Abstract

Di-2-Ethylhexyl Phthalate (DEHP) is the widely used to convey flexibility and transparency to plastic products made of polyvinyl chloride and also in the manufacture of medical devices. DEHP disrupts reproductive tract development in an antiandrogenic manner and also may induce neurobehavioral changes. In previous works, we demonstrated that chronic postnatal exposure to DEHP alters the neuroendocrine regulation of the testicular axis, modifying the hypothalamic concentration of excitatory neurotransmitters and therefore induces an anxiogenic effect. In the Elevated Plus Maze (EPM) test, dizocilpine (MK-801) induces a decrease in anxiety-related behaviors throughout NMDA receptor blockade. The objective of this work was to investigate whether the blockade of NMDA receptors of glutamate by the non-competitive antagonist MK-801 could modify the anxiety-like behavior induced by chronic postnatal exposure to DEHP (30 mg/kg body weight/day, orally from birth) in young adult male rats in the EPM test. The results show that NMDA receptor blockade by MK-801 (0.1 mg/kg body weight, i.p.) in DEHP exposed animals is able to produce a significant decrease in time spent in closed arms (TSC) and in Freezing Time (FT) as well as an increase in time spent in open arms (TSO) in the EPM test, indicating an anxiolytic effect. In conclusion, our results suggest: 1) NMDA receptor blockade by MK-801 can reverse anxiety-like behavior induced by exposure to DEHP during the early period of life. 2) The glutamatergic system is involved in the anxiogenic effect of phthalate, which is probably triggered by its known antiandrogenic action.

Keywords

DEHP; Endocrine Disruptor; Dizocilpine (MK-801); Glutamate Receptors; Anxiety like-behavior

Introduction

N-Methyl-D-Aspartate (NMDA) receptor-mediated glutamate transmission is one of the most significant mechanisms during multiple stages of brain development and has been implicated in cognitive functions and emotional responses [1]. It has been suggested that during the early neurodevelopmental period the treatment with non-competitive antagonist of NMDA receptors such as dizocilpine (MK-801), can cause long-term effects in the anatomical, neurochemical, neurophysiological and behavioral features of rodents [2,3]. Indeed, there are evidences that MK-801 has an anxiolytic potential [4–6]. During the critical period of brain maturation, MK-801 induces locomotor hyperactivity and decreases anxiety levels in adolescent rats.6 In the elevated plus maze (EPM) test a decrease was observed in anxiety-related behaviors caused in adult male mice by MK-801 in the early developmental period [7]. NMDA receptor blockade could reduce neuronal activity in pathways which lead to the release of GABA or monoamines, and which have themselves been implicated in anxiety-related processes [8].

Di-2(ethyl-hexyl phthalate) (DEHP) is an endocrine disruptor with antiandrogenic action, which is used as a plasticizer in many products, especially in medical devices and in manufacturing a wide variety of consumer products made with Polyvinyl Chloride (PVC) [9]. The brain has been determined to be at risk of DEHP exposure. Gestational and postnatal exposure to DEHP can affect neurodevelopment and lead to anomalies by disrupting normal brain development and function [10]. In previous works, we demonstrated that chronic postnatal exposure to DEHP alters the neuroendocrine regulation of the testicular axis, modifying the hypothalamic concentration of excitatory and inhibitory neurotransmitters [11,12]. DEHP could act on anxiety in different ways depending on the treatment, age, and sex of the animals [13–16]. It has been reported that postnatal exposure to DEHP can induce anxiogenic effect in pre and peripubertal male rats but not in females in the same stages of sexual maturation. Moreover, it has been proposed that the decrease in testosterone levels induced by postnatal exposure to DEHP could be one possible mechanism underlying DEHP anxiogenic-like behavior in immature male rats [17]. Recently, we have demonstrated that GABA agonists, muscimol and baclofen, can reverse DEHP neuroendocrine effects as well as its anxiogenic action in young adult male rats, supporting the notion that GABAergic system may be one of the neurotransmitter systems involved in the effects produced by DEHP exposure during early periods of neurodevelopment [18].

On these bases we hypothesized those DEHP-induced modifications in the concentration of excitatory amino acids in the brain of immature rats [11,12] could also have a modulatory role in the anxiogenic behavior induced by exposure to this endocrine disruptor during early periods of neurodevelopment. Therefore, the objective of this study was to investigate whether the blockade of NMDA receptors of glutamate by the non-competitive antagonist MK-801 could modify the anxiety-like behavior induced by chronic postnatal exposure to DEHP in young adult male rats in the elevated plus maze (EPM) test.

Materials and Method

All animal procedures were performed following the protocols of the National Institute of Health—Guide for the Care and Use of Laboratory Animals. The approval to conduct the study was granted by the Animal Care and Ethics Committee of the School of Medicine, Universidad de Buenos Aires (UBA; CICUAL).

Animals

Wistar rats used were provided by the Department of Physiology, School of Medicine, UBA, Argentina. Animals were kept under a controlled environment (temperature 22–24C; lights on from 7.00 h to 19.00 h) and they had free access to food and filtered water, until the time of killing. All animals were fed with balanced food for laboratory rodents (Cooperation, ACA-16014007, Asociación de Cooperativas Argentinas-División de Nutrición Animal). The diet contained 15% of soy, but as the food used and the quantity of food intake by control and DEHP-treated groups were similar, we assumed that all animals were exposed to equivalent levels of food-borne phytoestrogens. Moreover, the same lots of diet were provided to animals from all groups at the same time, during the course of the study, to control across groups for possible variation in the diet content. We used ultrapure-filtered water (obtained from EDS-Pack, Millipore Merck, installed in the Milli-Q water system) that was presumed to be free of phthalates and other Endocrine Disruptors (EDs). To minimize additional exposures to substances that may act as EDs, rats were housed in stainless steel cages with wood beddings and water was supplied in glass bottles.

Drugs and Doses

DEHP was purchased (1 g/ml>99% pure; Aldrich Chemical Company, Inc., Milwaukee, Wisconsin, USA) and the final solution administered to the animals was made up fresh daily by adding 200 ml of DEHP to 1 l of filtered water to reach a concentration of 0.2 mg/ml and sonicating for 30 min to ensure a permanent and homogenized solution. An oral route in DEHP administration was chosen intending to mimic best the most common route of human exposure to the ED. The estimated average DEHP dose of exposure was 30 mg/kg body weight (BW)/day, based on the daily intake of DEHP solution and the weight of the related animal. Liquid consumption was measured calculating the difference between the amount of liquid placed in the bottle every day and the remaining amount on the following day to assess the intake. It was assumed that all DEHP solution missing in the bottle had been consumed by the animals. Assessments did not contemplate possible leakage or evaporation of the solution or potential loss of DEHP activity during the 24-h period. No significant differences between the amount of liquid consumed by dams and pups receiving DEHP and those which did not receive this chemical were found. The dose was chosen based on prior studies published by us, in which we demonstrated alterations in the reproductive axis and in the behavior in immature male rats exposed to DEHP at a dose of 30 mg/kg BW/day but not in animals exposed to a lower dose (3 mg/kg BW/day) [11,12,17,18].

On the other hand, MK- 801 ([(+)-3 (2-carboxypiperazine-4-yl) propyl-1-phosphonic acid]; Research Biochemicals Inc., Natick, Mass, USA) was dissolved in saline and injected at dose of 0.1 mg/kg BW, i.p., 1 h before performing the behavioral test. MK-801 can be administered intraperitoneally because it crosses easily the blood-brain barrier. The chosen dose does not produce toxic effects [19].

Experimental Design

Pregnant dams were placed individually in metallic cages and upon delivery, pups were sexed; male pups were separated and distributed with one surrogate dam (n= eight male pups per dam). On postnatal day (PND) 1, surrogate dams with their male pups were randomly assigned into control (C) and DEHP exposure groups. Dam’s exposure to DEHP began on PND 1 and continued until weaning. On PND 21, pups of each group continued receiving the same treatment until PND 60. On this day, control and DEHP-exposed male pups were randomly assigned (n= 8 animals per group) to the following treatments: (1) W + S: controls that were given water and injected with saline; (2) DEHP + S: animals that were given DEHP and injected with saline; (3) W+ MK-801: animals that were given water and injected with MK-801; (4) DEHP + MK-801: animals that were given DEHP and injected with MK-801. After receiving the MK-801 or the vehicle, animals were submitted to the behavioral test.

EPM test

The elevated plus maze (EPM) test is a widely used behavioral assay for rodents, and it has been validated to assess the antianxiety effects of pharmacological agents and steroid hormones and to define mechanisms underlying anxiety-related behavior [20]. The EPM apparatus consists of two open arms (10 x 50 cm), alternating in right angles with two closed arms (10 x 50 x 10 cm), delimiting a central area. The maze was elevated 50 cm above the floor. Before starting the test, animals were individually placed in a rectangular plastic glass area (40 × 40 cm) for 5 min in order to habituate them to the test environment. After that, the rats were placed in the central area of the maze, facing one of the closed arms, and were allowed to explore it for 5 min. The maze’s arms were equally illuminated so that the animals did not perceive lighting differences. Behavioral tests were performed from 12: 00 h to 14: 00 h. We used 10% ethanol to clean each arm of the maze and to remove olfactory cues every time between trials. Each rat was tested only once. The animal’s behavior was videotaped and the number of entries and the time spent in both, open and closed arms, were measured by an observer. The parameters measured were: Time Spent in Open (TSO) and Closed (TSC) arms, Total number of Entries (TE) and Time of Freezing (FT). These parameters were measured following a four-paw criterion; entry into the arm of the EPM was defined as the animal placing all four paws in that particular part of the maze. It is considered that anxiety-like behavior is characterized by a decrease in TSO and an increase in TSC. On the other hand, TE provides a built-in control measure for general hyperactivity or sedation. TSO, TSC and FT were expressed in seconds.

Statistical Analysis

Results are presented as means ± SEM. The statistical analysis was based on individual offspring numbers. The surrogate dam was not used as the unit. Therefore, we did not consider the potential effects of the surrogate dam in the statistical analysis, as pups were exposed to this chemical through her milk. All data were checked for normality by the Kolmogorov–Smirnov test and then, they were analyzed using Kruskal-Wallis test (non-parametric ANOVA); posthoc Mann Whitney (Bonferroni correction) to compare unpaired groups. The statistical software used was GraphPad InStat 3 and a difference was considered statistically significant when p < 0.05.

Results

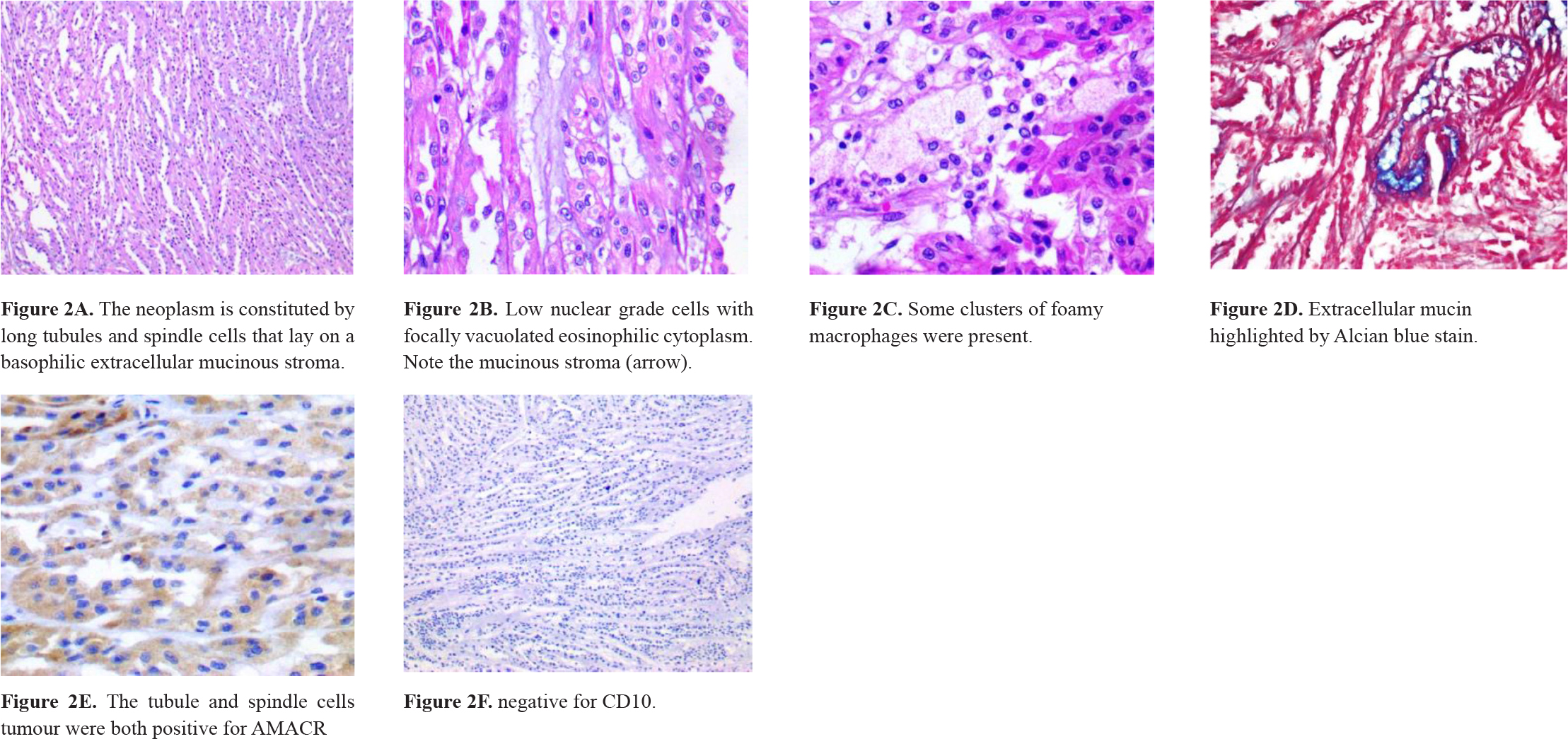

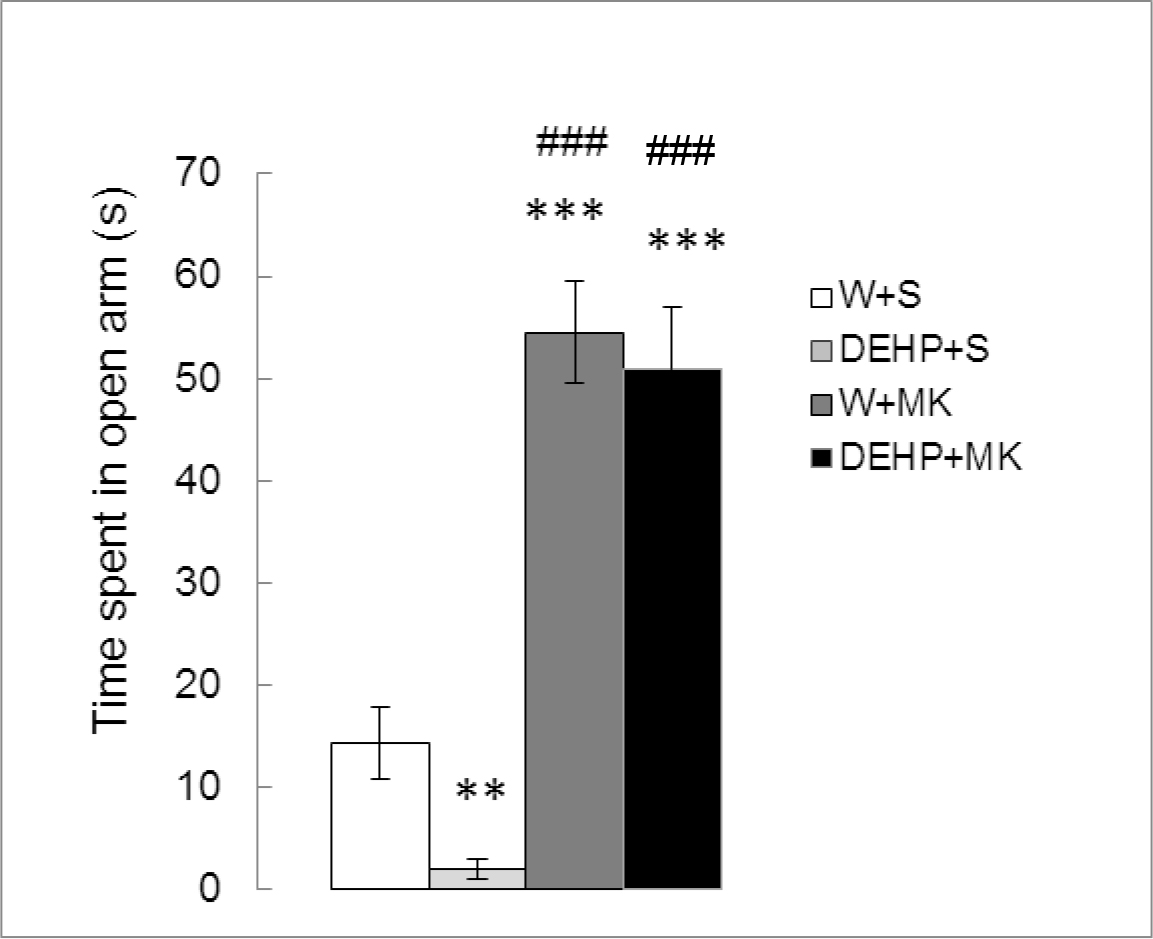

Figure 1 shows the effect of MK-801 on TSO in adult male rats exposed to DEHP from birth. Significant differences between treatments were found (K (3) =25.860, p < 0.0001). When compared with the control group, a significant decrease in TSO were observed in rats exposed to DEHP (DEHP+S vs W+S, p < 0.01) while MK-801 treatment increased this parameter (W+MK vs W+S, p <0.001). MK-801 also produced an increase in TSO with respect to DEHP-exposed group (W+MK vs DHEP+S, p < 0.001) and was able to reverse the effect of the endocrine disruptor (DEHP+MK vs DEHP+S, p<0.001). No significant differences were found between W+MK and DEHP+MK groups, p=0.7984).

Figure 1. Effect of acute administration of MK-801 on the time spent in open arms in adult male rats exposed postnatally to DEHP. W: water; S: saline; DEHP: di-2(ethyl-hexyl phthalate; MK: MK-801. ** p<0.01 vs W+S; *** p<0.001 vs W+S; ### p<0.001 vs DEHP+S. Each value represents the mean ± SEM of eight animals per group.

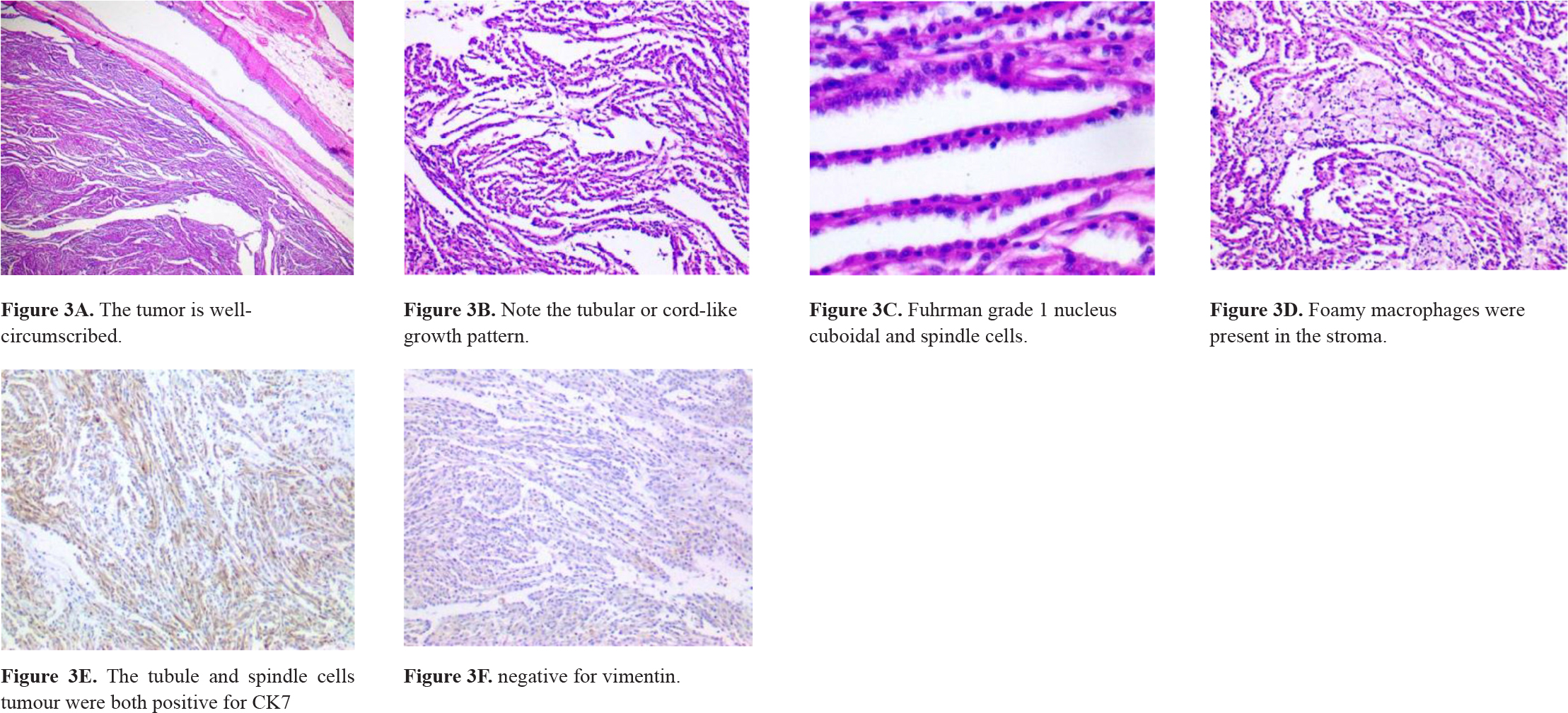

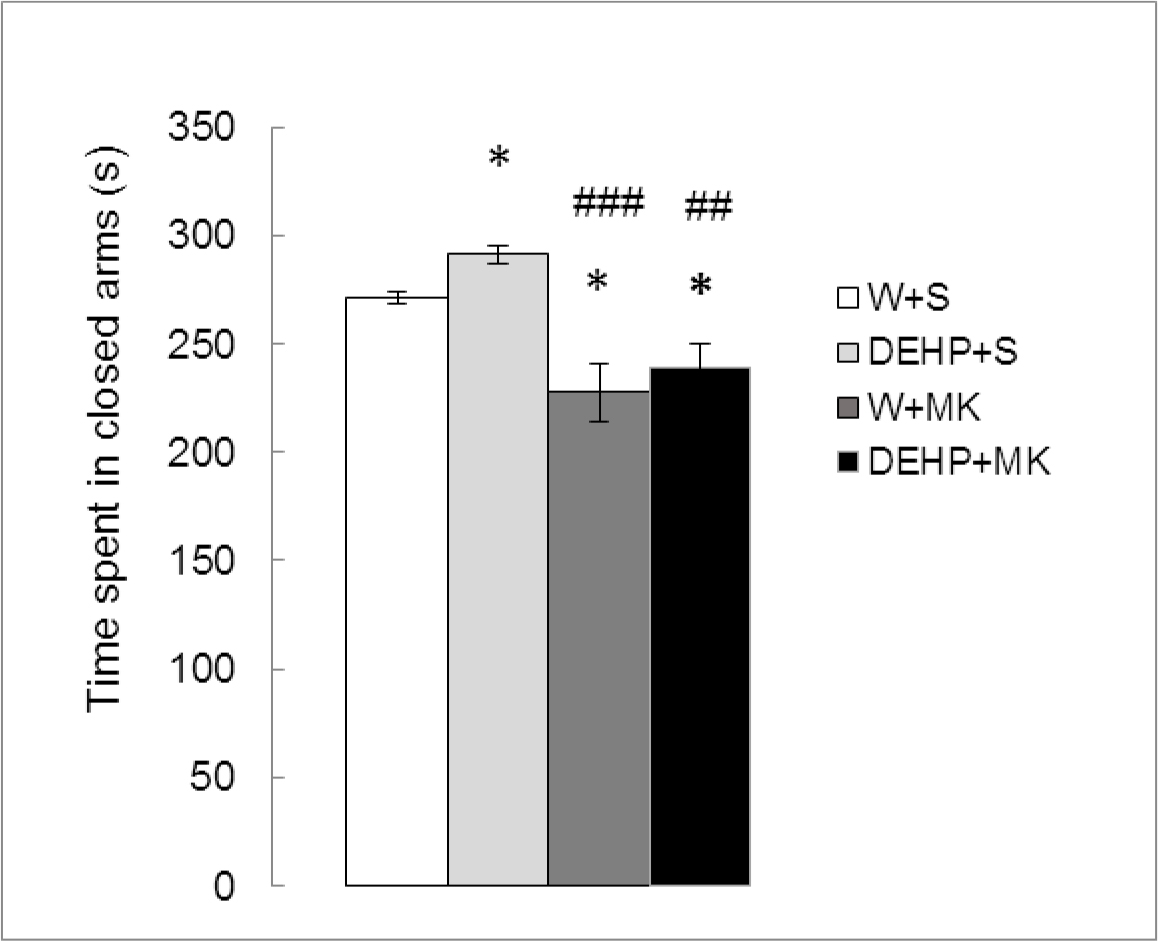

As can be seen in Figure 2, there were significant differences in TSC between treatments (K (3) = 14.809, p<0.01). DEHP significantly increased the TSC compared to the control group (DEHP+S vs W+S, p < 0.05) while MK-801 produced a significant decrease (W+MK vs W+S, p < 0.05) and reversed the effect of DEHP (DEHP+MK vs DEHP+S, p<0.01).

Figure 2. Effect of acute administration of MK-801 on the time spent in closed arms in adult male rats exposed postnatally to DEHP. W: water; S: saline; DEHP: di-2(ethyl-hexyl phthalate; MK: MK-801. * p<0.05 vs W+S; ## p<0.01 vs DEHP+S; ### p<0.001 vs DEHP+S. Each value represents the mean ± SEM of eight animals per group.

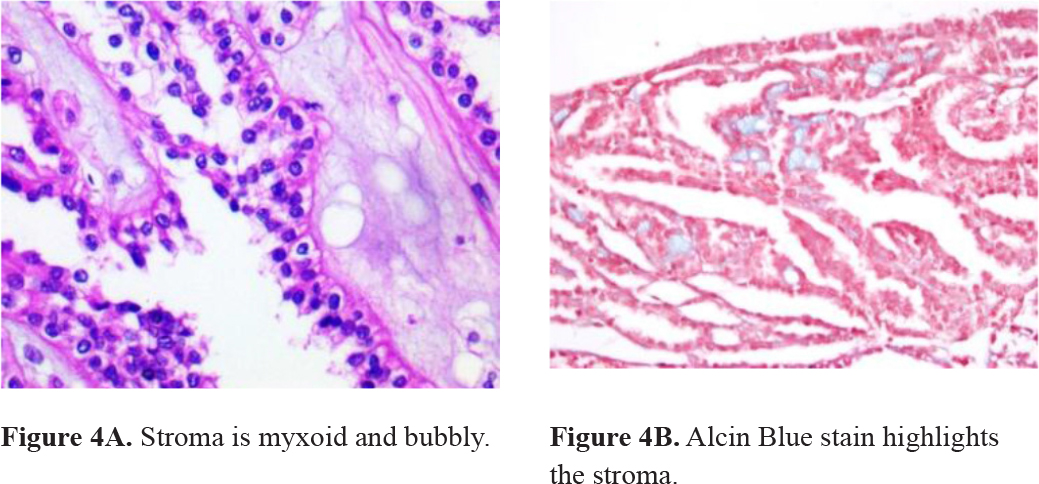

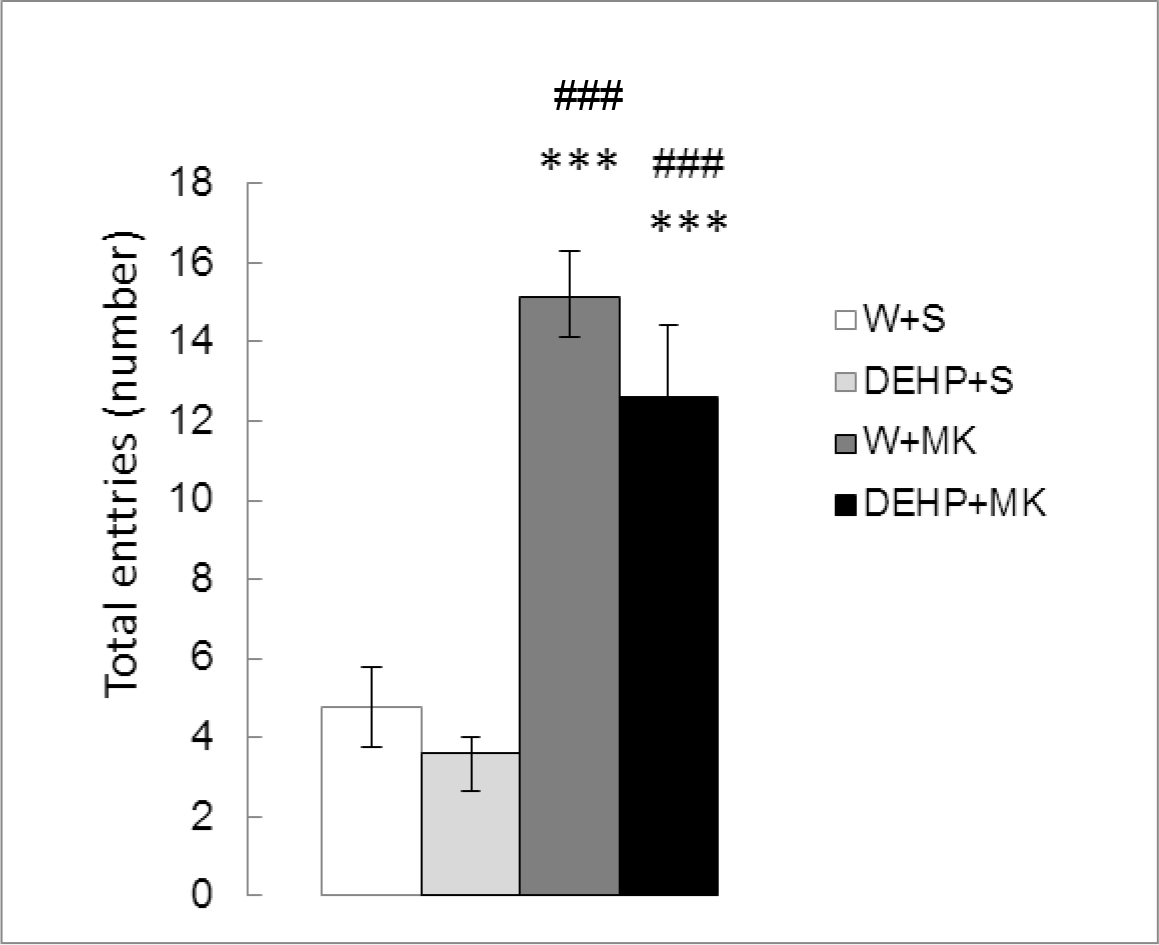

Figure 3 shows the number of total entries in both arms of the maze. Significant differences were detected between treatments (K (3) = 23.642, p<0.001). As expected, there were no significant differences in DEHP-treated animals with respect to the control group (DEHP+S vs W+S, p =0.2627). MK-801 produced a significant increase in TE (W+MK vs W+S, p < 0.001). The same effect was observed with DEHP + MK (DEHP+MK vs DEHP+S, p<0.001). No differences were found between both groups treated with MK-801 (DEHP+MK vs W+MK, p=0.2475).

Figure 3. Effect of acute administration of MK-801 on the number of total entries in adult male rats exposed postnatally to DEHP. W: water; S: saline; DEHP: di-2(ethyl-hexyl phthalate; MK: MK-801. *** p<0.001 vs W+S; ### p<0.001 vs DEHP+S. Each value represents the mean ± SEM of eight animals per group.

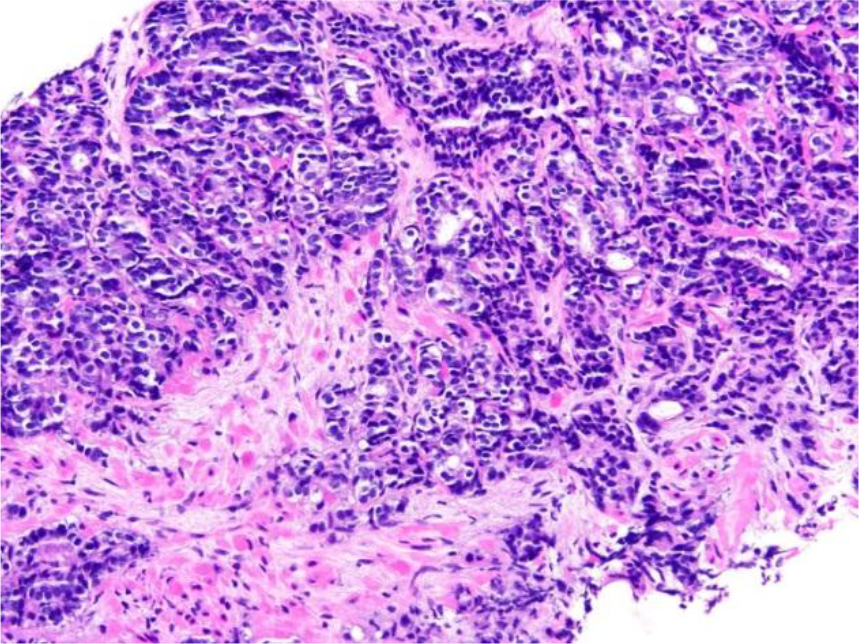

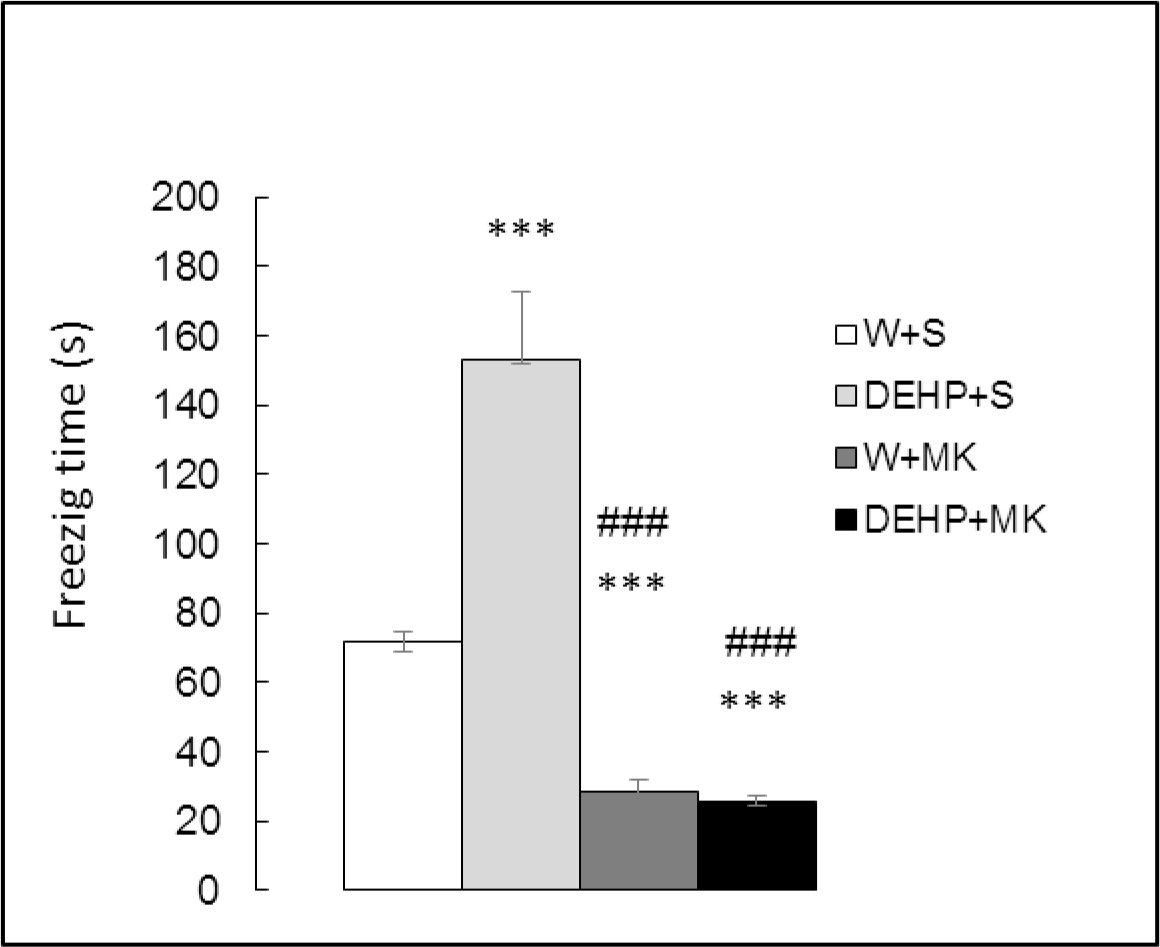

Time spent in freezing behavior (Figure 4) showed significant differences between groups (K(3) = 26.042, p<0.001). There was a significant increment in DEHP-exposed rats (DEHP+S vs W+S, p<0.001) and a significant decrease in animals injected with MK-801 (W+MK vs W+S, p<0.001). In addition, MK-801 antagonized the effect of DEHP ((DEHP+MK vs DEHP+S, p<0.001).

Figure 4. Effect of acute administration of MK-801 on freezing time in adult male rats exposed postnatally to DEHP. W: water; S: saline; DEHP: di-2(ethyl-hexyl phthalate; MK: MK-801. *** p<0.001 vs W+S; ### p<0.001 vs DEHP+S. Each value represents the mean ± SEM of eight animals per group.

Discussion

In order to investigate if the NMDA receptors of glutamate are involved in the changes in the anxiety-like behavior induced by early exposure to endocrine disruptor DEHP, we compared the performance in the Elevated plus Maze of adult male rats exposed to DEHP postnatally and treated or not with MK-801, a non-competitive antagonist of glutamate receptors. Our results showed that NMDA receptor blockade by MK-801 was able to reverse anxiety-like behavior induced by exposure to DEHP during the early period of life.

As we expected, our results showed an anxiogenic effect of DEHP, which was evidenced by a significant increase in TSC and a decrease in TSO in the EPM test. These results were consistent with the findings reported in immature rats and mice exposed perinatally to DEHP (10, 30, 50, and 200 mg/kg) [17,21] as well as in young adult male rats chronically exposed to DEHP (30 mg/kg) from birth [18].

However, the mechanism underlying the enhanced anxiety-like behavior induced by DEHP is not clear. In one way DEHP may influence anxiety-like behavior by disturbing the hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal axis (HPA). In fact, exposure of male rats to DEHP leads to an age-dependent activation of the HPA ‘in vivo’ and of adrenocortical steroidogenesis ‘ex vivo’, showing a specific susceptibility of immature animals to this phthalate [22]. Perturbations of hormonal homeostasis of the HPA axis were found in adolescent female rats exposed to DEHP during lactation [23]. Direct and transgenerational effects of perinatal DEHP exposure on social behaviors and anxiety-like behavior in mice, as well as transgenerational effect of DEHP on corticosterone levels were reported by other authors [24,25]. Another way in which DEHP could influence anxiety is by altering the hypothalamic-pituitary-gonadal axis. It has been reported that gestational and lactational DEHP exposure is able to disrupt the neuroendocrine control of the gonadal axis during sexual maturation in rats [11,12]. The changes induced by DEHP in the hypothalamic concentration of GABA, the inhibitory neurotransmitter involved in the neuroendocrine control of the gonadal axis as well as in the development of anxiety, support the idea that the GABAergic system could participate in the behavioral effects of the DEHP [18]. Moreover, in the adulthood perinatal DEHP-exposed males displayed anxiogenic status, which correlate with a decrease in testosterone levels [7]. Given that the treatment with testosterone was able to reverse the disruptive effect of chronic postnatal exposure to DEHP on the testicular axis of rats, it was suggested that the antiandrogenic action of this chemical could be a probable mechanism underlying its anxiogenic effect [17]. In addition, Xu et al [21]. have suggested that the inhibition of the mitogen-activated protein kinase/extracellular signal-regulated kinases (MAPK/ERKs) activity, which mediates the non-genomic actions of testosterone in the brain cells, as well as the down-regulation of androgen receptors expression in hippocampus could be involved in the anxiogenic-like effect produced by perinatal DEHP exposure during puberty and even after in adult life.

In agreement with other authors [17,18], in the animals exposed to DEHP we did not detect changes in TE in both the open and closed arms. Considering that TE provides an approximate measure for the locomotor activity, these results could indicate that the increase in the anxiety-like behavior induced by DEHP was not influenced by probable changes in locomotor activity. Furthermore, we observed a significant increase in freezing time in DEHP-exposed rats. It is known that freezing response is a behavioral index of fear and that the deficit in testosterone may have a significant effect of increasing freezing response [26]. On this basis, we hypothesized that the increase in freezing time induced by DEHP could be due to the decrease in circulating blood testosterone levels previously found in immature and adult male rats exposed postnatally to this endocrine disruptor at the same dose used in the present work [17,18]. Therefore, it should be considered the possibility that the increase in freezing time by DEHP may be due to either direct or indirect alterations in the neuroendocrine gonadal and adrenal axes modulators, which play a critical role in the regulation of stress responses.

It is known that glutamate is the main excitatory neurotransmitter in the human Central Nervous System. A growing body of evidence suggests that glutamatergic neurotransmission may be involved in the biological mechanisms underlying stress response and anxiety-related disorders [27]. Glutamate mediates its effects via stimulation of ionotropic and metabotropic receptors [28]. During development in the rat the brain is highly sensitive to the effects of the glutamate ionotropic receptor NMDA modulation [29]. The non-competitive antagonists of glutamate receptors have been extensively studied for their anxiolytic action. In particular, in rodent models it has shown that MK-801, a non-competitive antagonist of NMDA receptors, may have anxiolytic like effects on the EPM test [30].

In the present work, we observed that MK-801-treated rats showed lower anxiety level in the EPM and increased spontaneous locomotor activity in comparison with the control group. In fact, consistent with the reported anxiolytic potential of MK-801[5,6,29] we observed that this NMDA receptor antagonist was able to produce a significant decrease in TSC as well as an important increase in TSO, suggesting that NMDA glutamate receptors are involved in the development of anxiety-like behavior. In addition, MK-801 treated animals showed a significant increase in TE, indicating that the locomotor activity can be induced by MK-801 [23].

When young adult male rats exposed to DEHP from birth were treated with the NMDA receptor antagonist, they showed an increase in TSO which was correlated with a decrease in TSC. The number of total entries in both arms of the labyrinth was increased, showing greater locomotor activity compared to animals treated only with DEHP. Freezing response in DEHP-exposed animals and treated with MK-801 was significantly lower than in the control and DEHP groups and showed no difference with the animals treated with MK-801 alone. These findings indicated that MK-801 was able to reverse the anxiogenic action of DEHP, leading the freezing time to values even lower than those observed in the control group.

However, it is difficult to explain the probable mechanisms that could mediate the anxiogenic effect of DEHP through an interaction with NMDA glutamate receptors. It has been reported that blockade of NMDA receptors causes a reduction of neuronal activity in pathways that lead to the release of GABA or monoamines, which themselves have been implicated in anxiety-related processes [8]. In this sense, we demonstrated the participation of the GABAergic system in the anxiety-like behavior induced by chronic postnatal exposure to DEHP in young adult male rats [17]. On the other hand, androgens modulate the structure and functions of the hippocampus related with behavior and exert profound effects on the up-regulation of NMDA receptors in hippocampus of males. DEHP markedly down-regulates the expression of androgen receptors which, in turn, are involved in the regulation of behavior mediated by the hippocampus of pubertal males. Therefore, it may be possible that chronic exposure to DEHP during critical periods of neurodevelopment is capable of inducing anxiogenic behavior in adult male rats, decreasing androgen levels and the expression of their receptors as well as interacting with NMDA glutamate receptors.

In conclusion, our results suggest: 1) NMDA receptor blockade by MK-801 can reverse anxiety-like behavior induced by exposure to DEHP during the early period of life. 2) The glutamatergic system is involved in the anxiogenic effect of phthalate, which is probably triggered by its known antiandrogenic action.

Highlights

- Chronic postnatal exposure to DHEP induces anxiogenic effect in adult male rats

- MK-801 reverses anxiety-like behavior induced by chronic postnatal exposure to DEHP

- The glutamatergic system is involved in the anxiogenic effect of phthalate

Funding

The author(s) disclosed receipt of the following financial support for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article: This work was supported by the Universidad Buenos Aires under grants UBACYT20020130100439BA (OJP) and UBACYT 20020170100151BA (RAC and SC).

References

- Pryce C, Mohammed A, Feldon J (2002) Environmental manipulations in rodents and primates: insights into pharmacology, biochemistry and behaviour. Pharmacol Biochem Behav 73: 1–5.

- Nemeth H, Varga H, Farkas T, et al. (2002) Long-term effects of neonatal MK-801 treatment on spatial learning and cortical plasticity in adult rats. Psychopharmacology 160: 1–8.

- Latysheva NV and Rayevsky KS (2003) Chronic neonatal N-Methyl-D-Aspartate receptor blockade induces learning deficits and transient hypoactivity in young rats. Prog Neuro- Psychopharmacol Biol Psychiatry 27: 787–794.

- Sharma AC and Kulkarni SK (1993) Evidence for benzodiazepine receptor interaction with MK-801 in anxiety related behaviour in rats. Indian J Exp Biol 31: 191–193.

- Poleszak E, Wlaz P, Wróbel A, et al. (2008) NMDA/glutamate mechanism of magnesium induced anxiolytic like behavior in mice. Pharmacol Rep 60: 655–663.

- Kocahan S, Akillioglu K, Binokay S, et al. (2013) the effects of N-Methyl-D-Aspartate receptor blockade during the early neurodevelopmental period on emotional behaviors and cognitive functions of adolescent Wistar rats. Neurochem Res 38: 989–96.

- Pınar N, Akillioglu K, Sefil F, et al. (2015) Effect of clozapine on locomotor activity and anxiety-related behavior in the neonatal mice administered MK-801. Bosn J Basic Med Sci 15: 74–9.

- Fraser CM, Fisher A, Cooke MJ, et al (1997) The involvement of adenosine receptors in the effect of dizocilpine on mice in the elevated plus-maze. Eur Neuropsychopharmacol 7: 267–273.

- Rowdhwal SS and Chen J (2018) Toxic Effects of Di-2-ethylhexyl Phthalate: An Overview. Biomed Res Int Article ID 1750368, 10.

- 10.Lin H, Yuan K, Li L, et al. (2015) In Utero Exposure to Diethylhexyl Phthalate Affects Rat Brain Development: A Behavioral and Genomic Approach. Int J Environ Res Public Health 12: 13696–710.

- Carbone S, Szwarcfarb B, Ponzo O, et al. (2010) Impact of gestational and lactational phthalate exposure on hypothalamic content of amino acid neurotransmitters and FSH secretion in peripubertal male rats. Neurotoxicology 31: 747–751.

- Carbone S, Samaniego YA, Cutrera R, et al. (2012) Different effects by sex on hypothalamic-pituitary axis of prepubertal offspring rats produced by in utero and lactational exposure to di-(2-ethylhexyl) phthalate (DEHP). Neurotoxicology 33: 78–84.

- Liang T, Ouyang J, Yi L, et al. (2013) Behavioral changes of rats after short-term exposure to di-(2-ethyl hexyl) phthalate. J South Med Univ 33: 401–405.

- Park S, Cheong JH, Cho SC, et al. (2015) Di-(2-Ethylhexyl) phthalate exposure is negatively correlated with trait anxiety in girls but not with trait anxiety in boys or anxiety-like behavior in male mice. J Child Neurol 30: 48–52.

- Quinnies KM, Doyle TJ, Kim KH, et al. (2015) Transgenerational effects of di-(2-ethylhexyl) phthalate (DEHP) on stress hormones and behavior. Endocrinology 156: 3077–3083.

- Wang R, Xu X, Weng H, et al. (2016) Effects of early pubertal exposure to di-(2-ethylhexyl) phthalate on social behavior of mice. Horm Behav 80: 117–124.

- Carbone S, Ponzo OJ, Gobetto N, et al. (2013) Antiandrogenic effect of perinatal exposure to the endocrine disruptor di-(2-ethylhexyl) phthalate increases anxiety-like behavior in male rats during sexual maturation. Horm Behav 63: 692–69.

- Carbone S, Ponzo OJ, Gobetto N, et al. (2018) Effect of di(2-ethylhexyl) phthalate on the neuroendocrine regulation of reproduction in adult male rats and its relationship to anxiogenic behavior: Participation of GABAergic system. Human and Experimental Toxicology 38: 25–35.

- Wozniak DF, Olney JW, Kettinger L et al. (1990) Behavioral effects of MK-801 in the rat. Psychopharmacology (Berl) 101: 47–56.

- Walfi AA and Frye ChA (2007) The use of the elevated plus maze as an assay of anxiety-related behavior in rodents. Nat Protoc 2: 323–328.

- Xu X, Yang Y, Wang R, et al. (2015) Perinatal exposure to di-(2-ethylhexyl) phthalate affects anxiety- and depression-like behaviors in mice. Chemosphere 124: 22–31.

- Supornsilchai V, Söder O, Svechnikov K (2007) Stimulation of the pituitary-adrenal axis and of adrenocortical steroidogenesis ex vivo by administration of di-2-ethylhexyl phthalate to prepubertal male rats. J Endocrinol 192: 33–9.

- Wang DC, Chen TJ, Lin ML, et al. (2014) Exercise prevents the increased anxiety-like behavior in lactational di-(2-ethylhexyl) phthalate-exposed female rats in late adolescence by improving the regulation of hypothalamus-pituitary-adrenal axis. Horm Behav 66: 674–84.

- Quinnies KM, Harris EP, Snyder RW, et al. (2017) Direct and transgenerational effects of low doses of perinatal di-(2-ethylhexyl) phthalate (DEHP) on social behaviors in mice. PLoS One 12: 0171977.

- Quinnies KM, Doyle TJ, Kim KH, et al. (2015) Transgenerational Effects of Di-(2-Ethylhexyl) Phthalate (DEHP) on Stress Hormones and Behavior. Endocrinology 156: 3077–83.

- King JA, De Oliveira WL, Patel N (2005) Deficits in testosterone facilitate enhanced fear response. Psychoneuroendocrinology 30: 333–40.

- Riaza Bermudo-Soriano C, Perez-Rodriguez MM, Vaquero-Lorenzo C, et al. (2012) New perspectives in glutamate and anxiety. Pharmacol Biochem Behav 100: 752–74.

- Kew JN, Kemp JA (2005) Ionotropic and metabotropic glutamate receptor structure and pharmacology. Psychopharmacology (Berl) 179: 4–29.

- Haberny KA, Paule MG, Scallet AC, et al. (2002) Ontogeny of the N-methyl-D aspartate (NMDA) receptor system and susceptibility to neurotoxicity. Toxicol Sci 68: 9–17.

- Kocahan S, Akillioglu K (2013) Effects of NMDA receptor blockade during the early development period on the retest performance of adult Wistar rats in the elevated plus maze. Neurochem Res 38: 1496–500.