Abstract

Recently, ultrasonic imaging modalities have been increasingly used to observe the locomotor apparatus. Furthermore, a high reliability has been reported for the measurements of fascial displacement using ultrasonic imaging and of muscle stiffness using ultrasonic elastography. This study aimed to clarify the ultrasonographic changes in fascial displacement and muscle stiffness induced by Myofascial Release (MFR). We divided 51 healthy adults (24 males and 27 females) into three groups: MFR, Static Stretching (SS), and control groups. The passive ankle joint dorsiflexion angle, isometric ankle joint flexor muscle strength, superficial- and deep-layer fascial displacement, and muscle stiffness were each measured before, immediately after, and at 4 days after an intervention. All parameters in the MFR group showed significant changes immediately after and 4 days after the intervention compared with those at baseline. The MFR group also showed more significant changes in the dorsiflexion angle, fascial displacement, and muscle stiffness after 4 days compared with the SS group. Thus, MFR improves the viscoelasticity of the gelled matrix and eliminates the densification of collagen and elastin fibers, thereby smoothing fascial gliding. Consequently, this technique may help to regain the gliding ability of the fascia during joint movement and muscle contraction. In addition, it was also suggested that changes in physical function and fascial property due to MFR were significantly different after 4 days.

Keywords

Myofascial Release, Static Stretching, Fascial Displacement, Muscle Stiffness, Changes Over Time

Introduction

The fascia is a tissue which envelops the whole body on the sheath from head to toe and is continuous from the surface of the soft tissue to the visceral organ. One of the main functions of the fascia is to support the organs, and in addition to supporting blood vessels, nerves, and lymphatics, it passes through them. Therefore, when a functional abnormality (such as densification of collagen and elastin fiber, gelation of matrix, aggregation of hyaluronic acid) occurs in the fascia, symptoms such as pain, malalignment, limited range of motion, or muscle output weakness are manifested [1]. Myofascial release (MFR) is a manual therapy used to treat fascial dysfunctions, such as dysfunctions, including collagen and elastin fiber densification, matrix gelation, and hyaluronic acid agglomeration, by continuously applying gentle pressure and extension to the deep fascia [1]. We previously investigated the immediate and long-term effects (6 days) of MFR for the hamstrings based on the straight-leg-raising angle and the knee flexion muscle strength. Significant increases were noted in both the angle and the strength until 4 days after MFR, [2] but the outcome was only verified by a change in physical function, it was unknown what changes occurred in the fascia, and it was not possible to explain what benefit fascia was actually giving.

Ultrasound is a noninvasive imaging method with easy utility that can be used to observe the locomotor apparatus. For example, Chi-Fishman et al. [3] and Maganaris et al. [4] reported high reliability with a positive correlation between ultrasound and the change in physical function. Fukunaga et al. [5] also observed changes in the pennation angle of the fascia and muscle bundle under voluntary contraction and reported that changes in muscle bundle length and pennation angle on ultrasound could be quantified for use in physiological and biomechanical research. These findings indicate that it is reasonable to use ultrasonography to observe fascial displacement (gliding). Indeed, Otsudo et al. [6] used ultrasound to visualize the fascia of the gastrocnemius during voluntary contraction, and Ichikawa et al. [7] reported that there was significant movement of the fascia of the vastus lateralis during knee flexion under voluntary contraction or passive exercise conditions. The reliability of ultrasonic imaging of the fascia was confirmed by Ichikawa et al. [8] for the vastus lateralis and by Murano et al. [9] for the tibialis anterior, with both showing high reliability without addition or proportional errors.

Elastography is another ultrasound method and can be used to measure muscle stiffness, with strain elastography most widely used because it can be applied simply and in real-time [10]. The intra-rater reliability of muscle stiffness measurement by strain elastography is reportedly very high [11–12]. Therefore, we used strain elastography to examine the intra- and inter-rater reliabilities at baseline and day 4 for measurements of muscle stiffness (0° ankle joint) and displacement of the superficial and deep fascia of the lateral head of the gastrocnemius during passive ankle dorsiflexion. The intraclass correlation coefficients indicated that reliability was almost perfect (0.89–1.00) [13,14]. Therefore, this method has high validity and high reproducibility for measuring fascial displacement and muscle stiffness of the lateral head of the gastrocnemius up to 4 days after MFR.

We wanted to use ultrasound equipment to visualize fascial gliding with high reliability to investigate the changes in fascial properties over 4 days. To clarify whether changes develop in the fascia after MFR, we assessed the effect of MFR on the fascia by observing not only changes in physical function but also the ultrasonographic changes in fascial displacement and muscle stiffness at baseline, immediately after, and at 4 days after MFR.

Methods and Materials

Study Design and Participants

This study included 51 healthy adults (24 males and 27 females) in their 20s and 30s who had no history of orthopedic diseases of legs, cardiovascular diseases, or central nervous system diseases. The average age (range) was 27.6 (22–37) years, the average height (standard deviation) was 162.9 (7.08) cm, and the average body weight (standard deviation) was 56.6 (9.34) kg. The participants were quasi-randomly distributed into an MFR group, a Static Stretching (SS) group, and a control group.

The study was approved by the Research Safety Committee of Tokyo Metropolitan University (approval number 17110), the Research Ethics Committee of Saku University (approval number 217004), and the Clinical Research Ethics Review committee of Asama General Hospital (approval number 17–18). All participants received an explanation of the purpose and content of the study and we obtained written informed consent.

Protocol

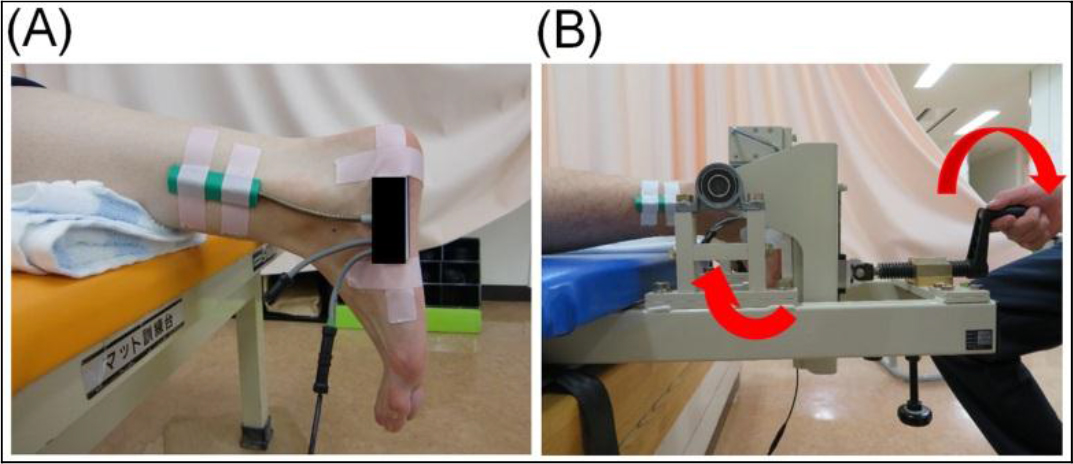

For the MFR group, a practitioner placed his or her hands on the proximal and distal portions of the lateral head of the gastrocnemius of the pivoting foot in the prone position and MFR was performed in the longitudinal direction for 180 s (Figure 1). For the SS group, the foot was taken out of the bed in the prone position and placed on a plantarflexion strength measuring aid (Takei Instrumentation Co., Ltd.). The trunk and foot are fixed by using the shoulder pad, pedal, and pelvic belt of this aid with the knee and the ankle joint at 0°. Then, passive dorsiflexion of the ankle joint was performed three times of resting for 60 s by turning the lever at the angle not causing compensation or pain (Figure 2). For the control group, participants were laid prone on the bed for 180 s and subject to no intervention. The participants were asked not to engage in any special exercise during the 4 days of the study, but they were encouraged to continue with daily life as usual.

Measurements

The following items were measured: (1) passive ankle joint dorsiflexion angle (“angle”), (2) isometric ankle joint flexion strength (“strength”), (3) superficial and deep fascial displacement, and (4) muscle stiffness. All items were measured in the prone position with feet taken out of the bed, the knee and the ankle joint at 0°, and the trunk and foot fixed with the shoulder pad, pedal, and pelvic belt of the plantarflexion strength measurement aid. Two or three people performed each measurement so that the participants were not informed of the group to which they were assigned. Each measurement was performed in triplicate before, immediately after, and 4 days after an intervention, and the average at each assessment was used. The measurement procedures are now presented in more detail.

Figure 1. Myofascial release of the lateral head of the gastrocnemius.

Figure 2. Method of passive dorsiflexion of the ankle joint.

(By turning the lever, the pedal is dorsiflexed and the triceps surae is stretched)

(1) Angle measurement

We used the sensors of a biaxial goniometer for the ankle joint (SG110 / type A manufactured by DKH Co., Ltd.) attached to a feedback recording device (PH-7010 Feedback Logger manufactured by DKH Co., Ltd.) placed on the fifth metatarsal bone and fibula (Figure 3). Passive ankle joint dorsiflexion was performed mechanically from a joint position of 0° using the plantarflexion strength measurement aid, and the maximum dorsiflexion angle within tolerable pain limits was measured.

Figure 3. The procedure for measuring the range of motion.

A: The position of the electronic goniometer B: The mechanical passive ankle dorsiflexion

(2) Strength Measurement

This was measured at maximum isometric ankle joint plantarflexion by applying a sensor of a manual muscle strength measuring device (μTas F-1 manufactured by Anima Co., Ltd.) between the first metatarsal head and the pedal of the plantarflexion strength measurement aid (Figure 4). The value obtained was multiplied by the lever arm to obtain the joint torque value, before being divided by body weight.

Figure 4. Positioning of the foot and sensor for strength measurement.

(The sensor position (arrow) of the measuring device for manual muscle force during isometric plantarflexion)

(3) Superficial and Deep Fascial Displacement

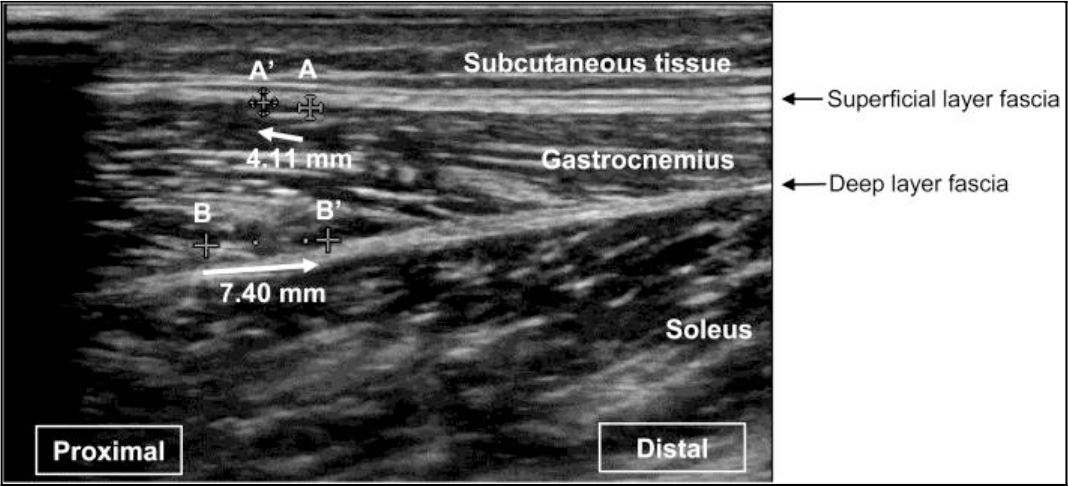

A linear probe with a coupler attached at the tip (EZU-TEATC 1 manufactured by Hitachi Aloka Medical, Co., Ltd.) was placed on the lateral head of the gastrocnemius of the pivoting foot, parallel to the long axis of the lower thigh. We marked the edge of the coupler attachment with a permanent marker so that the probe could be repeatedly applied to the same site. Passive ankle dorsiflexion was performed from 0° to 15° using the plantarflexion strength measuring aid, and we visually tracked the displacement of the intersection of the gastrocnemius muscle fiber and the superficial and deep fascia on the screen of an ultrasound (Noblus, manufactured by Hitachi Aloka Medical, Ltd.) (Figure 5) and measured it. We took great care to use minimum contact strength to ensure clear ultrasonic images without changes in muscle shape.

Figure 5. Representative ultrasound images.

A: Intersection of the gastrocnemius muscle fiber and the superficial fascia. A’: Point A after passive dorsiflexion. B: Intersection of the gastrocnemius muscle fiber and the deep fascia. B’: Point B after passive dorsiflexion.

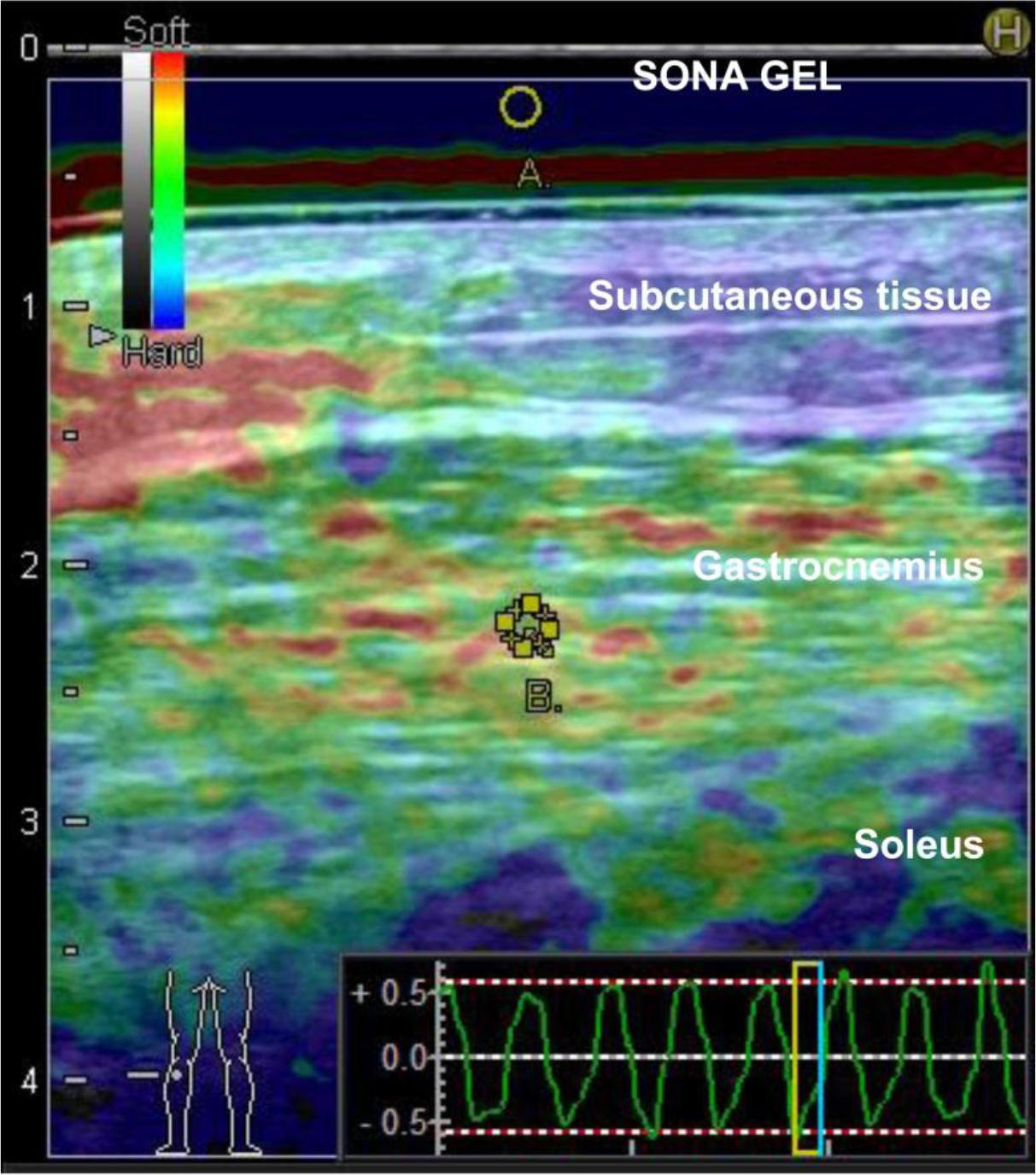

(4) Muscle Stiffness Measurement

SONA GEL (N0511 manufactured by Takiron Co., Ltd.) at a thickness of 5 mm was sandwiched between the probe and the skin when comparing muscle stiffness. We used the real-time tissue elastography setting and applied pressure several times on the part assessed in the measurement of fascial displacement at a prespecified level to identify the appropriate pressure. The strain ratios for the regions of interest were calculated for the SONA GEL (Figure 6A) and the gastrocnemius (upper, lower, left, and right central parts depicted on the screen) (Figure 6B).

Measurements and recordings were performed by 2–3 persons so that the subjects were not informed about the group to which they were assigned (PROBE method). Each measurement was performed 3 times: before, immediately after, and 4 days after the intervention, and an average value (three significant figures) was adopted.

Statistical Analysis

We used IBM SPSS Version 22 (IBM Corp., Armonk, NY, USA) for the statistical analyses. To compare physical features between the three groups, one-way analysis of variance was performed for the basic attributes (i.e., age, height, and weight of each group) and baseline measurements (i.e., before intervention) after confirming the normality of that data. The differences between groups at each measurement point and the differences between each measurement point in each group were analyzed using the Dunnett and Bonferroni methods after repeated measures analysis of variance with the basic attributes set as covariates. The significance level was set at 5%. Descriptive data are presented as mean (range) or as mean (standard deviation).

Figure 6. Representative image of real-time tissue elastography.

A: Region of interest for SONA GEL (reference) B: Region of interest of for the gastrocnemius

Results

Basic Findings

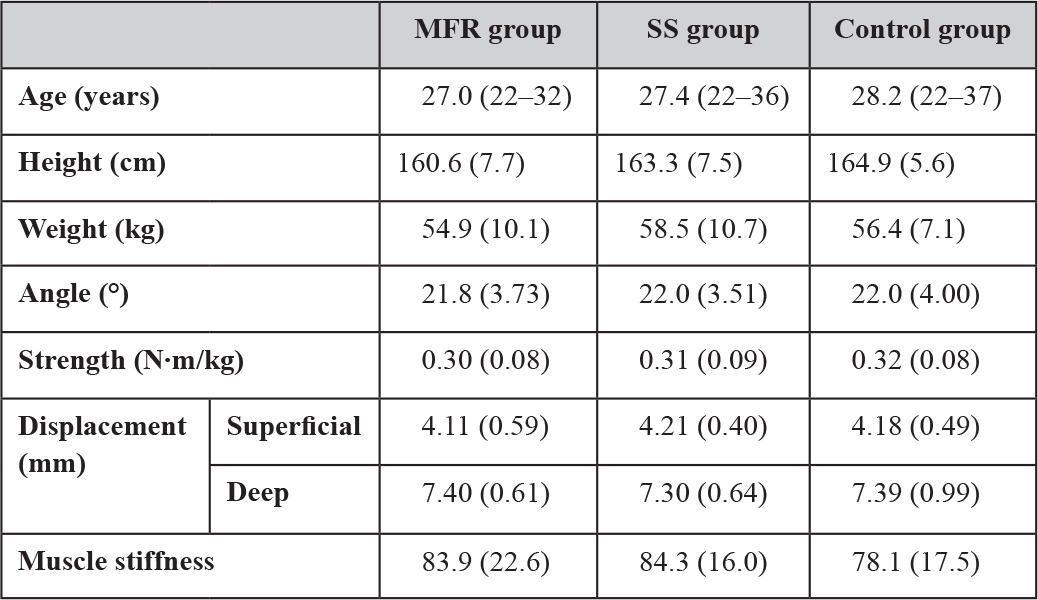

The MFR, SS, and the control groups each included eight men and nine females. There were no differences in physical characteristics among the three groups before the intervention (Table 1). However, we did observe interactions between groups for each measurement item and at each measurement period immediately and 4 days after MFR. Tables 2–5 show the changes in each measurement item over time by study group.

Table 1. Baseline physical characteristics of each group.

Data are shown as the mean (standard deviation) before intervention. Range is only reported for the age. Abbreviations: MFR, myofascial release; SS, static stretching. The control group received no intervention and simply lay on a bed for the same duration as used for SS and MFR.

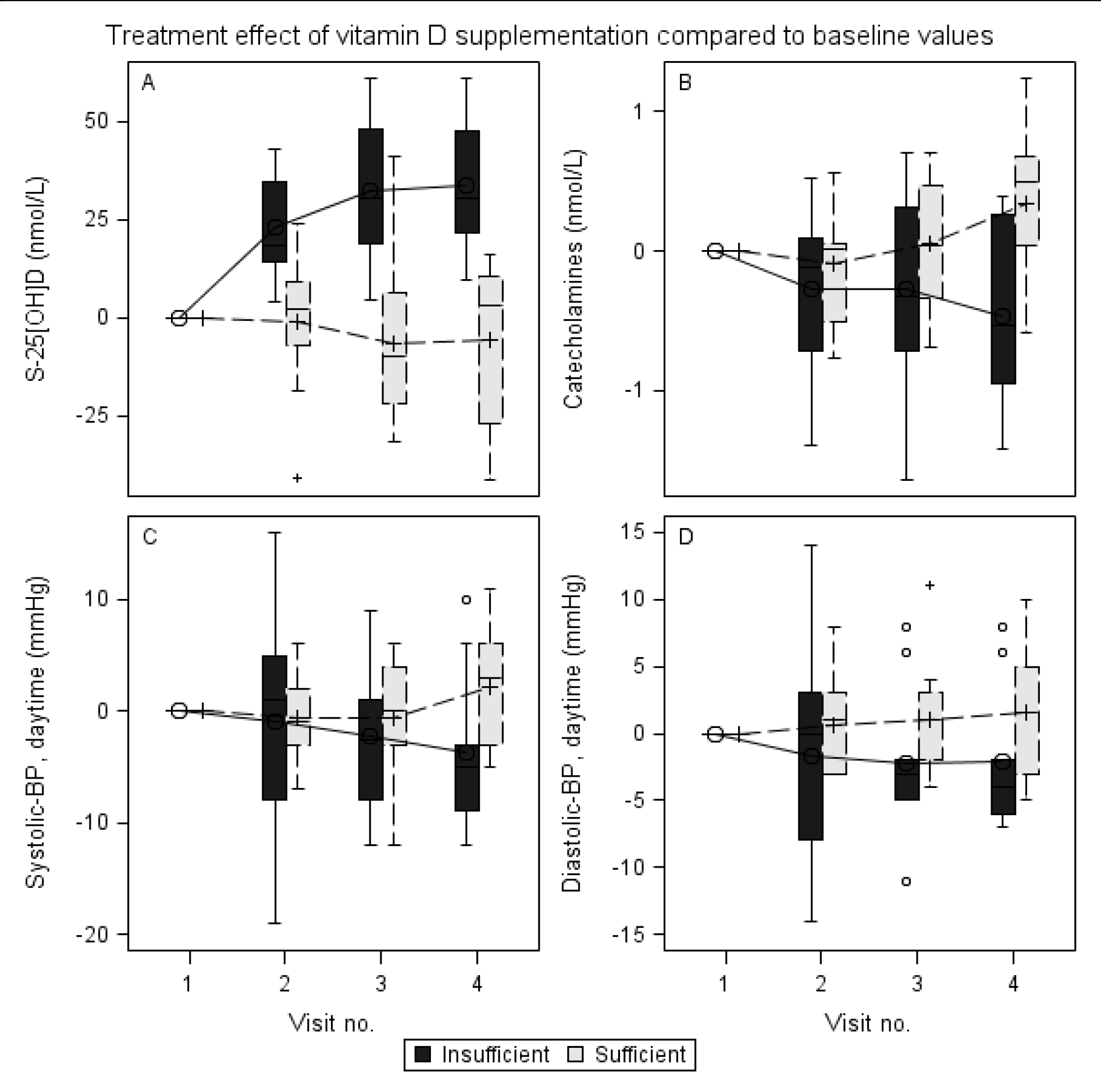

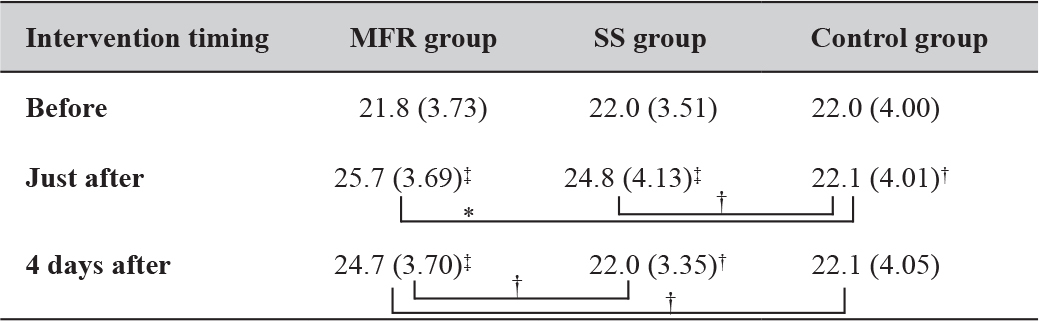

Changes in the angle

There was a significant increase in the angle in the MFR group immediately and 4 days after the intervention compared with before the intervention; by contrast, the SS group showed a significant increase only immediately after the intervention. There were no significant differences in values between the MFR and SS groups immediately after the intervention, but the differences tended to be larger in the MFR group after 4 days (Table 2).

Table 2. Time course of the changes in angle (°) measurements.

Mean (Standard deviation). *: P < 0.05; **: P < 0.01; †: 0.05 ≤ P < 0.1;

‡: represents the result of the Dunnett method. Abbreviations: MFR, myofascial release; SS, static stretching. The control group received no intervention and simply lay on a bed for the same duration as used for SS and MFR.

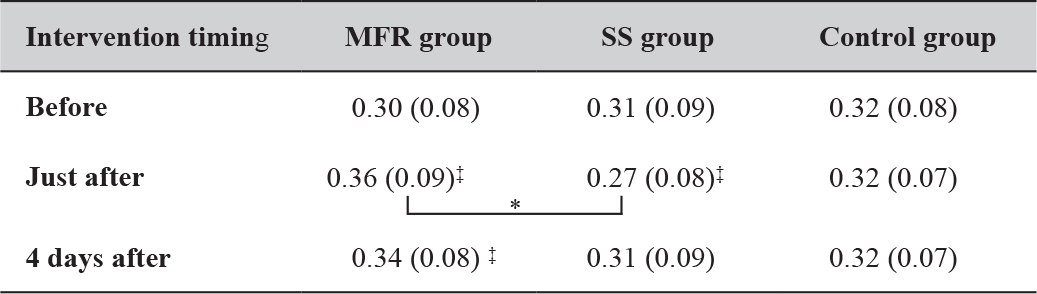

Changes in Strength

Strength increased significantly in the MFR group immediately and 4 days after the intervention compared with before, but decreased significantly in the SS group immediately after the intervention. The MFR group only showed significantly higher strength than the SS group immediately after intervention (Table 3).

Table 3. Time course of the changes in strength measurements (N∙m/kg).

Mean (Standard deviation). *: P < 0.05; **: P < 0.01;

‡: represents the result of the Dunnett method. Abbreviations: MFR, myofascial release; SS, static stretching. The control group received no intervention and simply lay on a bed for the same duration as used for SS and MFR.

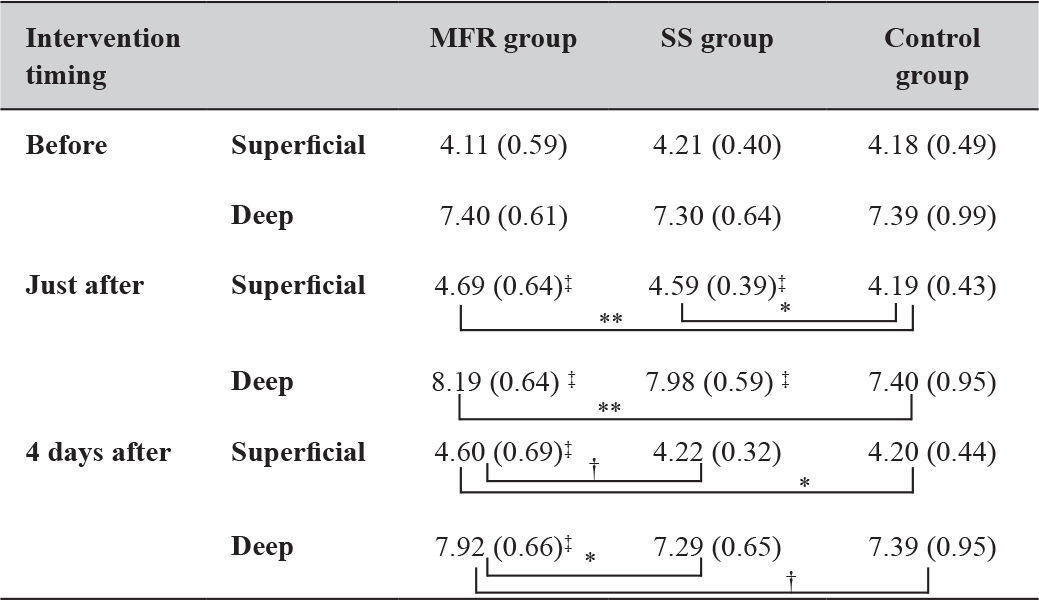

Changes in Fascial Displacement

In both the superficial and the deep layers, fascial displacement in the MFR group increased significantly immediately and 4 days after the intervention compared with before. However, the SS group only showed a significant increase immediately after the intervention. The results were comparable between the MFR and SS groups immediately after the intervention, but after 4 days, the MFR group tended to show greater displacement in the superficial layer and showed significantly greater displacement in the deep layer (Table 4).

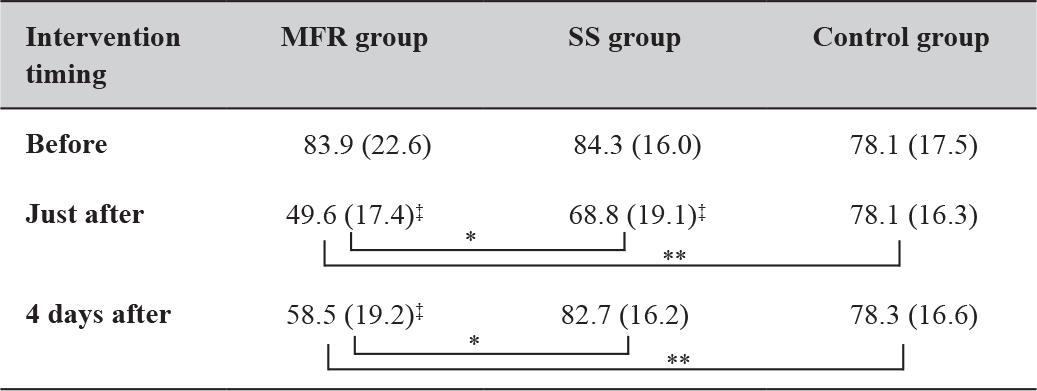

Changes in Stiffness

Regarding the stiffness, the MFR group showed a significant decrease immediately and 4 days after the intervention compared with before, whereas the SS group showed a significant decrease only immediately after. The MFR group had significantly less stiffness than the SS group both immediately and 4 days after the intervention (Table 5).

Table 4. Time course of the changes in displacement (mm) measurements.

Mean (Standard deviation). *: P < 0.05; **: P < 0.01; †:0.05 ≤ P < 0.1;

‡: represents the result of the Dunnett method. Abbreviations: MFR, myofascial release; SS, static stretching. The control group received no intervention and simply lay on a bed for the same duration as used for SS and MFR.

Table 5. Time course of the changes in muscle stiffness measurements.

Mean (Standard deviation). *: P < 0.05; **: P < 0.01;

‡: represents the result of the Dunnett method. Abbreviations: MFR, myofascial release; SS, static stretching. The control group received no intervention and simply lay on a bed for the same duration as used for SS and MFR.

Discussion

We predicted that MFR would produce significant differences in physical function (angle and strength) and fascial properties (displacement and muscle stiffness) immediately and 4 days after the intervention compared with that at baseline and that those changes would be larger than those observed when performing SS. Consistent with our previous research, [2] we noted significant improvements in physical function in the MFR group compared with those in physical function in the SS and control groups at both post-intervention assessments. However, the angle tended to be higher after 4 days, with no significant difference in strength, whereas our previous data indicated that both the angle and strength continued to significantly improve until 4 days [2]. The gastrocnemius muscle has medial and lateral heads, which are semi-pennate muscles, and this muscle may account for the different results observed between our studies.

In the previous study, we performed MFR on the posterior aspect of the thigh to catch both the medial and lateral hamstrings. In this study, the gastrocnemius was used as a test muscle due to the ease of visualization of this muscle on ultrasonic imaging during passive exercise. However, the myofascial sequence of the lateral and medial heads of the gastrocnemius was different; [15] therefore, in this study, we performed MFR only on the lateral head of the gastrocnemius. Conversely, both the lateral and medial heads of the gastrocnemius were stretched by passive dorsiflexion of the ankle joint in the SS group. According to Kubo et al., the component of the longitudinal direction of the force exerted by the muscle fascicle determines the magnitude of the rotational moment of the joint in the pennate muscle [16]. The deep fascia of the lateral and medial heads were continuous, but MFR was only performed on the lateral head, which resulted in differences in the sliding of the deep fascia and muscle fibers. Consequently, components in the longitudinal direction may have become disproportionate and the study duration may have been insufficient to show changes in angle or strength after MFR. Temporary muscle weakness immediately after SS has already been explained through tendon spindle excitation, which is characterized by sustained elongation of the triceps surae and the suppression of muscle contraction (Ib inhibition) [17]. This is consistent with our result.

There were clear differences in fascial properties and physical function. The MFR group showed significant changes both immediately and at 4 days after the intervention compared with the SS and control groups. Nakamura et al. suggested that improving muscle flexibility by SS might improve the flexibility of connective tissue around muscle fibers instead of prolonging the length of muscle fibers [18]. Purslow also reported that connective tissue (e.g., the perimysium), was a major factor related to passive stiffness [19]. Thus, MFR might be more effective for improving fascial displacement and muscle stiffness than SS. In addition, Ichikawa et al. reported a significant increase in fascial displacement and a significant decrease in muscle stiffness immediately after MFR, [7] whereas Wong et al. reported a significant decrease in muscle stiffness [20]. Our findings support these and indicate that changes remain significant even at 4 days.

Although there were significant differences in muscle stiffness between the SS and MFR groups immediately after the intervention, there were no differences in either the angle or in fascial displacement. However, by 4 days, the MFR group tended to have a larger angle, significantly greater fascial displacement, and significantly lower muscle stiffness compared with the SS group. The mechanical properties of skeletal muscle can largely be divided into shrinkage, elasticity, viscosity, and plasticity, with muscle viscoelasticity being involved in muscle stiffness when measuring the magnitude of displacement against an external force [7]. Indeed, fascial viscosity is thought to be involved in the matrix [21]. Because the MFR group showed a significantly lower muscle stiffness, even after 4 days, we considered that MFR resolved not only the collagen and elastin fiber densification but also the matrix gelation (i.e., fascial dysfunctions) to improve viscosity. We suggest that those changes improved fascial gliding, increased fascial displacement, and increased the angle.

Concerning SS, Nakamura et al. reported a significant increase in displacement by the muscle tendon junction immediately after SS [18] and a significant decrease in muscle stiffness [22]. Akagi et al. also showed a significant acute decrease in muscle stiffness after three sets of SS for 2 minutes, with long-term effects after 5 weeks of an SS program [23,24]. However, Nordez et al. judged that there was no significant change on muscle stiffness after two sets of 2.5 minutes of SS [25]. It is possible that the SS implementation time may affect the muscle stiffness outcomes.

There are two main limitations of this study. The first relates to “stretch tolerance.” When measuring range of motion in the present study, limitation was determined subjectively based on this stretch tolerance of participants that is, to the point of pain and tolerability of the “stretchy feeling.” This has been cited as a major cause of acute changes in the range of motion assessed by SS [26,27]. However, acute changes in the range of motion and a temporary decrease in muscle strength occurred; thus, we cannot deny the possibility that changes after SS were due to a temporary change in the sense. The second limitation is that ankle joint measurements were taken in the neutral position (0°) to assess strength, fascial displacement, and muscle stiffness. According to Kawakami et al., the passive torque value of the ankle joint at 30° of plantarflexion becomes almost zero [28]. Thus, if 30° of plantarflexion indicates rest, 0° can be said to indicate that the triceps surae is extended. We do not believe that failing to measure at the original rest position of the triceps surae will have affected our results. However, it is possible that the values for strength, fascial displacement, and muscle stiffness are different in the two positions of the triceps surae.

In conclusion, we observed significant changes in fascial properties following manual MFR. These changes were consistent with improved viscoelasticity of the gelled matrix through gentle pressure and elongation, thereby eliminating collagen and elastin fiber densification. In this way, MFR restores fascial gliding during joint movement and muscle contraction. Significant changes in fascial properties remained even at 4 days after MFR, and all fascial changes were larger in the MFR group than in the SS group.

Acknowledgment

We would like to thank Enago (www.enago.jp) for the English language review.

References

- Takei H (2014) Myofascial release. In: Nara I, Kurosawa K, Takei H (eds.). Development of systematic treatment technique (3rdedn), Kyodo Isho publisher, Tokyo, Japan, Pg No: 13–58.

- Katsumata Y, Takei H, Hori T, Hayashi H (2016) Influences of muscle re-education exercises for myofascial extensibility and muscle strength after myofascial release. Rigakuryoho Kagaku 31: 99–106.

- Chi-Fishman G, Hicks JE, Cintas HM, Sonies BC, et al. (2004) Ultrasound imaging distinguishes between normal and weak muscle. Arch Phys Med Rehabil 85: 980–6.

- Maganaris CN, Baltzopoulos V, Sargeant AJ (1998) In vivo measurements of the triceps surae complex architecture in man: implications for muscle function. J Physiol 512: 603–614. [crossref]

- Fukunaga T, Ito M, Ichinose Y, Kuno S, et al. (1985) Tendinous movement of a human muscle during voluntary contractions determined by real-time ultrasonography. J Appl Physiol 81:1430–1433.

- Otsudo T, Takei H, Senoo A (2007) The influence of regulated compression for the gastrocnemius medialis muscle architectural change at rest and during isometric contraction in vivo. J Jpn Acad Health Sci (Japanese).

- Ichikawa K, Takei H, Usa H, Mitomo S, Ogawa D (2015) Comparative analysis of ultrasound changes in the vastus lateralis muscle following myofascial release and thermotherapy: a pilot study. J Bodyw Mov Ther 19: 327–336. [crossref]

- Ichikawa K, Usa H, Ogawa D, Mitomo S, et al (2013) The reliability of displacement measurement of the deep fascia using ultrasonographic imaging. J Jpn Acad Health Sci (Japanese).

- Murano I, Ebihara B, takihara J, Kawakami Y et al. (2016) Dynamics of the extensor retinaculum area of the Ankle measured by ultrasonography: reliability of a method for measuring the distance between the tibia and deep fascia. Rigakuryoho Kagaku.

- Shiina T (2014) Recent trends in research and development of ultrasound elastography. Med Imaging Technology. (Japanese).

- Junichi H, Mukai N, Takayanagi S, Miyakawa S (2013) The effect of muscle and tendon hardness after acute exercise: analysis on ultrasound Real-time Tissue elastography. J Phys Fit Sports Med. (Japanese)

- Muraki T, Ishikawa H, Morise S, Yamamoto N, Sano H, et al. (2015) Ultrasound elastography-based assessment of the elasticity of the supraspinatus muscle and tendon during muscle contraction. J Shoulder Elbow Surg 24: 120–126. [crossref]

- Katsumata Y, Takei H, Hayashi H, Ichikawa K (2017) Intra- and inter-rater reliabilities of measurements of fascial displacement and muscle stiffness by using ultrasound images. Rigakuryoho Kagaku. 2017 Apr 20. (Japanese).

- Landis JR, Koch GG (1977) The measurement of observer agreement for categorical data. Biometrics. 1977 March.

- Stecco L (2011) Myofascial Sequence Fascial Manipulation Theory Ed. Tokyo, Japan: Ishiyaku publisher 2011: 81–140.

- Kubo K, Azuma K, Kanehisa H, Kuno S, et al. (2003) Changes in muscle thickness, pennation angle and fascicle length with aging. Jap J Phys Fit Sport. (Japanese).

- Ninomiya I, Ando K, Kanosue K, et al. (2004) Physiology. 1st ed. Tokyo, Japan: Bunkodo 2004. (Japanese): 310–316.

- Nakamura M, Ikezoe T, Takeno Y, Ichihashi N. (2013) Time course of changes in passive properties of the gastrocnemius muscle-tendon unit during 5 min of static stretching. Man Ther. (Japanese).

- Purslow PP (1989) Strain-induced reorientation of an intramuscular connective tissue network: implications for passive muscle elasticity. J Biomech 22: 21–31. [crossref]

- Wong KK, Chai HM, Chen YJ, Wang CL, Shau YW, et al. (2017) Mechanical deformation of posterior thoracolumbar fascia after myofascial release in healthy men: A study of dynamic ultrasound imaging. Musculoskelet Sci Pract 27: 124–130.[crossref]

- Naka T (2003) A study of hyaluronic acid in skeletal muscle and its relevancy to physical therapy. Rigakuryoho. (Japanese).

- Nakamura M, Ikezoe T, Nishishita S, Umehara J, et al. (2017) Acute effects of static stretching on the shear elastic moduli of the medial and lateral gastrocnemius muscles in young and elderly women. Musculoskelet Sci Pract. 32:98–103.

- Akagi R, Takahashi H (2013) Acute effect of static stretching on hardness of the gastrocnemius muscle. Med Sci Sports Exerc 45:1348–1354.

- Akagi R, Takahashi H (2014) Effect of a 5-week static stretching program on hardness of the gastrocnemius muscle. Scand J Med Sci Sports 24: 950–957. [crossref]

- Nordez A, Gennisson JL, Casari P, Catheline S, et al. (2008) Characterization of muscle belly elastic properties during passive stretching using transient elastography. J Biomech 41: 2305–2311.

- Weppler CH, Magnusson SP (2010) Increasing muscle extensibility: a matter of increasing length or modifying sensation? Phys Ther 90: 438–449. [crossref]

- Magnusson SP, Simonsen EB, Aagaard P, Sørensen H, Kjaer M (1996) A mechanism for altered flexibility in human skeletal muscle. J Physiol 497: 291–298. [crossref]

- Kawakami Y, Ichinose Y, Fukunaga T (1985) Architectural and functional features of human triceps surae muscles during contraction. J Appl Physiol 85: 398–404.