DOI: 10.31038/NAMS.2024724

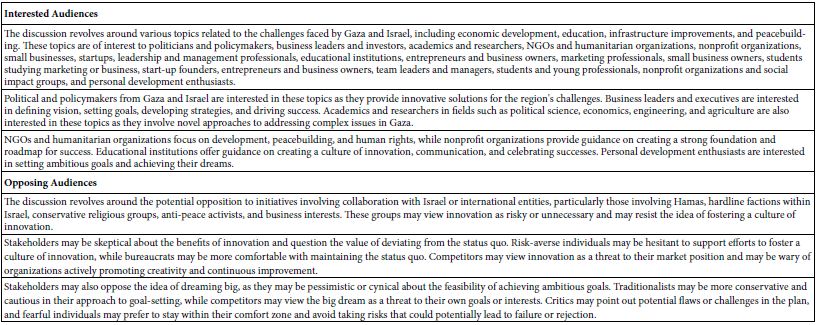

Abstract

Nanoplastics in the environment is rarely monitored due to the current limitation of detection technology and research strategies. Capillary electrophoresis (CE) can be coupled with ultraviolet (UV) and laser-induced fluorescence (LIF) detection for the analysis of fluorescent rhodamine dyes with high sensitivity. These organic dyes interact with polystyrene nanoplastics present in a water sample to undergo adsorption. A decrease of CE-LIF peak height represents a loss of dye concentration due to binding with the nanosphere surfaces. A standard calibration curve has been constructed for CE-LIF analysis of polystyrene nanosphere standard solutions using a rhodamine 6G concentration of 125 µg/mL, background electrolyte solution of 10 mM Na2HPO4 at pH 5.0, electrokinetic sample injection at 18 kV for 6 s, applied voltage of 18 kV across the total capillary length of 68 cm, diode laser operating at 8 V, λex at 480 nm, λem at 580 nm, and avalanche photosensor reverse-biased at 60 V. The fused silica capillary, after being conditioned with the background electrolyte solution for 30 min each day, yields good peak shapes, reproducible peak heights, and only slight variations in migration time. Each CE-analysis is completed within 10 min. Experimental binding data for rhody dye is modelled on the linear Langmuir isotherm equation to determine an adsorption capacity of 27-30 mg/g of nanospheres. The Freundlich isotherm model returns a similar adsorption capacity of 22 mg/g. The detection limit is 0.1 µg of polystyrene nanospheres in 1.6 mL of water sample for CE-LIF analysis.

Keywords

Binding isotherms, Capillary electrophoresis, Laser-induced fluorescence, Nanoplastics, Polystyrene, Rhodamine dyes, UV detection

Introduction

Nanoplastics are a group of synthetic polymer materials on the nanoscale size between 1 and 100 nm. Nanoplastics are primarily produced in laundry wastewater as acrylate, nylon, and polyester fibers [1]. They are normally present as colloids, and so their fate is governed by interfacial properties [2]. Incidentally produced nanoplastics exhibit a diversity of chemical compositions (most commonly polystyrene, polypropylene and polyethylene terephthalate) and physical morphologies that is typically absent from engineered nanomaterials [3]. Such diversity means that it is never straightforward to quantitively analyze water for an assessment of all suspended nanoplastics [4]. The contamination of freshwater lakes and rivers by nanoplastics represents an emerging global issue regarding their potential risk to aquatic life in these important ecosystems and flora, fauna, wildlife, and humans downstream. Pollution associated with nanoplastics can be tackled through source reduction, circular economy, and waste management [5]. Current water treatment processes are ineffective at removing nanoplastics; unlike microplastics, they are too small to be captured by conventional filtration systems. Their small size range enables nanoplastics to easily escape standard water separation and purification techniques [6,7]. The occurrence of microplastics in six major European rivers and their tributaries was investigated and reviewed based on the results from environmental studies that assessed the abundance of microplastics in different water columns [8]. Release of nanoplastics from drinking water bottles was characterized by SEM, XPS, SPES and µ-Raman Analysis [9]. Spherical organic nanoparticles from bottled water were collected effectively through a tangential flow ultrafiltration system [10]. Polyethylene terephthalate nanoplastics collected from commercially bottled drinking water were detected with an average mean size of 88 nm; their concentration was estimated to be 108 particles/mL by nanoparticle tracking analysis [11]. A new study has reported the levels of micro- and nano-particles released in carbonated beverage bottles range from 68 to 4.7×108 particles/L, potentially posing health risks to humans. Polypropylene bottles released more particles than polyethylene terephthalate and polyethylene bottles [12]. The occurrence of micro- and nano-plastics (with particle diameters from 0.7 to 20 μm) in plastic bottled water has been assessed, and the median concentration was 359 ng L−1. Polyethylene was the most detected polymer, while polyethylene terephthalate was found at the highest concentrations [13]. The content of microplastic and nanoplastic particles in raw water, tap water, and drinking water was analyzed. Plastic particles were found in all water samples, with an average abundance ranging from 204 to 336 particles/L in raw water, from 22 to 33 particles/L in tap water, and from 25 to 73 particles/L in drinking water [14]. Pyrolysis gas chromatography–mass spectrometry allows for the simultaneous identification and quantification of nine nanoplastic types, including polyethylene terephthalate, polyethylene, polycarbonate, polypropylene, polymethyl methacrylate, polystyrene, polyvinylchloride, nylon 6, and nylon 66, in environmental and potable water samples based on polymer-specific mass concentration. Limits of quantification ranged from 0.01 to 0.44 µg/L [15]. The lower microplastics abundance in tap water than in natural sources indicates their removal in drinking water treatment plants [16]. This evidence should encourage the consumers to drink tap water instead of bottled water, to limit their exposure to micro- and nano-plastics. More than one hundred studies on microplastics in food, water, and beverages were reviewed by Vitali et al [17].

It is difficult to categorically state the detrimental effects of nanoplastics due to the nascent stage of their characterization in aquatic environments. The toxic effects of nanoplastics on living organisms have systematically been reviewed [18,19], and studied [20]. Potential interactions of nanoplastics with other substances in a complex water matrix could lead to improper quantification. Nanoplastics have been reported to bind with several types of organic contaminants in water environments due to their high surface area-to-volume ratio and the nature of their surfaces. These contaminants include polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons, polychlorinated biphenyls, pharmaceuticals, heavy metal ions, fly ash, bisphenol A, antibiotics, and ammonium nitrogen. Inadvertent release of additives and contaminants adsorbed on nanoplastics in organism bodies poses more significant threats to living organisms than the nanoplastics themselves. New scientific evidence suggests that nanoplastics can attach to bacteria and viruses. In summary, this interplay of nanoplastics and water contaminants adds another layer of implications to quantitative analysis. In real exposure scenarios, formation of bio- and eco-coronas on nanoplastics is inevitable and displays various complex structures. Complete degradation of nanoplastics dispersed in water and exposed to simulated sunlight takes about a month for polystyrene and 2 years for polyethylene. These findings highlight the pervasiveness of nanoplastic pollution in our environment and underscore the importance of new research into detection methods. Modern instrumental methods for nanoplastics analysis (such as dark-field hyperspectral microscopy, micro-Fourier transform infrared imaging, surface enhanced Raman scattering/imaging, fluorescence microscopy, and atomic force microscopy) demonstrate many drawbacks including analysis time, availability, costs, detection limit, matrix digestion, and sample pretreatment. Although a LOD of 5 ppm was achieved in bottled water, tap water, and river water, single polystyrene nanoplastic particles can be only visualized down to 200 nm on the substrate. The treatment of environmental water samples is a particular challenge, due to their matrix complexity. Reliable techniques are lacking for isolating and pre-concentrating nanoplastics. It is crucial to integrate sample preparation regarding matrix effects into the development of any new instrumental method for nanoplastics analysis [21-39].

One feasible approach to the detection of nanoplastics with a substantial heterogeneity involves the addition of an organic fluorescent dye that interacts with their surfaces. Any binding can be determined, in principle, by a quantitative analysis of the dye before and after interaction with the nanoplastic to obtain a meaningful % binding result. The choice of organic dyes appropriate for binding plays a crucial part in the analysis of nanoparticles and nanoplastics in water. Absorption of ultraviolet (UV) light is a universal detection mode for organic compounds containing one or more aromatic rings. Better analytical sensitivity and selectivity can be expected from dyes that absorb the output wavelength of a laser and emit at a characteristic fluorescence wavelength for laser-induced fluorescence (LIF) detection. Capillary electrophoresis (CE) is an analytical separation technique that relies on the use of a fused silica capillary filled with a background electrolyte (BGE) solution to separate the dye from any interfering organic compounds. The capillary is operating under an applied voltage, in the kV range, between a positive cathode at the inlet and a negative anode at the outlet. Positively charged dyes will migrate rapidly towards the point of detection, being separated from each other due to differences in electrophoretic mobility. Neutral dyes will be transported by the forward electroosmotic flow, as a bundle without separation, through the capillary. Negatively charged dyes will take longer migration times to reach the detection point if their electrophoretic mobility in the reverse direction is not as high as the electroosmotic mobility. High detection selectivity is guaranteed if using fluorescence dyes that can be excited by a 480-nm diode laser. The binding analysis would be reliable if a mixture of organic dyes is employed to test the binding properties of each type of nanoplastic in water under controlled conditions of pH, ionic strength, and modifier.

This work aims at the development of a CE-LIF method for the analysis of dye mixtures, towards the quantitative analysis of nanoplastics without interference by other types of nanoparticles. Rhodamine is well documented in the scientific literature as the basis of chemosensors with colorimetric and fluorometric signals for the rapid detection of various metal ions, organic molecules, and biomolecules [40-43]. This dye becomes strongly emissive with versatile colors (red, orange, or purple), especially when the spirolactam ring is opened by a chelation mechanism. Among different rhodamine moieties, rhodamine B and 6G are very commonly used.

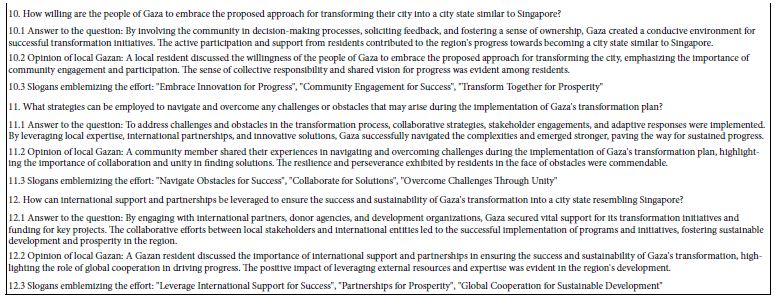

They offer unique optical properties including high photostability, large Stokes shift, and tunable fluorescence with structural derivatization of the side arms.

Materials and Methods

Mesityl oxide (MO), 4-dicyanomethylene-2-methyl-6-(4-dimethylaminostyryl)-4H-pyran (DCM), disodium fluorescein (DF), fluorescein adenosine triphosphate (FATP), rhodamine 6G hydrochloride (R6G·HCl), rhodamine B, and sodium phosphate dibasic (Na2HPO4) were obtained from Millipore Sigma (Oakville, Ontario, Canada). Invitrogen fluorescent dyes, coumarin 503 and coumarin 540A, were sourced from ThermoFisher Scientific (Waltham, Massachusetts, USA). Polystyrene 3080A nanospheres with an average diameter of 81 ± 3 nm were supplied by ThermoFisher Scientific (Fremont, California, USA).

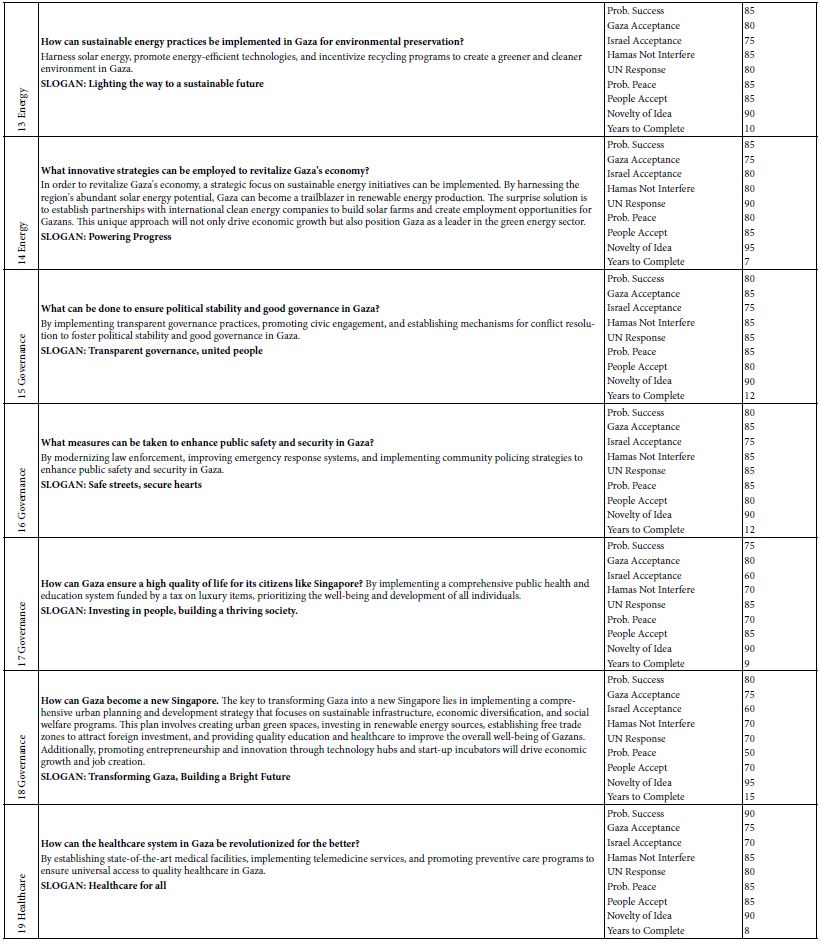

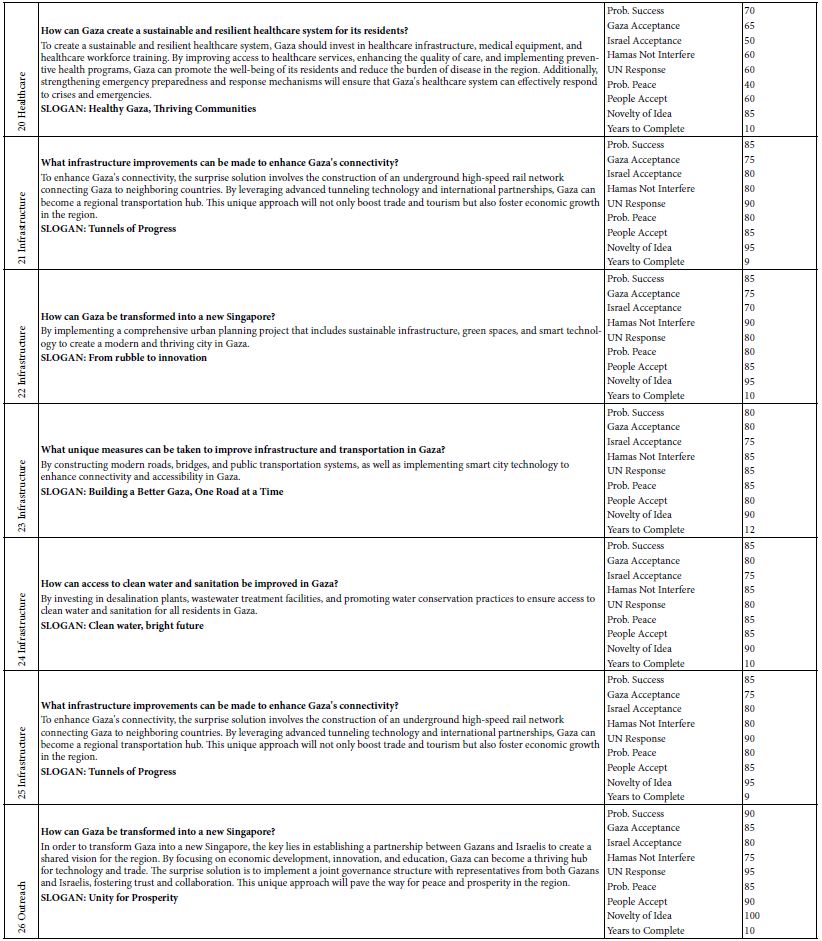

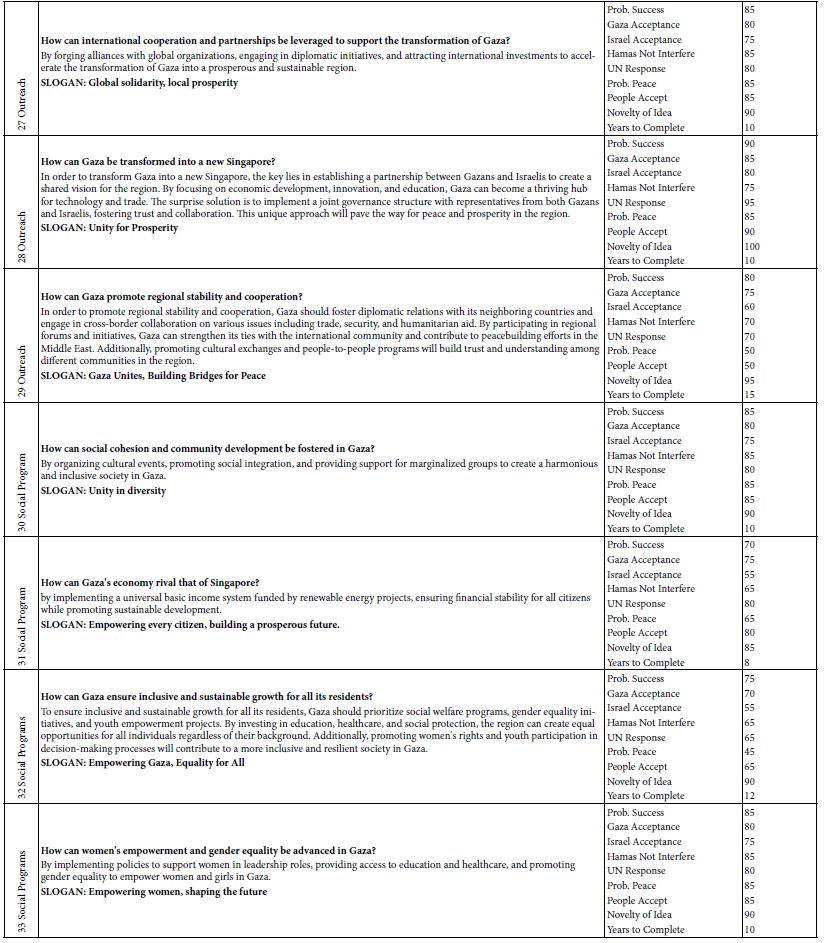

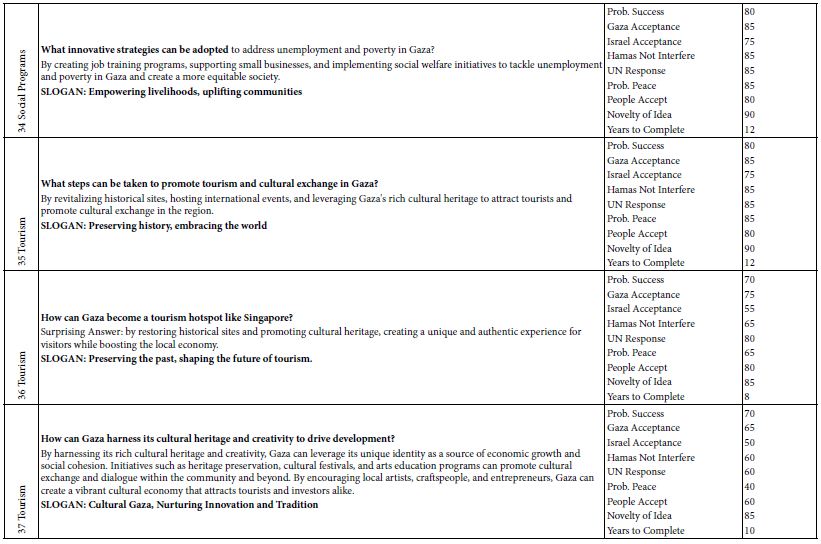

To prepare the 10 mM background electrolyte (BGE) solution, 0.284 g of Na2HPO4 was accurately weighed and dissolved in 150 mL of distilled deionized water (DDW) in a 200 mL conical flask. The solution was stirred continuously until Na2HPO4 fully dissolved. The pH was adjusted to 5.0 by the careful addition (three drops) of concentrated hydrochloric acid (HCl, 37% w/w) using a digital pipette for precision. After each acid increment, the solution was stirred, and the pH was checked and adjusted as necessary. The final volume was brought up to 200 mL with DDW to achieve the intended concentration. The prepared BGE (pH 5.0) was then stored in a clean container and rechecked for pH consistency before use.The CE-UV/LIF setup consisted of an SRI Model 203 chromatography data system box (Las Vegas, USA) acting as both the controller for the high-voltage power supply and a station for converting the detector output voltage into a digital signal, acquired by PeakSimple software. The UV detection employed a Bischoff Lambda 1010 detector (Metrohm Herisau, Switzerland), while the LIF system comprised a 480-nm diode laser paired with a Hamamatsu H7827 series photosensor module (Iwata City, Japan). Rhodamine B and R6G were prepared at a concentration of 5 mg in 2 mL of methanol or distilled water, ensuring effective fluorescence intensity, even in an acidic medium. Samples were introduced by electrokinetic injection at 18 kV for 6 seconds. A fused silica capillary, preconditioned with NaOH, distilled water and BGE for 30 minutes, was used for the CE analysis, which typically ran at 18 kV for 40 minutes. The percentage binding was calculated using the formula: (initial peak height – final peak height)/initial peak height = decrease in peak height/initial peak height. The LIF detector’s 480-nm laser employed a low applied voltage setting of 4.5 V to remove the polyimide coating within 1 second, creating a 1.0-mm clear window on a new capillary. All standard fluorescence excitation/emission spectra were recorded using a Horiba Fluoromax-4 spectrometer (Burlington, Ontario, Canada). The study of the effect of pH on the percentage binding of rhodamine B dye with polystyrene nanospheres was conducted to optimize sensitivity. The BGE’s pH was adjusted to pH 4.0 or 10.0 using either 12 M HCl or 10 M NaOH, respectively. The capillary was conditioned at each pH for 30 minutes (using 0.1 M NaOH for 10 minutes, distilled water for 10minutes, then the BGE for 10 minutes) prior to use in the CE-LIF analysis. Replicate runs of the CE system at each pH tested the reproducibility of the characteristic migration time of the dye, indicating the capillary’s stable condition.

In the preparation of nanoplastic standards for external calibration, a measured aliquot (1 µL) of a polystyrene nanospheres stock suspension was meticulously diluted using DDW (279 µL) inside a glass vial (2 mL capacity). The dilute nanoplastic suspension was subjected to manual agitation followed by ultrasonication in a water bath (for 2 minutes) to attain homogeneity. Concurrently, for the preparation of a working fluorescent dye solution, R6G dye (0.20 mg) was dissolved in the BGE solution (pH 5.0, 1.6 mL) inside another glass vial, culminating in a concentration of 125 µg/mL after ultrasonication in a water bath (for 2 minutes). Thereafter, the dilute nanoplastic suspension (commencing from 4 µL, increasing in steps of 4 µL, and culminating at 40 µL) was pipetted into the R6G solution (1.6 mL) in a glass vial. After each incremental addition, the mixture was subjected to manual agitation followedby ultrasonication in a water bath (for 2 minutes) to attain homogeneity. Prior to CE-LIF analysis, a baseline noise characterization of the instrumental system was performed. To reaffirm the reproducibility of the measurement results, each mixture was analyzed in triplicate.

Results and Discussion

The dyes that are useful for UV/LIF detection of nanoplastics would have to be unique and not easily found in nature or common industries, which is why R6G, DCM, disodium fluorescein and coumarins were chosen for the present study [44]. The first couple of fluorescent dyes tested were R6G.HCl (50%) and DCM (50%) in a rhody dye mixture. These two dyes were chosen as their fluorescence could be induced by the diode laser output wavelength of 480 nm and their emission could be detected through an optical interference filter with a narrow band-pass centered at 580 nm. R6G has an absorption maximum of 530 nm and an emission maximum of 556 nm due to the xanthene rings [45]. The DCM happens to be a charge-neutral molecule that was useful as a marker to indicate where neutral analyte peak appeared on the CE migration time scale. Although DCM absorbs maximally at 481 nm, it fluoresces the most at an orange wavelength of 644 nm due to the cyanine structure [46]. Conversely, R6G.HCl produces a R6G.H+ cation that was separated from DCM by CE, so no neutral dyes could interfere with its quantitative analysis. Several other dyes were also tested for better analytical sensitivity. They included coumarin 503, coumarin 540A, and disodium fluorescein, which all were capable of being excited by the 480-nm laser light. Disodium fluorescein was expected to emit a strong intensity of fluorescent light in the green portion of the visible spectrum at 531 nm. Although it has a stable xanthene ring structure similar to R6G, fluorescein is negatively charged [47]. Coumarin 540A was expected to be the best dye as its maximum absorption wavelength is 460 nm which matched the laser output wavelength of 480 nm very well [48]. Coumarin 503 was chosen as an alternative that might not be ideal because its maximum emission wavelength is 490 nm but it could still emit fluorescence in the blue-green region beyond 520 nm. This coumarin is a neutral compound due to the lack of charges on its molecules [49]. Both coumarin 503 and coumarin 540A are in a class of fluorescent dyes comprising the coumarin ring, which is an aromatic ring with a cyclic hydrocarbon chain impregnated with an ester and a single double bond.

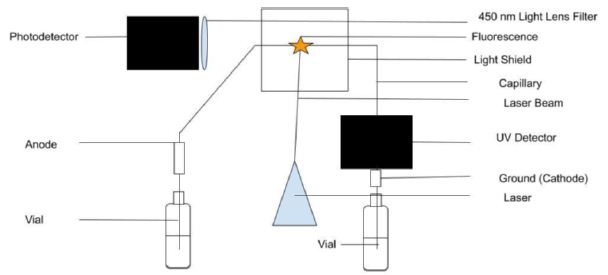

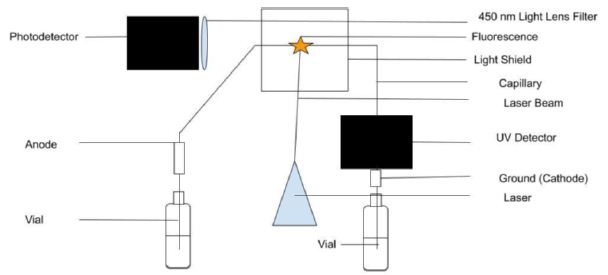

Two detectors were used in the present CE study; they were a UV detector and an LIF detector as illustrated in Figure 1. The UV detector was reliable and consistent. Following the Beer’s law, UV absorbance was directly proportional to the dye concentration via its molar absorptivity in the wavelength range between 190 nm and 210 nm. Then mesityl oxide (0.1% by volume in methanol) was run to both test the electroosmotic flow (EOF) of BGE solution through the capillary and determine the migration time of all neutral molecules. Using 10 mM Na2HPO4 as the BGE solution at pH 9.4, the CE-UV peak for MO appeared at 4.20±0.03 min. Next, the rhody dye mixture was analyzed and produced a strong CE peak followed by a weak peak with UV detection. With BGE at pH 8.0, CE-UV analysis produced three FATP peaks at 6.01, 16.37 and 24.04 min and one MO peak at 5.60±0.07 min as expected from the use of a less alkaline pH.

Figure 1: Capillary electrophoresis setup with UV light absorption and laser-induced fluorescence emission detectors. Light shields to stop the laser beam and block room light are not shown for clarity.

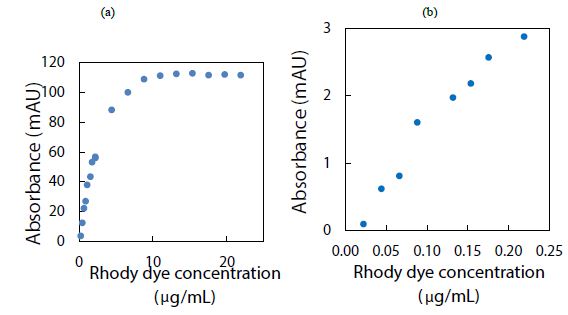

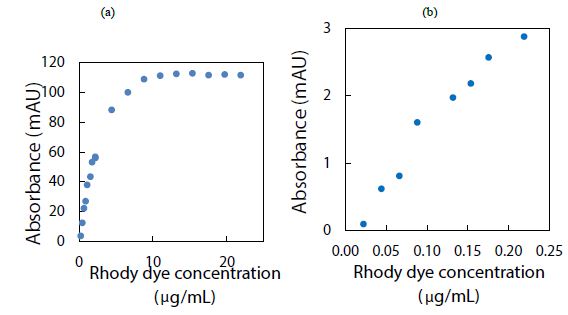

The rhody dye mixture was used to analyze an aqueous sample containing polystyrene nanospheres (1.3 mg/mL) by measuring the strong CE-UV peak after each standard addition. The resultant peak height, corrected for a dilution factor and expressed in milli-absorbance units (mAU), was plotted against the spiked volume of rhody dye. As it can be seen in Figure 2(a), depicting the spiking of diluted polystyrene nanospheres with rhodamine dye for CE-UV analysis, revealed that the standard calibration curve demonstrated linearity prior to reaching saturation of the UV detector’s signal output. Most notably, extrapolation of the trend line in Figure 2(b) backwards intersected the x-axis at an intercept value (approximately 0.01 µg/mL), suggesting an initial dye concentration. This detection implies the substantial binding between the dye molecules and the polystyrene nanospheres, causing the apparent dye concentration in solution to diminish. A limitation in utilizing UV detection is the possible interference from uncharacterized components in the water matrix that absorb UV light at the same wavelength of 200 nm. Such components could co-migrate with the rhodamine dye during CE analysis, leading to confounded results. This interference underscores the need for careful control of matrix effects, particularly when assessing trace-level nanoplastic contamination.

Figure 2: Spiking diluted polystyrene nanospheres with rhody dye for CE-UV analysis: (a) high dye concentrations, and (b) low dye concentrations. BGE solution: 10 mM Na2HPO4 at pH 9.4; UV detection wavelength: 200 nm.

To establish a baseline signal and gauge potential interferences, the intrinsic fluorescence of the dye was first characterized in the absence of polystyrene nanospheres. This control measurement enabled the determination of the dye’s peak height, providing a reference for comparison once polystyrene nanospheres were introduced. By doing so, any changes attributable to the interactions between the dye and the nanoplastics could be accurately quantified. Furthermore, the incorporation of replicate blank samples, devoid of both dye and nanoplastics, facilitated the assessment of background noise and matrix effects on UV detection at 200 nm. These measures ensured that the subsequent analysis of nanoplastic-dye interactions was robust against potential confounding signals.

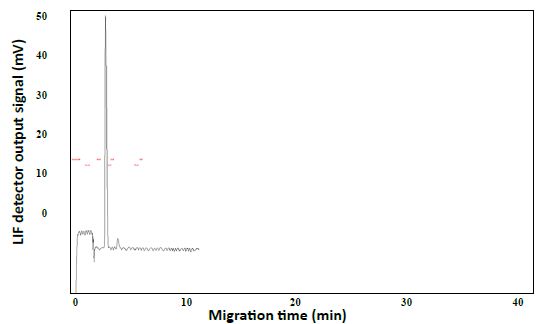

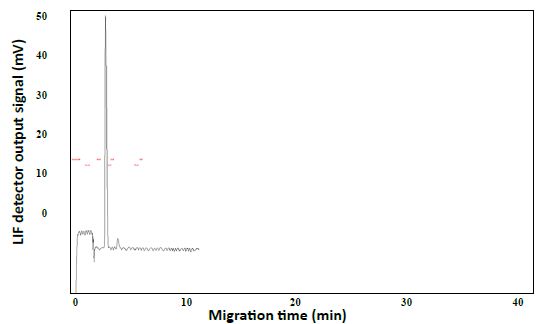

Alternatively, LIF was potentially more sensitive by about 100 times using an avalanche photosensor to measure the emission intensity. Both detectors determined an unknown concentration of the dye using standard solutions with known concentrations to construct a calibration curve. Disodium fluorescein dissolved fully in water/methanol (10:8 v/v) and produced a CE-LIF peak at the migration time of 4.96±0.48 min. However, DF had a flaw of contaminating the capillary inlet and hence the BGE solution, raising the baseline fluorescence significantly after several runs. Coumarin 503 and coumarin 540A were not fully dissolved in water/methanol (10:8 v/v). Their light blue cyan and green emissions required a different interference filter for optimal LIF detection. Therefore, the rhody dye was better for the CE-LIF setup as they had good solubility, migration times, and peak heights. Using a BGE solution at pH 9.4, the R6G and DCM peaks were observed at 3.53 min and 3.66 min respectively in Figure 3. Adding the LIF detector caused no noticeable harm to the original CE-UV system, requiring only the 480-nm laser beam to create a clear window on the same capillary for LIF detection. The capillary proved itself to be capable of generating repeatable results within the day, separating charged dyes of different characteristic migration times.

Figure 3: CE-LIF analysis of rhody dye. BGE solution: 10 mM Na2HPO4 at pH 9.4; applied voltage on diode laser: 5.0 V; λex: 480 nm; photosensor reverse bias: 60 V; λ em: 580 nm.

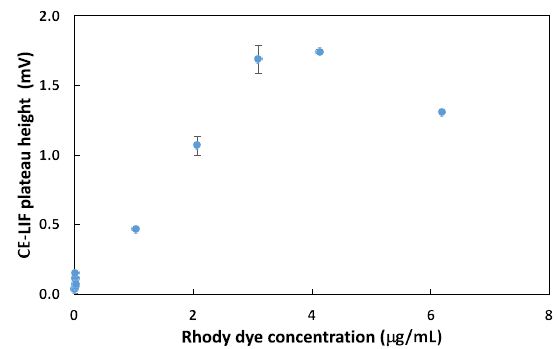

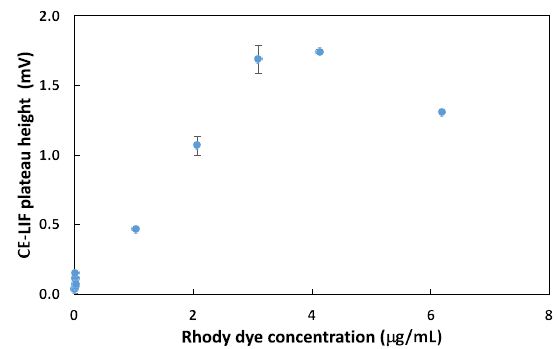

Next, the CE-LIF method was combined with frontal analysis to minimalize experimental errors due to a reduction in the manipulation of samples. Improved reproducibility was evidenced by replicate analysis of the rhody dye at different concentrations to construct the standard calibration curve shown in Figure 4. The electric charges of nanoplastics can significantly impact their physiochemical properties, solubility, electrophoretic mobility, reactivity, and binding interactions with other substances in water [50]. Their charge state depends on a variety of factors like the type of plastic material, the pH of water, and any surface coatings or modifications on the nanoplastics. Certain plastic materials can have intrinsic polarity when immersed in water. For example, polyethylene nanoparticles are generally neutral in charge but become negatively charged above pH 2.5 after surface oxidation [51]. Certain types of nanoplastics acquire a negative charge due to the presence of specific functional groups that ionize in water, e.g., polyacrylic/methacrylic acids (containing -COOH groups), polystyrene sulfonate (containing -SO3H groups), and polyethylene terephthalate (its surface can be converted into -COOH and -OH groups). Negatively charged plastics attract positively charged toxins in the environment, leading to potential health hazards if consumed by local organisms [52]. Other types of plastics have a natural propensity to become positively charged when immersed in water, like poly diallyl dimethyl ammonium chloride (with quaternary ammonium groups), poly-4-vinylpyridine, and polyethyleneimine [53]. The surface of nanoplastics may be coated or modified to create cationic nanoplastics. For example, cationic polystyrene nanoparticles can be produced by incorporating positively charged groups (such as -NH3+) on the surface [54]. Consequently, any changes of ionic charge affect the interaction of nanoplastics with water contaminants.

Figure 4: Combination of CE-LIF with frontal analysis to construct a standard calibration curve for rhody dye at different concentrations. BGE solution: 10 mM Na2HPO4 at pH 9.4; applied voltage on diode laser: 5.0 V; λ ex: 480 nm; photosensor reverse bias: 60 V; λ em: 580 nm.

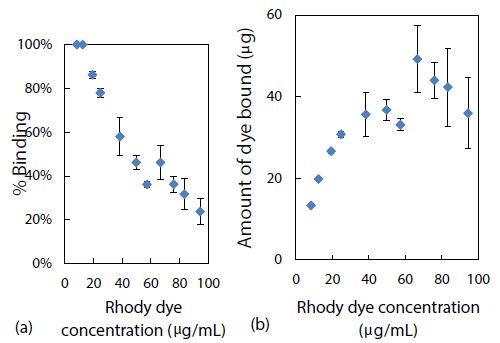

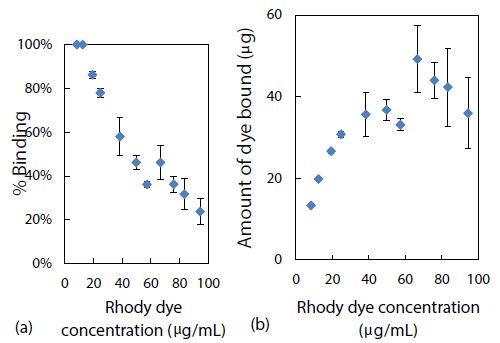

Experimentally, using CE-LIF in the conventional analysis mode, both the % binding and the amount of rhody dye bound with 2.8 mg of polystyrene nanoparticles were determined. As presented in Figure 5(a), nearly 100% quantitative binding onto the nanoparticle surfaces was achieved at the lowest concentrations of rhody dye studied. This adsorption capacity of the nanoplastics was commensurate with their small particle size which has a direct correlation to large surface area, providing more sites for dye adsorption. Conversely, as shown in Figure 5(b), the amount of dye bound seemed to be reaching a saturation level with the highest dye concentrations studied.

Figure 5: Effect of rhody dye concentration on (a) % binding and (b) amount of dye bound, with 2.8 mg of polystyrene nanospheres.

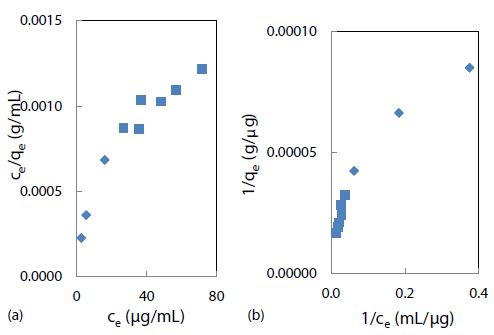

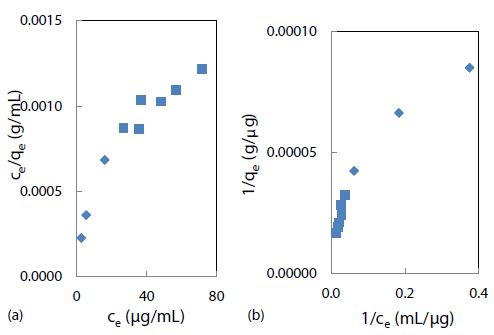

The Langmuir adsorption model was attempted by fitting the above binding data with this linear isotherm equation Ce/qe = Ce/qmax + 1/KLqmax for ce from 2.7 to 16 mg/mL, as demonstrated in Figure 6(a). The maximum adsorption capacity (qmax) for a saturated surface was determined from the reciprocal of slope to be 30 mg/g of nanospheres, and the half-saturation coefficient or Langmuir equilibrium constant (KL) was then calculated from the y-intercept to be 4.8 mL/mg of rhody dye. The same binding data was next fitted with another isotherm equation 1/qe = 1/qmax + 1/qmaxKLce for cross-checking purposes. As shown in Figure 6(b), qmax was determined from the reciprocal of y-intercept to be 27 mg/g of nanospheres, and KL was calculated from the quotient of intercept and slope to be 2.8 mL/mg. Although the two qmax results were similar within model fitting errors, the two KL results were rather discrepant mainly due to a larger statistical weight being put on the low ce data points that skewed the slope. New results are reporting that the adsorption equilibrium constant of triclosan in a suspension of pristine polystyrene nanoparticles (100 nm) is 2.78 L/g [55]. Ion strength greatly affects the outer sphere complexation due to compression of the double electrical layer on each particle surface. The qmax value of a nanoplastic surface is hypothetically influenced by two crucial factors: chemical composition and nanoporous structures. Clearly, the R-square values of 0.8655 and 0.9171 suggested that the Langmuir adsorption isotherm might not be the best model for the binding of rhody dye on polystyrene nanospheres. The Langmuir model assumes that the adsorbate (rhody dye) molecules bind with a homogeneous surface of the adsorbent (polystyrene nanosphere) to form a monolayer without any interaction between the adsorbed molecules. It implies that the energy of adsorption on a homogeneous surface is independent of surface coverage, which may not be true. The nonlinear curves in Figures 6(a) and 6(b) however indicated that the Langmuir model was far from ideal for describing the binding of rhody dye with polystyrene nanospheres.

Figure 6: Langmuir isotherm models of rhody dye binding with 2.8 mg of polystyrene nanospheres at room temperature (23 ± 1°C): (a) ce/qe = ce/qmax +1/KL + qmax and (b) 1/qe = 1/qmax + 1/qmaxKLce.

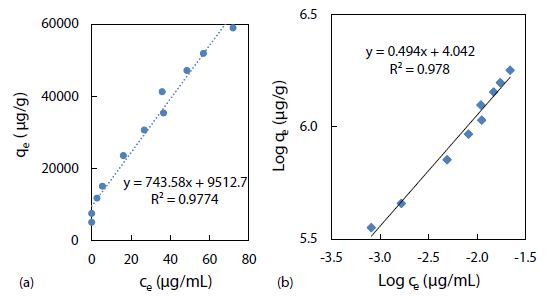

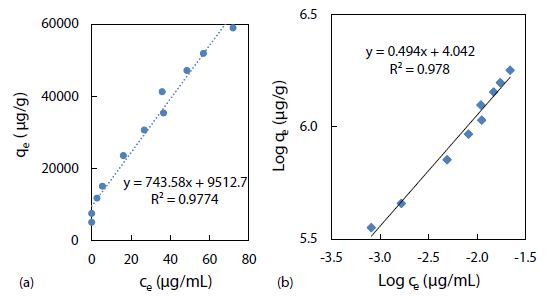

The Freundlich adsorption isotherm, qe = Kfce1/n, is another equation widely used for data fitting to model the relationship between the sorbed mass (qe) on a heterogeneous surface per unit weight of adsorbent and the aqueous concentration (ce) at equilibrium [56]. Although the Freundlich equation is purely empirical, it provided important information regarding adsorption of rhody dye on the polystyrene nanospheres. The Freundlich isotherm plot in Figure 7(a) shows linearity from 2.7 up to 40 mg/mL (approximately 50% of maximum saturation), above which it became nonlinear. As shown in Figure 7(b), a linearized plot of log qe = log Kf + 1/n log ce, yielded an equilibrium partition coefficient Kf = 11 mg/g and a Freundlich exponential coefficient n = 2.0 through the y-intercept and slope respectively. Kf is a comparative measure of the adsorption capacity for the adsorbent, and it indicates the Freundlich adsorption capacity. Then qmax was calculated from n times Kf to be 22 mg/g at room temperature (23 ± 1oC). The empirical constant n is related to the heterogeneity of the adsorbent surface [57]. For a favourable adsorption, 0 < n < 1, while n > 1 represents an unfavourable adsorption, and n = 1 indicates a linear adsorption [58]. A larger n value means that the system is more heterogeneous, which usually results in non-linearity of the adsorption isotherm [59]. A Freundlich exponential coefficient (n) in the range from 0.71 to 1.15 is newly reported for the adsorption of triclosan on pristine polystyrene nanoparticles.

Figure 7: Freundlich isotherm models of rhody dye binding with 2.8 mg of polystyrene nanospheres at room temperature (23 ± 1°C): (a) qe = Kf ce1/n, and (b) log qe = log Kf + 1/n log ce.

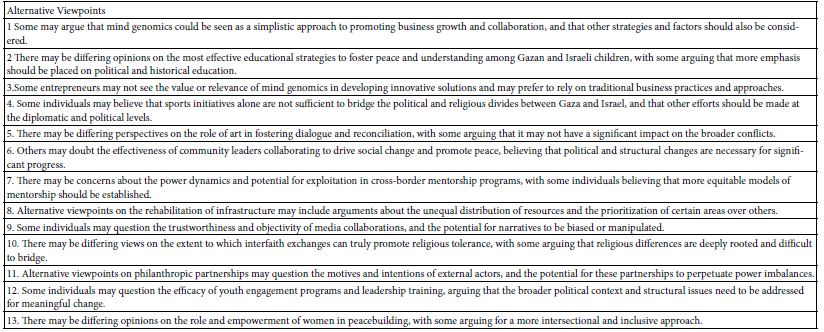

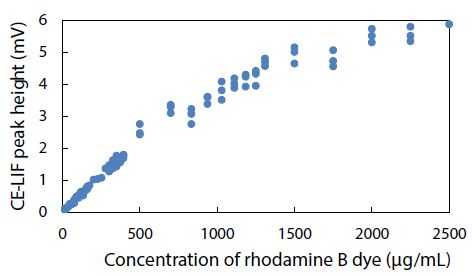

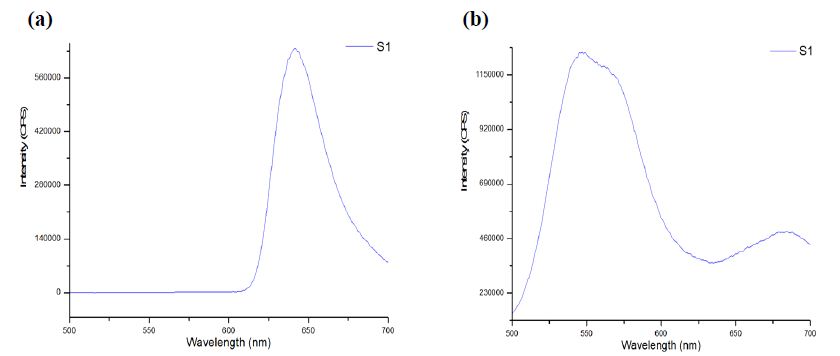

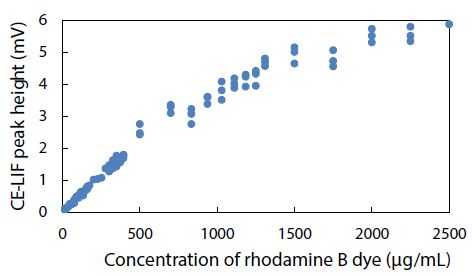

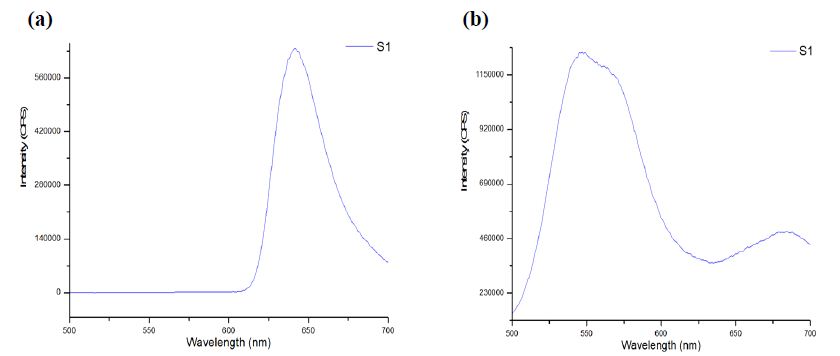

The CE-LIF method was combined with electrokinetic sample injection to achieve rapid analysis of rhodamine B dye (migration time = 2.52 ± 0.01 min) at different concentrations to construct the standard calibration curve shown in Figure 8. A linear relationship is evident between the CE-LIF peak height for rhodamine B and the dye concentration up to 500 μg/mL, thanks to the short optical pathlength for laser excitation inside the fused silica capillary with an inner diameter of only 100 μm. Apparently, 400 μg/mL would be an optimal dye concentration of spiking with diluted polystyrene to repeat the CE-LIF analysis. Note that the peak height for each concentration was not maximal because the interference filter transmitted the fluorescence emission light most efficiently at a wavelength of 580 ± 5 nm which was rather different from the maximum emission wavelength of 645-650 nm for rhodamine B (in 10 mM BGE at pH 9.0), as illustrated in Figure 9(a). The same interference filter was a good match for DCM that exhibited a maximum emission wavelength of 550-570 nm in Figure 9(b).

Figure 8: Combination of CE-LIF with electrokinetic sample injection to construct a standard calibration curve for rhodamine B dye at different concentrations. BGE solution: 10 mM Na2HPO4 at pH 9.4; applied voltage on diode laser: 10 V; λ ex: 480 nm; photosensor reverse-bias: 60 V; λ em: 580 nm.

Figure 9: Fluorescence emission spectra obtained using Fluoromax-4 with λ ex of 480 ± 5 nm from (a) rhodamine B dye, and (b) DCM, in 10 mM Na2HPO4 at pH 9.5.

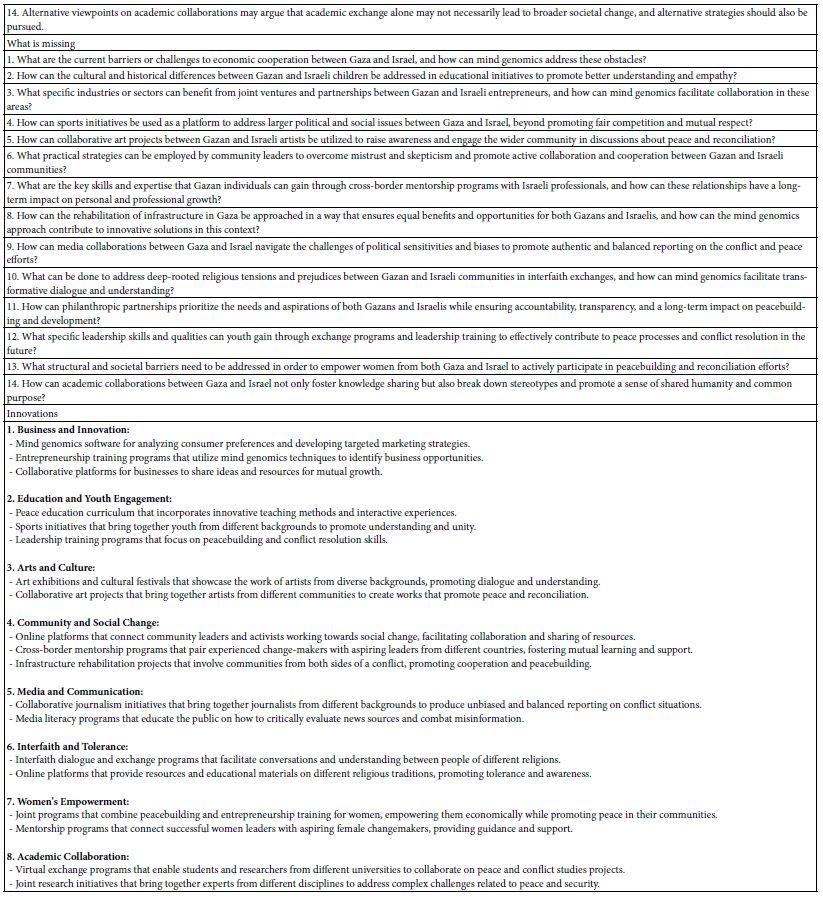

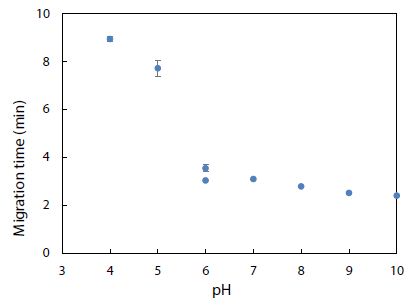

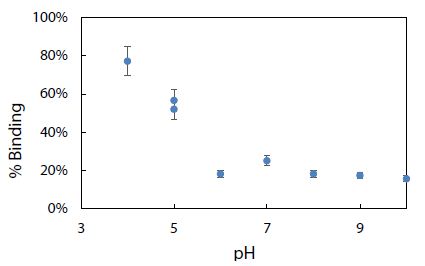

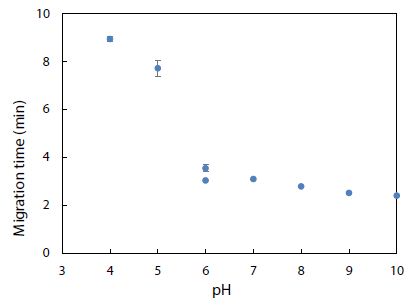

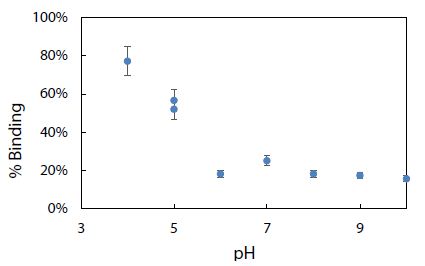

Environmental conditions like pH, salinity, and temperature could influence the degree of dye adsorption onto nanoplastics. The effect of pH on the electrophoretic migration of rhodamine B was studied next. Figure 10 shows the normal trend of a longer migration time with a lower pH, as expected from a decrease in electroosmotic flow of the BGE solution. Note that two data points are presented for pH 6 based on duplicate measurements. The trend also indicated that each pH was ready for CE-LIF analysis after conditioning the capillary for 30 min. Sensitivity of the CE-LIF analysis, in terms of % binding, could be maximized after binding tests were conducted over a range of pH levels to determine an optimal pH based on Figure 11. A high result of 77% was obtained at pH 4.0 for the binding of rhodamine B with polystyrene nanospheres. This effect can be explained by the pKa of 3.2 for rhodamine B; [60] and pH 9.9 for zero charge on polystyrene nanoplastics [61]. As the pH approached 4.0, the zeta potential of nanospheres became stabilized at +50 mV. The effect of pH on the ionization of rhodamine B had previously been reported [62]. There was apparently a stronger interaction between rhodamine B and polystyrene nanospheres at a lower pH. However, pH 5 was a better choice than pH 4 for the CE-LIF determination of nanospheres because the % binding of rhodamine B had a smaller standard deviation and the migration time of 7.7 min was shorter for each sample analysis.

Figure 10: Effect of pH on migration time of rhodamine B dye. Error bars indicate one standard deviation of uncertainty observed at each pH.

Figure 11: Effect of pH on % binding of rhodamine B dye with 2.8 mg of polystyrene nanospheres.

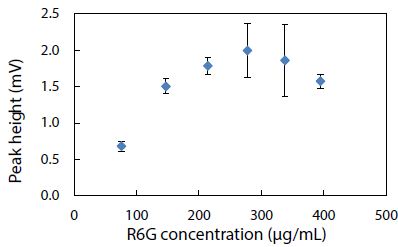

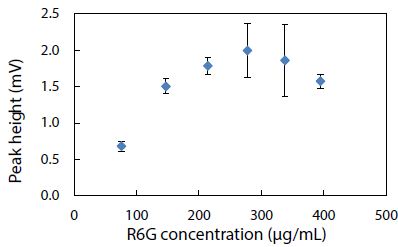

Using the BGE solution at pH 5 to condition the capillary, rhodamine 6G standard solutions were analyzed by CE-LIF to construct the calibration curve shown in Figure 12. The linear dynamic range can be seen to go from near zero up to approximately 150 mg/mL, in which the rhodamine 6G peak appeared at a migration time of 7.8 ± 0.2 min. This migration time became 7.9 ± 0.4 min when the full concentration range was studied up to 400 mg/mL. Compared to the migration time of 7.7 ± 0.3 min obtained in Figure 10 for rhodamine B at pH 5, these two dyes are too similar in their electrophoretic mobilities (despite their different molecular structures) to be separable by the present CE analysis method. Hence, the need for other fluorescent dyes that can be resolved as distinct peaks (with different migration times) remained.

Figure 12: Standard calibration curve for CE-LIF analysis of rhodamine 6G standard solutions. BGE solution: 10 mM Na2HPO4 at pH 5.0; electrokinetic sample injection: 6 s; applied voltage on diode laser: 8 V; λ ex: 480 nm; photosensor reverse bias: 60 V; λ em: 580 nm.

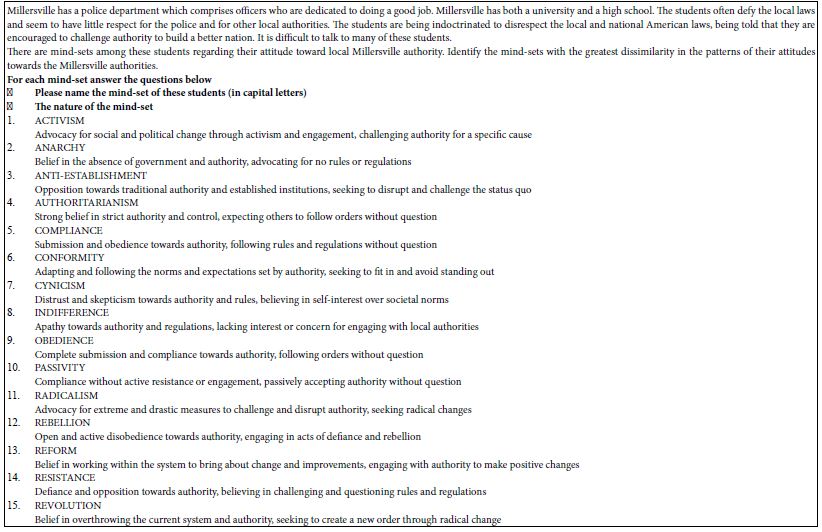

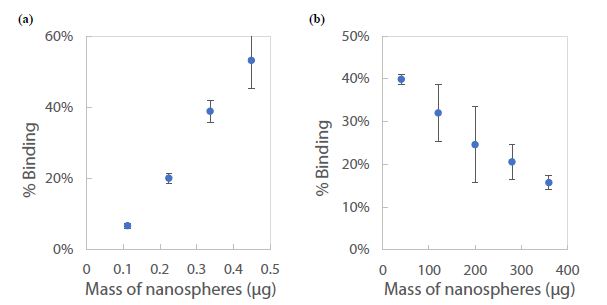

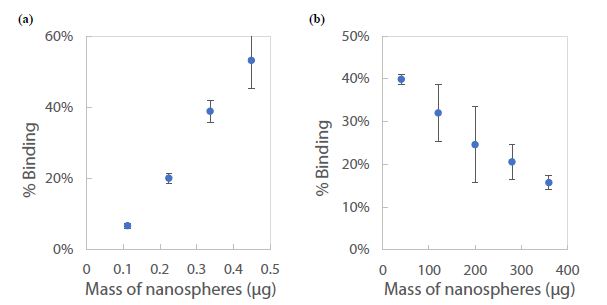

To validate the CE-LIF method, a constant concentration of the fluorescent dye R6G was analyzed across varying quantities of nanospheres in a series of water samples. In Figure 13a, there is a demonstrated positive correlation between the % binding of R6G and the mass of nanospheres ranging from 0.11 to 0.45 µg. This increase in % binding can be attributed to the additional surface area provided by a greater mass of nanospheres, which presents more potential binding sites for R6G molecules. Conversely, as depicted in Figure 13b, incrementing the mass of nanospheres further (from 10 to 350 µg) inversely affects the % binding. This counterintuitive result is interpreted as the onset of nanoparticle aggregation when in high concentration within the 1.6 mL water sample [63]. Aggregation reduces the effective surface area available for R6G binding, since clusters of nanospheres offer fewer exposed binding sites compared to the same mass of dispersed nanoparticles. To ensure the reliability of quantification in samples with high nanoplastic concentrations, such as those from industrial wastewater, it is recommended to perform serial dilutions. This approach ensures that measurements fall within the linear dynamic range, exhibiting a proportional decrease in % binding, thus yielding accurate assessments (as shown in Figure 13a).

Figure 13: Standard calibration curve for CE-LIF analysis of polystyrene nanospheres in 1.6 mL of water: (a) below 1 µg, and (b) above 10 µg. Rhodamine 6G dye concentration: 125 µg/mL; BGE solution: 10 mM Na2HPO4 at pH 5.0; electrokinetic sample injection: 6 s; applied voltage on diode laser: 8 V; λ ex: 480 nm; voltage setting on photodetector: 6.0; λem: 580 nm.

The percentage of binding (% binding) has emerged as a valuable parameter for the quantification of nanoplastics in aqueous environments. Organic dyes, owing to their high affinity for diverse types of polymers, can achieve significant levels of binding. This characteristic makes the % binding an appropriate metric for the analysis of environmental water samples, potentially revealing the prevalence and persistence of nanoplastic contaminants. In the context of aquatic ecosystems, % binding can yield insights into the duration that nanoplastics may persist and how readily they interact with organic molecules. Nonetheless, employing % binding as a determinant for nanoplastic content in water analysis comes with inherent constraints. Specifically, there is an underlying assumption that the binding of the fluorescent dye to nanoplastics reaches an equilibrium state, a condition representing a balance between the adsorbed dye on the nanoplastic surface and the dissolved unbound dye in the surrounding medium. The validity of this equilibrium assumption is critical and must be empirically established to ensure accurate quantification. The interaction dynamics between fluorescent dyes and nanoplastics are intricate and carry implications for environmental surveillance and the tracing of pollution sources. To navigate these complexities, systematic research is essential to unravel the nuances of dye-nanoplastic interactions thoroughly. In-depth exploration of these relationships not only contributes to a better understanding of nanoplastic pollution in water bodies such as those in Ontario but also aids in refining the methodologies used to evaluate and safeguard water quality.

Could nanoplastic pollution be monitored by LIF detection without CE separation, or simply conventional spectrofluorimetry using the Fluoromax-4? Such monitoring would be possible if (and only if) all bound dye molecules settled with the nanoplastics to the sample vial bottom or stopped their fluorescence due to quenching by the plastic surface. The fluorescence quenching of organic dyes bound to nanoplastics depends on several factors including the photophysical properties of fluorescent dye, the physicochemical properties of nanoplastics, and environmental conditions of water. Dyes that are sensitive to their immediate environment could undergo photo-induced electron transfer or non-radiative decay mechanisms, leading tofluorescence quenching when bound to nanoplastics. The morphology, size, and surface charge of nanoplastics could modulate the quenching. Nanoplastics with higher surface charge density may enhance quenching. Nevertheless, accurate monitoring was made easy by CE-LIF where any nanoplastics carrying bound dye molecules in the sample suspension would migrate through the capillary at a low mobility and appear as a weak broad peak at a different migration time on the electropherogram. This was the main reason why we coupled CE with LIF to develop an advanced method for the accurate determination of aqueous dye concentration (ce) at binding equilibrium. No worries about any potential errors, due to either fluorescence emission from the bound dye molecules or optical attenuation by the polymer nanoparticles, could be an issue.

Conclusion

As a part of the global water/wastewater sector concerning with environmental regulations and standards, rigorous quantification and understanding of contaminants in water are critical. The present work demonstrates how a LIF detector can be built onto a pre-existing CE-UV instrument for the sensitive determination of nanoplastics via their selective binding with organic dyes. The LIF detector can readily be placed anywhere along the length of the capillary, together with a diode laser, interference filter, and avalanche photosensor, without damaging the CE instrument. The original UV detector allows versatile analysis of many aromatic compounds including dyes while the additional LIF detector offers selective analysis of fluorescent dyes without any potential interference by organic compounds of low molecular weight that are commonly found in the aquatic environment. The CE-UV/LIF method has shown a potential to analyze real-world water samples for their nanoplastic content. It is a relatively inexpensive method for water analysis in quality control, public health, and environmental research purposes. For further development in industrial applications, the LIF detector assembly could be miniaturized for use as a retrofittable module to equip any CE-UV instrument that is commonly available in commercial research labs. This CE-based method could be further validated by high-performance liquid chromatography with UV or fluorescence detection, which is commonly accessible, for the versatile monitoring and control of water quality. We envision a future method wherein multiple fluorescent dyes could be used to detect different nanoplastic materials in water. Our studies will focus on developing efficient sample pretreatment techniques for the detection of nanoplastics in various water matrices. Sample treatment by ultrasonic homogenization can prevent aggregation/agglomeration of nanoplastics, prior to water analysis for free/residual dyes by the CE-LIF method. The interaction of nanoplastics with different water constituents requires careful exploration. Chemical methods that control and adjust the surface charge of nanoplastics to achieve better binding with fluorescent dyes would be beneficial. These new binding affinity results would provide a large dataset (dye structures, nanoplastics, matrix interferences) to facilitate water treatment quality control and management. Along with artificial intelligence-machine learning (AI-ML), fluorescent dye-based chemosensors will be better designed for future applications of CE-UV/LIF as one of the next-generation sensing technologies. Nanoplastics in lake/ground/well/tap water samples will be analyzed after sedimentation sorting, microfluidic binding with molecular dyes, CE separation, LIF detection, and barcode chemoinformatics.

Acknowledgement

We would like to thank Olay Chen for his tremendous help with the repair of a data acquisition system.

Data Availability Statement

All data generated or analyzed during this study, as presented in this published article, will be made available to any readers upon request from the corresponding author.

Disclosure Statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the authors.

Funding

Financial support from NSERC Canada (grant number RGPIN-2018-05320) is gratefully acknowledged.

References

- Lai H, Liu X, Qu M (2022) Nanoplastics and human health: hazard identification and biointerface. Nanomaterials (Basel) 12(8): 1298. [crossref]

- Reynaud S, Aynard A, Grassl B, Gigault J (2022) Nanoplastics: From model materials to colloidal fate. Current Opinion in Colloid & Interface Science 57, 101528.

- Gigault J, El Hadri H, Nguyen B, Grassl B, Rowenczyk L, et al. (2021) Nanoplastics are neither microplastics nor engineered nanoparticles. Nature Nanotechnology 16, 501-507 (2021). [crossref]

- Wang J, Zhao X, Wu A, Tang Z, Niu L, et al. (2021) Aggregation and stability of sulfate-modified polystyrene nanoplastics in synthetic and natural waters. Environmental Pollution 268(A), 114240. [crossref]

- Sarkar B, et al. (2022) Challenges and opportunities in sustainable management of microplastics and nanoplastics in the environment. Environmental Research 207, 112179. [crossref]

- Gigault, J, et al. (2018) Current opinion: what is a nanoplastic? Environmental Pollution 235, 1030-1034. [crossref]

- Murray A, et al. (2020) Removal effectiveness of nanoplastics with separation processes used for water and wastewater treatment. Water 12(3), 635.

- Gao S, Orlowski N, Bopf FK, Breuer L (2024) A review on microplastics in major European rivers. WIREs Water e1713.

- Winkler A, Fumagalli F, Cella C, Gilliland D, et al. (2022) Detection and formation mechanisms of secondary nanoplastic released from drinking water bottles. Water Research 222, 118848. [crossref]

- Huang Y, Wong KK, Li W, Zhao H, Wang T, et al. (2022) Characteristics of nano-plastics in bottled drinking water. Journal of Hazardous Materials 424(C), 127404. [crossref]

- Zhang J, Peng M, Lian E, Lu X, Asimakopoulos AG, et al. (2023) Identification of polyethylene terephthalate nanoplastics in commercially bottled drinking water using surface-enhanced Raman spectroscopy. Environmental Science & Technology 57, 22, 8365-8372. [crossref]

- Chen Y, Xu H, Luo Y, Ding Y, Huang J, et al. (2023) Plastic bottles for chilled carbonated beverages as a source of microplastics and nanoplastics. Water Research 242, 120243. [crossref]

- Vega-Herrera A, Garcia-Torné M, Borrell-Diaz X, Abad E, et al. (2023) Exposure to micro(nano)plastics polymers in water stored in single-use plastic bottles. Chemosphere 343, 140106. [crossref]

- Wibuloutai J, Thongkum W, Khiewkhern S, Thunyasirinon C, Prathumchai N (2023) Microplastics and nanoplastics contamination in raw and treated water. Water Supply 23(6), 2267-282.

- Okoffo ED, Thomas KV (2024) Quantitative analysis of nanoplastics in environmental and potable waters by pyrolysis-gas chromatography-mass spectrometry. Journal of Hazardous Materials 464, 133013. [crossref]

- Gambino I, Bagordo F, Grassi T, Panico A, De Donno A (2022) Occurrence of microplastics in tap and bottled water: current knowledge. International Journal of Environmental Research Public Health 19(9), 5283. [crossref]

- Vitali C, Peters RJB, Janssen HG, Nielen MWF (2023) Microplastics and nanoplastics in food, water, and beverages: part I. occurrence. TrAC Trends in Analytical Chemistry 159, 116670.

- Shen M, Zhang Y, Zhu Y, Song B, et al. (2019) Recent advances in toxicological research of nanoplastics in the environment: A review. Environmental Pollution 252(A), 511-521. [crossref]

- Paul MB, Stock V, Cara-Carmona J, Lisicki E, Shopova S, et al. (2020) Micro- and nanoplastics – current state of knowledge with the focus on oral uptake and toxicity. Nanoscale Advances 2, 4350-4367.

- Saavedra J, Stoll S, Slaveykova VI (2019) Influence of nanoplastic surface charge on eco-corona formation, aggregation and toxicity to freshwater zooplankton. Environmental Pollution 252(A), 715-722. [crossref]

- Trevisan R, et al. (2022) Nanoplastics in aquatic environments: impacts on aquatic species and interactions with environmental factors and pollutants. Toxics 10(6), 326. [crossref]

- Feng H, Liu Y, Xu Y, Li S, Liu X, et al. (2022) Benzo[a]pyrene and heavy metal ion adsorption on nanoplastics regulated by humic acid: cooperation/competition mechanisms revealed by molecular dynamics simulations. Journal of Hazardous Materials 424(B), 127431. [crossref]

- Hu S, Mo Y, Luo W, Xiao Z, Jin C, et al. (2022) Aqueous aggregation and deposition kinetics of fresh and carboxyl-modified nanoplastics in the presence of divalent heavy metals. Water Research 222, 118877. [crossref]

- Zhao H, Huang X, Wang L, Zhao X, Yan F, et al. (2022) Removal of polystyrene nanoplastics from aqueous solutions using a novel magnetic material: adsorbability, mechanism, and reusability. Chemical Engineering Journal 430(4), 133122.

- Cortés-Arriagada D (2021) Elucidating the co-transport of bisphenol A with polyethylene terephthalate nanoplastics: a theoretical study of the adsorption mechanism. Environmental Pollution 270, 116192. [crossref]

- Magrì D, Veronesi M, Sánchez-Moreno P, Tolardo V, Bandiera T, et al. (2021) PET nanoplastics interactions with water contaminants and their impact on human cells. Environmental Pollution 271, 116262. [crossref]

- Zhao H, Huang X, Yang Y, Wang L, Zhao X, et al. (2023) The role of available nitrogen in the adsorption of polystyrene nanoplastics on magnetic materials. Water Research 229, 119481. [crossref]

- Zając M, et al. (2023) Exposure to polystyrene nanoparticles leads to changes in the zeta potential of bacterial cells. Scientific Reports 13, 9552. [crossref]

- Cao J, et al. (2022) Coronas of micro/nano plastics: a key determinant in their risk assessments. Particle & Fibre Toxicology 19(1), 1-25. [crossref]

- Balakrishnan G, et al. (2023) Fate of polystyrene and polyethylene nanoplastics exposed to UV in water. Environmental Science: Nano 10, 2448-2458.

- Fakhrullin R, et al. (2021) Dark-field/hyperspectral microscopy for detecting nanoscale particles in environmental nanotoxicology research. Science of The Total Environment 772, 145478. [crossref]

- Hufnagl B, et al. (2022) Computer-assisted analysis of microplastics in environmental samples based on μFTIR imaging in combination with machine learning. Environmental Science & Technology Letters 9(1), 90-95. [crossref]

- Schiavi S, et al. (2023) Plasmonic nanomaterials for micro- and nanoplastics detection. Applied Sciences 13, 9291.

- Shorny A, Steiner F, Hörner H, Skoff SM (2023) Imaging and identification of single nanoplastic particles and agglomerates. Scientific Reports 13, 10275.

- Alink JWM (2023) Quantification of nanoplastics in a baby bottle and a reusable water bottle by fluorescence microscopy and atomic force microscopy. University of Trent student thesis, 97123.

- Fang C, et al. (2023) Microplastics and nanoplastics analysis: options, imaging, advancements and challenges. Trends in Analytical Chemistry 166, 117158.

- Chang L, Jiang S, Luo J, Zhang J, Liu X, et al. (2022) Nanowell-enhanced Raman spectroscopy enables the visualization and quantification of nanoplastics in the environment. Environmental Science: Nano 9, 542-553.

- Vitali C, et al. (2023) Microplastics and nanoplastics in food, water, and beverages: part I. occurrence. Trends in Analytical Chemistry 159, 116670.

- Tornero Q, et al. (2023 Chapter 4 – Methods of sampling and sample preparation for detection of microplastics and nanoplastics in the environment. Current Developments in Biotechnology and Bioengineering Elsevier, 79-97.

- DK Iyer, A Shaji, SP Singh, A Tripathi, A Hazra, et al. (2023) A review on rhodamine probes for metal ion recognition with a future on artificial intelligence and machine learning. Coordination Chemistry Reviews 495, 215371.

- S Sarkar, A Chatterjee, K Biswas (2023) A recent update on rhodamine dye-based sensor molecules: a review. Critical Reviews in Analytical Chemistry. [crossref]

- Sano T, Losakul R, Schmidt H (2023) Dual optofluidic distributed feedback dye lasers for multiplexed biosensing applications. Scientific Reports 13, 16824.

- Wang Y, Wang X, Ma W, Lu R, et al. (2022) Recent developments in rhodamine-based chemosensors: a review of the years 2018-2022. Chemosensors, 10, 399.

- Duarte FJ, Costela A (2013) Dye Lasers. In Encyclopedia of Modern Optics, 2nd edition; Elsevier, 2018.

- Rhodamine 6G (2013) Exciton. Luxottica.

- 4-(Dicyanomethylene)-2-methyl-6-(4-dimethylaminostyryl)-4H-pyran. Exciton. Luxottica, 2013.

- https://exciton.luxottica.com/laser-dyes.html (accessed November 11, 2023).

- Disodium Fluorescein. Exciton. Luxottica, 2013. https://exciton.luxottica.com/laser-dyes.html (accessed November 11, 2023).

- Coumarin 540A. Exciton. Luxottica, 2013. https://exciton.luxottica.com/laser-dyes.html (accessed November 11, 2023).

- Coumarin 503. Exciton. Luxottica, 2013. https://exciton.luxottica.com/laser-dyes.html (accessed November 11, 2023).

- Ali I, et al. (2022) Interaction of microplastics and nanoplastics with natural organic matter (NOM) and the impact of NOM on the sorption behavior of anthropogenic contaminants – a critical review. Journal of Cleaner Production 376, 134314.

- Ioannidis I, et al. (2023) Microplastics and disposable face masks as trojan horse for radionuclides pollution in water bodies – a review with emphasis on the involved interactions. Sustainable Chemistry for the Environment 1, 100005.

- Yang Z, et al. (2023) Micro- and nanoplastics and their potential toxicological outcomes: state of science, knowledge gaps and research needs. NanoImpact 32, 100481. [crossref]

- Qiao J, et al. (2012) Synthesis and properties of chemically cross-linked poly(vinyl alcohol)- PAAm-co-DADMAC for anion-exchange membranes. Solid State Ionics 214, 6-12.

- Feng LJ, et al. (2023) Short-term exposure to positively charged polystyrene nanoparticles causes oxidative stress and membrane destruction in cyanobacteria. Environmental Science: Nano.

- Chen C, Sun C, Wang B, Zhang Z, Yu G (2024) Adsorption behavior of triclosan on polystyrene nanoplastics: The roles of particle size, surface functionalization, and environmental factors. Science of The Total Environment 906, 167430.

- DeMessie JA, Sorial GA, Sahle-Demessie E (2022) Chapter 9 – Removing chromium (VI) from contaminated water using a nano-chitosan-coated diatomaceous earth. Separations of Water Pollutants with Nanotechnology 15, 163-176.

- Chiban M, Soudani A, Sinan F, Persin M (2011) Single, binary and multi-component adsorption of some anions and heavy metals on environmentally friendly Carpobrotus edulis plant. Colloids and Surfaces B: Biointerfaces 82(2), 267-276. [crossref]

- Babayemi AK, Onukwuli OD (2017) Equilibrium studies and optimization of phosphate adsorption from synthetic effluent using acid modified bio-sorbent. American Journal of Engineering and Applied Sciences 10 (4): 980-991.

- Lesmana SO, Febriana N, Soetaredjo FE, Sunarso J, Ismadji S (2009) Studies on potential applications of biomass for the separation of heavy metals from water and wastewater. Biochemical Engineering Journal 44(1), 19-41.

- Mchedlov-Petrossyan NO, Kukhtik VI, Alekseeva VI (1994) Ionization and tautomerism of fluorescein, rhodamine B, N,N-diethylrhodol and related dyes in mixed and nonaqueous solvents. Dyes and Pigments 24(1), 11-35.

- Ramirez L, Ramseier Gentile S, Zimmermann S, Stoll S (2019) Behavior of TiO2 and CeO2 nanoparticles and polystyrene nanoplastics in bottled mineral, drinking and Lake Geneva waters: Impact of water hardness and natural organic matter on nanoparticle surface properties and aggregation. Water 11, 721. [crossref]

- Al-Kandari H, Kasák P, Mohamed A, Al-Kandari S, Chorvat D, et al. (2018) Toward an accurate spectrophotometric evaluation of the efficiencies of photocatalysts in processes involving their separation using nylon membranes. Catalysts 8, 57.