Abstract

Objective: Breathing difficulties are abundant throughout the whole population spectrum. Breathing pattern dysfunctions are frequent despite the fact that correct breathing is a necessary prerequisite for optimal functioning of the musculoskeletal apparatus, correct body posture and mental well-being. Furthermore, good breathing ventilation is immensely important in endurance sports. The quality of breathing stereotype also influences vital lung capacity. Incorrect breathing can be caused by blocked ribs and vertebra, dysfunction of breathing and stabilisation muscles, allergies, lung diseases, heart failure and above all excessive stress. When stimuli causing unsuitable breathing stereotype prevail too long, the dysfunction becomes fixated and must be eliminated and consciously corrected (using compensation exercises).

Methods: In this research, muscle dynamometer MD03 was utilised for examination of the breathing stereotype, followed by Spirometric measurements of forced exhalation of the vital capacity and exhalation volume values for 1 second. Two months intervention of targeted breathing exercises was applied on a group of adolescent athletes (19 individuals contributing to the intervention and 18 used as a control group) aged on average 17.26 ± 1.80.

Results: Factual as well as statistically significant influence on the involvement and strengthening of breathing muscles activated during diaphragmatic breathing at rest, as well as during deep breathing was shown. Improved values of FVC (forced expiratory vital capacity) by 6 % from 4.51 ± 1.13 L to 4.78 ± 1.12 L were obtained together with improved FEV1 (the forced expiratory volume in 1 second) by 6.1 % from 3.54 ± 0.71 L.s-1 to 3.76 ± 0.66 L.s-1. Both changes are both factually and statistically significant although the factual change displays only a slight effect. Only minimal change could be sees for the control group where FVC increased by 0.45 % and FEV1 by 0.86 %. The test group also showed significant increase in breathing volumes.

Conclusion: This study has confirmed that a two-month intervention of targeted breathing exercises has both factually and statistically significant influence on the activation and strengthening of breathing muscles.

Keywords

breathing pattern, breathing exercises, posture, spirometry, vital capacity

Introduction

Dysfunctions of the breathing pattern can be first indicators of a problem within the human body, be it of mechanical, physiological or mental kind [1]. Incorrect breathing can be caused by blocked ribs or vertebra, dysfunction of breathing and stabilising muscles, allergies, lung diseases, heart failures and above all excessive stress. Major role also belongs to a change in posture control [2] or changed dynamic spine stabilisation [3]. The breathing process is perfectly coordinated and controlled by the brainstem and medulla oblongata [4]. Breathing movements happen automatically, induced by the autonomous nerves, although the depth and rhythm of the breathing can be consciously regulated. This otherwise spontaneous activity can thus be influenced by will [5, 6]. Breathing and breathing movements maintain not only the fundamental metabolic processes connected to gas exchange but they also strongly influence body posture [7]. This implies that breathing influences posture stability while at the same time the quality of postural stability influences breathing. According to Kolář et al. [8] postural stability is defined as the ability to maintain upright body posture and at the same time have the ability to react on changed external and internal forces so as to prevent an unintentional or uncontrolled fall. Dylevský, Druda and Mrázková [9] describe postural stability as a balanced and coordinated posture of the body as a unit and as a highly specialised process of maintaining body balance and position of the body and its parts in a constantly changing environment. It is a musculoskeletal regulatory body mechanism that precedes every movement and afterwards seeks to maintain the reached position. It is therefore not a simple taking of a position but a continuous maintaining of its stability [8]. Furthermore, breathing movements are influenced not only by internal and external environment but also by the state of mind. While happiness undermines extensive body posture and increases breathing movements, sadness and depression are exhibited by flexed body posture and hindrance of breathing movements [10].

Breathing movements are divided into three areas, namely abdominal, lower thoracic or diaphragmal and upper thoracic or subclavian. The thoracic breathing movements differ by the distinctive activation of the ribs in the given areas. Breathing movements go through rhythmical interchanging activity of the breathing muscles in dependence on the physical activity and the stress condition of the organism, with simultaneous activation of the axial organ muscles. Breathing muscles are further divided according to their anatomic function into primary and accessory inhalation and primary and accessory exhalation muscles with the most important breathing muscle being m. diafragma (the diaphragm) [8, 10]. During inhalation both the diaphragm and mm. intercostales externi compress. Muscle fascicles of the diaphragm are concentrically contracted causing pressure on the content of the abdominal cavity from above. This pressure is further transferred to the pelvic area, and in order to avoid prolapse of the abdominal organs the muscles of the pelvic area start contracting concentrically together with the diaphragm. These two muscle units then work as a sort of pistons working against each other from below and above forcing the content of abdominal cavity toward the remaining directions – forward and to the sides, respectively backwards. The relatively large area of the diaphragm induces an increase of the internal abdominal pressure while at the same time the lumbar spine area is heavily compressed using the function of the transverse abdominal muscle that is eccentrically activated and thus hinders the content of the abdominal cavity to move forward and to the sides causing the circumference of the waist to enlarge. On the other hand, the tendency of the abdominal cavity to move backwards during inhalation is for the majority of postural situations minimal [8, 11].

Simultaneously, the diaphragm is an important muscle for the postural function [4], with up to 75% of the volume change of the intrathoracic space during quiet breathing being caused by diaphragm function while its function alone is sufficient for 2/3 of the lung vital capacity [8]. The range of diaphragm movement is 1–2 cm during quiet breathing and up to 10 cm during heavy breathing which activates even the external intercostal muscles. Furthermore, during extreme breathing also the auxiliary respiratory muscles get activated which help to lift the first and second ribs together with sternum [12].

Clifton-Smith and Rowley [1] define dysfunction of the breathing stereotype as disproportionate breathing which is sufficient for the utterance of given symptoms even with no organic causes. Without such structural causes the dysfunction stems from muscular dysbalances, functional disorders of the muscular-skeletal system, that lead to ineffective breathing. This in its turn then induces muscular adaptational mechanisms towards the outside influences. Muscular dysbalance usually evolves due to a disturbed muscular synergy when one antagonistic muscle gains dominance over its counterpart. The cause of muscular imbalance can be even a remote dysfunction, such as reflexive change in a muscle that causes pain or influence other connected muscles which in its turn causes the organism toward an antalgic body posture not ideal for movement stereotypes [10, 11]. Therefore when trying to influence breathing functions it must be taken into consideration that the breathing and muscular-skeletal systems must be approached as interconnected [8].

In order to assess breathing stereotype, several methods can be used such as palpation examination, whole-body plethysmography, chest skiagram, spirometry or usage of different instruments that are able to detect movement of individual segments of the respiratory system [13–15]. Involvement of the individual muscle segments can be determined for instance through a 3D system [16]. Kaneko and Horie [16] conducted such measurements using thirteen probes in different positions, during quiet and deep breathing and found connections between breathing movements and age, body posture and gender. Monitoring of breathing movements is enabled by measurements of chest circumference over meso-sternale and xipho-sternale junctions, evaluating and registering the difference between in- and exhalation [13]. Bockenhauer et al. [17] measured chest broadening using a measuring tape at two different levels (heights). The upper measurement of chest expansion was conducted at the level of the spinous process of the fifth thoracic vertebra and third intercostal space in the middle of the clavicle, while the lower measurement proceeded at the level of the spinous process of the tenth thoracic vertebra and the baseplate tip. Three different people measured maximal inhalation and maximal exhalation circumference at both levels and obtained thus a value of the chest expansion. This study confirmed the objectivity of examination chest movements in the middle and upper sectors of the rib cage using a tape measure [17]. Moll and Wright [18] used two separate techniques to measure the expansibility of the chest, using the calliper and using the tape measure at the fourth intercostal space with the arms of the patient raised above the head. They then concluded that circumference measurements alone should suffice. Burgos-Vargas et al. [19] also measured the expansiveness of the chest with a tape measure at the fourth intercostal space (arms raised). The activity of the breathing muscles during breathing cycle can also be investigated through polyelectromyography examination [14]. In order to learn about the strength of the breathing muscles even non-invasive methods of examination of maximum inhalation and exhalation mouth pressures can be used [20, 21]. The performance of breathing movements is denoted as the breathing wave. It begins with inhalation, proceeds from the lower over the medium to the upper sector. The exhalation wave on the other hand starts with lowering of the abdominal wall and simultaneous caudal lowering of the chest. Further, the sternum constricts and exhalation process is finished by activated abdominal muscles [10]. The importance of measurements of the chest expansion was confirmed by Bockenhauer et al. [17], and also Fisher, Cawley and Holgate [22].Their studies all showed the important connection between the chest expansion and vital capacity of the lungs. Effectivity of highly trained long distance runners is often limited by their breathing system. Spirometric examination of the static and dynamic ventilation parameters belong to basic methods for diagnosis of the respiratory system [23].

Change in the breathing stereotype is possible through active training of deep breathing, as agreed by Thomas and McIntosh [24] in their work. During such training it is necessary to monitor the breathing pattern of the examined individual and make him aware of its possible insufficiencies [4]. In order for the consequences of the training to start showing, the training must proceed for a certain time with a minimum of ten breathing exercises which evoke an important regular rhythm in the body. One such technique is isolated breathing, where three different types of breathing are practiced, namely diaphragmal, chest and subclavian breathing. The aim of diaphragm breathing is above all to realise its activity and learn to use it. The focus of chest breathing is then to gain increased flexibility of the rib cage, while subclavian breathing is meant to loosen the area of the neck and teach about the accessibility of the upper lobes of the lungs [6].Training exercise of at least six to eight weeks is necessary in order to be able to influence intermuscular coordination and improve intermuscular cooperation. Adaptational changes in the form of hypertrophy then appear after longer time, within months or years [25].

In both clinical and sporting practice vital capacity of the lungs is most often measured using the FVC test (basic forced volume vital capacity), where also the velocity of exhalation is determined, for instance for the time period of one second (FEV1), which also points to the strength of the exhalation muscles, an important and surveyed factors in endurance sports. Higher values of vital capacity (VC) can be reached through endurance training, although the values are also influenced by body constitution and size of the rib cage [26]. During long-term submaximal training inhalation muscles experience fatigue which is a limiting factor in endurance training. However, breathing exercises can enhance the efficiency of the breathing muscles. Endurance athletes usually have higher values of vital capacity, although their performance needs not be directly dependent on those. Highest values of VC have been determined for swimmers (up to 8 litres) which results from their breathing into the water and therefore against resistance. Adapted breathing is exhibited by a lower breathing work during same load in comparison to the unadapted. A certain amount of oxygen then remains for other purposes. As a consequence of endurance training the respiratory tract increases its ability to transport oxygen, which will also show during load. On the other hand, the maximum static and dynamic values remain basically unchanged. The aim of this work was to determine the influence of the intervention breathing exercises on the breathing stereotype and values of the forced volume vital capacity of the lungs [26].

Methodology

This study was conducted in the Laboratory of stress diagnosis, at the Department of Physical Education and Sports, Pedagogical faculty of the South Bohemian University. 37 individuals aged 17.26 ± 1.80 participated in this study, where each does endurance sport training six times a week; they are mostly mid-distance and long-distance runners. 19 individuals were involved in the intervention (ten females and nine males), while eighteen individuals functioned as a control group (nine females and nine males). The age of the females at the time of the study was 17.40 ± 2.01 years of age, with average weight 59.07 ± 6.70 kg and height 169.47 ± 4.04 cm. The age of the male group at the time of the research was 17.11 ± 1.52 years of age, average weight 60.47 ± 14.32 kg and height 176.40 ± 9.49 cm. Targeted selection was conducted based on the fact that endurance athletes are expected to have above-average breathing functions with strong connection to their performance. The aim of this research was to prove the influence of breathing exercises on the values of vital capacity of the lungs (VC) and on the quality of the breathing pattern. It was presumed that there will be a transfer of increased values of VC to values of breathing volume under load, which in its turn will influence endurance performance, which consecutive research will prove.

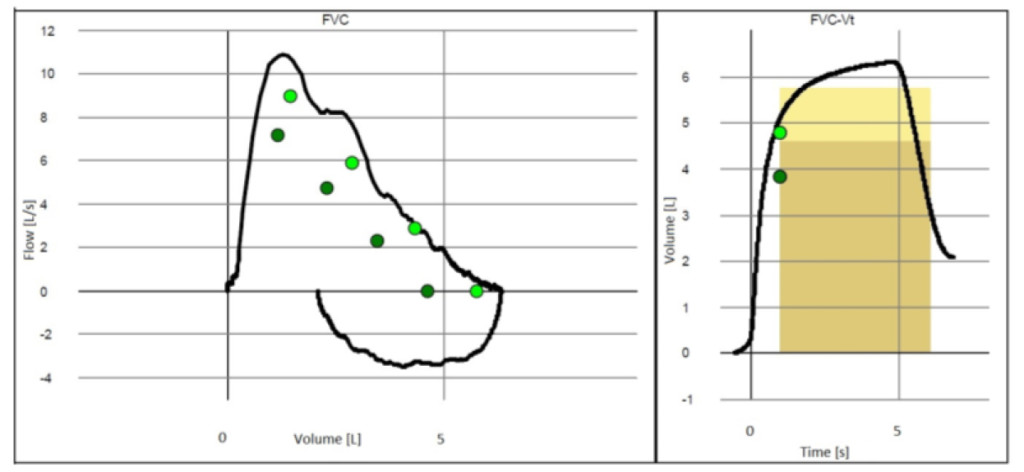

Vital capacity was measured using basic forced volume vital capacity test (FVC) as well as exhalation values under 1s (FEV1). Thereafter, the test group got instructions to conduct breathing exercises for two months, minimum five times a week for at least ten minutes. At the same time, once a week a common exercise session was organised at the end of running training session, where the execution of the exercises was checked and corrected. The tested individuals would each day take notes of the time of the exercises into a prepared table that they continuously checked in. After two months a re-test was conducted of all followed variables. Same measurements were simultaneously conducted for the control group. Test methodology was conducted according to the instrument instructions: after quiet inhalation and exhalation follows maximal inhalation and forced maximal exhalation. This procedure is repeated three times and the best result is registered. The instrument registers if sufficient force and necessary length of exhalation were used. If the parameters of the test were insufficient, the experiment was not registered and experiment needed to be repeated. The FVC test was conducted in upright position with Spirometer Otthon instrument, while the evaluation was conducted using ThorSoft program. Figure 1 shows the development of the breathing curve as registered by the spirometer instrumentation.

Muscle dynamometer was used for the examination of breathing stereotype [27–30]. Due to the ability of the muscle dynamometer to register movement dynamics, it is possible to use it to monitor the dynamics of the breathing function. Breathing analysis is based on the concept of three sectors (parts) of the chest and therefore three measuring sensors were also used. The exact positions for placing the sensors were chosen based on the kinematics of the mentioned chest sectors [9].The lower chest sector (abdominal) is found below apertura thoracis inferior. Anatomically the abdominal muscles and their initiations on the cartilaginous parts of the false ribs and the breast bone participate in the build-up of this part of the chest. The correct spot for the first sensor is then on the ventral side at level of L4–5. For the central sector of the chest the correct placement is on the thoracic spine limited by the area between Th6-Th12 and the fifth to twelfth rib. The sensor for this sector was placed on the level of 8–9 rib on the ventral side just below the sternum. The upper chest sector (apical) spreads from C4 to Th3–4 to the upper aperture and the fifth rib. The third sensor was placed on the level of 3 to 4 rib on the ventral side in the area of the sternum. Movements of the thoracic spine sector influence the dynamics of breathing, while breathing will influence dynamics of the spine [8].The test of breathing dynamometry is conducted in the upright body position as this position is physiological for breathing [4]. The dynamometer instrument can register activation of the breathing muscles, as it measures immediate values of force activity of the muscles as a function of time. Both the strength and dynamics of the muscle force can be evaluated. Through the sensors the lifting of individual segments during quiet breathing for one minute and during deep breathing for one minute was monitored. During data analysis ten inhalations and exhalations was averaged. The test group trained the breathing exercises for eight weeks. The intervention program was focused on isolated breathing in different positions, training for the breathing wave, full breathing and rhythmical breathing. Full breathing was also trained in accordance with movements during short dynamical sets of exercises [31–33]. After input measurements, the test group was introduced to breathing exercises and their training was conducted under expert supervision. The test group was asked to conduct the given exercises at home at least five times a week for at least ten minutes. Once a week a mutual training session was organised, after running training session, where the exercises were checked and corrected by expert supervisor. An output examination similar to the input one was conducted. The control group did not do any breathing exercises. For evaluation of the collected data these tests were used: the determination of the effective significance Cohen’s d test for determination of practical significance and Student‘s paired t-test for dependent samples. The level of significance was determined based on α = 0.05. Data analysis was conducted using Microsoft Excel 2016 and Statistica 12.

Results

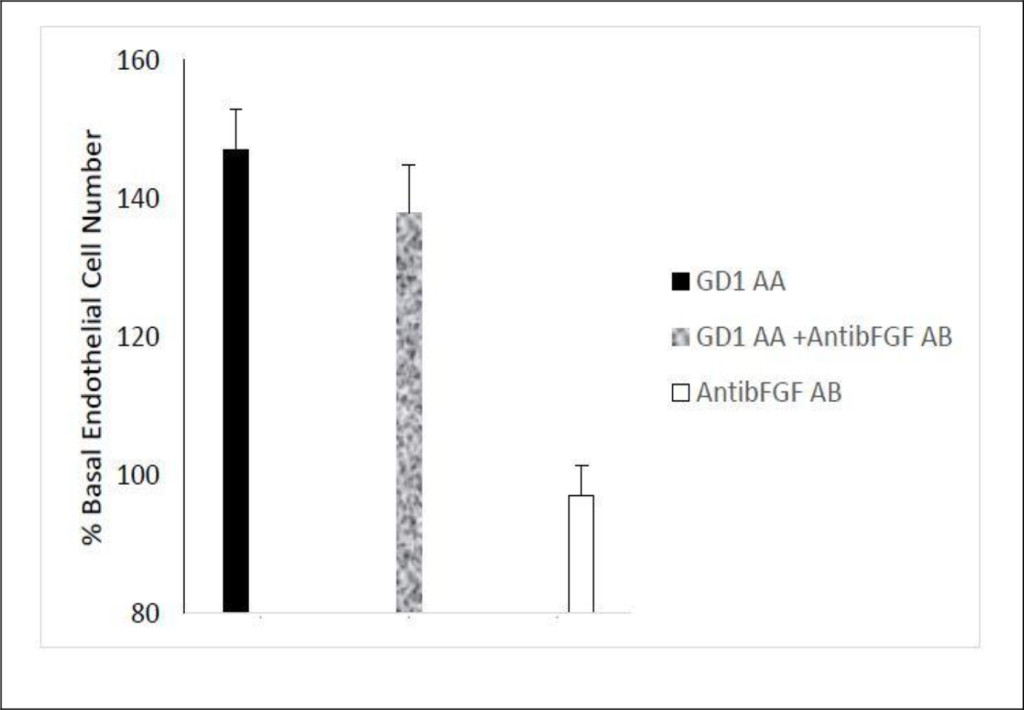

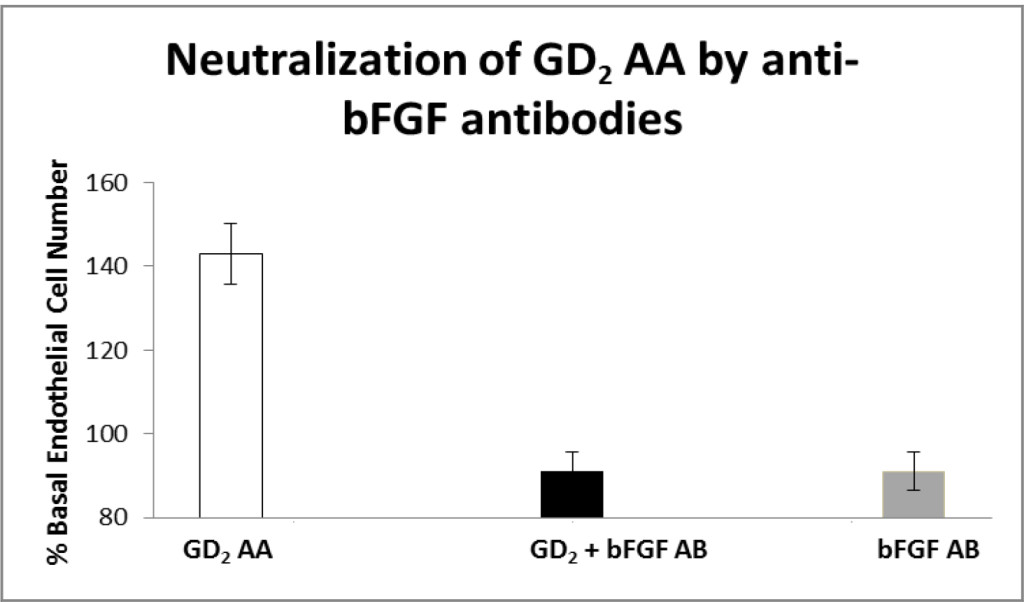

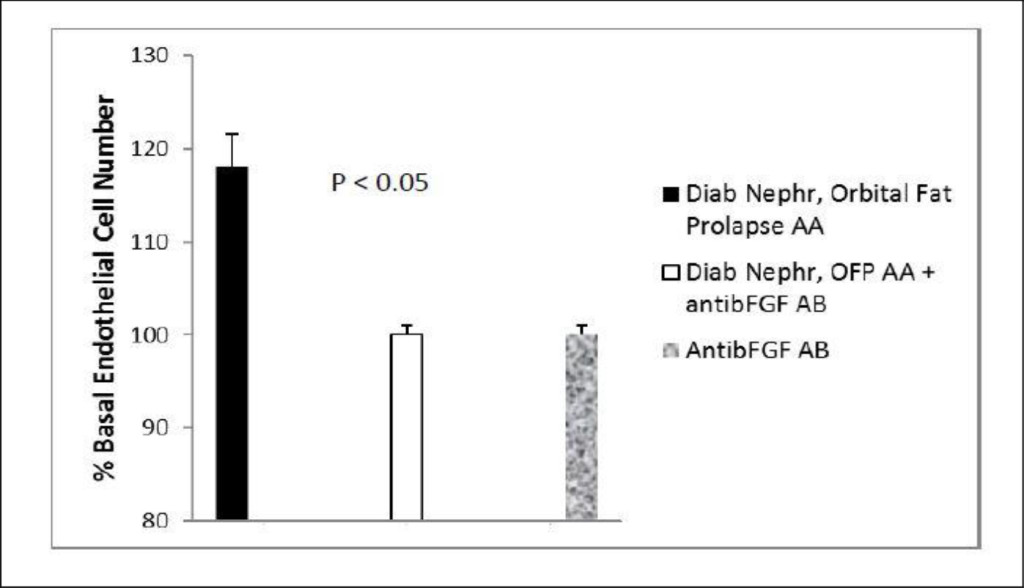

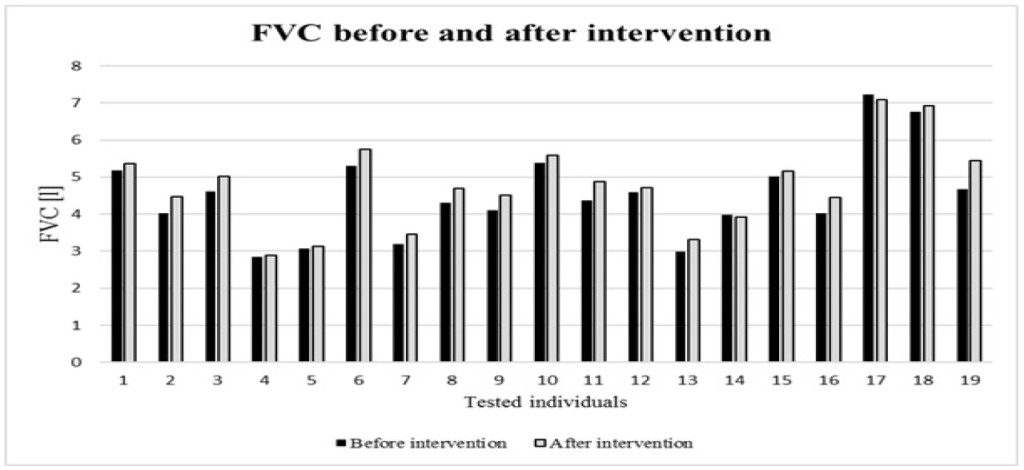

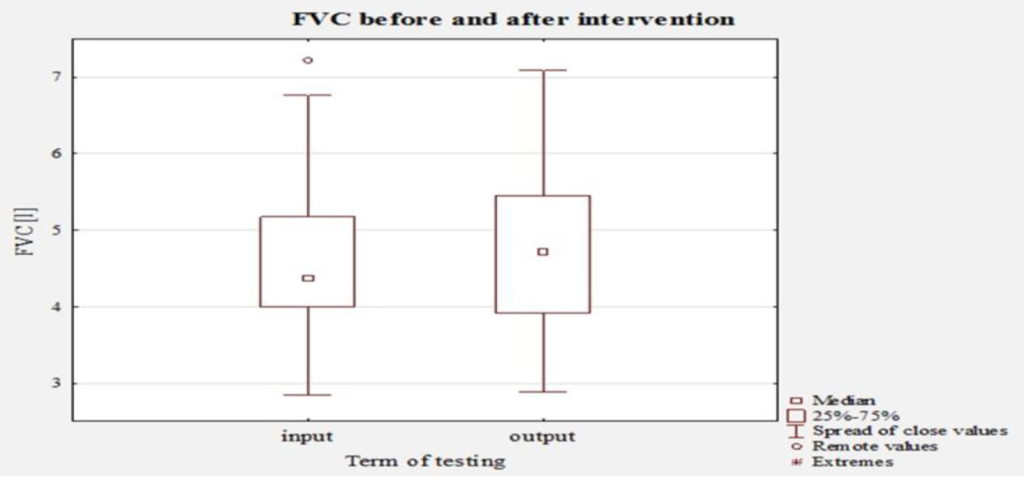

The test group athletes did breathing exercises for two months for 13.2 ± 3.87 minutes a day on average. The FVC results before the intervention exercises (Figure 1) were calculated to 4.51 ± 1.13 L and those after the intervention time equalled 4.78 ± 1.12 L (see Figures 2 and 3). For the control group the results amounted to 4.39 ± 1.21 L before the intervention and 4.41 ± 1.23 L thereafter. For the test group the improvement of the breathing volume during FVC was 6.0 % while for the control group 0.45 %. Therefore for the test group the factually significant improvement of the FVC (Cohen’s d = 0.24, small effect), is therefore statistically significant (Figure 2, 3). No significant differences between male and female individuals were found.

Figure 1. Breathing curve during FVC test.

Figure 2. FVC value for tested individuals before the intervention of breathing exercises and after.

Figure 3. The distribution of values of FVC in tested individuals before interventions breathing exercises and after.

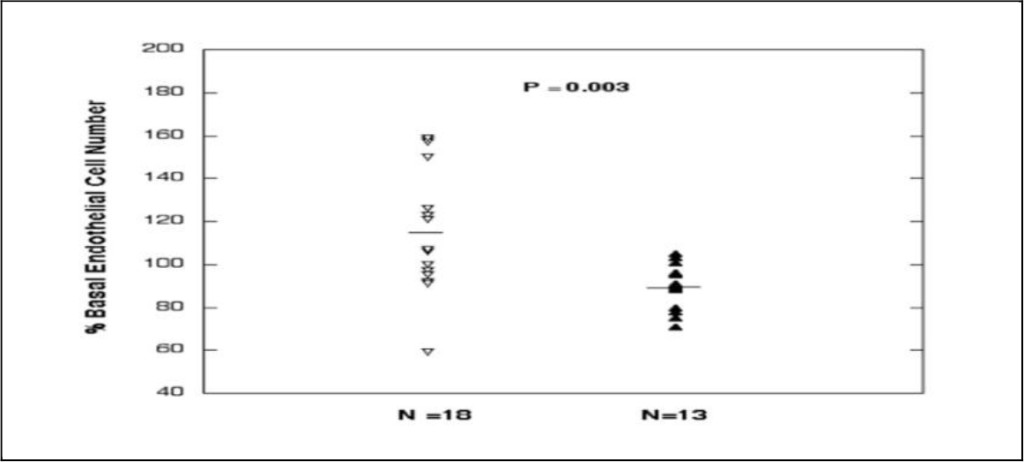

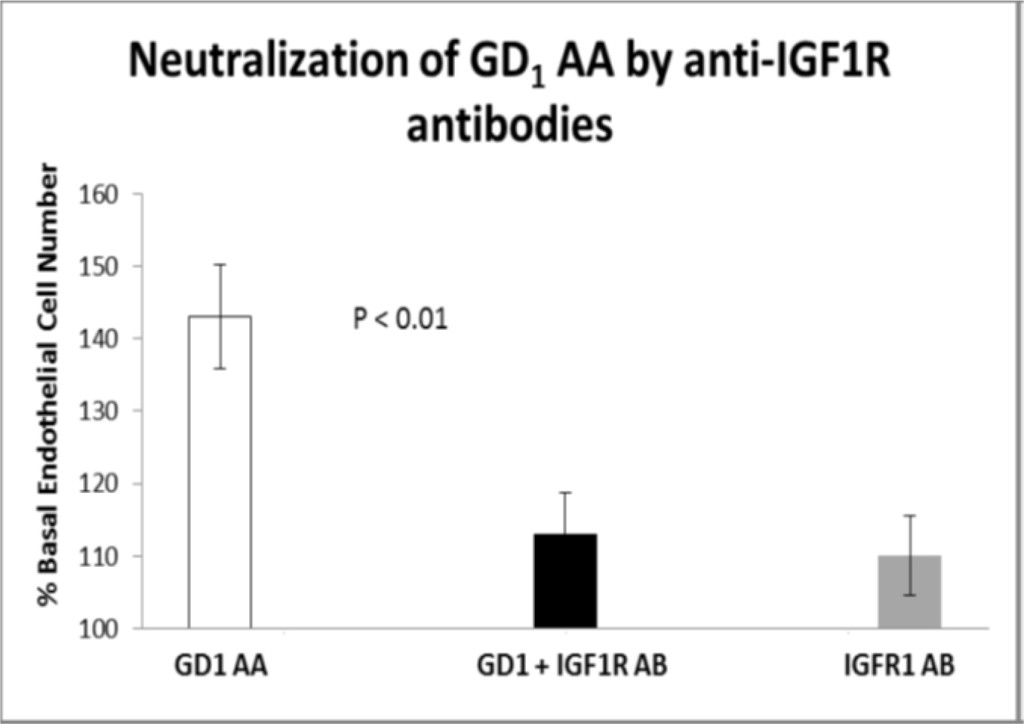

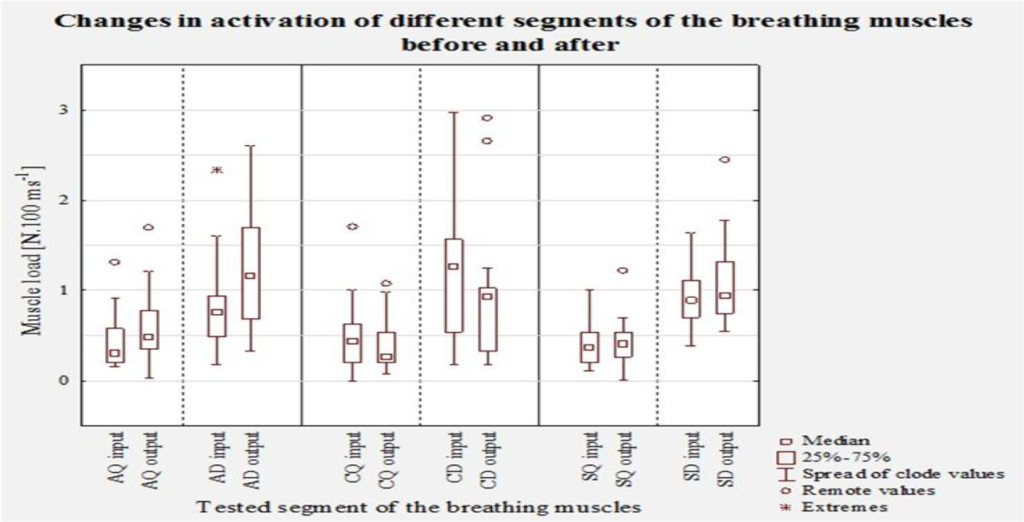

During the analysis of the breathing movements (Figure 4) in the individual sectors of the chest after the intervention program, an improvement particularly for the abdominal breathing was found, for both the quiet breathing, increase by 46.5 % (Cohen’s d=0.56, medium effect), and deep breathing with increase by 61.5 % (Cohen’s d = 0.82, large effect). For subclavian breathing both factually and statistically significant increase by 19.2 % of its contribution to deep breathing was found (Cohen’s d = 0.42, small effect). An increase for quiet subclavian breathing by 6.9 % was observed, although the change is neither factually or statistically significant (Cohen’s d = 0.11). For chest breathing a decrease in values by 20.5 % during quiet breathing was found, a change that is factually (Cohen’s d = 29.4, small effect) although not statistically significant. For deep chest breathing the activity of breathing muscles decreased by 21.8 %, a change that is factually (Cohen’s d = 35.9, small effect) and statistically significant. For the control group no factually or statistically significant change was observed, with change not larger than 1.5 % for any breathing muscle segment was found.

Figure 4. Involvement of the different segments of the thorax during quiet breathing and deep breathing before the intervention and after (breathing: BK – abdominal quiet, BH – abdominal deep, HK – chest quiet, HH – chest deep, PK – subclavian quiet, PH – subclavian deep).

Discussion

In order to be able to strengthen the necessary breathing muscles during the intervention, the three sections of deep breathing must be consciously acknowledged, trained separately and then reunited. The first most important section of breathing is the diaphragmal or abdominal breathing that is responsible for 60% of the full breathing efficiency. Chest breathing corresponds to 30% and subclavian to 10% of efficient breathing. The given percentage ratio applies to most of everyday activities. During physical exercise or some (pathological) changes in the organism this ratio is significantly changed [34]. As Kolář et al. [8] state the fact remains that the diaphragm is responsible for 2/3 of the gas exchange in the lungs.

The aim of the intervention program was to achieve controlled optimal stabilisation interplay of the breathing muscles and make the correct breathing stereotype automated. The emergence and development of overload on the musculoskeletal system can thus be prevented. However, success of the therapy is highly dependent on active participation of the test group. The output examination concluded improvement of both quiet and deep abdominal, as well as deep subclavian breathing. At the same time the chest breathing was shown to decrease for both the quiet and deep breathing types. Breathing movements that led to improved diaphragm breathing and simultaneous decrease of activity of chest breathing represents a positive change towards optimal activation of breathing muscles [8].The reality that needs to be respected is the fact that postural functions, positioning of the body in certain position or during a movement and the breathing functions are strongly interconnected and the keystone of this connection is the diaphragm, the major breathing muscle. A positive influence on the breathing pattern will also improve the stabilisation function of the diaphragm. Véle [10] states that quite frequently we meet patients with inspiratory positioning of the thorax (horizontal progression of the ribs) with activated accessory muscles (auxiliary inhalation muscles) during quiet breathing. These muscles have multiple connections onto the spine and for long-term inspirational positioning these muscles become central for the positioning of individual segments of the spine. This is the primary objective necessary to alter and teach the patient how to relax these muscles and at the same time activate the muscles of the lower respiratory sector so that the dysfunction of the breathing mechanism can be eliminated and as a feedback the postural functions can be influenced. This aim has been achieved by the application of the intervention program and the diaphragmal breathing was improved.

The chest and diaphragm breathing complement and compensate each other, which is why their function must be optimised. If the chest expansion is malfunctioning and the chest is rigid, the participation from the diaphragm increases and starts to dominate and vice versa. Provided that the extension of the chest is desired, the abdominal wall muscles need first to become relaxed in order for the diaphragm to be able to get as low as possible. During exhale, the abdominal muscles must contract to cause the compressed bowels to push the diaphragm up in the cranial direction. This causes a decrease of the chest volume and the exhale deepens. During influence of the external forces abdominal muscles are gradually activated, fixating the lower section of the chest. At the same time the spine is stabilised and hinders inspirational positioning of the chest [8]. Success of the therapy presumes an active participation of the test group. This was not always the case and for some tested individuals the improvement was minor, for some even negative. Once a week the exercises were conducted under supervision and their correct performance checked and if necessary corrected. The rest of the week, though, the exercises were conducted in home environment outside supervisor control where the effect of the exercises could be influenced by the quality of their performance. The results of the FVC tests are therefore not uniform, with half of the test group showing improvement by more than 0.3 L, while two individual did not show any improvement. After the two-month intervention exercises an improvement in FVC values was achieved for 95 % of the followed individuals. This change is furthermore both factually and statistically significant. No factually significant differences were observed between male and female individuals. For the FEV1 values an improvement was observed for 78 % of the tested individuals, for half of them by more than 0.3 Ls-1. One quarter of the individuals exhibited worsened, if by minimum, FEV1 values.

Conclusion

This study has confirmed that a two-month intervention of targeted breathing exercises has both factually and statistically significant influence on the activation and strengthening of breathing muscles through diaphragm breathing during both quiet and deep breathing and has at the same time factually and statistically significant influence on elevation of FVC and FEV1 values.

Acknowledgement

This research was supported by Grant agency of the University of South Bohemia within Team research project no. 034/2015/S.

References

- Clifton-Smith T, Rowley J (2011) Breathing pattern disorders and physiotherapy: inspiration for our profession. Physical Therapy Reviews 16: 75–86.

- Baltich J, von Tscharner V, Nigg BM (2015) Degradation of postural control with aging. Proc Inst Mech Eng H 229: 638–644. [crossref]

- Karakoyun DO, Özkaya M, Okutan VC, Dalgıç A, Belen D, et al. (2015) Biomechanical comparison of unilateral semi-rigid and dynamic stabilization on ovine vertebrae. Proc Inst Mech Eng H 229: 778–785. [crossref]

- Smolíková L, Mácek M (2010) Respiratory Physiotherapy and Pulmonary Rehabilitation. Brno: National center of nursing and non-medical health care.

- Mourek J (2005) Physiology: textbooks for medical students. Prague: Grada.

- Votava J (1988) Yoga by the doctor‘s eye. Prague: Avicenum.

- Véle F (2006) Kinesiology: a review of clinical kinesiology and pathogenesis for the diagnosis and therapy of musculoskeletal disorders. Prague: Triton.

- Kolár P, Bitnar P, Dyrhonová O, Horáček O, Kríž J, Adámková M … Zumrová I (2009) Rehabilitation in Clinical Practice. Prague: Galén.

- Dylevsky I, Druda R, Mrázková O (2000) Functional anatomy of man. Prague: Grada.

- Véle F (2012) Investigation of motor functions from a neurophysiological point of view: a guide for therapists working in neurorehabilitation. Prague: Triton.

- Malátová R (2015) Breath stereotype disorders. In Brodáni, Movement and Quality of Life 2015. Nitra: KTVŠ PF UKF Nitra.

- Rokyta R (2000) Physiology: for Bachelor Studies in Medicine, Natural Sciences and Physical Education. Prague: ISV.

- Cahalin LP (2004) Pulmonary evaluation. In: DeTurkW. E. & Cahalin L. P. (eds.). Cardiovascular and pulmonary physical therapy. McGraw-Hill, New York, USA.

- Kandus J, Satinská J (2001) A brief guide to the treatment of lung function. Brno: Institute for Further Education of Worker in Health Care.

- Lewit K (2003) Manipulative treatment in myoskeletal medicine. Prague: Saving Technology.

- Kaneko H, Horie J (2012) Breathing movements of the chest and abdominal wall in healthy subjects. Respir Care 57: 1442–1451. [crossref]

- Bockenhauer SE, Chen H, Julliard KN, Weedon J (2007) Measuring thoracic excursion: reliability of the cloth tape measure technique. J Am Osteopath Assoc 107: 191–196. [crossref]

- Moll JM, Wright V (1972) An objective clinical study of chest expansion. Ann Rheum Dis 31: 1–8. [crossref]

- Burgos-Vargas R, Castelazo-Duarte G, Orozco JA, Garduño-Espinosa J, Clark P, et al. (1993) Chest expansion in healthy adolescents and patients with the seronegative enthesopathy and arthropathy syndrome or juvenile ankylosing spondylitis. J Rheumatol 20: 1957–1960. [crossref]

- Harik-Khan RI, Wise RA, Fozard JL (1998) Determinants of maximal inspiratory pressure, The Baltimore Longitudinal Study of Aging. Am J Respir Crit Care Med 158: 1459–1464.

- Rochester CL (2003) Exercise training in chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. J Rehabil Res Dev 40: 59–80. [crossref]

- Fisher LR, Cawley MI, Holgate ST (1990) Relation between chest expansion, pulmonary function, and exercise tolerance in patients with ankylosing spondylitis. Ann Rheum Dis 49: 921–925.

- Kenney WL, Wilmore J, Costill D (2015) Physiology of Sport and Exercise 6th Edition. Human kinetics.

- Thomas JA, McIntosh JM (1994) Are incentive spirometry, intermittent positive pressure breathing, and deep breathing exercises effective in the prevention of postoperative pulmonary complications after upper abdominal surgery? A systematic overview and meta-analysis. Physical Therapy 74: 3–10.

- Dovalil J, Choutka M, Svoboda B, Hošek V, Peric T, et al. (2005) Výkon a trénink ve sportu. Praha: Olympia.

- Bartunková S, Heller J, Kohlíková E, Petr M, Smitka K, et al. (2013) Fyziologie pohybové záteže. Praha: FTVS UK.

- Malátová R, Pucelík J, Rokytová J, Kolár P (2007) The objectification of therapeutical methods used for improvement of the deep stabilizing spinal system. Neuro Endocrinol Lett 3: 315–320.

- Malátová R, Pucelík J, Rokytová J, Kolár P (2008) Technical means for objectification of medical treatments in the area of the deep stabilisation spinal system. Neuro Endocrinol Lett 1: 125–130.

- Malátová R, Drevikovská P (2009) Testing procedures for abdominal muscles using the muscle dynamometer SD02. Proc Inst Mech Eng H 223: 1041–1048. [crossref]

- Malátová R, Rokytová J, Stumbauer J (2013) The use of muscle dynamometer for correction of muscle imbalances in the area of deep stabilising spine system. Proc Inst Mech Eng H 227: 896–903. [crossref]

- Polášek M (1990) Joga eight stages of training. Bratislava: Sport.

- Kombercová J, Svobodová M (2000) Autorehabilitační sestava. Prague: Fountain.

- Bursová M (2005) Compensation exercises. Prague: Grada.

- Sponar, D. (2003). The basics of breathing. http://www.cvicime.cz/pdf/prace_s_dechem.pdf.