. They used to with this too. In this connection, stakeholders need to carryout the holistic approach to get rid off from the negative impact on the lives of girls and women due to restrictions due to menstruation. Because the above-mentioned figures showed that the impact is not in a single line (liner way). It has multiple connections and overlapping each other’s. The dignity and empowerment during menstruation could bring through combined efforts of different elements such as health, education, water, sanitation.

Limitations

This study confined with qualitative approach and employed in Chandanath Municipality, Jumla.

Conflict of Interest

No any conflict of interest. This has done for the sake of fulfilment of academic requirement as building block of my activism around menstruation.

Funding

There is no any funding for supporting of this study.

References

- Kamaljit (2019) Empowerment and Contemporary Social Normativity. British Journal of Social Work 45: 1855–1870.

- UNICEF (2015). Wins for Girls. Retrieved from UNICEF. [Crossref]

- Khanna A, Goyal RS, Bhawsar R (2005) Menstrual Practices and Reproductive Problems: A Study of Adolescent Girls in Rajasthan. Journal of Health Management.

- Kadariya S, Aro AR (2015) Chhaupadi practice in Nepal – analysis of ethical aspects. Unit for Health Promotion Research, University of Southern Denmark, Esbjerg, Denmark.

- Thakre SB, Thakre SS, Reddy M, Rathi N, Pathak K and Ughade S (2011) Menstrual Hygiene: Knowledge and Practice among Adolescent School Girls of Saoner, Nagpur District. Journal of Clinical and Diagnostic Research

- Bora A (2017) Stigmatized Menstruation and Gst: A Critical Appraisal. School of Law, Christ University, Bangalore.

- Walton S (2013) Does Menstruation Hinder Women’s Empowerment? Working Toward Social

- Reinharz S (1992) Feminist Methods in Sociology. Oxford University Press.

- Action Works Nepal (2013) Chhaupadi among Adolecent Girls in Jumla and Kalikot.

- Elana D Buch and Karen M. Staller (2007) The Feminist Practice of Ethnography. Sage.

- Kathy C (2012) Constructing Grounded Theory

- Zimmerman MA (2012) Psychological, organizational and community level Analysis. University of Michigan.

- Carr ES (2003) Rethinking Empowerment Theory Using a Feminist Lens: The Importance of Process. Affilia 18: 8–20.

- Lukes S (2004) Power: A radical view (2nd ed). Hound mills, Basingstoke, Hampshire : New York: Palgrave Macmillan.

- Cattaneo LB, Chapman AR (2010) The process of empowerment: A model for use in research and practice. American Psychologist 65: 646–659.

- Zimmerman MA (1995) Psychological Empowerment: Issues and Illustrations 1. American Journal of Community Psychology 23(5).

- Paudel R., Adhikari M, Wenzel T and Maria KP (2019) The Construction of Power in Nepal: Menstrual Restriction and Rape. ARCH Women Health Care Volume 2: 1–7.

- Carr E S (2003) Rethinking Empowerment Theory Using a Feminist Lens: The Importance of Process. Affilia 18: 8–20.

- Solomon BB (1976) Black Empowerment: Social Work in Oppress ed Communities.

- Garg S, Sharma N and Sahay R (2001) Socio-cultural aspects of menstruation in an urban slum in Delhi, India. Taylor &Francis Group.

- Johnston-Robledo I and Chrisler JC (2013) The Menstrual Mark: Menstruation as Social Stigma. Sex Roles 68: 9–18.

- Rembeck G, Möller M and Gunnarsson R (2006) Attitudes and feelings towards menstruation and womanhood in girls at menarche. Acta Paediatrica 95: 707– 714.