DOI: 10.31038/ASMHS.2019324

Abstract

Listening and reading to the partisan politics surrounding the ongoing conflict between the Palestinians and the Israelis, one gets the impression that this topic is all-consuming. A study using the science of Mind Genomics reveals that most respondents from a sample of young respondents do not care about the topic, nor are engaged by anything said in the media. The Mind Genomics study combined messages, policy statements, issued by the US government, presenting small vignettes, almost as news stories. The strategy prevents the respondent from responding in a politically-correct manner. The data suggest that most of the young respondents are not interested in the topic, when the data from the total panel is reported. Two mind-sets emerged, one feeling that stability and hope will be achieved through force, the other feeling that stability and hope will be achieved through economic development. The study presents a PVI (personal viewpoint identifier) to assign new people to one of the two mind-sets. The paper finishes with a discussion of the contribution of Mind Genomics to a deeper understanding of political thought and the emerging discipline of counter-factual history.

Introduction

A Long History, a Wide Scope, Inflamed Emotions

Depending upon one’s ethnic group and perhaps political / social leanings, the ongoing tensions in the Middle East, and especially between the Palestinians and the Israelis occupy either a great deal of one’s attention and concern, a moderate degree, or little at all, being even perhaps irrelevant. When talking to young people who are not politically involve and polarized, it is hard to discern the nature of the aspects which may concern them when faced with general indifference. In this exploratory paper it is impossible to deeply understand a topic which has been simmering for 70+ years, but it is possible through the science of Mind Genomics, described below, to take a ‘snapshot’ of the situation from the minds of younger people as they respond to statements about possible policy towards the Middle East.

This study represents an exploration of responses to policy statements that have been made, as well as ideas about potential economic help for the Palestinians, ideas that have not been made public, but have floated around. The focus of the study is on the degree to which any of the official statements has the power to influence young Americans, ages 17–30, either as statements which could lead to peace or which could fan the flames of war.

The published literature on the topic of Palestine vs Israel and vs the United States, as well as the actual details of the workings of the Palestinian state come in the form either of books and periodicals, or from news releases and the accumulation of a body of news both from the main mainstream media and now from the Internet. Books dealing with the topic are typically either learned articles or popular books dealing with the topic, or clearly partisan treatments of the topic, the appellation ‘partisan’ being a description of the emotions, not a judgment of the correctness of the treatment [1–4]. A list of the books dealing with the subject would stretch from the 1950’s to today, with no end in sight, as the Middle East continues to occupy the attention of the world, the eruptions in the Middle East, whether minor or major, causing discomfort, and then fear for the disruption of the world order.

When it comes to deeper understanding of the subjective feelings, there are the innumerable public opinion polls about every aspect of the situation, these polls taken often in Israel, and often in the rest of the world as well. The answers emerging from those polls comprise ‘factoids’, with a subsequent attempt tie together the factoids discovered in the polls, linking them to other information about the topic. Yet the deeper understand could become even deeper with better tools, providing a sense of the inside of the mind, in a way metaphorically analogous to the way the MRI technology provides a sense of the nature of body tissue. That will be the topic of this paper.

Polling versus Experimentation

The typical world of responses to public policy invokes the now-institutionalized business and discipline of opinion polling. Scarcely a day goes by that another people comes out to present to the thinking public what the people ‘think, believe, and do.’ The professional associations such as AAPOR (American Association of Public Opinion Research) for example, serves as a bedrock to validate the efforts of the pollsters who present their approaches as scientific. Public opinion research is presumed to be scientific, working with representative samples of respondents, statistical tests of different from the discipline of inferential statistics and of course best practices about how to phrase questions, how to phrase answers, and so forth.

A recurring key issue is that when one does a poll, one invites the respondent to invoke a ‘mental editor,’ to be politically correct. This mental editor thus skews the results, a skew that cannot necessarily be overcome by the best of the recommended practices. The researcher MUST ask the respondent questions in a direct fashion. Once the respondent can address each question, one question at a time, it is possible and indeed quite straightforward to adopt a stance, tailoring one’s responses to accord with that stance, whether the stance, the point of view truly represents or does not represent one’s inner feeling.

In contrast to polling and surveys or asking the respondent to describe or vote, there is the world of experimentation. Admittedly, experimentation is far easier when one can control the stimulus, varying the stimulus in predefined ways, measuring the responses, and attributing the ‘change’ in the dependent variable to the precise change in the controlled, independent variable. This approach works very well to understand the dynamics of simple things, such as how the physical ingredients of a food or beverage drive our liking, or the relation between the number of hours one studies for a test and the score on the test

Can experimentation be applied to understand the Palestine-Israel issue? Certain one cannot easily vary the features of a nation in the same way that one can vary the amount of sweetener in a beverage. Yet, what if one were to describe a social situation in different, systematically varied ways. What would happen if one presented a positive, upbeat message versus a negative, downbeat message? How would people react?

The foregoing idea notion involves experimenting with ideas, metaphorically combining the notion of experimentation using statistical design in the spirit of creating and testing aspects of notion of counterfactual history. Instead of presenting history or world issues as simple ides with aspects to be evaluated and discussed, we create scenarios or combinations of ‘facts’ about the issue, these facts having actually happened, or could have happened. We instruct respondents to read these ‘counterfactual combinations,’ vignettes, and respond to them. The respondents have no idea whether what they are reading is true, not true, possible, impossible, or even whether what they are reading comes from a completely different topic or subject area, merged into the set of stimuli.

The respondents simply evaluate these vignettes, from which we learn a great deal about how they perceive the situation and its features. We do not ask the respondent to act in a rational way, but rather present the respondent with the vignettes, and acquire their responses, at an almost intuitive level, a way labelled by Nobel Laureate Kahneman as ‘System 1’ [5]. The actual inspiration for such an approach comes not so much from a deep philosophical inspiration as it does from the way a company learns how to say the right things to the customer, for example, when marketing Jello®.

The systematic experimentation opens a whole new branch of social science, akin to the alternative worlds create by science fictions. We are simply creating alternative situations, alternative realities to be tested. The approach, first used for marketing [6,7], and now for social issues, may be the experimental version of ‘counterfactual history.’

How Mind Genomics Studies Problems

It is clear from everyday life that people hold different views about the same topic. The differences can be vanishingly small, or dramatic. One need only read accounts of the same event in different media outlets to recognize the power of the report to present the same idea as an opportunity, and another report to present the same idea as the impetus for a debacle. Understanding the differences in the points of view of the reporters is clear, and can be done by the analysis of language, and so-called ‘sentiment analysis’ [8].

What is harder to understand is the deep response of ordinary people to the messages which describe a situation. What is meant here is not the initial, almost knee-jerk reaction to the message and the situation, but rather the deep, often automatic response to the message. Do people really pay attention to the individual messages in politically motivated writing, or is their response simply a generalized, undifferentiated reaction?

Mind Genomics enables us to understand the deeper responses to test stimuli. Mind Genomics does so by mixing and matching different messages, different ideas, into simple to read combinations, vignettes, and then secures the response of individuals to these vignettes, these mixtures. The vignettes being as they are, combinations, defy the desire of the response to be ‘correct’ because the compounding of the messages leaves the respondent unable to formulate what is a consistent response. The desired consequence is that respondent ends up abandoning the desire to be rational, correct, and consistent, and simply answers at almost an intuitive, ‘gut level.’ It is at this intuitive level that one’s true feelings emerge, guiding as they do the selection of the response (Moskowitz, 2012).

The Process of Mind Genomics

Mind Genomics follows a set of well-choreographed steps, beginning with the selection of cognitively meaningful stimuli (messages which are presumed to have real meaning), and ending with the discovery of possibly new-to-the-world mind-sets, different ways to think about the same problem. The phrase ‘Mind Genomics’ is a metaphor for the discover of these different mind-sets for a situation, similar to the discover of alleles for a gene.

Step 1 – Define the topic: It may seem very simple to ‘define a topic,’ but it is not. Mind Genomics operates at the granular level. A topic, for example, cannot be an overwhelmingly large issue like the entire Palestine-Israel issue. If anything, the topic should error on the side of being very small, localized, specific, yet with different aspects. Mind Genomics could do a good job on a topic such as how to arrange a seating room for a conference between Palestinians and Israelis. For this topic, we focus on the reactions of young people to pronouncements about the Palestine-Israel situation, made by the State Department, a topic which is large, but not overwhelmingly so.

Step 2 – Define four questions to be answered, with the structure that at some level the set of questions are arranged to ‘tell a story’: In every topic there exist many types of stories to be told. The objective of Mind Genomics is to determine what specific elements of the story, what messages, resonate with the respondent. In order to discover these resonating elements, we must embed the messages into a story, doing so by means of a method which combines the messages in a structure. The overriding structure, the story, must make intuitive sense, even when the individual messages when thrown together do not necessarily make sense. Hence, the four questions, which may be likened to the way a reporter structures a story (who, what, where, when, why, how). The four questions are left to the researcher. They will never be shown to the respondent, but rather they will serve as prompts to help develop the specific elements. Table 1 shows these four questions for our study on the language of pronouncements about Palestine and Israel.

Table 1. The four questions and the four answers to each question.

|

Question 1 – What is the U.S. Policy?

|

|

A1

|

U.S. Embassy moves to Jerusalem from Tel Aviv.

|

|

A2

|

U.S. recognizes Israeli sovereignty over the disputed Golan Heights… strategic plateau Israel acquired after the Six-Day War.

|

|

A3

|

U.S. passes Anti-Terrorism Clarification Act (ATCA)… ends U.S. funds to the West Bank & Gaza.

|

|

A4

|

U.S. President Donald Trump say U.S. aid cuts aimed at pressuring the Palestinians to return to peace talks.

|

|

Question 2 – What is the U.N. Policy?

|

|

B1

|

The U.N. general assembly has a permanent feature on its annual agenda titled “Human rights situation in Palestine & occupied Arab territories”.

|

|

B2

|

U.N. condemns the firing of rockets from Gaza into Israeli civilian areas

|

|

B3

|

Report from U.N. claims that Israeli security forces may have committed war crimes & should be held accountable for the deaths at protests in Gaza last year

|

|

B4

|

Israel was the most condemned country at the U.N. in 2018, with the General Assembly passing at least 20 resolutions against Israel

|

|

Question 3 -What do the Israelis and Palestinians say and do to express their goals?

|

|

C1

|

Israel says protests, described by Gazans as the Great March of Return, are particularly violent… could act as a cover for Hamas, to infiltrate Israel, carry out attacks.

|

|

C2

|

Prime Minister Netanyahu said Israel will annex settlements in the West Bank.

|

|

C3

|

As U.S. peace plan rollout approaches, Palestinians voice rejection.

|

|

C4

|

Thousands of Palestinians demonstrate along the Gaza border fence with Israel.

|

|

Question 4 – What are possible efforts to help economic development of the region?

These are new ideas to be explored within the study

|

|

D1

|

U.S. offers economic development aid to create Middle East Institute of Competitive Excellence.

|

|

D2

|

U.S. groups approach Palestine with opportunity to work with Israel to create better economic conditions.

|

|

D3

|

U.S. creates Institute to help Palestinians become more entrepreneurial.

|

|

D4

|

U.S. Jewish organizations reach out to support economic cooperation between Palestine and Israel.

|

Step 3: Create four answers to each question: The answers, short statements or phrases, are the material that Mind Genomics combines, to produce the vignettes. The answers may be actual statements, possible statements, and even new ideas to be explored within the study. Table 1 presents the four questions, and for each question the four answers. Questions 1–3 and their answers were taken from news stories. Question 4 and its four answers were exploratory ideas developed by author Moskowitz over the past decade, but do not yet exist, at least in a well-recognized public forum. It is important to stress that one need not use the precise words, especially when the language is the less than ‘precise and punchy’ language of diplomacy and reporting favored by government.

Step 4: Combine the elements into an experimental design: The experimental design can be likened to a book of interconnected recipes, with each combination defined as having a specific answer from each of the four questions. An example of the experimental design appears in Table, which specifies the first nine combinations for Panelist #1. The experimental design ensures that each element or answer appears equally often, and that each element is statistically independent of every other element, allowing for OLS (ordinary least-squares) regression to be applied to the dataset. The vignettes are ‘partial,’ meaning that some vignettes or combinations lack an answer from one or two of the four questions. This lack is deliberate, ensuring that the coefficients estimated by the regression modeling have ‘absolute value,’ i.e., the ratios of coefficients are meaningful [9, 10,11].

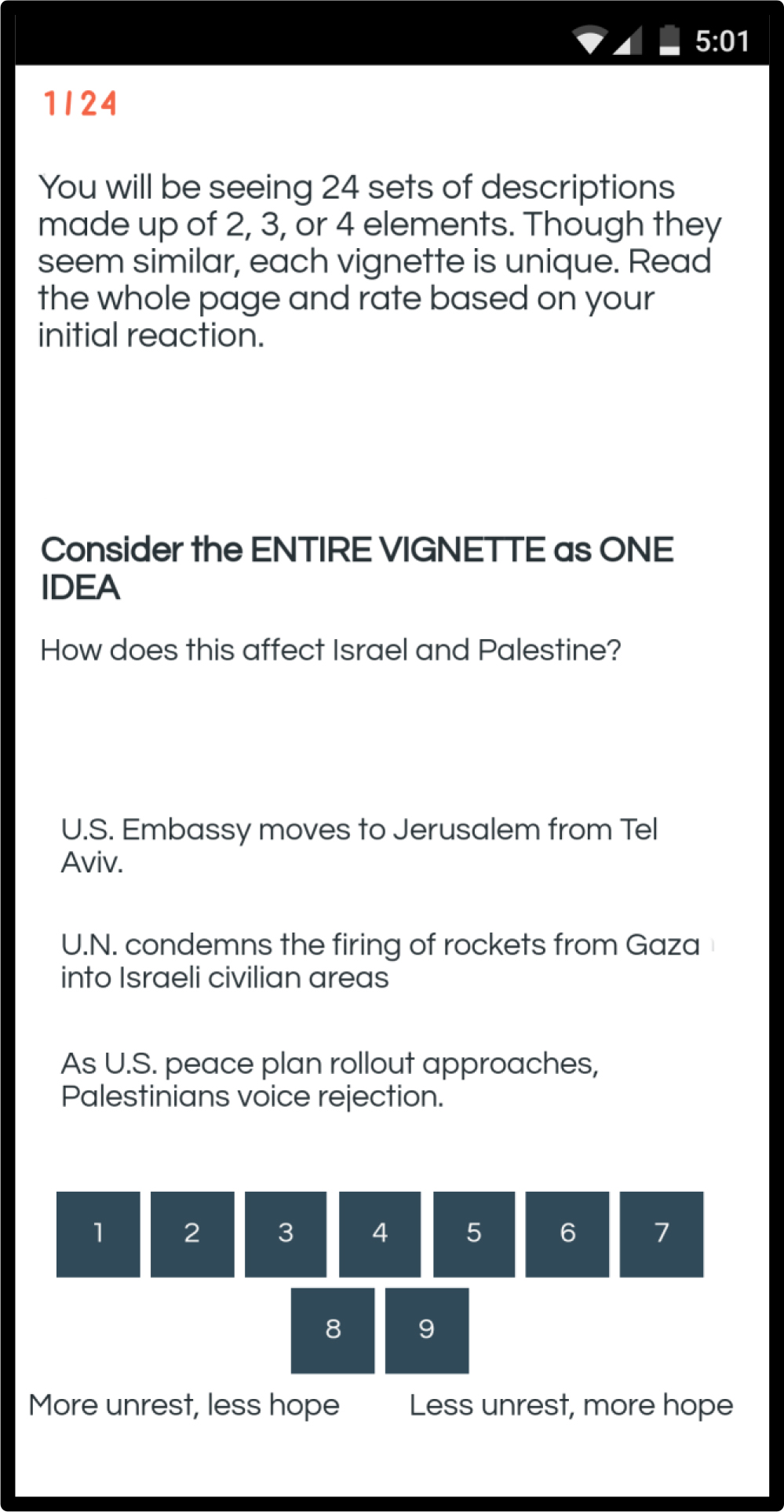

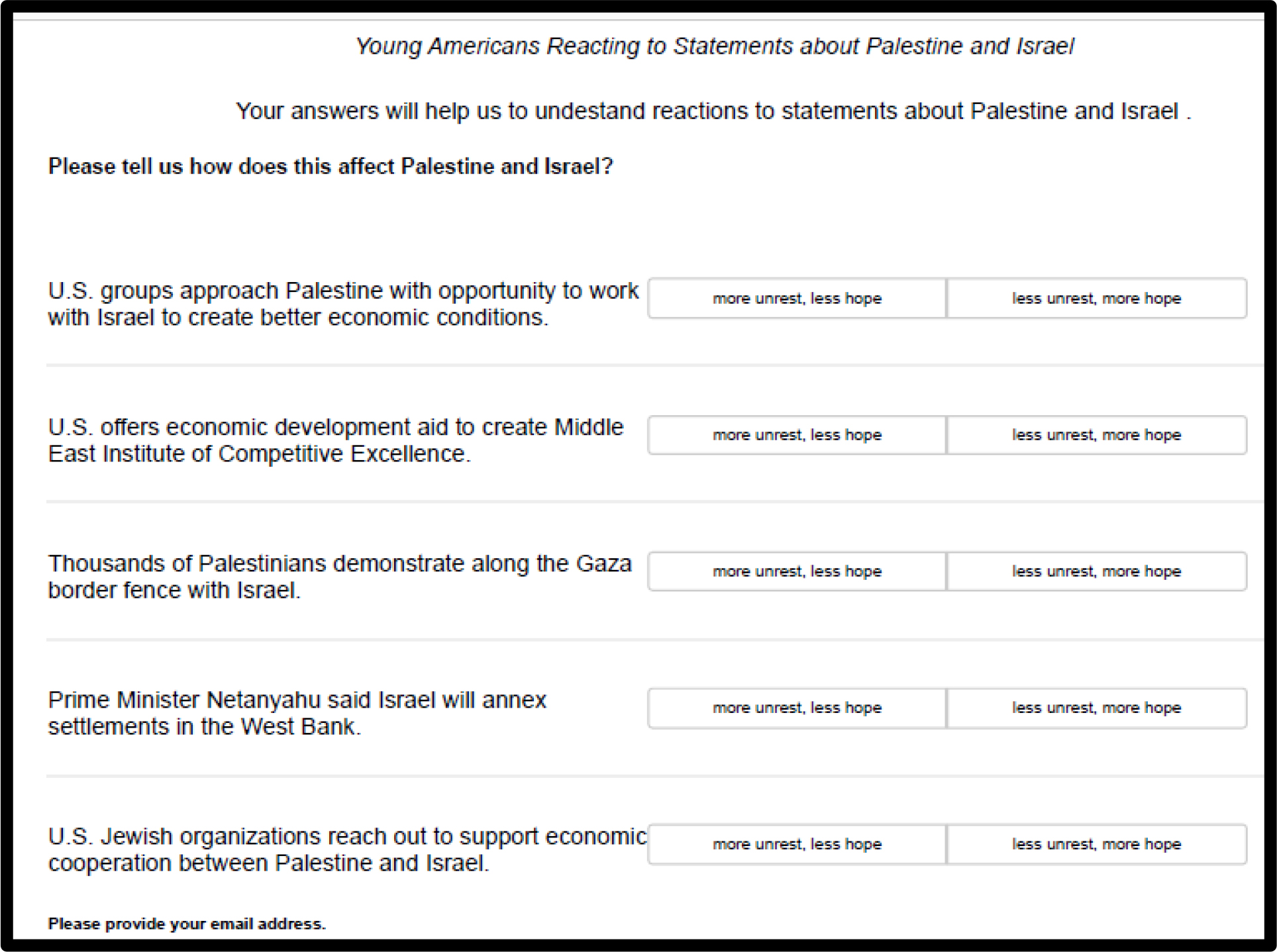

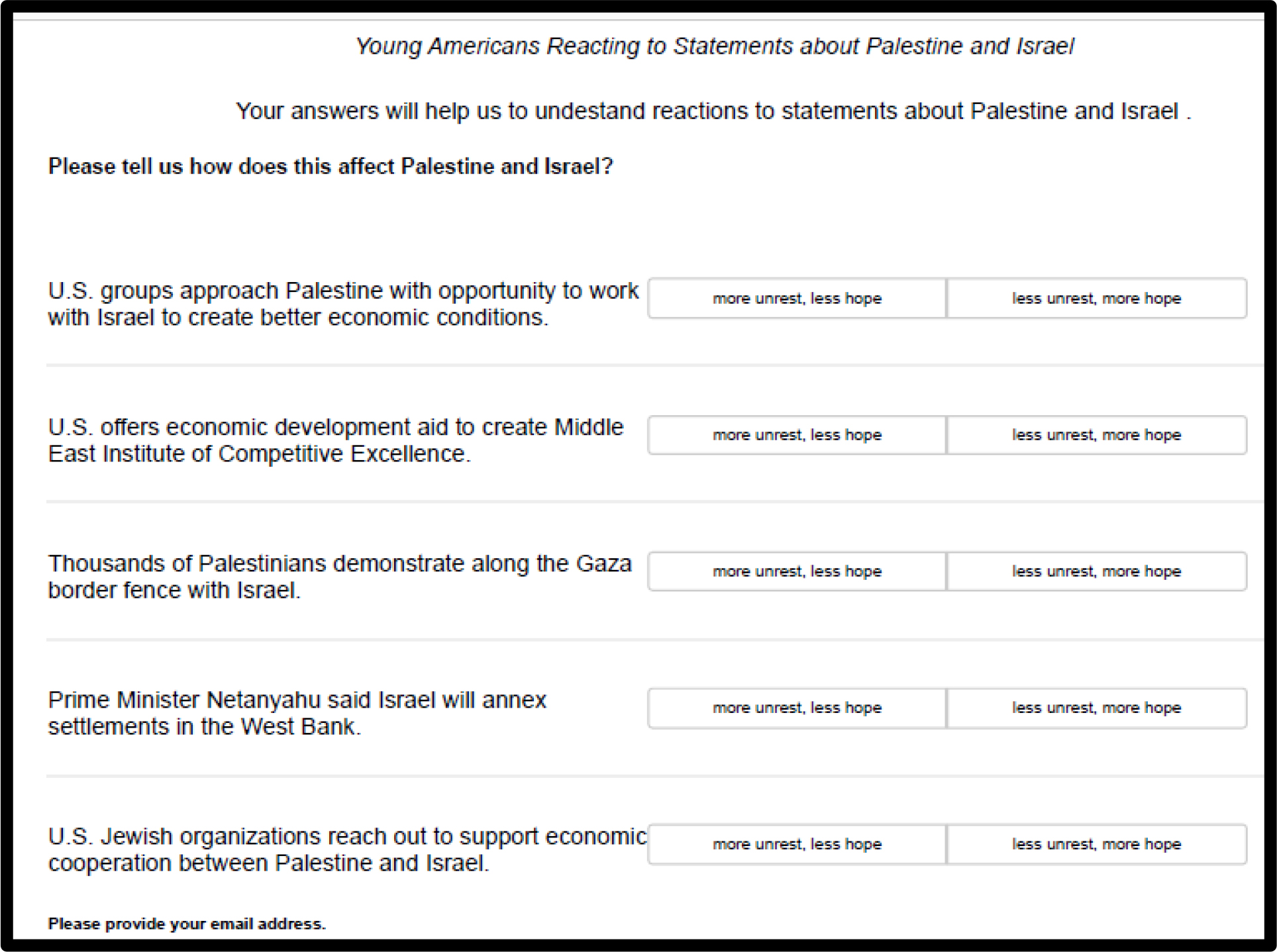

Figure 1 presents a screen shot from one of the vignettes. The vignette is laid out to be simple, viewable on either a smartphone or a tablet/PC with the layout appropriate for the screen on which it is viewed, and to be available on any platform. The format is set up to be stark, with one element atop the other, lacking connectives. This format may seem a bit different from the more conventional ‘dense’ format of concepts with the proper language, paragraph form, and replete with connectives. The rationale for the stark format is that the format leads to easier ‘grazing’ for information, and is less tiring, especially when the respondent evaluates 24 such vignettes, one after the other. The easier the task can be made, the more likely that the respondent will complete the task, and not drop out, as is often the case.

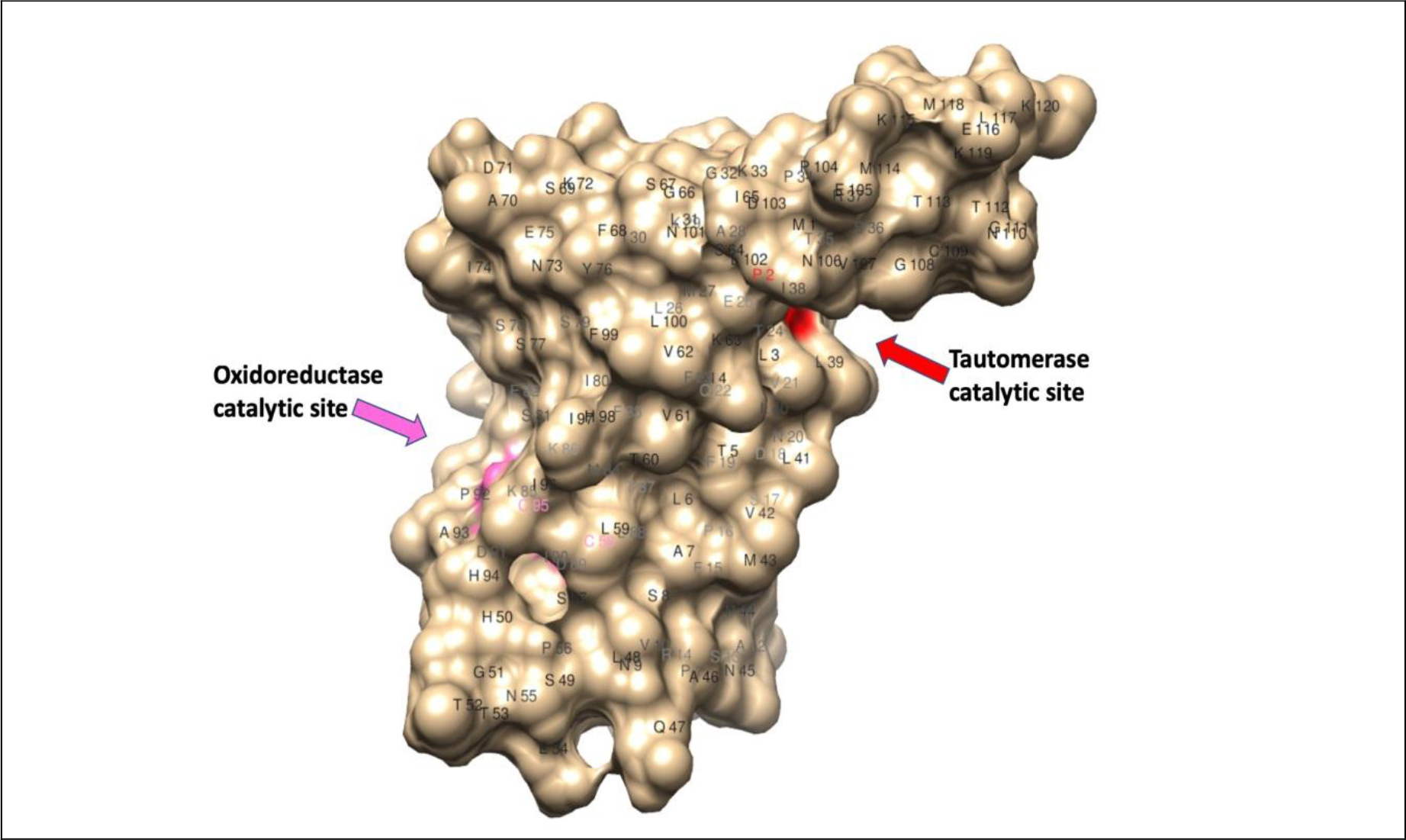

Figure 1. Example of a vignette as it appears on a smartphone.

Most studies with experimental design specify a certain, very limited number of combinations, all tested by many individuals. The objective of the replication is to more accurately estimate the average assigned to the combinations. The sampling of possible combinations is limited, but the ‘strength’ or ‘performance’ of each combination is accurately estimated. Mind Genomics works in a different fashion, more in the spirit of the MRI. Each respondent evaluates a unique combination of 24 vignettes or combinations, like a ‘snapshot’ of the topic. At the same time, since each respondent evaluates a different set of combinations, the Mind Genomics effort estimates the performance of different parts of the underlying ‘space.’ What is missing in the accuracy of one set of estimates provided by replication is more than made up by sampling a great deal more of the space by Mind Genomics.

The respondents were members of the Luc.id panel, comprising 20+ million prospective participants around the world, who had previously agreed to participate in these types of studies. The respondents were specified to be ages 18–30, to live in the United States, with half the panel being male and half the panel being female

Table 2 presents the structure and performance of the first nine vignettes (Vig1-Vig9) for the first respondent, an 18-year old female. The top part of Table 2 presents the specific combination. The regression program cannot use the data in this form. We ‘expand’ the design to generate 16 variables, one variable corresponding to each element or answer. When a vignette contains the element, the value is ‘1’, else the value is ‘0.’ In this form the regression model can easily analyze the data, to produce a model. Table 2 shows that five vignettes are incomplete. The rationale for this is that only with incomplete or so-called ‘partial profiles’ can the regression analysis return with absolute values for the estimates of the coefficients.

Table 2. The first nine vignettes for respondent #1, showing the combinations, the expanded design for statistical modeling by regression, and the set of dependent variables.

|

Row

|

Vig1

|

Vig2

|

Vig3

|

Vig4

|

Vig5

|

Vig6

|

Vig7

|

Vig8

|

Vig9

|

|

Specific Combination

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Question A

|

A3

|

A1

|

A1

|

A4

|

A2

|

A2

|

A3

|

A4

|

A4

|

|

Question B

|

0

|

B4

|

B3

|

B4

|

0

|

B3

|

B2

|

B3

|

B1

|

|

Question C

|

C3

|

C1

|

0

|

C1

|

C4

|

C2

|

C2

|

C4

|

0

|

|

Question D

|

D1

|

0

|

D1

|

0

|

D2

|

D4

|

D3

|

D3

|

D4

|

|

Binary Expansion

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

A1

|

0

|

1

|

1

|

0

|

0

|

0

|

0

|

0

|

0

|

|

A2

|

0

|

0

|

0

|

0

|

1

|

1

|

0

|

0

|

0

|

|

A3

|

1

|

0

|

0

|

0

|

0

|

0

|

1

|

0

|

0

|

|

A4

|

0

|

0

|

0

|

1

|

0

|

0

|

0

|

1

|

1

|

|

B1

|

0

|

0

|

0

|

0

|

0

|

0

|

0

|

0

|

1

|

|

B2

|

0

|

0

|

0

|

0

|

0

|

0

|

1

|

0

|

0

|

|

B3

|

0

|

0

|

1

|

0

|

0

|

1

|

0

|

1

|

0

|

|

B4

|

0

|

1

|

0

|

1

|

0

|

0

|

0

|

0

|

0

|

|

C1

|

0

|

1

|

0

|

1

|

0

|

0

|

0

|

0

|

0

|

|

C2

|

0

|

0

|

0

|

0

|

0

|

1

|

1

|

0

|

0

|

|

C3

|

1

|

0

|

0

|

0

|

0

|

0

|

0

|

0

|

0

|

|

C4

|

0

|

0

|

0

|

0

|

1

|

0

|

0

|

1

|

0

|

|

D1

|

1

|

0

|

1

|

0

|

0

|

0

|

0

|

0

|

0

|

|

D2

|

0

|

0

|

0

|

0

|

1

|

0

|

0

|

0

|

0

|

|

D3

|

0

|

0

|

0

|

0

|

0

|

0

|

1

|

1

|

0

|

|

D4

|

0

|

0

|

0

|

0

|

0

|

1

|

0

|

0

|

1

|

|

Ratings

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Rating

|

6

|

6

|

7

|

2

|

8

|

8

|

7

|

7

|

7

|

|

Response Time (seconds)

|

9.0

|

3.6

|

7.6

|

9.0

|

5.6

|

9.0

|

9.0

|

2.4

|

4.8

|

|

Top2

|

0

|

0

|

0

|

0

|

100

|

100

|

0

|

0

|

0

|

|

Bot2

|

0

|

0

|

0

|

100

|

0

|

0

|

0

|

0

|

0

|

|

Classification

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Respondent

|

1

|

1

|

1

|

1

|

1

|

2

|

1

|

1

|

1

|

|

Gender (1=male, 2=female)

|

2

|

2

|

2

|

2

|

2

|

2

|

2

|

2

|

2

|

|

Age

|

18

|

18

|

18

|

18

|

18

|

18

|

18

|

18

|

18

|

Below the binary expansion we see the ratings.

- The original ratings were on the anchored 1–9 scale: (1=more unrest, less hope) … (less unrest, more hope)

- The response time is defined as the number of seconds between the appearance of the vignette on the ‘screen’ and the response. The response time is measured to the nearest tenth of a second.

- The Top2 is a binary transformation of the original rating data. Ratings of 8–9, close to the high end of the scale (less unrest, more hope) are transformed to 100. The remaining seven scale points, 1–7, are transformed to 0 to denote that they are not positive responses. The ‘not positive’ does not mean negative, but rather means not strongly positive and optimistic.

- The Bot2 is another binary transformation of the original rating data. Ratings of 1–2, close to the low end of the scale (more unrest, less hope) are transformed to 100. The remaining seven scale points, 3–9, are transformed to 0 to denote that they are not negative responses. Once again, the ‘not negative’ does not mean positive, but rather means not strongly negative and pessimistic.

Selecting the appropriate data to include in the analysis

The Mind Genomics effort creates a great deal of data, since each respondent evaluated 24 vignettes in terms of feelings (optimistic versus pessimistic), and since the response time was also measured. The Mind Genomics program records the response time in tenths of seconds. Typically, the first vignette requires an aberrantly long time, presumably because the respondent does not yet know what to do in terms of where the response key, and so forth. By the time the respondent rates the second vignette, the response times become more stable, and do not show aberrantly high values. All analyses reported here were done without the first vignette from each respondent, and without vignettes whose response time exceeded 10 seconds. Ongoing observations of these studies suggests that when a respondent multi-tasks, the response times are substantially, losing their ability to reflect on underlying behaviors.

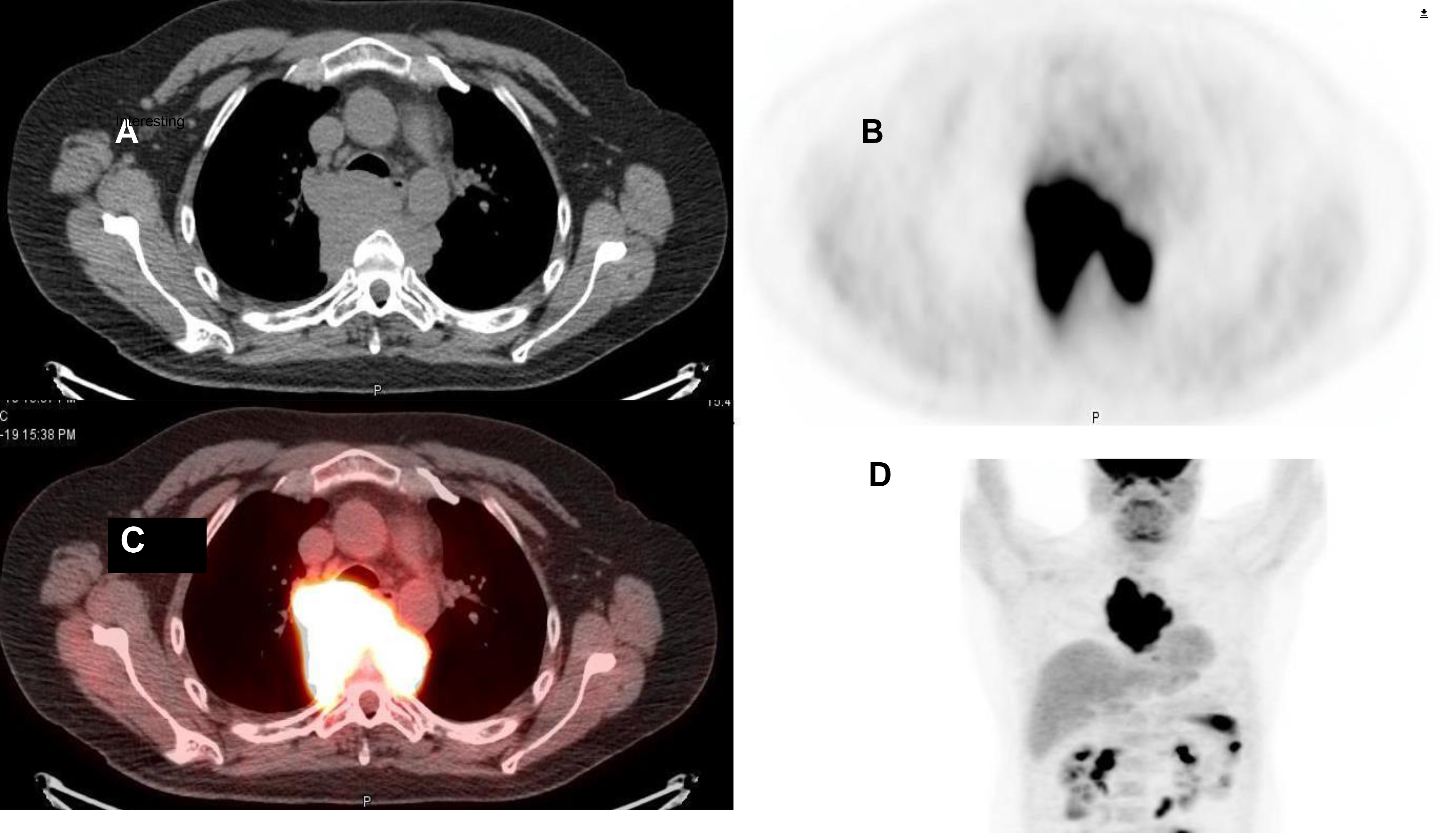

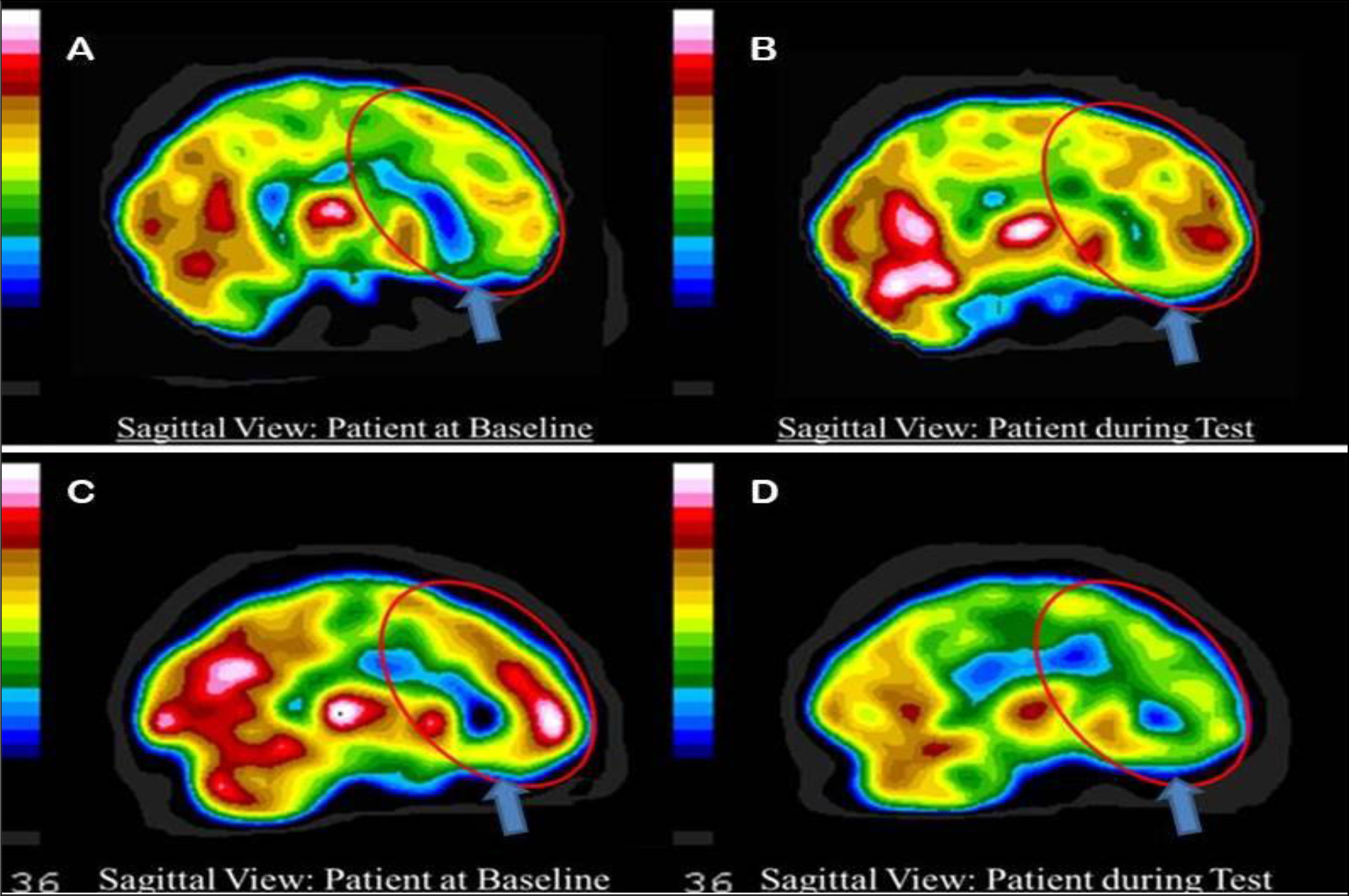

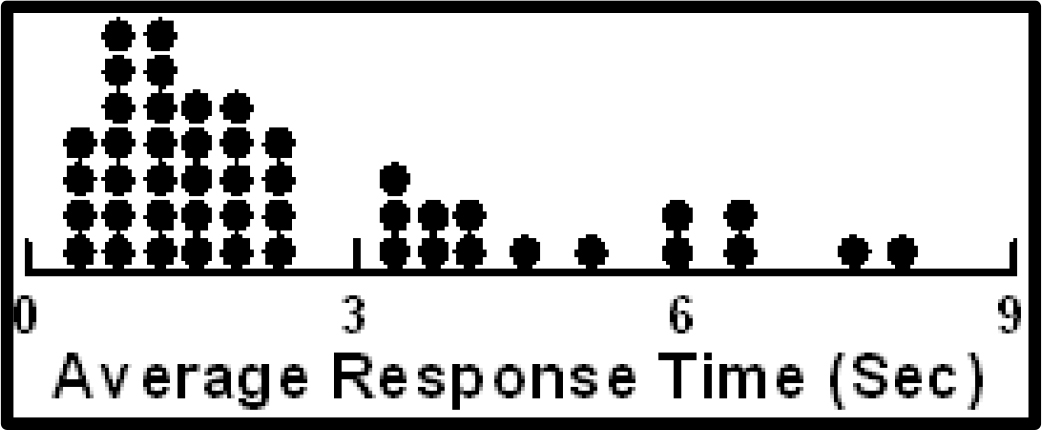

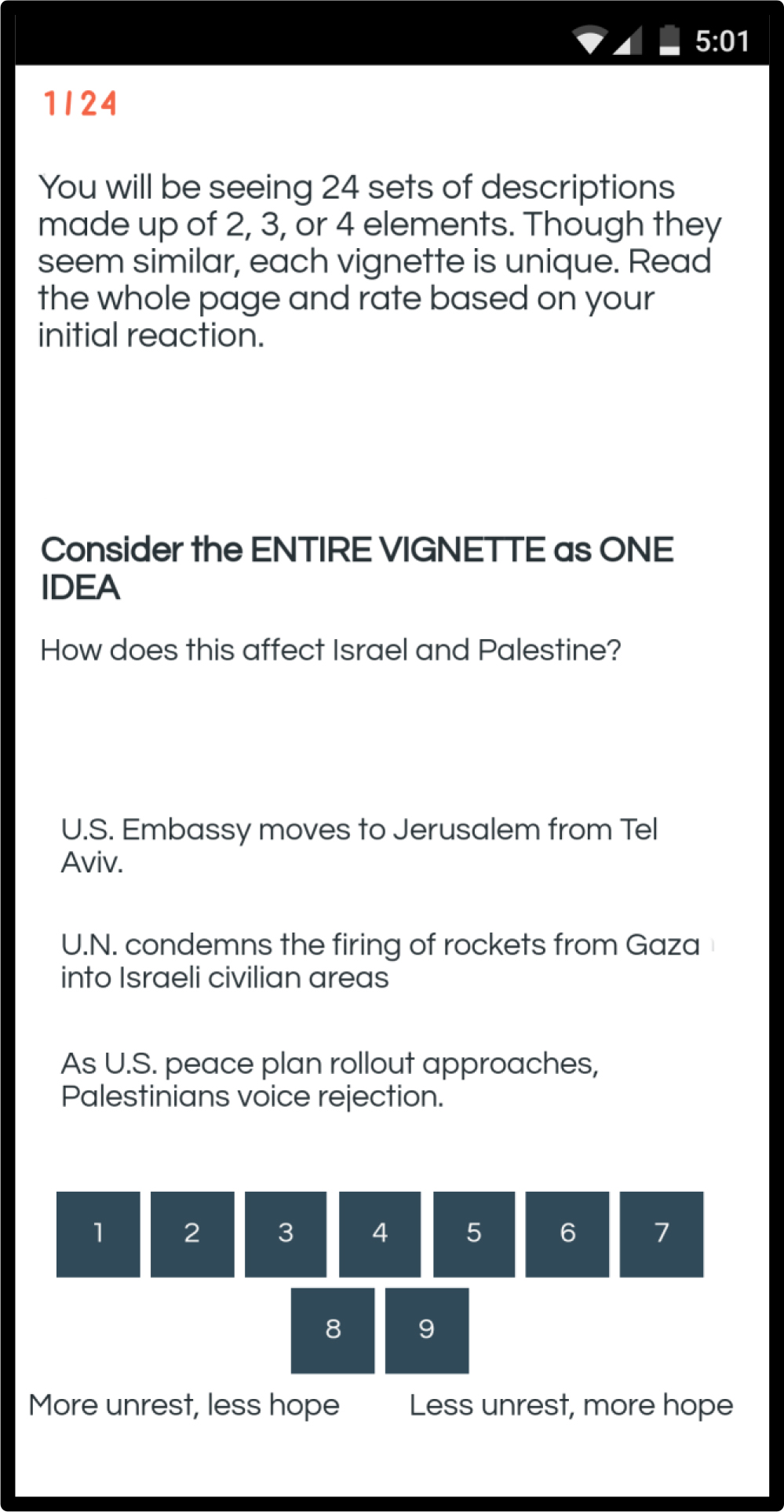

Do respondents read the information in the vignettes, or simply gloss over the information? We do not know whether a respondent reads the information in the vignette, pausing to interpret each message, or whether the respondent skips through. Figure 2 shows the distribution of average response times. The average responses are quite fast, 3 seconds or shorter. Similar types of ‘serious studies’ about public policy have shown longer response times, 5–6 or so, on average. In contrast, ‘fun studies’ about food and shopping generate many short response times. The many short response times coupled with the fact that the study is about a serious topic suggests that many of the respondents probably skim over the information, and do not absorb it. In contrast, the response times were systematically longer in another study conducted with different respondents, also from Luc.id, this study dealing with the interesting and relevant topic.

Figure 2. Distribution of average response times across the respondents. The first vignette has been eliminated from the calculation of the average.

About the respondents themselves – pessimistic or optimistic on average?

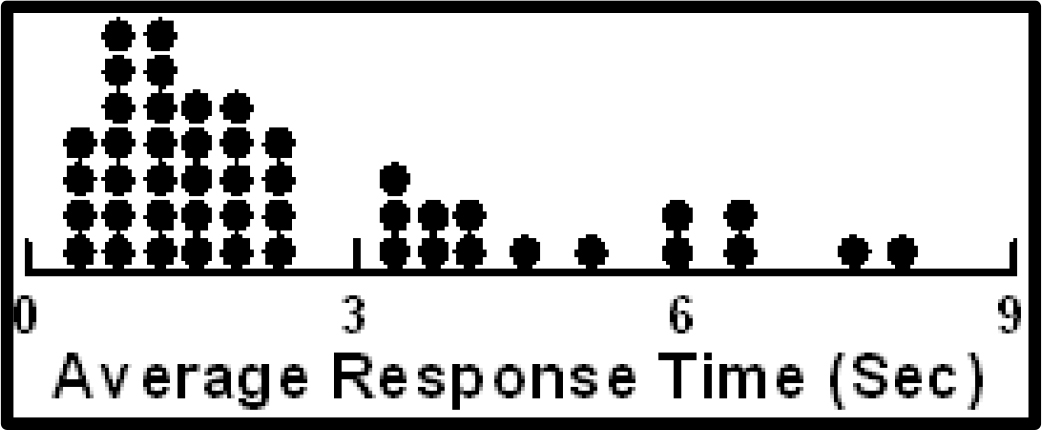

Our 50 respondents each evaluated 24 vignettes. The initial data transformation created a binary scale for optimism (8–9=100, 1–7=0), and a binary scale for pessimism (1–2=100, 3–9=0). Thus, each respondent generated approximately 23 numbers for optimism, and 23 numbers for pessimism, corresponding to the 23 vignettes considered for analysis

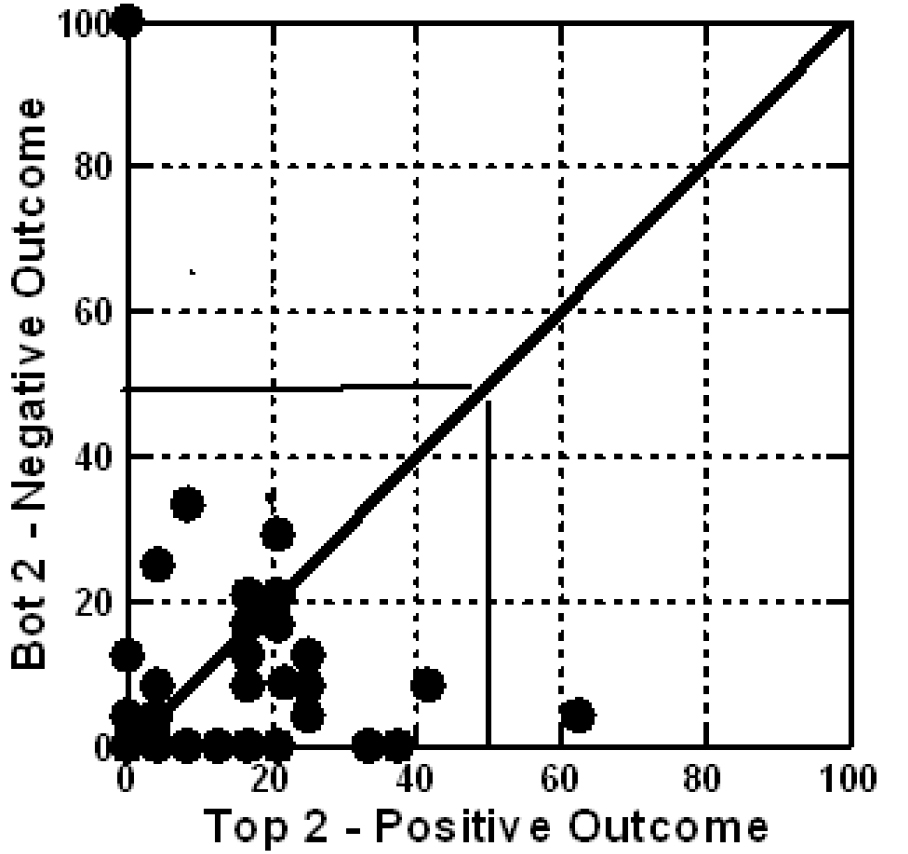

The average of the Top2 for one respondent gives a sense of the percent of the times that the respondent feels optimistic. In turn, the, the average of the Bot2 for one respondent gives a sense of the percent of the times that the respondent feels pessimistic. The averages can range from (0,0) to (100,0) or (0,100). The (0,0) average means that all the respondent’s ratings are in the middle, neither optimistic nor pessimistic. Averages of optimistic respondents fall near the bottom of the graph in Figure, where the abscissa is high (high percent of optimistic responses), and where the ordinate is low (low percent of pessimistic responses.) Figure 2 suggests about only about four respondents from the 50 are optimistic.

When we turn the focus to pessimistic respondents, we must look for respondents whose ordinates are high, but whose abscissas are low. These respondents have a large proportion of their responses suggesting pessimism of the outcome. Figure 3 suggests about only two-three respondents can be classified as pessimistic.

Figure 3. Scatterplot of mean Bot2 vs Top2, for respondents, without the first vignette counted. Each circle corresponds to one of the respondents.

The results – what drives a sense of positivity (Top2), a sense of negativity (Bot2), or engages

The real ‘meat’ of a Mind Genomics study emerges when we look at the linkage between the 16 answers or elements, and the response. We created three models using the data from the 47 of the 50 respondents, after removing the first vignette evaluated by each respondent (rationale – learning to answer), and after removing all vignettes requiring more than 9 seconds to evaluate (rationale – respondent probably multi-tasking, so the response time of 30–120 seconds represents the impact of the other task, and not a real measure of the specific vignette which is associated with the very long response time.) Three respondents were over the age of 30, and so we eliminated their analysis because they did not fit the age criteria. The input data for each regression comprises ALL of the data from the vignettes, the so-called ‘Grand Model.’

Table 3 shows the three columns of data. We look at the data with the following analytic point of view, based upon hundreds of previous studies.

Table 3. Performance of the elements by total panel.

|

|

Opti mistic

|

Pessi mistic

|

Resp

Time

|

|

Total Panel Results

|

Top2

|

Bot2

|

RT

|

|

Additive constant

|

12

|

10

|

NA

|

|

D1

|

U.S. offers economic development aid to create Middle East Institute of Competitive Excellence.

|

5

|

-2

|

0.6

|

|

D4

|

U.S. Jewish organizations reach out to support economic cooperation between Palestine and Israel.

|

2

|

-5

|

0.9

|

|

C2

|

Prime Minister Netanyahu said Israel will annex settlements in the West Bank.

|

2

|

0

|

0.7

|

|

B2

|

U.N. condemns the firing of rockets from Gaza into Israeli civilian areas

|

1

|

2

|

0.9

|

|

D2

|

U.S. groups approach Palestine with opportunity to work with Israel to create better economic conditions.

|

1

|

-2

|

0.7

|

|

C4

|

Thousands of Palestinians demonstrate along the Gaza border fence with Israel.

|

1

|

0

|

0.4

|

|

D3

|

U.S. creates Institute to help Palestinians become more entrepreneurial.

|

0

|

-2

|

0.7

|

|

C3

|

As U.S. peace plan rollout approaches, Palestinians voice rejection.

|

0

|

0

|

0.5

|

|

B1

|

The U.N. general assembly, has a permanent feature on its annual agenda titled “Human rights situation in Palestine & occupied Arab territories”.

|

-1

|

-1

|

1.0

|

|

A2

|

U.S. recognizes Israeli sovereignty over the disputed Golan Heights… strategic plateau Israel acquired after the Six-Day War.

|

-1

|

-2

|

0.7

|

|

A1

|

U.S. Embassy moves to Jerusalem from Tel Aviv.

|

-1

|

-1

|

0.5

|

|

A4

|

U.S. President Donald Trump say U.S. aid cuts aimed at pressuring the Palestinians to return to peace talks.

|

-2

|

-2

|

1.1

|

|

B4

|

Israel was the most condemned country at the U.N. in 2018, with the General Assembly passing at least 20 resolutions against Israel

|

-2

|

2

|

0.7

|

|

A3

|

U.S. passes Anti-Terrorism Clarification Act (ATCA)… ends U.S. funds to the West Bank & Gaza.

|

-3

|

-2

|

0.8

|

|

B3

|

Report from U.N. claims that Israeli security forces may have committed war crimes & should be held accountable for the deaths at protests in Gaza last year

|

-3

|

4

|

0.8

|

|

C1

|

Israel says protests, described by Gazans as the Great March of Return, are particularly violent… could act as a cover for Hamas, to infiltrate Israel, carry out attacks.

|

-3

|

0

|

0.8

|

- The additive constant: The OLS program estimates the additive constant, and the coefficient for each element. When we create the model with Top2 (Positive Outcome), the additive constant shows the conditional probability of a rating to the vignette being 8 or 9, albeit in the ‘absence of elements.’ In turn, when we create the model with Bot2 (Negative Outcome), the additive constant shows the conditional probability of a rating to the vignette being 1 or 2. We know for a fact that all vignettes comprised a minimum of two and a maximum of four elements, since the design specifies those specific combinations. Thus, the additive constant is an estimated parameter interpreted as ‘what would happen in the absence of elements.’ The additive constants are low for both positive and negative outcomes, 12 and 10, respectively. We interpret the low additive constants as meaning that in the absence of elements, the respondents simply don’t feel that anything will happen. Despite the rhetoric of interested parties, our young respondents don’t feel that anything of significant positive or negative will happen. It’s going to be all in the specifics, if positive or negative outcomes are to happen at all.

- The strongest positive element (Top2.): Positive, high-scoring elements for Top2, represent the respondent’s belief that the action stated by the element will lead to a positive, peaceful outcome. We look for elements of 8 or higher, based upon similar types of studies in the past. When an element generates a coefficient of +8 or higher, it often covaries with other things or events in the ‘outside world.’ The number ‘+8’ is not absolute, but rather a convenient level. Our data in Table 3 from the total panel suggest only one element which even comes near the value, +8. This is element D1, ‘U.S. offers economic development aid to create Middle East Institute of Competitive Excellence.’ That ‘strong performing element,’ at least within the context of this experiment, generates a coefficient of +5.

- The strongest negative element (Bot2): Positive, high-scoring elements for Bot2, represent the respondent’s belief that the action stated by the element will lead to a negative, combative outcome. Following the same logic as above (#2), we look for an element which generates a coefficient of +8 or higher on Bot2. The only element which does even modestly is B3, Report from U.N. claims that Israeli security forces may have committed war crimes & should be held accountable for the deaths at protests in Gaza last year. The coefficient, however, is only +4.

- The most engaging elements: The model for response time (RT) does not have an additive the constant. The rationale is the response time is meaningless without elements. There are no norms from experience for response time, the technology having only been introduced in late 2018. The list below shows those elements requiring 0.9 seconds or longer to ‘process,’ based upon the grand model relating response time to the presence/absence of elements.

U.S. President Donald Trump say U.S. aid cuts aimed at pressuring the Palestinians to return to peace talks.

The U.N. General Assembly has a permanent feature on its annual agenda titled “Human rights situation in Palestine & occupied Arab territories”.

U.S. Jewish organizations reach out to support economic cooperation between Palestine and Israel.

U.N. condemns the firing of rockets from Gaza into Israeli civilian areas

When we break out the respondents by gender, we find the following:

Optimism (Top2)

- The additive constant is slightly higher for females than for males (16 versus 10), which at the low end of the scale might signal that females are slightly more optimistic, but neither gender can be labelled ‘optimistic’.

- In terms of elements, males are very optimistic regarding the prospect of formal efforts to increase economic cooperation and growth, especially the new idea of a Middle East Institute of Competitive Excellence. Surprisingly, females don’t feel optimistic in the face of stated efforts for economic growth.

Pessimism (Bot2)

- The additive constants are low for both genders, 9 for males and 12 for females, suggesting no real innate pessimism, just like no real innate optimism.

- No elements drive pessimism

The engaging elements from response time

- For males a focus on direct efforts to help economics, and the focus on human rights

U.S. creates Institute to help Palestinians become more entrepreneurial.

U.S. President Donald Trump say U.S. aid cuts aimed at pressuring the Palestinians to return to peace talks.

The U.N. General Assembly has a permanent feature on its annual agenda titled “Human rights situation in Palestine & occupied Arab territories”.

- For females a focus on direct efforts, involving a person (either PM Netanyahu or Pres. Trump)

Prime Minister Netanyahu said Israel will annex settlements in the West Bank

U.S. President Donald Trump say U.S. aid cuts aimed at pressuring the Palestinians to return to peace talks.

Uncovering the deeper structure of mind-set and the emergence of two new groups.

A key tenet of Mind Genomics is that for any topic area in which human judgment is involved, there are often different ways of perceiving and judging that which is presented. That is, people are not necessarily uniform in terms of their criteria. The Latin proverb, here translated, epitomizes the world-view of Mind Genomics: Of taste one does not dispute.

In order to uncover the different viewpoints, or mind-sets, it may be as simple as clustering the respondents based upon the pattern of coefficients, generally without the additive constant. Clustering is a well-accepted technique in statistics, a procedure to assign items into an exhaustive set of mutually exclusive groups, the aforementioned clusters. These non-overlapping clusters are created according to string mathematical criteria. It is left to the discretion of the researcher to choose the method of clustering and, after the statistics have been calculated, to select the number of clusters and to name them.

Clustering is mathematical, but we are faced with many different ways to cluster a group of test objects, such as people. We must look at clustering as a heuristic, helping us make sense of the data, and not prescribing the absolute truth. For Mind Genomics, the clustering algorithm as of this writing (2019), comprises the calculation of a distance between pairs of people, putting people in different clusters, and then trying to interpret the meaning of the cluster, if there is a story to be told.

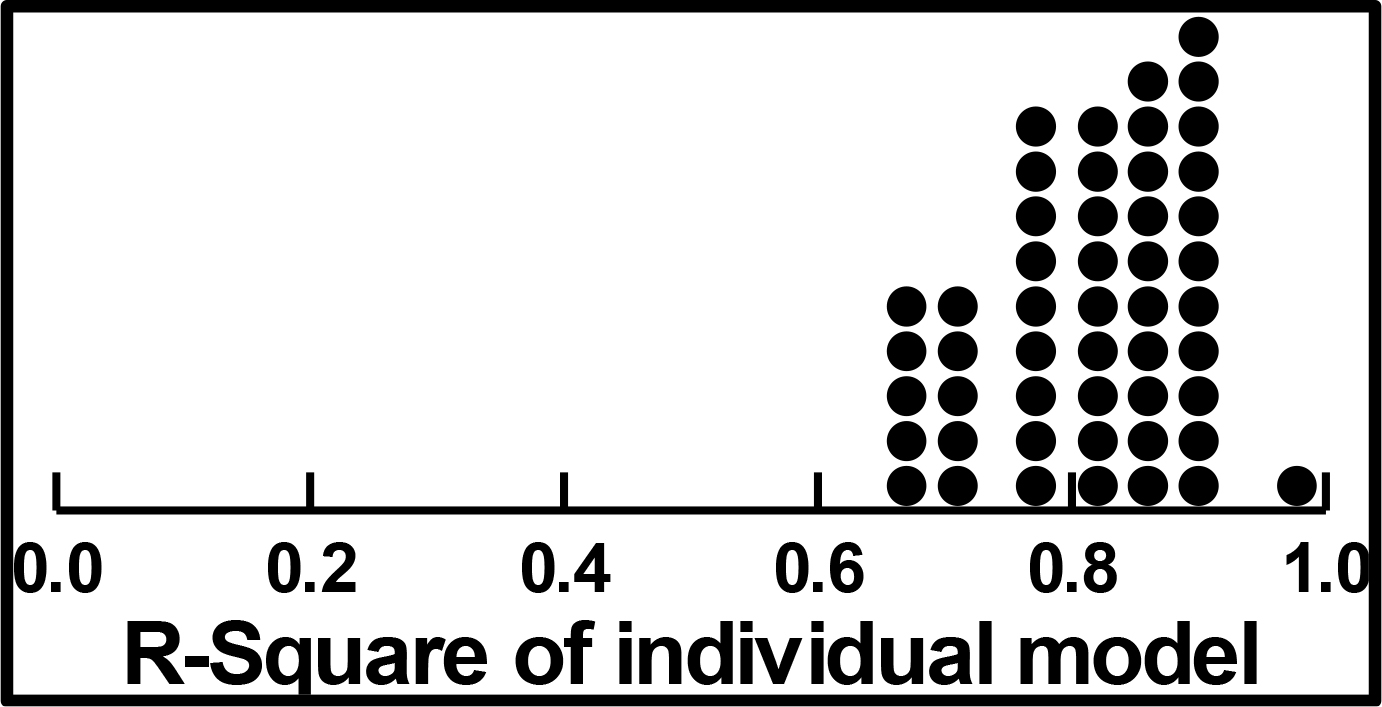

The clustering procedure used here involved the creation of 47 models relating the presence/absence of the 16 to the binary value, Top2, one model or equation for each of the 47 respondents who were under 30. (The other three respondents were excluded entirely from the analysis.). The equation was estimated using all 24 vignettes evaluated by the respondent, because the underlying experimental design is set up to allow the estimation of the individual models when all 24 vignettes are used as cases in the regression model. That is, we included all vignettes, removing no vignette at all.

The OLS regression returned with an additive constant and 16 coefficients for each respondent. We used the 16 coefficients as input to the k-means clustering, defining the distance between any pair of respondents as (1-Pearson R). The Pearson R or correlation coefficient defines the degree of linear relation between two sets of objects. The k-means clustering put the 47 respondents into two clusters, attempting to maximize the distance between the two centroids (average coefficient for each element by group) and minimize the distance between pairs of respondents within the cluster.

The average coefficients for the two clusters or mind-sets appear in Table 5. The clustering was done on the Top2, the causes for optimism, but the table shows the results for Top2 (optimistic outcome), Bot2 (pessimistic outcome), and response time. The coefficients are sorted by the strong performers for the two mind-sets.

Table 4. Performance of the elements by gender.

|

|

M

|

F

|

M

|

F

|

M

|

F

|

|

By Gender

|

Optimistic

TOP2

|

Pessimistic

BOT2

|

Response Time

|

|

Additive constant

|

10

|

16

|

9

|

12

|

NA

|

NA

|

|

D1

|

U.S. offers economic development aid to create Middle East Institute of Competitive Excellence.

|

12

|

-2

|

-4

|

0

|

0.7

|

0.6

|

|

D4

|

U.S. Jewish organizations reach out to support economic cooperation between Palestine and Israel.

|

6

|

-3

|

-5

|

-4

|

0.9

|

0.9

|

|

A1

|

U.S. Embassy moves to Jerusalem from Tel Aviv.

|

-7

|

4

|

1

|

-3

|

0.7

|

0.2

|

|

C2

|

Prime Minister Netanyahu said Israel will annex settlements in the West Bank.

|

1

|

3

|

2

|

-3

|

0.4

|

1.1

|

|

C4

|

Thousands of Palestinians demonstrate along the Gaza border fence with Israel.

|

1

|

1

|

4

|

-6

|

0.2

|

0.5

|

|

C3

|

As U.S. peace plan rollout approaches, Palestinians voice rejection.

|

0

|

1

|

3

|

-4

|

0.4

|

0.6

|

|

A2

|

U.S. recognizes Israeli sovereignty over the disputed Golan Heights… strategic plateau Israel acquired after the Six-Day War.

|

-2

|

0

|

0

|

-5

|

0.6

|

0.8

|

|

C1

|

Israel says protests, described by Gazans as the Great March of Return, are particularly violent… could act as a cover for Hamas, to infiltrate Israel, carry out attacks.

|

-7

|

0

|

1

|

-1

|

0.7

|

0.8

|

|

B2

|

U.N. condemns the firing of rockets from Gaza into Israeli civilian areas

|

2

|

-1

|

0

|

4

|

0.9

|

0.8

|

|

A3

|

U.S. passes Anti-Terrorism Clarification Act (ATCA)… ends U.S. funds to the West Bank & Gaza.

|

-4

|

-2

|

0

|

-5

|

0.7

|

0.9

|

|

D2

|

U.S. groups approach Palestine with opportunity to work with Israel to create better economic conditions.

|

4

|

-3

|

-3

|

-1

|

0.8

|

0.7

|

|

D3

|

U.S. creates Institute to help Palestinians become more entrepreneurial.

|

2

|

-3

|

0

|

-3

|

1.0

|

0.3

|

|

A4

|

U.S. President Donald Trump say U.S. aid cuts aimed at pressuring the Palestinians to return to peace talks.

|

-1

|

-3

|

1

|

-6

|

1.2

|

1.1

|

|

B4

|

Israel was the most condemned country at the U.N. in 2018, with the General Assembly passing at least 20 resolutions against Israel

|

-1

|

-4

|

2

|

3

|

0.5

|

0.9

|

|

B3

|

Report from U.N. claims that Israeli security forces may have committed war crimes & should be held accountable for the deaths at protests in Gaza last year

|

-1

|

-5

|

5

|

3

|

0.7

|

0.8

|

|

B1

|

The U.N. general assembly, has a permanent feature on its annual agenda titled “Human rights situation in Palestine & occupied Arab territories”.

|

4

|

-6

|

-1

|

-1

|

1.2

|

0.7

|

Table 5. Performance of the elements by mind-set.

|

|

MS1

|

MS2

|

MS1

|

MS2

|

MS1

|

MS2

|

|

By Two Mind Sets

MS1 = Actions of any organized type will bring less unrest, more hope

MS2 = Economic development will bring less unrest, more hope

|

Optimistic Top2

|

Pessimistic Bot2

|

Response Time

|

|

Additive constant

|

13

|

10

|

7

|

14

|

NA

|

NA

|

|

Elements driving Mind-Set 1 – Actions of any organized type will bring less unrest more hope

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

C2

|

Prime Minister Netanyahu said Israel will annex settlements in the West Bank.

|

5

|

-1

|

-4

|

3

|

0.4

|

1.1

|

|

C4

|

Thousands of Palestinians demonstrate along the Gaza border fence with Israel.

|

5

|

-4

|

-3

|

3

|

0.4

|

0.4

|

|

Mind-Set 2 – Economic development will bring less unrest, more hope

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

D1

|

U.S. offers economic development aid to create Middle East Institute of Competitive Excellence.

|

1

|

10

|

2

|

-7

|

0.4

|

1.0

|

|

D2

|

U.S. groups approach Palestine with opportunity to work with Israel to create better economic conditions.

|

-4

|

8

|

1

|

-6

|

0.7

|

0.8

|

|

D4

|

U.S. Jewish organizations reach out to support economic cooperation between Palestine and Israel.

|

-1

|

6

|

-2

|

-8

|

0.7

|

1.2

|

|

Does not drive responses of either mind-set

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

A1

|

U.S. Embassy moves to Jerusalem from Tel Aviv.

|

-4

|

3

|

-2

|

1

|

0.9

|

-0.1

|

|

A4

|

U.S. President Donald Trump say U.S. aid cuts aimed at pressuring the Palestinians to return to peace talks.

|

-5

|

3

|

-2

|

-2

|

1.3

|

0.8

|

|

B2

|

U.N. condemns the firing of rockets from Gaza into Israeli civilian areas

|

0

|

2

|

1

|

3

|

0.9

|

0.9

|

|

B1

|

The U.N. general assembly, has a permanent feature on its annual agenda titled “Human rights situation in Palestine & occupied Arab territories”.

|

-2

|

2

|

1

|

-3

|

0.7

|

1.2

|

|

D3

|

U.S. creates Institute to help Palestinians become more entrepreneurial.

|

-2

|

2

|

0

|

-5

|

0.9

|

0.6

|

|

A2

|

U.S. recognizes Israeli sovereignty over the disputed Golan Heights… strategic plateau Israel acquired after the Six-Day War.

|

-3

|

2

|

-2

|

-2

|

1.0

|

0.3

|

|

B4

|

Israel was the most condemned country at the U.N. in 2018, with the General Assembly passing at least 20 resolutions against Israel

|

-1

|

-2

|

2

|

3

|

0.7

|

0.7

|

|

A3

|

U.S. passes Anti-Terrorism Clarification Act (ATCA)… ends U.S. funds to the West Bank & Gaza.

|

-3

|

-2

|

-2

|

-2

|

0.8

|

0.7

|

|

B3

|

Report from U.N. claims that Israeli security forces may have committed war crimes & should be held accountable for the deaths at protests in Gaza last year

|

-3

|

-2

|

6

|

2

|

0.7

|

0.9

|

|

C3

|

As U.S. peace plan rollout approaches, Palestinians voice rejection.

|

3

|

-3

|

-2

|

2

|

0.4

|

0.7

|

|

C1

|

Israel says protests, described by Gazans as the Great March of Return, are particularly violent… could act as a cover for Hamas, to infiltrate Israel, carry out attacks.

|

0

|

-7

|

-2

|

2

|

0.7

|

0.9

|

The two mind-sets are defined by the strongest performing elements:

- MS1 = Actions of any organized type will bring less unrest, more hope

- MS2 = Economic development will bring less unrest, more hope

What emerges as very important are those

- The two mind-sets have low basic optimism

- Mind-set 1, looking for definitive ‘action’ of any type to bring hope, feels almost nothing will work

- Mind-set 2, looking for economic development, shows a real hope for simple economic actions, even symbolic but real attempts.

Finding these mind-sets in the population through the PVI (personal viewpoint identifier)

The data suggest little basic optimism or pessimism, whether by gender or even by mind-set. The level of rhetoric surrounding the situation in the Middle East is not basically relevant. The low additive constants and the short response times attest to that basic level of disinterest. Yet, despite this discouraging initial finding, the existence of a pair of mind-sets suggests that this disinterest can be turned to more productive interest. Perhaps the first mind-set, those who want action of any sort, cannot be satisfied with destabilizing the region. It is hard to change governments and impossible to change history. The second mind-set, however, is easier to excite. They want concrete symbols and actions to drive economic development. Perhaps, for example, an effort to create this ‘MEICE’ might work, this Middle East Institute of Competitive Excellence, may work. Author Moskowitz has presented the idea to different countries

(https://www.dropbox.com/s/yhfncfid6b8nmjf/Economic%20Growth%20%20%20Middle%20East%20Institute%20Of%20Competitive%20Excellence.pdf?dl=0.)

Unlike the information about age and gender, people may or may not know the mind-set to which they belong for a specific topic. We know from these data that the mind-sets distribute about equally across genders, and across the self-defined ‘position’ or ‘interest’ in the topic (Table 6.) Furthermore, Table 6 shows us that despite the mind-sets, there is an exceptional level of disinterest.

Table 6. Distribution of the two mind-sets across gender and across self-declared nature of interest in the topic.

|

Gender

|

MS1 – Action

|

MS2-Development

|

Total

|

N

|

|

Male %

|

50

|

57

|

53

|

25

|

|

Female %

|

50

|

43

|

47

|

22

|

|

Total %

|

100

|

100

|

100

|

|

|

N

|

26

|

21

|

|

47

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Self- declared attitude to the topic

|

MS1 – Action

|

MS2-Development

|

Total

|

N

|

|

Palestine is right %

|

23

|

19

|

21

|

10

|

|

Israel is right %

|

12

|

5

|

9

|

4

|

|

Both are right %

|

15

|

24

|

19

|

9

|

|

Not interested %

|

27

|

14

|

21

|

10

|

|

Not applicable %

|

23

|

38

|

30

|

14

|

|

Total %

|

100

|

100

|

100

|

|

|

N

|

26

|

21

|

|

47

|

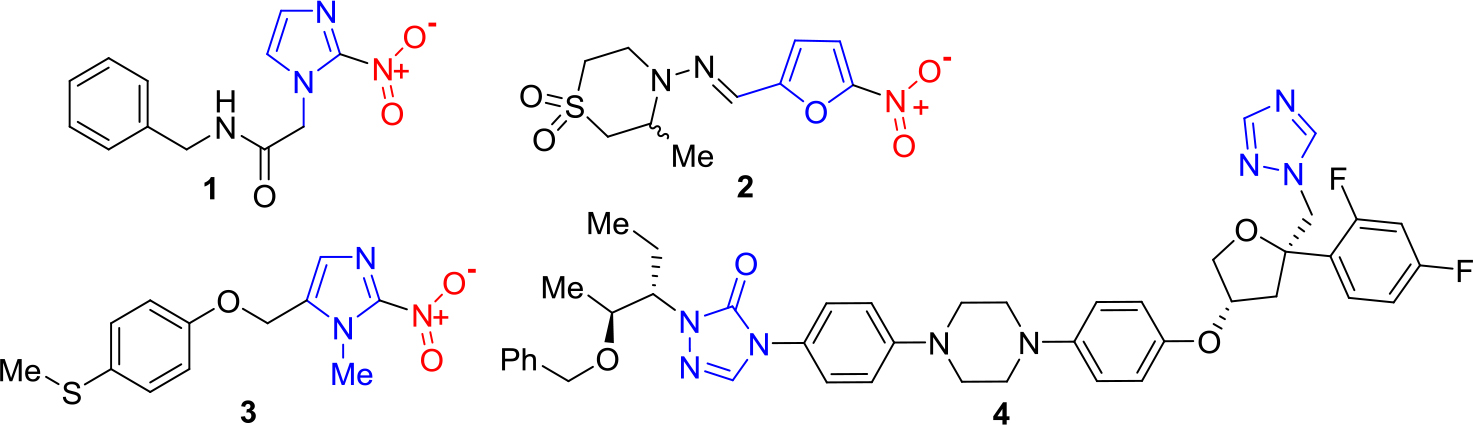

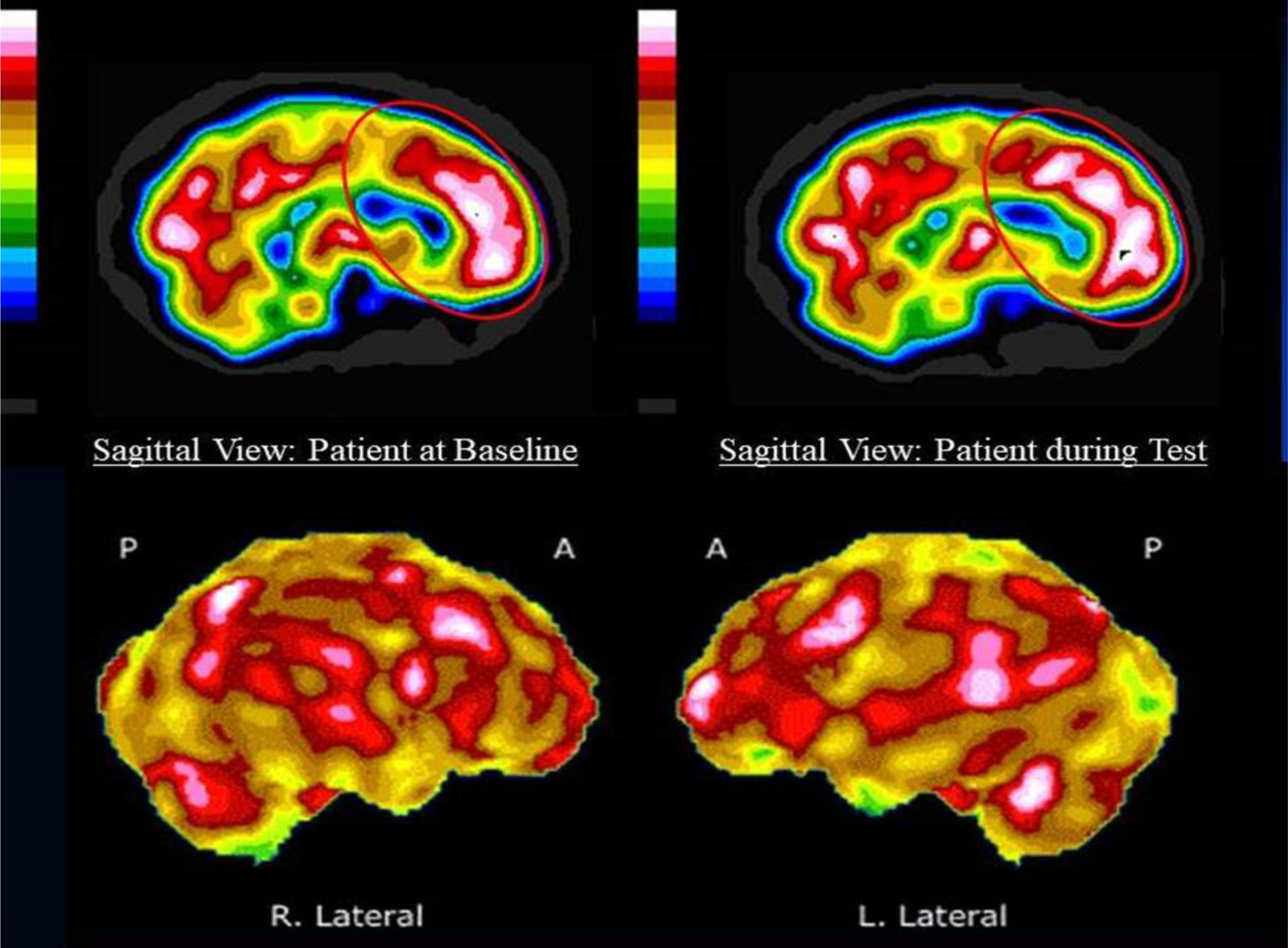

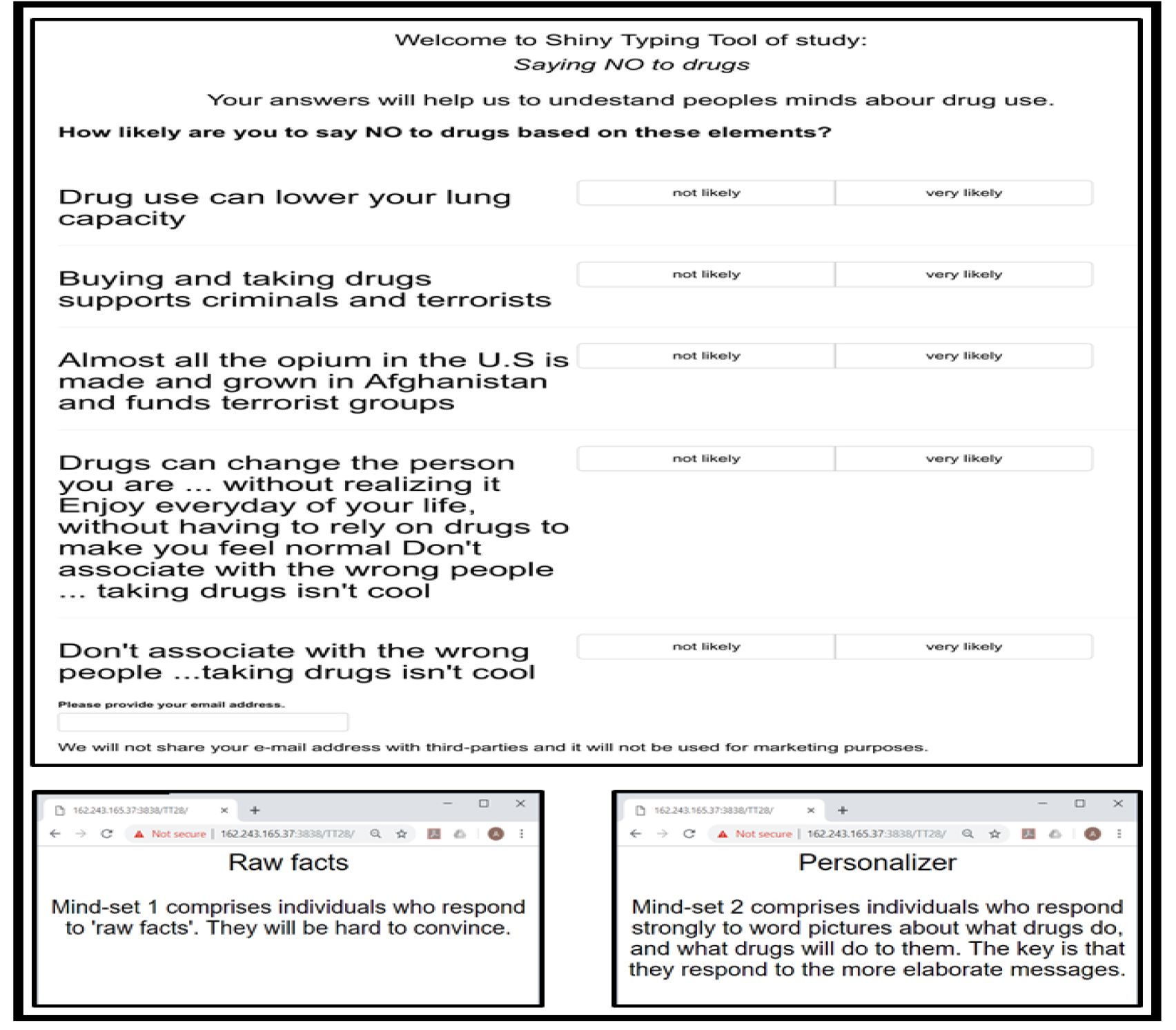

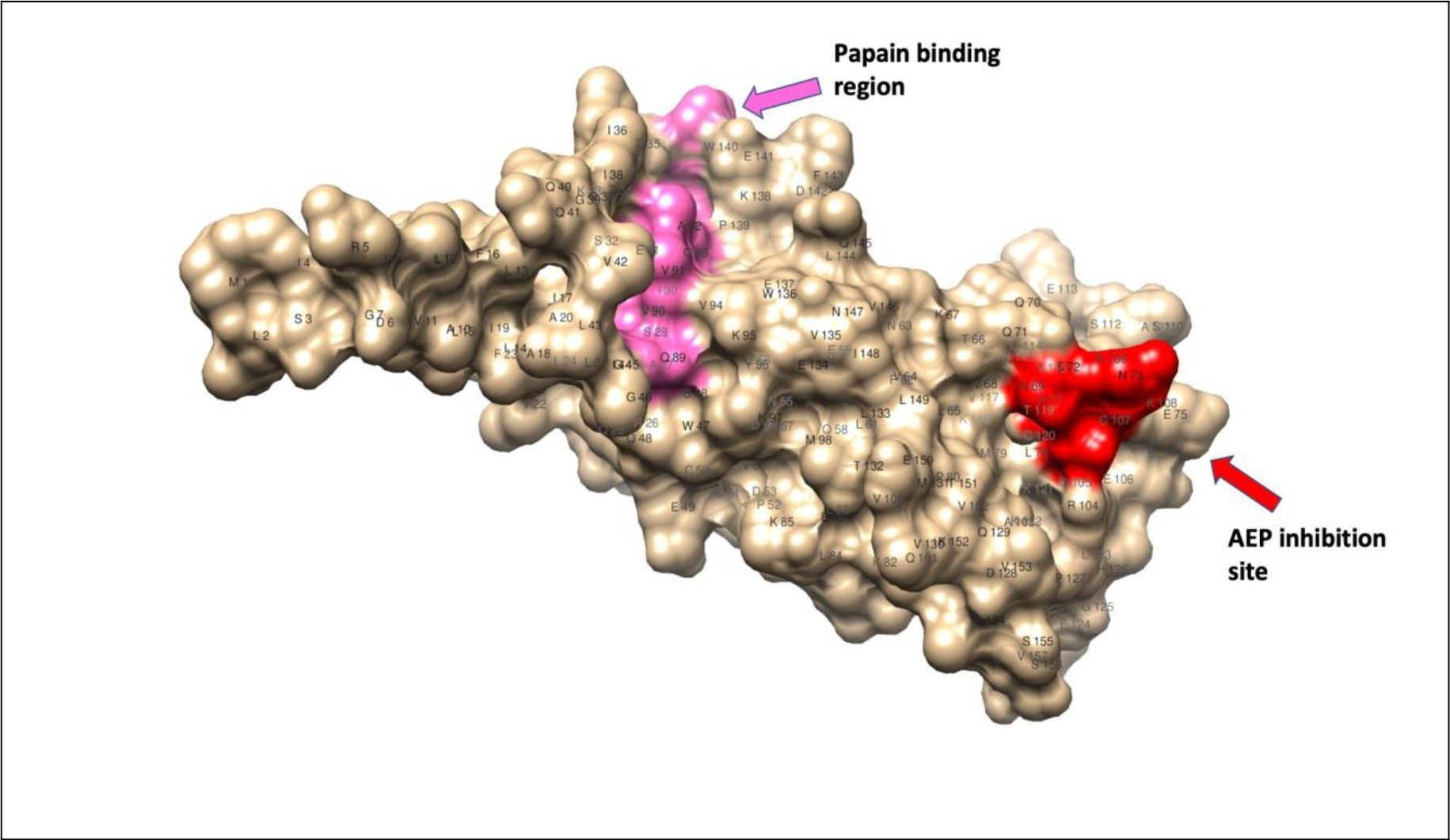

The PVI is constructed by considering the elements which best ‘separate’ the two segments. Figure 4 shows the PVI for this study, as well as the feedback which comes to the respondent. The actual PVI as of this writing (April, 2019) resides at the following website: http://162.243.165.37:3838/TT25/

Figure 4. The PVI for the study of young Americans towards the policy pronouncements about the Middle East, specifically Palestine and Israel.

Discussion and Conclusion

What we learn about the young people

As we noted in the introduction to this paper, one need only look at the media, at the United Nations activities, at the popular pro-Palestinian movements such as BDS (Boycott, Divest, Sanction) SJP (Students for Justice in Palestine) to think that the situation is the Middle East is intractable. For all the efforts to stir up excitement, however, our data suggest that most of the young people whom we sampled simply don’t care. That is, they don’t expect much, neither in the way of peace and hope, nor hostilities and despair.

Yet, despite the apparent disinterest, when we probe deeper through Mind Genomics, we uncover two groups, two different mind-sets. Mind-Set 1 believes that peace and hope will come through definitive action on either side, perhaps believing that the status quo should be maintained. These are the ones who believe in the strength of power, Realpolitik. Mind-Set 2 believes that hope will be nurtured through direct economic help, help which gives to those of both sides in the Middle East an opportunity to grow their nations. To this end, the notion of a MEICE, the Middle East Institute of Competitive Excellence, makes sense. The structure and activities of that proposed idea are given in a link.

One might dismiss the findings by saying that the data are from a small sample. The reality of Mind Genomics is that it does not measure people per se, but like the science of color, established the basic colors (red, yellow, blue.) All ‘things’ with color comprise a certain percent of the primaries, yellow, red, and blue, adding up to 100%. A colorimeter is used to deconstruct the color of a ‘something’ into the percent of red, yellow, and blue, the primaries. In turn, the colorimeter becomes a tool to ‘measure the world,’ after the color science has been established. In the same way, our data suggests for this micro-topic the existence of two mind-sets, two ‘primaries,’ those interested in power as a stabilizer, and those interested in economic growth as a stabilizer. One can then use the PVI for this study to understand the feeling of people world-wide. The PVI provides a modern tool to understand the distribution of these mind-sets among the people of the world, because the Mind Genomics effort simply provided the science and the tool. This notion of basic primaries is not new, not original to this paper, having been recognized more than 15 years ago, and undoubtedly far earlier [12,13].

The role of experimentation in counterfactual history

A new and growing area of interest in the social sciences is the discipline of counterfactual history. The Mind Genomics approach we present here for policy fits right in with the notion of creating alternative narratives of what happened or what could happen, presenting these narratives, and getting responses. Most of the efforts are qualitative, teaching people to have a more critical way of thinking. Mind Genomics allows the creation of a systematic body of work for counterfactual history, teaching us both what could have been, and how people react to what could have been. Perhaps by institutionalizing the teaching of counterfactual history, one might excite an otherwise disinterested generation in understanding the ‘realpolitik’ of today [14].

References

- De Boer C (1983) The Polls: Attitudes Toward the Arab-Israeli Conflict. The Public Opinion Quarterly 47: 121–131

- Eit-Hallahmi BB (1972) Some psychosocial and cultural factors in the Arab-Israeli conflict: A review of the literature. Journal of Conflict Resolution 162: 269–280.

- Spiegel SL (1986) The Other Arab-Israeli Conflict: Making America’s Middle East Policy, from Truman to Reagan Vol. 1. University of Chicago Press.

- Vatikiotis PJ (2016) Conflict in the Middle East reissue of 1971 volume, Routledge, eBook ISBN9781317206323.

- Kahneman D and Egan P (2011) Thinking, fast and slow. New York: Farrar, Straus and Giroux.

- Green PE, Srinivasan V (1990) Conjoint analysis in marketing: new developments with implications for research and practice. The Journal of Marketing 54: 3–19.

- Moskowitz HR, Gofman A (2007) Selling blue elephants: How to make great products that people want before they even know they want them. Pearson Education.

- Pang B, Lee L (2008) Opinion mining and sentiment analysis. Foundations and Trends® in Information Retrieval 21–2, 1–135.

- Box, G.E., Hunter, W.G. & Hunter, J.S., 1978. Statistics for experimenters, New York, John Wiley.

- Moskowitz H, Gofman A, I novation Inc (2003) System and method for content optimization. U.S. Patent 6,662,215.

- Gofman A and Moskowitz HR (2010) Isomorphic permuted experimental designs and their application in conjoint analysis. Journal of Sensory Studies 25: 127–145.

- Alwin DF, Krosnick J A (1991) Aging, cohorts, and the stability of sociopolitical orientations over the life span. American Journal of Sociology 97: 169–195

- Atkeson L R, Rapoport R B (2003) The more things change the more they stay the same: Examining gender differences in political attitude expression, 1952–2000. Public Opinion Quarterly 67: 495–521.

- Mordhorst M (2008) From counterfactual history to counter-narrative history. Management & Organizational History 31: 5–26.