Abstract

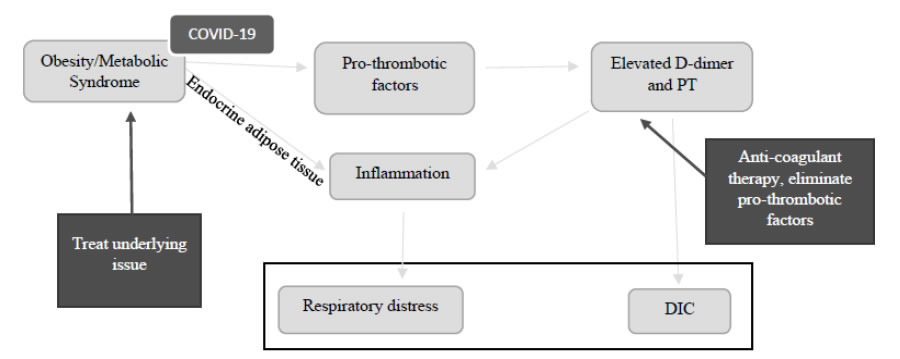

Purpose: External pelvic chemo-radiotherapy and brachytherapy were studied in a consecutive series of advanced cervical carcinomas. Conventional brachytherapy and image-guided adaptive brachytherapy were compared.

Material and Methods: From a single regional cancer center 272 consecutivepatients with advanced cervical cancer were recruited. One hundred thirty-four patients were treated with external beam radiotherapy and conventionalconformal brachytherapy (BT) and 138 patients with image-guided adaptive brachytherapy (IGABT). A comprehensive dosimetric study was performed in the IGABT-group.Predictive and prognostic factors were defined. Toxicity of the organs at risk were evaluated by the CTCAE-grading system.

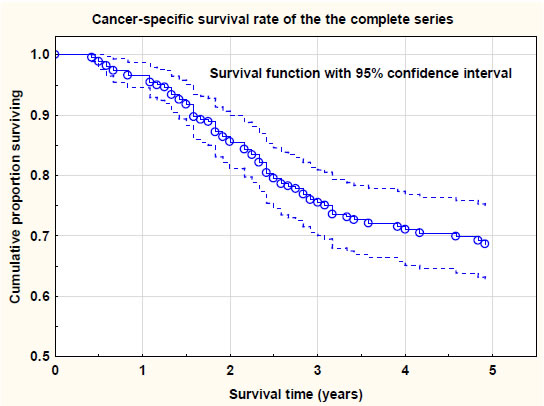

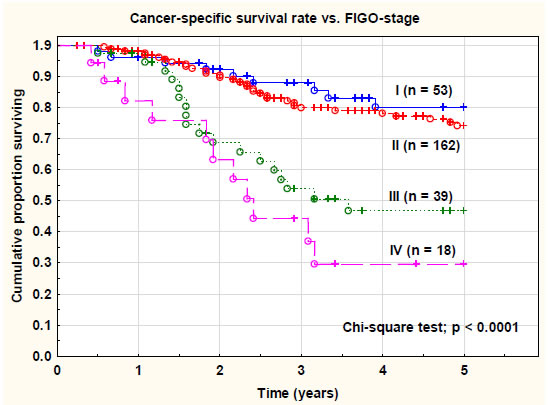

Results: The mean follow-up was 59 months. Tumor size was in mean 43 mm. The mean external dose was 52 Gy and the total dose to the clinical target volume was 78 Gy. Sixty-five percent of the patients received weekly cisplatin. The mean overall treatment time was 44 days. The median number of brachytherapy fractions was four and in 86 patients in the IGABT-group interstitial needles were applied. The primary local control was 98%. The overall pelvic control was 86%. The overall recurrence rate was 29%. The overall 5-year survival rate was 65% and cancer-specific survival rate 69%. Prognostic factors were O-stage, pelvic and distant control of the disease. Late serious toxicity of the bladder and intestine were rare with only 3% in the IGABT-group.

Conclusion: The local and pelvic controls were excellent. The IGABT was an important part of the treatment schedule with regard to large tumors and adenocarcinomas. Late toxicity was significantly lower after treatment with IGABT compared with BT.

Keywords

Cervical cancer; Conventional brachytherapy (BT); Image-guided adaptive brachytherapy (IGABT); Chemo-radiotherapy; Local tumor control; Survival; Toxicity

Introduction

Cervical cancer is the fourth most frequently diagnosed cancer and the fourth leading cause of death among women worldwide [1]. Human papillomavirus (HPV) infection is an important and common risk factor for developing cervical carcinomas [2]. Other factors, e.g. immunosuppression (HIV), smoking and a higher number of full-term pregnancies also contribute to increased risk [1].

The histological subtypes are divided into three types: squamous cell carcinomas in 70-80%, adenocarcinomas in 20-25%, and other epithelial cancers the remaining cases [2].

Cervical cancer incidence has decreased during the last decades, mainly due to screening programs. In the Nordic countries, among them Sweden, screening may have prevented 40-50% of the expected cases [3]. Screening programs also detect premalignant lesions and global variation in cervical cancer in part reflects the variation for women to take part in these programs [2]. New HPV vaccines may further reduce cervical cancer incidence [2].

FIGO stage is one of the most important prognostic factors [2].Surgery is the main treatment in early stages (FGIO I-IIA). In FIGO stage IB2-IVA, considered as locally advanced disease, the standard of treatment is a combination of radiochemotherapy and brachytherapy. Cisplatin, given once-week in the dose 40 mg/m2, is the most common chemotherapy used [2]. Addition of concomitant chemotherapy has increased the survival rate [4, 5, 6].

Brachytherapy has improved management of cervical carcinomas, allowing a higher dose to the tumor without increasingtoxicity of the risk organs (bladder,recto-sigmoid and vagina).Intracavitary brachytherapy in combination with external beam therapy and concurrent chemotherapy was shown to have good results regarding local control [7]. A previous study showed an increase in overall survival rate of this combination compared to external beam therapy with an external boost [8].

Early radiation reactions were less prevalent among those treated with brachytherapy compared to those given an external boost, but late toxicity was similar [8].

While comparing image guided adaptive brachytherapy (IGABT) given with only intracavitary applicator (ring or ovoid applicators) with a combination of intracavitary and interstitial applicators, side effects regarding bladder and bowel were similar, but late vaginal side effects were slightly more prevalent among those who had received interstitial applications [9].

Among predictive factors for radiation side effects there seemed to be anassociation between the width and lateral extent of the external pelvic radiotherapy fields and early side effects, especially early symptoms from the bladder and bowel. For late side effects the same predictive factors regarding external radiotherapy was found, but also, it was shown that prior abdominal surgery increased the risk for late side effects. However, concomitant cisplatin did not increase the risk of side effects [10].

The aim of the present study was to compare an older conformal brachytherapy (BT) technique with a newer image-guided adaptive brachytherapy (IGABT) based on MRI image planning with regard to treatment outcome (local control and cancer-specific survival rate) and side effects of the organs at risk.

Material and methods

Patients and tumors

Two consecutive series of 134 (BT-group) and 138 (IGABT-group) cervical carcinomas treated with combined external (± chemotherapy) and intracavitary radiotherapy during the period January 1, 1993 and December 31, 2016 were included in this prospective series (Table 1). Patients treated with surgery or only external radiotherapy were not included in this study. In an older series (1993-2006) conventional 2-D conformal brachytherapy (BT) was used and in a later series (2010-2016) 3-D image-guided adaptive brachytherapy (IGABT). In the IGABT-group all clinical data were available for analysis together with extensive dosimetric data from the brachytherapy treatment [11]. MRI was used for dose planning with the applicators in situ. In 86 patients interstitial needles were used as part of the image-guided adaptive brachytherapy (IGABT). In 178 patients (65.4%) concurrent chemotherapy (weekly cisplatin 40 mg/m2) was administered during radiation therapy. Twenty-one patients (7.7%) received neoadjuvant chemotherapy before irradiation.

Table 1. Patient and tumor characteristics of the complete series (n = 272).

|

Factor |

No. of patients n (%) |

|

Mean age (years) |

59.4 (range 23-90) |

|

Prior diseases (cardiovascular, diabetes, GI, gyn) |

131 (48.2) |

|

Prior abdominal surgery (GI, urol, gyn) |

123 (45.2) |

|

FIGO stage |

|

|

IB |

53 (19.5) |

|

IIA |

50 (18.4) |

|

IIB |

112 (41.2) |

|

IIIA |

6 (2.2) |

|

IIIB |

33 (12.1) |

|

IVA |

11 (4.0) |

|

IVB |

7 (2.6) |

|

Histology |

|

|

Squamous cell carcinoma |

223 (82.0) |

|

Adenocarcinoma |

40 (14.7) |

|

Adenosquamous cell carcinoma |

6 (2.2) |

|

Other |

3 (1.1) |

|

Grade |

|

|

Well differentiated (grade 1) |

22 (8.1) |

|

Moderately well differentiated (grade 2) |

104 (38.2) |

|

Poorly differentiated (grade 3) |

132 (48.5) |

|

Not graded |

14 (5.1) |

|

Tumor size |

|

|

Maximum width at diagnosis (mm) |

42.5 (range 15-80) |

|

Nodal status (IGABT-group) |

|

|

N+ |

37 (26.8) |

|

Level 1 (internal, external iliac, obturator) |

22 (15.9) |

|

Level 2 (+ common iliac, aortic bifurcation) |

8 (5.8) |

|

Level 3 (+ para-aortic) |

7 (5.1) |

|

N- |

101 (73.2) |

|

Concomitant chemotherapy |

|

|

Yes |

178 (65.4) |

|

No |

94 (34.6) |

The mean follow-up time for patients alive (n = 154) was 70.8months (range 3–229 months). In the compete series the mean follow-up time was 55.5 months (range 3-229 months).Seventy-three patients were dead of cervical cancer(26.8%) and 45 patients dead due to other diseases(16.5%) at the time of last follow-up. The schedule for follow-up was the following: 1 month after the end of radiotherapy, every 3 month the first year, every 4 months the second and third year, every 6 months the fourth year and then annually until five or for some patients until ten years.

FIGO stage distribution was stage I 53/272 (19.5%), stage II 162/272 (59.6%), stage III 39/272 (14.3%), and stage IV 18/272 (6.6%). The largest mean size of the tumors was 42.5 mm (range 15-90 mm) measured on CT or MRI image.Type of histology was squamous cell carcinoma in 223/272 (82.0%) cases, adenocarcinomas in 40/272 (14.7%) cases, adenosquamous cell carcinomas in 6/272 (2.2%) cases, and other types in 3/272 (1.1%) cases.

Nodal stage was assessed by imaging (CT or MRI) in the IGABT-group. Laparoscopic nodal staging was not used. Pathologicallymph nodes were defined as lymph nodes > 1 cm in size, loss of oval shape on imaging, or positive on PET/CT imaging.Thirty-seven patients (26.8%) had positive lymph nodes in this subgroup. Positive lymph nodes were classified into three levels, lower (22/37, 59.5%) or upper (8/37, 21.6%) pelvic and para-aortic (7/37, 18.9%) sites. Data on lymph node status was not available in the BT-group.

The mean age of the patients was 59.4 (range 23-90) years. A prior history of intercurrent diseases (cardiovascular, diabetes, gastrointestinal or other types) was recorded in 131 patients (48.2%), and prior abdominal (gastrointestinal, urological or gynecological) surgery in 123 patients (45.2%).

The study was approved by the ethics committee (Dnr 2018/482) of Uppsala-Örebro region.

External beam radiotherapy (EBRT)

The radiotherapy treatment consisted of external beam pelvic radiotherapy (EBRT) and conventional brachytherapy (BT) or image-guided adaptive brachytherapy (IGABT). A conventional (standard 3-D conformal) 4-field box-technique was used in 240 cases (88.2%), intensity modulated radiotherapy(IMRT)in 21 cases (7.7%), and volumetric modulated arc therapy (VMAT)in 11 cases (4.0%). The mean total external dose was 52.2 (range 45-68.4) Gy. The mean dose per fraction was 1.82 (range 1.8-2.3) Gy. The mean overall treatment time (OTT) was 44.1 (range 30-93) days.

Brachytherapy (BT) – the old series

A high-dose rate brachytherapy technique (Ir-192) was used (Micro-Selectron HDR; Elekta Instruments AB, Sweden) in the old series. A ring applicator set was used with 26 mm (n = 32) or 30 mm (n = 102) diameter of the ring, 20-60 mm intrauterine tandem with 60◦ angel. Absorbed doses and volumes were defined according to ICRU 38 (31-33). The reference dose (6.0 Gy per fraction) was specified as a minimum dose to the surface of the target isodose volume. The mean total brachytherapy dose was 26.3 Gy (SD 5.5 Gy). The central pelvic mass including cervix and the tumor (visualized by CT-scan) was used to define the gross tumor volume (GTV). The clinical target volume (CTVB) was equal with the gross tumor volume (GTVd) at start of radiotherapy. In case of more advanced tumors a new tumor evaluation (examination under anesthesia and pelvic CT) was done after 45-50 Gy of external irradiation for dose planning purposes. The shrunken gross tumor volume (GTVB) was then set equal to the clinical target volume (CTVB) of brachytherapy. Point doses in point A and B, at the bladder reference point (BRP), and at the rectal reference points were calculated. A bladder catheter with 7 cc contrast medium in the balloon was used to define the bladder reference point. The brachytherapy sessions were given once-a-week in parallel with the external beam therapy. In 91 patients (67.9%) five fractions (30 Gy; EQD2 = 40 Gy) were given and in 43 patients (32.1%) three fractions (18 Gy; EQD2 = 24 Gy) were administered. On the brachytherapy day both an external and an intracavitary fraction was given with a minimum of 6 hours apart. In case of smaller tumors in stage IB, IIA and early IIB five fractions of 6 Gy each were given (total EQD2 = 90 Gy for α/β = 10), and in cases with more advanced tumors (late IIB-III-IV) three fractions of 6 Gy were given in parallel with 60 Gy of external beam therapy (total EQD2 = 84 Gy for α/β = 10). A CT-based 3-D dose planning system was used for external beam therapy (TMS, Elekta Instruments AB, Sweden) and for brachytherapy planning (NPS and PLATO, Elekta Instruments AB, Sweden). MRI of the pelvis was not used for planning purposes in this series.

Brachytherapy (IGABT) – the new series

The median number of fractions was 4.0 (range 1-5). The median dose (EQD2, α/β = 10) per fraction was 8.0 (range 8.0-9.9) Gy. A ring applicator set was used in all cases. Two different ring diameters were used: 26 mm in 45 cases (33.8%) and 30 mm in 88 cases (66.2%). The length of the intrauterine tube varied between 20 and 60 mm, and the angle between the tube and the shaft of the applicator was 60°. The high-risk clinical target volume (HRCTV) was significantly larger in fractions 1-2 (55-57 cm3) compared with fractions 3-4 (48-49 cm3) (dependent t-test; p = 0.0014). In 86/138 patients (62.3%) interstitial needles were used. The number of needles varied between two and nine and the median number was six. The intracavitary / interstitial HDR brachytherapy was performed as follows: At the time of implantation an Interstitial Ring Applicator (Elekta, Stockholm, Sweden) was inserted with the ring positioned in the vaginal vault and the tube located intra-uterine. Interstitial needles were added when deemed necessary in order to cover the target volume with adequate dose. After implantation, the application was fixed by packing of the vagina. A Foley catheter was placed in the bladder and pulled towards the bladder base and fixed. The Foley catheter in the bladder also acted as a stabilization of the geometry. The patient was then transported to the MRI/CT for imaging. In the image study, High Risk Clinical Target Volume (HRCTV) was defined according to European recommendations from the GEC-ESTRO GYN working group [12]. Organs at risk (OAR), such as bladder, rectum and sigmoid were also defined. In the same image set the applicators were reconstructed and an optimized dose distribution based on the dose constraints (Table 2) for the HRCTV and OAR were created using the dose planning system OncentraBrachy (Elekta, Stockholm, Sweden). This procedure was repeated for all (four) fractions in two consecutive days, separated by two weeks. One implant was performed per fraction. The first and third fractions were based on an MRI-study, and fractions two and four were based on a CT-study. The CT-study was co-registered with the MRI-study to visualize the MRI-target in the CT-study, as was analyzed by Nesvacil et al. [13]. Before imaging and dose delivery, the bladder was emptied and refilled to a fixed liquid volume of 50 cm3and a catheter was inserted into rectum to prevent any gas filling.

Table 2. Significant background factors. BT = brachytherapy and IGABT = image-guided adaptive brachytherapy.

|

Factor |

No. of patients n (%) |

|

|

BT-group IGABT-group p value |

|

n = 134 n = 138 |

|

|

|

|

|

Hemoglobin level |

128.0 127.1 0.607** |

|

|

|

|

Prior abdominal surgery |

60 (44.8) 63 (45.7) 0.885* |

|

FIGO stage |

0.130* |

|

I-II |

111 (82.8) 104 (75.4) |

|

III-IV |

23 (17.2) 34 (24.6) |

|

Histology |

0.379* |

|

Squamous cell carcinoma |

110 (82.1) 113 (81.9) |

|

Adenocarcinoma |

21 (15.7) 19 (13.8) |

|

Adenosquamous cell carcinoma |

3 (2.2) 3 (2.2) |

|

Other |

0 (0.0) 3 (2.2) |

|

Tumor size |

|

|

Maximum width at diagnosis (mm) |

44.1 (mean) 41.0 (mean) 0.052** |

|

Gross tumor volume (GTVd) (cm3) |

35.4 (mean) 33.7 (mean) 0.650** |

|

Pearson chi-square test * and t-test ** |

Toxicity evaluation

Late toxicity was evaluated at or after 3 months from completion of radiotherapy using the Common Toxicity Criteria v. 3.0 (CTCAE) [14].

Statistics

In the statistical analyses the Pearson chi-square test, the t-test (independent and dependent groups), binary logistic regression analysis (univariate and multivariate), Kaplan-Meier technique for survival analysis and the log-rank test,Cox F-test, or Gehan´s Wilcoxon tests (small numbers) for test of differences.Cox proportional hazard regression analysis (univariate and multivariate) was usedfor analysis of prognostic factors. A p value < 0.05 was regarded as statistically significant. The Statistica 64 (version 13.0.159.0, 2015) software package (Dell Statistica, Dell Inc.,USA) and IBM SPSS Statistics Version 25.0 (IBM Corp., Armonk, NY, USA) were used in the statistical analyses.

Results

Overall treatment time (OTT)

The mean overall treatment time of the complete series was 44.1 days (range 30-93 days). In 44 patients (16.5%) the OTT > 50 days. The OTT was not a significant predictive (local control, pelvic control, tumor recurrences) or prognostic (cancer-specific survival rate) factor in this study.In the BT-series OTT was significantly (t-test; p < 0.0001) shorter (40.2 days) than in the IGABT-group (47.9 days).

Concomitant chemotherapy

In 178 patients (65.4%) concomitant chemotherapy was given in the complete series. In the BT-group chemotherapy was given in 35.8% and in the IGABT-group in 94.2% (Pearson chi-square; p < 0.0001). In 106patients (39.0%) ≥ 5 cycles were administered. Two groups (≤ 4 cycles and ≥ 5 cycles) were compared with regard to cancer-specific survival rate and there was no significant (log-rank test; p = 0.705) difference between the survival curves. There was no significant association between the number of chemotherapy cycles administered and the total recurrence rate (p = 0.483) or the rate of distant recurrences (p = 0.349). This was true in the complete series, but also in a high-risk subgroup (FIGO-stage III-IV). Late toxicity (bladderand intestinal) was not increased with the number of chemotherapy cycles given. Neoadjuvant chemotherapy was given in 21 patients in the IGABT-group and it was associated with a significantly worse survival rate.

Overall tumor control after primary therapy

In 244/272 (89.7%) patients there were no evidence of disease (complete remission) after completed radiochemotherapy. In the BT-group complete remission was achieved in 124/134 (92.5%) and in the IGABT-group in 120/138 (87.0%) of the patients (Pearson chi-square test; p = 0.130). In the group with FIGO-stage I-III tumors the overall control rate was 232/254 (91.3%).Seventeen patients had loco-regional persistent disease and 11patients’distant disease. (Tables 3 and 4)

Table 3. Dose constraints to HRCTV and organs at risk (OAR) in the IGABT-group.

|

D90 HRCTV EQD210 |

> 85 Gy |

|

Bladder D2cm3 EQD23 |

< 90 Gy |

|

Rectum D2cm3 EQD23 |

< 75 Gy |

|

Sigmoid D2cm3 EQD23 |

< 75 Gy |

Table 4. Disease outcome and morbidity in the complete series (n = 272).

|

Local control after primary treatment |

Percent |

|

Overall |

267/272 (98.2%) |

|

GTVd ≤ 30 cm3 |

142/144 (98.6%) |

|

GTVd> 30 cm3 |

119/122 (97.5%) |

|

Stage IB-IIA |

102/103 (99.0%) |

|

Stage IIB |

111/112 (99.1%) |

|

Stage III |

37/39 (94.9%) |

|

Stage IVA |

11/11 (100.0%) |

|

Local control (at last follow-up) |

|

|

Overall |

258/272 (94.9%) |

|

|

|

|

Pelvic control (at last follow-up) |

|

|

Overall |

234/272 (86.0%) |

|

|

|

|

Systemic control (excluding para-aortic failures) |

|

|

Overall (after primary therapy) |

254/272 (93.4%) |

|

Overall (at last follow-up) |

197/272 (72.4%) |

|

|

|

|

Cancer-specific survival rate (5-year) |

|

|

Overall |

68.5% [95% CI: 62.4-74.6] |

|

Stage I+II |

75.7% [95% CI: 69.2-82.2%] |

|

Stage III+IVA |

45.9% [95% CI: 30.0-61.2%] |

|

|

|

|

Overall survival rate (5-year) |

|

|

Overall |

58.0% [95% CI: 51.5-64.5%] |

|

Stage I+II |

64.3% [95% CI: 57.2-71.4%] |

|

Stage III+IVA |

41.6% [95% CI: 27.1-56.1%] |

|

|

|

|

Morbidity |

|

|

Bladder CTCAE ≥ G1 |

53/272 (19.5%) |

|

Bladder CTCAE ≥ G2 |

14/272 (5.1%) |

|

Bladder CTCAE ≥ G3 |

6/272 (2.2%) |

|

Rectum-sigmoid CTCAE ≥ G1 |

127/272 (46.7%) |

|

Rectum-sigmoid CTCAE ≥ G2 |

53/272 (19.5%) |

|

Rectum-sigmoid CTCAE ≥ G3 |

19/272 (7.0%) |

|

Vaginal CTCAE ≥ G2 (IGABT-group) |

30/138 (21.7%) |

|

Vaginal CTCAE ≥ G3 (IGABT-group) |

0/138 (0.0%) |

|

Bone CTCAE ≥ G1 (IGABT-group) |

12/138 (8.7%) |

|

Bone CTCAE ≥ G2 (IGABT-group) |

3/138 (2.2%) |

Local control

The local control rate at the end of therapy was 98.2% (267/272). Five patients had persistent local disease. During the period of follow-up nine(3.3%) pure local recurrences occurred resulting in 258/272 (94.9%) overall local control.The local control rate in the BT-group was 95.5% and in the IGABT-groupit was 94.2%. During the same period16(5.9%) regional recurrences occurred resulting in a crude loco-regional control rate of 88.6% (241/272). Patients with loco-regionalrecurrences had synchronous distant recurrences in 5 out of 25recurrences (20.0%). The local control rate at the end of follow-up was 96.2% in stage I, 96.9% in stage II, 89.7% in stage III, and 83.3% in stage IV. Squamous cell carcinomas were locally controlled in 96.0% and adenocarcinomas and adenosquamous carcinomas in 89.8% (Pearson chi-square; p = 0.077). Local control rate was similar in grade 1-2 and grade 3 tumors. Concurrent chemotherapy had no statistically significant (Pearson chi-square test; p = 0.926) impact on local control rate.Overall treatment time (OTT) was not significantly associated with local control rate. FIGO-stage and lymph node status were significantly (p = 0.035, p = 0.001) associated with overall local control rate. Total brachytherapy dose and total external and brachytherapy dose had no significant impact on local tumor control after primary therapy.

Addition of interstitial needles (n = 93, 34.2%) had no significant effect on local control rate after end of radiotherapy or on crude local control rate (p = 0.649). The local control rate was 94.4% without needles and 95.7% with needles.

Needles were not used in the BT-group,but in 62.3% in the IGABT-group. In the latter group addition of needles significantly (t-test; p = 0.025) increased the mean HRCTV-volume from 48.1 cm3 to 58.5 cm3. The HRCTV D90 dose from all brachytherapy treatments increased in mean from 31.4 Gy to 40.3 Gy (t-test; p < 0.0001), and the total dose to the HRCTV volume from 82.5 Gy to 91.2 Gy (t-test; p < 0.0001). The bladder 2.0 cm3 dose (α/β = 3) increased from 6.3 Gy to 7.5 Gy (t-test; p = 0.006), the rectal 2.0 cm3 dose from 3.7 Gy to 4.3 Gy (t-test; p = 0.070), and the sigmoid 2.0 cm3 from 3.7 Gy to 5.4 Gy (t-test; p < 0.0001).

Pelvic control

The crude pelvic control at the end of the follow-up was 234/272, 86.0% in the complete series. In the BT-group the control rate was 82.8% and in the IGABT-group it was 89.1%. Thus, a trendto improved pelvic control, but not statistically significant (Pearson chi-square test; p = 0.134).

Systemic control

After completed primary therapy, 18 cases had distant residual disease and five cases local or loco-regional disease. Therefore, the primary systemic (distant) tumor control was 254/272 (93.4%). During the time of follow-up further 57 distant recurrences (21.0%) were recorded resulting in 197/272 (72.4%) overall distant tumor control. Distant metastases were significantly (Pearson chi-square; p = 0.004) associated with tumor stage:22.6% in stage I, 15.4% in stage II, 28.2% in stage III and 50.0% in stage IV. Among squamous cell carcinomas 19.7% distant recurrences were recorded and among adenocarcinomas and adenosquamous carcinomas 26.5% distant recurrences (Pearson chi-square; p = 0.290). Tumor grade was not significantly associated with distant recurrences. The frequency of distant recurrences was similar (21.7% vs. 20.2%) in the two brachytherapy groups.

Recurrences

The overall recurrence rate of the complete series was 78/272 (28.7%). In the two BT-groups the corresponding rates were 32.1% and 25.4%, respectively (not significant). Local recurrence was 9/272 (3.3%), regional recurrences 17/272 (6.3%), and distant recurrences 57/272 (21.0%). In 16 patients (5.9%) multiple sites of recurrences were recorded. The mean time from diagnosis to recurrence was 17.7 months (range 3-104 months). FIGO-stage and hemoglobin value at start of therapy were significant and independent predictive factors. The total brachytherapy and external doses were not significantly associated with the overall or distant recurrence rate.

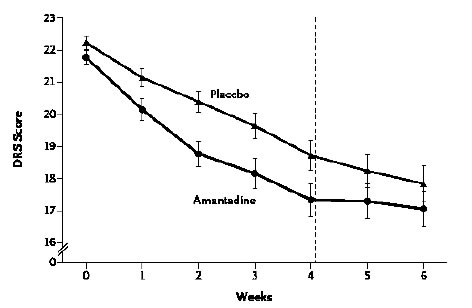

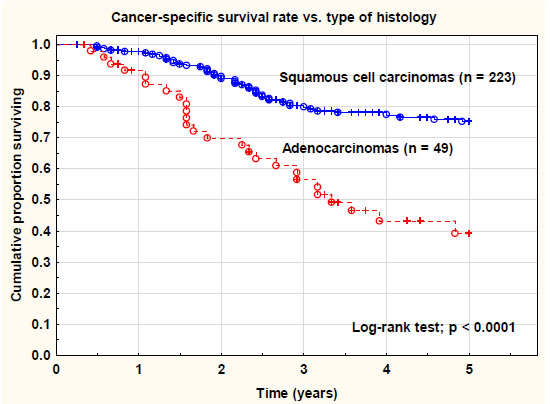

Survival

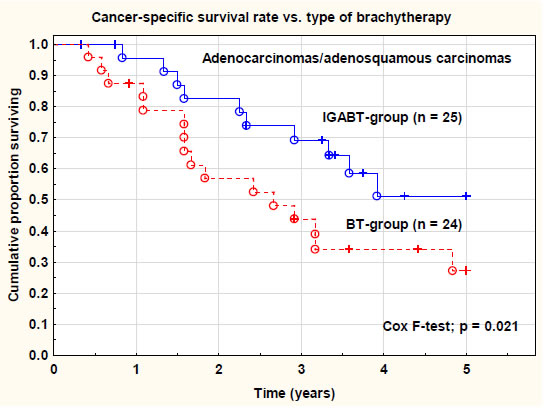

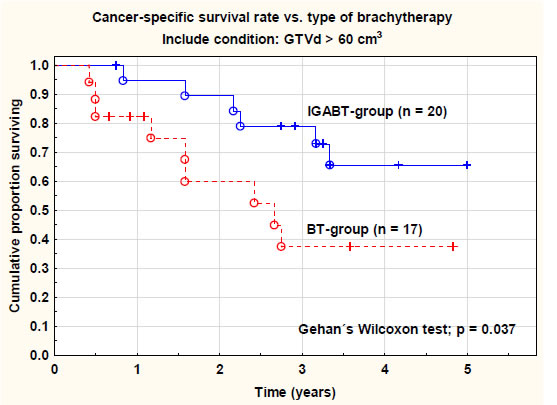

There were 118 deaths (73 cases due to cancer and 45 cases due to other diseases) during the study period giving a 5-year overall survival of 58.0% [95% CI: 57.4-58.6%] and cancer-specific survival of 68.5% [95% CI: 62.3-74.7] (Figure 1). The cancer-specific survival rate was similar in the two BT-groups (68.5% vs. 68.6%) in the complete series. FIGO stage had a significant impact on both overall and cancer-specific survival rate (Figure 2). Tumor size was highly significantly (Cox proportional regression analysis; p <0.001) associated with survival in the complete series. The cancer-specific survival rate was significantly higher in patients with large tumors (GTVd > 60 cm3) in the IGABT-group than in the BT-group (log-rank test; p < 0.05).Adenocarcinomas and adenosquamous carcinomas had a worse prognosis than squamous cell carcinomas. The difference was statistically significant in the BT-group but not in the IGABT-group. Five-year cancer-specific survival was 27.1% in the BT-group but 51.2% in the IGABT-group (Cox F-test; p = 0.021) for adenocarcinomas. No significant difference was noted for squamous cell carcinomas. Overall treatment time (OTT) was not significantly associated with cancer-specific survival rate. However, concomitant chemotherapy significantly (Cox F-test; p = 0.031) improved the 5-year cancer-specific survival rate.

Figure 1. Cancer-specific survival rate of the complete series (n = 272). Survival probability with 95% confidence levels.

Figure 2. Cancer-specific survival rate of the complete series (n = 272) versus FIGO-stage. There was a statistically highly significant (chi-square test; p < 0.0001) difference between the tumor stages.

Prognostic factors

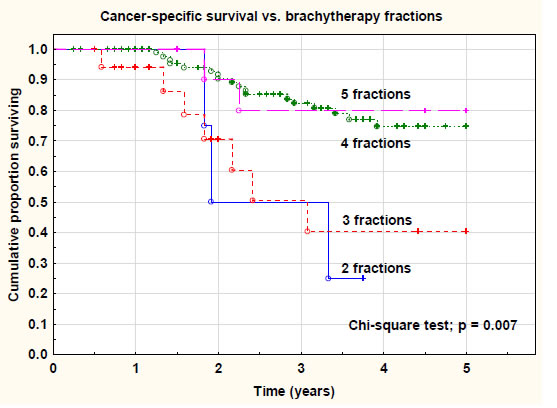

Ten significant prognostic factors for cancer-specific survival rate were identified in univariate Cox proportional regression analyses. However, of these factors only two: (1) pelvic control, and (2) distant tumor control (no distant recurrences) were significant and independent of each other in a Cox multivariate regression analysis (Table 5). In a multivariate analysis restricted only to factors available at the end of primary therapy (distant control was deleted) there were three significant and independent prognostic factors for cancer-specific survival rate: (1) primary cure rate (HR 0.196; p < 0.001), (2) overall local control (HR 0.200; p < 0.03), and (3) pelvic control (HR 0.180; p < 0.001).GTV at diagnosis (GTVd) and total brachytherapy dose (p < 0.001) were significant and independent prognostic factors.The number of brachytherapy fractions was also significantly associated with the cancer-specific survival rate. Four to five fractions seemed to be an optimal fractionation schedule.

Table 5. Disease outcome and morbidity versus type of brachytherapy.

|

Brachytherapy groups |

BT-group IGABT-group p value |

|

|

n = 134 n = 138 |

|

Local control after primary treatment |

|

|

Overall |

133 (99.2%) 134 (97.1%) 0.186 |

|

Local control (at last follow-up) |

|

|

Overall |

128 (95.5%) 130 (94.2%) 0.622 |

|

|

|

|

Pelvic control (at last follow-up) |

|

|

Overall |

111 (82.8%) 123 (89.1%) 0.134 |

|

|

|

|

Systemic control |

|

|

Overall (after primary therapy) |

125 (93.3%) 124 (89.9%) 0.130 |

|

Overall (at last follow-up) |

98 (73.1%) 94 (68.1%) 0.365 |

|

|

|

|

Cancer-specific survival rate (5-year) |

|

|

Overall |

68.5% [60.3-76.7] 68.6% [59.3-77.8] 0.895 |

|

|

|

|

Overall survival rate (5-year) |

|

|

Overall |

53.4% [45.0-61.8] 65.2% [55.6-74.8] 0.072 |

|

|

|

|

Morbidity |

|

|

Bladder CTCAE ≥ G1 |

23/134 (17.2%) 24/138 (17.4%) 0.965 |

|

Bladder CTCAE ≥ G2 |

10/134 (7.5%) 7/138 (5.1%) 0.415 |

|

Bladder CTCAE ≥ G3 |

5/134 (3.7%) 1/138 (0.7%) 0.090 |

|

Rectum-sigmoid CTCAE ≥ G1 |

66/134 (49.3%) 61/138 (44.2%) 0.404 |

|

Rectum-sigmoid CTCAE ≥ G2 |

34/134 (25.4%) 19/138 (13.8%) 0.016 |

|

Rectum-sigmoid CTCAE ≥ G3 |

17/134 (12.7%) 2/138 (1.5%) < 0.001 |

|

Vaginal CTCAE ≥ G2 (IGABT-group) |

NA 30/138 (21.7%) |

|

Vaginal CTCAE ≥ G3 (IGABT-group) |

NA 0/138 (0.0%) |

|

Bone CTCAE ≥ G1 (IGABT-group) |

NA 12/138 (8.7%) |

|

Bone CTCAE ≥ G2 (IGABT-group) |

NA 3/138 (2.2%) |

Late bladder and intestinal toxicity

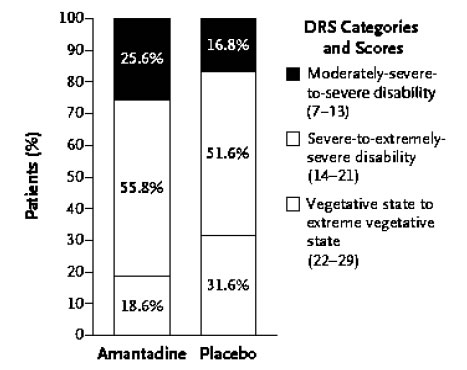

Bladder toxicity (CTCAE ≥ G1) was recorded in 53/272 patients (19.5%). There were no significant (p = 0.518) differences between the two brachytherapy groups.

Bladder toxicity (CTCAE ≥ G2) was recorded in 14 out of 272 patients (5.1%). In the BT-group it was 10/134 (7.5%) and in the IGABT-group it was 4/138 (2.9%) (Pearson chi-square test; p = 0.089). Bladder toxicity was highly significantly (t-test; p = 0.002) associated with the dose (EQD2,α/β = 3) to 2.0 cm3 of the bladder in the IGABT-group. However, the total external dose (EQD2, α/β = 3) was not significantly (p = 0.266) associated with toxicity of the bladder. Age was not a risk factor for late bladder toxicity (p = 0.641).A history of prior diseases was not associated (p = 0.871) with late bladder toxicity.Concurrent chemotherapy did not increase the risk of late bladder toxicity.

Bowel toxicity (CTCAE ≥ G1) was recorded in 127/272 patients (46.7%). There were no significant (p = 0.404) differences between the two brachytherapy groups. Bowel toxicity (CTCAE ≥ G2) was recorded in 53 out of 272 patients (19.5%). In the BT-group it was 34/134 (25.4%) and in the IGABT-group it was 19/138 (13.8%) (Pearson chi-square test; p = 0.016).

Bowel CTCAE ≥ G3 toxicity was noted in 19/272 (7.0%) in the complete series. In the BT-group it was noted in 17/134 (12.7%), but in the IGABT-group bowel CTCAE ≥ G3 was noted in only in 2/138 (1.5%). This difference was statistically highly significant (Pearson chi-square test; p < 0.0003).In the IGABT-group bowel toxicity (CTCAE ≥ G1) was significantly (Pearson chi-square; p = 0.005) associated with a prior history of abdominal surgery (gastrointestinal, urological or gynecological). Prior diseases (cardiovascular, diabetes, gastrointestinal and gynecological) also increased the risk of late bowel toxicity CTCAE ≥ G2 (p = 0.046).

Vaginal toxicity (only recorded in the IGABT-group)

Vaginal toxicity was significantly (Pearson chi-square; p = 0.022) associated (increased) with the number of brachytherapy fractions administered. The size of the HRCTV was also associated with the rate of vaginal toxicity (Pearson chi-square; p = 0.047).The total external dose (EQD2,α/β = 3) was only weakly (binary logistic regression analysis; p = 0.072) associated with the risk of vaginal toxicity.The rectal 2.0 cm3 dose (EQD2, α/β = 3) was not significantly (binary logistic regression; p = 0.143) associated with the risk of vaginal toxicity (grades 1-2).The vaginal 2.0 cm3 dose was not measured in this study [15]. The mean dose to the recto-vaginal reference point was 65.7 Gy (range 58-73 Gy). However, this dose was not significantly (logistic regression analysis; p = 0.468) associated with late vaginal toxicity in this series. Data of doses in this reference point was only available in 56 patients.

Vaginal toxicity (all grades) was more common (61/87, 70.1%) in the group treated with needles compared with the group without needles (30/52, 57.7%). However, the difference was not statistically significant (Pearson chi-square test; p = 0.136). Grade 2 toxicity was also more frequent in the needle group (21/86, 24.4%) than in the non-needle group (9/52, 17.3%), but still not significant (p = 0.326).The rate of vaginal toxicities was significantly higher (p = 0.007) during the later period (2013-2016) compared with the first period (2010-2013) of the study. (Tables 6 and 7)

Table 6. Prognostic factors for cancer-specific survival rate. Cox proportional regression analyses (univariate and multivariate analyses).

|

Factor univariate analyses |

Hazard ratio (95% CI) p value |

|

FIGO-stage (I-II vs. III-IV) |

0.300 [0.185-0.476] < 0.0001 |

|

Histology (squamous cell vs. adenocarcinoma) |

0.328 [0.203-0.531] < 0.0001 |

|

Lymph node metastases (pelvic or para-aortic) |

2.719 [1.410-5.243] < 0.01 |

|

Primary cure (complete remission) |

0.146 [0.084-0.255] < 0.0001 |

|

Overall local control |

0.308 [0.153-0.602] < 0.001 |

|

Pelvic control |

0.343 [0.206-0.571] < 0.0001 |

|

Distant control |

0.272 [0.170-0.433] < 0.0001 |

|

Hemoglobin level at start of treatment |

0.974 [0.961-0.987] < 0.0001 |

|

Total extern dose (Gy) – negative impact |

1.017 [1.017-1.106] < 0.01 |

|

Total brachytherapy dose (Gy) – positive impact |

0.903 [0.866-0.942] < 0.0001 |

|

Factor multivariate analysis |

|

|

Pelvic control |

0.133 [0.044-0.402] < 0.001 |

|

Distant control |

0.088 [0.036-0.218] < 0.0001 |

|

|

|

|

All other factors |

Non-significant > 0.05 |

|

Primary cure, overall local control and pelvic control were significant and independent if distant control was deleted |

|

Table 7. Predictive factors for overall tumor recurrences. Logistic regression analyses (univariate and multivariate analyses).

|

Factor univariate analyses |

Hazard ratio (95% CI) p value |

|

FIGO-stage (III-IV vs. I-II) |

2.894 [1.576-5.313] < 0.001 |

|

Lymph node metastases (pelvic or para-aortic) |

2.696 [1.204-6.036] < 0.02 |

|

Histology (adeno- vs. squamous cell carcinoma) |

1.700 [0.922-3.362] < 0.09 |

|

Hemoglobin value at start of therapy |

0.970 [0.952-0.988] < 0.002 |

|

Number of brachytherapy fractions |

0.095 [0.010-0.862] < 0.04 |

|

Total dose BT HRCTV D90 (α/β = 10) (Gy) |

0.950 [0.902-1.000] < 0.06 |

|

Total EBRT + BT-dose |

0.960 [0.925-0.997] < 0.04 |

|

Other factors |

Non-significant in univariate |

|

analysis |

|

|

Factor multivariate analysis |

|

|

FIGO-stage (III-IV vs. I-II) |

4.076 [1.387-11.977] < 0.01 |

|

Hemoglobin value at start of therapy |

0.962 [0.935-0.989] < 0.01 |

|

Other factors |

Non-significant in multivariate |

|

analysis |

|

Discussion

In this study, the importance of modern 3-D image-guided brachytherapy was emphasized. Two different series of advanced cervix carcinomas were studied with regard to the type of brachytherapy used. An older series (n = 134) using conventional 2-D conformal brachytherapy (BT) was compared with a newer series (n = 138) using 3-D image-guided adaptive brachytherapy (IGABT). All patients were also treated with external pelvic beam irradiation (± chemotherapy). The external beam technique and doses (EQD2 51-52 Gy) were rather similar in the two series. Tumor stage, tumor size, gross tumor volume, and histology were comparable during the study period. Concurrent chemotherapy was used more frequently in the later study group since it was introduced as part of the standard therapy in 1999 [6].

In the conventional brachytherapy-group MRI was not used as part of the planning process and interstitial needles were not an option during this period.

The mean number of brachytherapy fractions was significantly higher in the BT-group than in the IGABTT-group. A comprehensive set of dosimetric data was only available for the IGABT-group according to the Vienna protocol [11].

In the IGABT-group the number of brachytherapy fractions and the total brachytherapy dose (D90, α/β = 10) was significantly associated with the overall recurrence rate, distant recurrences, and cancer-specific survival rate. The optimal number of fractions seemed to be 4-5. The importance of the brachytherapy dose to the high-risk clinical target volume (HRCTV) was shown, in a multivariate analysis (logistic regression analysis), to be significant and independent together with the primary cure rate (complete remission) and the hemoglobin value at start of therapy. A total brachytherapy dose greater than 45 Gy had a significantly positive impact on cancer-specific survival rate. However, the total external dose (after correction for the brachytherapy dose) was not significantly associated with treatment outcome and negatively correlated with the brachytherapy dose. Thus, an increased external pelvic dose willprobably not compensate for exclusion of brachytherapy treatment. Prior studies have also confirmed the advantage of combined external and intracavitary therapy compared with external therapy alone [8, 16, 17]. The total dose (D90) to the HRCTV (external plus intracavitary) was significantly higher in the group treated with needles. This is in agreement with the study by Fokdal et al. 2016 [9].

The most important predictive factor for tumor recurrences was the dose to the HRCTV (total and from brachytherapy) but not the size of the HRCTV or the use of needles. Increasing the external dose, and then decreasing the brachytherapy dose, had a negative prognostic impact on tumor recurrences and on cancer-specific survival rate. The crude local control rate in this series was 94.2% which was superior of that reported in the RetroEMBRACE study (90.6%), presented by Sturdza et al. 2016 [7]. However, the crude pelvic control rate was the same (87.0%, 86.9%) in both studies.

The overall recurrence rate in this series was 28.7% which is comparable with our earlier study with 30% recurrences [18]. In the RetroEMBRACE-study the overall recurrence rate was 30.4%, [7] similar to our older data. The recurrence rate in the BT-group was 32.1% and in the IGABT-group 25.4%, not significantly different.

The 5-year cancer-specific survival in our series was 69% compared to 73% in the retro-EMBRACE series [7]. The cancer-specific survival rate was similar (69%) in the BT- and the IGABT-group. In a prior study with standard brachytherapy from our institution the cancer-specific survival rate was 65% (Sorbe et al. 2010) [18]. Thus, in our institution we have had a slight improvementof the 5-year cancer-specific survival rate. In a study from the Netherlands by Rijkmans et al. 2014 [19] showed a highly significant improved 3-year overall survival in the group with image-guided brachytherapy (86%) compared with conventional brachytherapy (51%). The 3-year overall survival in our IGABT-group was 75% for comparison.

The mean overall treatment time (OTT) of the complete series was 44 days and in 16.5% of the patients the overall treatment time was longer than 50 days. The OTT was significantly shorter (40 days) in the BT-group than in the IGABT-group (48 days). The OTT was not a significant predictive or prognostic factor in our study. However, in the retro-EMBRACE study on 488 patients presented by Tanderup et al. 2016 [20], the OTT was significantly associated with local tumor control in both univariate and multivariate analyses.The recommendation was to keep OTT shorter than 50 days.

In our study 74 patients (54%) in the IGABT-group received ≥ 5 cycles of chemotherapy. In the EMBRACE I study the corresponding figure was 70% [21]. The number of chemotherapy cycles was neither a predictive nor a prognostic factor for therapy outcome in our study. In a study by Schmid et al. 2014 [22] they found the number of chemotherapy cycles to be of prognostic importance in a high-risk group (positive lymph nodes and stage III-IV) for distant recurrences. We could not confirm this finding in our study.

Bladder toxicity (CTCAE ≥ G2) was recorded in 5% and CTCAE ≥ G3 in 2%, and it was highly significantly associated with the dose to 2.0 cm3 of the bladder [23]. The CTCAE ≥ G3 toxicity was more frequent in the BT-group (3.7%) than in the IGABT-group (0.7%). (Figure 3)

Figure 3. Cancer-specific survival rate of the complete series (n = 272) versus type of histology (squamous cell carcinomas versus adenocarcinomas/adenosquamous cell carcinomas/other types. There was a statistically highly significant (log-rank test; p < 0.0001) difference between the histological types.

Bowel toxicity (CTCAE ≥ G2) was noted in 19.5%, and bowel CTCAE ≥ G3 in 7.0% in the complete series. A significant favor of the IGABT-group was seen with regard to CTCAE ≥ G2 toxicity (13.8% vs. 25.4%) and CTCAE ≥ G3 late recto-sigmoid toxicity (1.5% vs. 12.7%). This difference was an important finding in this study. Bowel toxicity (all grades) was significantly associated with a prior history of abdominal surgery. This is a finding we also reported in a prior study (Bohr Mordhorst et al) [10]. Prior diseases (cardiovascular disease and diabetes) also increased the risk of late bowel toxicity. The brachytherapy fraction dose also increased the risk of late intestinal reactions.On the other hand, very few serious late reactions (grade 3-4) were noted in our study. In a study by Mazeron et al. [24] including 960 patients (EMBRACE I) a dose-volume effect was noted for D2cm3 ≤ 65 Gy and D2cm3 ≥ 75 Gy regarding minor or major late rectal toxicity [23]. In a prior study published from our institution serious late intestinal reactions (grade 3-4) occurred in 14% after a combined treatment of external beam pelvic radiotherapy and conventional brachytherapy [8]. This was an important improvement in the present study using MRI-guided IGABT compared with our older data and the BT-group not using this technique [10, 19]. (Figure 4)

Figure 4. Cancer-specific survival rate versus number of brachytherapy fractions. There was a significant difference (chi-square test; p = 0.007) between 2-3 fractions and 4-5 fractions.

Vaginal toxicity was only registered in the IGABT-group. It was significantly associated with the number of brachytherapy fractions administered. The size of the HRCTV was also associated with the rate of vaginal toxicity. Vaginal toxicity (all grades) was more common, but not significant, in the group treated with needles compared with the group without needles. (Figure 5 and 6)

Figure 5. Cancer-specific survival rate in adenocarcinomas/adenosquamous carcinomas versus type of brachytherapy. IGABT = image-guided adaptive brachytherapy. BT = conventional brachytherapy. There was a significant (Cox F-test; p = 0.021) difference in

the cancer-specific survival rate between the two groups.

Figure 6. Cancer-specific survival rate in large tumors (GTVd < 60 cm3) versus type of brachytherapy. IGABT = image-guided adaptive brachytherapy. BT = conventional brachytherapy. There was a significant (Gehan´s Wilcoxon test; p = 0.037) difference in the cancer-specific survival rate between the two groups. GTVd = gross tumor volume at diagnosis.

The individually designed external pelvic irradiation and adaptive brachytherapy (with or without needles) is probably an explanation for this improvement. The dose to the organs at risk was carefully evaluated and limited based on the well-known tolerability of these organs. The image-guided brachytherapy technique, using MRI before and during treatment, is of importance to achieve these results. This is a significant improvement compared with older data on conventional brachytherapy both from our institution and from other centers [13].

In the IGABT-group analyses of late toxicity (CTCAE ≥ G2) of the intestine and the bladder gave a clear impression of the importance of the total dose to the HRCTV (> 90 Gy, α/β = 3) and not the HRCTV-volume. All intestinal toxicity (CTCAE ≥ G2), except three cases, and all bladder toxicity (CTCAE ≥ G2), except two cases, occurred in patients who had received a D90 dose > 90 Gy to the HRCTV-volume. Five patients had both late bladder and intestinal toxicity and all of them had received a D90 dose> 90 Gy to HRCTV. However, analysis of all late toxicity (CTCAE ≥ G1) showed another pattern where both the dose level and the volume of HRCTV seemed to be of importance.

Recently, the problem with distal parametrial and pelvic wall invasion was addressed in a two-institutial study [25] using a newly developed applicator allowing the use of both parallel and oblique needles (Vienna-II). The treatment outcome seemed to be comparable to our results (local control, recurrences and survival data) when analyzed in FIGO-stages IIB-IVB, but with a substantial higher rate of serious late side effects (20% grade 3-4 toxicity, including 4 fistulas) and acute treatment related complications (active bleeding in 27%). In a smaller series of 10 patients and total 40 fractions another new hybrid applicator (Venezia) was tested and was found to be feasible and allowed improved dose coverage and sparing organs at risk [26].

Conclusion

Data from our study showed a local control rate > 94% for a D90 dose > 95 Gy to the HRCTV. To reduce late bladder and intestinal toxicity the recommended D90 dose was < 90 Gy to the HRCTV. These results are in agreement with data presented from the retroEMBRACE study. The reported data are excellent for local and loco-regional tumor controland similar in the BT- and IGABT-groups. However, for adenocarcinomas and tumors with large GTV the cancer-specific survival rate was significantly improved in the IGABT-group. Late toxicity from the organs at risk were most favorable after treatment with modern IGABT-technique. Still, there was a problem with distant recurrences (21%) negatively influencing the cancer-specific survival rate. A more individualized and tumor-specific and biologically oriented therapy is probably needed in the future.

Declaration of competing interest

The authors declare that there were no personal financial interests or other relationships that could influence the work reported in this paper.

Acknowledgments

We acknowledge the support of Hanna Rapp, MD, for collection of missing and follow-up clinical data from part of the medical region. The oncology nurses BeritBermark and Helené Johansson also took part in data collection.

References

- Bray F, Ferlay J, Soerjomataram I, Siegel RL, Torre LA, et al. (2018) Global cancer statistics 2018: GLOBOCAN estimates of incidence and mortality worldwide for 36 cancers in 185 countries. CA Cancer J Clin68: 394-424.[crossref]

- Marth C, Landoni F, Mahner S, McCormack M, Gonzalez-Martin A, et al. (2017) Cervical cancer: ESMO Clinical Practice Guidelines for diagnosis, treatment and follow-up. Ann Oncol 28: iv72-iv83.

- Vaccarella S, Franceschi S, Engholm G, Lonnberg S, Khan S, et al. (2014) 50 years of screening in the Nordic countries: quantifying the effects on cervical cancer incidence. Br J Cancer 111: 965-969.[crossref]

- Green JA, Kirwan JM, Tierney JF, Symonds P, Fresco L, et al. (2001) Survival and recurrence after concomitant chemotherapy and radiotherapy for cancer of the uterine cervix: a and radiotherapy. Systematic review and meta-analysis. Lancet 358:781-786.[crossref]

- Thomas GM (1999) Improved treatment for cervical cancer–concurrent chemotherapy and radiotherapy. N Engl J Med 340:1198-1200.[crossref]

- Rose PG, Ali S, Watkins E, Thigpen JT, Deppe G, et al. (2007) Long-term follow-up of a randomized trial comparing concurrent single agent cisplatin, cisplatin-based combination chemotherapy, or hydroxyurea during pelvic irradiation for locally advanced cervical cancer: a Gynecologic Oncology Group Study. J ClinOncol 25:2804-2810.[crossref]

- Sturdza A, Pötter R, Fokdal LU, Haie-Meder C, Tan LT, et al. (2016) Image guided brachytherapy in locally advanced cervical cancer: Improved pelvic control and survival in RetroEMBRACE, a multicenter cohort study. RadiotherOncol 120: 428-433.[crossref]

- Karlsson J, Dreifaldt AC, Mordhorst LB, Sorbe B (2017) Differences in outcome for cervical cancer patients treated with or without brachytherapy. Brachytherapy 16:133-140.[crossref]

- Fokdal L, Sturdza A, Mazeron R, Haie-Meder C, Tan LT, et al. (2016) Image guided adaptive brachytherapy with combined intracavitary and interstitial technique improves the therapeutic ratio in locally advanced cervical cancer: Analysis from the retroEMBRACE study. RadiotherOncol 120:434-440.[crossref]

- Bohr Mordhorst L,Karlsson L, Barmark B, Sorbe B (2014) Combined external and intracavitary irradiation in treatment of advanced cervical carcinomas: predictive factors for treatment outcome and early and late radiation reactions. Int J Gynecol Cancer 24:1268-1275.[crossref]

- Pötter R, Georg P, Dimopoulos JC, Grimm M, Berger D, et al. (2011) Clinical outcome of protocol based image (MRI) guided adaptive combined with 3D conformal radiotherapy with or without chemotherapy in patients with locally advanced cervical cancer. RadiotherOncol 100:116-123.[crossref]

- Dimopoulos JCA, Petrow P, Tanderup K,Petric P, Berger D, et al. (2012) Recommendations from Gynaecological (GYN) GEC-ESTRO working group (IV): Basic principles and parameters for MR imaging within the frame of image based adaptive cervix cancer brachytherapy. RadiotherOncol 103:113-122.[crossref]

- Nesvasil N, Tanderup K, Lindegaard JG, Richard Pötter, Christian Kirisits(2016) Can reduction of uncertainties in cervix cancer brachytherapy potentially improve clinical outcome? RadiotherOncol 120:390-396.[crossref]

- Auth B (2006) Therapy evaluation program, common terminology criteria for adverse events, version 3.0. DCTD, NCI, NIH, DHMS: 2003 (http://ctep.cancer.gov), publish date: August 9.

- Fidarova EF, Berger D, Schussler S, Dimopoulos J, Kirisits C, et al. (2010)Dose volume parameter D2cc does not correlate with vaginal side effects in individual patients with cervical cancer treated within a defined treatment protocol with very high brachytherapy doses. RadiotherOncol 97:76-79.[crossref]

- Yang J, Cai H, Xiao Z-X, Wang H, Yang P(2019) Effect of radiotherapy on the survival of cervical cancer patients. An analysis based on SEER database. Medicine98: e16421.[crossref]

- Delgado D, Figueiredo A, Mondonca V, Jorge M, Abdulrehman M, et al. (2019) Results from chemoradiotherapy for squamous cell cervical cancer with or without intracavitary brachytherapy. J Contemp Brachytherapy 11:417-422.

- Sorbe B, Bohr L, Karlsson L, Bermark B (2010) Combined external and intracavitary irradiation in treatment of advanced cervical carcinomas: predictive factors for local tumor control and early recurrences. Int J Oncol 36:371-378.[crossref]

- Rijkmans EC, Nout RA, Rutten IHHM,Ketelaars M, Neelis KJ, et al. (2014) Improved survival of patients with cervical cancer treated with image-guided brachytherapy compared with conventional brachytherapy. GynecolOncol 135:231-238.[crossref]

- Tanderup K, Fokdal LU, Sturdza A,HaieMeder C, Mazeron R, et al. (2016) Effect of tumor dose, volume and overall treatment time on local control after radiochemotherapy including MRI guided brachytherapy of locally advanced cervical cancer. RadiotherOncol 120:441-446.[crossref]

- Pötter R, Tanderup K, Kirisits C,Leeuw A, Kirchheiner K, et al. (2018) The EMBRACE II study: The outcome and prospect of two decades of evolution within the GEC-ESTRO GYN working group and the EMBRACE studies. ClinTranslRadiatOncol 9:48-60.[crossref]

- Schmid MP, Franckena M, Kirchheiner K,Sturdza A, Georg P, et al. (2014) Distant metastasis in patients with cervical cancer after primary radiotherapy with or without chemotherapy and image guided adaptiv brachytherapy. GynecolOncol 133:256-262.[crossref]

- Georg P, Pötter R, Georg D, Lang S, Dimopoulos J, et al. (2012) Dose effect relationship for late side effects of the rectum and urinary bladder in magnetic resonance image-guided adaptive cervix cancer brachytherapy. Int J RadiatOncolBiolPhys 82:653-657.[crossref]

- Mazeron R, Fokdal LU, Kirchheiner K, Georg P, Jastaniyah N, et al. (2016) Dose-volume effect relationships for late rectal morbidity in patients treated with chemoradiation and MRI-guided adaptive brachytherapy for locally advanced cervical cancer: Results from the prospective multicenter EMBRACE study. RadiotherOncol 120:412-419.[crossref]

- Mahantshetty U, Sturdza A, Naga CH P, Berger D, Fortin I, et al. (2019) Vienna-II ring applicator for distal parametrial/pelvic wall disease in cervical cancer brachytherapy: An experience from two institutions: Clinical feasibility and outcome. RadiotherOncol141: 123-129. [crossref]

- Walter F, Maihöfer C, Schüttrumpf L, Well J, Burges A, et al. (2018) Combined intracavitary and interstitial brachytherapy of cervical cancer using the novel hybrid applicator Venezia: Clinical feasibility and initial results. Brachytherapy17:775-781.[crossref]