Abstract

Background: The COVID-19 pandemic has disproportionately affected refugee populations, with refugees suffering higher rates of exposure and infection and a higher risk of severe disease and death due to socioeconomic disparities, reduced access to healthcare, and underlying medical conditions. Widespread vaccination is critical to reduce the individual morbidity and mortality as well as the public health burden of COVID-19. However, the uptake of COVID-19 vaccination among refugee populations is unknown.

Methods: We used validated surveys to quantitatively assess COVID-19-related fear and vaccine hesitancy in a population of Syrian refugees living in Turkey.

Results: COVID-19 vaccine hesitancy is critically high among Syrian refugees, with 85% of participants refusing vaccination. However, COVID-19 fear is also high, with over 90% of participants expressing fear of contracting or dying from COVID-19. Misinformation and false beliefs regarding vaccine efficacy and side effects contribute to the discrepancy between high fear of an infectious disease and low rates of acceptance of a life-saving preventive measure.

Conclusion: COVID-19 vaccine hesitancy is alarmingly high in Syrian refugee populations. Targeted interventions to improve vaccine acceptance in refugee populations are urgently needed.

Keywords

COVID-19, Vaccine hesitancy, Refugees, Syria, Turkey

Background

The COVID-19 pandemic has caused over 650 million recorded cases and over six million deaths worldwide as of December 2022 per World Health Organization statistics. Refugees and asylum-seekers have been disproportionately affected by all aspects of the pandemic. Refugees are at higher risk of initial exposure to SARS-CoV-2, are more likely to be hospitalized with COVID-19, and have a higher mortality rate compared to non-refugee populations [1]. A multitude of factors contribute to increased risk of in this population. Refugees are more likely to reside in crowded living conditions, to work low-wage public-facing jobs, to have less access to public health messaging in their native language, and to have lower health literacy compared to non-refugee individuals [2-8]. Once infected, refugees have a higher risk of severe COVID-19 symptoms, of requiring hospitalization due to COVID-19, and of death due to COVID-19. This is likely due to a higher incidence of chronic comorbidities, delays in seeking medical attention, and exclusion from the healthcare system, among other causes. Special attention to the effect of the COVID-19 pandemic on refugees is urgently needed.

Turkey harbors the world’s largest population of refugees and the world’s largest Syrian refugee population, with 3.65 million Syrian refugees and an additional 330,000 refugees from other countries [9]. Turkey has been profoundly affected by the COVID-19 pandemic, with over 12 million infections, nearly 92,000 deaths, massive inflation, and an unemployment rate of up to 40% [10]. Even prior to the pandemic, the refugee population in Turkey placed humanitarian and economic strain on the country. In 2020, the United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees (UNHCR)’s budget for refugees and asylum-seekers in Turkey was 365 million US dollars (USD); however, the sum of all available funds was only 131 million USD, a gap of 234 million USD [11].

Vaccination, combined with non-pharmaceutical methods such as social distancing and use of masks, offers the world’s best chance at curtailing the COVID-19 pandemic. Multiple effective and safe vaccinations to prevent COVID-19 have been developed and widely implemented with infection reduction rates of over 90% and excellent safety profiles. Unfortunately, vaccine hesitancy, defined by the World Health Organization (WHO) as “the reluctance or refusal to vaccinate despite the availability of vaccines,” is common in many populations. Given that refugees are at increased risk of COVID-19 exposure, infection, severe disease, and death, vaccination of this population is critically important, and vaccine hesitancy in this group is life-threatening. However, refugee and migrant populations have dismally low vaccination rates compared to non-refugee populations. Prior to the COVID-19 pandemic, vaccination rates for other preventable infectious diseases, such as measles-mumps-rubella (MMR), polio, and diphtheria-pertussis-tetanus (DPT), had been persistently low for decades in refugee populations compared to non-refugee populations [12]. With regard to the COVID-19 vaccine, as of June 2021, 85% of COVID-19 vaccine doses administered had been given in high- and middle-income countries, but 85% of refugees reside in developing countries [13]. Even within vaccine administration programs in developing countries, refugees are neglected: for example, in Lebanon in April 2021, refugees and migrants comprised 30% of the country’s population, but only 2.9% of vaccinated individuals [14].

Low COVID-19 vaccination rates among refugees are multifactorial. Some contributors are systemic, including lack of healthcare coverage or access to care for refugees, lack of vaccine information in refugees’ language, lack of transportation or financial means to obtain vaccination, and perceived fear of detention when presenting for medical care [15]. However, COVID-19 vaccine hesitancy is prevalent in refugee populations as identified by qualitative interviews [16]. These investigations identified misinformation and false beliefs as major drivers of vaccine hesitancy: for example, that COVID-19 is a hoax, that COVID-19 is a “Western disease,” that the government cannot be trusted, and that the COVID-19 vaccine contains microchips [17]. Facebook, TikTok, Whatsapp, and YouTube were cited as primary sources of COVID-19-related information [17].

Objectives

A rigorous understanding of the motivations, attitudes, and fears regarding vaccination is critically needed in order to decrease vaccine hesitancy and improve vaccination rates in refugee populations. In this study, we present the first quantitative investigation of refugee COVID-19 vaccine hesitancy using a validated questionnaire.

Methods

A cross-sectional survey was conducted in January 2022 among Syrian refugee patients in Turkey. Data were collected from patients aged 18 and older who presented for outpatient care at a public medical facility in Istanbul, Turkey. Patients who had already received any COVID-19 vaccine were excluded. Informed consent was obtained from each participant. This study was approved by the Institutional Review Board of the university hospital.

COVID-19-related fear was assessed via the Fear of COVID-19 Scale (FCV-19S). FCV-19S was developed in 2020 by a multinational group from Hong Kong, Iran, the United Kingdom, and Sweden [18]. FCV-19S assesses multiple aspects of fear related to COVID-19, including vulnerability to infection, fear of dying, and psychological and physical symptoms of anxiety. FCV-19S has robust psychometric properties and provides a reliable quantification of the severity of fear of COVID-19. Response patterns are not affected by respondent age or gender. The scale has since been implemented and validated in numerous other European, Middle Eastern, and Asian countries, including Turkey.

General vaccine hesitancy sentiment was assessed using the World Health Organization (WHO) Strategic Advisory Group of Experts on Immunization (SAGE) definition. Assessment of vaccine hesitancy by the SAGE definition can be done via as few as three questions regarding vaccine behaviors; this definition and question set have been widely employed worldwide [19].

COVID-19 vaccine hesitancy was assessed using a version of the Vaccination Attitudes Examination (VAX) scale. VAX is a measure of anti-vaccination sentiment that was initially developed in 2017 by a cooperative group from the United States and New Zealand [20]. Initially developed to measure general anti-vaccination attitudes, the VAX scale can be adapted to assess attitudes toward specific vaccines. The original VAX scale has high internal consistency and validity, and responses are significantly associated with both past vaccine behavior and future vaccine intentions. The VAX scale has been adapted to create the Attitudes toward COVID-19 Vaccine Scale to assess COVID-19 vaccine hesitancy, and has been implemented in several countries, including the United States, France, and India.

For the present study, assessments were translated from English into Arabic, and participant responses were translated back into English. A pilot with 20 participants was initially performed. The questionnaire and the logistical arrangements were found feasible by the participants.

Statistical analysis: Statistical analyses were performed using SPSS statistical software version 24 (IBM Corporation, Armonk, New York, USA). Results are presented as frequencies and percentages for categorical variables and as the mean and standard deviation for continuous variables.

Results

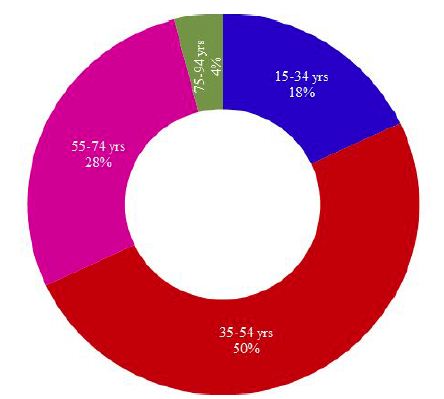

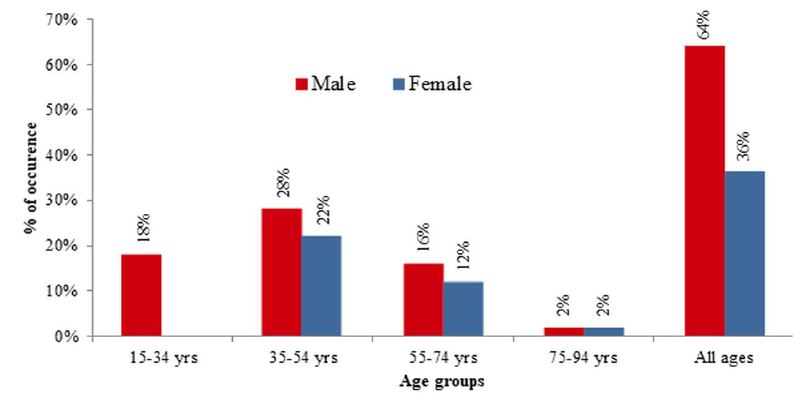

A total of 321 participants were recruited to the study and completed the survey. The median participant age was 43 (range: 18-75). Forty-three percent of participants identified as female. The majority of participants were illiterate (60%), were not working (62%), and lived in large households (household size of five to six, 41%; household size of seven to nine, 42%). Thirty percent of participants reported a personal history of COVID-19 infection. Twenty-seven percent of participants reported a personal history of diabetes mellitus, hypertension, and/or hyperlipidemia. Demographic characteristics of the cohort are displayed in Table 1.

Table 1: Demographic characteristics of study participants

|

Median (range) |

|

| Age | 43 (18-75) |

| N (%) | |

| Gender identity | |

| Female | 139 (43.3) |

| Male | 182 (56.7) |

| Education | |

| Illiterate | 193 (60.1) |

| Primary school graduate | 71 (22.1) |

| Secondary school graduate | 57 (17.8) |

| Work status | |

| Not working | 200 (62.3) |

| Working irregularly | 41 (12.8) |

| Working regularly | 80 (24.9) |

| Size of household | |

| 3-4 | 57 (17.8) |

| 5-6 | 130 (40.5) |

| 7-9 | 134 (41.7) |

| Personal history of COVID-19 infection | |

| Yes | 94 (29.3) |

| No | 227 (70.7) |

| Personal history of chronic disease (DM, HTN, and/or HLD) | |

| Yes | 86 (26.8) |

| No | 235 (73.2) |

Fear of COVID-19 was common among participants, as assessed by FCV-19S. Ninety-three percent of participants reported feeling uncomfortable when thinking about COVID-19, and 75% of participants reported fear of dying of COVID-19. Forty to 65% of participants also reported physical symptoms of anxiety (palpitations or insomnia) related to fear of COVID-19. Results of the FCV-19S assessment are displayed in Table 2.

Table 2: Fear of COVID-19

|

Yes [N (%)] |

No [N (%)] |

|

| I am most afraid of Coronavirus-19. | 300 (93.5) | 21 (6.5) |

| It makes me uncomfortable to think about Coronavirus-19. | 300 (93.5) | 21 (6.5) |

| My hands become clammy when I think about Coronavirus-19. | 180 (56.1) | 141 (43.9) |

| I am afraid of losing my life because of Coronavirus-19. | 239 (74.5) | 82 (25.5) |

| When watching news and stories about Coronavirus-19 on social media, I become nervous or anxious. | 218 (67.9) | 103 (32.1) |

| I cannot sleep because I’m worrying about getting Coronavirus-19. | 127 (39.6) | 194 (60.4) |

| My heart races or palpitates when I think about getting Coronavirus-19. | 207 (64.5) | 114 (35.5) |

General vaccine hesitancy was common among participants. Seventy-one percent of participants reported refusing a vaccine for themselves or their child in the past, and 46% reported postponing a vaccine recommended by a physician. Vaccine hesitancy data are displayed in Table 3.

Table 3: Vaccine hesitancy

|

Yes [N (%)] |

No [N (%)] |

|

| Have you ever refused a vaccine for yourself or a child because you considered it as useless or dangerous? | 229 (71.3) | 92 (28.7) |

| Have you ever postponed a vaccine recommended by a physician? | 147 (45.8) | 174 (54.2) |

| Have you ever had a vaccine for a child or yourself despite doubts about its efficacy? | 0 (0) | 321 (100.0) |

COVID-19 vaccine hesitancy was high among participants. Only 14% of participants stated that they would receive the COVID-19 vaccine. The remaining 86% of participants stated that they would refuse the COVID-19 vaccine. Of those respondents who refused vaccination, reasons for refusal were fear of side effects (78.5%), doubt about effectiveness (19%), and suspicion of short production timeline (2.5%). Attitudes toward COVID-19 Vaccine Scale response data are displayed in Table 4.

Table 4: Intentions regarding COVID-19 vaccination

| If a vaccine against the Coronavirus was available, would you get vaccinated? |

N (%) |

| Yes | 46 (14.3) |

| No | 275 (85.7) |

| If no, why? | |

| Fear of side effects | 216 (78.5) |

| Doubt about effectiveness | 52 (19.0) |

| Suspicion of short production timeline | 7 (2.5) |

Discussion

In this study, we present the first quantitative assessment of COVID-19 vaccine hesitancy and fear of COVID-19 in a refugee population using validated questionnaires. COVID-19 vaccine hesitancy is alarmingly high in this population: 86% of participants stated that they would refuse a COVID-19 vaccine. General vaccine hesitancy is also prevalent in this population, with more than 40% of participants reporting a history of refusing or postponing a recommended vaccine.

The prevalence of vaccine hesitancy in this large cohort of refugee patients is concerning given this population is at extremely high risk in every phase of an infectious pandemic, from initial infection to death. Firstly, migrants and refugees are at higher risk of infection with the Coronavirus compared to non-refugee populations. For example, in Denmark in May 2020, the incidence of COVID-19 in the migrant population was 240 per 100,000, compared to 128 per 100,000 among native Danish individuals [21]. Similarly, in Spain in April 2020, the incidence of COVID-19 in the migrant population was 8.81 per 1,000, compared to only 6.51 per 1,000 for native Spanish individuals [22]. The living conditions of refugees, which commonly involve camp-type settings with crowding and extensive use of shared spaces, likely contribute to the increased incidence in refugee populations: outbreaks have been observed in migrant shelters in many countries. Even in non-camp settings, refugees are more likely to reside in shared or overcrowded housing. For example, in a survey of Organization for Economic Cooperation and Development (OECD) countries, migrants were twice as likely to live in an overcrowded housing setting (17%, versus 8% of native-born individuals) [1]. Occupational risks also contribute to increased risk of contracting COVID-19 among refugee populations: refugees are more likely to be employed in public-facing jobs, such as retail, delivery, hospitality, and transport, thereby increasing the risk of COVID-19 exposure compared to other, non-public-facing jobs [23]. Furthermore, refugees generally have more tenuous financial means compared to non-refugee populations and are more likely to be employed in “no work, no pay” jobs such as those mentioned above, necessitating the continuation of work even in high-risk conditions [4,5,23].

Refugees are also at higher risk of hospitalization and mortality from COVID-19. In Denmark in September 2020, migrants made up 15% of COVID-19-related inpatient admissions, despite comprising only 9% of the population [21]. In Sweden, the relative risk of ICU admission for COVID-19 was five times higher for migrants from Africa and the Middle East than for native Swedish individuals [24]. Similarly, in Norway, the incidence of hospitalization due to COVID-19 was 147 per 100,000 in migrant populations, compared to 37 per 100,000 for native Norwegian individuals [2,25]. Certain ethnic groups are at even higher risk of poor outcomes, and studies specific to Syrian refugees have found dismal COVID-related mortality rates. In Sweden, Syrian migrants had a relative risk of death from COVID-19 of 6.14 compared to native Swedish individuals [26]. Excess mortality in Syrian migrants in Sweden was 220% in 2020, due overwhelmingly to COVID-19 deaths [26].

Thus, given the high risk of initial exposure, severe disease, and death in this population, the magnitude of benefit from vaccination in this population is enormous, and the consequences of vaccine hesitancy are catastrophic. For example, the resurgence of measles in the United States, Norway, and other countries in the early 2000s as a result of increased parental refusal of MMR vaccination was notable for outbreaks heavily concentrated in migrant and refugee populations. In two outbreaks in Minnesota, USA in the 2010s, 72% of cases occurred in members of the Somali community [27,28]. During this time period, MMR vaccination rates among two-year-old Somalis in Minnesota fell to 54%, from over 90% ten years prior [29]. Similarly, in a 2011 measles outbreak in Oslo, Norway, 80% of cases occurred in members of the Somali community, in which MMR vaccine rates were also noted to be low [29,30]. Unfortunately, the present study confirms that vaccine hesitancy continues to be a major barrier to vaccination among refugee communities with regard to COVID-19 vaccination. Interventions to increase vaccine uptake in refugee populations are critically needed.

Vaccine uptake can be improved by addressing each contributing factor to low vaccination rates. Systemic factors must be addressed on the institutional level. For example, although the national COVID-19 vaccine program in Turkey, the setting of the present study, includes all individuals living in the country regardless of immigration, refugee, or asylum-seeking status, public health and vaccine programs in some countries exclude refugees, either explicitly, or indirectly due to requirements for identification or documentation to be presented at the time of vaccination. Removing systemic barriers by making COVID-19 vaccines available to all individuals regardless of legal status, improving outreach in refugees’ native language, increasing vaccine convenience, and guaranteeing protection from detention when seeking healthcare will all increase vaccination rates in individuals who desire to be vaccinated.

However, the present study identified that unvaccinated individuals who desire to be vaccinated (but may be impeded from doing so by systemic factors such as those detailed above) are a small minority among the Syrian refugee population in Turkey; the vast majority of participants are refusing COVID-19 vaccination, with concern for side effects the most commonly cited reason for refusal. Therefore, removing systemic barriers to vaccination is not sufficient to improve vaccination rates. Education on vaccine effects must be provided and misinformation and false beliefs must be addressed to improve vaccine hesitancy.

Although the present study is the first to quantitatively assess COVID-19 vaccine hesitancy in refugee populations using validated questionnaires, vaccine hesitancy in general has been well-studied. The most effective strategies for reducing vaccine hesitancy and improving vaccination rates overwhelmingly involve accessible, understandable health education from trusted sources. These strategies have been well-described by previous groups [31,32]; we briefly summarize the most common and salient points here. First, and perhaps most importantly, public health messaging must be available in refugees’ native language. In Turkey, a robust COVID-19 public health program is available via internet and a COVID-19 hotline is available via telephone, but these sources are only available in Turkish and English; 80% of Syrian refugees speak only rudimentary Turkish. An Arabic translation of the website or an Arabic language option for the telephone hotline would make this information more accessible for Syrian refugees. This model has been extremely successful in Sweden, where healthcare workers use telemedicine platforms nicknamed “Corona lines” to distribute COVID-19 educational information, triage respiratory symptoms, and instruct patients on appropriate quarantine and hygiene in Arabic, Somali, Tigrinya/Amharic, and Persian/Dari as well as the Swedish national languages. Second, vaccine development, testing, and approval information should be transparent and accessible to the public. As prior qualitative interviews cited above noted social media as the main source of COVID-19-related information for refugees, this information should be publicized via not only traditional media, but verified sources on social media as well. For example, national health ministries can use their official Facebook and other social media feeds to publicize vaccine information; this information should be in refugees’ native language, as discussed below. Specific provocative or culturally relevant false beliefs, such as concern that the vaccine contains pork products or causes infertility, should be targeted and addressed emphatically. The participants in the present study overwhelmingly indicated fear of side effects as the reason for vaccine refusal; public health information should emphasize the favorable side effect profile of COVID-19 vaccines. Third, personal storytelling from persons with whom refugee populations identify are effective means of appealing to individuals’ empathy and emotion. For example, for a target population of Syrian refugees, a public health announcement featuring a multigenerational Syrian family who accepted the vaccine can be filmed and widely publicized as described above. Fourth, community leaders, particularly religious leaders, such as imams at Syrian-majority Arabic-speaking mosques, should be partnered with for the dissemination of vaccine information. Fifth, refugee populations should be actively included in the process of public health education and information dissemination; for example, local public health committees should include at least one refugee member who participates in vaccination campaigns.

We found that fear of COVID-19 is also common in this population, with over 90% of participants reporting COVID-19-related fear. Notably, 75% of participants stated that they fear dying of COVID-19. The coexistence of high COVID-19 fear with high vaccine hesitancy seems contradictory. This contradiction emphasizes the role of misinformation, portraying the preventive measure as more harmful than the disease itself, in promoting vaccine hesitancy in this population. However, COVID-19 fear may become a motivation for participants to agree to vaccination if misinformation is replaced with accurate information about the efficacy and safety of COVID-19 vaccines.

The limitations of our study include its design as a cross-sectional survey, which represents the attitudes of the survey participants at one time point, and does not assess changes in attitudes over time. The demographic and clinical variables assessed, such as comorbidities and history of COVID-19 infection, were self-reported by participants, and were not verified by the investigators. The study was restricted to Syrian refugees in an urban metropolis. It may not be generalizable to other ethnic refugee populations, or to refugees in rural areas.

Conclusion

Refugee populations are at high risk of COVID-19 exposure, infection, severe morbidity, and mortality. Fear of COVID-19 infection is high in this population, with over 90% of participants reporting COVID-19-related fear. However, despite high levels of fear the disease, COVID-19 vaccine hesitancy is contradictorily and critically high among Syrian refugees in Turkey, with over 80% of individuals refusing vaccination. Fear of side effects is the most common reason for refusal of vaccination. Targeted public health outreach interventions are critical to improve vaccination rates in this vulnerable population.

Funding

This research received no specific grant from any funding agency in the public, commercial, or not-for-profit sectors.

References

- OECD (2020) What is the impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on immigrants and their children? Paris: OECD.

- Indseth T, Grosland M, Arnesen T, Skyrud K, Klovstad H, et al. (2021) COVID-19 among immigrants in Norway, notified infections, related hospitalizations and associated mortality: A register-based study. Scand J Public Health 49: 48-56. [crossref]

- Intervention GMoHNPHODoESa. Epidemiological surveillance in points of care for refugees/migrants weekly report week 14/2020. Greek Ministry of Health National Public Health Organization Department of Epidemiological Surveillance and Intervention; 2020.

- Giordano C (2020) Freedom or money? The dilemma of migrant live-in elderly carers in times of COVID-19. Gend Work Organ.

- Wang FTC, Qin Weidi (2020) The impact of epidemic infectious diseases on the wellbeing of migrant workers: A systematic review. International Journal of Wellbeing 10.

- Chiarenza A, Dauvrin M, Chiesa V, Baatout S, Verrept H (2019) Supporting access to healthcare for refugees and migrants in European countries under particular migratory pressure. BMC Health Serv Res 19: 513.

- Kizilkaya MC, Kilic SS, Bozkurt MA, Sibic O, Ohri N, et al. (2022) Breast cancer awareness among Afghan refugee women in Turkey. EClinicalMedicine 49: 101459. [crossref]

- Sayan M, Eren MF, Kilic SS, Kotek A, Kaplan SO, et al. (2022) Utilization of radiation therapy and predictors of noncompliance among Syrian refugees in Turkey. BMC Cancer 22: 532. [crossref]

- United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees Fact Sheet: Turkey. 2021.

- G S. The impact of COVID-19 on poverty in Turkey. The Borgen Project; 2021 13 July 2021.

- United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees [Internet]. 2021.

- Roberton T, Weiss W, Jordan Health Access Study T, Lebanon Health Access Study T, Doocy S (2017) Challenges in Estimating Vaccine Coverage in Refugee and Displaced Populations: Results From Household Surveys in Jordan and Lebanon. Vaccines (Basel) 5. [crossref]

- ER (2021) On COVID vaccinations for refugees, will the world live up to its promises? The New Humanitarian.

- Waddell B (2021) States That Have Welcomed the Most Refugees from Afghanistan. US News and World Report.

- Observatory Report: Left Behind: The State of Universal Healthcare Coverage in Europe. Brussels: Médecins du Monde; 2019.

- Salibi N, Abdulrahim S, El Haddad M, Bassil S, El Khoury Z, et al. (2021) COVID-19 vaccine acceptance in older Syrian refugees: Preliminary findings from an ongoing study. Prev Med Rep 24: 101606. [crossref]

- Crawshaw AF, Deal A, Rustage K, Forster AS, Campos-Matos I, et al. (2021) What must be done to tackle vaccine hesitancy and barriers to COVID-19 vaccination in migrants? J Travel Med 28. [crossref]

- Ahorsu DK, Lin CY, Imani V, Saffari M, Griffiths MD, et al. (2020) The Fear of COVID-19 Scale: Development and Initial Validation. Int J Ment Health Addict 1-9. [crossref]

- Rey D, Fressard L, Cortaredona S, Bocquier A, Gautier A, et al. (2018) Vaccine hesitancy in the French population in 2016, and its association with vaccine uptake and perceived vaccine risk-benefit balance. Euro Surveill 23. [crossref]

- Martin LR, Petrie KJ (2017) Understanding the Dimensions of Anti-Vaccination Attitudes: the Vaccination Attitudes Examination (VAX) Scale. Ann Behav Med 51: 652-660. [crossref]

- Institut SS (2020) COVID-19 I Danmark. Epidemiologisk trend og fokus: Herkomst (etnicitet). Copenhagen. Statens Serum Institut.

- Guijarro C, Perez-Fernandez E, Gonzalez-Pineiro B, Melendez V, Goyanes MJ, et al. (2021) Differential risk for COVID-19 in the first wave of the disease among Spaniards and migrants from different areas of the world living in Spain. Rev Clin Esp (Barc) 221: 264-273. [crossref]

- Reducing COVID-19 transmission and strengthening vaccine uptake among migrant populations in the EU/EEA. Stockholm; 2021 3 June 2021.

- Utrikesfödda och covid-19: Konstaterade fall, IVAvård och avlidna bland utrikesfödda i Sverige 13 mars 2020 – 15 februari 2021. Stockholm: Swedish Public Health Agency (Folkhalsomyndigheten); 2021.

- Covid-19 blant personer født utenfor Norge, justert for yrke, trangboddhet, medisinsk risikogruppe, utdanning og inntekt2021. Folkehelseinstituttet; 2021.

- Hansson E, Albin M, Rasmussen M, Jakobsson K (2020) [Large differences in excess mortality in March-May 2020 by country of birth in Sweden]. Lakartidningen 117. [crossref]

- Gahr P, DeVries AS, Wallace G, Miller C, Kenyon C, et al. (2014) An outbreak of measles in an under vaccinated community. Pediatrics 134: e220-228. [crossref]

- Leslie TF, Delamater PL, Yang YT (2018) It could have been much worse: The Minnesota measles outbreak of 2017. Vaccine 36: 1808-1810. [crossref]

- Tankwanchi AS, Jaca A, Larson HJ, Wiysonge CS, Vermund SH (2020) Taking stock of vaccine hesitancy among migrants: a scoping review protocol. BMJ Open 10: e035225.

- Vainio K, Ronning K, Steen TW, Arnesen TM, Anestad G, et al. (2011) Ongoing outbreak of measles in Oslo, Norway, January-February 2011. Euro Surveill 16. [crossref]

- Thomas CM, Osterholm MT, Stauffer WM (2021) Critical Considerations for COVID-19 Vaccination of Refugees, Immigrants, and Migrants. Am J Trop Med Hyg 104: 433-435. [crossref]

- Aborode AT, Fajemisin EA, Ekwebelem OC, Tsagkaris C, Taiwo EA, et al. (2021) Vaccine hesitancy in Africa: causes and strategies to the rescue. Ther Adv Vaccines Immunother 9: 25151355211047514. [crossref]