DOI: 10.31038/JCRM.2019243

Abstract

We present a new approach to understanding how patients want doctors to communicate to them. The approach uses Mind Genomics, an emerging science in experimental psychology, which looks at the way people make decisions about the everyday. Respondents in an experiment evaluated different combinations of messages (elements) in vignettes. The results suggest three minds (privacy-oriented; doctor oriented; control-oriented), requiring three different types of messages. These mind-sets also pay attention to the messages in different ways, as shown by the pattern of their response times. We present a PVI (personal viewpoint identifier), which in six questions can suggest the mind-set to which a new person might belong.

Introduction

Patient self-management programs are the aim of health systems and public health policy makers. The main goal of health systems is to improve clinical outcomes of patients by engaging them to adhere to medications, to adopt a healthy lifestyle and to properly manage their illnesses. Patient adherence is defined as the degree to which patients follow physician’s guidelines and recommendations. Patient non-adherence has been a challenge for clinicians with evidence indicating that 25% to 50% of patients are non-adherent [1–4]. Furthermore, patients suffering a more severe illness in serious diseases were surprisingly less adherent [5]. Consequently, across illnesses non-adherence results in comorbidities, re-admissions to hospitals, in lower quality of life and in economic burdens for public health systems. Adherence to guidelines and medications was found to promote illness-self management (e.g., appointments, screening, exercise, and diet).Adherence is affected by: clinician-patient relationship, the illness itself, the treatment, patient characteristics and socioeconomic factors [6].

Patients expect their physicians to inspire them through communication leading to patient trust which is strongly related to medication-adherence[7–9]. Physician-patient communication was found to enhance patient adherence to decrease re-admissions [10,11]. To promote adherence patients need to understand the illness, the risks it entails and the treatment benefits [11]. Clinician-patient communication is an essential in adherence promotion [11–14]. Moreover, the odds of patient adherence are 2.16 times higher if a clinician communicates effectively [2,5,15].

Communication entails support, empathy and compassion leveraging collaborative patient-physician decision-making [9,12]. Whereas ‘content communication’ focuses on clinical aspects of the disease (e.g., the illness, the treatment regimens), ‘process communication’ focuses on psychosocial aspects (motivation, drivers, life–meaning, gathering information about the patient and environment, understanding how to remove barriers to adherence and identifying steps in the change process towards adherence.

‘Process communication has been report found to effectively raise patient-adherence [2,10,16–19]. Furthermore, patients who perceived their clinicians as their partners to the change process demonstrated a 19% higher medication-adherence. Furthermore, training physicians on ‘process communication’ improved patient-adherence by 12% [5,18,19]Essentials of behavioral research: methods and data analysis McGraw-Hill; 2007.

Despite evidence those clinicians’ skills of process communication are central to patient-adherence; clinicians mostly use content communication and have difficulties crossing this chasm [20]. Several factors underlie the challenge of crossing this chasm. First, there is a lack of sufficient training on psychosocial communication during and after medical school [20]. Second, there is a low prioritization of such skills in training programs [21]. Third, there is a lack of incentives for physicians to participate in such training [22]. Finally, there are misconceptions among physicians who perceive psychosocial communication as time consuming [23] when in fact it requires shorter, more effective time [18].

Previous studies suggest that interventions to improve psychosocial communication among clinicians should focus on a variety of aspects, not just one. These aspects are, respectively, verbal and nonverbal communication, affective communication, psychosocial communication and task-oriented behavior that create opportunities for active patient involvement throughout the change process towards patient-adherence [24]. Previous studies indicate that in order to reduce barriers which stand in the way of optimal health outcomes, communication is to be personalized enabling clinicians to understand what is most relevant for each particular patient and tailor the messages accordingly [4].

But what do we know about the mind of the patient? How can we find out what the patient feels to be important? What does the patient feel is relevant and irrelevant for her or him? In response to existent discourse in the literature, in 2011we conducted an internet experiment using Mind-Genomics to investigate combinations of messages on ‘living with the regimen’ (Moskowitz, unpublished observations).We identified three mind-sets. This study extends the 2011 study looking more closely at messages about how people feel about themselves in terms of how the doctor communicates with them. Our objective is to identify participants by psychographic mindsets so clinicians may quickly identify the belonging of each patient to a mindset and use tailored effective communication congruent to that mindset-segment in the context of medication adherence.

Method

Mind Genomics works in a Socratic fashion, first identifying a topic, then requiring the researcher to ask four questions, and finally requiring the researcher to provide four separate answers to each question. Inspired by existing literature and research instruments, we shaped questions which ‘tell a story’ [25–30]. Once the questions are asked, the answers are quickly provided. Asking the questions forces the researcher to think critically. Table 1 shows the four questions and the four answers to each question. The series of questions probe the way the person feels about information. The ‘story’ underlying the four questions is not sequential, but rather topic, as if an interview were being conducted with a person to under how the person feels about giving and receiving information about his or her own health status.

Table 1. Raw material comprising four questions, and four answers to each question

|

Question A: How would you like your doctor to discuss your health with you?

|

|

A1

|

Doctor talks to me, face to face… not just those phone calls with clinical message

|

|

A2

|

Doctor explains to me WHY this medicine, and what should I DO

|

|

A3

|

My friends explain this stuff to me… I’m more comfortable with them

|

|

A4

|

Doctor guides me to the Internet sites… so I CAN TAKE CONTROL

|

|

Question B: What honestly is your relationship with your health?

|

|

B1

|

I’m pretty private about my health… no one’s business

|

|

B2

|

I don’t feel like going to the doctor… even for the most severe symptoms… I can take care of it

|

|

B3

|

When it comes to illness, I’m on Google, so I really become an expert

|

|

B4

|

I’m nervous about health – but really want to be healthy to see my kids, grandkids, or even relatives and friends in the years to come

|

|

Question C: How do you interact with your family about your health?

|

|

C1

|

My family is always there to listen, and support me… I like that

|

|

C2

|

My family and others butt-in to my health… I want my privacy

|

|

C3

|

I really am happy when someone takes control, and tells me what to take, and schedules my meds for me

|

|

C4

|

I’m pretty private… my health meds are my business… and maybe the doctor’s, but that’s all

|

|

Question D: Do friends and family play an important role in your life?

|

|

D1

|

My family means the world to me

|

|

D2

|

I reach out to talk to friends about my health and illness

|

|

D3

|

I reserve my friends for non-medical talks, like politics, or people

|

|

D4

|

My friends really are there to listen to me about my medical experience – sometimes I feel I’m wearing out my welcome

|

Procedure

Vignettes: The test stimuli for Mind Genomics comprise easy-to-read vignettes, containing 2–4 answers or elements, at most one answer or element from each question. The vignettes are created according to an experimental design, which prescribes the specific combination. Each respondent evaluated 24 vignettes created according to the same basic design, with the specific combinations changing in a deliberate fashion according to a permutation scheme [31]. Thus, the entire experiment covered 24×100 or 2400 vignettes, most of which differed from each other.

It is important to note that the Mind Genomics approach to understanding is similar metaphorically to the MRI machine, which takes many different ‘pictures’ of the underlying tissue, each picture from a different angle and vantage point. Afterwards, a computer program combines these different views into a single 3-D image of the underlying tissue. Each individual picture may have error, but the entire pattern becomes clear once these individual pictures are combined. In a like fashion, Mind Genomics gets the response to many different vignettes, and then synthesizes the overall pattern. Each individual observation is ‘noisy’ with a base size of ‘1’ but the pattern is not as noisy.

The approach of Mind-Genomics covers a wide range of alternative clinical and psychosocial communication concepts, each with elements revealing response patterns by using various permutations of the same stimuli, responses to different combinations of the answers of elements, in order to obtain a stable estimate of the underlying pattern Conventional science attempts to minimize the error around each observation through replication of the same stimulus (average to increase precision)or through reduction of extraneous factors which could increase the error variability (suppressing noise to increase precision).

The respondents were selected at random from a pool of 20+ million respondents in the United States, with approximately equal distribution of age and gender. The respondents were part of the panel provided by the strategic partner of Mind Genomics, Luc.id, Inc. Respondents were compensated by Luc.id.

Each respondent who participated clicked on an embedded link in the email invitation and was taken to a first slide which oriented the respondent. The respondent was told to consider the entire vignette, the combination of elements (answers) as a ‘whole’ and to rate it on the scale below. The questions were never shown to the respondent. Only the answers were shown; the questions served simply as a way to elicit the set of appropriate answers that would be shown to the respondent in the vignette.

Imagine if these qualities were reflected on a magnet. How does this capture your thoughts?

1= Not at all like me. If this is a magnet, it just won’t work for me

5= Very much like me. This magnet will really help me

A surface analysis of the responses – distribution and means

Most surveys work with the responses to single questions and compute the mean of the responses. Mind Genomics proceeds by experimentation, presenting the respondent with combinations of answers or elements, and obtains their rating. The actual ratings themselves pertain to different test stimuli. Furthermore, an inspection of the different patterns across gender and ages fails to give us any insight into the mind of the respondent with respect to feelings about discussing one’s own state of health and receptivity to health information. The means across key subgroups (Table 2) provides little insight, other than perhaps that older respondents had a longer response time, on average, than did younger respondents. A deeper analysis is necessary to understanding the meaning of the data, not just the surface morphology of the response patterns.

Table 2. Mean ratings on the 5-point rating scale, by total panel, gender, and ages

|

|

5- Point RATING

|

Binary TOP2 (Works YES)

|

Binary BOT2 (Works No)

|

Response Time

|

|

Total

|

3.2

|

42

|

31

|

5.0

|

|

Male

|

3.1

|

42

|

32

|

4.7

|

|

Female

|

3.2

|

42

|

31

|

5.4

|

|

Age 18–30

|

3.2

|

38

|

30

|

4.3

|

|

Age 31–49

|

3.4

|

53

|

27

|

4.5

|

|

Age 50–64

|

2.9

|

34

|

37

|

6.1

|

Transforming the data in preparation for regression modeling

In consumer research an oft-heard complaint from managers who use the data is ‘what does the rating point mean?’ In consumer research, the values of the scales are not necessarily easy to understand. That is, for researchers and respondents it seems easy to use the 5-point or 9-point or even a 100-point like rt scale. It may take a bit of use for a respondent, but sooner or later, usually sooner, the respondent falls into a pattern and intuitively senses that ‘this vignette is a 3 or a 4.’

One strategy commonly used, and adopted here, divides the scale into two regions, typically the high region (scale points 4–5) to denote a positive feeling about the vignette, and the remaining low region (scale points 1–3) to denote a negative feeling. We are interested in both sides of the scale, however, specifically what ‘works’ and what ‘don’t work’. Thus, we divide the scale twice, first into the top part and then second into the bottom part:

Works YES – Ratings 1–3 transformed to 0, ratings 4–5 transformed to 100

Works NO – Ratings 1–2 transformed to 100, ratings 3–5 transformed to 0.

The transformation removes some of the granular information but makes the results easy to understand. Managers who work with the data understand in an intuitive sense, because the information is presented in a all-or-none fashion.

Regression Modeling

The experimental design makes it straightforward to apply OLS (ordinary least-squares) regression to the raw data, after transformation. The data matrix comprises 16 independent variables, the elements, coded as 1 when present in the vignette, and coded as 0 when absent from the vignette. The matrix comprises three dependent variables, the binary transformation for Works YES (4–5 coded as 100, 1–3 coded as 0), the binary transformation for Works NO (1–2 coded as 100, 3–5 coded as 0), and the response time in seconds with the resolution to the nearest tenth of second. The response time is defined as the recorded time between the appearance of the vignette on the respondent’s screen and the time to assign a rating, which the respondent did by pressing a key.

Results –Total Panel

OLS regression generates an equation relating the presence/absence of the 16 answers or elements to the response. Table 2 shows the parameters of the three equations, one each for the positive Works YES, the negative Works NO, and the response time.

The additive constant (Works YES, Works NO) shows the estimated percent of the time the answer would be ‘Works YES or Works NO, in the absence of any elements. The additive constant represents a baseline, but not an actual situation because all vignettes by design comprised 2–4 elements or answers.’

The coefficient for each element shows the additive percent of the responses that would be expected to shift from ‘not Works YES’ to ‘Works Yes’ (or from ‘not Works NO’ to ‘Works NO), when the element is incorporated into a vignette. Statistical analyses as well as previous research by author Moskowitz suggest a standard error of approximately 4 for the coefficient, making values of 6–7 begin to reach statistical significance.

The results lead to some immediate and easy interpretation because the test elements are cognitively rich. We don’t have to stand back and search for a pattern in the way we do when we are looking at the pattern described by set of otherwise mute measures. Rather, we can understand the nature of a pattern simply by looking at the elements which score well, with high coefficients for the two binary scales (Works YES, Works NO) and long response times.

What ‘works’ for the respondent (Adherence promotion): The additive constant is 43, meaning that in the absence of anything else, we expect about 43% of the responses to be 4–5 for ‘Works YES.’ This means that if we were to ask a person whether giving and receiving medical information from various sources in general ‘works for that person’ almost 50% of the time we would get a positive answer. The strongest performers comprise a mix of statements about getting information directly from the doctor (Doctor talks to me, face to face… not just those phone calls with clinical message) as well as emotional messages (I’m nervous about health – but really want to be healthy to see my kids, grandkids, or even relatives and friends in the years to come and My family means the world to me.)

What doesn’t ‘work’ for the respondent (Adherence prevention): The additive constant is 30; meaning about 30% of the time we will get responses that say ‘doesn’t work for me’ the key message which resonates in a negative way is ‘I don’t feel like going to the doctor… even for the most severe symptoms… I can take care of it. This is not an easy negative to resolve.

Response time: The model for response time does not have an additive constant. The rationale is that without any elements, there is no response at all.

Studies on health drive respondents to pay a great deal of attention to the vignettes. Table 2 shows that the average for the total panel is approximately 5 seconds for a vignette. The response time, when deconstructed into the contributions of the different messages, show that there is a range of response times, all of which are high compared to the response times from previous studies. In this study the estimated response times for the individual answers or elements vary from a high of 1.8 seconds to a low of 1.1 seconds. We end up with these long response times when we deal with topics relevant to the respondent, issues which engage and make the respondent think. In contrast, when we deal with less relevant topics, e.g., studies about products such as foods, we see far shorter response times. It might be that the messages are easier with foods, being tag lines and short descriptions. Whatever the reason for the difference, the response times are far longer here.

The longer response times are those which ‘engage.’ They may be positive or negative, but they ‘engage’ the respondent, holding the attention. The most engaging elements are these below, describing who the person is, and perhaps forcing the respondent to compare him or herself. One can sense that each of these statements is a ‘conversation opener.’

When it comes to illness, I’m on Google, so I really become an expert I’m pretty private about my health… no one’s business

I really am happy when someone takes control, and tells me what to take, and schedules my meds for me

My family and others butt-in to my health… I want my privacy

I’m nervous about health – but really want to be healthy to see my kids, grandkids, or even relatives and friends in the years to come

I don’t feel like going to the doctor… even for the most severe symptoms… I can take care of it

In contrast, the least engaging elements are those of practice, with a sense that there is no conversation to be started

Doctor explains to me WHY this medicine, and what should I DO

I reach out to talk to friends about my health and illness

Table 3. Coefficients relating the presence/absence of the 16 answers (elements) to the binary transformed ratings, and to response time. The table is sorted by Works YES

|

|

Works YES

|

Works NO

|

Resp Time

|

|

Additive constant

|

43

|

30

|

|

|

A1

|

Doctor talks to me, face to face… not just those phone calls with clinical message

|

7

|

-8

|

1.3

|

|

B4

|

I’m nervous about health – but really want to be healthy to see my kids, grandkids, or even relatives and friends in the years to come

|

6

|

-1

|

1.6

|

|

D1

|

My family means the world to me

|

6

|

-6

|

1.3

|

|

A2

|

Doctor explains to me WHY this medicine, and what should I DO

|

5

|

-5

|

1.2

|

|

D4

|

My friends really are there to listen to me about my medical experience – sometimes I feel I’m wearing out my welcome

|

1

|

2

|

1.5

|

|

C4

|

I’m pretty private… my health meds are my business… and maybe the doctor’s, but that’s all

|

1

|

0

|

1.4

|

|

A4

|

Doctor guides me to the Internet sites… so I CAN TAKE CONTROL

|

0

|

-3

|

1.4

|

|

B3

|

When it comes to illness, I’m on Google, so I really become an expert

|

-1

|

3

|

1.8

|

|

C1

|

My family is always there to listen, and support me… I like that

|

-1

|

0

|

1.5

|

|

B1

|

I’m pretty private about my health… no one’s business

|

-2

|

5

|

1.7

|

|

A3

|

My friends explain this stuff to me… I’m more comfortable with them

|

-2

|

0

|

1.3

|

|

D3

|

I reserve my friends for non-medical talks, like politics, or people

|

-3

|

1

|

1.4

|

|

D2

|

I reach out to talk to friends about my health and illness

|

-3

|

-2

|

1.1

|

|

C3

|

I really am happy when someone takes control, and tells me what to take, and schedules my meds for me

|

-5

|

6

|

1.7

|

|

C2

|

My family and others butt-in to my health… I want my privacy

|

-6

|

4

|

1.7

|

|

B2

|

I don’t feel like going to the doctor… even for the most severe symptoms… I can take care of it

|

-7

|

11

|

1.6

|

Scenario Analysis: Uncovering Pair-Wise Interactions among Answers/Elements: The messages that we encounter in the environment comprise combinations of ideas, rather than single ideas in ‘splendid isolation.’ We know that in the world of food, the taste of a food is determine by the interplay of ingredients, and that experimental design of ingredients can help us understand the nature of that interplay, also called ‘pairwise interaction’. In consumer research with ideas, we may test single messages (promise testing), or test combinations of messages in a final format (concept testing), but rarely do we search for significant pairwise interactions in the world of ideas. There are so-called ‘creative’ in the advertising agency who may be aware that some ideas ‘synergize’ when in pairs, but this knowledge is specific, experienced-based, and hard to create in a systematic fashion on a go-forward basis.

A key benefit of the Mind Genomics approach is the ability to cover many combinations of ideas in the vignettes, all combinations prescribed by a basic experimental design which is permuted (Gofman & Moskowitz, 2010.) Adhering to the experimental design forces the research to work with a wide number of different combinations. In fact, among the 2400 vignettes created for this study, most are unique. Within the 2400 combinations, specific pairs of messages appear several times. It is this property that the various pairs of messages appear several times across the permutations which makes it possible to hold one the options of one question constant a specific option (e.g., one of the options for Question A: How would you like your doctor to discuss your health with you?), and then assess how the vignettes perform when that specific option is held constant.

Table 4 presents the scenario analysis for the positive responses (Works YES), and Table 5 presents the scenario analysis for the negative response (Works NO). The analysis works in a straightforward manner, following these steps:

Table 4. Scenario analysis, revealing pairwise Interactions to drive perceived positive responses, ‘Works YES’

|

|

Element held constant in the vignette

|

|

|

A0

|

A1

|

A2

|

A3

|

A4

|

|

Top 2 – Works YES (Positive Outcome)

|

No element from question A

|

Doctor talks to me, face to face… not just those phone calls with clinical message

|

Doctor explains to me WHY this medicine, and what should I DO

|

My friends explain this stuff to me… I’m more comfortable with them

|

Doctor guides me to the Internet sites… so I CAN TAKE CONTROL

|

|

|

A0

|

A1

|

A2

|

A3

|

A4

|

|

Additive Constant

|

28

|

53

|

50

|

50

|

34

|

|

B4

|

I’m nervous about health – but really want to be healthy to see my kids, grandkids, or even relatives and friends in the years to come

|

15

|

10

|

1

|

-5

|

17

|

|

D1

|

My family means the world to me

|

14

|

-8

|

3

|

16

|

11

|

|

C4

|

I’m pretty private… my health meds are my business… and maybe the doctor’s, but that’s all

|

11

|

-5

|

1

|

-9

|

11

|

|

B1

|

I’m pretty private about my health… no one’s business

|

7

|

7

|

-4

|

-17

|

-2

|

|

D2

|

I reach out to talk to friends about my health and illness

|

6

|

-9

|

-4

|

-7

|

3

|

|

B3

|

When it comes to illness, I’m on Google, so I really become an expert

|

5

|

12

|

0

|

-8

|

-6

|

|

C2

|

My family and others butt-in to my health… I want my privacy

|

2

|

-15

|

-10

|

-1

|

-5

|

|

B2

|

I don’t feel like going to the doctor… even for the most severe symptoms… I can take care of it

|

1

|

1

|

-5

|

-24

|

-6

|

|

C1

|

My family is always there to listen, and support me… I like that

|

1

|

-5

|

1

|

-1

|

-3

|

|

C3

|

I really am happy when someone takes control, and tells me what to take, and schedules my meds for me

|

0

|

-7

|

-3

|

-3

|

-7

|

|

D4

|

My friends really are there to listen to me about my medical experience – sometimes I feel I’m wearing out my welcome

|

-2

|

-2

|

-1

|

-2

|

17

|

|

D3

|

I reserve my friends for non-medical talks, like politics, or people

|

-6

|

-8

|

-3

|

5

|

4

|

Table 5. Scenario analysis, revealing pairwise Interactions to drive perceived negative responses, ‘Works NO’

|

Bot 2 – Works NO (Negative Outcome)

|

No element from question A

|

Doctor talks to me, face to face… not just those phone calls with clinical message

|

Doctor explains to me WHY this medicine, and what should I DO

|

My friends explain this stuff to me… I’m more comfortable with them

|

Doctor guides me to the Internet sites… so I CAN TAKE CONTROL

|

|

|

A0

|

A1

|

A2

|

A3

|

A4

|

|

Additive Constant

|

37

|

21

|

23

|

27

|

31

|

|

C3

|

I really am happy when someone takes control, and tells me what to take, and schedules my meds for me

|

9

|

1

|

7

|

8

|

7

|

|

C2

|

My family and others butt-in to my health… I want my privacy

|

6

|

4

|

4

|

5

|

5

|

|

C1

|

My family is always there to listen, and support me… I like that

|

5

|

3

|

0

|

-2

|

-1

|

|

B2

|

I don’t feel like going to the doctor… even for the most severe symptoms… I can take care of it

|

4

|

7

|

7

|

16

|

13

|

|

D3

|

I reserve my friends for non-medical talks, like politics, or people

|

2

|

2

|

6

|

-4

|

-6

|

|

D4

|

My friends really are there to listen to me about my medical experience – sometimes I feel I’m wearing out my welcome

|

2

|

8

|

2

|

-2

|

-4

|

|

C4

|

I’m pretty private… my health meds are my business… and maybe the doctor’s, but that’s all

|

0

|

0

|

1

|

7

|

-8

|

|

B1

|

I’m pretty private about my health… no one’s business

|

-5

|

0

|

7

|

12

|

9

|

|

D1

|

My family means the world to me

|

-6

|

2

|

-2

|

-17

|

-9

|

|

D2

|

I reach out to talk to friends about my health and illness

|

-8

|

8

|

0

|

-3

|

-8

|

|

B3

|

When it comes to illness, I’m on Google, so I really become an expert

|

-9

|

-3

|

4

|

9

|

8

|

|

B4

|

I’m nervous about health – but really want to be healthy to see my kids, grandkids, or even relatives and friends in the years to come

|

-11

|

-6

|

-2

|

8

|

-6

|

- Identify the variable to be held constant. In our study, this is Question A: How would you like your doctor to discuss your health with you?

- In our 4×4 design (four questions, four answers per question), Question A has five alternatives, comprising the four answers and the ‘no answer’ option wherein Question A does not contribute to a vignette.

- We sort the full set of 2400 records, one record per vignette per respondent, based upon the specific answer. This step ‘stratifies’ the database, into five strata, one stratum for each answer. One stratum comprises those vignettes without an answer to Question A.

- We then run the OLS regression on each stratum, but do not use A1-A4 as independent variables since they are held constant in a stratum.

- The coefficients tell us the contribution of each element to WORKS YES, for a specific answer.

- Thus, when we have A0, we deal with no answer from Question A.

- The additive constant is 28, meaning that for these vignettes we are likely to get only 28% positive response (works for ME, rating 4–5).The additive constant, 28, is probably the lowest level we will reach in basic response.

- Three very strong performing answers emerge. These are likely to lead to strong positive feelings, even starting from the low baseline of 28

I’m nervous about health – but really want to be healthy to see my kids, grandkids, or even relatives and friends in the years to come

My family means the world to me

I’m pretty private… my health meds are my business… and maybe the doctor’s, but that’s all

- Now let us move to the strongest performing answer, A1: Doctor talks to me, face to face… not just those phone calls with clinical message. When this answer is the keystone of the vignette, the additive constant jumps up to 53. That means that in the absence of anything else, just knowing that message increases the frequency of positive answers 4–5 on the 5-point scale, namely Works YES

- When we combine this strong basic idea presented in A1 with the two answers or elements below, we end up with an additional 10% to 12% positive responses.

When it comes to illness, I’m on Google, so I really become an expert

I’m nervous about health – but really want to be healthy to see my kids, grandkids, or even relatives and friends in the years to come

- When we run the scenario analysis looking at the Works NO (a negative outcome), we see that without any element from question A, the additive constant is highest (37), and then decreases as the doctor becomes increasing involved. When the doctor talks with the respondent, the additive constant is lowest (A1 = face to face = additive constant 21; A2 = doctor explains = additive constant 23.)

The most negative elements come from interactions where either the friends explain the medical material, or the doctor guides the respondent to the internet, allowing the respondent to take control.

- Response time. We can perform the same scenario analysis. This time, however, we eliminate the condition where an answer to A does not appear (A0). Table 6 shows the dramatic effects of interaction. The response time changes depending upon the specific element from question A about how the respondent wants to get information. A dramatic example comes from answer A1 (doctor talks to me face to face…). When A1 is paired with B1 (I’m pretty private about my health … no one’s business) the response time for element B1 is 3.0 seconds. When A4 (Doctor guides me to the internet sites…) is paired with B1, the response time for element B1 is just about half, 1.4 seconds.

Table 6. Scenario analysis, revealing pairwise Interactions to drive response time

|

|

Doctor talks to me, face to face… not just those phone calls with clinical message

|

Doctor explains to me WHY this medicine, and what should I DO

|

My friends explain this stuff to me… I’m more comfortable with them

|

Doctor guides me to the Internet sites… so I CAN TAKE CONTROL

|

|

|

A1

|

A2

|

A3

|

A4

|

|

B1

|

I’m pretty private about my health… no one’s business

|

3.0

|

2.1

|

2.2

|

1.4

|

|

B3

|

When it comes to illness, I’m on Google, so I really become an expert

|

2.6

|

2.3

|

2.2

|

1.8

|

|

C1

|

My family is always there to listen, and support me… I like that

|

2.5

|

1.4

|

1.6

|

2.3

|

|

B4

|

I’m nervous about health – but really want to be healthy to see my kids, grandkids, or even relatives and friends in the years to come

|

2.3

|

2.0

|

2.3

|

1.3

|

|

D4

|

My friends really are there to listen to me about my medical experience – sometimes I feel I’m wearing out my welcome

|

1.2

|

2.4

|

2.0

|

2.5

|

|

B2

|

I don’t feel like going to the doctor… even for the most severe symptoms… I can take care of it

|

2.2

|

1.8

|

2.5

|

1.4

|

|

C3

|

I really am happy when someone takes control, and tells me what to take, and schedules my meds for me

|

2.0

|

1.6

|

2.0

|

2.6

|

|

C2

|

My family and others butt-into my health… I want my privacy

|

1.5

|

1.8

|

1.7

|

2.4

|

|

D3

|

I reserve my friends for non-medical talks, like politics, or people

|

1.7

|

2.0

|

2.0

|

2.2

|

|

C4

|

I’m pretty private… my health meds are my business… and maybe the doctor’s, but that’s all

|

1.8

|

1.5

|

1.8

|

2.0

|

|

D1

|

My family means the world to me

|

1.7

|

1.9

|

1.6

|

2.0

|

|

D2

|

I reach out to talk to friends about my health and illness

|

1.2

|

2.0

|

1.7

|

1.8

|

It is clear from Table 6 that there is cognitive processing occurring, with the data suggesting that mutually contradictory elements, in terms of implications, the respond processes the information, attempting to resolve these contradictory elements.

Responses from Key Subgroups

Positive Outcome (Works YES): Table 7 presents the performance of the elements by key subgroups, comprising gender, age, and stated concern about their health. In the interest of easing the inspection, we present only those elements which score well with at least one of the key subgroups.

Table 7. Performance of the answers/elements by key subgroup for the criterion ofWorks YES. Only strong performing elements for at least one subgroup are shown

|

Top 2 – Works YES

|

Male

|

Female

|

Age 18–30

|

Age 31–49

|

FW 50+

|

Don’t think

|

Healthy

|

Concerned

|

|

Additive Constant

|

45

|

42

|

29

|

58

|

33

|

26

|

48

|

43

|

|

A1

|

Doctor talks to me, face to face… not just those phone calls with clinical message

|

5

|

10

|

7

|

4

|

12

|

17

|

-3

|

16

|

|

A2

|

Doctor explains to me WHY this medicine, and what should I DO

|

9

|

1

|

2

|

7

|

4

|

6

|

2

|

7

|

|

A3

|

My friends explain this stuff to me… I’m more comfortable with them

|

0

|

-3

|

1

|

3

|

-6

|

17

|

-6

|

0

|

|

A4

|

Doctor guides me to the Internet sites… so I CAN TAKE CONTROL

|

2

|

-2

|

3

|

4

|

-2

|

22

|

-4

|

2

|

|

B3

|

When it comes to illness, I’m on Google, so I really become an expert

|

-4

|

3

|

2

|

-2

|

-1

|

9

|

-1

|

-2

|

|

B4

|

I’m nervous about health – but really want to be healthy to see my kids, grandkids, or even relatives and friends in the years to come

|

3

|

8

|

10

|

1

|

8

|

-1

|

1

|

11

|

|

D1

|

My family means the world to me

|

4

|

8

|

3

|

-1

|

16

|

1

|

4

|

8

|

|

D4

|

My friends really are there to listen to me about my medical experience – sometimes I feel I’m wearing out my welcome

|

4

|

-2

|

13

|

-4

|

-2

|

5

|

0

|

1

|

The key differences emerge from the additive constants and a few elements, only. Most respondents are positive. The least positives are two groups; those age 18–30 (additive constant = 29) and those age 50+ (additive constant 33) and those not concerned with their health (additive constant = 26). The only groups which surprises are those age 50+.

Looking across subgroups, we find two messages which appear to do well on a consistent basis

Doctor talks to me, face to face… not just those phone calls with clinical message

But really want to be healthy to see my kids, grandkids, or even relatives and friends in the years to come

Looking down, within a subgroup, we find some patterns which strongly resonate, and are meaningful when we think about the needs and wants of the subgroup.

Those age 50+

I’m nervous about health – but really want to be healthy to see my kids, grandkids, or even relatives and friends in the years to come

My family means the world to me

Those who classify themselves as not concerned

Doctor talks to me, face to face… not just those phone calls with clinical message

My friends explain this stuff to me… I’m more comfortable with them

Doctor guides me to the Internet sites… so I CAN TAKE CONTROL

When it comes to illness, I’m on Google, so I really become an expert

When we perform the same analysis, this time for the lower part of the scale (Works NO), where ratings 1–2 were assigned 100, and ratings 3–5 were assigned 0, we find a different pattern. We again present only those elements which score strongly among at least one of the subgroups.

When we look at the key subgroups, we find that most of the groups begin with a low additive constant, which means that they feel these messages will not do any harm. The two groups which surprise are those who are age 50+ (additive constant = 44) and those who say that they are concerned about their health (additive constant = 48.)The likelihood is probably their fear that the ‘wrong’ thing could exacerbate a problem. In contrast those who are age 31–49 show a very low additive constant (12), as do those who classify themselves as health (additive constant = 18).

The additive constant provides only part of the story. Some of the elements drive a perception of poor outcomes, especially those who call themselves healthy. A pleasant surprise is that the elements which these self-described healthy respondents feel to lead to a bad outcome are those which talk about avoiding the medical establishment. That is, those who consider themselves health are already aware of good practices, and react negatively to poor practices, as shown by the high coefficients for this reversed scale.

I don’t feel like going to the doctor… even for the most severe symptoms… I can take care of it

I’m pretty private about my health… no one’s business

My friends explain this stuff to me… I’m more comfortable with them

Emergent Mind Sets Showing Different Patterns of What is Important

One of the ingoing premises of Mind Genomics is that within any topic area where people make decisions or have points of view there exist mind-sets, groups of ideas which ‘go together.’ Mind Genomics posits that at any specific time, a given individual will have only one of the several possible mind-sets, although over time, e.g., years or due to some unforeseen circumstance, one’s mind-set will change.

The metaphor for a mind-set it a mental genome. There is no limit to the number of such mental genomes, at least in terms of defining them by experiments. Virtually every topic can be broken down into smaller and smaller topics, and studied, from the very general to the most granular. In that respect, Mind Genomics differs from its namesake, Biological Genomics, which posits that there are a limited number of possible genes. In Mind Genomics, each topic area comprises a limited number of mind genomes, but there are uncountable topics.

The notion of mind-sets in the population, these so-called mind genomes, opens a variety of vistas. From the vantage point of psychology, the mind-genomes present the opportunity to study individual differences in the world of the everyday, and to systematize these differences, perhaps even finding ‘supersets’ of mind genomes which go across many different types of behavior. From the vantage point of biology, discovering mind-genomes holds the possibility of ‘correlating’ mind-genomes with actual genomes. And finally, from the vantage point of economics and commerce, discovering the pattern of a person’s mind genomes leads to better customer experience, and perhaps more responsiveness to suggestions about lifestyle modifications in the search for better health. The last is the focus of this study, the search for how to best communicate to people.

The process of uncovering mind genomes or mind-sets is empirical, modeling the relation between elements and responses (our Works YES model), clustering the respondents on the basis of the pattern of their coefficients, and finally extracting clusters which are few in number (parsimony), and which are coherent and meaningful, telling a ‘simple story’ (interpretability).Clustering has become a standard method in exploratory data analysis (e.g., Dubes & Jain, 1980.)

The approach to creating these mind-sets has already been documented extensively in [25–30]. It is vital to keep in mind that modeling and clustering is virtually automatic and intellectual agnostic. It takes a researcher to determine whether the clusters, the so-called mind-sets, really make sense when interpreted. There is no way for the clustering algorithm to easily interpret the meaning of the clusters other than perhaps doing a word count. The involvement of the research is vital, albeit not particularly taxing. The computer program does all the work.

The clustering based on the positive outcome models (Works YES) suggest three interpretable mind-sets, shown in Table 9 fop the positive outcome, Works YES, and in Table 10 for the negative outcome, Works NO. The names for the mind-sets were selected on the basis the elements which scored highest for the Works YES models. The mind-sets make sense (privacy seeker; doctor focus; control focus) for both the positive and the negative models (Works YES, Works NO), respectively. The clustering also parallels preliminary results from the aforementioned study run eight years before, in 2011(Moskowitz, unpublished), which suggested three similar three mind-sets of this type. It is important to note that these mind-sets are not ‘set in stone,’ but rather represent interpretable areas in what is more likely a continuum of preferences.

Table 9. Performance of the answers/elements by three emergent mind-sets for the criterion of Works YES

|

Positive Outcome – Works YES

(Basis for the mind-set segmentation)

|

MS3 Privacy-seeker

|

MS2 Doctor focus

|

MS1 Control focus

|

|

Additive constant

|

45

|

50

|

34

|

|

C4

|

I’m pretty private… my health meds are my business… and maybe the doctor’s, but that’s all

|

15

|

-1

|

-13

|

|

A1

|

Doctor talks to me, face to face… not just those phone calls with clinical message

|

-7

|

15

|

16

|

|

A2

|

Doctor explains to me WHY this medicine, and what should I DO

|

-11

|

11

|

16

|

|

A4

|

Doctor guides me to the Internet sites… so I CAN TAKE CONTROL

|

-15

|

11

|

8

|

|

D1

|

My family means the world to me

|

-5

|

10

|

15

|

|

B4

|

I’m nervous about health – but really want to be healthy to see my kids, grandkids, or even relatives and friends in the years to come

|

3

|

2

|

14

|

|

D4

|

My friends really are there to listen to me about my medical experience – sometimes I feel I’m wearing out my welcome

|

-9

|

5

|

9

|

|

D2

|

I reach out to talk to friends about my health and illness

|

-11

|

-3

|

8

|

|

B3

|

When it comes to illness, I’m on Google, so I really become an expert

|

5

|

-16

|

8

|

|

A3

|

My friends explain this stuff to me… I’m more comfortable with them

|

-16

|

6

|

7

|

|

B1

|

I’m pretty private about my health… no one’s business

|

5

|

-19

|

5

|

|

D3

|

I reserve my friends for non-medical talks, like politics, or people

|

-2

|

-8

|

3

|

|

B2

|

I don’t feel like going to the doctor… even for the most severe symptoms… I can take care of it

|

5

|

-23

|

-6

|

|

C3

|

I really am happy when someone takes control, and tells me what to take, and schedules my meds for me

|

0

|

-3

|

-12

|

|

C1

|

My family is always there to listen, and support me… I like that

|

4

|

7

|

-14

|

|

C2

|

My family and others butt-in to my health… I want my privacy

|

2

|

-2

|

-18

|

Table 10. Performance of the answers/elements by three emergent mind-sets for the criterion of Works NO

|

Negative Outcome – Works NO

|

MS3 Privacy-focus

|

MS2 Doctor focus

|

MS1 Control focus

|

|

Additive constant

|

24

|

34

|

31

|

|

A3

|

My friends explain this stuff to me… I’m more comfortable with them

|

16

|

-5

|

-11

|

|

D4

|

My friends really are there to listen to me about my medical experience – sometimes I feel I’m wearing out my welcome

|

11

|

-8

|

-1

|

|

A2

|

Doctor explains to me WHY this medicine, and what should I DO

|

10

|

-12

|

-12

|

|

A4

|

Doctor guides me to the Internet sites… so I CAN TAKE CONTROL

|

10

|

-9

|

-12

|

|

B2

|

I don’t feel like going to the doctor… even for the most severe symptoms… I can take care of it

|

8

|

12

|

13

|

|

C3

|

I really am happy when someone takes control, and tells me what to take, and schedules my meds for me

|

5

|

9

|

6

|

|

B1

|

I’m pretty private about my health… no one’s business

|

4

|

9

|

4

|

|

C4

|

I’m pretty private… my health meds are my business… and maybe the doctor’s, but that’s all

|

-9

|

1

|

9

|

|

C1

|

My family is always there to listen, and support me… I like that

|

0

|

-8

|

8

|

|

A1

|

Doctor talks to me, face to face… not just those phone calls with clinical message

|

2

|

-14

|

-12

|

|

B3

|

When it comes to illness, I’m on Google, so I really become an expert

|

5

|

7

|

-2

|

|

B4

|

I’m nervous about health – but really want to be healthy to see my kids, grandkids, or even relatives and friends in the years to come

|

-2

|

-1

|

-1

|

|

C2

|

My family and others butt-in to my health… I want my privacy

|

2

|

6

|

7

|

|

D1

|

My family means the world to me

|

-4

|

-8

|

-7

|

|

D2

|

I reach out to talk to friends about my health and illness

|

2

|

-2

|

-6

|

|

D3

|

I reserve my friends for non-medical talks, like politics, or people

|

-3

|

3

|

1

|

Response Time (engagement) – Key Subgroups: Table 11 shows us the differences in response time across the 16 elements. The data are repeated for the total panel, along with the estimated response times for each element by each key subgroup. The patterns differ by subgroup. Some of the key results are:

- Males focus for longer times about being an expert and wanting privacy.

When it comes to illness, I’m on Google, so I really become an expert

I’m pretty private about my health… no one’s business

- Females focus slight longer about most of the elements than do males. Two elements capture their attention, but do not capture the attention of males

Doctor talks to me, face to face… not just those phone calls with clinical message

My friends explain this stuff to me… I’m more comfortable with them

- The youngest respondents (age 18–30) focus on only one element

My friends really are there to listen to me about my medical experience – sometimes I feel I’m wearing out my welcome

- The oldest respondents focus a lot more time than other respondents on the need for expertise and privacy

When it comes to illness, I’m on Google, so I really become an expert

I’m pretty private about my health… no one’s business

My family and others butt-in to my health… I want my privacy

- Those who say they are not concerned focus a great deal on one element

I don’t feel like going to the doctor… even for the most severe symptoms… I can take care of it

- Those who say they are healthy focus on

When it comes to illness, I’m on Google, so I really become an expert

I’m pretty private about my health… no one’s business

- Those say they are concerned about their health focus a great deal on two issues, opposites of each other

My family and others butt-in to my health… I want my privacy

I really am happy when someone takes control, and tells me what to take, and schedules my meds for me

- The privacy mind-set focuses on privacy, but also on the lack of privacy (someone else taking control). Keep in mind that this is response time, not a judgment. The respondents in this mind-set pay attention to the statement about someone else taking control, rather than just disregarding it.

When it comes to illness, I’m on Google, so I really become an expert

My family and others butt-in to my health… I want my privacy

I’m pretty private about my health… no one’s business

I really am happy when someone takes control, and tells me what to take, and schedules my meds for me

- The doctor mind-set actually spends more time on elements which do not agree with their mind-set and spend little time on elements dealing with the doctor. It is as if they are ‘wired’ to accept the information of the doctor but have to think about contravening data.

My friends explain this stuff to me… I’m more comfortable with them

When it comes to illness, I’m on Google, so I really become an expert

My family and others butt-in to my health… I want my privacy

- The control mind-set focus on loss of control, again spending little time on elements which agree with their mind-setI really am happy when someone takes control, and tells me what to take, and schedules my meds for me

Table 8. Performance of the answers/elements by key subgroup for the criterion of Works NO. Only strong performing elements for at least one subgroup are shown

|

|

Bot 2 – Works NO

|

Male

|

Female

|

Age 18–30

|

Age 31–49

|

Age 50+

|

Don’t think

|

Healthy

|

Concerned

|

|

Additive Constant

|

29

|

30

|

34

|

12

|

44

|

32

|

18

|

38

|

|

A3

|

My friends explain this stuff to me… I’m more comfortable with them

|

2

|

-1

|

-2

|

2

|

0

|

-9

|

10

|

-7

|

|

B1

|

I’m pretty private about my health… no one’s business

|

4

|

6

|

2

|

10

|

2

|

1

|

12

|

1

|

|

B2

|

I don’t feel like going to the doctor… even for the most severe symptoms… I can take care of it

|

13

|

9

|

2

|

15

|

13

|

-4

|

14

|

10

|

|

B3

|

When it comes to illness, I’m on Google, so I really become an expert

|

3

|

4

|

4

|

7

|

-1

|

-7

|

8

|

1

|

|

B4

|

I’m nervous about health – but really want to be healthy to see my kids, grandkids, or even relatives and friends in the years to come

|

1

|

-3

|

-9

|

6

|

-4

|

0

|

9

|

-10

|

|

C3

|

I really am happy when someone takes control, and tells me what to take, and schedules my meds for me

|

4

|

9

|

6

|

6

|

10

|

-7

|

9

|

5

|

|

D1

|

My family means the world to me

|

-4

|

-8

|

-16

|

2

|

-10

|

10

|

-8

|

-5

|

|

D2

|

I reach out to talk to friends about my health and illness

|

-4

|

1

|

-7

|

1

|

-1

|

13

|

-1

|

-2

|

Table 11. Response times for elements, by total panel and key subgroups

|

|

|

total

|

Male

|

Female

|

A18–30

|

A31–49

|

50+

|

Not concerned

|

Healthy

|

|

Concern

|

Doctor focus

|

Control focus

|

|

B3

|

When it comes to illness, I’m on Google, so I really become an expert

|

1.8

|

1.7

|

1.9

|

1.4

|

1.6

|

2.1

|

2.2

|

1.9

|

|

1.6

|

1.9

|

1.6

|

|

B1

|

I’m pretty private about my health… no one’s business

|

1.7

|

1.7

|

1.7

|

1.5

|

1.3

|

2.2

|

1.6

|

2.0

|

|

1.5

|

1.8

|

1.5

|

|

C2

|

My family and others butt-in to my health… I want my privacy

|

1.7

|

1.4

|

2.0

|

1.4

|

1.7

|

2.0

|

1.3

|

1.4

|

|

2.0

|

1.4

|

1.8

|

|

C3

|

I really am happy when someone takes control, and tells me what to take, and schedules my meds for me

|

1.7

|

1.5

|

1.8

|

1.0

|

1.8

|

1.9

|

1.6

|

1.2

|

|

2.0

|

1.4

|

1.9

|

|

B2

|

I don’t feel like going to the doctor… even for the most severe symptoms… I can take care of it

|

1.6

|

1.4

|

1.7

|

1.2

|

1.5

|

1.8

|

2.6

|

1.7

|

|

1.3

|

1.9

|

1.2

|

|

B4

|

I’m nervous about health – but really want to be healthy to see my kids, grandkids, or even relatives and friends in the years to come

|

1.6

|

1.6

|

1.6

|

1.4

|

1.6

|

1.6

|

1.5

|

1.5

|

|

1.6

|

1.8

|

1.4

|

|

C1

|

My family is always there to listen, and support me… I like that

|

1.5

|

1.5

|

1.5

|

1.1

|

1.4

|

1.8

|

1.8

|

1.1

|

|

1.9

|

1.3

|

1.7

|

|

D4

|

My friends really are there to listen to me about my medical experience – sometimes I feel I’m wearing out my welcome

|

1.5

|

1.5

|

1.6

|

1.9

|

1.0

|

1.9

|

2.0

|

1.2

|

|

1.8

|

1.8

|

1.3

|

|

A4

|

Doctor guides me to the Internet sites… so I CAN TAKE CONTROL

|

1.4

|

1.2

|

1.6

|

1.1

|

1.3

|

1.7

|

-0.3

|

1.4

|

|

1.6

|

1.5

|

1.3

|

|

C4

|

I’m pretty private… my health meds are my business… and maybe the doctor’s, but that’s all

|

1.4

|

1.3

|

1.5

|

1.0

|

1.3

|

1.8

|

1.1

|

1.0

|

|

1.8

|

1.2

|

1.3

|

|

D3

|

I reserve my friends for non-medical talks, like politics, or people

|

1.4

|

1.4

|

1.4

|

1.4

|

1.1

|

1.8

|

1.7

|

1.4

|

|

1.4

|

1.7

|

1.1

|

|

A1

|

Doctor talks to me, face to face… not just those phone calls with clinical message

|

1.3

|

1.0

|

1.6

|

0.9

|

1.1

|

1.8

|

-0.2

|

1.3

|

|

1.5

|

1.3

|

1.4

|

|

A3

|

My friends explain this stuff to me… I’m more comfortable with them

|

1.3

|

1.0

|

1.7

|

1.0

|

1.4

|

1.5

|

0.6

|

1.2

|

|

1.5

|

2.0

|

1.0

|

|

D1

|

My family means the world to me

|

1.3

|

1.6

|

0.9

|

1.5

|

0.9

|

1.6

|

1.9

|

1.2

|

|

1.3

|

1.6

|

1.3

|

|

A2

|

Doctor explains to me WHY this medicine, and what should I DO

|

1.2

|

1.0

|

1.4

|

1.1

|

1.1

|

1.6

|

0.6

|

1.0

|

|

1.5

|

1.4

|

1.3

|

|

D2

|

I reach out to talk to friends about my health and illness

|

1.1

|

0.9

|

1.3

|

1.4

|

0.7

|

1.3

|

0.3

|

1.1

|

|

1.1

|

1.4

|

1.0

|

Identifying Sample Mindsets at the Clinic

The conventional wisdom in consumer research is that we can use a person’s demographics or psychographics to predict the mind-set to which the person belongs. The actual practice is to cluster people based upon their demographics, attitudes and/or behavior, arriving at a set of individuals who LOOK different by standard measures, and then to map these clusters to different ways of thinking about the same problem.

The conventional approach occasionally works but fails to deal with the granularity of the situations having many aspects. The different aspects of a single topic, such as dealing with medical information, may generate a variety of different groups of mind-sets, depending upon the topic of medical information, whether that be simply informative, or prescriptive, and forth. Conventional research is simply too blunt an instrument to assign people to these different arrays of mind-sets, each of which emerges from different aspects of the same general problem. Once granularity becomes a factor in one’s knowledge, the standard methods no longer work, in light of the vastly increased sophistication of one’s knowledge about a topic.

An example of the difficulty of traditional methods to assign new people to the three mind-sets uncovered here can be sensed from Table 12, which shows the membership pattern in the three mind-sets by gender, by age, and by self-described concern with one’s health. The distributions are similar across the three mind-sets. One either needs much more data, from many other measured aspects of each person, or a different way to establish mind-set membership in this newly uncovered array of three mind-sets emerging from the granular topic of the way one wants to give and get medical information.

Table 12. Distribution of mind-set membership by gender, age, and self-described concern with one’s health

|

|

Privacy focus

|

Doctor focus

|

Control focus

|

|

Total

|

100

|

38

|

29

|

33

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Male

|

51

|

18

|

16

|

17

|

|

Female

|

49

|

20

|

13

|

16

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Age 18–30

|

21

|

11

|

5

|

5

|

|

Age w

|

39

|

14

|

12

|

13

|

|

Age 50+

|

37

|

12

|

11

|

14

|

|

Not answered

|

3

|

1

|

1

|

1

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Healthy

|

44

|

20

|

12

|

12

|

|

Concerned

|

49

|

17

|

13

|

19

|

|

Never think about it

|

7

|

1

|

4

|

2

|

Discovering these three mind-sets in the population by a PVI (Personal Viewpoint Identifier)

The ideal situation in research is to discover a grouping of consumers, e.g., our three mind-sets, and then discover some easy-to-measure set of variables which, in concert, assign a person to a mind-set. With such an assignment rule it may be possible to scan a database of millions of people, and assign each person in the database to one of the empirically discovered mind-sets. That process may work, but the occasions are few and far between.

An alternative method uses the coefficients from the three mind-sets to create a typing tool, a set of questions with simple answers, so that the pattern of answers assigns a person to one of the three mind-sets. The method uses the coefficients for Works YES (Table 9), identifies the most discriminating patterns, and then simulates many thousands of data sets, perturbing each data set thousands of times. These data sets are, for each mind-set, the 16 coefficients and the additive constant. The process is a so-called Monte-Carlo simulation.

The actual PVI is available at the link below, as of this writing (summer, 2019).

http://pvi360.com/TypingToolPage.aspx?projectid=78&userid= 2018

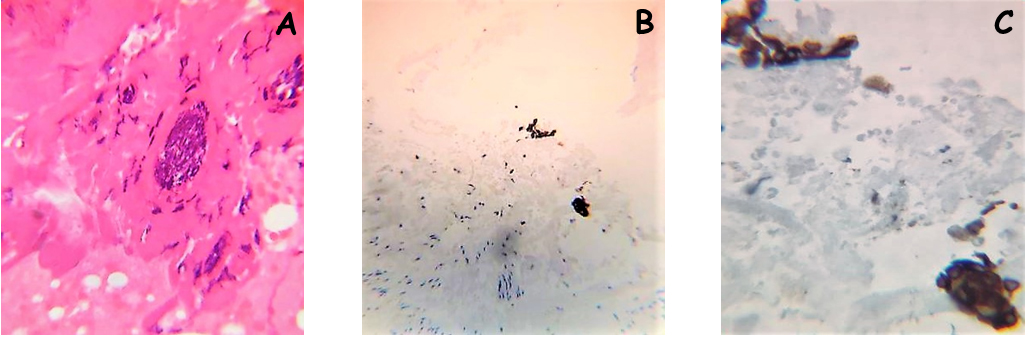

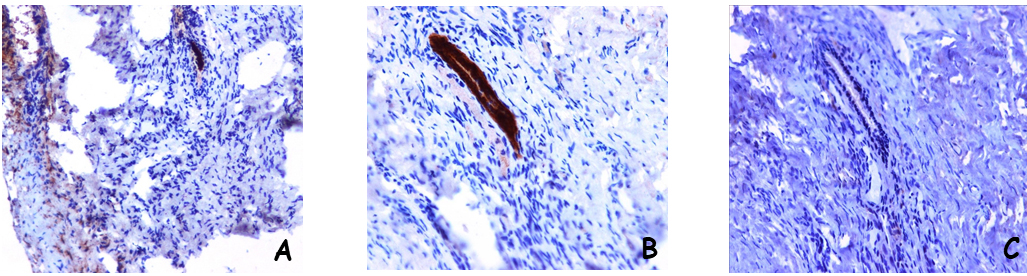

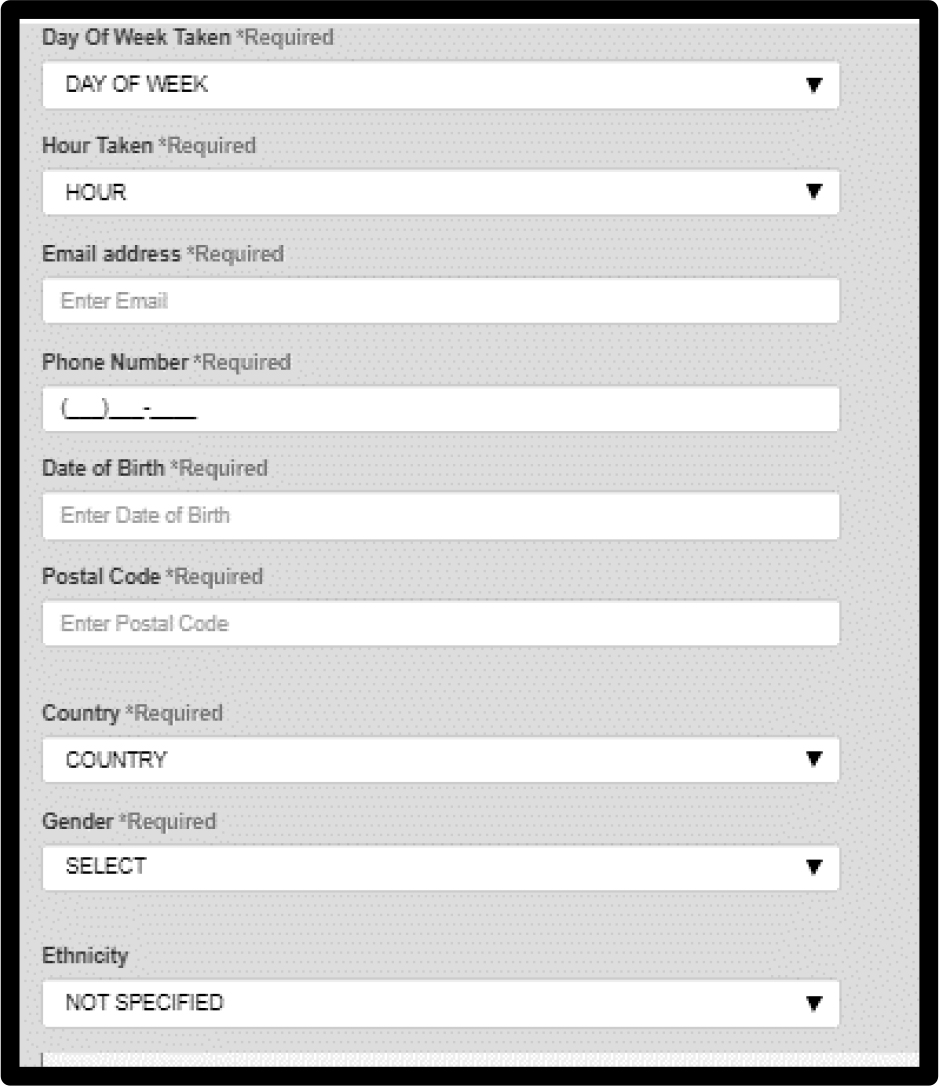

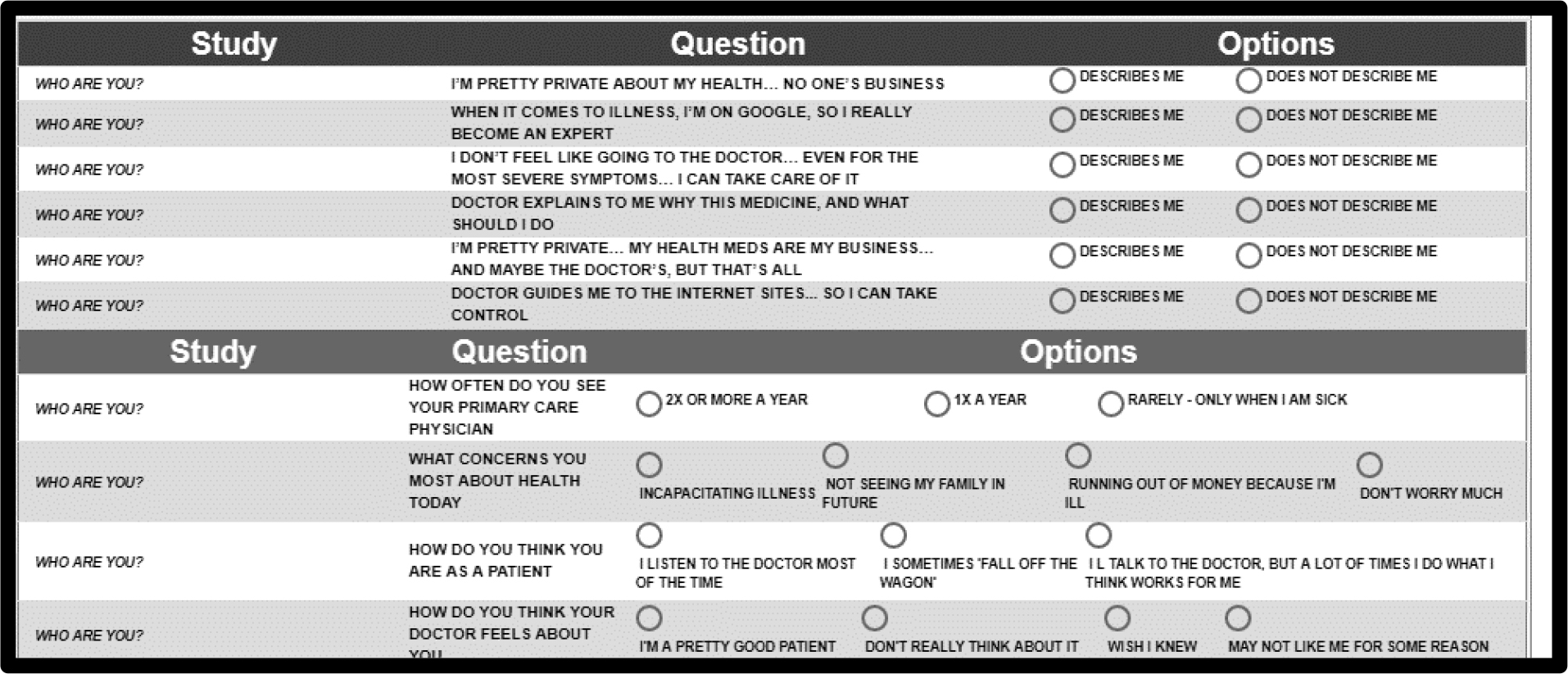

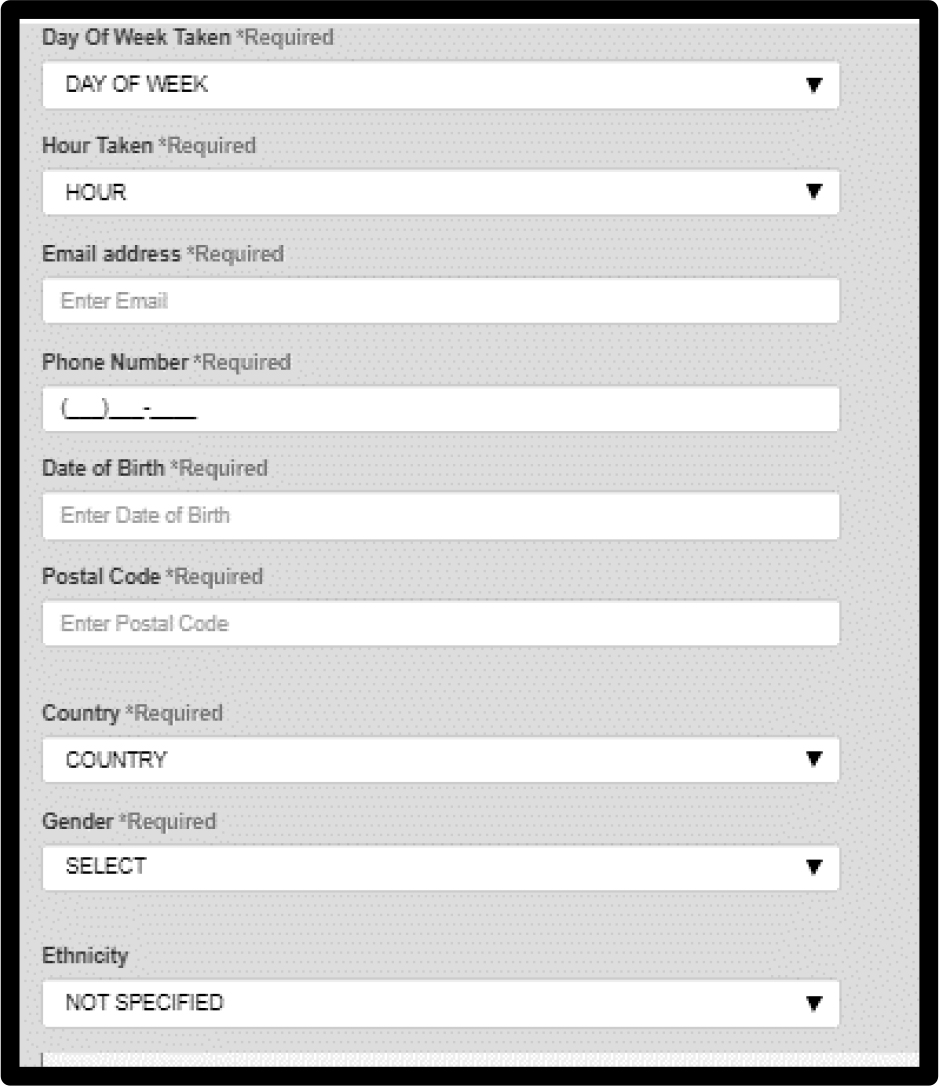

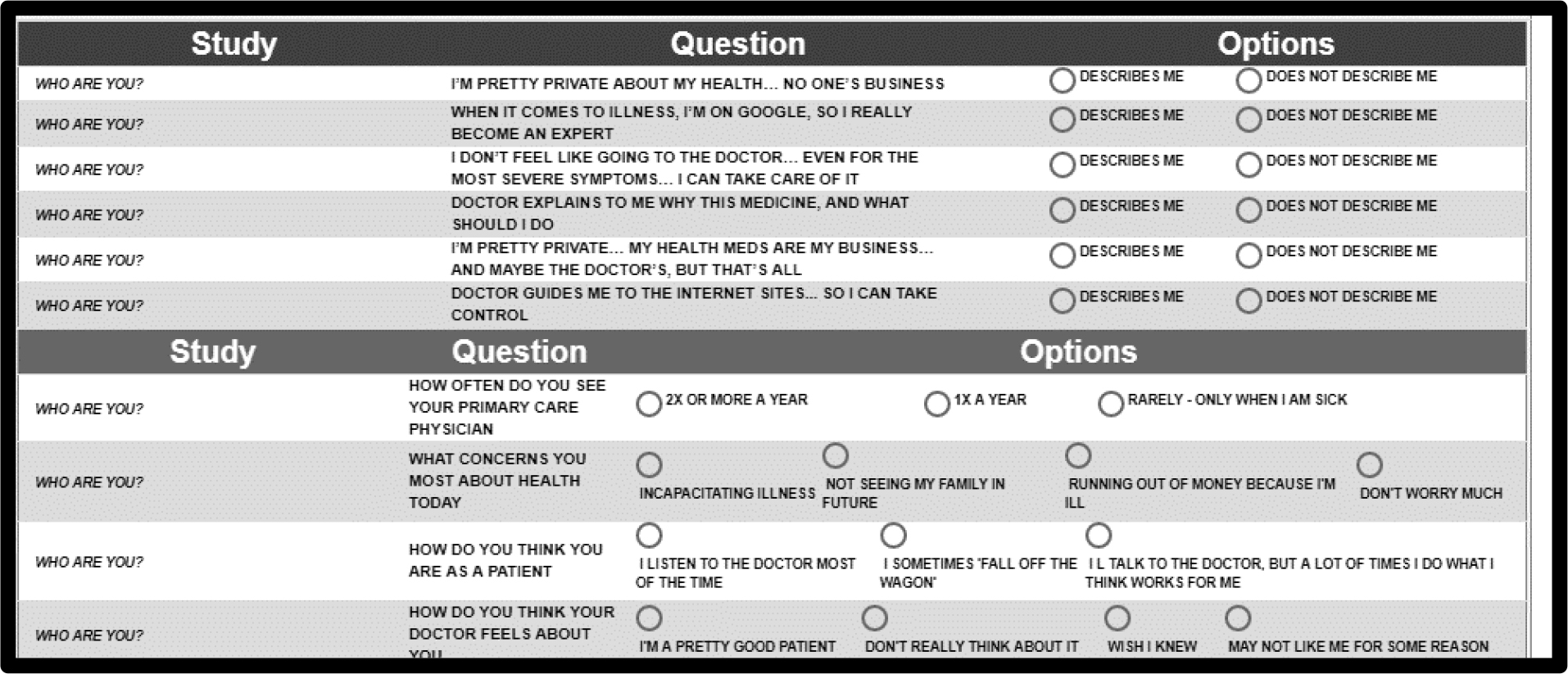

Figure 1 shows the information collected from the respondent (classification), and Figure 2 shows the actual PVI questions. In practice they are randomized. Following the six questions, the patterns of answers to which assign a person to a mind-set, we see four additional questions that the respondent who is doing the typing can answer, to provide additional information.

Figure 1. The self-classification, completed at the start of the PVI

Figure 2. The actual PVI showing the six PVI questions, and the four general questions below

Figure 2. The actual PVI showing the six PVI questions, and the four general questions below

Discussion and conclusions

This study identified mindsets regarding how the person would like to communicate with the physician the underlying goal being to increase adherence through proper communication. Communication messaging typically involves identifying a subgroup by common characteristics of its members and according the information to group members by these characteristics (Kreuter, Strecher& Glassman, 1999). The notion underlying this approach is that group members possess similar characteristics and, therefore, will be influenced by the same message. Similarly, in health communication, messaging may be customized to a subgroup, members of which share characteristics such as illness, health conditions and needs, etc. Individuals, however, are most persuaded by personally relevant communication and are more likely to pay attention and to process such information more thoroughly (Petty &Cacioppo, 2012).

Since fitting a message to meet personal needs of patients, rather than group criteria, is more effective for influencing attitudes and health behaviors, we suggest that to promote adherence, clinicians should tailor their messages to individuals. Sophisticated approaches to tailor communication aimed at changing complex health behaviors such as adherence, call upon clinicians to integrate detailed information into communication messages for each patient (Cantor &Kihlstrom, 2000).An advantage of such strategies for communication is that messages tailored to a patient do not need to be modified very often (Schmid, Rivers, Latimer &Salovey, 2008).

Our viewpoint enables clinicians to identify the sample mindset to which a patient in the population belongs, for a specific topic, i.e., granular. Messages about adherence and non-adherence should be congruent with those specifically strong elements for the mind-set to which the patient belongs for the particular topic. There are some messages which appear to be universal, such as the need of patients to have eye contact with the clinician. At the deeper level, the level of granular message; the data suggests three mind-sets, membership in which should be known to the physician and guide style of communication.

People belonging to the first mindset focus on privacy and expect their clinician to take control (e.g., tell me what to take, schedules my meds for me).

People belonging to the second mindset accept what the clinician advises them but spend time discussing it with other patients and enhancing their knowledge on Google. People in this mindset expect their clinician to carry a dialogue respecting the information they learned and their thoughts.

People belonging to the third mindset, need to have control. Aiming at behavioral changes and adherence promotion, clinicians might adopt communication with a tonality of process oriented, along with personal relevance for the patient.

Tailoring the message to the patient requires the clinician to assess each patient belonging to a mindset by asking the six questions according to our viewpoint identifier.

Acknowledgement

Attila Gere thanks the support of the Premium Postdoctoral Researcher Program of the Hungarian Academy of Sciences

References

- DiMatteo MR (2004) Variations in patients’ adherence to medical recommendations: a quantitative review of 50 years of research. MedicalCare 42: 200–209.

- Haskard-Zolnierek KB, DiMatteo MR (2009) Physician communication and patient adherence to treatment: a meta-analysis. Medical care 47: 826.

- Vermeire E, Hearnshaw H, Van Royen P (2001) Patient adherence to treatment: three decades of research, a comprehensive review. J Clin Pharm Ther26: 331–342.

- Zolnierek KB, DiMatteo MR(2009) Physician communication and patient adherence to treatment: a meta-analysis. Medical care 47: 826.]

- DiMatteo MR, Haskard KB, Williams SL (2007) Health beliefs, disease severity, and patient adherence: a meta-analysis. Medical Care45: 521–528.

- Sabate E (2003) Adherence to long-term therapies: Evidence for action. Geneva: World Health Organization.

- Gabay G, Moskowitz HR (2012)the algebra of health concerns: implications of consumer perception of health loss, illness and the breakdown of the health system on anxiety. International Journal of Consumer Studies36: 635–646.

- Gabay G (2015) Perceived control over health, communication and patient- physician trust. Patient Education and Counseling98: 1550–1557.

- Beck RS, Daughtridge R, Sloane PD (2002) Physician-patient communication in the primary care office: a systematic review. Journal of the American Board of Family Practice15: 25–38.

- Gabay G (2016) Exploring perceived control and self-rated health in re-admissions among younger adults: A retrospective Study. Patient Education and Counseling 99: 800–806.

- Osterberg L, Blaschke T (2005) Adherence to medication. N Engl J Med 353: 487–497.

- Chewning B, Sleath B (1996) Medication decision-making and management: a client-centered model. SocSci Med 42: 389–398.

- Squier RW (1990) A model of empathic understanding and adherence to treatment regimens in practitioner-patient relationships. SocSci Med 30: 325–339.

- Stewart MA (1984) what is a successful doctor-patient interview? A study of interactions and outcomes. SocSci Med 19: 67–175.

- DiMatteo MR, Haskard-Zolnierek KB, Martin LR (2012) Improving patient adherence: a three-factor model to guide practice. Health Psychology Review 1: 74–91.

- Haynes RB, Yao X, Degani A, Kripalani S, Garg A, et al.(2005) Interventions to enhance medication adherence. Cochrane Database Systematic Review 4

- Haynes R, Ackloo E, Sahota N, McDonald H, Yao X (2008) Interventions for enhancing medication adherence. Cochrane Database of Systematic Review 2: CD000011.

- Ratanawongsa N, Karter AJ, Parker MM, Lyles CR, Heisler M, et al. (2013Communication and medication refill adherence: the Diabetes Study of Northern California. JAMA internal medicine11: 173–210.

- Rosenthal R, Rosnow R (2007) Essentials of behavioral research: methods and data analysis. McGraw-Hill.

- Levinson W, Lesser CS, Epstein RM (2010) Developing physician communication skills for patient-centered care. Health affairs29: 1308–1310.

- Epstein RM, Street RL (2007) Patient-centered communication in cancer care: promoting healing and reducing suffering. National Cancer Institute.

- Brown RF, Butow PN, Dunn SM, Tattersall MH (2001) Promoting patient participation and shortening cancer consultations: a randomised trial. British Journal of Cancer 85: 1273.

- Tulsky JA (2005) Interventions to enhance communication among patients, providers, and families. Journal of palliative medicine 8: 95.

- Rao JK, Anderson LA, Inui TS (2007) Communication interventions make a difference in conversations between physicians and patients: a systematic review of the evidence. Med Care45: 340–349.

- Gabay G, Zemel G, Gere A, Zemel R, Papajorgji P, et al. (2018) On the threshold: What concerns healthy people about the prospect of cancer.Cancer Studies and Therapeutics Journal 3: 1–10.