DOI: 10.31038/AWHC.2019246

Abstract

National indices of maternal health have improved in Bangladesh, but no data is available from rural Mymensingh where two non-government aid agencies have been working for years. Surveys were held to inform their planning.

Methods: In November 2018, aided by a research team from Western Sydney University, Australia, anthropometric, mortality and socioeconomic data was compiled from 25 sites around Haluaghat and Dhobaura, and compared with national figures.

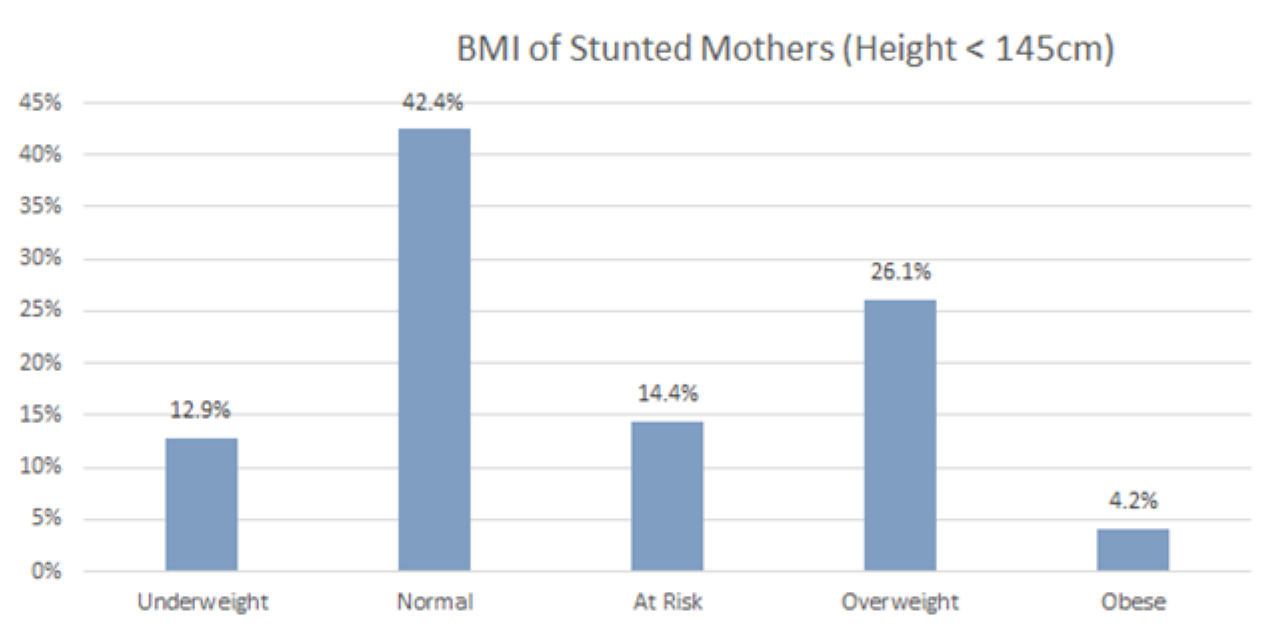

Results: Of 1982 mothers surveyed: 15.5% were ‘stunted’(<145 cm) vs 15.7% in Sylhet, and 13.3% in Dhaka, correlating with poverty, reduced education, and stunting of offspring. 13% were underweight (BMI <18.5 kg/m2) vs 29.8% in Sylhet and 18.2% in Dhaka. Conversely, overweight was common. Of stunted mothers 14.4% were ‘at risk’, 26.1% overweight and 4.2% obese. 29.7% consumed betel nut. Stillbirth, Perinatal, Neonatal and Child Mortality rates were very high: 89.8, 108.8, 27.45, and 61.3 respectively. 63.5% of births occurred at home with untrained assistance. 33.2% of mothers were married < 16 years, and suffered higher Neonatal and Child Mortality Rates.

Conclusion: Rates of undernutrition and child mortality are very high. The dyad of stunting and obesity portends the metabolic syndrome.

Key words

Child Mortality Rates, Dyad of Stunting and Obesity, Home Births, Maternal Health, Stunting, Underage Marriage, Underweigth

Introduction

Although the maternal mortality rate in Bangladesh declined significantly from 322 per 100,000 live births in 1998–2001 to 194 in 2007–2010, it stalled at that level in 2016, despite an increase in deliveries attended by medically trained personnel and an increase in a continuum of care from before to after the birth. The reasons for this stalling are not clear, but the Bangladesh Maternal Morbidity Survey (BMMS) regrets ‘the quality of health care is generally poor in Bangladesh’ and ‘most facilities…are not fully ready to provide quality maternity care [1].

In a similar period, however, maternal nutrition is reported to have improved. The national rate of Body Mass Indices (BMI) <18.5 fell from 34 to 19% from 2004 to 2014, though 31% of ‘ever married women age 15–19’ were ‘undernourished’ with BMI <18.5 in 2014 [2].

Bangladesh Demographic and Health Surveys (BDHS) report periodically on Maternal and Newborn Health, and on Nutrition of Children and Women. They present data from representative sites throughout Bangladesh, but these have not included the rural region in the north of Mymensingh District where, for many years, two non-government organisations, Symbiosis International and the Mennonite Central Committee, have sought to improve women’s and children’s health. To review progress and assist planning, a survey was undertaken in November 2018 of indices of maternal and child health in 25 sites in an around the region of activity of the NGOs. The aim was to capture a ‘moment in time’ of major anthropometric data, clinical and historical status and social correlates of health, and to compare the findings with national data as found in BDHS. This report will concentrate on aspects of maternal health. Other reports will concentrate on children. The surveyed sites are on flat agricultural land along the border with India, with two commercial and administrative centres: Haluaghat and Dhobaura. Local roads are of poor quality, particularly in the rainy season, and transportation of women to the main birthing centre in Joyramkura Hospital may be delayed. Rice is the staple crop and most villagers are involved in agricultural labour. Ethnicity is predominantly Bengladeshi with a Garo minority.

Methods

The surveys were organised by two non-government aid organisations, Symbiosis International and Mennonite Central Committee, with assistance of a research group of senior medical students and supervisors associated with the School of Paediatrics, Western Sydney University, Australia. In preliminary visits to the villages, the aims and the process of the surveys were explained and participation invited. Surveyors were divided into two teams, each visiting one village a day where a line of ‘booths’ were established, first, to elicit historical data from the mother on her age, age at marriage, numbers of still and live births, numbers of childhood deaths, ages of children, participation in programmes of vaccination and worming, and social correlates including mothers’ education and family income, sanitation, and water supply. Then, heights and weights of the mothers and lightly dressed children were measured, and children were examined physically. Information regarding maternal deaths was not sought. Data was recorded on paper and later transcribed into a computer for analysis.

All participants did so voluntarily. Information was encoded by numbers but a master list was kept, in confidence, in case health reasons mandated subsequent contact. Maternal stunting was defined as height <145 cm. Maternal ‘underweight’ was defined as Body Mass Index (BMI) <18.5 Kg/m2. A BMI from 18.6 and 22.9 Kg/m2 was defined as normal: from 23–24.9 as ‘at risk for overweight’; from 25–29.9 Kg/m2 as ‘overweight’ and >30 Kg/m2 as obese [3]. Maternal anthropometry was compared with data contained in Bangladesh Maternal Morbidity Surveys (BMMS) and BDHS reports. Family income was graded into four categories: Band 1 had a monthly income of <5000 Taka; Band 2 between 5001–10,000; Band 3 between 10,001–15000 and Band 4 had>15,000. (US $1 = 84 Taka) Sanitation was categorised into open and closed latrines with the former discharging untreated effluent upon surrounding ground or water.

The Stillbirth Rate (SBR) was defined as the rate of deaths in utero after 28 weeks of gestation: The Perinatal Mortality Rate (PMR) as the number of Stillbirths plus deaths in the first week of life per 1000 total births; The Neonatal Mortality Rate (NMR) as the number of deaths in the first 28 days of life per 1,000 live births:; the Infant Mortality Rate (IMR) as the number of deaths in the first year of life per 1,000 live births; the Child Mortality Rate (CMR) as the number of deaths < 5 years of age per 1000 live births. Ethnicity was denoted by the mother: Bangladeshi or Garo.

Statistics

Data was cleansed and imported into a relational database enabling cross correlating queries to be executed. WHO anthropometric factors of Height vs Age (HAZ), Weight vs Age (WAZ), Weight vs Height (WHZ) were calculated using the WHO published mathematical algorithms.[1]

Outliers were identified according to WHO statements of limits and discarded as per WHO stated process. Data was converted to Z Scores and expressed as the standard deviation (SD) from the mean of the WHO reference standard population for both male and female.[2]

Continuous unpaired data was analysed using zTest,. Count data was analysed using Chi-Squared Best Fit assuming equal proportions and trend data analysed using Chi-Squared Tend Analysis. Correlations were performed using Pearson’s correlation. In all tests sample size was > 30 and the null hypothesis rejected for results > 95% confidence, resultant P-Values are reported. We perform all comparisons against the combined male-female scores, unless otherwise stated. We used Minitab Express for all statistical analysis.

Ethics

The surveys were approved by governance of both Symbiosis International and Mennonite Central Committees as quality assurance of current programmes and preparation for future activity. Representatives of those NGOs visited the sites in advance, explained the aims and the process, and invited participation. Mothers and their children attended voluntarily. Data was de-identified for analysis but a list was kept in confidence in case of need to contact the parents eg with regard to medical concerns.

Results

In the 25 sites, 1982 mothers were interviewed and measured, and 2987 children were measured and examined.

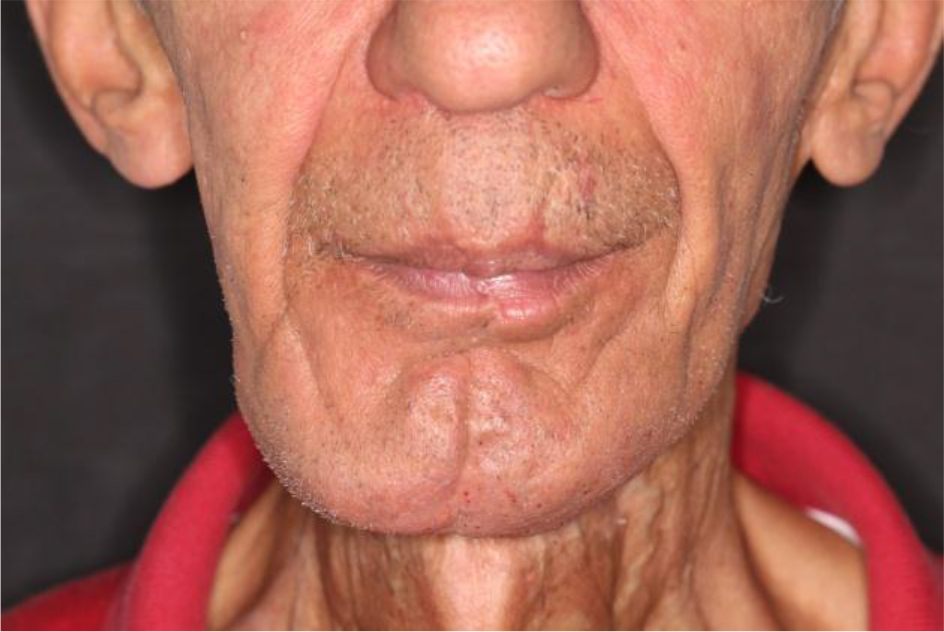

- Maternal Anthropometry

Overall, 15.4% of mothers in northern Mymensingh were ‘stunted’, with height <145 cm, similar to the rate of 15.7% in rural Sylhet, the highest in the country, and greater than the 13.3% in Dhaka [2]. The overall rate in northern Mymensingh has stalled near the national rate of 16% reported in BDHS 2004, but the rate is rising within families. Of the 15.4% of stunted mothers, the rate in their children aged from 5–14 years increased to 25.6% and in those <5 years to 36.2%.

Maternal stunting was greatest in the lowest Income Band (18.0%) from which it remained around 13% through higher Bands. These rates are worse than reported nationally in both the lowest (16%) and highest Income Bands (9%) [2]. Maternal stunting was associated with adverse outcome in offspring. First, it was strongly associated with stunting in the offspring: 47.9% compared to 33.2% from non-stunted mothers (PValue 0.0007). This effect was significant for female children (PValue 0.0013), but weaker for male children (PValue 0.1053). Second, the <5 CMR was increased in stunted mothers (74.0 vs 57.1 per 1,000, (PValue 0.0183). The CMR was higher in stunted mothers who were also overweight and obese (130.4 vs 64.4) compared with stunted mothers who were not (PValue 0.00394).

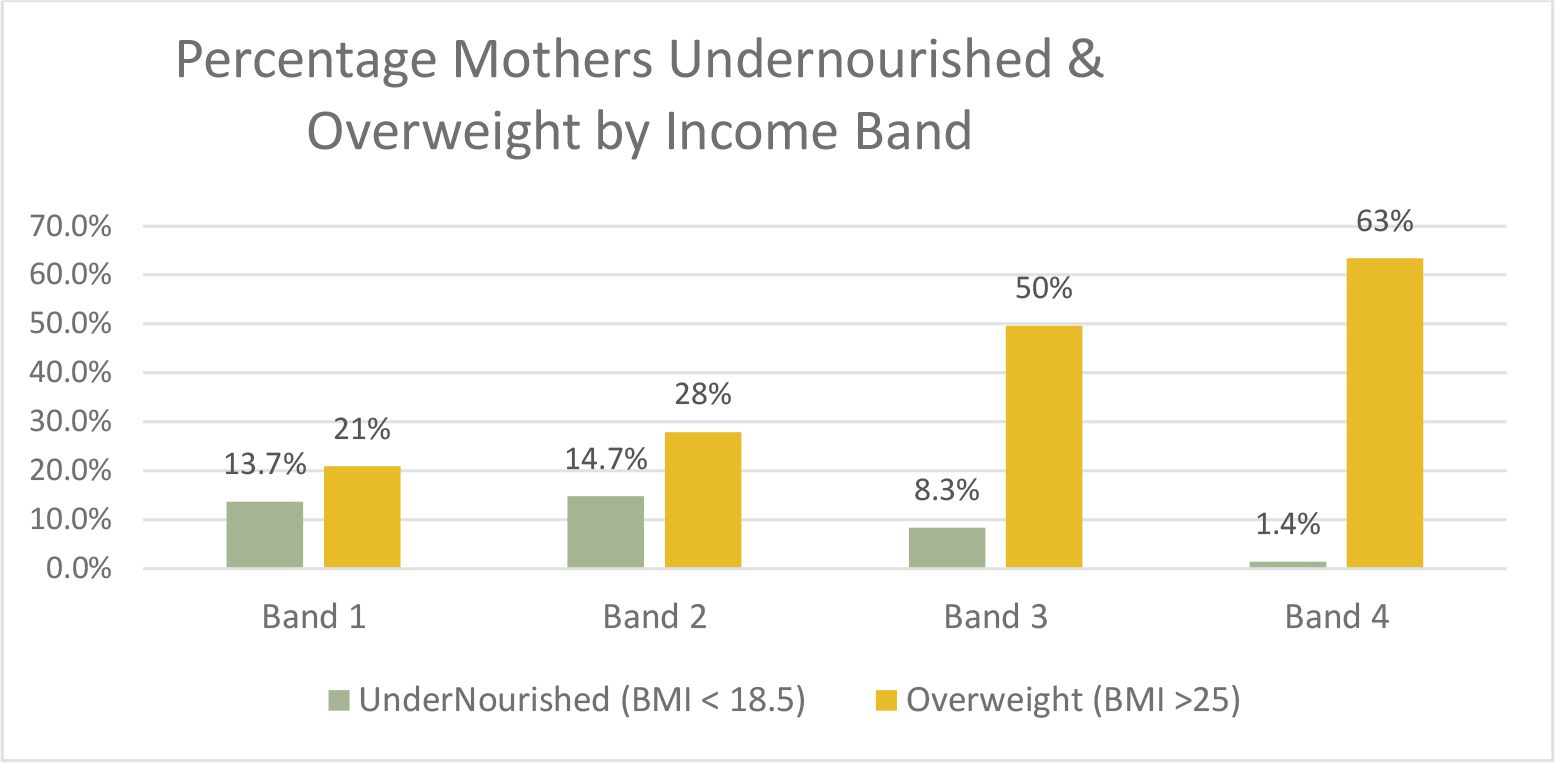

As well as stunting, maternal underweight was common (12.7%), though less than in rural Sylhet (29.8%) and Dhaka. (18.2%) [2]. The rate decreased with rising income. Contemporaneous with maternal underweight in northern Mymensingh is a high rate of overweight: 23.7% of women had BMI> 25 kg/m2 and 5.6% a BMI >30 kg/m2, similar to those of Chittagong (27 and 5.6%), reported as the highest in the nation [2].

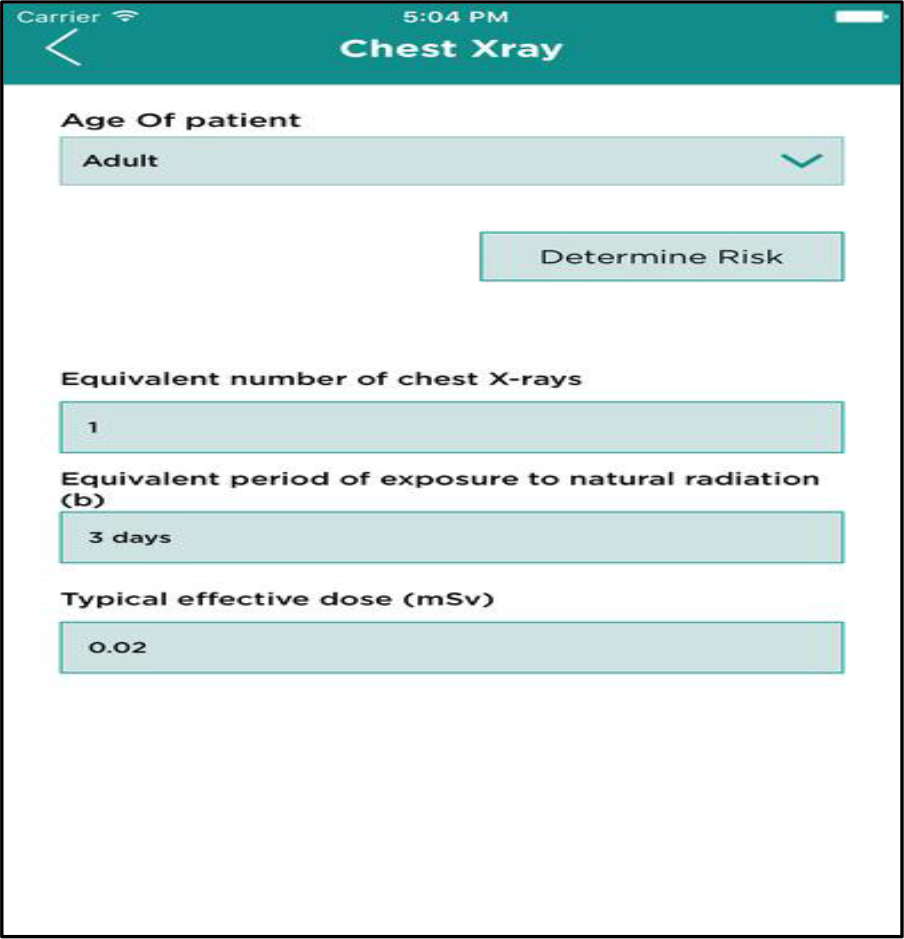

Overall, the rates of maternal underweight decreased and the rates of overweight increased through rising Income Bands. See Figure 1. In all 25 sites, there were both underweight and overweight mothers. In 16 villages, more than 20% of mothers were overweight: in six, more than 40% were overweight.

Figure 1. Bar graph revealing decreasing rates of underweight and increasing rates of overweight through increasing Income Bands.

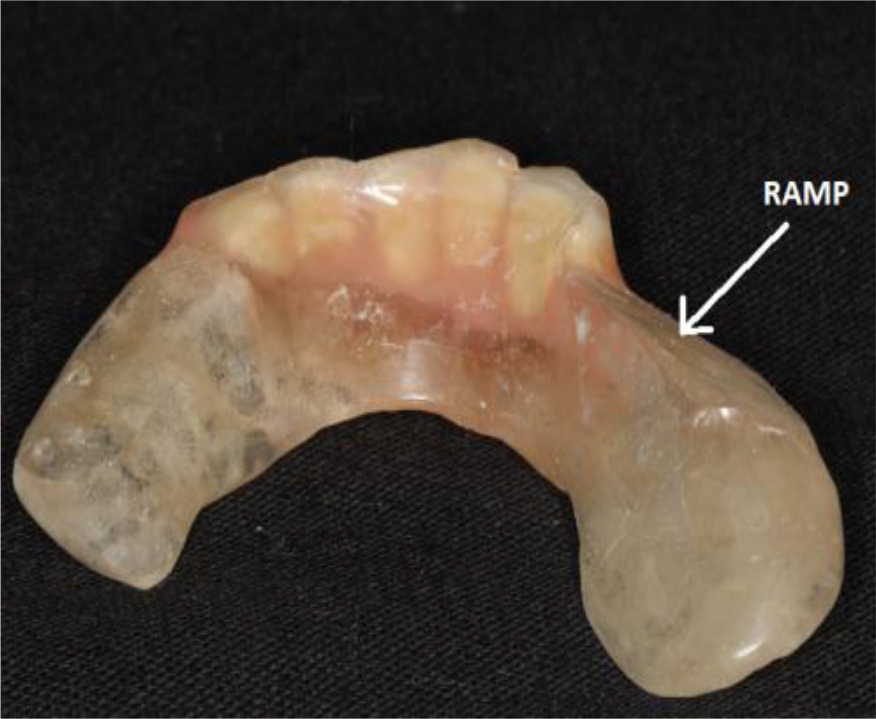

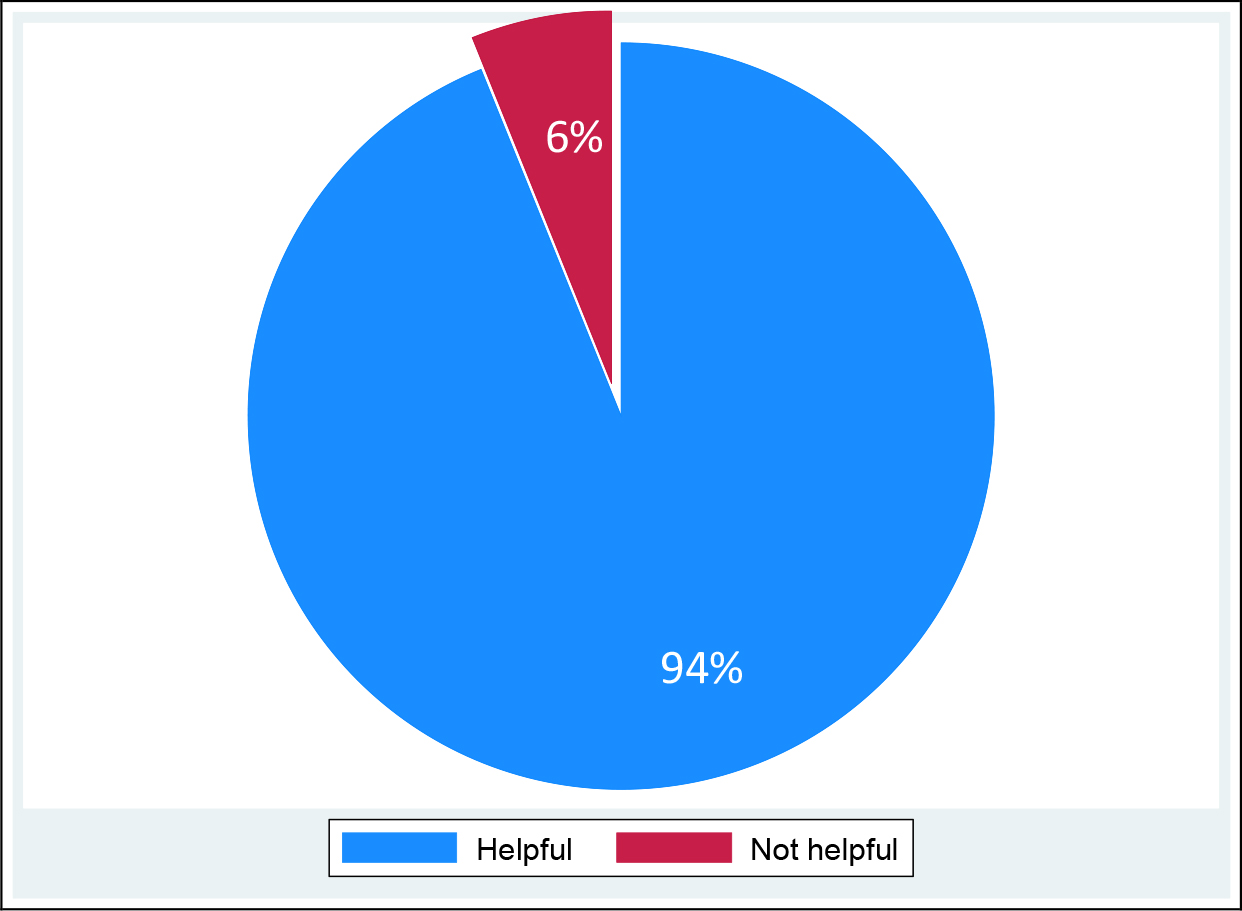

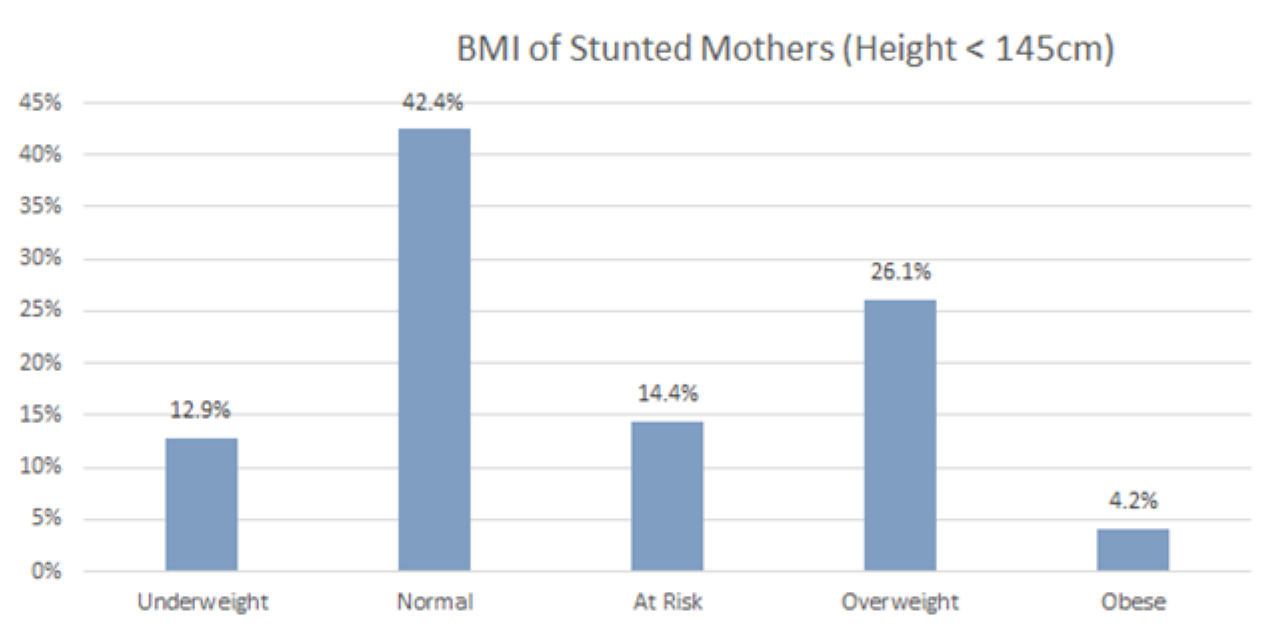

Many stunted mothers were overweight: though 12.9% were also underweight and 42.4% were appropriately weighted, 14.4% are ‘at risk’ of overweight, 26.1% were overweight and 4.2% obese Figure 2.

Figure 2. Bar graph revealing high rate of association between stunting and overweight.

- Mothers’ fertility and income: The numbers of live births fell progressively through the income bands, from a mean of 2.63 per mother in the lowest to 1.97 in the highest.

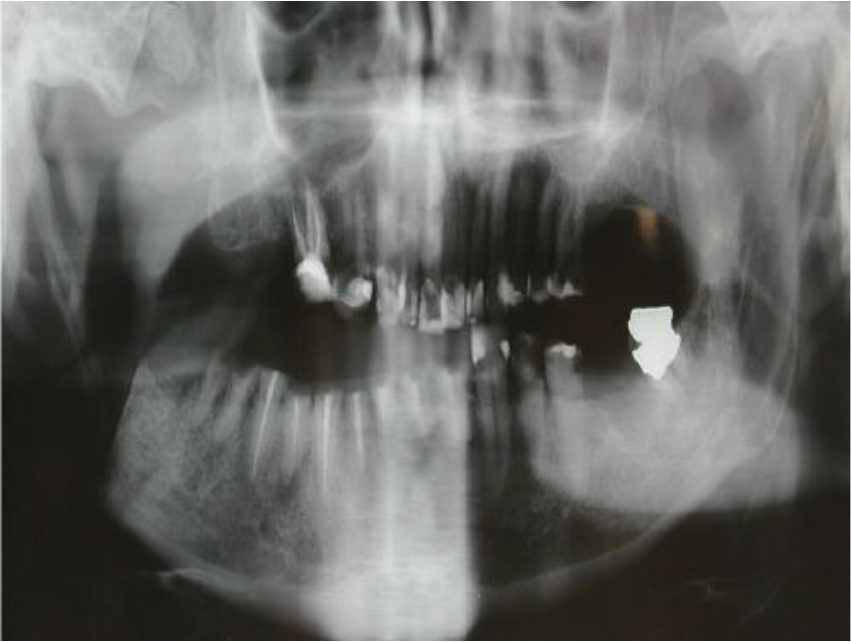

- Child Mortality rates: The mothers reported 435 still and 4408 live births, of whom 275 children had died: 93 in the first week of life, 122 within the first month, giving an SBR of 89.8, a PMR of 109.0, an NMR of 27.7, and an <5 CMR of 62.4. The SBR in northern Mymensingh is almost four times higher than the national rate (89.8 vs 20.4) [4]4, and over twice that of the hitherto highest, Sylhet, (89.8 vs 36.3) [5]. PMR is over twice the national rate (109.0 vs 44), while NMR (27.7 vs 28) is comparable, and CMR is much higher (62.4 vs 46) [2].

- Site of birth: 63.2% of surveyed births occurred at home, revealing no improvement from the national rate of 63% reported in 2014 [2]. Overall, 56.3% occurred under the care of a family member or traditional birth attendant. Attendance by a ‘professional’ increased through the income bands from 37% in the lowest to 72% in the highest.

Breast Feeding

Overall, 96.9% of mothers initiated breastfeeding immediately after birth. Of those who did not, 47.8% were clustered in 3 of the poorest sites. The offspring of the mothers who did not breast feed immediately after birth were significantly more stunted (p-value 0.0304). Across all incomes, 14.1% of mothers breast fed for < 6 months, or not at all. Overall, 81% of mothers in the higher income Bands ceased feeding in the sixth or seventh month, compared with 11% in the lowest income Band. Most notably, 51% of mothers in Band 1 continued to feed beyond 12 months, with a large proportion (32%) continuing beyond 2 years. This conflicts sharply with the length of breastfeeding in all higher Bands in which only 6% continued beyond 1 year, and 3% beyond 2 years. In all income bands, the rate of breastfeeding was higher in Garo mothers (p-value 0.0001). Children in Income Band 1 who were breast fed for longer than 6 months were more stunted (PValue 0.0048) than those who were not. This association between prolonged breast feeding and stunting was not, however, observed in higher Income Bands.

Latrines

44.6% of families used an ‘open latrine’ compared with the national rate of 36%2. Their use was strongly associated with the lowest Income Band, and thus correlated with stunting of both mothers and children. Controlling for income within that Band, the rate of childhood stunting was much greater in families with open rather than sanitary latrines (40.8 vs 27%. P Value 0.0227). The effect was not seen in Band 2 and the number of open latrines sampled in Band 3 and 4 was too low for meaningful analysis.

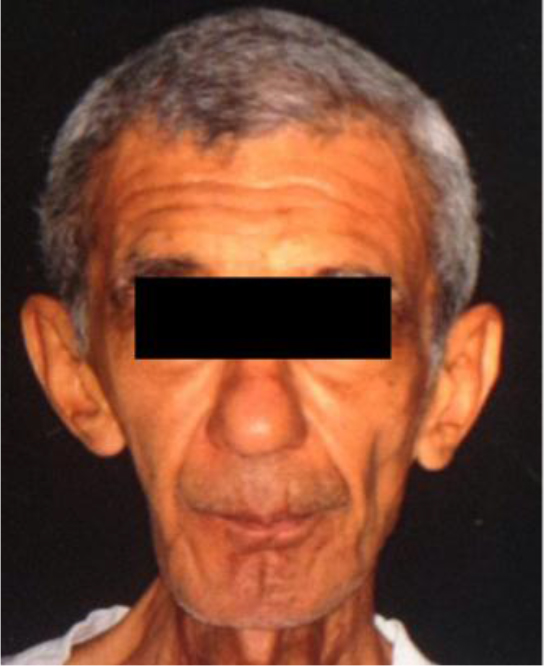

Underage marriage of females

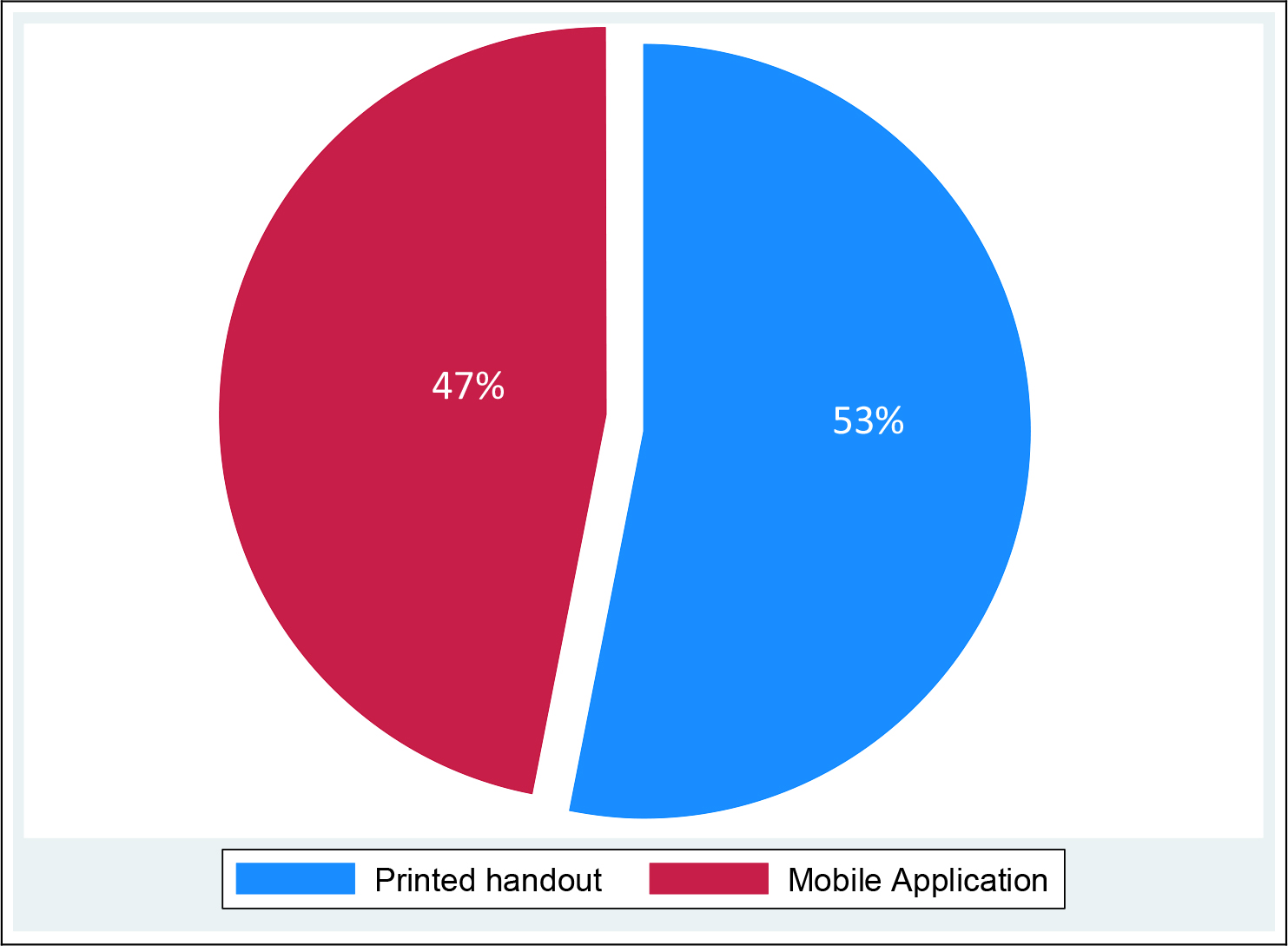

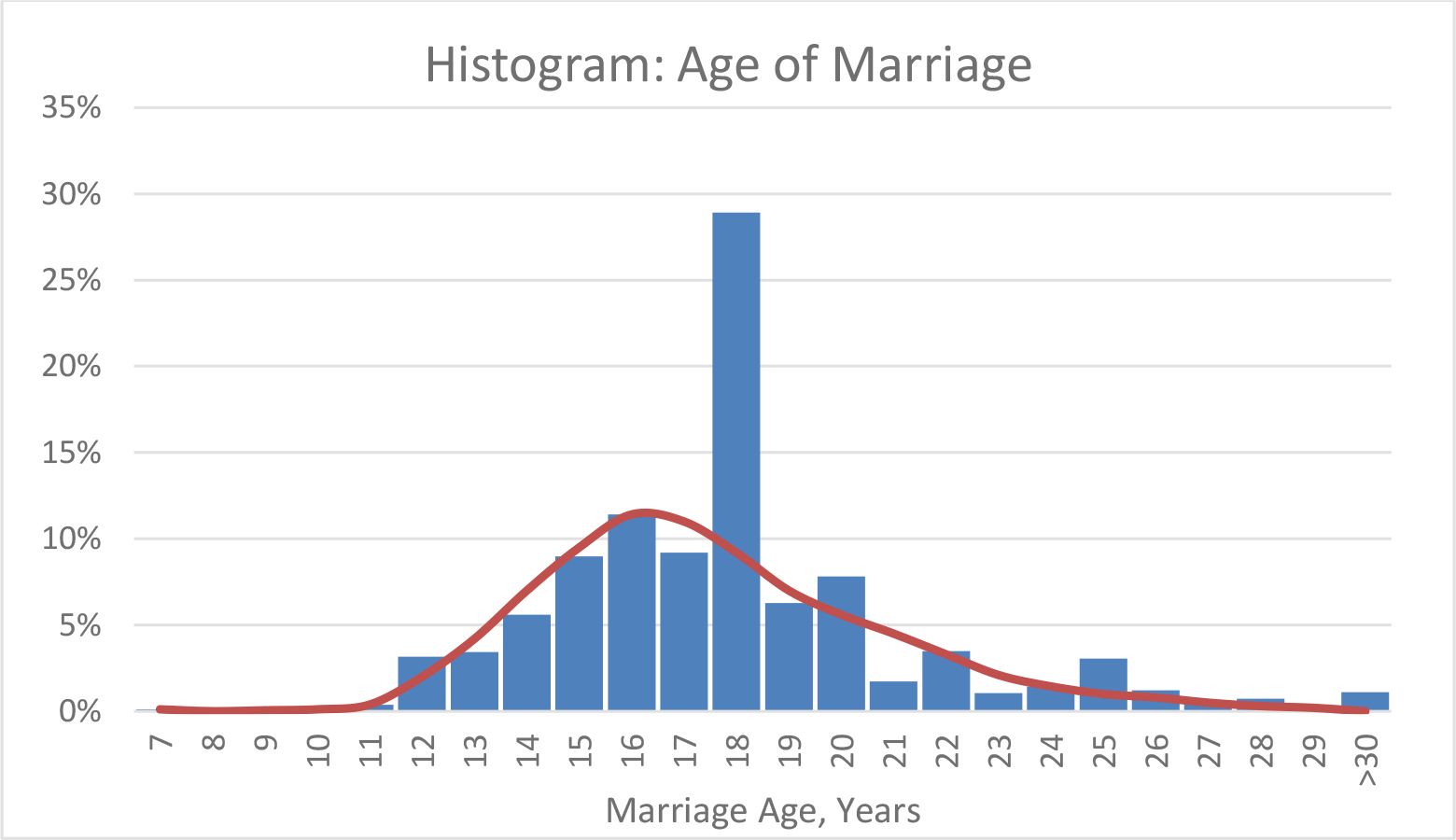

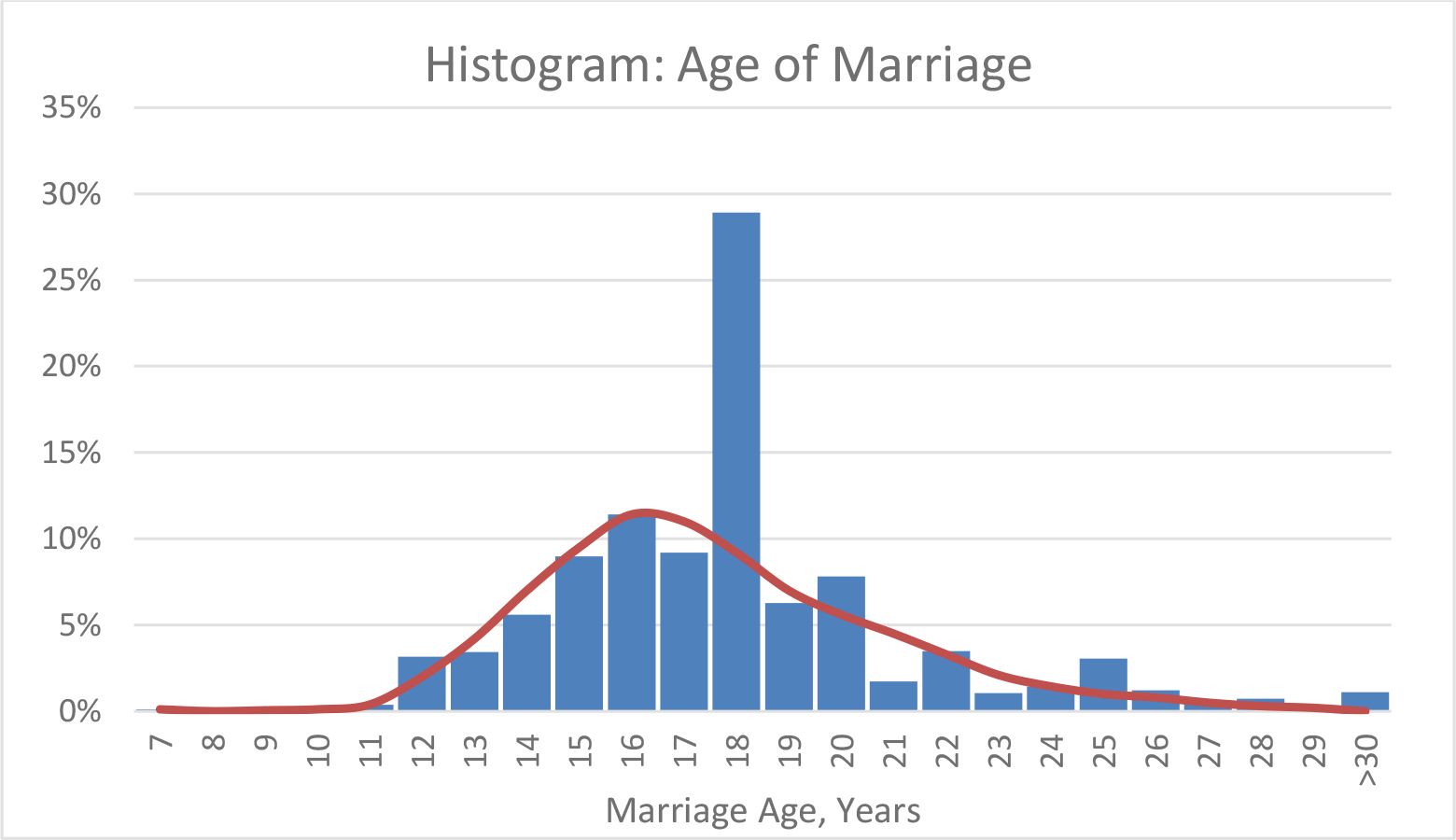

The mean reported age of marriage was 17.92 (SDev 3.48, n 1816). Overall, 42.5% were married <18 years, with 33.2% at or below 16 years, of whom 38.0% were Bangladeshi compared with 9.5% Garo. Bangladeshi youths are 3.98 times more likely to be married < 16 years than Garos. The youngest bride was 7. The percentage of child brides differed markedly by village, from 79% to 23%, with prevalence inversely correlating with household income (Pearson’s correlation = -0.17017, PValue <0.0001). Though BDHS 2014 reported 71% of girls were married <18 years, it claimed a substantial, and accelerating decrease in underage marriage in recent years. Our overall rate of 42.5%, together with a mean age of 17.92 and median of 18 years, might reflect that decline, but our data is skewed to a younger age, with an exceptional, outlying rate at exactly 18 years which may be misleading. See Figure 3.

Figure 3. Histogram of ages of marriage, revealing a curve skewed to the left and a marked outlier at 18 years.

Overall, the proportion of younger age marriage was higher in families with the lowest income but, even within the income Bands, underage marriage was associated with specific disadvantage. Girls married at or before 16 years were 4.42 times less likely to obtain a basic education defined as Year 10 school certificate (10.33% vs 43.65% of their cohort, Chi Squared 202.46, PValue < 0.0001). They are 5.12 times less likely to obtain a Year 12 Higher School Certificate (2.2% vs 11.2% of their cohort, Chi Squared 42.282, PValue < 0.0001), and 16.3 times less likely to obtain a bachelor’s degree (0.7% vs 10.9% of their cohort, (Chi Squared 60.279, PValue <0.0001). Expressed differently, when controlled for income, for every 8.15 brides in the poorest income Band who obtains at least a basic school certificate, only 1 will have been married at or before 16 years.

Girls married at or under 16 years experienced higher rates of reproductive adversity: CMR was 1.4 times (78.2 vs 54.8, PValue 0.0008), and NMR 1.7 times higher (23.7 vs 13.7, PValue 0.0002) than those with older mothers. Offspring of under-aged mothers in income Band 1 were more frequently stunted (44.8% PValue 0.0204) than children of older brides in the same Band (34.9%) (PValue 0.0204). This effect was not seen in higher Bands.

Betel nut

28.6% of mothers declared they chewed betel nut during pregnancy. Consumption was more common in the lowest income group (37.7%), falling progressively to 1% in the highest.

Discussion

Compared to national data published by BDHS many aspects of maternal health have stalled in rural northern Mymensingh District. Our survey did not examine rates of maternal mortality but maternal stunting, underweight, overweight, home births, reproductive adversity, and underage marriage rival the highest in the country. The burden of maternal adversity is thus a major challenge in the region. The rate of maternal stunting in northern Mymensingh (mean of 15.4%) rivals that reported from Sylhet (15.7%), the highest recorded in BDHS 2014. Maternal stunting is a recognised risk factor for foetal growth restriction and adverse perinatal outcome [6] and for increased morbidity, mortality, underweight and stunting in offspring [7]. Foetal growth restriction is also known to predispose to the metabolic syndrome in adulthood, particularly when food intake is enhanced. Childhood stunting increases mortality rates in children and reduces their human capital and, thus, their ultimate contribution to national development. Maternal undernutrition confirmed by BMI <18.5 has similar adverse effects as stunting6 and was common in surveyed areas, but not as common as reported from rural Sylhet (13 vs 29.8%), though stunting rates are similar [2].

Our contemporaneous rates of overweight are remarkably high: with 14.4% of mothers at risk, 26.1% overweight and 4.2% obese, nearly half the female population is affected. Though ‘at risk’ pertains to BMI as low as 23 kg/m2, Asian populations have been reported susceptible to the development of cardiovascular disease and diabetes from that level, perhaps because of a higher percentage of body fat [3]. This propensity to being overweight may explain the lower rates of underweight between Mymensingh and Sylhet, despite similar rates of stunting. Thus, the higher rates of BMI (dependent on weight vs height) in Mymensingh confirm the unreliability of BMI as an index of healthy nutrition, especially in Asian populations [3]. Being overweight is associated with obstetric adversity [8] but the dyad of stunting and obesity compounds problems. Described as ‘The new obstetrical dilemma’ [9], the risk of cephalo-pelvic disproportion is increased when a small pelvis is presented with a macrosomic baby in a stunted but obese mother. Also described as a ‘double burden’ of malnutrition, the dyad is being recognised with increasing frequency in many developing countries, but causes remain debated [10–12]. Perhaps it is related to increasing wealth and, therefore, family consumption of high-density caloric foods which fatten the stunted mother but do not promote linear growth in the offspring. ‘Food consumption’ by itself, however, was not found to account for higher obesity in a poor region of Brazil [13]: reduction in urbanised maternal activity was considered contributory. Given the overlap of the high prevalence of both stunting and obesity, its correlation has even been dismissed as a statistical artefact, not a distinct entity [14].

Whatever the association, given the predisposition of stunting with overweight to the metabolic syndrome according to the Barker Hypothesis, increasing problems of cardiovascular disease and diabetes may be expected in northern Mymensingh. At present, however, only 10 cases of gestational diabetes and 15 cases of hypertension were associated with the 2532 births in 2018 in Joyramkura Hospital [15]. Doubtless, in-utero growth restriction contributed to the high rate of stunting but birth weights were unknown to most mothers in our survey. The 9% rate of babies born <2,500 gm in the private Joyramkura Hospital is much less than the national rate of 20% [16], and may reflect difficulty in attendance by the poorest, undernourished and stunted mothers.

Perinatal death rates appear to result from the lethal combination of vulnerable mothers undergoing home births with untrained attendants. The high rate of children living with cerebral palsy (11.8 per 1000 live births) found in the 25 sites (and reported elsewhere) [17] would confirm problems in labour and neonatal care. The high CMR probably reflects their later deaths. Childhood stunting was associated with prolonged breast feeding, especially in low income households, and appears associated with failure of diversification of diet from six months of age (personal communication). Further research is being undertaken but breast milk and unpolished rice appear fundamental. That the prevalence of stunting increased from mother to older and then younger child is hard to explain. There have been no financial or natural disasters in the region that could account for such a dramatic increase in childhood under-nutrition. Perhaps the prevalence of maternal obesity is related to the phenomenon: mothers are now consuming new foods whose density of calories causes them to gain weight, but whose sparsity of protein prevents linear growth in offspring. Perhaps, this diet explains the increased CMR in children of stunted and overweight mothers, whose stillbirth rate is not significantly increased.

Open latrines predispose to recurrent intestinal infection and infestation, and malabsorptive enteropathy. Our survey revealed childhood stunting to be related to their use in the poorest income Band. That many mothers will have grown up in those sites suggests open latrines contribute to inter-generational stunting. Marriage before the age of 18 is often considered a breach of human rights [18]18 but is common in many developing countries [19] especially in Asia [20,21], Its risks are publicised: mental, sexual and reproductive problems, violence, reduced education and sustained poverty [22]; as well as a higher risk of stunting, developmental delay18 and mortality in offspring [23]. Socio-cultural and financial factors are reported causative [24]. Our study did not pursue such factors, but noted the frequency of under-age marriage in northern Mymensingh and its association with poverty, reduced education and reproductive adversity. We relied on maternal reporting for age of marriage and did not distinguish between betrothal and co-habitation.

The actual rate is likely to be much greater than suggested by our survey. The great outlier of professed marriage at 18 years may suggest an awareness of its illegality at a younger age. Alternatively, girls could be waiting to be married at 18, but if that were case, there would be fewer marriages at 16 and 17 years, contrary to the expected distribution as revealed in Figure 3. Education programmes fostering female empowerment are claimed effective in reducing child marriage [25]. Consumption of ‘betel nuts’ ranks fourth in the world’s consumption of addictive substances, after alcohol, tobacco and caffeine [26]. Our survey revealed 29% of mothers, particularly the poorest, consumed it in pregnancy. The seeds of the Areca palm (Arecha catechu) are consumed in a ‘quid’ with tobacco leaf, to which calcium hydroxide has been added to promote extraction of alkaloids. Effects on the autonomic system as well as endothelial cell growth in the placenta [27] may contribute to intra-uterine growth restriction [28–30].

Our study cross sectional study has limitations. The birth dates, weights and gestations were rarely recorded in home births. As warned in BDHS 2014, memory of ages and causes of death, even of stillbirths themselves, dims with passing years in retrospective, cross sectional studies. Lack of memory predisposes to the next problem in data collection: the ‘heaping up’ of estimates to intervals of significance eg to one year of age. Third, information was gathered by several translators without calibration of skill. Our study reveals the need for further investigation. ‘Verbal’ post-mortems should probe the high rates of death. Practical issues need to be examined: how can traditional birth attendants be educated to recognise complications in the mother and care for the baby. What transportation is possible for a mother in difficulty? What obstetric facilities are available? Why is a population of over half a million not seeking help in the regional centres of Dhobaura and Haluaghat? In 2018, together, those hospitals reported 809 deliveries, 788 live births, 21 stillbirths and 62 neonatal deaths, with no Caesarian sections [31].

Conclusion

Our broad brush, cross-sectional survey reveals, for the first time, major problems in mothers’ health in northern Mymensigh. It emphasises the need for education on nutrition, early recognition of obstetric complications, neonatal care, disposal of sewage, betel nut consumption, under-age marriage and empowerment of women. It emphasises the need for improved obstetric care: from more and better trained attendants, to adequate transportation, to the ability to intervene when things go wrong. The scarcity of Caesarian sections in the regional government hospitals substantiates the introductory lament of BMMS that ‘most facilities…are not fully ready to provide quality maternity care’.

References

- Ahsan KZ, Ahmed S, Angeles G, Benson A, Chakraborty N, et al. (2017) (National Institute of Population Research and Training, International Centre for Diarrhoeal Disease Research, Bangladesh, MEASURE Evaluation). Bangladesh maternal mortality and health care survey 2016. Preliminary report. Dhaka (BD): Government of the People’s Republic of Bangladesh; 106 p. Report No.: TR-17–218.

- Ministry of Health and Family Welfare (2016) National Institute of Population Research and Training; Mitra and Associates; ICF International, DHS Program. Bangladesh demographic and health survey 2014. Dhaka (BD): Ministry of Health and Family Welfare, National Institute of Population Research and Training, Pg No: 328.

- WHO Expert Consultation (2004) Appropriate body-mass index for Asian populations and its implications for policy and intervention strategies. Lancet 363: 157–163.

- Halim A, Aminu M, Dewez JE, Biswas A, et al. (2018) Stillbirth surveillance and review in rural districts in Bangladesh. BMC Pregnancy Childbirth 18: 224. [crossref]

- Baqui AH, Choi Y, Williams EK, Arifeen SE, Mannan I, et al. (2011) Levels, timing, and etiology of stillbirths in Sylhet district of Bangladesh. BMC Pregnancy Childbirth 11: 25. [crossref]

- Black RE, Victora CG, Walker SP, Bhutta ZA, Christian P, et al. (2013) Maternal and child undernutrition and overweight in low-income and middle-income countries. Lancet 382: 427–451.

- Ozaltin E, Hill K, Subramanian SV (2010) Association of maternal stature with offspring mortality, underweight, and stunting in low- to middle-income countries. JAMA 303: 1507–1516.

- Black M, Bhattacharya S (2013) Maternal Obesity and the Risk of Stillbirth. In: Mahmood T, Arulkumaran S, (eds). Obesity. Oxford: Elsevier; Pg No: 371–382.

- Wells JC (2017) The New “Obstetrical Dilemma”: Stunting, Obesity and the Risk of Obstructed Labour. Anat Rec (Hoboken) 300: 716–731.

- Jehn M, Brewis A (2009) Paradoxical malnutrition in mother-child pairs: untangling the phenomenon of over- and under-nutrition in underdeveloped economies. Econ Hum Biol 7: 28–35.

- Lee J, Houser RF, Must A, de Fulladolsa PP, Bermudez OI (2010) Disentangling nutritional factors and household characteristics related to child stunting and maternal overweight in Guatemala. Econ Hum Biol 8: 188–196. [crossref]

- Lee J, Houser RF, Must A, de Fulladolsa PP, Bermudez OI (2012) Socioeconomic disparities and the familial coexistence of child stunting and maternal overweight in Guatemala. Econ Hum Biol 10: 232–241. [crossref]

- Florêncio TT, Ferreira HS, Cavalcante JC, Luciano SM, Sawaya AL (2003) Food consumed does not account for the higher prevalence of obesity among stunted adults in a very-low-income population in the Northeast of Brazil (Maceió, Alagoas). Eur J Clin Nutr 57: 1437–1446. [crossref]

- Dieffenbach S, Stein AD (2012) Stunted child/overweight mother pairs represent a statistical artifact, not a distinct entity. J Nutr 142: 771–773.

- Samper-González J, Burgos N, Bottani S, Fontanella S, Lu P, et al. (2018) Reproducible evaluation of classification methods in Alzheimer’s disease: Framework and application to MRI and PET data. Neuroimage 183: 504–521. [crossref]

- Khan JR, Islam MM, Awan N, Muurlink O (2018) Analysis of low birth weight and its co-variants in Bangladesh based on a sub-sample from nationally representative survey. BMC Pediatr 18: 100.

- Authors (2019) Child mortality, nutrition and cerebral palsy: a cross sectional survey in northern Bangladesh. Nutrients 2019.

- Efevbera Y, Bhabha J, Farmer PE, Fink G (2017) Girl child marriage as a risk factor for early childhood development and stunting. Soc Sci Med 185: 91–101. [crossref]

- Nour NM (2009) Child marriage: a silent health and human rights issue. Rev Obstet Gynecol 2: 51–56. [crossref]

- Raj A (2010) When the mother is a child: the impact of child marriage on the health and human rights of girls. Arch Dis Child 95: 931–935. [crossref]

- UNICEF (2011) Working towards a common goal: ending child marriage [Internet]. [2019 Jun 6]. Available from: https://www.unicefusa.org/stories/working-towards-common-goal-ending-child-marriage/7086.

- Parsons J, Edmeades J, Kes A, Petroni S, Sexton M, et al. (2015) Economic impacts of child marriage: A review of the literature. The Review of Faith & International Affairs 13: 12–22.

- Adhikari R (2003) Early marriage and childbearing: risks and consequences. In: Bott S, Jejeebhoy S, Shah I, Puriet C, editors. Towards adulthood: Exploring the sexual and reproductive health of adolescents in South Asia; 2000; Mumbai, India. Geneva: World Health Organization Pg No: 62–66.

- Chowdhury FD (2014) The socio-cultural context of child marriage in a Bangladeshi village. Int J Soc Welf 13: 244–253.

- Lee-Rife S, Malhotra A, Warner A, Glinski AM (2012) What works to prevent child marriage: a review of the evidence. Stud Fam Plann 43: 287–303. [crossref]

- Gupta PC, Ray CS (2004) Epidemiology of betel quid usage. Ann Acad Med Singapore 33: 31–36. [crossref]

- Kuo FC, Wu DC, Yuan SS, Hsiao KM, Wang YY, et al. (2005) Effects of arecoline in relaxing human umbilical vessels and inhibiting endothelial cell growth. J Perinat Med 33: 399–405. [crossref]

- Garcia-Algar O, Vall O, Alameda F, Puig C, Pellegrini M, et al. (2005) Prenatal exposure to arecoline (areca nut alkaloid) and birth outcomes. Arch Dis Child Fetal Neonatal Ed 90: 276–277.

- Senn M, Baiwog F, Winmai J, Mueller I, Rogerson S, et al. (2009) Betel nut chewing during pregnancy, Madang province, Papua New Guinea. Drug Alcohol Depend 105: 126–131.

- Yang MS, Lee CH, Chang SJ, Chung TC, Tsai EM, et al. (2008) The effect of maternal betel quid exposure during pregnancy on adverse birth outcomes among aborigines in Taiwan. Drug Alcohol Depend 95:134–139.

- Government of the People’s Republic of Bangladesh, Ministry of Health and Family Welfare. Dhubaura Upazila Health Complex Health Bulletin 2015 [Internet]. [Mohakhali, Dhaka]: Government of the People’s Republic of Bangladesh, Ministry of Health and Family Welfare; 2015 [cited 2019 Jun 6].

[1] de Onis M, et al. (2012) Worldwide implementation of the WHO Child Growth Standards. Public Health Nutrition 15: 1603–1610.

[2] de Onis M (2006) Reliability of anthropometric measurements in the WHO Multicentre Growth Reference Study. Acta Pædiatrica 95: 8–46.