Abstract

Introduction/Objective: The scope of this review is a critical appraisal of the efficacy and safety of regulatory authorities-approved, commercially available Hybrid Closed-Loop Systems compared to conventional treatments in individuals with Type 1 diabetes

Methods: Medline and Embase databases were searched for Randomized Controlled Trials (RCT), meta-analyses of RCTs and Real-World studies using the terms hybrid closed-loop systems, automated insulin delivery systems and artificial pancreas.

Results: Limited data from Randomized Controlled Trials and meta-analyses and growing evidence from real-world use support the superiority of Hybrid Closed-Loop Systems in improving all the Ambulatory Glucose Profile metrics compared to Sensor Augmented Pumps or Multiple Daily Injections with Continuous Glucose Monitoring.

Conclusion: Commercially available Hybrid Closed-Loop Systems are effective in reducing HbA1c, increasing Time In Range and decreasing time in the hypoglycemic range in individuals with Type 1 diabetes.

Keywords

Hybrid closed-loop systems, Artificial pancreas, Type 1 diabetes, Hypoglycemia, Time in range, Severe hypoglycemia, Diabetic ketoacidosis

Introduction

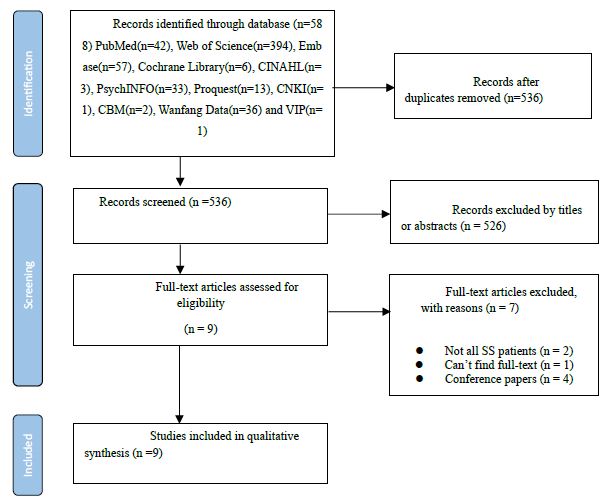

Despite progress in the treatment of Type 1 Diabetes (T1D), less than one third of patients achieve optimal glycemic control [1,2]. Emerging technologies by means of newer insulin pumps, more reliable glucose sensors and efficient control algorithms drive a paradigm shift in the treatment of diabetes. Hybrid Closed-Loop Systems (HCLS), or else Automated Insulin Delivery (AID) systems represent the most advanced currently available treatment for T1D. These systems integrate data from Continuous Glucose Monitoring (CGM), a control algorithm and an insulin pump into an automated glucose-responsive subcutaneous insulin infusion. Mimicking basal endogenous insulin production, HCLS automatically modify insulin infusion rates during fasting state thus eliminating patients’ involvement with the self-management of diabetes to prandial boluses that are still given manually through a user-initiated procedure [3]. Three main classes of control algorithms are currently used to determine the insulin infusion rates in HCLS: Model Predictive Control (MPC) uses inputs such as Insulin to Carbohydrates Ratio (ICR), Active Insulin Time (AIT), glucose target and insulin sensitivity to build and update an individually customized algorithm. The Proportional-Integral-Derivative (PID) algorithm modifies insulin infusion rates in response to glucose increments (proportional component), difference from preset glycemic target (integral component), and the rate of glucose fluctuation (derivative component). Finally, Fuzzy logic algorithms combining elements of the other two mimic the decision-making of diabetes clinicians based on the current state of the user and accommodating day-to-day variations [4]. Fully closed-loop systems that require no user intervention are under investigation.This narrative review investigates the efficacy and safety of the commercially available HCLS. Medline and Embase databases were searched for Randomized Controlled Trials (RCT), meta-analyses of RCTs and Real-World studies published up to 31.01.2024 using the terms hybrid closed-loop systems, automated insulin delivery systems and artificial pancreas. The psychosocial impact and the cost effectiveness of HCLS are beyond the aims of this review.

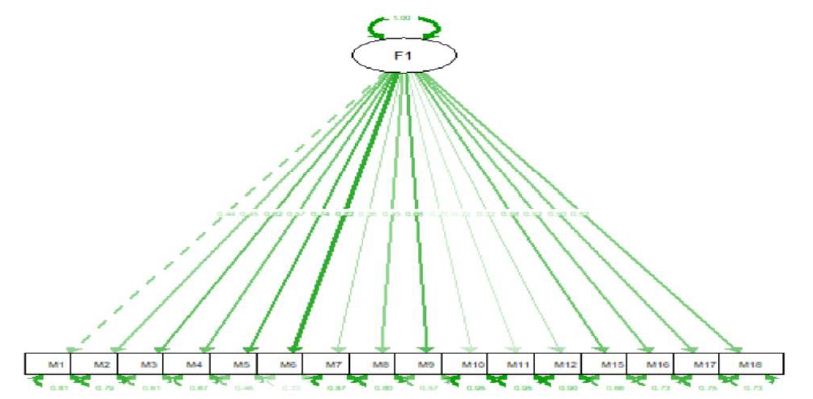

Commercially Available Regulatory Authorities Approved HCLS

The Medtronic 670G was the first HCLS cleared by the U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA) and the Conformitè Européenne (CE) for ages above 7 years [5]. It was initially upgraded to the 770G (FDA approved, licensed for age 2 and above) and finally to the 780G (CE marked, licensed for age 7-80 years). Also known as the Advanced Hybrid Closed Loop (AHCL), the 780G incorporates Bluetooth connectivity and remote software updates. In addition, 780G automatically deliver correction boluses while maintenance in auto mode is substantially increased compared to 670G [6]. Medtronic’s PID algorithm is installed in the pump. Initiation of the auto-mode requires Insulin to Creatinine Ratio (ICR), Active Insulin Time (AIT) and glucose target. Two glucose sensors are compatible with the 780G: Guardian 3 lasts up to 7 days and requires at least 2 calibrations per day ,while the recently launched Guardian 4 requires no calibrations.

CamAPS FX (CamDiab, Cambridge, UK) is a HCLS using a MPC algorithm embedded into an Android smartphone. Both Dexcom G6 glucose sensors which last for 10 days and require no calibration and Libre 3 CGM devices are compatible with the algorithm. Insulin infusion is mediated by Dana RS, Dana I or YpsoPump insulin pumps. CamAPS FX is, for the time being, the only HCLS licensed by CE for use from 1 year upwards and in pregnancy [7,8]. It is also the HCLS where both rapid and ultra-rapid insulin analogues have been tested in clinical studies. In addition, CamAPS FX allows for multiple glucose targets to be set at different times.

Control IQ HCLS combines the Tandem t: slim X2 insulin pump with a MPC algorithm incorporated, the Dexcom G6 glucose sensor, and the Control-IQ technology. It is approved by both FDA and CE for use in ages 6 and above, but not during pregnancy. Augmented by total daily insulin dose and a preset basal program the Control-IQ algorithm predicts glucose value thirty minutes in advance adapting insulin infusion rate to achieve a preset glucose target which can be differentiated during nighttime and before announced exercise [6].

The Insulet Omnipod 5 combines a patch insulin pump, operated by a wireless handheld device with the Dexcom G6 CGM. It is the first tubeless HCLS cleared by FDA and CE marked for T1D patients aged 2 years or older. It is not approved for use during pregnancy. The adaptive MPC algorithm installed in the Omnipod 5 pump and Omnipod 5 application is initiated using total daily insulin dose and delivers insulin micro-boluses every 5min [9].

The Diabeloop Generation 1 (DBLG1) HCLS is a combination of Kaleido patch pump or Roche Accu-check pump, with Dexcom G6 glucose sensor, and a command module running the system’s MPC algorithm. It has received the CE mark for use in adults with T1D and is available in some countries in Europe [3]. A partly differentiated version of DBLG1, the Diabeloop for Highly Unstable Type 1Diabetes (DBLHU) has been recently approved in Europe for use by individuals with unstable diabetes [10].

Data from RCTs

The efficacy and safety of HCLS have been tested in a limited number of RCTs. In most of these crossover trials the number of participants was small, and the duration of intervention did not exceed six months.

Mc Auley et al. compared 670G HCLS to conventional treatment with Multiple Daily Injections (MDI) or insulin pump in adults with T1D. After 6 months intervention HbA1c was lower (-0.4%; -4mmol/mol, p<0.0001) and Time In Range (TIR) 70-180mg/dl; 3.9-10mmol/l was 15% higher (p<0.0001) with HCLS [11]. In a 4-week periods, crossover study, in AID naïve patients with T1D aged 7-80 years Collyns at al. compared 780G or Advanced Hybrid Closed-Loop System (AHCL) to therapy with Sensor Augmented Pump (SAP) with a Predictive Low Glucose Suspend (PLGS) algorithm. At the end of the study TIR was higher with AHCL (70.4% ± 8.1% vs. 57.9% ± 11.7%) by 12.5% ± 8.5% (p< 0.001), The improvement in TIR was even greater overnight (18.8 ± 12.9%, p<0.001) and in adolescents and young adults group (14-21 years) (14.4%±8.4%). During AHCL therapy, time with glucose <70 mg/dL,3.9mmol/l significantly decreased from 3.1%±2.1% to 2.1% ± 1.4% (p= 0.034) [12]. In the ADAPT study, 82 adults with T1D were randomly assigned to AHCL treatment or continuation of the conventional treatment with MDI combined with CGM. At 6 months, mean HbA1c decreased by 1.54%, from 9.0% to 7.32%, in the AHCL group and by 0.20%, from 9.07% to 8.91%, in the MDI plus CGM (between AHCL and MDI mean difference −1.42%, 95% CI −1.74% to −1.10%, p<0.0001) [13]. In a small, 12-week periods, crossover study 780G was superior to 670G in reducing HbA1c (mean difference -0.2%, p=0.03) and in increasing TIR (4%, p<0.0001) with no difference in hypoglycemia [14].

The CamAPS FX HCLS has been tested in a broad population of patients with T1D from children 1 year old, to elderly individuals and pregnant women. Tauschmann et al compared HCLS to treatment with SAP with the threshold suspend and PLGS features inactivated in individuals with T1D from the age of 6 years. After 12 weeks intervention, HbA1c was significantly lower (mean difference 0.36%, 95% CI 0.19% to 0.53%, p<0.0001) and TIR was significantly higher (65%± 8% vs 54%± 9%, mean difference 10.8%, 95% CI: 8.2% to 13.5%, p<0.0001) with HCLS compared to SAP. The time with glucose values within the ranges of hypoglycemia (<70mg/dl;3.9mmol/l) and hyperglycemia (>180mg/dl;10.0mmol/l) was also significantly reduced by -0.83%, 95% CI -1.40% to -0.16%, p=0.0013 and -10.3%, 95% CI -13.2% to -7.5%, p<0.0001, respectively with HCLS treatment compared to SAP. Severe adverse events were restricted to one episode of Diabetic Ketoacidosis (DKA) due to infusion set occlusion in the HCLS group, while no episodes of severe hypoglycemia were reported with either treatment Adverse events were numerically more in the HCLS group (13 vs 3) [15]. In another randomized crossover study adults previously treated with an insulin pump were assigned to HCLS therapy or continuation of insulin pump treatment for periods lasting 4 weeks. Compared to conventional insulin pump treatment, HCLS increased TIR by 10.5 percentage points;95% CI 7.6% to 13.4%, p<0.0001 and reduced time in the hypoglycemia range <3.5 mmol/L and <2.8 mmol/L by 65% and 76%,respectively (p<0.0001 for both comparisons), without increasing the risk of severe hypoglycemia or DKA [16]. Similarly, Thabit et al. reported decrease in HbA1c (mean difference −0.3%; 95% CI −0.5% to −0.1%, p=0.002) and 11% increase in TIR (95% CI, 8.1% to 13.8%) in adults treated with HCLS compared to SAP therapy [17]. In another multicenter, crossover trial,74 children 1 to 7 years old with T1D previously on insulin pump were randomized to receive HCLS or SAP treatment for two 16-week periods. During the closed-loop treatment TIR increased by 8.7 percentage points (95% CI, 7.4% to 9.9%, p<0.001) and HbA1c decreased by 0.4 percentage points (95% CI, −0.5% to −0.3%), while time spent in hypoglycemia was similar with the two treatments (p =0.74). One episode of severe hypoglycemia occurred during treatment with HCLS [18]. The efficacy and safety of CamAPS FX HCLS was also tested in16 pregnant women with T1D and gestational age 8-24 weeks randomized to receive closed-loop treatment or therapy with SAP without the option of PLGS. HbA1c, TIR and Time in Hyperglycemia>140mg/dl were comparable between HCLS and SAP. However, the incidence of hypoglycemia (median number of episodes over 28 days treatment: 8 vs 12, p=0.04) as well as the time with glucose values below 63mg/dl (1.6% vs 2.7%, p=0.02) and below 50mg/dl (0.24% vs 0.47%, p=0.03) favoured treatment with HCLS. Nocturnal hypoglycaemia (23: 00-07: 00 h) was also lower with HCLS treatment (1.1% vs 2.7%; p=0.008) [19]. Finally, in a randomized crossover trial 37 patients≥60 years old were enrolled to receive treatment with CamAPS FX HCLS or SAP therapy. After two 16-week periods, individuals assigned to HCLS treatment achieved significantly higher TIR (79.9% vs 71.4% p<0.0001). Severe hypoglycemia occurred twice during SAP period [20].

Four RCTs investigated the performance of the Control-IQ HCLS in a broad population of individuals with T1D. In a 6-month, multicenter trial,168 patients, at least 14 years old, with T1D were randomized to therapy with HCLS, or SAP. At the end of intervention the results for all the prespecified endpoints favoured treatment with HCLS. The TIR 70-180mg/dl increased by 11% (95%CI, 9% to 14%, p<0.001) with concomitant decrease in time with glucose below 70mg/dl by 0.88% (95% CI, −1.19% to −0.57%, p<0.001) and in HbA1c by 0.33% (95% CI, −0.53% to −0.13%, p = 0.001). Treatment with HCLS was safe with no episodes of severe hypoglycemia and one episode of DKA [21]. In another 16-week, multicenter trial, 101 young children between 6 and 13 year-old with T1D were randomized to treatment with HCLS or SAP. Compared to SAP, HCLS treatment increased the TIR 70-180mg/dl by 11% (95% CI, 7% to 14%, p<0.001) adding 2.6 hours of euglycemia per day, with no episodes of DKA or severe hypoglycemia [22]. Recently, in a trial lasting 13 weeks, 102 children with T1D between 2 and 6-year-old were randomized to receive treatment with HCLS or conventional treatment with either an insulin pump or MDI plus a CGM. HCLS treatment resulted in an increase in TIR 70-180mg/dl by 12.4% (95% CI, 9.5% to 15.3%, p<0.001) adding about 3 hours of euglycemia per day. HbA1c and time with glucose values below 70 mg/dl were comparable between the two interventions. Two episodes of severe hypoglycemia and one episode of DKA occurred during treatment with HCLS, while one case of severe hypoglycemia occurred during conventional treatment [23]. Finally, Control-IQ HCLS was compared with insulin pump and CGM treatment in 72 adults with impaired hypoglycemia perception defined as Clarke score >3 and/or history of severe hypoglycemia within the last 6 months. After 12 weeks intervention HCLS treatment resulted in significant reduction in time with glucose below 70mg/dl (TBR) by 23.7% (95% CI 24.8% to 22.6%, p < 0.001). In addition, TIR 70-180mg/dl increased by 8.6% (95% CI 5.2% to 12.1%, p < 0.001), and Time in hyperglycemia above 180mg/dl (TAR) decreased by 25% (95% CI 87.7% to 1.8%, p=0.004) [24].

The DBLG1 HCLS was compared to SAP in 63 adults withT1D and preserved hypoglycemia awareness. After 12-week periods interventions TIR 70-180mg/dl increased by 9.2% (95% CI 6.4% to 11.9%, p<0.0001) with HCLS compared to SAP treatment [25]. In another RCT, DBLG1 HCLS was compared to SAP in children aged 6-12. After 13 weeks, treatment with HCLS decreased time in the hypoglycemic range below 70mg/dl (2.04% with HCLS vs 7.06% with SAP, p<0.001), without episodes of severe hypoglycemia or DKA [26]. The DBLHU HCLS, derived from DBLG1, was tested in a randomized, controlled study that comprised 2 circles of N-of-1 trials in 5 adults with TID with severe glucose instability that could lead to eligibility for islet transplantation. Compared to SAP with PLGS feature activated, DBLHU treatment resulted in significantly higher TIR 70-180mg/dl (73.3%±1.7% vs 43.5%±1.7%, p<0.0001) and lower time with glucose<70mg/dl (0.9%±0.4% vs 3.7%±0.4%, p<0.0001) with no adverse events reported [10].

Data from Meta-analyses of RCTs

Six meta-analyses reported data from RCTs comparing intervention with a HCLS to other standard treatments for T1D such as MDI with Self-Monitoring of Blood Glucose (SMBG), flash or Continuous Glucose Monitoring, Continuous Subcutaneous Insulin Infusion (CSII), SAP and SAP with PLGS [27-32]. In all meta-analyses the intervention with HCLS was associated with significant increase in TIR 70-180mg/dl for sensor glucose. This increase ranged from 6.2% when HCLS was used during exercise to 17.9% when HCLS was compared to MDI with SMBG [29,30]. Time Below the Range of 70mg/dl (TBR) was significantly reduced by 1.09%, 1.49% and 2.45% in three meta-analyses remaining unchanged in the rest of them [27,31,32]. Similarly, a significant decrease in Time Above the Range of 180mg/dl (TAR) 8.5% and 8.9% was reported in two of the meta-analyses [27,31]. Overall, the existing meta-analyses comprising data from a wide range of patients and interventions in outpatient settings have shown the superiority of HCLS over conventional treatments in increasing time in euglycemia and reducing time in hypoglycemia in individuals with T1D.

Real-World Data

As commercial availability and affordability of HCLS increases, more and more people with T1D use technology for their treatment. However, reimbursement status, and socioeconomic criteria may still limit the access to advanced technology treatments to a large number of individuals with diabetes that could potentially benefit from it [1,33]. Evidence from real-world use of HCLS capture information from a broader patient population, such as those with bad glucose control and hypoglycemia unawareness, often under-represented in clinical trials. In addition, longer use of HCLS under real-life conditions may reveal adverse events and potential interactions with comorbidities that could not emerge during short-time intervention in a clinical trial.

Recently, Arunachalum et al. reported glycemic outcomes during real-world 670G HCLS use by a large cohort of 123,355 individuals with T1D in the United States. Compared with pre-670G initiation, HCLS users with a baseline Glucose Management Index (GMI) above 7% showed significant decrease in GMI from 7.3%± 0.6% to 7.1%± 0.5% (p <0 .001), in TBR<70 mg/dL, from 2.11%±2.4% to 2.07%± 2.25% (p = 0.002), and in TAR>180 mg/dL from 36.3%±15.7% to 29.8%±12.2% (p<0 .001), while TIR substantially increased from 61.5%± 15.1% to 68.1% ±11.9% (p <0.001). In users previously well-controlled with GMI<7%, TIR remained unchanged with HCLS treatment [34]. These results are in accordance with outcomes reported from numerous previous real-world studies with the use of 670G [35-45].

Outcomes from real-world use of 780G AHCLS from 4,120 individuals with T1D were reported by Da Silva et al. Treatment with AHCLS resulted in multiple glycemic targets achievement in almost 80% of individuals, with mean GMI 6.8%±0.3%, TIR 70-180mg/dl 76.2%± 9.1%, TBR<70mg/dl 2.5%± 2.1%, and TAR >180mg/dl 21.3%±9.4%. Compared to the previous treatment (data available for 812 individuals) AHCLS further reduced GMI by 0.4% ± 0.4% (p = 0.005) and increased TIR by 12.1%±10.5% (p < 0.0001). Almost 75% of AHCLS users achieved both the glycemic targets of GMI <7.0% and TIR>70% [46]. In another real-world study, treatment with 780G resulted in significant improvement in all ambulatory glucose profile metrics with decrease in mean GMI from 7.9 ± 2.1% to 6.95 ± 0.58%, increase in TIR from 63.48 ± 10.14% to 81.54 ± 8.43%, and substantial decrease in time spent in the hyperglycemic (>180mg/dl) and in the hypoglycemic (<70mg/dl) range [47].

The performance of CamAPS FX HCLS was analyzed with real-world evidence from 1,805 users across different age groups and countries. TIR (70-180mg/dl, 3.9-10 mmol/L) ranged from 66.9±11.7% in children younger than 6 years to 81.8± 8.7% in elderly above 65 years with the mean TIR for all users being 72.6±11.5%. TBR (<70mg/dl, 3.9 mmol/L) was 2.3% while mean sensor glucose and GMI were 151±20mg/dl, 8.4± 1.1 mmol/L and 6.9%, respectively. Adherence to closed loop use was as high as 94.7% [48]. Ng et al. reported also significant improvement in HbA1c (pre-HCLS: 7.9±3.2%, 63±12mmol/mol, at 3 months: 7.3±3.0%, 56.6 ± 9.3mmil/mol, p=0.03), TIR (at baseline 50.5±17.4%, at 3 months 67.0± 14%,p=0.001), and TBR (at baseline 4.3±1.6%, at 3 months 2.8±1.4%,p=0.004) after 3-months real life use of CamAPS FX HCLS from a small cohort of individuals with T1D [49].

Results from real-world performance of Control-IQ HCLS were reported by Breton and Kovatchev analyzing retrospectively data from 9,451 individuals using the HCLS for at least 12 months. Median TIR 70–180 mg/dL increased from 63.6 % (IQR: 49.9%–75.6%) to 73.6% (IQR: 64.4%–81.8%) after 12 months use of Control-IQ technology remaining stable thereafter. Median TBR <70 mg/dL was 1% at baseline and did not change with HCLS treatment [50]. In the Control-IQ Observational (CLIO) study almost 3,000 individuals with T1D older than 6 years initiated treatment with theControl-IQ HCLS and were longitudinally observed in real-world focusing primarily on adverse events (AE) such as severe hypoglycemia and DKA. AEs were reported every month over a period of 12 months and were compared to data available from the participants in the T1D Exchange cohort. Rates of severe hypoglycemia were significantly lower than those expected from conventional treatment both for children (9.31 vs. 19.31 events/100 patient years, p< 0.01) and adults (9.77 vs. 29.49 events/100 patient years, p< 0.01). DKA incidence was also significantly lower in all HCLS users. AEs incidence was lower for all the range of baseline HbA1c and was independent to prior treatment. TIR 70–180mg/dL was 70.1% for adults, 61.2% for ages 6–13, 60.9% for ages14–17, and 67.3% overall. Less self-involvement in the management of diabetes was steadily reported by most of the users [51].

Real-world performance of DBLG1 HCLS was assessed in a small cohort of T1D individuals. After 6 months, HCLS therapy resulted in decrease in HbA1c from 7.9%, 63 mmol/mol, to 7.1%,54 mmol/mol (p<0.001), increase in TIR 70-180 mg/dL from 53% to 69.7% (p<0.0001), and decrease in TBR <70 mg/dl from 2.4% to 1.3% (p=0.03), without episodes of severe hypoglycemia or DKA [52]. In a retrospective observational study, real world use of Omnipod 5 HCLS from a cohort of 179 individuals with T1D resulted in reduction of HbA1c by a mean of -0.2±1.0%, p=0.005 [53].

Recently, Crabtree et al. reported data from 520 HCLS users with T1D followed-up for a median of 5.1 months after initiation of any of the available in England HCLS. Treatment with HCLS reduced HbA1c by 1.7%,18.1mmol/mol (95% CI 1.5%,16mmol/mol to 1.8%,19.6mmol/mol p < 0.0001), and increased TIR 70–180 mg/dl from 34.2% to 61.9% (p< 0.001). More users on HCLS treatment achieved optimal glycemic control defined as HbA1c≤7.5%,58 mmol/mol (from 0% at baseline to 39.4%, p < 0.0001) and TIR 70-180mg/dl≥70% with TBR 70mg/dl <4% (from 0.8 at baseline to 28.2%, p < 0.0001). Almost all participants reported improvement in the quality of their life with HCLS therapy [54].

Future Perspectives

Several other closed-loop systems, such as Tidepool Loop MPC algorithm, Inreda PID algorithm and the iLet bionic pancreas, are under clinical investigation, or at the final stage to receive approval by regulatory authorities [55]. Compared to other HCLS, iLet bionic pancreas allows for a qualitative approach to meal announcement defining a scheduled meal as usual, bigger or smaller than usual thus alleviating the burden of accurate carbohydrates counting [56]. Do-It-Yourself (DIY) Artificial Pancreas Systems are based on the combination of existing CGMs and pumps with open-source algorithms engineered mostly by individuals experienced in self-management of their diabetes and embedded within a smart device. While there are still concerns about safety, preliminary data demonstrate an efficacy comparable to that of licensed systems [57].

Dual Hormone (DH) artificial pancreas combines insulin with glucagon or pramlintide. Although DH systems seem to better mimic normal pancreatic function, results from clinical trials have not so far shown superiority over single hormone systems in outpatient settings [58,59]. New algorithms that incorporate more detailed data such as pulse rate, sweat, movements and step count in glucose management are under development and may be a step ahead to the fully closed-loop systems that require no intervention from the user [60,61]

Conclusions

Commercially available HCLS are effective in reducing HbA1c, increasing TIR and decreasing time spent in hypoglycemia in individuals with T1D. Although data from RCTs are limited for some of these systems, real-world data from thousands of current users confirm the efficacy and safety already established in the environment of clinical trials in a broad age population from early childhood to older adults. Areas that need further investigation include the use of HCLS in pregnancy and during exercise as well as the management of meals. Technology can alleviate much of the daily burden of people with T1D. However, the cost of HCLS and the existing reimbursement disparities may discourage many people with T1D and suboptimal glycemic control from using technology, contributing to socioeconomics and geographical inequities in the treatment of T1D.

Disclosures and Declarations

All the authors declare no conflict of interest for this review. There was no funding for this work. Konstantinos Kitsios had the idea for the article, performed the literature search and wrote the initial draft. Christina-Maria Trakatelli and Maria Sarigianni participated in literature search and revised the work. All the authors vouch for the accuracy of the data presented in this review and approve the submission.

References

- Foster NC, Beck RW, Miller KM, et al. State of Type 1 diabetes management and outcomes from the T1D Exchange in 2016-2018. Diabetes Technol Ther 2019. [crossref]

- NHS Digital. National Diabetes Audit 2017-18. Report 1: Care processes and treatment targets, full report2019, England and Wales,13th June 2019. Leeds: NHS Digital; 2019.

- Boughton CK, Hovorka R. New closed-loop insulin systems. Diabetologia 2021. [crossref]

- Youssef JE, Castle J, Ward WK. A review of closed-loop algorithms for glycemic control in the treatment of type 1 diabetes. Algorithms 2009

- Bergenstal RM, Garg S, Weinzimer SA, et al. Safety of a hybrid closed-loop insulin delivery system in patients with type 1 diabetes. JAMA. 2016. [crossref]

- Sherwood JS, Russell SJ, Putman MS. New and emerging technologies in type 1 diabetes. Endocrinol Metab Clin N Am. 2020. [crossref]

- Ware J, Allen JM, Boughton CK, et al. Randomized trial of closed-loop control in very young children with type 1 diabetes. N Engl J Med. 2022. [crossref]

- Stewart ZA, Wilinska ME, Hartnell S, et al. Day-and-night closed-loop insulin delivery in a broad population of pregnant women with type 1 diabetes: a randomized controlled crossover trial. Diabetes Care. 2018. [crossref]

- Cobry EC, Berget C, Messer LH, Forlenza GP. Review of the Omnipod 5 automated glucose control system powered by Horizon TM for the treatment of type 1 diabetes. Ther Deliv. 2020. [crossref]

- Benhamou PY, Lablanche S, Vambergue A, Doron M, Franc S, Charpentier G. Patients with highly unstable type 1 diabetes eligible for islet transplantation can be managed with a closed-loop insulin delivery system: a series of N-of-1 randomized controlled trials. Diabetes Obes Metab. 2021. [crossref]

- McAuley SA, Lee MH, Paldus B, et al. Six months of hybrid closed-loop versus manual insulin delivery with fingerprick blood glucose monitoring in adults with type 1 diabetes: a randomized, controlled trial. Diabetes Care. 2020. [crossref]

- Collyns O, Meier R, Betts Z, et al 199-OR: Improved Glycemic Outcomes with Medtronic Minimed Advanced Hybrid Closed-Loop Delivery: Results from a Randomized Crossover Trial Comparing Automated Insulin Delivery with Predictive Low Glucose Suspend in People with Type 1 Diabetes. Diabetes 2020. [crossref]

- Choudhary P, Kolassa R, Keuthage W, et al. Advanced hybrid closed loop therapy versus conventional treatment in adults with type 1 diabetes (ADAPT): a randomised controlled study. Lancet Diabetes Endocrinol. 2022;10(10): 720-731. [crossref]

- Bergenstal RM, Nimri R, Beck RW, et al A comparison of two hybrid closed-loop systems in adolescents and young adults with type 1 diabetes (FLAIR): a multicentre, randomised, crossover trial. The Lancet 2021. [crossref]

- Tauschmann M, Thabit H, Bally L, et al. Closed-loop insulin delivery in suboptimally controlled type 1 diabetes: a multicentre, 12-week randomised trial. 2018. [crossref]

- Bally L, Thabit H, Kojzar H, et al. Day-and-night glycaemic control with closed-loop insulin delivery versus conventional insulin pump therapy in free-living adults with well controlled type 1 diabetes: an open-label, randomised, crossover study. Lancet Diabetes Endocrinol 2017. [crossref]

- Thabit H, Tauschmann M, Allen JM, et al (2015) Home Use of an Artificial Beta Cell in Type 1 Diabetes. New Engl J Med 2015. [crossref]

- Ware J, Allen JM, Boughton CK, et al. Randomized trial of closed-loop control in very young children with type 1 diabetes. N Engl J Med. 2022. [crossref]

- Stewart ZA, Wilinska ME, Hartnell S, et al. Day-and-night closed-loop insulin delivery in a broad population of pregnant women with type 1 diabetes: a randomized controlled crossover trial. Diabetes Care. 2018. [crossref]

- Boughton CK, Hartnell S, Thabit H, et al. Hybrid closed-loop glucose control compared with sensor augmented pump therapy in older adults with type 1 diabetes: an open-label multicentre, multinational, randomised, crossover study. Lancet Healthy Longev. 2022. [crossref]

- Brow SA, Kovatchev BP, Raghinaru D, Lum JW, Buckingham BA, Kudva YC, et al. Six-month randomized, multicenter trial of closed-loop control in type 1 diabetes. N Engl J Med 2019. [crossref]

- Breton MD, Kanapka LG, Beck RW, Ekhlaspour L, Forlenza G, Cengiz E, et al. A randomized trial of closed-loop control in children with type 1 diabetes. N Engl J Med 2020. [crossref]

- Wadwa PR, Reed ZW, Buckingham BA, DeBoer MD, Ekhlaspour L, Forlenza GP. Trial of hybrid-closed-loop control in young children with type 1 diabetes. N Engl J Med 2023. [crossref]

- Renard E, Joubert M, Villard O, Dreves B, Reznik Y, Farret A, et al. Safety and Efficacy of Sustained Automated Insulin Delivery Compared With Sensor and Pump Therapy in Adults With Type 1 Diabetes at High Risk for Hypoglycemia: A Randomized Controlled Trial. Diabetes Care 2023. [crossref]

- Benhamou PY, Franc S, Reznik Y, et al. Closed-loop insulin delivery in adults with type 1 diabetes in real-life conditions: a 12-week multicentre, open-label randomised controlled crossover trial. Lancet Digit Health 2019. [crossref]

- Kariyawasam D, Morin C, Casteels K, et al. Hybrid closed-loop insulin delivery versus sensor-augmented pump therapy in children aged 6–12 years: a randomised, controlled, cross-over, non-inferiority trial. Lancet Digit Health 2022. [crossref]

- Jiao X, Shen Y, Chen Y. Better TIR, HbA1c, and less hypoglycemia in closed-loop insulin system in patients with type 1 diabetes: a meta-analysis. BMJ Open Diabetes Res Care. 2022. [crossref]

- Fang Z, Liu M, Tao J, Li C, Zou F, Zhang W. Efficacy and safety of closed-loop insulin delivery versus sensor-augmented pump in the treatment of adults with type 1 diabetes: a systematic review and meta-analysis of randomized-controlled trials. J Endocrinol Invest. 2022. [crossref]

- Eckstein ML, Weilguni B, Tauschmann M, et al. Time in range for closed-loop systems versus standard of care during physical exercise in people with type 1 diabetes: a systematic review and meta- analysis. J Clin Med. 2021. [crossref]

- Pease A, Lo C, Earnest A, Kiriakova V, Liew D, Zoungas S. Time in range for multiple technologies in type 1 diabetes: a systematic review and network meta-analysis. Diabetes Care. 2020. [crossref]

- Bekiari E, Kitsios K, Thabit H, et al. Artificial pancreas treatment for outpatients with type 1 diabetes: systematic review and meta- analysis. 2018. [crossref]

- Weisman A, Bai JW, Cardinez M, Kramer CK, Perkins BA. Effect of artificial pancreas systems on glycaemic control in patients with type 1 diabetes: a systematic review and meta-analysis of outpatient randomized controlled trials. Lancet Diabetes Endocrinol. 2017. [crossref]

- Rytter K, Madsen KP, Andersen HU, et al. Insulin pump treatment in adults with type 1 diabetes in the capital region of Denmark: design and cohort characteristics of the steno tech survey. Diabetes Ther. 2022. [crossref]

- Arunachalum S, Velado K, Vigersky RA, Cordero TL. Glucemic outcomes during real-world hybrid closed-loop system use by individuals with type 1 diabetes in the United States. J Diabetes Sci Technol 2023. [crossref]

- Petrovski G, al Khalaf F, Campbell J, Umer F, Almajaly D, Hamdan M, Hussain K One-year experience of hybrid closed-loop system in children and adolescents with type 1 diabetes previously treated with multiple DAILY injections: drivers to successful outcomes. Acta Diabetol 2020. [crossref]

- Salehi P, Roberts AJ, Kim GJ. Efficacy and safety of real-life usage of MiniMed 670G automode in children with type 1 diabetes less than 7 years old. Diabetes Technol Ther 2019. [crossref]

- Stone MP, Agrawal P, Chen X, Liu M, Shin J, Cordero TL, Kaufman FR Retrospective analysis of 3-month real-world glucose data after the minimed 670G system commercial launch. Diabetes Technol Ther 2018. [crossref]

- Beato-Víbora PI, Gallego-Gamero F, Lázaro-Martín L, Romero-Pérez M del M, Arroyo-Díez FJ. Prospective Analysis of the Impact of Commercialized Hybrid Closed-Loop System on Glycemic Control, Glycemic Variability, and Patient-Related Outcomes in Children and Adults: A Focus on Superiority over Predictive Low-Glucose Suspend Technology. Diabetes Technol Ther 2020. [crossref]

- Akturk HK, Giordano D, Champakanath A, Brackett S, Garg S, Snell-Bergeon J. Long-term real-life glycemic outcomes with a hybrid closed-loop system compared with sensor-augmented pump therapy in patients with type 1 diabetes. Diabetes Obes Metab 2020.[crossref]

- Usoh CO, Johnson CP, Speiser JL, Bundy R, Dharod A, Aloi JA. Real-World Efficacy of the Hybrid Closed-Loop System. J Diabetes Sci Technol 2021. [crossref]

- Lal RA, Basina M, Maahs DM, Hood K, Buckingham B, Wilson DM. One year clinical experience of the first commercial hybrid closed-loop system. Diabetes Care 2019. [crossref]

- Lepore G, Scaranna C, Corsi A, Dodesini AR, Trevisan R. Switching from Suspend-Before-Low Insulin Pump Technology to a Hybrid Closed-Loop System Improves Glucose Control and Reduces Glucose Variability: A Retrospective Observational Case-Control Study. Diabetes Technol Ther 2020. [crossref]

- Faulds ER, Zappe J, Dungan KM. Real-world implications of hybrid close loop (HCl) insulin delivery system. Endocrine Practice 2019.

- Berget C, Messer LH, Vigers T, Frohnert BI, Pyle L, Wadwa RP, Driscoll KA, Forlenza GP. Six months of hybrid closed loop in the real-world: An evaluation of children and young adults using the 670G system. Pediatr Diabetes 2020.

- Duffus SH, Ta’ani Z al, Slaughter JC, Niswender KD, Gregory JM. Increased proportion of time in hybrid closed-loop “Auto Mode” is associated with improved glycaemic control for adolescent and young patients with adult type 1 diabetes using the MiniMed 670G insulin pump. Diabetes Obes Metab 2020. [crossref]

- Silva J da, Lepore G, Battelino T, Arrieta A, Castañeda J, Grossman B, Shin J, Cohen O Real-World Performance of the MiniMedTM 780G System: First Report of Outcomes from 4120 Users. Diabetes Technol Ther 2022. [crossref]

- Elbarbary NS, Ismail EAR. MiniMed 780G™ advanced hybrid closed-loop system performance in Egyptian patients with type 1 diabetes across different age groups: evidence from real-world users. Diabetology & Metabolic Syndrome (2023)[crossref]

- Alwan H, Wilinska ME, Ruan Y, DaSilva J, Hovorka R. Real-world evidence analysis of a hybrid closed-loop system. J Diabetes Sci Technol 2023. [crossref]

- Ng SM, Katkat N, Day H, Hubbard R, Quinn M, Finnigan L. Real‐world prospective observational single‐centre study: Hybrid closed loop improves HbA1c, time‐in‐range and quality of life for children, young people and their carers. Diabetic Medicine 2022.

- Breton MD, Kovatchev BP. One Year Real-World Use of the Control-IQ Advanced Hybrid Closed-Loop Technology. Diabetes Technol Ther 2021.

- Graham R, Mueller L, Manning M, Habif S, Messer LH, Pinsker J, Aronoff-Spencer E. Real-World use of Control-IQ Technology is associated with a lower rate of severe hypoglycemia and Diabetic Ketoacidosis than historical data: Results of the Control-IQ Observational (CLIO) Prospective Study. Diabetes Technol Ther 2024. [crossref]

- Amadou C, Franc S, Benhamou P-Y, Lablanche S, Huneker E, Charpentier G, Penfornis A. Diabeloop DBLG1 Closed-Loop System enables patients with Type 1 Diabetes to significantly improve their glycemic control in real-life situations without serious adverse events: 6-month follow-up. Diabetes Care 2021. [crossref]

- Brown RE, Vienneau T, Aronson R. Canadian Real‐World Outcomes of Omnipod Initiation in People with Type 1 Diabetes (COPPER study): Evidence from the LMC Diabetes Registry. Diabetic Medicine 2021. [crossref]

- Crabtree TSJ, Griffin TP, Yap YW, Narendran P, Gallen G, Furlong N, et al. Hybrid Closed-Loop Therapy in adults with Type 1 Diabetes and above-target HbA1c: A real-world observational study. Diabetes Care 2023. [crossref]

- Nwokolo M, Hovorka R. The Artificial Pancreas and Type 1 Diabetes. The Journal of Clinical Endocrinology & Metabolism, 2023. [crossref]

- Bionic Pancreas Research Group; Russell SJ, Beck RW, et al. Multicenter, randomized trial of a bionic pancreas in type 1 diabetes. N Engl J Med. 2022.

- Burnside MJ, Lewis DM, Crocket HR, et al. Open-Source automated insulin delivery in type 1 diabetes. N Engl J Med. 2022. [crossref]

- Zeng B, Jia H, Gao L, Yang Q, Yu K, Sun F. Dual-hormone artificial pancreas for glucose control in type 1 diabetes: A meta-analysis. Diabetes Obes Metab. 2022.

- Peacock S, Frizelle I, Hussain S. A systematic review of commercial hybrid closed-loop Automated Insulin Delivery Systems. Diabetes Ther 2023.

- Hettiarachi C, Daskalaki E, Desborough J, Nolan CJ, O’Neal D, Suominen H. Integrating multiple inputs into an artificial pancreas system: narrative literature review. JMIR Diabetes. 2022.

- Tsoukas MA, Majdpour D, Yale JF, et al. A fully artificial pancreas versus a hybrid artificial pancreas for type 1 diabetes: a single- centre, open-label, randomised controlled, crossover, non- inferiority trial. Lancet Digit Health. 2021.