DOI: 10.31038/PEP.2020112

Abstract

Context: Health service providers increasingly screen for health-related social risks and refer patients to social care resources. However, a national, individual-level social health surveillance system that supports this linkage between medical and social care does not yet exist. Public health surveillance provides the model for a national, individual-level social health surveillance system specifically designed to support the integration of social and medical care in order to address upstream contributors of illness.

Objective: To systematically review the literature describing existing social health surveillance systems in the United States that screen, address, collect, store, analyze, and disseminate social needs or risk factors for the purposes of developing activities that impact population health.

Design: Articles from PubMed, MEDLINE, and Social Intervention Research and Evaluation Network (SIREN) Evidence Library between January 1, 2008 and December 31, 2018 were searched using the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Review and Meta-analysis Protocols (PRISMA-P).

Eligibility Criteria: Epidemiological surveillance was used as a model to identify social health surveillance systems, defined as the ongoing collection, storage, analysis, and classification of social determinants of health data essential to the planning, implementation, and evaluation of interventions intended to improve health outcomes.

Study Selection: Thirteen articles met the inclusion and exclusion criteria, representing 9 different social health surveillance systems serving mostly low-income populations in 20 states.

Main Outcome Measures: The social health surveillance systems integrate social and medical care to improve health outcomes.

Results: All 9 social health surveillance systems continuously collected individual-level social determinants of health data from at least 2 of the 17 domains recommended by the Institute of Medicine. A wide variation existed in the social health surveillance systems capabilities.

Discussion: To build a 21st century social health surveillance system, public health leaders should expand epidemiological surveillance in collaboration with the medical and social care systems to include individual level social determinants of health.

Keywords

social determinants of health, social care, social health surveillance

Introduction

The upstream social factors that contribute to illness can overwhelm clinicians practicing in an ill-equipped healthcare system [1, 2]. Innovations increasingly link social care needs, such as food, housing support, and financial assistance, to the healthcare system, [3] which includes physical, mental, dental, and pharmaceutical care. However, a national, individual-level social health surveillance system that supports medical and social care integration does not yet exist. Borrowed from the public health domain, a social health surveillance system can be defined as the ongoing collection, storage, analysis, and classification of social determinants of health (SDH) data essential to the planning, implementation, and evaluation of social care need interventions that are designed to improve health outcomes.

A consensus committee report of the National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine (NASEM Committee) appealed for increased attention to individuals’ social context by the United States (U.S.) health service delivery system [1]. The Committee recommended utilizing validated screening instruments, standardizing social risk terms, and facilitating interoperable data systems that enable advanced analytic approaches to population health. However, no best practice exists for social health surveillance systems [4, 5].

In contrast, U.S. epidemiological surveillance systems are sophisticated, robust, and long-standing [6].Public health surveillance is the continuous collection of health information for the evaluation, analysis, and translation of data into knowledge about the health of communities that can enable action [7]. Surveillance of risk factors for non-communicable diseases, such as cancer, heart disease, stroke, diabetes, asthma, and poisonings, has informed public health interventions for over 30 years [1, 6, 8].Public health surveillance systems may be the model for the development of national social health surveillance system. However, existing social health surveillance systems have not yet been described.

A social health surveillance system should consist of three key components: 1) the ability to continuously and systematically collect, store, analyze, address, and classify patient-level social needs and social risk data, 2) the capacity to plan, implement, and evaluate programs or activities that are 3) specifically designed for the purposes to integrate social and medical care to improve health outcomes. That is, effective social health surveillance systems have the capability to link SDH information to health outcomes in order to address upstream contributors of illness–the “causes of the causes” of poor health [9].

Various systematic reviews analyzed other elements of social and medical care integration efforts, including the many different screening instruments available to assess SDH, [10, 11] social care intervention activities in the health care sector, [12-17] types of SDH collected, [18] and the adequacy of electronic health records systems to support social health data collection [19-21]. The purpose of the present study is to gather and synthesize the best available published evidence on current social health surveillance systems.

Methods

This systematic review was guided by the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Review and Meta-analysis Protocols (PRISMA-P) guidelines [22]. The research team conducted a search for articles from the following databases: PubMed, MEDLINE, and Social Intervention Research and Evaluation Network (SIREN) Evidence Library. SIREN Evidence Library is an archive of literature run by Center for Health and Community at University of California, San Francisco. PubMed Medical Subject Headings (MeSH) search headings included social determinants of health, mass screening, and population surveillance. Keywords in MEDLINE included “social prescribing,” “social and medical care integration,” “social care needs surveillance,” “social determinants of health surveillance,” “social determinants of health screening,” “socioeconomic status surveillance,” “socioeconomic status screening,” “population surveillance,” “social needs surveillance,” “mass screening,” “social needs screening,” “screening and referral” and combinations of surveillance, screening, and social determinants. In the SIREN Evidence Library, the authors identified articles categorized as “screening research.” The authors also searched citations of articles that met the inclusion criteria.

Table 1. Keywords for database search

|

MEDLINE Keywords |

|

Social prescribing |

|

Social and medical care integration |

|

Social care needs surveillance |

|

Social determinants of health surveillance |

|

Social determinants of health screening |

|

Socioeconomic status surveillance |

|

Socioeconomic status screening |

|

Population surveillance |

|

Social needs surveillance |

|

Mass screening |

|

Social needs screening |

|

Screening and referral |

The search strategy was limited to articles regarding social health surveillance programs based in the U.S. The title and abstract of each article were evaluated for inclusion according to the definition of a social health surveillance system: the ongoing collection, storage, analysis, and classification of SDH data essential to planning, implementation, and evaluation of interventions designed to integrate social and medical care for improve population health.

Two authors (Zachary Pruitt and Ibrahim Akorede) independently reviewed each article included to determine if the study met all inclusion criteria. Search results were imported into EndNote Online. In cases where there was disagreement between authors about study inclusion, consensus was achieved by review of a third researcher (NnadozieEmechebe).

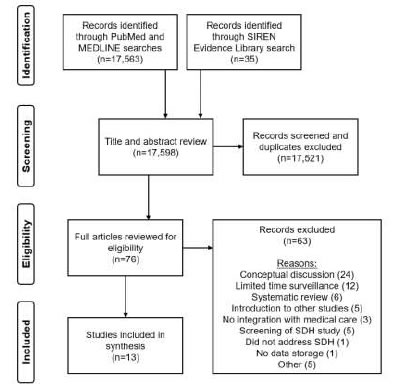

The search yielded 17,598 unique records published in English between January 1, 2008 and December 31, 2018. Of these titles and abstracts, 76 full articles reviewed for eligibility criteria. A final list of 76 studies were selected for inclusion criteria (Table 2). The full review according to the eligibility text review eliminated 63 articles that lacked the required information regarding social health surveillance systems. The final sample contained 13 unique studies that met all inclusion criteria. Articles were excluded for a variety of reasons, as noted in Figure 1 that depicts the PRISMA-P diagram for this study.

Figure 1. Flowchart of studies included in the Social Health Surveillance Systematic Review

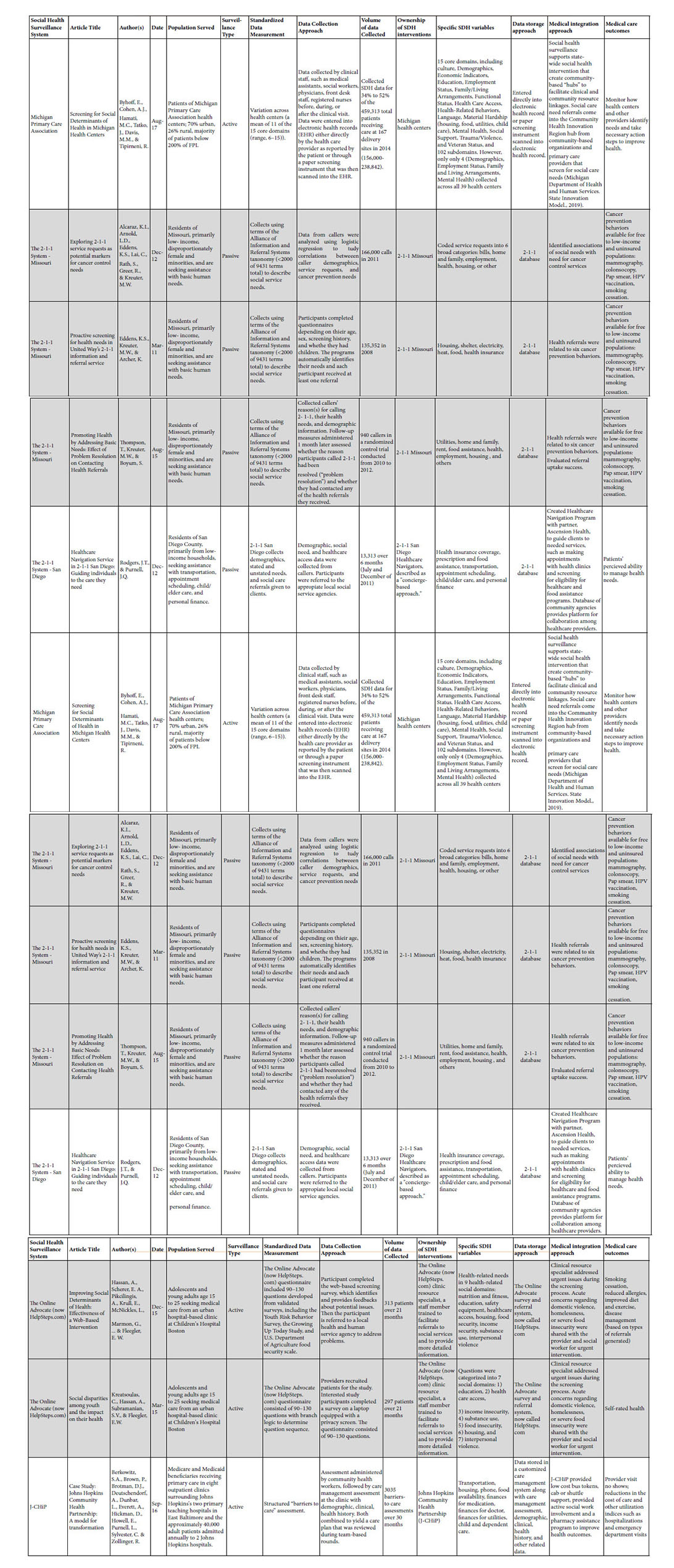

Table 2. Social Health Surveillance Systems.

Results

Thirteen articles were included in this review, representing 9 different social health surveillance systems. Among articles reviewed in detail, 63 were excluded. Excluded articles only discussed general concepts related to addressing SDH in medical care (24), did not collect SDH data continuously (12), related to systematic reviews of other social and medical care integration topics (6), introduced other studies (5), addressed only the SDH screening mechanisms, (5) included no description of SDH integration with medical care (3), did not address SDH (1), did not discuss how SDH data was stored (1), or other reasons (5).

Existing Social Health Surveillance Systems

The 9 identified social health surveillance systems mostly served low-income populations in 20 states. Each used different screening instruments with collection at varying levels of volume and intensity. A variety of approaches for integrating social care and medical care were present.

Michigan Primary Care Association

The 240 primary care community health clinics (CHCs) of Michigan Primary Care Association conducted SDH screenings.5 SDH data were collected by clinical staff, such as medical assistants, social workers, physicians, front desk staff, and registered nurses. Data were entered into electronic medical record system (EMR) either directly by the health care provider as reported by the patient or through a paper screening instrument that was then scanned into the EMR. The SDH data were used to support state-wide social health intervention programs, such as Michigan’s State Innovation Model (SIM) [23] and Michigan Pathways to Better Health, [24] that were coordinated by community-based “hubs” to facilitate clinical and community resource linkages.

The 2-1-1 System

The 2-1-1 system is a collection of call centers that connects individuals with basic social care needs to social services organizations in their communities [25]. While over 200 programs are administered by different entities across the U.S., only two separate 2-1-1 organizations met the inclusion criteria for social health surveillance systems: Missouri [26-28] and San Diego County [29]. These 2-1-1 systems adapted existing social care referral programs to create linkages between social care organizations and health care systems.

In Missouri, after 2-1-1 call center representatives provided social care referrals, individuals were asked to complete cancer screening. Based on answers to these questions, a computer program identified needs for cancer control services and generated referrals to local cancer prevention services, such as mammography and smoking cessation programs. The Missouri 2-1-1cancer prevention program then followed-up with patients to assess cancer service utilization rates.

The San Diego 2-1-1 system leveraged their already high-functioning social care referral call center to create healthcare navigation programs to help individuals identify social care needs, make and keep needed medical appointments, and removed the barriers to address health-related needs in the community [29]. Another department helped callers obtain access to health-related public assistance programs.

OCHIN

OCHIN centrally manages an Epic-based EMR system used by more than 440 primary care community health centers (CHCs) [30]. Three CHCs in Washington and Oregon were used as pilot sites to collect, review, and integrate social needs with medical care through referrals. SDH data were collected through three different approaches: (1) SDH modules in the EHR available to front desk staff, clinicians, and community health workers, (2) paper surveys entered by patient then coded into EMR system by staff, and (3) a patient portal questionnaire completed by patient before the visit. Based on identified social care needs, community health workers provided social service referrals. The EMR also enabled social care referral summaries to be accessed during subsequent clinical encounters to support follow-up by the care team [30]. In June 2016, the social health surveillance tools were made available to all OCHIN member clinics (97 sites in 18 states), where preliminary evaluations show variation in screening adoption and data collection and medical care integration workflows [31].

Health Leads

Health Leads staffed help desks with college students at urban medical clinics across the U.S [20, 32]. In the Health Leads model, patients’ parents completed a SDH screening survey, providers reviewed screening results and referred patients to Health Leads help desks, and the student “Advocates” utilized the Health Leads database to refer patients and their families to community-based social services. The social needs were captured within the EMR systems and Health Leads’s database, which enabled evaluation of social care interventions on individual or population health.

WellCare’s Social Service Referral Service

Similar to the 2-1-1 system, the non-clinical call center staff of WellCare Health Plan’s social service hotline identified social care needs and referred their Medicare and Medicaid members to social care organizations [33]. The screening results shared with WellCare’s case managers who provided direct assistance to individuals with social and medical care needs [34].

WellRx

Three family medicine clinics in Albuquerque, New Mexico piloted a program in collaboration with University of New Mexico and Medicaid managed care plans to collect SDH data through a paper-based survey instrument [35]. For over 3,000 patients over a 3-month period (later expanded to all patients at 9 primary care locations [31]), clinics stored SDH data in the EMR for access by community health workers who sought to improved patient engagement and create better informed primary care clinicians and staff. The program was also utilized for diabetes control quality improvement project.

The Online Advocate (now HelpSteps.com)

For adolescents and young adults seeking medical care from an urban hospital-based clinic at Children’s Hospital Boston, the Online Advocate (now HelpSteps.com) conducted a web-based screening survey for social risk, such as food insecurity, healthcare access, and interpersonal violence. Based upon identified social care needs, the system—termed “social epidemiology” by the authors—provided referrals to local social service agency to address the identified social risks [36]. The online assessment system acted as a complement to clinical visits in order to improve attention to patients’ social needs [37].

Johns Hopkins Community Health Partnership (J-CHiP)

In 8 primary care outpatient clinics in East Baltimore, Maryland, the Johns Hopkins Community Health Partnership (J-CHiP) community health workers collected SDH data that were combined with care management assessment, demographic, clinical, health history, and other related data to be reviewed during the clinical encounter [38]. J-CHiP interventions sought to reduce provider visit no shows, cost of care, and other utilization indices, such as hospitalizations and emergency department visits.

Social Health Surveillance Attributes

All 9 social health surveillance systems included in this systematic review collected individual-level SDH data continuously. Each of the social health surveillance systems screened for at least 2 of 17 SDH domains recommended by the Institute of Medicine (IOM), but none screened for all IOM-recommended SDH domains.18 None of the 9 identified social health system utilized the same data collection approach, except the 2-1-1 systems in Missouri and San Diego. OCHIN utilized the Protocol for Responding to and Assessing Patients’ Assets, Risks, and Experiences (PRAPARE) assessment tool developed by the National Association of Community Health Centers that integrates with EMR systems, although each pilot site implemented screenings differently [39].

The intensity of public health surveillance systems can be classified as active or passive [40].Correspondingly, active social health surveillance utilizes screening tools to directly identify patient social needs at medical care facilities. A passive social health surveillance system relies on social needs identified and reported by individuals or their caregivers. Among the 9 social health surveillance systems identified in this review, 6 were active (Michigan Primary Care Association, OCHIN, Health Leads, WellRx, The Online Advocate, and J-CHiP) and 3 were passive (WellCare, Missouri 2-1-1, and San Diego 2-1-1).

The passive social health surveillance systems (WellCare and the 2-1-1 Systems) use custom technology platforms to track social services referrals and to store SDH data. The Michigan Primary Care Association, OCHIN, and WellRx stored SDH data in their respective EMR systems. Health Leads in Baltimore stored SDH data both in a database of social service referrals and in the EMR social history. J-CHiP SDH data are stored in a customized care management system. The Online Advocate (HelpSteps.com) survey and referral system stored the SDH data for analysis.

A fundamental component of social health surveillance systems is the ability to analyze these data. Although all 9 social health surveillance systems screened for social care needs for the purposes of integrating social care with medical care practices, our review shows a wide variation in capabilities to plan, implement, evaluate interventions designed to integrate social and medical care. For example, at the Michigan Primary Care Association, the lack of standard screening practices across de-centralized referral “hubs” limited the ability to plan, implement, and evaluate interventions to those SDH domains reliably collected, such as homelessness [5].

Two social health surveillance systems effectively analyzed the relationship between social care interventions and health outcomes and published those results in peer-reviewed literature. The Missouri 2-1-1 System cancer control program successfully planned, implemented, and evaluated their cancer control referral uptake rates [27].The WellCare program published detailed evaluation of the social and medical care integration efforts, including the association of social risk factors to inpatient readmissions41 and the relationship of social care utilization to overall health care spending [33].

For other social health surveillance systems, although capacity for evaluation exists, the results of the influence of social health interventions on medical care outcomes are less clear. For example, Health Leads papers stated that the program could evaluate how resource interventions can impact “individual or population health over time” [20] and “promote greater health equity,” [32] but these results were not yet published. OCHIN [30] and J-CHiP [38] also described capabilities to evaluate the impact of social care interventions on health outcomes, but the results were not published. Other social health surveillance systems relied on health measures collected as a part of the social health surveillance system, such as patients’ perceived ability to manage health needs (San Diego 2-1-1 [29]), diabetes control (WellRx [35]) and self-rated health (The Online Advocate/ HelpSteps.com [37, 42]).

Discussion

Public health surveillance provides the model for a national, individual-level social health surveillance system specifically designed to support the integration of social and medical care. The public health system obtains large quantities of data from widely-recognized data sources, such as reportable diseases, vital statistics, registries, surveys, and from administrative sources, such ashospital and emergency department discharges data, insurance billing claims, laboratory test results, and poison control hotline data [8, 43]. Critically important, public health transforms this data into actionable information on the health needs and risks of the community served in order to create interventions designed to improve public health [44].The public health system currently conducts national surveys that include SDH, such as Behavioral Risk Factor Surveillance System (BRFSS), to develop community-level representations of social health risk, but community-level data may not enough detail to develop effective interventions seeking to integrate medical and social care systems [45]. When it comes to creating an effective social health surveillance, the tenets of epidemiological surveillance should be upheld but require adaptation.

The NASEM Committee recommended 5 complementary activities needed to strengthen social care integration: awareness, assistance, adjustment, alignment, and advocacy [1]. The 9 existing social health surveillance systems described in this systematic review support these activities directly. First, all 9 social health surveillance systems conduct awareness activities by identifying the social risks. However, the variability in how these SDH data are collected present a challenge to developing a fully-realized national surveillance system. A more effective social health surveillance system would incorporate national data standards for EMRs and other data systems and utilize and interoperable technology infrastructure for sharing between and among organizations [1,18,21].

According to the NASEM Committee, assistance entails connecting individuals to community-based social service assets. Without assistance, the effort to “medicalize” social care needs into medical care rather than investing in upstream community interventions may add to the costs with negligible impacts on health outcomes [46]. Such “collection without connection” negates the benefits of screening for social risk factors and may cause unintended consequences, such as undue burden on providers or distress to patients [47]. All 9 social health surveillance systems provided assistance activities through similar processes – identify a social care need, make social care referral, and follow-up to assess the health-related outcomes. Some organizations assist individuals through a “concierge-based approach” where “navigators” (San Diego 2-1-1 [29]) or “advocates” (Health Leads [20, 32]) assist members with social care needs throughout a defined process.

All social health systems identified in this review altered their clinical approaches to accommodate social health issues, described as adjustment activities by the NASEM Committee [1]. For example, WellCare Health Plans utilized SDH data in their health plan case management processes, [33] the Missouri 2-1-1 System asked additional cancer prevention questions, [26-28] and health care providers at clinics with Health Leads help desks refer patients to students advocates for detailed social service guidance [20, 32].

Finally, according to the NASEM Committee, alignment and advocacy relate to investments and support of the social care services by health systems in their communities, and this systematic review found evidence of alignment and advocacy activities [1].For example, evidence from the WellCare Health Plans SDH data showed that utilization of social services was associated with greater reduction in healthcare costs reinforcing the organization’s commitment to align social care with medical care by issuing microgrants to community-based organizations to support the exchange of additional social care utilization data [33, 48]. Advocacy was demonstrated by the collaboration between the New Mexico Medicaid agency, health plans, and federally qualified health centers to expand the scope of the effort of the WellRx pilot program to address SDH [35].

In public health, active surveillance involves the health department directly conducting research or reaching out to providers and laboratories for data collection, and passive surveillance relies on reporting by clinicians. These public health surveillance components contain social health surveillance analogs. Active social health surveillance utilizes screening tools to directly identify patient social needs at medical care facilities. A passive social health surveillance relies on social needs identified and reported by individuals or their caregivers.

Six of the identified social health surveillance systems use an active approach, which has the advantage of proximate integration of between identification of patients’ priority social care needs and relevant medical issues.4 However, there are drawbacks to active social health surveillance, including the costs to clinicians who may lack the time to address social health risks [1, 49]. In addition, active surveillance may identify social risks but lack the time to obtain social care services. Finally, patients may not be receptive to social needs screening or have general privacy and stigma concerns related to non-clinical social health surveillance systems [50, 52].

A vast majority of public health surveillance systems are passive [53]. Only 3 social health surveillance systems were passive [34, 54]. Social service referral experts free-up clinical resources to conduct their specialized roles [37]. However, privacy and security concerns may be associated with non-clinical sites collecting SDH which may require an increased capacity to comply with privacy and security standards related to the sharing of protected health information [1].

Limitations

Though the search was exhaustive, some social health surveillance systems may not be included. The review includes published studies only so there may be other qualified social health surveillance systems. For example, Kaiser Permanente in California launched Thrive Local by partnering with social care referral system platform called Unite Us to connect social and medical care for patients, but peer-reviewed literature on the program was not yet available [55]. Finally, some social health surveillance systems may have been excluded because some defining aspect, such as identification of health outcomes, may be present in the system but not fully explained the published literature.

In conclusion, the social health surveillance system of the 21st century will utilize a steady stream of SDH data to permit benchmarking, goal setting, coordinated interventions, and description of results of integrating social care and medical care [43]. The 9 social health surveillance systems described in this systematic review fulfill this vision, but further work is needed.

Public Health 3.0 seeks to build on extraordinary public health successes of the 19th and 20th centuries to work across sectors to address SDH to improve population health [56]. Using this new perspective, public health leaders should expand epidemiological surveillance systems into a robust, nation-wide social health surveillance system through a multi-disciplinary collaboration with medicine, public health, social work, and others. To build a 21st century social health surveillance system beyond the programs identified in this review, policymakers should marshal the necessary resources [1, 8]. Without a social health surveillance system that supports the development of effective interventions that address SDH, the downstream clinical encounter will continue to be overwhelmed [1, 9].

Implications for Policy and Practice

- A social health surveillance system can be defined as the ongoing collection, storage, analysis, and classification of social determinants of health data essential to the planning, implementation, and evaluation of social care need interventions.

- Each of 9 identified social health surveillance systems implemented different approaches to continuous SDH data collection, but all used the information to integrate social and medical care.

- The social health surveillance systems were specifically designed for the purposes of addressing social care needs in order to improve health outcomes, such as reducing inpatient readmissions or emergency department visits.

Public health leaders should expand the epidemiological surveillance systems into a robust, nation-wide social health surveillance system through a multi-disciplinary collaboration with medicine, public health, social work, and others.

References

- National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine. (2019) Integrating Social care needs into the Delivery of Health Care: Moving Upstream to Improve the Nation’s Health. Washington, D.C. The National Academies Press.

- Bradley EH, Taylor LA (2013) The American health care paradox: why spending more is getting us less. New York, NY: Public Affairs.

- Institute of Medicine. Primary Care and Public Health: Exploring Integration to Improve Population Health. Washington, D.C.2012.

- Gottlieb LM, Francis DE, Beck AF (2018) Uses and misuses of patient-and neighborhood-level social determinants of health data. The Permanente journal 22: 18-78. [crossref]

- Byhoff E, Cohen AJ, Hamati MC, Tatko J, Davis MM, et al. (2017) Screening for Social Determinants of Health in Michigan Health Centers. Journal of the American Board of Family Medicine 30: 418-427.[crossref]

- Thacker SB, Berkelman RL (1988) Public Health Surveillance in the United States. Epidemiologic Reviews 10: 164-190.[crossref]

- Thacker SB, Berkelman RL (1988) PUBLIC-HEALTH SURVEILLANCE IN THE UNITED-STATES. Epidemiologic Reviews10:164-190.[crossref]

- Smith PF, Hadler JL, Stanbury M, Rolfs RT, Hopkins RS, (2013) Grp CSS. “Blueprint Version 2.0”: Updating Public Health Surveillance for the 21st Century. Journal of Public Health Management and Practice 19:231-239.[crossref]

- Campostrini S (2013) Surveillance for NCDs and health promotion: an issue of theory and method. In: McQueen DV, ed. Global handbook on noncommunicable diseases and health promotion. New York, NY: Springer51-70.

- Berman RS, Patel MR, Belamarich PF, Gross RS (2018) Screening for Poverty and Poverty-Related Social Determinants of Health. Pediatrics in Review 39:235-246.[crossref]

- Morone J (2017)An Integrative Review of Social Determinants of Health Assessment and Screening Tools Used in Pediatrics. Journal of Pediatric Nursing-Nursing Care of Children & Families37:22-28.[crossref]

- Cartier Y, Pantell M, De Marchis E, Gottlieb L (2019) National surveys gauging the prevalence of social care-related activities in the health care sector.

- Lundeen EA, Siegel KR, Calhoun H,Kim SA, Garcia SP, et al. (2017) Clinical-Community Partnerships to Identify Patients With Food Insecurity and Address Food Needs. Preventing Chronic Disease 14: 113.

- Cartier Y, Pantell M, De Marchis E, Gottlieb L (2019) National surveys gauging the prevalence of social care-related activities in the health care sector.

- Gottlieb LM, Wing H, Adler NE (2017) A Systematic Review of Interventions on Patients’ Social and Economic Needs. American journal of preventive medicine 53: 719-729. [crossref]

- Alderwick HAJ, Gottlieb LM, Fichtenberg CM, Adler NE (2018) Social Prescribing in the U.S. and England: Emerging Interventions to Address Patients’ Social Needs. American journal of preventive medicine 54: 715-718. [crossref]

- Gottlieb LM, Garcia K, Wing H, Manchanda R (2016) Clinical Interventions Addressing Nonmedical Health Determinants in Medicaid Managed Care. American Journal of Managed Care 22: 370-376.[crossref]

- Institute of Medicine (2014) Capturing Social and Behavioral Domains and Measures in Electronic Health Records: Phase 2. In: Washington, DC: The National Academies Press.

- Navathe AS, Zhong F, Lei VJ,Chang FY, Sordo M, et al. (2017) Hospital Readmission and Social Risk Factors Identified from Physician Notes. Health services research 53: 1110-1136. [crossref]

- Gottlieb LM, Tirozzi KJ, Manchanda R, Burns AR, Sandel MT (2015) Moving Electronic Medical Records Upstream Incorporating Social Determinants of Health. American Journal of Preventive Medicine 48:215-218.[crossref]

- Cantor MN, Thorpe L (2018) Integrating Data On Social Determinants Of Health Into Electronic Health Records. Health Affairs 37:585-590.[crossref]

- Shamseer L (2015) Preferred reporting items for systematic review and meta-analysis protocols (PRISMA-P) 2015: elaboration and explanation. Bmj-British Medical Journal350.7647.

- Michigan Department of Health and Human Services. State Innovation Model. Published 2019. Accessed.

- Moving Healthcare Upstream. Michigan Pathways to Better Health. Published 2019. Accessed November 20, 2019.

- Hall KL, Stipelman BA, Eddens KS,Kreuter MW, Bame SI et al. (2012) Advancing Collaborative Research with 2-1-1 to Reduce Health Disparities Challenges, Opportunities, and Recommendations. American Journal of Preventive Medicine 43: 518-528.[crossref]

- Alcaraz KI, Arnold LD, Eddens KS, Lai C, Rath S et al. (2012) Exploring 2-1-1 Service Requests As Potential Markers for Cancer Control Needs. American Journal of Preventive Medicine 43: 469-474.[crossref]

- Eddens KS, Kreuter MW, Archer K (2011) Proactive Screening for Health Needs in United Way’s 2-1-1 Information and Referral Service. Journal of Social Service Research 37:113-123.

- Thompson T, Kreuter MW, Boyum S (2016) Promoting health by addressing basic needs: effect of problem resolution on contacting health referrals. Health Education & Behavior 43:201-207.[crossref]

- Rodgers JT, Purnell JQ (2012) Healthcare Navigation Service in 2-1-1 San Diego Guiding Individuals to the Care They Need. American Journal of Preventive Medicine 43: 450-456.[crossref]

- Gold R, Cottrell E, Bunce A,Middendorf M, Hollombe C et al. (2017) Developing Electronic Health Record (EHR) Strategies Related to Health Center Patients’ Social Determinants of Health. Journal of the American Board of Family Medicine 30:428-447. [crossref]

- LaForge K, Gold R, Cottrell E,Bunce AE, Proser M et al. (2018) How 6 Organizations Developed Tools and Processes for Social Determinants of Health Screening in Primary Care An Overview. Journal of Ambulatory Care Management 41:2-14.[crossref]

- Garg A, Marino M, Vikani AR, Solomon BS. (2012) Addressing Families’ Unmet Social Needs Within Pediatric Primary Care: The Health Leads Model. Clinical Pediatrics 51:1191-1193.[crossref]

- Pruitt Z, Emechebe N, Quast T, Taylor P, Bryant KB (2018) Expenditure Reductions Associated with a Social Service Referral Program. Population health management 21: 469-476. [crossref]

- Pruitt Z, Taylor PL, Bryant KM (2018)A managed care organization’s call center-based social support role. American journal of accountable care 5: 16-22.

- Page-Reeves J, Kaufman W, Bleecker M,Norris J, McCalmont K et al. (2016) Addressing Social Determinants of Health in a Clinic Setting: The WellRx Pilot in Albuquerque, New Mexico. Journal of the American Board of Family Medicine 29:414-418.[crossref]

- Hassan A, Scherer EA, Pikcilingis A,Krull E, McNickles L, et al. (2015) Improving Social Determinants of Health Effectiveness of a Web-Based Intervention. American Journal of Preventive Medicine 49:822-831.[crossref]

- Kreatsoulas C, Hassan A, Subramanian SV, Fleegler EW (2015) Social disparities among youth and the impact on their health. Adolescent Health Medicine and Therapeutics6:37-45.[crossref]

- Berkowitz SA, Brown P, Brotman DJ,Deutschendorf A, Dunbar Let al. (2016) Case Study: Johns Hopkins Community Health Partnership: A model for transformation. Healthcare (Amsterdam, Netherlands) 4:264-270.[crossref]

- National Association of Community Health Centers. PRAPARE Implementation and Action Toolkit. Published 2019. Accessed Deccember 30, 2019.

- Lee LM, Teutsch SM, Thacker SB, St. Louis ME (2010) Principles and Practice of Public Health Surveillance. 3rd ed: Oxford University Press.

- Emechebe N, Lyons PT, Amoda O, Pruitt Z (2019) Passive social health surveillance and inpatient readmissions. The American journal of managed care 25: 388-395. [crossref]

- Hassan A, Blood EA, Pikcilingis A, Krull EG, McNickles L et al. (2013) Youths’ Health-Related Social Problems: Concerns Often Overlooked During the Medical Visit. Journal of Adolescent Health 53: 265-271. [crossref]

- Campostrini S, McQueen VD, Abel T (2011) Social determinants and surveillance in the new Millennium. International Journal of Public Health 56: 357-358. [crossref]

- Institute of Medicine. Primary Care and Public Health: Exploring I ntegration to Improve Population Health. Washington, D.C.2012. [crossref]

- Kasthurirathne SN, Vest JR, Menachemi N, Halverson PK, Grannis SJ (2018) Assessing the capacity of social determinants of health data to augment predictive models identifying patients in need of wraparound social services. Journal of the American Medical Informatics Association 25: 47-53. [crossref]

- Health Affairs Blog. When Talking About Social Determinants, Precision Matters.. Published 2019. Accessed October 29, 2019.

- Garg A, Boynton-Jarrett R, Dworkin PH (2016) Avoiding the Unintended Consequences of Screening for Social Determinants of Health. Jama-Journal of the American Medical Association 316: 813-814. [crossref]

- The Commonwealth Fund. WellCare’sCommUnity Impact Model. Published 2018. Accessed May 1, 2019.

- Tong ST, Liaw WR, Kashiri PL, Pecsok J, Rozman J et al. (2018) Clinician Experiences with Screening for Social Needs in Primary Care. Journal of the American Board of Family Medicine 31: 351-363. [crossref]

- Jaganath D, Johnson K, Tschudy MM, Topel K, Stackhouse B et al. (2018) Desirability of Clinic-Based Financial Services in Urban Pediatric Primary Care. Journal of Pediatrics 202: 285-290. [crossref]

- Adams E, Hargunani D, Hoffmann L, Blaschke G, Helm J, et al. (2017) Screening for Food Insecurity in Pediatric Primary Care: A Clinic’s Positive Implementation Experiences. Journal of Health Care for the Poor and Underserved 28: 24-29. [crossref]

- Knowles M, Khan S, Palakshappa D,Cahill R, Kruger E et al. (2018) Successes, Challenges, and Considerations for Integrating Referral into Food Insecurity Screening in Pediatric Settings. Journal of Health Care for the Poor and Underserved 29: 181-191. [crossref]

- Institute of (2011) Medicine Committee on a National Surveillance System for Cardiovascular and Select Chronic Diseases Existing Surveillance Data Sources and Systems. In: A Nationwide Framework for Surveillance of Cardiovascular and Chronic Lung Diseases. Washington, DC: National Academies Press.

- Thompson T, Roux AM, Kohl PL, Boyum S, Kreuter MW (2018) What would help low-income families?: Results from a North American survey of 2-1-1 helpline professionals. Journal of child health care. [crossref]

- Kaiser Permanente. Social health network to address needs on a broad scale. Published 2019. Accessed May 31, 2019.

- DeSalvo KB, Wang YC, Harris A, Auerbach J, Koo D, et al. (2017) Public Health 3.0: A Call to Action for Public Health to Meet the Challenges of the 21st Century. Preventing Chronic Disease 14.