Abstract

This case series describes the hepatic arterial communicating arcades and their importance in the endovascular management of hepatic artery pseudoaneurysm, paediatric post liver transplant lobar arterial occlusion and lobar arterial stenosis due to gall bladder carcinoma. We describe different types of arterial communicating arcades which have not been described earlier.

Keywords

Arterial communicating arcades, hepatic artery, pseudoaneurysm, liver transplantation, embolization, gall bladder carcinoma.

Introduction

Interlobar arterial communication or Communicating Arcades (CA) in the hepatic hilum has been recognized as one of the most important collateral pathways to the liver. CAs plays an important role in the blood supply to the caudate lobe and also have a close relationship with the blood supply to the hilar biliary tract. Hepatic arterial communicating arcades develop in hilum when either right or left hepatic artery is occluded or significantly stenosed [1,2]. If Proper Hepatic Artery (PHA) is occluded, liver perfusion can occur through small collaterals in the hepatic ligaments, collaterals around the common bile duct, inferior phrenic artery, pancreatico-duodenal artery and intercalary ‘de novo’ collaterals [3,4]. We describe 3 cases showing the importance of hepatic arterial CA in endovascular treatment of mycotic Hepatic Artery Pseudoaneurysms (HAPAs), lobar arterial stenosis following paediatric deceased donor liver transplant and locally advanced carcinoma gallbladder infiltrating the Right Hepatic Artery (RHA).

Case Series

Case 1

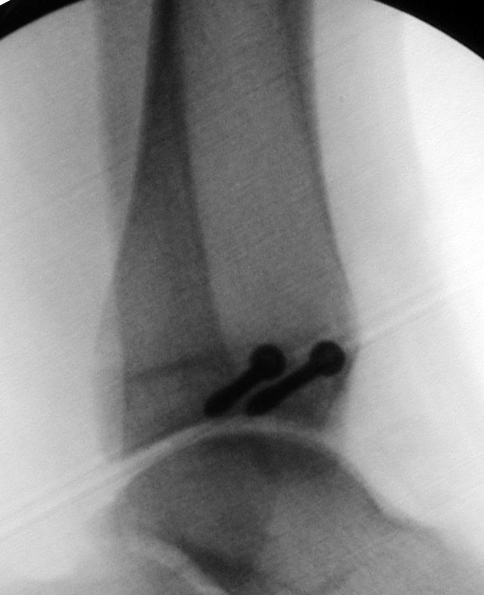

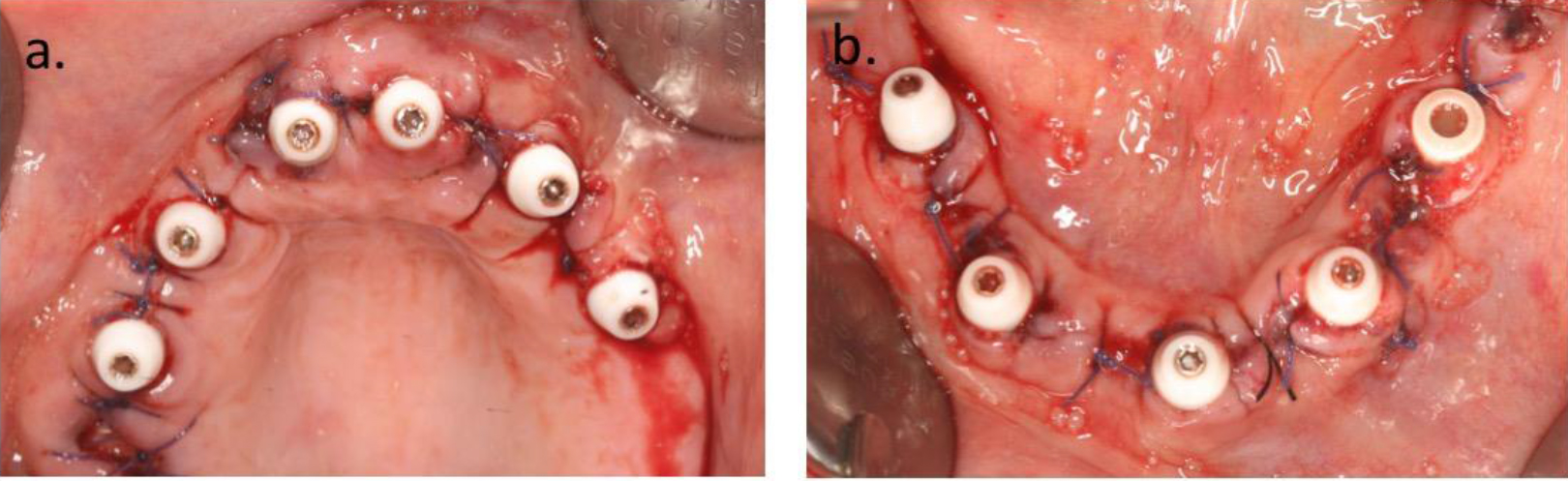

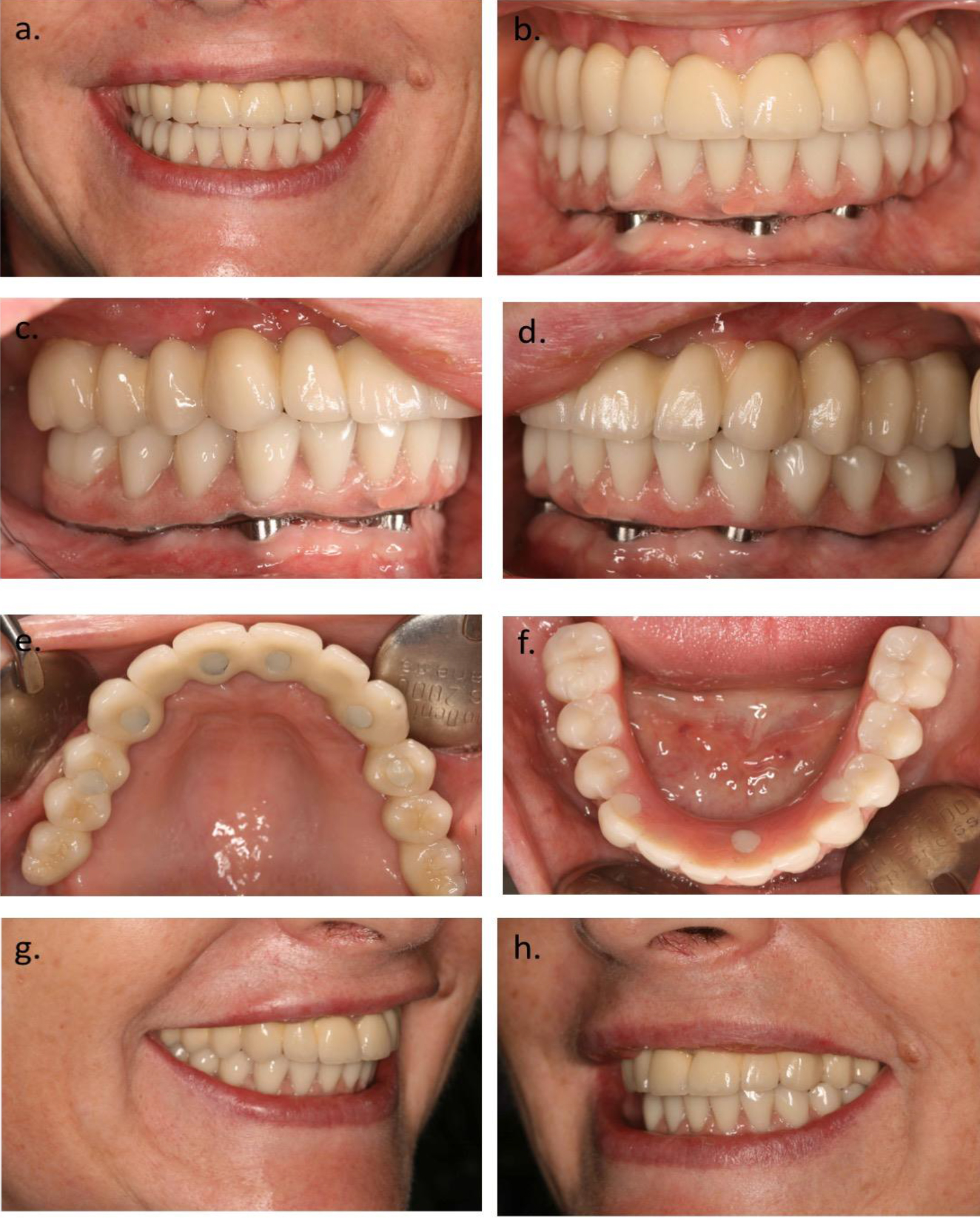

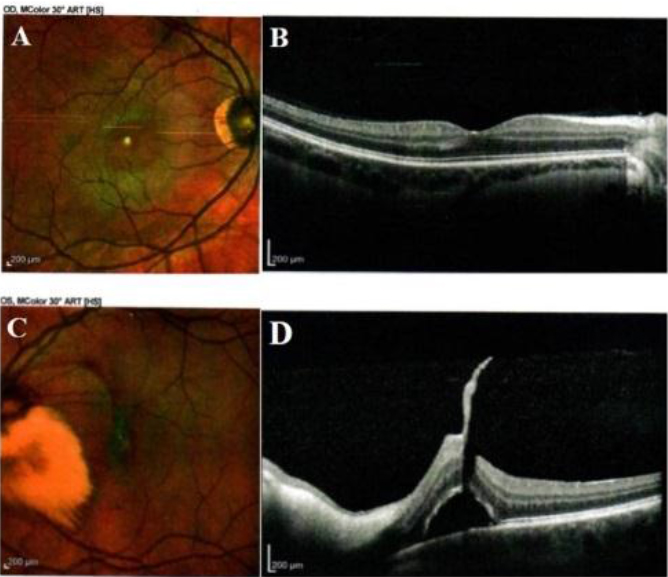

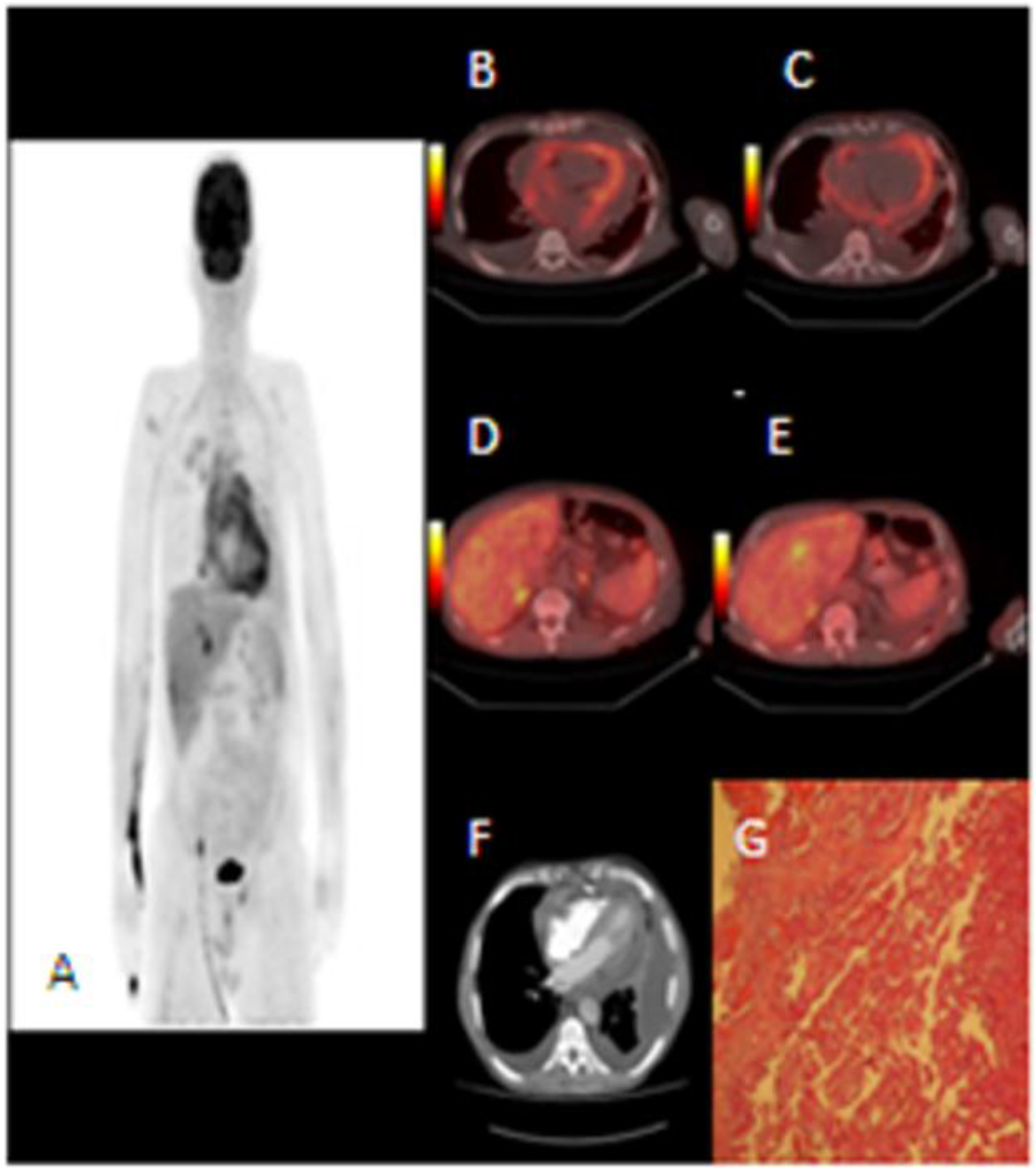

49 year old lady presented with cholelithiasis and choledo-cholithiasis. After multiple failed attempts of endoscopic management, the patient underwent a Roux-en-Y hepaticojejunostomy. On post-operative day 5, the patient had low grade fever and elevated white cell count (13,000/mm3). Ultrasound examination revealed a small collection anterior to the hepaticojejunostomy site. No biliary dilatation was seen. A contrast enhanced CT (CECT) scan was performed which revealed two extra hepatic pseudoaneurysms in the RHA proximal to its bifurcation (Figure 1a). Interventional radiologist was unavailable on that particular week. Drain was placed by diagnostic radiologist avoiding injury to pseudoaneurysms at least to drain the collection. Initially, bile stained fluid was drained, which was followed by drainage of frank blood through the drain tube and hemodynamic instability of the patient. Immediately patient was resuscitated and taken to angiosuite for embolization. In view of the emergency situation, the in house cardiologists performed the embolization. CHA angiogram confirmed the presence of two irregularly filling extra hepatic RHA pseudoaneurysms. A single coil was placed in the right hepatic artery proximal to the pseudoaneurysms. Post coiling, RHA went in to spasm and no reperfusion of pseudoaneurysm was observed (figure 1b). However, on proper hepatic artery angiogram collateral supply from Middle Hepatic Artery (MHA) to distal RHA branches was observed (Figure 1c). No reperfusion of pseudoaneurysms was observed post coiling, and the procedure was concluded. Post procedure CECT scan done after two days did not reveal reperfusion of pseudoaneurysms, however distal migration of coil in in RHA was noted (Figure 1d). Post embolization, liver enzymes and bilirubin were elevated (AST, ALT and ALP were 1352, 1454 and 584 respectively, bilirubin was 2.3 mg/dl) on day 1 and become near normal on day 7. Patient was discharged on 12thpost embolization day. On 17th post embolization day, the patient suddenly collapsed at home. She was found to be hypotensive and resuscitated at a local hospital before being shifted back to our hospital for management. Reperfusion of pseudoaneurysms and mild hemoperitoneum was observed on repeat CECT scan (Figure 1e). Angioembolization was performed by an interventional radiologist. Selective RHA angiogram was performed (Figure 1f) and pseudoaneurysms were delineated. During embolization, attempt was not made to cross the pseudoaneurysms in view of coil migration and rupture of aneurysms. RHA was embolized with multiple 6mm, 8mm 0.018” micro coils. Middle hepatic artery (MHA) was arising from proximal GDA. MHA angiogram showed faint perfusion of pseudoaneurysms through intrahepatic arterial arcades (Figure 1g). Intrahepatic arterial arcades were embolized with gelfaom particles and main trunk of MHA was embolized with 5mm 0.018” coils (Figure 1h). Left hepatic artery (LHA) angiogram did not reveal perfusion of pseudoaneurysms, however few tiny CA were seen supplying the segment 4 of liver. Post embolization, the patient recovered well. No significant increase in liver enzymes or bilirubin was noted. No recurrence of pseudoaneurysm or other symptoms were observed on 12 months follow up.

Figure 1. 49 year old female patient, post hepaticojejunostomy presented with prehepatic collection, fever and elevated total white cell count on day 5. Case describes CAs from both middle and left hepatic arteries. (a) Arterial phase contrast enhanced CT scan, oblique coronal MIP image showing two small mycotic pseudoaneurysms in (white arrow) right hepatic artery. Small biliary collection was also noted. (b and c) Celiac angiography digital image post embolization of right hepatic artery (by cardiologist because of non-availability of Interventional radiologist) showing single coil (black arrow) in RHA with non opacification of pseudoaneurysms and intrahepatic arterial arcades communicating between right and accessory RHA (Black arrows). Pigtail catheter placed in view to drain the collection caused rupture of pseudoaneurysm. (d) Arterial phase contrast enhanced CT scan done post embolization day 2 revealed thrombosed pseudoaneurysm and distally migrated crumpled coil (arrow) near RHA bifurcation. Arrow head shows HepJ anastomotic bowel staple suture (e) Arterial phase contrast enhanced CT scan done post embolization on post op day 17, MIP image shows reperfusion of pseudoaneurysms (arrows) with increase in size of postero-medial pseudoaneurysm. (f) Digital right hepatic artery angiogram showing migrated coil and two pseudoaneurysms (arrow). (g) Post RHA coiling digital angiogram of MHA showing multiple intrahepatic arterial arcades (small black arrows) feeding distal right hepatic artery. (h) Post MHA coiling, celiac axis digital angiogram showing patent left HA (black arrow) and GDA.

Case 2

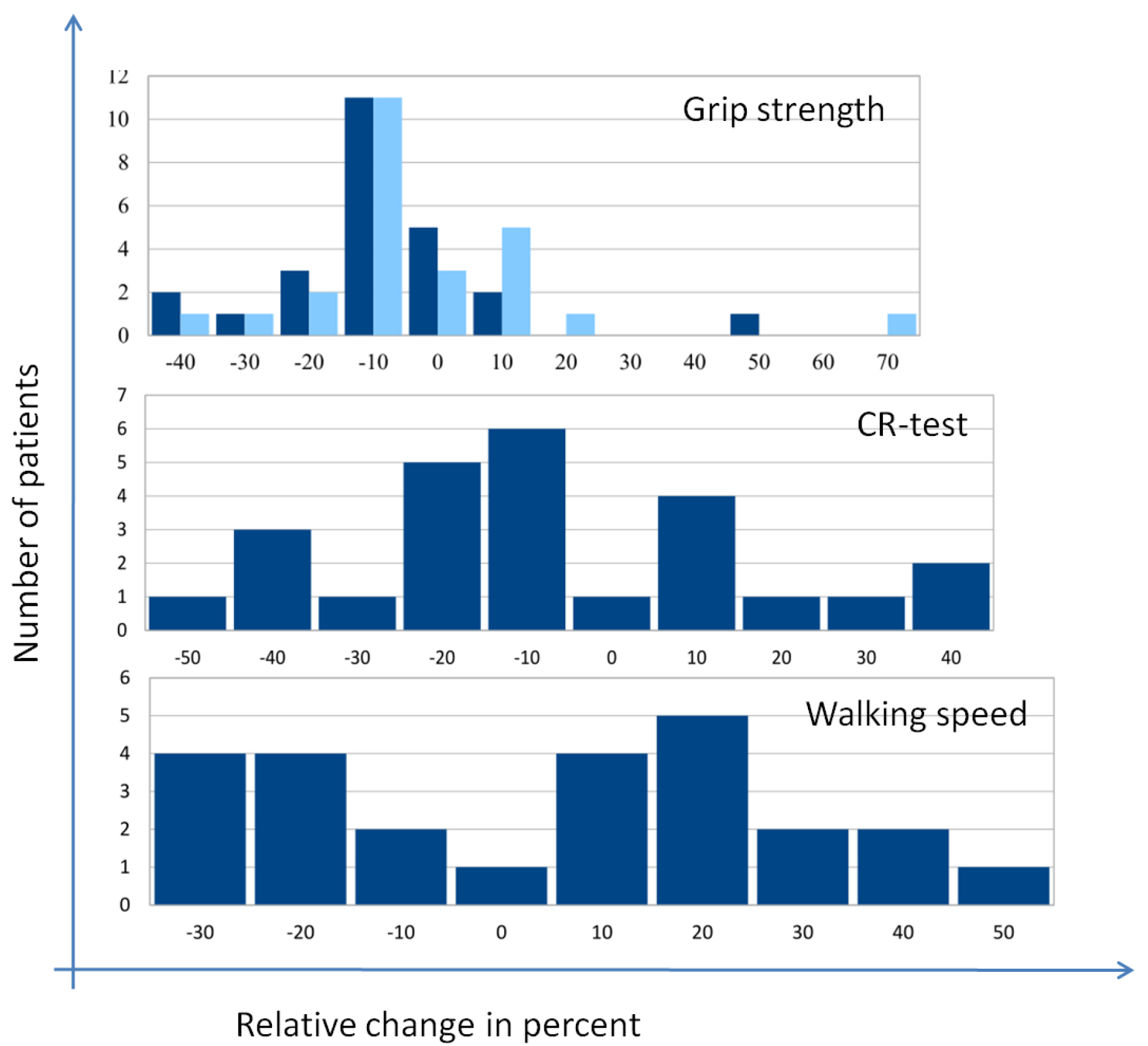

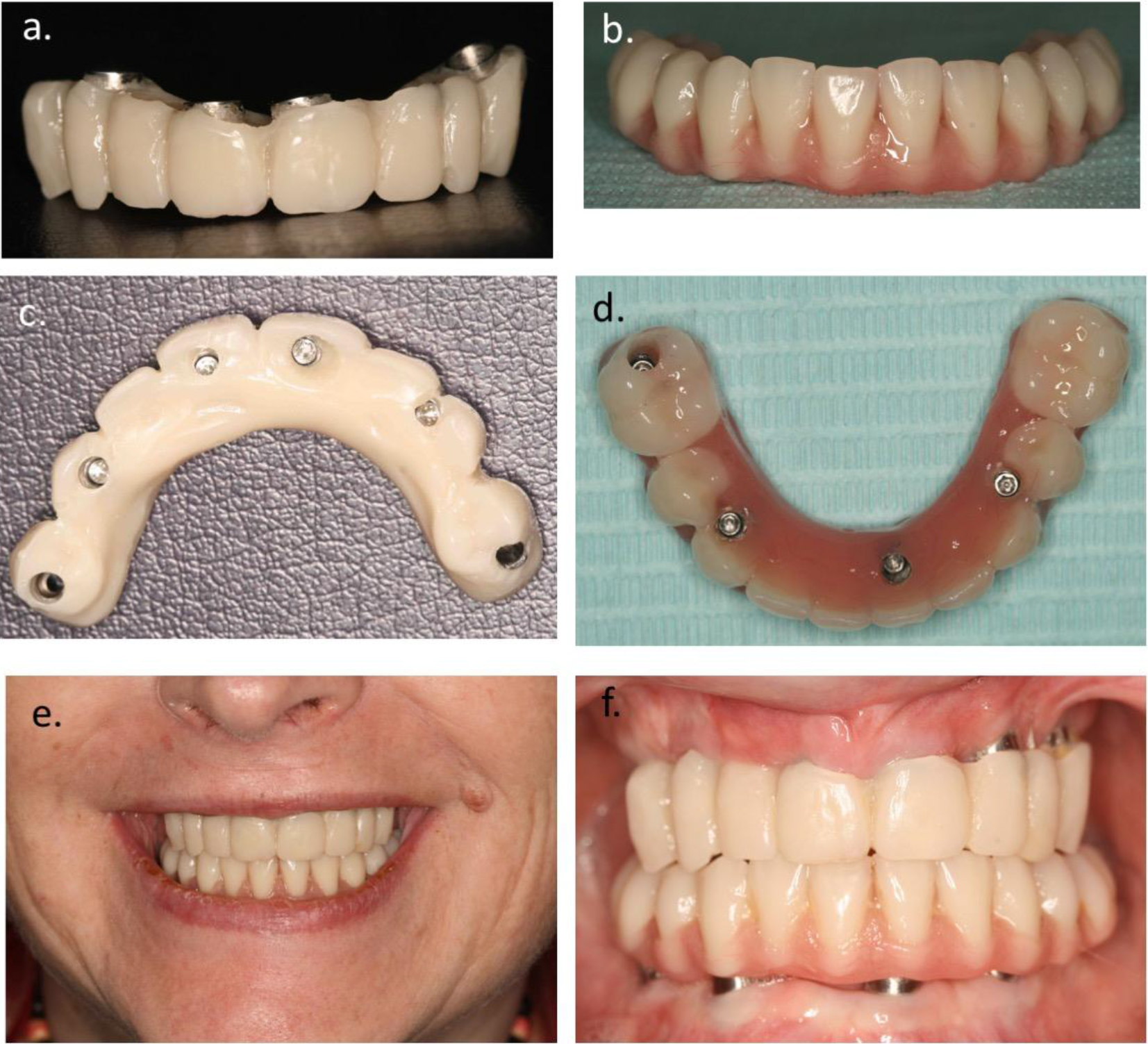

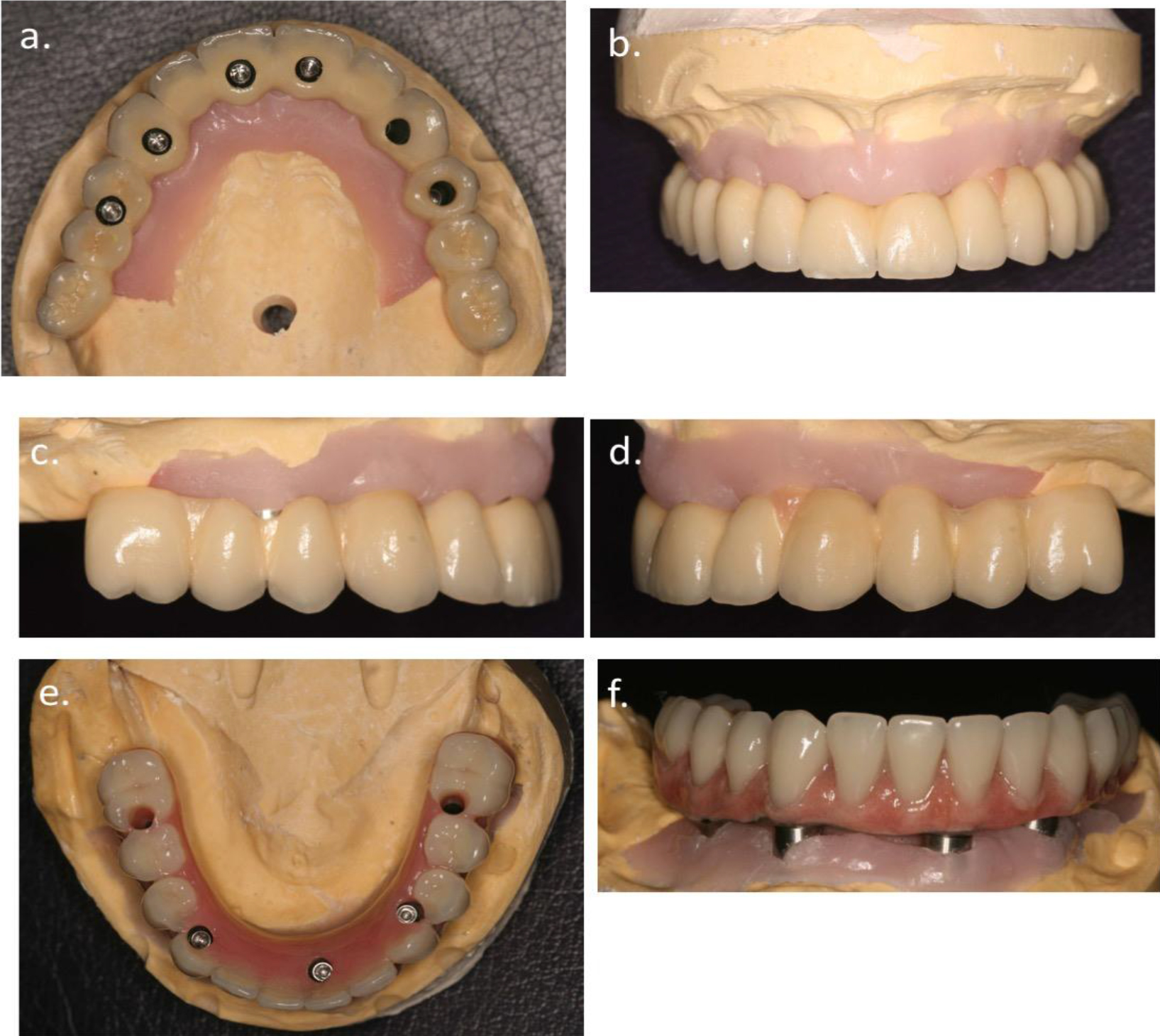

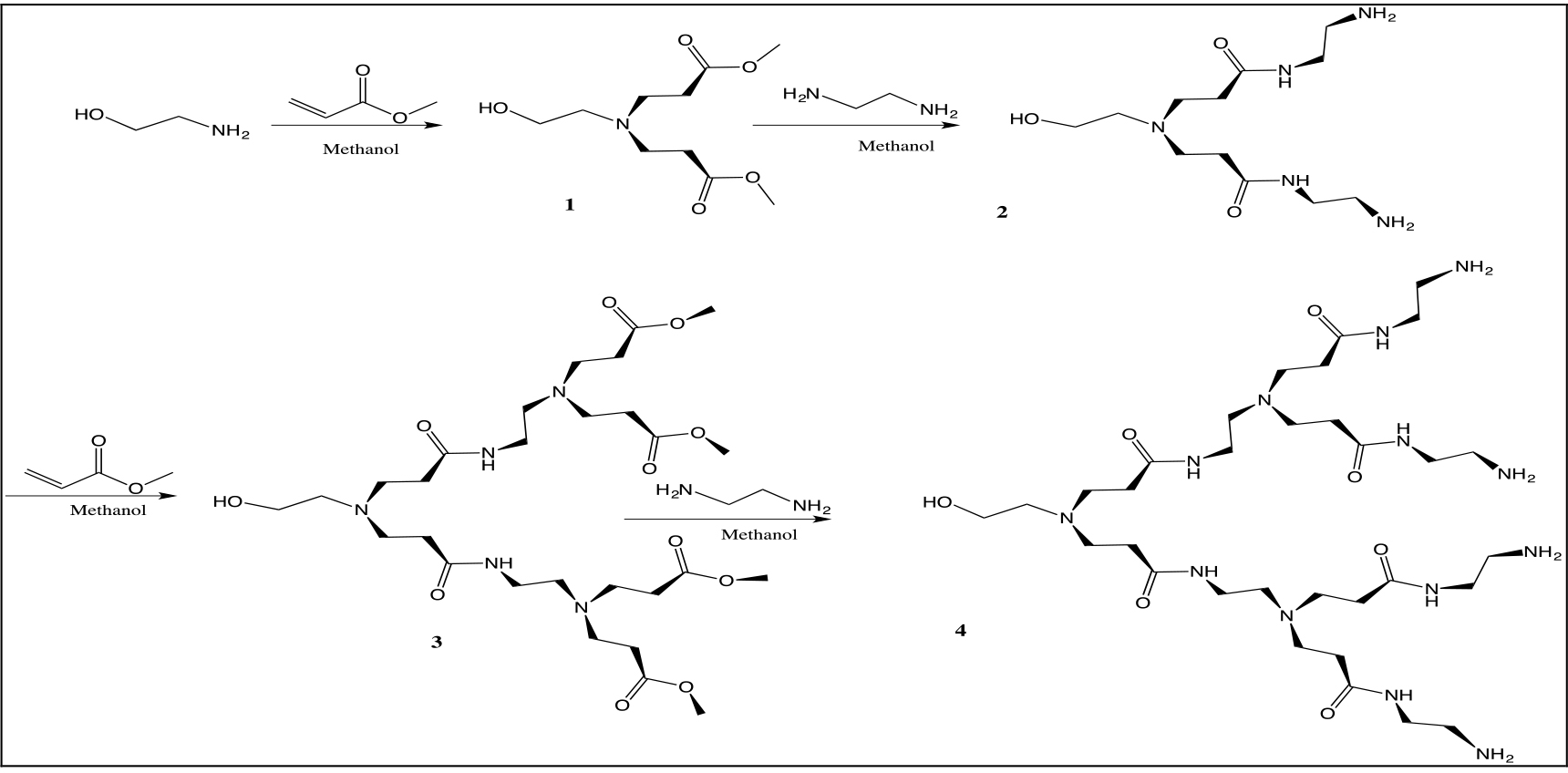

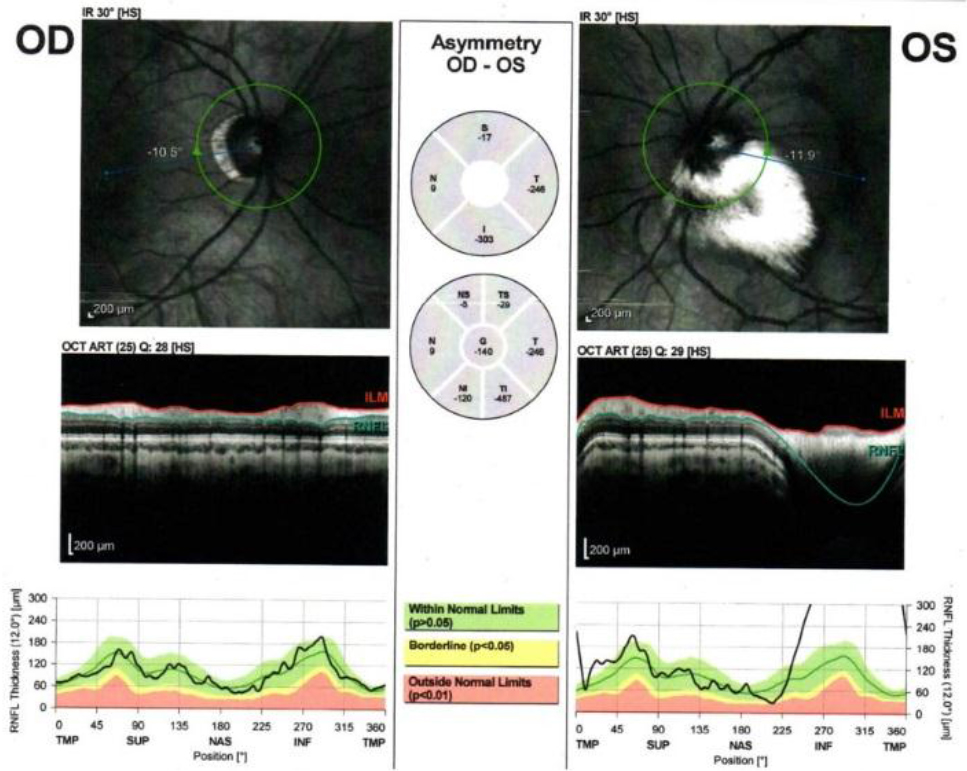

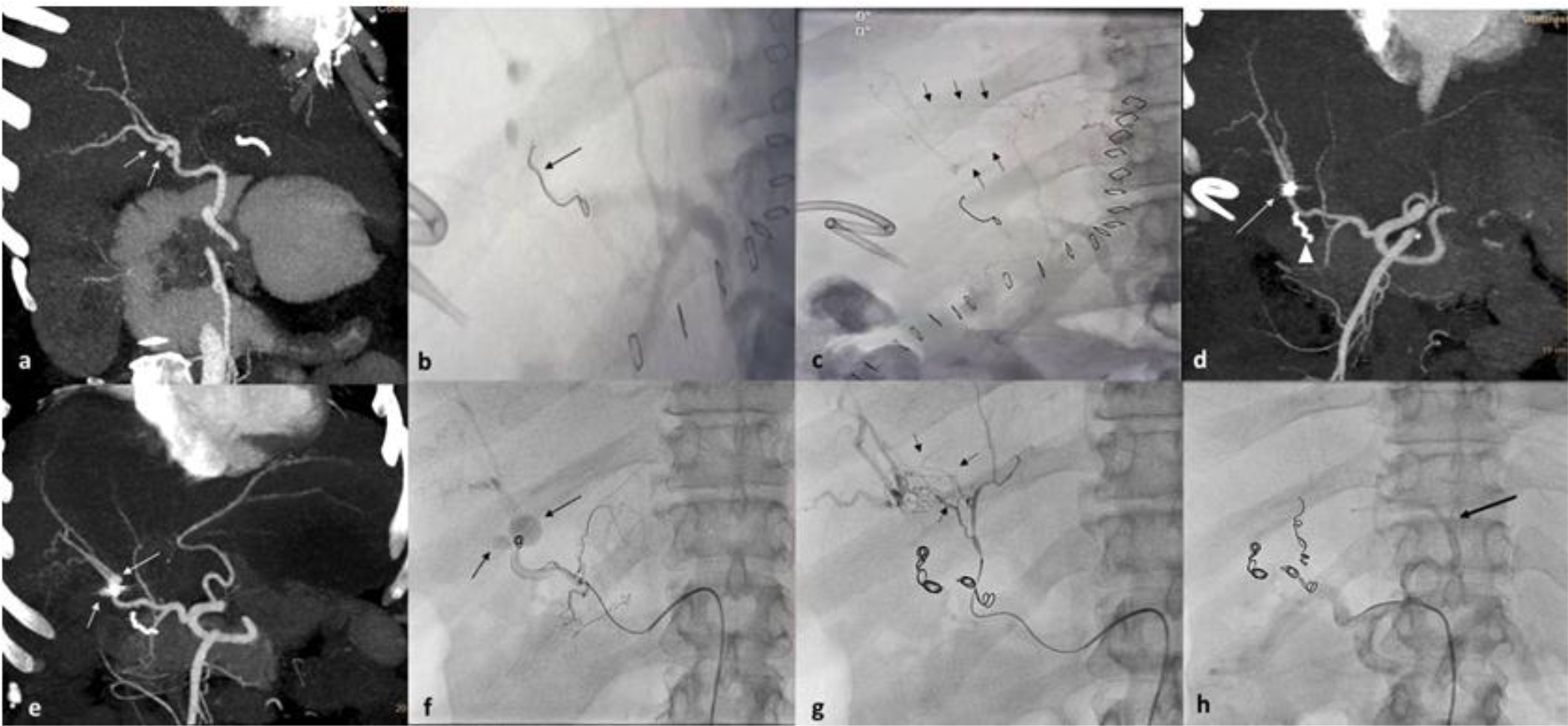

A 9 year old male patient, a known case of Alagille syndrome had undergone Deceased Donor Liver Transplantation (DDLT). During transplant two arterial anastomosis were performed. Right and left hepatic arteries of donor were anastomosed to recipient’s PHA. Intraoperative colour and spectral doppler ultrasound didn’t reveal any significant abnormality in Peak Systolic Velocity (PSV), Resistive Index (RI) and spectral waveform of intrahepatic portions of right, segment 4 and left hepatic arteries. From 2nd post-operative day, ultrasound revealed multiple subcapsular ischemic areas in right lobe of liver and increasing post anastomotic (choledocho-choledochostomy) biliary dilatation. Colour and spectral doppler ultrasound revealed low RI (0.523 in RHA and 0.429 in segment 4 artery) and normal PSV in intraparenchymal portions of both right and left hepatic arteries (Figure2a, b & c). Marginal alterations in liver enzymes were observed with normal INR and serum lactate levels. In view of isolated right lobe subcapsular ischemic areas and biliary dilatation, CECT scan was performed. CECT scan showed, short segment complete stenosis of anastomotic and post anastomotic RHA and reperfusion of distal parenchymal arteries through CA from segment 4 artery. Segment 4 artery and LHA were enhancing normally. Multiple non enhancing subcapsular ischemic areas were seen in right lobe. No focal abnormality seen in left lobe of liver. Mild biliary dilatation was seen (Figure 2d, e and f). ERCP and plastic biliary stent was placed to assist biliary drainage. Routine interval ultrasound follow was done till discharge. The patient is doing well 10months after the transplant.

Figure 2. 8 year old male patient, post liver transplant status with mild elevated liver enzymes. (a & b) Spectral Doppler imaging of right and segment 4 hepatic arteries showing elevated peak systolic velocity with low RI. (c) Gray scale and colour Doppler ultrasound image dual window showing biliary dilatation black arrow) with narrowing at anastamotic site. (d & e) Arterial phase contrast enhanced CT scan coronal MIP image showing post anastomotic unopacified proximal right hepatic artery (arrow heads). Coronal and axial MIP image showing intrahepatic arterial arcades (small white arrows) communicating between segment 4 artery and right hepatic artery. (f) Venous phase CECT axial images showing multiple non enhancing subcapsular hypodense areas in right lobe (open arrows) and predominant central biliary dilatation.

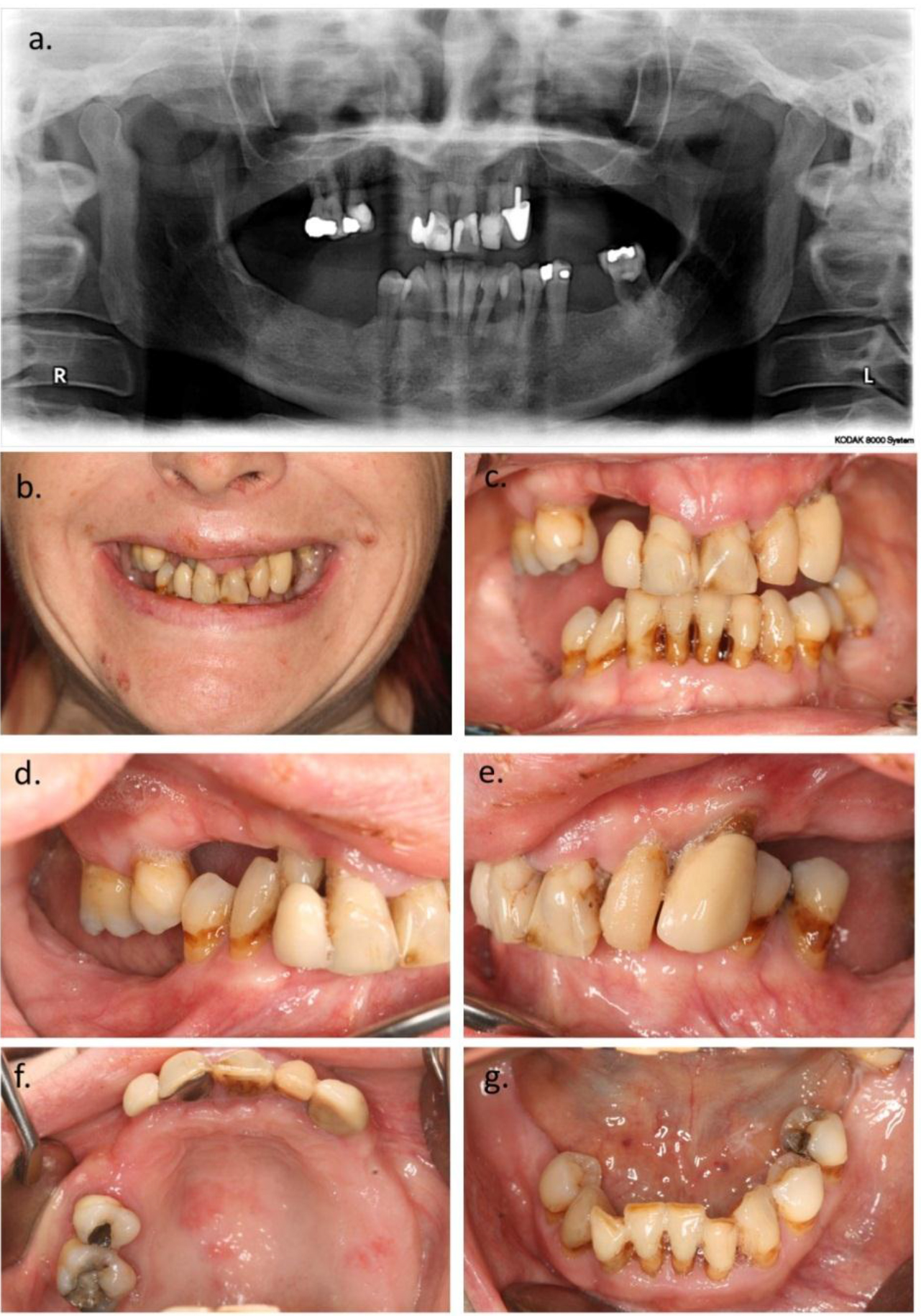

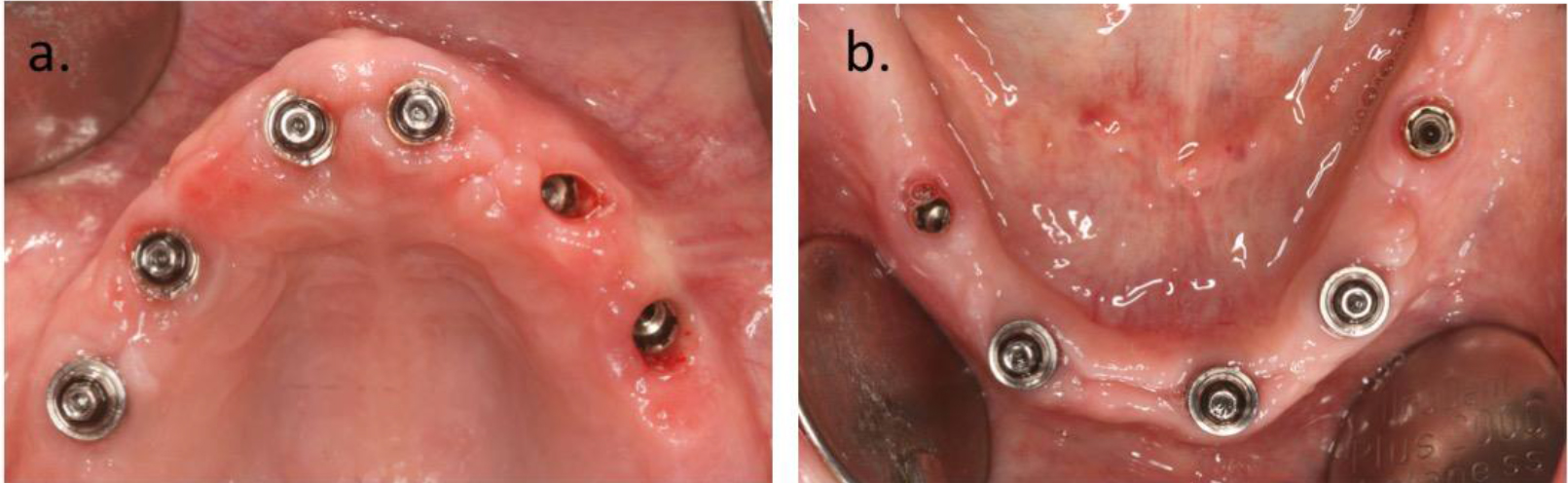

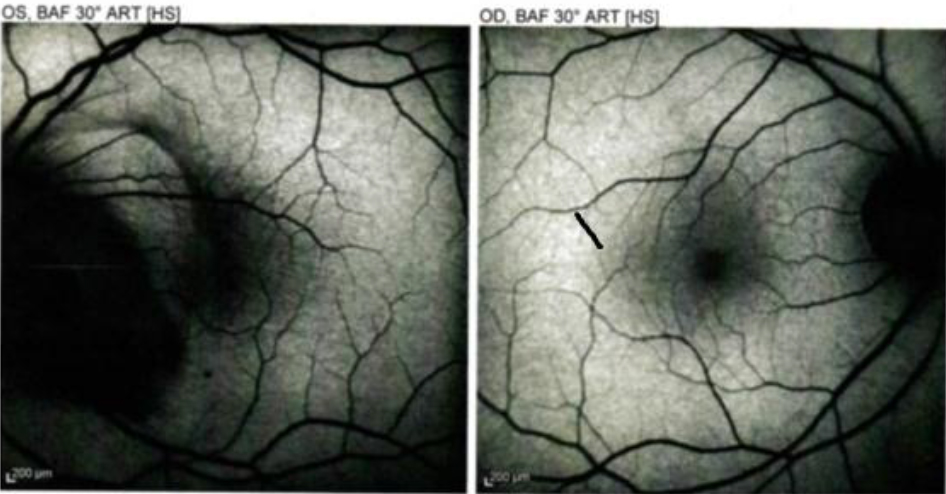

Case 3

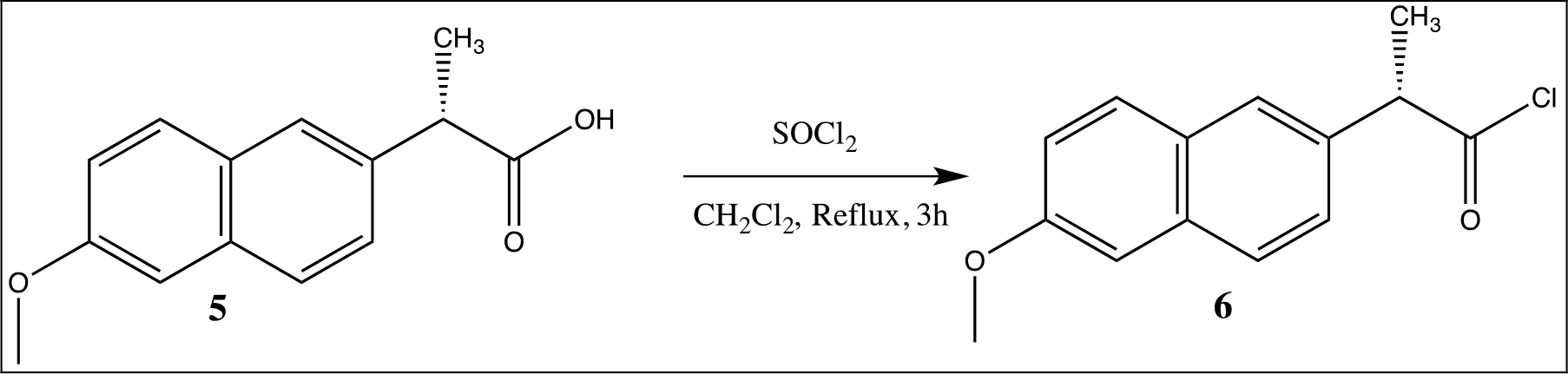

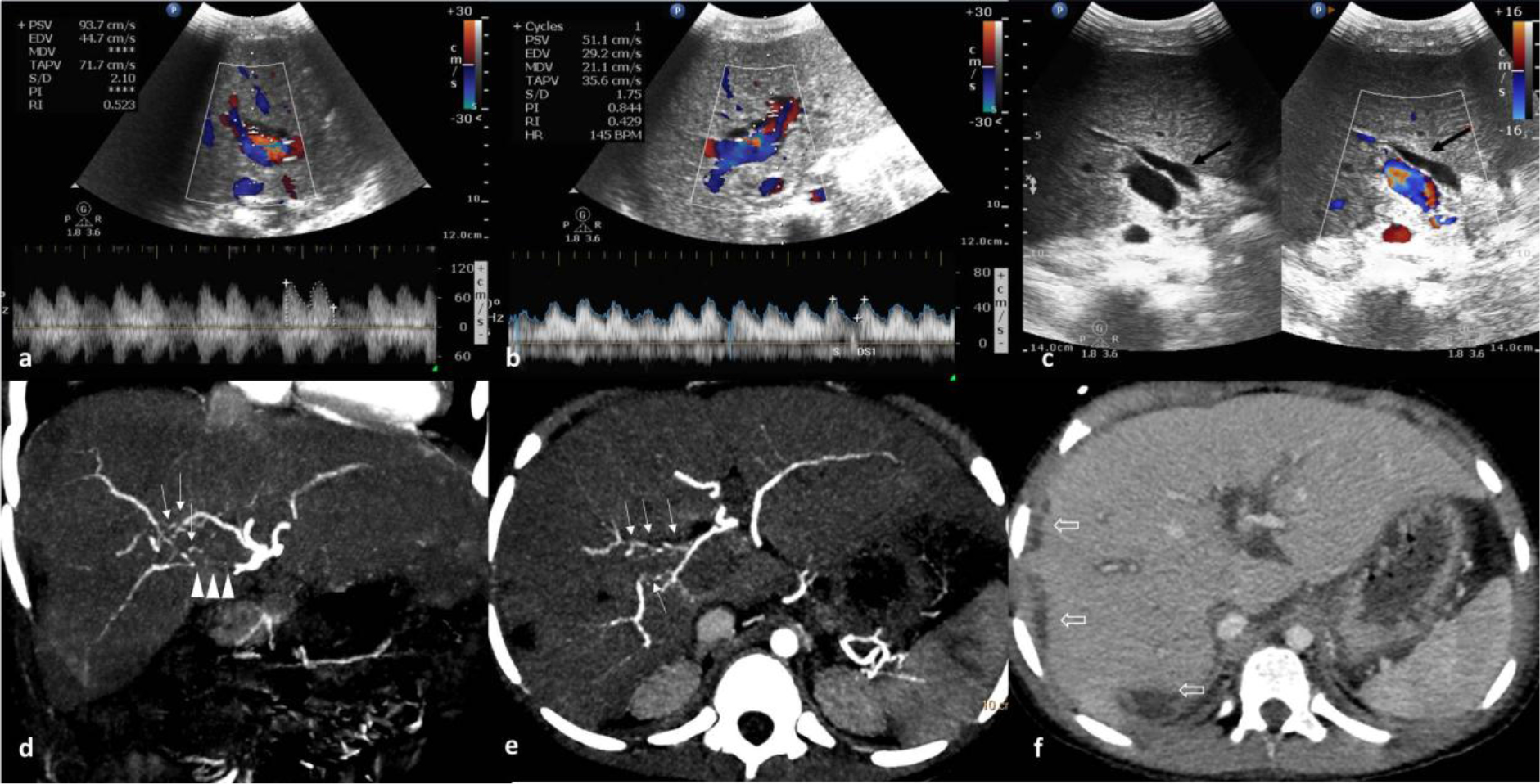

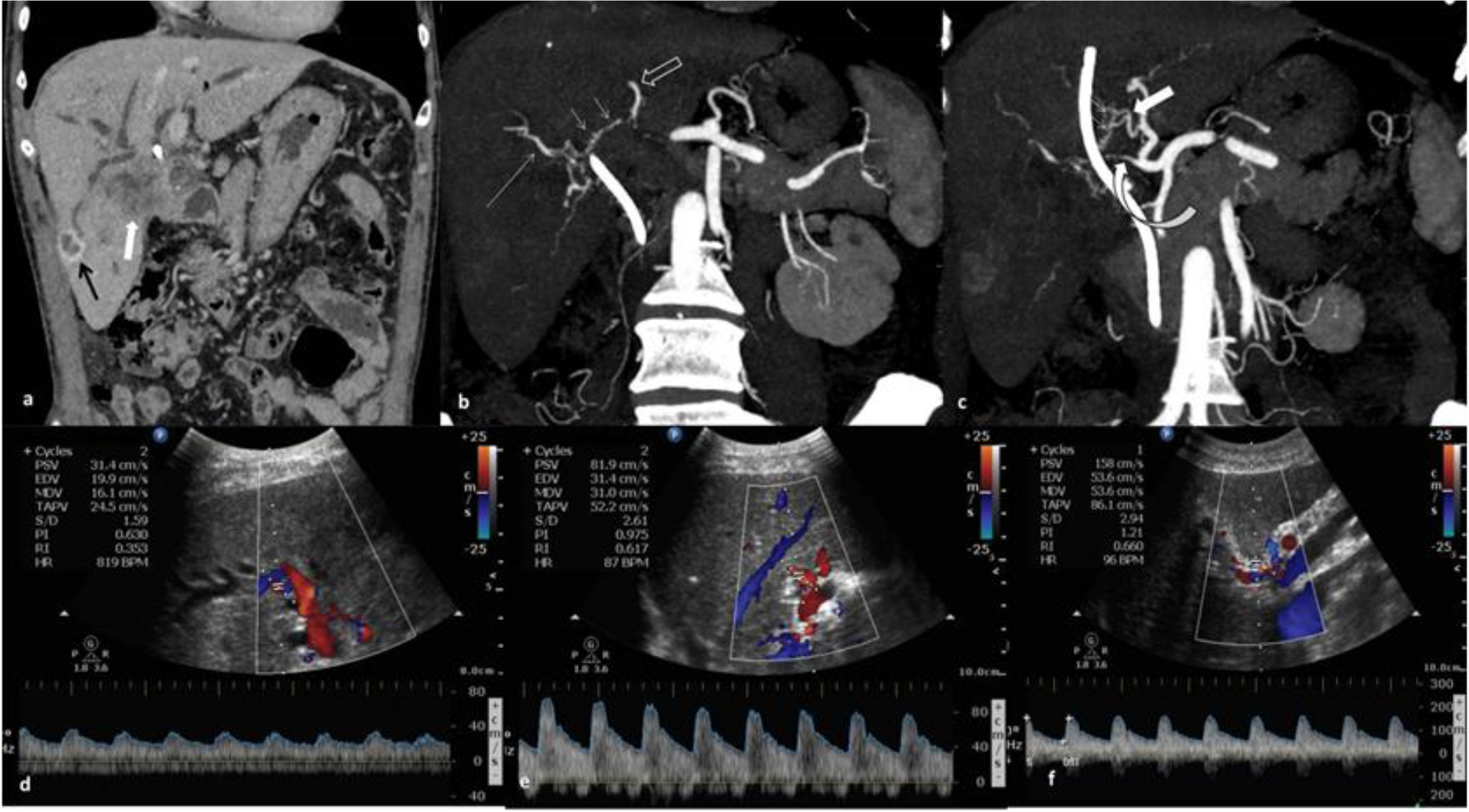

A 64 year old male presented with progressive jaundice of 3 months duration. Total bilirubin was 13mg/dL. Transabdominal ultrasound revealed Gall Bladder (GB) fossa mass with infiltration of adjacent liver and few hypoechoic lesions seen in right lobe of liver. Hilar biliary confluence was involved with significant dilatation of intra hepatic biliary radicles. Through ERCP, plastic biliary stent was placed in to left side biliary ducts. Total bilirubin level came down to 3.5mg/dL in 3 days. The CECT scan revealed a large enhancing mass in GB fossa with infiltration of adjacent liver. Few peripherally enhancing focal lesions were seen in right lobe of liver (Figure 3a). Tumour was seen encasing the proximal RHA with its significant stenosis. Reperfusion of Intraparenchymal RHA branches were observed through arterial CAs from left hepatic artery both from segment 2/3 and segment 4 hepatic arteries (Figure 3b and c). Portal vein was not involved. Tumour was invading the biliary confluence with significant bilateral intra hepatic biliary dilatation. Plastic biliary stent was seen in left lobe biliary duct. Adenocarcinoma of gall bladder was confirmed on percutaneous biopsy of GB fossa mass. Biopsy of right lobe liver lesions revealed cholangitic abscess. The patient was informed about the prognosis and two self-expandable metallic stents were placed.

Figure 3. 64 year old male patient, inoperable case of GB fossa mass, presented with progressive jaundice and abdominal pain since 3months. Case describes CAs from both the branches of left hepatic artery (segment 4 artery and segment 2/3 branches). (a) Venous phase CT scan, coronal image showing ill-defined enhancing mass in segment 5 and GB fossa. Rim enhancing lesion in segment VI. (b & c) Arterial phase contrast enhanced CT scan, coronal MIP images showing arterial arcades (small arrows) communicating between LHA (open white arrow) and RHA (Long arrow) and segment 4 artery (thick arrow) and RHA respectively. Significant stenosis of proximal RHA seen (curved arrow). (d & e) Spectral Doppler images showing normal velocity and low RI in intrahepatic branches of RHA and high velocity and normal RI in segment IV artery. (f) Spectral Doppler performed at stenotic proximal RHA showing increased peak systolic velocity (158cm/sec) with normal RI.

Discussion

Inter lobar hepatic arterial communications or Communicating Arcades (CAs) develop depending on the site of stenosis or occlusion of the hepatic artery. Interlobar collateral vessels usually develop in the hepatic hilum in patients with interruption either right or left hepatic artery. These vessels are not visualized on angiograms in patients with intact hepatic arterial supply [5].

The CAs is located extrahepatically in the hepatic hilum or cranial to the portal bifurcation close to the hilar bile duct. Caudate lobe is believed to derive its blood supply not only from the segment I artery but also from the CA, because of which transarterial chemoembolization for caudate lobe hepatocellular carcinoma is not very effective [1].

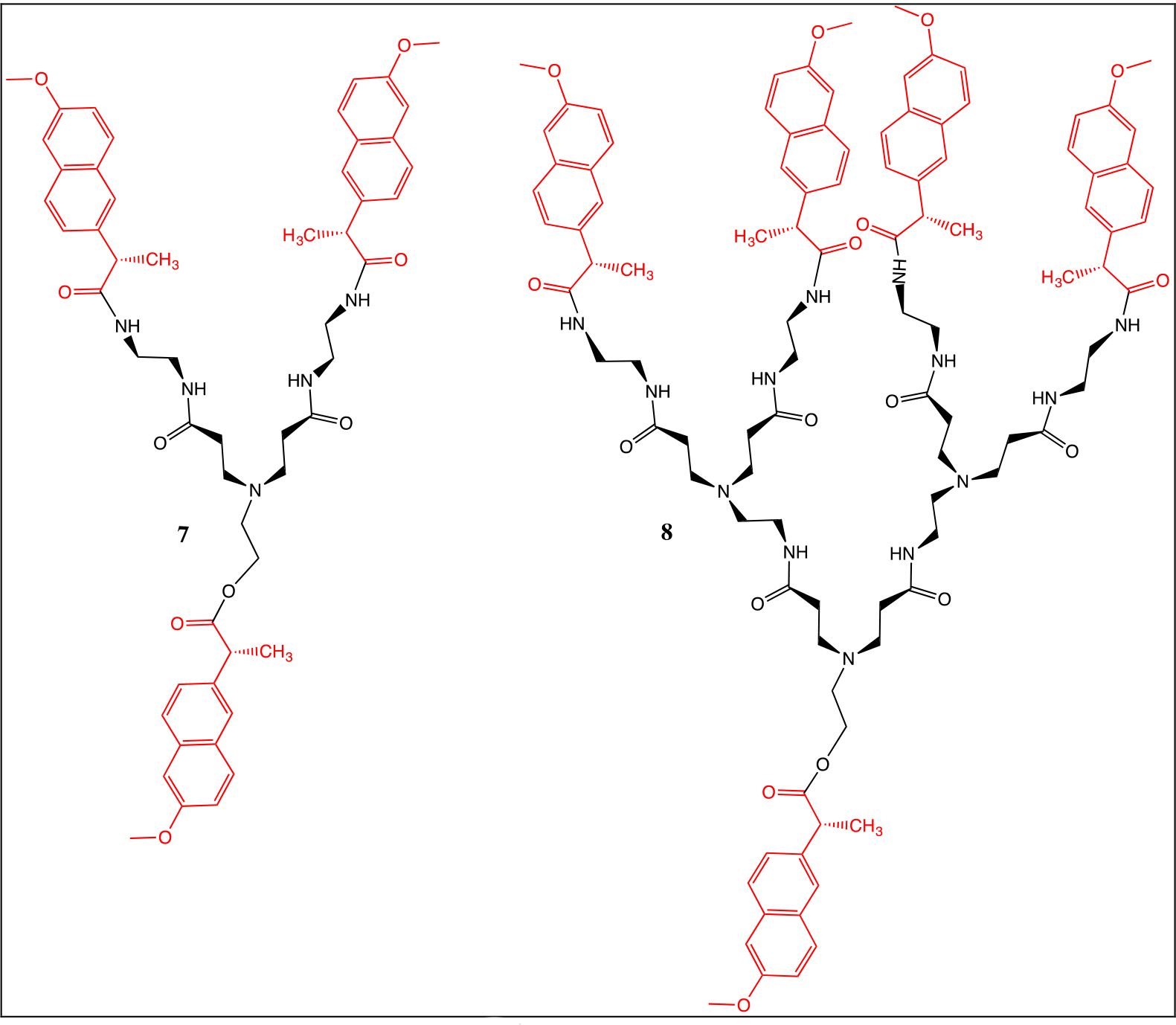

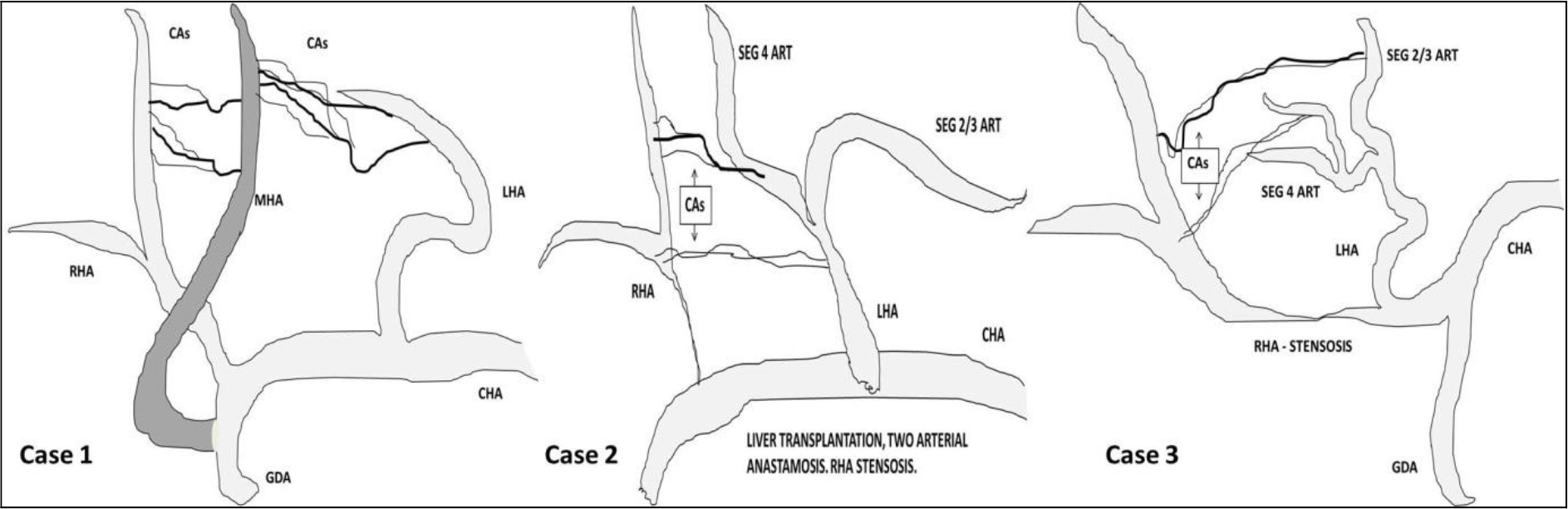

Tohma et al classified CAs in to type 1a, 1b and 2 if arising from middle hepatic artery, segment 4 artery and left hepatic artery respectively. Authors have also classified CAs arising from right anterior hepatic artery, right hepatic artery or both as type 1, 2 and 3 respectively. In the present article we have presented all 3 cases with CAs arising from left side. In first case CA was arising from middle hepatic artery (type 1a). However in after embolizing segment 4 artery we were able to see tiny collaterals from left hepatic artery supplying the segment 4 area. So this type of collaterals from both middle and left hepatic artery is not mentioned in literature. In second case of post liver transplant CA was from segment 4 hepatic artery (type 1b). In third case CA was arising from both the branches of left hepatic artery (segment 4 artery and segment 2/3 branches). Our first and third cases described different types to Toham et al classification of CAs arising from left arteries (Diagram 1).

Diagram 1. Pictorial demonstration of cases.

Hepatic artery is the second most common site for visceral artery pseudoaneurysm after splenic artery. Hepatic Artery Pseudoaneurysms (HAPAs) are usually iatrogenic and can present as life threatening complications of hepatic, biliary, and pancreatic interventions. Hepatic procedures accounts for 65% of these cases. Biliary and pancreatic procedures accounts for 30% and 5% respectively [6]. HAPAs can also be associated with intra-abdominal inflammation, infection, or trauma [6]. In our first case, surgery was uneventful and patient developed an infected biliary collection near hepatico-jejunostomy site on post operation day 5. All the authors felt right HAPAs were likely caused by infection (Klebsiella aerogenes bacteria) rather iatrogenic, as patient recovered well after endovascular reintervention.

Coil embolization or exclusion of the pseudoaneurysms by stent graft is most effective treatment option in an emergency setting, especially when associated with an infection. Both proximal and distal ends of the parent arteries of the aneurysm must be embolized simultaneously to block off the pseudoaneurysm in an extra hepatic HAPA, while proximal embolization alone can be performed for an intrahepatic arterial aneurysm; however, reestablishment of collateral circulation increases the risk of re-rupture of the aneurysms [7]. In our case extra parenchymal right HAPAs were seen, which were initially embolized by proximal solitary coil occlusion; however the coil migrated, pseudo-aneurysms were re-perfused and bled again. Later successful embolization was performed by an interventional radiologist with multiple coils in RHA, gel foam in CAs and coil in middle hepatic artery.

Early (<1 month) arterial complications are associated with graft loss and a high mortality rate after Orthotropic Liver Transplant (OLT). Hepatic Artery Stenosis (HAS) and Hepatic Artery Thrombosis (HAT) are the most common hepatic arterial complications, with high rates of morbidity and mortality. Untreated significant HA anastomotic strictures can progress to HAT (65% at six months follow up). HAS is less frequently associated biliary complications compared to HAT. Biliary complications can be seen up to 67% in liver transplant recipients with HAS. Reduction of arterial flow during liver transplant is commonly associated with biliary tree complications due to ischemic processes. In some cases, HAS is likely to stimulate the development of arterial collaterals that protect the liver from ischemia at the time of HAT [8].

Doppler Ultrasound (DUS) is the gold standard investigation to assess hepatic artery patency in cases of HAT with sensitivity up to 92% or an increased Resistive Index (RI). Anatomical defects (stenosis or kinking) can be detected by CT angiogram or conventional angiography with a high sensitivity and specificity. Early HAS can be detected by DUS with a sensitivity of 100%, a specificity of 99.5%, a positive predictive value of 95% and a negative predictive value of 100%, and an overall accuracy of 99.5%. However MDCTA and standard angiography are the gold standard for HAS diagnosis [8].

Biliary tract ischemia contributes to biliary strictures and anastomotic leakage in liver transplants and can be seen up to 34% of patients. Division of the CA during graft donation may potentially lead to biliary ischemia and complications. Thus, during graft donation the right or left hepatic artery should not be dissected and separated from the bile duct distally to prevent biliary ischemia [1]. In our second case anastomotic stenosis of RHA has led to development of anastamotic biliary stricture (choledocho-choledochostomy) and visible biliary dilatation from 3rd day.

The third case is an uncommon presentation of gallbladder carcinoma involving the right hepatic artery with development of visible hepatic arterial arcades on CECT scan. Primary gallbladder carcinoma is the most common malignancy of the biliary tract. The most common route of dissemination is direct invasion of the liver. Hepatic invasion or hepatic metastasis has been reported in as many as 30%–80% of cases of gallbladder carcinoma. Gall bladder malignancies with vascular invasion (main portal vein or hepatic artery) are typically not amenable to surgery [9].

In conclusion, first attempt of intervention failed in first case due to hepatic inter arterial communication and incomplete embolization, which was later successfully embolized by an Interventional radiologist. Percutaneous drain must be placed only after treating pseudoaneurysms. In second case of post liver transplantation, arterial complication was precisely detected on CECT and not on Doppler ultrasound. Right lobe of graft survived because of hepatic inter arterial communications and no intervention was required, however patient developed few peripheral subcapsular ischemic changes in right lobe and low grade biliary dilatation which was managed by endoscopic plastic stenting. Our first and third case, show different types of arterial communicating arcades arising from middle hepatic artery (from GDA) and left hepatic artery. Thus knowledge of hepatic inter lobar arterial communication is important while treating and diagnosing arterial diseases of both native and transplant liver.

References

- Tohma T, Cho A, Okazumi S, Makino H, Shuto K, et al. (2005) Communicating arcade between the right and left hepatic arteries: evaluation with CT and angiography during temporary balloon occlusion of the right or left hepatic artery. Radiology 237: 361–365.

- Charnsangavej C, Chuang VP, Wallace S, Soo CS, Bowers T (1982) Angiographic classification of hepatic arterial collaterals. Radiology 144: 485–494.

- Redman HC, Reuter SR (1970) Arterial collaterals in the liver hilus. Radiology 94: 575–579.

- Mays ET, Wheeler CS (1974) Demonstration of collateral arterial flow after interruption of hepatic arteries in man. N Engl J Med 290: 993–996.

- Koehler RE, Korobkin M, Lewis F (1975) Arteriographic demonstration of collateral arterial supply to the liver after hepatic artery ligation. Radiology 117: 49–53.

- Harvey J, Dardik H, Impeduglia T, Woo D, DeBernardis F (2006) Endovascular management of hepatic artery pseudoaneurysm hemorrhage complicating pancreaticoduodenectomy. J Vasc Surg 43: 613–617.

- Ji WB, Wang WZ, Xu XJ, Mi YC, Fu X, et al (2017) Arterial embolization in treatment of hepatic artery pseudoaneurysm. Acta Medica Mediterranea 33: 449.

- Piardi T, Lhuaire M, Bruno O, et al (2016) Vascular complications following liver transplantation: A literature review of advances in 2015. World Journal of Hepatology 8: 36–57.

- Hussain HM, Little MD, Wei S (2013) AIRP best cases in radiologic-pathologic correlation: gallbladder carcinoma with direct invasion of the liver. Radiographics 33:103-108.