DOI: 10.31038/IJOT.2020312

Abstract

Background: Bier block, or intravenous regional block (IVRB), and Conscious Sedation (CS) can be used for pediatric forearm fracture reductions. This study compares the two.

Questions/Purposes: Of the two options (IVRB vs CS) of anesthesia for pediatric fracture reduction, is one safer and more cost efficient?

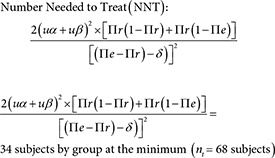

Patients and Methods: Arkansas Children’s Hospital charts were reviewed for pediatric forearm fractures treated in the ED between 2005 and 2014. Patient age, sex, fracture type, mechanism of injury, need for further reduction, initial complications, long-term complications, number of follow-up visits, need for further operative reduction, and total weeks of care were gathered. Patient from ages 4–7 were included in the study due to the tendency of using CS for younger patients. ED room costs were compared between 18 IVRB patients and 19 CS patients.

Results: Total length of care for IVRB was 5.9 weeks versus 5.6 for CS with 2.8 follow-up appointments for IVRB versus 2.7 for CS. IVRB cost $423 less than CS. There were no complications in either group.

Conclusion-IVRB: Is safe and cost effective method for pediatric forearm fracture reduction compared to CS.

Clinical Relevance: Eliminating the need for sedation and stream-lining fracture treatment in the pediatric ED is both safe and efficient when using IVRB. Patients are not required to be NPO and do not require prolonged recovery in the ED.

Introduction

Developed in 1908, the Bier block technique, also known as Intravenous Regional Block (IVRB), utilizes the retrograde intravenous flow in an extremity with a tourniquet in place proximal to the fracture to deliver local anesthetic to the extremity for regional anesthesia. Our institution is an academic children’s medical center where the Bier block is routinely used as the sole anesthesia for closed reduction of pediatric forearm fractures. This method of anesthesia has a long historical record of safety and efficacy, and does not require the patient to have an empty stomach as is required for conscious sedation [1–4, 5]. Conscious sedation is also well-described and widely used in managing pediatric forearm fractures requiring a closed reduction in the emergency room [3, 4] The aim of this study is to compare the short- and long-term clinical and radiographic outcomes of Bier block anesthesia and conscious sedation in the setting of pediatric patients treated for isolated forearm fractures treated with closed reduction in the emergency department. A cost comparison between the two anesthesia methods is also performed.

The Bier block has proven to be a very safe method of regional anesthesia for over 100 years [1–4, 5]. The method involves placement of an Intravenous (IV) catheter in the patient’s injured extremity while another IV catheter is placed in an unaffected extremity. Routine monitoring of blood pressure, heart rate and rhythm monitoring are instituted. A tourniquet is then placed proximal to the fracture site on the affected extremity. Some have advocated using a double tourniquet to address tourniquet pain [6]. By injecting local anesthetic intravenously in the affected extremity, the retrograde blood flow allows the anesthetic to be distributed throughout the extremity without entering the systemic vasculature. Some have advocated exsanguinating the extremity prior to the procedure although this is not routinely done at our institution. [7]. Once the tourniquet is inflated, 0.5% lidocaine without epinephrine is injected into the IV catheter in the affected extremity. The dose is determined based on patient weight. The average dosing is 3mg/kg of 0.5% lidocaine without epinephrine in the pediatric patient.

We currently use the formula [weight (kg) × 0.6 = volume (ml) of 0.5% lidocaine]. The maximum recommended dose is 30ml. Often the lidocaine injection is followed by an injection of 10 mL of injectable saline as this can help push the volume of lidocaine into the tissues to improve the anesthesia. The tourniquet must be left inflated for 30 minutes and then slowly released monitoring for any signs or symptoms of lidocaine toxicity. This has proven to be a very simple, effective and safe procedure for fracture reduction. The benefits include adequate analgesia, simplicity of technique, low cost, low complication rate, and decreased post-procedure monitoring time [1–4, 5]. Blasier et al. found ninety-nine percent of patients undergoing Bier block anesthesia in upper-extremity fracture care had adequate anesthesia for closed fracture reduction. There were no complications noted. Specifically, there were no incidents of hypotension, tachycardia, seizures or arrhythmias, which have been reported as adverse events in past series [8]. Less than 2% required a general anesthetic in the operating room for further treatment [3]. Still, this procedure is not widely utilized in the U.S. A survey of 63 orthopedic surgeons and 69 emergency medicine physicians in the U.S. and Canada found that only 20% use IVRB routinely for closed reduction of pediatric forearm fractures [9]. However, it is gaining popularity with recent publications presenting the safety and benefits of the procedure along with the relatively lower cost and decreased time spent in the emergency department as compared to conscious sedation [1].

Materials and Methods

IRB approval was granted for a retrospective review of patient charts at our institution. Patient charts from 2005–2014 were reviewed, and those with patients who had isolated closed forearm fractures that required only closed reduction in the emergency department under either Bier block regional anesthesia or conscious sedation were selected for possible inclusion in the study. Patients were excluded if there were other fractures or injuries noted or there was inadequate follow-up. Patient age, sex, fracture type, mechanism of injury, need for further reduction, initial complications, long-term complications, number of follow-up visits, need for further operative reduction, and total weeks of care were gathered.

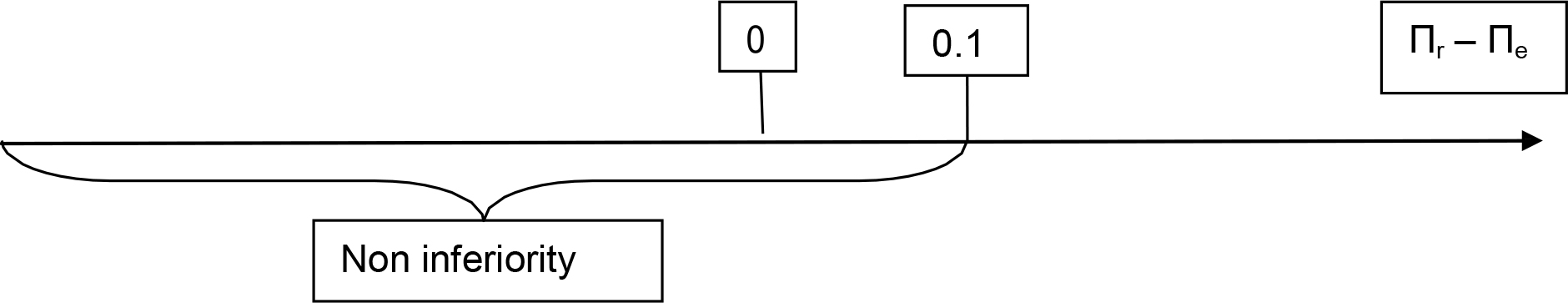

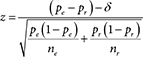

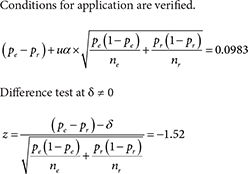

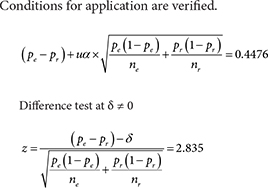

Due to the tendency of our institution to conduct Bier blocks for most forearm fractures and reserve conscious sedation for younger patients, we further limited eligibility of study patients to those between 4 and 7 years of age. Statistical analyses were conducted with SAS v 9.4 (The SAS Institute, Cary, NC) and Excel 2013 (Microsoft Corporation, Redmond, WA). Patient characteristics at presentation (age, sex, year of injury, bone fractured, position of fracture on the bone, mechanism of injury, and days to reduction) were compared between anesthesia groups via Cochran-Armitage trend tests and chi-square tests. The same patient characteristics at presentation were entered together into a logistic-regression model to estimate each subject’s probability or “propensity” to receive Bier block instead of conscious sedation, and the resulting propensity scores were then used to stratify subjects into quintiles. To examine how propensity-score stratification affected the differences in patient characteristics between anesthesia groups, we calculated each characteristic’s standardized difference as the difference in group means divided by the pooled estimate [7] of the groups’ common Standard Deviation (SD). Unadjusted standardized differences were calculated this way across the entire study population, whereas propensity-adjusted standardized differences were calculated as the average across propensity-score quintiles of the standardized difference within each quintile. To compare outcomes between anesthesia groups, we used Fisher’s exact test, the Cochran-Mantel-Haenszel (CMH) correlation chi-square test, and the Wilcoxon Rank-Sum (WRS) test for unadjusted comparisons, and stratified versions of the CMH and WRS tests (with propensity-score quintiles as strata) for propensity-adjusted comparisons. An alpha=0.05 significance level was employed for all statistical comparisons. From the patients who met all eligibility criteria, we gathered the emergency department’s total visit cost for two randomly selected subsamples consisting of 19 conscious-sedation patients and 18 Bier-block patients. This data was used for average cost comparisons between the groups via WRS test.

Results

A total of 1616 patient charts were initially reviewed, and 128 charts met all eligibility criteria. This included 66 patients (52%) who received Bier block anesthesia and 62 patients (48%) who received conscious sedation. Table 1 shows the distribution of patient characteristics at presentation in each group. On average, Bier-block patients were 1.1 years older than conscious-sedation patients (P<0.0001). Additionally, the median year of injury was 2013 in the Bier-block group compared to 2010 in the conscious-sedation group (P=0.0003), due in part to the fact that no Bier blocks (versus 10 conscious sedations) were performed in 2005 or 2006 in the study population. None of the other patient characteristics at presentation (sex, bone fractured, fracture position, injury mechanism, and days to reduction) were significantly different between groups.

Table 1. Patient Demographics

|

Baseline Characteristic

|

Overall

(N=128)

|

Bier Block

(N=66)

|

C. Sedation

(N=62)

|

P*

|

|

Age in years, N (%A):

4

5

6

7

Mean (SDB)

|

28 (22%)

36 (28%)

36 (28%)

28 (22%)

5.5 (1.1)

|

3 (5%)

14 (21%)

27 (41%)

22 (33%)

6.0 (0.9)

|

25 (40%)

22 (35%)

9 (15%)

6 (10%)

4.9 (1.0)

|

<0.0001†

|

|

Sex, N (%):

Female

Male

|

51 (40%)

77 (60%)

|

30 (45%)

36 (55%)

|

21 (34%)

41 (66%)

|

0.18‡

|

|

Year of Injury, N (%A):

2005–06

2007–08

2009–10

2011–12

2013–14

Median

|

10 (8%)

37 (29%)

9 (7%)

29 (23%)

43 (34%)

2011

|

0 (0%)

20 (30%)

1 (2%)

10 (15%)

35 (53%)

2013

|

10 (16%)

17 (27%)

8 (13%)

19 (31%)

8 (13%)

2010

|

0.0003†

|

|

Bone+Position, N (%A):

Radius, Proximal

Radius, Mid-

Radius, Distal

BBFAC, Proximal

BBFAC, Mid-

BBFAC-, Distal

|

4 (3%)

6 (5%)

18 (14%)

2 (2%)

20 (16%)

78 (61%)

|

3 (5%)

3 (5%)

12 (18%)

0 (0%)

10 (15%)

38 (58%)

|

1 (2%)

3 (5%)

6 (10%)

2 (3%)

10 (16%)

40 (64%)

|

–––‡‡

|

|

Bone fractured, N (%A):

Radius

BBFAC

|

28 (22%)

100 (78%)

|

18 (27%)

48 (73%)

|

10 (16%)

52 (84%)

|

0.13‡

|

|

Fracture position, N (%A)

Distal

Mid- or Proximal

|

96 (75%)

32 (25%)

|

50 (76%)

16 (24%)

|

46 (74%)

16 (26%)

|

0.84‡

|

|

Mechanism of Injury, N (%A):

FOOSHD

All other mechanisms

|

99 (77%)

29 (16%)

|

48 (73%)

18 (20%)

|

51 (82%)

11 (11%)

|

0.20‡

|

|

Days to Reduction, N (%)

zero days

one or more days

|

120 (94%)

8 (6%)

|

63 (95%)

3 (5%)

|

57 (92%)

5 (8%)

|

0.41‡

|

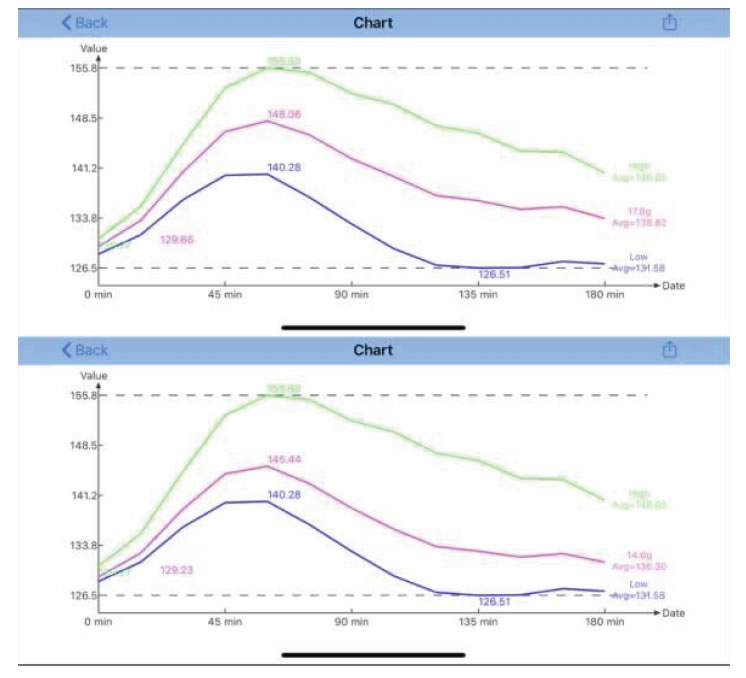

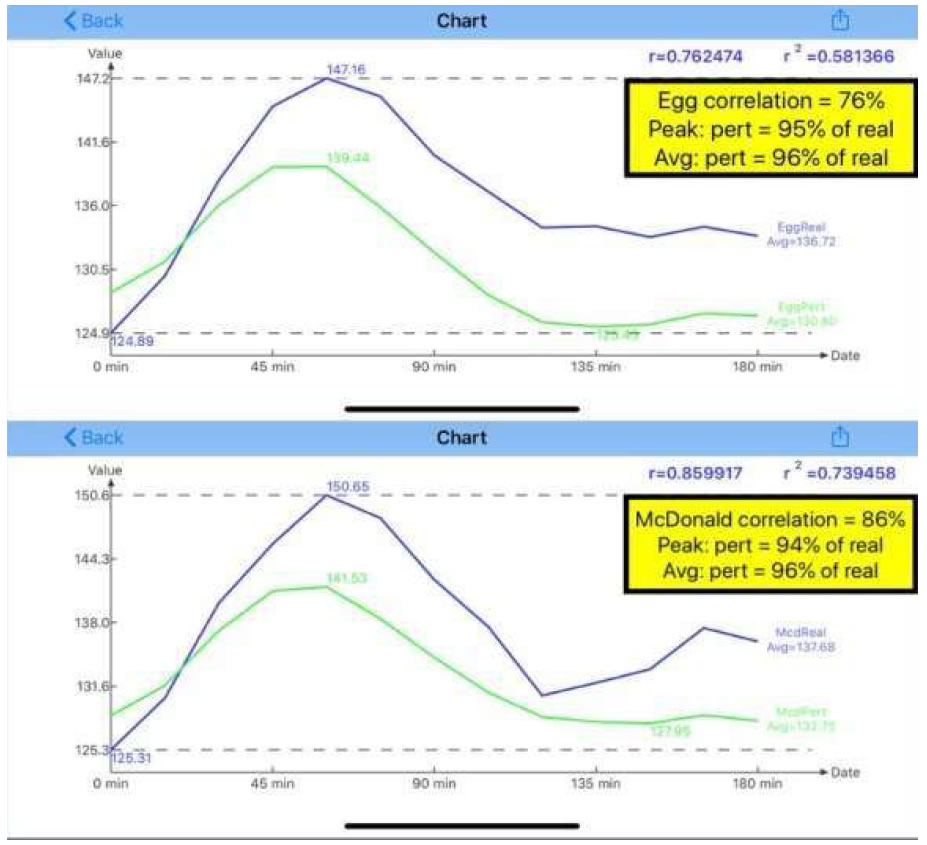

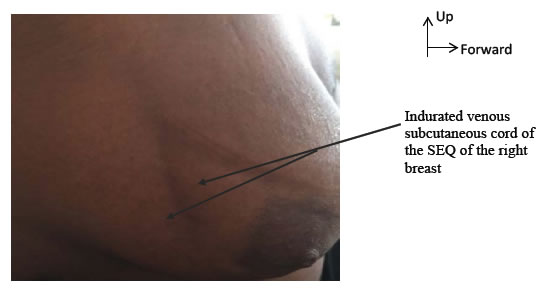

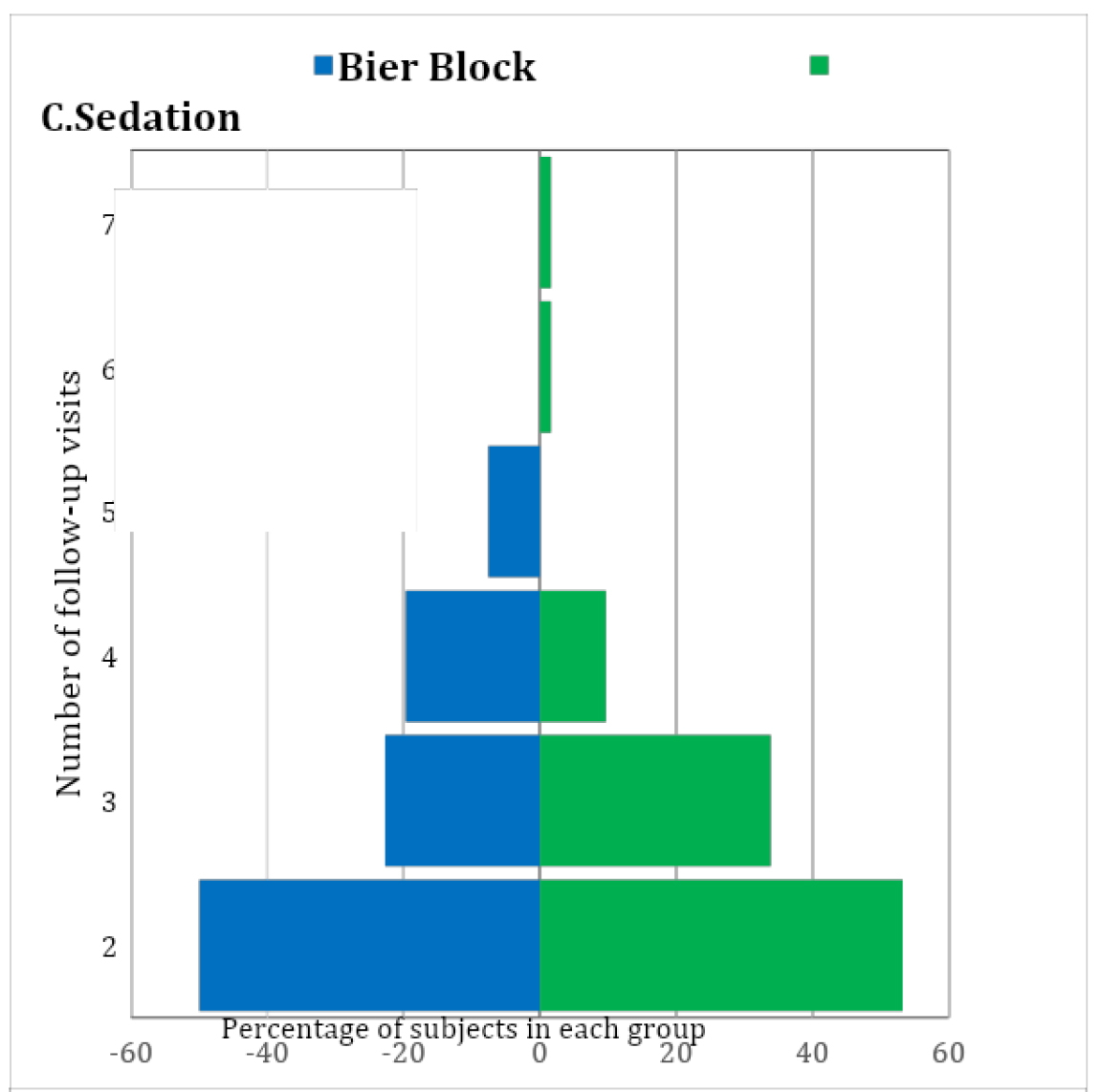

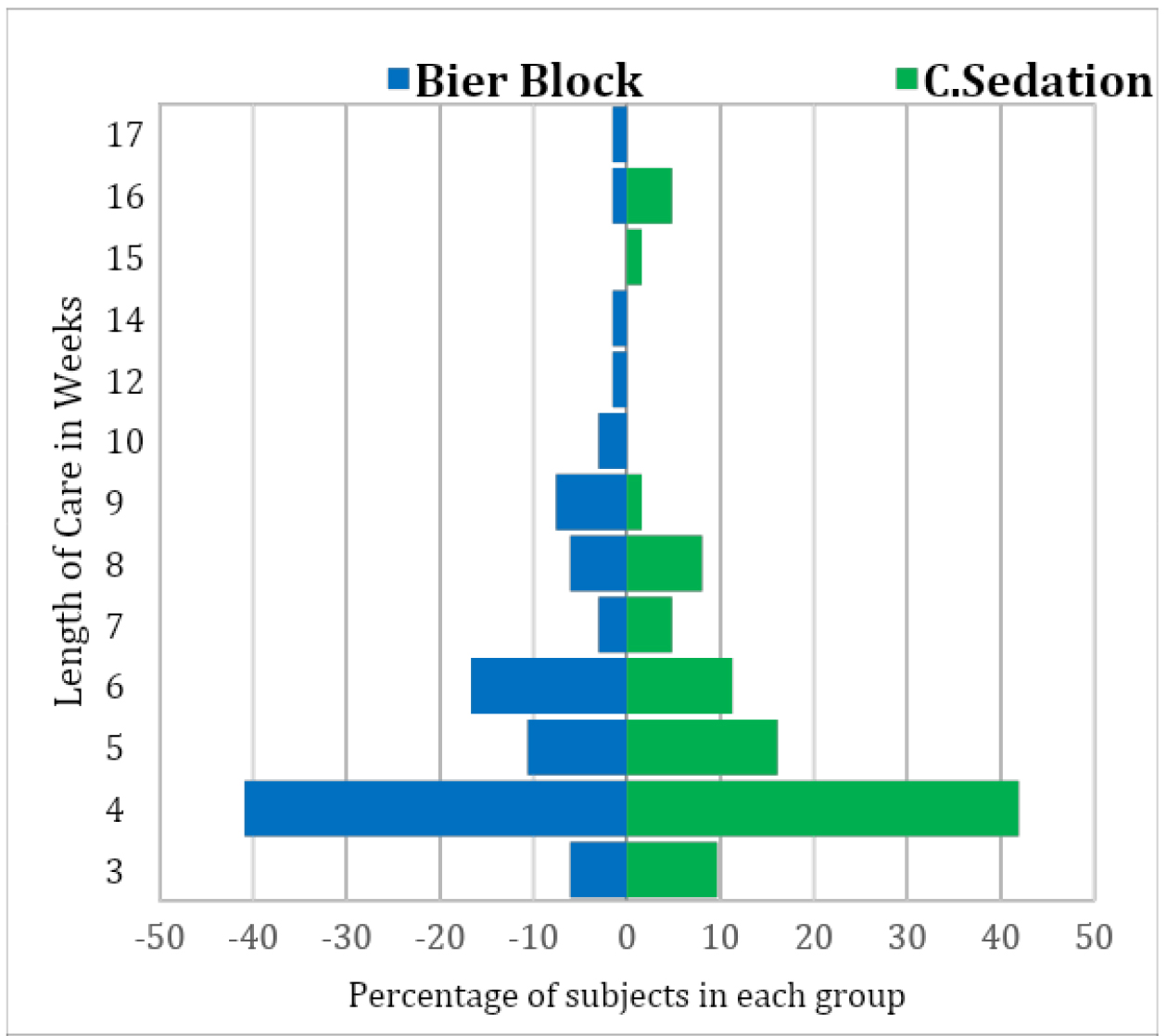

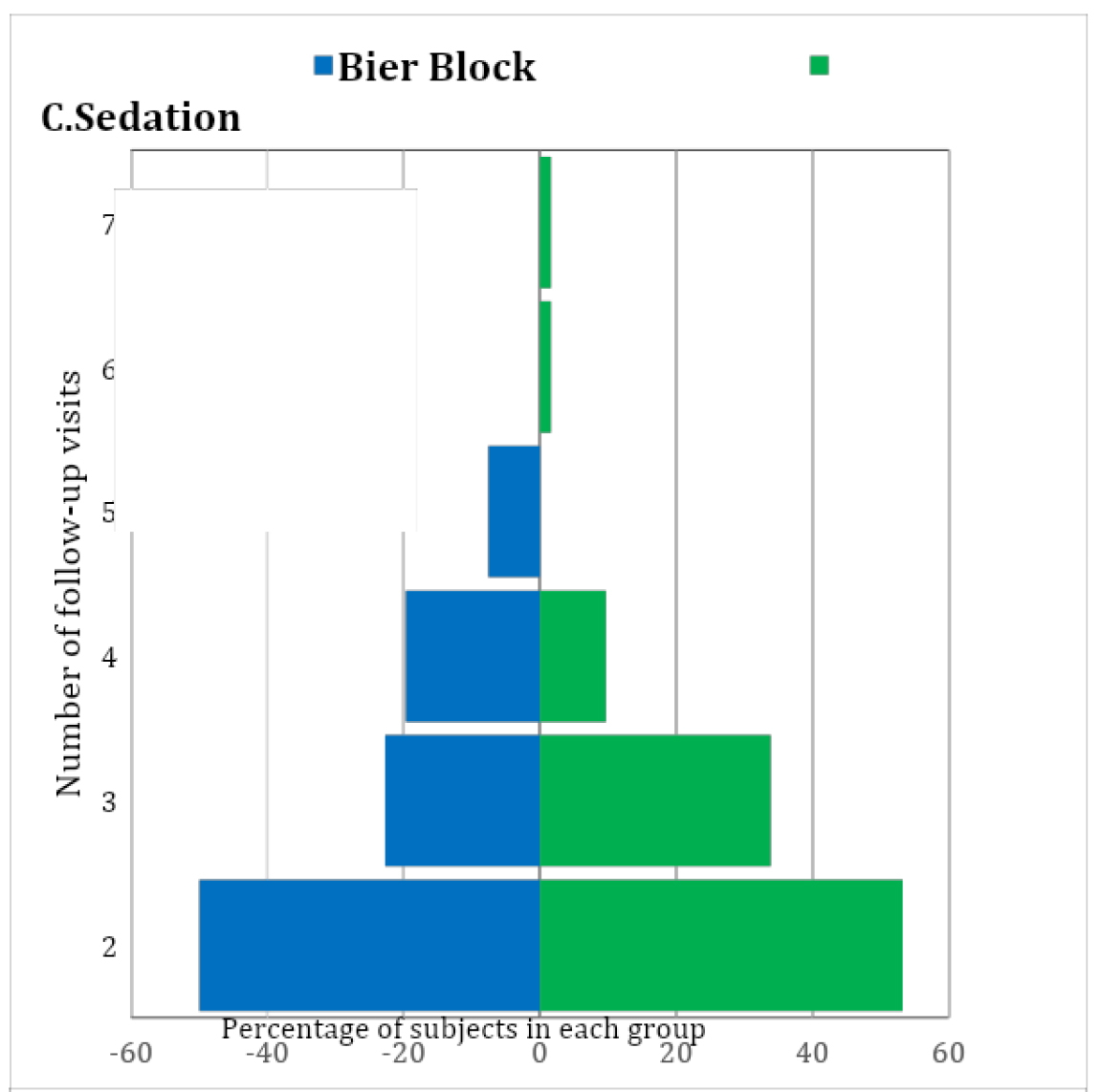

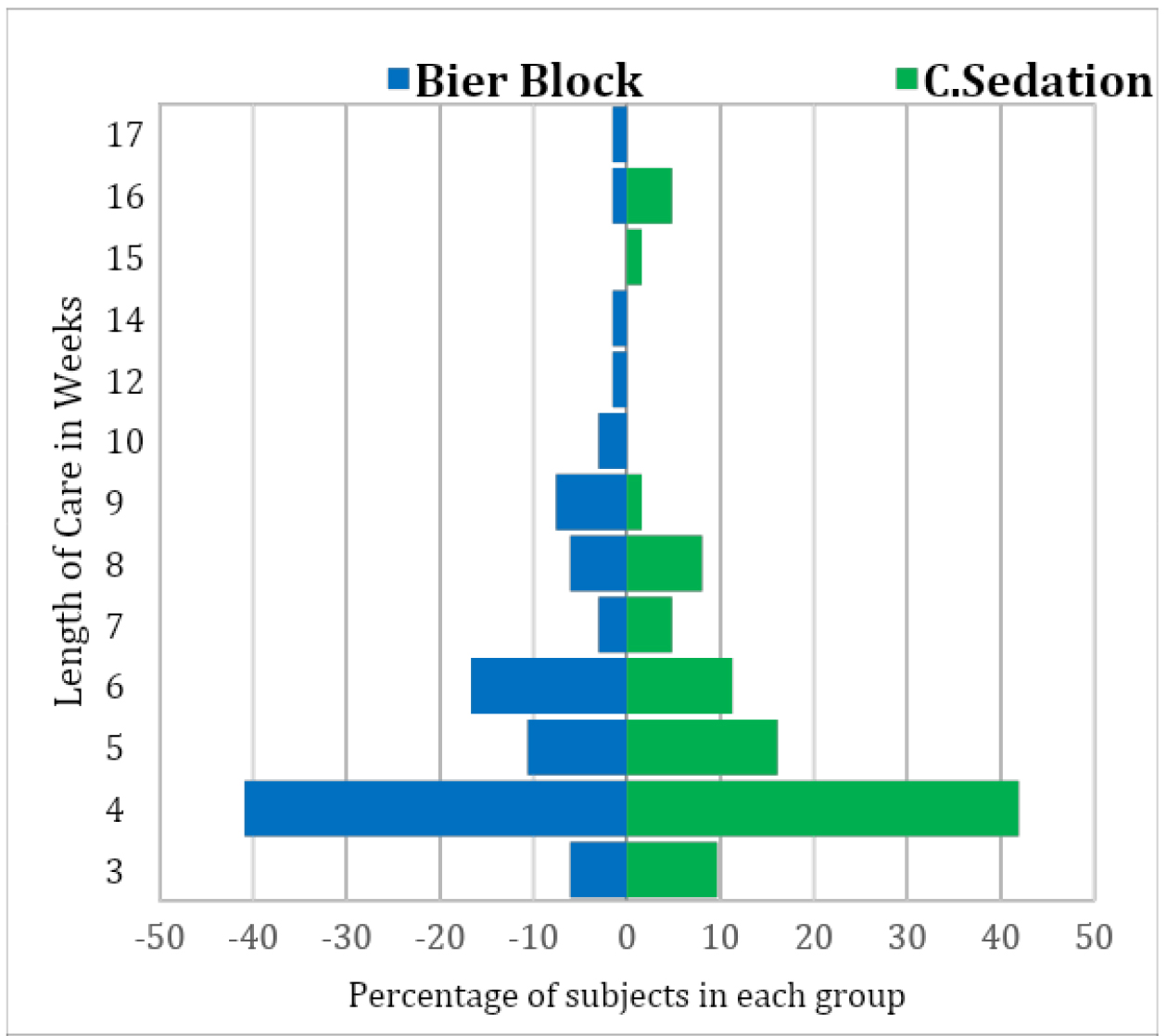

Table 2 shows the distribution of outcomes between groups, and shows both the unadjusted and propensity-adjusted P-values for the outcome differences. There were no initial or long-term complications in either group. Only one Bier-block patient (2%) and three conscious-sedation patients (5%) required more than one attempt at closed reduction. One patient from each group required an operative intervention. The Bier-block patient required Open Reduction Internal Fixation (ORIF) and the conscious-sedation patient required closed reduction under general anesthesia in the operating room. Both additional interventions were needed due to loss of reduction during follow up. The two groups had nearly equal lengths of total care, with an average of 5.9 weeks in the Bier-block group versus 5.6 weeks in the conscious sedation group (propensity-adjusted P=0.82; Table 2 and Figure 2). The number of follow-up visits were also nearly equal between groups, with an average of 2.8 visits in the Bier-block group versus 2.7 visits in the conscious sedation group (propensity-adjusted P=0.54; Table 2 and Figure 1). Table 3 shows that, when the ED visit costs were compared, Bier block was found, on average, to be $423 (26%) less expensive than conscious sedation. The average ED visit cost was $1,601 for conscious sedation versus only $1,177 for Bier block (P=0.0003) [Table 3].

Figure 1: Number of visits distributions between both smethods.

Figure 2: Length of care distribution between both methods.

Table 2. Patient Outcomes between the Two Groups.

|

Outcome

|

Overall

(N=128)

|

Bier Block

(N=66)

|

C. Sedation

(N=62)

|

Unadjusted P*

|

Propensity-adjusted P*

|

|

Initial Complications, N (%A):

None

|

128 (100%)

|

66 (100%)

|

62 (100%)

|

–––

|

–––

|

|

Long-term Complications, N (%A):

None

|

128 (100%)

|

66 (100%)

|

62 (100%)

|

–––

|

–––

|

|

Number of attempts, N (%A):

1 attempt

2 attempts

3 attempts

|

124 (97%)

3 (2%)

1 (1%)

|

65 (98%)

0 (0%)

1 (2%)

|

59 (95%)

3 (5%)

0 (0%)

|

0.66†

|

0.36†

|

|

Need for OR, N (%A):

No

Yes

|

126 (98%)

2 (2%)

|

65 (98%)

1C (2%)

|

61 (98%)

1D (2%)

|

1.00€

|

–––

|

|

Number of follow-ups, N (%A):

2 visits

3 visits

4 visits

5 visits

6 or 7 visits

#visits, Mean (SDB)

#visits, Range

|

66 (52%)

36 (28%)

19 (15%)

5 (4%)

2 (2%)

2.8 (1.0)

2.0–7.0

|

33 (50%)

15 (23%)

13 (20%)

5 (8%)

0 (0%)

2.8 (1.0)

2.0–5.0

|

33 (53%)

21 (34%)

6 (10%)

0 (0%)

2 (3%)

2.7 (1.0)

2.0–7.0

|

0.32§

|

0.54§

|

|

Total length of care, N (%A):

3 weeks

4 weeks

5 weeks

6 weeks

7 weeks

8 weeks

9–12 weeks

13–17 weeks

#weeks, Mean (SDB)

#weeks, Range

|

10 (8%)

53 (41%)

17 (13%)

18 (14%)

5 (4%)

9 (7%)

9 (7%)

7 (5%)

5.8 (3.0)

3.0–17.0

|

4 (6%)

27 (41%)

7 (11%)

11 (17%)

2 (3%)

4 (6%)

8 (12%)

3 (3%)

5.9 (3.0)

3.0–17.0

|

6 (10%)

26 (42%)

10 (16%)

7 (11%)

3 (5%)

5 (8%)

1 (2%)

4 (6%)

5.6 (3.1)

3.0–16.0

|

0.32§

|

0.82§

|

Table 3. Cost Distribution Analysis

|

|

IVRB1

|

CS2

|

|

Mean (SD3)

|

$1,177.34 ($253.61)

|

$1,600.98 ($339.19)

|

|

Median

|

$1,101.71

|

$1,531.77

|

|

Quartiles

|

$982.26 – $1,318.48

|

$1,309.91 – $1,923.62

|

|

Range

|

$846.75 – $1,726.27

|

$1,063.76 – $2,233.47

|

|

WRS4 test result

|

P=0.0003

|

|

Discussion

The two main aims of this study were to determine if Bier block regional anesthesia is a safe, effective, and cost-efficient method of anesthesia for pediatric forearm fracture reduction in the emergency department, and to compare the short- and long-term complications and outcomes of Bier-block patients with those of conscious-sedation patients chosen for their overlapping age range. Our institution has a long experience with using Bier blocks in these patients, and we have had found the procedure in children to be both safe and effective. Bier block anesthesia was found to be as safe as conscious sedation in our final study group. Neither final study group had any instance of short-term or long-term complications; specifically, no instances of lidocaine toxicity, compartment syndrome, need for hospital admission for pain control after the procedure, nerve palsy or growth arrest. No child required conversion from Bier block anesthesia to conscious sedation due to inadequate pain control or anxiety despite having a younger group of patients ranging from 4 to 7 years of age. This is a common concern with using Bier block anesthesia in the younger awake child. In our institutional experience, the need for conversion from Bier block to conscious sedation due to inadequate anesthesia or anxiety is very rare. Our emergency department has child life specialists available who can assist in the procedure if needed in the more anxious children by providing distraction and entertainment in the form of reading or tablet usage for games.

One of the aims of this study was to assess follow up data for these two groups. With the rising costs in providing medical care, minimizing the need for, and number of, follow up clinic appointments is valuable. We found that both groups had nearly equal follow up time length and number of follow up visits and both were quite low. Certainly patients in our study’s age group are considered to have very wide tolerances for what constitutes an acceptable fracture reduction due to their tremendous ability to remodel deformity but our data shows that these two methods are equally effective at preventing patients from requiring surgical intervention. One patient in each group did require operative intervention due to inadequate reduction in the emergency department or loss of reduction in follow up, resulting in a 2% rate in each group of a need for surgical intervention in the operating room. The Bier block patient required ORIF and the conscious sedation patient required further closed reduction without internal fixation under general anesthesia.

Some weaknesses of our study include the small patient group sizes. We found it necessary to restrict the age range from the original data that included all patients with forearm fractures, and limit the study to patients who were between 4 and 7 years old. This was due to several factors. First, the majority of patients at our institution receive a Bier block as their form of anesthesia for forearm fracture reduction in the emergency department. If conscious sedation is performed, it is usually reserved for younger patients or the more anxious patients who we perceive may not tolerate a Bier block as well. We were unable to effectively compare the two larger, more inclusive groups due to the large number of Bier-block anesthesia patients and low number of conscious-sedation patients overall and the age differences between the two groups. By lowering and narrowing the age range, we were able to obtain an average age of 6 years in the Bier block group and 5 years in the conscious sedation group. This allowed for more clinically useful comparable data points, but limited the number of patients we were able to compare.

Distributions of the total number of follow-up visits in the Bier-block and conscious-sedation groups, showing that the two groups have very similar distributions. See Table 2 for the means, SDs, and ranges of the distributions.

Distributions of the total length of care in weeks for the Bier-block and conscious-sedation groups, showing that the two groups have similar distributions. See Table 2 for the means, SDs, and ranges of the distributions.

An additional weakness of the study was the probable violation of the “no unmeasured confounders” assumption required for valid propensity-score-based analysis. In addition to each patient’s age and year of injury, we collected their sex, the bone fractured and position of the fracture on the bone, the mechanism of injury, and the number of days to reduction, but not the patient’s race. Race is a pervasive confounder in health-care research that can lead to treatment disparities, not only through provider biases or income disparities, but also through the perceptions and comfort levels of the patients and their parents. Thus, race could easily have been confounded with the choice of anesthesia method in our study. However, it should be said that ours is an equal-access institution where all patients are treated the same regardless of race or socioeconomic background, and this fact should reduce some (if not all) of the unmeasured confounding of race with anesthesia method.

Emergency department visit cost analysis was included in this study for the reason of fiscal responsibility. Bier block anesthesia has been shown to be safe and effective with less total time in the emergency department compared to conscious sedation [7]. We also show an average cost savings of $423 in using Bier block anesthesia compared to conscious sedation. Bier block anesthesia also has the added benefit of not requiring significant specialized post-procedural monitoring that requires trained emergency-department staff that could otherwise be treating another patient. Bier block anesthesia patients do not require any further monitoring after the reduction, which allows for staff to be freed up and, in theory, diminish patient room utilization time. In a high-volume pediatric hospital, decreasing visit time is essential for having an efficient emergency department. We attempted to prove this theory in our study comparing time data between the conscious sedation and Bier block groups, but there were significant limitations with our ability to do that accurately. These limitations included incomplete charting regarding admit and discharge time and NPO status of those patients receiving conscious sedation affecting the wait time before reduction.

Bier block anesthesia is a safe and cost-effective form of anesthesia for pediatric forearm fracture closed reduction in the emergency department in patients between 4 and7 years of age. It has continued to be proven to be safe throughout the years and continues to be shown to be more time and cost effective. Short-term and long-term complication rates are low and are similar to those seen in patients treated with conscious sedation. Follow up time and number of visits are similar between the two groups as well. However, Bier block anesthesia was found to cost significantly less than conscious sedation in our series. We theorize that there are additional indirect cost savings with Bier block compared to conscious sedation as a result of (1) the diminished need for specialized and lengthy monitoring of the patient after the procedure, (2) the NPO status of the patient having no effect on our ability to perform and timing of proceeding with the Bier block, and (3) the efficiency with which one can perform the Bier block in an emergency department setting, although we did not attempt to prove that in this study. Continued research in this field will continue to shed light on this useful method of emergency room treatment of pediatric forearm fractures.

Conflict of Interest

The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

Statement of Human and Animal Rights

All procedures followed were in accordance with the ethical standards of the responsible committee on human experimentation (institutional and national) and with the Helsinki Declaration of 1975, as revised in 2008 (5). No identifying information was included in this study.

Statement of Informed Consent

Informed consent was not obtained due to the retrospective nature of this study with no identifying patient information presented in the study. All data was collected under IRB institutional guidelines.

Statement of Funding

No funding was received by any authors for this study.

References

- Aarons CE, Fernandez MD, Willsey M, Peterson B, Key C, et al., (2014) Bier block regional anesthesia and casting for forearm fractures: safety in the pediatric emergency department setting. J Pediatr Orthop 34: 45–49.

- Barnes CL, Blasier RD, Dodge BM (1991) Intravenous regional anesthesia: a safe and cost-effective outpatient anesthetic for upper extremity fracture treatment in children. J Pediatr Orthop 11: 717–720. [Crossref]

- Blasier RD, White R (I1996) Intravenous regional anesthesia for management of children’s extremity fractures in the emergency department. Pediatr Emerg Care 12: 404–406.

- Colbern E (1970) The Bier block for intravenous regional anesthesia: technique and literature review. Anesth Analg 49: 935–940.

- Mohr B (2006) Safety and effectiveness of intravenous regional anesthesia (Bier block) for outpatient management of forearm trauma. CJEM 8: 247–250.

- Perlas A, Peng PW, Plaza MB, Middleton WJ, Chan VW, et al., (2003) Forearm rescue cuff improves tourniquet tolerance during intravenous regional anesthesia. Reg Anesth Pain Med 28: 98–102. [Crossref]

- Yang E (2017) Green’s Operative Hand Surgery. 2: 10–11.

- Constantine E, Steele DW, Eberson C, Boutis K, Amanullah S, et al., (2007) The use of local anesthetic techniques for closed forearm fracture reduction in children: A survey of academic pediatric emergency departments. Pediatr Emerg Care 23: 209–211. [Crossref]

- Guay J (2009) Adverse events associated with intravenous regional anesthesia (Bier block): A systematic review of complications. J Clin Anesth 21: 585–594.

- Mendenhall W, Beaver RJ, Beaver BM (2009) Introduction to Probability and Statistics 13th Edition, Cengage Learning, [multiple cities and countries], ISBN-10: 0495389536, Page 403.